Creation story (priestly scripture)

The story with which the Bible begins is referred to as the creation story of the priestly scriptures ( Genesis 1,1–2,3 (4a)). The expression creation account (instead of history ) is also common.

The " priestly script" was a written source that was combined by editors with "pre-priestly" (ie older) texts. The newer document hypothesis is in the meantime controversial or modified, but the majority of exegetes hold on to the above view.

The priestly scripture begins with the six-day work of creation ( Gen 1 EU ): separation of light and darkness, creation of the heavenly vault, separation of land and sea as well as plant growth on earth, creation of the heavenly bodies, creation of the animals of water and air, creation of the Land animals as well as human creation. The rest of God on the seventh day is the goal of the story ( Gen 2.1–3 EU ). This is followed directly by the Noach family tree ( Gen 5 EU ) and the flood story . The story of creation and the flood complement each other.

The Bible knows the ancient oriental idea of a creation through the victory of the divinity over a chaos power; but the priestly scripture does not adopt this idea: Without encountering any resistance, God ( Elohim ) creates a life-friendly earth in six days from a previous world in which no life was possible. He assigns the creatures to their habitat sky, sea or mainland, blesses them and instructs them to take over their habitat.

In German-speaking biblical studies, the idea of bringing the six-day work of Genesis 1 EU in line with modern scientific findings is of little interest. The story of creation in priestly writing certainly contains “science” according to the standards of its time of origin: the narrator took part in an East Mediterranean-Middle East cultural exchange that was inspired by Mesopotamia. Egyptian motifs are also included in the story.

Impulses from the creation story of the priestly scriptures are taken up in theological anthropology , with the focus on the dignity of men and women and their dealings with nature .

For the dating and the group of authors see the main article Priestly Scripture .

Jewish and Christian approaches to the text

In Judaism, Gen 1: 1–2: 3 is the first reading in the Bereshit week , so it has always been viewed as a unit of meaning. The Torah is a sacred text in the strict sense, that is, repetitions, omissions, the occurrence of the same root word and other peculiarities of the Hebrew text are carefully observed and asked for their meaning. This tradition of interpretation characterizes the translation of the Bible by Franz Rosenzweig and Martin Buber . The liberal rabbi Benno Jacob wrote a comprehensive commentary on Genesis (published 1934, reprint 2000), from which many individual observations on the text were taken up in the more recent Christian exegesis.

In Christianity, the first three chapters of Genesis were traditionally viewed as a unity: " Creation and Fall", an arc of tension that extends from the creation of the world through the creation of the prehistoric couple to the fall of man and the expulsion from paradise . The fact that the priestly story of creation crosses the chapter boundary is a visible indication to this day that the text was not recognized as a unit of meaning in the Christian Middle Ages. In Christianity, the exact Hebrew wording is of much less importance outside of the scientific field than in Judaism. The difference between a Christian and a Jewish translation can be seen by comparing the verse Gen 1, 2c:

- "And the Spirit of God floats on the water." ( Martin Luther : Biblia Deudsch 1545 )

- "Braus Gottes brooding all over the waters" (Martin Buber / Franz Rosenzweig: Die Schrift , first edition. In a letter to Buber in 1925, Rosenzweig expressed himself enthusiastically about the formulation found with it; nevertheless, the second edition changed "brooding" to "spreitend", and Buber finally decided on "swinging.")

Steps of historical-critical exegesis

Textual criticism

In view of the long path of transmission of the Hebrew Bible, the textual criticism first determines the best possible text. It is based on the Masoretic text of Genesis 1,1–2,4a. The relationship to the ancient translation into Greek ( Septuagint ), which offers an expanded text, needs to be clarified . The narrative of the works of creation follows a scheme . The Septuagint applies it more consistently. This explains most of the deviations from the Masoretic text. But both the Samaritan Pentateuch and the Qumran fragments relevant here , Targum Onkelos and the Peschitta, follow the scheme with the Masoretic text. This makes the Greek version suspicious of translating its original freely and harmonizingly: the Masoretic text is preferable to the Septuagint.

One of the benefits of this round is that it provides criteria with which to judge operations critical of literature. If, for example, Christoph Levin inserts a sentence from the Septuagint version into the Masoretic text for the written source he has reconstructed (see below), he must argue against two basic rules of textual criticism: lectio brevior (the shorter text) and lectio difficilior (the more difficult text) are usually better.

Literary criticism

Gen 1,1–2,3 (4a) is a carefully worded text. Nevertheless, there are tensions (“hairline cracks”). As early as the end of the 18th century, theologians found it in need of explanation that eight works of creation were spread over six days of creation. The literary criticism did preparatory work for modern exegesis, but the problems it recognized cannot, in the opinion of most exegetes, be solved by a literary-critical theory.

Works of Creation and Days of Creation

The following table shows the distribution of the works of creation over six days and two possible structuring of the priestly narrative.

| count | Work of creation | Order category | Equivalents | Day |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | light | time | light | First day (sunday) |

| 2 | Firmament | room | Air space and water | Second day (Monday) |

| 3 | Land and sea | room | Mainland | Third day (Tuesday) |

| 4th | plants | Plant food | ||

| 5 | Heavenly bodies | time | light | Fourth day (wednesday) |

| 6th | Animals of the water and the air | room | Air space and water | Fifth day (Thursday) |

| 7th | Land animals | room | Mainland | Sixth day (Friday) |

| 8th | People | Plant food | ||

| time | Sabbath |

Hypotheses of the origin of the text

In 1795, Johann Philipp Gabler was the first to compile the arguments of literary criticism and propose a working hypothesis. Mostly it was assumed that the text of an older source had been pressed into the scheme of a six-day week plus a day of rest, so that two works of creation had to be assigned to the third and sixth day. The literary uniformity has been proven several times; literary-critical stratification attempts have not met with general approval.

Christoph Levin represents a minority opinion by reconstructing a written template for Gen 1 EU . This source listed eight works of creation (only report and naming ); the report on the separation of land and sea is missing in the Masoretic text and is supplemented by Levin after the Septuagint ( Gen 1.9 EU ). Jan Christian Gertz thinks it is possible that there was a model of this type, but it can no longer be delimited in terms of literary criticism.

Lore criticism

The traditional criticism explains the “hairline cracks” as follows: The author was not free to write a completely new text. He added passages that had already gained a firm form in the oral tradition. A creation story in particular offers itself as material that was passed on orally.

Word report and fact report

Werner H. Schmidt accepted an older story (report of the fact), which was later supplemented and corrected by the verbal report and the counting of the days of the week. Odil Hannes Steck objected: "... that the" report of the fact "has been dragged along in the course of tradition against all material necessity speaks against the analysis and its guiding prerequisites." No older, orally circulating creation story can be reconstructed. One only comes across individual motifs that have only been passed down orally and that were brought into a concept by the author of the priestly book. Other exegetes agree.

Scheme of a day of creation

Schmidt coined a number of terms for the formulaic language in which the individual days of creation are told that are still used by Old Testament scholars.

| Word report | Hebrew וַיֹּמֶר אֱלֹהִים ṿayyomer ʾelohim , German 'And God spoke' | Constant formula with which all works of creation are initiated. |

| Confirmation of completion | Hebrew וַיְהִי־כֵן ṿayhi-khen , German 'And so it happened' | The formula follows the verbal report and, according to Schmidt, is based on it.

Steck examined the occurrence of the formula ṿayhi-khen in other passages of the Hebrew Bible: It does not confirm the completion of a commission, but underlines the inner relationship between a word and the subsequent event. Something had happened exactly as it was announced (Steck: "Determination of logical correspondence"). In the sense of Steck you would have to translate instead of “And so it happened”: “And it happened like this ...” |

| Report | "And God separated / made / created" | Mostly as an act of God, but the plants are produced from the earth. According to Schmidt, the fact reports taken together (with names and formulas of approval) are an older oral tradition, according to Levin (fact reports with names) a source text available to the author of the creation story. |

| Naming | Hebrew וַיִּקְרָא אֱלֹהִים לְ ṿayyiḳraʾ ʾelohim le , German 'And God called' | Only for the first three works, the following are not named. |

| Approval formula | Hebrew וַיַּרְא אֱלֹהִים כִּי־טֹוב ṿayyarʾ ʾelohim ki-ṭov , German 'And God saw that it was good' | As the confirmation of execution belongs to the verbal report, so Schmidt, the approval formula relates to the report. He assumed the quality control of the craftsman after the work was done as the seat in the life of the formula. |

| Daily formula | Hebrew וַיְהִי־עֶרֶב וַיְהִי־בֹקֶר יֹום x ṿayhi-ʿerev ṿayhi-voḳer yom x , German 'It was evening and there was morning: day x' | Constant formula, according to Schmidt and others a later addition to the orally transmitted creation story. The day is counted from the onset of darkness; Evening and morning are the beginnings of all night and day hours. |

Editorial criticism

The priestly story of creation is followed in the final text of the Bible as it is available today, the so-called Yahwist story of creation in Genesis 2 EU . It is one of the older material that was put together with the priestly pamphlet by an editor late. As such, the two texts make no reference to one another, they do not complement or correct one another.

The discovery of two creation accounts in the first chapters of Genesis succeeded the Hildesheim pastor Henning Bernhard Witter as early as 1711. He assumed that Moses wrote the Pentateuch. But Moses added older poems to his work. Gen 1,1–2,3 is an old creation poem. Witter's criterion for distinguishing the two accounts of creation was the difference between the divine names Elohim (in Gen 1,1–2,3) and YHWH (in Gen 2,5ff). Witter's writing, Jura Israelitarum , encountered the opposition of his contemporary Johann Hermann von Elswich and was not appreciated until the 20th century.

Gen 1.29–30 (requirement of a vegetarian diet)

Assuming the current supplementary hypothesis to the priestly script, it must first be clarified whether in the text of Gen 1,1–2,4a, in addition to the basic script P g , subsequent additions can be identified. The requirement of a vegetarian diet, gene 1.28–30 EU , is most likely to be suspected of being a secondary gain P s . According to Arneth's analysis, however, this text was ready when Gen 9.1–3 EU was drafted , and both text sections belong to the basic font P g .

So at the beginning of the Bible the reader encounters a story that was once the prelude to the source Priestly Scripture, and that without any subsequent additions. It is therefore to be expected that the intentions of the priestly scriptures will come out clearly at the beginning. If the goal of the narrative is God's rest on the seventh day ( Gen 2,1–3 EU ), these sentences could echo motifs that are later taken up by the priestly scriptures.

Gen 2,4a (Toledot formula)

In Gen 2,4 EU you can see the final editor at work, as he puts together two previously independent texts. Where exactly does the priestly script break off, where does the older tradition (“Yahwist”) begin, and is there a transition between the two that was only created by the final editor?

In verse 4a, the so-called Toledot formula (“This is the family tree / the genesis of ...”) is encountered, a structure element typical of the priestly scriptures. Otherwise it is always to be understood as a heading over the following text, but here as a signature. The narrative thread of the priestly scripture is taken up again with Gen 5,1 EU , also a Toledot formula. The difficulty is twofold: the Toledot formula is used in an unusual way, and two Toledot formulas meet.

- One proposed solution is to move the sentence from 2.4a EU to its supposedly original location and put it as the title above Gen 1.1ff EU . However, this puts the sentence in competition with the Mottovers Gen 1.1 EU . It's less likely.

- Even Gerhard von Rad and others had in 2,4a EU seen the addition of an editor-in for Priestly, a solution that has won recently proponents. Walter Bührer understands 2.4a EU as an editorial partial verse between the two reports of creation, which, viewed synchronously, forms the heading over the following text. This has been implemented by the revised standard translation . It treats Gen 2,4 EU as the prelude to the second (so-called Yahwist) creation report.

- Martin Arneth, Peter Weimar and others continue to take the classic position. Arneth sees in Gen 1,1 EU and Gen 2,4a EU the framework around the creation story; both sentences are chiastically applied to one another.

Even if there is no consensus in current research, there is some evidence that verse 2.3 EU was the final sentence of the priestly written creation story and that the fugue runs at this point and not, as was the consensus of exegesis for a long time, right through verse 2 , 4 EU .

Aspects of the history of the motif

In 1894 Hermann Gunkel put forward the thesis that the authors of Genesis 1 EU had received Babylonian material as something of their own and at the same time transformed it in a kind of purification process. Since then, the priestly account of creation has been compared primarily with motifs from the Enûma elîsch . This narrowing is also due to the fact that Claus Westermann placed a focus on the history of religion in his large commentary on prehistory, but the text of the Atraḫasis epic was only accessible when the first delivery of the commentary was already in print.

As recently as 1997, Bauks pointed out that it was not really known how the authors of the priestly pamphlet obtained knowledge of these much older sources. For this purpose, Gertz designed the following scenario in 2018: The authors of the creation story drew their knowledge of the world from the Mesopotamian, Egyptian, but also Greek cultural areas. The systematization of living beings, for example, is reminiscent of the natural philosophy of the pre-Socratics ( Anaximander , Anaximenes ) who in turn had knowledge of Neo-Assyrian texts. One could speak of an Eastern Mediterranean-Middle Eastern cultural and scientific area that was primarily inspired by Mesopotamia. The Old Testament book of Ezekiel also took part in this exchange of information.

In the following, only a few substances from Israel's environment are presented that are interesting for understanding the priestly story of creation. The list could be expanded, for example to include ancient texts that describe vegetarianism as the way of eating of primeval people.

Mesopotamia

Enûma elîsch

The priestly scriptures describe the creation of the world as the work of a god who first creates a world in a compact act of creation and then assigns the various creatures their place in it. In the Enûma elîsch, on the other hand, the primeval world is in a process of constant change, from which clear structures only gradually emerge. The epic celebrates the god Marduk . This results in some points of contact with the Bible text: Marduk, too, is capable of creating through the word for his admirers. He can make zodiac signs disappear by his command. Compared to Marduk, the astral gods can be described as mere "star sheep".

Atraḫasis epic

In the Atraḫasis epic , people are created to relieve the gods of work. You live in an unstable world order with an uncertain fate. The gods get tired of people and decide to destroy them with a flood. The connection of the creation story and the tale of the flood is constitutive for the priestly scriptures, even if the flood is motivated differently. Thus, the Atraḫasis epic is not only comparable in terms of individual motifs, but also in its conception with the priestly writings.

Creation account of Berossus

The creation story of the Marduk priest Berossus has a great resemblance to the priestly script : “There was, he says, a time in which the universe was darkness and water ... Then Bel , who is translated as Zeus , cut the darkness right through and so earth and heaven are separated from each other and the world is in order. ”According to Russell Gmirkin, the parallels between Genesis and Enûma elîsch can also be found in Berossos. But Berossos and Genesis also have similarities, for example the creation of animals, which the Enûma elîsch omits.

Levant

Northwest Semitic Chaos Fight Myth

For the possible reception of this myth in Jerusalem see: YHWH's accession to the throne .

In Mesopotamia, Ugarit and also in Israel the idea was widespread that the Creator God must throw down the waters of chaos in a fight so that a habitable world can arise. Georg Fohrer formulated a consensus of research in 1972 when he noted close connections between Gen 1,2 EU and the chaos war myth: "Water and darkness as characteristics of chaos, the creation of the world by splitting the primeval tide ( Tiamat -Tehom) and the Building the world. ”Today becomes Hebrew תְּהוֹם tehom , German 'Urmeer, Urflut' etymologically derived from the common * tiham "sea". The name of the deity Tiamat also comes from this root. The word tehom does not already reflect the memory of the Tiamat myth, as researchers of the Fohrers generation assumed.

Statue of Hadad-yis'i

The Assyrian-Aramaic bilingualism on the basalt statue of Hadad-yis'i at Tell Fecheriye is interesting in two ways.

She is an epigraphic ( altaramäischer ) evidence of the in Gen 1.26 EU occurring pair of terms in Hebrew צֶלֶם tselem , German 'image, image, statue' and Hebrew דְּמוּת humility , German 'replica, shape, image' . Accordingly, the two terms have practically the same meaning. Second, you learn what function the statue had: It represented the absent king. The picture could take on tasks that were due to the king and receive benefits (bonuses) on behalf of the king.

Egypt

Ancient Egyptian royal ideology

See also: The king as a concrete image of God

Since the Second Intermediate Period , the Pharaoh was regarded as the earthly image of the deity. "The decisive factor here is the fact that the" image "(the king) is not the image of an imagined figure (the deity), but a body that gives the deity a physical form." This legitimation of power is used as the background for the talk of People viewed as a statue of God in Gen 1.26 EU .

Shabaka stone

With the so-called memorial of Memphite theology on the Shabaka stone, the priesthood of Memphis established the primacy of the god Ptah . As the Creator God, he lets all things arise in his heart and his tongue transmits them as a command. After completing his work of creation, Ptah rests. Jan Assmann dated this text to the late period ; thus it comes close to the priestly scriptures. Assmann also pointed out two essential differences to Genesis 1 EU : the “heart” stands for the planning conception of the works of creation, their design; the hieroglyphic writing is a repertoire of symbols that corresponds to the works of creation. So Ptah create all things with their hieroglyphics.

Text of the creation story

Mottovers (Gen 1.1)

The very first word in the Bible, Hebrew בְּרֵאשִׁית bereʾshit , German 'at the beginning, from the beginning, first' , is controversial in its interpretation. After a word field analysis, Bauks came to the conclusion that the ambiguity of the term was a trick of the narrator. It allows "the interpretation as the absolute beginning point, as the beginning of the divine creative act and as the early or prehistory of the history of Israel."

Is Hebrew בְּרֵאשִׁית ready to be understood as status absolutus , the article is missing. That is why the Septuagint and Targum Onkelos translate : "In a beginning ...". If there is a status constructus , the noun rectum is missing , which could answer the question: “At the beginning of what?”. You can help yourself here by using the rest of Gen 1.1 EU as a replacement for a noun rectum . Syntactically , the beginning of the text is therefore difficult: “Is 1.1 a main clause or a subordinate temporal clause? If 1 is a subordinate clause, is the main clause verse 2 or verse 3? ”Like the majority of translators, Westermann decided to use verse 1 as the main clause and heading. However, this is not mandatory. One can Gen 1.1 EU as adverbial antecedent understand: "When God began to create heaven and earth, the world was without form and void, and the breath of God was moving over the water."

In Gen 1,1 EU we encounter a verb that is used exclusively for God's creative activity and is never associated with a material specification: Hebrew ברא baraʾ . It is only documented in exilic or later texts, in addition to the priestly scriptures especially in the book of Isaiah (so-called Deutero - Isaiah and updates). There it stands for past creative activity as well as for future new creation, but in the priestly scriptures only for the creation of the world.

Today there is a consensus of research that "heaven and earth" as merism is the biblical Hebrew name for the cosmos. In the opinion of many exegetes, Gen 1,1 EU precedes the creation story like a heading and forms a frame with Gen 2,3 EU .

Pre-world description (Gen 1, 2–3)

Westermann worked out that the statements in Gen 1,2 EU belong to the “as-not-yet” formulations that are well-known from parallels in the history of religion. They delimit the world of creation from an actually indescribable before.

Verse 2 presents the reader with the three sizes of earth (as tohu ṿavohu , Luther translation: 'desolate and empty'), Hebrew חֹשֶׁךְ ḥoshekh , German for 'darkness' and Hebrew תְּהוֹם tehom , German for 'primeval sea, primeval flood' . They are not created, but are presupposed in creation. The hubbub , in Hebrew תֹּהוּ וָבֹהוּ tohu ṿavohu , is proverbial in German: The first part of the formula (tohu) describes an environment in which people cannot survive. The second part (vohu) is added onomatopoeic . It has no independent meaning. The “ primeval night” ḥoshekh , as “non-light”, represents the contrast image to the beginning of creation. Tehom is the deep sea, which implies a certain danger, but also the original source that makes the land fertile. Since the narrator does not differentiate between fresh and salt water, he does not face the problem of how plants can grow through sea water. In contrast, Babylonian texts differentiate between the freshwater ocean ( Apsu ) and the saltwater ocean ( water of death ).

The spectrum of meanings of Hebrew רוַּח ruaḥ includes “all types of moving air.” Some interpreters translate “ ruaḥ of God” as “God's storm”, in the sense of a superlative: a strong storm. This interpretation, which comes from the Jewish tradition ( Philo , David Kimchi ), also has some representatives in Christian exegesis, but can be considered a minority opinion. Two alternative interpretations are then available: While some exegetes see the ruaḥ as God's tool in creation, others consider it possible that this ruaḥ is God in his pre- worldly form of existence. "Similar to an Israeli counterpart to the Urlotus , Urei or the Egyptian Goose , the divine seems to be present in the breath of wind, without acting and having already developed its power."

Six days of creation

First day: day and night (Gen 1, 4–5)

In response to the Creator's word, light has flooded in and has put the prehistoric world "into a gloomy twilight state." This creates day and night. By naming them, God subordinates them to his rule. This is particularly important in the case of darkness and (on the following day) primeval flood, because here the conditions of the past are transformed.

Second day: firmament (Gen 1, 6–8)

God "makes" the vault of heaven, Hebrew רָקִיעַ raḳiʿa , for the vertical separation of the water. The word actually means pounded, hammered. What is meant is "that blue sky that seems to bulge over the earth." How the vault is made and what is above the vault is of no further interest. The visions in the Book of Ezekiel ( Ez 1,22–26 EU ; Ez 10.1 EU ) and Mesopotamian texts that describe a celestial geography are quite different . Cornelis Houtman considered it inadmissible to enter elements from other biblical texts, such as the pillars or windows of heaven, as embellishment of what was meant in the creation story. The narrator is only interested in the purpose of the raḳiʿa : it protects the earth and its inhabitants from the upper waters, which he holds back.

Third day: mainland and flora (Gen 1, 9–13)

The third day of creation brings the work of the second day of creation to a close. There God has separated the upper water from the lower water, here the lower water is drawn together in its place, the sea, so that the mainland emerges, to which the narrator's interest turns. God gives something of his creative power to the earth: "Let the earth turn green in the green." Plants were not considered to be living beings, since no breath of life was observed in them. "The narrator is not interested in the fact that there are mountains and valleys on earth, but that it is the table laid for living beings."

Fourth day: sun, moon and stars (Gen 1: 14-19)

It is not until day four that, surprisingly for the modern reader at this point, the creation of the stars - after the light has been present since the first day.

Schmidt and others see a polemic against astral religions in the section Gen 1, 14-19 EU : The priestly narrator has degraded the heavenly lights to "lamps" and avoids calling the sun and moon by name. However, not all exegetes accept a polemical point against other religions. One can also argue that the priestly scriptures consistently create categories into which the forms of life are sorted; "Lights" is the generic term for sun and moon.

You are assigned three tasks:

- to distinguish between day and night (God himself performed this task on the first day of creation);

- to enable orientation in the course of the year;

- to illuminate the earth.

Fifth day: animals of water and air (Gen 1: 20-23)

From day five it is about the creation of living beings. Just as in the divine speeches in the Book of Job , Gen 1: 20-23 EU describes an animal world that is not judged according to its usefulness for humans. It also includes creepy, dangerous life forms. This is a potentially interesting impetus for environmental ethics today . The look begins at the sea serpents ( Hebrew תַּנִּינִם tanninim ) and continues through the "swarm" of aquatic animals to the flight animals. The diversity of living beings is illustrated in verse 20 by a twofold Figura etymologica :

- Hebrew יִשְׁרְצוּ… שֶׁרֶץ yishretsu sherets , German , 'teem should swimm ...' ;

- Hebrew וְעֹוף יְעֹופֵף ṿeʿof yeʿofef , German '... and flying animals should fly' .

God equips - a new element of the narrative - the creatures with his blessing . They are supposed to multiply and take over their habitat.

Day six: land animals and people

Land animals (Gen 1,24-25)

The classification of the diverse animal world in groups is a form of ancient oriental "science" and an important topic especially for the priestly scriptures ( sacrifice and food commandments ). This bears no resemblance to modern zoology, as the division of land animals in Gen 1.24–25 EU clearly shows:

- Hebrew חַיַּת הָאָרֶץ ḥayyat haʾarets , German 'wild' ;

- Hebrew בְּהֵמָה behemah , German “cattle” ;

- Hebrew רֶמֶשׂ remeś , German 'creeping small animal ' , for example reptiles, small mammals, insects.

They all compete with humans for the mainland habitat. Therefore, in their case, the blessing and the associated mandate to fill the living space are omitted. This interpretation comes from Benno Jacob's Genesis commentary and can be used as an example of impulses that today's Christian exegesis takes from the Jewish tradition of interpretation.

Humans (Gen 1,26-28)

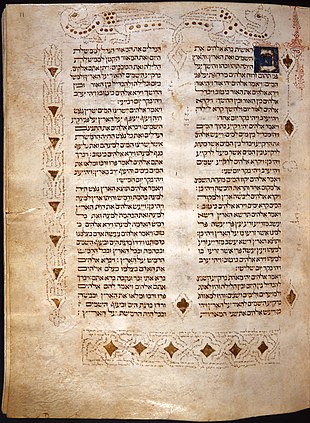

The illustration of the Gutenberg Bible for Genesis 1 (photo) shows that the creation of humans in Gen 1, 26–28 EU in the Christian tradition was usually illustrated with the information from Gen 2, 7, 21–22 EU . There is a prehistoric couple, and the woman is created from the man's side or rib. The priestly scripture is different: God creates mankind; in the case of humans and animals, it is "genera, but not individual specimens, which only play a role in Noah's" ark "."

The following interpretations have been suggested for the unusual plural in verse 26 (“Let's make people…”).

Grammatical:

- Pluralis majestatis (sovereign plural);

- Pluralis deliberationis (plural expressions of intent / self-advice);

Content:

- God the Father speaks to Jesus Christ . This understanding of the text is already widespread in the early Church , for example with Ambrose of Milan : “To whom does God speak? Apparently not to himself; for he does not say: let me do it, but: let us do it. Not even to the angels, for they are his servants; between servant and master, between creature and creator, there can be no community of activity. Rather, he speaks to his son, whether the Jews do not like it, the Arians may resist it. ”This is a dogmatic Christian relecture .

- “God joins the heavenly beings of his court and hides himself again in this plural.” What speaks against this interpretation favored by many exegetes is that the priestly scriptures do not otherwise mention a heavenly court. But it is well attested in the Hebrew Bible as a whole. The Jewish tradition has mostly interpreted the heavenly beings as angels. Jacob refers approvingly to Raschi's classic Torah commentary , which explains at this point that God is discussing himself with his familia - here as a Latin loan word (wortליא) in Raschi's Hebrew text.

- In Mesopotamian myths, several gods work together in human creation. Each deity gives off some of its own gifts and qualities. “It is the collective of gods and not the individual deity that creates man.” This can still be present in the background to the narrator, even if he does not develop the motif.

Three sizes are assigned to one another in Gen 1,26–27 EU : God - man - environment. The understanding of the Hebrew text was long shaped by the Christian theological concept of being in the image of God . It was about determining the relationship between God and man, about something in the essence of man (for example language, understanding) that makes him the image of God. As Hebrew צֶלֶם tselem , traditionally translated as “image”, is the cult image that represents the deity; Norbert Lohfink coined the term “statue of God” for this. Some more recent commentators ( Walter Groß , Bernd Janowski , Ute Neumann-Gorsolke) consistently reject a statement about the essence of human beings derived from the term tselem . Based on historical parallels in the Levant and Egypt, the following understanding of the text results: The term tselem serves to determine the relationship between man and the environment. As "statues of God" people are representatives of God in the world. A metaphor from the ancient Egyptian royal ideology is applied to every man and woman in priestly scriptures. They perform tasks on behalf of God, just as Hadad-yis'i's statue could replace this king in certain functions.

Frank Crüsemann translated into fair language for the Bible : "God created Adam, men, as a divine image, they were created as the image of God, male and female he has, God has created them." ( Gen 1:27 EU ) Jürgen Ebach explained this free rendering of the Hebrew text: "If male and female people are God's images, God alone cannot be male." With this understanding of the text, Hebrew צֶלֶם tselem interesting again for similarities between God and man. If, however, with Janowski and others, tselem are understood as representatives of God in relation to the environment, there is no room for such an interpretation.

Mandate to rule

God's blessing for people ( Gen 1.28 EU ) includes ruling over other living beings as God's agents ( Dominium terrae ). The following verbs specify what is meant by rule:

- Hebrew כבש kavash "trample". The violent connotation (“enslave, humiliate”) is evident here, even if Norbert Lohfink and Klaus Koch suggested alternative interpretations.

- Hebrew רדה radah . Research is discussing whether the verb only has violent connotations ("trample", like grapes in the wine press) or also peaceful ("guard"). The interpretation as violent behavior initially dominated. In 1972 James Barr initiated a rethink with the thesis that the verb radah should be understood from the ancient oriental ideal of the royal shepherd. In the German-speaking world, Norbert Lohfink, Klaus Koch, Erich Zenger and others represented this type of interpretation. The Good News Bible adopts the motif of the royal shepherd, which it also unfolds as a communicative translation : “Fill the whole earth and take possession of it! I put you over ... all animals that live on earth and entrust them to your care. ”The revised standard translation (2016) also follows this tradition and translates radah as“ to rule ”.

In terms of reception, it should be emphasized that the Council of the EKD and the German Bishops' Conference in 1985 formulated in a joint declaration: “Startled by the extent of the destruction of our environment that has become apparent and triggered by the modern interpretation of the Scriptures, we ask the Bible ... about what God willed relationship of man to his fellow creatures. "A key role has the explanation of the terms kavash and Radah ( Gen 1.28 EU :)" Untertanmachen means (Genesis 1:28), earth (the ground) with its sprawl make submissive, docile " to create cultivated land where there was previously wilderness. “The rule of humans over the animal world stands out from the subjugation of the soil ... clearly. It reminds of the rule of a shepherd towards his flock…. God orders man to lead and cherish the animal species (Genesis 1:26, 28). ”However, it is not clear what a way to lead and cherish marine animals at the time the priesthood was written.

Walter Groß summarized the course of the exegetical discussion in 2000 as follows: authoritative exegetes “at the height of ecological concern” had inclined to the supposedly gentle shepherd image; since this dismay had subsided, "rather violent concepts of rule" had come to the fore again. Andreas Schüle judged in 2009: The terms of rulership had a “despotic and even violent tone” in Hebrew. The ruling task of man in a raw world is to “prevent and hold down the spread of violence.” Similar to Annette Schellenberg 2011: Da the verbs radah and kavash appear as a pair, the result is no particularly harmonious picture of the human-animal relationship.

First Food Laws (Gen 1: 29-31)

The creation story and the flood story are related to one another in the priestly scriptures. In the world of the beginning there is no need to kill living things, not even for food. According to Gen 1.29-31 EU, humans and animals are vegetarians with a separate menu. Since fish and pets do not compete with humans for food, they are not specifically mentioned here. This food order relativizes the ruling mandate previously given to people. In any case, it is not necessary to kill living beings in order to make a living. Since the priestly scriptures do not recognize the fall of man , the description of a world follows that - however - has been filled with violence ( Gen 6:11 EU ) and narrowly escaped its destruction in the flood. At the end of the priestly tale of the Floods, meat is tolerated as food ( Gen 9.3 EU ).

Rest on the seventh day (Gen 2: 1-3)

With the divine rest on the seventh day, the goal of the story is reached. Even if the verb used here is Hebrew שבת shavat , German to separate ' to stop' linguistically from the noun Hebrew שַבָּת Shabbat , "these sentences reflect the later justification of the Sabbath ." Gunkel saw an etiology in verses 2, 1–3 EU . When asked why the Sabbath is a day of rest from work, the myth answers with an anthropomorphism : Because God himself rested from his work on the seventh day. This is contradicted by the fact that the text lacks instructions. It describes a calm that is there independently of human activity or perception. Although not a living being, the seventh day is blessed and sanctified by God. It should persist and with it the weekly structure of time. Gen 2: 1–3 points beyond itself; the meaning of the seventh day is not yet revealed here. This only happens in the manna story Ex 16 EU , which is a key text of the priestly scriptures : Under the guidance of Moses, Israel learns to celebrate the Sabbath.

Gen 2.1–3 EU points to further narratives that are important in the entire work of the priestly scriptures:

- After six days of silence, on the seventh day, God spoke to Moses in Sinai ( Ex. 24.16 EU ).

- The verbs complete - bless - holy encounter Ex 39-40 EU again at the completion of the tent sanctuary ( Mishkan ), whereby this sanctuary corresponds to the Jerusalem temple . When Moses establishes the tent sanctuary with the cult devices, it corresponds to God's works of creation. "In this way, creation and the foundation of the temple are set in a corresponding relationship, as in the multitude of the ancient Near Eastern creation texts."

Web links

- Sefaria: Genesis in Hebrew and English with numerous Jewish commentaries and other resources.

- Ute Neumann-Gorsolke: God image (AT). In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

- Annette Schellenberg: Creation (AT). In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

- Christoph Koch: Welt / Weltbild (AT). In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

literature

Text output

- Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia . 5th edition. German Bible Society, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-438-05219-9 .

Tools

- Wilhelm Gesenius : Hebrew and Aramaic concise dictionary on the Old Testament . Ed .: Herbert Donner . 18th edition. Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg 2013, ISBN 978-3-642-25680-6 .

Commentary literature

- Jan Christian Gertz : The first book of Moses (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 (= The Old Testament German . Volume 1 new). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2018, ISBN 978-3-525-57055-5 .

- Hermann Gunkel : Genesis, translated and explained (= Göttinger Handkommentar zum Old Testament. ). 5th edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1922. ( online )

- Benno Jacob : The Book of Genesis . Calwer Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-7668-3514-9 . (Reprint of the work published by Schocken Verlag, Berlin 1934)

- Andreas Schüle: Die Urgeschichte (Genesis 1–11) (= Zurich Bible Commentaries AT, New Series. Volume 1.1). TVZ, Zurich 2009, ISBN 978-3-290-17527-6 .

- Horst Seebaß : Genesis I prehistory (1,1-11,26) . Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn 1996, ISBN 3-7887-1517-0 .

- Gerhard von Rad : The First Book of Mose, Genesis Chapters 1–12.9 (= The Old Testament German . Volume 2). 3. Edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1953.

- Claus Westermann : Genesis 1–11 (= Biblical Commentary . Volume I / 1). Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn 1974, ISBN 978-3-7887-0028-7 .

Monographs and journal articles

- Martin Arneth: Adam's fall completely spoiled ...: Studies on the origins of the Old Testament prehistory (= research on the religion and literature of the Old and New Testaments. Volume 217). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-53080-1 . ( Online. In: . Digi20.digitale-sammlungen.de Feb 28 2012, accessed on November 5, 2018 . )

- Jan Assmann : Theology and wisdom in ancient Egypt . Wilhelm Fink Verlag, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-7705-4069-7 . ( Online. In: . Digi20.digitale-sammlungen.de Feb 28 2012, accessed on November 5, 2018 . )

- Michaela Bauks: The world at the beginning. On the relationship between the pre-world and the emergence of the world in Gen 1 and ancient oriental literature (= scientific monographs on the Old and New Testaments. Volume 74). Neukirchen-Vluyn 1997, ISBN 978-3-7887-1619-6 .

- Michaela Bauks: Genesis 1 as the program script of the priestly script (P g ) . In: André Wénin (Ed.): Studies in the Book of Genesis. Literature, Redaction and History . Leuven University Press 2001, ISBN 90-429-0934-X , pp. 333-345.

- Walter Bührer: "At the beginning ..." Studies on the genesis of the text and the relative-chronological classification of Gen 1–3 (= research on the religion and literature of the Old and New Testaments. Volume 256). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2014, ISBN 978-3-647-54034-4 .

- Jan Christian Gertz: Anti-Babylonian polemics in the priestly account of creation? In: Zeitschrift für Theologie und Kirche 106 (2009), pp. 137–155.

- Walter Groß : Gen 1, 26.27; 9.6: Statue or image of God? Task and dignity of the person according to the Hebrew and the Greek wording. In: Yearbook for Biblical Theology. Vol. 15 (2000), pp. 11-38.

- Cornelis Houtman: Heaven in the Old Testament. Israel's worldview and worldview . Brill, Leiden / New York / Cologne 1992, ISBN 90-04-09690-6 .

- Bernd Janowski : The living statue of God. On the anthropology of priestly prehistory. In: Markus Witte (ed.): God and man in dialogue. Festschrift Otto Kaiser. (= Supplements to the journal for Old Testament science. Volume 345/1) Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2004, ISBN 3-11-018354-4 . Pp. 183-214. ( online )

- Steffen Leibold: Room for Convivence: Genesis as a post-exilic memory figure. Herder, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 2014, ISBN 978-3-451-31577-0 .

- Christoph Levin : Act report and verbal report in the priestly written creation story . In: Updates. Collected studies on the Old Testament (= supplements to the journal for Old Testament science . Volume 316). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2003, ISBN 3-11-017160-0 . Pp. 23-39. First published in: Zeitschrift für Theologie und Kirche 91 (1994), pp. 115-133.

- Norbert Lohfink : The statue of God. Creature and Art according to Genesis 1. In: In the shadow of your wings. Large Bible texts reopened. Herder, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 1999, ISBN 3-451-27176-1 , pp. 29-48.

- Annette Schellenberg: Man, the image of God? On the idea of a special position of man in the Old Testament and in other ancient oriental sources (= treatises on theology of the Old and New Testaments. Volume 101). TVZ, Zurich 2011, ISBN 978-3-290-17606-8 .

- Werner H. Schmidt : The creation story of the priestly scripture. On the transmission history of Gen 1,1–2,4a and 2,4b – 3.24 (= scientific monographs on the Old and New Testament. Volume 17). 3. Edition. Neukirchen-Vluyn 1973, ISBN 3-7887-0054-8 .

- Andreas Schüle: The prologue of the Hebrew Bible. The literary and theological history discourse of prehistory (Gen 1–11) (= treatises on the theology of the Old and New Testaments. Volume 86). TVZ, Zurich 2006, ISBN 978-3-290-17359-3 .

- Odil Hannes Steck : The Creation Report of the Priestly Scripture: Studies on the literary-critical and tradition-historical problems of Gen 1,1–2,4a (= research on the religion and literature of the Old and New Testaments. Volume 115). 2nd Edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1981, ISBN 3-525-53291-1 . ( Online. In: . Digi20.digitale-sammlungen.de Feb 28 2012, accessed on November 5, 2018 . )

- Peter Weimar: Studies on the priestly script (= research on the Old Testament. Volume 56). Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-16-149446-8 .

- Markus Witte: The biblical prehistory: editorial and theological history observations on Gen 1, 1–11, 26 (= supplements to the journal for Old Testament science . Volume 265). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1998, ISBN 3-11-016209-1 .

- Erich Zenger : God's bow in the clouds, investigations into the composition and theology of priestly priestly history. Catholic Bible work, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 978-3-460-04121-9 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Benno Jacob: The book of Genesis . Berlin 1934, p. 64 : “It is annoying that today's chapter division c.2, which originates from the Christian side (first applied by Archbishop Stephan Langton of Canterbury around 1205) already starts here, while the first three verses apparently still belong to c.1. "

- ↑ Hans-Christoph Askani: The problem of translation: presented to Franz Rosenzweig . In: Hermeneutic Reflections on Theology . tape 35 . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1997, ISBN 3-16-146624-1 , p. 209-211 .

- ↑ Walter Bührer: "At the beginning ..." Investigations on the genesis of the text and on the relative-chronological classification of genes 1–3 . Göttingen 2014, p. 26 .

- ↑ Walter Bührer: "At the beginning ..." Investigations on the genesis of the text and on the relative-chronological classification of genes 1–3 . Göttingen 2014, p. 31 (On the basis of the versions, there is only one point to assume that the Codex Leningradensis has been handed down: in verse 1.11 an “and” has been dropped; עץ is to be improved in ועץ.).

- ↑ Christoph Levin: Act report and verbal report in the priestly written creation story . Berlin / New York 2003, pp. 29 .

- ↑ Jan Christian Gertz: The first book of Mose (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 . Göttingen 2018, p. 29 .

- ↑ Gerhard von Rad: The first book of Mose . Göttingen 1953, p. 36 .

- ↑ Christoph Levin: Act report and verbal report in the priestly written creation story . Berlin / New York 2003, pp. 28 .

- ↑ Horst Seebaß: Genesis I Urgeschichte (1,1-11,26) . Neukirchen-Vluyn 1996, p. 90 .

- ↑ Jan Christian Gertz: The first book of Mose (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 . Göttingen 2018, p. 30 .

- ↑ Walter Bührer: "At the beginning ..." Investigations on the genesis of the text and on the relative-chronological classification of genes 1–3 . Göttingen 2014, p. 137 .

- ↑ Markus Witte: The biblical prehistory: editorial and theological-historical observations on Gen 1: 1-11, 26 . Berlin / New York 1998, pp. 119 .

- ↑ Walter Bührer: "At the beginning ..." Investigations on the genesis of the text and on the relative-chronological classification of genes 1–3 . Göttingen 2014, p. 19 .

- ↑ Christoph Levin: Act report and verbal report in the priestly written narrative of creation. Berlin / New York 2003, pp. 31 .

- ↑ Martin Arneth: Adam's fall is completely corrupted ...: Studies on the origin of the Old Testament prehistory . Göttingen 2007, p. 23 : "The reconstructed list ... remains a fragment whose intention is difficult to interpret."

- ↑ Jan Christian Gertz: The first book of Mose (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 . Göttingen 2018, p. 10 .

- ↑ Werner H. Schmidt: Introduction to the Old Testament . 4th edition. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1989, ISBN 3-11-012160-3 , p. 102 .

- ↑ Odil Hannes Steck: The Creation Report of the Priestly Scripture: Studies on the literary-critical and tradition-historical problematic of Gen 1,1–2,4a . 2nd Edition. Göttingen 1981, p. 25-26 .

- ↑ Horst Seebaß: Genesis I Urgeschichte (1,1-11,26) . Neukirchen-Vluyn 1996, p. 91 .

- ↑ Werner H. Schmidt: The creation story of the priestly script. On the transmission history of Gen 1,1–2,4a and 2,4b – 3.24 . 3. Edition. Neukirchen-Vluyn 1973, p. 50-52 .

- ↑ Odil Hannes Steck: The Creation Report of the Priestly Scripture: Studies on the literary-critical and tradition-historical problematic of Gen 1,1–2,4a . 2nd Edition. Göttingen 1981, p. 35-36 .

- ↑ Werner H. Schmidt: The creation story of the priestly script. On the transmission history of Gen 1,1–2,4a and 2,4b – 3.24 . 3. Edition. Neukirchen-Vluyn 1973, p. 61-62 .

- ↑ Jan Christian Gertz: The first book of Mose (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 . Göttingen 2018, p. 32-33 .

- ↑ Erich Zenger: Introduction to the Old Testament . 7th edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2008, p. 90 .

- ^ Martin Mulzer: Witter, Henning Bernhard. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

- ↑ Werner H. Schmidt: Introduction to the Old Testament . 4th edition. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1989, ISBN 3-11-012160-3 , p. 94 .

- ↑ Martin Arneth: Adam's fall is completely corrupted ...: Studies on the origin of the Old Testament prehistory . Göttingen 2007, p. 80-82 .

- ↑ Gerhard von Rad: The first book of Mose . 3. Edition. Göttingen 1953, p. 54 .

- ↑ Jan Christian Gertz, Angelika Berlejung, Konrad Schmid, Markus Witte (eds.): Basic information of the Old Testament . An introduction to Old Testament literature, religion, and history. 5th edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2016, ISBN 978-3-8252-4605-1 , p. 239 .

- ↑ Walter Bührer: "At the beginning ..." Investigations on the genesis of the text and on the relative-chronological classification of genes 1–3 . Göttingen 2014, p. 148-149 .

- ↑ Peter Weimar: Studies on the priestly scriptures . Tübingen 2008, p. 162-163 .

- ↑ Martin Arneth: Adam's fall is completely corrupted ...: Studies on the origin of the Old Testament prehistory . Göttingen 2007, p. 25-26 .

- ^ Tablet Inscribed in Akkadian. In: Morgan Library & Museum. Retrieved September 17, 2018 .

- ^ Jan Christian Gertz: Anti-Babylonian polemics in the priestly account of creation? In: ZThK . 2009, p. 137-138 .

- ^ Rainer Albertz: The theological legacy of the Genesis commentary by Claus Westermann . In: Manfred Oeming (Ed.): Claus Westermann: Life - Work - Effect . LIT Verlag, Münster 2003, ISBN 3-8258-6599-1 , p. 84 (Summarized in an addendum to the second delivery (1967).).

- ↑ Michaela Bauks: The world at the beginning. On the relationship between the pre-world and the origins of the world in Gen 1 and ancient oriental literature . Neukirchen-Vluyn 1997, p. 64 .

- ^ A b Jan Christian Gertz: The first book of Mose (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 . Göttingen 2018, p. 21 .

- ^ Jan Christian Gertz: Anti-Babylonian polemics in the priestly account of creation? In: ZThK . 2009, p. 151-152 .

- ↑ Horst Seebaß: Genesis I Urgeschichte (1,1-11,26) . Neukirchen-Vluyn 1996, p. 85 (Examples: Ovid, met. 15,96ff., Fast. 4,395ff.).

- ↑ Andreas Schüle: The prehistory (Genesis 1–11) . Zurich 2009, p. 21 .

- ↑ Claus Westermann: Genesis 1–11 . Neukirchen-Vluyn 1974, p. 154 .

- ↑ a b Christoph Levin: Act report and verbal report in the priestly written creation story . Berlin / New York 2003, pp. 37 .

- ↑ Jan Christian Gertz: The first book of Mose (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 . Göttingen 2018, p. 56 .

- ↑ Andreas Schüle: The prehistory (Genesis 1–11) . Zurich 2009, p. 21 .

- ↑ Christoph Levin: Act report and verbal report in the priestly written creation story . Berlin / New York 2003, pp. 34 .

- ↑ Russell E. Gmirkin: Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus . Hellenistic histories and the date of the Pentateuch. T & T Clark international, New York 2006, ISBN 0-567-02592-6 , pp. 93-94 .

- ↑ Georg Fohrer: Theological basic structures of the Old Testament . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1972, ISBN 3-11-003874-9 , pp. 68 .

- ↑ Walter Bührer: "At the beginning ..." Investigations on the genesis of the text and on the relative-chronological classification of genes 1–3 . Göttingen 2014, p. 106 .

- ^ Wilhelm Gesenius: Hebrew and Aramaic concise dictionary on the Old Testament . Ed .: Herbert Donner. 18th edition. Berlin / Heidelberg 2013, p. 1426 .

- ↑ Michaela Bauks: The world at the beginning. On the relationship between the pre-world and the origins of the world in Gen 1 and ancient oriental literature . Neukirchen-Vluyn 1997, p. 122-123 .

- ↑ a b Andreas Schüle: The prologue of the Hebrew Bible. The literary and theological history discourse of prehistory (Gen 1–11) . Zurich 2006, p. 89-90 .

- ↑ Bernd Janowski: The living statue of God. On the anthropology of priestly prehistory . Berlin / New York 2004, pp. 190 .

- ↑ Jan Christian Gertz: The first book of Mose (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 . Göttingen 2018, p. 44 .

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Theology and wisdom in ancient Egypt . Munich 2005, p. 27-30 .

- ↑ MS. Canonici Or. 62. In: Bodleian Library. Retrieved September 12, 2018 .

- ↑ Michaela Bauks: The world at the beginning. On the relationship between the pre-world and the origins of the world in Gen 1 and ancient oriental literature . Neukirchen-Vluyn 1997, p. 93-98 .

- ↑ Michaela Bauks: The world at the beginning. On the relationship between the pre-world and the origins of the world in Gen 1 and ancient oriental literature . Neukirchen-Vluyn 1997, p. 98 .

- ↑ Walter Bührer: "At the beginning ..." Investigations on the genesis of the text and on the relative-chronological classification of genes 1–3 . Göttingen 2014, p. 88 .

- ↑ Claus Westermann: Genesis 1–11 . Neukirchen-Vluyn 1974, p. 130 .

- ↑ Andreas Schüle: The prologue of the Hebrew Bible. The literary and theological history discourse of prehistory (Gen 1–11) . Zurich 2006, p. 69 .

- ^ A b Jan Christian Gertz: The first book of Mose (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 . Göttingen 2018, p. 38 .

- ↑ Cornelis Houtman: Heaven in the Old Testament. Israel's worldview and worldview . Leiden / New York / Cologne 1992, p. 78 .

- ↑ Walter Bührer: "At the beginning ..." Investigations on the genesis of the text and on the relative-chronological classification of genes 1–3 . Göttingen 2014, p. 102 .

- ↑ Claus Westermann: Genesis 1–11 . Neukirchen-Vluyn 1974, p. 63 .

- ↑ Odil Hannes Steck: The Creation Report of the Priestly Scripture: Studies on the literary-critical and tradition-historical problematic of Gen 1,1–2,4a . 2nd Edition. Göttingen 1981, p. 223 .

- ↑ Michaela Bauks: The world at the beginning. On the relationship between the pre-world and the origins of the world in Gen 1 and ancient oriental literature . Neukirchen-Vluyn 1997, p. 118 .

- ↑ Michaela Bauks: The world at the beginning. On the relationship between the pre-world and the origins of the world in Gen 1 and ancient oriental literature . Neukirchen-Vluyn 1997, p. 118-119 .

- ↑ Michaela Bauks: The world at the beginning. On the relationship between the pre-world and the origins of the world in Gen 1 and ancient oriental literature . Neukirchen-Vluyn 1997, p. 124-125 .

- ↑ Andreas Schüle: The prehistory (Genesis 1–11) . Zurich 2009, p. 37-38 .

- ↑ Jan Christian Gertz: The first book of Mose (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 . 3. Edition. Göttingen 1953, p. 42-43 .

- ^ Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Pustkuchen: The prehistory of mankind in its full scope . Lemgo 1821, p. 4 .

- ↑ Walter Bührer: "At the beginning ..." Investigations on the genesis of the text and on the relative-chronological classification of genes 1–3 . Göttingen 2014, p. 107 .

- ↑ Jan Christian Gertz: The first book of Mose (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 . Göttingen 2018, p. 44 .

- ↑ Michaela Bauks: The world at the beginning. On the relationship between the pre-world and the origins of the world in Gen 1 and ancient oriental literature . Neukirchen-Vluyn 1997, p. 318 .

- ↑ Gerhard von Rad: The first book of Mose, Genesis chapter 1–12,9 . 3. Edition. Göttingen 1953, p. 40 .

- ↑ Jan Christian Gertz: The first book of Mose (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 . Göttingen 2018, p. 46 .

- ^ Wilhelm Gesenius: Hebrew and Aramaic concise dictionary on the Old Testament . Ed .: Herbert Donner. 18th edition. Berlin / Heidelberg 2013, p. 1268 .

- ^ Benno Jacob: The book of Genesis . Berlin 1934, p. 38 .

- ↑ Jan Christian Gertz: The first book of Mose (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 . Göttingen 2018, p. 49-50 .

- ↑ Cornelis Houtman: Heaven in the Old Testament. Israel's worldview and worldview . Leiden / New York / Cologne 1992, p. 314 .

- ↑ Cornelis Houtman: Heaven in the Old Testament. Israel's worldview and worldview . Leiden / New York / Cologne 1992, p. 303 .

- ↑ Walter Bührer: "At the beginning ..." Investigations on the genesis of the text and on the relative-chronological classification of genes 1–3 . Göttingen 2014, p. 58 .

- ↑ Claus Westermann: Genesis 1–11 . Neukirchen-Vluyn 1974, p. 172 .

- ↑ Erich Zenger: The creation stories of Genesis in the context of the ancient Orient . In: World and Environment of the Bible . 1996, p. 26 .

- ↑ Werner H. Schmidt: The creation story of the priestly script. On the transmission history of Gen 1,1–2,4a and 2,4b – 3.24 . 3. Edition. Neukirchen-Vluyn 1973, p. 119 .

- ↑ Christoph Levin: Act report and verbal report in the priestly written creation story . Berlin / New York 2003, pp. 34 .

- ↑ Jan Christian Gertz: The first book of Mose (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 . Göttingen 2018, p. 56 .

- ↑ Jan Christian Gertz: The first book of Mose (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 . Göttingen 2018, p. 53 .

- ↑ Andreas Schüle: The prehistory (Genesis 1–11) . Zurich 2009, p. 40-41 .

- ↑ Jan Christian Gertz: The first book of Mose (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 . Göttingen 2018, p. 57 .

- ↑ Jan Christian Gertz: The first book of Mose (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 . Göttingen 2018, p. 60 .

- ^ Benno Jacob: The book of Genesis . Berlin 1934, p. 56 .

- ↑ Andreas Schüle: The prehistory (Genesis 1–11) . Zurich 2009, p. 42 .

- ↑ Walter Groß: Gen 1, 26.27; 9.6: Statue or image of God? Task and dignity of man according to the Hebrew and Greek wording . In: JBTh . 2000, p. 31-32 .

- ↑ Horst Seebaß: Genesis I Urgeschichte (1,1-11,26) . Neukirchen-Vluyn 1996, p. 83 .

- ↑ Jan Christian Gertz: The first book of Mose (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 . Göttingen 2018, p. 61-62 .

- ↑ a b Andreas Schüle: The prehistory (Genesis 1–11) . Göttingen 2018, p. 42 .

- ↑ Ambrose of Milan: Exameron. The sixth day. Ninth Homily. Chapter VII. In: Library of the Church Fathers. Retrieved September 3, 2018 .

- ↑ Gerhard von Rad: The first book of Mose, Genesis chapter 1–12,9 . 3. Edition. Göttingen 1953, p. 45-46 .

- ^ Benno Jacob: The book of Genesis . Berlin 1934, p. 57 .

- ↑ Annette Schellenberg: Man, the image of God? On the idea of a special position of humans in the Old Testament and in other ancient oriental sources . Zurich 2011, p. 76–78 (This corresponds to the meaning of the Akkadian word salmu (m).).

- ↑ Norbert Lohfink: The statue of God. Creature and Art according to Genesis 1 . Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 1999, p. 29 .

- ↑ Annette Schellenberg: Man, the image of God? On the idea of a special position of humans in the Old Testament and in other ancient oriental sources . Zurich 2011, p. 70-72 .

- ↑ Andreas Schüle: The prehistory (Genesis 1–11) . Zurich 2009, p. 44 : “Against this background, the biblical Imago Dei has often been interpreted as the democratization of royal dignity. The term democratization is of course not a happy one, provided that in ancient Israel the idea of the Imago Dei apparently coexisted smoothly with the reality of slavery. "

- ↑ Ulrike Bail et al. (Ed.): Bible in Righteous Language . Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh 2006, ISBN 978-3-579-05500-8 , p. 32 ( Ludger Schwienhorst-Schönberger pointed out that the translation should use the passive voice in order to avoid the masculine pronouns he and sein . See: Ludger Schwienhorst-Schönberger: Interpretation instead of translation? A criticism of the "Bible in just language." In: Herder Korrespondenz 1/2007, pp. 20-25.).

- ↑ Jürgen Ebach: God and Adam, no rib and the snake that has "more on it". Notes on the translation of the first chapters of Genesis in the "Bible in Righteous Language". In: www.bibel-in-gerechter-sprache.de. Retrieved September 17, 2018 .

- ^ Wilhelm Gesenius: Hebrew and Aramaic concise dictionary on the Old Testament . Ed .: Herbert Donner. Berlin / Heidelberg 2013, p. 527 .

- ↑ a b Annette Schellenberg: Man, the image of God? On the idea of a special position of humans in the Old Testament and in other ancient oriental sources . Zurich 2011, p. 54-55 .

- ^ Wilhelm Gesenius: Hebrew and Aramaic concise dictionary on the Old Testament . Ed .: Herbert Donner. 18th edition. Berlin / Heidelberg 2013, p. 1221 .

- ↑ Jan Christian Gertz: The first book of Mose (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 . Göttingen 2018, p. 68 .

- ↑ a b Annette Schellenberg: Man, the image of God? On the idea of a special position of humans in the Old Testament and in other ancient oriental sources . Zurich 2011, p. 51 .

- ↑ Erich Zenger: God's bow in the clouds, investigations into the composition and theology of priestly priestly prehistory . Stuttgart 1983, p. 91 (Zenger does not go into the more problematic verb kavash at all).

- ^ Council of the EKD, German Bishops' Conference: Taking responsibility for creation. § 46, 50, 51. In: EKD. May 14, 1985. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Walter Groß: Gen 1, 26.27; 9.6: Statue or image of God? Task and dignity of man according to the Hebrew and Greek wording . In: JBTh . 2000, p. 21-22 .

- ↑ Andreas Schüle: The prehistory (Genesis 1–11) . Zurich 2009, p. 45 .

- ↑ Andreas Schüle: The prehistory (Genesis 1–11) . Zurich 2009, p. 46 .

- ↑ Annette Schellenberg: Man, the image of God? On the idea of a special position of humans in the Old Testament and in other ancient oriental sources . Zurich 2011, p. 48-49 .

- ↑ Jan Christian Gertz: The first book of Mose (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 . Göttingen 2018, p. 70 .

- ↑ Claus Westermann: Genesis 1–11 . Neukirchen-Vluyn 1974, p. 237 .

- ^ Hermann Gunkel: Genesis, translated and explained . 5th edition. Göttingen 1922, p. 115 .

- ↑ Gerhard von Rad: The first book of Mose, Genesis chapter 1–12,9 . 3. Edition. Göttingen 1953, p. 48 .

- ↑ Walter Bührer: "At the beginning ..." Investigations on the genesis of the text and on the relative-chronological classification of genes 1–3 . Göttingen 2011, p. 123 .

- ↑ Alexandra Grund: The Origin of the Sabbath: Its Significance for Israel's Concept of Time and Culture of Remembrance . In: Research on the Old Testament . tape 75 . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-16-150221-7 , p. 298 .

- ↑ Erich Zenger: God's bow in the clouds, investigations into the composition and theology of priestly priestly prehistory . Stuttgart 1983, p. 171 .

- ^ Benno Jacob: The book of Genesis . Berlin 1934, p. 67 .

- ↑ Andreas Schüle: The prologue of the Hebrew Bible. The literary and theological history discourse of prehistory (Gen 1–11) . Zurich 2006, p. 83 .

- ↑ Erich Zenger: God's bow in the clouds, investigations into the composition and theology of priestly priestly prehistory . Stuttgart 1983, p. 172 .

- ↑ Jan Christian Gertz: The first book of Mose (Genesis). The prehistory Gen 1–11 . Göttingen 2018, p. 76 .