Marcus Tullius Cicero

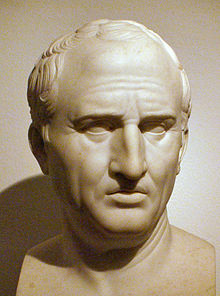

Marcus Tullius Cicero (pronunciation in classical Latin [ˈkɪkɛroː] ; * January 3, 106 BC in Arpinum ; † December 7, 43 BC in Formiae ) was a Roman politician, lawyer, writer and philosopher , the most famous speaker Rome and consul in 63 BC Chr.

Cicero was one of the most versatile minds in Roman antiquity. As a writer he was a stylistic model for antiquity, his works were imitated as models of a perfect, “golden” Latinity ( Ciceronianism ). Its importance in the philosophical field lies primarily not in its independent knowledge, but in the communication of Greek philosophical ideas to the Latin-speaking world; his Greek sources are often only tangible in their adaptation, as they have not come down anywhere else. The Senate honored him with the title pater patriae (father of the fatherland) for the suppression of the conspiracy of Catiline and the resulting temporary rescue of the republic .

His extensive correspondence, especially the letters to Atticus , had a decisive and lasting influence on the European letter culture. These letters and the rest of his work give us a detailed picture of the state of Rome at the end of the republic. During the civil wars and the dictatorship of Gaius Iulius Caesar , Cicero repeatedly advocated a return to the traditional republican constitution and the exercise of power. In his political practice he showed a flexibility that has earned him the charge of opportunism and lack of principles and the evaluation of which is still controversial in research. After Caesar's assassination in 44 BC BC Cicero was put on the proscription list by the triumvirs Antonius , Octavianus and Lepidus and on December 7, 43 BC. Killed on the run.

Life

Origin and education

Marcus Tullius Cicero was the eldest son of a Roman knight (eques) of the same name and his wife Helvia. He had a younger brother, Quintus Tullius Cicero , with whom he remained closely connected throughout his life.

His family belonged to the local upper class in Arpinum , a town in the Volsk region in southern Lazio , whose inhabitants had been living since 188 BC. . The AD Roman citizenship had. Cicero had both strong emotional and economic ties to and frequently returned to his birthplace. The general and statesman Gaius Marius , whose nephew Marcus Marius Gratidianus was the cousin of Cicero's father, also came from the area of Arpinum . Gratidia, a sister of Marius Gratidianus, was married to the politician Lucius Sergius Catilina .

The cognomen (nickname) Cicero was probably derived from the Latin cicer (" chickpea "). Early in his career, Cicero turned down his friends' suggestion to change this ridiculous looking cognomen. Rather, he wants to make it more famous than the names Scaurus (literally translated: "with protruding knuckles") and Catulus ("the doggy").

Cicero's family settled in 102 BC. To Rome. She belonged to the knighthood and thus to the second highest social class. In the year 90 BC BC Cicero received the toga virilis . Although the distant relationship to Gaius Marius was rather a hindrance to his ambitions under Sulla's dictatorship , there were other relationships to members of the Senate aristocracy who helped Cicero, his brother, and his cousin Lucius Tullius Cicero to get a good education in Rome. His mother's sister was married to Marcus Aculeo, a friend of Lucius Licinius Crassus . In his house Cicero received his first training. It was there that he met the great speaker Marcus Antonius Orator , to whom he later set a monument together with Crassus in his work De oratore .

Like any educated Roman of his day, Cicero spoke Greek from childhood . His father, who was disabled from exercising military or political office, gave him access to classical education. His great talent, which his father promoted with ambition, became apparent at an early age. According to Plutarch , Cicero was already a celebrity as a student. After the death of Crassus in 91 BC He studied law with Quintus Mucius Scaevola , as well as rhetoric , literature and philosophy in Rome, together with Titus Pomponius Atticus , who was his friend and “second brother” and later also his publisher . After initially studying the translation of Greek poets such as Homer , he turned to philosophy at the age of about twenty and translated the philosophical vocabulary into Latin. His teacher was the Platonist Philon von Larisa , the last scholarch of the Platonic Academy , who lived in 88 BC. Had fled Athens and died in Rome in 84/83.

First successes

After his military service in the Confederate War under Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo and Sulla, Cicero gained his first experience as a litigation speaker ( Latin orator ). Even as a young man, Cicero listened with interest to the famous lawyer Quintus Mucius Scaevola in order to learn from him. His first recorded court speech comes from the year 81 BC. BC (Pro Quinctio) . In the following year, in his first murder trial, he defended Sextus Roscius , who was accused of patricide, and obtained his acquittal by convicting the accusers, two relatives of Roscius and the influential freedman Lucius Cornelius Chrysogonus , of having planned and carried out the murder themselves out of greed. Since Chrysogonus, who had completed the proscription list on his own , was a favorite of Sulla, Cicero put himself in danger through this process.

79 BC Cicero continued his studies in Greece and Asia Minor , which were then part of the Roman Empire. Perhaps this trip was an evasion of feared hostility because of the process in the previous year. First he went to Athens, where he stayed for half a year. There he took part in the lessons of the philosopher Antiochus of Askalon , who combined stoic with platonic ideas and had founded his own school. On Rhodes Cicero visited the stoic Poseidonios , with whom he became friends, and the great orator Apollonius Molon . He learned Molon's simple style as well as the arts of captivating the listener while sparing his own voice. 77 BC He returned to Rome. He then began his career as a politician and lawyer.

Political career

Cursus honorum

Because of his success in the case of Sextus Roscius, Cicero enjoyed great prestige on his return from Greece. As a homo novus , this helped him to achieve all offices of the cursus honorum at the required minimum age ( suo anno ) .

He was like that in 75 BC. BC Quaestor in Sicily , where he had to secure the grain supply for Rome. There he found the tomb of Archimedes . The honesty of his administration earned him the lasting respect of the Sicilians.

He laid the foundation for his political career in 70 BC. When he represented the communities of Sicily in the process that they brought against the corrupt governor Gaius Verres (73-71 BC) for blackmail. Although Verres' political friends would have liked to help him acquittal, the evidence that Cicero gathered in a short time was so overwhelming that Verres left Italy before the verdict. This process also brought Cicero the position of first speaker in Rome, since he was able to outdo Quintus Hortensius Hortalus , the defender of Verres, who had been the most respected speaker until then .

For the year 69 BC Cicero was elected aedile . In this role he organized the compulsory games, which was also an important measure to secure his further political advancement. It is not clear from the ancient sources whether he officiated as a " curulic " (as is often assumed in the literature) or as a plebeian aedile. Otherwise, he did not particularly excel in the office of aedile, but mainly continued his business as a lawyer in those years, which made him a defender in numerous important criminal proceedings.

Cicero became praetor in 66 BC. The lot assigned him under the praetors the office of chairman of the court for extortion ( repetition proceedings ), a matter with which he had already dealt emphatically as a lawyer. That year he gave the speech de imperio Cn. Pompei, in which he supported the Lex Manilia , the supreme command in the war against Mithridates VI. of Pontus instead of Lucullus awarded Pompey, who was unpopular with the Senate majority. Cicero did not take the side of Pompey, but spoke for the "entire Roman people".

His opponents in the election campaign for the consulate were Hybrida and Catiline , who neither shrank from bribery and violence. Cicero gave a speech in toga candida against their machinations . What is meant by this is the candidate's white toga for the consulate, which was supposed to demonstrate purity and incorruptibility. Cicero won the election with the votes of all the Centuries and in 63 BC he held office. The office of consul, which for him as a climber from the knighthood ( ordo equester ) meant a special distinction.

consulate

Cicero began his consulate with an attempt to resolve the problem of land distribution and especially compensation for those who had to sacrifice their land to the growing city. Three speeches de lege agraria have been preserved.

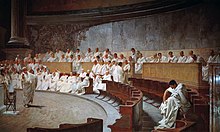

During his consulate, the Catiline conspiracy came about , but it was betrayed and, with the help of Cicero, was nearly stifled. During the Senate deliberation (see Cicero's speeches against Catiline ) it was Cato who pleaded for the death penalty, but later Cicero had to take responsibility for the execution of the Catilinarians, as the Senate had previously issued an emergency resolution to the consuls with measures to save the state had commissioned.

His performance in cracking down on the attempted coup was undisputed even by critics of his contemporaries like Sallust . Of course, he himself tended to emphasize his own achievements , not least because, as homo novus, he could not refer to important ancestors. Theodor Mommsen's famous criticism, which ascribes Cicero the “talent to break in open doors”, tries to discredit him as a “statesman without insight, opinion and intention” and ultimately only allows him to be regarded as a great stylist, is hardly recognized by today's research divided; Rather, it tries to do justice not only to Gaius Iulius Caesar , who was singled out by Mommsen , but also to his republican-oriented opponent Cicero, who, always concerned about the welfare of the res publica libera, interwoven republican ideals with the concept of a Roman ideal state ruled by the Senate Government should be composed of educated, intelligent and patriotic men who put the state good above their own interests.

After the consulate

61 BC Caesar wanted to win over Cicero to participate in the later triumvirate with Crassus and Pompey, but Cicero refused because he saw the republic endangered. As a result, his political influence declined. His opponents - especially the tribune Publius Clodius Pulcher , whose hatred Cicero manifested itself in the Bona Dea scandal in 62/61 BC. Had moved - 58 BC. A new retroactive law, which outlawed those who caused the death of a Roman citizen without trial, that is, robbed of his civil rights and his possessions, and applied it to the death of the Catilinarians. On the night before the ratification of the law of outlaw by the people's assembly, Cicero left Rome on the advice of his confidants after he had made an offering, a statue of Minerva , in the Temple of Jupiter . He went to Thessaloniki and thus prevented a banishment by a judicial verdict. He later emphasized that he had never renounced his civil rights and that Terentia had also insisted on the validity of the marriage. His property was expropriated, his estates plundered and his house on the Palatine Hill burned down. Clodius had part of the property dedicated to the goddess Libertas . Cicero was only allowed to approach Italy within 500 miles . If he breached the ban, he and all those who were supposed to support him face the death penalty.

On August 4th, 57 BC Despite Caesar's concerns, Cicero was called back from Greece by the Pompeian Titus Annius Milo and by a unanimous decision of the people's assembly by the Senate, which lifted the ban on Cicero and thus restored him to his previous legal position, and was enthusiastically celebrated on his return. The two speeches of thanks to the people and the Senate bear witness to this. However, he did not succeed in regaining political power. From this time on he became more active as a writer, especially with his political and philosophical writings. His main rhetorical work De oratore “About the Redner” was created during this time, as well as De re publica (“About the State”) and De legibus (“About the Laws”), two philosophical writings on the ideal state based on Plato's Politeia and Nomoi .

Cicero initially placed hopes in Caesar's intelligence and political abilities and supported him in 56 BC. BC even in his speech De provinciis consularibus on the question of whether the Senate should continue to cede the province of Gaul to Caesar or hand it over to one of the consuls of last year. In the course of time, however, he again became Caesar's political opponent, because he saw the republic threatened by his striving for power.

After Clodius 52 BC Was slain by Milo on the Appian Way , Cicero defended his enemy's murderer, albeit unsuccessfully, because Milo had to go into exile.

Cicero was born in 51 BC. Sent to Cilicia as governor . His brother accompanied him as a legate . Because the Parthians fought among themselves, the province was quite peaceful. Cicero was only involved in a few fighting and captured a mountain fortress, for which he was proclaimed emperor by his soldiers .

As Cicero in 49 BC When he returned to Rome in the 3rd century BC, the civil war between Caesar and Pompey was imminent. Cicero tried again to mediate in the Senate, but the Senate declared Caesar to be an enemy of the state when he crossed the Rubicon . Cicero joined Pompey and left Italy with brother and son. After Pompey's death in 48 BC However, he broke with his followers and returned to Italy, where he waited in Brundisium until Caesar found him in 47 BC. Chr. Pardoned. However, this did not prevent Cicero from composing an eulogy for Cato, who died by his own hands after the lost battle at Thapsus . He also campaigned for Pompey's followers in several speeches before Caesar.

In the following years he turned more to literature, this time less about politics: he dedicated several writings to his friend Marcus Iunius Brutus , including Brutus, a history of rhetoric that he - like the Republic - in the Saw danger of doom. In addition, he wrote several works on ethical topics.

Cicero's relationship with Caesar

In many of his writings, Cicero refers to his contemporary Gaius Julius Caesar . His relationship with this politician was increasingly ambivalent. When Cicero in 60 BC BC belonged to the Optimates , he had developed the plan to pull Caesar away from the "irresponsible hustle and bustle of the popular " to the side of the Optimates, who had set themselves the task of "conserving" the community. Cicero praised Caesar's role as “savior of the fatherland” in the Gallic War . But since he did not succeed in getting Caesar on his side, he sided with Pompey in the civil war , but without really being convinced of him. Nevertheless, like many others, he was pardoned by Caesar after the end of the civil war.

When Caesar in 46 BC With Marcus Claudius Marcellus , who had pardoned a determined opponent, Cicero welcomed this as a decisive political turning point. With this act of grace, according to Cicero, Caesar's political action almost corresponds to the ideal that he had developed in the speeches against Catiline and that ties in with Plato . He emphasized that Caesar's “war achievements” would not bring this lasting fame, but a wise policy that regulates the “pardoned” and the libera res publica (the free community). In the first book of de officiis , Cicero emphasizes the statesman's clementia several times . In a few letters to friends he praised Caesar's humanitas .

Since Caesar expanded his power at the expense of this libera res publica , Cicero became more and more of Caesar's opponent. In May 45 a statue in honor of Caesar was consecrated in the Temple of Quirinus and on the Capitol , which Cicero noted with indignation. Because, in Cicero's opinion, Caesar thereby placed himself above Roman society, he increasingly despised him. In de officiis he intensifies this attitude. He describes Caesar as a tyrant and "wild beast". He even received congratulations on the murder of Caesar, although he was not privy to the plans of the conspiracy.

Proscription and Death

Cicero was not involved in the conspiracy against Caesar , but his statements showed his triumphant joy over the death of the "tyrant", although he criticized the conspirators' lack of planning and foresight, noting that the attack was carried out with the courage of men but has been carried out to the mind of children. In addition, it quickly became apparent that Caesar's consul, Marcus Antonius, was seeking his successor in sole rule. Now Cicero opposed Antonius and with his 14 Philippine speeches , which he had named after the model of the speeches of Demosthenes against Philip II of Macedonia , became the spokesman for the republican faction in the Senate. Thereby he regained part of his former political influence and gained a great reputation, but also reaped the irreconcilable hostility of the passionately attacked. The first speech, given on September 2, 44 BC. BC, ended the armistice between Antony and the republicans around Cicero. The second speech contained violent (if not entirely unfounded) personal abuse against Antonius. He expressed his regret that Antony had not been eliminated on the Ides of March (the anniversary of Caesar's death).

After that, Cicero endeavored, if not without reservations, to persuade Octavian , who had appeared in Rome and hired veteran troops on his own initiative, to go to war against Antony with the backing of the Senate. He hoped for his intellectual abilities, but at the same time feared the personal power interests of the then barely twenty-year-old, which again unleashed the civil war. The cause of the republic even seemed to be victorious for a time. As suspected by Cicero, however, Octavian demanded the first successes in the summer of 43 BC. The consulate for himself and then publicly joined with Antonius and Marcus Lepidus to form the second triumvirate . The three triumvirs decided on proscriptions against their political opponents. Cicero was high on Antony's death list .

On December 7, 43 BC At his behest, he was killed by Centurion Herennius and the military tribune Gaius Popilius Laenas while fleeing . The body was dragged mutilated through the streets of Rome, head and hands were displayed on the rostra , the speaker's platform, in the Roman Forum . Fulvia , who was married successively to his enemies Clodius and Antonius, is said to have pierced his tongue with her hairpin according to Cassius Dio . Cicero's brother and son fell victim to the same proscriptions.

Marriages and children

Cicero's first wife was named Terentia . She came from a respected family and possessed a considerable fortune which she managed independently. Her half-sister was a vestal virgin , which underlines the high rank of her family. Plutarch emphasizes Terentia's austere manner several times; she was the dominant person in the marriage. The marriage lasted between 80 and 76 BC. Closed, but probably only after Cicero's return from Greece. Terentia used the reputation of her family and her dowry of one hundred thousand denarii as well as her other assets to promote Cicero's career. She was also involved in the Bona Dea scandal, according to Plutarch. There are some letters from Cicero to his wife that show Terentia's ambition for her husband and her confidence in his abilities. The first of the 24 letters that have been preserved date from the time when Cicero 58 BC. Had to go into exile and are very loving. Later the letters exchanged between them became shorter and more impersonal. After more than 30 years of marriage, Cicero directed 47/46 BC. Plutarch reports a divorce for reasons that are ultimately not clear. Terentia outlived her husband by several decades.

The daughter Tullia (born August 5 between 79 and 75 BC; † February 45 BC) emerged from the marriage with Terentia . Tullia was married three times, first to Cicero's gifted pupil Gaius Calpurnius Piso Frugi, who was 58 BC. Was quaestor and campaigned for the return of his father-in-law from exile. However, he died as early as 57 BC. Her second husband, Furius Crassipes, settled around 51 BC. Divorced from her after which she married Publius Cornelius Dolabella against the will of her father , a follower of Caesar and at the time her father's opponent in litigation. Although she was soon unhappy about Dolabella's way of life, Cicero, as he himself wrote, advised her against a divorce for political reasons. When they 45 BC Chr. Died after giving birth, he made great reproaches for this. His consolatio ad se ipsum “ Consolation to myself”, which he wrote on the occasion, is only known from quotations. A letter of comfort from Servius Sulpicius Rufus has survived, in which his friend reminds him of the sufferings of others and admonishes him to endure his grief equally bravely.

The only son Marcus was born around 65 BC. Born in BC. Cicero had high expectations of him and took him in 51 BC. With to Cilicia . For him he wrote the rhetorical text Partitiones oratoriae and dedicated it to it in 44 BC. Chr. De officiis , a treatise on practical ethics . Marcus joined in 49 BC As a soldier to Pompey and later his son Sextus and fought on the side of the defeated in the civil war. Octavian later pardoned him and appointed him in 30 BC. To co-consul.

Shortly after his divorce from Terentia, Cicero married in November 46 BC. As a 60-year-old he was about 15-year-old rich ward Publilia in order to be able to repay Terentia's dowry with her dowry. The marriage was criticized and ridiculed, especially because of the age difference. After the death of his daughter, however, the marriage was divorced a few months later.

Works

Cicero is considered to be the most important exponent of philosophical eclecticism in antiquity. His thinking contains elements of the Stoa as well as those of other thinkers, especially those of Plato .

Cicero's prose marks him as a master of the Latin language . He shaped it in such a way that it was suitable for rendering Greek philosophy, and so conveyed Greek philosophy , especially the teachings of the Stoa and the so-called New Academy, to the educated Roman public . Many of the works from which he drew can only be understood in their Latin rendering, apart from fragments and quotations. His political writings provide us with important sources on the political unrest that characterized the late Republican period and allow us to understand his positions. He also became famous for his speeches against Verres (70 BC), against Catiline (63 BC) and against Marcus Antonius (44 and 43 BC).

Talk

His portrayal of the history and upward development of Latin rhetoric in Brutus lets Cicero confidently end with his name. Since Quintilian at the latest , Cicero's fame as a 'classical' role model has been unchallenged, and he is still referred to as the outstanding speaker of Roman antiquity . Cicero published most of his speeches himself; 58 speeches are preserved in the original text (partly incomplete), around 100 are known through titles or fragments.

Cicero's oratory work can be divided into two groups: political speeches before the Senate or the people and defense speeches in court. The defense speeches also often had a political background.

As a prosecutor in a criminal case , Cicero appeared only once, namely against Gaius Verres . He owed his success to his argumentative and stylistic art, which knew how to adapt perfectly to the subject and audience (cf.Cicero's programmatic statements in the orator ), and above all to his clever tactics, which also adjusted entirely to the respective audience and opinions of various philosophical or political Bringing schools together eclectically , partly because it was his own view, but also to accommodate the public and achieve his goals.

| year | title | translation | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 81 BC Chr. | Per P. Quinctio | "For Publius Quinctius" | The oldest surviving court speech by Cicero for the plaintiff in a civil process . The subject of the dispute is the legality of previous acts of seizure of the defendant sex. Naevius against Cicero's client P. Quinctius. The other side's lawyer is Q. Hortensius Hortalus, judge C. Aquilius Gallus. |

| 80 BC Chr. | Pro sex. Roscio Amerino | "For Sextus Roscius from Ameria" | Defense speech in court, Cicero's first plea in a murder trial. Sextus Roscius was charged with parricide. During the civil war, relatives had taken the property of Roscius' father and are now trying to secure the loot by accusing the legitimate heirs of murder. Cicero obtained an acquittal . |

| approx. 77 or 66 BC Chr. | Per Q. Roscio Comoedo | "For the actor Quintus Roscius " | Speech for the defendant in a civil lawsuit. |

| 72/71 BC Chr. | Pro M. Tullio | "For Marcus Tullius" | Defense speech in court |

| 69 / approx. 71 BC Chr. | Per A. Caecina | "For Aulus Caecina" | Speech for the plaintiff in civil litigation before a recuperative court (a jury for cases of special public interest). The legal basis is the interdict de vi armata (property protection in the event of eviction by force of arms). The lawyer for the other side is C. Calpurnius Piso, both sides apparently rely on the authority of the lawyer Gaius Aquilius Gallus . |

| 70 BC Chr. | Divinatio in Caecilium | "Pre-trial speech against Quintus Caecilius" | Preliminary proceedings to take on the charges against Gaius Verres. Q. Caecilius Niger was Quaestor in Sicily under Verres and is now applying for the role of Prosecutor. After Cicero, however, he was himself involved in the machinations of Verres. |

| In Verrem actio great | "First speech against Verres" | Indictment speech in the trial against Gaius Verres for blackmailing provincials (crimen pecuniarum repetundarum) | |

| In Verrem actio secunda I – V | "Second charge against Verres 1–5" | These five speeches were not delivered, but published in writing because Verres had voluntarily gone into exile. | |

| 69 BC Chr. | Per M. Fonteio | "For Marcus Fonteius" | Defense speech in court |

| 66 BC Chr. | De imperio Cn. Pompei (De lege Manilia ) | "On the supreme command of Gnaeus Pompeius" / "On the law of C. Manilius" | Speak to the people |

| Per A. Cluentio Habito | "For Aulus Cluentius Habitus" | Defense speech in court | |

| 63 BC Chr. | De lege agraria (Contra Rullum) I-III | "About the settlers law" / "Against Rullus" | Speeches of the consulate year, given in the Senate (I) and before the people (II / III); a fourth speech is lost. |

| Pro Murena | "For Murena " | Defense speech in court | |

| Per C. Rabirio perduellionis reo | "For Gaius Rabirius accused of high treason " | Defense speech in court | |

| In Catilinam I – IV | "Against Catiline 1–4" | Speeches against Lucius Sergius Catilina : Speeches on November 7th and 8th, 63 BC Before the Senate (I) and before the people (II); Speeches for the discovery and punishment of Catiline's followers on December 3rd before the people (III), on December 5th before the Senate (IV) | |

| 62 BC Chr. | Pro Archia | "For Archias" | Defense speech in court |

| Per P. Cornelio Sulla | "For Publius Cornelius Sulla " | Defense speech in court | |

| 59 BC Chr. | Per L. Valerio Flacco | "For Lucius Valerius Flaccus " | Defense speech in court |

| 57 BC Chr. | De domo sua ad pontifices | "About his own house, to the pontifical college" | Plea on my own behalf: During Cicero's exile, his opponent Clodius had consecrated part of Cicero's property on the Palatine Hill to the goddess Libertas; Cicero invalidates this dedication in order to obtain a return. |

| Oratio cum populo gratias egit | "Thanksgiving to the people" | Thank you to everyone who campaigned for Cicero's return from exile and announced his return to politics | |

| Oratio cum senatui gratias egit | "Thanks to the Senate" | Thank you to everyone who campaigned for Cicero's return from exile and announced his return to politics | |

| 56 BC Chr. | De haruspicum responso | "About the report of the victims showers" | Clodius referred a passage about the profanation of sanctuaries in a report by the Haruspices on Cicero's Palatine property (see De domo sua ) and called for the demolition of Cicero's house under construction there. Cicero defends himself against these and other allegations with an appeal to the Senate, in which he declares that Clodius is the cause of all the evils mentioned in the report. |

| De provinciis consularibus | "About the consular provinces" | Talk to the Senate about the consular provinces | |

| In P. Vatinium | "Against Publius Vatinius" | Indictment speech against Publius Vatinius , during the questioning of witnesses in the trial against P. Sestius (see Pro P. Sestio ) | |

| Per M. Caelio | "For Marcus Caelius" | Speech in defense of Marcus Caelius Rufus in court | |

| Per L. Cornelio Balbo | "For Lucius Cornelius Balbus " | Defense speech in court | |

| Per P. Sestio | "For Publius Sestius " | Defense speech in court | |

| 55 BC Chr. | In L. Calpurnium Pisonem | "Against Lucius Calpurnius Piso " | political accusation speech |

| 54 BC Chr. | Pro Aemilio Scauro | "For Aemilius Scaurus " | Defense speech in court |

| Per cn. Plancio | "For Gnaeus Plancius" | Defense speech in court | |

| 54/53 or 53/52 BC Chr. | Pro Rabirio Postumo | "For Gaius Rabirius Postumus " | Defense speech in the follow-up to the trial against Aulus Gabinius for blackmailing provincials (crimen pecuniarum repetundarum). It is about the whereabouts of bribes in connection with the reinstatement of Ptolemy XII. Neos Dionysus as King of Egypt. |

| 52 BC Chr. | Per T. Annio Milone | "For Titus Annius Milo " | Defense speech in court, which, however, was not delivered in the published perfection; includes inter arma enim silent leges |

| 46 BC Chr. | Pro M. Marcello | "For Marcus Marcellus " | Acceptance speech for the pardon of the opponent of Caesar M. Marcellus by Caesar (act of his clementia ), given before the Senate, addressed to Caesar as dictator, so that he can restore the libera res publica . |

| 46 BC Chr. | Pro Q. Ligario | "For Quintus Ligarius " | Defense speech for Q. Ligarius, addressed to Caesar as dictator |

| 45 BC Chr. | Pro lively Deiotaro | "For King Deiotarus " | Defense speech for King Deiotarus, addressed to Caesar |

| 44/43 BC Chr. | Philippicae orationes | "Philippine Speeches" | Speeches against Mark Antony, based on the Philippica of the Attic orator Demosthenes against the Macedonian King Philip II. |

Philosophical writings

In his philosophical writings, Cicero introduced his Latin readers to Greek philosophy . For this he created a new Latin terminology. He himself cannot be clearly assigned to any philosophical school; he was strongly influenced by the skepticism of the "Younger Academy" . He rejected Epicurean hedonism .

- De re publica ("About the State") is 54–51 BC. BC and only preserved in fragments. The last section, Somnium Scipionis ("Scipio's Dream"), washanded downseparately with the commentary of Macrobius and was also known in the Middle Ages. Based on Plato's Politeia , Cicero explains the advantages and disadvantages of the different state systems in the form of a dialogue. In contrast to Plato, his ideal state is not fiction, but the Roman Republic .

- De legibus (“About the Laws”) contains, like Plato's nomoi, the practical application of the doctrine of the state. Conceived as a dialogue between Cicero himself, his brother Quintus and his friend Atticus, the book shows how the laws are based on natural law . The work was probably created at the end of the 50s BC. And is only about half preserved.

- Paradoxa Stoicorum (justification of paradoxical ethical doctrines from the school of the Stoics ). 46 BC Chr.

- The lost Consolatio ("consolation" after the death of his daughter) was mentioned by Cicero in the spring of 45 BC. In a letter to Atticus.

- Hortensius sive de philosophia ("Hortensius or about philosophy") originated in the spring of 45 BC. After the model of Aristotle ' Protreptikos . The dialogue between Cicero, Catulus, Hortensius and Lucullus, preserved only in fragments, is said to have given Augustine an impetus to convert to Christianity.

-

Academica priora (earlier version of the books on the epistemology of academics ). 45 BC Chr.

- Catulus (Dialogue 'Catulus'), 1st part of the Academica priora, largely lost

- Lucullus (dialogue, Lucullus'), the second part of the Academica priora, get

- Academici libri or Academica posteriora (later version of the treatise on the epistemology of academics in four books; apart from a few fragments, only the beginning of the first book is preserved - about a quarter of the 'Lucullus')

- De finibus bonorum et malorum ("About the greatest good and the greatest evil") was created in June 45 BC. And is dedicated to Brutus. In three dialogues, different approaches of Greek philosophy, which concern the goal and the meaning of life, are presented.

- The Tusculanae disputationes ("Conversations in Tusculum "), originated in the second half of 45 BC. Chr. And also dedicated to Brutus, they deal with ethical issues such as dealing with suffering and death. The most important thing to live happily is virtue .

- Cato maior de senectute (" Cato the Elder on Age") was written in 45/44 BC. BC and is a fictional conversation between (the older) Cato, P. Scipio minor and C. Laelius Sapiens , in which Cato tries to refute all reproaches made against old age. The reason so many old people complain about their age is because of their character. The dialogue is dedicated to Atticus.

- Laelius de amicitia ("Laelius on friendship") wrote Cicero 45/44 BC. "As a friend for the friend" Atticus. Again Scipio and Laelius appear as ideal types of friends. The dialogue ends with the praise of virtus as the basis of true friendship.

- In De natura deorum ("Of the essence of the gods"), originated in 45/44 BC. Dedicated to Chr. And Brutus, Cicero reproduces a conversation that the Stoic Q. Lucilius Balbus, the Epicurean C. Velleius and the academic C. Aurelius Cotta, representatives of the three most important ancient schools of philosophy, spoke about the nature of the gods and their relationship to the People about thirty years earlier.

- In De divinatione ("About fortune telling"), a 44 BC. The dialogue between Cicero and his brother, which emerged in the 4th century BC, separates Cicero between furor , direct inspiration, above all through dreams, and the oracles that need to be interpreted . He explains the former as natural processes of the human soul, while the sign interpreters only make use of the superstitions of their fellow men. De divinatione is an important source for our knowledge of the Roman religion .

- De fato (“About fate”) follows immediately after De divinatione and De natura deorum . In it, Cicero discusses with Aulus Hirtius the views of the philosophical schools on thequestion of free will . The middle of 44 BC Scriptures begun in BC remained unfinished.

- De gloria ("About fame"). July 44 BC Chr. Lost.

- De officiis ("About the duties") is in autumn / winter 44 BC. And addressed in letter form to his son Marcus, who was studying in Athens. In it he quotes the otherwise lost book of Panaitios of Rhodes on duties. The first book is about duties and virtues. Cicero names prudentia - prudence, iustitia - justice, fortitudo - bravery and temperantia - moderationas the most important virtues, as Plato alsoliststhem in the Politeia and the Nomoi . In the second book he shows how virtuous behavior can win the sympathy of those around you and thereby benefit yourself. Politicians serve as examples. In the third book, he addresses the possible conflict between virtue and utility, also using numerous examples from history, whereby virtue must always have priority.

Rhetorical writings

As with Cicero's life and work it is difficult to separate anyway, the distinction between philosophical and rhetorical writings in particular is practical and clear (it is therefore retained here), but does not correspond to Cicero's own intention and view. In his first surviving work ( De inventione I 1–5), he explains that wisdom, eloquence and statecraft originally formed a unity that contributed significantly to the development of human culture and that needs to be restored (cf. Büchner, Cicero (1964) 50 -62). This unity is envisaged as a model for both Cicero's theoretical writings and his own vita activa (for example: “politically committed life”) in the service of the state - at least as he himself idealized and wanted to see them.

It is therefore not surprising that Cicero uses rhetorical means to develop his philosophical writings and that his theory of rhetoric is based on philosophical principles. He attributes the separation of wisdom and eloquence to Socrates as a “rift between tongue and intellect” ( De oratore III 61) - it is probably more likely to be traced back to Plato - and tries to resolve it again through his own writings. In his opinion, philosophy and rhetoric depend on each other for the best possible realization (see, for example, De oratore III 54–143); Cicero confesses that “I became a speaker [...] not in the rhetoricians' training centers, but in the halls of the academy” ( Orator 12). He is alluding to the lessons he received in Rome from Philon von Larisa and later in Athens from Antiochus von Askalon.

The preserved rhetorical theoretical works in chronological order:

- De inventione ("About the discovery [of the talking material]"): Probably between 85 and 80 BC. These first two books emerged from an incomplete overall presentation of rhetoric. Cicero himself later rejected them in favor of his more in-depth portrayal in De oratore, but despite their fragmentary character they served as a textbook until the Middle Ages . In the first book, the completed part deals with basic rhetorical terms (I 5–9), the doctrine of status following Hermagoras von Temnos (I 10–19) and the parts of the speech (I 19–109); The second book deals with the argumentation technique, especially in the court speech (II 11–154, again arranged according to the status theory) and briefly in the popular speech (II 157-176) and the celebratory speech (II 177-178). In terms of content, Cicero's statements are often very similar to the so-called rhetoric wrongly handed down to Herennius under his name , so that the exact relationship between the two writings was long disputed in scholarship. In any case, both works were created around the same time and are based directly or indirectly on the same or related, ultimately Greek sources. However, since there are literally identical passages, they probably had a common Latin source, perhaps a treatise by the same teacher, as a mediator mainly of Greek content.

- De oratore ("About the speaker") - Ciceros 55 BC. The main work on rhetorical theory (in three 'books'), which was created in BC, should not be confused with the later orator of almost the same name; Also the main speakers Crassus (140–91 BC) and Antonius (143–87 BC) are greats of the past and are not identical with the bearers of the same name in the 1st and 2nd triumvirates.

- Partitiones oratoriae ("Classifications of Speech Art"): This probably around 54 BC. BC, when Cicero's son Marcus studied rhetoric, the 'catechism', which was created in the form of a fictional question and answer game between son (C.) and father (P.), deals with the theory of rhetoric, especially terms and schematic classifications. Cicero's originality is less evident here in the overall dry form than in the critical examination of traditional school rules and in philosophical influences, especially in the third part in the treatment of virtues, goods and causes.

- Brutus: The book named after Marcus Junius Brutus was published at the beginning of 46 BC. Writes and treats the history of Roman rhetoric up to Cicero himself in the form of a dialogue between Cicero, Brutus and Atticus . After an introduction (1–9), Cicero's lecture begins with Greek rhetoric (25–31) and emphasizes that the Oratory as the most difficult of all arts comes to completion late. While he laboriously portrays the older Roman speakers secondhand (52-60), Cicero speaks from Cato from his own knowledge of the text; Lucius Licinius Crassus and Marcus Antonius Orator , the two protagonists of De oratore, are compared in detail (139ff.). After a digression on the importance of the audience judgment (183-200) and the treatment of the speakers to Hortensius (201-283) Cicero, the charges of Atticism back (284-300). The work culminates in a not exactly modest comparison between the eloquence of Hortensius and Cicero himself (301–328). Cicero's main intention is less a literary history, especially not in today's sense, than a defense against the allegations of the atticists, including Brutus. He writes about him that his rich style is a sign of Asianism .

- Orator ("Der Redner") - not to be confused with the De oratore, which is almost of the same name. That in the summer of 46 BC This book, written in the 4th century BC, is addressed to Brutus and creates an ideal image of the perfect speaker. Contrary to the controversy at the time between atticists , who - like Brutus - demanded the simplest and most precise language possible from the speaker, and Asianists , who represented an artfully sophisticated language, Cicero demands that the best speaker like Demosthenes master all levels of style, depending on the topic the speech, even within the speech must alternately apply. For this he needs a comprehensive, above all philosophical, education. Only in this way can he fulfill the three tasks of the speaker: probare, delectare, flectere (“prove, delight, bend”), to which Cicero assigns the three styles described in detail (76–99). - In the main part, Cicero deals with the classic work stages of the speaker, butonly briefly deals with thelocation ( inventio, 44-49) and the arrangement ( dispositio, 50) of the speaking materialaccording to his topic, but deals in detail with the style ( elocutio, 51–236), especially with rhetorical figures and sentence structure including prose rhythm .

- Topica (" Topik , Evidence"). July 44 BC Chr.

- De optimo genere oratorum (“On the best kind of speaker”): This maybe around 46 BC. BC, according to other assessments as early as the 50s BC. This short script is an introduction to the translation of the speeches of Demosthenes and Aeschines for and against Ctesiphon . The introduction mainly attacks the Roman atticists , with much the same arguments as in the orator. The translation itself has not survived, and it is unclear whether Cicero ever carried out it. The authenticity of the writing has already been questioned by Asconius Pedianus in antiquity and further into modern times.

More fonts

Cicero's other works include a consolation book, contributions to historiography , poetry (about his own consulate : de consulatu suo ) and translations. Much of this work is lost. From the poems we have received some quotations in the works of Cicero and other authors. These fragments, however, identify Cicero as one of the most important - perhaps the most important - Latin poets before Catullus and the other neoterics , but also gave contemporaries cause for ridicule and malice because of Cicero's overconfidence. Of the translations, large parts of a translation of Plato's Timaeus ( Timaeus ) have survived , which Cicero probably never published, but only made as a working translation. In addition, we have the fragments, mostly cited as Aratea des Cicero , from a copy of the Celestial Apparitions by the Hellenistic poet Aratos von Soloi , who was one of the most influential authors of his time.

Letters

The letters of Cicero were rediscovered in 1345 and 1389 by Petrarch and the Florentine state chancellor and promoter of humanism Coluccio Salutati . A total of more than 900 letters were found, which initially triggered enthusiasm that turned into disappointment, as Cicero did not always correspond to the ideal of a defender of the republic, as he portrayed himself in his speeches and political writings.

The letters were read by Cicero's secretary Tiro in 48–43 BC. Collected and archived. There are 4 categories:

- Letters to family members and friends (epistulae ad familiares)

- Letters to the brother Quintus Tullius Cicero (epistulae ad Quintum fratrem)

- Letters to Marcus Iunius Brutus (epistulae ad M. Brutum)

- Letters to Atticus (epistulae ad Atticum)

reception

The aftermath of Cicero through two millennia fluctuated greatly in intensity. It affected different areas of his activity. Most important of all was his role as a teacher of rhetoric and as a stylistic model that sets the norm for a “classical” Latin language and defines its vocabulary. His teaching of Greek philosophy to the Latin-speaking world was also momentous, for which he created suitable linguistic means of expression. Much attention was also given to his performance as a statesman, which was controversial.

The broad impact of Cicero's philosophical writings resulted from their didactic orientation. His ability to explain complex questions clearly and to provide information about various attempted solutions without imposing a specific solution on the reader was and is valued.

Antiquity

Since Cicero was a political opponent above all of Antonius, but at times also Octavian, he was one of those people who had a bad reputation in ruling circles in the years after his death. When Octavian established the principate and ruled as Emperor Augustus (27 BC-14 AD), Cicero was usually passed over in public as one of the leading figures of the defeated Republicans; to praise him could have been interpreted as a sign of oppositional sentiments. The great poets of the Augustan age - Horace , Virgil , Ovid , Properz , Tibullus - did not mention his name; Horace dared only vague allusions, but was an avid reader of the Tusculan Conversations and based his art theory not only on the Greeks, but also on Cicero.

The historians, on the other hand, could not simply ignore Cicero because of its historical significance. Cornelius Nepos , whose biography of Cicero has not survived, emphasized his ability to foresee political developments. Livius expressed himself appreciatively in his work , but distanced and also clearly criticized; he said that of all the misfortunes that befell him, Cicero had only duly endured death. The politician and historian Asinius Pollio , who was a follower of Caesar and Antony, wrote a description of the contemporary civil wars, of which only a few fragments have survived; in it he made Cicero appear in an unfavorable light. He accused him of lack of moderation in times of success and of bravery in times of misfortune and said that, as a lawyer, Cicero had saved evil people from punishment and thereby committed himself. Pollio's son Gaius Asinius Gallus even dared to belittle Cicero's literary achievements, which even political opponents used to acknowledge; he put his father above Cicero.

On the other hand, Octavian promoted Cicero's son Marcus, with whom he 30 BC. The consulate clad. When the Senate passed the damnatio memoriae of Cicero's main enemy Antonius, Marcus took over as consul to carry it out; he had the statues of Anthony destroyed and was able to take revenge for the death of his father. By approving this, Octavian indirectly distanced himself from the murder of Cicero, which he had then consented to, and gave the public the impression that this act could only be blamed on Antonius.

The continuing interest in Cicero led to the publication of his correspondence, which sometimes showed him in an unfavorable light; Seneca († 65) already knew her.

After Augustus' death it became possible again to express unreserved admiration for Cicero's political achievement. This was done by the historian Velleius Paterculus , who, as an enthusiastic supporter of the empire, was not suspected of being a republican. He followed the line already given by Livius to hold Antonius solely responsible for Cicero's death, and covered up the contradiction between Cicero's republican sentiment and the monarchical principle on which the empire was based. Cicero even found a defender in the imperial family: one of the works by Emperor Claudius that have not survived was a response to Asinius Gallus' criticism of Cicero. Asconius Pedianus wrote a commentary on Cicero's speeches, some of which has been preserved.

In the late first century, after the political antagonism between republican and monarchical sentiments had faded, the relationship of culturally relevant circles to Cicero was already completely unaffected. Pliny the Elder believed that Ciceros De Officiis should be read every day, even learned by heart, and was also enthusiastic about his achievements as a statesman and as the “father of eloquence”. His younger contemporary, Quintilian , a leading teacher of rhetoric, believed that Cicero was equal to any Greek speaker and made his style the norm. He said that by imitating the Greeks, Cicero combined "the strength of Demosthenes, the fullness of Plato and the grace of Isocrates " in his rhetorical achievements. He was rightly called a “king in court” by his contemporaries, and for posterity the name Cicero no longer stands for one person, but for eloquence par excellence. Quintilian also renewed Cicero's ideal as a speaker, according to which it is primarily not a question of technical skills, but of education as a prerequisite for true oratory; the perfect speaker (perfectus orator) is also a philosopher, he combines eloquence with wisdom.

Through Quintilian's judgment, which found its way into the ancient school system, Cicero became the authoritative stylistic model for classical Latin prose. A pronounced, often exclusive, preference for him, for which the term “Ciceronianism” became established in modern times, has been a core element of Latin classicism since Quintilian . Since Cicero spread Greek philosophical ideas in Latin, but his name is not associated with a specific idea or doctrine originating from himself, terms such as “Ciceronian” and “Ciceronianism” refer only to the literary adoption of his style, his vocabulary and his theory of rhetoric. Sometimes a preference for the literary genres preferred by Cicero is also meant. The often existing agreement with his political or philosophical views is not necessarily one of the characteristics of Ciceronianism.

In his dialogue about the speakers , Tacitus came to an equally very positive, but more nuanced judgment, in which he complained about the decline in the art of speaking. He saw in Cicero the real creator of Roman rhetoric, but made a distinction between youthful works, which were still rambling and too slowly aimed at the goal, and the exemplary masterpieces of the ripe times. Tacitus' friend Pliny the Younger was also an admirer and imitator of this “best example” . The Greek historian Plutarch wrote the oldest Cicero biography that has survived, as part of his parallel biographies of a Greek and a Roman, comparing Demosthenes and Cicero, the two most important speakers of the respective peoples at the time.

By the middle of the 2nd century, Marcus Cornelius Fronto was the leading teacher of eloquence. He founded an influential speaker school and was considered the Cicero of his time, which meant the highest possible praise. He too saw in Cicero the great model of the art of speaking - and also of the letter style - although he actually preferred the ancient expressions of Catos the Elder and Sallust to the "opulence" of Cicero.

In the third century, the historian Cassius Dio highlighted Cicero's weaknesses in his account of the late Republican period. He reproduced in great detail a fictional polemical speech by a Cicero opponent, but without identifying with it. He also let it through that Cicero had behaved unworthily by showing unphilosophical fear and weakness.

Even in late antiquity , Cicero's language remained the standard-setting benchmark. Quintus Aurelius Symmachus was hailed as the most important Latin-speaking speaker of his era by comparing him to Cicero. Macrobius made an important contribution to the reception of Cicero that lasted for centuries with his commentary on the Somnium Scipionis , which was eagerly read in the Middle Ages. In this work Cicero appears as a Platonist, his text is interpreted in the sense of a Neoplatonic cosmology and theory of the soul.

The educated Latin- speaking church fathers of late antiquity had an intense, but at times conflicting relationship with Cicero . They were not primarily interested in the politician and orator Cicero, as was previously the case, but mainly in the philosopher. The church father Laktanz was a teacher of rhetoric and was strongly influenced by Cicero's style. He said that Cicero had known as much philosophically as one could know with reason without divine revelation; he had refuted false things, but had no access to positive truth due to a lack of knowledge of Christian doctrine. In late antiquity, lactance was compared to Cicero, in Renaissance humanism he was called "the Christian Cicero" because of his achievements as a stylist. Even Augustine studied in his youth rhetoric. He was deeply impressed by Cicero, especially by his then popular dialogue Hortensius , an invitation to philosophy. The reading of Hortensius brought him to religious philosophy and thus on a path that eventually led him to conversion to Christianity. As a Christian, Augustine kept his high esteem for Cicero, whom he now saw as a forerunner of Christianity. The learned church father Hieronymus , who had received his literary training in Rome, had a far more problematic relationship with Cicero . In the fever he experienced a frightening dream vision in which he stood before the judgment seat of God and was accused of not being a Christian, but a Ciceronian (Ciceronianus es, non Christianus) . Hieronymus then promised to part with the books of Cicero in order to obtain God's grace, but he already knew texts from these works by heart and had to confess that he could not erase the knowledge he had already acquired from his memory. This brought him into serious trouble of conscience, as he regarded the study of such literature as sinful. Nevertheless, all of his works, including the later ones, were influenced by Cicero.

In the 6th century Boëthius wrote a commentary on Cicero's Topica .

middle Ages

The negative evaluation of the Cicero studies initiated by Jerome reached a climax with Pope Gregory the Great , who officiated from 590 to 604. He complained that the joy of Cicero's style kept young people from reading the Bible, so he suggested that the pagan orator's works should be destroyed. In the period that followed, occupation with Cicero fell sharply and remained at a low level for a long time. The ignorance was so great that the opinion was even expressed that Cicero and Tullius were two different people.

It was not until the Carolingian era that individual scholars such as Alcuin and Servatus Lupus von Ferrières became interested in him, and later also with Pope Silvester II (Gerbert von Aurillac, † 1003), who was particularly concerned with the speeches and imitated their style. From the 11th century, the reception increased significantly; De officiis was particularly well received, as this work deals with subjects which were also important for Christian moral teaching. The phrase “Tullian eloquence” was widespread, and was used to emphasize that an opinion was so firm that it could not even be shaken by Cicero's powers of persuasion. The topos , already used in late antiquity, was also popular that something was so indescribable that even Cicero (Tullius) would fall silent. He was called "Tullius". Some of his works were part of school reading. But it was praised more than actually understood and imitated. Often, knowledge about him was not drawn from his own works, but from those of the Church Fathers who had dealt with him. His letters were very little known.

The educated people particularly focused on his dialogues on old age ( Cato de senectute ) and on friendship ( Laelius de amicitia ), on De officiis and on the Somnium Scipionis commented on by Macrobius , whose subject matter of the afterlife interested medieval Christians. In the 12th century, the Cistercian abbot Aelred von Rievaulx wrote a work on spiritual friendship as a Christian counterpart to the dialogue Laelius de amicitia , with which he dealt. In rhetoric lessons, mainly Cicero's youthful work De inventione , from which he had later distanced himself, and the textbook Rhetorica ad Herennium , which was erroneously attributed to him, were used - both writings of a technical character that have little to do with Cicero's main concern, education. His rhetorical rules were also applied to the preaching technique. In the fine arts he was portrayed as the embodiment of rhetoric.

When pre-humanism (prehumanism) set in in Italy in the 13th century, interest in Cicero increased in literary circles. He was also held in high regard by scholastic scholars, even theologians. The Doctor of the Church Thomas Aquinas often referred to him and almost never contradicted his views. Even Dante quoted him often and said that the dialogue over the friendship greatly impressed him and had shown him the way to philosophy. He justified his use of the Italian vernacular (volgare) in literary works with reference to Cicero.

In the Byzantine Empire , Cicero was one of the most famous figures of ancient Rome; he was mainly known from Plutarch's Cicero biography, which was not available to the Latin-speaking scholars of the West. In the late Middle Ages Maximos Planudes translated the Somnium Scipionis and Macrobius' commentary into Greek.

Early renaissance

With the onset of the Renaissance , Cicero regained the authority of the undisputed stylistic model in the field of Latin prose. In the reconnection to him in Italian humanism , Francesco Petrarca played a central, pioneering role. In 1345 he discovered a manuscript in the cathedral library of Verona that contained hundreds of lost letters from Cicero. This discovery gave the humanists a new, direct access to the personality and political role of the Roman statesman. After concentrating on literary and philosophical aspects of his work in the preceding centuries, the newly discovered letters showed him as a person with human weaknesses, as a friend and family man. Now Cicero increasingly became the teacher of the humanists in the art of letter writing, and the letter as an art form spread. Petrarch, who rediscovered two of Cicero's speeches, even entered into a literary dialogue with him; In 1345 he wrote him two fictional letters in which he thanked him profusely for having conveyed to the humanists "the little elegance and art of representation" that they possessed (compared to their ancient model). At the same time, however, he also expressed disappointment about some of the behaviors of Cicero evident from the letters, which he disapproved of. For humanists like Giovanni Boccaccio and Coluccio Salutati it was the highest praise that their style was compared with that of Ciceros. Salutati was called "Monkey Ciceros" by a contemporary, which was meant as a compliment in context. In 1392 Salutati discovered further letters from Cicero in Verona, while Poggio Bracciolini found speeches that had been lost in monastery libraries. Leonardo Bruni wrote a biography of Cicero in 1415, the Cicero novus , in which he particularly emphasized that Cicero had succeeded in combining active, political life with contemplative, withdrawn life. The question of the relationship between these two ways of life, the vita activa and the vita contemplativa , had already been addressed by Cicero in the Middle Ages (up to the 13th century he was regarded as a key witness for the priority of a contemplative life), and the Renaissance humanists set it Discussion continued.

From the second half of the 13th century De inventione and the erroneously attributed textbook Auctor ad Herennium were also distributed in Italian versions.

The term studia humanitatis for the humanistic educational program was based on Cicero's term humanitas . The aim was to combine philosophical education with linguistic mastery. The starting point for this concept was Cicero's statement in De inventione that wisdom (sapientia) without rhetorical persuasiveness ( eloquentia , eloquence) is of little use to the state and that eloquence without wisdom can even cause it severe damage and never bring any benefit. Only the connection between the two is helpful. Lessons in the sense of this program should start early according to the humanistic view; the scholar and pedagogue Guarino da Verona exaggeratedly said that Cicero's writings should be given to children with their mother's milk.

Radical “Ciceronians” like Gasparino Barzizza , Guarino da Verona, Paolo Cortesi and Ermolao Barbaro did not want to tolerate any deviations from the classical Latin Cicero. Other humanists such as Petrarca, Angelo Poliziano , Leonardo Bruni and Gianfrancesco Pico della Mirandola advocated a freer relationship with the model. They said that one should not write as Cicero did, but as he did under the conditions of the present; it is better to imitate his spirit than to cling to stylistic externals. The differences of opinion resulted in heated debates.

Lorenzo Valla caused a sensation with his deliberately provocative claim that Quintilian was superior to Cicero as a master of rhetoric.

Early modern age

Towards the end of the 15th century, the term humanista (humanist), linked to Cicero's concept of Humanitas, was in use, initially as a professional title for holders of chairs in humanistic subjects, and from the 16th century onwards as a self-description for people with humanistic education.

Erasmus von Rotterdam († 1536) shared the humanists' general enthusiasm for Cicero, but criticized the widespread notion that among all Roman writers only this one had to be accepted and imitated as a stylistic authority. In his 1528 published work Ciceronianus or About the best way of talking , he distanced himself from what he saw as a slavish, pedantic imitation of the master. He said that one should not behave like a monkey, but like a son. The Ciceronian position had been formulated drastically by Paolo Cortesi: he would rather be Cicero's son than his monkey, but would rather be Cicero's monkey than another author's son. Erasmus argued that there was no uniform style of Cicero, but that his work was exemplary precisely because of its breadth of variation and adaptation to what is appropriate. On the other hand, Erasmus also admired the important Ciceronians among his contemporaries, among whom the Cardinal Pietro Bembo (1470–1547) stood out. Bembo insisted that the only way to learn the Latin language was to imitate, and if you imitate you should imitate the best. The debate about the appropriate relationship to the model Cicero continued into the 18th century. An important tool of the Ciceronians was the Thesaurus Ciceronianus created by Mario Nizolio , a dictionary of Cicero's usage of language with references and explanations.

While the strict Ciceronianism lost its attraction in the scholarly world in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, it caught on completely in the school sector, especially in the Jesuit school system. The main argument of the Ciceronians, already presented by Bembo, was that there is a moment of the highest perfection in the development of a language, which is to be recorded as the optimum and therefore has a role model character. The optimization sought in this way, however, had its price: Latin, which in the Middle Ages - especially in the epoch of scholasticism - was still very flexible, capable of development and in this respect “alive”, only became a fixed “dead” through the strict Ciceronianism of the conservative humanists “Language. The binding limitation to the classical style and vocabulary of Cicero meant a solidification that precluded further development.

In France the reception of Cicero was not as strong as in Italy, but there too the humanistic ideal of education prevailed, which included the ability to express oneself elegantly in Latin in the style of Cicero. In this sense, François Rabelais , among others, expressed himself . Erasmus's criticism of Ciceronianism met with strong rejection, for example from Julius Caesar Scaliger and Étienne Dolet. An exception to the mostly unreserved admiration of Cicero was the differentiated judgment of Michel de Montaigne , who did not shrink from criticism. Montaigne accused the Roman statesman of vanity and a lust for glory and said that he was a good citizen, but of a soft character. He criticized the philosophical works, especially those on moral subjects, as being too verbose, rambling, lacking in substance and therefore boring. Resounding evidence is lacking and the core of a problem is being circumvented rather than resolved.

In the German-speaking countries, Cicero's influence in the Protestant areas was relatively weak, although he was a school author here too and Luther had recommended his philosophical writings for reading. Cicero was read less for its own sake than to use its eloquence for one's own purposes. This hardly changed in the 18th century, especially since at that time the main focus was on ancient Greece.

Voltaire in particular emerged as an admirer of Cicero among the enlighteners . He valued him as an opponent of despotism and considered his philosophical achievements to be equivalent to those of the Greek philosophers. Voltaire wrote a play Catiline, or The Saved Rome . In it he made Cicero a hero and in 1751 he played his role in performances on private stages.

In North America was in the British colonies that will appeal to the republican tradition of antiquity in the leading circles of when were coming about detachment from the UK and the founding of the United States in the 18th century independence movement very popular. In countless speeches and writings, reference was made to the Roman "patriots" Cicero and Brutus as fighters against tyranny. John Adams , who was among the founding fathers of the new state and became the second president of the United States, believed that no one in all of world history had surpassed Cicero in uniting the abilities of a statesman and a philosopher. He saw in him the classic model of bourgeois virtue. Other founding fathers such as Thomas Jefferson and John Dickinson and publicists such as Josiah Quincy II and James Otis Jr. also adored Cicero and relied on his thoughts in their polemics against the monarchy and in advocating natural law . Jefferson read the original and liked to quote it. He emphasized his extraordinary appreciation for the philosophical attitude, patriotic sentiment and eloquence of the Roman statesman, but reprimanded him for being vague.

Modern

The French Revolution , whose spokesmen liked to invoke old Roman republican virtues, led to an increase in the traditional admiration of Cicero and at the same time gave it a new direction. Now the great speaker, along with the younger Cato and Brutus , Caesar's best-known opponents, were seen as champions of freedom and the republican constitution against despotism. In this sense, his appearance against Catiline was also appreciated. In formal terms, too, he remained the great role model; the leading revolutionaries who wanted to shine as speakers used to shape their speeches according to his model. They valued his ability to use rhetoric to influence politics. Their speeches were teeming with comparisons between current conditions and those of the Cicero era, as well as relevant allusions, assuming knowledge of the classic texts. The Girondist Pierre Vergniaud was called "Cicero".

The English philosopher and economist John Stuart Mill saw Cicero's way of preparing for trials as exemplary. He wrote in “On Liberty” that everyone, like Cicero, must study the opinion of the other, otherwise one cannot form one's own opinion. He also calls him the second best speaker of the ancient world.

The Cicero image developed quite differently in Germany in the 19th century. There the view prevailed in ancient studies as well as in the philosophy of history that the victory of Caesar and the monarchical principle was an inescapable historical necessity and that the republicans' resistance to it was pointless; Caesar did what was timely and therefore right, Cicero could not recognize this and therefore had to fail. A particularly prominent proponent of this view was Hegel . The historian Wilhelm Drumann published a six-volume history of the transition from the republican to the monarchical constitution in Rome from 1834–1844, a standard work, the sixth volume of which is exclusively dedicated to Cicero. In this very thorough but one-sided investigation, he denounced Cicero's vacillations between different party directions and portrayed him as a baseless opportunist. Drumann's point of view was later followed by Theodor Mommsen , who formulated it even more sharply and criticized both the literary and philosophical achievements of Cicero and his politics. He considered him to be “a journalist by nature in the worst sense of the word”, a compiler who, for lack of his own ideas, only reproduced foreign ones superficially, who was rich in words and poor in thoughts. In the third volume of his Roman history , published in 1856, he wrote:

- Marcus Cicero ..., accustomed now to the Democrats, now to Pompey, now from a little further afield, to flirt with the aristocracy and to render advocacy services to every influential defendant regardless of person or party - he also counted Catiline among his clients - actually not from any Party or, what is pretty much the same, the party of material interests ... As a statesman without insight, opinion or intention, he has figured successively as a democrat, as an aristocrat and as an instrument of the monarchs and has never been more than a short-sighted egoist.

Mommsen's judgment of condemnation caused a sensation and had a strong aftereffect. In the early 20th century, his point of view also spread through the influential popular science account of Theodor Birt . It was also well received outside of Germany, but Mommsen's contemporaries such as Gaston Boissier and most of the later historians distanced themselves from it; they classified Mommsen's assessment as one-sided and at most partially justified. The expressionist writer Klabund attested him an "unlimited vanity to which he sacrificed everything, even the truth" and found his speeches "boring to fall asleep". Some scholars, including Tadeusz Stefan Zieliński and Emanuele Ciaceri, sought a general "rehabilitation" of Cicero. The defenders of Cicero insinuated that his modern condemners had transferred the political contradictions of their own epoch to ancient Rome and thus arrived at a partisan perspective.

In the USA, the admiration of the founding father generation for Cicero continued in the 19th and 20th centuries. The city of Cicero in Illinois , founded in 1857, and various localities were named after him. President Harry S. Truman (1945–1953) considered him and Demosthenes to be the two most convincing speakers in world history; he read Cicero's speeches in the original Latin and translated them into English.

In Europe, the Second World War again led to greater interest in Cicero and his humanistic image of man. Friedrich August von Hayek described him in his 1944 book "The Road to Serfdom" as an important representative of individualistic philosophy and Stefan Zweig glorified him in an essay in 1940 as the first advocate of humanity and the last advocate of Roman freedom.

Cicero's works are still part of the core of grammar school Latin lessons today .

In historical novels, Cicero appears frequently, sometimes as the main character. Taylor Caldwell describes his life in the novel A column of ore ( A Pillar of Iron , 1965). He plays an important role in historical crime novels by Steven Saylor . Robert Harris depicts Cicero's life from the perspective of his familiar Tiro in a trilogy of novels .

In 1999 the asteroid (9446) Cicero was named after him.

In 1925 the plant genus Ciceronia Urb. from the sunflower family (Asteraceae) named after him.

Editions and translations

Total expenditure

- M. Tulli Ciceronis opera quae supersunt omnia. Lat. Critical complete edition in individual volumes, various eds. in various editions. BG Teubner, Leipzig and Stuttgart (Bibliotheca Teubneriana).

- Works. Lat.-Engl. Complete edition in individual volumes, various editors in various editions. Loeb, London / Cambridge, Mass. ( Loeb Classical Library ).

Talk

- M. Tulli Ciceronis Orationes, lat. Critical ed. by AC Clark and W. Peterson. 6 vols., Oxford 1905–1918 et al. (Bibliotheca Oxoniensis).

- All speeches. Introduced, trans. and ext. by Manfred Fuhrmann. Artemis, Zurich 1971 ff.

- The political speeches, lat.-dt. Ed., Trans. and ext. by Manfred Fuhrmann. 3 vols. Artemis and Winkler, Munich 1993.

- The speeches against Verres, lat.-dt. Ed., Trans. and ext. by Manfred Fuhrmann. Artemis and Winkler, Munich 1995.

- The litigation speeches, lat.-dt. Ed., Trans. and ext. by Manfred Fuhrmann. 2 vols. Artemis and Winkler, Munich 1997.

- Cicero , Agrarian Speeches . Introduction, Text, Translation, and Commentary by Gesine Manuwald . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2018.

Philosophical writings

- The state (De re publica), Latin - German. Ed. And transl. by Karl Büchner . 4th edition Artemis and Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1987.

- Hortensius , Lucullus, Academici libri, lat.-dt. Ed. And transl. by Laila Straume-Zimmermann, F. Broemser and Olof Gigon . Munich / Zurich: Artemis and Winkler 1990.

- About the goals of human action (De finibus), Latin-German Ed. And transl. by Olof Gigon. Artemis and Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1988.

- Conversations in Tusculum. Tusculanae disputationes. Edited by Olof Gigon. 7th edition, Artemis and Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1998.

- Tusculanae disputationes. Ed .: Max Pohlenz , Bibliotheca Teubneriana, 1918.

- On the essence of the gods (De natura deorum), lat.-dt. Ed. And transl. by W. Gerlach and Karl Bayer. 3rd edition, Artemis and Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1990.

- About fatum (De fato), Latin-German Ed. And transl. by Karl Bayer. 3rd edition, Artemis and Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1980.

- Cato Maior. Laelius, Latin-German Ed. And transl. by M. Faltner. Artemis and Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1988.

- From right action (De officiis), lat.-dt. Ed. And transl. by Karl Büchner. 3rd edition, Artemis and Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1987.

- De Officiis , lat.Edited by M. Winterbottom, Oxford Classical Texts , Oxford 1994

- De finibus bonorum et malorum . Latin edited by LD Reynolds , Oxford Classical Texts , Oxford 1998

Rhetorical writings

- De oratore - About the speaker, lat.-dt. Ed. And transl. by H. Merklin. Reclam, Stuttgart 1978 et al.

- Brutus, Latin-German Ed. And transl. by Bernhard Kytzler. 4th edition, Artemis and Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1990.

- Orator, Latin-German Ed. And transl. by Bernhard Kytzler. 3rd edition, Artemis and Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1988.

- Rhetorica lat.Edited by AS Wilkins, 2nd vol., Oxford Classical Texts , Oxford 1963

Letters

- Epistulae ad familiares, Latin edited and annotated by DR Shackleton Bailey . 2 vols., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1977.

- Epistulae ad familiares. Libri I-XVI, Latin edited by DR Shackleton Bailey. Teubner, Stuttgart 1988.

- To his friends (Ad familiares), Latin-German Ed. And transl. by Helmut Kasten. 4th edition, Artemis and Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1989.

- Letters to Atticus (Ad Atticum), Latin-English. Ed., Trans. and commented by DR Shackleton Bailey. 7 vols., Cambridge 1965-1970.

- Atticus letters (Ad Atticum), lat.-dt. Ed. And transl. by Helmut Kasten. 4th edition, Artemis and Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1990.

- Epistulae ad Quintum fratrem et M. Brutum, Latin ed. And commented by DR Shackleton Bailey. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1980.

- An Brother Quintus, An Brutus (Ad Quintum fratrem, Ad Brutum), Latin-German. Ed. And transl. by Helmut Kasten. Artemis and Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1965.

Anthologies

- Marion Giebel (Ed.): Cicero for pleasure. Reclam, Stuttgart 1997.

- Karl-Wilhelm Weeber (ed.): Cicero for lawyers. Insel, Frankfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 3-458-34242-7

literature

General

- Klaus Bringmann : Cicero. WBG / Primus, Darmstadt 2010, ISBN 978-3-89678-677-7 ; 2nd edition, revised and supplemented by a foreword, Darmstadt 2014.

- Anthony Everitt: Cicero - A turbulent life. Trans. V. Kurt Neff. DuMont, Cologne 2003, ISBN 3-8321-7804-X

- Manfred Fuhrmann : Cicero and the Roman Republic. A biography. Artemis and Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1989; 4th edition 1997, ISBN 3-7608-1919-2 .

- Günter Gawlick , Woldemar Görler : Cicero. In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy . The philosophy of antiquity. Vol. 4: The Hellenistic Philosophy. 2nd half volume, Schwabe, Basel 1994, ISBN 3-7965-0930-4 , pp. 991–1168.

- Matthias Gelzer : Cicero. A biographical attempt. Wiesbaden 1969.

- Marion Giebel: Marcus Tullius Cicero. Rowohlt Taschenbuch, Reinbek 2013, ISBN 978-3-499-50727-4 .

- Woldemar Görler : Investigations into Cicero's philosophy. Winter, Heidelberg 1974.

- Pierre Grimal : Cicero: philosopher, politician, rhetorician. List, Munich 1988.

- Christian Habicht : Cicero the politician. CH Beck, Munich 1990.

- Emanuele Narducci : Cicero. An introduction. Translated from Italian by Achim Wurm, Reclam, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 3-15-018818-0 .

- Francisco Pina Polo : Rome, that's me. Marcus Tullius Cicero. One life . Klett-Cotta Verlag, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-608-94645-1 .

- Wolfgang Schuller : Cicero or The Last Battle for the Republic. A biography , CH Beck, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-65178-6 .

- Otto Seel : Cicero. Word - State - World. 2nd edition, Ernst Klett, Stuttgart 1961.