Giovanni Battista Benedetti

Giovanni Battista Benedetti (born August 14, 1530 in Venice , † January 20, 1590 in Turin ) was a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, architect and philosopher. He is known as a forerunner of Galileo Galilei in the theory of free fall and in Aristotle's critique of mechanics .

Life

Benedetti, who came from better Venetian circles, was taught by his father, who was himself very interested in philosophy and the natural sciences and of Spanish origin. Nicolo Tartaglia instructed him from 1546 to 1548 in the first four books of the elements of Euclid . Everything else he had examined with his own effort and work, because nothing is difficult for the inquisitive ( Moritz Cantor : Vorl. Über die Geschichte der Mathematik , vol. 2, chap. 67, p. 566). He didn't go to university.

In 1558 Benedetti became court scholar and mathematician of Ottavio Farnese , Duke of Parma . During this time he supervised public construction works, carried out astronomical observations and astrological work and calculated, among other things, sundials (3). During this time he was only paid sporadically, but was able to bridge that because he was inherently wealthy. In 1559/60 he gave lectures on Aristotle in Rome.

In 1567 he accepted an invitation from the Duke of Savoy , Emanuel Philibert, to Turin where he lived until his death. His reputation as a mathematician was now cemented by his writings. In Turin he also gave lectures at the university and was considered a good teacher in mathematics (but he never described himself as a professor, which actually required a university degree). The Duke was very interested in promoting science and expanding the infrastructure. Benedetti was his advisor and also employed as an engineer.

He was married - a daughter was born in 1554.

Services

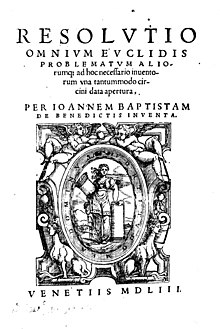

Benedetti's first publication (1) from 1553 deals with elementary geometric constructions with the restriction of a fixed circle opening (practically a rusty circle). Although this was a popular topic among Italian mathematicians ( Ferrari , Gerolamo Cardano , Tartaglia ) at the time and had been solved before him, Benedetti's work is characterized by more elegance and comprehensibility. In two letters Benedetti linked the consonance and dissonance of two tones with the frequency of air vibrations for the first time. He constructed wells, dealt with a calendar reform (4), took care of fortifications and showed himself to be a forerunner of Galileo in his views (2) on the speed of fall of different bodies .

Benedetti had already published his thoughts on free fall in the form of a letter to the Spanish Dominican Gabriel de Guzman (Abbot of Pontelungo ), with whom he had discussed in Venice, in his resolution of 1553 in order to anticipate priority claims. He presented them in more detail in his demonstration of 1554.

Benedetti here refuted the false hypothesis of Aristotle , according to which a body must fall faster the heavier it is, with a simple thought experiment : two falling balls connected If a (massless) rod, nothing changes in the rate of fall , although the bulk of the Whole body enlarges.

Benedetti's thought experiment on free fall also appears in the Discorsi (published 1638) by Galileo and was often ascribed to him. Galileo does not mention Benedetti in his work, but knew Benedetti's work almost certainly through the philosopher Jacopo Mazzoni , with whom he discussed mechanics in Pisa around 1590 and who demonstrably dealt with Benedetti in his writings. Benedetti was influential for Galileo, not least as a vehement critic of Aristotle's mechanics, as, for example, Alexandre Koyré emphasized. On the other hand, Galileo's early De motu after Stillman Drake shows no particular influence from Benedetti, which could not be attributed to other sources such as the medieval impetus theory ( Jean Buridan ).

Benedetti also considered the effects of friction in free fall, which lead to the same falling speeds of different weights only being achieved in a vacuum. He correctly assumed that the friction depended on the surface area.

In 1585 he published an anthology of various works, including on perspective and music and geometry (such as isoperimetric figures, spherical triangles, regular polyhedra, a commentary on the fifth book by Euclid). He showed, for example, that Albrecht Dürer's construction of the Pentagon with a ruler and compass with a fixed opening is not exact. There is also another critique of the mechanics of Aristotle and that of Tartaglia. Benedetti was also one of the first to write explicitly that a body in circular motion moves on a straight line tangential to the circle after the constraining forces have been removed. He also repeated his arguments about free fall and found correct that a constant acceleration is at work. In contrast to Galileo, however, he gave no mathematical formulation of the acceleration. Benedetti also dealt with hydraulics and correctly predicted that winds are due to different air densities, generated by different warming by the sun, and found a qualitatively correct explanation for clouds.

Considerations on music can also be found in his book from 1585, which he made in a letter to the choir master in Parma Cipriano da Rore in 1561/62. He attributed the consonance and dissonance of tones to the superimposition of air waves that the musical instruments generate. He had an influence on later discussions with Isaac Beeckman and Marin Mersenne .

Another section of the work gave a representation of perspective (De rationibus operationum perspectivae), using three-dimensional constructions and falling back on Euclid 's optics. He also corrects Dürer's mistakes.

In his last book he also predicted his death in 1592 from astrological calculations, which he corrected on his deathbed in 1590 and attributed to an error in the initial data.

Works

- (1) De resolutione omnium Euclidis problematum aliorumque una tantummodo circuli data apertura, Venice 1553

- (2) Demonstratio proportionum motuum localium, Venice 1554

- (3) De gnomonum umbrarumque solarium usu liber, 1573 (about sundials)

- (4) De temporum emendatione opinio, Augustae Taurinorum, 1578 (calendar)

- Consideratione d'intorno al discorso della grandezza della terra e dell 'acqua di Berga, Turin 1579 (his contribution to a contemporary controversy about the relative volumes of water and earth; Antonio Berga was philosophy professor in Turin from 1569)

- Diversarum speculationum mathematicorum et physicarum liber, Turin 1585 (see here )

A collection of letters and manuscripts from Benedetti in the National Library in Turin (and the only known portrait) were destroyed by fire in 1904.

literature

- Stillman Drake : Benedetti, Giovanni Battista . In: Charles Coulston Gillispie (Ed.): Dictionary of Scientific Biography . tape 1 : Pierre Abailard - LS Berg . Charles Scribner's Sons, New York 1970, p. 604-609 .

- Giovanni Bordiga Giovanni Battista Benedetti, filosofo e matematico veneziano del secolo XVI , in Atti del Reale Istituto veneto di scienze, lettere ed arti, Volume 85, 1925/26, Part 2, pp. 585-754.

- Drake, Dabkin Mechanics in sixteenth century italy , University of Wisconsin Press 1969 (with English translation of excerpts from Benedetti's work)

- Antonio Manna (Ed.) Cultura, Scienze e Tecniche nella Venezia del Cinquecento , Istituto Veneto de Scienze, Lettere ed Arti 1987 (International Congress on Benedetti)

Web links

- Works by and about Giovanni Battista Benedetti in the German Digital Library

- John J. O'Connor, Edmund F. Robertson : Giovanni Battista Benedetti. In: MacTutor History of Mathematics archive .

- The Archimedes Project

- Benedetti in the Galilei Project

- Cantor, Moritz: Lectures on the History of Mathematics 1550-1600

Individual evidence

- ↑ Luca Guarico described him as a physicus , which, after Stillman Drake, could also be called a doctor

- ^ Stillman Drake in Dictionary of Scientific Biography

- ↑ The resolution and the demonstration are dedicated to him.

- ↑ He was forewarned by the fate of Tartaglia. In fact, a certain Jean Taisner plagiarized his work on free fall and that of Pierre de Maricourt on magnetism with a book published in Cologne in 1562 . The work was translated into English in 1578 and influenced scientists like Simon Stevin , who incorrectly attributed this theory of free fall to Taisner rather than Benedetti - Stevin also undertook early fall experiments in 1586. Benedetti expresses his anger at the plagiarism in 1573 in his book on sundials.

- ↑ Machemer (Ed.) Cambridge Companion to Galilei , Cambridge University Press 2006, p. 40. Stillman Drake in Dictionary of Scientific Biography - he is also not mentioned in the letters from and to Galilei. With Kepler there is only one mention that is kept very general.

- ↑ Etudes Galiléennes, 1939

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Benedetti, Giovanni Battista |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian mathematician, physicist and philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 14, 1530 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Venice |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 20, 1590 |

| Place of death | Turin |