Plotinus

Plotinus ( ancient Greek Πλωτῖνος Plōtínos , Latinized Plotinus ; * 205 , † 270 on an estate in Campania ) was an ancient philosopher . He was the founder and best known representative of Neoplatonism . He received his training in Alexandria from Ammonios Sakkas , from whom he received significant impulses. From 244 he lived in Rome , where he founded a school of philosophy , which he directed until he was fatally ill. He taught and wrote in the Greek language; his writings were intended for the student group and were only made known to a wider public after his death. In circles of the political ruling class of the Roman Empire he achieved a high reputation.

Plotinus did not see himself as the discoverer and proclaimer of a new truth, but as a faithful interpreter of Plato's teaching , which, according to him, contained in principle all the essential knowledge. From his point of view, it only required a correct interpretation of some controversial details and the explanation and justification of certain consequences of their statements. As a representative of an idealistic monism , Plotinus reduced all phenomena and processes to a single immaterial basic principle. The aim of his philosophical endeavors consisted in the approach to the " one ", the basic principle of the whole of reality, up to the experience of union with the one. As a prerequisite for this he saw a consequent philosophical lifestyle, which he considered more important than discursive philosophizing.

Life

Plotin's writings contain no biographically useful information. The biography of the philosopher, written by his pupil Porphyrios around three decades after Plotin's death, is the only contemporary source; the later tradition is based on it. This biography contains numerous anecdotes. It is considered credible in research, especially for the period between 263 and 268, which Porphyrios reports as an eyewitness.

Youth and student days

The year of birth 205 was calculated based on the information provided by Porphyry. Plotinus kept his birthday a secret, as he did not want a birthday party; he also never commented on his origin, as he did not consider such information to be worth communicating. The late antique Neo-Platonist Proclus assumed Egyptian descent; this has also been suspected in modern research. Eunapios names Lyko as the place of birth , which probably means Lykonpolis, today's Asyut . However, the credibility of this statement is very doubtful. From childhood, Porphyrios only reports that Plotinus told him that his nurse suckled him until he was eight years old, although he was already going to school.

Plotinus did not begin his philosophical training until 232 in Alexandria. Since none of the famous teachers there appealed to him, a friend took him to see the Platonist Ammonios Sakkas. He liked Ammonios' first lecture so much that he immediately joined him. For eleven years, until the end of his training, Plotinus stayed with Ammonius, whose teaching shaped his philosophical convictions. Then he left Alexandria to join the army of Emperor Gordian III. to join, who set out from Antioch in 243 on a campaign against the Persian Sasanid Empire. His intention was to familiarize himself with Persian and Indian philosophy in the Orient. But after the Romans suffered a defeat in the battle of Mesiche and the emperor was killed in early 244, Plotinus had to flee to Antioch. From there he soon went to Rome, where he settled permanently.

Teaching in Rome

In Rome, Plotinus gave philosophical lessons to an initially small number of students. At first he kept to an agreement that he had made with two other disciples of Ammonius, Origen and Herennios. The three had undertaken not to publish anything they had heard in their late teacher's lectures. The question of the exact content and purpose of this confidentiality agreement has been discussed intensively in research. When only Herennios and later Origen broke the agreement, Plotinus no longer felt bound by it either. 253/254 he began his writing activity.

Plotinus emphasized interaction with his listeners during the class and encouraged interim questions. His courses were therefore not just lecturing, but rather had a discussion character. The problems raised in the process gave him and his students the opportunity to write individual writings. From his interpretation and further development of the teachings of Ammonius, a philosophical system of special character emerged, Neoplatonism. The critical examination of the doctrines of Middle Platonists and Peripatetics was an important part of the class.

Outstanding students of Plotinus were Amelios Gentilianos (from 246) and Porphyrios (from 263). Porphyrios had previously studied in Athens with the famous Platonist Longinos . There were differences in teaching between the Neo-Platonic schooling in Plotinus and the Middle Platonic schooling in Longinos, which resulted in controversial literature and a lively exchange of views. Longinos did not take Plotinus seriously; he did not regard him as a philosopher, but as a philologist . Neoplatonism found approval in the circles of distinguished Romans. Plotin's listeners included a number of senators, including Rogatianus, Marcellus Or (r) ontius and Sabinillus (full consul of the year 266 together with the emperor), as well as the rich philosopher Castricius Firmus , a particularly committed Neoplatonist. Women were also enthusiastic about Neoplatonism and became avid followers of Plotinus.

Philosophical way of life and social action

The emperor Gallienus, who ruled as sole ruler from 260 and was open to cultural issues, and his wife Salonina valued and promoted Plotinus. Impressed by the imperial favor, Plotinus came up with the plan to repopulate an abandoned city in Campania . It was to be ruled according to the laws designed by Plato and was to be called Platonopolis. He himself wanted to move there with his students. Porphyry reports that thanks to Plotin's influence with the emperor, this project had a good chance of being realized, but failed because of court intrigues.

Plotinus was not only regarded as a philosophy teacher in the political ruling class. He was often chosen as arbitrator in disputes. Many noble Romans made him the guardian of their underage children before they died. His house was therefore full of adolescents of both sexes, whose property he carefully administered. In his educational work, he benefited from his extraordinary knowledge of human nature, which Porphyrios praised.

As is customary with the ancient philosophers, Plotinus did not understand philosophy as a non-binding preoccupation with conceptual constructs, but as an ideal way of life that could be consistently implemented in everyday life. For him, this included an ascetic diet, little sleep and incessant concentration on his own mind in all activities. The striving for knowledge was at the same time a religious striving for redemption. His religious life, however, did not take place in the context of communal activities according to the traditional customs of a cult, but formed a strictly private sphere. He did not take part in the traditional religious festivals, rites and sacrifices. His programmatic saying that he does not take part in the service is well known, because "those (the gods) have to come to me, not me to them". His attention turned to the "formless" deity with whom he sought to unite. Porphyry writes that Plotinus had this union four times in the five years they spent together. Such an experience is referred to with the Greek term “Henosis” (union, becoming one).

Last years of life

In 268, on Plotin's advice, Porphyrios moved to Sicily to cure his melancholy there. In the same year, Emperor Gallienus was murdered. Soon afterwards, Amelios also dropped out of school and left for Syria . Plotinus, who was seriously ill, had to stop teaching. Since his illness - probably leprosy or tuberculosis - was associated with nauseating symptoms, most of the students avoided dealing with him. In 269 he moved to Campania on the estate of his late student Zethos, from where he never returned. The doctor Eustochios from Alexandria, who belonged to the group of students, took over the medical care of the seriously ill. Castricius Firmus had the philosopher supplied with food from his estate near Minturnae .

When Plotinus died in 270, Porphyrios was still in Sicily, but was later informed of the events by Eustochios. His description of the death of the philosopher is famous. He transmits the last words of the dying man who called it his goal to “raise the divine in us to the divine in all”. Then a snake crawled under his bed and slipped into a hole in the wall. Porphyrios is alluding to the soul serpent. The soul that escapes at death was imagined in the form of a bird or a snake.

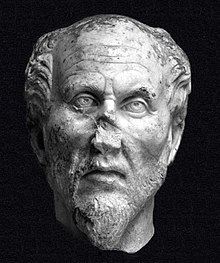

iconography

As Porphyrios reports, Plotinus refused to have himself portrayed by a painter or sculptor, because his body, as a material object, is only a transitory image of a spiritual reality and as such is not worth seeing; To make a copy of this image is absurd. With this, Plotinus placed himself in the tradition of Platonic criticism of the visual arts. Amelios, however, caused the painter Carterius to paint a picture of Plotinus from memory, which, according to Porphyrios' judgment, turned out to be lifelike.

Various attempts have been made to identify Plotinus with philosophers who are represented in surviving works of ancient sculpture without names. These include five marble heads, three of which were found in Ostia Antica . Four of them are copies of the same type, the fifth shows a different person. According to the current state of research, however, they date from the Severan era and are therefore not chronologically relevant. Due to the presumption that they were plotinus, they were often depicted as plotin busts in the 20th century. Hence the misconception that Plotin's appearance was known.

On a sarcophagus in the Museo Gregoriano Profano, part of the Vatican Museums , a philosopher can be seen in a group who may be Plotinus, but this assumption is speculative.

plant

Plotinus did not start writing until 253/254 and lasted until shortly before his death. Originally his writings were informal records of thought processes intended only for the group of students; they weren't even given titles by the author. After Porphyrios entered the school in 263, Plotinus intensified his literary activity at the request of Porphyrios and Amelios . According to Porphyrios' overview, 24 papers from the period from 263 to 268 were added to the 21 papers written before 263; after Porphyrios' departure (268) nine more were made. However, these numbers are based on Porphyrios' partly arbitrarily changed division of Plotin's legacy into individual writings, the subsequent titles of which, originating from the student group, became natural.

As an author, Plotinus concentrated on the content of his explanations and did not endeavor to elaborate a literary-stylistic elaboration. He used stylistic devices, but only to illuminate the philosophical trains of thought, not for the sake of the convenience of expression. He didn't care about the spelling. Although his teaching formed a coherent system of thought, he never tried to give a systematic overall presentation, but only discussed individual topics and problems. When he had clarified a question for himself, he wrote his thoughts down fluently in one go; he never read through what was written in order to correct or revise it. He found reading difficult because of his poor eyesight. Therefore he entrusted Porphyrios with the task of collecting, organizing and publishing his writings. Only around three decades after Plotin's death, when he himself was already nearing the end of his life, did Porphyry fulfill this mandate.

As the editor, Porphyrios decided against a chronological order; he preferred a grouping based on content. For this purpose, he divided Plotin's estate into 54 individual fonts and formed six groups of nine fonts each. According to this order, the collected works of Plotinus are known under the name Enneades - "Neunheiten", "Neuner (gruppen)". Thanks to Porphyry's conscientious editing, the complete works of Plotinus have been preserved and even a chronological grouping has been passed down. In his biography of Plotinus, which he placed before the collection, Porphyrios lists the writings and assigns them to the author's creative periods. Since the titles of the individual writings do not come from Plotinus, they are usually not mentioned when quoting.

Teaching

Plotinus did not see himself as an innovator and inventor of a novel system. Rather, he made it a point to be a faithful follower of Plato's teaching. In his connection to Plato, he relied primarily on his dialogue Parmenides . He was convinced that his philosophy was derived consistently from Plato's statements, that it was an authentic interpretation and uninterrupted continuation of the original Platonism, and that he explicitly formulated what Plato expressed in an "undeveloped" way. The justification of this point of view has long been controversial among philosophical historians. It was not until the late 18th century that Neoplatonism was designated as such and separated from the older tradition of the interpretation of Plato.

To justify his preference for Platonism, Plotinus stated that Plato had expressed himself clearly and extensively and that his explanations were masterful, while the pre-Socratics were content with dark hints. He also asserted that Plato was the only one who recognized the absolute transcendence of the highest principle. He dealt with the ideas of other philosophical schools - the stoics and the peripatetics . From this he adopted approaches that seemed to him compatible with Platonism, he rejected other ideas. He vehemently opposed unplatonic ideas from oriental religious movements ( Gnosis , Zoroastrianism , Christianity ) by either formulating a written reply or commissioning a student to refute it. In contrast to other Platonists, he never referred to oriental wisdom, but exclusively to Greek tradition.

Ontology and Cosmology

Fundamental to Plotinus is the division of the entire variety of things into a superordinate, purely spiritual ( intelligible ) world ( kósmos noētós ) and a subordinate, sensually perceptible world ( kósmos aisthētós ). The subordination of these two areas is the most striking expression of the hierarchically graded ontological order of reality as a whole. In the detailed elaboration of this system of order, Plotinus assumes relevant indications from Plato. The part of total reality that is inaccessible to the senses is divided according to his teaching into three areas: the one , the absolute, supra-individual spirit ( nous or nus ) including the platonic ideas and the soul ( world soul and other souls ). The sensually perceptible world is the result of an influence from the spiritual world on the formless primordial matter, in which the shapes of the various sensory objects appear.

The one

According to Plotin's conviction, the starting point for the existence of the distinguishable, which is assigned to the principle of plurality or multiplicity, must necessarily be something simple and undifferentiated. Knowledge progresses from the more complex to the simpler. Everything compound and diverse can be traced back to something simpler. The simpler is superior to the more complex in the sense that it is the cause of its existence. Therefore the simpler is the higher, because the more complex is in no way required, while conversely the more complex cannot exist without the simpler. Compared to the simple, the complex is always inadequate. Ultimately, a mental advance from the more complex to the simpler must lead to the simplest. The simplest can no longer be traced back to anything else; here you have to “stop”, otherwise an infinite regress (advancement into the infinite) would occur. With the simplest, the highest possible area of total reality is reached. Plotinus calls this utterly simple "the one" (Greek τὸ ἓν to hen ). As the extreme opposite of the differentiated and manifold, it cannot contain any distinction, neither a duality nor any other plurality. In this context, Plotinus recalls that the Pythagoreans , referring to the name of the god Apollo, also called the one “not many”. They wanted to justify the idea of divine unity with an (albeit wrong) etymology of the name of God, by deriving “Apollon” from a , “not”, and polloí , “many”. Since Plotinus, without exception, reduces everything that exists spiritually or physically to the One, his philosophy is monistic .

As the origin and reason of existence of all things, the One is the highest that there can be. In a religious terminology, he would in fact play the role of the supreme deity. Such a determination would, however, already be an inappropriate differentiation, because every determination implies a difference and thus a non-unity. For this reason it is also inadmissible to ascribe to the One characteristics that are considered divine, for example to identify it with good or being. Rather, the One is neither being nor non-being, but rather omnipotent, and neither good nor bad, but beyond such conceptuality. From the point of view of the thinker, it appears as something higher, something worth striving for and therefore good, but for itself it is not good. One cannot even truthfully state that the one “is”, because being as the opposite of non-being or perfect being in contrast to a diminished being already presupposes a distinction and thus something that is subordinate to the one. Strictly speaking, the definition of the one as "one", as simple or uniform in the sense of an opposition to plurality, is a misunderstanding of its true, non-opposed nature, about which, paradoxically, no accurate statement is possible. One is “unspeakable” ( árrhēton ). If Plotinus nevertheless makes statements about the one thing, he tends to provide such statements with restrictions such as “as it were”, “to a certain extent” ( hoíon ). He makes it clear that these terms are not meant here in their usual meaning, but are only intended to indicate something that he can only inadequately express.

The one thus remains in principle withdrawn from an intellectual, discursive understanding. Nevertheless, according to Plotinus, reason compels us to accept the one. He also thinks that there is an overly reasonable approach to the one, because it can be experienced. This becomes possible if you turn inward and leave behind not only the sensual but also everything spiritual. According to Porphyrios' statements, Plotinus claimed such an approach to the one and union with it as a repeated experience for himself. Plotinus is often referred to as a mystic because of his claim that there is a transcendent experience of a supreme reality . It should be noted, however, that this term (in today's sense) did not exist then and that no such self-designation has been handed down to Plotinus.

The nous and the ideas

In the ontological hierarchy, the one is immediately followed by the nous (spirit, intellect), an absolute, transcendent, supra-individual instance. The nous emerges from the one in the sense of a timeless causality. What is meant here is not a production as a creation in the sense of a willful doing of the one, but a natural necessity. The nous as a certain something emanates from the undifferentiated one ( emanation ), but without the source itself being affected and thereby changing in any way. At the same time, since one and nous are two things, the principle of duality and difference arises. Activity words such as emergence, overflowing or arising, which point to a becoming, are not to be taken literally in this context, but only metaphorically . The "emergence" ( próhodos ) is not to be understood as a temporal process in the sense of a beginning of existence at a certain point in time or in a certain period of time. Plotinus only means that what comes out owes its existence to that from which it arises and is therefore subordinate to it. Plotinus illustrates emanation with the image of the sun or a source. Rays of light emanate incessantly from the sun without it itself suffering a loss or any other change (according to the idea of the time).

In contrast to the one, the nous is one of those things to which certain characteristics can be assigned; in particular it can be described as being. It forms the uppermost area of "beingness" or substance ( Ousia ). In Neoplatonism, being is not simply present or not present in relation to a thing, but it is graduated: There is a being in the full sense and a restricted or diminished, more or less “improper” or shadowy being. Only the nous as the uppermost part of the realm of being is unrestricted in the full and proper sense. Hence, for Plotinus, the sphere of spirit and thought is identical with that of real being; their essential characteristics being and thinking coincide. “The same thing is thinking and being” is a principle of the pre-Socratic Parmenides quoted by Plotinus .

Plotinus combines the principle that being (in the true sense) is thinking with Plato's theory of ideas . When the human intellect does not turn to the sensually perceptible individual things in their particularity, but to the Platonic ideas on which they are based, then it enters the world of thought, the realm of the nous. There he encounters the beautiful and the good , insofar as it does not show itself in always defective individual objects, but exists in and for itself in its perfection. When the contents of thought are grasped in and for themselves as platonic ideas in their existence, they are thought. Such thinking is not a discursive deduction, but a direct spiritual grasping of what is thought. The thought is nowhere to be found other than in the world of thought. The objects of thought are the contents of the nous, which consists of nothing other than the totality of Platonic ideas.

This is how Plotinus arrives at his famous tenet, characteristic of his philosophy: Ideas exist only within the nous. Some Middle Platonists had understood the ideas as something produced by the nous and thus subordinate to it and therefore located below the nous. Plotinus contradicts this with the argument that in this case the nous would be empty. But emptiness would contradict its essence as a self-thinking mind. If it had no content of its own, it would not be able to think for itself. Rather, in order to be able to think at all, he would have to turn to something that is subordinate to him, the objects of thought that he himself has produced. Then he would be dependent on his own products for his essence, which is thought. He would then be at the mercy of uncertainty and deception, since he would not have direct access to the ideas themselves, but only to images of them that he would have to generate in himself. Plotinus considers this to be absurd. Like Aristotle , he is convinced that the nous thinks itself and that its thinking is exclusively related to itself. In contrast to Aristotle, however, he combines this conviction with the doctrine of the objective reality of Platonic ideas.

When Plotinus speaks of nous, the term “thinking” used in this context does not mean a purely subjective mental activity. There is no analogy between the thinking of the nous and the idea of a human individual generating thoughts in the subjective act of thinking. Rather, the nous is an objective reality, a world of thought that exists independently of the individual thinking beings and to which the individual thinking individuals have access. The individual turned towards this objective reality does not produce his own thoughts, but grasps its contents through his participation in the realm of the spirit. His individual thinking consists in this grasping.

Insofar as it is nothing but pure spirit, the nous is essentially unitary. Since it encompasses a multitude of ideas, it is also a multiplicity. Because the actual being is assigned only to the ideas, the nous is at the same time the totality of things that really exist. Outside of it there is only improper, more or less diminished being. Plotinus considers the number of objects of thought, which are the contents of the nous, to be finite, since from his point of view an infinite number as the greatest possible separation, isolation and distance from the unity would be an impoverishment of the individual objects, which is incompatible with the perfection of the nous . He does not regard the self-confidence of the nous as reflexive, as it cannot address itself. If the mind were to think that it is thinking, then this state of affairs would in turn be the object of the thinking, which leads to an infinite regress. Rather, Plotinus assumes a composite unity and identity of the thinking, the thought and the act of thinking. Structuring is only necessary from the perspective of a discursive viewer.

While the one is not good for itself, but only appears to be good from the perspective of someone below it, the nous is good in and of itself, because it exhibits the highest degree of perfection that can be inherent in a being.

Whether Plotinus accepted ideas from the individual and thus granted the individual as such a presence in the nous is disputed in research. Mostly it is believed that he did this.

The realm of the soul

The next lower hypostasis (level of reality) follows the nous , the realm of the soul. This area is also not perceptible to the senses. The soul forms the lowest area of the purely spiritual world; immediately below it begins the sphere of sense objects. Like the nous from the one, the soul emerges from the nous through emanation; it is an outward development of the mind. Here, too, the emergence is only to be understood as a metaphor for an ontological relationship of dependence; it is not a question of an origin in time. Like everything spiritual, the soul exists in eternity; it is uncreated and immortal. It relates to the nous as matter relates to form.

Following the Platonic tradition, Plotinus argues for the incorporeal nature of the soul, which is contested by the Stoics. He also opposes the view that the soul is a mere harmony, as some Pythagoreans believed, or just the entelechy of the body, as Aristotle said. For him, the soul is rather an immutable substance that moves on its own and does not need a body. This also applies to the souls of animals and plants.

The soul is the organizational principle and the invigorating authority of the world. Plotinus regards the soul as a unit, under this aspect he calls it the "total soul " ( hē hólē psychḗ ). The total soul appears on the one hand as the world soul , on the other hand as the multitude of souls of the stars and the various earthly living beings. The world soul enlivens the whole cosmos, the individual soul a certain body with which it has connected. There is only one single, uniform soul substance. Therefore, the individual souls do not differ by special characteristics, but each individual soul is identical with the world soul and with every other individual soul with regard to its essence. When Plotinus speaks of "the soul", any soul can be meant.

However, the world soul differs from a human soul in that the body of the world soul is the eternal cosmos and the body of the human soul is a transient human body. The individual souls are all closely connected with each other and with the world soul, since they naturally form a unity. Their essential identity with the world soul does not mean, however, that they are part of it; the individuality of the souls is always preserved. Despite the identity of the individual souls, there are differences in rank between them, since they realize their common spiritual nature to different degrees. In addition to the changing conditions of existence of the individual souls, which influence their development possibilities differently, there are also natural, not time-related rank differences.

As the creation of the nous, the soul has a share in it, which is expressed in the fact that it is capable of thinking and perceiving ideas. It “becomes”, as it were, what it is looking for. She unites with it through "appropriation" ( oikeíōsis ). When she turns to the nous and dwells in its realm, she is nous herself. She achieves the one by becoming one with him. But she does not always turn to something higher. It stands on the border between the spiritual and the sensible world and so within the framework of the world order it also has tasks that relate to the sphere of material, sensually perceptible things below it. As a world soul she is the creator and ruler of the physical cosmos. As an individual soul it is endowed with the same creative abilities as the world soul, and through its unity with the world soul it is co-creator; Seen in this way, every single soul creates the cosmos.

There is an important difference between the world soul and the souls on earth with regard to their functions in that the world soul always remains in the spiritual world and from there effortlessly animates and guides the universe, while the souls on earth have descended into the physical world. The world soul is in a state of undisturbed bliss because it does not leave its home. It is based exclusively on the nous. On the other hand, souls on earth are exposed to dangers and are subject to many impairments, depending on their living conditions there and the nature of their respective bodies.

Matter and body world

The material world of sense objects is created and animated by “the soul” - the world soul and the other souls as co-creators. The soul relies on its connection with the nous that is involved. Since Plotinus, like many Platonists, does not take the account of creation in Plato's dialogue Timaeus literally, but in a figurative sense, he does not assume any creation in time for the physical world or for the spiritual world. The earth as the center of the world and the stars exist forever, just like the soul, to whose natural determination it belongs to produce the physical forever. Since the soul has access to the world of ideas of the nous on the one hand and to the material sphere on the other hand, it is the mediator who gives the material a share in the spiritual. She brings the ideas into the formless primordial matter and thus creates the bodies, whose existence is based on the fact that matter is given form. The visible forms into which the soul shapes matter are images of ideas. For example, physical beauty comes about when the soul shapes a piece of matter in such a way that it shares in the spiritually beautiful.

The process of creation takes place in such a way that the soul first strings together the Platonic ideas discursively without depicting them. It accomplishes this on the highest level of its creative activity in the physical world. On the next lower level, their imagination ( phantasía ) is active, which turns the ideas into immaterial images that the soul looks at inwardly. Only on the lowest level do the images become external objects, which the soul now grasps by means of sensual perception ( aísthēsis ).

Plotin's conception of matter ( hýlē ) is based on the relevant conception and terminology of Aristotle. As with Aristotle, matter in itself is formless and therefore imperceptible as such, but everything that can be sensed arises from the fact that it always takes up forms. Everything physical is based on a connection between form and matter. Plotinus builds this Aristotelian concept into his Platonism. In and of itself, matter is “nothing”, in Aristotelian terms pure potency , something not realized, only existing as a possibility. Seen in this way, matter as “nonexistent” is that which differs most strongly from the spiritual world, the realm of things that actually exist. It is thus the ontologically lowest and most imperfect. Nothing can be further from the one than they. Like the One, it is indeterminate, but for the opposite reason. The one cannot have determinations, but only donate, matter cannot possess them either in and for itself, but can certainly absorb them. The matter on which earthly things are based can only temporarily retain what has been received, it does not mix with it and sooner or later it has to slip away from it. Therefore the individual earthly phenomena are transitory, while matter as such is unchangeable. Because of its indeterminacy, only negative things can be said about matter - what it is not. It only exhibits properties because it is given forms from outside. Because it is not itself made in a certain way, it can take any shape - otherwise its own nature would be an obstacle. One of the negative statements is that matter has no limit and that it is absolutely powerless and therefore plays a purely passive role.

Since the nous is determined as good and being and nothing can be further removed from being than matter, from a Platonic point of view the conclusion that matter is something absolutely bad or evil is obvious. The Middle Platonist Numenios , whose teaching Plotinus studied intensively, actually drew this conclusion . It leads to dualism with the assumption of an independent evil principle . Plotinus also describes matter as bad and ugly; nothing can be worse than them. It should be noted, however, that the bad in Plotin's monistic philosophy does not have an independent existence, since badness only exists in the absence of the good. Thus, matter is not bad in the sense that "badness" or "malignancy" can be assigned to it as a real property, but only in the sense that it is furthest away from good in the ontological hierarchy. In addition, the formless primordial matter as such does not really exist, but is only a conceptual construct in Plotinus and Aristotle. In reality the physical cosmos is always and everywhere subject to the guidance of the soul and thus to the formative influence of the formative ideas. Real matter exists only in connection with forms. Hence, in practice, the imperfection of material objects is never absolute, for it is through their forms that they receive the influence of the spiritual world. In general, the principle applies that the recipient determines the extent to which the recipient is absorbed. The lower can only receive the higher insofar as its limited receptivity allows it.

Since there is a unity between the world soul and all other souls and the whole universe is permeated by a unified soul principle, there is a sympathy ( sympátheia ) between all parts of the universe. Plotinus takes this teaching from the Stoa. However, despite this connectedness of things, he sees a fundamental difference between the intelligible and the sensually perceptible world in the fact that in the spiritual world each of its individual elements simultaneously contains the whole, while in the physical world the individual exists for itself.

In addition to physical, sensually perceptible matter, Plotinus also assumes a spiritual (intelligible) matter, with which he takes up Aristotle's considerations and reinterprets it in a Platonic way. He thinks that the purely spiritual things that are not connected to any physical matter also need a material substrate. Their multiplicity means that they are different from one another. That assumes a shape of its own for each of them. For Plotinus, however, form is only conceivable if, besides a formative authority, there is also something shaped. He therefore considers it necessary to assume an intelligible matter common to all forms. Like physical matter, intelligible matter does not occur unformed; In contrast to it, however, like everything spiritual, it is not subject to any changes. Another argument from Plotinus is that everything physical, including physical matter, must be modeled on something analogous in the spiritual world.

Time and eternity

In the field of the philosophy of time , Plotinus found not only individual suggestions in Plato's dialogue Timaeus , but a concept that he adopted and expanded. The Greek term for eternity, aiṓn , originally denotes life force, life and lifetime, in relation to the cosmos its unlimited duration, whereby the fullness of what a long or endless period of time can produce is implied. Plato ties in with this. But he re-shaped the term in a radical philosophical way, since from his point of view a chronological sequence does not result in abundance. Rather, everything that takes place in the course of time is characterized by deficiency: the past has been lost, the future has not yet been realized. Unrestricted abundance is therefore only possible beyond temporality. This gives rise to the concept of an eternity, which is not a long or unlimited duration, but a timeless totality of being. Perfection becomes possible through the abolition of the separation of the past, the present and the future. Eternity remains in the One, while the flow of time, which means a constant succession of earlier and later, divides reality. Expressed in the language of Platonism, eternity is the archetype, time the image .

Plotinus adopts this concept of eternity. It approaches it from the aspect of liveliness contained in the original meaning of the word. A common feature of time ( chrónos ) and eternity ( aiṓn ) is that both are to be understood as manifestations of life, whereby “life” means the self-development of a whole. The spiritual world is characterized by timeless eternity, the physical by the endless flow of time. Like all components of the physical cosmos, time is a product of the soul and thus of life, because the soul is the creating and animating factor in the physical world. The life of the soul expresses itself in the fact that its unity shows itself as cosmic multiplicity. Likewise, the eternity of that which is beyond temporal is to be understood as a kind of life. Here, too, Plotinus understands “life” to mean the self-development of a unified whole (the nous) in the multitude of its elements (the ideas). However, this does not mean a division of the unity, because the elements remain in the unity of the whole. Like eternity on the self-development of the nous, time is based on the self-development of the soul. In time the unity of the life of the soul separates into a multiplicity, the elements of which are separated from one another by the flow of time. The intermingling of the world of ideas thus becomes an orderly sequence of individual ideas for the soul - the soul is temporalized.

As a component of the spiritual world, every single soul actually belongs to the eternal unity of the spiritual, but its natural will to an independent existence is the cause of its isolation. Since this isolation, as a separation from the totality of being, is necessarily an impoverishment, the impulse to remove this lack of abundance exists in the soul. In terms of time, this means a return to unity.

The striving for return aims at a change that must take place in the consciousness of the soul. Consciousness distinguishes between what is known and what is known and records separate contents such as the current state and the target state, which it relates to one another. This is only possible as a discursive process and therefore requires time. For this reason, the individual soul needs and creates a time that it individually experiences, its specific past, present and future. Although the reality of life is thus split up in time, the soul does not lose its natural participation in the unity of the nous. Therefore it can generate memory, bring past, present and future into context and thus grasp time as a continuum; otherwise time would break up into an unconnected series of isolated moments. Since the soul strives for a certain goal, the time it creates is forward-looking and the sequence of events is always ordered accordingly. In contrast to human souls, divine souls (world souls, celestial souls) have no memory because they did not fall down into time.

ethics

Plotin's ethics is always related to the salvation of the philosopher who has to make a decision. In all considerations about what to do or not to do, the central question is what consequences a certain behavior has for the philosopher himself, whether it inhibits or promotes his philosophical endeavors. Everything else is subordinated to this point of view. As in all the ethical theories of the ancient Platonists, the acquisition and maintenance of virtues ( aretaí ) is a central concern. A big difference to Plato's thinking is that the philosopher is not considered in his capacity as a citizen and part of a social community. The service to the state, which is important for Socrates and Plato, the subordination of personal endeavors to the state's welfare, does not play a role in Plotin's teaching. His intention, as attested by Porphyrios, to found a settlement organized according to Plato's ideas of the ideal state, finds no echo in his writings. His formulation, often quoted in philosophical literature, is famous that the philosophical way of life is a "separation from everything else that is here, [...] the lonely escape to one".

For Plotinus, all action ultimately aims at viewing it as an ultimate cause . Man acts because he seeks to gain what he has created or procured as an object of display. If he is unable to see the ideas internally ( theōría ), he obtains objective objects in which the ideas are represented as a substitute. Since the need to look is the motive of all activity, the consideration and thus the inner world of the subject has priority over any practical reference to the outer world.

For Plotinus, the well-being of the person is identical to the well-being of the soul, for the soul alone is the person. Since the body is not part of the person, but only externally and temporarily connected with him, Plotinus calls on us to avoid the pursuit of physical pleasures. In general, he looks at earthly fates with aloof calm and compares the vicissitudes of life with the staging of a play. He does not consider any event to be so important that it provides a legitimate reason for giving up the philosopher's indifferent attitude. External goods are irrelevant for happiness ( eudaimonia ), since they cannot increase it; Rather, happiness is based exclusively on the “perfect life”, the optimally realized philosophical way of life.

The bad, and thus also the bad in the moral sense - the word to kakón was used for both in ancient Greek - has no being of its own, but is just the absence of good. The absence of good is never absolute; it is only a greater or lesser limitation of its effectiveness, for the action of good even reaches matter. Therefore, evil is not a power in its own right, but something that is nothing, needy and powerless. It is overcome by constantly paying attention to the good.

Plotinus attaches great importance to free will . He emphasizes that the activities of the soul are not by nature effects or links in external causal chains. Rather, the soul draws the criteria of its decisions from itself. Only through its connection with the body is it subject to external constraints and its actions are only partially affected by this. By its nature it is a self-determined being. Plotinus does not see free will in the ability to choose arbitrarily between different options, i.e. not to be subject to any determination. Rather, free will consists in the fact that one is able to do precisely that which the person who acts spontaneously strives, if he is not subject to any external pressure or error. The not arbitrary, but spontaneous action with which the soul consequently follows its own insight according to its spiritual nature is an expression of its autarky (self-sufficiency). It does not fit into an already existing causality, but rather sets the beginning of a series of causes. Following this conviction, Plotinus turns against deterministic and fatalistic doctrines that view human fate as the result of external influences. In particular, he fights against an astrological worldview that traces human character traits and fates back to the effects of the stars and thus limits the freedom of the soul. He admits that the stars have an influence, but considers it insignificant. He denies the possibility of a blind chance, since nothing in the world happens arbitrarily, but everything is well ordered.

Plotinus generally opposes suicide. He justifies this with the fact that the motive for such an act is usually connected with affects to which the philosopher should not submit. In addition, it cuts off existing development opportunities. Only in special cases, such as when there is a threat of mental confusion, does he consider voluntarily chosen death to be a way out to be considered.

The soul in the body world

Plotinus assumes that every soul, due to its immaterial nature, is at home in the spiritual world from which it comes. But she has the opportunity to descend into the physical world and connect there with a body, which she then directs and uses as a tool. In this role she can in turn choose whether she wants to focus her attention and her striving predominantly on the purely spiritual or orientate herself on body-related goals. On earth she finds material images of the ideas that remind her of her home country and are therefore tempting. In contrast to the timeless ideas, however, these images are ephemeral and therefore deceptive. In addition, as images they are always very imperfect in comparison with their archetypes.

Plotinus does not understand the connection of the soul with the body in the usual sense that the soul resides in the body and inhabits it, but rather, conversely, he means that it surrounds the body. When the body dies, the soul leaves it. The separation from the body does not mean a farewell to the physical world for the soul, because according to the Platonic theory of the migration of souls it is looking for a new body. In Plotin's opinion, this can also be an animal or even a plant body. So one rebirth follows another. In principle, however, the soul has the opportunity to interrupt this cycle and return from the physical world to its spiritual home.

The descent of the soul

The question of why a soul ever decides to leave its natural place in the spiritual world and to go into exile plays a central role in Plotin’s thought. The connection with a body subjects them to a multitude of restrictions and disadvantages that are contrary to nature for them, and therefore requires explanation. Plotinus tries hard to explain. The descent of souls from the spiritual world into the physical world and their possible return is the core theme of his philosophy. He asks about the causes and conditions of both processes.

The explanations and assessments of descent that he finds and discusses in his writings do not convey a consistent picture. Generally, he rates any turn to a lower state negatively. The higher is always what is worth striving for and everything naturally strives towards the good. It is unquestionably clear to Plotinus that the consistent turning away from the physical and towards the spiritual and the ascent to the home region should be the goal of the soul. He expressly expresses his view that it is better for the soul to loosen its ties to the physical world and leave earthly existence; thus she attains bliss. Life with the body is an evil for them, separation from it is a good thing, and descent is the beginning of their calamity. Porphyrios reports his impression that Plotinus was ashamed to have a body. Such statements seem to suggest that the descent of the soul is contrary to nature and a mistake that should be reversed. Plotinus does not draw this conclusion, however, because it contradicts his basic conviction that the existing world order is perfect and necessary by nature. In the context of a completely perfect world order, the stay of the soul in an environment that is actually foreign to it must also have a meaning. He tries to find this meaning.

He finds the solution in the assumption that what is an evil for the individual soul is meaningful and necessary under the overriding aspect of the cosmic overall order. The soul suffers a considerable loss of knowledge and cognitive abilities through its descent. In doing so, she forgets her origin and her own nature and faces many hardships. But the body world benefits from this, because through the presence of the soul it receives a share in life and in the spiritual world. Such participation can only be imparted to it by the soul, since the soul is the only authority that, as a member of the border area between the spiritual and the physical world, can establish the connection between the two parts of total reality. In a perfect overall order, the lowest realm of the whole must also be perfected as much as possible. This task falls to the souls who participate in the care for the universe. Therefore the souls cannot and should not finally free themselves from the physical way of existence. A return to the spiritual home can only be temporary, because the physical world always needs to be animated, not only by the world soul and the star souls, but also by the individual souls on earth. The descent of souls is a necessity within the framework of the entire world order, but they are not compelled to do so by an external power, but rather follow an inner urge. The factor that motivates them is their boldness or audacity ( tólma ). When souls descend, they do not fundamentally turn away from the good and toward the bad or worse. They continue to strive for the good, but now they seek it in areas where it can be less prominent.

In addition, Plotinus puts forward further arguments for his assumption that the descent of souls into the physical world is not a fault in the world order. The soul is by nature so disposed that it can live in the spiritual as well as in the material world. It must therefore be in accordance with their nature to act out this double disposition. When the soul experiences badness in earthly existence, it gains greater appreciation for the good. In addition, through the connection with a body, it can bring its own forces to an efficacy which is excluded in the spiritual world due to a lack of opportunity for development. In the spiritual world, these forces exist only potentially and remain hidden; they can only be realized by dealing with matter. The soul that has descended into the physical world wants to be for itself. It wants to be something other than the spirit and belong to itself; she enjoys her self-determination. She is enthusiastic about the different earthly and out of ignorance values it more than herself.

For Plotinus, the fact that the souls follow their urge to descend means guilt that leads to an experience of sadness, but in the context of the world order it is meaningful and necessary. This ambivalence of descent, which Plotinus portrays on the one hand as culpable and on the other hand as necessary to nature, is an open problem and has given rise to various attempts at interpretation in research.

A peculiarity of the doctrine of Plotinus is his conviction that the soul is only partially bound to a body, not in its entirety. It not only maintains the connection with the nous through its ability to think, but its highest part always remains in the spiritual world. Through this highest part, even if its embodied part suffers disaster, it has a constant share in the whole fullness of the spiritual world. For Plotinus this explains the relationship of the soul to the painful affects ( emotions ). The soul experiences the manifold sufferings and inadequacies of earthly existence, but in reality the affects that arise do not concern it. In terms of its nature and its highest part, the soul is free from suffering. The body as such cannot suffer either. The carrier of the affects is the organism consisting of the body and the embodied part of the soul. He is also the subject of sensory perception.

The rise of the soul

Plotinus sees the philosophical way of life as the path to the liberation of the soul. Here, too, the principle applies that the soul attains or realizes that to which it turns. When it is oriented upwards, it rises. The instructions are intended to offer Plato's teaching, which Plotinus develops from this point of view. Maintenance of virtues and constant focus on the nous are prerequisites for achieving the goal. The drive for this striving gives the soul its longing for the beautiful, because the longing directs it to the source of beauty, the nous. The beautiful does not, as the Stoics believe, consist in the symmetry of parts with one another and with the whole, because what is undivided can also be beautiful. Rather, it is a metaphysical reality to which the sensually perceptible beauty points as its image. As the sensually beautiful draws towards the spiritual beautiful, it delights and shakes the soul, because it reminds it of its own being. Beauty is causally related to soulfulness; Everything living is more beautiful than everything inanimate through the mere presence of the soul, even if a pictorial work may be far superior to a living person in terms of symmetry. Beauty in the true sense is therefore an aspect of the spiritual world and as such is not subject to a judgment based on sensory perception.

In order to be able to perceive the metaphysical beautiful, the soul must make itself beautiful and thus godlike by purifying itself. This happens by means of virtue, because virtue is an expression of the pursuit of the good and the approach to the good also leads to the beautiful at the same time, since the “light” of the good is the source of all beauty. The soul has polluted itself with ugliness, but only externally; when it removes the defilement, its preexisting natural beauty can emerge. The path leads from the physically beautiful, a very inadequate image, to the mentally beautiful and from there to the beautiful in itself that can be found in the spirit. The eros present in every soul is directed in the unphilosophical man to beauty in the sense objects, in the philosopher to the spiritual world. The love of the absolute good is even higher than the love of metaphysical beauty.

The return of the individual souls to the spiritual world does not mean that their individuality is canceled through the loss of physicality and that they become an indistinguishable part of the world soul. The principle of individuation is (the cause of individuality) namely for Plotinus not matter, but a predisposition to individuality as a natural feature of the given individual souls.

Confrontation with Gnosis

Usually Plotinus discusses different positions calmly and objectively. An exception is his confrontation with Gnosis , which he conducts with great vehemence. In addition, he remarks that an even more drastic expression is actually appropriate. He held back, however, so as not to offend some of his friends who were formerly Gnostics and now, as Platonists, incomprehensibly, continued to insist on Gnostic views.

The reason for this massive need for demarcation was that Plotinus believed that the ideas of Gnosis were a dangerous temptation for his students. Gnosis posed a challenge to Platonism because, on the one hand, its ideas corresponded to the Platonic and the gnostic striving for redemption seemed similar to the main concern of Neoplatonism, but on the other hand the Gnostics drew conclusions from the common basic assumptions that were incompatible with the Neoplatonic worldview.

Both Gnostics and Neoplatonists were of the conviction that the attachment to the body was detrimental to the soul and that it should turn away from the temptations of the sense world and strive for ascent into its spiritual home. The Gnostics, against whom Plotinus turned, assessed this finding differently than he did. From the calamity that happens to the soul in its earthly existence, they concluded that the descent into the physical world was due to an original error. This wrong decision must definitely be reversed. A final liberation from material misery, which is unnatural for the soul, should be aimed for. The physical sphere is not the lowest area of an eternal, all in all optimal universe, but the failed work of a misguided creator. The visible cosmos is not directed by a benevolent providence; rather, it is a hostile environment that deserves no respect.

Plotinus turned against this criticism of the visible world with his defense of the universal order, which also includes the visible cosmos. This is a divine creation, an admirable part of the best possible world, filled with beauty and oriented in its entirety towards the good. What may appear to be blameworthy on a superficial view is in reality necessary, since in a hierarchically graded world not everything can equally partake of the fullness of being. The world order is just because everyone receives what is due to him. Proof of wise divine guidance is the order and regularity of the processes in heaven. The Gnostics had adopted everything that was true about their teachings from Plato and the Greek philosophers of the early days, but without properly understanding and appreciating their knowledge. What they themselves added is nonsensical and outrageous. It is impossible, as they thought, to reach the goal without effort and philosophical endeavor.

Plotinus argues within the frame of reference of his own system, into which he also inserts the opposing worldview. His argument is addressed to readers who share his basic position.

logic

In logic, Plotinus criticizes Aristotle's theory of categories because it does not do justice to its claim to offer a universally valid classification of beings. He asserts that this system was devised only for the description of the sensually perceptible world; the Aristotelian scheme of ten categories is not applicable to the much more important spiritual world. The category Ousia ( substance , literally “beingness”) cannot encompass both because of the fundamental difference between the spiritual and physical modes of being. There is no definition of this category that indicates a special characteristic of being that is present in all kinds of being equally. The category of relation is said to have been created partly by ideas, partly only arose with human thought and therefore unsuitable for the world of ideas. The categories of the qualitative, the place, the situation, the time, the doing, the suffering and the having are useless for the spiritual world, since nothing corresponds to these concepts there. In addition, the ten categories of Aristotle are mere modes of expression and not the highest genera of beings. Plotinus thus turns against Aristotle's conviction that being itself appears in the various forms of the statement. He emphasizes the difference between being and its discursive expression.

For the spiritual world, Plotinus assumes a scheme of five instead of ten categories: beingness ( ousía ), movement ( kínēsis ), immutability ( stásis ), identity ( tauton ) and difference ( heteron ). These correspond to the “greatest genres” ( megista genê ), which Plato names in his dialogue Sophistes . Plotinus considers movement to be a necessity in the spiritual world, since it is an essential characteristic of living things and is necessary for thinking - beings are “nothing dead”. For the world of the senses, other categories are required, not ten, as Aristotle meant, but also only five: beingness in the improper sense (whereby “becoming” would be a more appropriate term), quantity, quality, relation and movement. One cannot speak of being here in the actual sense, since what is physically “being” is only a variable combination of matter and shape (qualities). Place and time are to be assigned to the relation, the location belongs to the place. Doing and suffering are not their own categories, but only special cases of change and thus belong to the category of movement. The category having is superfluous.

Plotinus also criticizes the stoic theory of categories in detail. In particular, he considers it nonsensical to assume an upper category “something” ( ti ), because it is heterogeneous and encompasses essentially different things (corporeal and incorporeal, being and becoming).

reception

Antiquity

The efforts of Porphyry, by far his most famous pupil, were groundbreaking for Plotin's fame and the aftermath of his life's work. Porphyrios wrote a biography of his teacher in which he reported that after Plotine's death, Amelios had asked the Oracle of Delphi about the fate of the deceased's soul and learned that she had been accepted into a realm of the blessed. By arranging, editing and publishing the writings of his teacher, Porphyrios saved them for posterity. He also put together a collection of quotations and paraphrased statements from Plotinus, the "sentences that lead to the intelligible". He also wrote explanations ( hypomnḗmata ) to Plotin’s writings and also referred to his teachings in other of his numerous works. Porphyrios thus played a decisive role in the continued existence of the new schooling established by Plotinus, which is now called "Neo-Platonism".

However, Porphyrios rejected some of Plotin's positions. In particular, he rejected his teacher's criticism of Aristotle's system of categories and thus contributed significantly to the fact that it found little approval in late ancient Neo-Platonism and was unable to influence medieval logic. In contrast to Plotinus, Porphyry believed a final separation of the soul from the material world as possible and worth striving for. This brought him closer to the Christian idea of salvation than his teacher. On the other hand, with his pamphlet “Against the Christians” he strongly criticized Christianity and thus triggered sharp reactions from the Church Fathers ; Plotinus had given him the impetus for this approach.

Amelios Gentilianos , the second best-known student of Plotinus, compiled his notes from his lectures. When he moved to the east of the Roman Empire, he took this collection, which had grown to about a hundred books, with him. It gained some popularity. The Platonist Longinos, who first taught in Athens and later in the kingdom of Palmyra as an advisor to the ruler Zenobia there , had copies of Amelios 'copies of Plotinus' writings made. Although Longinos rejected most of the basic assumptions of Neoplatonism, he expressed his deep respect for Plotin's philosophical way of working.

Iamblichus , Porphyry's most prominent student, lived and taught in the east . He emphatically contradicted various views of his teacher and thus gave the further development of Neoplatonism a somewhat different direction. Iamblichus turned against Plotinus with his rejection of his view that part of the soul always remains in the spiritual world even during its stay on earth and enjoys its fullness without restriction. He argued that then the embodied part of the soul would also have to constantly participate in the associated bliss, which was not the case. Thus, through its descent, the soul loses connection with the spiritual world. Therefore, Iamblichus was not as optimistic about the soul's ability to redeem itself on its own as Plotinus did, but rather considered it necessary to seek divine assistance through theurgy . Later Neoplatonists followed his view.

Despite widespread rejection of individual positions of Plotinus, his doctrine remained present in late ancient Neo-Platonism; the Neoplatonists quoted him in their commentaries on Plato and Aristotle. His writings also had an indirect effect through the extensive, now largely lost oeuvre of Porphyrios, which contained numerous quotations from Plotinus. Macrobius paraphrased passages of the Enneades in his commentary on Cicero's Somnium Scipionis . In the 5th century the famous Neo-Platonist Proclus commented on the Enneads ; only a few fragments of his work have survived. Although he praised Plotinus as an important Platonist, he rejected his doctrine of the substantial equality of human and divine souls as well as the identification of matter with evil.

Plotinic quotations from late antiquity were often not taken directly from his works, but came from second or third hand. From their frequency, therefore, it cannot be concluded that the original works are distributed accordingly. Some quotations contain statements that cannot be found in the Enneades or only in a very different form. Therefore, it has been suggested in research that they come from the notes of Amelios from Plotin's lessons. Proklos has demonstrably used these records.

Despite the weighty contrasts emphasized by Porphyrios between the Neoplatonic and the Christian worldview and human image, rapprochement occurred as early as the 4th century. The Neoplatonist Marius Victorinus , who converted to Christianity and translated the Enneades into Latin, played an important role in this . Its translation may have been incomplete and has not survived. The extremely influential Church Father Augustine used the Latin translation; he may have had access to the original text, but his knowledge of Greek was poor. He dealt intensively with the Plotinian neo-Platonism. Other patristic authors also received suggestions from Plotinus. The church father, Ambrose of Milan , included extensive excerpts from the Enneades in some of his works without naming the source. Cited other Christian writers who Plotinus or recycled his thoughts or formulations for their purposes, were Eusebius of Caesarea , in the Praeparatio Evangelica is extensive Enneads are -Zitate, Cyril of Alexandria , Theodoret , Aeneas of Gaza, Synesius and John of Scythopolis . However, individual content-related or even literal correspondences with texts from Plotinus do not prove that the late antique Christian author in question actually read the Enneades , because he may have relied on quotations and reproductions of content in later literature.

middle Ages

In the Byzantine Empire the original text of the Ennead was preserved; but it seems to have received little attention in the early Middle Ages . Interest aroused only in the 11th century when Michael Psellos tried to revive the Neoplatonic tradition. Psellos, a good connoisseur of Plotin, used the Enneades extensively in his works and prepared excerpts from Proklos' Enneades commentary. In the late Middle Ages , Nikephoros Gregoras quoted the Enneades and the scholar Nikephoros Choumnos, who argued from an ecclesiastical point of view, wrote a pamphlet against the doctrine of Plotinus. In the 15th century, the scholar and philosopher Georgios Gemistos Plethon , an avid supporter of Platonism, advocated some of the teachings of Plotinus.

In the Latin scholarly world of the West, the writings of Plotinus were neither in Greek nor in Latin translation. The vast majority of Porphyrios' works, including the biography of Plotinus, were also unknown. Therefore the Plotinus reception was limited to the indirect influence of his ideas, which took place above all through the very influential writings of Augustine, the Christian Neo-Platonist Pseudo-Dionysios Areopagita and Macrobius. After all, thanks to Augustine and Macrobius, some of the teachings of Plotinus were known, including his classification of virtues. In the 12th century, the theologian went Hugo Etherianus by Konstantin Opel , where he apparently the Enneads could read; he quoted them, albeit imprecisely, in a Latin theological treatise.

In the Arabic-speaking world, Arabic paraphrases of parts of the Enneades were circulating , all of which go back to a work that was written in the 9th century in the circle of the philosopher al-Kindī and has not survived in its original version. The "Arab Plotinus" influenced Muslim and Jewish thinkers. A treatise known under the misleading title "Theology of Aristotle" was particularly popular in a longer and a shorter version. It contains lengthy explanations, most of which are translations or paraphrases from Books IV – VI of the Enneades , although Plotin's statements are mixed up with foreign material and in some cases falsified. Numerous scholars, including Avicenna , wrote Arabic commentaries on "theology". A "Letter on Divine Wisdom" wrongly attributed to the philosopher al-Fārābī contains paraphrases from parts of the fifth Ennead. A fragmentary collection of sayings that was traced back to an unnamed Greek teacher of wisdom (aš-Šayḫ al-Yūnānī) is also material from the Enneades . In all of these Arabic works, Plotinus is nowhere mentioned as the originator of the ideas. His name appears very rarely in medieval Arabic literature.

Early modern age

During the Renaissance , knowledge of Plotin was initially limited to quotations from Augustine and Macrobius; more was not available to Petrarch in the 14th century and Lorenzo Valla in the 15th century . But already the 15th century in the first quarter it was possible some humanists , to Greek enneads to provide -Abschriften. They included Giovanni Aurispa , Francesco Filelfo and Palla Strozzi . However, an intensive reception of Plotinus did not set in until the end of the 15th century. The work of Marsilio Ficino was groundbreaking. Ficino translated the Enneades 1484–1486 into Latin and then wrote a commentary on them. The translation and the commentary appeared in print for the first time in Florence in 1492 and soon attracted a great deal of attention in humanist circles. In his main work, the "Platonic Theology" published in 1482, Ficino made Plotin's doctrine the basis of his ontological system. In his commentary on Plato's Dialog Symposium, he also used Plotin's ideas. In the preface to his Enneads Translation, he expressed his view that Plotinus was an excellent boom Plato dramatically: he wrote that Plato's judgment would be for Plotinus as the words of God in the Transfiguration of the Lord : "This is My Beloved Son whom I enjoy everywhere; listen to him! ”( Mt 17,5 LUT ). In his speech on human dignity, Ficino's friend Giovanni Pico della Mirandola remarked that there was nothing to be admired in Plotinus, who expresses himself divinely about the divine, because he was admirable from all sides.

In 1519 a Latin translation of the "Theology of Aristotle" appeared in Rome, which from then on was also considered an authentic work of Aristotle in the West and was included in editions of his works. This error led to Aristotle's wrongly assuming a Neoplatonic way of thinking. Although his authorship was disputed as early as the 16th century, among others by Luther and Petrus Ramus , it was not until 1812 that Thomas Taylor was able to show that “theology” is based on the Enneades .

The first, very flawed Greek Enneading edition was only published in Basel in 1580. This text remained authoritative until modern times.

In the 16th century, Plotin's doctrine of the soul provided Christian philosophers and poets with arguments for the individual immortality of the human soul. In the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, however, his reputation diminished, which had initially been very great as a result of Ficino's authority. However, his philosophy found resonance with Henry More († 1687) and Ralph Cudworth († 1688), who belonged to the group of the Cambridge Platonists . In the 18th century Plotinus was mostly little valued: theologians criticized the merging of Christianity and Neoplatonism initiated by Ficino, the religious and metaphysical questions of the ancient Neoplatonists were mostly alien to the Enlightenment . In addition, Neoplatonism was now delimited as a special phenomenon from the older traditions of Platonism and classified as a falsification of Plato's teaching. However, George Berkeley dealt with Plotinus and quoted him frequently in his writing Siris .

Modern

In the 19th and 20th centuries, Plotin’s ideas had a variety of effects, although it was often a general reception of Neoplatonism without direct reference to its founder.

Philosophy and fiction

As early as the late 18th century, a new interest in Neoplatonism had set in in Germany, which intensified around the turn of the century. From 1798 Novalis became enthusiastic about Plotinus. In 1805, Goethe asked for the Greek text of the Enneades because he was interested in the authentic terminology and was not satisfied with Ficino's translation. Goethe was particularly impressed by Plotin's remark: No eye could ever see the sun if it were not sun-like; so neither does a soul see the beautiful unless it has become beautiful. This comparison inspired him to write a poem that he first published in 1810 in the introduction to the theory of colors and in 1828 in a slightly modified version in the Zahmen Xenien : If the eye were not sun-like, / The sun could never see it; / If there were not God's own strength in us, / How can the divine delight us? In a letter to Goethe, Carl Friedrich Zelter expressed his admiration for Plotinus and stated that he definitely belongs to ours. In 1805 Friedrich Creuzer translated a text from the Enneades into German and thus contributed considerably to the spread of Plotin's ideas. In 1835 he published a new complete edition of the Enneades in Oxford together with Georg Heinrich Moser .

Hegel read the Enneades in the original Greek text; however, only the inadequate edition of 1580 was available to him. He saw the emergence of Neoplatonism as an important turning point in intellectual history, comparable to the emergence of Platonism and Aristotelianism. However, he considered Plotin's doctrine to be a preliminary stage of his own idealism and thus shortened it. Hegel ignored a central aspect of Plotin's philosophy, the absolute transcendence of the "overriding" One. For him, thinking, equated with being, was the supreme principle and therefore the nous was not different from the one. In defining the highest-ranking reality as pure being, he denied the complete indeterminacy of the One, which is important for Plotinus. He criticized that Plotinus had only expressed the emergence of the second (nous) from the one in ideas and images instead of presenting it dialectically , and that he had described what should be defined in terms as reality. Hegel's Absolute emerges from itself and then returns to itself, which is impossible for Plotin's unchangeable one.

In contrast to Hegel, Schelling understands the one (God) as “absolute indifference” in the sense of Plotinus. God never goes out of himself, otherwise he would not be absolute and thus not God. This shows Schelling's particular closeness to Plotin’s thinking, which also caught the eye of his contemporaries. However, unlike Plotinus, he lets the absolute think for itself. Schelling's idea of emanation is linked to the Plotinian one, but he regards the transition from transcendence to immanence as a free act of creation, while Plotinus traces the timeless movement from the absolute to the past to a legal necessity. Like Plotinus, Schelling assumes not only the distance from the origin but also a countermovement that leads back to the starting point. He also followed the ancient philosopher with regard to the interpretation of matter.

An assessment of Plotinus from the point of view of those aspects of his philosophy that show similarities with Hegel's system was widespread. Thinkers who disapproved of Hegel also disapproved of Plotinus. Arthur Schopenhauer criticized the Enneades in his Parerga and Paralipomena ; He complained that the thoughts were not in order, their presentation boring, rambling and confused. Plotinus is “by no means without insight”, but his wisdom is of alien origin, it comes from the Orient. The philosopher Franz Brentano , an opponent of German idealism , undertook a sharp attack on Plotin's doctrine, which consists of sheer unproven assertions, in his book What for a Philosopher Sometimes Epoch Makes .

In France, the cultural philosopher Victor Cousin did a great deal in the 19th century to deepen the interest in Plotinus and Neoplatonism. One of the thinkers there who received suggestions from Plotinus was above all Henri Bergson . Bergson's judgment on Plotin's philosophy was ambivalent: on the one hand, he shared its basic concept of unity as the cause of the existence of all multiplicity, on the other hand, he considered the Neoplatonic disdain for the material world to be wrong. Émile Bréhier , Bergson's successor at the Sorbonne , took the view that the statements of Plotinus formulated as objective metaphysical teachings were in fact descriptions of inner experiences and processes. Since Plotinus was unable to express psychological facts other than in this way, he raised his states of consciousness to levels of being. Bréhier's interpretation met with some approval, but it is opposed to the fact that Plotin's teaching is embedded in the tradition of ancient Platonism.

In the period 1787-1834 Thomas Taylor translated half of the Enneads into English. His translations of the writings of ancient Neoplatonists created an important prerequisite for the popularization of Neoplatonism in the English-speaking world. With the influence of German idealism, interest in Plotinus also grew there.

In the 20th century, Karl Jaspers dealt with Plotinus. He called him “an eternal figure of the West” and his life and thought “one of the great examples of the unrestrained power of philosophy”. On the other hand, he criticized Plotin's disregard for historicity as a limitation. Hans Jonas placed Plotinus in the spiritual flow of Gnosis. He thought that Plotin's philosophy was a gnosis transformed into metaphysics. Ernst Hugo Fischer compared questions and perspectives of modern philosophy with Plotin's approach.

Classical Studies

Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff said of philological point of view, the Enneads are a "unhellenisches" work; they lack “everything artistic, indeed everything sensual, one might say, everything physical in language”; Plotin's writing is characterized by “devotion only to the object”.

Paul Oskar Kristeller emphasized the existence of two aspects in Plotin’s thinking, one “objective” (objective-ontological) and one “actual” (subject-related).

Plotin's lack of interest in the philosophical part of Plato's teaching prompted Willy Theiler to coin the catchphrase “Plato dimidiatus” (Plato cut in half), which was received by Plotinus; not only is politics missing, but also “what is actually Socratic” as a whole.