Heliand

The Heliand is an early medieval old Saxon epic . In almost six thousand (5983) bar rhyming long line life is Jesus Christ in the form of a harmony of the Gospels retold. The title Heliand was given to the work of Johann Andreas Schmeller , who published the first scientific text edition in 1830. The word Heliand occurs several times in the text (e.g. verse 266) and is valued as an Old Low German loan transfer from the Latin salvator (“ Redeemer ”, “ Savior ”).

After the Liber evangeliorum by Otfrid von Weißenburg, the epic is the most extensive vernacular literary work of the “German” Carolingian era and thus an important link in the context of the development of the Low German language , but also of the German language and literature .

In order to enable the Low German readers / listeners of the Gospel poetry to intuitively comprehend and understand the transferred text, the unknown author enriched various plot elements with references to the early medieval Saxon world. The Heliand is therefore often cited as a prime example of inculturation .

Emergence

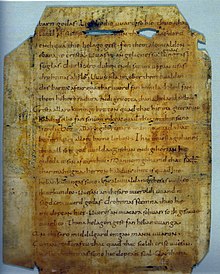

The time of writing is the first half of the 9th century, some researchers date it to around the year 830. The Old Saxon text is reproduced in Carolingian minuscules . In the spelling of some letters, however, influences of Anglo-Saxon writing tradition can be seen - depending on the handwriting more or less clearly .

In addition to Tatian , the Heliand poet used the Vulgate and various commentaries on the Gospel. The text concept is determined by the selection of texts and their poetic transformation. It is questionable to what extent apocryphal tradition found its way into Heliand.

There are two main theories for localization: An approach based on the history of ideas postulates the origin in the Fulda monastery , whereas linguistic and palaeographic analyzes have shown that it seems possible to assume that it was created in the Low German monastery of Werden on the Ruhr .

The social position of the poet is also unclear. Up until the 1940s, the older research literature tried to substantiate the statement in the Latin foreword of Heliand that a Saxon who was “knowledgeable about singing” had been commissioned to write it. If so, the poet would have the rank of continental Germanic skald (scop). More recent research approaches that highlight the theological and cultural-historical content of gospel poetry, however, see the poet as a trained monk.

Manuscripts and fragments

The work has been preserved in two almost complete manuscripts and four smaller fragments. The manuscripts and fragments are codified as follows:

- M (= Cgm 25) is kept in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich . The manuscript came there in the course of secularization in 1804 from the Bamberg Cathedral Library. The manuscript was probably written down by two scribes around 850 in Corvey Abbey . According to Wolfgang Haubrichs, the dialectal coloring of the manuscript is interpreted as East Westphalian. The text is edited with numerous initials, accents and notes as well as neumes from the 10th century for free or musical performance.

- C from the British Library in London (Codex Cottonianus Caligula) probably dates from the second half of the 10th century and was written down in southern England by a scribe of continental origin. The language has a Lower Franconian influence.

- S (= Cgm 8840), like M, is kept in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. This is a text fragment that was written in an unknown location around 850. The parchments were found in the library of the Johannes-Turmaier-Gymnasium in Straubing as the binding of a Schedel world chronicle . The language of this text version shows strong North Sea Germanic dialectal influences.

- P is a text fragment and is kept in the German Historical Museum in Berlin . The fragment comes from a book printed in Rostock in 1598 .

- V from the Vatican Library in Rome (Codex Palatinus) is a fragment from an astronomical composite manuscript from the early 9th century from Mainz . The fragment contains verses 1279-1358 (excerpts from the Sermon on the Mount ).

- In the spring of 2006, another fragment from the 9th century was discovered in the Bibliotheca Albertina in Leipzig.

The manuscripts can be divided into two groups: MS and CP . The fragment V probably goes back to the original. The recently rediscovered Leipzig fragment, also used as a binding, also seems to go back to the archetype.

Reading sample

Verses 4537–4549 from the Lord's Supper (â ê î ô û are long vowels, đ a "soft" ("English") th (Thorn sound), ƀ like w with both lips, uu like English w):

|

"Themu gi followon sculun |

“You should follow him |

Linguistic features

Verse style and lexicons correspond to the Germanic-Saxon tradition of poetry. To what extent an influence of Old English poetry can be assumed remains largely unclear. The Heliand is not directly related to Anglo-Saxon poetry. The existing parallels to the old English clergy epic can be justified by the Anglo-Saxon mission, but possibly also by a Lower Saxon-Anglo-Saxon cultural continuum.

Metric and style

Verse art and style were taken from the Anglo-Saxon Christian epic and further developed by the author . According to the Germanist Andreas Heusler , it was the work of a “gifted stylist and greatest linguist among the all-hand rhyming poets”. The Heliand is not the tentative beginning of an old Saxon literature, but the crowning conclusion and highest maturity of art.

Stylistic parallels can be found particularly in the Anglo-Saxon staff-rhyming clerical epic, the Beowulf epic and in Old High German literature that is comparable in time, for example in Muspilli . Similarities in the style of the Heliand poet and Old English poetry are not only evident in the long line rhyming with bars , but also in the use of appositionally added epithets and syntagms, the so-called variations:

- send tharod / te gigaruuuenne mîna gôma. Than tôgid he iu ên gôdlîc hûs , / hôhan soleri , the is bihangen al / fagarun fratahun.

- (To send you to have my feast. Then he will bring you to a splendid house, a high hall, which is covered all over with rich carpets.)

Another parallel to Old English poetry are verses that go beyond the line of verse and end in the next one (so-called hook style ). As a result, the incision is placed in the middle of the verse between the front and back of the long line. The alliance is retained, but it is sometimes divided into different sentences in the same verse:

- Thô uurđun sân aftar thiu / thar te Hierusalem iungaron Kristes / f orđuuard an f erdi, f undun all sô he sprak / uu ordtêcan uu âr: ni uuas thes gi uu and ênig.

- (So they set off for Jerusalem, the disciples of Christ, immediately on the journey and found everything just as he explained it, his words were true: there was never any doubt.)

Another characteristic of the Old Saxon Bible poetry that is cultivated in Heliand is the swell verse . This means that within a long line, which is metrically basically empty, a large number of prosodically unmarked syllables can be accumulated, which causes the verse tied by the stick to "swell". Overall, the Heliand poet's style is characterized by its epic breadth.

- Thuomas gimâlda - uuas im githungan mann, / diurlîc threatines thegan -: 'ne sculun uui in thia dâd lahan,' quathie

- (Thomas said - he was an excellent man to him, a dear servant of his master -: we should not blame him for this act)

Lexicons

The Heliand has clear Old Saxon and partly Old High German peculiarities in the lexicon . The lack of missionary words such as ôstārun for Easter is characteristic of the limited Anglo-Saxon radiations in Heliand . The author used the term pāsche , Old Saxon pāske , for the Passover festival in the Cologne ecclesiastical province - and thus also encompassing the Saxon area . In addition, there is the Old Saxon herro (lord) or the Rhineland, from the Celtic word ley (rock), which can be referred to as Franconian loanwords, as well as Old English terms such as (ađal-) ordfrumo (god). Such lexical findings indicate that the Heliand can be regarded as the fruit of intra-Germanic cultural contacts in a religious context.

Analogies to the Germanic world of ideas

The betrayal scene in the garden of Gethsemane (verses 4824-4838 and 4865-4881):

| The armed hurried until they came to Christ, the fierce Jews, where stood the mighty Lord with the disciples, waiting for fate, for the aiming time. Then the unfaithful Judas met him, the child of God, bowing his head, greeting the Lord, kissed the prince , with this kiss showing him the armed man, as he said. The loyal master, the Walter of the world, bore this patiently; the word only turned and asked him freely: “What do you come with the people and lead the people? You sold me the annoying one with the kiss, the people of the Jews, betrayed the gang "[...] | Then Simon Peter the swift sword angered mightily, his courage prevailed wildly , he did not speak a word, his heart was so great harm when they wanted to seize the Lord here. With lightning speed he drew the sword from the side and struck and hit the foremost enemy with full force , so that Malchus was damaged by the edge of the edge on the right side with the sword: his hearing was struck, his head was sore, his cheeks were bloodied with weapons Ear burst in bones and blood gushed from the wound . |

The Heliand shows various analogies to the Carolingian exegesis tradition. Its basic intention is consistently Christian-Biblical. Christian teaching is not suppressed out of consideration for the Saxon public. The Sermon on the Mount alone, with its central statements, takes up one eighth of the entire text. On the other hand, adaptations to the Germanic listeners and readers can be observed. Some passages and statements of the Bible contradict the Germanic ethos known from the early heroic poetry, for example the image of Jesus entering Jerusalem on a donkey, his self-renunciation, the rebuke of the lust for fame, the contempt for wealth, the renunciation of vengeance, the love of enemies, the condemnation of belligerence. According to the Germanic sense of justice, the denial of Peter would be guilty; The Heliand poet therefore tries to justify Peter's breach of faith.

The author therefore transferred the biblical persons into the framework of Saxon society analogously to the status order; for Christ and his disciples he consciously chose the relationship of obedience. The biblical cities become Saxon castles, the Judaean desert the Low German jungle. The Germanic traits of the Heliand are thus forms of perception that made the novelty of the Christian religion comprehensible for the Germanic pagan tradition ( accommodation ).

Where a Germanic tenor may be accepted, it refers in particular to the following areas.

"Allegiance Terminology"

The Germanic society defined by followers . A dux or comes binds various notables to followers ( comitatus ) by offering the followers protection and remuneration, but they support him militarily and administratively. This legal clientele association formed the basis of a tribal organization like the one owned by the Germanic gentes - including the pre-Carolingian Saxons. In Heliand, allegiance plays a role insofar as the relationship of Christ to the disciples is read as such. The personal designations used in particular seem to underpin this assumption. Christ is referred to as the King of Heaven and Lord, as a military leader and exalted prince, his disciples as followers who form a cooperative with him. The allegiance-building relationship of loyalty and oath ( treuva ) according to the Germanic understanding emerges latently, and contrary to the Gospels, most of Christ's disciples are of noble birth ( adalboran ). Not only the Saxon society was permeated by this thinking, but also the Franks Christianized for 400 years. The bond with the origin, the clan, continues unbroken in the early medieval Germanic sphere, whether still pagan or already Christianized.

“This is the glory of the sword that he stands firmly by his prince (Christ) and that he dies steadfastly with him. If we all stand by him, follow his journey, we let freedom and life be of little value to us; if we among the people succumb to him, our dear Lord, then we will long for good fame with the good guys. "

In Heliand, Christ and his disciples are dubbed thiodan (ruler) and thegana (warrior) because warriorism and the following relationships that dominate it were so deeply rooted in sentiment. In addition, the New Testament offers a variety of names that have been translated into various terms in the allegiance system, e.g. B. Κϋριος - dominus - threatening .

Names for Jesus are: folk threatenin , mundboro , landes war . For Herodes : folkkuning , thiodkuning , weroldkunig , folctogo , landes hirdi , boggebo (ring giver), medgebo (ruler). For Pilatus : heritogo .

Sense of justice and moral concept

The Sermon on the Mount scene with Christ on the king's seat as judge, surrounded by his disciples, looks like a Germanic thing . When he entered Jerusalem, Jesus did not ride on a donkey, but stately on a horse - the donkey could not be conveyed to people who were still in the old tradition. Also missing is the scene in which Christ asks you to turn your left cheek when you hit the right cheek. Christ acts according to Germanic customs and thus proves himself to be of integrity to the Germanic observer. His attitude towards death and its persecutors distinguishes him as a follower and warlord. He thus corresponds to the type of Germanic leader in the Nordic saga literature. The Germanic man, still standing in pagan tradition, attaches a higher rank to custom in the community than to the individual Christian faith. The faith itself is not tangible for the Germans, only the replacement of the term custom makes it detectable.

Names for social institutions in Heliand are: thing , thinghus, thingstedi, handmahal, heriskepi, manno meginkraft, mundburd .

Imagination of fate

The portrayal of Christ and his devotion to a fate that rules him, which cannot be averted, at best can be shaped, indicates a general Germanic worldview that affects religious feelings through a reference to the conception of fate. Fate (also referred to as was ) judges gods and people. It is the mysterious power to which even the heavenly ones are subject. Christ and his disciples cannot escape from him; their moral value rests on how they meet fate. Concepts of fate, however, do not require belief in the religious sense. In fact, nothing is known about a specifically Saxon belief in fate. Comparable terms from the lexicon of the other contemporary Germanic languages allow only limited conclusions, since the sources of comparison are usually based on purely Christian motives. Likewise, the term is wurd be interpreted with caution, as some deposits in Heliand shown to be based on prescriptions or even to explain simply meaning "death." However, in Heliand, the idea of an overwhelming fate sometimes seems to outweigh the belief in the power of God, or the Christian belief is equated with the belief in fate.

The name for the effective fate - wurd or wewurt ("Wehgeschick") - appears in early German literature next to Heliand only in the Hildebrand song (verse 47). Further terms for the fate in Heliand are word combinations like wurdigiskapu (creation of the Wurd; verse 197, 512) and reyanogiskapu (creation of advising powers; verse 2591 f. In connection with the end of the world) or methodogiskapu (creation of the measuring, metering; verse 2190, 4827).

The designation of the highest in the Saxon understanding destiny power as wurd the description of the resurrection leads the young man from Nain in a conscious direct confrontation between Christianity and the traditional pagan perspectives (vs. 2210). In the retelling of this episode in Tatian it simply says: "It was the only son of a widow". The same scene is portrayed in Heliand with psychological empathy and with a reference to the mighty fate ( metodogescapu ): The son was “the bliss and well-being of the mother until he was taken, the mighty fate”. The dichotomy between the Germanic view of life and the Christian worldview is slowly shifting to the softer, gentler Christian vocabulary of the century that followed Heliand. According to Johannes Rathofer, in this scene the once pagan concept of dignity is placed in a Christian "coordinate system" through the author's depiction , since Christ conquered the overwhelming fate through the resurrection.

Terms from the mythological tradition

Old Germanic terms, which probably originate from the mythological environment of Saxon Low Germany, are, for example, the terms: wihti (demons), hellia (hell, Germ.haljo underworld, kingdom of the dead, see Hel ), idis too Old Norse dīs (ir) or Dise .

See also

literature

Text editions and translations

- Otto Behaghel (ed.), Burkhart Taeger (arrangement): Heliand and Genesis (= old German text library . 4). 10th edited edition. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1996, ISBN 3-484-20003-0 .

- Clemens Burchhardt (Ed.): Heliand. The Verden old Saxon gospel seal from 830 transferred into the 21st century . Publishing house and printer Ernst Helbig, Verden 2007, ISBN 978-3-00-021184-3 .

- Felix Genzmer (translator): Heliand and the fragments of Genesis . (= Universal Library. Volume 3324). Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 3-15-003324-1 . [The translation was first published in 1955]

- Andreas Heusler : The Heliand in Simrock's transmission and the fragments of the Old Saxon Genesis . Leipzig 1921.

- Moritz Heyne : Heliand. With a detailed glossary . Schöningh, Paderborn 1905.

- Eduard Sievers : Heliand. Title edition increased by the Prague fragment and the Vatican fragments . Hall 1935 ( digitized ).

- Karl Simrock : Heliand. Christ's life and teaching . Friederichs, Elberfeld 1856 ( digitized 2nd edition 1866 ).

- Timothy Sodmann (Ed.): Heliand. The old Saxon text. De Oudsaksische tekst . Achterland, Vreden / Bredevoort 2012, ISBN 978-3-933377-16-6 .

- Wilhelm Stapel: The Heliand . Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 1953, DNB 451938844 .

Secondary literature

- Helmut de Boor : History of German literature . Volume 1.9, revised edition by Herbert Kolb. Munich 1979, ISBN 3-406-06088-9 .

- Wolfgang Haubrichs : Heliand and Old Saxon Genesis. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 14, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1999, ISBN 3-11-016423-X , pp. 297-308.

- Wolfgang Haubrichs: History of German literature. Part 1, (Ed.) Joachim Heinzle. Athenaeum, Frankfurt / M. 1988, ISBN 3-610-08911-3 .

- Dieter Kartschoke: Old German biblical poetry from realia to literature. In: Metzler Collection. Volume 135. JB Metzlersche Verlagbuchhandlung, Stuttgart 1975, ISBN 3-476-10135-5 .

- Johannes Rathofer: The Heliand. Theological sense as a tectonic form. Preparation and foundation of the interpretation (= Low German studies. 9). Cologne / Graz 1962.

- Hans Ulrich Schmid: A new 'Heliand' fragment from the Leipzig University Library. In: ZfdA. 135 (2006), ISSN 0044-2518 , pp. 309-323, JSTOR 20658399 .

- Werner Taegert : The "Bamberg" Heliand: The copy of an "excellent treasure" of the cathedral chapter library requested to Munich . In: Bamberg becomes Bavarian. The secularization of the Bamberg Monastery in 1802/03. Handbook for the exhibition of the same name . Edited by Renate Baumgärtel-Fleischmann . Bamberg 2003, ISBN 3-9807730-3-5 , pp. 253-256, cat.-no. 127.

- Jan de Vries : Hero song and legend . Francke, Bern / Munich 1961, DNB 455325545 .

- Jan de Vries: The spiritual world of the Teutons . Darmstadt 1964.

- Roswitha Wisniewski : German literature from the eighth to the eleventh century . Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-89693-328-0 .

Web links

- Digital copy of the Heliand (Hs. M)

- Digital copy of the Heliand (Hs. S)

- Heliand - BSB Cgm 25 - Digitized version of the manuscript in bavarikon

- E-text by Heliand , Bibliotheca Augustana

- E-text of Heliand (Titus)

- The Heliand (translation by Karl Simrock) in the Gutenberg-DE project

- The Heliand to Hear (Old Saxon)

Individual evidence

- ^ Veit Valentin: History of the Germans . Kiepenheuer and Witsch, 1979, p. 28.

- ↑ Sensational find: The Savior rises from the Mitteldeutsche Zeitung book cellar , May 18, 2006

- ↑ Haubrichs (1998), p. 298 f.

- ↑ Kluge: Etymological dictionary of the German language . Keyword: Degen, "warrior" from peripheral archaic vocabulary (8th century), mhd. Degen , ahd. Degan , thegan , as. Thegan . from g. Þegna - boy, servant, warrior.

- ↑ de Vries (1961), pp. 254-256, 341 f.

- ↑ Wisniewski (2003), p. 168. Haubrichs (1988), p. 25 f.

- ↑ de Vries (1964), p. 193 f.

- ↑ Ake Ström, Haralds Biezais : Germanic and Baltic religion . In: Religions of Mankind . Volume 11. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1975, pp. 249-260.

- ↑ de Boor (1978), p. 59: “Fate always remains a great, overshadowing self-power, not a fixed destiny in God's hands.” P. 60: “[The author] speaks to young converted listeners for whom the fateful thinking of the The core of their religious experience was. And one notices it in the poet himself: if he has thoroughly renounced the old gods, he too remains stuck with fate. "

- ↑ de Vries (1964), p. 84 ff. De Boor (1978), p. 66, comparing the Hildebrandlied.

- ^ Ernst Alfred Philippson: The paganism among the Anglo-Saxons . Tauchnitz, Leipzig 1929, p. 227 ff.

- ^ Rudolf Simek: Belief in fate . In Heinrich Beck, Dieter Geuenich, Heiko Steuer (Hrsg.): Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . Volume 27. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2004, ISBN 3-11-018116-9 , pp. 8-10.

- ↑ de Boor (1978), pp. 59 f., 66.

- ↑ Wisniewski (2003), p. 167: "This happens in the trinity wrdgiskapu, metod gimarkod endi maht godes (Fite 127/28, cf. 5394/95)"

- ^ Wisniewski (2003), p. 166.

- ^ Johannes Rathofer: Old Saxon literature . In: Ludwig Schmitt (Ed.): Kurzer Grundriss der Germanischen Philologie bis 1500 , Volume 2. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1971, ISBN 3-11-006468-5 , p. 254 f.