Germanic notions of fate

The Germanic notions of fate contain the views of the Germanic peoples from pagan times, according to which everything happens on the basis of unalterable necessity ( fate ). The available sources give only a few real insights into the pagan imagination, but it is certain that the Teutons believed in having a fate that was determined by a fate, probably in the form of three women. But whether they believed in this power of fate also in a religious sense cannot be decided.

swell

Germanic language skills

The linguistics has opened up a variety of words that the speakers of Proto-Germanic could use to the term fate express. They show that the Teutons had ideas about fate, but not what. Subordinate meanings of these words such as “death” or “war” indicate that the concept of fate had a negative tinge. The research tried to get to the underlying concepts of fate with the help of etymology . However, the ideas based on it do not allow any definite statements and should be treated with caution.

The following table lists the most important Germanic words of fate, including a simplified representation of the secondary meanings and the Indo-European roots.

| Old Norse | Old High German | Anglo-Saxon | Old Saxon | Germanic | meaning | Indo-European root |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mjötuðr | * mezzot? | me (o) tod, me (o) tud | metod, metud | * metoduz | Fate, partly proportioner (god) | * med- "measure" |

| örlög | urlag, urliugi | orlæg, orleg (e) | * uzlagam, * uzlagaz | Fate, partial war / struggle, law? | * legh- "lay, lie" | |

| sköp | giscap, giscaf | gesceap, gesceaf | (gi) skap, giskaft | * |

Fate, personality | * skap- "cut, split" |

| urðr | wurt | wyrd | would | * wurdiz | Fate, partly death | * uert- "turn, turn" |

Ancient authors

The ancient authors report nothing about the Germanic understanding of fate. They only prove the Teutons' belief in lots and omens ; in the opinion of the Roman writer Tacitus they even surpassed all other peoples. It is possible that the Teutons relied on the signs because they believed in predestination and providence, but they might as well have seen it as an expression of the gods' will.

Gentile mission

The oldest remarks on Germanic notions of fate come from Christian missionaries of the Middle Ages . Her explanations contrast, for example, the pagan belief in the inevitable fate of the Christian's certainty of salvation, in order to illustrate the superiority of the Christian God. It can be assumed that their representations show less the great importance of the pagan notions of fate, but rather served to give the pagans an easier transition to Christianity.

After all, fate was also thematized in Christian teachings and works of that time using the pagan-Germanic fate terms already mentioned, for example in the Old Saxon Gospel Harmony Heliand or in the doctrine of predestination by the Saxon monk Gottschalk von Orbais (both 9th century). The older research therefore assumed that with the use of the pagan-Germanic words, the pagan ideas were also adopted. But after careful investigation, it turned out exactly the opposite. Gottschalk's teaching is not based on pagan ideas, but on a further development of the Augustinian doctrine of predestination. The Heliand does not convey any pagan ideas either, since fate has no religious intrinsic value in it. In this, God neither replaces a pagan power of fate, nor does he place himself on a par with it. Fate is not described as God's level of action, but only as the effect of his power in individual cases. Fate always remains within the limited framework of the natural order, while God, in contrast, is represented as unlimited and supernatural, for example in Jesus' raising of the dead young man to Naïn .

The adoption of the heathen vocabulary of fate by the Christians also confirms that the Germanic idea of fate cannot have been shaped in such a way that it should have been classified as a serious danger to Christian interests. The use of the old words of fate should also serve to facilitate the transition to Christianity for the pagans.

However, it is entirely conceivable that the Christian god also became attractive to the pagans because, unlike their gods, he was not subject to fate, but rather possessed the metudaes maecti : the power to assign fate.

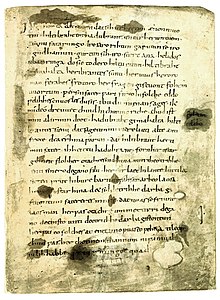

Hero seal

Only the early medieval heroic poetry , for example the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf (8th century) or the Old High German Hildebrandlied (9th century), allows closer insights into the fate of West Germanic peoples . Although these myths were formed in pagan times, by the time they were written they had already taken up and processed Christian and ancient ideas. The use of the old fate vocabulary does not allow any statement to be made about the pagan content of the portrayed ideas of fate even in heroic poetry. The fact that the hero is prophesied, for example, a fate that will come true, no matter what is done about it, could be explained in Christian terms by divine providence or anciently from the Aeneas tradition. Nevertheless, it can be assumed that the heroic poetry contains pagan ideas of unknown proportions.

The fate in heroic poetry develops out of the counterplay of the external causes and the inner nature of the hero. As a result, it has two faces, one or the other of which appears more depending on the weighting. On the one hand, the concept of fate can transcend in the case of unbelievable fortunes or harrowing perils, so that fate appears like the intervention of a higher power, whereby it is personified. On the other hand, the concept of fate can also become more immanent, so that fate arises from the personal characteristics of a person or their clan, for example through their innate happiness or salvation. Fate follows here from the strong bonds of the clan community, since as a community of fate in victory and defeat, in happiness and unhappiness, it demands unconditional solidarity. What happens to one clan member has happened to everyone else, so to speak. If the feeling of a clan and a personal sense of honor collide with one another, a tragic conflict arises, which sets in motion a terrible and no longer avertable fate. In heroic poetry, the driving forces behind this realization of fate are suffering and honor. It is typical that an attack on one's honor is seen as a fateful interference that cannot be avoided. The poets attach great importance to the fact that fate is not only carried out, but that the hero first recognizes the onset of doom and confirms the inevitable course, so that he can see and submit to his fate.

For example, in the Hildebrandlied, Hildebrand meets his son Hadubrand , who has not seen his father for many years and is convinced of his death. Hildebrand recognizes his son and wants to keep him from a duel with him, but Hadubrand does not want to believe that he is facing his father and mocks the man on the other side. The attack on the father's manhood makes the fight between the two inevitable. Hildebrand notes, full of pain and bitterness:

"Welaga nu, waltant got, quad Hiltibrant, - wewurt skihit!

ih wallota sumaro enti wintro - sehstic ur lante,

dar man mih eo scerita - in folc sceotantero.

so man at burc ęnigeru - banun ni gifasta.

nu scal mih suasat chind - suertu hauwan,

breton with sinu billiu, - eddo ih imo ti banin werdan. ”

Source: Hildebrandlied. Lines 49-54 (translation by Arnd Großmann)

"Well, now God reign, said Hildebrand, calamity [literally: calamity-fate] happens:

I wandered sixty summers and winters outside the country;

where I was always assigned to the army of fighters.

If you couldn't teach me to die at any castle:

Now my own child should hit me with the sword,

crush me with the blade, or I will kill him. "

The Christian influence is not difficult to recognize in the invocation of God, which, however, remains of a formal nature, since God does nothing against fate.

The pagan words of fate already come out of use in the German-speaking area in Old High German , or at the latest in Middle High German , and do not appear again afterwards. Other terms, such as “luck”, which in Middle High German times could be carriers of ideas of fate, no longer embody pagan ideas, but only Christian ones . In the high medieval heroic poems of the Nibelungenlied or the Gudrun saga , the pagan concept of fate no longer plays a role.

Eddic literature

The Völuspá occupies an exceptional position among the high medieval texts of the Nordic Edda , not only because it offers an outline of the mythical world history from creation to extinction, but also because most of its contents date from pagan times. In doing so, she subordinates the course of the world comprehensively to the violence of fate.

The first two people, Ask and Embla , are still fateless before they become human . They become people through the gods, but their fate is assigned to them by the Norns , who are charged with determining the fate of people at birth.

But not only people have an inevitable fate, the gods too. Baldur's death is predetermined and cannot be prevented. The same applies to the fall of the gods in the Ragnarok . Literally translated, the word means nothing other than "the fate of the gods". This idea is confirmed in the song Vafþrúðnismál in the Old Norse expression aldar rök "The end of the world".

Icelandic sagas

The Icelandic sagas , which were written from the 12th century onwards , also contain notions of fate with uncertain Christian influence . Some heroes of the sagas no longer trust the old gods who were inferior to Christianity, but rather their own power and strength. This belief in one's own power and strength, máttr ok megin , has entirely fatalistic features. The older research recognized in this the outflow of pagan notions of fate. However, here, too, closer investigations by Gerd Wolfgang Weber showed that the formula máttr ok megin only served the Christian authors of Iceland to build a bridge from paganism to Christianity for their pagan heroes. The writers did have an interest in washing their heroes clean, as they were related to them or at least part of their own local history. Due to the demarcation from the pre-Christian past, the belief in máttr ok megin represents its own myth about the belief in fate of the pagan ancestors.

Power of fate

Fate does not come out of nowhere, but is determined by a power of fate. Depending on how one understands the work of fate, the power of fate can be imagined either in the form of a personification as an entity or as an impersonal power that rules blindly, like a natural law, such as the Indian karma .

Power of gods and power of fate

The Germanic gods, especially as a whole, could adopt the trait of a power of fate if man submitted to their will like a fate or if their will was equivalent to a fate.

"Vill Óðinn ekki, at vér bregðum sverði, síðan er nú brotnaði. Hefi ek haft orrostur, meðan honum líkaði. "

“Odin doesn't want us to swing the sword since it broke into pieces; I fought as long as he liked it. "

Strictly speaking, however, there is only a concealment of the balance of power. For man, the will of Odin may be fate, but how free is the action of God when he too has a fate? Odin can ride into the world of the dead and wake up a dead seer with a magic song in order to inquire about the fate of his son Balder , but he can neither change the fate of Balder nor his own.

Since Jacob Grimm , the inability of the gods to change their fate has been understood in such a way that the power of gods is also subject to the power of fate. This idea could come from the Indo-European period, as the table below shows. But we also know something comparable from other cultures. There is nothing unusual about this, since the gods of a polytheistic religion (and thus also the Germanic gods) do not stand above the world, but are part of the world in which they represent the existing world order. As part of the world, like all other parts of the world, they are subject to the law of the world.

| people | term | Literal meaning | Power | description | Oldest evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the | rta (m) | impersonal | The right order. | ||

| karma | Work, act | impersonal | Universal law, according to which every act has a consequence corresponding to the act. | 6th century BC Chr. | |

| samsara | constant wandering | impersonal | Cycle of rebirths. | 6th century BC Chr. | |

| Iranians | Zurvan | time | personified | Creator God in Zurvanism . Father Ahura Mazdas and Angra Mainyus . Personification of time and eternity: determines everything, orders everything, orders everything in advance. | 4th century BC Chr. |

| Greeks | Moira | Share allocated to everyone | personified | With Homer the gods are powerless compared to the Moiren. | 9th century BC Chr. |

| Romans | Fate | Spell of fate | impersonal | Inevitable, reigning everything. |

The three women of fate

There is much to suggest that the Germanic peoples imagined the power of destiny as a trinity of women. This finds its clearest expression in the form of the three Norns of Nordic mythology , who are expressly assigned the task of determining the fate of people, but the three mother goddesses of the West Germanic matron cult are also related to fate.

The three Norns are called Urðr (“fate, death”, literally “become”), Verdandi (“becoming”) and Skuld (“should”). Simplified, their names stand for the three tenses past, present and future. However, this concept is not popular, but the work of Nordic scholars of the High Middle Ages , who adopted it from the Greek Moiren and Roman Parzen , who have a role similar to the Norns in their respective mythologies. The names of the three Norns were apparently also formed on the basis of the three times concept at that time. In Norse mythology, Verdandi is only mentioned in the Völuspá and Prose Edda , Skuld is only known as the name of a Valkyrie . The name Urds, of which it was long assumed that it was already verifiable for the primitive Germanic period, turned out to be a creation of the High Middle Ages (see section → Belief in fate ). The Nordic Norns, however, were not perfectly adapted to the Moiren and Parzen; for example, the Norns do not spin or weave fate.

The Norns are described as three meyjar "girls", that is, virgins, whose home is the source of fate on the world tree Yggdrasil . Its main task is to assign people their destiny at birth. You find yourself in the Nordic custom in which three women prophesy the fate of the newborn.

The West Germanic matrons, on the other hand, are actually chthontic mother goddesses who were represented in the Roman cult as three seated women: as donors of abundance and fertility. To that extent they do not correspond to the Norns, but more to the Nordic Disen and perhaps the Saxon Idis . But the three nameless mother goddesses also had an aspect of fate. There are few traces of it. Two Roman consecration stones were found in England, which are consecrated to the mother goddesses, who are also referred to as parcae (" women of fate").

“Matrib [us] Parc [is] pro salut [e] Sanctiae Geminae”

"To the mother goddesses, women of fate, for the well-being of the Sanctia Gemina"

“Matribu [s] Par [cis] […]”

"To the mother goddesses, women of fate [...]"

A document from the High Middle Ages can be found in Bishop Burchard von Worms , who asked women the following confessional question: “Did you believe what some people believe, that those who are called Parcae in popular belief, really exist and at the birth of a person can determine what they want [...]? "

Saxo Grammaticus also reports that women of destiny were asked about the future fate of children (Gesta Danorum, lib. VI): "Mos erat antiquis super futuris liberorum eventibus Parcarum oracula consultare." ("It was customary to ask the elderly about future life events of children oracles of women of fate." - With oraculum both the place and the saying can be meant.) Here the ideas of the matrons and the Norns converge. This makes it probable that the concept of three women of fate already forms the basis of the Roman matron cult, which was evidently particularly emphasized in late pagan times in the north in the form of the three Norns.

The one who assigns fate

The literal meaning of the Germanic concept of fate * metoduz suggests that the Germanic tribes may have known another personification of the power of fate, which, however, would not have left any traces apart from the meaning and use of the word. It could be an old idea, at least the term is quite old.

The Germanic masculine * metoduz is derived from Indo-European * med- "measure". It is preserved in Old Norse mjötuðr , Anglo-Saxon meotod and Old Saxon metud . In all three languages it means "fate". In the past, its literal meaning was often expressed as “what was (too) measured”. However, the Christians sometimes also used the word in the sense of “power of fate” and referred to God or the power of God. For example, a Christian hymn in 7th century England expresses “God's power” through the term metudaes maecti . It follows that God is the meotod who assigns fate. In addition, the word has a male gender in all three languages, also in the non-personal meaning as "fate". * Metoduz therefore apparently means a male “metering power”, the “destiny metering”. Clarified: The one who measures (determines) fate.

There is a few scholars of the opinion that the * metoduz refers to the Nordic giant Mimir , as he is closely connected with knowledge, wisdom and prophecy and his name can be traced back to the same Indo-European root * med- as * metoduz .

Impersonal power of fate

It is quite possible that the Teutons originally imagined the power of fate to be impersonal.

Part of the mostly older research is based on the word etymology of the Germanic term * uzlagam (* uzlagaz) . The Germanic neuter * uzlagam "fate, fate" is made up of the prefix * uz "(her) from" and the noun * lagam "location", which is derived from Indo-European * legh- "laying". Literally, * uzlagam means "the laid out". In the Germanic languages that emerged from the original Germanic, the word also took on the meaning "war", in Old Saxon this even became the sole meaning. From the Indo-European word stem * legh- , however, the meaning "law" also developed, in Latin lex. Anglo-Saxon lagu (which developed into English law ), Middle Low German lach and Old Norse Lög . By interpreting the prefix * uz "(her) from" in the sense of "first, original", Friedrich Kauffmann arrived at an interpretation of * uzlagam as " original law". Walther Gehl understood the word in a similar way as “highest determination” and Eduard Neumann as “that which has been fixed, the fixed”. Interpretations of this kind were still popular in recent research. Mathilde von Kienle , on the other hand, represented a completely different interpretation . According to her, * uzlagam could have assumed the meaning of "fate" because of the chopsticks laid out when loosing, which Tacitus describes in Germania .

References to a possibly originally impersonal power of fate can also be found in the Icelandic sagas, in which the power of fate is depersonalized.

Ultimately, however, research today does not have sources that reliably prove that the heathen Germanic peoples imagined the power of destiny to be impersonal.

Essence of destiny

The contents of the Germanic idea of fate cannot be precisely determined due to the sources. The following basic features can only be regarded as pagan-Germanic with a greater or lesser degree of probability.

The Germanic peoples apparently assumed that every person was assigned a fate at (or shortly after) birth. In the Völuspá , the poet emphasizes that the first two people, Ask and Embla , were without fate before they became people. The gods created the first humans, but the Norns determined their fate.

"Þær lög lögðo

þær líf kuro

alda börnom

örlög seggia."

"They [the Norns] laid down rules,

they chose the life of

the

children of men , the fate of men."

At the center of the Germanic idea of fate is that what ever happens is what has to happen.

“Gæð a wyrd swa hio scel.”

"Fate always goes as it has to."

Fate is always what is just about to become, as the most important word of fate * wurðiz shows. The Germanic feminine * wurðiz "fate, fate" is made up of * wurð and an i- suffix . * Wurð is derived from the Germanic verb * werþan "werden", which in turn comes from Indo-European * uer (t) - "(to) turn, turn". Becoming thus originally means “turning, turning”, from which the meaning “turning towards something, becoming something” developed. From this one concludes that * wurðiz still had the idea that time progresses in recurring cycles. This means that the future flows into the past again, comparable to the turning of the wheel of fortune. * Wurðiz therefore means “that which is just becoming”, which at the same time expresses “eternal becoming”.

Fateful events cannot be influenced and cannot be prevented. The human will can definitely oppose it, but since one can only submit to fate, it should be in harmony with it in one's own interest. If fate is realized, it has nothing to do with chance.

In heroic poetry and the Icelandic sagas in particular, it is emphasized that a ruling fate is recognized and recognized by the person concerned. It is not about a rational consistency, but an emotional one.

- In the Icelandic Gísla saga , Gisli wants to make the blood covenant with his brother and two brothers-in-law, but has a bad premonition that the covenant will not come about. The four then fall on their knees and call on the gods to witness their covenant, but at the last moment one of the two brothers-in-law suddenly refuses to make the blood covenant with the other. Then Gisli also withdraws his hand and says: "Now it has gone, as I suspected, and it seems to me that fate has a hand here."

The occurrence of fate is usually experienced as negative. This results from the negative meanings that important fateful terms also have: * wurdiz also means "death" and * uzlagam also means "war". However, fate does not have to be negative. It is basically open on both sides.

"Ef nornir ráða örlögum manna, þá skipta þær geysi ójafnt, he sumir hafa god líf ok ríkuligt, en sumir hafa lítit lén eða lof, sumir langt líf, sumir skammt."

“If the Norns determine fate, then they decide extremely unfairly. Because some have a good and rich life, others have little good and little reputation, some have a long life, others a short one. "

Belief in fate

During the time of the Third Reich (1933–1945), the question of whether the Germanic peoples believed in fate as much as they did in their gods (Germanic belief in fate) was intensely discussed in research . A number of works have been published mainly in Germany, including by Hans Naumann , Walter Baetke , Walther Gehl and Werner Wirth .

Since it emerges from the Völuspá that the gods also have a fate that they cannot avert and against which they, like humans, are powerless, it was concluded, conversely, that there was (at least) a power in Norse mythology that was over the Gods stood. In the search for this sensu stricto super-power it was found that the most powerful of the three Norns, Urd (Old Norse Urðr), has an equivalent in the Old English Wyrd , which is not only linguistic but also content-wise. Old Norse urðr and Anglo-Saxon wyrd could stand both as abstractions for fate and personified for a feminine power of fate. So the proof seemed to be provided that Urd and Wyrd go back to a goddess of fate from ancient Germanic times, in which the Teutons also believed religiously.

Hans Naumann derived heroic pessimism as a typical Germanic attitude from the vain struggle of the gods against their downfall and numerous comparable descriptions from the heroic epics and Icelandic sagas . In his view, the Teuton does not surrender to his inevitable fate without doing anything, but resists it with all his might and ultimately unsuccessfully, but heroically, goes into his predetermined death. The National Socialists knew how to use these ideas effectively for their own purposes. Hermann Göring , for example, compared the fateful and heroic downfall of the Burgundians in the Nibelungenlied with the downfall of the 6th German Army in the Battle of Stalingrad , which will be spoken of with holy shudder in 1,000 years.

In the fifties and sixties of the twentieth century, only a few works on the topic appeared, but they turned the previous image of science on its head ( Eduard Neumann , Ladislaus Mittner, Gerd Wolfgang Weber). After a closer examination of the existing sources it turned out in particular that the ancient Germanic goddess of fate Urd / Wyrd did not exist. Wyrd even turned out to be a purely Christian creation, which was determined by the understanding of ancient Fortuna (Gerd Wolfgang Weber).

In Anglo-Saxon, in pagan times, wyrd was used to describe the indefinite experience of a momentous event that was not caused by oneself. In Christian times, wyrd then mainly stood for an event as an expression of the uninterrupted process of change in creation according to the divine plan of salvation. It was not until medieval times that Anglo-Saxon wyrd was also used personally. Wyrd thus became a personification of fate, but there was no merging with a figure from Germanic mythology like the Norn Urd. But Urd, too, is only a creation of the High Middle Ages. In Nordic literature, her name appears mostly in connection with the source U rðrbrunnr , which is usually referred to as " Urdbrunnen " after her . But since the source is mentioned much more often than the Norn, it follows that the name of the source should not be translated as "Source of the Urd", but as "Source of Fate".

Even if the most important argument in favor of a Germanic belief in fate has been dropped, the widespread worship of the three women of fate and the pagan parts of Edda literature and Icelandic sagas, which support a religious conception of fate, still remain in the Germanic world. As a result, according to the current state of science, a Germanic belief in fate can neither be proven nor excluded.

literature

In the order of the year of publication.

- Friedrich Kauffmann : About the Germanic peoples' belief in fate. In: Journal for German Philology. Volume 50, 1926, pp. 361-408.

- Mathilde von Kienle: The concept of fate in old German. In: words and things. 15, 1933, pp. 81-111.

- Hans Naumann : Germanic belief in fate. Publishing house Eugen Diederichs, Jena 1934.

- Walter Baetke : Germanic belief in fate. In: New Yearbooks for Science and Youth Education. 10, 1934, pp. 226-236.

- Walther Gehl: The Germanic belief in fate. Junker and Dünnhaupt Verlag, Berlin 1939.

- Werner Wirth: The belief in fate in the Icelandic sagas. In: Publications of the Oriental Seminar of the University of Tübingen. Volume 11, Stuttgart 1940.

- Eduard Neumann : The fate in the Edda, Volume 1: The concept of fate in the Edda. Verlag W. Schmitz, Giessen 1955.

- Ladislao Mittner : Wurd: The sacred in the old Germanic epic. Francke publishing house, Bern 1955.

- Jan de Vries : Old Germanic history of religion . 2nd, revised edition. 2 volumes, 1956–57. Walter de Gruyter publishing house, Berlin.

- Johannes Rathofer: The Heliand. Theological sense as a tectonic form. Preparation and foundation of the interpretation. In: William Foerste (Ed.): Low German Studies. Volume 9, Böhlau Verlag, Cologne / Vienna 1962, pp. 129–169 (concept of fate in Heliand.) Lwl.org (PDF)

- Willy Sanders: Luck. On the origin and development of meaning of a medieval concept of fate. In: William Foerste (Ed.): Low German Studies, Volume 9. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne / Vienna 1965. lwl.org (PDF).

- Åke Viktor Ström: Scandinavian Belief in Fate. In: Fatalistic Beliefs. Stockholm 1967, pp. 65-71.

- Gerd Wolfgang Weber: Wyrd - studies on the concept of fate in Old English and Old Norse literature. Publishing house Gehlen, Bad Homburg / Berlin / Zurich 1969.

- Albrecht Hagenlocher: Fate in Heliand. Use and meaning of the nominal designations (= Low German Studies. Volume 21). Böhlau Verlag, Cologne / Vienna 1975. lwl.org (PDF).

- Åke Viktor Ström, Haralds Biezais : Germanic and Baltic religion . Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart 1975, ISBN 3-17-001157-X .

- Mogens Brönsted: Poetry and Fate. A Study of Aesthetic Determination . Publishing house of the Institute for Linguistics of the University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck 1989, ISBN 3-85124-132-0 , p. 173-176 .

- Wolfgang Meid : The Germanic religion in the testimony of language . In: Heinrich Beck, Dieter Geuenich, Heiko Steuer (Hrsg.): Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . 2nd Edition. Supplementary volume 5. Verlag Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1992, ISBN 3-11-012872-1 , p. 490 f .

- Rudolf Simek : Belief in fate . In: Heinrich Beck, Dieter Geuenich, Heiko Steuer (Hrsg.): Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . 2nd Edition. tape 27 . Verlag Walter de Gruyter, Berlin - New York 2004, ISBN 3-11-018116-9 , pp. 8-10 ( books.google.de ).

- Anthony Winterbourne: When the Norns Have Spoken . Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, Madison 2004, ISBN 1-61147-296-2 .

- Rudolf Simek : Lexicon of Germanic Mythology (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 368). 3rd, completely revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-520-36803-X .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g Rudolf Simek: Schicksalsglaube. RGA 27, p. 9.

- ↑ Orlag in Old Saxon no longer meant fate, but only war.

- ↑ * gaskapam did not yet mean fate in Germanic.

- ^ Tacitus, Germania , 10

- ^ Walter Baetke: Germanic belief in fate. In: New Yearbooks for Science and Youth Education. 10. 1934, p. 226.

- ↑ René LM Derolez: De Godsdienst der Teutons. 1959, German: Gods and Myths of the Teutons, translated by Julie von Wattenwyl, Verlag Suchier & Englisch, 1974, p. 218 f.

- ^ For example Beda Venerabilis , Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, II 13 through the parable of sparrows (8th century)

- ^ Rudolf Simek: Belief in fate. RGA 27, p. 8 f.

- ^ Albert Hagenlocher: Fate in Heliand. 1975, pp. 218-220.

- ↑ Compare Jan de Vries: Old Germanic Religious History. 1957, § 190: "[...] the Teuton did not come to a unified view."

- ↑ Compare Gerd Wolfgang Weber: Wyrd. 1969, p. 132 f., Who developed this idea for the old English wyrd : The continued use of wyrd by Christian authors proves that wyrd did not designate a pagan power of fate, but was a term without a specific pagan-religious predicament.

- ↑ a b c d Hans-Peter Hasenfratz: The religious world of the Teutons - ritual, magic, cult, myth. Herder publishing house, Freiburg i. Br. 1992, ISBN 3-451-04145-6 , p. 112.

- ↑ a b Hermann Reichert: Hero, hero poetry and hero saga. In: Heinrich Beck, Dieter Geuenich, Heiko Steuer (Hrsg.): Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Volume 14, 2nd edition. Verlag Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1999, p. 269.

- ↑ Mogens Brönsted: Poetry and Fate. A Study of Aesthetic Determination. Publishing house of the Institute for Linguistics of the University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck 1989, p. 174 f.

- ↑ Willy Sanders: Luck. 1975, p. 38.

- ↑ a b c Mogens Brönsted: Poetry and fate. A Study of Aesthetic Determination. Publishing house of the Institute for Linguistics of the University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck 1989, p. 173.

- ↑ Willy Sanders: Luck. 1975, p. 36.

- ↑ Willy Sanders: Luck. 1975, pp. 42, 45.

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Völuspá 17 (citation of the Lieder-Edda after Arnulf Krause: Die Götter- und Heldenlieder der Älteren Edda. Reclam, 2004, ISBN 3-15-050047-8 )

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Völuspá 20

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Völuspá 31 f.

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Völuspá 44 f.

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Völuspá 44

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Vafþrúðnismál 39

- ↑ Compare René LM Derolez: De Godsdienst der Germanen. 1959, German: Gods and Myths of the Teutons, translated by Julie von Wattenwyl, Verlag Suchier & Englisch, 1974, p. 259.

- ^ Rudolf Simek: Lexicon of Germanic Mythology (= Kröner's pocket edition. Volume 368). 3rd, completely revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-520-36803-X , p. 272, keyword "máttr ok megin"

- ↑ René LM Derolez: De Godsdienst der Teutons. 1959, German: Götter und Mythen der Teutons, translated by Julie von Wattenwyl, Verlag Suchier & Englisch, 1974, p. 280 f., Who even more or less equates the gods and the Norns as powers of fate.

- ↑ Jan de Vries: Old Germanic history of religion. 1957, § 190

- ↑ Hans-Peter Hasenfratz: The religious world of the Teutons - ritual, magic, cult, myth. Herder publishing house, Freiburg i. Br. 1992, ISBN 3-451-04145-6 , p. 111.

- ↑ Jacob Grimm: German Mythology. 3 volumes. 4th edition. 1875-1878. New edition Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-86539-143-8 , p. 636 [old: Volume 1 + 2, p. 714.]

- ↑ Bernhard Maier: The religion of the Teutons - gods, myths, world view. Verlag Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-50280-6 , p. 62 f.

- ↑ Hans-Peter Hasenfratz: The religious world of the Teutons - ritual, magic, cult, myth. Herder publishing house, Freiburg i. Br. 1992, ISBN 3-451-04145-6 , p. 113 f.

- ↑ Hilda Roderick Ellis-Davidson: Pagan Europe - Early Scandinavian and Celtic Religions. Manchester University Press, 1988, ISBN 0-7190-2579-6 , pp. 163 ff. Excerpts online.

- ↑ a b c Åke Viktor Ström: Germanic and Baltic religion. 1975, p. 251.

- ↑ a b c d e Rudolf Simek: Lexicon of Germanic Mythology (= Kröner's pocket edition. Volume 368). 3rd, completely revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-520-36803-X , p. 307 “Nornen”.

- ^ Gerd Wolfgang Weber: Wyrd. 1969, p. 150.

- ↑ a b Bernhard Maier: The religion of the Teutons - gods, myths, worldview. Verlag Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-50280-6 , p. 62.

- ^ Rudolf Simek: Lexicon of Germanic Mythology (= Kröner's pocket edition. Volume 368). 3rd, completely revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-520-36803-X , p. 465 “Verdandi”.

- ^ Rudolf Simek: Lexicon of Germanic Mythology (= Kröner's pocket edition. Volume 368). 3rd, completely revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-520-36803-X , p. 387 "Skuld"

- ^ Snorri Sturluson: Prose-Edda, Gylfaginning. 15th

- ↑ Jan de Vries: Old Germanic history of religion. 1957, § 530

- ^ Gerd Wolfgang Weber: Wyrd. 1969, p. 153 speaks because of Nordic? Folk tales and beliefs clearly suggest that the three women of fate are based on old ideas.

- ↑ Jan de Vries: Old Germanic history of religion. 1957, § 522, 525, 530

- ↑ Simek, 2006, p. 267 ff.

- ↑ a b c d Rudolf Simek: Belief in fate. RGA 27, p. 10.

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Meid: The Germanic religion in the testimony of language. In: Heinrich Beck, Detlev Ellmers, Kurt Schier (eds.): Germanic Religious History - Sources and Source Problems - Supplementary Volume No. 5 to the Real Lexicon of Germanic Antiquity. 2nd Edition. Verlag Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1999, ISBN 3-11-012872-1 , p. 491.

- ^ Walter Baetke: Germanic belief in fate. In: New Yearbooks for Science and Youth Education, 10. 1934, p. 70. For more examples, see Åke Viktor Ström: Germanische und Baltische Religion, 1975, p. 249, FN 6

- ↑ a b Åke Viktor Ström: Germanic and Baltic religion. 1975, p. 249.

- ↑ a b Rudolf Simek: Belief in fate. RGA 27, p. 9 f.

- ↑ Jan de Vries: Old Norse Etymological Dictionary. 2nd Edition. Brill Archive, 1957, Volume 1, p. 390.

- ↑ Åke Viktor Ström: Germanic and Baltic religion. 1975, p. 254.

- ↑ Gerhard Köbler: Germanic dictionary. 3. Edition. 2003.

- ^ Comparative dictionary of the Indo-European languages. 1894, volume 3, p. 424 f.

- ↑ Friedrich Kauffmann: About the belief in fate of the Germanic peoples, 1926, p. 382.

- ↑ Walther Gehl: Der Germanische Schicksalsglaube, 1939, p. 23.

- ↑ Eduard Neumann: The fate in the Edda. 1955, volume 1, p. 38 f.

- ↑ Åke Viktor Ström: Germanische und Baltische Religion, 1975, p. 249 Gehl agrees, Anthony Winterbourne: When the Norns Have Spoken, 2004, p. 90 f., Translated as “supreme law”.

- ^ Mathilde von Kienle: The concept of fate in old German. In: Words and Things 15, 1933, pp. 81–111; Walther Gehl: Der Germanische Schicksalsglaube, 1939, p. 23; Günter Kellermann: Studies on the names of God in Anglo-Saxon poetry. Dissertation, Münster 1954, p. 232.

- ↑ Wolfgang Meid : The Germanic religion in the testimony of language. In: Heinrich Beck, Detlev Ellmers, Kurt Schier (eds.): Germanic Religious History - Sources and Source Problems - Supplementary Volume No. 5 to the Real Lexicon of Germanic Antiquity. 2nd Edition. Verlag Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1999, ISBN 3-11-012872-1 , p. 490 f.

- ↑ a b Åke Viktor Ström: Germanic and Baltic religion. 1975, p. 250.

- ↑ Åke Viktor Ström: Germanic and Baltic religion. 1975, p. 255.

- ^ Walter Baetke: Germanic belief in fate. In: New Yearbooks for Science and Youth Education. 10. 1934, p. 228.

- ↑ Overview in Åke Viktor Ström: Germanic and Baltic religion. 1975, p. 249.

- ↑ Bernhard Maier: The religion of the Teutons - gods, myths, world view. Verlag Beck, Munich 2003, p. 149 - Hans Naumann: Germanischer Schicksalsglaube. Jena 1934.

- ↑ Bernhard Maier: The religion of the Germanic peoples. 2003, p. 149 f.

- ^ Gerd Wolfgang Weber: Wyrd. 1969, pp. 65 f., 126, 132, 148, 155

- ^ Gerd Wolfgang Weber: Wyrd. 1969, p. 132 f.

- ^ Gerd Wolfgang Weber: Wyrd. 1969, p. 146.

- ^ Gerd Wolfgang Weber: Wyrd. 1969, p. 145.

- ^ Gerd Wolfgang Weber: Wyrd. 1969, p. 151 f.