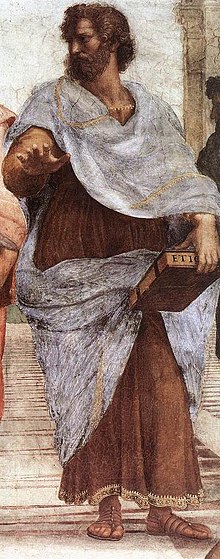

Aristotle

Aristotle ( Greek Ἀριστοτέλης Aristotélēs , emphasis Latin and German: Aristóteles; * 384 BC in Stageira ; † 322 BC in Chalkis on Evia ) was a Greek polymath . He is one of the most famous and influential philosophers and naturalists in history. His teacher was Plato , but Aristotle either founded or significantly influenced numerous disciplines, including philosophy of science , natural philosophy , logic , biology , physics , ethics , state theory and poetry . Aristotelianism developed from his ideas .

overview

Life

Aristotle, who came from a family of doctors, came to Athens when he was seventeen . In 367 BC He entered Plato's academy . There he participated in research and teaching. After Plato's death he left Athens in 347. In 343/342 he became the teacher of Alexander the Great , heir to the throne in the Kingdom of Macedonia . In 335/334 he returned to Athens. He no longer belonged to the academy, but taught and researched independently with his students at the Lykeion . 323/322 he had to leave Athens again because of political tension and went to Chalkis, where he died soon afterwards.

plant

Aristotle's writings in dialogue form , aimed at the general public, are lost. Most of the textbooks that have survived were only intended for internal use in the classroom and were continuously edited. Subject areas are:

Logic, philosophy of science, rhetoric: In the logical writings, Aristotle works out a theory of argument (dialectic) based on discussion practices in the academy and establishes formal logic with the syllogistics . On the basis of his syllogistics, he develops a theory of science and, among other things, makes significant contributions to definition theory and meaning theory . He describes rhetoric as the art of proving statements to be plausible, thus bringing them close to logic.

Doctrine of Nature: Aristotle's philosophy of nature deals with the fundamentals of every view of nature: the types and principles of change. The then topical question of how arising and disappearing is possible, he addresses with the help of his well-known distinction between form and matter : The same matter can take on different forms. In his scientific works he also examines the parts and behavior of animals as well as humans and their functions. In his theory of the soul - in which "to be animated" means "to be alive" - he argues that the soul, which makes up the various vital functions of living beings, belongs to the body as its form. But he also conducts empirical research and makes significant contributions to zoological biology.

Metaphysics: In his Metaphysics Aristotle argues (against Plato's assumption of abstract entities) first of all that the concrete individual things (like Socrates) the substances, i.e. H. are the fundamentals of all reality. He supplements this with his later doctrine, according to which the substance of concrete individual things is their form.

Ethics and political theory: The goal of human life, according to Aristotle in his ethics , is the good life, happiness. For a happy life, one has to develop intellectual virtues and (through education and habituation) character virtues, including dealing with desires and emotions accordingly . His political philosophy is linked to ethics. Accordingly, the state as a form of community is a prerequisite for human happiness. Aristotle asks about the conditions of happiness and for this purpose compares different constitutions. The theory of the forms of government that he developed enjoyed undisputed authority for many centuries.

Theory of poetry: In his theory of poetry, Aristotle deals in particular with tragedy , whose function, in his view, is to arouse fear and compassion in order to purify the viewer from these emotions (catharsis).

Aftermath

The scientific research program of Aristotle was continued after his death by his colleague Theophrastus , who also founded the Aristotelian school, the Peripatos , in the legal sense. The Aristotle commentary did not begin until the 1st century BC. A and was operated in particular by Platonists. Through the mediation of Porphyrios and Boethius , Aristotelian logic became groundbreaking for the Latin-speaking Middle Ages. Since 12./13. In the 19th century, all of Aristotle's basic works were available in Latin translation. They were decisive for scholastic science up until the early modern period . The examination of the Aristotelian theory of nature shaped the natural science of the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. In the Arabic-speaking world, Aristotle was the most intensely received ancient author in the Middle Ages. His work has shaped intellectual history in many ways; important distinctions and terms such as “substance”, “accident”, “matter”, “form”, “energy”, “potency”, “category”, “theory” and “practice” go back to Aristotle.

Life

Aristotle was born in 384 BC. In Stageira , then an independent Ionian town on the east coast of the Chalkidike . Therefore he is sometimes called "the stagirit". His father Nicomachus was the personal physician of King Amyntas III. from Macedonia , his mother Phaestis came from a family of doctors from Chalkis on Euboia. Nicomachus died before Aristotle came of age. Proxenus from Atarneus was appointed guardian.

First stay in Athens

367 BC Aristotle came to Athens at the age of seventeen and entered Plato's academy . There he initially dealt with the mathematical and dialectical topics that formed the beginning of the studies in the academy. He began to write works early on, including dialogues modeled on those of Plato. He also dealt with contemporary rhetoric , in particular with the lessons of the speaker Isocrates . Against the pedagogical concept of Isocrates aimed at direct benefit, he defended the Platonic educational ideal of the philosophical training of thought. He took up a teaching position at the academy. In this context, the oldest of his traditional textbooks emerged as lecture manuscripts, including the logical writings, which were later summarized under the name Organon ("tool"). A few passages indicate that the lecture hall was decorated with paintings depicting scenes from the life of Plato's teacher Socrates .

Travel years

After Plato's death, Aristotle left in 347 BC. BC Athens. Perhaps he did not agree that Plato's nephew Speusippus should take over the management of the academy; besides, he had got into political trouble. In 348 BC King Philip II of Macedonia had conquered Chalkidike, destroyed Olynthos and also took Aristotle's hometown Stageira. This campaign was recognized by the anti-Macedonian party in Athens as a serious threat to the independence of Athens. Because of the traditional ties between the Aristotle family and the Macedonian court, the anti-Macedonian mood was also directed against him. Since he was not an Athenian citizen, but only a meticulist of dubious loyalty, his position in the city was relatively weak.

He accepted an invitation from Hermias , who ruled the cities of Assos and Atarneus on the coast of Asia Minor opposite the island of Lesbos . To secure his sphere of influence against the Persians, Hermias was allied with Macedonia. Other philosophers also found refuge in Assos. The very controversial Hermias is described by his friendly tradition as a wise and heroic philosopher, but by the opposing tradition as a tyrant. Aristotle, who was friends with Hermias, initially stayed in Assos; 345/344 BC He moved to Mytilene on Lesbos. There he worked with his student Theophrastus from Lesbos, who shared his interest in biology. Later both went to Stageira.

343/342 BC At the invitation of Philip II, Aristotle went to Mieza to teach his then thirteen-year-old son Alexander (later called "the great"). The instruction ended no later than 340/339 BC. When Alexander took over the reign for his absent father. Aristotle had a copy of the Iliad made for Alexander , which the king, as an admirer of Achilles, later carried with him on his campaigns of conquest. The relationship between teacher and student has not been passed down in detail; it has given rise to legends and all kinds of speculations. What is certain is that their political convictions were fundamentally different; an influence of Aristotle on Alexander is in any case not recognizable. Aristotle is said to have achieved the reconstruction of his destroyed hometown Stageira at the Macedonian court; however, the credibility of this message is doubtful.

The execution of Hermias by the Persians in 341/340 touched Aristotle deeply, as a poem dedicated to the memory of his friend shows.

When after the death of Speusippos in 339/338 BC When the post of Scholarchen (headmaster) became vacant in the academy , Aristotle could not take part in the election of the successor only because of his absence; but he was still considered an academician. Later he went to Delphi with his great-nephew, the historian Kallisthenes , to draw up a list of winners for the Pythian Games on behalf of the local Amphictyons .

Second stay in Athens

With the destruction of the rebellious city of Thebes in 335 BC The open resistance against the Macedonians in Greece collapsed, and Athens also came to terms with the balance of power. Therefore Aristotle could 335/334 BC Returned to Athens and began to research and teach there again, but was no longer active at the academy, but in a public high school, the Lykeion . Here he created his own school, which Theophrastus took over after his death. New excavations may have made it possible to identify the building complex. In the legal sense, Theophrastus founded the school and acquired the property - the later common names Peripatos and Peripatetic specifically for this school have not yet been attested for the time of Theophrastus. The abundance of material that Aristotle collected (about the 158 constitutions of the Greek city-states) suggests that he had numerous collaborators who also researched outside of Athens. He was wealthy and owned a large library. His relationship with the Macedonian governor Antipater was friendly.

Withdrawal from Athens, death and descendants

After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC At first anti-Macedonian forces prevailed in Athens and other Greek cities. Delphi revoked a decree of honor bestowed on Aristotle. In Athens there was hostility that made it impossible for him to continue working quietly. Therefore he left 323/322 BC. BC Athens. He allegedly said on the occasion that he did not want the Athenians to attack philosophy a second time (after they had already sentenced Socrates to death). He retired to his mother's house in Chalkis on Euboia . There he died in October 322 BC. Chr.

Aristotle was married to Pythias , a relative of his friend Hermias. He had a daughter of her, who was also called Pythias. After the death of his wife, Herpyllis , who was of low origin, became his partner; she may have been the mother of his son Nicomachus. In his will, the execution of which he entrusted to Antipater, Aristotle regulated, among other things, the future marriage of his daughter, who was still underage, and made provisions for the material security of Herpyllis.

plant

Note: Evidence from works by Aristotle is given as follows: title (abbreviations are resolved in the first place in the chapter via link) and, if applicable, book and chapter information as well as the Bekker number . The Bekker number indicates an exact place in the corpus . It is noted in good modern editions.

Due to breaks and inconsistencies in Aristotle's work, research has deviated from the previously widespread notion that the traditional work forms a closed, well-composed system. These breaks are probably due to developments, changes in perspective and different accentuations in different contexts. Since a certain chronological order of his writings cannot be determined, statements about Aristotle's actual development remain conjectures. Although his work does not in fact constitute a finished system, his philosophy has properties of a potential system.

Tradition and character of the scriptures

Various ancient registers attribute almost 200 titles to Aristotle. If the statement by Diogenes Laertios is correct, Aristotle left a life's work of over 445,270 lines (although this number probably does not take into account two of the most extensive works - Metaphysics and Nicomachean Ethics ). Only about a quarter of it has survived.

In research, two groups are distinguished: exoteric writings (which have been published for a wider audience) and esoteric (which were used for internal school use). All exoteric writings are not available or only in fragments, most of the esoteric texts have been handed down. The writing The Constitution of Athens was considered lost and was only found in papyrus form at the end of the 19th century .

Exoteric and esoteric writings

The exoteric writings mainly consisted of dialogues in the tradition of Plato, e.g. B. the Protreptikos - a promotional pamphlet for philosophy -, studies such as Über die Ideen, but also propaedeutic collections. Cicero praises her "golden flow of speech". The esoteric writings, also known as pragmaties , have often been referred to as lecture manuscripts; this is not certain and for some scriptures or sections also improbable. It is widely believed that they grew out of teaching. Large parts of the pragmatics show a peculiar style full of omissions, hints, leaps of thought and duplicates. In addition, however, there are also stylistically refined passages which (besides the duplicates) make it clear that Aristotle repeatedly worked on his texts and suggest the possibility that he was thinking of publishing at least some of the pragmaties. Aristotle assumes that his addressees have a great deal of previous knowledge of foreign texts and theories. References to the exoteric scriptures show that knowledge of them is also assumed.

The manuscripts of Aristotle

After the death of Aristotle, his manuscripts initially remained in the possession of his students. When his pupil and successor Theophrastus died, his pupil Neleus is said to have received the library of Aristotle and with it - out of anger at not having been elected successor - left Athens with some supporters towards skepticism near Troy in Asia Minor. The ancient reports mention an adventurous and dubious story, according to which the heirs of Neleus buried the manuscripts in the cellar to protect them from unauthorized access, but where they were then lost. It is largely certain that in the first century BC Chr. Apellicon of Teos has acquired the damaged manuscripts and brought to Athens and that after the conquest of Athens by Sulla v in 86th Came to Rome. His son commissioned Tyrannion in the middle of the century to sift through the manuscripts and to add further material.

Other ways of transmission

Even if his manuscripts along with the library of Aristotle were lost for centuries, it is undisputed that his teaching was at least partially known in Hellenism, above all through the exoteric writings and, indirectly, probably also through Theophrastus' work. In addition, some pragmatics must have been known, of which there may have been copies in the library of Peripatos.

Andronikos of Rhodes. The first edition

On the basis of the work of Tyranny, his pupil Andronikos of Rhodes got hold of in the second half of the first century BC. The first edition of the Aristotelian Pragmatia, which was probably only partly based on the manuscripts of Aristotle. The writings in this edition form the Corpus Aristotelicum . Presumably some compilations of previously disordered books as well as some titles go back to this edition. Andronikos may have made changes to the text - such as cross-references. In the case of the numerous duplicates, he may have arranged different texts on the same topic one after the other. The current arrangement of the fonts largely corresponds to this edition. Andronikos did not take into account the exoteric writings still available at his time. They were subsequently lost.

Manuscripts and printed editions

Today's editions are based on copies that go back to the Andronikos edition. With over 1000 manuscripts, Aristotle is the most widely distributed among the non-Christian Greek-speaking authors. The oldest manuscripts date from the 9th century. Because of its size, the Corpus Aristotelicum is never completely contained in a single codex . After the invention of the printing press, the first printed edition by Aldus Manutius appeared in 1495–1498 . The complete edition of the Berlin Academy obtained by Immanuel Bekker in 1831 is the basis of modern Aristotle research. It is based on collations of the best manuscripts available at the time. According to her page, column and line counting ( Bekker counting ), Aristotle is still quoted everywhere today. For a few works it still provides the authoritative text; however, most of them are now available in new individual editions.

Classification of the sciences and fundamentals

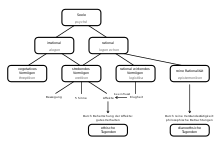

| Classification of science by Aristotle in the 4th century BC Chr. (After Ottfried Höffe) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Aristotle's work covers much of the knowledge available at the time. He divides it into three areas:

- theoretical science

- practical science

- poietic science

Theoretical knowledge is sought for its own sake. Practical and poietic knowledge has another purpose, the (good) action or a (beautiful or useful) work. Theoretical knowledge is further subdivided according to the nature of the objects: (i) The First Philosophy ("metaphysics") treats (with substance theory, principle theory and theology) the independent and unchangeable, (ii) the natural science independent and changeable and (iii ) Mathematics deals with the dependent and unchangeable ( Met. VI 1). The writings that do not appear in this classification seem to have a special position, which were only compiled in the so-called Organon after the death of Aristotle .

The most important scriptures can be roughly divided as follows:

| 'Organon' | Theoretical Science | Practical science | Poietic Science |

|---|---|---|---|

| Categories (Cat.) | Metaphysics (met.) | Nicomachean Ethics (EN) | Rhetoric ( rhetoric ) |

| De interpretatione (Int.) | Physics (phys.) | Eudemian Ethics (EE) | Poetics (poet.) |

| Analytica priora (An. Pr.) | De anima (An.) | Politics (pol.) | |

| Analytica posteriora (An. Post.) | Historia animalium (HA) | ||

| Topic (Top.) | De generatione et corruptione (Gen. corr.) | ||

| Sophistic refutations (Soph. El.) | De generatione animalium (GA) | ||

| De partibus animalium (PA) |

For Aristotle, this division of the sciences is accompanied by the insight that every science has its own principles due to its peculiar objects. So in practical science - the realm of action - there cannot be the same precision as in the realm of theoretical sciences. A science of ethics is possible, but its propositions are only valid as a rule. Nor can this science dictate the correct course of action for all possible situations. Rather, ethics can only provide imprecise knowledge in outline, which, moreover, does not in itself enable a successful life, but has to be linked to experience and existing attitudes ( EN I 1 1094b12-23).

Aristotle was convinced that “people are naturally gifted enough for the truth” ( Rhet. I 1, 1355a15-17). Therefore, he typically first goes through (generally or with predecessors) recognized opinions (endoxa) and discusses their most important problems (aporiai) in order to analyze a possible true core of these opinions (EN VII 2). What is noticeable is his preference to lay the foundation for the argument in an universal statement at the beginning of a writing and to define the specific subject.

Language, logic and knowledge

The organon

The subject area of language, logic and knowledge is mainly dealt with in the writings that are traditionally compiled under the title Organon (Greek for tool, method). This compilation and its title are not from Aristotle and the order is not chronological. The text Rhetoric does not belong to the Organon , but is very close to it in terms of content because of the way it deals with the subject. A justification for the compilation consists in the common methodological- propaedeutic character.

Meaning theory

In the following section - which is considered to be the most influential text in the history of semantics - Aristotle distinguishes four elements that have two different relationships to one another, a mapping relationship and a symbolic relationship:

“Now [i] the (linguistic) utterances of our voice are symbols for [ii] what happens to our soul (while speaking), and [iii] our written utterances are in turn symbols for the (linguistic) utterances of our voice. And just as not all people write with the same letters, they also do not speak the same language. The spiritual experiences, however, for which this (spoken and written) is a sign in the first place, are the same for all people; and, moreover, [iv] the things of which these (spiritual experiences) are images are the same for all. "

Spoken and written words are accordingly different in people; written words symbolize spoken words. Mental experiences and things are the same with all people; mental experiences depict things. Accordingly, the relation of speech and writing to things is determined by agreement, whereas the relation of mental impressions to things is natural.

Truth and falsehood only come through the connection and separation of several ideas. The individual words do not establish a connection either and therefore cannot be either true or false on their own. True or false until the entire statement can therefore set (logos apophantikos) be.

Predicates and properties

Some linguistic and logical statements are fundamental to Aristotle's philosophy and also play an important role outside of the (in the broader sense) logical writings. This is particularly about the relationship between predicates and (essential) properties.

Definitions

Aristotle does not understand a definition primarily as a nominal definition (which he also knows; see An. Post. II, 8-10), but rather a real definition. A nominal definition only indicates opinions that are associated with a name. What underlies these opinions in the world is given by the real definition: a definition of X indicates necessary properties of X and what it means to be an X: the essence. A possible object of a definition is (only) what a (universal) being has, in particular species such as humans. A species is defined by specifying a (logical) genus and the species-forming difference. In this way, humans can be defined as rational (difference) living beings (species). Individuals cannot be captured by definition, but only assigned to their respective species.

Categories as statement classes

Aristotle teaches that there are ten irreversible modes of expressions that answer the questions What is X? What is X ? , Where is X? etc. answer (→ the complete list ). The categories have both a linguistic-logical and an ontological function, because predicates are predicates of an underlying subject ( hypokeimenon ) (e.g. Socrates) on the one hand , and properties are assigned to it on the other (e.g. white, human ). Correspondingly, the categories represent the most general classes of predicates as well as of beings. Aristotle distinguishes the category of substance , which contains essential predicates necessarily, from the others, which contain accidental predicates.

If one of Socrates man predicted (says), so it is a significant statement that defines the subject (Socrates), what it is, so the substance names. This obviously differs from a statement about how Socrates is in the marketplace, with which one indicates something accidental, namely where Socrates is (i.e. names the place).

Deduction and Induction: Types of Arguments and Means of Knowledge

Aristotle differentiates between two types of arguments or means of knowledge: deduction (syllogismos) and induction (epagôgê). The agreement with the modern terms deduction and induction is broad, but not complete. Deductions and inductions play central roles in the various areas of Aristotelian argumentation theory and logic. Both originate from dialectics.

Deduction

According to Aristotle, a deduction consists of premises (assumptions) and one of these different conclusions . The conclusion necessarily follows from the premises. It cannot be wrong if the premises are true.

"A deduction (syllogismos) is an argument (logos) in which, if certain things are presupposed, something different from the presupposed necessarily results from the fact that this is the case."

The definition of deduction (syllogismos) is thus wider than that of deduction ( treated below ) - traditionally called syllogism - which consists of two premises and three terms. Aristotle distinguishes between dialectical , eristic , rhetorical and demonstrative deductions. These forms differ mainly in the nature of their premises.

induction

Aristotle explicitly contrasts deduction with induction; its purpose and function, however, is not as clear as that of deduction. He calls her

“The ascent from the individual to the general. For example, if the helmsman who knows his way around is the best (helmsman) and so is the case with the charioteer, then the one who knows his way around is the best in every area. "

It is clear to Aristotle that such a transition from singular to general sentences is not logically valid without further conditions ( An. Post. II 5, 91b34 f.). Corresponding conditions are fulfilled, for example, in the original context of the logic of argumentation of dialectics, since the opponent has to accept a general clause introduced by induction if he cannot give a counterexample.

Above all, however, induction has the function of making the general clear in other, non-inferring contexts by citing individual cases - be it as a didactic, or as a heuristic procedure. Such induction provides plausible reasons for believing a general proposition to be true. But nowhere does Aristotle inductively justify the truth of such a proposition without further conditions.

Dialectic: theory of reasoning

The dialectic dealt with in the Topik is a form of argumentation which (according to its genuine basic form) takes place in a dialogical disputation. It probably goes back to practices in Plato's academy . The aim of the dialectic is:

"The essay intends to find a method by which we will be able to deduce from accepted opinions (endoxa) about any problem presented , and if we make an argument ourselves, not to say anything contradicting."

The dialectic therefore has no specific subject area, but can be applied universally. Aristotle determines the dialectic through the nature of the premises of this deduction. Their premises are recognized opinions (endoxa), that is

"Those deemed correct by either (a) all or (b) most or (c) the experts and either (ci) all or (cii) most or (ciii) the best known and most recognized."

For dialectical premises it is irrelevant whether they are true or not. But why recognized opinions? In its basic form, dialectic takes place in an argumentative competition between two opponents with precisely assigned roles. On a submitted problem of the form 'Is SP or not?' the respondent must commit himself to one of the two possibilities as a thesis. The dialectical conversation consists in the fact that a questioner presents statements to the respondent, which the respondent must either affirm or deny. The questions answered apply as premises. The aim of the questioner is to use the affirmative or negative statements to form a deduction so that the conclusion refutes the initial thesis or something absurd or a contradiction follows from the premises. The method of dialectic has two components:

- find out which premises result in an argument for the sought conclusion.

- find out which premises the respondent accepts.

For 2. the different types (a) - (ciii) of recognized opinions offer the questioner clues as to which questions the respective respondent will answer in the affirmative, that is, which premises he can use. Aristotle calls for lists of such recognized opinions to be drawn up (Item I 14). Presumably he means separate lists after groups (a) - (ciii); these are in turn sorted according to criteria.

For 1. the instrument of the Topen helps the dialectician to build up his argument. A topos is a construction guide for dialectical arguments, that is, to find suitable premises for a given conclusion. Aristotle lists in the Topik to about 300 of these Topen. The dialectician knows these Topen by heart, which can be arranged based on their properties. The basis of this order is the system of predicables .

According to Aristotle, dialectic is useful for three things: (1) as an exercise, (2) for meeting the crowd, and (3) for philosophy. In addition to (1) the basic form of argumentative competition (in which there is a jury and rules and which probably goes back to practices in the academy) there are also applications with (2) that are dialogical but not designed as a rule-based competition, and with (3) those that are not dialogical, but in which the dialectician in the thought experiment (a) goes through difficulties in both directions (diaporêsai) or also (b) investigates principles (Top. I 4). For him, however, dialectics is not the method of philosophy or a fundamental science, as it was with Plato .

Rhetoric: Theory of Belief

Aristotle defines rhetoric as "the ability to look at what is possibly convincing (pithanon) in every thing " ( Rhetoric I 2, 1355b26 f.). He calls it a counterpart (antistrophos) to the dialectic. Because, like dialectic, rhetoric is without a delimited subject area, and it uses the same elements (such as tops, recognized opinions, and especially deductions), and dialectical reasoning corresponds to conviction based on rhetorical deductions.

Rhetoric was of paramount importance in fourth-century democratic Athens , especially in the popular assembly and the courts, which were occupied by lay judges determined by lot. There were numerous rhetoric teachers and rhetoric manuals emerged.

Aristotle's dialectical rhetoric is a reaction to the rhetoric theory of his time, which - as he criticizes - provides mere set pieces for speech situations and instructions on how one can cloud the judgment of the judges through slander and the arousal of emotions. In contrast, his dialectical rhetoric is based on the view that we are most convinced when we believe that something has been proven (Rhet. I 1, 1355a5 f.). He also expresses in the weighting of the three means of persuasion that the rhetoric is fact-oriented and must discover and exploit the persuasive potential inherent in the matter. These are:

- the speaker's character ( ethos )

- the emotional state of the listener ( pathos )

- the argument ( logos )

He considers the argument to be the most important means.

Among the arguments, Aristotle distinguishes the example - a form of induction - and the enthymeme - a rhetorical deduction (again the enthymeme is more important than the example). Entyhmeme is a kind of dialectical deduction. Its distinctive feature due to the rhetorical situation is that its premises are only the accepted opinions that are believed to be true by all or most . (The widespread, curious view that the enthymeme is a syllogism in which one of the two premises is missing is not represented by Aristotle ; it is based on a misunderstanding of 1357a7 ff., Which has already been documented in the ancient commentary.) The speaker therefore convinces the audience by saying derives an assertion (as a conclusion) from the beliefs (as premises) of the listener. The construction instructions for these enthymemes provide rhetorical topics, e.g. B .:

“Another (topos arises) from the more and less, such as: 'If the gods don't know everything, then probably hardly the people.' Because that means: If something does not belong to the person to whom it could be more appropriate, then it is obvious that it does not belong to the person to whom it could not be so appropriate. "

Aristotle criticizes contemporary rhetoric teachers for neglecting the argument and aiming exclusively at arousal of emotions, for example through behavior such as whining or bringing the family to the court hearing, which prevents the judges from making an objective judgment. According to Aristotle's theory, all emotions can be defined by taking three factors into account. One asks: (1) about what, (2) to whom and (3) in which state does someone feel the respective emotion? Here's the definition of anger:

"So anger [3] is supposed to be a pain-related pursuit of an alleged retribution [1] for an alleged disparagement of oneself or one of his own [2] by those who are not entitled to disparagement."

If the speaker can use this definition knowledge to make it clear to the audience that the relevant facts are present and that they are in the appropriate state, then they will experience the corresponding emotion. If the speaker uses this method to highlight existing facts of a case, he does not distract from the matter - as was the case with the criticized predecessors - but only promotes emotions appropriate to the case and thus prevents inappropriate ones. After all, the speaker's character should appear credible to the audience based on his speech , that is, virtuous, intelligent and benevolent (Rhet. I 2, 1356a5–11; II 1, 1378a6–16)

The linguistic form also serves an argumentative-factual rhetoric. Aristotle defines the optimal form (aretê) in that it is primarily clear, but neither banal nor too sublime (Rhet. III 2, 1404b1–4). With such a balance, it stimulates interest, attention and understanding and is pleasant. Among the stylistic devices, the metaphor in particular fulfills these conditions.

Syllogistic logic

If Aristotle's dialectical logic consists in a method of consistent reasoning, then his syllogistic consists in a theory of proving itself. In the syllogistics he establishes, Aristotle shows which conclusions are valid. For this he uses a form that is simply called syllogism (the Latin translation of syllogismos ) in tradition because of the meaning of this logic . Every syllogism is a (special form of) deduction (syllogismos) , but not every deduction is a syllogism (because Aristotle's very general definition of deduction describes many possible types of arguments). Aristotle himself does not use a term of his own to distinguish the syllogism from other deductions.

A syllogism is a special deduction that consists of exactly two premises and one conclusion. Premises and conclusions together have exactly three different terms, terms (represented in the table by A, B, C). The premises have exactly one term in common (in Table B) that does not appear in the conclusion. Aristotle distinguishes the following syllogistic figures through the position of the common term, the middle term (here always B):

| No. | 1st figure: middle term is in (1) subject, in (2) predicate | 2nd figure: mean term is in (1) and in (2) predicate. | 3rd figure: middle term is subject in (1) and in (2). |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | AxB | BxA | AxB |

| (2) | BxC | BxC | CxB |

| Conclusion | AxC | AxC | AxC |

A predicate (P) (e.g. 'mortal') can either be assigned or denied to a subject (S) (e.g. 'Greek'). This can take place in particular or in general form. Thus there are four forms in which S and P can be connected with each other, as the following table shows (according to De interpretatione 7; the vowels have been used for the respective statement type and also in syllogistics since the Middle Ages).

| Art | to speak | arrange |

|---|---|---|

| general | Every S is P: a | Every S is not P = No S is P: e |

| particular | Any S is P: i | Some S is not P = Not every S is P: o |

The syllogism uses exactly these four types of statements in the following form:

| Inverse position! common notation | Normal word order | meaning |

|---|---|---|

| A belongs to all B. | AaB | All B are A |

| A does not belong to any B. | AeB | No B is A |

| A belongs to some B. | AiB | Some B are A. |

| A does not apply to all B. | AoB | Some B are not A. |

Aristotle examines the following question: Which of the 192 possible combinations are logically valid deductions? For which syllogisms is it impossible that if the premises are true, the conclusion is false? He distinguishes perfect syllogisms, which are immediately apparent, from imperfect ones. He traces the imperfect syllogisms back to the perfect ones by means of conversion rules (he calls this process analysis ) or proves them indirectly. A perfect syllogism is Barbara - so called since the Middle Ages :

| No. | Aristotelian, inverse position | common notation | Normal position |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | A belongs to all B. | AaB | All people are mortal. |

| (2) | B applies to all C. | BaC | All Greeks are human. |

| Conclusion | So: A applies to all C. | AaC | So: all Greeks are mortal. |

More valid syllogisms and their proofs can be found in the article Syllogism .

Aristotle uses the syllogistics elaborated in the Analytica Priora in his philosophy of science , the Analytica Posteriora .

Aristotle also develops a modal syllogistic that includes the terms possible and necessary . This modal syllogistic is much more difficult to interpret than the simple syllogistic. Whether a consistent interpretation of this modal syllogistic is even possible is still controversial today. Aristotle's definition of possible is problematic in terms of interpretation, but also significant . He differentiates between the so-called one-sided and the two-sided option:

- One-sided: p is possible if non-p is not necessary .

- Two-sided: p is possible if p is not necessary and not-p is not necessary, i.e. p is contingent .

Thus the indeterminism advocated by Aristotle can be characterized as the state that is contingent.

Canonical sentences

In Aristotelian logic, a distinction is made between the following contradicting and contradicting sentence types - F and G stand for subject and predicate:

| designation | formulation |

|---|---|

| A sentences | "All F are G." |

| E-phrases | "All F are not G." (= No F is G.) |

| I-sentences | "There is (at least) one F that is a G." |

| O-sentences | "There is (at least) one F that is not a G." |

These "canonical sentences" belong to the foundation of traditional logic and are used, among other things, for simple or limited conversion .

Knowledge and science

Levels of knowledge

Aristotle differentiates between different levels of knowledge , which can be represented as follows ( Met. I 1; An. Post. II 19):

| Epistemic level | What living beings |

|---|---|

| Knowledge | human |

| Experience | some animals in a restricted sense; human |

| memory | most living things |

| perception | all creatures |

With this graduation Aristotle also describes how knowledge is created: From perception creates memory and from memory by pooling memory content experience . Experience consists in the knowledge of a large number of specific individual cases and only indicates that , is mere factual knowledge. Knowledge (or science; epistêmê includes both) differs from experience in that it

- is general;

- not only the that of a fact, but also the why, the reason or the explanatory cause .

In this cognitive process, according to Aristotle, we advance from what is known to us and closer to sensory perception, to what is known in itself or by nature , to the principles and causes of things. The fact that knowledge comes first and is superior does not mean, however, that in a specific case it contains the other levels in the sense that it replaces them. In action, moreover, experience as knowledge of the individual is sometimes superior to the forms of knowledge that are general (Met. 981a12-25).

Causes and Demonstrations

As a rule, Aristotle does not understand a cause ( aitia ) to be an event A that is different from a caused event B. The investigation of causes does not serve to predict effects, but to explain facts. An Aristotelian cause gives a reason in response to certain why questions. (Aristotle differentiates between four types of causes, which are dealt with in more detail here in the section on natural philosophy .)

According to Aristotle, knowledge of causes takes the form of a certain deduction : the demonstration (apodeixis) of a syllogism with true premises that give the causes for the facts expressed in the conclusion. An example:

| No. | Inverse position | Formally | Normal word order |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st premise | To be made of bronze belongs to all statues. | BaC | All statues are made of bronze. |

| 2nd premise | Bronze is supposed to be difficult. | AaC | Bronze is difficult. |

| Conclusion | All statues have to be heavy. | AaB | All statues are heavy. |

Aristotle speaks of the fact that the premises of some demonstrations are principles ( archē; literally beginning, origin), first true propositions that cannot themselves be demonstrated demonstratively.

Non-provable sentences

In addition to the principles, the existence and the properties of the treated objects of a science as well as certain axioms common to all sciences according to Aristotle cannot be proven by demonstrations, such as the theorem of contradiction . Aristotle shows that the principle of contradiction cannot be denied. It reads: X cannot and cannot belong to Y in the same respect (Met. IV 3, 1005b19 f.). Aristotle argues that whoever denies this must say something and thus something specific. If he z. B. says 'human', it means humans and not non-humans. With this commitment to something specific, however, he presupposes the principle of contradiction. This even applies to actions insofar as a person walks around a well and does not fall into it.

The fact that these propositions and also principles cannot be demonstrated is due to Aristotle's solution to a justification problem : If knowledge contains justification, then in a concrete case of knowledge this leads either to (a) recourse, (b) a circle or (c) to fundamental propositions that cannot be justified. Principles in an Aristotelian demonstrative science are those sentences that are not demonstrated but are known in another way ( An. Post. I 3).

The relationship between definition, cause and demonstration

Aristotle also speaks of the fact that if the premises are principles, they can also represent definitions . The following example illustrates how demonstration, cause and definition relate to one another: The moon has an eclipse at time t, because (i) whenever something is in the sun's shadow, it has an eclipse and (ii) the moon at the time t lies in the sun's shadow of the earth.

Demonstration:

| No. | Inverse position | Formally |

|---|---|---|

| 1st premise | Darkness occurs in all cases in which the earth obscures the sun. | AaB |

| 2nd premise | The moon is obscured by the earth at time t. | BIC |

| Conclusion | Eclipse comes to the moon at time t. | AiC |

Middle term : obscuring the sun by the earth.

Cause: The moon is obscured by the earth at time t.

The definition here would be something like: lunar eclipse is the case in which the earth covers the sun. It does not explain the word 'lunar eclipse'. Rather, it indicates what a lunar eclipse is. By giving the cause, one progresses from a fact to its reason. The process of analysis consists of looking for the next cause from the bottom up to a known issue until a final cause is reached.

Status of the principles and function of the demonstration

The Aristotelian model of science was understood as a top-down evidence method in modern times and up into the 20th century . The unprovable principles are necessarily true and are obtained through induction and intuition (nous) . All the propositions of a science would follow - in an axiomatic structure - from its principles. Science is based on two steps: First, the principles are grasped intuitively, then knowledge is demonstrated from them top-down.

Opponents of this top-down interpretation primarily question that for Aristotle

- the principles are always true;

- the principles are obtained through intuition ;

- The function of the demonstration is to develop knowledge from the highest principles.

One direction of interpretation claims that the demonstration has a didactic function. Since Aristotle does not follow his philosophy of science in the scientific writings, it does not explain how research is carried out, but how it should be presented didactically .

Another interpretation also rejects the didactic interpretation, since applications of the epistemological model can very well be found in scientific writings. Above all, however, she criticizes the first reading to the effect that it does not distinguish between ideal knowledge and knowledge culture ; for Aristotle considers principles to be fallible and the function of demonstration to be heuristic . She reads the demonstration bottom-up : For known facts , the causes would be sought with the help of the demonstration. Scientific research is based on empirical (mostly universal) propositions that are better known to us . For such a conclusion, premises are sought that indicate the causes for the relevant facts.

The scientific research process now consists in analyzing, for example, the link between gravity and statue or moon and darkness in such a way that one looks for mean terms that link them together as causes. In the simplest case there is only one mean term, in others there are several. The knowledge from the explanatory premises to the declared universal empirical propositions is then presented top-down. The premises indicate the reason for the facts described in the conclusion. The aim of every discipline is such a demonstrative presentation of knowledge in which the non-demonstrable principles of this science are premises.

Grasp the principles

How the principles of Aristotle are captured remains unclear and is controversial. Presumably they are formed by general terms that arise through an inductive process , an ascent within the knowledge levels described above: Perception becomes memory, repeated perception condenses into experience, and from experience we form general terms. With this perception-based conception of the formation of general concepts, Aristotle rejects both conceptions that derive general concepts from a higher level of knowledge and those that claim that general concepts are innate. The principles and definitions are probably formed on the basis of these general terms. The dialectic, the questions in the form 'Does P apply to S or not?' is probably a means of testing principles. The assets that captures these basic general concepts and definitions, is the spirit, the insight ( nous ).

Natural philosophy

nature

In Aristotle Naturphilosophie means Nature ( physis ) two things: firstly, the primary subject area from the naturally existing objects (people, animals, plants, the elements ), the from artifacts differ. On the other hand, movement (kínēsis) and rest (stasis) form the origin, or the basic principle ( archē ) of all nature (Phys. II 1, 192b14). Movement in turn means change (metabolē) (Phys. II 1,193a30). For example, locomotion is a form of change. Likewise, the “proper movements” of the body when it grows or decreases (for example through food intake) represent a change. The two terms, kínēsis and metabolē, are consequently inseparable for Aristotle. Together they form the basic principle and the beginning of all natural things. With artifacts, the principle of every change comes from outside ( Phys. II 1, 192b8-22). The science of nature therefore depends on the types of change.

Definition, principles and modes of change

A process of change in X is given when X, which (i) in reality has property F and (ii) in possibility of G, realizes property G. In the case of bronze (X), which in reality is a lump (F) and possibly a statue (G), there is a change when the bronze in reality becomes the shape of a statue (G) ; the process is complete when the bronze is in this shape . Or when the uneducated Socrates is formed, a state is realized which, if possible, was already there. The change process is characterized by its transitional status and presupposes that something that is possible can be realized (Phys. III 1, 201a10–201b5).

For all change processes, Aristotle (in accordance with his natural-philosophical predecessors) considers opposites to be fundamental. He also advocates the thesis that in a process of change these opposites (like formed-uneducated ) always appear on a substrate or underlying (hypokeimenon) , so that his model has the following three principles:

- Substrate of change (X);

- Initial state of change (F);

- Target state of change (G).

If the uneducated Socrates is formed, he is Socrates at every point of change. Accordingly, the bronze remains bronze. The substrate of the change on which it takes place remains identical with itself. Aristotle sees the initial state of change as a state that lacks the corresponding property of the target state ( Privation ; Phys. I 7).

Aristotle distinguishes four types of change:

- Qualitative change

- Quantitative change

- Locomotion

- Arising / passing away.

With every change - according to Aristotle - there is an underlying, numerically identical substrate (Physik I 7, 191a13–15). In the case of qualitative, quantitative and local change, this is a concrete individual thing that changes its properties, its size or its position. How does this behave when specific individual things arise / disappear? The Eleatics had advocated the influential thesis that arising was not possible, since they considered it contradicting if beings emerged from non-being (they saw a similar problem with arising from beings). The solution of the atomists that origin is a process in which by mixing and separating immortal and unchangeable atoms from old new individual things emerge, leads, according to Aristotle's view, illegitimate creation back to qualitative change ( Gen. Corr. 317a20 ff.).

Form and matter when arising / disappearing

Aristotle's analysis of arising / passing away is based on the innovative distinction between form and matter ( hylemorphism ). He accepts that no concrete individual thing arises from non-being, but analyzes the case of arising as follows. A concrete individual thing of type F does not arise from a non-existent F, but from an underlying substrate that does not have the form F: matter.

A thing arises when matter takes on a new form. This is how a bronze statue is created by a bronze mass assuming a corresponding shape. The finished statue is made of bronze, the bronze is the base of the statue as material. The answer to the Eleates is that a statue that does not exist is equivalent to bronze as matter, which becomes a statue through the addition of a form. The development process is characterized by different degrees of being. The actual, actual, shaped statue arises from something that is potentially a statue, namely bronze as matter (Phys. I 8, 191b10–34).

Matter and form are aspects of a concrete individual thing and do not appear independently. Matter is always the substance of a certain thing that already has a form. It is a relative concept of abstraction to form. By structuring such matter in a new way, a new individual thing arises. A house is made up of form (the blueprint) and material (wood and brick). As the material of the house, bricks are clay shaped and configured in a certain way by a certain process. Aristotle understands form to mean the external shape (this only applies to artifacts), usually the internal structure or nature, that which is captured by a definition. The shape of an object of a certain type describes the requirements, which matter is suitable for it and which is not.

Locomotion

According to Aristotle, movements take place either naturally or contrary to nature (violent). Only living beings move of their own accord, everything else is either moved by something or it strives as straight as possible towards its natural place and comes to a standstill there.

The natural location of a body depends on the type of matter prevailing in it. When water or earth predominates, the body moves to the center of the earth, the center of the world; when fire or air dominates, it strives upwards. Earth is only heavy, fire is absolutely light, water is relatively heavy, and air is relatively light. The natural place of fire is above the air and below the lunar sphere. Lightness and weight are properties of bodies that have nothing to do with their density. With the introduction of the idea of absolute heaviness and absolute lightness (weightlessness of fire), Aristotle rejects the conception of Plato and the atomists, who considered all objects to be heavy and understood weight as a relative quantity.

The fifth element, the ether of heaven, is massless and moves eternally in uniform circular motion around the center of the world. The ether fills the space above the lunar sphere; it is not subject to any change other than local movement. The assumption that different laws apply on earth and in the sky is necessary for Aristotle because the movement of the planets and fixed stars does not come to rest.

Aristotle assumes that any movement of space requires a medium that either acts as a moving force or offers resistance to movement; a continuous movement in a vacuum is in principle impossible. Aristotle even rules out the existence of a vacuum.

The kinetics of Aristotle was to develop a new inertia term by Galileo and Newton influential.

causes

In order to have knowledge of change processes and thus of nature, one must - according to Aristotle - know the corresponding causes ( aitiai ) (Phys. I 1, 184a10-14). Aristotle claims that there are exactly four types of causes, each of which answers the question why in different ways and that, as a rule, must all be stated in a complete explanation (Phys. II 3, 194b23-35):

| designation | traditional name | Explanation | Example: causes of a house |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material cause | causa materialis | that from which a thing arises and is thereby contained in it | Wood and brick |

| Form cause | causa formalis | the structure; that which indicates what the being of a thing consists of | Blueprint |

| Cause of action or movement | causa efficiens | that where the first cause of movement and rest or an effect comes from | architect |

| Target or purpose cause | causa finalis | the goal or purpose for whose sake something happens | Protection against bad weather |

The Aristotelian concept of cause differs largely from the modern one. As a rule, different causes apply to the explanation of the same fact or object. The form cause often coincides with the movement cause and the final cause. The cause of a house are bricks and wood, the blueprint, the architect and the protection against storms. The latter three often coincide, for example insofar as the purpose of protection from storms determines the architect's blueprint (in the mind).

The final cause has been criticized from the standpoint of modern mechanistic physics. However , Aristotle differs largely from a nature that is generally teleologically oriented, as in Plato. For him, final causes occur in nature, especially in biology, namely in the functional structure of living beings and species reproduction .

metaphysics

Metaphysics as First Philosophy

Aristotle does not use the term " metaphysics ". Nevertheless, one of his most important works traditionally bears this title. The metaphysics is compiled by a later editor collection of individual studies that cover a more or less coherent range of topics, by inquiring about the principles and causes of existence and after the competent science. It is unclear whether the title ( ta meta ta physika: the <writings, things> according to physics) has a purely bibliographic or a factual background.

In metaphysics, Aristotle speaks of a science that takes precedence over all other sciences and which he calls first philosophy, wisdom (sophia) or theology. This first philosophy is characterized in this collection of individual studies in three ways:

- as a science of the most general principles that are central to Aristotle's philosophy of science (→ theorem of contradiction )

- as the science of beings as beings, the Aristotelian ontology

- as science of the divine, the Aristotelian theology (→ theology )

Whether or to what extent these three projects are related aspects of the same science or independent individual projects is controversial. Aristotle later deals with subjects named metaphysically in other writings as well.

ontology

In the Corpus Aristotelicum there are two works, the early categories and the late metaphysics, different theories of beings.

Substances in the categories

The categories that form the first script in the Organon are probably the most influential work of Aristotle and the history of philosophy in general.

The early ontology of categories deals with the questions 'What is actually being?' and 'How are beings ordered?' and is to be understood as a criticism of Plato's position. The presumed train of thought can be outlined as follows. A distinction is made between properties that belong to individual things (P comes to S). There are two possible interpretations for this: The real being, the substance ( ousia ) are

- abstract, independently existing archetypes as the cause and object of knowledge of properties.

- concrete individual things as carriers of properties.

Aristotle himself reports ( Met. I 6) that Plato taught that one must distinguish from the perceptible individual things separate, non-perceptible, unchangeable, eternal archetypes . Plato assumed that there could be no definitions (and thus from his point of view also knowledge) of the individual things that are constantly changing. The objects of definition and knowledge are for him the archetypes ( ideas ) as what is causal for the order structure of beings. This can be illustrated by an individual and numerically identical idea of the human being, which is separate from all human beings and which is the cause of being human and which is the subject of knowledge for the question 'What is a human being?'.

Aristotle's division of beings into categories seems to be differentiated from Plato's position outlined above. He orients himself to the linguistic structure of simple sentences of the form 'S is P' and the linguistic practice, whereby he does not explicitly distinguish the linguistic and the ontological level.

Some expressions - like 'Socrates' - can only take the subject position S in this linguistic structure, everything else is predicted by them. The things which fall into this category of substance and which he calls First Substance are ontologically independent; they don't need any other thing in order to exist. Hence they are ontologically primary because everything else depends on them and nothing would exist without them.

These dependent properties require a single thing, a first substance as a carrier on which they occur. Such properties (e.g. white, sitting) may or may not apply to an individual thing (e.g. Socrates) and are therefore accidental properties. This affects everything outside of the substance category.

For some properties (e.g. 'man') it is now true that they can be predicated of an individual thing (e.g. Socrates) in such a way that their definition (reasonable living being) also applies to this individual thing. They therefore necessarily come to him . These are the species and the genus. Because of this close relationship, in which the species and the genus indicate what a first substance is in each case (e.g. in the answer to the question 'What is Socrates?': 'A person'), Aristotle calls it the second substance. A second substance also depends ontologically on a first substance.

- A) Category of substance:

- 1. Substance: characteristic of independence.

- 2. Substance: characteristic of recognizability.

- B) Non-Substantial Categories: Accidental.

So Aristotle advocates the following theses:

- Only individual things (first substances) are independent and therefore ontologically primary.

- All properties depend on the individual things. There are no independent, non-exemplified archetypes.

- In addition to contingent, accidental properties (such as 'white') there are necessary, essential properties (such as 'human') that indicate what an individual thing is.

The substance theory of metaphysics

For Plato, the consequence of his conception of ideas is the assumption that, in the proper, independent sense, only unchangeable ideas exist; the individual things exist only in dependence on the ideas. Aristotle criticizes this ontological consequence extensively in metaphysics. He considers it contradicting that the followers of the theory of ideas on the one hand delimit ideas from the sense objects by assigning them the characteristic of generality and thus undifferentiation, and on the other hand at the same time assume a separate existence for each individual idea; as a result, the ideas themselves would become individual things, which would be incompatible with their definition of universality (Met. XIII 9, 1086a32–34).

In metaphysics , Aristotle, as part of his plan to investigate beings as beings, takes the view that all beings are either a substance or are related to one ( Metaphysics IV 2). In the categories he formulated a criterion for substances and gave examples (Socrates) for them. In metaphysics , he once again addresses substance in order to look for the principles and causes of a substance, a concrete individual thing. Here he asks: What makes Socrates a substance? Substance is here a two-digit predicate (substance of X), so that the question can be formulated as follows: What is the substance-X of a substance? The distinction between form and matter , which is not present in the categories , plays a decisive role.

Aristotle seems to search for substance-X primarily with the help of two criteria , which in the theory of categories are divided between the first and the second substance:

- (i) independent existence or subject for everything else, but not being a predicate itself (individual being = first substance);

- (ii) To be the object of definition, to guarantee recognizability, i.e. to the question 'What is X?' to answer (general essence = second substance).

Criterion (ii) is met more precisely in that Aristotle defines the essence as substance-X. By essence he means what ontologically corresponds to a definition (Met. VII 4; 5, 1031a12; VIII 1, 1042a17). The essence describes the necessary properties without which an individual thing would cease to be one and the same thing. If one asks: What is the reason that this portion of matter is Socrates? Aristotle's answer is: The essence of Socrates, which is neither a further component besides the material components (then a further structural principle would be needed to explain how it is united with the material components) or something from material components (then one would have to explain how the being itself is composed).

Aristotle determines the form (eidos) of a single thing as its essence and thus as substance-X. With form he means less the external shape than the structure: the form

- dwells in the single thing,

- causes

- in living beings the emergence of a specimen of the same species (Met. VII 8, 1033b30–2)

- with artefacts (e.g. house) as a formal cause (blueprint) (Met. VII 9, 1034a24) in the spirit of the producer (Met. VII 7, 1032b23) (architect) the emergence of the individual thing.

- precedes the emergence of a single thing composed of form and matter and arises and does not change and thus (in natural species) creates a continuity of forms that is eternal for Aristotle (Met.VII 8, 1033b18)

- is the cause, explanation of the essential properties and abilities of an individual thing (for example, the form of a person is the soul (Met. VII 10, 1035b15), which is made up of abilities such as the ability to nourish, perceive, and think among others ( An. II 2, 413b11– 13)).

The fact that the form as substance X also has to meet the mentioned criterion (ii) of being independent, and that this is partly understood as a criterion for something individual, is one of many aspects in the following central interpretative controversy: Does Aristotle summarize the form (A. ) as something general or (B) as something (the respective individual thing) individual ? Formulated as a problem: How can the form, the eidos, be both the form of a single thing and the object of knowledge? In favor of (A), Aristotle assumes in several places that the substance-X and thus the form can be defined (Met.VII 13) and for him (as for Plato) this only applies to general information (VII 11, 1036a ; VII 15, 1039b31-1040a2). In favor of (B), on the other hand, is the fact that Aristotle seems categorically to take the unplatonic position: No general can be substance X (Met. VII 13). According to (B), Socrates and Callias have two qualitatively different forms. It should then be possible to define super-individual aspects of these two forms that are to be separated. Interpretation (A), on the other hand, solves the dilemma, for example, by interpreting and thus defusing the statement No general is substance-X as nothing generally predictable is substance-X . The form is not predicted in a conventional way (like the type of 'man' from 'Socrates' in the categories ) and is therefore not general in the problematic sense. Rather, the form is 'predicted' by indefinite matter in a way that constitutes an individual object.

Act and potency

The relationship between form and matter, which is important for ontology, is explained in more detail by another pair of terms: act (energeia, entelecheia) and potency (dynamis).

The later ontological meaning of potency or ability is important for the distinction between form and matter . Here potentiality is a state that is opposed to another state - actuality - in that an object is reality according to F or the ability, possibility according to F. So a boy is possibly a man, an uneducated person is possibly an educated person (Met. IX 6).

This relationship between actuality and potentiality (described here diachronically ) forms the basis for the relationship between form and matter (which can also be understood synchronously ), because form and matter are aspects of an individual thing, not its parts. They are linked to one another in the relationship between actuality and potentiality and thus (first) constitute the individual thing. The matter of an individual thing is therefore exactly that potential that the form of the individual thing and the individual thing itself are actual (Met. VIII 1, 1042a27 f .; VIII 6, 1045a23–33; b17–19). On the one hand (viewed diachronically) a certain portion of bronze is potentially a ball as well as a statue. On the other hand, however (synchronously as a constituent aspect) the bronze on a statue is potentially exactly what the statue and its shape actually are. The bronze of the statue is a constituent of the statue, but is not identical to it. And so flesh and bones are also potentially that which Socrates or his form (the configuration and capabilities of his material components typical for a person, → psychology ) are actual.

Just like form versus matter, for Aristotle, actuality is also primary versus potentiality (Met. IX 8, 1049b4-5). Among other things, it is known to be primary. One can only state a fortune if one refers to the reality to which it is a fortune. The ability to see, for example, can only be determined by referring to the activity of “seeing” (Met. IX 8, 1049b12–17). Furthermore, the actuality in the decisive sense is also earlier in time than the potentiality, because a person arises through a person who is actual person (Met. IX 8, 1049b17-27).

theology

In the run-up to his theology, Aristotle differentiates between three possible substances: (i) perceptible perishable, (ii) eternal perceptible to the senses, and (iii) eternal and immutable that cannot be perceived by the senses (Met. XII 1, 1069a30-1069b2). (i) are the concrete individual things (of the sublunar sphere), (ii) the eternal, moving heavenly bodies , (iii) proves to be the self-immobile origin of all movement.

Aristotle argues for a divine mover, stating that if all substances were perishable, everything would have to be perishable, but time and change itself are necessarily imperishable (Phys. VIII 1, 251a8–252b6; Met. XII 6, 1071b6 -10). According to Aristotle, the only change that can exist forever is circular motion (Phys. VIII 8-10; Met. XII 6,1071b11). The corresponding observable circular movement of the fixed stars must therefore have an eternal and immaterial substance as its cause (Met. XII 8, 1073b17–32). If the essence of this substance contained potentiality, the movement could be interrupted. Therefore it must be pure topicality, activity (Met. XII, 1071b12–22). As a final principle, this mover itself must be motionless.

According to Aristotle, the motionless mover moves “like a loved one”, namely as a goal (Met. XII 7, 1072b3), because what is desired, what is thought and especially what is loved can move without being moved (Met. XII 7, 1072a26). His activity is the most pleasurable and beautiful. Since he is immaterial reason (nous) and his activity consists in thinking of the best object, he thinks himself: the "thinking of thinking" (noêsis noêseôs) (Met. XII 9, 1074b34 f.). Since only living things can think, it must also be alive. Aristotle identifies the motionless mover with God (Met. XII 7, 1072b23 ff.).

The motionless mover moves all of nature. The fixed star sphere moves because it imitates perfection with the circular movement. The other celestial bodies are moved through the sphere of fixed stars. Living beings have a share in eternity because they exist forever through reproduction ( GA II 1, 731b31–732a1).

biology

Position of biology

Aristotle occupies an important place not only in the history of philosophy, but also in the history of the natural sciences. A large part of his surviving writings is natural science, of which by far the most important and extensive are the biological writings, which comprise almost a third of the surviving complete works. Probably in a division of labor, botany was worked on by his closest colleague Theophrastus , medicine by his pupil Menon.

Aristotle compares the study of imperishable substances ( God and heavenly bodies ) and perishable substances (living beings). Both research areas have their charm. It is true that the immortal substances, the highest objects of knowledge, give the greatest pleasure, but the knowledge of living beings is easier to attain because they are closer to us. He emphasizes the value of researching lower animals and points out that these also show something natural and beautiful, which is not exhausted in its dismantled components, but only emerges through the activities and the interaction of the parts ( PA I 5, 645a21– 645b1).

Aristotle as an empirical researcher

Aristotle himself carried out empirical research , but presumably did not carry out experiments in the sense of a methodical test arrangement , which was first introduced in modern natural science.

What is certain is that he carried out dissections himself. The closest thing to an experiment is the repeated examination of fertilized hen's eggs at fixed time intervals, with the aim of observing the order in which the organs arise (GA VI 3, 561a6-562a20). However, in its real domain - descriptive zoology - experiments are not the essential research tool. In addition to his own observations and a few text sources, he also relied on information from relevant professionals such as fishermen, beekeepers, hunters and shepherds. He had the content of his text sources checked empirically, but also accepted uncritically foreign errors. A lost work probably consisted largely of drawings and diagrams of animals.

Methodology of Biology: Separation of Facts and Causes

Due to the long prevailing interpretation model of the philosophy of science of Aristotle and the neglect of biological writings, it was previously assumed that he did not apply this theory to biology. In contrast, it is now accepted that his approach to biology was influenced by his philosophy of science , although the scope and degree are controversial.

Collections of facts

Aristotle has not given a description of his scientific approach. In addition to the general theory of science, only texts that represent an end product of scientific research have survived. The biological scriptures are arranged in a specific order that corresponds to the procedure.