music

Music is an art form whose works consist of organized sound events . In order to generate them, acoustic material , such as tones , sounds and noises , is arranged within the range that can be heard by humans . From the supply of a sound system are scales formed. Their tones can appear in different volume or intensity ( dynamics ), tone color , pitch and tone duration . Melodies are created from the sequence of tones and, if necessary, pauses in a fixed time frame ( rhythm , meter and tempo , possibly embedded in bars ). The harmony of several tones ( chords ), each with a different pitch, gives rise to polyphony , and the relationship between the tones creates harmony . The conceptual capture, systematic representation of the connections and their interpretation is provided by music theory , teaching and learning music is dealt with in music education , and questions about musical design are mainly concerned with music aesthetics . Music is a cultural asset and an object of musicology .

Historical development

Prehistory and early history

The earliest known instruments that were specially made for making music are the bone flutes from Geißenklösterle on the Swabian Alb , which are exhibited in the Prehistoric Museum in Blaubeuren . They are around 35,000 years old. However, most anthropologists and evolutionary psychologists agree that music was part of everyday life for humans and their ancestors long before that. It is unclear why humans acquired musical abilities in the course of their evolution.

Early cultures without writing

The birdsong has features that are mimetically imitated by humans , tone and tone group repetitions, tone series, motifs and main tones as approaches to a scale formation . Even in non-scripted cultures there are melody types that consist of constant repetitions of the same motif, consisting of a few tones within a third to fourth space. This construction feature is still preserved in Gregorian chant , in the sequences of the high Middle Ages and in numerous European folk songs with stanzas , e.g. B. in the Schnadahüpfl .

The rhythm is seldom tied to timing schemes or changes its classifications and accentuation frequently by adapting to the melodic phrasing. However, it is not shapeless, but rather polyrhythmic like traditional African music , which layers rhythmic patterns , especially when singing with accompanying idiophones . The offbeat later characteristic of jazz can also be found, i. H. the emphasis on the weak beats.

High cultures

For a period of millennia, the animistic and shamanistic non- scripted cultures practiced rites to conjure up spirits. Part of their ritual ceremonies were - and still are - drums , singing and dancing.

The ancient oriental writing cultures in Mesopotamia began in the 4th millennium BC. With the Sumerians . They invented the first multi-string chordophone, the lyre , which in the following centuries became a harp with four to ten strings and a sound box .

In ancient Egypt from around 2700 BC. The range of instruments was expanded to include the bow harp. During this time secular music and pure instrumental music also emerged.

There are only guesses about the beginnings of Indian music in the third millennium BC. She may have taken inspiration from Mesopotamian and Egyptian cultures. Due to the immigration of the Aryans around 1500 BC Western influences came to India.

China already had fully developed music in ancient times. The most important suggestions came mainly from Mesopotamia. Own inventions were a scale system, pentatonic scales and a fixed pitch tuning. The compositions were unanimous and homophonic .

Antiquity

For a long time since its creation, music has been part of ritual and cult , but possibly also in the normal everyday life of the early high cultures , where it only later became an autonomous art . Just as many cultures do not have their own term for music up to the present day , which they understand as a unity of dance , cult and language, the μουσική, adopted from Greek antiquity , describes a unity of poetry , dance and music until the 4th century BC from which the latter was resolved by narrowing the terms. Nevertheless, she has retained her close relationship with poetry and dance, each of which has emerged as defining moments in the course of music history.

Middle Ages and Modern Times

While music in the Middle Ages was strongly characterized by numerical orders, under the influence of which it, as Ars musica, together with arithmetic , geometry and astronomy, formed the logical- argumentative quadrivium within the Artes liberales , the creative achievement of the composer was first acquired through practice in the Renaissance manual mastery preferred. At this time, instrumental works emerged in art music that tried to convey meaning without language or song. The prevailing idea of the 16th to the 18th century, already had Aristotelian poetics described mimesis , the imitation of external nature to the tone-painting and the inner nature of man in the affective representation .

With the beginning of rationalism in the 17th century, the creative aspect prevailed. In Romanticism , the personal-subjective experience and feeling and its metaphysical meaning were in the foreground. As extensions of musical expression and positions with regard to the ability of music to communicate extra-musical content, terms such as absolute music , program music and symphonic poetry emerged , around which an irreconcilable discussion broke out between the warring parties. At the same time was popular music more and more independent and grown since the end of the 19th century under the influence, among others, the African-American folk music to a separate branch that eventually jazz, pop and rock music spawned a variety each highly differentiated single genre. At the turn of the 20th century, music history research on the one hand met with greater interest and, on the other hand, sound recording allowed the technical reproduction of music, this gained in all its known historical, social and ethnic forms a presence and availability that continues to this day, thanks to mass media , recently increased by the digital revolution . This and the stylistic pluralism of modernism that began around 1910 , during which New Music reacted to changed social functions or only created it itself, justified a blurring of the previously traditional boundaries between genres, styles and categories of light and serious music, for example in emerging forms such as third stream , digital hardcore , crossover and world music . The musical thinking of postmodernism tends, in turn, to an aesthetic universalism that includes the extra-musical - multimedia or in the sense of a total work of art - or to new models of thought, as they have grown in cultures and philosophies outside the West.

Concept and concept history

Like the Latin musica, the word “music” is derived from the Greek μουσική τέχνη ( mousikḗ téchnē : “art of the muses , musical art , muse art”, especially “musical art, music”). The term music has seen several changes in meaning over the past millennia. From the art unit μουσική broke away in the 4th century BC. The musica , whose conception was initially that of a theory-capable, mathematically determined science. Regardless of the rest of the development towards fine art, this persisted into the 17th, and in Protestant circles into the 18th century. Until the decisive change in meaning that introduced today's concept of music, the term musica is not to be understood solely as “music theory”; its variety of definitions only arises from the perception of individual epochs, their classifications and differentiations.

Word origin and word history

The ancient Greek adjective mousikós (-ḗ, -ón) (μουσικός (-ή, -όν), from moûsa μοῦσα 'muse') first appeared in the female form in 476 BC in Pindar's first Olympic ode . The adjective mousikós (μουσικός) flowed as musicus (-a, -um) , concerning the music, musically; also: concerning poetry, poetic ', musicus (-i, m.) , musician, sound artist; also: Dichter ', musica (-ae, f.) and musice (-es, f.) ' Musenkunst, Musik (in the sense of the ancients, with the epitome of poetry) 'and musicalis (-e) ' musical 'in Latin Language a.

The Greek μουσική and the Latin musica finally entered the theoretical literature as technical terms . From there, almost all European languages and Arabic took over the term in different spellings and accents . There are only a few languages of their own, for example hudba in Czech and Slovak , glazba in Croatian , and Chinese yīnyuè (音乐), Korean ŭmak / eumak (음악), Japanese Ongaku (音 楽), Anglo-Saxon swēgcræft , Icelandic tónlist, Dutch toonkunst (besides muziek ), Danish tonekunst (next music ), norwegian tonekunst (next musikk ), swedish tonkonst (next music ). In the German language initially only the basic word appeared, Old High German mûseke and Middle High German mûsik . From the 15th century, derivatives such as musician or making music were formed. It was not until the 17th and 18th centuries that the accent changed under the influence of French musique on the second syllable, as it is still valid today in standard German .

History of definition

The music aesthetician Eduard Hanslick defined music as “a language that we speak and understand but are unable to translate”. The question of what music is or not is is as old as thinking about music itself. Despite the numerous historical attempts to arrive at a general and fundamental concept of music, there was and is no single definition. The previous definitions each focused on one component of the music phenomenon. The history of definitions is marked by many contradictions: music as a rational, numerical science, music as emotional art, music in the Apollonian or Dionysian understanding, music as pure theory or pure practice - or as a unity of both components.

Antiquity

The music literature of antiquity produced numerous attempts at definition, which, however, are characterized by the fact that they put the musical material, the scale , and its mathematical foundations in the center and understood them as the nature of the tone structure.

middle Ages

Cassiodorus , who contributed to the development of the Seven Liberal Arts by combining ancient science and Christian faith , defined music as "(...) disciplina, quae de numeris loquitur" ("Music is knowledge that is expressed through numbers"). Alkuin and Rabanus Maurus followed this logical- rational understanding . Isidore von Sevilla spoke of “Musica est peritia modulationis sono cantique consistens” (“Music consists of the experience of the sounding rhythm and the song”). Dominicus Gundisalvi , Robert Kilwardby , Bartholomaeus Anglicus , Walter Odington and Johannes Tinctoris received this judgment, which is more sound and sensory .

Augustine's definition of the term underwent a major change in the Middle Ages through the treatise Dialogus de musica attributed to Odo von Cluny . He expanded the view to include a theological component by citing “concordia vocis et mentis” , the “unity between voice and spirit”, as the central point of making music. The idea was picked up by Philippe de Vitry . An anonymous treatise from the Middle Ages leads from "Musica est scientia veraciter canendi" ("Music is the science of true singing") that the sincerity of the singer is more important than theoretical knowledge and practical skill. This was found again in Johannes de Muris and Adam von Fulda .

Early modern age

The definitions Augustine and Boëthius continued to apply throughout the 15th and 16th centuries. At the same time, an interpretation related to music practice emerged, which became popular as "Musica est ars recte canendi" ("Music is the art of singing correctly") - although in the numerous papers also debite ("due"), perite ( "Knowledgeable"), certe ("sure") or rite ("according to custom or custom"). She appears u. a. with Johann Spangenberg , Heinrich Faber , Martin Agricola , Lucas Lossius , Adam Gumpelzhaimer and Bartholomäus Gesius , whose music-theoretical guides were used for teaching in Latin schools up to the 17th century , with singing being the main focus. Daniel Friderici quoted it as the German guiding principle music is the right art of singing in his Musica Figuralis (1619).

18th and 19th centuries

The rationalism of the 18th century is evident in Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz 's conceptualization : "Musica est exercitium arithmeticae occultum nescientis se numerare animi" ("Music is a hidden art of arithmetic of the mind that is unconscious of counting").

At the end of the 18th century, at the beginning of the Viennese Classicism and on the eve of the French Revolution , the rationalist concept of music replaced its diametrical opposite: a subjective , purely emotional definition prevailed. Whereas musicians such as composers and theorists had previously defined the term, the essential definitions from the artist's perspective were now provided by poets such as Wilhelm Heinse , Novalis , Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder and Jean Paul as the aesthetics merged into the romantic unity of the arts . The focus was on personal experience and feelings.

This is how Johann Georg Sulzer put it : "Music is a sequence of tones that arise from passionate feelings and consequently depict them." Heinrich Christoph Koch's phrase "Music is the art of expressing sensations through tones " is a model for the entire century . This seemed hardly changed from Gottfried Weber to Arrey von Dommer . The popular view that music is a “language of feelings”, which is still popular to the present day, has been widely recognized. The founder of historical musicology Johann Nikolaus Forkel expressed himself in this way, as did the composers Carl Maria von Weber , Anton Friedrich Justus Thibaut and Richard Wagner . Wagner's concept of the total work of art shaped the further development.

During the transition from idealism to irrationalism it was noticeable that the music was elevated to the metaphysical and transcendent. So called Johann Gottfried Herder music a "revelation of the invisible" for Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling she was "nothing but the rhythm and the harmony he had heard of the visible universe itself" .

Echoes of the rationalist view are also present in 19th century musical thought. As early as 1826, Hans Georg Nägeli had called music a "moving play of tones and rows of tones" . In 1854, Eduard Hanslick found in the music- aesthetic basic writing From musical-beautiful to the concise formula that the content and object of music are only "sounding forms" . Before the dispute over program music against absolute music , he became the spokesman for an aesthetic party.

From the 20th century

Ernst Kurth's turn to the irrational forces of music was still under the influence of the 19th century in his late work, Romantic Harmonics and its Crisis in Wagner's “ Tristan ” (1920): “Music is the projected radiation of far more powerful primal processes whose forces revolve in the inaudible . What is commonly referred to as music is really just its fading away. Music is a force of nature in us, a dynamic of volitional impulses. ” In 1926 , Hans Pfitzner's musical thinking was still rooted in the spirit of late Romanticism , especially in Schopenhauer's view: “ Music [is] the image of the world itself, that is, of the will by reproducing its innermost emotions. "

In stylistic pluralism from modern times onwards, no valid statements can be made about the nature of music, since the composers individually decide on their aesthetic views. Since then they have based their definition of music on their own composition practice. Arnold Schönberg referred in his theory of harmony (1913) to the ancient idea of a mimetic art, but at the same time assigned it the status of the highest and most extreme spirituality.

“At the lowest level, art is a simple imitation of nature. But soon it is an imitation of nature in the broader sense of the term, that is, not just an imitation of external but also of internal nature. In other words: it then does not just represent objects or occasions that make an impression, but above all these impressions themselves. At its highest level, art is exclusively concerned with the reproduction of inner nature. Its purpose is only to imitate the impressions that have now entered into connections to new complexes and new movements through association with one another and with other sensory impressions. "

In contrast, Igor Stravinsky categorically denied the expressiveness of music. Its neoclassical definition ties in with the medieval conception of music as a principle of world order.

“Because I am of the opinion that music is essentially incapable of 'expressing' anything, whatever it may be: a feeling, an attitude, a psychological state, a natural phenomenon or whatever. The 'expression' is never one has been an intrinsic property of music, and in no way is its raison d'etre dependent on 'expression'. If, as is almost always the case, the music seems to express something, it is illusion and not reality. (...) The phenomenon of music is given for the sole purpose of establishing an order between things and, above all, of establishing an order between people and time. "

General definitions were seldom made after 1945. On the one hand, since the beginning of the modern era , attempts to determine what was going on had always referred exclusively to art music and largely ignored popular music - dance and salon music , operetta and musical , jazz , pop , rock music and electronic music styles such as techno and industrial, etc. On the other hand, the trend continued towards designs that some composers only undertook for themselves, sometimes only for individual works . These definitions were sometimes based on anchoring in the transcendental, e.g. B. Karlheinz Stockhausen , but occasionally also under the influence of Happening , Fluxus , Zen and other intellectual ideas radical redefinitions up to "non-music" or the idea of music of the actually imaginable, as z. B. John Cage put it: "The music I prefer, even to my own or anybody elses's, is what we are hearing if we are just quiet." ("The music I prefer, my own or the music of others, is what we hear when we are just silent.")

Classifications of the concept of music

According to modern understanding, the term music is sounding and perceptible sound . However, this meaning only emerged in a process that lasted for over two millennia and produced a variety of classifications that reflect the respective understanding of the world at the time of its creation.

Antiquity

Like the first definitions, the first distinctions between theory and practice had their origins in antiquity . The pair of terms goes back to Aristoxenus in the 4th century BC. BC back. Plutarch made a further differentiation of the theoretical components with the subdivision into harmony (as the relationship between the tones, the melody is meant), rhythm and metrics . While Plutarch's classification was still in use until the 16th century, the comparison of Aristoxenus is still valid today.

A further subdivision was made by Aristeides Quintilianus . He introduces acoustics as a theory of sound in the theoretical area and music education in the practical area . He attributed melodies and rhythms to musical practice, which he also expanded to include the teaching of the human voice and musical instruments .

Middle Ages and early modern times

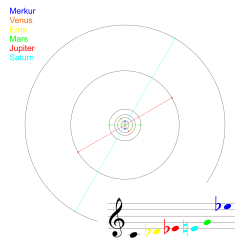

Mercury : small decimals - Venus : Diësis - Earth : semitone - Mars : fifth - Jupiter : minor third - Saturn : major third

At the transition to the early Middle Ages , Boethius divided music into three parts. The first is the musica mundana , the idea , known since Pythagoras, of an inaudible but conceivable music of the spheres as cosmological numerical relationships of the planetary orbits . The second is the musica humana , which acts as a divine harmony of body and soul. The third is the musica instrumentalis , the actually sounding and audible music - this in turn is divided into the instrumentum naturale , i.e. H. the vocal music produced by the “natural instrument” and the instrumentum artificiale , i.e. the instrumental music that produces the “artificial sound tools”.

Around 630, Isidore of Seville classified the sounding music into three areas according to the type of tone generation: first, the musica harmonica , vocal music, second, the musica rhythmica , the music of string and percussion instruments , third, the musica organica , the music of the wind instruments . He gave the terms harmony and rhythm for the first time a second meaning that went beyond Plutarch.

At the end of the 8th century, Regino von Prüm reclassified music by combining its parts into two larger areas. This is on the one hand the musica naturalis , the harmony of spheres and body-soul produced by God's creation as well as the sung music, on the other hand the musica artificialis of the artificial sound generator invented by man , i.e. H. all types of instruments. In the 9th / 10th In the 19th century, Al-Fārābī unified the previous systematics into the pair of theory and practice; he only counted speculative music viewing as theory, i.e. in the broader sense all music philosophy , and practice all other areas that relate to active music practice with its technical foundations. The medieval classifications were received well into the 17th century, a processing of Boëthius even afterwards, as in Pietro Cerone , Athanasius Kircher or Johann Mattheson .

In addition to the main systematics, classifications also appeared in literature from the Middle Ages onwards that attempted to organize the individual areas of music according to other aspects. The following pairs of opposites appeared:

- musica plana or musica choralis (monophonic music) versus musica mensuralis or musica figuralis (polyphonic music)

- musica recta or musica vera (music from the diatonic set of notes) versus musica falsa or musica ficta (music from the chromatic set of notes)

- musica regulata (art music) versus musica usualis (everyday, i.e. folk music )

A first sociological approach was around 1300 the distinction of Johannes de Grocheo , who divided music into three areas:

- musica simplex vel civilis vel vulgaris pro illitteratis , the "simple, bourgeois, folk music for the uneducated", d. H. any form of secular music

- musica composita vel regularis vel canonica pro litteratis , the "regularly and artistically composed music for the educated", d. H. the early polyphony

- musica ecclesiastica , church music, d. H. the Gregorian chant

From the 16th century

In the 16th century the terms musica reservata and musica poetica appeared , the former as a term for the new style of expression in Renaissance music , the latter as a term for composition . Together with the new forms musica theoretica and musica practica , this established itself within a tripartite division based on ancient models. At the same time, it marks the first steps towards a re-evaluation of the composer , who was previously considered to be a skilful “composer” and who is now gradually rising to a creative artistic personality in the social fabric.

The theorists of the 16th century, first and foremost Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg , Jakob Adlung and Jean-Jacques Rousseau , initially pursued the ancient distinction between theory and practice. They divided the theory into four subjects, acoustics, canonics (the study of forms and proportions), grammar (the study of intervals ) and aesthetics ; they divided the practice into composition and execution, i.e. production and reproduction of the musical work of art.

Lexicography and terminology

The linguist Kaspar von Stieler introduced the most common German-language terms into lexicography with his dictionary Der Teutschen Sprache Genealogy and Fortwachs (1691) . Buzzwords such as church music , chamber music and table music were listed here for the first time. The diverse compounds on the basic word music in relation to instrumentation ( harmony music ) , function ( film music ) or technology ( serial music ) originated here. At this point, the use of language also changed, which always meant sounding, sensually perceivable music in the basic word music and now finally departed from the theoretical concept of musica . As a further contribution to the terminology , Johann Gottfried Walther worked out a large number of definitions in the Musicalisches Lexikon (1732), such as B. the historical terms musica antica and musica moderna or the ethnological musica orientalis and musica occidentalis .

Musical material

The source material of sounding music are sound events , i. H. Tones ( periodic oscillations ), noises (non-periodic oscillations), in individual cases noise (oscillations with statistically normal frequency changes ) and bang (impulsive, non-periodic energy boost without tone character). They are at the same time their naturally occurring basis, which arises without human intervention, but can also be created willingly by humans and their individual parameters can be changed.

- Changing the basic frequency creates a perceptible and distinguishable pitch .

- According to the amplitudes of by the resulting adjustment - changes sound pressure changes - the volume .

- The length of the sound event over time defines the duration of the sound .

- Changes in the acoustic spectrum , for example through modifications of the frequency spectrum or the overtones or the envelope , in particular their transient process, determine the timbre impression .

None of the parameters should be viewed independently of the others. In the conscious control of the individual sizes, tones and sounds are created , in the narrower sense the materials from which principles of order emerge that can be used to create any complex space-time structures: melody , rhythm , harmony . From them, in turn, musical works ultimately emerge in a creative process .

On the one hand, the musical material is subject to physical laws, such as the overtone series or numerical ratios , and on the other hand, due to the way it is generated with the human voice , with musical instruments or with electrical tone generators, it has certain tonal characteristics .

In addition to the ordered acoustic material, the music contains the second elementary component, the spiritual idea, which - like form and content - does not stand next to the material, but rather forms a holistic form with it. Tradition and history emerge from dealing with the spiritual figure.

Musicology

→ Main article: Musicology

As a curriculum, musicology comprises those scientific disciplines in the humanities , cultural , social and scientific- technical context, the content of which is the research and reflective representation of music in its various historical, social, ethnic or national manifestations. The subject of musicology is all forms of music, its theory, its production and reception, its functions and effects as well as its appearance, from the musical source material sound to complex individual works.

Since the 20th century, musicology has been divided into three sub-areas, historical musicology , systematic musicology and music ethnology . This structure is not always strictly adhered to. While on the one hand ethnomusicology can also be assigned to the systematic branch, on the other hand practical areas are referred to as applied musicology.

Historical research areas in musicology tend to be idiographical , that is, they describe the object in historical change, the systematic ones tend to be nomothetic , i.e. H. they seek to make general statements that are independent of space and time. Regardless of this, the scientific paradigms of the two areas are not to be regarded as absolute, since historical musicology also tries to recognize laws over the course of time, while systematics and ethnology take the historical changes in their subjects into account.

Historical musicology encompasses all sub-disciplines of musical historiography and is mainly devoted to the development of sources on European art, folk and popular music. Systematic musicology, on the other hand, is more strongly influenced than its historically oriented parallel branch by the humanities and social sciences, natural and structural sciences, and uses their epistemological and empirical methods.

The ethnomusicology deals with the music existing in the customs of the ethnic groups . Of interest are both the musical cultures of indigenous peoples who do not have writing and notation, as well as - from a historical point of view - the music of the advanced cultures and their influences. Important research topics are sound systems , rhythms, instruments, theory, genres and forms of music against the background of religion, art, language, sociological and economic order. In view of migration and globalization , inter- and transcultural phenomena are also taken into account.

Beyond the canon of musicological disciplines, music is the subject of research z. B. in mathematics and communication science , medicine and neuroscience , archeology , literature and theater studies . A distinction must be made in each individual case whether it is music as the research object of other sciences or whether musicology investigates non-musical areas. Music therapy occupies a special position, combining medical and psychological knowledge and methods with those of music education.

Music as a system of signs

Music can also be viewed as a system of signs, among other things. In this way, music can communicate intended meanings in active, understanding listening. Hearing represents a structuring process in which the listener distinguishes iconic , indexical and symbolic sign qualities and processes them cognitively . On the one hand, this is based on people's primal experiences of hearing and assigning sound events pictorially - e.g. B. Thunder as a threatening natural event - and to reflect emotionally, on the other hand on the aesthetic appropriation of the acoustic environment. This ranges from the functionalization of the clay structures as signals to the symbolic transcendence of entire works .

Music and language

The view of the origin of music from the origin of the language or their common origin from one origin is based on cultural anthropology . It is rooted in the ideas at the beginning of cultures. Reflections of the early non-scripted cultures can also be found in the present among primitive peoples , sometimes in animistic or magical form. The formula mentioned at the beginning of the Gospel of John "In the beginning was the word" ( Joh 1,1 LUT ) describes one of the oldest thoughts of mankind, the origin of word and sound from a divine act of creation. It occurs in almost all high cultures , in Egypt as the cry or laughter of the god Thoth , in Vedic culture as the immaterial and inaudible sound of the world, which is the original substance, which is gradually transformed into matter and becomes the created world. The creation myths often trace the materialization of the phonetic material of the word and language.

Overlaps of music and language can be found in some areas; both have structure and rhetoric . There is no syntax in the classical sense of music and semantics is usually only due to additional linguistic elements, or can arise from encryption within its written form. But the latter is not necessarily audible. Music is therefore not a language, but only language-like.

A main difference between the two is the ability to express and communicate semantic content. Music cannot convey denotations . It is language only in the metaphorical sense; it does not communicate anything that is designated . Rather, it is a game with tones (and rows of tones). In order to “understand” music aesthetically, the listener has to understand the internal musical definition processes that organize the music as a system, e. B. recognize dissonances in need of resolution depending on a tonal context . Where there is a linguistic similarity, as in music based on regular rhetoric in the sense of the liberal arts in the Middle Ages and in the Baroque , the listener can basically hear the same music as music without understanding or knowledge of the rules and without knowledge of a symbolic context. Musical thinking and poetic thinking are autonomous.

Structural differences

There is also no syntactic order that would be semantically supported in music. There are neither logical connections nor true or false "statements" on the basis of which one can formulate an aesthetic judgment about their meaning. Logical statements can always be made in the form of language, while musical "statements" can only be made within music through music. So realized z. For example, a chord progression that ends in a fallacy has no extra-musical meaning, but only acquires its meaning within the musical syntax within which it establishes relationships.

The sign systems of language and music are therefore fundamentally different. While language says , the music shows that it processes sensory impressions into ideas , which it in turn presents to the sensual experience. While the language, u. a. With the help of definitions, aiming at clarity , the arts pursue the opposite goal: not the material meanings, but the potential human values are the semantic field of art, which extends to all possible connotations . So, in order to understand it aesthetically at all, music needs an interpretation.

Music is often understood as the “language of feelings”. She is able to describe emotions, affects and states of motivation and to make them accessible to the listener through expression patterns. However, these are not linguistic signs either, as they ultimately appear as a continuum in an “emotional space”, depending on their psychophysiological basis. H. occur not only as different emotional qualities, but in interactions and ambivalent states and processes. The gesture of their expression is not an expansionless logical structure - as it is present in the pair of concepts of the signifying and the signified - but of a temporal nature. It can be structured in terms of time, but also through overlapping emotions, e.g. B. in the emotional continuum "joy + sadness → anger". An upswing can already have grief in it or vice versa. The basic principle that makes gestural forms the meaning of musical signs is an analog coding that uses indexical or iconic signs for expression - they do not correspond to a single cognitive content, but to a class of cognitive correlates . This can also be seen in the case of several settings of the same text that are perceived to be differently appropriate, just as, conversely, the same music can be placed under several texts that each appear more or less suitable.

Icon and index

The reference relations icon and index can basically be transferred to music. However, they cannot always be categorized . The same sign, the cuckoo call, appears as a falling third or fourth , in the musical context with different meanings: iconic as an acoustic image in the folk song Cuckoo, Cuckoo, calls from the forest , indexically as an expression of the experience of nature at the end of the scene at the brook from Ludwig van Beethoven 6th symphony , finally symbolic for the whole of nature at the beginning of the first movement of Gustav Mahler's 1st symphony .

The most noticeable forms of indexical sign usage are prosodic features , the intonation or coloring of the voice as used in the singing itself. This also includes stylizations such as the “sigh” of the Mannheim School , a clay figure made of a falling small second , which appears very often in Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's work and was already considered a sign of (emotional) pain in the baroque doctrine of affect .

Iconic signs can be found above all in descriptive music, in program music as well as in film music . In the latter, the process known as Mickey Mousing is primarily used to synchronously imitate the visual characters of the film. There are also examples of the iconic use of signs in the doctrine of affect, e.g. B. in the word-tone relationship , according to which high or low tones stood for "heaven" and "hell".

symbol

The widest range of signs is symbolic . It is no longer a question of images, but rather a representation of symbols based on convention . It is not semiotically meaningful, but conveys a content that is mostly extra-musical. This can apply to all elements of music: to the key of C major , which in the 1st scene of the 2nd act of Alban Berg's opera Wozzeck expresses the banality of money, to an interval like the tritone , which is called “Diabolus in Musica “Has stood for evil since the Middle Ages, on the single tone d ', which in Bernd Alois Zimmermann's work for deus , d. H. God stands, or a rhythm that embodies fate in the final movement of Mahler's 6th Symphony . It is not possible to listen out without prior knowledge of the symbolic content. Entire musical works such as national , national and corporate anthems also have a symbolic content.

In individual cases, symbolic content is used as ciphers , e.g. B. as a sequence of notes BACH , which was used musically by Johann Sebastian Bach himself and by many other composers, or in Dmitri Shostakovich's name sign D-Es-CH , which the composer used thematically in many of his works.

A mannerist fringe phenomenon of symbolism is eye music , which transports the symbolic content of the music not through its sound, but through the notation , in which the musical quality of symbols is visualized so that they are only revealed to the reader of a score .

signal

Signals are a special case in the border area between music and acoustic communication. They are generally used to a information to transmit and trigger a desired action. The quality of their drawing has to attract attention, for example through high volume or high frequencies . If they are to provide precise information on a bindingly defined action, they must be clearly distinguishable. In the narrower (musical) sense, this applies above all to military and hunting signals . However, semantizations can also be found in this area. The hunting signal fox dead, for example, which gives the hunting party information, is composed of musical images. An iconic description of the jumping of the fox and the fatal shot is followed by a stylized lament for the dead and the symbolic Halali . The signal begins with a three-time initial bell that prompts you to cross. The following verse is rung twice for the death of a woman and three times for the death of a man. The repetition of the beginning marks the end of the message. Other acoustic signal forms such as tower bubbles or bells also use simple rhythmic or melodic designs. In a broader sense, this character quality also occurs with sequential horns or ring tones .

Drawing process

In a metaphysical universality as formulated by Charles S. Peirce for the process of semiosis , i.e. H. for the interaction of sign, object and interpreter , the musical signs can belong to different modes of being . In the ontological or phenomenological framework, they are or appear in different categories analogous to a transcendental deduction : as being, iconic or indexical as a carrier of a function or in a dimension related to the human being, as a symbol beyond the human dimension, and finally as transcendent.

| thing in itself | Being and function | Being and meaning | Meaning without being |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4th as overtone | Tempered fourths on the piano | Quarts as a tone cipher (e.g. as a monogram a – d for “ Antonín Dvořák ” in his 6th symphony) | Fourth in the harmony of the spheres |

| Birdsong in nature | Imitated birdsong as a lure | Bird song as a symbol of nature, e.g. B. in Beethoven's 6th symphony | Birdsong on the Day of Judgment as a sign of reconciliation (in Mahler's 2nd Symphony ) |

Not all appearances or art structures reach the level of transcendence; it is only the last conceivable stage towards which the process of semiosis tends. The categorization is never to be viewed statically, signs can be used in a musical context, i.e. H. also change their quality in the flow of time or give them a different functionality. At the beginning of the final movement of Beethoven's 1st Symphony , the listener takes up an asemantic tone figure that always begins on the same keynote and increases with each new entry; the “scale”, which is not initially determined in its key, since it can have both the tonic and the dominant reference, is functionalized with the onset of the faster main tempo as a motivic component of the first theme . However, the listener can only make this assignment retrospectively from the auditory impression, so that he cognitively processes the semiotic process only from the context of a larger unit.

Music and visual arts

Although ostensibly music as a pure contemporary art and transitory, i. H. In contrast to the static-permanent spatial arts, painting , sculpture , drawing , graphics and architecture appear temporarily , as they are shaped by their spatial and non-temporal ideas and have also influenced them with their perceptions of temporality and proportion. Terms such as “tone space”, “ tone color ” or “hue”, “high / low” tones and “light / dark” sounds and similar synaesthetic expressions , the ambiguity of “composition” in musical thinking and in that of the visual arts are part of the ubiquitous description vocabulary . The experience that an acoustic effect such as reverberation or echo only occurs in connection with the room is part of the primal possession of humans. Since the earliest theoretical approaches, parallels between acoustic and spatial-visual art forms have been identified.

There are also similarities between music and the visual arts in terms of art historical epochs, for example in connection with the Baroque era . Since no clear delimitation of the epochs can be made, the terms form theory (music) and art style are used.

Music and architecture

The idea of the relationship between music and architecture has existed since ancient times . It is based on common mathematical principles. The Pythagoreans understood the interval proportions as an expression of a cosmic harmony . In their opinion, music was a mode of numerical harmony that also yields consonant intervals in vibrating strings if their lengths are in simple integer ratios. The proportions of numbers were considered an expression of beauty until the early modern times , just like the arts that use numbers, measurements and proportions were considered suitable for creating beautiful things in antiquity and the Middle Ages . Vitruvius's architectural theoretical writing De architectura libri decem made explicit reference to ancient music theory , which he described as the basis for understanding architecture.

Medieval architecture took up ancient ideas in a Christian sense. The Gothic often showed interval proportions in the main dimensions of the church buildings. The temple of Solomon was exemplary , its shape u. a. Peter saw Abelardus as a consonant. Complex mathematical phenomena such as the golden ratio and the Fibonacci sequence were also interpreted in Christian terms. They appear equally in Filippo Brunelleschi's dome design of Santa Maria del Fiore and in Guillaume Dufay's motet Nuper rosarum flores (1436). The work for the consecration of the Duomo of Florence shows the same numerical proportions in the course of the voice and work structure that determined the architecture of the dome.

During the Renaissance, the theorist Leon Battista Alberti defined a theory of architecture based on the Vitruvian theory of proportions. He developed ideal proportions for room sizes and heights, area subdivisions and room heights. Andrea Palladio's Quattro libri dell'architettura (1570) systematized this theory of proportions on the basis of thirds , which were first recognized as consonant intervals in Gioseffo Zarlino's Le istituzioni armoniche (1558). This brought about a change in harmony that extends to the present day .

Under the influence of modern music aesthetics , the musical numerical reference gradually faded into the background in architectural theory. The taste judgment as a criterion of the aesthetic assessment prevailed. It was not until the 20th century that numerical proportions, as architectural and musical parameters, once again took on the rank of constructive elements. In the architectural field, this was Le Corbusier's Modulor system. His pupil Iannis Xenakis developed the architectural idea in New Music in the composition Métastasis (1953/54) . He then implemented the compositional design in the design of the Philips Pavilion at the Expo 58 in Brussels .

Synthetic art forms

Among the synthetic art forms that emerged after the end of the universally valid principle of harmony, Richard Wagner's concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk became important for the 19th century. The architecture assumed a serving position in the realization of the musical idea. She had the practical space environment for the unity of the arts, i.e. H. of musical drama . Wagner realized his claims in the festival theater built by Otto Brückwald in Bayreuth .

The Expressionism took the early 20th century on the art synthesis. The central vision of allowing people to overcome social boundaries led to many art designs, some of which were never realized. This included Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin's spherical “Temple” for the Mystery (1914), a work of revelation composed of word, sound, color, movement and fragrance.

The art movements of the second half of the 20th century integrated musical elements in multimedia forms, in "sound sculptures" and "sound architecture". Architecture was increasingly given a temporal component, music a spatial component. Karlheinz Stockhausen combined his ideas of spatial music in a ball auditorium, which he installed at the Expo '70 in Osaka . The listeners sat on a sound-permeable floor, surrounded by electronic music . The loudspeakers distributed in the room made it possible to move the sounds in the room.

Architecture and room acoustics

The St. Mark's was one of the early experimental rooms for music. The composers researched the spatial effect of several sound bodies and implemented the results in new compositions.

The old Leipzig Gewandhaus consisted of only one upper floor. Nonetheless, from 1781 to 1884 it experienced the flourishing orchestral culture of German Romanticism.

The multi-choir developed in the 16th century , which was cultivated among the European music centers especially at the Venetian St. Mark's Basilica , used the effect of several ensembles in the room. Chamber music and church music separated according to instrumentation , rules of composition and presentation style. They adapted to the acoustics of their performance locations. To this end, the architecture developed its own room types, which were dedicated to music and created acoustically advantageous conditions for its performance. The first chambers were built in the princely palaces, later in castles and city apartments. This also changed listening behavior: music was heard for its own sake, free of functional ties and for pure enjoyment of art.

The public concert industry emerged in London towards the end of the 17th century . Music events no longer took place in ballrooms, taverns or churches, but in specially built concert halls . Although the halls only held a few hundred listeners at that time, had no fixed seating and served all kinds of festive occasions in addition to music, they already had significantly improved room acoustics , in which the orchestral music came into its own. The first building of the Leipzig Gewandhaus (1781) was exemplary . After its design as a narrow and long box hall with a stage podium and level parquet , many more halls were built in the 19th century that the culturally interested bourgeoisie used as places of music care.

In particular, the symphonic works of romantic music with their enlarged orchestra profited from the concert halls. The acoustics of these halls combined richness of sound with transparency ; the narrow design led to strong reflection of the side sound, the large room volume in relation to the interior area optimized the reverberation time to an ideal level of one and a half to two seconds. The size of the halls - they now held around 1,500 listeners - resulted from the fact that subscription concerts had established themselves as part of the city's cultural life. The most important concert venues of this era are the Great Hall of the Wiener Musikverein (1870), the New Gewandhaus in Leipzig (1884) and the Amsterdam Concertgebouw (1888).

New technical possibilities and the need to consistently use halls economically changed architecture in the modern age. Cantilever balconies, artistically designed halls in asymmetrical or funnel shape and a capacity of up to 2,500 seats characterized the concert halls in the 20th century. The Philharmonie in Berlin and the Royal Festival Hall in London were two important representatives of new building types. The latter was the first concert hall to be built according to acoustic calculations. Since the 1960s there has been a trend towards building halls with variable acoustics that are suitable for different types of music.

Music and visual arts

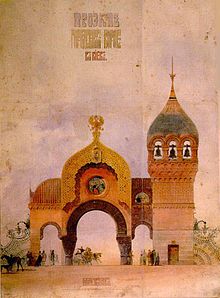

The manifold relationships between music and the visual arts have been drawn historically through the theoretical consideration of both arts as well as through practical work, which was reflected in mutual influences. Visual artists and composers increasingly included other art in their work, formed project-related working groups or created multimedia works together. A number of works of painting found their way into music: The Battle of the Huns (Liszt) , Pictures at an Exhibition , The Island of the Dead . This picture by Arnold Böcklin inspired Max Reger , Sergei Wassiljewitsch Rachmaninow and other composers to write symphonic poems . This contrasts with portraits of composers and countless genre images of musicians, which also serve as research material for iconography .

Parallel developments are not always evident. Only parts of the history of style found an equivalent in the opposite side. Art historical terms such as symbolism , impressionism or art nouveau can neither be clearly distinguished from one another nor easily transferred to music. If, for example, a comparison is drawn between the pictorial figures of Claude Monet and the “ impressionistic ” music of Claude Debussy and is explained by the blurring of the form or the representation of the atmosphere, this is in contradiction to Debussy's aesthetic. Likewise, parallel phenomena such as New Objectivity cannot be explained one-dimensionally, but only from their respective tendencies; while it was a demarcation from Expressionism in art and literature , it turned against Romanticism in music .

Ancient and Middle Ages

The ancient relationship between the arts clearly separated the metaphysical claims of music and the visual arts. The dual form of μουσική - on the one hand art, on the other hand the intellectual preoccupation with it - was valued as an ethical and educational asset. Painting, however, was considered bad and only produced bad, as Plato's Politeia explains, since it is only an art of imitation . The difference, which is by no means to be understood aesthetically, was based on the Pythagorean doctrine, which understood music to be a reflection of cosmic harmony in the form of interval proportions. So painting found no place in the Artes Liberales .

This view persisted into late antiquity. The Byzantine iconoclasm represented the most violent politically and religiously motivated rejection of art, which, however, did not affect music: as a reshaped symbol of the divine world order of measure and number, it found its way into Christian cult and the liturgy . The Middle Ages codified this separation and added the visual arts to the canon of Artes mechanicae .

From the Renaissance to the Enlightenment

Leonardo's Vitruvian Man redefined the proportion of the arts. Painting was no longer the leading art of the Renaissance; no longer the cosmic , but the body proportions were the frame of reference. The upgrading of painting to fine art began in the Renaissance with reference to the creative work of visual artists. It was still placed under music, which in Leon Battista Alberti's art theory becomes a model for architecture, on the other hand it already stood above poetry . Leonardo da Vinci undertook the first scientification of painting , for whom she surpassed music, since her works can be permanently sensually experienced while music fades away. This process began against the background of secular humanism , which gave art neither a political nor a religious meaning.

The Age of Enlightenment finally placed the human being as the observing and feeling subject in the center. From this positioning of autonomous art over science, the understanding of art developed, which has prevailed up to the present day. The arts subsequently developed their own aesthetic theories.

18th and 19th centuries

Since Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten's Aesthetica (1750/58), art itself has moved closer to philosophy or is viewed as a separate philosophical discipline. With this, music lost its special position within the arts and was incorporated into the fine arts, which redefined their hierarchy through their own aesthetics. Immanuel Kant's Critique of Judgment (1790) also included it in the pleasant arts; H. As beautiful art it is now superior to painting, but as pleasant art it is subordinate to it because it means more enjoyment than culture.

A fundamental shift occurred in romantic aesthetics, which sought to fuse the arts and ideals of art. This becomes evident in Robert Schumann's parallelization of art views.

“The educated musician will be able to study a Raphael's Madonna with the same benefit as the painter can study a Mozart's symphony. Even more: for the sculptor every actor becomes a quiet statue, for him the works of the other become living figures; for the painter the poem becomes a picture, the musician transforms the painting into sounds. "

The music in Arthur Schopenhauer's recourse to antiquity was uniqueness ; In The World as Will and Idea (1819) he denies its mimetic properties.

Art theories in the 19th and 20th centuries

In the late 19th century, art history and musicology were established in the humanities faculties . Music was thus separated from the visual arts and architecture in its academic view.

The symbolist and impressionist painting, music and literature and the beginning of abstraction changed the relationship through increasing reflection of the artists on the neighboring arts, which also included aspects of their own work. Paul Gauguin was influenced by a romantic understanding of music :

“Think also of the musical part that will play the role of color in modern painting in the future. The color is just as vibration as music is able to achieve what is the most general and yet least clear in nature: its inner power. "

Henri Matisse described his creative process as musical. With his work Über das Geistige in der Kunst (1912), Wassily Kandinsky redeemed Goethe's criticism that painting “(...) has long since lacked knowledge of the thoroughbass (...) [and] an established, approved theory of how it is the case in music ” . He interpreted it as a prophetic utterance heralding a kinship between the arts, especially music and painting. This is meant as a reference back to the cosmological principle as it appeared to the Pythagoreans for the metaphysical foundation of music, and at the same time as its extension to the visual arts. Paul Klee followed suit in his Bauhaus lectures in that he used musical terminology to explain the visual arts. Later he designed an art poetics based on questions of music theory.

The relationship between music and the visual arts after 1945 grew out of aesthetic theoretical approaches. The focus was on a systematic classification of the two arts. In his view, Theodor W. Adorno necessarily separated them into music as temporal art and painting as spatial art. He saw crossing borders as a negative tendency.

"As soon as one art imitates the other, it distances itself from it by denying the compulsion of its own material and degenerates into syncretism in the vague idea of an undialectical continuum of arts in general."

He recognized that the arts are systems of signs and are of the same content that they allow art to convey. However, he thought the differences were more important than the similarities. For Nelson Goodman , the problems of art differentiation presented themselves as epistemological , so that he wanted to put a symbol theory in place of an aesthetic theory in general . As the boundary of the aesthetic to the non-aesthetic he looked at the difference of exemplification and denotation : either during the Visual Arts autographic because their works after the creative process are (which is also original and fake differ) is the two-phase music allographisch because their listed works require a performance first - although this distinction only extends to art.

Musicality

Musicality encompasses a multi-graded field of characteristics of mutually dependent talents and learnable skills. It is not to be understood as an absolute measure as it can appear in many different active and passive forms. There are numerous test models for measuring musicality, of which u. a. the Seashore test is used as part of entrance exams. Basically, musicality is universally present in every person .

Music-related perception includes recognizing and differentiating pitches, tone durations and volume levels. The perfect pitch comes at the performance of the long-term memory is of particular importance. These skills also include the ability to grasp and retain melodies , rhythms , chords and timbres . With increasing experience in dealing with music, the ability to classify music stylistically and to evaluate it aesthetically develops . Practical musicality includes the productive skills of technically mastering the voice or a musical instrument and using them to create musical works artistically.

A musical disposition is a prerequisite for musicality to develop to an appropriate degree. However, it is not the cause of this, so that intensive support - for example at music high schools or through support for the gifted - enables the full expression of musicality to develop.

Aesthetic aspects

With the increasing complexity of its manifestations, music emerges as an art form that develops its own outlook and aesthetics . In the course of history - in Europe since the late Middle Ages on the border with the Renaissance - the individual work of the individual composer comes to the fore, which is now considered in music historiography in its temporal and social position. Since then, the musical work of art has been regarded as the will of expression of its creator, who thus refers to the musical tradition. His intentions are recorded in notation , and in some cases also additional comments, which musicians use as hints for interpretation. This can follow the intent of the composer, must it not; she can bring in her own suggestions as well as disregard the intention and function of the work - this happens, for example, when using symphonic works as ballet music or when performing film music in a concert setting.

Music does not always claim to be art. The folk music of all ethnicities in history hardly contains that unique and unmistakable that actually defines a work of art; it also has no set forms, but only manifestations of models and changes through oral tradition, Umsingen or Zersingen, similar to the children's song , the melodies over time. Even with improvisation there is no fixed form, it is unique, never to be repeated exactly and can hardly be written down. Nevertheless it is part of musical works in jazz and solo cadenza , in aleatoric it is the result of an “open” design intention , in the Indian models raga and tala as well as in the maqamāt of classical Arabic music an art music determined by strict rules, which in their entire temporal expansion and internal structure is not fixed, but is up to the musician and his intuition or virtuosity . In the 21st century, the term spontaneous composition is increasingly used for forms of improvisation .

Listening to and understanding music is a multi-stage aesthetic - semiotic process. The listener picks up the physical stimuli and establishes the relationships between their individual qualities such as pitch, duration, etc., in order to then recognize motifs and themes as smaller, period and sentence as larger orders and finally to grasp forms and genres . In addition, the sense and meaning of music can be derived from its structure of signs , which has language-like features without music being a language. This cognitive or cognitive understanding requires on the one hand the prior knowledge of the listener, who must have already dealt with the compositional, historical and social conditions of the work, on the other hand it depends on the intentional attitude towards the musical work. In addition, hearing is a sensual experience that creates a subjective and emotional turn to music, and thus an active process overall.

Areas of application and effect

Social and psychosocial aspects

Studies show that music can promote empathy and social and cultural understanding among listeners. In addition, musical rituals in families and peer groups increase the social cohesion among the participants.

According to current knowledge, the ways in which music develops this effect also include the simultaneity (synchronicity) of the reaction to music as well as imitation effects. Even young children develop more prosocial behavior towards people who move in sync with them.

→ See also: Music Psychology

Music education

→ Main article: Music education

Music pedagogy is a scientific discipline closely related to other pedagogical areas that encompasses the theoretical and practical aspects of education , upbringing and socialization in relation to music. It takes up the knowledge and methods of general pedagogy , youth research and developmental psychology as well as several musicological sub-areas on the one hand, and the practice of making music and music practice on the other. Her goals are musical acculturation and the reflective use of music in the sense of an aesthetic education .

The basic ideas of school music originated from the youth music movement , whose strongest supporter Fritz Jöde promoted above all the common singing of folk songs and put practical music making before considering music. This happened after 1950 a. a. in Theodor W. Adorno criticism, who saw the social conditioning of the artwork and its critical function not sufficiently taken into account.

“The purpose of musical pedagogy is to increase students' abilities to such an extent that they will learn to understand the language of music and major works; that they can present such works to the extent necessary for understanding; to bring them to differentiate between qualities and levels and, by virtue of the precision of sensual perception, to perceive the spiritual that makes up the content of every work of art. Music pedagogy can only fulfill its function through this process, through the experience of the works, not through self-sufficient, as it were blind music-making. "

As a result, the criticism opened up music lessons to many directions, including: a. for the ideas of the Enlightenment in the writings of the pedagogue Hartmut von Hentig . Ideas such as creativity and equal opportunities became just as important as a critical awareness of emancipated behavior in an increasingly acoustically overloaded environment. Popular music and music outside the European cultural area have also played a role since then. Musical adult education and music geragogy for old people represent new currents outside of school education .

Music therapy

→ Main article: Music therapy

Music therapy uses music in a targeted manner as part of a therapeutic relationship in order to restore, maintain and promote mental, physical and mental health . It is closely related to medicine , social sciences , education , psychology and musicology . The methods follow different (psycho) therapeutic directions such as depth psychological , behavioral , systemic , anthroposophic and holistic-humanistic approaches.

The use of music for therapeutic purposes has historically been subject to changing ideas about the concept of music, such as the respective ideas about health, illness and healing. The disaster-repelling and magical power of music was already of great importance among primitive peoples . It is mentioned in the Tanach in the healing of Saul through David's play on the kinnor ( 1 Sam 16,14 ff. LUT ) and in ancient Greece as Kathartik , i.e. H. Purification of the soul. A distinction can be made between the assumption of magical-mythical, biological and psychological-culture-bound mechanisms of action. It should be noted in each case that methods are not easily applicable outside of their respective cultural-historical context.

The current areas of application of music therapy are partly in the clinical area, such as psychiatry , psychosomatics , neurology , neonatology , oncology , addiction treatment and in the various areas of rehabilitation . Areas of work can also be found in non-clinical areas such as curative education , in schools , music schools , in institutions for the elderly and the disabled and in early childhood support . Music therapy takes place in all age groups.

To practice the profession of music therapist requires a degree in a recognized course of study that is taught at state universities in numerous countries .

Media, technology and business

The media capture the fleetingly fading music, make it available to the world and posterity and allow music to emerge in the first place. As notes of a work of art, they are the subject of historical research and value judgment. There is an interaction between the media on the one hand, the performance and composition process and the perception of music on the other; The same applies to the technology that is used for production and reproduction and, in turn, influences the playing technique of the musical instruments. The production, marketing and distribution of music media have been the business goal of an entire industry since the beginning of the printing industry, which has been operating globally as a music industry since the 20th century and has an offer that is no longer manageable.

notation

→ Main article: Notation (music)

If music is not passed on orally, as is the case with folk music, it can be laid down in systems of signs that serve to visualize and clarify musical ideas: notations. A notation bridges time and space; it can be stored and reproduced, duplicated and distributed. It thus serves to provide insights into the creative process of a work and to understand its musical structures. At the same time, it creates one of the prerequisites for composing and realizing the composition idea, as the musical idea is recorded in the notation. Depending on its coding - letters, numbers, discrete or non-discrete graphic characters - a form of notation is able to store information with varying degrees of accuracy. A distinction is made here between result writings, which make an existing context available, and conceptual writings, which record newly invented relationships. The action scripts that prepare the musical text for the playing technique of a particular musical instrument include z. B. Tablatures for organ or lute music . The musical notation in use today still contains isolated elements of the campaign script. Notation can never fully capture a work in terms of its parameters , so that there is always room for maneuver in execution and interpretation; the historical performance practice tried on the basis of sources to make the execution possible faithfully within the meaning of the composer and his aesthetic views.

The first notations are known from ancient Egypt and ancient Greece . The neumes used in Byzantine and Gregorian chant were able to record the melodic movements of monophonic Christian music. They began to develop around the 8th century. The early neumes, however, still required knowledge of the melody and the rhythmic order; they were pure result writing. Around the year 1025, Guido von Arezzo introduced innovations that are still valid in modern notation today: staves in thirds apart and the clefs .

In the 13th century, polyphonic music required a more precise definition of the duration of the notes. The modal notation assigned fixed values for the duration to the individual notes, the mensural notation assigned the proportions of the tone durations to one another against the background of the simultaneous clock system . This meant that tone durations could be represented exactly. The voices were notated individually, recorded separately in a choir book after the completion of a composition and then copied as individual parts for execution.

The standard notation used internationally today has been created since the 17th century. In particular, the precise recording of the durations has been expanded a few times since then. First the basic time measure was determined with tempo markings and time indications, after the invention of the metronome by Johann Nepomuk Mälzel in 1816 it was mechanically reproducible by a precise indication of the beats per minute. Following the example of Béla Bartók , composers also specify the performance times of individual sections in minutes and seconds. New types since the 20th century were graphic notation and recording forms for the production of electronic music .

Sheet music printing

Soon after Johannes Gutenberg's invention of printing with movable type around the year 1450, sheet music printing began . The first printed musical work can be traced back to 1457, and before 1500 Ottaviano dei Petrucci developed the printing technique with movable note types. Important printers and publishers such as Pierre Attaingnant and Jacques Moderne published the chansons , motets and dance pieces of their time in collective editions for the first time - they thus satisfied the public demand for secular music for entertainment and at the same time gained an economic advantage from the sale of large numbers. This also resulted in an increased supra-regional distribution of pieces of music.

Technical processes such as intaglio printing in the 16th century , engraving and lithography in the 18th century considerably improved the quality of the music printing and made it possible to reproduce both extensive and graphically complex music texts. Photo typesetting , offset printing and finally computer-controlled music notation programs expanded these possibilities again.

Reproductive technology

The sound recording began in 1877 with Thomas Alva Edison's phonograph . This apparatus supported until the 1930s the ethnomusicology : alone Bela Bartok and Zoltan Kodaly thus recorded thousands of folk songs in the field research in Eastern Europe and North Africa. In 1887 Emil Berliner developed the first record and the corresponding gramophone . With this device, which soon went into series production and popularized the shellac record as a storage medium, music of all genres found its way into households that did not play house music and used arrangements or excerpts for playing the piano . The invention and marketing of the record soon influenced the music itself; In 1928 Igor Stravinsky signed a contract with Columbia Records to authentically record his works.

Several technical steps improved the record. In 1948, polyvinyl chloride became established as a manufacturing material that allowed records with narrower grooves, significantly extended their playing time and increased the sound quality considerably, as the playback speed fell from 78 to 33 or 45 revolutions per minute. Stereophony , developed long before, led to stereo records in 1958 and to two-channel radio in the 1960s . This required a new generation of playback devices, stereos were sold in large numbers. High fidelity became the standard of sound fidelity . The direct editing process , in which the recording was not recorded on a tape as before , further increased the quality of the music reproduction. A new professional group also established itself: the DJ . In addition, tapes were also popular in the private sector, especially in the form of compact cassettes for playing and recording in the cassette recorder and for mobile use in the Walkman .

The compact disc as a storage medium came onto the market in 1982. It stands at the beginning of the digital media, with which music of the highest quality can be stored in a relatively small space. Another step towards digitization, which accompanied the general spread of computers , was the development of audio formats such as B. MP3 , which allows platform and device-independent use and is another distribution channel on the Internet in the form of downloadable music files.

Audiovisual media

In combination with audiovisual media, music works synergistically . Their connection with forms of expression such as drama or dance has existed in a ritual context since ancient times. The opera emerged from the connection with the drama . On the one hand, the connection with television creates a public for and interest in musical content, on the other hand it creates new genres such as television opera . In the film , the music takes on a variety of tasks, dramaturgical as well as supporting, compared to the visual statement. It intensifies the perception of action, implements the intentions of the film director and contributes to a sensual overall impression for the viewer. From a technical point of view, it must be exactly synchronized with the optical information of the film. The same applies to use in advertising. Another genre is the music video . In contrast to film music, it is the director's task here to dramatically visualize an existing piece of music. When mixed with other media, a music video usually serves to sell the corresponding music, although audiovisual art can also arise here.

Internet

Music was already a relevant topic in the mailbox networks and Usenet during the 1980s . Audio data compression and streaming media as well as higher data transmission rates ultimately made them an integral part of network culture . Due to its decentralized organization, the Internet is not only used for information and communication, but also continuously creates new content, some of which disappear again after a short time.

Streaming media include Internet radio stations that either transmit the terrestrial programs of conventional radio stations on the Internet or offer their own program that is only available via the Internet. Music programs are also transmitted through podcasting . Another possible use is the provision of downloadable files for music promotion . Artists, labels and distributors offer partly free, partly chargeable downloads, which can also be restricted in their type and frequency of use due to digital administration or are subject to copy protection . Individual artists also offer works exclusively on the Internet, so that there is no need to sell the "material" sound carriers. Free bonus tracks are also available or material that does not appear on phonograms.

Information and communication on music-related topics are provided by private homepages, fan pages, blogs and reference works in lexical form. Web portals play an important role in the music offering. While some portals list a range of hyperlinks , others serve the marketing of music in cooperation with the music industry. In addition, there are platforms that provide musicians with online storage space and a content management system for a small fee or free of charge in order to upload and offer their self-produced music. They serve the self-marketing of the artists as well as online collaboration and the formation of social networks through community building .

With file-sharing programs that access the Internet, music files are exchanged between Internet users in a peer-to-peer network. If these are not private copies of copyrighted material, this represents a punishable copyright infringement , which has already led the music industry or individual artists to lawsuits against file-sharing networks and their customers, as the sale through free downloads via P2P programs would be restricted.

Media and concept of work

The concept of the work plays a central role in the consideration of art; the historical musicology sees in him a fundamental cultural model for the assessment of individual modes of music, which is also influenced by them contemporary media. The concept of a work is based primarily on the written fixation of music in the musical text, written or printed. Since humanism, the “work”, also referred to as opus in music, has meant the self-contained, time-enduring individual creation of its author. Even if musical works that correspond to this definition already existed in the late Middle Ages , the term and its meaning for musical aesthetics only emerged and spread in the early modern period . In the foreword of his Liber de arte contrapuncti (1477), Johannes Tinctoris names the works of the great composers as subjects.

“Quorum omnium omnia fere opera tantam suavitudinem redolent, ut, mea quidem sententia, non modo hominibus heroibusque verum etiam Diis immortalibus dignissima censenda sint.”

"Almost all the works of all these [composers] smell so sweet that, at least in my opinion, they are to be considered very worthy not only by humans and demigods, but in fact also by the immortal gods."