cosmogony

Cosmogony ( Greek κοσμογονία Kosmogonia "world procreation"; in older texts also cosmogony ) referred explanations for the origin and development of the world. They can interpret the origin of the world mythically or explain it rationally . Cosmogonic ideas belong to the realm of mythology , cosmogonic theories are the subject of philosophy or the natural sciences .

The terms cosmogony and cosmology cannot be clearly distinguished from one another and are used in scientific as well as in philosophical and mythical contexts. “Cosmology” is primarily understood to mean natural science, which deals with the methods of physics and astronomy with the origin and today's structure of the universe, with cosmogony as a sub-discipline specifically dealing with the creation and development of the universe.

Cosmogonic myths have the comprehensive claim to make the origin of the world imaginable in a meaningful way and to establish the basic order for the human habitat. Where myths are part of cultural identity, they can be as persuasive as science.

The philosophical cosmology of the Greek pre-Socratics began speculatively and derived from older mythological ideas. At the beginning of the modern era , René Descartes first described a model of the origins of the world based on rationalist metaphysics .

This article is mostly about mythology. Religious myths about the origin of the world are also dealt with in the article Creation .

Distinction

The starting point is the same: the creation of the world lies far in the past, far from a possibility of observation and cannot be repeated in experiments. The big bang theory is generally accepted in science, but cannot be directly checked. Only the predictions resulting from it can be checked. If the theory can explain other phenomena, it makes sense. If new knowledge emerges, the theory is adjusted or refuted.

An elementary part of the religious myths in every culture are myths of origin, in the center of which the cosmogonic myth enjoys a special reputation as a model for all myths of origin. The task of myth is to give meaning to the world by relating elements of experience to one another. The myth refers to an unconditional level of reality (truth). It differs from scientific theory in that myth is not primarily aimed at understanding, but - as a religious virtue - submission.

Cosmogony as science

Natural laws established by science itself form the limits of knowledge. The Planck scale defines a lower limit for physical quantities and rules out any consideration beyond it. Nevertheless, explanations offered by science about the origin of the universe become paradoxical or speculation . The question of why cannot be considered from the outset, since natural sciences were separated from the field of philosophy as an independent discipline in the 17th century. Philosophical statements should now serve as a framework, in case of doubt, an influence of God could be considered for why questions (English: God of the gaps - “God as a stopgap”).

Ancient natural philosophy

Cosmogony as a science began when in ancient Greece the myth of the concept of reason Logos opposed and the attempt to explain the world, was asked about the goal to create meaning; to recognize that no longer acting gods or heroes, but elements or atoms were used to explain natural phenomena. It was about connecting everything with everything, starting with the first basic material and looking at the world as a system.

This is the task of natural philosophy , whose speculative beginnings lie with the pre-Socratics (about 610-547 BC). Anaximander deserves special mention , who in the search for the origin was the first to introduce not a primordial substance ( Arché ) such as water or air, but the “unlimited” ( Apeiron ) into a physical cosmogony free of mythology for the first time.

In his Timaeus cosmology, Plato (427–347 BC) represents a systematic order of nature in which a creator god ( Demiurge ) with a similar division of tasks as with Descartes, reasonably and systematically constructs a beautiful world. The mythological elements also have an explanatory function in Plato's model.

The cosmological theory of Aristotle (384–322 BC) takes over the basic orientation from the Greek mathematician Eudoxos : a spatially finite, but temporally infinite world, and spheres that spread out in layers over the earth in the center. The first cosmic unmoved person begins to move outside the spheres, the movement continues inwards, until here too the whole cosmos is driven by a divine force which is contained in all nature. Aristotle equates this god with logos, reason. For him the forces ( Dynameis ) in the world were still of a purely psychic nature and rooted in myth.

Descartes

René Descartes (1596–1650) made philosophy as a method of knowledge the basis of thought. Knowledge should only be gained through deduction . With this he took a first step towards the development of a natural science based on subjective certainty by introducing rational methods of knowledge independently and at a diplomatic distance from the idea of the divine. One of the first scientific cosmogonies is contained in his 1644 work Principia philosophiae ("The principles of philosophy"). Aristotle was one of the forerunners , followed by the cosmological theory of Kant .

Descartes tried to explain gravity using mechanistic models . The turbulence of matter clouds caused by centrifugal forces, whereby the particles trapped therein should only exchange their energy in direct contact, explained the movements of the planets and also the origin of the world system. In contrast to the Christian view, Descartes took people out of focus and at the same time declared the earth to be immobile by means of linguistic twisting. A relationship to the church between consideration and protest was typical of the 17th century; the latter ended up at the stake for Giordano Bruno , who, like Descartes, had committed himself to the Copernican view of the world .

As an explanation of the origin, Descartes allows God to create a dense packing of vortices of matter. The auxiliary construction God as the original drive provided the kinetic energy that is still present today.

Kant

Natural philosophical considerations range from Aristotle to Descartes to Immanuel Kant (1724–1804). In his General Natural History and Theory of Heaven (1755), he set up a cosmological theory in which he wanted to bring logos (theory) and myth (history) together. Descartes scientifically formulated cosmology still needed a god as a causal drive, Kant tried to grasp the order of nature from the history of nature. Kant's theory is philosophically significant because for the first time without God the planetary system emerges from a cloud of dust, formed solely by the forces of attraction and repulsion, until the finished state is reached.

Kant later drafted a restrictive criticism, stating that his cosmological theory would inadmissibly draw conceptual conclusions from experience to the general. Applied to today's big bang theory, which draws conclusions about the origin of the world from observable facts such as cosmic background radiation , Kant's criticism could stimulate philosophical reflection.

In 1796, Pierre-Simon Laplace published his so-called nebular hypothesis on the origin of the solar system independently of Kant . Because of the similarity with the Kantian theory, both cosmogonies were also known as the Kant-Laplace theory .

For the current scientific discussion, see

Cosmogonic myth

Even Isaac Newton (1643-1727) differed valid between universal laws of nature and cosmogonic Urgründen to which it, but could give no explanations stories. Behind the laws of nature Newton saw a continued activity of God ( creatio continua ). An outside god had to regularly give the world a nudge and intervene with comets to balance the changing gravitational force between the planets. The action of the divine power on the world corresponds to a watchmaker who has to constantly readjust his product so that it works properly. Otherwise humanity would perish.

The Anglican Archbishop James Ussher (1581–1656) had in his Ussher Chronology published in 1650 the origin of the world on October 22, 4004 BC. At 6 o'clock in the afternoon. Other contemporary authors came to similar conclusions. Newton's posthumously published writings include The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended . In it he set up a chronology of world history and protected the dating of Ussher from critics, which had previously received the blessing of the Church of England . From the biblical Revelation of John and the Book of Daniel , Newton calculated in an apocalyptic script ( Observations upon the Prophecies of Daniel, and the Apocalypse of St. John ) the end of the world, which is supposed to take place in the year 2060.

Myths are true: this claim distinguishes them from fairy tales and other forms of fantasy tales . From the myths about the origin of the world, the development of things, of humans and animals, the history of the origin of one's own society emerges in context. In the beginning there was always an undivided whole, a primal material or a primal being, in the simplest case an egg that breaks and divides into heaven and earth. After this original state, the world is no longer perfect, but that which divides results in something ordered.

Now the time of the ancestors follows. Their origin myths tell of a prehistoric age separated from their own time and from powers that work from outside their own world. Hence the special respect enjoyed by the “sacred stories” from the “paradisiacal age”. There are also myths of a periodically recurring creation from the original state (the "dream time"), which justify that society can continue to live anew. The cosmogony of the world is repeated at the Incarnation. The heroes, who wandered the earth in prehistoric times, taught people all cultural techniques, including social and religious rituals. These ancestors from Paradise did not completely withdraw, but occasionally still exert influence from outside. In some ritual orgies, social bans have been lifted for a short time; through the principle of repetition, they remind us of the happy world of the ancestors. This core is still in the Shrovetide, which is celebrated at the winter solstice.

The result of a world creation myth is not a cosmos in the purely scientific understanding, but a world in which the essential social and cultural institutions are already anchored and the introduction of which is often the focus of the mythical narrative. The institutions of a culture traced back to the mythical origin include sacrifice, cult festivals, social hierarchy, agriculture and cattle breeding.

Greek myths

According to the Greek model, a myth is mostly understood as a poetry. Although Greek poetry has been thoroughly described and analyzed, there is still a lack of knowledge of living myth as a religious and cultic practice. This makes it difficult to correctly assess the underlying standards of value.

According to a story by Orpheus , the night began with Nyx , a bird with black wings. From its egg, fertilized by the wind, the god of love Eros rises with golden wings. The egg was still in chaos (initial meaning: "empty space"), surrounded by night and darkness, the Erebos . The story has variants: in the egg lay Okeanos , a river god and Homer origin of the gods, and the goddess Thetys . 3000 sons, the rivers, and just as many daughters descend from these primordial gods. With Hesiod there are later 40 daughters, including Aphrodite , the goddess of love, who is also considered the daughter of Kronos or eldest Moira . The ramifications are innumerable, there are also other origins.

First there was the chaos. According to the story of Hesiod, the earth mother Gaia came into being , who gave birth to Uranus , the sky above her, Pontus , the sea and Eros . Heaven and earth produced giants, three one-eyed Cyclops and a dozen titans , the youngest of whom was Kronos , whose sister and wife, the titan Rhea , gave birth to Zeus , father of the gods .

A son of the titan Iapetus is the giant Atlas . In the Hesperides in the far west, after the separation of heaven and earth, he carries the celestial dome on his shoulders.

Mesopotamia

The Sumerian tradition, the prologue of the argument between heaven and reed, reports how the sky god Anu mates on the earth, which after the act gives birth to the plants. The Babylonian image of the cosmic egg as the original whole is based on older Sumerian mythologies. In a primordial ocean there is an egg and divides, alternatively there is a sea monster; or heaven and earth separate from a totality. Transferring it to the gender category means that the ideal of perfection lies in androgyny or gender distinction.

A typical example for the division of an ancient being and one of the cosmogonic traditions comes from Babylonia. It is in the extensive poetry Enûma elîsch from around the 13th century BC. Received. During the primeval chaos, at times when “heaven and earth had no names” and the primeval waters were still mixed with one another, the god Marduk divided the world-creating, female dragon Tiamat in a generational struggle . The demiurge won against the forces of chaos. The division created earth and sky. Marduk corresponds to the sun, which with its rays drives away the clouds of the sea personalized by Tiamat. The periodic renewal of nature in the seasons has already been introduced here.

Later, in the creation of the human race, this mythological model is repeated, in which a god must be sacrificed in order for a new world to arise. Until it comes to Marduk's act in the drama, the plot carries out complicated extensions. In the end he succeeds in bringing the chaos, stirred up by hordes of monsters, to perfect order.

Bible

In the Babylonian cosmogony the underworld and the human world from the duality of the sexes arise while in the Creation story of the Old Testament the world out of nothing and closed a fact the Creator God is evident.

Indo-Iranian mythology

A complete structure of the cosmos is already described in the Gathas , the oldest hymn texts of the Iranian Avesta . At the beginning two powers face each other: the right world order ( Asha ) and the evil par excellence. Both are aspects of the wind god Vayu, also known in the Indian Vedas . He embodies the world axis in the center of heaven and earth. Behind the cosmogony there is a driving principle, which in the microcosmic area corresponds to the human breath soul . Macrocosmically, the world is understood as the body of the deity or as a primeval cosmic man who was born from a deity. In Middle Persian literature, especially in the Bundahishn , the pregnancy of the Creator God is described in detail. When primitive man is born after 3000 years, the world emerges with him from the godhead. A part of the visible world arises from every part of the body of prehistoric man. The head becomes heaven, the feet become earth, from his tears the water is formed, from his hair the plants, from his understanding the fire. In the symbolism of the microcosm and macrocosm , the individual person embodies the world on a small scale and the entire world is just one giant person. This idea pervades Indian philosophical thought; recognizing it is part of the theoretical path to salvation in Indian religions.

In India the primordial human being, through whose self-sacrifice the world arises, is called Purusha . His creation myth is described in the Purusha sukta , which is contained in the Rigveda . The creator says: The fire comes from my mouth, the earth from my feet, the sun and moon are my eyes, the sky is my head, the regions of heaven are my ears, water is my sweat, the space with the four regions of the world is my body and the wind is my sense ( manas ), as it is called in the Mahabharata (III, 12965ff). In Iranian mythology , the idea of this prehistoric man may still live on in Yima and Gayomarth .

The threefold is essential; Thus the ancient Iranian prehistoric man spends 3000 years as a fetus in the belly of the god, he lives 30 years as a human being and his size is three nāy . When the earth exists, it will soon be too small, so Yima takes three steps to ensure that it is expanded. In the ancient Indian conception, the body of the creator deity is made up of the six elements ether, wind, fire, water, earth and plants. In Zoroastrianism, these correspond to the elements fire, metal, earth, water and plants. In Iran, ether has been exchanged for metal and the sixth element, wind, was probably originally counted among the local gods. In Indian and Iranian mythology, the body of the primordial being consists of these elements, which together form the cosmos. In Zoroastrianism Ahura Mazda is the creator god, in Manichaeism the primitive man is called Ohrmizd. Both face the evil embodied in Ahriman .

The surrounding universe is thought to be spherical or egg-shaped, primitive man is as wide as it is long. The Mandaean text collection Genza is about the ascension of the soul to its eternal home after the death of man. The 26th tract says about the creation of the world. Accordingly, the earth is an area of land washed by the sea on three sides, which sinks to the south and piles up to high mountains in the north, where the surrounding sea is missing. From there the life-giving water flows down.

China

Creation myths and history were woven together in China. The biographies of the early rulers begin with the tales of mythological heroes and were processed literarily with the aim of being able to serve as a justification for the concept of the state. Popular Chinese myths of the origins of the world were developed into abstract theories and are mostly handed down in such a form that the processes appear to have been planned by wise authors. What is presented in its entirety as Chinese mythology are fragments of surviving folk tales that arose in different times and regions. The older myths are more informal. The myths unfolded in the Chinese religion, which has its origin in ancestor worship .

In Shan-hai ching ("Book of Mountains and Seas", written 3rd century BC to 1st century AD), one of the oldest mythical-geographical descriptions and at the same time a source for historians, there is on a mountain a yellow or red bird with six feet and four wings that has no face but can dance. This is how chaos is represented; the bird can also be the mythical yellow emperor Huangdi , who ruled in the middle of the empire and rose to become the supreme Daoist god.

The myths about the giant Pangu belong to the simplest and therefore oldest forms of cosmogonic myths. He was born as a dwarf from primeval times, i.e. chaos, which after 18,000 years broke down into its heavy and light components. The lower half became the earth ( yin ), the upper half became the sky (yang). Just as Pangu slowly grew into a giant - he grew 10 feet every day, thereby compacting the earth 10 feet each day and lifting the sky accordingly - he pushed the eggshells further and further apart until he finally broke apart himself. There are long and varied lists of what became of his body parts: his eyes became sun and moon, his head became the four sacred mountains, his fat or blood became oceans and rivers, his hair became grass and trees, his breath wind became rain, sweat turned into thunder, and the fleas on his skin eventually became (according to a late myth) man's ancestors.

Part of the Asian and African myths is that the separation of heaven and earth must be made irreversible by cutting the rope that connects them . The fact that the world can only come into being with the death of Pangu explains a continuation of the myth that Pangu describes as trapped between the two after the separation of heaven and earth, i.e. he, like the cosmic rope, formed a connection that had to be severed before the World can endure.

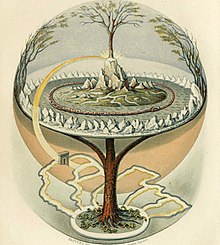

From the idea of Pangu standing upright and keeping heaven and earth away from each other, the structural model of the world developed with a curved, round and rotating sky supported by four pillars that rest on the square and immobile earth. In some myths, the earth is held from below by eight pillars. The sky is layered in nine superimposed areas, separated by gates guarded by tigers and panthers. At the edge of the world nothing expands.

This orderly world looks similar to a ladder cart covered with a canopy. The earth becomes the floor of the wagon, the person in this ceremonial wagon moves over the earth and resembles the sun, which moves its way in the sky in a solar wagon. Rathas , the Indian temple chariots , were likewise deified . Of the four pillars acquired a special meaning. The Pou-chou column in the north-west of the world was shaken by the wind-bringing demon Gong Gong (Kung Kung) during an attack . As a result, a deluge broke out . The second phase of creation began again with creating order after the primal chaos had been repeated with the flood. The goddess with the snake body Nüwa had to put the flooded and collapsed world back into order. She dammed the tide with reeds, and she set up the four pillars supporting the sky on the four feet that she had cut off from the turtle. The creation of living beings followed. The first humans were formed from yellow clay by Nüwa. The work was exhausting and took too long for her, so she only dipped a rope into the mud for a moment and then made other people out of it. People who came into being in two ways are the rich and the poor.

Dayak

The Babylonian dragon Tiamat and the sea monster known in the rest of Asia, Europe and parts of Africa are introduced by similar origin myths. The sun god and the pre-worldly dragon of the underworld form the contrast and the starting point for a duel. In the myths, a bird (like sun) fights a snake (also dragon, like water). The pair of opposites offers the opportunity to imagine the primordial perfection to be striven for in the union as a mythical bird-snake-being. The bird is the first to fight the old world, thereby creating the basic structures for the new one. This creation myth is the model for stories in which a hero from abroad defeats the long-established dragon so that a new peace may come to the land.

The religion and death ceremony of the Ngaju - Dayak in Kalimantan have been thoroughly investigated, as of exemplary importance . It's a living myth. The primordial wholeness was in the mouth of the coiled water snake. The world gradually emerged from the collision of two mountains.

The two mountains are gods and also the seat of the personalized male god Mathala and the goddess Putir , who create heaven and the underworld. After the creation of the world, the creation of human space takes place through two hornbills, which are now in their third form equal to the two gods. The two birds fight violently in the crown of the tree of life. The Dayak ancestors emerge from parts of the tree that was torn during battle. In the end, both birds are dead and the tree is also destroyed.

Life arises from a polarity and thereby destroys the primordial unity. In the rites of passage , the primeval battle of two powers is imitated and the lost wholeness is briefly restored. The house becomes a model of the universe. It rests on the water snake, the roof becomes the mountain of the gods.

A popular mythical image is the tree of life as a cosmic axis in the center of the world. In the tradition of an Australian people, a holy stake was driven on treks to turn the new campground into an organized world. Loss of the stake would necessarily have been associated with destruction in the chaos.

At the wedding ceremony, the Dayak couple cling to the tree of life and set out on a journey into the otherworldly world on paths that have to be found precisely. The creation of the first human couple from the tree of life is repeated during the ceremony. Elaborate burial rituals with a coffin as a soul ship must ensure that the deceased can return to the wholeness of the origin. The transition to the divine realm makes the dead worthy of worship in the ancestral cult .

Finno-Ugric peoples

The creation myths of the Finno-Ugric peoples differ in their design and have not developed a common concept. The Estonian creation myth alone was recorded in 150 variations. Nevertheless, symbolic images known from other parts of the world (and mentioned above) in Eastern Europe and North Asia are at the center of the mythological order: the cosmic egg, the world tree, pillars supporting heaven, and the separation of heaven and earth. In the Finno-Ugric myths, the creation of the earth seems to be present everywhere, otherwise a female eagle would not be the first to fly over the water in search of a dry place to lay its eggs. Only the sleeping wizard Väinämöinen's knee protruded from the water. The bird took the knee of the main character from the Finnish national epic Kalevala for land, laid its eggs on it and began to breed. When Väinämöinen woke up from an itch in his knee, the half-hatched egg fell into the water and broke. The egg yolk became the sun and moon, the solid shell became earth and stars. The hallmark of the Finno-Ugric peoples was their belief in the power of sorcerers . For shamanism , which used to be widespread , the eagle was considered the father of the first shaman and the flight of birds imitated in the ritual as a journey to the otherworldly origin.

In the first Väinämöinen song of the Kalevala, the world emerged from the egg of a duck that brooded on the knee of the water mother, who had previously been the air goddess Ilmatar , protruding above the primordial sea . Several eggs fell from the nest, from which earth, sky, stars and clouds emerged. Väinämöinen was only now born to the water mother's son and acquired magical powers; how he applied them is described from the second song onwards. One of the seven eggs was made of iron, which formed a dark storm cloud. The shortest Estonian creation myth sums up: The sun bird built a nest in the field and laid three eggs in it. One became the underworld, the second the sun in the sky, and the third made the moon. The origin of these Estonian myths is believed to be in the 1st millennium BC. Assumed. At that time they were put into a meter ( Estonian : regilaul ) and are still a national treasure today. Rock carvings in the region, which show birds laying eggs, are interpreted as mythological images and date back to the 3rd millennium BC. Dated.

- The structure of the world describes: Finnish mythology .

Among the Samoyeds , who were originally reindeer nomads in northern Russia , a searching bird also flew over the water. The supreme god Num sent several birds one after the other until one brought some earth from the sea floor in its beak. From this, Num formed an island floating on the water, which ultimately became solid earth. The creation seems to have taken place in stages, because in numerous myths a hero appears whose task it was to "free" the sun and moon in dangerous undertakings and to bring them to their position so that it could get light. The hero had to fight ghosts and a monster by magical means. From a stone that he threw at her, a huge mountain was formed. This explains the origins of the Urals .

A differently imagined deity ( a woman among the Finns , a malicious giant among the Samoyed ) determined the fate of mankind with a magic instrument. The device called in the Kalevala Sampo had to be obtained in heroic battles that had different outcomes. Sampo is also the name of the column that supports the Finnish universe. The idea that the sky is supported by pillars was widespread throughout the region. Places of worship were located on hills, the tree of life erected there could have been understood as a symbol of the pillar supporting the sky. The world tree connects the lower, middle and upper world. Its top reaches the north star , around which the sky rotates. It is fitting that seeds revered individual stones as pillars of the world. Myths also describe how these pillars came into being. In primeval cosmic times the sky was only as high as the roof of the tent or hut. Again, the separation of heaven and earth had to be brought about as the most important principle of order and crossing between the two areas had to be prevented. Since then this has only been possible for shamans in a trance . In one story, a woman complained about too much smoke or fog in the hut, the heavenly beings got angry about this and sent a giant to raise the sky to its present height. Stones set up that are considered sacred are microcosmic repetitions of the world model. The same was true of numerous Finno-Ugric peoples for the central post of the house or tent, with a stovepipe in the tents ( Tschum ) of the Samoyed instead of the revered central post in winter.

North Germanic

There is a comprehensive conception of the traditional Germanic myths , but this was written down by Christian historians from the 13th century, 200 years after the introduction of Christianity in Scandinavia . From the previous time, when the myths of the various Germanic peoples were still alive, apart from a few short runic texts, there are no written sources of their own. The most important tradition is the Snorra Edda , a manuscript from 1270, which brings together mythological texts from the 10th to 12th centuries and arranges them thematically. The myths passed down orally in pre-Christian times are thus only available from memory and in at least two refractions. The editor Snorri Sturluson weighted the world of gods and related it to the dominating god father Odin , one of the 12 Assir ruling the world . The most important theme in several Edda poems is cosmogony. The world tree also finds its counterpart here, as does the flood and the dismemberment of the primordial giant, from whose body parts the world arises (as in many high Asian cultures and - as an exception - with the Dogon in Africa ).

With peoples who once immigrated from flat Siberia, their idea of the earth as a disk ( Midgard ) is understandable. The disc is held by the world ash Yggdrasil . From the 6th century until the Middle Ages, this spatial concept competed with the concept of a curved earth, which originated in Greek antiquity and penetrated into the Germanic culture. Language comparisons show that both ideas were common at the same time. The Greek term for "ball, ball" is sphaira, Latin spera (hence "sphere") and was translated in Old High German as schibelecht, ie the term field of "disk", however, Notker III described. At the beginning of the 11th century, in his translations of ancient Latin texts, he presented the worldview of a curved earth, although he considered it unclear whether the lower half would also be inhabited by humans.

The oldest prehistoric giant was (in the Völuspá ) Ymir : It was prehistoric | Since Ymir lived. | There was neither sand nor lake, | Still salty wave, | Only yawning abyss | And grass nowhere. (in Karl Simrock's translation). Ymir was created by mixing two elements. Ice water from the cold northern world of Niflheim combined with rays of fire from the hot south, where the giant Muspell rules. The two opposite places existed before the world actually came into being. The Élivágar rivers originated in the center of Niflheim and filled the previously empty Ginnungagap gorge with ice. From the other side hot air streamed and melted the ice from which the primeval giant was formed.

The giants, men and gods later descended from the body parts of Ymir. Next to Ymir, the original cow Audhumbla was created from melted ice , which gave him food and thus became a life giver and a symbol of fertility. Four streams of milk flowed from her udder; she fed herself on the salt contained in the ice blocks. It so happened that while licking the ice, a human being named Buri appeared. Buri gave birth to a son, Börr , from whose connection with the ice giant Bestla , who was descended from Ymir, the three gods Odin, Vili and Vé emerged . The sweat from Ymir's left armpit formed a man and a woman, the first generation of ice giants. They were older than the gods descended from Buri and constantly threatened their rule. The sons of Börs (elsewhere it is the three gods themselves) killed the giant Ymir. The world emerged from the parts of his body: the blood became the sea, his flesh the earth, the bones became mountains, the cranium became the sky, which had to be supported by four dwarfs. Through the painful act, the transition from the primeval world into the human world was accomplished, which could now be established. The stars formed from the sparks of the sun on the stretched vault of heaven, and the gods set the rhythm from night to day. This is followed by descriptions of how the apartment is furnished, how the palace of the gods is furnished, then the gods notice that no humans have yet been created.

Egypt

One of the Egyptian creation myths comes from Heliopolis . In the beginning there was no nothing, but a formless chaos existed as primeval water . The heliopolitanische cosmogony of secular creation understands Atum as the light God as sun during his first sunrise was the earthly life still in it. The divine two sexes, Shu , god of air, and Tefnut , goddess of fire , emerged from it through separation . In the belief of the ancient Egyptians, this world and the hereafter ( Duat ) were also the creation of Atum. But while Re was the sun of the day in Heliopolis , Atum was worshiped at sunset and at night as the evening manifestation of the universal sun god.

World mountain

In the time of the Egyptian myth of the primeval mountain originating from the sea, the idea of the same world mountain and an island that forms in the midst of chaos belongs to the Sumerians in Mesopotamia . There she was symbolized in the ziggurat , a wide, brick-built temple in the form of steps. Such a ziggurat, which was supposed to represent heaven and earth as a cosmic whole, was probably also the biblical tower of Babel .

In many regions of Asia there is the myth of the World Mountain, which is occasionally located geographically, as in the case of the holy mountain Kailash in Tibet. The starting point of the Asian mountain of the world lies in the mythological Indian mountain Meru , which found its architectural equivalent in the Hindu temple mountains or in the Buddhist stupas such as Borobudur in Indonesia. With the ascent of the holy mountain one approaches not only the center of the world, but also the starting point of creation. The steep steps to the top lead over high terraces to different floors of the sky. The stepped base of a temple, above which the “pure area” begins, has an equally important symbolic value. Temples that were primarily intended for the worship of the ruler, such as the northern Afghan fire temple Surkh Kotal , also followed this step-by-step plan.

Africa

The creation of the world is not a central theme in African mythology. There has always been an unformed primeval world. Even the sky gods known in most societies have moved into the distance over time and have made room for the actual actors: the direct descendants of these high gods, who are engaged in the creation of man on their behalf. Earth gods and other lower deities practice simpler creations in which people emerge from trees or crevices. More details on the enormous range of African world order and explanations in the

.

Indian ages and repetition

The Code of Manu starts before the social rules of behavior for the four life stages of man are set forth in the description of creation. In the beginning the world was a dormant, undifferentiated darkness from which a self-creating elemental force emerged. First, this created the water and from the seed that fell into the water, a golden egg was created. This power gave birth to itself as the creator god Brahma from the egg . After living in this egg for a year without doing anything, he divided it into two halves with his willpower, creating heaven, earth and in the middle air, the eight regions of the world, the ocean and the people who were already in the four boxes were divided. The two most important structures for people are thus given: the geographic location in the world and the hierarchical integration into society.

The original principle is unity without duality. Vishnu lies immobile on the world serpent Ananta-Shesha at the bottom of the ocean and guards creation. How Vishnu becomes a turtle at the bottom of the ocean, as the basis for the axis of the world, the mountain Mandara , which is set in circular motion and gives rise to the other things and beings of creation

This is followed by the creation of man, which is described as a transition from the original state in one of the oldest cosmogonic myths in the Rigveda . The gods sacrificed the primitive man Purusha - which simply means "man", who with his thousand heads and thousand legs was so big that he encompassed the whole earth. One imagines the world snake to be similarly huge. The myth of both found its way into the Nordic mythology of Scandinavia, the latter as a huge Midgard snake , the primeval giant can be found in the north as Ymir and as Gayomard in the Central Persian creation story Bundahishn the Zoroaster . The human world emerged from the sacrifice of prehistoric man: the animals, the moon, the sun from his eyes, the air from his navel, the sky from his head, the earth from his feet, and the four different ones arose to order for people Box . Through this sacrifice the gods could go to heaven.

Purusha was pressed upside down on the flat earth ( vastu ), following the orientation of the cosmic mandala to the center of the world. This Vastu-Purusha mandala is handed down in medieval architecture textbooks and is often drawn in a square nine-field plan, with Brahma and the navel center of the Vastu-Purusha being placed in the central field . According to the imagination, every building and especially every temple is built on it. The building process is seen as a repetitive creation.

Back to primeval times: The simple mound of earth as an early Indian memorial was transformed by Buddha into a symbol of enlightenment. The first Buddhist stupas were mounds of earth, later hemispherical stone marks and images of the sky. Because of their shape and as a symbol of the creative principle, they were compared with the Urei and also named as Anda ("egg"); Image of a doctrine of salvation, the goal of which lies beyond death and rebirth.

Indian creation is followed by doom in an endless cycle. The world cycle is divided into four world ages ( Yuga ). Today's world is Kaliyuga , the beginning of which was on February 18, 3102 BC. Is accepted. This precise information should give the statement a higher level of credibility.

Meaning and structure

For Karl Jaspers , by participating in the myth from creation to the end of the world and again a new beginning, "the world as the appearance of a transcendent history" is thought of, as a "temporary existence in the course of a transcendent event".

In the structure of the myth there are both rational and irrational elements, the myth also contains explanation, it is only a matter of finding out at which point.

See also

- Creatio ex nihilo

- Airavata , Indian creation story of the white elephant

- Areop-Enap , creation story of the Pacific island of Nauru

literature

- Andrea Keller: World catastrophes in early Chinese myths. Akademischer Verlag, Munich 1999 ISBN 3-932965-31-0

- Barbara C. Sproul: Primal Myths: Creating Myths around the World. Harper & Row Publishing, New York 1979

Web links

- Olaf Briese : origin myths, founding myths, genealogies. To the paradox of the origin. (PDF; 120 kB) In: Martin Fitzenreiter: Genealogy - fiction and reality of social identity. Golden House Publications, London 2005, pp. 11-20

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jan Rohls: Philosophy and Theology in Past and Present. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2002, p. 322, ISBN 978-3-16-147812-3

- ↑ Alvin Plantinga: God of the gaps? (Precisely what is it?). American Scientific Affiliation, 1997

- ↑ Uvo Hölscher: Anaximander and the beginnings of philosophy (II). In: Hermes, 81. Vol., H. 4. 1953, pp. 385-418

- ^ Fritz Mauthner : Dictionary of Philosophy. Leipzig 1923, pp. 288-295. Online at zeno.org

- ↑ Albrecht Beutel: Church History in the Age of Enlightenment: A Compendium. (UTB M, Volume 3180) Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2009, p. 48, ISBN 978-3-8252-3180-4

- ^ Ian G. Barbour: Science and Belief. Historical and contemporary aspects. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2006, p. 44, ISBN 978-3-525-56970-2

- ↑ Deviating: October 23, 4004 BC. At 9 a.m.: Donald Simanek: Bishop Ussher Dates the World: 4004 BC.

- ^ The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended by Sir Isaac Newton. Project Gutenberg

- ^ Tessa Morrison: Isaac Newton's Temple of Solomon and his Reconstruction of Sacred Architecture. Springer, Basel 2011, p. 17

- ^ Isaac Newton: Observations upon the Prophecies of Daniel, and the Apocalypse of St. John. Internet Archive

- ↑ The world will end in 2060, according to Newton. London Evening Standard, June 18, 2007

- ↑ Mircea Eliade : The longing for the origin. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt / Main 1976

- ↑ Karl Kerényi : The mythology of the Greeks. Volume 1: The Gods and Stories of Humanity. Munich 1966

- ^ Otto Strauss: Indian Philosophy. 1924. Reprint: Salzwasser, Paderborn 2011, p. 138f

- ↑ Rigveda 10,90,1-16 de sa

- ↑ Carsten Colpe: Old Iranian and Zoroastrian mythology. In: Hans Wilhelm Haussig , Carsten Colpe (ed.): Gods and myths of the Caucasian and Iranian peoples (= dictionary of mythology . Department 1: The ancient civilized peoples. Volume 4). Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-12-909840-2 , p. 465.

- ↑ Geo Widengren : The Religions of Iran. (The religions of mankind, Volume 14) Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1965, pp. 8-11

- ^ Wilhelm Brandt: The fate of the soul after death according to Mandaean and Parsonian ideas. In: Yearbooks of Protestant Theology. 18, 1892. Reprint: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1967, p. 23

- ↑ Achim Mittag : The burden of history. Notes on Chinese historical thinking. (PDF; 37 kB) ZiF: Mitteilungen 2, 1996

- ↑ Marcel Granet: The Chinese Thought. Content - form - character. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1980, pp. 259–266 (French original edition 1934)

- ^ Daniel L. Overmyer: Chinese Religions - The State of Field. (PDF; 5.0 MB) Part 1: The Early Religious Traditions: The Neolithic Period through the Han Dynasty (approx. 4000 BCE to 220 CE). In: The Journal of Asian Studies 54, No. 1 February 1995, p. 126 , archived from the original on November 4, 2012 ; accessed on February 11, 2017 (English).

- ↑ M. Soymie: The Mythology of the Chinese. In: Pierre Grimal (ed.): Myths of the peoples. Vol. 2 Frankfurt / Main 1967, pp. 261-292.

- ↑ Jani Sri Kuhnt-Saptodewo: A bridge to the upper world: sacred language of the Ngaju. (Research Notes). Borneo Research Bulletin, January 1, 1999

- ↑ Mircea Eliade: The longing for the origin. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt / Main 1976, pp. 111-115

- ↑ Mircea Eliade: Shamanism and archaic ecstasy technique. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt / Main 1980, p. 157f

- ^ Mari Sarv: Language and poetric meter in regilaul (runo song). Electronic Journal of Folklore 7, 1998, pp. 87-127. ceeol.com

- ↑ Ülo Valk: Ex Ovo Omnia: Where Does the Balto-Finnic Cosmogony Originate? The Etiology of an Etiology. (PDF; 182 kB) Oral Tradition, 15/1, 2000, pp. 145–158

- ↑ Aurélien Sauvageot: The mythology of the Finnish-Ugric peoples. In: Pierre Grimal (ed.): Myths of the peoples. Vol. 3 Frankfurt / Main 1967, pp. 140-159

- ↑ Kurt Schier: Religion of the Teutons. In: Johann Figl : Handbuch Religionswissenschaft. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, pp. 207–221

- ↑ Reinhard Krüger: Sivrit as a seafarer. Conjectures to the implicit spatial concept of the Nibelungenlied. (PDF; 83 kB) In: John Greenfield: Das Nibelungenlied. Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, Porto 2001, pp. 115-147

- ↑ Eduard Neumann, Helmut Voigt: Germanic mythology. In: Hans Wilhelm Haussig , Jonas Balys (Hrsg.): Gods and Myths in Old Europe (= Dictionary of Mythology . Department 1: The ancient civilized peoples. Volume 2). Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1973, ISBN 3-12-909820-8 , p. 62.

- ↑ Pierre Grappin: The mythology of the Germanic peoples. In: Pierre Grimal (ed.): Myths of the peoples. Vol. 3, Frankfurt / Main 1967, pp. 45-103

- ^ Friedrich Kauffmann: German Mythology . Bohmeier Verlag, Leipzig 2005, The world - beginning, end, new life., P. 130–137 ( online ( memento of February 22, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) [PDF; accessed on February 11, 2017]).

- ↑ According to Proverb 1248 Pyramid Texts Atum was the "self-originated"

- ↑ Earlier assumptions that Tefnut symbolized moisture have since been rejected in Egyptology , according to Jan Assmann: Death and Beyond in Ancient Egypt . Beck, Munich 2001, p. 30.

- ↑ Helmuth von Glasenapp : Indian Spiritual World. Volume 1: Faith and Wisdom of the Hindus. Hanau 1986. Manusmriti-Text pp. 142-149

- ↑ Rigveda 10.90 de sa

- ↑ Karl Kerényi: The anthropological statement of the myth. In: Hans-Georg Gadamer and Paul Vogler (eds.): Philosophical Anthropology. First part. Stuttgart 1975, pp. 316-339

- ^ Ernst Diez: Indian Art. Ullstein Art History, Vol. 19, Frankfurt 1964, pp. 31–38.

- ↑ JF Fleet: Kaliyuga Era of BC 3102. In: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. July 1911, pp. 675-698

- ↑ Karl Jaspers : Introduction to Philosophy. Munich 1971, p. 65

- ^ CI Gulian: Myth and Culture. On the history of the development of thought. Vienna 1971