Simon Stevin

Simon Stevin (Latinized Simon Stevinus * 1548 / 49 in Bruges ( Flanders ), † 1620 ) was a Flemish mathematician , physicist and engineer . He has worked theoretically and practically in many areas of the sciences, but he is best known for his translations of many mathematical terms into the Dutch language. He also proposed a purely decimal system of measurement as early as 1585 .

resume

Very little is known of Stevin's circumstances; the exact day of his birth and the day (in spring) and the place of his death ( The Hague or Leiden ) are equally unknown. He was the illegitimate son of Antheunis Stevin and Cathelijen van de Poort, wealthy citizens from Bruges. A few references in his work indicate that he started as a commercial clerk (accountant) in Bruges and Antwerp , that between 1571 and 1577 he traveled to Poland, Denmark, Norway and other countries in Northern Europe, and that from 1581 he was in Leiden, where he studied at the university from 1583. It is not known about his religious background and whether he fled there before persecution in the Spanish Netherlands. He was acquainted with Prince Moritz of Orange , who sought his advice on many occasions and made him an employee and director of the so-called Waterstaat (the government authority for water affairs) and later (from 1604) quartermaster general of the army. He was also administrator of the property of Moritz von Orange, worked for him as an engineer and opened for him an engineering school in Leiden.

In 1610 he married Catherine Cray, with whom he had four children. Hendrick's son was also a gifted scientist and published some of Stevin's manuscripts.

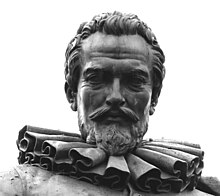

In Bruges there is a Simon Stevin Square with a statue of him made by Eugène Simonis in 1846 .

The lunar crater Stevinus and the asteroid (2831) Stevin are named after him.

Scientific achievements

Discoveries and inventions: the sailing cart, windmills

His merits are many. His contemporaries were particularly impressed by his invention of a craft with sails , a small model of which was kept in Scheveningen until 1802. The vehicle had been lost long before, but it is known that Stevin used it around the year 1600 with Prince Moritz of Orange and 26 others on the coast of Scheveningen and Petten, that it was propelled by the wind alone and that it reached a speed which exceeded that of horses.

Stevin also improved the windmills used to drain the land and there are a number of patents from Stevin that made him wealthy. He also wrote a treatise on windmills.

Philosophy of science

Another idea by Stevin, for which Hugo Grotius gave him great approval, was his theory of a bygone age of wisdom. The goal to be striven for is the production of a second age of wisdom in which humanity will rediscover all of its previous knowledge. - His compatriots took pride in the fact that he wrote in their own dialect, which he considered suitable for a universal language, because no other dialect had so many monosyllabic stems.

Geometry and physics

Stevin was the first to show how to model regular and irregular polyhedra by sketching them in the plane. Stevin also distinguished the stable from the unstable equilibrium . With Stevin's thought experiment, he proved the law of equilibrium on an inclined plane .

Before Pierre de Varignon he showed the dissolution of forces, which had not been recognized before, although it is actually a simple consequence of the law of their composition ( parallelogram of forces and virtual displacement ).

Stevin discovered the hydrostatic paradox , according to which the pressure at the bottom of a liquid is independent of the shape of the container and only depends on the water level above the bottom.

He also gave the amount of pressure on any part of the wall of a container and explained why liquids in communicating tubes have an even water level.

Stevin was an unconditional supporter of the Copernican system, which he also presented in his book De Hemelloop . In 1590 he put forward the theory that the tides can be explained by the attraction of the moon .

In 1586 he demonstrated that two objects with different weights fall to the ground at the same speed , which is usually considered a knowledge of Galileo Galilei , but was also recognized by physicists before Galileo (in the case of Stevin, the influence came indirectly through Giovanni Battista Benedetti ).

He also convincingly demonstrated that a perpetual motion machine cannot exist.

Fortresses

Stevin had been in the service of Prince Moritz of Orange since about 1593 . In 1599 Stevin was commissioned to design an "instructie" for the establishment of an engineering school, which was to be connected to the University of Leiden and which was then opened. For this he also wrote a textbook (Stercktenbouwinge) in 1594, which was generally used by the Dutch fortress engineers. His advocacy of the teaching of the science of forts at universities and the existence of such lectures in Leiden have led to the impression that he himself filled this chair, but this is a mistake, for Stevin never had any direct relationship with the university, although he was in Leiden lived. He was often adviser on fortifications when a whole ring of fortifications was built in the Netherlands under Moritz von Oranien, but the actual engineering work was carried out by others (such as Adriaan Anthonisz , David van Orliens , Johan van Rijswijck , Johan van Valckenburgh , Samuel Marolois ).

Stevin was apparently the first to make it an axiom that fortresses could only be defended with artillery. Before that, the defense mostly relied on small firearms.

He was the inventor of defense through a system of locks, which was of paramount importance to the Netherlands.

accounting

The double-entry bookkeeping could Stevin as a clerk have virtually met in Antwerp or by the works of Italian authors like Luca Pacioli and Gerolamo Cardano . In any case, he was the first to recommend the use of impersonal accounts in the national budget. He practiced this for Prince Moritz and recommended it to the French statesman Sully .

Decimal numbers

Simon Stevin's greatest success was undoubtedly a small textbook entitled De Thiende ("The Tenth"), which was first published in Dutch in 1585. De Thiende is likely to have enjoyed great popularity after it was published; by 1650 there were two Dutch, three French and two English versions.

The title page of the textbook bears the inscription: “DE THIENDE which teaches you to do all the calculations that people need with unbelievable ease using numbers without fractions. Described by Simon Stevin from Bruges. At Leyden at Christoffel Plantijn. MD LXXXV. "The actual book begins with a preface in which Stevin" [wishes] astronomers, land knives, cloth knives, wine knives, stereometers in general, mint masters and all merchants [...] luck. "The main part contains a summary which can be seen that “De Thiende” is made up of two parts. The first part explains the idea behind the new number display, the second explains how to calculate with the new numbers using the four basic arithmetic operations and two notes. The latter contain hints on how to deal with the case that the dividend is smaller than the divisor when dividing and on the extraction of the square root.

Decimals had been used to extract square roots some 500 years before his time, but none before Stevin introduced them into everyday use. And he was so aware of the importance of his innovation that he declared that the general introduction of decimal coins, measures and weights was only a matter of time, which he was right.

His way of writing the decimal places is very unwieldy. The point that separates the integers from the fractions of ten seems to be an invention of Bartholomäus Pitiscus , in whose trigonometric tables it appeared in 1612. The point was also accepted by John Napier in his log papers in 1614 and 1619.

Stevin wrote small circles around the exponents of the various powers of the tenths. The fact that Stevin used these circled numbers to represent exponents is obvious because he used the same symbols for the powers of algebraic quantities. He didn't even avoid broken exponents, and the only thing he didn't know was negative exponents.

Stevin also wrote on other scientific subjects: optics, geography, astronomy, and many of his writings were translated into Latin by W. Snellius ( Willebrord Snell ). There are two complete French editions of his works, both printed in Leiden, one from 1608 and the other from 1634.

Music theory

In his work Van de Spiegheling der Singconst , Stevin formulated a polemical antithesis against Euclid's theory of the tone system, which claimed that many musical intervals such as octaves, fifths, fourths and whole tones were indivisible due to their irrationality. Stevin declared the irrational to be rational because he was able to use his decimal numbers to define the roots of the proportions of said intervals. In his tone system theory, he started from arbitrary roots of the octave proportion 2 and defined the twelve-step tone tuning via powers of the twelfth root of 2, which he then approximated well using decimal fractions. This corresponds to a conversion of the additive intervals according to Aristoxenos into the multiplicative proportions with an exponential function to the base 2. He rejected the usual interpretation as a tempered tone system because he did not see the Pythagorean mood of the consonances as true, but rather regarded its root values as true values.

Word creations (neologisms)

Stevin thought Dutch was an excellent language for scientific writing, and he translated many mathematical expressions into Dutch. As a result, Dutch is the only Western European language that contains many mathematical expressions that do not derive from Latin (or Greek). For example, “wiskunde” is the word for mathematics in Dutch.

He had an eye for the importance of the language of science being the same as the language of craftsmen, and this is shown in the dedication of his book De Thiende ("The Tenth"): 'Simon Stevin wishes the stargazers, surveyors, carpet surveyors, Good luck to body surveyors in general, coin surveyors and traders. ' Later in the book he writes: “[this text] teaches us all the calculations the people need without using fractions. All operations can be reduced to adding, subtracting, multiplying and dividing with integers. "

The words he invented evolved: 'aftrekken' (to peel off ) and 'delen' (to share ) stayed the same, but over time 'menigvuldigen' ( multiply ) became 'mermenigvuldigen' (the added 'ver' has none Meaning), and 'gauging' ( adding ) became 'optellen'. The word 'zomenigmaal' (literally 'so many times') has become the less poetic quotient in modern Dutch .

Fonts

Among other works he published:

- Boards of Interest (Zinstafeln) 1582

- Problemata geometrica 1583

- De Thiende (The Tenth) 1585 (this is how decimal numbers were introduced in Europe)

- La pratique d'arithmétique 1585

- L'arithmétique in 1585 (a general treatment of algebraic equations was presented here)

- De Beghinselen der Weegconst 1586

- De Beghinselen des Waterweight (principles of water weight) 1586 (on the subject of hydrostatics )

- Vita Politica. Het Burgherlick leven (Civil life) 1590

- De Sterktenbouwing (The Construction of Fortifications ) 1594

- De Havenvinding (Positioning) 1599

- De Hemelloop 1608 (The Skywalk)

- Wiskonstighe Ghedachtenissen (Mathematical Memoirs). This includes earlier works such as De Driehouckhandel ( trigonometry ), De Meetdaet (practice of surveying ), and De Deursehenhe ( perspective )

- Latin translation titled Hypomnemata mathematica by Willebrord van Roijen Snell (Snellius)

- Castrametatio, dat is legermeting and Nieuwe Maniere van Stercktebou door Spilsluysen (New way of building locks ) 1617

- De Spiegheling der Singconst (Theory of the Art of Singing)

- Œuvres mathématiques ..., Leyde, 1634 [1]

- Charles van den Heuvel De Huysbou. A reconstruction of an unfinished treatise on architecture, town planning and civil engineering by Simon Stevin , History of Science and Scholarship in the Netherlands, Volume 7, Royal Dutch Academy of Sciences 2007

Stevin's Collected Works were edited by Ernst Crone, EJ Dijksterhuis, RJ Forbes, MGJ Minnaert, A. Pannekoek : The Principal Works of Simon Stevin , Amsterdam: Swets & Zeitlinger, 1955–1966 (Volume 1 Mechanics, Volume 2a, 2b Mathematics , 3 astronomy / navigation, 4 martial arts, 5 engineering- music- civil life) online

literature

-

Eduard Jan Dijksterhuis Simon Stevin , 's-Gravenhage 1943 (Dutch)

- abridged English edition Simon Stevin. Science in the Netherlands around 1600 , The Hague, Martinus Nijhoff 1970

- Marcel Minnaert : Stevin, Simon . In: Charles Coulston Gillispie (Ed.): Dictionary of Scientific Biography . tape 13 : Hermann Staudinger - Giuseppe Veronese . Charles Scribner's Sons, New York 1976, p. 47-51 .

- Dirk Struik The land of Stevin and Huygens. A sketch of science and technology in the dutch republic during the golden age , Reidel 1981 (Chapter 5 on Stevin)

- K. van Berkel The legacy of Stevin. A chronological narrative , Leiden 1999

- Jozef T. Devreese, Guido Vanden Berghe Magic is no magic. The wonderful world of Simon Stevin , WIT Press, Southampton (Boston), 2008

- Rolf Grabow Simon Stevin , Teubner, Leipzig 1985

- Bergmann, Schaefer - Textbook of Experimental Physics - Volume I - Mechanics, Acoustics, Warmth - 9th Edition - Chapter II, 61f

- Krafft, Fritz (Ed.): “Advance into the Unknown” - Lexicon of great natural scientists; Wiley-VCH 1999, ISBN 3-527-29656-5 , 395f

- Moritz Cantor : Stevin, Simon . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 36, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1893, pp. 158-160.

- Henri Bosmans Simon Stevin , Biographie Nationale 1924, pdf

- Karl-Eugen Kurrer : The History of the Theory of Structures. Searching for Equilibrium , Ernst & Sohn 2018, p. 29f and p. 1064 (biography), ISBN 978-3-433-03229-9 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Minnaert, Dictionary of Scientific Biography, gives the place of death The Hague, March 1620

- ↑ Frederick Stokhuyzen The Dutch Windmill , History section ( Memento of the original from July 5, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Jürgen Soenke: Johan van Rijswijck and Johan van Valckenburgh - The fortification of German cities and residences 1600–1625 by Dutch engineering officers. Announcements of the Minden History Society, year 46 (1974), pp. 9–39.

- ↑ a b c d e f Helmuth Gericke, Kurt Vogel: De Thiende by Simon Stevin. The first textbook on decimal fractions based on the Dutch and French editions of 1585 . In: Ostwald's classic of the exact sciences . tape 1 . Academic Publishing Company Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main 1965.

- ^ José Ferreirós: Mathematical Knowledge and the Interplay of Practices . Oxford 2016, p. 211 .

- ↑ Hensk JM Bos: Simon Stevin, mathématicien . In: Raphaël De Smedt (ed.): Simon Stevin 1548–1620. L'émergence de la nouvelle science . Turnhout 2004, p. 51 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Simon Stevin in the catalog of the German National Library

- Publications by and about Simon Stevin in VD 17 .

- Consortium of European Research Libraries : Simon Stevin Catalog of Works

- Detailed web pages on De Thiende and his translation into English, French and Swedish, as well as scans of these books (Dutch) ( Memento of January 13, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- Text of the Catholic Encyclopedia

- John J. O'Connor, Edmund F. Robertson : Simon Stevin. In: MacTutor History of Mathematics archive .

- Author: Hulsius, Levinus & Palthenius, Hartmann, publisher, administrator: Dresden, Sächsische Landesbibliothek - State and University Library Dresden (SLUB), signature / inventory no .: Milit.B.199 - Engraving by Stevin's sailing wagon

- Video of Simon Stevin's Perlenkette (Beads Chain), a perpetual motion machine

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Stevin, Simon |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Dutch - Belgian mathematician , physicist and engineer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1548 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Bruges ( Flanders ) |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1620 |