Incipit

In literature, history and musicology, the first words of a literary or academic text, a document or the beginning of a musical text are referred to as incipit ( Latin: “it begins”, from incipere “ to begin”, “to begin”) . Instead of a title, the incipit is used to identify ancient, medieval and early modern texts that have been handed down without a title or with different, often inauthentic titles. The incipit is usually used in modern specialist literature with the abbreviation inc. initiated.

While only the term Incipit is used in the English-speaking world , the Latin term Initium ("beginning") is mostly used in German-language scientific literature .

The corresponding term Explicit ("It ends ...") is used for the end of the text . In the Middle Ages, the information on the content and author was often given at the end of a text, which was usual at the beginning of the text.

Use in texts

For the designation of anonymously transmitted works or those with uncertain authorship that do not have a clearly fixed, authentic title (for example, countless short poems) or for which different titles are used, the opening words of the text are a convenient, relatively safe and unambiguous means of Identification. Such an incipit, consisting of the first two to twelve words of the text, enables the text to be quickly identified and cataloged with the help of incipit directories.

antiquity

The practice of naming a text after the words that opened it was already widespread in ancient times. Some examples:

- Sumerian cuneiform tablets from the 3rd millennium BC BC were cataloged by the archivists of the time using this method .

- Scholars of the Alexandrian School (approx. 300 BC to 600 AD) used incipits.

- The Roman poet Ovid referred to the didactic poem of Lucretius by not giving the title De rerum natura , but only the Incipit Aeneadum genetrix , which he therefore assumed to be known to his readers.

- The philosopher Porphyrios (3rd century) referred to the writings of his teacher Plotinus with their then common titles and commented: "By the way, I also want to put the beginning of the book so that every intended script is clearly recognizable after the beginning."

- The church father Augustine (354-430) indicated in his retractationes the incipits of his own works to facilitate identification.

In the Middle Ages, famous ancient poems were sometimes referred to not by their titles, but by their incipits, which were well known among the educated.

Middle Ages and Early Modern Times

As a formulaic phrase, incipit often appears at the beginning of texts from the Middle Ages and the early modern period. The meaning is "Here begins ..."; This is followed by a brief, sometimes detailed description of the content, which has the function of a work title, but without the exact, binding definition of the wording that is typical for titles in today's sense. Often the author's name is given, sometimes additional information about the work is added. An example is: Incipit liber scintillarum, id est diversarum sententiarum, distinctus per LXXXI capitula , German: "This is where the book of sparks begins, that is, various sentences , divided into 81 chapters" ("sparks" means flashes of inspiration).

In medieval manuscripts the first letter "I" of "Incipit" is sometimes executed as a splendid and imaginatively decorated initial . Often the entire sentence beginning with incipit is highlighted by a different font or color.

The author of the sentence introduced by Incipit was often not the author of the work, but the owner of a particular copy or a librarian. In these cases the incipit sentence is not a real part of the text, but rather plays the role of a randomly chosen, inauthentic heading.

From the late Middle Ages , the number of works that were written in vernacular languages (spoken languages as opposed to Latin as the language of scholars) increased sharply . In vernacular works there are introductory phrases that correspond to the Latin "Incipit ...", for example "Hie lifts itself ..." or "Heere bigynneth ..." etc.

This text beginnings had functions in modern printing primarily on the title page , some of them from the table of contents and chapter - headings are perceived. Individual chapters or books within a work were also introduced in this way, e.g. B. Incipit septimus liber compendii philosophiae "Here begins the seventh book of the handbook of philosophy". The introductory information should identify the work and serve as an initial orientation for the reader about the content. Such information was particularly helpful for orientation in collective manuscripts , where works by different authors were bound together in a single code .

Such stereotypical text beginnings became increasingly uncommon in the early modern period. From a literary point of view, the Renaissance began to attach importance to an appealing, original design of the opening words of a work. Since works now usually had clearly fixed titles, the incipit lost its role as an identification aid.

Judaism and Christianity

In Hebrew , the books of the Tanach are often named after their incipit; so the 1st book of Moses is called Bereschit , thus "In the beginning". It was only with the Greek translation of the Septuagint that the content-related term Genesis came up.

The Parashot , i.e. the weekly sections of the Torah reading on the Sabbath , are all named after the first words of the respective section ( Bereschit, Noach, Lech Lecha et cetera). At this practice which links the church year on: Here carry Sundays in many cases names on the first words of the liturgy belonging Introit go back (for example, Laetare , Quasimodogeniti , Misericordias Domini ). The lamentations of Jeremiah in the carmets are introduced with the Latin incipit Lamentatione Jeremiae Prophetae .

Council documents and papal encyclicals are named according to the Arenga after their initial words, such as Gaudium et spes , Lumen gentium , Mit Brennender Sorge or Amoris laetitia , also hymns and hymns such as Regina caeli or Zu Bethlehem .

Poems and lyrics

For some poems it is still common today to quote them after their opening words. In some cases the incipit is better known than the actual title. Thus Friedrich Schiller's poem Ode to Joy (1785) is usually stronger with the opening words "Joy, beautiful spark of the gods" as associated with his title. Short poems in particular sometimes have no title at all.

Folk songs are usually named after their opening words, e.g. B. "The moon has risen" instead of the title evening song .

Filenames

A modern variant of capturing texts based on their beginnings is that many word processing programs save a newly created document by default with the first few words of the text as the file name , if the user does not choose a specific file name when saving.

Incipitaria (lists of initials)

A reference work in which incipits (Initia) are compiled in alphabetical order is called Incipitarium or Initia Directory . In literary studies, incipitariums are used to quickly and clearly identify ancient, medieval and early modern works after the incipit. The works are arranged alphabetically according to their incipits and provided with a consecutive number; they can therefore be quoted according to their number in the directory. One example is Hans Walther: Initia carminum ac versuum medii aevi posterioris Latinorum. Alphabetical index of the beginnings of Middle Latin poetry. Göttingen 1959 (= Carmina medii aevi posterioris latina , I); another Lynn Thorndike , Pearl Kibre: A catalog of incipits of mediaeval scientific writings in Latin. 2nd edition Cambridge / Massachusetts 1963 (= The mediaeval academy of America. Publication 29). Medieval Latin poems from the period considered by Walther are quoted according to their Walther number.

In catalogs of medieval and early modern manuscripts, where many anonymous works are listed, the initial registers play a central role in finding individual texts. In works of modern research literature, an incipit register can often be found under the registers.

In indexes of poetry volumes and song collections, the poems or songs are not only listed according to title, but also according to incipits.

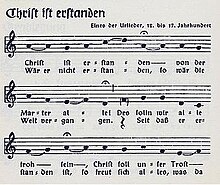

Thematic catalogs in music

In music, incipit catalogs are essential for the exact execution of a work catalog of a composer or for the differentiation of pieces of music. Another term for this is thematic catalog . About two bars of the beginning of the music pieces are reproduced, in a multi-movement work often a whole series of opening bars, or the beginning of the first characteristic theme .

The Leipzig scholar and book publisher Johann Gottlob Immanuel Breitkopf published Incipit catalogs on a larger scale in the 18th century, for the first time in 1762. For this purpose, his large music collection listed according to musical genres and alphabetically arranged composer names in order to offer them for sale. Some composers have cataloged their compositions themselves, such as Mozart , who kept a handwritten list of his works under their incipit. In the 19th century, the famous so-called Köchel directory was created , which with the abbreviation "KV" gave a number to every work by Mozart.

Thematic catalogs are an important part of historical musicology.

See also

literature

- Wolfgang Milde : Incipit and Initia . In: Lexicon of the entire book industry . 2nd edition, Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-7772-8527-7 , pp. 576 and 610f.

- Richard Sharpe: Titulus. Identifying Medieval Latin Texts. An evidence-based approach . Brepols, Turnhout 2003, ISBN 2-503-51258-5 , pp. 45-59

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ Ovid, Tristia 2, 261.

- ↑ Porphyrios, Vita Plotini 4.

- ^ Catalogo delle Sinfonie, che si trovano in Manuscritto nella Officina Musica di Giovanni Gottlieb Immanuel Breitkopf, in Lipsia. Party Ima. 1762. [1]

- ^ Page 1 of the Breitkopf catalog from 1762. Beginning of the incipits of the genre symphony. [2]

- ^ EH Müller von Asow (ed.): WA Mozart. Directory of all my works . Publishing house Doblinger (B.Herzmansky), Vienna-Leipzig. Vienna 1943.