Germanic creation story

The Germanic creation story encompasses the myths of Germanic peoples that tell of how the world ( cosmogony ) and man ( anthropogony ) came about.

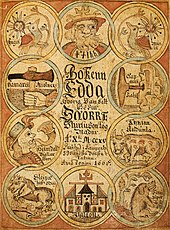

Germanic creation myths have largely only survived through the medieval Edda literature of the Icelanders . This does not reproduce the myths from ancient Germanic times, but rather the western Norse myths of the Middle Ages, after they were edited and written down by poets ( skalds ). Thus the creation myths of the Edda literature represent only the end point of the development of the western Nordic branch of the North Germanic peoples. Apart from a few remains, the remaining traditions of the Germanic peoples have been lost.

With the help of all available testimonies, linguistic studies and the comparison with the creation myths of other, especially Indo-European peoples, parts of the existing tradition can be traced back to myths with different degrees of probability that date back to the ancient Germanic era. The Germanic creation myths can no longer be restored as a unified whole in this way. Overall, the picture is confusing, as the existing sources show that the surviving tradition contains the most varied stages of development over several thousand years from pre-Indo-European to medieval times, the creation myths of which never formed a unity, neither in primitive Germanic nor in western Nordic times.

Source overview

Nordic tradition

→ See also: Edda

The literature of the Edda is the richest source of West Norse creation myths, which have already been influenced to varying degrees by medieval and Christian ideas.

Creation myths are contained in the songs of gods in the songs-Edda Vǫluspá , Grímnismál , Vafþrúðnismál and Hyndlulióð . They are predominantly the work of poets who have worked on the existing tradition, but are still able to reproduce it authentically. The cosmogonic and anthropogonic contents originate almost without exception from pre-Christian times, in the case of Iceland from before 1000. Christian colors to a small extent cannot, however, be excluded.

The Vǫluspá occupies an exceptional position among these songs. It is the only song that has the character of a hymn of creation and spans a narrative arc from prehistory and creation to the end of the world. It is preserved in three inconsistent writings from the 13th century: on the one hand in complete versions in the manuscript collections of the Codex Regius and the Hauksbók , on the other hand in excerpts from quotations in the Prose Edda . Until then, the content had apparently been delivered orally, possibly on the basis of an older written template.

Snorri Sturluson did not take an overall view of the West Nordic creation tradition in his work Prosa-Edda until the 13th century , when the pagan belief was no longer alive and its myths and customs were only cultivated as a cultural heritage out of a sense of tradition. The Prose Edda is based on the hymns of the gods in the Song Edda , especially the Vǫluspá , but also draws from sources that are no longer preserved. It is much more influenced by medieval Christian thinking than the songs of the gods and tries to harmonize the pagan myths with one another, but also with Christianity. Old and new ideas flow together indiscriminately to form a unity that as such did not even exist among the Icelanders. The Prose Edda has shaped the understanding of the creation myths to this day, because it subordinates itself to the clear structure of the Vǫluspá and nevertheless gives the impression of superior knowledge through the connections it makes to the other songs of the gods and through the illumination of many dark parts of the songs awakened. With his harmonization work and additions, however, Snorri Sturluson ultimately made a number of interventions in the myths and apparently no longer understood all the contents of them himself. That is why it is better not to see it as a more authentic rendering of the western Nordic tradition, but to understand it as the last and, above all, independent development stage of the creation myths.

References to creation myths may be found in the song of the gods Rígs Edula , which does not belong to the Edda Song and dates from the 13th century, as well as the scald poetry from the 9th century. The tradition of the creation myths from the east of the north has been almost completely lost.

West and East Germanic tradition

The West Germanic tradition of the creation story is essentially only preserved in two remains. On the one hand in the Christian Wessobrunn prayer around 790, on the other hand through brief remarks by Tacitus in his 98 work Germania . The creation myths of the East Germans , on the other hand, have disappeared without a trace, apart from a remark in Jordanes ' work Getica from the 6th century, which is difficult to interpret .

Creation myths according to the sources

Icelandic songs of the gods

Vǫluspá

Before the world was created, there was nothing but the Ginnungagap where the first being named Ymir lived. Then Bur's sons raised the bare earth, in which the world tree Yggdrasil was already germinating, and created Midgard ( Miðgarðr ) on the earth. The sun, moon and the stars came into being, and although the heavenly lights had not yet taken their place, the sunshine let the first grass grow out of the earth. When the gods named night, new moon, morning, noon, afternoon and evening so that the time could be counted, they met at their meeting place Idafeld ( Iðawǫll ), built altars and temples, forged tools, lived in the riches of their gold and were driven away the time playing the board game until three mighty giant daughters came. The gods then discussed who should create the dwarves from Brimir's blood and Bláinn's bones (probably Ymir), which were then created next. On the beach the three gods Odin , Hœnir and Loðurr found Askr and Embla , lifeless and fateless, and created the people whose fate the three Norns from the Urðr source under Yggdrasil determine. In addition, a myth of human origin is perhaps hinted at, because in the Codex Regius version the people are referred to as Heimdallr's sons at the beginning of the song .

Vafþrúðnismál

Even before the world was created, according to the Vafþrúðnismál, the giant Aurgelmir was formed from the pus drops of the Élivagár . Under his arm grew a girl and a boy, and by clapping their feet together he created a son of six. So he fathered the giant Thrudgelmir ( Þhrudgelmir ), who in turn produced the oldest living relatives of Ymir and the Aesir, the giant Bergelmir . It remains unclear whether Aurgelmir is just another name for Ymir, or whether it comes from an independent creation tradition. It is still said of the giant Bergelmir that it was placed on a lúðr (a word that is difficult to interpret). For what purpose is not mentioned.

The song also describes how the world was formed from the individual body parts of Ymir. Out of his flesh came the earth, out of the bones the mountains, out of the skull the sky, out of the blood the sea. It remains unspoken who created the world.

More testimonials

The Grímnismál also reproduces this myth of the creation of the world . However, it adds that from Ymir's hair the trees, from the brain the clouds and from the eyelashes Midgard (Miðgarðr), the world of men was created - by the gods.

According to the Hyndlulióð , one of the sons of Burr was the Asen god Odin . In addition, it is stated that all giants are descended from Ymir.

The Rígsþula describes how the estate of the servant, the peasant and the nobleman came about through the work of the god Ríg (Heimdallr).

Prose Edda

In the Prose Edda the scattered creation accounts of the Song Edda are summarized. Dark or inconsistent parts of the song Edda are harmonized or supplemented, further creation myths are added.

The Prose Edda begins the account of creation with a quotation from Vǫluspá , after which at the beginning there was only nothing in the form of the Ginnungagap. In contradiction to this, she then describes the Ginnungagap as a ravine that lay between two worlds that were older than the rift between them. In the south there was the fire world Muspellsheim and in the north the cold water and ice world Niflheim with the spring Hvergelmir . The poisonous water that fed the primeval river Élivágar poured from the spring. Their waters flowed towards Ginnungagap until they froze to ice. The poison that sprayed from them struck the northern part of the trench as frost, while the sparks of Muspellsheim flew into the southern part. It was only mild in the middle of the ditch. There the hot air from the south and the frost from the north met, so that the frost thawed. From these drops of spray arose the first being in human form called Ymir, which the frost giants call Aurgelmir. Aurgelmir sweated a man and a woman under his left arm and by clapping his feet he fathered a son, from whom the frost giants descended.

As the frost in Ginnungagap thawed further, the cow Auðhumla came out. Four streams of milk flowed from her udder, with which she nourished Ymir. Auðhumla, on the other hand, licked the salt from the frosted stones. Within three days she licked a human-like being named Búri free. He had a son named Borr who fathered the three sons Odin, Vili and Vé with Bestla . Borr's sons killed Ymir and took him to the Ginnungagap to create the world out of his body. The blood flowing out of it drowned all frost giants, except for Bergelmir, who was able to save himself with his wife in a lúðr .

Then the gold age dawned. The gods enjoyed themselves on the Ida field (Iðavǫllr) until the women came from Riesenheim and spoiled everything. As a result, the gods issued the laws and created the dwarves. In contrast to Vǫluspá , Odin, Vili and Vé found two unnamed tree trunks on the beach. They gave them their names, Askr and Embla, and made them people whose fate the Norns determine.

Other tradition

The Wessobrunn prayer uses a number of formulas to describe the prehistoric times, when nothing existed, that resemble those of the Vǫluspá .

Midgard, Old Norse miðgarðr, is used as a name for the earthly world in Gothic as midjungards, in Old English as middangeard, in Old Saxon as middilgard and in Old High German as mittigart. From the East Nordic tradition, the Swedish word Ghinmendegop has been preserved for a huge, bottomless abyss, which corresponds to the West Nordic Ginnungagap.

Tacitus has a lineage myth. According to this, the Teutons worshiped a god named Tuisto , who grew out of the earth or was born. His son Mannus had three sons, after whose names the three tribal associations of the Teutons named themselves and from whom they derived their descent. In addition, Tacitus' obscure description of the sacred grove of the Semnones could include creation myths in two ways. It is said that the Semnones originated from this grove. Furthermore, one could see the ritual repetition of the mythical dismemberment of Ymir in the ritual human sacrifice.

The Getica contains a dark place in which the Ostrogoths deified their victorious military leaders and called them Ansis. One of those heroes by the name of Gapt was regarded as the progenitor of the Ostrogothic royal family of the Amaler . Possibly this tradition goes back to a myth of the Goths, which derived their descent from the god Gaut .

The individual creation myths

→ See also: Nordic mythology and Germanic mythology

Creation myths reflect people, their culture and their understanding of how the world works. The social, religious and technical achievements receive a justification and an affirmation through them. In ancient times these myths were considered true stories, and for many indigenous peoples the prehistoric processes described had to be repeated and renewed in cult to preserve the world and life. Nevertheless, research is still unable to interpret the traditional Germanic creation myths in such a context as a meaningful whole.

The prehistory

The descriptions of prehistoric times contain the ideas about what was in prehistoric times before the existing world (and thus space and time) were created.

When there was nothing

The creation account of the Nordic Vǫluspá begins in the third stanza with these verses, which tell of the beginning of times when nothing was:

|

|

That the poet of the Vǫluspá did not invent it freely is shown by verses of the Christian Wessobrunn prayer , which was written about 200 years earlier 2,500 kilometers away in the West Germanic area.

|

|

Since Jacob Grimm's time, nobody seriously doubts that both texts draw from a common older legacy. But despite the common formula earth and heaven and the comparable formulas of negation, it is only probable, but not certain, that they go back to an ancient Germanic creation song that was performed in song form. Tacitus already mentions the song as the bearer of the myths.

|

|

Archaic formulas

The old age of these verses confirms the ancient formula "when nothing was, neither earth nor heaven," which both poets used.

The formula "Earth and Heaven" is attested several times in the Germanic world in the period from the 8th to the 13th century. Christian origin seems to be ruled out, as the corresponding Christian formula is always oppositely "heaven and earth". The formula therefore certainly comes from ancient Germanic times. Aufhimmel means neither a special heaven like the Christian seventh heaven , nor does the word come from the everyday language of that time. The puzzling prefix auf is explained by the necessity of the alliteration . Since the first letters of "earth and heaven" are not consonantic with each other, a prefix starting with a vowel was apparently added to the word heaven in order to form a vowel rhyme. This pair of terms was used to express the totality of the universe. It corresponds to our current term “the world”.

The researchers disagree about whether the formula “when nothing was” also belonged to the Germanic common property. The formula is only supported by a quote from Vǫluspá in the Prose Edda . In the manuscript collections Codex Regius and Hauksbók it says “when Ymir lived” instead. Since both main sources of the Vǫluspá pass on the Ymir variant, some researchers say that it is also the more original. However, because of the parallels in the Wessobrunn prayer and the creation stories of the Indo-European peoples , the majority of them assume that the Prose Edda reflects the older tradition.

It is possible that the entire formula “when nothing was, neither earth nor heaven” goes back to Indo-European times. Parallels can be found in the creation accounts of ancient Iran, the Bundahishn and India, the Rigveda , which originated around 1200 BC.

|

|

Even with the ancient Greeks, the formula is echoed in a comedy by Aristophanes 414 BC, which perhaps refers to an old cosmogonic idea:

"Only Chaos and Night and Erebus was at first,

and Tartarus abyss;

Not earth, nor air, nor sky either. "

The idea of nothing

The many negative formulas, which everything was not, express that in the beginning there was only empty primal space, nothing. The Vǫluspá calls it the gap ginnunga . Snorri Sturluson understood it to mean a ravine, based on the medieval literal meaning of the word gap 'gorge, abyss', which he placed absurdly to the nothing described in the Vǫluspá between two worlds that should also be older than the gorge. Correspondingly, in older research and in some cases to this day, Ginnungagap was interpreted as a 'yawning throat' ( Eugen Mogk ).

However, Jan de Vries understood Ginnungagap, based on the linguistically closer Old Norse ginn, as 'the primal space filled with magical powers'. Accordingly, at the beginning there was a void that did not contain anything material, but which was already filled with the mysterious, invisible forces that would later generate life. This is comparable to the ancient ideas of chaos , prima materia and prima potentia .

Here, too, there are parallels in the creation myths of the Iranians and Indians, which point to a possible common Indo-European heritage. For the presentation of the empty space of the used Rigveda gahanam gabhiram , deep abyss'. The Bundahishn uses tuhigih 'emptiness, empty space' in a comparable place .

Common to these myths is the old idea that being emerges from non-being.

|

|

The emergence of the first being

The description that Ymir is a product of the elements fire and ice, of warmth and cold, can only be found in the Prose Edda . In the Poetic Edda it says this in the song vafþrúðnismál only that originated in primitive times the giant Aurgelmir when injected from the élivágar pus drops as long grew until it became a giant. Tacitus' remark that Tuisto was born out of the earth may also make a statement about the origin of the first being.

Ymir, Old Norse for ' noisy ', comes from Indo-European * i̯̯̯emo- 'twin'. Since the giant creates beings of itself without a partner, its name is ultimately interpreted as 'twin, hermaphrodite'. Prehistoric dual-sex beings are known from many cultures. It is certain that Ymir was already a mythical figure in Indo-European times, because the names of some mythical beings from the Indo-European world are linguistically related to him. According to the Indian Rigveda , Yama was the first person and, together with his twin sister Yami, fathered the first people before he went to the underworld as a judge over the dead. The Iranian Yima in Bundahishn is the ruler of the primeval times of paradise. Among the Latvians, Jumis is a name both for the twin fruit (a nut with two kernels) and for a grain demon, which, depending on the source, is described as a hermaphrodite, man or woman. These parallels show that they are purely linguistic, but not content-related. This means that the Eddic Ymir myths do not necessarily have to have Indo-European origins.

Like Ymir, Tuisto also has duality in its name. According to the prevailing opinion, the name comes from Indo-European * duis- 'twice'. Since Tacitus describes Tuisto as the divine father of the ancestral father of the Teutons, he is comparable to a first being, so that it is obvious that Ymir and Tuisto emerged from the same mythical figure. But there was no longer any identity between the two at the latest in Germanic times. Tuisto is a god and ancestor of humans, Ymir is a giant and ancestor of giants, but not of humans. The differences are so serious that some research also says that although both are based on Indo-European ideas, they do not go back to the same mythical figure.

Aurgelmir, the 'sand-born roar', is the ancient giant whom Snorri Sturluson equates with Ymir. It is quite possible that the myth of Aurgelmir stems from an independent tradition of creation, but research mainly follows the equation with Ymir for reasons of content, since the myth described in Aurgelmir is comparable to the situation that one would expect in Ymir.

The myths about how the first being came into the world are correspondingly inconsistent.

- Ymir: from the polarity of fire and ice

The seemingly alchemical description of the prose Edda of the emergence of the first being out of fire and ice has a parallel in the Iranian Bundahishn, which speaks of the work of the good creator god Ohrmazd in the light of heights and of the evil creator god Ahreman , who works in the dark depths. The two spheres are separated by empty space, in which the world is, in which good and bad mix. There are similarities between Prosa-Edda and Bundahishn due to the pairs of opposites and the mixture of both forces in the empty space that lies between them. However, the contents are considered to be too far apart (fire - ice / good above - bad below), so that research negates a common Indo-European heritage.

An older Nordic or Germanic tradition cannot be ruled out with certainty, but research considers it more likely that the origin of Ymir from fire and ice goes back to a medieval speculation by Icelandic scholars or Snorri Sturlusons ( Elard Hugo Meyer , Franz Rolf Schröder ), which was perhaps indirectly influenced by Iranian dualism or arose from the medieval understanding of the ancient theory of the elements , and linked myths of the ice and fire worlds with the history of creation to a unity.

- Aurgelmir: from the pus drops of the Élivágar

After the song Vafþrúðnismál , the giant Aurgelmir formed from the pus drops (eitrdropar) of the Élivágar. The Élivágar are eleven prehistoric rivers in the Prose Edda that flow from the Hvergelmir spring. Snorri Sturluson took their names from the river catalog of the song Grímnismál .

In some research it is doubted that the Élivágar were originally thought of as rivers. Based on the etymology, Eyvind Fjeld Halvorsen sees the name as a paraphrase for the mythical primeval sea that surrounded the world. This interpretation suggests, however, to assign it to the myths of the water cosmogony (→ see section: World emergence from the primordial sea? ) .

Jan de Vries considers the basic idea of the myth, the emergence from pus drops, to be at least pagan-Germanic.

- Tuisto: from the earth

If you see the first being in Tuisto, Tacitus also makes a statement about its origin. He says that Tuisto is terra editum 'born or sprouted from the earth.' According to this description, the earth seems to have produced Tuisto asexually.

Here, however, research understands the earth partly as the personification of the earth, i.e. as mother earth . The Prose Edda contains a comparable myth , according to which the first cow Auðhumla nourished the giant Ymir (→ see section: The original cow Auðhumla ) . In many mythologies, cows are a mythical image for the earth mother. In comparison with the creation myths of primitive peoples, however, in order to be fertile, Mother Earth needs a male fertilizer, Father Heaven. Therefore it was assumed in older research that Tuisto was the son of the Germanic sky god * Tiwaz . An attempt was made to underpin this assumption etymologically. In some Germania manuscripts , 'Tuisco' is used instead of Tuisto. If you read this variant of the writing as an interrogation for Tiwisko, the meaning 'son of Tiwaz' emerges. Similarly, Norse mythology assumes a relationship between the sky god and the earth. Jǫrð , the Nordic personification of the earth, was considered to be the wife and daughter of Odin, who in his capacity as Allfather had ousted another heavenly deity, namely Tyr , who had emerged from the Germanic * Tiwaz. But Tuisto is better documented as a spelling and a prescription from Tuisto to Tuisco is more likely than the other way round, and moreover, according to recent research, Tuisco does not have a different name than Tuisto.

The creation of the giants

In the next step of the Germanic creation story, the giants emerged from the primordial being. The song Hyndlulióð says: “All the giants come from Ymir.” The appropriate myth comes from the song Vafþrúðnismál of the giant Aurgelmir, who, according to Prose Edda , is one with Ymir. As a result, a girl and a boy grew under Aurgelmir's arm, while by clapping his feet he produced a son of six. The Prose Edda adds that the giants only descended from that six-headed son, and is silent about what emerged from the man and the woman.

In research, one follows predominantly the equation of Snorri Sturluson of Aurgelmir with Ymir (see above). There is also nothing to prevent the Nordic myth from having Germanic origins, in view of the many parallels in the world, in which the primordial being produces the giants before the gods.

The song Vafþrúðnismál also names a generation series of three prehistoric giants beginning with Aurgelmir-Ymir, whose son was called Þrúðgelmir , who in turn was the father of the giant Bergelmir , the oldest living giant. It limits the number of generations of the ancient giants to three.

The origin of the gods

Within three days, according to Prose-Edda , the original cow Auðhumla licked Búri free with her tongue, who fathered a son named Borr , who in turn fathered three sons with his wife, the giantess Bestla : Odin , Vili and Vé .

The original cow Auðhumla

Auðhumla, literally 'polled wealth', obviously means a polled cow, as Tacitus testifies to the Teutons. Although it is only documented by the Prose Edda , research assumes that it is not an invention of Snorri Sturluson, but rather goes back to an old tradition that comes from either the Near Eastern or the Indo-European culture. The primordial cattle at the beginning of creation has numerous equivalents, as can be seen from comparisons with the Greek Hera 'the cow eye', the Egyptian Isis and also the Germanic Nerthus , whose cart is pulled by cows. The creation of búris by licking the salt is also an archaic trait, which is reflected in the belief of ancient peoples, according to which female beings become pregnant by licking the salt (Krappe). The original cow is a picture for mother earth, which stands for great fertility.

The image of the four streams of milk either belongs to the myth of the cosmic mountain of the world , from which four rivers flow in the four cardinal directions, or, as a Christian influence, it comes from the four streams of paradise in the Bible, which also flow in all four cardinal directions ( Gen 2: 10- 13 ELB ).

Búri, Burr and his three sons

According to the Prose Edda , Búri is the father of Borr, whose three sons are named Odin, Vili and Vé. The Vǫluspá only mentions Bur's sons without saying who they are. Odin as the son of Burr is also attested by the song Hyndlulióð . Despite the slightly different spellings, Bur, Burr, and Borr are the same person.

Since Búri is not mentioned in the Edda of Songs , there is a certain probability that it goes back to an invention of Snorri Sturluson. The Prose Edda describes a certain genealogical pattern here, father → son → three sons, which returns in Tacitus in the form of Tuisto → Mannus → three sons and for which there are many parallels in the non-Germanic world. It is also comparable that Mannus means 'man' and Burr means 'son'. Thus it should be certain that there was actually a father figure for Burr in Germanic mythology (→ see section: Tuisto, Mannus and his sons ).

It is more difficult to answer the question of whether Burr's father was actually called Búri. In research, doubts are rarely raised about this, in general one translates his name accordingly in the sense of the father role to Burr, so that Búri is reproduced as 'producer' and Burr as 'father'. However, it was also pointed out that both names basically mean the same thing, since they both derive from Germanic * búriz 'Born, Son'. If one continues the Tacitus parallel, then the actual producer Burrs would originally have been Ymir, but the character natures of Snorri Sturluson and Tacitus are too different to be assumed in western Nordic times. The Prose Edda describes a theogony, the Germania an ethnogony. The parallel is therefore only of a formal nature. It is therefore conceivable that the essential natures were reinterpreted in post-Germanic times, and that Ymir was no longer the producer, but not the role of father towards Burr, who therefore needed a new father.

The nature of Búris and Burr, the ancestors of the gods, cannot be clearly determined either. Because of Buris son descended the gods, is usually represented in the research, he also Asengott was. But because his son creates the gods together with the giantess Bestla, he can also be considered a giant. Búri is referred to as maðr in the Prose Edda . The old Norse word means 'man, man (as opposed to woman) or husband' and indicates at least a human figure of Búris or even a human nature corresponding to the primitive man Mannus.

It is possible that the gods were also seen as children of the earth mother in an older class of tradition. On the one hand, the mother of Odin and his two brothers, Bestla, as a giantess, is a chthonic being. Its name, which can be translated as 'the basty', also points to a tree nature and thus in the same direction. On the other hand, the Prose Edda lets Odin's grandfather Búri arise from a stone, which, like Tuisto, allows him to rise from the earth. Perhaps there is also a connection to the ancestral cult, since the stone is also an ancestral seat.

It is by no means certain that Burr's sons were actually called Odin, Vili and Vé, even if this trinity of names goes back to ancient Germanic times, as it contains an old allotment that only dissolved in Nordic times, when * Wodanaz became Odin. Because of the only trinity of gods that the Vǫluspá names in connection with the creation of mankind, it is conceivable that by the sons of Burrs they mean Odin, Hœnir and Loðurr.

The creation and establishment of the world

World emergence from Ymir's body

|

|

The emergence of the world from the body of the primordial being is not an invention of the Edda poets, but certainly belongs to Nordic mythology, as Kenningar von Skalds of the 10th and 11th centuries have come down to us, who assume the same statement.

Jacob Grimm compared the Eddic creation of the world, among other things, with a myth in the apocryphal book of Enoch , which describes how Adam was formed from parts of the cosmos. From this, Elard Hugo Meyer concluded that there was a Christian influence, since the Eddic myth imitated the so-called Adam Apocryphal. However, it is an exactly opposite idea, which moreover does not reflect a popular view, but only a learned speculation (M. Förster).

The Nordic tale has many equivalents among the peoples of the world. The creation of the world from Ymir therefore does not necessarily have to represent fiefdom, and may have Indo-European origins. The Puruşa song in the Indian Rigveda also tells of the creation of the world from the body of a primordial being that was sacrificed by the gods, but there are only few similarities in the equations between body parts and world components. There is also a Manichean form of the myth in which the equations sky = skin, earth = meat, mountains = bones, plants = hair occur (Schkand-Gumanig-Vizar) , as well as another parallel in the Bundahishn .

The separation of the one that arose out of chaos into the many parts of the world is usually understood in myth as a sacrifice or a suicide of the primordial being. Some scholars, based on the Puruşa song, are of the opinion that the gods killed Ymir in order to make a ritual offering. Independently of this, the old idea that the macrocosm and microcosm correspond to one another is behind the construction of the world from the parts of the primordial being.

World emergence from the primordial sea

There is some evidence that the Vǫluspá tells of a different world creation than the songs Vafþrúðnismál and Grímnismál . It is possible that Bur's sons brought the earth from the depths of the ocean to the surface of the water, on which it has been floating ever since. The Vǫluspá does not express this clearly, but it does indicate it. In addition, this type of world creation would agree with other Eurasian and North American creation myths (Franz Rolf Schröder, Kurt Schier). The water cosmogony of the Vǫluspá is controversial in research. It is affirmed by some well-known researchers, but not by all.

The clearest hint is given in the end-time accounts of the Vǫluspá . After the great battle between the gods and their opponents, in which the existing world order threatened to perish, it is said:

|

|

This assumes that the earth came out of the water for the first time. However, since no verse in the Vǫluspá reports it clearly, it could perhaps have only been hinted at. A corresponding passage could be assumed in the prehistoric myths, since the end times in the myths often reflect the prehistoric times. There are actually a few dark verses there that you don't know what to do with:

|

|

From this it appears that Bur's sons raised land from the Ginnungagap, but not that they took it from the water, apart from the fact that Snorri Sturluson in his prose Edda undoubtedly understood the Ginnungagap as a gorge and not a sea. The creation of water becomes even more questionable because the Vǫluspá testifies to the existence of Ymir a few verses earlier: “It was prehistoric times when Ymir lived”, which gives the impression that she is alluding to the myth of the world originating from Ymir's body. On the other hand, it cannot be explained why Bur's sons had to dig the earth out of a ditch when they had created the world from the body of Ymir.

These contradictions cannot be resolved with the sources available. It should be remembered that creation myths can go back thousands of years, can change over time, and can combine with competing creation myths.

It is quite possible that Ymir, for example, did not belong to the original tradition of the Vǫluspá , as there is an alternative tradition of the prose Edda at the only place in the creation song in which Ymir is mentioned : "It was prehistoric times when nothing was", which fits better with the myths of Indo-European peoples. It is just as possible that Ymir originally belonged to the creation story of the Vǫluspá , without its role in it being able to be determined.

The understanding of Snorri Sturluson, according to which Ginnungagap is a ravine, is apparently strongly influenced by the linguistic meaning of the word in its medieval period. This meaning does not have to be the meaning that the ginnungagap originally had. It is noticeable, for example, that in the texts and maps of the high medieval to modern Nordic cosmography, the Ginnungagap is a sea sound that represents, so to speak, the secular remnant of the mythical Ginnungagap. According to Jan de Vrie's interpretation, Ginnungagap does not mean a ravine anyway, but an emptiness that is filled with magical powers. A comparison with the creation myths of other peoples shows that primeval void and primeval sea are interchangeable terms for chaos. In addition, it would be unique among the myths of the world that the gods lift the earth out of a ditch, whereas there are countless myths in which the earth is brought from the depths of an ancient sea, especially in the Eurasian-North American region, but also in Rigveda and in Babylonian-Akkadian myths.

The many negation formulas, which were not all in the beginning in prehistoric times, in particular the formula that heaven and earth were not yet, can be found not only in the Germanic creation story, but in particular also in Eurasian water cosmogonies, which report that diving water birds die Get earth from the depths of the sea. The diving birds are themselves only helper figures of a theriomorphic creator god who originally lifted the earth from the depths alone. Accordingly, the three gods, Burs sons, will have been animal helper figures of the creator god in older times.

What animal shape they originally had is no longer recognizable in Nordic mythology. The few traces that exist in the creation myths lead to swans or seals.

Swans come into question because, according to the Prose Edda , they swim in the source of the Urðr on the World Tree. In research, the name Hœnirs is partly interpreted as a swan.

The fragmentary preserved Húsdrápa of the skald Úlfr Uggason, however, has a mythical fragment in which the gods Heimdallr and Loki fight each other in the form of a seal:

|

|

This verse is also dark. There are plenty of interpretations and translation suggestions for it, as it is difficult to understand linguistically and in terms of content. In the torn myth, one can see another myth of the creation of the earth out of the water, or even a formation of the water creation of the Vǫluspá , if one understands it in such a way that Loki wanted to keep a piece of earth to himself when lifting the earth from the seabed, which Heimdallr wanted him to do in battle escaped. There are parallels here in other creation stories as well. The Singasteinn could be the place of the fight, but also the piece of earth that was fought for. However, the interpretation suffers from the fact that it has no clue whether there was a third deity in this myth, so that it can be considered a continuation of the myth of the elevation of the earth by the trinity of the sons of Bur.

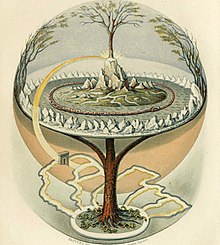

In all types of water cosmogonies, a tree grows in the middle of the primeval sea, which is both the center of the world and at the same time the totality of the world. Comparable to this is the world tree, from whose foot all the rivers of the world emanate. The sea here can be a lake or just a spring. This corresponds to the descriptions of the Germanic world tree Yggdrasil. There is also a dark reference to this in the Vǫluspá :

|

|

One can read the passage in such a way that the World Tree germinated in prehistoric times in an earth that was then still under water. The source on the World Tree can also be seen in the same context: the Urðr spring, the Hvergelmir spring, from which all rivers flow into the sea, and also the Élivagár are ultimately all part of the water cosmogony. The creation of the first humans from wood also belongs to this circle of myths, since this myth is in the same narrative stream of the Vǫluspá .

The myths of water cosmogony are very old and probably originate from the pre-Indo-European times of nomadic or hunter cultures. Obviously, the V derluspá poet was able to access very old material which he reproduced quite faithfully. Apparently, Snorri Sturluson could no longer do anything with a water cosmogony, which is proven by the fact that he did not take over exactly those parts of the Vǫluspá , although it is the work on which he relies most.

The downfall of the ancient giants

The sea was made of Ymir's blood. But according to the Prose Edda , so much blood gushed from Ymir's wounds that the ancient giants drowned. Only the giant Bergelmir was able to save himself with his wife, since he found refuge in a lúðr . Snorri Sturluson also quotes verses from the Vafþrúðnismál , which only prove that Bergelmir was a prehistoric giant and was placed on the said lúðr without the song making any reference to a flood.

In research, considerable reservations are raised about recognizing the Flood of the Prose Edda as an original part of the Germanic creation story. Neither the song Vafþrúðnismál presupposes a flood, nor are there any other references to a flood in Germanic mythology, so that Christian influence through the biblical flood ( Gen 7: 1-24 LUT ) is possible. The lúðr on which Bergelmir is placed cannot be precisely determined either. Old Norse lúðr can mean 'hollow trunk, vessel, grinding box of the millstone, cradle, ship or war horn' without having any clues as to what the song meant.

Jan de Vries assumed that the Christian Snorri Sturluson expected a flood myth in his native mythology and understood the Vafþrúðnismál accordingly. That is why he interpreted lúðr in the sense of 'cradle' as an image for Bergelmir as the progenitor of the frost giants.

However, many creation myths around the world know the motive that the primeval world is destroyed by a catastrophe. In ¾ all cases by a flood, be it due to dissatisfaction of the Creator with his work or because the creatures rebel against their Creator or for no reason. Therefore, despite the proximity to the biblical flood, it is not imperative to conclude that the Prose Edda is a Christian fief . According to Gabriel Turville-Petre, there are also significant differences between the two floods. The Germanic flood arose before the world was created and is directly related to it, while the biblical flood took place afterwards. The Germanic deluge destroys all giants, the biblical all people. And while the one proceeded from the blood of Ymir, the other proceeded from water.

In these deluge myths, it is also not uncommon for survivors to use unusual items for their salvation. So one interprets lúðr as a 'grinding box' or just profane as a 'raft'.

Ultimately, based on the sources, it cannot be decided whether the Germanic Flood story represents an approximation of the Prose Edda to Christianity or whether it is based on an authentic Germanic tradition.

The order of the world

According to the Vǫluspá , after creation , the sun shone on the stones of the earth and let the first grass ( laukr , actually 'leek') grow. But the sun, moon and stars did not yet know where they belonged. So the gods together gave their names to the night and the times of day so that the time could be counted. It is not stated, but obviously presupposed, that the gods assigned their orbits to the stars.

The Prose Edda does not deal with the bestowal of names, but expresses that the gods determined the career paths of the stars and that thereby the year counting was arranged. In addition, she describes how the gods continued their creative work. The circular earth was therefore surrounded by the sea all around, and the giants were assigned the beaches as their place of residence. Then they created a sheltered place in the middle of the earth called Midgard (Miðgarðr), which they later allocated to the people. They built a castle for themselves over it called Ásgarðr . They connected both worlds with the Bifrǫst rainbow bridge .

Of these myths, only the term Midgard 'the middle enclosure' is certainly a part of the ancient Germanic world of ideas. Only this word has equivalents in other Germanic languages.

The gold age

When the gods had finished their work, according to Vǫluspá , they met at their meeting place Idafeld ( Iðawǫll ). There they built an altar, a temple ( hǫrgr ok hof hátimbráðr , but only handed down in the Codex Regius version) and a forge in which they made tools. They were carefree, had lots of gold and passed their time playing board games until three giant daughters paid them a visit. The gods then resumed the process of creation and created the dwarf people . The Prose Edda repeats and elaborates on many of the statements in the V führtluspá . She calls this time the gullaldr ' gold age '. Notwithstanding, she explains that the gods a first courtyard , courtyard 'built for their twelve seats and one for the goddesses hǫrgr , temples' called Wingolf . When the women came from Riesenheim and spoiled everything, the gods first created the laws and then the dwarves.

This enigmatic period of the Germanic creation story is only attested by the Edda literature. Recent research does not, or only marginally, deal with its position in the creation myths and its authenticity in the summaries of the history of creation. In older research, Jakob Grimm, for example, discusses connections to the doctrine of the world ages in Greek mythology and Karl Joseph Simrock interprets the gold age as a timeless and goldless phase of innocence that ends with the discovery of material gold, as it leads to greed for metal comes into the world and the work of time begins. Both make the Nordic gold age the lost paradise of the past.

The idea of a golden age as a lost prehistoric state of paradise is one of many creation myths in the world. As a rule, the beings of that time live forever in these myths, since neither illness, discord nor death are known. Most of the time they don't have to work and still have plenty to eat. This state lasts until the beings of the golden age bring about their end by passing away or rebellion against the will of the Creator. Following this, beings become mortal and thus death enters creation.

Symbolism of cultural achievements in the Vǫluspá

In the depiction of the Vǫluspá , it is particularly emphasized that the world of gods reflects certain cultural achievements of the human world: the worship of higher powers, the thing , the blacksmithing, the game in the form of the board game and the reference to gold as something extremely valuable. Since the world of gods precedes that of humans in myth, it is expressed by the fact that the gods are the founders of culture.

Wrought

In ancient times, blacksmiths were held in high regard for their knowledge of metalworking, which also made the blacksmith and his art appear supernatural. They are generally considered to be the guardians of fire, but in Norse literature the blacksmith was also often used as a term for creator, forging and creating could be used synonymously. This idea was later even transferred to Christ , who is referred to as the sky smith in an Icelandic psalm. The Vǫluspá thus represents the gods as blacksmiths because they had created the world.

Board game

Which board game is meant in the V istluspá cannot be said. The song only mentions the material from which the teflðu “game boards” were made, namely gold. What was played ultimately remains open.

From the early to the high Middle Ages, two types of board games in the (North) Germanic region can be distinguished on the basis of archaeological finds in connection with sparse written evidence. On the one hand, a game of chance called Alea , which emerged from the Ludus Duodecim Scriptorum in the 4th century and is considered to be the forerunner of backgammon . On the other hand, the strategy game Hnefatafl , probably a successor to Ludus Latrunculorum , in which both players had a different number of game pieces and the numerically weaker party had to defend the so-called Königsstein. This game was superseded by the game of chess between the 10th and 12th centuries . Both games were found as grave supplements, the strategy game was in higher regard.

Jan de Vries understood the Vǫluspá board game as a ritual strategy game, which he thought of as a struggle between order and chaos, referring to statements from the Icelandic Hervarar saga , a reflection of the struggle that is constantly repeated in the world. In contrast, Hilda R. Ellis-Davidson decides to see the Vǫluspá board game as a game of chance with the dice, because it is an expression of the imponderables of the power of fate, which she believes only one verse later will dissuade the gods from playing . The game was also assigned to an Indo-European context, in which it was compared with the game in Rajasuya in India and understood accordingly as an ordering, destiny-determining power.

In the end, it may not matter what game the gods played, just that they played . Because as long as the gods can play and indulge in their innocent pleasures, peace and harmony prevail.

Altar and temple

The gods also erect a hǫrgr hátimbráðr 'high-timbered stone altar, sacrificial site' and a courtyard 'temple'. Hǫrgr is the name for a Germanic sacrificial altar that has been archaeologically documented as such since the Neolithic Age . The word may originally only have meant 'holy place'. A hǫrgr hátimbráðr thus indicates a wooden structure on or around a stone altar. However, even in late pagan times, temples are as good as not attested in the Germanic world.

Why the gods of all people erect the altar and temple is a mystery. From the Vǫluspá it can be seen in the inference process that there was the power of fate to which the gods were subject (→ see section: The power of fate ) , but in the absence of other indications a connection to the holy place of the gods remains a mere assumption.

The end of the gold age

The gold age ends when three women seek out the gods. What they are called and what exactly happens remains unsaid. The Vǫluspá describes them as ámátkar mjǫk 'very hideous' þursa meyjar ' Thursen girls' from jǫtunheimum 'Riesenheim'. The Prose Edda calls them the kvinnanna 'women' from Riesenheim who spoiled everything. Immediately afterwards (as a necessary measure?) The gods resume the creation process and create the dwarfs and then humans.

Thus it is a matter of a trinity of virgins who are either very ugly or overpowering, i.e. more powerful than the gods. The characterization as Thursen is also meaningful. In Edda literature, the primordial giants are invariably referred to as jǫtunn . That's one of several Nordic words for 'giant', but it's the only one that doesn't have a bad taste. In contrast, Thurse stands for a giant who is hostile to the gods (and thus to humans) and uses his powers and his magic to destroy them.

It does not seem to be an attack, but the word choice of the Vǫluspá alone expresses an intention of the three women against the gods, which destroyed the peace of the gods. It has been speculated that the three virgins brought greed for gold and thus strife and strife into the world, and this also refers to a parallel in the Iranian Bundahishn:

"[In the midst of divine peace, seductresses come and one of them, Jahi, says:] Rise up, father, because we want to start that quarrel, which is to be cornered by the Ohrmazd and the Amahrspanden and to have mischief!"

But from the context of the text of the Vǫluspá , one can also see the three Norns in them (→ see section: The power of fate ) . In the absence of other indications, the interpretations remain speculation.

The creation of the dwarves

→ See also: Dwarf and Dvergatal

After the Vǫluspá , the gods conferred about who should create the dwarf people from the blood and bones of Ymir. They created them in human form (mannlíkun) , dwarfs from earth (iǫrð) as the second created dwarf Durinn noticed. Who of the gods did it in the end, the Vǫluspá hides . The Prose Edda quotes part of the Vluspá passage, but provides a more detailed and somewhat different version. After that, the dwarfs were the first to come to life in the flesh of Ymir and lived as maggots. Only after the advice of the gods were they given human form and spirit and the interior of the earth and the rocks determined as their abode.

The importance of the dwarfs in the Germanic creation story is usually not mentioned in the synopsis of recent research on creation history. According to one opinion, the creation myth of the dwarfs in the Vǫluspá is based solely on the poet's imagination and not on popular beliefs. After all, like the giants, they are generally considered to be native inhabitants of the country (for example in the creation myth of the Strasbourg book of heroes ). Their distinguishing feature is that they live inside the earth and can therefore be viewed as earth or mountain spirits . One does not know how to interpret the word dwarf , one brings it in connection with Indo-European words, which point to 'deceit' or 'harmful being'. The dwarves' evil disposition was a primordial trait of their being, which got lost in medieval poetry and could be due to a mix-up with the albums . Some research suggests that the dwarves are remnants of Germanic ancestor worship . Although the traditions contain elements of a belief in the dead, the interpretation is controversial. Several dwarf names of the Vǫluspá in the so-called Dvergatal also suggest a connection between death and dwarf . The idea is not entirely remote, as the Germanic peoples buried their dead in clan graves that imitated the shape of a mountain ( death hill ). It is also controversial in research whether the dwarves made a contribution to the creation of humans by forming the human forms that the gods then animate.

The origin of the people

Two different mythical models have been handed down from the pagan-Germanic period that explain the origin of the human race. In one case, man is a creative work of the gods ( anthropogony ). In the other case the people of a certain ethnic group descend from a common divine or deified ancestor ( ethnogony ), so that these myths of ancestry also contain myths about the origin of humans.

Ancestry Myths

Tuisto, Mannus and his three sons

According to Tacitus Tuisto (→ see section: The origin of the first being ) and his son Mannus are the progenitors of the Teutons .

|

|

Mannus is referred to in the following as God (deo) , but this is likely to go back to an interpretation of Tacitus, since the name Mannus means 'man', which identifies him as a human being. Its name also suggests that the Germanic peoples only considered themselves (like many other peoples) to be human. The idea of ethnic togetherness based on common genealogical relationships is also found, for example, among the Greeks.

Like Tuisto, Mannus as a mythical figure certainly goes back to Indo-European times. In India the people are considered to be descendants of Manu , Sanskrit for 'man, human'. He was the original king and editor of the Manusmriti code of law . The Iranian mythology uses the phrase Manuš at one point . ciθra 'descended from Manuš' and thus testifies that once a progenitor named Manu was of great importance. The Lydians led by Herodotus their ancestry to the ancestor Manes back, who was their first king.

Basically, Tacitus describes the same development as the Prose Edda genealogy in the form of Búri → Burr → three sons . Tuisto arises first out of the earth asexually. Then, as his name suggests, by virtue of his dual gender character he begets Mannus, who in turn, through his human nature, is the first to reproduce sexually and in this way produces three sons.

The descent pattern of the double threesome appears several times in Germanic mythology.

| step | template | Germania | Vǫluspá | Prose Edda |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| father | A. | Tuisto | (Ymir?) | Buri |

| son | B. | Mannus | Bur | Burr |

| 3 sons | C D E | Ing (uo), Irmin (us), Ist (io) | Bur's sons (Odin, Hœnir and Loðurr or Odin, Vili, Vé?) | Odin, Vili, Vé |

It is a genealogical pattern that is also common among the Greeks, Persians, Babylonians and Phoenicians (C. Scott Littleton). But only among the Teutons are the names of the three sons in all of the allied rhymes.

Progenitor of the Semnones?

Furthermore, Tacitus could indicate a myth of the origin of the Semnones.

|

|

A lineage myth would exist if the deity worshiped in the grove were the ancestor of the Semnones. With that deity Woden / Odin seems to be meant.

Gaut - ancestor of the Goths?

Another myth of the descent of humans, more precisely the Goths, from a god could be contained in Jordanes' Getica .

|

|

The family tree, which Jordanes begins with Gapt, relates formally only to the Ostrogothic royal family of the Amaler , but the remark that the Goths raised their military leaders to demigods after a certain victorious battle, which they called Ansis (Gothic probably for Asen ), conclude that the progenitor and legend are derived from an ancient myth of ancestry of the Goths. Gapt, probably a spelling mistake for Gaut, is the Gothic equivalent of the Norse Odin's name Gautr 'Götländer'. But it was only the Scandinavians who equated the two, with the Goths Gaut was still an independent mythical figure. It is therefore possible that Gaut was considered the ancestor of the Goths.

Heimdallr's sons

The Vǫluspá in the version of the Codex Regius indicates a Nordic ethnogony , in which it describes the people as Heimdallr's sons (mǫgu Heimdallar) . This is joined by the medieval song Rígsþula , which describes a sociogony according to which the otherwise unknown god Ríg 'king' is the origin of the three classes of servant, farmer and nobility, whereby the probably more recent prose introduction of the song expressly equates Ríg with Heimdallr.

Georges Dumézil saw in this sociogony the Nordic echo of the social order of Indo-European times, but Klaus von See conclusively stated that the Rígsþula reflects the social conditions of the first half of the 13th century in Norway , which had not even existed in the Viking Age. Thus, it is not an old myth with Celtic echoes, but the art myth (comparable to an art fairy tale) of an unknown scholar of the 13th century who either pursued the goal of explaining the God-willed origin of the estates ( Andreas Heusler ) or cultic knowledge on the subject of how the sacred kingdom passes from one king to his successor (Jere Fleck). The subsequent equation of Ríg with Heimdallr is also questionable, since Ríg passes on the runic knowledge in the song, which points more to Odin than Heimdallr. Nevertheless, the introductions of the Rígsþula and the Vǫluspá seem to presuppose a relationship of descent between Heimdallr and humans, which remains obscure in the absence of other sources.

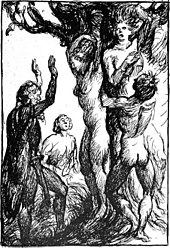

The creation myth of Askr and Embla

The Vǫluspá tells that the gods Odin, Hœnir and Loðurr found Askr and Embla on the beach, who had little strength and were still without fate (ørlǫg) . From this they created people by providing them with breath, spirit, warmth or blood (lá) and a divine or good appearance. But the fate of the people is assigned to the Norns. The Prose Edda, on the other hand, contradicts the Vǫluspá several times. After her, Burr's sons, Odin, Vili and Vé, met two tree trunks (tré) on the beach that did not yet have names. Only the gods gave them their names and made them human. It is true that Snorri Sturluson also lets the Norns determine the fate of the people, but they are previously appointed as rulers of destiny by the All-Father Odin.

Askr means 'ash', Embla perhaps 'elm' ( Sophus Bugge ), but rather 'creeper' ( Hans Sperber ). The myth not only says that humans descend from trees, but it also contains a very old mythical image that understands fire-making as a sexual act, because it includes the idea of how a drill made of hard ash wood rubs itself into softer wood until a spark is created ( Adalbert Kuhn ).

Older research saw this myth influenced by Christianity because of the equality of the initial letters to Adam and Eve , as well as the medieval interpretation of Christian teaching that the first humans were created by the Trinity . The name of Askr goes back to at least ancient Germanic times because of the linguistic relationship to Aesc , the progenitor of the royal family of the Aescingar. The fact that Embla is difficult to translate also indicates that her name is very old. If Embla actually means 'creeper', the pair of names Askr and Embla would certainly come from Indo-European times. The idea that people come down from trees is just as old and possibly goes back to an Indo-European myth. According to Hesiod , the people of the third age were descended from the ash trees. Ash people are also related to fire. In Iranian mythology, Mahle and Mahliyane grew up out of the earth, connected by a stem and 15 leaves.

Within the Eddic literature, the gods that the Vǫluspà calls are probably from an older tradition. It was certainly assumed that Snorri Sturluson was resorting to a different tradition ( Eugen Mogk ), but the exchange of the trinity results from the narrative context of the Prose Edda ( Sigurdur Nordal ). Obviously, in drafting the Prose Edda , Snorri Sturluson resorted to the sons of Burr in the creation of the world in order to harmonize the two myths. Why Hœnir and Loðurr were chosen, alongside Odin, to make people out of wood is no longer comprehensible, since no clear picture can be obtained of both deities. In research (as in the western Nordic literature before) Loðurr is mostly equated with Loki .

After a proposal that was as interesting as it was controversial by Gro Steinsland , it led to the Incarnation also ultimately taking place in three stages. Ultimately, the correctness of this concept cannot be proven, but it is within the scope of the sources, because the Vǫluspá indicates these three characteristics before the Incarnation: The gods found three forms that were without human life and still without fate.

| phase | Acting power | activity |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dwarfs | Making the human forms |

| 2 | Gods | Revitalization of the people |

| 3 | Norns | Determination of human destinies |

Creation or descent?

The myth of descent is incompatible with the myth of creation. Either humans are genetic descendants of the gods or the gods created them. Because of the clear parallels to mythologies of Indo-European peoples and a large number of ethnographies of Germanic tribes and royal families, some of the research assumes that the descent of humans from the gods is the more original myth, and leads the creation myth of the human couple through a triad of gods to either the Influence of southeastern ideas or assumes that the Germanic peoples did not have a common human genesis myth. Strictly speaking, however, one can only say today that both myths are based on Indo-European ideas without it being known how they coexisted.

The power of fate

The Vǫluspá shows in several places that, besides the gods, another power takes up its work, namely the power of fate . When Askr and Embla were still wood and not yet human, they were still fateless (ørlǫglausa) . The gods created the first humans out of the two woods, but the Norns assigned them their fate . Your task was to determine what life a person will lead and what fate (ørlǫg) overtakes him. They are described as three girls (meyjar) , i.e. virgins, whose home is the source of the Urðr on the world tree Yggdrasil. Their names are Urðr 'fate, death', literally 'that which has become', Verðandi ' that which is becoming' and Skuld ' that which should'. Outside of the creation story, the Vǫluspá poet uses the term ragnarǫk for the end times events in which the ancient gods perish in battle. Ragnarǫk literally means 'fate of the gods'. When that time comes, it is mjǫtuðr kyndisk 'fate is on fire '. In this way, the Vǫluspá integrates essential Nordic concepts of fate such as mjǫtuðr , ørlǫg and urðr in the course of world events it tells.

The Vǫluspá apparently assumes a power of fate that stands above everything and belongs to a higher order. Not only are humans given a destiny and a fate, but the gods also have a fateful predestination which they cannot change and which is ultimately fulfilled. In conclusion, it follows from this that the power of fate is more powerful than their own power and they are subject to it. This power of fate is personified in the Vǫluspá by the three Norns Urðr, Verðandi and Skuld.

The names of the three Norns probably come from medieval times. Verðandi is otherwise not recorded in western Nordic literature, Skuld only as the name of a Valkyrie . The Norn name Urðr, which is still considered to be an old name in science, is no older than the names of the other two Norns. Your name appears mostly in connection with the source U rðrbrunnr and this is called more often than the Norn, so that the name of the well apparently passed on to the Norn. Accordingly, the name of the fountain could be translated as u rðrbrunnr 'source of fate'. The naming concept of the three Norns probably comes from comparable medieval past-present-future concepts of the three moiren or parzen .

Nonetheless, the three virgins at the source of fate seem to come from ancient times, since the conceptual complex of three fateful women is not only very widespread in western Nordic folk tradition. As a result, the names of the Norns are very young, but their trinity and their tasks can be based on older ideas.

The power of fate in the form of the three Norns in the Vǫluspá includes the mythical image of the source of fate on the world tree, as well as the world tree itself, because like the Norns, it belongs to an order that is withdrawn from the work of the gods, and therefore the sphere of the power of fate can be assigned. Because the world tree germinates before the creation under the earth and it survives the end times events of the Ragnarǫk. Perhaps it is no coincidence that the Vǫluspá calls the world tree in their introduction (mjǫtvið) , the ' measurement tree '. The Nordic term mj ‚ tuðr , which actually means “the one to be measured ”, also begins with mjǫt 'measure' .

It is surprising that the Vǫluspá does not describe a direct encounter between the gods who create the world and the Norns who determine their fate and impose their will on them, and does not say anything about how the two powers relate to one another. The only place in the creation story of the Vǫluspá that could allude to it are those dark verses in which three Thursdays from Riesenheim conjure up the end of the golden age. Like the Norns, these are also called virgins, they too form a trinity and they too determine the course of things and yet it is strange that they call the Vǫluspá Thursen, evil, malevolent giantesses. The religious concept of three holy women , which is not limited to the Nordic world, identifies them predominantly as protective, charitable and maternal. But maybe they have a light and a dark side, just as life comes out of the earth and eventually goes back into it.

All father

The Christian influences on the Eddata texts are often seen as a falsification of pagan myths. This overlooks the fact that myths can only survive if they adapt to the new prevailing currents of thought. Perhaps the Christian Snorri Sturluson did just that when he wrote his Prose Edda . So he introduced a figure into the Germanic creation story who clearly has a Christian character and harmonizes the supreme pagan god Odin as the all-father with the Christian god. The figure of this Christian all-father is the youngest layer of Germanic cosmogony.

Accordingly, Allfather created heaven, earth and air and everything that goes with them. He is the oldest of the gods, lives for all time and effects all things, big and small. Twelve of the names he bore in ancient Asgard are mentioned, but it is Odin they mean. He also created man and gave him his immortal soul (ǫnd) . The person who lives according to the right custom will come to Allfather after death in Gimle , while the wicked go to Hel , which is by no means to be equated with the Christian hell, since there is no torture and horror of the Christian hell in Hel. Odin and his two brothers will be the rulers of heaven and earth.

literature

In the order of the year of publication.

- Jan de Vries: Old Germanic history of religion. Volume 2: Religion of the North Germans. Verlag Walter de Gruyter & Co., Berlin / Leipzig 1937.

- René LM Derolez: De Godsdienst der Teutons. 1959 (German gods and myths of the Teutons, translated by Julie von Wattenwyl, Verlag Suchier & Englisch, 1974, OCLC 256147286 )

- Kurt Schier: The creation of the earth from the primordial sea and the cosmogony of the Völospá. In: Hugo Kuhn, Kurt Schier (Ed.): Fairy tales, myths, poetry. - Festschrift for Friedrich von der Leyen's 90th birthday on August 19, 1963. Beck Verlag, Munich 1963, pp. 303–334.

- Gerd Wolfgang Weber: Wyrd - studies on the concept of fate of the Old English and Old Norse nature. Publishing house Gehlen, Bad Homburg / Berlin / Zurich 1969.

- Åke Viktor Ström, Haralds Biezais : Germanic and Baltic religion. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart 1975, ISBN 3-17-001157-X .

- Hilda Roderick Ellis-Davidson: Pagan Europe - Early Scandinavian and Celtic Religions. Manchester University Press, 1988, ISBN 0-7190-2579-6 ( excerpts online ).

- Gerhard Perl: Tacitus - Germania. In: Joachim Herrmann (Ed.): Greek and Latin sources on the early history of Central Europe. Second part, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-05-000571-8 .

- Heinrich Beck: Earth. In: Heinrich Beck, Dieter Geuenich, Heiko Steuer (Hrsg.): Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Volume 7, 2nd edition. Verlag Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1989, ISBN 3-11-011445-3 .

- Hermann Reichert: Mythical Names. In: Heinrich Beck, Dieter Geuenich, Heiko Steuer (Hrsg.): Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Volume 20, 2nd edition. Verlag Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2002, ISBN 3-11-017164-3 .

- Bernhard Maier : The religion of the Teutons - gods, myths, worldview. Verlag Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-50280-6 .

- Anders Hultgård: Creation myths In: Heinrich Beck, Dieter Geuenich, Heiko Steuer (Hrsg.): Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Volume 27, 2nd edition. Verlag Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2004, ISBN 3-11-018116-9 ( excerpts online ).

- Rudolf Simek : Lexicon of Germanic Mythology (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 368). 3rd, completely revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-520-36803-X .

Remarks

- ^ Gísli Sigurðsson: Vǫluspá. In: Heinrich Beck, Dieter Geuenich, Heiko Steuer (eds.): Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, Volume 35.De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2007, ISBN 978-3-11-018784-7 , p. 531 f.

- ^ Rudolf Simek: Lexicon of Germanic Mythology (= Kröner's pocket edition. Volume 368). 3rd, completely revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-520-36803-X , p. 53: probably Kenningar for Ymir.

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Vǫluspà. 2-10. Unless otherwise stated, quote from Arnulf Krause : Die Götter- und Heldenlieder der Älteren Edda. Reclam-Verlag, 2004, ISBN 3-15-050047-8 .

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Vǫluspà. 17 f., 20.

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Vǫluspà. 1

- ^ Song Edda: Vafþrúðnismál 29, 31, 33, 35

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Vafþrúðnismál 20 f.

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Grímnismál 40

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Hyndlulióð 30

- ↑ a b Lieder-Edda: Hyndlulióð 33

- ^ Prose Edda: Gylfaginnging 4–6

- ↑ Prose Edda: Gylfaginnging 6-8

- ^ Prose Edda: Gylfaginnging 9, 14 f.

- ^ Adam of Bremen: Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum . Around 1075, in the translation by JCM Laurent: Hamburgische Kirchengeschichte. 1893, IV 39 (Scholion)

- ↑ Tacitus: Germania 2,3-4

- ↑ Tacitus: Germania 39.1

- ↑ Compare Gerhard Perl: Tacitus - Germania. 1990, p. 236.

- ↑ Jordanes: De origine actibusque Getarum (Getica) XIII, 78; XIV, 79

- ↑ Ferdinand Hermann: Symbolism in the religions of the primitive peoples. Verlag Anton Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1961, p. 127 f.

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Vǫluspá 3rd text edition based on Titus Projekt, (online) , accessed on December 14, 2009.

- ↑ Jacob Grimm: German Mythology. 3 volumes. 1875-1878. (New edition: Marix, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-86539-143-8 , Volume 1, p. 467 f.)

- ↑ Kurt Schier: The creation of the earth from the primordial sea and the cosmogony of the Völospá. 1963, p. 311.

- ↑ In addition to Vǫluspà and Wessobrunn prayer, for example, in the Anglo-Saxon hallway blessing: “eordan ic bidde and upheofon”; in Heliand : "erda endi uphimil"; in the song Edda: Vafþrúðnismál 20: "hvaðan jǫrð of kom eða upphiminn"; on the Skarpåker rune stone : "iarþsalrifnaukubhimin" and the Ribe rune staff .

- ↑ a b Bernhard Maier: The religion of the Germanic peoples. 2003, p. 57 f.

- ↑ a b c d Bernhard Maier: The religion of the Germanic peoples. 2003, p. 58.

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Meid : The Germanic religion in the testimony of language. In: Heinrich Beck, Detlev Ellmers, Kurt Schier (eds.): Germanic religious history - sources and source problems. Supplementary volume no. 5 to the real dictionary of Germanic antiquity. 2nd Edition. Verlag Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1999, ISBN 3-11-012872-1 , p. 496. (Excerpts online)

- ↑ Kurt Schier: The creation of the earth from the primordial sea and the cosmogony of the Völospá. 1963, p. 311: undecided; Åke Viktor Ström: Germanic and Baltic religion. 1975, p. 243 f .: undecided; Anders Hultgård: Creation Myths. In: RGA 27 (2004), p. 245: "when nothing was."

- ↑ Anders Hultgård: Creation Myths. In: RGA 27. 2004, p. 245 f.

- ↑ Iranian Bundahishn. XXX, 6

- ^ Rudolf Simek: Lexicon of Germanic Mythology (= Kröner's pocket edition. Volume 368). 3rd, completely revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-520-36803-X , p. 136.

- ↑ Jan de Vries: Old Germanic history of religion. Volume 2; 1937, § 317. Rejecting: Eugen Mogk: Grundriss der Germanischen Philologie. Volume 2. But in the affirmative a large number of scientists: Åke Viktor Ström: Germanic and Baltic religion. 1975, p. 245 'Grundlose Gänung', Rudolf Simek: Lexicon of Germanic Mythology (= Kröner's pocket edition. Volume 368). 3rd, completely revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-520-36803-X , p. 136 'yawning primal gulf', Anders Hultgård: Creation myths. In: RGA 27 , 2004, p. 245 'gaping throat'.

- ↑ a b c d e Jan de Vries: Old Germanic Religious History Vol. 2. 1937, § 317

- ↑ René LM Derolez: Gods and myths of the Germanic peoples. 1974 (1959), p. 285.

- ↑ Åke Viktor Ström: Germanic and Baltic religion. 1975, p. 245.

- ↑ Rigveda X, 129, 1 Original online translation online

- ↑ Indian Bundahishn. I, 9 Originally online

- ↑ Song Edda: Vafþrúðnismál 28, 31

- ^ Tacitus: Germania 2,3

- ↑ Jan de Vries: Old Germanic History of Religions Vol. 2. 1937, § 318: only 'twin' - Åke Viktor Ström: Germanic and Baltic religion. 1975, p. 244 - Rudolf Simek : Gods and Cults of the Teutons. 2nd Edition. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2006 (first edition 2004), ISBN 3-406-50835-9 , p. 88.

- ↑ a b Bernhard Maier: The religion of the Germanic peoples. 2003, p. 60.

- ↑ a b c d e f Hermann Reichert: Mythical names. In: RGA 20. 2002, p. 471.

- ↑ Jan de Vries: Old Germanic History of Religions Vol. 2. 1937, § 318: several oriental religions - Bernhard Maier: The religion of the Germanic peoples. 2003, p. 60: many cultures.

- ↑ a b c Anders Hultgård: Creation myths. In: RGA 27 , 2004, p. 248.

- ↑ Rigveda. X.10 Original online translation online

- ↑ Iranian Bundahishn XXXI, 4

- ↑ Bernhard Maier: The religion of the Germanic peoples. 2003, p. 63.

- ↑ a b c Heinrich Beck: Problems of the migration history of religion. In: Dieter Geuenich (Ed.): The Franks and the Alemanni up to the "Battle of Zülpich" (496/97). Supplementary volume No. 19 to the Real Lexicon of Germanic Antiquity. Verlag Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1998, ISBN 3-11-015826-4 , p. 476.

- ↑ Åke Viktor Ström: Germanic and Baltic religion. 1975, p. 244 considers the equation to be absurd, but without justification.

- ↑ a b Jan de Vries: Old Germanic History of Religions Vol. 2. 1937, § 321

- ↑ Bernhard Maier: The religion of the Germanic peoples. 2003, p. 59.

- ↑ Indian Bundahishn I, 1–3. In the original online

- ↑ a b René LM Derolez: Gods and myths of the Germanic peoples. 1974 (1959), pp. 285-287.

- ↑ Anders Hultgård: Creation Myths. In: RGA 27. 2004, p. 246 f.

- ↑ a b Anders Hultgård: Creation myths. In: RGA 27 , 2004, p. 247.

- ↑ Jan de Vries: Old Germanic history of religion. Volume 2; 1937, § 317 affirmative. Elard Hugo Meyer: Germanic mythology. 1891, Volume 3, pp. 80 ff. Franz Rolf Schröder:… 9, 134 and 11, 3–5

- ↑ Kurt Schier: The creation of the earth from the primordial sea and the cosmogony of the Völospá. 1963, p. 304 says that not every dualism has to arise from the Iranian worldview.

- ^ Rudolf Simek: Lexicon of Germanic Mythology (= Kröner's pocket edition. Volume 368). 3rd, completely revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-520-36803-X , p. 89 agreeing: → Eyvind Fjeld Halvorsen: Élivágar. In: Kulturhistorik Leksikon for nordisk Medeltid 3. Malmö 1958, p. 597 f.

- ↑ a b c Heinrich Beck: Earth. In: RGA 7 , 1989, p. 439.

- ↑ Wolfgang Golther: Handbook of Germanic Mythology. Hirzel, Leipzig 1895. (New edition: Marix, Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-937715-38-X , p. 602.)

- ↑ Ferdinand Hermann: Symbolism in the religions of the primitive peoples. Verlag Anton Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1961, p. 127.

- ↑ Paul Hermann: German Mythology. 1898. (Newly published in 8th edition. Structure of Taschenbuchverlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-7466-8015-6 , p. 361.)

- ↑ Hermann Reichert: Mythical Names. In: RGA 20. 2002, p. 462.

- ^ Rudolf Simek: Lexicon of Germanic Mythology (= Kröner's pocket edition. Volume 368). 3rd, completely revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-520-36803-X , p. 443.

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Vafþrúðnismál 33

- ^ Prose Edda: Gylfaginning 5

- ↑ a b Jan de Vries: Old Germanic History of Religions Vol. 2. 1937, § 318

- ↑ Song Edda: Vafþrúðnismál 29, 35. Prose Edda: Gylfaginning 7

- ↑ a b Prose Edda: Gylfaginning. 6th

- ↑ From Old Norse auðr 'wealth' and * humula 'hornless', see Rudolf Simek: Lexicon of Germanic Mythology (= Kröner's pocket edition. Volume 368). 3rd, completely revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-520-36803-X , p. 30, which gives her name as 'the (milk-) rich, polled cow'. - Jan de Vries: Old Germanic History of Religions Vol. 2. 1937, § 318: 'the rich, hornless cow'.

- ^ Tacitus: Germania. 5

- ↑ Jan de Vries: Altgermanische Religionsgeschichte Vol. 2. 1937, § 318: Both Near Eastern as well as Indo-European parallels, if oriental fiefs, then integrated so early (Indo-Europeans) that it was already part of the ancient Germanic tradition. - René LM Derolez: Gods and myths of the Teutons. 1974 (1959), p. 287: In spite of similarities in other peoples, not necessarily Lehngut. - Åke Viktor Ström: Germanic and Baltic religion. 1975, p. 245: Indo-European origin because of Indian and Iranian parallels. - Bernhard Maier: Die Religion der Germanen , 2003, p. 59: Compare the Egyptian Hathor and the Greek Hera and other old European, oriental goddesses, thus perhaps common, pre-Christian inheritance from the Stone Age. - Rudolf Simek: Lexicon of Germanic Mythology (= Kröner's pocket edition. Volume 368). 3rd, completely revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-520-36803-X , p. 30 f. and Anders Hultgård: Creation Myths. In: RGA 27. 2004, p. 249: Probably older tradition because of the many parallels in the Near East.

- ↑ Jan de Vries: Old Germanic History of Religions Vol. 2. 1937, § 318 affirmative: → Krappe 5, 203 - → Eitrem NVA 1914, I, p. 331.

- ^ Rudolf Simek: Lexicon of Germanic Mythology (= Kröner's pocket edition. Volume 368). 3rd, completely revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-520-36803-X , p. 30.

- ^ Rudolf Simek: Lexicon of Germanic Mythology (= Kröner's pocket edition. Volume 368). 3rd, completely revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-520-36803-X , p. 31.

- ^ Rudolf Simek: Lexicon of Germanic Mythology (= Kröner's pocket edition. Volume 368). 3rd, completely revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-520-36803-X , p. 237: → C. Scott Littleton: The 'Kingship in Heaven' Theme. In: Jaan Puhvel (Ed.): Myth and Law among the Indo-Europeans: Studies in Indo-European Comparative Mythology. University of California Press, Berkeley, etc. 1970, pp. 83-121.

- ↑ a b c d e Jan de Vries: Old Germanic Religious History Vol. 2. 1937, § 322

- ^ Rudolf Simek: Lexicon of Germanic Mythology (= Kröner's pocket edition. Volume 368). 3rd, completely revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-520-36803-X , p. 64 f.