Women in music

Women in music is a term that has increasingly come into focus in the wake of the women's movement since the 1970s. Within women's research , the question of the lack of presence of female creative musicians in historiography and - partly because of this - in today's public practice was raised. At no time and nowhere in the world has there been a lack of creative and cultural activity by women, neither in the popular field, nor in “ art music ” or “ classical music ”. Similar to women in science or politics , musically productive women have only emerged from the shadow of their male colleagues since the end of the 20th century. Answers to the questions about why and how arise from modern gender research . See u. a. Annette Kreutziger-Herr, Melanie Unseld (Ed.): Lexicon Music and Gender: Against the »rectification« of music history and the change in science since 1970 . Historical female composers come to mind, modern female composers and performing musicians develop autonomy and self-image. This applies to conductors , orchestral musicians , singers , church musicians , freelance musicians, music educators as well as instrument makers , musicologists , music journalists , music managers , patrons and others involved in music.

Cultural memory

In the course of the second women's movement in the 1970s, starting in Germany and the USA, the contributions of women to music culture moved into the focus of interest. It turned out that women composers had been "buried in strange ways" in the past. At the first “Berlin Summer University for Women” in 1976, the arts were still largely absent. In 1979 the conductor Elke Mascha Blankenburg , together with other women involved in music, initiated the “ International Working Group on Women and Music ” , which quickly had around 100 members. "A new world of suppressed music history opened up". The international woman and music archive currently (2014) has around 20,000 media units, including works by 1,800 international female composers from the 9th to the 21st century. The Fondazione Adkins Chiti: Donne in Musica , based in Fiuggi (Latio, Italy), houses over 42,000 scores that are cataloged in cooperation with the Italian National Library. Surprising finds from historical music production by women and the results of a meticulous search for traces of the causes of oblivion led to the realization "that some chapters of music history must probably be rewritten and differently".

Musical tradition, as "cultural memory", was largely determined by male selection criteria until the 19th century. "Despite some ( transdisciplinary ) studies, the area of gender-sensitive memory and legacy research in the field of music history is still largely a research desideratum ." Both practicing and music-making musicians have been subject to situation-related clichés and traditional social disabilities for centuries . In addition, there is an imperfect tradition or reception . Although the woman playing music is documented in the oldest contemporary testimonies and the pictorial and literary testimonies of female music were never missing, traditional musicology did not comment on it. Musical life, which is still male today , was thus confirmed as "given by nature". The names of women composers are largely absent from recognized music histories.

As can be seen from European cultural history, the creativity of musicians , conductors and composers was opposed to cultural prejudices, economic restrictions and often malice. The way women conductors were still perceived in the late 20th century shows that they were viewed as “intruders” into a male domain and treated accordingly. “It only turns red at fortissimo” and the like could be read in the review headings after concerts with female conductors.

Since the end of the 20th century, there has been a noticeable rethinking of the artistic freedom of women in professional circles, but this has had little effect on the practical music business.

Music under the "Pauline Commandment"

Obstacles to female music making in Christian and Christianized countries arose through the interpretation of the so-called “ Pauline Commandment”. A passage from the text (1 Corinthians 14:34) was interpreted as the commandment of the Apostle Paul, which was translated as “Mulieres in ecclesiis taceant.” (“The women should be silent in your meetings. ”) On this basis, the participation of women - and thus their music making - was forbidden in Christian worship. Due to new research, for example regarding the project “Basic Bible”, this passage is translated in the singular: “This woman be silent in the congregation”, which does not wrongly mean all women. Other researchers suggest that the passage in 1 Corinthians 14.33b-36 was entered by an editor.

From the third century until the modern era, the prohibition that was passed on at that time was particularly effective in Catholic societies as a music-making ban for women, which indirectly also suppressed the secular practice of music by women and had an impact in non-Catholic communities.

The rejection of the female voice in the church strengthened the castrato character : In contrast to the physical integrity of the singer, the high castrato voice was considered the higher good, higher than the female voice. The choir of the Capella Sistina in Rome initially had falsettists perform for the high voices . The more artistic the music became, the more it was replaced by castrati, although castration , which gave boys the high-pitched voice, was officially forbidden. The women heard the singing in their own voices without having the chance of training in singing like the boys and young men in the cathedral schools .

The 18th century ( enlightenment and encyclopedists ) did not bring women liberation from compulsory roles and “self-inflicted immaturity” ( Kant ), but their role - “ children, kitchen, church ” - was consolidated as “given by nature”. The following passage from Karl Heinrich Heydenreich's book, The Private Educator in Families, How He Should Be, shows that this extended into pedagogy: I consider it to be the educator's duty to suppress the girl's aspiring genius and to prevent it in every way that it does not even notice the size of its facilities. (Double negative: “not”). An exception has always been those female musicians (mostly singers) who were admired as interpreters of the music made by men if they could meet the expectations of the courtly or middle-class music business. In this context, the famous Italian singer Signora Faustina Bordoni was literally announced in the London Journal of September 4, 1725 as the “rival” of the London diva Francesca Cuzzoni . For the first meeting in the opera Allessandro at the King's Theater , the composer Georg Friedrich Handel gave the “rivals” the same number of arias and the same vocal requirements, which did not correspond to the usual formal conventions of opera dramaturgy and fueled the rivalry. In the following year, the partisan, sensational audience incited the two artists alternately by partisan hissing or cheering on to a feud that was carried out on the stage (June 6, 1727). The satirical display (ie making the artists ridiculous) of this "famous" feud contributed to the great success of the so-called "Beggar Opera" by John Gay and Johann Christoph Pepusch - The Beggar's Opera - in 1728 .

White spot on the map of music history

The white spot on the map of music history formulated by Eva Rieger in women, music and male rule refers to neglected, marginalized creative, practical and theoretical shaping of musical life by women. A lexicon of European female instrumentalists of the 18th and 19th centuries, which includes around 700 hitherto little-known musicians (as of 2014), has been developed by the Sophie Drinker Institute in Bremen. This also includes music teachers and composers who mostly worked as professional instrumentalists (and vice versa).

The Répertoire International des Sources Musicales

The catalogs of the Répertoire International des Sources Musicales (RISM, International Repertoire of Musical Sources) contain printed works (Series A / I) and musical manuscripts (Series A / II) by a previously unknown number of female composers. In the RISM, the music repertoire (prints and manuscripts) that can be found in libraries , archives , monasteries , schools and private collections is recorded alphabetically by name (Series A) and systematically by work groups (Series B). Even if the period of European art music from the invention of sheet music printing (2nd half of the 15th century) can be illuminated relatively well, an undisputed number of female composers for this period has not yet been determined. RISM evaluations are scientifically discussed and published by specialized publishers. It is difficult to determine or estimate an approximate number of women composers because the usual search options can only find works by women composers who are already known by name (this also applies to composers).

Search for traces of early female music tradition

In the music of the "primitive peoples" there are no musicians in the specialized sense: all members of the tribe make music together. The music served mainly cultic purposes. Forty temple hymns have been passed down from the Entu priestess (high priestess) En-hedu-anna , who lived in the city of Ur in Mesopotamia in the 3rd millennium BC . Images from ancient Babylonian times on cylinder seals and terracotta reliefs depict women making music and dancing. Archaeological finds (mostly terracotta figurines) in the Syropalestinian region show that frame drums were played by women in this area. They (Hebrew tof ) belong to a secular (secular) song and dance tradition that Jewish women in Yemen continued until they emigrated. In ancient Greece the normal woman was socially subordinate, music was mainly cultivated by hetaerae . The philosopher Myja , the unknown daughter of Pythagoras , or Sappho , the well-known poet-musician, became known from the Classical Greek epoch in the sixth century BC . The poets Myrtis , Telesilla and Praxilla , all three from the fifth century, are named by Clemens M. Gruber as composers (unfortunately without citing evidence). The poet-composer Cai Wenji (177–250), who is still revered in China and whose compositions have been preserved, lived in the third century AD . The classical Persian music in (today's) Iran dates back to the 6-7. Century AD back. When, where and why misogyny emerged in music that explicitly excluded women in Christianity must remain open.

Rediscoveries from the women's monasteries

In the past and well beyond the Middle Ages , the women's convents were the most important places for women's education , in which independent female music developed by women. The chants in Byzantine notation of the monastery founder Kassia (around 810–865) are among the early testimonies to religious and secular music-making .

The monastery music by nuns has only been rediscovered today, for example works by Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179).

Linda Maria Koldau opened up the history of the music of the German-speaking women's monasteries that followed the Middle Ages and flourished despite all restrictions. Despite the word of Paul and supervision by the official church , the singing of the nuns , led by a cantrix , was the foundation of their services .

In the history of the north German monastery of the Cistercians in Wienhausen , paintings in the nuns' choir of the monastery church are interpreted as evidence of a rich historical instrumental practice, which is accordingly the location of the Wienhausen songbook . was already cultivated in the 14th century. Iconographic representations show women playing music with fiddles , lutes , flute , dulcimer and psaltery . In 1470 instrumental playing and secular singing were largely banned after a "violent monastery reform".

Especially "[...] in the north Italian women's monasteries (there was) an unbroken tradition of female composition activity since the middle of the 16th century":

- Vittoria Aleotti (1475 – after 1646, Ferrara)

- Caterina Assandra (around 1590 – after 1618, Milan),

- Faustina Borghi (? -? Modena),

- Sulpicia Cesis (1577 – after 1619, Modena),

- Claudia * Francesca Rusca (1593–1676, Milan)

- Chiara Margarita Cozzolani (1602–1676, Milan).

The Benedictine nuns showed a higher level of artistry than other orders. Vittoria Raffaella Aleotti (1575 – after 1646), a Benedictine nun who was also known in Germany in the 18th century , received her professional musical training when she entered the Benedictine Order of San Vito in Ferrara. As maestra di concerto of the high-quality performances of the Nuns of San Vito , which consisted of numerous participants , she already used a baton to conduct the instruments , which is a rarity in music history. The polyphonic printing of her Sacre cantiones à quinque, septem, octo, & decem vocibus decantande under her monastery name “Raffaella Aleotti” attests to a high level of choral practice.

Chiara Margarita Cozzolani (1602–1676) from the Benedictine convent of Santa Radegonda in Milan is one of the convent composers who became famous in the 20th century. Sound samples from her work on CD, such as those of her Marian Vespers, demonstrate a concert life that extends far beyond regional borders, similar to the girls' specials in Venice.

Isabella Leonarda (1620–1704) directed the music in the Novara Ursuline Convent. During her lifetime, 20 collections of her works were printed, which means that she can compete quantitatively with composers of her time. The instrumental music contained, as such (not text-related music) for a long time forbidden, suggests that it was also composed for non-monastic audiences, especially since Ursulines were not strictly obliged to attend the monastic enclosure.

Historical centers for female musical advancement

Ferrara

Several sources show that Ferrara has had a particularly high-quality women's music culture since the Renaissance, especially during the time of Duke Alfonso II .

The influence of the famous women's ensemble Concerto delle Donne had an impact in northern Italy as far as Bavaria. The singers created singing forms that led to the opera: madrigals, pantomimes, intermedia and balli (dances). They were in close contact with masters of the Florentine Camerata such as Giulio Caccini and Alessandro Striggio. The duke, who founded the “Academia dei Concordia” for court and city, had 32 musicians involved who united with the citizens of the city for joint concerts.

The composer and organist Vittoria Raffaella Aleotti already benefited from the high musical level at the Ferrareser Hof as a five-year-old when she was tutored by court musicians. She became a nun and prioress in the Benedictine monastery of San Vito in Ferrares, which itself was a famous musical venue. Your ensemble chants with up to ten voices, composed for this monastery, prove a high number of participants. The nuns there played wind and string instruments without restrictions.

Venice

Venice was a center for women musicians in the 17th and 18th centuries, although according to the papal prohibition women were not allowed to make music in church or “learn music”. The custom, which is unique in Italy, prevailed at the four Venetian girls' pedals to train girls and women in music and to regularly present their skills in public concerts. They performed as soloists, with orchestras, choirs and their own conductors. Her vocal and instrumental quality, reaching up to virtuosity, ensured an influx of interested parties internationally. Very few soloists are known by name, as they were only called by their first names, such as Anna Maria dal Violin , for whom her teacher Antonio Vivaldi wrote over 30 violin concertos.

The life of the girls in these original orphanages and hospitals was similar to a monastery. Since, in contrast to the boys of the Neapolitan Conservatoires, they “had no profession to learn”, they were trained in church music. Their concerts attracted the most famous masters as teachers. Nevertheless, their successes were not exemplary: in the rest of Italy and in the countries north of the Alps, even in Protestant parishes, women continued to be excluded from musical worship.

See also: Anna Bon di Venezia

Paris

Évrard Titon du Tillet (1677–1762) took in his book Parnasse françois, suivi des Remarques sur la poësie et la musique et sur l'excellence de ces deux beaux-arts avec des observations particulières sur la poësie et la musique françoise et sur nos spectacles (Paris, 1732) on French poets and musicians, whereby the relatively high number of musicians is striking, at least in relation to the German musicians in the "Lexicon" from the same year of Johann Gottfried Walther from Weimar , who otherwise lists quite a few musicians.

So it is not surprising that in France at the Conservatoire de Paris , founded in 1795, female musicians were able to study all subjects, something that was only possible a hundred years later in other European countries. However, there were apparently restrictions on female teachers, of which there were many: there were hardly any female professors. One of the few exceptions was Hélène de Montgeroult , whose name was explicitly “Professor of the men's class” for piano, which suggests that a distinction was made between male and female training.

Decrease in female musical performance

Male dominance in classical music life has developed over the centuries and is still present in the 21st century. Women were socialized away by “higher music”, their history ignored, forgotten by musicology. Regarding the music history of Greece, the “cradle of our culture”, Eva Weissweiler said in 1999: “The question of the creative achievement of women in the musical life of the Greeks has not yet been asked by musicology”. The traditional way of writing music history is described by Annette Kreuzinger-Herr as an “asymmetrical representation” in which the proportion of women remained a “voiceless” white spot “invisible fields of action”. The editors of the Lexicon Music and Gender, Kreuziger-Herr and Melanie Unseld, speak of a “capping” of the “diversity of the cultural landscape of music” by “men of action” who “determined the flow of the musical canon”.

In the 19th century, great composers were mainly attributed a status of genius by German scholars. The attendant attitudes that only men are predisposed to “creative” in music has been questioned and refuted by gender research. A lecture by Freia Hoffmann in 1980 to the “Woman and Music” working group entitled The Great Master and His Little Cook. How men made music history. - From the great master and her little cook. How women cannot make music history is the beginning of a reorientation. As early as 1976, Detlef Gojowy asked in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung “Can women compose?” To answer this with the counter-question “Will composing be a woman's job?”.

The role of the creative (ingenious) man in “excluding” women from the creative process, not only in music, is illustrated by the example of the young siblings Goethe and Cornelia (1750–1777), who destroyed his sister's texts even though he wrote to her had given the highest praise for it.

Uniform, consistent, socially generally accepted observations with which this historical development can be explained are hardly available. Even in popular literature such as the Lexicon The Famous Women of the World from A – Z published by Jean-Francois Chiappe (1931–2001) it is stated that no one has yet attempted to explain “the failure of noteworthy female composers”.

Devaluation and marginalization of women through musical and musical history tradition

In 1576, Orlando di Lasso's (1532–1594) polyphonic (polyphonic) collection of "beautiful, newer, German songs [...] which are not only lovely to sing, but can also be used on all sorts of instruments" was printed in Munich. These so-called " social songs" by the Bavarian court orchestra leader , whose musical art is famous, were widely used. But the negative statements contained therein, such as the following, had an effect on the social reputation of women through music and its reproduction (pressure), even if they were intended "only" as ironically intended song topoi - to be observed to this day in choir concerts and club parties.

"I poor man, what did I do? I've taken a wife, I hets well on the way [should not], I who still want to get, how often I've regretted it, I may judge that, I always have to go to bed in the hader stahn and also to eat. "

Whereby the last verse “I always have to be in a quarrel” is repeated and “Hader” is emphasized by a long melisma (ornament). In 1931 Hugo Riemann chose this song for his history of music in examples .

Apart from the retreat of musically talented women into the monastery, according to the evidence of recent musicology, many women were only able to publish their music under a foreign or male name, such as the baroque composer who has remained unknown to this day, who artistically worked in 1715 under the female pseudonym Mrs Philarmonica 24 published trio sonatas.

The first German music lexicon by Johann Gottfried Walther (Leipzig 1732) lists names of female composers such as “ Maddalena Casulana Mezari ”, “ Vittoria Raffaella Aleotti ”, “ Barbara Strozzi ”, “ Élisabeth Claude Jacquet de La Guerre ” and names practicing musicians like the violinist and Vivaldi's pupil “ Anna Maria dal Violin ” (1696–1782), the “ Violdagambist Dorothea vom Ried ” (* in the 1st third of the 17th century) and a large number of mostly Italian singers. The chances of doing further research on the basis of this data, however , were hardly taken by the great German post-war encyclopedia Music in the past and present , published from 1949.

Melanie Unseld writes about “the flood of abusive depictions of Constanze Mozart ” (1762–1842), the “estate administrator” of Mozart's works. Allegedly she “neglected” her husband's artistic estate. The portrait commissioned by her, on which she expressly and legibly holds “Oeuvres de Mozart” under her arm, has been changed in reproductions - “forged” - that this writing can no longer be read.

“Constanze Mozart is a particularly striking example of historiographical marginalization. The negative portrayal as an uneducated, greedy wife and widow has persisted. Hugo Riemann established this image, and Alfred Einstein , Wolfgang Hildesheimer as well as Heinz Gärtner and Francis Carr continued this, as did Miloš Forman's film Amadeus (1984), which is based on the play of the same name by Peter Shaffer . "

In the 19th and 20th In the 19th century, women were often described in biographical literature as a more or less suitable companion of genius, so that the complex of women and music was often negatively connoted from an unreflective point of view. Examples: Dieterich Buxtehude's daughter (? -?), Who is disparagingly described as an "old maid" and who is to be married by the father's successor as a condition to keep his position; Joseph Haydn's wife (? -?), Portrayed as disgust; Quantzen's wife (? -?), Of whom the King of Prussia allegedly feared. For none of these negative statements of the essayistic "embellishments" is a factual evidence to be read.

The situation of music in the Third Reich shows that women making music, if they could be used for ideological purposes or “abused”, gained popularity.

After the war, the successes of the Nazi era had to contribute even more to oblivion. In the middle of the 20th century, popular and academic literature commented on the lack of a female element in music as a woman's “musical under-talent”.

Even the most recent 5-volume Riemann Music Lexicon from 2012 shows large gaps with regard to well-known female composers, for example Maddalena Casulana Mezari , Vittoria Raffaella Aleotti , Chiara Margarita Cozzolani , Antonia Bembo (1640–1720), Élisabeth Claude Jacquet de La Guerre are missing , Mélanie Bonis , Johanna Kinkel , the American Gloria Coates, born in 1938, and many more. The baroque stage art of the singer and first diva in opera history, Faustina Bordoni - she took on the art of the castrati - was only commemorated with reference to the article by her husband Johann Adolph Hasse ; at the end of this, the only reference given is the biography of Saskia Maria Woyke .

Invention of the female composer problem

The alleged “female composer problem” (questioning the ability to compose) that has run through the entire history of music is a traditional fiction . In 1961 the President of the Academy for Music and Performing Arts - Mozarteum - Salzburg wrote:

“ The last question, whether a woman is allowed to look into the abyss that men like Beethoven did to be able to testify about the ultimate things, remains open. "

The female composers listed in the RISM - one of the most reliable records of musical works today - and their re-listed works prove that this is an invention with which condescension and ignorance have been justified over and over again for centuries. Women themselves internalized this attitude against their own inner security, as is well known the pianist and composer Clara Schumann . Or “man” (Frankfurter Zeitung of April 11, 1943) put into their mouths: “We women don't compose… There must be something that we lack”.

In earlier times, composing was, of course, part of making music and part of the service contract, as can still be seen in the example of the Esterhazian conductor Joseph Haydn . To be Kapellmeister of a princely court or a parish, like the nun and maestra di Concerto Vittoria Raffaella Aleotti , meant practically fulfilling the demand for “new” music with the available musicians. Haydn composed for the stage and for the private baryton lover of his prince, Aleotti for the service in her Ferrares convent.

The commonality of making music was masked by the (male) genius cult in the 19th century. In the well-known scientific series of early music, " Monuments of the Art of Music ", created in the same century, no works by female composers are represented.

A woman's musical work was mostly reduced to her appearance, her physicality, her appearance. In the first German musical post-war encyclopedia Music in History and the Present (MGG 1), the success of the composer, singer and lutenist Maddalena Casulana Mezari (1544? -?) "Primarily with her ability as an (optical) performing artist" [400 years ago] explains, and her compositions, a woman's first musical prints, are only given two sentences.

Although Fanny Hensel had received just as qualified musical training, including composition lessons, as her younger brother Felix Mendelssohn , her father wrote to the adolescents in his infamous letter that for her music should "always be an ornament, never the basis" of her "being and doing" his, and it culminates in an appeal to their good nature and reason, because "only the feminine adorns women". In this way the “basic basis of being a woman” is reduced to an “ornament”.

Music by women was perceived differently by society than that of men. Proof of this is the popularity of the Concertino for flute and orchestra by Chaminade - the common title - due to the concealment of the composer's first name (Cécile) . When they appear, modern women conductors are more interested in their appearance than in their performance of interpretation: Die Welt wrote stiletto pumps for Sydney Opera on their report on Simone Young's (* 1961) inaugural concert in Sydney .

Women's movement in music

Soon after World War II , the American Sophie Drinker (1888–1967) published her seminal book Music and women: the story of women in their relation to music (1948), followed by translation into German as Die Frau in der Musik. A sociological study. (1955). She is therefore considered to be the initiator of musicological research on women.

Since the 1980s, "Hundreds of dissertations on women composing from past and present, America, Europe" have been written in America. Eva Weissweiler explains this situation with the fact that American music history is more recent, "and that also means: it is less burdened by male heroes than European history".

The British composer Ethel Smyth (1858–1944) continued the centuries-long struggle for a fair musical gender balance in Europe through music, words and deeds. Her life was largely shaped by first studying music with her father and then establishing herself as a composer. She worked as a writer and campaigner for the suffragette movement in her home country. She created an extensive musical oeuvre, of which her opera The Wreckers ("Strandrecht") achieved the greatest success. It was performed many times under conductors such as Sir Thomas Beecham and Artur Nikisch . Her The March of Women , an anthem of the English women's movement, became popular .

German pioneers

1981: Two groundbreaking books

In 1981 Eva Rieger and Eva Weissweiler put musical feminism on a promising foundation with two new releases. Eva Rieger, by bringing up the structures of social disabilities for women making music, as they were expressed in Germany, and Eva Weissweiler with the first international female music history. Both books were reissued in 1988 and 1999, respectively, and on that occasion included an experience report on their inclusion and further developments in the meantime. Eva Rieger reaped with her provocative title woman, music and male rule. initially by no means just consent. She posed the provocative question “What kind of 'general human culture' was that continually revolving around men?” In the introduction (1981), Rieger considered that the consequences of a “centuries-long ban on creativity” for women “cannot and cannot be negated” that in the case of the “female cultural heritage” one has to take into account its traditional dependence on the “invisible ideological chains” of the female sex when asking about the missing “female Beethoven”. Eva Weissweiler regrets that the composers have secured their place in the composing scene, but:

"It is astonishing and sad how many female composers, especially in Europe, defiantly confess to the 'tradition' created by men and almost aggressively reject the idea of creative counter-concepts."

Eva Rieger speaks of the "hitherto neglected phenomenon" of "sexist structures" (1981) "with regard to the much touted 'humane statement' of cultural music".

Eva Weissweiler's first German-speaking female composer story, women composers from 500 years, was just as groundbreaking as Rieger's wife, music and male rule. Although the author had grown up practicing music, among other things as a “ Jugend musiziert ” award winner, and although musicology was a major subject of her studies, she had “never heard of a woman composing” before her doctorate in 1974. As a radio editor for “Symphonie und Oper” she began to “secretly” replace the “men's compositions broadcast year in and year out by the public broadcaster” with works by female composers as soon as she came across them in the file boxes: Lili Boulanger , Germaine Tailleferre , Clara Schumann , Grażyna Bacewicz .

More on the topic

Freia Hoffmann analyzes the more or less covertly sexist motivated backgrounds of patriarchal society in the bourgeois age when it came to relegating women to their proper limits when performing music. The author describes a review from 1825 in the Berliner Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung (pages 16–28) of eight organ fugues by a composer: It is a “five columns” appraisal of Mariane Stecher, which addresses the “sublime” and “difficult “Daring to art of fugue composition. The “appropriately irritated” reviewer Ludwig Rellstab , at that time “the most prominent music critic in Berlin”, compares “composing with 'agriculture' and fugue writing with 'working on a rocky ground through which the ploughshare has to be led with annoying manly arms when the The reason is to be churned up and fertilized to the depths' ". Hoffmann then continues that “Mariane” was a misprint, and that the composer was actually the Benedictine monk “Marian o Stecher” (born around 1760), whose eight organ fugues then under their real name, after the mistake was discovered, one received positive and factual criticism from another reviewer.

Women & Music, a History (1991), edited by Karin Pendle , is the somewhat later American counterpart to Eva Weissweiler's composers from 800 years from 1981/1999.

Views of feminist musicologists

American musicologist Jane Bowers ponders whether the “neglect of female concerns” in musicology is “a result of sheer negligence”. She goes on to say that this "practice perpetuated the myth of feminine triviality."

Despite the writings of Friedel, Hoffmann, Koldau, Rieger, Weissweiler and many other scientists, little has changed in “normal” musical life. There was no real reaction in musical life, as Weissweiler wrote in the foreword to the second edition of her female music history in 1999:

"The exclusion of women historical composers from the concert repertoire [has remained almost as constant since the first publication of this book [1981] in 1999, as has the astonishing ignorance of many experts."

According to Eva Rieger 1988 and Eva Weissweiler 1999, "[German] musicology has a patriarchal (Weissweiler:" arch-patriarchal ") basic structure, which is expressed here more than in other sciences."

Rieger closes her, according to Weissweiler, “fundamental music-sociological analysis” of woman music and male rule with Chapter V: The search for aesthetic self-determination. Weissweiler's last chapter also revolves around the search for an original female musical language: In search of a language of her own.

Festivals, exhibitions, bibliographies

A series of regular female composers festivals has been established since the 1980s for the last women composers movement. There have been international competitions for women composers since 1950. Exhibitions with sheet music by women composers were organized on a smaller and larger scale. As early as 1971 in the Munich State Library: women composers from three centuries. With the international series of festivals in Kassel in 1987 (February) and Heidelberg (June) the pioneering work that was started was underpinned with accompanying publications.

“Special festivals (Hamburg, Heidelberg, Kassel, Cologne, Mannheim) are still necessary to make women composers heard. Who would ever have to emphasize the composing man like that? The expression of composing as a 'man's thing', as Richard Strauss put it, was for centuries so ostensibly a matter of course that it became the categorical imperative of patriarchal society for centuries. "

One reads further about the “performance paralyzing” condition in Germany and the “mistrust hurdle”, which is greater for the German composers than for their colleagues from countries with a “younger musical tradition” such as North and South America, Romania, Korea. However, there were political hurdles in Romania to take part in the German women composers festival. For example, Die Welt reported on June 3, 1987, No. 127, Culture: No departure for Miriam Marbé. The Romanian composer was not allowed to take part in the Heidelberg Festival in 1986 or in 1987 in order to receive the Heidelberg Composition Prize that had been awarded to her.

"Apparently it is no longer so much the husbands and brothers who block the composer's path as the functionaries."

In addition to catalogs on editions of works and publishers by / for female composers, more and more bibliographies of the literature on the subject, which has since grown, appeared in the 1990s: book index Woman and Music 1800–1993, Woman and music. A selective annotated bibliography, woman and music. Bibliography 1970–1996, BIS Verlag of the Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg published Musik Frauen Gender in 2006 , book directory 1780 to 2004, which now includes over 4,400 titles.

"In search of your own language"

As Eva Weissweiler describes, there were very progressive developments in America as early as the middle of the 20th century with regard to the “search for their own language” by women who “deliberately set themselves apart from the myth of the male genius” ( Meredith Monk , Pauline Oliveros, etc. .). The creative involvement there with the medium of music led to a holistic kind of “performance and improvisation ” with “singing, doing gymnastics and dancing” on stage.

In Germany, the violinist, a student of Hindemith and Carl-Flesch , Lilli Friedemann , began to experiment with musical group improvisation in the 1960s, which she said was initially inspired by historical dance music. Their “collective improvisations” were less spectacular than the American performances, which Weissweiler described as “musical productions”. Two important elements predominated in Friedemann: that of listening and that of reacting to one another.

Ruth Schönthal (1924–2006, also Schonthal) composed “From the diary of a woman”, in which she was inspired by the “ambiguity of feelings” in the face of “indoctrination (children, kitchen, church)” of a young girl “full of enthusiasm and tenderness ”. Judith Förner stated in 2000 after extensive literature research that there was no musical training concept for girls from a gender-specific point of view, especially in adolescence, the years for setting the course for a career.

The importance of women for francophone chanson

In October 1996 a database project on the Francophone women's chanson was founded at the Institute for Romance Studies at the University of Innsbruck with the aim of scientifically investigating the meaning of the female chanson . Despite its centuries-old tradition, popularity and social relevance, the chanson only found its way into science as a “second class” genre in the 1960s. A so-called “bourgeois” understanding of art favored the double discrimination of women who ventured into this area as lyricists, composers and / or interpreters - on the one hand, as artists who largely remained unnoticed by research, but also by the media others as representatives of a genre belonging to a subordinate status. Exceptions were artists such as Édith Piaf , Juliette Gréco , Barbara and also Anne Sylvestre as representatives of the first generation, who still have a permanent place in the collective memory today. To counteract this tendency to select and to close gaps, the research project “Database Frauenchanson. History and topicality of the francophone women's chanson in the 19th and 20th centuries ”(for the countries France, Africa, Belgium, Canada and Switzerland) made it their task, and together with the Innsbruck Documentation and Research Center for Text Music in Romania, there were over 6000 recordings archive and build up a specialist library with more than 2500 publications on the subject of Romance text music.

Music performance artists in the USA

In 1999 Weissweiler describes the holistic multimedia sound art of its inventors in America at the turn of the century in “In search of a language of their own”.

Of the seventeen female composers on the American music scene listed by the American composer and music critic Kyle Gann and later Weissweiler, several have been listed in the latest German music dictionary, Riemann 2012.

Doris Hays was inspired in 1981 for her avant-garde, multimedia performance Celebration of NO by the film Die Bleierne Zeit by Margarethe von Trotta . Celebration of NO was discussed extensively and controversially in America and Germany. Eva Weissweiler describes how Hays uses the word “No”, which she recorded on sound carriers - spoken by women in many languages, even Indian - and defense sounds (warning screams) from animals for this performance. Doris Hays herself published in 1992 in MusikTexte 44: Celebration of NO, The woman in my music.

According to Weissweiler, Meredith Monk (* 1942) is a “particular favorite of feminists”, “because she strongly emphasizes the feminine” in her music. These include "lullabies and wedding songs, lamentations for the dead and ecstatic-meditative chants that have been largely suppressed by Western European Christianity". On behalf of the Houston (Texas) Grand Opera , she wrote a "Sing-Dance-Drama" about the giant atlas that carries the globe. She says: "Words are only obstacles that have to be translated" and "Back to the roots, back to the body, to the heartbeat or to the blood". Weissweiler literally counts her as one of the new female magicians on stage who “cast a spell over their audience with the simplest means”. Other American artists include Pauline Oliveros (* 1932), Laurie Anderson (* 1947) and Diamanda Galás (* 1955).

Music as an autonomous way of life for women

Historical career prospects

At European princely courts of the Renaissance, virtuoso singers were able to turn their art into a profession: the Italian singers of the Concerto delle dame di Ferrara were among the first professional virtuosos whose names have been handed down to this day . They received the status of ladies-in-waiting of the Duchess Margherita Gonzaga. Their employer, Duke Alfonso II. D'Este , tried to get them married in order to counter the danger of being seen as a courtesan .

The bourgeois Venetian baroque composer and singer Barbara Strozzi was never married and is perhaps therefore repeatedly referred to in literature as the “ courtisane ”. She published eight books of vocals, which she read in the house of her (adoptive) father, the intellectual Giulio Strozzi , at the events of the " Accademia degli Unisoni ", which he founded . This is remarkable in that academies were taboo for women at the time.

The chance for a pre-vocational musical education practically only arose for girls from musical families, such as the viol virtuoso Dorothea vom Ried . She was brought up by her father with her three sisters and two brothers to form an ensemble that, despite the ongoing Thirty Years' War , toured Europe in concerts. Things were completely different in the musician family of Johann Sebastian Bach , who raised five sons for the musical profession, but not his daughters.

Born into a family of musicians, the French composer Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre , like her three siblings, who also became professional musicians, received music lessons from her father. After Louis XIV noticed the achievements of the five-year-olds, she enjoyed an aristocratic upbringing at the royal court. After her marriage, she lived as a freelance virtuoso , composer and teacher. Even after the death of her husband, she was able to live in prosperity from the income from her compositions. Her opera Cephal et Procris in 1694 was the first by a (female) composer to be performed at the Académie royale de musique in Paris.

Female creativity under or without sexist prejudice or economic restrictions

The danger for unmarried female musicians of being attributed to prostitution already existed in ancient times. In his music lexicon of 1732, Johann Gottfried Walther names the Ambubajae , “certain women” from Syria who came to Rome, where they

“Played on different instruments and thereby attracted young guys, which is why they did not live in much 'prestige'. They stayed particularly in Circo, the baths and other places where it was funny. "

From the southern German “frouwe”, “maidlin” or “virgins” numerous testimonies of paid musical services as singers or “ Lautnslagerinnen ” have been preserved between 1420 and 1574 . Their names remained mostly unknown, as well as details about their education and how far their independence went, or whether they were married or not.

Daughters of aristocratic circles were usually given an education that encouraged serious music practice, such as that of Heinrich Schütz's pupil Sophie Elisabeth von Braunschweig , whose Singspiel Newly Invented Peace Game genandt Peace Victory of 1642 (printed 1648, at the end of the 30 year old War) is the earliest surviving music-theatrical German work.

In their autonomy, however, women of the high nobility were fundamentally dependent on their husbands, father or brother. Princesses in Germany were inherently disadvantaged compared to their brothers. Wilhelmine von Bayreuth, in particular , felt the effects of the waiver she demanded at the wedding in the course of her Bayreuth opera direction, whose ambitious plans she was only able to implement on the back burner due to a lack of financial resources and powers.

With her opera L ' Argenore , she set a sign of rebellion against the tutelage of absolutist royalty: the main character, King Argenore (who is discussed as Wilhelmine's father after Ruth Müller-Lindenberg), takes his own life on the open stage in the last scene This is what Wilhelmine envisages in her textbook. This was an unheard-of act in the time of absolutism, because the main concern of the courtly opera genre was to glorify absolutism, which included the “ Lieto fine ” convention on the stage . The controversial discussions about this opera have continued since it was performed at Erlangen University in 1993.

There were very positive female lives in the aristocracy with regard to music: Maria Antonia Walpurgis of Saxony (1724–1780), Empress Maria Theresia and Anna Amalia von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel (1739–1807) had as regent representatives or educational leaders the underage sons / rulers the opportunity to implement their musical ideas.

Women in professions for music

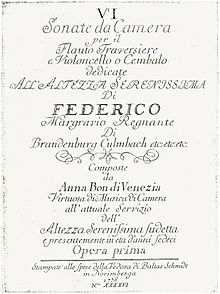

Women in music printing is the title of Linda Maria Koldau's overview of numerous, previously unknown female music publishers in Germany in the 16th and 17th centuries. The Nuremberg publisher Johann Balthasar Schmidt's widow , whose name was not known, took over the publishing house of her deceased husband, in which Johann Sebastian Bach and his son Carl Philipp Emanuel had published important musical works. She signed with "alle spese della Vedova di Baltas: Schmidt" (at the expense of Balthasar Schmidt's widow).

The piano maker and pianist Nannette Streicher (1769–1833), daughter of the famous Augsburg piano maker Johann Andreas Stein, trained in her father's workshop . She started her own business in Vienna , where she invented new technical construction methods. Their pianos and grand pianos are among the sought-after rarities today.

Claudia Schweitzer brings to life the social circumstances of piano teachers from the 17th to the beginning of the 19th century in France, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany and Austria. This international research shows that the teachers and artists often came from families of musicians. They were able to live on their own earnings, and some of them published piano schools, such as Hélène de Montgeroult (1764–1836). According to the current state of knowledge (2014) she was the first employed piano professor at a conservatory , a vocational training facility. She was part of the first teaching college of the Conservatoire de Paris, which was newly founded in 1795 .

This shows the other side of musical life, that of education , the large part of which has been in the hands of women for centuries.

The song composer Louise Reichardt (1779–1836) was one of the initiators of the Hamburger Singverein in 1816 , which made outstanding contributions to the performance of Georg Friedrich Handel's oratorios . She founded and directed her own “choir club” and organized “spiritual” music festivals in Hamburg and Lübeck.

Musical vocational training in Germany today

When it comes to choosing a musical vocational training facility, there are many options for women today, both in the classical and pop fields. They range from practical music - the traditional occupations orchestral musician, singer, conductor - to composer and educational subjects music teacher / school musician, teacher of music education , rhythmist , music therapist and musicologist, music journalist, music critic, a sound engineer , instrument maker, publishing director . Most professions are organized in associations. There are no longer any reservations about instrument choice among women. However, the prospects for professorships and chairs at universities are still not very promising.

Vocational schools, technical academies, conservatories, colleges and universities for music are distributed all over the Federal Republic: the umbrella organization is the German Music Council ; the Neue Musikzeitung of Gustav Bosse Verlag represents all German associations and activities.

Lay and youth education music school

The German Music School Congress , which takes place every two years in different cities, presents interested teachers with musical activities related to the musical training of laypeople in workshops, lectures and exhibitions. It is carried out by the Association of German Music Schools , or "VdM" for short, and funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research . Illustrated program books of the events are published for each event. The last congress (as of 2014) took place in April 2013 under the motto Fascination Music School .

With a great variety of events and activities, the carefully compiled program book documents a surplus of male speakers , an almost exclusively male committee of the VdM federal board, but a clear surplus of women in the federal and state parent representatives (p. 134 ff).

A disproportionately large number of women are involved in music theater , expressive dance and also in choral singing . They also started some annual music weeks , in Austria for example in Carinthia and in Traunstein .

Music with disabled people

For over 15 years, music has been officially made with disabled people at German music schools. A field report from teachers who have dealt with it was published about this work with a newly practiced approach.

"Motto of Prof. Dr. Werner Probst: Everyone is capable of experiencing and producing music, and in this sense musically. This musicality and thus every musical system can be developed. "

Of the practical contributions contained in this volume, the number of female speakers is only slightly below the number of (male) speakers.

Composer as a profession, historically

Being a composer was a natural part of life as a musician back in the Baroque era . If a woman gained recognition as a composer - early examples of this are shown by Johann Gottfried Walther's Musik Lexikon from 1732 - the chance that her name would “survive” until the first major German post-war encyclopedia “MGG” was slim. Eva Weissweiler speaks of the "widespread lack of articles about female composers or their malicious, sexist (r) dismissal". The invention of printing music gave women composers a public forum, which they had to defend from men. The Renaissance composer Maddalena Casulana Mezari formulated in the first (known) musical print of a woman that it was a “foolish error of men” to believe “that they alone are the masters of high intellectual abilities”.

Barbara Strozzi , her future colleague in Venice, worried in the foreword of her Primo Libri de Madrigali (Venice 1644) about the "flashes of the prepared calumnies" [of the men's world].

Only two female composers were accepted by the renowned Accademia Filarmonica in Bologna: Marianna Martinez (1744–1812) and Maria Rosa Coccia (1759–1833). To be a member of this composers' association meant to have the privilege to publish your own works. In contrast, the Accademia dell'Arcadia in Rome, which made outstanding contributions to the opera libretto, also had female members, including the Prussian Princess Wilhelmine of Bayreuth and the Saxon Electress Maria Antonia Walpurgis (1724–1780). What is known about the whereabouts of the compositions of Margravine Wilhelmine von Bayreuth , or her large collection of music, is that the latter was saved, but it has not yet been found. According to Otto Veh's interpretation, after her death in 1758, attempts were made to stop any memory of Wilhelmine because of her political influence on her favorite brother Friedrich the Great. For comparison: Frederick the Great has composed over 120 flute sonatas in close contact with her since his time as Crown Prince, all of which were distributed to his castles and played there during his lifetime by copyists' copies. The Bach biographer Philipp Spitta numbered them, provided them with an incipit index (thematic index) and published them at the end of the 19th century in the 4-volume splendid edition of Frederick the Great's musical works together with his other compositions. In contrast, individual compositions by Wilhelmine von Bayreuth only appeared at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, scattered at locations far apart.

Men and women equally disregarded female composers. Alma Mahler and Fanny Hensel describe how it “feels” to compose, but not to be allowed to. In both of them, the emotional implications of what the "prohibition of creativity" meant for the creative musician:

"If no rooster crows at me [and:] in the end, even with the pleasure of such things, one loses judgment about it, if a foreign judgment, a foreign benevolence is never opposed"

Both life stories are examples of how female self-confidence and creativity have been burdened by social norms and traditional gender theories. The paradox of Alma Mahler is that although she was extraordinarily emancipated and knew how to assert her interests in a targeted manner to her advantage, she still stopped composing.

Composer as a profession, international

The International Alliance for Women in Music (IAWM) is a global organization that supports activities by women in music, particularly composing, performing and researching in areas where gender discrimination is a historical or present day concern. The IAWM is committed to the discrimination of female musicians in orchestras and advocates the publication of contributions by female musicians in the university sector.

Women composers festivals are a rarity. The International Festival of Women Composers Yesterday-Today in Heidelberg was held for the first time in 1985.

Testimonials

- The English composer Elisabeth Lutyens (1906–1983) composed twelve-tone music without knowing about Arnold Schönberg's twelve-tone technique :

"Oh - did Schoenberg use the twelve-tone method too?"

- Gloria Coates (* 1938), American composer:

"[...] whatever I invent, it is my very sincere search for the truth, and that the music comes from hidden parts of myself, both emotionally and intellectually."

- As a child, the Romanian Violeta Dinescu (* 1953) felt fascinated by sounds like those of a cat running over the piano. She says about composing:

“In the beginning of every composition I try to find a justification for the organization of the musical material by constantly looking for a sphere, an idea where the flood of fantasy meets the rigor of the form-creating thought. For me, composing is a structure of life, something that pervades my entire life. "

- The Romanian Adriana Hölszky (* 1953):

“I do it like a sculptor, take the material and try it, and then a shape matures. Sometimes things come about that I didn't even suspect at the beginning. "

Modern and contemporary composer in the German-speaking area

In 1989 the documentary Die Frau in der Musik, directed by Leni Neuschwander , was published, in which the international competitions for female composers 1950–1989 are recorded and evaluated. Illustrated portraits of female composers and a register show well over five hundred contemporary female composers from over 30 countries around the world.

It took a long time after World War II for women composers to be noticed. As recently as 1973, Reclam's piano music guide said that Poland had not produced any composers who “achieved world fame” alongside or after Fréderic Chopin. The “legendary symbolic figure of the middle Polish generation of women composers”, Grażyna Bacewicz , was left out, but in 1973 she got her own article in supplement volume 15 of MGG I. Confessing to an authentic personal musical language was a fight against discrimination for women composers.

Even if in 1999 the historical female composers hardly had their say in public music life, even if a professor was only given a chair for women's music research at a German music academy in 1998 (Dortmund), it cannot be overlooked that the modern female composers are self-confident claim the international sites from Donaueschingen to Warsaw. In North America around this time, half of the composition students are women.

The composer Brigitta Muntendorf , born in 1982, received the coveted Siemens Music Prize in 2014.

Testimonials

- Ruth Schönthal (1924-2006) from Hamburg :

“In my family I have not been burdened with complexes such that women are not artistically and intellectually equal to men. On the contrary: my parents wanted a composer in and always supported me very much "

When Schönthal was asked whether her composition “From the diary of a woman” was related to her work as second chairwoman of the American Association of Women Composers, she replied:

“No, not with my work in the Association of Women Composers, but with my special sensitivities, feelings and experiences as a wife and friend of women. The piano piece 'From the diary of a woman' describes the life of women as I know them, with their joys, pains and problems. It shows indoctrination, i.e. H. Children, kitchen, church and a young girl full of enthusiasm and tenderness; [...] "

She worked out the ambiguity of feelings “in a wedding march that is also a funeral march” and - as a further example - had a waltz in the right hand and a foxtrot in the left hand meet with their rhythmic overlays. "In general, my music isn't just about women, it's about music and the human element."

- The Austrian-Swiss composer Patricia Jünger (* 1951) comments on her profession:

“You really have to be stupid enough to believe that you can make a living from it (from composing). [...] Well, the phenomenon of music seems like a mystery to me. But - one thing is just wrong: when I pick up a sound, it's like a sculptor touches sand: a material that I can touch. It's not something that runs around dematerialized. "

Female UFA stars

Although Nazism was widely touted the role of "comrade", "sufferer" and multiple parent for women (see also Women in National Socialism ), remained the UFA - entertainment film almost free from these stereotypes. In fact, women played an unusual and important role for that time. They appeared strong, mysterious, or clever. They often bailed the men out and where they hesitated, they confidently made the right decisions. Some of them led surprisingly independent lives, and even when they submitted, the action revolved around them. In addition to these complex, interesting personalities, the men often looked like shadows. The female stars of that time included Zarah Leander , Marika Rökk and Ilse Werner . They not only acted as actresses, but also as interpreters in musical entertainment such as dance or revue films .

As one of the best-known examples, the Swede Zarah Leander developed into the highest paid film actress and singer in Germany within a few years, where she also appeared in operettas and musicals . Her best-known films were made between 1937 and 1943: To new shores , La Habanera (both 1937), Heimat (1938), It was a glittering ball night (1939 together with Marika Rökk), The great love (1942) or Damals (1943). With her succinct alto voice she fascinated and irritated the critics alike. Although she supported the perseverance slogans with hits like The World Will Not End (after heavy bombing raids on German cities) or the hope for the “ miracle weapon ” with I know, a miracle will one day happen , she felt like them other stars, as completely apolitical.

The German-Austrian operetta legend Marika Rökk received training as a dancer at an early age and went on tour through Europe and America before she was discovered by the UFA. Films like Gasparone (1937) and Hallo Janine (1939) were among her greatest successes during this period . Film hits like music, music, music (I don't need millions) became evergreens . Since she was one of the leading stars among the National Socialists, she was banned from performing in the first few years after the war. In the 1950s, she continued her career in, often American-influenced, music films. In 1962 she withdrew from film and switched to the stage, where she appeared in various operettas and musicals. In 1992, at the age of 79, on the occasion of Emmerich Kálmán's 110th birthday, she made another stage comeback in Budapest as Countess Mariza .

Ilse Werner, born in Batavia , became known for her songs and her whistling skills . It was the epitome of cheerful, sophisticated entertainment. The graduate of the well-known Max Reinhardt Seminar became famous with films such as Wunschkonzert (1940), the Jenny Lind epic The Swedish Nightingale (1941), We Make Music (1942), Great Freedom No. 7 and Münchhausen (both 1943). She too was temporarily banned from working, but returned to the stage in 1950 with The Disturbed Wedding Night . In the 1970s she succeeded with the piece we are once again escaped from Thornton Wilder of change to character roles. In addition, Ilse Werner was involved as a show and talk host as well as in various television roles.

African American singers

Bessie Smith (1894–1937), Josephine Baker (1906–1975, also a dancer), the gospel singer Mahalia Jacksons (1911–1972), who appeared in Germany in protest against discrimination against African-Americans. Ella Fitzgerald (1917–1996), Sarah Vaughan , Billie Holiday , Nina Simone (1933–2003, also songwriter), Tina Turner (* 1939), Aretha Franklin (1942–2018), Joan Armatrading (* 1950, also songwriter), Tracy Chapman (* 1964, also a songwriter).

Bands, popular music, "music scene"

In the popular music scene, male bands predominate over female bands. Judith Förner puts this deficit in women in connection with traditional habits in the school program for bringing up girls. In contrast, the list of renowned solo pop singers of our time is long. The most commercially successful singers of the past 50 years have been Madonna , Mariah Carey , Celine Dion , Whitney Houston and Barbra Streisand . In the Billboard chart ranking for the years 1992 to 2012, female pop soloists took 13 of the top 20 places, led by Rihanna , Pink and Britney Spears , while only two male soloists were represented.

See also: Polish singers in the competition "Fryderyk" ("Singer of the Year" since 1994)

Conductors

See Elke Mascha Blankenburg: Female conductors in the 20th century, portraits from Marin Alsop to Simone Young.

The author, herself a conductor, begins her introduction with a quote from the French conductor and composer as well as conducting and composition teacher Nadia Boulanger (1887–1979). When asked how she felt “as a woman at the desk”, she replied, “When I get up to conduct, I don't think about whether I am a woman or a man. I do my job. ”Ms. Blankenburg continues that even today (2003) this is one of the first questions that conductors are asked. In reviews after the concert, only the description of the evening gown of the woman at the desk instead of the content of the musical interpretation would be particularly frequent and happy. Such remarks became known in connection with the first internationally known German female conductor of the 20th century, Hortense von Gelmini : “Symphony in blonde”, “It only becomes red at fortissimo”, or the verbal derailment “If she would conduct at least naked”.

According to Blankenburg, the fact that there have always been female conductors has never been researched. Vittoria Raffaella Aleotti from Ferrara conducted with a baton as early as the 16th century. Sophie Charlotte , the first queen in Prussia, conducted Italian operas from the harpsichord. Fanny Hensel conducted the Sunday music in Berlin. And many female musicians did it in a similar way without the music history taking notice.

In 2002 there are 76 opera houses in Germany that are regularly used; of the 76 music directors, only two are women. As you can read on with Mascha-Blankenburg, there are a further 34 independent symphony orchestras for concerts in Germany; Of the permanent conductors, only one (0.5%) is female. In this context, the proportion of women as musicians in the orchestra should be mentioned. The Berliner Philharmoniker played 100 years without women until Madeleine Caruzzo came along, the scandal followed with the engagement of the second, clarinetist Sabine Meyer. 120 men argued about a woman.

There were conductors and women's orchestras in the USA as early as 1935, in Germany Hortense von Gelmini , Elke Mascha Blankenburg , the Hamburg general music director Simone Young , and others became known.

Soloists

While musical boys were selected and trained in the church scholas according to a centuries-old tradition, particularly fortunate circumstances had to come together for a successful solo (vocal or instrumental) career with girls. The best trained musicians were castrati, besides singing they also learned the theory, instrument and composition thoroughly. The same was possible at the Venetian girls' pedals, despite the Vatican prohibition. As the opera established itself and the instruments became more and more virtuoso, soloists could grow up due to the early lessons.

Vittoria Raffaella Aleotti had the fortune of a music-loving father who gave his daughters music lessons from childhood, when she became a famous organist. The gambist Dorothea vom Ried , an Austrian “child prodigy” from a traveling, concert-giving virtuoso family, is an example of how her family promoted talent in the mid-17th century. 100 years later that would have been questionable. It was sung about by the Weimar poet Georg Neumark during his lifetime .

The first internationally known violin soloist was Anna Maria dal Violin , for whom her teacher Antonio Vivaldi wrote 31 violin concertos at the Venetian Ospedale della Pietà . The Venetian Faustina Bordoni , who is known today as the “first prima donna ” of the baroque opera stage , was fortunate enough to be sponsored by the Marcello family of patrons. She was in no way inferior to the best castrato singers.

Maddalena Lombardini Sirmen was trained as a singer and violinist at the Ospedale in Venice. A special privilege to study violin with Tartini in Padua enabled her to use a modern violin technique and today's musicology a fundamental treatise of his violin technique in the form of a letter to his pupil. Her concert tours took her to Faenza, Turin, London, Paris, Dresden and St. Petersburg, where she performed her own compositions. From the wealth of her concert experience, she composed violin concertos and string chamber music. Her quartet compositions were printed in Paris at the same time as the quartets op. 9 by Joseph Haydn; both are considered pioneering work. As a woman, Sirmen did not have the opportunity to consider an orchestral position, which is probably why she changed saddles and became a singer on the opera stage. This was only possible because of her varied and comprehensive training at the Ospedale dei Mendicanti in Venice.

Instrumentalists

The variety of instruments played by women in the Middle Ages declined in the centuries that followed. A series of renaissance copperplate engravings by Tobias Stimmer (1539–1584) shows women still with all imaginable instruments. An example of uninterrupted music-making is the organ-playing, composing and conducting nun Vittoria Raffaella Aleotti in Ferrara.

As Freia Hoffmann explains, women in the bourgeois age grew restricted in making instrumental music for reasons of “propriety”, especially the organ, the cello and the viol, the instruments that had to do with footwork.

Mozart's talented sister Anna Maria, known as “Nannerl”, was not allowed to sit on the organ bench like her brother Wolfgang, nor did she take composition lessons like this one. There was no town pipe or orchestra position for women . It took a long time before girls and women were allowed to learn their instruments professionally and even study at a music college. The Conservatoire de Paris , founded in 1795, was the first after the era of the Venetian ospedali to allow women to take part in all musical subjects without restriction.

For a long time, wind and percussion instruments were particularly unsuitable for women. Ultimately, the piano became extremely popular and this instrument became a dilettante. Hoffmann reports that of around 600 instrumentalists known by name in Germany between 1750 and 1850, 90 percent adhered to the "permitted" instruments piano, plucked instruments, especially harp, and glass harmonica .

A modern example of long-standing misogyny in the orchestra is the professional history of the clarinetist Sabine Meyer .

The girl at the piano, an international "cliché"

At the beginning of the 20th century, playing the Japanese koto was still part of the educational canon of Japanese youth. When the family began to consolidate in Japan at the end of the 19th century, with the man as the sole breadwinner, a gender-specific upbringing of children developed hand in hand with it. At the same time, Japan oriented itself more towards western musical culture, with the national instrument koto being supplanted by the European piano. The piano became the daughters' instrument and home gathering point for the modern Japanese middle class family.

At the same time, the Japanese piano production Yamaha began . This was followed by the incorporation of European musical life into other Asian countries, as well as piano manufacturing in Korea. This is very noticeable at European conservatoires. For example, entire piano training classes at the Bremen University of Music have for years consisted largely of East Asian students.

Examples of classical singers

Renaissance: Isabelle Emerson's book Five Centuries of Women Singers begins with the famous vocal ensemble at the court of Duke Alfonso II of Ferrara . " Il Canto delle Dame di Ferrara " became known in Italian court circles and as far as Munich and Vienna (also known as " Concerto delle Donne "). Alfonso II. D'Este reserved this women's ensemble for his courtly concerts . The 12 madrigals by Luzzasco Luzzaschis for one to three sopranos and figured bass were created for these singers. The score from 1601 contains the true -to-note execution of the artistic decorations ( diminutions = resolution of long notes into many fast ones). This enables a precise idea of the female art of singing with its highly virtuoso technical finesse at the end of the 16th century, even before opera and the castrati became established. The names of the performing "Donne" have been passed down, they are Laura Peperara , Livia d'Arco , Anna Guarini (daughter of the poet and court secretary Giovanni Battista Guarini , to whom most of the madrigal texts go back) and Tarquinia Molza .

Opera singers: Anna Renzi (around 1620–1660), Barbara Strozzi's Venetian contemporary, is often referred to as the “first prima donna” or first “diva” of the opera stage . She was admired for her art of underlining the human affects of her singing through facial expressions, facial expressions and gestures of her body. Francesca Cuzzoni , Faustina Bordonis ' London competitor , also sang male hero roles written for castrati.

Marianne Pirker (1717–1782), "Tedesca" (German), is one of the rarer examples of a German prima donna among the popular Italian opera singers at European opera houses of the 18th century. With her husband, the violinist and librettist (translator) Joseph Pirker, she was employed at the Stuttgart Court Opera, where, as a serf , she met a hard fate. As a friend of the Stuttgart Duchess Elisabeth Friederike Sophie von Brandenburg-Bayreuth , she was accused of betraying his marital infidelity by her husband, Duke Carl Eugen , and punished by him with 10 years of solitary confinement.

Anna Franziska Benda (1728–1781), Gotha court singer, was the youngest sister of the Bohemian violin virtuoso Franz Benda , who taught her singing. She became famous in her time because of singing peculiarities such as passages of sighs, particularly long sustained notes and a special trill technique. Her art was reminiscent of the melodies of her brother, the Prussian concertmaster on the violin.

The German soprano Henriette Sontag (1806-1854) and the French mezzo-soprano Maria Malibran (1808-1836) became famous in the 19th century . Jenny Lind from Sweden (1820–1887) went down in music history as "The Swedish Nightingale". She was the first singer to travel worldwide and in her time the most traveled singer and shaped a new singer profile.

20th century In the 20th century, there are numerous outstanding singers, preferably in the world of opera: In the mid-1950s, the first black soprano appeared at the Metropolitan Opera, the contralto Marian Anderson (1897–1993). In 1939 she faced discrimination because of her skin color. In Europe, these include the sopranos Erna Berger (1900–1990), the coloratura sopranos Rita Streich (1920–1987) and Erika Köth (1925–1989). The world career of the Greek diva Maria Callas (1923–1977) was relatively short . Famous stage singers of the 20th and 21st centuries are Montserrat Caballé (* 1933), Gwyneth Jones (* 1936), the black singers Leontyne Price (* 1927) and who were celebrated for her unforgettable Bayreuth role as "black Venus" in Richard Wagner's Tannhäuser Grace Bumbry (born 1937); then the Slovak Edita Gruberová ("Queen of the Night") (* 1946), the Danish soprano Inga Nielsen (* 1946) and the Hamburg mezzo / contralto Hanna Schwarz (* 1943). Anna Netrebko (* 1971) is currently (2014) the most popular singer in the media worldwide .

Sound artists in Europe

- In the 1960s, Lilli Friedemann (1906–1991) created a new way of dealing with sound and hearing exclusively in groups, known as “ musical group improvisation ”. Originally a classical violinist , she gave up playing concerts instead. The composer Felicitas Kukuck took part in the group she founded .

As a freelance artist and university lecturer, Friedemann taught at music colleges , independent music institutes and in private courses. The usual instruments, the Orff instruments, and any material that could be used for this purpose were used when improvising. The "Ring for Group Improvisation" she founded still exists today in Hamburg. Her improvisations opened up new areas of sound such as the so-called " New Music " contains. An educational side effect was to contribute to the understanding of the new music. The Exploratorium Berlin is a musical institute inspired by her.

- Limpe Fuchs (* 1941) is an internationally known German sound artist and instrument maker on an unconventional path and a European example of this direction: "The malleability of sound".

- The modern classical music scene, actually better "serious music scene", shows - using Germany as an example - an abundance of independent ensembles for new music, whose members and founders are increasingly women, as the publication free ensembles for new music in Germany (2007) shows.

In addition to the ensembles for exclusively modern music, there are those whose boundaries between popular and serious music, old and new music, old and new genres and improvised music cannot be drawn:

- Anna Katharina Kränzlein , violinist and arranger, organizes concerts and events with various musicians and ensembles, in which she appears as a classical violinist with modern drum accompaniment, to end with improvisation. This includes singing, playing the piano and the hurdy-gurdy. After a classical music education (youth music competitions, flute, orchestral playing, music college) she was one of the founders of the southern German medieval folk rock band Schandmaul .

- Tarja Turunen from Finland (ex- Nightwish ) has a classical singing education.

- Olivia Trummer comes from a family of musicians and lives as a pianist, composer and singer. She is a multiple awardee, scholarship holder and gives concerts with her trio. She has released several CDs.

Personalities

- Birgit Lodes , Professor of Musicology at the University of Erlangen, then Munich, now Vienna.

- Isabel Mundry Professor of Composition at the Frankfurt University of Music, then Zurich.

Women composers in music history

Work term

Early music history

"String and flute playing, singing and the measured dance step" were associated with the mythological demigoddesses, the muses , in antiquity . According to scientific knowledge, the mythological belief in the Muses was mixed with actual experiences in ancient times. The muses appear in the oldest Greek scriptures ( Homer , 7th century BC; Plato , 4th century BC).

"The most important stringed instrument in the field of Greek culture", the kithara (early form Phorminx) is played by a woman on the oldest pictorial representation to date, a Cretan clay coffin from the second millennium BC. In the chapter on musically creative women from antiquity to the Middle Ages in the book mentioned above, Weissweiler describes this epoch. The term composer is not entirely appropriate for early music history because it is tied to a musical notation, of which hardly any examples have survived from ancient times. A new musical notation did not develop until the Middle Ages.

The Greek rhetor and grammarian Athenaeus only reported about the Greek poet-musician Sappho on Lesbos from the seventh century BC in the 3rd / 4th centuries. Century AD, she is said to have invented the " Mixolydian tune ", an octave genre of the Greek tone system .

The hetaerae of Greco-Roman antiquity were professional aulos players , dancers and singers. The aulos with its two chimes was played in two voices, the aulos players Lamia of Athens and Aphrodite Belestiche became particularly famous .