Last Supper of Jesus

The Lord's Supper , also known as the Last Supper , is the meal that Jesus Christ celebrated with the twelve apostles at the time of Passover before his death on the cross in Jerusalem . It is dated to the tenure of Pontius Pilate , who was 26-36 Roman governor in Judea . From the memory of that last meal, the ritualized sequence of a Jewish meal and the common meal celebrations of the early community, Christian forms of cult developed. Since the 2nd century this act has been called the Eucharist . The name Last Supper comes from the Luther Bible ; it was unknown to antiquity.

Biblical representation

All four New Testament evangelists and the first letter of the apostle Paul to the Corinthians report on Jesus' last supper . The events of Jesus' last meal were probably passed on by the early Christian community and developed into a ritual.

The oldest literary source, around 55/56 AD, is Paul; In 1 Cor 11 : 23-26 EU he passed on a report that he received himself (around 40 AD or 35 AD) and then passed it on to the Church in Corinth during his first mission around 50 AD and now quotes him again due to grievances in the celebration of the Lord's Supper (later Eucharist ):

“The Lord Jesus took bread on the night he was delivered, gave thanks, broke the bread and said: This is my body for you. Do this in memory of me! Likewise, after the supper he took the cup and said, This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this as often as you drink from it, in memory of me! For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord's death until he comes. "

Also in the three synoptic Gospels ( Mt 26.17–29 EU ; Mk 14.12–26 EU ; Lk 22.14–20 EU ) Jesus' interpretive words are at the center, the oldest version of which is according to Mk 14.22ff:

“During the supper he took the bread and said praise; Then he broke the bread, handed it to them, and said: Take, this is my body. Then he took the chalice, said the thanksgiving prayer, handed it to the disciples, and they all drank from it. And he said to them, This is my blood, the blood of the covenant, which is shed for many. Amen, I say to you: I will no longer drink of the fruit of the vine until the day when I drink of it again in the kingdom of God. "

The depiction of the farewell supper of Jesus in the Gospel of John does not contain a bread-breaking scene and thus no communion tradition in the narrower sense. Instead, the description begins with the scene of the washing of the feet, handed down by John alone ( Jn 13 : 1-20 EU ); this is followed by the distribution of bread to Judas Iscariot , which initiates his betrayal ( Jn 13 : 21-30 EU ). This is followed by longer farewell speeches which Jesus gives to the disciples during the meal and which extend over several chapters.

Interpretive words, differences, context

The sacrament traditions consistently report that during the meal Jesus blessed, broken and distributed bread to the disciples and handed them a wine goblet, referring to the bread as "my body" and the wine as "my blood". The different versions of these interpretive words, which in the parlance of the Christian liturgy are also referred to as " words of institution " or "words of change", are:

- Bread word

- with Markus "Take, this is my body."

- in Matthew: "Take, eat, this is my body."

- with Paul: "This is my body for you."

- in Luke: "This is my body, which is given for you."

- Chalice word

- with Markus: "This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many."

- in Matthew: "For this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many as a remission of sins."

- with Paul: "This cup is the new covenant in my blood."

- with Luke: "This cup is the new covenant in my blood, which is poured out for you."

1 Cor 11.23–25 EU (Pauline type or testamentary tradition, which also follows Luke ) and Mk 14.22–25 EU (synoptic type or liturgical tradition, which also follows Matthew ) are considered to be the oldest surviving communion traditions .

The most important differences and special features are:

- Paul: The supper takes place on “the night he was delivered”; Passover is not mentioned in the sacrament record.

Markus: The Last Supper is expressly Passover called (Passover) ( Mk 14.12 to 16 EU ). - Paul: Only the word of bread contains a soteriological addition: "... for you [given]", d. H. a statement about the salvation meaning of the death of Jesus. The following explanations mention bread and chalice together several times and thus make it clear that this interpretation also applies to the chalice passed around afterwards.

Markus: Only the cup word contains a soteriological addition: "... poured out for many". Since the blessing chalice is passed around after the satiation meal, the interpretation probably refers back to the whole meal. - Paul speaks of a “new covenant in my blood” and thereby alludes to Jeremiah 31:31 EU . There the new covenant promised for the end times is connected with the forgiveness of sins.

Markus speaks of the “blood of the covenant” with reference to the covenant on Sinai (quoted from Ex 24.8 EU ), without distinguishing between an old and a new covenant. - According to Paul, Jesus commanded after each word of bread and cup: “Do this in memory of me!”

Mark does not mention any repeat command from Jesus. - According to Paul, participating in the “Lord's Supper” means proclaiming the Lord's death until he comes.

- According to Mark, Jesus adds a vow to the interpretation of wine: "From now on I will no longer drink of the plant of the vine until I will drink it again in the kingdom of God."

The Pauline version does not actually speak of blood, but of the chalice, and thus possibly takes into account Jewish offense, since Jews were forbidden to enjoy blood. The closing verse 1 Cor 11:26 EU emphasizes the preaching character of the Lord's Supper. Elsewhere, the letter to the Corinthians speaks of Christ being sacrificed “as our Passover lamb” ( 1 Cor 5 : 7 EU ). Some regard this remark in connection with the Pauline version of the Lord's Supper account as a confirmation of the Johannine chronology, according to which Jesus died on the day of preparation at the time when the lambs were slaughtered for the Passover in Jerusalem.

Mark reports that all those involved - including Judas Iscariot, who was already identified as a traitor - received the wine distributed by Jesus: “and they all drank from it” ( Mk 14.23 EU ). Paul warns, however, against an “unworthy” participation in the Lord's Supper: “For whoever eats and drinks of it without considering that it is the body of the Lord draws judgment by eating and drinking” ( 1 Cor 11 , 27.29 EU ).

Only the Gospel of Matthew, which otherwise largely follows Mark's model, supplements the word from the cup with an express statement on the forgiveness of sins . This does not apply to his depiction of baptism ( Mt 3,6 EU ). One might infer from this that he presupposes the forgiveness of sins not only at baptism but repeatedly at each sacrament. Together with the soteriological formulas for the word of the bread and the chalice, it is one of the rare passages in the Gospels that explicitly suggest an atonement for the death of Jesus .

The Gospel of Luke has various peculiarities. In advance, Jesus speaks of his wish to celebrate the Passover (Passover) with the disciples. The eschatological announcement of Jesus that he will only drink from the “plant of the vine” again in the kingdom of God appears at the beginning of the Passover meal and is also extended to the eating of the meal. It is noticeable that two goblets are served in the Lukan report, one at the beginning and one at the end of the meal. The first chalice is followed by an account of the Lord's Supper, which essentially corresponds to the tradition of 1 Corinthians, but combines elements from both lines of tradition. In contrast to Paul, the repeat command is only quoted once, namely after the word of bread. With the second wine cup, Luke is the only evangelist to adopt the Pauline version of the word from the cup and speaks of the “new covenant”. As in the letter to the Corinthians, Jer 31:31 stands in the background of the words from the cup. Then he parallelizes the interpretive words for bread and wine: "given for you" - "poured out for you". The Mark and Paul templates thus appear to be aligned with one another. The word "thanksgiving" (" Eucharist ") comes across in Luke both in the bread and in the cup trade . Experts assume that the Lukan version of the Last Supper tradition reflects liturgical forms more clearly than the other versions.

In contrast to the three synoptic Gospels, the Gospel of John does not place Jesus' farewell supper on the Seder evening itself (evening of the 14th Nisan), but rather on an evening before the day of preparation (14th Nisan) of the Passover. Usually the evening before the set-up day is assumed.

Although the Gospel of John does not contain an institution report, there are several parallels to the sacrament tradition: Following the feeding of the five thousand , Jesus speaks to a group of listeners in the synagogue of Capernaum and describes himself as "the bread of life". The conversation ends in Jesus' pointed invitation to his listeners to eat his flesh and drink his blood ( Jn 6,48-59 EU ). This “bread speech” in Chapter 6 of the Gospel of John is usually interpreted as a reference to the Lord's Supper. Verse 51c is a particularly clear reference to the Lord's Supper tradition, which according to some exegetes could have been added later by an editor in alignment with the synoptic tradition: "And this bread is my flesh, which I will give for the life of the world." In the opinion of other liturgical historians, this passage together with other references could also speak for an independent early Christian tradition of the Lord's Supper, which did not understand the Lord's Supper, but the multiplication of bread as a foundation act of the Christian meal ritual. As a reminiscence or a substitute for the missing Lord's Supper scene , the “Breakfast at the Lake” described in addendum chapter 21, which Jesus had after his resurrection with the disciples at the lake of Tiberias ( Jn 21 : 9-13 EU ) , is sometimes considered .

Date and place of the Lord's Supper

Dating

Historians assume that the date of the crucifixion is between AD 30–36. Furthermore, physicists such as Isaac Newton and Colin Humphreys excluded the years 31, 32, 35, and 36 on the basis of astronomical calendar calculations for the festival of Passover, so that two plausible dates remain for the crucifixion: April 7, 30 and April 3, 33. Further narrowing down Humphreys suggests that the Last Supper took place on Wednesday April 1, 33, further developing Annie Jaubert's double Passover thesis:

All the Gospels agree that Jesus had a last supper with his disciples before he died on a Friday just around the time of the Feast of Passover (Passover was held annually on Nisan 15 , with the festival beginning at sunset), and that his Body remained in the grave the whole of the following day, i.e. on the Sabbath ( Mk 15.42 EU , Mk 16.1–2 EU ). However, while the three synoptic Gospels depict the Last Supper as the Passover Supper ( Mt 26.17 EU , Mk 14.1–2 EU , Lk 22.1–15 EU ), the Gospel of John does not explicitly designate the Last Supper as the Passover Supper and also places the Beginning of the feast of Passover a few hours after the death of Jesus. John therefore implies that Good Friday (until sunset) was the preparation day for the Passover festival (i.e. the 14th Nisan), not the Passover festival itself (15th Nisan). Another peculiarity is that John refers to the Passover festival several times as the “Jewish” Passover festival. Astronomical calculations of the ancient Passover dates, starting with Isaac Newton's method from 1733, confirm the chronological sequence of John. Historically, there have been several attempts to reconcile the three synoptic descriptions with John, some of which Francis Mershman compiled in 1912. The church tradition of Maundy Thursday assumes that the last supper took place on the evening before the crucifixion.

A new approach to resolve the (apparent) contradiction was put forward by Annie Jaubert during the Qumran excavations in the 1950s . She argued that there were two feasts of Passover: on the one hand, according to the official Jewish lunar calendar , according to which in the year of Jesus' crucifixion the feast of Passover fell on a Friday; On the other hand, there was also a solar calendar in Palestine, which was used, for example, by the Essenesect of the Qumran community, according to which the Passover festival always took place on a Tuesday. According to Jaubert, Jesus would have celebrated Passover on Tuesday and the Jewish authorities three days later, on Friday evening. However, Humphreys stated in 2011 that Jaubert's thesis could not be correct, because the Qumran Passover (according to the solar calendar) was generally celebrated after the official Jewish Passover. Nonetheless, he advocated Jaubert's approach of considering the possibility of celebrating Passover on different days. Humphreys discovered another calendar, namely a lunar calendar based on the Egyptian calculation method , which was then used by at least some Essenes in Qumran and the Zealots among the Jews and is still used today by the Samaritans . From this, Humphreys calculates that the Last Supper took place on Wednesday evening April 1, 33. Humphreys implies that Jesus and the other churches mentioned followed the Jewish-Egyptian lunar calendar as opposed to the official Jewish-Babylonian lunar calendar .

The Jewish-Egyptian calendar is presumably the original lunar calendar from Egypt, which according to the Exodus was probably introduced in the 13th century BC in the time of Moses , the then in the religious liturgy of Egypt and at least until the 2nd century AD in Egypt was common. During the 6th century BC, in exile in Babylon , Jews in exile adopted the Babylonian method of calculation and introduced it when they returned to Palestine.

The different Passover dates come about because the Jewish-Egyptian calendar calculates the date of the invisible new moon and sets it as the beginning of the month, while the Jewish-Babylonian calendar only observes the waxing crescent moon around 30 hours later and notes it as the beginning of the month. In addition, the Egyptian day begins at sunrise and the Babylonian day at sunset. These two differences mean that the Samaritan Passover usually falls one day earlier than the Jewish Passover; in some years several days earlier. The old calendar used by the Samaritans and the new calendar used by the Jews are both still used in Israel today. According to Humphreys, a last supper on a Wednesday would make all four gospels appear at the correct time, it placed Jesus in the original tradition of Moses and also solved other problems: there would be more time than in the traditional reading - last supper on Thursday - for the various interrogations Jesus and for the negotiation with Pilate before the crucifixion on Friday. In addition, the calculated timing - a Last Supper on a Wednesday, followed by a daylight trial before the Supreme Council of Jews on Thursday, followed by a brief confirmatory trial on Friday, and finally the crucifixion - would be in line with Jewish judicial rules on death penalty charges . According to the oldest handed down court regulations from the 2nd century, a night-time trial of capital crimes would be illegal, as would a trial on the day before the Passover festival or even on the Passover festival itself.

Matching the ancient calendar

At the time of Jesus there were three calendars in Palestine: the Jewish-Babylonian (the day begins at sunset), the Samaritan-Egyptian (the day begins at sunrise), and the Roman-Julian (the day begins at midnight, like today). The beginning of the month of both Jewish calendars is usually shifted by one to two days, depending on the position of the moon. According to all four Gospels, the crucifixion took place on the Friday before sunset, whereby the corresponding month's date (14/15/16 Nisan ) varies depending on the ancient definition, here using the example of the year 33:

JUD--------12 NISAN---------|m--------13 NISAN---------|---------14 NISAN-----+---|M--------15 NISAN---------|

TAG--------MI---------------|m--------DO---------------|---------FR-----------+---|M--------SA---------------|

SAM------------|---------14 NISAN---------|---------15 NISAN---------|--------+16 NISAN---------|---------17 NISAN-

TAG------------|---------MI--m------------|---------DO---------------|--------+FR--M------------|---------SA-------

ROM-----|---------01 APRIL---m-----|---------02 APRIL---------|---------03 APRIL---M-----|

TAG-----|---------MI---------m-----|---------DO---------------|---------FR----+----M-----|

24h 6h 12h 18h 24h 6h 12h 18h 24h 6h 12h 18h 24h

According to Ex 12.6 EU , the slaughter of the Passover lamb is set for the evening of the 14th Nisan, and the beginning of the following Passover meal at the time immediately after sunset. Depending on which calendar the respective congregation followed, the Passover meal took place in Palestine on April 1st and April 3rd in the year 33. The calculated crucifixion time for the year 33 is entered here as “+” (at 3 p.m.), the official Jewish Passover meal as “M” and the Samaritan (and also Essen and Zealot) Passover meal as “m”. The date of the Galilean Passover meal is not recorded.

Even today, the Passover meal is celebrated in Israel on two different dates each year, depending on the congregation. H. Jewish or Samaritan; The Samaritan religious community today (as of 2019) has 820 members. This religious community was much larger in antiquity and experienced a heyday in the 4th century AD. The Samaritans' own literature is, however, "without exception late and historically only to be used with extreme caution." Calendar issues were viewed by the Samaritans as secret knowledge; Experts believe that the Samaritan system developed under Byzantine rule and was revised in the 9th century AD through cultural contact with the Muslim world.

place

The Byzantine Hagia Sion Church on the southwest hill of Jerusalem was considered the site of Pentecost in the late 4th century. It drew other traditions over time, including those of the Upper Room (6th century), the Dormition of Mary (7th century), the Flagellation Pillar (7th century) and that of the Tomb of David (10th / 11th centuries) . The crusaders replaced the dilapidated Hagia Sion with a (largely) new building, the Church of Sancta Maria in Monte Sion.

interpretation

Biblical-Jewish roots

In the Tanakh (Hebrew Old Testament) the common meal has a high status as a cult activity. It is central to the usual hospitality in the whole of the Orient : Whoever receives a traveler who serves his needs, shares his bread with him and thus grants him protection, blessings and help like a member of his own family (e.g. Gen 18.1– 8 EU ).

With a meal in the witnessed presence of God, the leaders of the Israelites sealed and affirmed the covenant of YHWH with Israel ( Ex 24.1–11 EU ) on Mount Sinai :

“Moshe took half of the blood and put it in a basin, but he sprinkled the other half of the blood on the altar, took the Book of the Covenant and read it to the people. They said: 'Whatever the Eternal has spoken, we will do and obey.' Moshe took the blood, sprinkled it on the people, and said: 'This is the blood of the covenant which the Eternal made with you over all these words.' Moshe, Aharon, Nadaw, Awihu and seventy of the oldest Yisrael went up. They saw the appearance of the god Yisrael. ... They saw the appearance of God, ate and drank. "

In Gen 31.46 EU , Jacob and Laban made a contract and ate. And in Ex 18.12 EU Jitro converted to the God of Israel and prepared a meal for the glory of God for all the elders of Israel “before the face of God”.

In Psalm 22 EU , the appellative complaint of the unjustly suffering Jew, the unexpectedly rescued from mortal distress celebrates an offering of thanks as a communion meal (Hebrew toda ), which includes a promise for all the oppressed (v. 22): “The bowed down and satisfied will be eaten become."

In the prophecy in the Tanakh , the common meal is a common image for the eschatological shalom of God with his people and the peoples (peace, salvation , redemption ), for example in Isa 25,6ff EU . This Feast of Nations is also typologically linked to the Federal Supper of Israel (24.23 EU ).

The Lord's Supper as a Passover meal

When asked whether the Lord's Supper was a Passover meal, two different answers are possible, depending on whether the synoptic or the Johannine chronology is used ( → see above dating ). According to the synoptic chronology, the Lord's Supper was a Passover meal (which was always celebrated on the evening of Nisan 14, the eve of Passover), so Jesus was crucified on Nisan 15, the feast day of Passover. The Gospel of Luke in particular emphasizes several times that the Lord's Supper was a πάσχα / Pascha (meal) before his arrest. According to the Johannine chronology, however, the 14th Nisan was already the day of the crucifixion, which means that the Lord's Supper would not have been a Passover meal according to the Jewish calendar.

Today, the latter is usually viewed as historically more likely (→ see state of research below ) on the grounds that the trial and execution of Jesus hardly took place on the Passover feast day itself (15th Nisan), especially since Mk 14.2 EU and Mt 26 , 3 Noting EU , contrary to their own chronology, that Jesus should be executed before the feast; that the understanding of the Lord's Supper as the Passover Supper is not found in the initiation texts themselves, but only in the framework narratives, and that they may be motivated there by the efforts of the synoptics to interpret Jesus' Lordship theologically as the new Passover meal (although the Johannine chronology also contains a symbolic interpretation: Jesus dies as the “Lamb of God” [[[Gospel according to John | Joh ]] 1.29.36 EU ; Joh 19.36 EU ], while the lambs are slaughtered in the temple for the Passover meal). - On the other hand, Shalom Ben-Chorin wanted to maintain in his book of Jesus from a Jewish perspective “that the setting up of the so-called Last Supper fits organically into the Seder celebration and is to be seen as an individual interpretation of this ritual by Jesus.” He believed the chronological difficulties to be able to solve by the assumption that Jesus followed the Qumran calendar and held his Seder celebration one day before the official Jewish date. - But even if the Lord's Supper was not a ritual Passover meal, it was certainly “overshadowed by the Passover idea” ( Hans Küng ) and thus at least atmospherically close to the ritual of the Seder celebration.

At the center of the celebration was a festive lamb dish at the time of Jesus, as it is today at the Samaritan Passover (and in contrast to today's Jewish Seder). Tanach and early Jewish literature older than the New Testament give an impression of what was significant at this feast - both for Jesus and the disciples as well as for the evangelist and his readers.

Passover celebrations mark important new beginnings in the history of Israel (Exodus 12: Exodus from Egypt; Joshua 5: Entry into the Promised Land; 2 Kings 23: Renewal of the Covenant; Ezra 6: Inauguration of the Second Temple). Cultic purity is an important requirement for the celebration (the Passover itself has no purifying or atoning meaning). But attending the Passover meal provides protection. This is evident in Exodus 12 and is particularly emphasized in the retelling of the Book of Jubilees (Jub 49, 13:15). Both new beginnings and protection are significant in the situation of Jesus shortly before his arrest, while the Evangelist Luke is not interested in questions of purity.

Last Supper and Seder Evening

As long as the Jerusalem temple existed, the common consumption of the sacrificial animal in Jerusalem was the main content of the celebration. It is therefore not known how Jews in the diaspora celebrated Passover, for example in Corinth, and not even whether they did it at all. Only after the failure of the Bar Kochba uprising, when it became clear that the temple would be destroyed in the long term, did the rabbis in Palestine develop a replacement for the previous Passover ritual. Based on the course of a Hellenistic banquet, which includes a table talk, a doctrinal talk about texts of the Torah and symbolic dishes was suggested. This table talk is still spontaneous at the time of the Mishnah . In addition, in Palestine in the 2nd / 3rd Century AD "there were considerably more Jews than sympathizers of the rabbis." Only in the course of later centuries did the Seder evening take on its classical form. Similarities between the Seder and Christian meal celebrations arose through "the participation of both in the culture of the Greek banquet."

End time celebration of the Jachad

The Dead Sea Scrolls contain rules for an "end-time banquet" of the Jachad . The priest blessed bread and wine; then the Messiah should be the first to eat of the bread. It is unclear, however, whether this liturgical meal should replace the sacrifices in the Jerusalem temple , which was considered defiled because of the Roman occupation and the collaboration of the temple priests (according to David Flusser ). According to Daniel Stökl Ben Ezra, a reference to the temple ("Templarization") can be made for various reasons, without the meal having to be understood as a sacrificial meal or even as a substitute for temple rituals.

Reconstruction of an original form

Joachim Jeremias . accepted as one of the first exegetes in the 20th century that behind the reports of the Synoptics and Paul there was an archetype that goes back to Jesus himself and that was expressed in the liturgy of the early Jerusalem community after his death. Today the majority of exegetes follow him in this regard

According to Jeremias, it contained common motifs in the meal reports:

- According to Jeremias, Jesus' Lord's Supper took place as part of a Passover meal. The disciples are sent to prepare the Passover lamb ( Ex 12.3–6 EU ) at a predetermined location in the capital ( Mk 14.12–16 EU ). The meal is thus under the sign of the memory of God's act of liberation for his people Israel. - As a precaution, Jeremias emphasizes "that the Passover atmosphere surrounded Jesus' last meal even if it should have taken place on the evening before Passover."

- The storyline also includes the betrayal of Judas Iscariot , with which Jesus' passion begins.

- Jesus took on the role of the Jewish housefather, who takes the unleavened flatbread in his hand, thanks God for it - with the beracha at the beginning of every meal: "Blessed are you, Lord our God, King of the world, who brings bread out of the earth" -, breaks the bread into pieces and hands it to those present.

- The cup with wine corresponded to the third blessing cup at a Passover meal, which was served after the meal.

- As they ate and drank, Jesus interpreted the event. According to Jeremias in the original form according to Mk in the Hebrew sacred language, the word bread and cup are זֶה בְשׇׂרֽי (zäh b e śari / dies - my body!) And זֶה דׇמֽי (tough dami / dies - my blood!); or in Aramaic colloquial language דֵּן בִּשְׂרִי (den biśri / dies - my body!) and דֵּן אִדְמִי (den ìdmi / dies - my blood!) (each without the copula ἐστίν /, for which there is no equivalent in Hebrew and Aramaic).

Others (like Heinz Schürmann ), however, found the (even less parallelizing) version of Luke (and Paul) to be closer to the original wording than that of Mark.

Günther Schwarz saw in the present translation "is" a mistranslation from the Aramaic:

“Because the ambiguous Aramaic word here means happening and not is . Precisely this , however, offered the opportunity to sacramentally interpret the pair of words flesh and blood (this is my flesh / blood), instead of, as Jesus meant it, the breaking of bread and the shedding of wine (this becomes my flesh / blood happen) . "

The question of an original form of the Lord's Supper is of course put into perspective if it is not directly attributed to Jesus himself, but rather as a post-Easter congregation formation and interpretation of the Lord's Supper (→ see below: Interpretation of formal history ; state of research ) : It is then no longer about the “ipsissima vox” (the original words) of Jesus in the Upper Room, but rather the earliest (certainly already varied) forms of church tradition of worship. Such a theory is rarely postulated in today's research.

Meaning of the individual motifs

- “Body” (Greek σῶμα, soma , Aramaic בָּשׇׂר, baśar, actually “meat”; not גוּף, guph) in Hebrew usage denotes “both the body and [...] the whole person, the personality”; a separation of body and soul is alien to Judaism. - As the “body of Christ” (σῶμα Χριστοῦ / sōma Christoū), the Christian community is also referred to in the Pauline letters (e.g. 1 Cor 12.27 EU ) and is expressly related to the bread of the Lord's Supper.

- "Blood" (Greek αἷμα, haima, Aramaic דְּמׇא, d e ma) is the carrier of life in the Hebrew understanding, in the New Testament "blood of Christ" is a "formulaic expression" for "Christ's death in its salvation meaning" (Josef Schmid). In the texts of the Lord's Supper it stands for the violent death of Jesus (bloodshed = killing) and, as the pair of terms body - blood, refers to the two components of the sacrificial animal that are separated during the killing. In the Lord's Supper reports, Jesus transfers “terms of the sacrificial language to himself” and speaks “most likely of himself as the Passover lamb” with which the Israelites coated their door posts on the night of the exodus in order to be spared God's avenging angel.

- “Given” ( Lk 22.19 EU only ) is an old (pre-Pauline) formula of faith ( Gal 1.4 EU ; Rom 8.34 EU ). The Greek verb παραδιδόναι (paradidonai) is the Hebrew word for "surrender" and is reminiscent of Jesus' suffering Announcements ( Mk 9,31 EU parr): "The Son of Man will be delivered into the hands of the people."

- The “covenant” (Hebrew בְּרִת, b e rith; Greek διαθήκη, diathḗkē) between God and his people is a central theme in the Bible, because it “sums up the essence of the religion of the Old and New Testaments” ( Johannes Schildenberger ). The two strands of the Lord's Supper tradition take it up in different ways: “With Markus / Matthew the idea is rooted in the old Sinai covenant, which was sealed by the 'covenant blood' of the sacrificial animals ( Ex 24.8 EU ); but this is replaced by his own blood in the covenant establishment of Jesus in the Upper Room […] In the Lukan-Pauline traditional figure, the memory of the prophecy of the eschatological 'new' covenant of God according to Jer 31: 31-34 EU is immediately awakened. Jesus' words then reveal that this promised covenant of God is now being realized due to his bloody death and is effective for the meal participants ”( Rudolf Schnackenburg ). That “new covenant” according to Jer 31 is a renewal, internalization and expansion of the old one.

- “… Shed” (ἐκχυννόμενον, ekchynnómenon) belongs to the victim terminology with “blood”.

- "... for many" (ὑπὲρ / περὶ πολλῶν, hypèr / perì pollōn, in Mk / Mt; in Paulus / Luke instead "for you") is, as Joachim Jeremias has pointed out, a Semitism and refers to the "many" ( Hebrew רַבִּים, rabbim) from the God's servant song Isa 53,11-12 EU . With and without an article it has an inclusive sense, i.e. This means that it includes “the totality” of Jews and Gentiles, thus interpreting Jesus' death as a salvation death for the nations (cf. Mk 10.45 EU ). - In contrast to this view, attempts have recently been made from a Catholic-conservative point of view to show that πολλοί (polloí) is to be understood in a restrictive way and has exactly the same meaning as the German “many” - not “all”.

- "... for the forgiveness of sins" (only with Mt): This formula refers to an early Christian (consequential!) Model of interpretation of the death of Jesus, according to which he died "for our sins" ( 1 Cor 15 EU ) - the idea of an atonement theology becomes increasingly questioned.

- The meaning of the so-called "declaration of renunciation" (Jeremias) "Amen, I tell you ..." is only understandable as an eschatological interpretation of the Lord's Supper against the background of the expectation of the imminent coming of the " Kingdom of God " (βασιλεία τοῦ Θεοῦ, basileia tou theou). In the mouth of Jesus the term of the kingdom of God or the rule of God means “always the eschatological kingship of God” (Schnackenburg), which does not have a spatial, but (like the Hebrew מַלְכוּת, malchuth) a dynamic meaning and must be understood here temporally: “... if God will have established his rule ”.

- The Pauline-Lukan version contains the repetitive command “Do this ... in memory of me!” Here, “memory” (ἀνάμνησις, anámnesis) in biblical usage - as well as in the Jewish domestic Passover liturgy (there זִכׇּרו֗ן, cicaron) - means about the pure Remembering a “sacramental visualization” and at the same time “anticipation and pledge of future perfect salvation” ( Herbert Haag ).

The historical interpretation as a cult legend

In the context of his formal-historical investigations, Rudolf Bultmann concluded from an analysis of the Mk text ( Mk 14,22-25 EU ) that Jesus' words about bread and wine were a “ cult legend from Hellenistic circles in the Pauline sphere” and had superseded an older report of the Passover meal , which in Lk 22.14–18 EU (without 19–20, according to Bultmann interpolated ) is even more complete, but as a biographical legend is probably not historical either. Possibly (this, of course, only as an "uncertain hypothesis") was "originally [...] told how Jesus expressed the certainty at a (solemn, the last?) Meal that he would celebrate the next (joyful) meal in the kingdom of God, this is expected to be imminent. "

Bultmann's student Willi Marxsen developed this approach further with the thesis that the early Christian tradition of the Lord's Supper gradually reflected and interpreted what was initially more simply practical when the early community simply continued the meal communities of Jesus (plural!) After Easter joyful awareness of being the eschatological congregation of the eschatological age and having its Lord with him as the living one gradually developed. Thus, not only a (pre-Pauline) complete satiation meal - framed by the word of bread and the word of the cup - had become a division of meal and final sacramental Lord's Supper (Corinthian practice according to Paul), which then consequently became completely independent; Above all, there has also been a change in the interpretation of the words of the Lord's Supper: In the original version already adopted by Paul ( 1 Cor 11 : 23-25 EU ), the word from the chalice does not yet mean the contents of the chalice (the wine), but the fulfillment of the Mahles: "Of this - circling - chalice it is said: This is the καινὴ διαθήκη [kainḕ diathḗkē] (the new covenant) [...] In this participation in the chalice, the celebrating community has a share in the καινὴ διαθήκη (the new covenant) [... ] (as it is added interpretively) on the basis of the blood of Christ, that is, by virtue of his death ”. Likewise, the bread word originally does not mean an element (bread), but, like 1 Cor 10:16 EU , mean κοινωνία (koinonía / participation) in the σῶμα Χριστοῦ (sōma Christoū / body of Christ). “The community is constituted at the meal. This community is called the καινὴ διαθήκη (the new covenant) or the body, namely the body of Christ. Both are factually the same, one time Jewish, the other time Hellenistic. ”The fact that the focus was then shifted from the execution of the Lord's Supper to the elements of bread and wine (as can be clearly seen in Mark) is due to the Hellenistic world of ideas. where - unlike in Judaism - the divine is thought of as materially mediated; there is therefore a “Hellenistic interpretation of the originally Palestinian meal”. “If a sentence in the report of the Lord's Supper goes back to Jesus himself, it is the sentence, which was no longer adopted by Paul in the later liturgical tradition, that Jesus will no longer drink the plant of the vine until the day when he will drink it again in the kingdom of God "(H. Küng / Mk 14.25 EU ). This eschatological (eschatological) alignment of the Lord's Supper with the coming kingdom of God was particularly emphasized by Albert Schweitzer in the course of his “consistent eschatology ”: “The constituent elements of the celebration were not the so-called words of Jesus' institution of bread and wine as his body and blood, but rather the prayers of thanksgiving about bread and wine. These gave both the evening meal of Jesus with his disciples and the meal of the early Christian community a meaning to the expected messianic meal [...] At the last earthly meal he consecrates them [= the disciples] as his companions at the coming messianic meal Thanksgiving celebrations (εὐχαριστία, eucharistía, Eucharist ) for the soon-awaited kingdom and return of Christ ( Parousia ), the first Christians then held their meal celebrations in continuation of the Lord's Supper, without Jesus expressly ordering this. His interpretative words about bread and wine, spoken in view of his death, only became words of consecration in the course of the later de-chatologization of Christianity (the loss of the expectation of an imminent return of Christ - parousia delay), with which the two elements were transformed as holy food in the body and blood of Christ become; in the process, the meal celebration gradually became a mere distribution celebration.

Breaking bread / Lord's meal in early Christianity

→ cf. see above The interpretation of the history of form .

The common meal was of central importance in early Christianity . Acts 2,42 EU names "breaking bread" as one of the four characteristics of Christian community ( koinonia ). The expression is reminiscent of Jesus' distribution of bread in the synoptic reports of the Lord's Supper. It is therefore believed that the early Christians celebrated a meal that was to commemorate Jesus' death and resurrection and to prepare for his second coming .

The Acts of the Apostles mentions daily meals together in private homes and contrasts them with public gatherings in the temple ( Acts 2.46 EU ); it is not clear from this formulation whether daily celebrations of the Eucharist are meant. At the so-called love meal ( agape ) food was also distributed to the needy. After there were grievances in Corinth from his point of view, Paul recommended his congregation to separate the common “Lord's Supper” in the service from the satiation meal in their own house ( 1 Cor 11 : 17–34 EU ). This initiated a separation of the sacred from the profane meal, which is atypical for Jewish Christians . On the other hand, Paul affirmed the Lord's Supper as a self-evident and indispensable church event.

Soon the agape celebration was distinguished from the Lord's Supper, but not entirely separate. Probably the congregation celebrated the Eucharist ( Acts 20.7 EU ) at least on the first day of the week, the "Day of the Lord" , integrated into a common meal ( 1 Cor 11.21 EU ; 11.33 EU ). It probably took place on Sunday evening: The Greek word used for "meal" (δεῖπνον, deipnon ) describes a festive meal at the end of the day. There is some evidence that - similar to the Passover meal - God's salvation history was recalled and proclaimed. The passion story of Jesus was in the foreground ( 1 Cor 11:26 EU ).

A special priestly service cannot be derived from the New Testament reports on the Lord's Supper. In 1 Tim 3.1 to 10 EU is bishops and deacons awarded no special role in the "administration of the sacraments." According to Tit 1,7 EU the bishops administer the "house of God"; Whether this included a special administration of the sacraments cannot be inferred from the text.

References to the Lord's Supper in other biblical texts

Paul writes in the 10th and 11th chapters of First Corinthians about the practice of the Lord's Supper in Corinth . The breaking of bread in the early church in Jerusalem is mentioned in Acts 2,42–46 EU .

In some Easter texts, the resurrected one holds a meal with his disciples, which is reminiscent of the sacrament practice:

- Lk 24 : 13–35 EU : The Emmaus disciples recognize Jesus “when he broke the bread”.

- Joh 21,1–13 EU : Jesus reveals himself to seven of his disciples at the Sea of Galilee and has a meal with them.

Other meal texts in the Gospels are also often related to the Lord's Supper and sometimes even suggest this reference in their formulations. A connection between the feeding stories (feeding the four or five thousand) and the Eucharist is not admitted by all exegetes, but some regard this episode as the starting point of an alternative or the actual Lord Supper tradition.

A feminist-theological perspective

Angela Standhartinger suspects that the words of institution represent a narrative fragment from ritual laments for the dead that were sung by women. Initially, in the 1st century there were no clearly defined liturgists for pronouncing the words of institution. Standhartinger then uses letters of condolence from ancient women to show that they understood it to be their religious and social duty to lament for the dead. Laments remembered in song form to suffering and death of the deceased, including the supply of might suit Psalms Ps 22 EU and 69 EU be understood in the Markan and Johannine Passion narratives. The first-person speech in the words of institution finds its parallel in the fact that the deceased is usually spoken in the first person in lamentations or funerary inscriptions from antiquity. According to this, the words of the bread and the chalice could also be statements that the crucified one addressed to those who remained in the mouth of a sounding person. It is summed up, "that lamentations sung by women offer a form in which the words of institution could have sounded in the context of dramatically portrayed Passion stories."

Summary of New Testament Research

Regarding the last supper of Jesus, different accents and reconstructions of the gestures and words of Jesus are represented in research. Xavier Léon-Dufour summarized the status of the discussion (1993) in the Lexicon for Theology and the Church as follows:

- The specialty of the action goes back to Jesus of Nazareth ( Heinz Schürmann ). Paul is witness to a tradition that goes back to the year 40/42 (or 35). There is not enough time to spread a legend ( Willi Marxsen ). The report does not refer to the apparition meals e.g. B Lk 24.30 ( Oscar Cullmann ), still on the pre-Easter meals of Jesus z. B Lk 14.21 / Mk 2.15 ( Ernst Lohmeyer ), but rather on the last meal before his death. The etiological form does not contradict the reality of the act, which goes back to the historical Jesus.

- The words essentially go back to Jesus. There is agreement on this for Mark 14.25 EU and the word of bread. The same does not necessarily apply to the second (cultic) word about the chalice. It represents an additional repetition compared to the other word from the cup (Mk 14.25). That is why a large part of today's exegetes are skeptical. Nevertheless, there are also numerous exegetes here who consider it more likely that the second word about the cup goes back to Jesus himself: Thomas Söding , Knut Backhaus , Ulrich Wilckens , Peter Stuhlmacher .

The Jesus Handbook (2017) presents research on Jesus based on the current state of international discussion. In the chapter there about the last supper of Jesus, Hermut Löhr summarizes: The covenant idea that characterizes the interpretive words cannot be localized in the rest of the Jesus tradition. This is also not to be associated with the coming of the kingdom of God (Vogel 1996: 88–92). This conspicuousness speaks rather against the thesis that only the post-Easter Church took up this covenant idea and entered it into the tradition of Jesus' last meal. Thus Jesus would have interpreted and pronounced the covenant in the context of the last supper during the "circling of the cup".

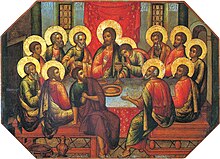

The last supper in art

The Lord's Supper with his disciples was repeatedly taken up in artistic representations.

There is a tradition in Italian Renaissance monasteries to decorate the refectory with a fresco of the Last Supper. The most famous such painting of a monastic dining room is The Last Supper (Cenacolo) by Leonardo da Vinci . It was quoted and alienated in various forms right up to the modern age. Further examples:

- Sant 'Apollonia, Florence ( Andrea del Castagno )

- Ognissanti, Florence ( Domenico Ghirlandaio )

- Fuligno, Florence ( Pietro Perugino )

In Orthodoxy , artistic representations of Jesus' Last Supper (e.g. in frescoes or as icons ) are referred to as "Apostle Communion ".

literature

- Willibald Bösen : The last day of Jesus of Nazareth. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1995 3 , ISBN 3-451-23214-6 .

- Rupert Feneberg : Christian Passover and Last Supper: a biblical-hermeneutical examination of the New Testament institution reports . Kösel, Munich 1971, ISBN 3-466-25327-6 (= Studies on the Old and New Testament . Volume 27).

- Hartmut Gese : The origin of the Lord's Supper. In: On Biblical Theology. Old Testament Lectures. Kaiser, Munich 1977, ISBN 3-459-01098-3 , pp. 107–127 (on the Old Testament background of the Last Supper).

- Bernhard Heininger: The last meal of Jesus. Reconstruction and interpretation . In: Winfried Haunerland (Ed.): More than bread and wine. Theological contexts of the Eucharist (= Würzburg Theology 1). Echter, Würzburg 2005, ISBN 3-429-02699-7 , pp. 10-49.

- Judith Hartenstein: Last Supper and Passover. Early Jewish Passover traditions and the narrative embedding of the words of institution in the Gospel of Luke . In: Judith Hartenstein et al .: "An ordinary and harmless dish"? From the developments of early Christian sacrament traditions . Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Göttingen 2008. ISBN 978-3-579-08027-7 , pp. 180-199.

- Joachim Jeremias : The Lord's Supper. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1967 4 (1935 1 ), DNB 457097620 .

- Hans-Josef Klauck : Lord's meal and Hellenistic cult. Aschendorff, Münster 1998 2 , ISBN 3-402-03637-1 .

- Hermut Löhr: Origin and meaning of the Lord's Supper in earliest Christianity. In the S. (Ed.): Last Supper ( Topics of Theology 3). UTB / Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2012; ISBN 978-3-8252-3499-7 ; Pp. 51-94.

- Clemens Leonhard: Easter - a Christian Pesach? Similarities and differences . In: World and Environment of the Bible No. 40, 2/2006, pp. 23-27.

- Christoph Markschies : Ancient Christianity: piety, ways of life, institutions . CH Beck, Munich 2012 2 , ISBN 978-3-406-63514-4 .

- Rudolf Pesch : The Last Supper and Jesus' understanding of death ( Quaestiones disputatae 80). Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau [a. a.] 1978, ISBN 3-451-02080-7 .

- Rudolf Pesch: The Acts of the Apostles ( EKK Volume V). Neukirchener Verlagsgesellschaft and Patmos Verlag, study edition 2012.

- Jens Schröter : The Last Supper. Early Christian interpretations and impulses for the present ( Stuttgarter Bibelstudien 210). Catholic Biblical Works, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-460-03104-2 .

- Heinz Schürmann : The Lord's Supper report Luke 22: 7–38 as an order of worship, congregation order, order of life . ( The message of God: New Testament row 1). St. Benno, Leipzig 1967 4 , DNB 364609907 .

- Herrmann Josef Stratomaier: Last Supper, Origins and Beginnings. Tectum-Verlag, 2013

- Josef Zemanek: The interpretive words in the context of the Old Testament. B & B-Verlag, 2013

- Walter Kasper , Walter Baumgartner , Karl Kertelge , Horst Bürkle , Wilhelm Korff , Peter Walter , Klaus Ganzer : Last Supper, Last A. Jesu . In: Walter Kasper (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 30-35 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau.

Web links

- Gerd Häfner : The tradition of Jesus' last meal. Repetition for student teachers for the lecture Work and Mission of Jesus - Basics of the Message of the NT . Online publication, LMU Munich , winter semester 2011/12.

- Karin Lehmeier: Last Supper. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart, September 20, 2018.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Christoph Markschies: The ancient Christianity . S. 174 .

- ↑ Christoph Markschies: The ancient Christianity . S. 111 .

- ^ Daniel J. Harrington: The church according to the New Testament. 2001, ISBN 1-58051-111-2 , p. 49.

- ↑ The definite article “that” - here as a demonstrative pronoun, literally “this” - is a neuter in the Greek for Paul and the Synoptics, while “bread” is masculine there. Some translations, for example into German or English, hide this grammatical difference. Ulrich Luz: The Gospel according to Matthew , Volume 4, Düsseldorf / Neukirchen-Vluyn 2002, p. 112, note 84

- ↑ Matthias Kamann: Why theologians doubt Jesus' atoning death. In Die Welt , March 28, 2009; accessed on January 15, 2017.

- ↑ Helmut Hoping: My body given for you - history and theology of the Eucharist 2., exp. Ed., Herder, Freiburg i. B. 2015, p. 33 f.

- ^ A b c Paul F. Bradshaw: Reconstructing Early Christian Worship. SPCK , London 2009, ISBN 978-0-281-06094-8 , pp. 3 f.

- ↑ Helmut Hoping: My body given for you - history and theology of the Eucharist 2., exp. Ed., Herder, Freiburg i. B. 2015, pp. 48-53.

- ↑ Klaus-Michael Bull: The Gospel of John (Joh). In: Biblical Studies of the New Testament on Bibelwissenschaft.de. Retrieved October 31, 2019 .

- ↑ Hartmut Bärend: Bible study on John 21: 1–14 at the 4th theological congress of AMD in Leipzig. (doc; 71 kB) AMD , September 20, 2006, p. 11 , archived from the original on October 23, 2007 ; accessed on March 30, 2018 .

-

^ Paul William Barnett: Jesus & the Rise of Early Christianity: A History of New Testament Times . InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove (Illinois), 1999, ISBN 0-8308-1588-0 , pp. 19-21.

Rainer Riesner : Paul's early period: chronology, mission strategy, theology . Grand Rapids (Michigan); Eerdmans, Cambridge (England), 1998, ISBN 0-8028-4166-X , pp. 19-27. P. 27 provides an overview of the different assumptions of various theological schools.

Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum: The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament . B & H Academic, Nashville (Tennessee), 2009, ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 , pp. 77-79. - ↑ Colin J. Humphreys: The Mystery of the Last Supper . Pp. 62-63.

- ^ Humphreys: The Mystery of the Last Supper . P. 72; 189

- ↑ Francis Mershman (1912): The Last Supper . In: The Catholic Encyclopedia . Robert Appleton Company, New York, retrieved on May 25, 2016 from New Advent.

- ^ Jacob Neusner: Judaism and Christianity in the first century . Volume 3, Part 1. Garland, New York, 1990, ISBN 0-8240-8174-9 , p. 333.

- ^ Pope Benedict XVI: Jesus of Nazareth: From the Entrance Into Jerusalem to the Resurrection . Catholic Truth Society and Ignatius Press, 2011, ISBN 978-1-58617-500-9 , pp. 106-115. Excerpt from the website of the Catholic Education Resource Center ( Memento of July 13, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Humphreys: The Mystery of the Last Supper . Pp. 164, 168.

- ↑ Nagesh Narayana: Last Supper was on Wednesday, not Thursday, challenges Cambridge professor Colin Humphreys . International Business Times , April 18, 2011, accessed May 25, 2016.

- ↑ Based on Humphreys 2011, p. 163.

- ↑ Humphreys 2011, p. 143.

- ^ Number of Samaritans in the World Today. In: The Samaritan Update. August 29, 2019, accessed October 31, 2019 .

- ^ Günter Stemberger: Jews and Christians in the Holy Land . Munich 1987, p. 175 .

- ↑ Sylvia Powels: The Samaritan Calendar and the Roots of Samaritan Chronology . In: Alan David Crown (ed.): The Samaritans . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1989, p. 699 (The oldest Samaritan calendar script covers the period from 1180 to 1380 AD (ibid., P. 692)).

- ↑ W. Gunther Plaut (ed.), Annette Böckler (arrangement): Schemot = Shemot = Exodus . Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh, 3rd edition, 2008, ISBN 978-3-579-05493-3 , pp. 270-272.

- ↑ Helmut Löhr: The Last Supper as a Pesach meal. Considerations from an exegetical point of view based on the synoptic tradition and the early Jewish sources . In: BThZ . 2008, p. 99 .

- ^ Günther Bornkamm : Jesus of Nazareth. Urban books, W. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart (1956) 6th edition 1963, pp. 147-149.

- ↑ Shalom Ben-Chorin: Brother Jesus . In: dtv 30036 (1977) . 4th edition. 1992, ISBN 3-423-30036-1 , pp. 127 .

- ↑ Shalom Ben-Chorin: Brother Jesus . In: dtv 30036 (1977) . 4th edition. 1992, ISBN 3-423-30036-1 , pp. 132 .

- ↑ Hans Küng: Being a Christian . Piper, Munich 1974, ISBN 3-492-02090-9 , pp. 314 .

- ^ Judith Hartenstein: Last Supper and Passover . S. 189 .

- ^ Judith Hartenstein: Last Supper and Passover . S. 189-190 .

- ↑ Clemens Leonhard: Easter - a Christian Pesach? S. 26 .

- ↑ Clemens Leonhard: Easter - a Christian Pesach? S. 27 .

- ^ Daniel Stökl Ben Ezra: Qumran. The Dead Sea Texts and Ancient Judaism . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2016, p. 297 .

- ↑ David Flusser: The Essenes and the Lord's Supper. In: David Flusser: Discoveries in the New Testament, Volume 2: Jesus - Qumran - Early Christianity. Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn 1999, ISBN 3-7887-1435-2 , pp. 89-93.

- ^ Daniel Stökl Ben Ezra: Qumran . S. 298 .

- ↑ Joachim Jeremias: The Last Supper of Jesus. Göttingen 3rd edition 1960

- ↑ Helmut Hoping: My body given for you: History and theology of the Eucharist . Ed .: Helmut Hoping. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 2013, p. 35 .

- ↑ Joachim Jeremias: The Last Supper of Jesus. Göttingen 3rd edition 1960, p. 82.

- ↑ Joachim Jeremias: The Last Supper of Jesus. Göttingen, 3rd edition, 1960, p. 194; on the alternative Hebrew - Aramaic original form pp. 189–191.

- ^ Heinz Schürmann: Deployment reports . In: Josef Höfer , Karl Rahner (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 2nd Edition. tape 3 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1959, Sp. 764 .

- ↑ Günther Schwarz (Ed.): The Jesus Gospel. Ukkam, Munich, 1993, ISBN 3-927950-04-1 , p. 384.

- ↑ Joachim Jeremias: The Last Supper of Jesus. Göttingen 3rd edition 1960, pp. 181-183.

- ↑ Helmut Hoping: My body given for you: History and theology of the Eucharist . 2nd Edition. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 2013, p. 26 .

- ↑ Joachim Jeremias: The Last Supper of Jesus. Göttingen 3rd edition 1960, p. 191f, vs. Dalman

- ↑ Josef Schmid : Body . In: Josef Höfer , Karl Rahner (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 2nd Edition. tape 6 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1961.

- ↑ Josef Schmid: Art. Blood of Christ. In: Johannes B. Bauer (Ed.): Bibel Theological Dictionary. Verlag Styria, Graz, 2nd edition 1962, Vol. 1, p. 138.

- ↑ Joachim Jeremias: The Last Supper of Jesus. Göttingen, 3rd edition 1960, pp. 213–215.

- ↑ Detlev Dormeyer: Death of Jesus. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (eds.): The scientific Bibellexikon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart September 20, 2018., accessed on October 31, 2019.

- ^ Johannes Schildenberger: Bund. In: Johannes B. Bauer (Ed.): Bibel Theological Dictionary. Styria, Graz, 2nd edition 1962, vol. 1 p. 150.

- ↑ Rudolf Schnackenburg: God's rule and kingdom. Herder Freiburg / Basel / Vienna, 3rd edition 1963, p. 175.

- ^ Johannes Schildenberger: Bund. In: Johannes B. Bauer (Ed.): Bibel Theological Dictionary. Verlag Styria, Graz, 2nd edition 1962, Vol. 1, pp. 155f.

- ↑ Joachim Jeremias: The Last Supper of Jesus. Göttingen 3rd edition 1960, p. 213.

- ↑ Joachim Jeremias: The Last Supper of Jesus. Göttingen 3rd edition 1960, pp. 171–174; 218-223.

- ↑ Franz Prosinger: The blood of the covenant - poured out for everyone? In: kath-info.de. June 29, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2019 .

- ↑ Burkhard Müller: Died for our sins? CMZ-Verlag, Rheinbach 2010, ISBN 978-3-87062-111-7 , p. 55-66 .

- ↑ Joachim Jeremias: The Last Supper of Jesus. Göttingen, 3rd edition 1960, p. 199 Note 6 (correction compared to 2nd edition!).

- ↑ Rudolf Schnackenburg: God's rule and kingdom. Herder Freiburg / Basel / Vienna, 3rd edition 1963, p. 52.

- ↑ Joachim Jeremias: The Last Supper of Jesus. Göttingen, 3rd edition 1960, pp. 174-176.

- ↑ Herbert Haag, Art. Gedächtnis - Biblisch, in: Lexikon für Theologie und Kirche , Vol. 4, 2nd edition 1960, Sp. 570-572

- ↑ Rudolf Bultmann: History of the synoptic tradition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen (1921), 6th edition 1964, pp. 285–287; here digitized version of the 2nd edition .

- ↑ Willi Marxsen: The Lord's Supper as a Christological Problem. Gerd Mohn, Gütersloh 1963/65, p. 21.

- ↑ Willi Marxsen: The Lord's Supper as a Christological Problem. Gerd Mohn, Gütersloh 1963/65 p. 18f.

- ↑ Willi Marxsen: The Lord's Supper as a Christological Problem. Gerd Mohn, Gütersloh 1963/65 p. 8f

- ↑ Willi Marxsen: The Lord's Supper as a Christological Problem. Gerd Mohn, Gütersloh 1963/65 p. 11.

- ↑ Willi Marxsen: The Lord's Supper as a Christological Problem. Gerd Mohn, Gütersloh 1963/65 p. 12f

- ↑ Willi Marxsen: The Lord's Supper as a Christological Problem. Gerd Mohn, Gütersloh 1963/65 p. 24.

- ↑ Hans Küng: Being a Christian . Piper, Munich 1974, ISBN 3-492-02090-9 , pp. 313 .

-

↑ Albert Schweitzer: The Last Supper problem based on the scientific research of the 19th century and the historical reports. JCB Mohr, Tübingen, 1901.

Albert Schweitzer: History of the life of Jesus research (1906/1913), Siebenstern-Taschenbuch 77/78 and 79/80, 1966, p. 433 u.ö. - ↑ Albert Schweitzer: From my life and thinking . In: Fischer Taschenbuch 5040 (1952) . 1983, ISBN 3-596-25040-4 , pp. 31, 35 .

- ↑ Albert Schweitzer: The mysticism of the apostle Paul . In: Uni-Taschenbücher 1091 . JCB Mohr, Tübingen 1981, ISBN 3-16-143591-5 , pp. 235-238 .

- ↑ Rudolf Pesch: The Acts of the Apostles . S. 130-131 .

- ↑ Rudolf Pesch: The Acts of the Apostles . S. 131-132 .

- ^ Rudolf Schnackenburg : The Gospel of John. Part II. Herder, Freiburg-Basel-Vienna 1971, p. 21.

- ^ Rudolf Schnackenburg: The Gospel of John. Part II. Herder, Freiburg-Basel-Wien 1971, p. 21, note 2.

- ↑ a b Angela Standhartinger: Inscribing women in history: To the liturgical place of the words of institution . In: Early Christianity . 9F, 2018, pp. 255-274 .

- ^ Xavier Léon-Dufour: Last Supper. Last A>. Jesus. I. In the New Testament . In: Walter Kasper (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 1 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1993, Sp. 30-34 .

- ↑ Xavier Léon-Dufour: Last Supper, Last A. Jesu . In: Konrad Baumgartner, Horst Bürkle, Klaus Ganzer, Walter Kasper, Karl Kertelge, Wilhelm Korff, Peter Walter (eds.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 1 . Herder, S. 30-34 .

- ↑ Thomas Söding: The Lord's Supper. On the shape and theology of the oldest post-Easter traditions . In: BJ Hilberath, D. Sattler (Ed.): Foretaste. Ecumenical efforts for the Eucharist . Mainz 1995, pp. 134-163.

- ↑ Knut Backhaus: Did Jesus speak of God's covenant? In: Theologie und Glaube 86 (1996), pp. 343–356.

- ↑ Ulrich Wilckens: Jesus' death and resurrection and the emergence of the Church from Jews and Gentiles (= Theology of the New Testament . Volume I / 2), 2nd revised edition Neukirchen-Vluyn 2007, therein p. 15ff .: Jesu Tod als vicinité Dedication of life “for many” , p. 54ff .: The Passover Week .

- ↑ Peter Stuhlmacher: Foundation: From Jesus to Paulus (= Biblical Theology of the New Testament . Volume 1), 3rd revised and supplemented edition Göttingen 2005, p. 124ff., Especially p. 134.

- ↑ Sven-Olav Back, Knut Backhaus, Reinhard von Bendemann, Albrecht Beutel, Darrell L. Bock, Martina Böhm, Cilliers Breytenbach, James G. Crossley, Lutz Doering, Martin Ebner, Craig Evans, Jörg Frey, Yair Furstenberg, Simon Gathercole, Christine Gerber, Katharina Heyden, Friedrich Wilhelm Horn, Stephen Hultgren, Christine Jacobi, Jeremiah J. Johnston, Thomas Kazen, Chris Keith, John S. Kloppenborg, Bernd Kollmann, Michael Labahn, Hermut Löhr, Steve Mason, Tobias Nicklas, Markus Öhler, Martin Ohst, Karl-Heinrich Ostmeyer, James Carleton Paget, Rahel Schär, Eckart David Schmidt, Jens Schröter, Daniel R. Schwartz, Markus Tiwald, David du Toit, Joseph Verheyden, Samuel Vollenweider, Ulrich Volp, Annette Weissenrieder, Michael Wolter, Jürgen K. Zangenberg, Christiane Zimmermann, Ruben Zimmermann: Jesus manual . Ed .: Jens Schröter, Christine Jacobi. Mohr Siebeck, 2017, ISBN 3-16-153853-6 , pp. 685 .

- ↑ Guido Fuchs: Mahlkultur: grace and table ritual . Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 1998, p. 146.148 .

- ↑ Holy Communion , in: The large art dictionary by PW Hartmann online, accessed on June 30, 2017.