Antiochus of Ascalon

Antiochus of Askalon ( Greek Ἀντίοχος Antíochos ; * probably between 140 BC and 125 BC in Ascalon ; † probably 68 BC in Mesopotamia ) was an ancient Greek philosopher in the age of Hellenism .

He went to Athens and entered the Platonic Academy , which was then in the final phase of the “Younger Academy”, which was marked by skepticism . In the course of time, however, he came to a determined rejection of skepticism. This led to his leaving the academy and the establishment of his own school. He programmatically named his school "Old Academy". He wanted to express that he was returning to the original Platonism , which he believed had been betrayed by the skeptics of the Younger Academy.

Antiochus was the "house philosopher" of the Roman politician and general Lucullus , whom he accompanied on a trip to North Africa and on a campaign to Armenia . Among his listeners were the famous Romans Varro and Cicero . After the fall of the Younger Academy in the eighties of the 1st century BC. His school was the only heir to the Platonic tradition in Athens, but it only survived his death by around two decades. Despite his emphasis on the Platonic tradition, his ideas were shaped more by the Stoa than by Platonism; in particular, he gave up the Platonic philosophy of transcendence in favor of a materialistic theory of nature.

Life

swell

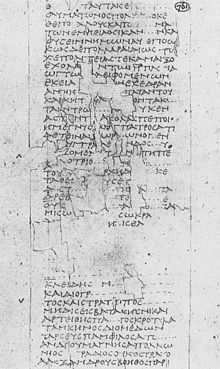

His younger contemporary Philodemos wrote a description of Antiochus' activity in the Academica (Academicorum index) , a fragmentary representation of the history of the Platonic school. Much of the relevant section is lost or difficult to read because of the poor state of preservation of the papyrus . Some biographical information comes from Cicero, who was friends with Antiochus, and from Plutarch .

Youth, apprenticeship and starting your own school

The birth of Antiochus can only be traced back to the period between 140 and 125 BC. Limit Chr. Nothing is known about his family of origin. At an unknown point in time, he left his hometown of Askalon; apparently not before 110/109 he went to Athens, where he joined the Platonic Academy. He became a student of Philo of Larisa , who was the head ( scholar ) of the academy at the time. He also took classes in the Stoa, a philosophy school that rivaled the Academy. The stoic Sosos, who also came from Ascalon, presumably mediated the contact with the Stoa. The stoic teacher of Antiochus in Athens was Mnesarchus , who took over the leadership of the Stoa after the death of the scholar Panaitios , a famous philosopher. It is not known whether Antiochus initially belonged to the Stoa and only later transferred to the Academy, or whether he was an academic from the start and only attended stoic courses on the side.

Antiochus' student relationship with Philo lasted longer than that of any of the other students of the Scholarchen, but at an unknown point in time that was controversial in scholarship, the two philosophers became estranged. The cause was disagreement about skepticism. Ever since the scholarch Arkesilaos introduced skepticism in the academy, "academic skepticism" was the philosophical stance that prevailed there in various forms. The decisive factor in the late 2nd and early 1st century BC Above all, the authority of the famous skeptic Karneades , who served as scholarch of the academy until 137/136. Skepticism was associated with a sharp rejection of stoic ideas.

Under the direction of Philon, who was a scholarch from 110/109 to 88, the academy basically adhered to skepticism, but even among the students of Carnead there was a split between a radically skeptical tendency and representatives of more moderate positions. Philon, who had only entered the Academy after Karneades' health-related resignation, represented a milder version of skepticism.

Even before the mid-nineties, Antiochus tended to renounce the core theses of skepticism, which seemed untenable to him. This brought him into opposition to the prevailing tendency in the academy, which at the time was already moderate and willing to compromise, but was still committed to the tradition of Carnead. After a while this led to his leaving the academy and setting up his own school in Athens. In a programmatic connection to the time before the introduction of skepticism, he called his school "Old Academy". It was not until the Roman Empire that the term “fifth academy” was used for this new foundation, with Philo - historically incorrect - being understood as the founder of a “fourth academy”.

Exile and return

In the year 88 BC BC Philo fled with some of his students and other members of the upper class of Athens because of political turmoil to Rome . In the following year the fighting of the First Mithridatic War began in Greece . Antiochus, who had already found his own way before Philon's flight, did not follow his former teacher to Rome. He probably fled from the reign of terror of the ruling tyrant Aristion in Athens and found refuge in the camp of the Romans who besieged the city. It was there that he probably met Lucullus, a Roman officer subordinate to Sulla, who later became prominent as a politician and general. Lucullus became his friend and patron. Allegedly, the Roman orientated himself in the following period to the philosophical orientation of the Greek, but his preoccupation with philosophical questions probably remained superficial. When Lucullus sailed to Africa via Crete on behalf of Sulla, his new friend stayed in his area. First Lucullus went to Cyrene , where Antiochus, who lived there, was probably useful to him. Perhaps Antiochus helped the Roman commander draft a new constitution for Cyrene. He later followed Lucullus to Alexandria . There he had two local students, but the sources say nothing about the establishment of a formal school in Alexandria.

In 87, in Rome, Philo wrote a text in two books that has not been preserved; it is referred to in research as his "Roman books" because its authentic title is unknown. In it he gave up important principles of skepticism, but did not renounce the claim to continue to be a skeptic in the tradition of Carnead. He stuck to the idea of a unified teaching tradition at the academy since its foundation. When Antiochus received the "Roman Books" in Alexandria in the winter of 87/86, he reacted with indignation and wrote a reply (also lost) by Soso . With that the break was finally completed. Antiochus denied both the suitability of Philon's philosophical approach and the historical correctness of his understanding of the history of philosophy.

Later, probably soon after the end of the military conflict, Antiochus returned to Athens, which was controlled by the Romans from March 86, and resumed teaching there.

Sole heir to the academic tradition

Since the skeptical “Younger Academy” had not survived the chaos of war - apparently no new scholarch was elected after Philon's flight - Antiochus' “Old Academy” was now the only institution that claimed to continue the tradition of Plato's Academy . However, this fact cannot hide the fact that there was no institutional continuity. Antiochus was not, as was claimed in older research literature, Philon's successor as the “Scholarch of the Academy”, but his school was a newly founded school that emphasized its sharp contrast to the skeptical “Younger Academy” from the start. He did not teach on the premises where the Academy had been located since Plato's time, but in the Ptolemaion, a gymnasium located in the city center . The academy site was no longer used for philosophical lessons.

Probably around 83 BC. The famous Roman scholar Varro stayed in Athens and took part in the lessons of Antiochus. In the year 79 a group of prominent Romans was gathered in the "Old Academy": Cicero, who spent six months with Antiochus, his younger brother Quintus Tullius Cicero , his cousin Lucius Tullius Cicero, his friend Titus Pomponius Atticus and the politician Marcus Pupius Piso . Atticus lived in a household with Antiochus. Philodemus of Gadara was also one of Antiochus' friends .

Antiochus' embassy trips to Rome and "to the governors in the provinces", of which Philodemus reports, testify to the reputation of the philosopher at this time when he was at the height of his fame. When his friend and patron Lucullus undertook a campaign to Armenia in the Third Mithridatic War in 69, he accompanied him and was present at the battle of Tigranokerta against the troops of the Armenian King Tigranes II on October 6, 69. As for the course of the fight, Antiochus remarked that the sun had never seen such a battle; Tigranes suffered a catastrophic defeat, with only five men said to have died on the Roman side. Probably the following year Antiochus died in Mesopotamia, where he had accompanied Lucullus.

Works

Antiochus wrote a number of writings, but apart from individual titles and quotations or paraphrases in the works of other authors nothing has survived. When he was still a student of Philo, he wrote treatises in which he - as Cicero reports - defended the skepticism "extremely astute". The time and subject of a work entitled Kanoniká are unknown . The Sōsos dialogue , created around 86 , in which questions of epistemology were discussed, was Antiochus' response to the “Roman books” of Philons. The stoic Sosos, after whom the dialogue is named, apparently appeared as an important participant in the conversation. Around 78 BC BC Antiochus wrote a treatise in which he stated his view, according to which there is agreement between the Stoa and the Peripatos , the school of Aristotle , with regard to the teaching content and the differences can be reduced to questions of formulation. In the last year of his life, he wrote “About the Gods”.

Cicero knows works by Antiochus and takes thoughts from them, which he reproduces in three of his philosophical writings ( De finibus , Lucullus , Academica posteriora ). He does mention Antiochus as the author of the ideas, but in no case gives a specific written source. A number of attempts to assign larger parts of the text in these and other works to Cicero and in writings of other authors to Antiochus, although his name is not mentioned there, remains hypothetical.

A clear presentation of the material in accordance with the needs of the audience was important to Antiochus. His criticism of an artificial philosophical jargon that can only be understood with the help of an interpreter shows that he attached great importance to general understanding.

Teaching

During the long period in which Antiochus was a member of the Philonic school, he firmly advocated skepticism. After his change of opinion, he fought the skeptical philosophy just as fiercely as he had previously defended it. All the traditional details of his teaching relate to the second, antiskeptic phase.

swell

In the philosophical writings of Cicero there are summarizing representations of the teachings of Antiochus, especially in Lucullus (epistemology) and in De finibus (ethics). In addition, there are individual statements from the skeptic Sextus Empiricus , who survives a literally quoted Antiochus fragment. It is unclear to what extent doxographic statements by Sextus on epistemology are based on a lost writing by Antiochus. The church father Augustine also spoke about Antiochus' philosophy. The source value of his remarks is based on the fact that he had the lost work Varros About de Philosophy at his disposal.

Since most of the sources are Latin, some of the terminology has only been handed down in Latin translation from the Greek.

Understanding of philosophy

Antiochus does not consider himself an innovator who presents his own knowledge, but only wants to be a faithful herald of a traditional doctrine to which he professes. Although he does not take over central components of Platonism, he sees himself as a Platonist and refers to the "ancients"; His authorities include the Scholchen of the Older Academy, but also Aristotle. His view of the history of philosophy can be summarized as follows: The authentic Platonism of the Older Academy is fundamentally in line with the teaching of the Stoa and that of Aristotle. All three schools of philosophy originally proclaimed the same truth and just presented it differently. It was only with the skepticism introduced by Arkesilaos that the Academy turned away from this consensus and thus from the truth. In Peripatos, the school of Aristotle, there has also been an undesirable development. The Stoa was best able to keep itself free from falsifications of its original teaching. The Stoa is an attempt to save authentic Platonism from the academic skeptics and to "correct" it in detail. Antiochus regards the attempts at correction as partly successful, partly as unsuccessful; the doctrine of the "ancients" is true for him, but not perfect in every respect, but rather needs improvement in every detail. In the violent conflict between the Stoics and the Skeptics of the Younger Academy over epistemology, the Stoics are in fact the defenders of Platonism against Plato's own apostate school. However, Antiochus raises a plagiarism charge against the Stoics ; he thinks they have "stolen" the ethics of the Older Academy and covered it up by introducing a different, inexpedient terminology.

With his re-establishment of the academy, Antiochus presents himself as the spiritual heir to all three traditions. One of his main demands is the primacy of ethics over the other branches of philosophy. He considers it an essential merit of Socrates to have drawn attention to the way of life as the core area of philosophy, instead of concentrating on natural philosophical speculations like the pre-Socratics and some of the Peripatetics. In second place for Antiochus is dialectic , especially epistemology. He classifies natural philosophy as third; He has to criticize her for the fact that she deals with dark, difficult questions, the clarification of which is far less important than the task of man to lead his life in the right way. However, his ethics are only accessible to those who take into account the natural-philosophical and epistemological background of his worldview.

This conception of the history and tasks of philosophy forms the basis of Antiochus' teaching. Therefore he places particular emphasis on the exposition of his view of the history of philosophy. In doing so, he tries, in keeping with his concept, to make the differences between the philosophical schools whose teachings he considers to be true appear insignificant. A distorted, unhistorical picture of the history of philosophy emerges through the one-sided emphasis on the similarities and the trivialization or concealment of opposites.

Materialistic theory of nature

The stoic background of Antiochus is very clearly noticeable in the theory of nature. He assumes two primordial principles of the whole of reality, an effecting force and the matter that presents itself to the force and is shaped by it. Effectiveness and matter belong together by nature, each of the two is contained in the other. Without matter there can be no effective force, and matter needs the force by which it is held together. Since the effective force outside of matter is inconceivable, nothing exists apart from the two principles and everything that is is necessarily spatial, there is no being independent of physical existence for Antiochus. This contradicts Plato's theory of ideas , who accepted ideas as independent, transcendent archetypes of sense objects. Thus Antiochus gave up the theory of ideas, at least in its original version. However, some historians of philosophy, among them Paul Oskar Kristeller , attribute his own theory of ideas to him. They trace back the interpretation of the ideas as the thoughts of God, attested to in later Platonism, to Antiochus and refer to statements made by his students Varro and Cicero, which they regard as evidence of their hypothesis. Other researchers reject this on the grounds that it would contradict the materialistic worldview of Antiochus and that there is no reliable evidence.

Antiochus also calls the power (Latin vis or res efficiens ) property (Greek poiótēs , Latin qualitas ) according to Stoic terminology . Theoretically, the primordial matter has no properties, is completely unformed and therefore suitable for taking any shape. But since power and matter cannot exist independently of one another, the unqualified primordial matter does not really exist; the two original principles can only be separated in the act of thought, not in reality. Matter receives its diverse, constantly changing forms from the force of action. In accordance with the Stoa, Antiochus considers matter to be infinitely divisible, thus contradicting the opinion of the atomists and Epicureans . He also regards the soul as material.

The power that is immanent in the cosmos, holds it together and makes it a unity, is to be equated with the divinity and the world soul . It is the authority that governs the world according to reason. All processes in heaven and on earth are determined and linked by her fatefully and inexorably. At the same time, she plays the role of Divine Providence in human life .

Because of the indissolubility of the connection between active force and matter and because the existence of matter determines that of the active force, this worldview can be described as materialistic . It is primarily stoic. However, in the source that reports on it, Ciceros Academica posteriora , it is not expressly stated that Antiochus embraced the stoic views that he expounded in his explanations on the history of philosophy. However, it can be inferred that he largely approves of them.

Epistemology

In his epistemology, too, Antiochus emphatically agrees with the stoic view. He attacks the position of the skeptics, according to which all statements - especially all philosophical teachings - are only opinions, the correctness of which can at best be made plausible, but never conclusively proven. He is convinced that there is a “knowledge- conveying idea” (katalēptikḗ phantasía) , which enables secure knowledge; there is no doubt about the correctness of the insight into reality gained in this way. The knowledge-conveying idea - a technical term of the Stoa - is characterized by the fact that its correctness is beyond doubt because no wrong idea is conceivable that could produce the same impression as the correct one. In contrast to the skeptics, Antiochus considers this condition to be achievable. For him as for the Stoics it is the criterion of truth. In his dispute with Philo, he mainly opposes his rejection of the Stoic truth criterion, as he sees this criterion as an indispensable prerequisite for a meaningful distinction between true and false. According to his epistemology, there is knowledge whose absolute reliability follows from the fact that the possibility of an error can be logically excluded. Only then can one speak of knowledge at all. Philo's opposing position is that one can admit the logical possibility of an error without necessarily having to give up the claim to knowledge in each individual case.

Against the assertion of the skeptics that nothing can be known with certainty, Antiochus raises the objection that such a doubt of principle cannot - as Arkesilaos and Karneades had asserted - also apply to itself. Rather, the skeptics are forced, inconsistently, to make a claim to truth for their own principle. In addition, there is a contradiction in the fact that the skeptics on the one hand assume the actual existence of objectively true or false ideas and on the other hand deny that it is possible to differentiate between true and false. Furthermore, Antiochus repeats the well-known accusation of opponents of skepticism that the skeptical attitude cannot be implemented in everyday life, since it leaves the skeptical philosopher no criterion according to which he can make sensible decisions and thus condemns him to inaction. Another argument relies on the empirical success that can be achieved if one acts on the basis of a correct, knowledge-conveying idea; this success presupposes a connection between the imagination and the reality, which is not given with a deceptive imagination.

Antiochus differentiates between the sensually perceptible, which is subject to constant change, and the unchangeable, which is the only legitimate object of truth assertions. According to his teaching, the sense data, since they only concern something changeable, cannot of themselves provide access to the truth, but only generate opinions; The knowledge of truth is an achievement of the understanding in dealing with the concepts that have the quality of the permanent and persistent. This distinction is reminiscent of Plato's separation between the world of appearances and the world of ideas. But it is not meant in this sense, for Antiochus does not assign the unchangeable to an ontologically independent existence. For him the constant does not exist in a separate intelligible world, but only in the form of general concepts and the conclusions drawn from them, insofar as these are present in the mind. What is universally valid is derived from the understanding exclusively from the sensory impressions - otherwise it cannot be inferred - and has a meaning only through its connection with them. The understanding, which evaluates and organizes the impressions conveyed by the sense organs, is itself a sense in Antiochus' materialistic worldview.

This unplatonic doctrine of Antiochus greatly enhances sensory perception compared to Platonism. Plato distrusted the senses, since their objects were only inadequate copies of archetypes (ideas), and assumed an independent world of ideas to which one could and should turn directly. A Platonic element and a difference to the Stoa, however, is that Antiochus only allows the term “true” for general terms, while the Stoics also use it for individual sensory perceptions.

ethics

For Antiochus the highest good of man and thus the goal (télos) of life is to "live according to nature". He relates the ideal of the natural to specifically human nature in its perfection when it has reached a state in which it lacks nothing. That the natural is the norm was already taught in the Older Academy. As Antiochus found historically correct, this concept was common to the Platonists and the Stoics, because the Stoa adopted it from the Academy. However, the concept of nature underwent a change in meaning in the Stoa; The role of the model was increasingly taken over by all-nature, the general nature of the cosmos, which thus took the place of a specifically human nature. Thus human nature was only important insofar as it was an expression of world nature. For the Stoics, the value of human nature consisted in the fact that human reason was viewed as the manifestation of the divine world reason which directed the cosmos from within. Therefore, in the Stoic order of values, only spiritual goods, the virtues that enable a rational life, were assigned their own value.

On this point Antiochus contradicts the Stoa. For him, nature, which is supposed to be a model for man, cannot be all-nature, but only the human species-nature in its particularity. In doing so, he aims to include the human body. He accuses the Stoics of having in reality distanced themselves from nature by disregarding physical goods (such as health, strength and beauty). Since man consists of body and soul, one cannot simply give up the body. Rather, human nature is to be brought to perfection in every respect, including on the physical level. Therefore, one shouldn't deny physical goods any intrinsic value. In the realm of the physical, too, there is something natural that is worth striving for for its own sake and even contributes to the attainment of the highest goal, the perfectly natural life. Moreover, external goods such as friends, relatives and the fatherland, even wealth, honor and power are also valuable and desirable in themselves. However, in contrast to the spiritual and physical, external goods are not absolutely necessary for a perfect life according to human nature. It is true that spiritual goods, namely the virtues , deserve a principled priority, and that a virtuous character alone suffices to achieve eudaimonia (happiness). The early academics and the Peripatetics (with the exception of Theophrastus ) would have rightly taught this. As a result, however, the equally legitimate pursuit of physical and external goods is not devalued and made superfluous. (Characteristic) virtue is not the only good in man; Antiochus even speaks of physical "virtues" in the sense of desirable states of completion of the body. He does not only mean that the individual organs are healthy and perform their tasks without interference, but he also counts properties such as natural posture and graceful gait as physical virtues. As virtues (Latin virtutes ) he not only describes positive character traits, but also generally desired, natural properties.

Antiochus emphasizes that the development of the individual, which leads to the perfection of his human nature, takes place gradually, with the later building on the earlier. The course of a human life leads from the initial instinctive, "dark" striving for self-preservation, which is common to all living beings, to the perception and use of one's own abilities and talents, a development stage intended for humans and animals, but not for plants. Ultimately - in the best case - progress leads to self-knowledge with regard to the specifically human, the realization of which is required by human nature. The possibility of such a reflection on what is natural is like a seed put into man by nature. It is then up to him to realize this system.

The stages of development are ordered hierarchically according to the teaching of Antiochus . The advancement is not a replacement of the lower by the higher, but an addition of the higher to the lower. As a rule, man strives for what is natural and therefore valuable. If errors and ethical conflicts arise in the process, this is due to the fact that the hierarchical order of goods is not observed, but a lower value is preferred to a higher one.

With regard to the spiritual and spiritual virtues, Antiochus distinguishes between those that are bestowed by nature as gifts and "arise of their own accord", such as quick apprehension and memory, and "voluntary" ones that are due to the activity of reason. The voluntary virtues - the cardinal virtues of wisdom, temperance, bravery, and justice - are acquired after choosing them. Their acquisition is always in the power of the individual. Only they are necessary for attaining bliss, and they are also sufficient prerequisites for it. Therefore, a happy life is always possible through your own decision; physical and external obstacles and evils cannot prevent it. Antiochus does not share the radical view of those who deny that physical and external goods have any influence on the happiness of a wise man. Although he thinks that the cardinal virtues are sufficient for a happy life, he sees additional reinforcing factors in the physical and external goods that can increase happiness even more. This enables a perfectly happy life (Latin vita beatissima ), while the spiritual and spiritual virtues alone can only guarantee a happy life (vita beata) .

Antiochus also opposes one-sidedness with regard to the question of the best way of life. Neither the active, outwardly successful life of non-philosophers (Greek bíos Practikós , Latin vita activa ) nor the contemplative, withdrawn life of some philosophers ( bíos theōrētikós , vita contemplativa ) is ideal , but a combination of both forms of life.

reception

Antiquity

After Antiochus' death, his brother and pupil Aristus took over the management of the school. Apparently he hardly deviated from the teaching of Antiochus. With his death, Antiochus' "Old Academy" seems to have perished as an institution; In any case, nothing is known of any other little scholars.

The aftermath of Antiochus' philosophy in antiquity was based primarily on his considerable influence on his two very prominent Roman students, Cicero and Varro. Indirectly, he also influenced the republican-minded politician Marcus Iunius Brutus , who played an important role in the assassination of Caesar and in the subsequent civil war. Brutus was a student and friend of Aristus and an admirer of Antiochus, whom he did not know personally. He wrote several philosophical works. In his now-lost treatise On Virtue , he closely followed the ethics of Antiochus.

Cicero does not agree with Antiochus' criticism of skepticism, but paints a very positive picture of his personality. He praised his extraordinary talent and education, his cleverness, his gentle, peaceful character and the persuasive power of his appearance. His nickname “the swan” (kýknos) , handed down by the late ancient scholar Stephanos of Byzantium , probably referred to the philosopher's rhetorical skills .

Opponents of Antiochus assumed that his motive for breaking with academic skepticism and founding his own school was a lust for fame. Cicero and Plutarch mention such accusations.

On the other hand, judgments in the Roman Empire were unfavorable . Plutarch only indicated his disapproval indirectly. The Middle Platonist Numenios disliked Antiochus' proximity to the Stoa; he rebuked the introduction of numerous "foreign" elements (incompatible with Platonism). The skeptic Sextus Empiricus, a representative of the radical “ Pyrrhonic ” skepticism, thought Antiochus was a stoic who brought stoic philosophy to the academy and taught it there. The Church Father Augustine was particularly harsh when he pointed out the rumors that Antiochus was more motivated by a lust for glory than a love of truth. He was a "straw Platonist" who had achieved nothing essential and contaminated Platonism with stoic evil. The materialistic aspect of Antiochus' teaching could only meet with the sharpest contradiction in Christian circles.

Modern

In the modern age, many scholars emphasize the unplatonic aspects of the teaching of Antiochus. An interpretation put forward by Willy Theiler , according to which he was a true Platonist and as such prepared the Middle and Neoplatonism , has not prevailed.

The judgments in modern research are sometimes devastating, especially in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Eclecticism , the mixing of different philosophical traditions, which occurred without understanding the peculiarities of the sometimes incompatible doctrines, caused offense . In this sense, for example, Theodor Mommsen expressed himself , who thought that Antiochus had “jumbled together” Stoic ideas with Platonic-Aristotelian ones; this has become the “fashion philosophy of the conservatives of his time”, a “malformed doctrine”. Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff judged that Antiochus had “trimmed down a doctrine that met the needs and feelings of the so-called educated, because it avoided all sharp dialectics and seemed to retain all that is good and beautiful.” Eduard Zeller also shared this assessment .

Sharp criticism has also occurred in recent times; Michelangelo Giusta considers Antiochus to be greatly overrated. Since the late 20th century, however, more positive assessments have predominated. Jonathan Barnes thinks Antiochus' return to the past is understandable, since she turned the attention to the achievements of important predecessors at a time when the philosophy schools were in decline. Woldemar Görler also came to a relatively favorable assessment . In his view, Antiochus' philosophy is "not a vague compromise" but "self-contained". The founder of the “Old Academy” had not reinterpreted Plato's teaching in the stoic sense out of dishonesty and blurred the serious differences between the schools, but because metaphysical thinking was alien to him ; its syncretism is an expression of a tendency in the zeitgeist of the time. Regardless of his position as head of a “platonic” school, he has in fact become almost a pure stoic. Also John Dillon holds Antiochus thinking for coherent. According to Mauro Bonazzi, Antiochus was by no means a platonically disguised Stoic. Rather, he cleverly pursued his strategy: He did not want to merge Platonism and Stoa, but rather subordinate the Stoic teachings to Platonism and integrate them into it.

Source collections

- Heinrich Dörrie (Ed.): The Platonism in antiquity , Volume 1: The historical roots of Platonism . Frommann-Holzboog, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1987, ISBN 3-7728-1153-1 , pp. 188–211, 449–483 (source texts with translation and commentary)

- Hans Joachim Mette : Philon of Larisa and Antiochus of Askalon . In: Lustrum 28/29, 1986/87, pp. 9–63 (compilation of the source texts)

literature

- Jonathan Barnes : Antiochus of Ascalon . In: Miriam Griffin , Jonathan Barnes (eds.): Philosophia togata. Essays on Philosophy and Roman Society. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1989, ISBN 0-19-814884-4 , pp. 51-96

- John Dillon : The Middle Platonists . Duckworth, London 1977, ISBN 0-7156-1091-0 , pp. 52-106

- Ludwig Fladerer: Antiochus of Askalon. Hellenist and humanist (= Grazer Contributions , Supplement 7). Berger and Sons, Graz / Horn 1996 (cf. the very critical review by John Glucker in Gnomon 74, 2002, pp. 289–295)

- John Glucker: Antiochus and the Late Academy (= Hypomnemata Vol. 56). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1978, ISBN 3-525-25151-3

- Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy . The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4: The Hellenistic Philosophy , 2nd half volume, Schwabe, Basel 1994, ISBN 3-7965-0930-4 , pp. 938–980

- David Sedley (Ed.): The Philosophy of Antiochus . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2012, ISBN 978-0-521-19854-7

Web links

- Entry in Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

Remarks

- ↑ A compilation of the material is provided by David Sedley (ed.): The Philosophy of Antiochus , Cambridge 2012, pp. 334–346.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 939. Cf. Myrto Hatzimichali: Antiochus' biography. In: David Sedley (ed.): The Philosophy of Antiochus , Cambridge 2012, pp. 9–30, here: 10 f.

- ^ Kilian Fleischer: The stoic Mnesarch as teacher of Antiochus in the Index Academicorum. In: Mnemosyne 68, 2015, pp. 413-423; Jonathan Barnes: Antiochus of Ascalon . In: Miriam Griffin, Jonathan Barnes (eds.): Philosophia togata , Oxford 1989, pp. 51–96, here: 53 f .; Jean-Louis Ferrary: Philhellénisme et impérialisme , Rome 1988, p. 451. There is no source evidence for the assumption that Antiochus also studied with the stoic Dardanos; see Jonathan Barnes: Antiochus of Ascalon . In: Miriam Griffin, Jonathan Barnes (ed.): Philosophia togata , Oxford 1989, pp. 51–96, here: 54.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 939.

- ↑ See Myrto Hatzimichali: Antiochus' biography. In: David Sedley (ed.): The Philosophy of Antiochus , Cambridge 2012, pp. 9–30, here: 11–16.

- ↑ See Anthony A. Long : Hellenistic philosophy , 2nd edition, London 1986, pp. 88-106.

- ↑ Woldemar Görler: Older Pyrrhonism. Younger academy. Antiochus from Ascalon. In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 717–989, here: 903 f., 920 f.

- ↑ For the dating see Myrto Hatzimichali: Antiochus' biography. In: David Sedley (ed.): The Philosophy of Antiochus , Cambridge 2012, pp. 9–30, here: 14; Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 941 f .; Jean-Louis Ferrary: Philhellénisme et impérialisme , Rome 1988, p. 447, note 43; John Glucker: Antiochus and the Late Academy , Göttingen 1978, pp. 15-20; Charles Brittain: Philo of Larissa. The Last of the Academic Skeptics , Oxford 2001, pp. 55 f. For the background and presumed course of the development that led to the change of position, see Harold Tarrant: Scepticism or Platonism? , Cambridge 1985, pp. 90-94; John Dillon: The Middle Platonists , London 1977, p. 53.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: The younger academy in general. In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 775–785, here: 779–781.

- ↑ For various hypotheses about the circumstances of the encounter, see Myrto Hatzimichali: Antiochus' biography. In: David Sedley (ed.): The Philosophy of Antiochus , Cambridge 2012, pp. 9–30, here: 16 f. Cf. Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 942 f.

- ↑ John Glucker: Antiochus and the Late Academy , Göttingen 1978, pp. 21-27, 91-94, 380-385; Myrto Hatzimichali: Antiochus' biography. In: David Sedley (ed.): The Philosophy of Antiochus , Cambridge 2012, pp. 9–30, here: 18–20.

- ↑ Jules van Ooteghem: Lucius Licinius Lucullus , Bruxelles 1959, p. 25; Carlos Lévy: Cicero Academicus , Rome 1992, p. 89.

- ↑ Jonathan Barnes: Antiochus of Ascalon . In: Miriam Griffin, Jonathan Barnes (eds.): Philosophia togata , Oxford 1989, pp. 51–96, here: 57; John Glucker: Antiochus and the Late Academy , Göttingen 1978, pp. 92-97.

- ↑ Jonathan Barnes: Antiochus of Ascalon . In: Miriam Griffin, Jonathan Barnes (eds.): Philosophia togata , Oxford 1989, pp. 51–96, here: 74 f.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 943.

- ↑ Hypotheses about possible successors of Philo are not plausible, see Woldemar Görler: Philon from Larisa . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 915-937, here: 917 and Jean-Louis Ferrary: Philhellénisme et impérialisme , Rome 1988, p. 447 f. Enzo Puglia disagrees: Le biography di Filone e di Antioco nella Storia dell'Academia di Filodemo . In: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 130, 2000, pp. 17–28, here: 24 ( online ; PDF; 139 kB); Puglia is expecting a successor to Philo who is not known by name. However, since Cicero does not mention it, this may have acquired no significance and may not have held office for long. Compare with Tiziano Dorandi (Ed.): Filodemo: Storia dei filosofi. Platone e l'Academia (PHerc. 1021 e 164) , Napoli 1991, p. 80 f.

- ↑ John Patrick Lynch: Aristotle's School , Berkeley 1972, pp. 179-183; Carlos Lévy: Cicero Academicus , Rome 1992, p. 53; John Glucker: Antiochus and the Late Academy , Göttingen 1978, pp. 98-111.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 943 f.

- ^ Kilian J. Fleischer: Dionysius of Alexandria, De natura (περὶ φύσεως). Translation, commentary and appreciation , Turnhout 2016, pp. 90 f., 100–102.

- ↑ Philodemos, Academica col. 34, text by Hans Joachim Mette: Philon from Larisa and Antiochus from Askalon . In: Lustrum 28/29, 1986/87, pp. 9–63, here: 30. Cf. Myrto Hatzimichali: Antiochus' biography. In: David Sedley (ed.): The Philosophy of Antiochus , Cambridge 2012, pp. 9–30, here: 26 f.

- ↑ Plutarch, Lucullus 28: 8.

- ↑ On the dating of Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 944.

- ↑ Philodemos, Academica col. 34. For a reading of this papyrus fragment, see David Blank: The Life of Antiochus of Ascalon in Philodemus' History of the Academy and a Tale of Two Letters . In: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 162, 2007, pp. 87–93, here: 89–92.

- ^ Cicero, Lucullus 69. See Myrto Hatzimichali: Antiochus' biography. In: David Sedley (ed.): The Philosophy of Antiochus , Cambridge 2012, pp. 9–30, here: 11 f.

- ↑ Myrto Hatzimichali: Antiochus' biography. In: David Sedley (Ed.): The Philosophy of Antiochus , Cambridge 2012, pp. 9–30, here: 29.

- ↑ Cicero, De natura deorum 1.16. See Myrto Hatzimichali: Antiochus' biography. In: David Sedley (Ed.): The Philosophy of Antiochus , Cambridge 2012, pp. 9–30, here: 29.

- ↑ For possible content see Jonathan Barnes: Antiochus of Ascalon . In: Miriam Griffin, Jonathan Barnes (eds.): Philosophia togata , Oxford 1989, pp. 51–96, here: p. 63 note 50.

- ↑ See also Hans Joachim Mette: Philon von Larisa and Antiochus von Askalon . In: Lustrum 28/29, 1986/87, pp. 9–63, here: 27–29.

- ^ Cicero, De finibus 5, 89.

- ↑ Cicero, Lucullus 69.

- ^ Sextus Empiricus, Against the Mathematicians 7,201.

- ↑ David Sedley offers a hypothesis: Sextus Empiricus and the Atomist Criteria of Truth . In: Elenchos 13, 1992, pp. 19-56, here: 44-55.

- ↑ See also David Blank: Varro and Antiochus. In: David Sedley (ed.): The Philosophy of Antiochus , Cambridge 2012, pp. 250–289, here: 253–257.

- ↑ Pierluigi Donini: Testi e commenti, manuali e insegnamento: la forma sistematica ei metodi della filosofia in età postellenistica . In: Rise and Decline of the Roman World , Vol. II.36.7, Berlin 1994, pp. 5027-5100, here: pp. 5028 f. and note 3.

- ↑ On Antiochus' understanding of the history of philosophy see Woldemar Görler: Antiochus von Askalon about the 'ancients' and about the Stoa . In: Peter Steinmetz (Ed.): Contributions to Hellenistic literature and its reception in Rome , Stuttgart 1990, pp. 123-139; George E. Karamanolis: Plato and Aristotle in Agreement? , Oxford 2006, pp. 51-64.

- ^ Cicero, De finibus 5.74; 5.89; 5.91.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 949.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 947–951.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Antiochus of Askalon on the 'ancients' and on the Stoa . In: Peter Steinmetz (Ed.): Contributions to Hellenistic literature and its reception in Rome , Stuttgart 1990, pp. 123–139, here: 129–133; Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 950, 953 f., 966; Carlos Lévy: Cicero Academicus , Rome 1992, pp. 553-555; Heinrich Dörrie (Ed.): The Platonism in the Ancient World , Vol. 1, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1987, pp. 472-483; John Dillon: The Middle Platonists , London 1977, pp. 83 f.

- ↑ Paul Oskar Kristeller: The ideas as thoughts of human and divine reason , Heidelberg 1989, pp. 14-17.

- ↑ A research overview is offered by Woldemar Görler: Antiochos from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 951 f., 977 f .; see. Heinrich Dörrie (Ed.): The Platonism in antiquity , vol. 1, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1987, pp. 477-483. The hypothesis of a theory of ideas by Antiochus, among others, by Jonathan Barnes: Antiochus of Ascalon is rejected . In: Miriam Griffin, Jonathan Barnes (ed.): Philosophia togata , Oxford 1989, pp. 51–96, here: 95 f., It is advocated by Ludwig Fladerer, among others: Antiochos von Askalon, Hellenist and Humanist , Graz / Horn 1996 , Pp. 101–129 (cf. the review by John Glucker in: Gnomon 74, 2002, pp. 289–295).

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 950 f.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 951.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 948–951; Alexandra Michalewski: La puissance de l'intelligible , Leuven 2014, pp. 22-25.

- ↑ John Dillon: The Middle Platonists , London 1977, pp. 63-69; Charles Brittain: Philo of Larissa. The Last of the Academic Skeptics , Oxford 2001, pp. 153 f .; Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 952 f.

- ↑ Lloyd P. Gerson: From Plato to Platonism , Ithaca / London 2013, p. 182 f.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 952 f .; Gisela Striker : Academics fighting Academics . In: Brad Inwood , Jaap Mansfeld (ed.): Assent and argument , Leiden 1997, pp. 257-276, here: 261 f.

- ^ Robert James Hankinson: Natural Criteria and the Transparency of Judgment . In: Brad Inwood, Jaap Mansfeld (ed.): Assent and argument , Leiden 1997, pp. 161-216, here: 193-195.

- ^ John Dillon: The Middle Platonists , London 1977, p. 67 f .; Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938-980, here: 953 f.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 953–955.

- ↑ Cicero, De finibus 5: 24-26.

- ↑ Woldemar Görler: Aristos and his students . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , vol. 4: The Hellenistic philosophy , 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 967–969, here: 955–958.

- ↑ François Prost emphasizes the contrast between the position of Antiochus and the stoic position in ethics: L'éthique d'Antiochus d'Ascalon . In: Philologus 145, 2001, pp. 244-268; Woldemar Görler points to similarities despite Antiochus' demarcation from Stoic ethics; see Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 956–958.

- ↑ See also Woldemar Görler: Antiochos from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 956.

- ↑ Cicero, De finibus 5.34-38.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 958–960. Cf. Christopher Gill: Antiochus' theory of oikeiōsis. In: Julia Annas , Gábor Betegh (ed.): Cicero's De Finibus. Philosophical Approaches , Cambridge 2016, pp. 221–247, here: 222–229.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 960.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 962–964.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 964.

- ↑ Woldemar Görler: Aristos and his students . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , vol. 4: The Hellenistic philosophy , 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 967–969, here: 968 f.

- ^ Carlos Lévy: Other followers of Antiochus. In: David Sedley (ed.): The Philosophy of Antiochus , Cambridge 2012, pp. 290–306, here: 300–303; Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938-980, here: 967, 969 f.

- ↑ Jonathan Barnes: Antiochus of Ascalon . In: Miriam Griffin, Jonathan Barnes (eds.): Philosophia togata , Oxford 1989, pp. 51–96, here: 51 f.

- ↑ Cicero, Lucullus 70; Plutarch, Cicero 4.2. See Annemarie Lueder: The philosophical personality of Antiochus of Askalon , Göttingen 1940, p. 19.

- ↑ Plutarch, Cicero 4, 1–2. See Jeffrey Tatum: Plutarch on Antiochus of Ascalon: Cicero 4,2 . In: Hermes 129, 2001, pp. 139-142; Jan Opsomer: Plutarch's Platonism Revisited . In: Mauro Bonazzi, Vincenza Celluprica (ed.): L'eredità platonica. Studi sul platonismo da Arcesilao a Proclo , Napoli 2005, pp. 161-200, here: pp. 169 f. and note 18.

- ↑ Numenios, Fragment 28 Des Places ; see Heinrich Dörrie (ed.): Der Platonismus in der Antike , Vol. 1, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1987, pp. 202 f., 465 f.

- ^ Sextus Empiricus: Fundamentals of Pyrrhonism 1,235.

- ↑ Augustinus, Contra Academicos 2, 6, 15; 3.18.41.

- ^ Willy Theiler: The preparation of Neo-Platonism , 2nd edition, Berlin 1964, pp. 37–55; see. Georg Luck : The Academician Antiochus , Bern 1953, pp. 23–30. For a criticism of Theiler's hypothesis, see Woldemar Görler: Antiochos from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 966 and the literature cited there.

- ^ Theodor Mommsen: Römische Geschichte , Vol. 3, 9th edition, Berlin 1904, p. 571.

- ^ Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff u. a .: Greek and Latin literature and language , 3rd edition, Leipzig and Berlin 1912, p. 144.

- ^ Eduard Zeller: The philosophy of the Greeks in their historical development , 3rd part, 1st section, 5th edition, Leipzig 1923, pp. 626, 628.

- ^ Michelangelo Giusta: Antioco di Ascalona e Carneade nel libro V del De finibus bonorum et malorum di Cicerone . In: Elenchos 11, 1990, pp. 29-49, here: 29.

- ↑ Jonathan Barnes: Antiochus of Ascalon . In: Miriam Griffin, Jonathan Barnes (ed.): Philosophia togata , Oxford 1989, pp. 51–96, here: 79–81, 90.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Antiochus from Askalon and his school . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 938–980, here: 966 f.

- ^ John Dillon: The Middle Platonists , London 1977, pp. XIV f.

- ^ Mauro Bonazzi: Antiochus' Ethics and the Subordination of Stoicism. In: Mauro Bonazzi, Jan Opsomer (ed.): The Origins of the Platonic System , Louvain 2009, pp. 33–54, here: 43 f., 49–53.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Antiochus of Ascalon |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | ancient Greek philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | between 140 BC BC and 125 BC Chr. |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Ascalon |

| DATE OF DEATH | uncertain: 68 BC Chr. |

| Place of death | Mesopotamia |