Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius

Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius (the order of the names varies; * probably around 385/390; † probably after 430) was an excellently educated late antique Roman philosopher and grammarian . In the Middle Ages, his work played an important role in conveying ancient education. What is certain is that he was a high official, but the question of whether he can be identified with one of the well-known officials of the same name has been the subject of controversial research for decades and remains open. He was a conservative representative of the Neoplatonic worldview. He did not comment on Christianity.

His three works - the Saturnalia ("Saturnalia"), a commentary on Cicero's Somnium Scipionis and a grammatical script that has only survived in excerpts - were probably created in the second and third decades of the 5th century. The Saturnalia describe the conversations at a banquet in the late 4th century. They idealize the scholarship of the conservative personalities of the “Symmachus circle” around Quintus Aurelius Symmachus and show the reader how tradition was maintained in this milieu. The Cicero Commentary, in which the Somnium Scipionis is interpreted from the Neoplatonic point of view, was one of the most popular ancient works in the Middle Ages.

Life

Very little is known about the life of Macrobius; assumptions about his origin are speculative. A casual statement in the Saturnalia indicates that he did not come from Italy. His use of Greek shows that it was not his mother tongue. An African origin has been repeatedly suggested since the 19th century.

His title vir clarissimus et illustris , handed down in the manuscripts of the Saturnalia and the Cicero Commentary , shows that he was of senatorial rank and held very high offices. As can be seen from his works, he was a follower of the Neoplatonic philosophy, which at that time served the educated opponents of the Christian state religion as the basis of their religious worldview. Macrobius avoided commenting on the religious conflict. He did not attack Christianity, not even indirectly, but consistently withheld it.

Macrobius had a son who was named Flavius Macrobius Plotinus Eustathius and was prefect of Rome ( praefectus urbi ) in the sixties of the 5th century . A scholar by the name of Macrobius Plotinus Eudoxius, who with Quintus Aurelius Memmius Symmachus reviewed and corrected a copy of Macrobius' commentary on the Somnium Scipionis before 485 in Ravenna , was probably a grandson of the writer. Already in an Egyptian papyrus of the early 4th century from Oxyrhynchos the names Makrobios and Eudoxios appear close together; therefore it has been assumed that the writer Macrobius and his grandson Eudoxius belonged to a family of Upper Egyptian origin, in which these two names were traditionally in use.

The question of whether the writer can be identified with people of the same name known elsewhere has been the subject of intense research. Their answer has consequences for the dating of his life and works. Several high officials mentioned in the Codex Theodosianus have been considered: a Praetorian prefect , a proconsul of the province of Africa , a vicarius of Hispania and a chief chamberlain ( praepositus sacri cubiculi ) in Constantinople . Some researchers have assumed that the latter three are the same person, but this assumption has been proven erroneous.

- The chief chamberlain and vir illustris Macrobius is attested in 422 as the reigning praepositus sacri cubiculi . Since the holder of this office was always a eunuch , this chief chamberlain cannot, as was previously assumed, be identical with the pagan writer who had descendants.

- There is evidence that the Vicarius of Hispania Macrobius was in office in 399 and 400. At that time he did not have the title vir illustris . Since he was reprimanded for exceeding his competence, it is unlikely that he would later have had a brilliant career and rose to the exclusive circle of the viri illustres . Therefore he is unlikely to be identical with the writer.

- A Macrobius was 410 proconsul of the province of Africa. Since, like the writer, he was a top Pagan official and the presumed age is appropriate, the equation is considered a plausible assumption.

- For the Praetorian prefect (praefectus praetorio Italiae, Illyrici et Africae) , who is attested in 430, only the name Theodosius has survived. But that does not speak against his identity with the writer Macrobius, whose nickname may also have been Theodosius. The argument for the identity hypothesis is the high office that suits the writer.

Probably the Theodosius, to whom the poet Avianus dedicated his fables, is the writer Macrobius.

Works

The dating of the three known works by Macrobius is uncertain. First, when he was not yet vir illustris , he wrote the grammatical treatise; it was probably created between 420 and 430. His second work were the Saturnalia , which he dedicated to his son Eustathius when he was still a school child. When Macrobius dedicated the third work, the Commentary on the Somnium Scipionis , to Eustathius, his son was already a young man who could receive a philosophical education, that is to say about twenty years old. Hence the commentary is dated about five to ten years later than the Saturnalia . The twenties and thirties of the fifth century are now considered to be the likely period for the writing of these two works.

Macrobius proves to be a skilful stylist who knows how to express himself in sophisticated but not artificial language. He knows how to organize his material skillfully. He emphatically asserts his conservative attitude; For him, Homer and Plato , Virgil and Cicero are authorities of the highest order and representatives of a unified, undoubtedly correct doctrine of wisdom.

Saturnalia

Literary design and sources

The Saturnalia are the last known ancient work of the genre of the symposium literature, which reproduces fictional conversations at guest meals. The author uses this framework to present knowledge from different areas. He used Plato's symposium as a formal model . The conversations are said to have taken place during the festival of Saturnalia . Macrobius shows prominent historical figures of the late 4th century. Among the participants are influential urban Roman representatives of the pagan educational tradition: the senators Vettius Agorius Praetextatus († 384), Quintus Aurelius Symmachus and Virius Nicomachus Flavianus . The still young grammarian Servius , who later emerged as the author of comments on the three great poems of Virgil, also belongs to the select group. There are twelve people, but not all of them are constantly present; mostly Romans, but also some Greeks and an Egyptian. By having an Egyptian guest named Horus appear, Macrobius creates an opportunity to discuss Roman institutions unknown to the Egyptian. Horus represents cynicism in the group .

In reality, a banquet with this group of guests cannot have taken place, because two participants, including Servius, were too young as historical persons to be considered as conversation partners of the other. Macrobius consciously accepts this chronological inconsistency, referring to the example of Plato's dialogues in the preface to justify the literary anachronism .

The individual dialogue partners receive an individual profile and sometimes have different convictions, but the course of the conversation lacks the drama, because there are no controversies. However, embarrassing situations arise because one participant in the conversation, Euangelus, provokes the rest of the audience with his rudeness and disrespect and puts their patience to the test without being able to upset them with his mocking and even insulting remarks. His presumptuousness and incompetence are objectively and deliberately rejected; in this way, the social hierarchy that is disturbed by improper behavior is defended emphatically among those present, while maintaining the manners.

A wide range of topics, especially from the areas of cultural history, mythology , religious customs and philology is discussed . The interlocutors link the cultural-historical with the philological questions by repeatedly addressing the use of language and the etymology and history of individual terms. They show their erudition by sprinkling numerous quotations from Greek and Roman poetry and specialist literature. Since these include quotations from works by older authors that are now lost, the Saturnalia are a valuable source of literary history. From this point of view, ancient scholars particularly appreciate the Saturnalia , especially since Macrobius is used to quoting correctly and sometimes reproduces the exact wording. In reality, however, his reading is not as impressive as the diversity of the cited authors suggests, because he probably did not have a large part of the literature he names in his hands. He probably knew many works, the original texts of which had long been lost, only indirectly from sources in which collections of excerpts and quotations had already been put together. He does not name these intermediate sources. Among the works he used are the Noctes Atticae des Gellius , Letters from Seneca and Plutarch's Quaestiones convivales . Macrobius took a lot of material from the Noctes Atticae without ever giving this source.

Macrobius divides his work into seven books. The text has not survived in full; the end of the second, fourth, sixth and seventh book is missing, the beginning of the third and fourth.

content

The Saturnalia are a festival that lasts several days and is celebrated together by the cultivated participants; the mornings are devoted to serious discussion, in the afternoons they are devoted to cheerful conversation. The talks begin on the eve of the festival, December 16, in the house of Vettius Agorius Praetextatus and continue on the first day of the festival with the same host (books 1 and 2). On the second feast day Virius Nicomachus Flavianus is the host (Book 3), on the third and last day Quintus Aurelius Symmachus (Books 4–7). The fictitious conversations are not told from the perspective of someone present, but from that of a reporter named Postumianus, who himself did not take part in the symposium because he was invited but prevented. Postumianus states that he is based on the presentation of the conversation partner Eusebius, who described the course to him on the day of the winter solstice , a few days after the Saturnalia. This constellation corresponds to that of Plato's symposium .

- In the preface Macrobius turns to his young son, for whom the work is intended, and explains his intention. In the introduction he states that the upbringing of children is felt to be the most important of the tasks that nature sets man. Nothing else causes greater joy when successful and deeper sadness when failed. That is why he put together the educational material that he had acquired from Greek and Latin literature in the course of his life in a manual and organized it appropriately so that it was now clearly presented. Macrobius does not claim to be original in terms of content. He sees the merging of the diverse material into a unified whole as his own achievement, the value of which he emphasizes. He compares himself to the bees whose collecting activity he has imitated; like her, he not only compiled, but also processed what had been collected. From the diverse chorus of voices of the quoted authors a harmony emerges. In this way Macrobius distinguishes himself indirectly from Gellius, who admits in the preface to his Noctes Atticae that he did not try to present the material in a well thought-out, orderly manner .

- In the first book , the conversation begins on the eve of the festival with the discussion of when the Saturnalia begin, i.e. when the transition from one day to the next is to be made. This question gives rise to linguistic considerations. On the first day of the festival, the starting point of the conversation is the question of the nickname ( cognomen ) of the host Praetextatus, which is derived from the toga praetexta . The description of the historical background of this name is followed by the explanation of other epithets. Horus, the Egyptian guest, asks about the origin of Saturnalia and the Roman cult of Saturn ; the answer he receives describes the early mythical history of the worship of the god Ianus . Since slaves are allowed to be cocky at Saturnalia, which is offensive to a person in the conversation, the human dignity of slaves becomes an issue. Then comes the division of the year into months, the authors of which were believed to be the kings Romulus and Numa Pompilius , the Roman calendar system , Caesar's calendar reform , the holidays and customs associated with certain days. The next big issue is the worship of the sun as a deity; the various names of the sun god Sol are discussed . Sol is equated with Apollo and other traditionally revered gods, so that conventional Roman polytheism approaches the monotheistic concept of God of the ruling Christianity. After quoting verses from Virgil's Georgica and Euangelus, a disrespectful critic of the famous poet whose expertise he has doubted, the conversation turns to Virgil, whose poetry becomes the main theme later on. The aim is to clarify the extent to which Virgil's works are not only suitable as school reading, but also contain a deeper meaning and can thus serve to teach adults. For this purpose, the topic should be examined from different angles. Therefore, eight of the scholars present take on the task of making a contribution according to their particular expertise by each lecture on a specific aspect. This involves both linguistic and content-related aspects and Virgil's role as a transmitter of Greek literary tradition.

- In the only incompletely preserved second book , those present put together a wealth of anecdotes and funny sayings from Roman literature that they can spontaneously remember. These include many sayings ascribed to Cicero and Augustus or allegedly addressed to Augustus. In the evening, starting with the topic of wine consumption, a discussion about lusts begins, with reference to Aristotle's theory of lust ; most of that conversation is lost.

- The Books 3-6 are devoted primarily Virgil. The third book is about his religiosity, his knowledge of the Roman cult and his descriptions of rites, the fourth book about his portrayal of emotional excitement. The fifth book explains what Virgil owes to his Greek models, primarily Homer. The sixth book is about Virgil's relationship with the Roman poets, from whose works he was inspired, as well as his style and vocabulary. Here the competence of the philologist Servius, who explains difficult yellow spots, proves to be helpful. The main concern of Macrobius is the glorification of the education, wisdom and linguistic art of Virgil, who appears as the model of a versatile poet. No praise could increase Virgil's fame, no blame could lessen him. Although the admiration of Virgil is not unanimous, because Macrobius also lets the Virgil critic Euangelus appear among the participants, but his attack on the authority of the poet in the first book only leads to the fact that in the further course of the conversations Virgil is placed in a more favorable light .

- The seventh book contains cheerful conversations on the afternoon of the last feast day. Banquet participants raise a variety of topics, including various types of ridicule and nutrition issues. Macrobius has the philosopher Eustathius defend Plato's view against the physician Disarius, according to which drinks do not travel via the esophagus to the stomach and from there into the intestines, but via the trachea to the lungs and from there to the bladder; accordingly, only solid foods get into the stomach. Aristotle had already rejected this opinion, presented in Plato's dialogue Timaeus . After discussing this subject, the mock and troublemaker Euangelus makes fun of philosophy by asking whether the egg or the hen came first; to his surprise, he received a serious, detailed answer with arguments for both positions.

Commentary on Cicero's Somnium Scipionis

The commentary on Cicero's “Dream of Scipio” (Somnium Scipionis) has survived in its entirety; it comprises two books. A story from the sixth and last book of Cicero's De re publica is commented on . She describes a dream in which in the year 149 BC The famous Roman general Scipio Africanus , the "older Scipio", his adoptive grandson, the "younger Scipio" ( Scipio Aemilianus ), appears. The deceased general teaches his descendants in a dream about the life of the soul after death, the nature of the cosmos and the earth and the future fate of the Roman people. This part of De re publica may have been handed down and read as a separate work as early as the 5th century. Macrobius, however, still had access to a complete copy of the now largely lost treatise De re publica .

Macrobius refrains from reproducing the entire annotated text section by section in his commentary or, as medieval copyists later did, adding it as an appendix. His commentary does not systematically deal with the entire story, but only selected passages, because his interest is in the philosophical content, not the literary aspects. He takes up the subject from his Neoplatonic perspective and tries to harmonize Plato's philosophy with the worldview of Somnium Scipionis . In doing so, he takes individual remarks in the commented text as an opportunity for detailed discussions that provide information about his worldview, but are in part only loosely related to Cicero's concerns. He underlined the Neoplatonic character of his world of thought with praise for the leading Neoplatonists Plotinus and Porphyry ; He considers Plotinus and Plato to be the most important philosophers, and he is heavily influenced by Porphyrios.

The main subjects of the commentary include the nature of the soul, its virtues, its self-movement and immortality, as well as its present and future position in the cosmos. Following on from Cicero's remarks on the universe, Macrobius goes into detail on cosmology and astronomy. He also deals in detail with the fundamentals of musical harmony , the Pythagorean doctrine of the harmony of the spheres , geography and the cosmic cycle (" Great Year "). His style of expression is characterized by an always noticeable effort to achieve the greatest possible clarity.

As with the Saturnalia , it cannot be assumed here either that Macrobius actually read all of the works he quotes. Rather, he owes a considerable part of his knowledge to existing text collections, comments or manuals.

Dream doctrine

The commentary begins with a comparison between Scipio's dream and the myth of Er in Plato's dialogue Politeia , which was the literary model for Cicero. Macrobius then discusses the role of myth in literature and philosophy and the world of dreams. He presents a classification of dreams, whereby he first distinguishes between two main groups: meaningful dreams, which require an interpretation from a competent side, and meaningless dreams. These main groups are further subdivided. Macrobius counts the dream “in the real sense” (proprie) , which expresses a real situation with symbols, the vision (visio) , in which one foresees something as it actually occurs later, and the dream oracle (oraculum ) , in which an authority figure or even a god announces to the dreaming that something will happen or be omitted or that something should be done or omitted. In the real sense of the dream, Macrobius distinguishes five subspecies, depending on the actors and scenes of the dream plot.

Soul teaching

Macrobius describes in detail the phases of the soul's descent from its heavenly home, which he localizes in the area of the Milky Way , through the seven planetary spheres to earth, where it attains its physical shell. According to Macrobius' conviction, this descent is necessarily always a catastrophe for the soul from the beginning, because it ends up in an underworld. During the descent it loses its original divine, simple, undivided form and acquires an expanded and divisible shape, whereby it is subject to the influence of matter and loses its original knowledge. This knowledge is replaced by reflection and the striving for insight. The reason for the descent lies in the soul itself; not an external influence, but an own impulse induces them to direct their thoughts to the body and an earthly life and to develop a desire for them. Due to the weight of these thoughts it sinks, with which it begins to slide down to earth. Thus she is plunged into misery by her first mistake, the original offense, to desire physicality. Each phase of the descent is experienced by the soul as a death; the final and worst death is entry into the body. However, the descent is reversible; through remembrance - which is difficult to attain - the soul can escape from oblivion and recognize its origin. Then she can succeed in regaining her initial state of perfect integrity and bliss and return to her home. If it is not able to do this, it remains subject to the cycle of transmigration of souls . As long as it is in the body, it has to fulfill its associated tasks; she must not cause the death of the body on her own, because that would interrupt her purification process and act under the compulsion of affects, which means bondage.

Macrobius takes over most of his theory of the soul from Porphyrios; In part, his concept can be traced back to the teaching of the Middle Platonist Numenios , which has only been handed down in fragments . Furthermore, a similarity between his conception of the fate of the soul and the ideas of the Chaldean oracles can be seen . He is convinced that the human soul is not only immortal, but a deity. However, this insight should be reserved for those who have come to self-knowledge, because otherwise the transient in humans would also be mistakenly held to be divine.

Macrobius goes into detail on eight objections made by Aristotle to the Platonic concept of the soul. In the introduction he explains that he is based on arguments of important Platonists that he has collected. It is beyond his competence to make a judgment on the basis of his own knowledge and to contradict the opinion of Aristotle, but he can at least contribute some considerations. With his demonstrative modesty he distances himself at the same time from the authorities to which he appeals and to whom he assumes a strong self-confidence and need for recognition.

ethics

Macrobius' doctrine of virtue is shaped by traditional Roman ideas, above all by Cicero's ideas. In this it differs from that of the Greek-speaking Neo-Platonists. Macrobius assigns the political virtues a more important role than Plotinus and Porphyry. As a commentator on the Somnium Scipionis , he comes across a contradiction between the position of Cicero and that of the Neoplatonists. Cicero offers the statesman especially the prospect of eternal heavenly bliss as a reward for services to the fatherland. The Greek-speaking Neo-Platonists, on the other hand, do not give the statesman priority over other virtuous people and teach that the only way to happiness is the philosophical life devoted to theory. Macrobius tries to defuse the contrast; he clings to the primacy of specifically philosophical virtues, but emphasizes the ethical value of political practice.

cosmology

In cosmology, Macrobius, as was common at the time, localized the earth in the center of the universe. The immobile earth is surrounded by seven planetary spheres - rotating concentric spheres that each carry a planet. The sun and the moon are considered to be planets. The eighth sphere is the carrier of the fixed stars; For Macrobius, their movement is the measure of the “Great Year”, the length of which he - unlike all other ancient authors - specifies as 15,000 years. He is the only ancient writer to deviate from the then common definition of the Great Year, which makes the return of all planets to their starting positions the only criterion for the completion of a Great Year, without taking into account the precession cycle of the fixed stars.

Macrobius agrees with the view of those Platonists who consider only the outermost sphere, that of the fixed stars, to be absolutely unchangeable and who count the planetary spheres as the area in which growth and decay take place. In doing so, he contradicts the view, mainly held by the Aristotelians , according to which the area of transience only begins below the lunar sphere and the planets belong to the upper world, which is not subject to any change. Macrobius regards all growth and decay as a change in appearance; He excludes destruction as annihilation that ends being.

When it comes to the order of the planets, Macrobius opts for the "Egyptian" model represented by Plato, in which the solar sphere is located directly above the lunar sphere; thus the sun takes second place when viewed from the earth. In Plato the order is from the inside out: Earth, Moon, Sun, Venus, Mercury, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn; in the variant of Macrobius, the places of Mercury and Venus are exchanged. The alternative model is the “Chaldean” Ciceros, in which the solar sphere takes the fourth, middle position among the seven planetary spheres (order: Earth, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn). Macrobius does not reject Cicero's alternative, rather he regards the contradiction between the two models as apparent and tries to resolve it with the help of the epicyclic theory ; Due to the epicyclic movement, Mercury and Venus appear at times below and at times above the sun.

In the controversial question of the origin of the world ( cosmogony ) he defends the doctrine of the beginning and endlessness of the world and its cycles, which prevailed among the Neoplatonists. Accordingly, he considers the course of history to be cyclical rather than linear progressive. For him, this position is the doctrine of “philosophy” par excellence about the eternity of the world.

Macrobius regards man as a microcosm (“small world”, brevis mundus ), the cosmos as “great man”, since there is an analogy between man and cosmos.

geography

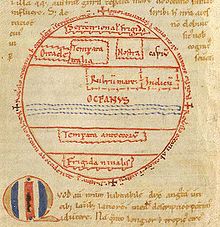

Macrobius' geographical views include the conviction that in addition to the part of the earth's surface that was known and populated at the time, there are three other parts of the world whose inhabitants are separated from the part known to him by insurmountable natural obstacles. The other side of the globe is said to be inhabited by the antipodes ("antipods").

Grammatical treatise

Only excerpts have been preserved from the grammatical treatise "On the differences and similarities between Greek and Latin verbs". The traditionally common title is De differentiis et societatibus Graeci Latinique verbi , but the editor Paolo De Paolis has shown that the authentic title was probably worded a little differently: De verborum Graeci et Latini differentiis vel societatibus . Comparisons between the Greek and Latin languages were a popular subject for grammarians of late antiquity. Macrobius limited himself to part of the extensive subject, the comparison of verbs. His systematic questioning of the differences (differentiae) was a methodological innovation in the study of Latin grammar. He said that anyone who has learned the grammar of one language largely understands that of the other. His treatise is a compilation of works by previous authors, including Apollonios Dyskolos and Gellius; an unknown, now lost Latin source is to be assumed.

reception

Late antiquity and the Middle Ages

Commentary on the Somnium Scipionis

In late antiquity and in the pre-Carolingian Middle Ages, the comment seems to have received only sporadic attention. The hypothesis that there are reminiscences in the works of the Church Fathers Ambrosius and Hieronymus Macrobius lacks a convincing justification. Boethius relied in his commentary on the Isagoge of Porphyry on the work of Macrobius, and also in his Consolation Philosophiae to use of that source is identified. Cassiodorus referred to Macrobius' compilation of philosophical positions on the doctrine of the soul in his commentary on the psalms.

Whether Isidore of Seville , Bede and the author of the Cosmographia (Pseudo- Aethicus Ister ) had access to Macrobius' writing cannot be clearly established. Only in the time of the Carolingian renewal did the reception begin to be clearly recognizable. The early medieval scholars were mainly interested in the astronomical explanations of Macrobius, which were studied, among other things, in connection with the calculation of Easter ( computus ), as well as music theory. In 811, Irish scholar Dungal wrote a letter to Emperor Charlemagne answering a request from the ruler on the phenomenon of the solar eclipse, quoting at length Macrobius' Cicero comment. The scholars Lupus von Ferrières and Heiric von Auxerre took part in the preparation of a copy of the commentary, which is now in Paris. The French Benedictine Abbey of Fleury was a center of early medieval Macrobius studies , with the abbot Abbo of Fleury providing important impulses.

A section from the commentary on the Somnium Scipionis , which deals with musical intervals , was also distributed separately under the title De symphoniis musicae ("On the harmonies of music"). The early medieval music theorist Regino von Prüm quoted this text.

The handwritten tradition begins in the 8th century; at that time the oldest text witness was created, a codex from Bobbio Abbey , an Irish foundation in northern Italy. It contains excerpts in Irish minuscule . Six of the surviving manuscripts date from the 9th century; eight more were made in the 10th century, 31 in the 11th century. In the 12th century the spread of the work reached its peak; at that time, 106 of the 230 copies still available today were made between the 9th and 15th centuries. The medieval library catalogs, which give a reliable impression of the book holdings, also show that the cultural renewal, which is often referred to by the controversial term “ Renaissance of the 12th century ”, gave the reception of the Cicero commentary a strong boost.

In the High Middle Ages , the commentary on the Somnium Scipionis played a key role in the inclusion of Neo-Platonic ideas, especially in the field of cosmology. He also made an important contribution to the dissemination of Cicero's story. Petrus Abelardus dealt intensively with the cosmology of Macrobius; he counted the scholars of late antiquity together with Socrates , Plato, Pythagoras , Cicero and Virgil among the first-rate philosophers. Avid users of Macrobius' work were primarily writers who belonged to the current of the Platonic " School of Chartres " or to its circle, including Wilhelm von Conches , Bernardus Silvestris , Johannes von Salisbury and Alanus ab Insulis .

Macrobius's views on geographic issues were also influential. The medieval copies of his Cicero commentary contained maps that were important for the development of medieval cartography . Numerous medieval maps, especially from the 12th century, go back to his explanations; no other ancient author shaped the geographical worldview of the Middle Ages more strongly than Macrobius. His false explanation of the tides , which he attributed not to the influence of the moon, but to a collision of ocean currents at the poles, attracted much attention . His doctrine of the antipodes, whose living space on the other side of the globe is in principle inaccessible from the known part of the earth, aroused offense in theological circles. It was attacked because its consequence is that the Christian message cannot be spread among the antipodes.

The commentary on the Somnium Scipionis also influenced the high and late medieval dream theories and ideas of dream interpretation. Macrobius' division of dreams was one of the three most influential dream classifications alongside those of Calcidius and Gregory the Great . His dream theory was also noted in the vernacular literature; Guillaume de Lorris referred to it in the rose novel and Geoffrey Chaucer mentioned Macrobius in this context in several of his works.

Another area in which the commentary on the Somnium Scipionis had a broad impact in the High Middle Ages was the doctrine of virtues. The definition and classification of virtues conveyed by Macrobius was taken up by moral theorists.

The strong interest in the commentary was also reflected in the need for an explanation of text passages in need of explanation, which was sometimes satisfied by extensive glosses . Wilhelm von Conches wrote Glosae super Macrobium ("Glosses on Macrobius"), and in a codex from the 12th century, anonymous glosses have been passed down, which mainly focus on "classical" topics of Platonism such as the world soul , the theory of ideas , the relationship between the Relating soul to body and cosmological issues. In manuscripts the text of Macrobius was sometimes preceded by accessus (introductions), which are informative sources for the medieval Macrobius reception.

However, Macrobius did not only find admirers in the High Middle Ages. Manegold von Lautenbach , a polemic opponent of the educational system based on pagan ancient literature, attacked him in the late 11th century as a dangerous mediator of unchristian ideas. In his Liber contra Wolfelmum he pointed out the incompatibility of the cosmology of the late ancient Neo-Platonist with the biblical. On the other hand, he found Macrobius' doctrine of virtue acceptable. Among the critics was also the monk Helinand von Froidmont, who worked as a writer in the late 12th and early 13th centuries. In a treatise on self-knowledge, he fought the theory of the soul in the commentary on the Somnium Scipionis .

Macrobius's broad reception continued in the late Middle Ages. The authors who extensively cited the Cicero Commentary include the eminent encyclopedists Vinzenz von Beauvais and Thomas von Cantimpré , who wrote a highly regarded handbook “ On the Nature of Things ”. Albert the Great dealt mainly with the anthropology and theory of the soul of Macrobius, Thomas Aquinas and Bonaventure dealt with his views on ethics.

The Cicero commentary even reached the Byzantine world in the late Middle Ages ; the scholar Maximos Planudes translated it into Greek together with Ciceros Somnium Scipionis . The translation of the Planudes, which has come down to us in around twenty manuscripts, is of poor quality, however, since the transmission of the meaning has often fallen victim to the pursuit of literal translation.

Saturnalia

The Saturnalia were also hardly known in the early Middle Ages; It is unclear whether Isidore of Seville had a copy available. Beda used a short compilation of excerpts that circulated under the title Disputatio Hori (or Chori ) et Praetextati ("Debate between Horus and Praetextatus"). Like the Cicero commentary, the Saturnalia owed their rediscovery to the Carolingian renewal; the six oldest surviving manuscripts date from the 9th century; Lupus von Ferrières was familiar with the work. In the centuries that followed, the Saturnalia received some attention (particularly from John of Salisbury), but far less than the Cicero Commentary. Only 46 manuscripts have survived from the 10th to the 14th century. Interest only intensified in the Renaissance; 61 copies from the 15th century are still available today, more than half of the entire handwritten tradition.

Grammatical treatise

The oldest surviving manuscript, dated to the 7th or 8th century, comes from Bobbio. In the 9th century a John, most likely the Irish scholar Eriugena , compiled excerpts from the grammatical treatise known as the "Parisian Excerpts ." Early medieval Irish who studied the work apparently viewed it as an aid in attempting to learn Greek.

Early modern age

Macrobius found esteem among humanists as early as the early humanist era . Petrarch , who was particularly interested in his doctrine of virtues, called him an excellent writer and quoted him in letters, Coluccio Salutati studied the Cicero Commentary thoroughly and also knew the Saturnalia . The philosophical appreciation of political activity in the Cicero Commentary found approval in humanist circles because it accommodated the inclinations of the Renaissance humanists.

The Saturnalia and the Commentary on Somnium Scipionis were first printed in Venice in 1472. Johannes Opsopoeus published the first edition of the “Parisian Excerpts” from the grammatical script in 1588 in Paris. Numerous prints of Macrobius' works appeared in the late 15th and 16th centuries, but interest in him waned significantly in the 17th and 18th centuries. Cervantes used ideas from the Cicero commentary for his Don Quixote .

Modern

Modern Macrobius research has long been hampered by a chronological error. The Saturnalia was dated to the late 4th century. Therefore, this work was used in numerous cultural-historical studies as an important source for the pagan reaction of the time to the advance of Christianity. Jelle Wytzes and Herbert Bloch particularly emphatically assigned the Saturnalia a role as a cultural weapon in the final phase of the religious-political struggle. It was believed that Virgil's poetry was stylized as a counter-Bible. According to current research, however, the Saturnalia did not emerge until the second decade of the 5th century at the earliest, when the struggle was over and the Christianization of the empire was much further advanced. Macrobius therefore did not pursue the political goals previously ascribed to him, but rather idealized in retrospect a generation of scholars who had already belonged to the past.

One of the main topics of research is the question of the extent to which Macrobius is independent from the literature he has consulted. It is not easy to answer, as much of its sources are lost. Depending on the assessment of his handling of the sources, the judgments about his philosophical and literary achievement vary. In the 19th and early 20th centuries he was a "victim of source research" (Jacques Flamant); He was mostly viewed - especially by German antiquity - as a mere collector of foreign material, the origin of which had to be clarified. Even then, efforts began to identify and appreciate his own contribution; From the thirties of the 20th century, this approach gained increasing supporters (Paul Henry, Karl Mras , later mainly Jacques Flamant).

Macrobius' role in the history of astronomy has been recognized by naming a lunar crater after him. The Macrobius Cove is also named after him, a bay in Graham Land in Antarctica.

Editions (partly with translation)

- Friedrich Heberlein (Ed.): Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius: Commentary on the Somnium Scipionis. Steiner, Stuttgart 2019, ISBN 978-3-515-12365-5 (edition without critical apparatus, Latin text largely based on the edition by Armisen-Marchetti, with German translation and explanations by the editor and introduction by Christian Tornau )

- Robert A. Kaster (Ed.): Macrobii Ambrosii Theodosii Saturnalia . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2011, ISBN 978-0-19-957119-2 (critical edition).

- Robert A. Kaster (Ed.): Macrobius: Saturnalia (= Loeb Classical Library. Volumes 510-512). 3 volumes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts) 2011, ISBN 978-0-674-99649-6 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-674-99671-7 (Vol. 2), ISBN 978-0-674-99672 -4 (Vol. 3) (text edition and English translation).

- James Willis (Ed.): Ambrosii Theodosii Macrobii Saturnalia . Teubner, Stuttgart / Leipzig 1994, ISBN 3-8154-1527-6 (critical edition, improved version of the 2nd edition from 1970).

- James Willis (Ed.): Ambrosii Theodosii Macrobii commentarii in somnium Scipionis . Teubner, Stuttgart / Leipzig 1994, ISBN 3-8154-1526-8 (critical edition, unchanged reprint of the 2nd edition from 1970; this edition was heavily criticized by reviewers).

- Mireille Armisen-Marchetti (Ed.): Macrobe: Commentaire au Songe de Scipion . 2 volumes. Les Belles Lettres, Paris 2003, ISBN 2-251-01420-3 and ISBN 2-251-01432-2 (authoritative critical edition with French translation and commentary).

- Paolo De Paolis (Ed.): Macrobii Theodosii De verborum Graeci et Latini differentiis vel societatibus excerpta . Quattro Venti, Urbino 1990, ISBN 88-392-0181-5 (critical edition).

Translations

German

- Ambrosius Theodosius Macrobius: Table discussions at the Saturnalia Festival . Translated by Otto and Eva Schönberger. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-8260-3785-6 .

English

- Macrobius: Commentary on the Dream of Scipio. Translated by William Harris Stahl. Columbia University Press, New York 1952; Reprint: Columbia University Press, New York 1990, ISBN 978-0-231-09628-7 .

greek (medieval)

- Maximus Planudes: Macrobii commentariorum in "Somnium Scipionis" libri duo in linguam Graecam translati. Edited by Anastasios Megas. Art of Text, Thessaloniki 1995, ISBN 960-312-047-2 (critical edition of the Middle Greek translation of the Planudes with the Latin text).

literature

about the author and the works

- Philippe Brugisser : Macrobius . In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity . Volume 23, Hiersemann, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-7772-1013-1 , Sp. 831-856.

- Alan Cameron : The Last Pagans of Rome . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2011, ISBN 978-0-19-974727-6 , pp. 231-272.

- Jacques Flamant: Macrobe et le neo-platonisme latin, à la fin du IV e siècle . Brill, Leiden 1977, ISBN 90-04-05406-5 .

- Pedro Pablo Fuentes González: Macrobius . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques . Volume 4, CNRS Éditions, Paris 2005, ISBN 2-271-06386-8 , pp. 227-242.

- Stephen Gersh: Middle Platonism and Neoplatonism. The Latin Tradition . Volume 2, University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame (Indiana) 1986, ISBN 0-268-01363-2 , pp. 493-595.

- Ekkehart Syska: Studies on theology in the first book of Saturnalia by Ambrosius Theodosius Macrobius . Teubner, Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-519-07493-1 .

to the reception

- Bruce C. Barker-Benfield: The manuscripts of Macrobius' Commentary on the Somnium Scipionis . Corpus Christi College, Oxford 1975 (dissertation).

- Franz Brunhölzl : Macrobius. 1. In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages . Volume 6, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-7608-8906-9 , column 63 f.

- Albrecht Hüttig: Macrobius in the Middle Ages. A contribution to the history of the reception of the Commentarii in Somnium Scipionis . Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1990, ISBN 3-631-40608-8 (dissertation).

- Daniel Pickering Walker: The Ancient Theology. Studies in Christian Platonism from the Fifteenth to the Eighteenth Century. Duckworth, London 1972, pp. 14-16, 22-41.

- Clemens Zintzen : Comments on the aftermath of Macrobius in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. In: Michael Wissemann (Ed.): Roma Renascens. Contributions to late antiquity and reception history. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-8204-0979-3 , pp. 415-439.

Web links

- Literature by and about Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by Macrobius in the German Digital Library

- Macrobius: Saturnalia (Latin text from the edition by Ludwig von Jan [1852], web edition by Bill Thayer at LacusCurtius )

- Macrobius: Saturnalia and Commentary on Somnium Scipionis (French translation)

Remarks

- ↑ For the correct order see Alan Cameron: The Date and Identity of Macrobius . In: The Journal of Roman Studies 56, 1966, pp. 25–38, here: 26; Mireille Armisen-Marchetti (Ed.): Macrobe: Commentaire au Songe de Scipion , Vol. 1, Paris 2003, p. VIII; Bruce C. Barker-Benfield: The manuscripts of Macrobius' Commentary on the Somnium Scipionis , Oxford 1975, p. 3.

- ↑ Macrobius, Saturnalia 1, praefatio 11: nos sub alio ortos caelo ("we were born under another heaven").

- ↑ Mireille Armisen-Marchetti (Ed.): Macrobe: Commentaire au Songe de Scipion , Vol. 1, Paris 2003, pp. X f.

- ↑ Mireille Armisen-Marchetti (Ed.): Macrobe: Commentaire au Songe de Scipion , Vol. 1, Paris 2003, pp. XVIII f .; Pedro Pablo Fuentes González: Macrobius . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Vol. 4, Paris 2005, pp. 227–242, here: 231 f. Most of the research is of the opinion that Macrobius was a follower of the ancient Roman religion. Michele Bevilacqua contradicted this: Introduzione a Macrobio , Lecce 1973, pp. 23–32, who said that he might have been nominally Christian. This hypothesis was put forward again by Alan Cameron: The Last Pagans of Rome , Oxford 2011, pp. 265-272. See the summary of the arguments for the various research opinions in Philippe Brugisser: Macrobius . In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christianentum , Vol. 23, Stuttgart 2010, Sp. 831–856, here: 842–852. There is agreement in research that a belief in Christianity may have been only very superficial.

- ↑ Not, as a different spelling goes, Eustachius; see Mireille Armisen-Marchetti (Ed.): Macrobe: Commentaire au Songe de Scipion , Vol. 1, Paris 2003, pp. XIV f.

- ↑ On him see Jacques Flamant: Macrobe et le neo-platonisme latin, à la fin du IV e siècle , Leiden 1977, pp. 129-131.

- ↑ Bruce C. Barker-Benfield: The manuscripts of Macrobius' Commentary on the Somnium Scipionis , Oxford 1975, p. 7 f .; Mireille Armisen-Marchetti (Ed.): Macrobe: Commentaire au Songe de Scipion , Vol. 1, Paris 2003, pp. XI f.

- ^ Pedro Pablo Fuentes González: Macrobius . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Vol. 4, Paris 2005, pp. 227–242, here: 231; Mireille Armisen-Marchetti (Ed.): Macrobe: Commentaire au Songe de Scipion , Vol. 1, Paris 2003, p. XIII.

- ↑ Jacques Flamant: Macrobe et le neo-platonisme latin, à la fin du IV e siècle , Leiden 1977, pp. 98-102, 122.

- ↑ On this and on the controversial question of the nickname see Mireille Armisen-Marchetti (ed.): Macrobe: Commentaire au Songe de Scipion , Vol. 1, Paris 2003, pp. VIII – X, XII – XIV and Alan Cameron: The Last Pagans of Rome , Oxford 2011, pp. 231-239. Cameron endorses the identity hypothesis.

- ^ Alan Cameron: Macrobius, Avienus, and Avianus . In: The Classical Quarterly , New Series 17, 1967, pp. 385-399, here: 386-389.

- ↑ On the dating see Paolo De Paolis (ed.): Macrobii Theodosii De verborum Graeci et Latini differentiis vel societatibus excerpta , Urbino 1990, p. XV f.

- ↑ Mireille Armisen-Marchetti (Ed.): Macrobe: Commentaire au Songe de Scipion , Vol. 1, Paris 2003, pp. XVI f .; Pedro Pablo Fuentes González: Macrobius . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Vol. 4, Paris 2005, pp. 227–242, here: 233; Alan Cameron: The Last Pagans of Rome , Oxford 2011, p. 238.

- ↑ On the genre of literature, see Jacques Flamant: La technique du banquet dans les Saturnales de Macrobe . In: Revue des Études latines 46, 1968, pp. 303-319.

- ↑ On the role of Servius in the Saturnalia and on his relationship to Macrobius see Nino Marinone: Per la cronologia di Servio . In: Atti della Accademia delle Scienze di Torino. Classe di Scienze Morali, Storiche e Filologiche 104, 1970, pp. 181-211 and Robert Kaster: Macrobius and Servius: Verecundia and the Grammarian's Function . In: Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 84, 1980, pp. 219-262.

- ↑ On the manners and the social hierarchy in the Saturnalia see the detailed study by Robert Kaster: Macrobius and Servius: Verecundia and the Grammarian's Function . In: Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 84, 1980, pp. 219-262.

- ^ For details see Richard Bernabei: The Treatment of Sources in Macrobius' Saturnalia, and the Influence of the Saturnalia during the Middle Ages (Dissertation), Ithaca (New York) 1970, pp. 12-99.

- ↑ See Marta Cristiani: Sogni privati e sogni pubblici: Macrobio e il platonismo politico . In: Studi storici 27, 1986, pp. 685-699, here: 685-688.

- ^ Heinrich Dörrie , Matthias Baltes : The Platonism in the Antike , Vol. 6.2, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 2002, pp. 20–32 (and commentary, pp. 172–202). See Meine Adriaan Elferink: La descente de l'âme d'après Macrobe , Leiden 1968; Herman de Ley: Macrobius and Numenius , Bruxelles 1972.

- ↑ Helmut Seng : Soul and Cosmos with Macrobius . In: Barbara Feichtinger u. a. (Ed.): Body and soul. Aspects of late antique anthropology , Munich 2006, pp. 115–141.

- ↑ Macrobius, Commentarii in somnium Scipionis 2,12,5 f.

- ↑ Macrobius, Commentarii in somnium Scipionis 2,15,2.

- ↑ See also Clemens Zintzen : Roman and Neo-Platonic in Macrobius . In: Peter Steinmetz (Ed.): Politeia and Res publica , Wiesbaden 1969, pp. 357–376. Zintzen believes that Macrobius considered a secluded life devoted to philosophical contemplation and political practice to be two equally legitimate paths to happiness. See, however, the limiting remarks by Mario Regali: La quadripartizione delle virtù nei Commentarii di Macrobio . In: Atene e Roma 25, 1980, pp. 166-172 and Jacques Flamant: Macrobe et le neo-platonisme latin, à la fin du IV e siècle , Leiden 1977, pp. 608-615.

- ↑ Jacques Flamant: Éléments gnostiques dans l'œuvre de Macrobe . In: Roelof van den Broek, Maarten J. Vermaseren (ed.): Studies in Gnosticism and Hellenistic Religions , Leiden 1981, pp. 131–142, here: 137–139 assumes influence from the ideas of Numenios.

- ^ Macrobius, Commentarii in somnium Scipionis 1,19.

- ^ Heinrich Dörrie, Matthias Baltes: The Platonism in the Antike , Vol. 5, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1998, pp. 158–161 (and commentary, pp. 490–494).

- ^ Alan Cameron: The Date and Identity of Macrobius . In: The Journal of Roman Studies 56, 1966, pp. 25–38, here: 27 f.

- ↑ Boethius, In isagogen Porphyrii commenta 1,11.

- ↑ On the importance of Macrobius reception for early medieval music theory see Michel Huglo: La réception de Calcidius et des Commentarii de Macrobe à l'époque carolingienne . In: Scriptorium 44, 1990, pp. 3–20, here: 14–16 and Christian Meyer: La théorie des symphoniae selon Macrobe et sa diffusion . In: Scriptorium 53, 1999, pp. 82-107.

- ↑ On Dungal and his independent stance towards the authority of Macrobius, see Bruce S. Eastwood: The astronomy of Macrobius in Carolingian Europe: Dungal's letter of 811 to Charles the Great . In: Early Medieval Europe 3, 1994, pp. 117-134.

- ^ Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France , Lat. 6370.

- ^ Alison M. Peden: Music in medieval commentaries on Macrobius . In: Frank Hentschel (Ed.): Music - and the history of philosophy and natural sciences in the Middle Ages , Leiden 1998, pp. 151–161, here: 154.

- ↑ See Edouard Jeauneau: Macrobe, source du platonisme chartrain . In: Studi medievali series terza 1, 1960, pp. 3–24; Clemens Zintzen: Comments on the aftermath of Macrobius in the Middle Ages and Renaissance . In: Michael Wissemann (Ed.): Roma renascens. Contributions to late antiquity and reception history , Frankfurt a. M. 1988, pp. 415-439, here: 417-421; Albrecht Hüttig: Macrobius in the Middle Ages , Frankfurt am Main 1990, pp. 94–119.

- ^ Albrecht Hüttig: Macrobius in the Middle Ages , Frankfurt am Main 1990, p. 29.

- ^ Alison M. Peden: Macrobius and Mediaeval Dream Literature . In: Medium Aevum 54, 1985, pp. 59-73.

- ↑ See the very detailed investigation in the dissertation by Alison M. White: Glosses composed before the twelfth century in manuscripts of Macrobius' Commentary on Cicero's Somnium Scipionis , Oxford 1981 (with critical edition of glosses) and Irene Caiazzo (ed.): Lectures médiévales de Macrobe. Les Glosae Colonienses super Macrobium , Paris 2002 (critical edition of the Cologne glosses from the early 12th century with a detailed introduction).

- ↑ Critical edited by Irene Caiazzo: Le glosse a Macrobio del codice Vaticano lat 3874. Un testimone delle formae nativae nel secolo XII . In: Archives d'Histoire Doctrinale et Littéraire du Moyen Age 64, 1997, pp. 213-234.

- ^ Irene Caiazzo: Note sur des Accessus ad Macrobium . In: Studi filosofici 18, 1995, pp. 7-22 (edition of four accessus to Macrobius and his Cicero commentary).

- ↑ For details see Albrecht Hüttig: Macrobius im Mittelalter , Frankfurt am Main 1990, pp. 147–166.

- ↑ For the translation of the Planudes see Manolis Papathomopoulos : La traduction planudéenne des Commentarii de Macrobe . In: Ciceroniana 11, 2000, pp. 133-140; Nóra Fodor: The translations of Latin authors by M. Planudes , dissertation Heidelberg 2004, online (PDF), pp. 187–197.

- ^ Richard Bernabei: The Treatment of Sources in Macrobius' Saturnalia, and the Influence of the Saturnalia during the Middle Ages , Ithaca (New York) 1970, pp. 135-144.

- ^ Richard Bernabei: The Treatment of Sources in Macrobius' Saturnalia, and the Influence of the Saturnalia during the Middle Ages , Ithaca (New York) 1970, pp. 162-192; Douglas Kelly: The Conspiracy of Allusion. Description, Rewriting, and Authorship from Macrobius to Medieval Romance , Leiden 1999, pp. 13-35.

- ↑ See Paolo De Paolis (Ed.): Macrobii Theodosii De verborum Graeci et Latini differentiis vel societatibus excerpta , Urbino 1990, pp. XLI-XLIX.

- ↑ On Petrarch's and Salutati's Macrobius reception see Clemens Zintzen: Comments on the aftermath of Macrobius in the Middle Ages and Renaissance . In: Michael Wissemann (Ed.): Roma renascens , Frankfurt a. M. 1988, pp. 415-439, here: 421-428.

- ↑ Michael D. Mc Gaha: The Influence of Macrobius on Cervantes . In: Revue de littérature comparée 53, 1979, pp. 462-469.

- ↑ Paolo De Paolis: Les Saturnales de Macrobe et l'idéalisation du saeculum Praetextati . In: Les Études Classiques 55, 1987, pp. 291-300.

- ↑ For example by Sebastiano Timpanaro in: Gnomon . Vol. 36, 1964, pp. 784-792.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Macrobius, Ambrosius Theodosius |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | late antique Roman philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | at 385 |

| DATE OF DEATH | after 430 |