Pontius Pilate

Painting by Nikolai Nikolajewitsch Ge , 1890: Pontius Pilatus and Jesus according to Joh 18,38

Pontius Pilate was prefect ( governor ) of the Roman emperor Tiberius in the province of Judea from 26 to 36 AD . He was best known through the passion story in the New Testament of the Bible . There it is reported that he sentenced Jesus of Nazareth to death on the cross .

Surname

The first name ( praenomen , see Roman name ) of Pontius Pilatus has not been passed down. His family name (nomen gentile) shows that he came from the Roman family ( gens ) of the Pontier. Members of this family often played a special role in Roman history; for example, one of the Caesar killers came from this family. The third part of the name ( cognomen ) is interpreted differently. Since the name with iota longa is recorded in writing , the syllable was pil- long. It is possible to derive Latin words such as pilum (“spear”) or pila (“pillar”), pilatus would then mean “armed with the pilum” or “planted”. A connection with pileus , the felt cap of the freedmen, is also conceivable and the name may be an abbreviation of Pileatus .

Life

Pilate's year and place of birth are unknown. Since the gentile name Pontius occurs among the Samnites , some scholars have assumed that the family originated from Samnium . In the year 26 Pilate was appointed prefect of Judea at the instigation of Lucius Aelius Seianus , a confidante of the emperor Tiberius . Pilate was the fifth prefect of this part of the province, so it was subordinate to the governor of the province of Syria and succeeded Valerius Gratus , who held the office 15-26 AD. The appointment shows that Pilate belonged to the knighthood ( equester ordo ) .

A Roman prefect was usually appointed by the emperor. During the reign of Tiberius, in fact from the year 21 AD, the commander of the Praetorian Guard , Seianus , had such great influence over Tiberius that he could also influence the appointment of the prefects. The appointment of Pontius Pilate falls exactly at the same time as Tiberius' retreat to Capri . Assumptions that Pilate was deliberately used by the anti-Jewish Seianus to take action against the Jews with violence cannot be proven. Historians often regard Pilate's awkward behavior during his tenure as evidence of his anti-Jewish attitude. It is therefore primarily Jewish sources (and Flavius Josephus in particular ) that emphasize Pilate's harsh administration. Regardless of this discussion, it is remarkable that Pilate was able to administer Judea for at least ten years, which speaks for great assertiveness in one of the most troubled areas of the empire.

An event in the summer of 36 likely resulted in his dismissal. Pilate used brutal force to stop people from Samaria from going up to the holy mountain Garyzim (see History of the Samaritans ). He was then recalled by the Syrian legate , Vitellius , to justify himself to Tiberius. One of the accusations that were made against him was that he had enriched himself with the temple treasures and had a water pipe laid in his house at the expense of the state treasury. Philo of Alexandria lists the following charges: bribery, insults, robbery, violence, licentiousness, repeated executions without trial, constant practice of extremely painful cruelty . Vitellius used Marcellus instead .

Although it is claimed relatively often, especially in the legends about Pilate, there is no evidence whatsoever that he ever had to justify himself to Tiberius for the judgment on Jesus. When Pilate arrived in Rome after his recall, Tiberius was already dead, so it is not known whether there was any legal proceedings against him or what happened to him. With reference to the testimony of pagan chroniclers and Olympiad writers, the church father Eusebius writes at the beginning of the 4th century that Pilate got into such distress under Caligula that he committed suicide in 39 . According to Orosius , the emperor even forced him to do so. Both authors see in it the punishing hand of God. However, in the church tradition before Eusebius there is no news of a suicide by Pilate. Origen , for example, apparently does not know anything about it, because he has to counter the objection of the philosopher Kelsus that Jesus' judges did not suffer anything similar to Pentheus' fate , only that Pilate was not Jesus' judge at all, that the Jews were hit by the curse.

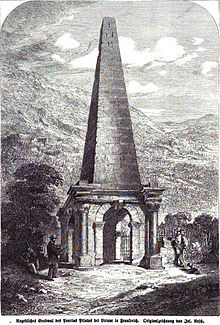

Historically, the legends of Pilate's banishment to Vienne in southern France are even more uncertain . There are also very different information about the year of his death, which have a legendary background rather than historical facts.

Biblical testimonies

Pontius Pilate is known through the Passion stories of the New Testament as the one who sentenced Jesus of Nazareth to death on the cross and had the execution carried out. In addition, Pilate is mentioned twice in the New Testament: the Gospel of Luke ( Lk 13,1–2 EU ) reports on the murder of Galilean pilgrims ordered by him and dates ( Lk 3,1 EU ) the beginning of the appearance of John the Baptist in his time Lieutenancy.

Historical evidence

The most important source outside of the New Testament is a passage in the annals (15, 44) of the Roman historian Tacitus , which reports on the persecution of Christians under Nero after the fire in Rome (64 AD) and mentions Pilate in passing: Auctor nominis eius Christ Tiberio imperitante per procuratorem Pontium Pilatum supplicio adfectus erat. ("The author of that name, Christ, was executed by the procurator Pontius Pilate during the reign of Tiberius.")

In addition, there are reasonably certain historical statements about Pilate, especially in Flavius Josephus' works De bello Judaico and in the Antiquities . Also, Philo of Alexandria reports on him.

Due to the poor sources, it was sometimes even assumed that Pontius Pilate was not a historical person. Since the discovery of the Pilate inscription in 1961 in Caesarea , the former residence of Pilate, its existence is considered certain:

... S TIBERIÉVM / [PO] NTIVS PÌLATVS / [PRAEF] ECTUS IVDAE [A] E / ... É ...

The inscription confirms Pilate's governorship in Judea. According to Alföldy, the Tiberieum , which was renovated by Pontius Pilate, is one of the lighthouses of Caesarea, others associate it with a building of the imperial cult for Tiberius and his mother Livia Drusilla . The find shows that the correct designation for the office exercised by Pilate was prefect and not, as was common with the governors of Judea from the middle of the 1st century, procurator , a designation also used by Tacitus.

In 2018, the inscription on a signet ring that was found during excavations in the Herodium fortress between 1968 and 1969 was deciphered as "by Pilate" during subsequent work. The ring shows a wine vessel ( krater ) in the middle , which is surrounded by the name inscription. Due to the rarity of the name, it is assumed that the ring belonged to Pilate himself or at least to an officer subordinate to him, who could trade it in Pilate's name. The latter option is supported by the fact that the ring is designed rather simply.

Three types of coins are known from Judea, which can be associated with the term of office of Pilate (Hendin type 648, 649, 650). They bear the legend Tiberiou Kaisaros ("of Tiberius Caesar") and also bear the numbers of the respective year of Tiberius' reign, which corresponds to the years 29, 30 and 31 according to the Christian calendar. So they clearly date to the term of office of Pilate. A lituus or a simpulum (ladle) is depicted on the front , both tools of the imperial cult . These images must have injured the religious feelings of the Jews, the extent to which this was done consciously is controversial.

rating

According to the representations of the Gospels, the trial of Jesus fell within the remit of the Roman governor, provided that the charge included high treason and incitement to rebellion, i.e. political offenses. Because, according to the indictment of the Jewish high priests , Jesus made himself the "King of the Jews", he became a threat to the emperor in Rome and his territorial claims. Also because there were signs of a revolt by the Jewish population ( Mt 27.24 EU ), Pilate seemed compelled to pursue the charges. From a scientific point of view, due to their religious context, the Gospels are only suitable for historical appreciation to a limited extent. The great role that, according to the reports of the Gospels, the Jews are supposed to have played in the condemnation of Jesus is traced back to salvation-historical or directly anti-Jewish statements, such as the widespread accusation of the murder of God ("His blood come upon us and our children", Mt 27 , 25 EU ).

However, Pilate is valued differently from a Jewish, Christian and scientific point of view. For Judaism he was the representative of the Roman occupying power. In the New Testament Pilate remains formally responsible for the crucifixion of Jesus, but the people and the Jewish authorities are assigned a greater guilt for the death of Jesus ( Joh 18,33-35 EU ; 19,11 EU ), by making his death on the cross ( crucifige) and demand the release of Barabbas . In contrast, Pilate appears convinced of the innocence of the accused and is looking for a way to release him, which he does not succeed in view of the vehement influence of the Jewish authorities. So Pilate turns away and demonstratively washes his hands based on a motif from Matthew's Gospel ( Mt 27:24 EU ). According to the Gospel of John , Jesus confronts him with the concept of truth ( John 18:37 EU ). Pilate then simply asks “ What is truth? “ ( Jn 18.38 EU ). According to Carl Schmitt , the attitude of Pilate can be interpreted, depending on your point of view, either as an expression of “tired skepticism ”, as agnosticism , as an “expression of superior tolerance ” or as an early case of ideological neutrality of the state and administration . For the Gospel of John, Pilate ultimately fails because of the correct knowledge of Jesus and at the same time proves to be powerless against the Jewish accusers.

The name Pontius Pilatus is also mentioned in the Christian apostolic creed . The lines read in the German translation: "Born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, crucified, died and buried" ( natus ex Maria virgine, passus sub Pontio Pilato, crucifixus, mortuus et sepultus ). Despite this emphasis in the creed, the assessment of Pilate and his judgment is very different in the various churches . Tertullian wrote in the 2nd century, Pilate had his conviction to Christchurch been (iam per sua consciencia Christianus) and in the Coptic Church Pilate is as martyrs venerated ( Memorial Day June 25), he whereas in Western, but also of the Orthodox Church about Since the time of Emperor Constantine, often referred to as deicida ( murderer of God ) and soon became, for example, an evil person par excellence, so that Abraham a Sancta Clara could call him an "arch rogue" in the 17th century.

This ambivalence results from the fact that the judgment of Pilate is not easy for Christians to evaluate: Is it unjust because it led to the death of the Messiah on the cross ? Or did it fulfill God's plan of salvation, whereby Pilate would be God's instrument? The theological-philosophical problem of human responsibility and freedom of will in relation to divine predestination and also the problem of the ethical basis on which Pilate's behavior is to be assessed at all appears here as an example .

The attempted exertion of influence by Pilate's wife as described in the Bible should also be seen in this context ( Mt 27:19 EU ). Although this has no name in the New Testament, the name Claudia Procula (sometimes also: Procla) soon became established for her . Occasionally it is assumed that she is identical to a Claudia who is mentioned in 2nd Timothy ( 2 Tim 4,21 EU ). Her standing up for Jesus is seen by some as a sign that she was his secret follower and therefore wanted to save him, others as the devil's attempt to prevent redemption. The wife of Pontius Pilate is venerated as a saint in the Orthodox Church ; her feast day is October 27th .

As recently as the 17th century, Pilate's responsibility was discussed intensively in theological circles. When the Protestant theologian Johann Steller from Jena, in a book Pilatus defensus (1676), advocated the thesis that Pilate had acted correctly from a legal point of view, his colleagues initiated a formal canonical process for Pilate in which the philosopher Jakob Thomasius was the accuser and steller Defenders appeared.

Legend

Few details are known about the life of the historical Pilate. Legends tried to fill in the gaps. From around AD 100, legends of saints emerged, according to which Pilate converted to Christianity and how his model Christ died on the cross. From about the 4th century onwards, apocrypha with stories about Pilate appeared; the best known are the Epistola Pilati , the Acta Pilati or Mors Pilati . These apocryphal texts by Pilate show how God punishes the murderer of his son; sometimes these texts are headed Vindicta salvatoris (The Redeemer's Revenge).

In the Middle Ages, passion plays were created that deal with Pilate. During this time, Pilatus houses were built in many cities, which - as in Nuremberg, for example - are the first station of a Way of the Cross , or, as in Spain ( Casa de Pilatos in Seville ), the starting point for Good Friday processions .

Numerous legends also emerged about Pilate's birthplace. Based on the possible Samnite origins in the small town of Bisenti in the province of Teramo in Abruzzo east of Rome, an ancient house is given as the house where he was born. There are also legends in various cities in Europe that identify them as the place where Pilate died. The Legenda aurea from the 13th century mentions different versions: the best known for this are the southern French city of Vienne , in which Pilatus, banished there by the Emperor Caligula , committed suicide (or his body got there), and Pilatus near Lucerne in the Switzerland, where he is said to have found his final resting place in Lake Pilatus after the body is said to have brought disaster in Rome, Vienne and Lausanne . The names of the mountain massif and lake have nothing to do with the person of Pilate, however, are derived from the Latin pila , pillar / strut ', and were only called this since the late Middle Ages.

Further Pilate legends or references can be found in Spain (Seville, Tarragona ), Italy ( Pilate's Castle in Nus near Aosta , where he is said to have stayed on his trip to Vienne; also Sutri, Lago di Pilato, Ponza Island), Austria ( Thiersee ) , Scotland ( Fortingall ) and also Germany (e.g. leases in Saarland and Forchheim or Hausen in Upper Franconia ).

Phrases and quotes

From pillar to post

The idiom describes a cumbersome and useless path, which usually leads back and forth between different instances or bodies. The phrase goes back to the presentation of the Passion of Jesus in the Gospel of Luke ( Lk 23.7–12 EU ). Because responsibility is unclear, Pilate sends Jesus to examine the case to the Jewish authority in the form of the tetrarch Herod Antipas . Herod interrogates Jesus, makes fun of him and sends him back to Pilate, where he is finally condemned to be crucified. The phrase links the starting point and destination of the path with the two-part name "Pontius Pilatus", which nevertheless designates one and the same person. There is also an equivalent phrase from Pilate to Herod .

Wash your hands in innocence

This idiom is intended to devalue statements that are made to prove an alleged innocence of one's own, especially if these are justified with practical constraints or a lack of influence, since Pilate carries out a cleansing ritual after the judgment of Jesus as a sign of his innocence, washes his hands ( Mt 27, 24 EU ), although in his opinion this would not be necessary as the judgment could not be his own decision and therefore not his fault, which he emphasizes during the ritual. See also Dtn 21.6 f. EU and Psalm 26.6 EU and 73.13 EU . The ablution was not a special gesture staged by Pilate, but was part of the rite of the jurisdiction of the time. A judge could not base his judgments on criminal investigations or evidence, only on testimony from witnesses. The danger of instrumentalizing the judge by means of false accusations was always present. A misjudgment would not have been a " sin " in itself, especially since this concept did not yet exist in Roman thought at the time, but it could disrupt the plans of gods and demigods (including the emperor), which those with one person could still have which would have resulted in a punishment. Ritual washing like this is still preserved in some Catholic churches of the Roman rite as " lavabo" rituals similar to the one described at the time. Due to the loss of this context from everyday consciousness, the phrase is now often interpreted and emphasized literally, an argument understood as "innocence in a liquid aggregate state" in which someone washes himself.

"What is truth?"

In the Gospel of John ( Joh 18,38 EU ) this is Pilate's question to Jesus about the discussion about his kingship and his function as a witness of the “truth”. An answer from Jesus is not recorded, rather it goes on: "And when he [Pilate] had said this, he stepped before the people and said: I find no guilt in him."

Ecce homo

The saying Ἰδοὺ ὁ ἄνθρωπος ( idoù ho ánthropos ), which was best known in the Latin translation ecce homo , means according to the standard translation : “See, there is man!” Joh 19.5 EU . With this exclamation, Pilate shows the scourged Jesus, crowned with thorns, to the people. This scene is often depicted in the fine arts and is known by this name.

(See also: Ecce Homo bow )

Quod scripsi, scripsi

“What I have written, I have written” Joh 19,22 EU - Latin: Quod scripsi, scripsi - Pilate replied to the accusation that the inscription INRI describes Christ's self-understanding and not - as usual - the reason for his condemnation.

He is remembered like Pilate in the Credo

He is not in good memory. In the Credo the Passion of Christ is commemorated with the words "suffered under Pontius Pilate".

To come to something like Pilate in the Credo

Describes a link that appears inappropriate.

See also

reception

Fiction

Pilate is a figure in numerous works of fiction . These include some historical novels, legends and a play in which Pilate or his wife are the main characters.

- Anne Bernet: Me, Pontius Pilate - Memoirs of an Innocent. Knaur, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-426-61919-9 .

- Mikhail Bulgakov : The Master and Margarita . Soviet novel, published as a serial from 1966, German first edition 1968.

- Gisbert Haefs : Pilate's lover. btb, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-442-75101-2 .

- Gertrud von le Fort : The wife of Pilate . Story, 1955.

- Werner Koch : Pilatus. Memories. Roman, 1959.

- Susanne Scheibler : "... and wash my hands in innocence". Goldmann, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-8289-0081-X .

- Éric-Emmanuel Schmitt : The Gospel according to Pilate . French novel from 2000, German first edition 2005.

- Jörg von Uthmann: Pontius Pilatus. Correspondence. Translated, annotated and introduced by Jörg von Uthmann , Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1991, ISBN 3-455-05959-7 .

- Miro Gavran : Pontius Pilatus , Croatian novel from 2010, German edition by Seifert Verlag, translation: Klaus Detlef Olof .

Movie

- Pontius Pilatus - Governor of Horror (Ponce Pilate / Ponzio Pilato) - France / Italy 1962, directed by Gian Paolo Callegari and Irving Rapper .

- Walter Vogt : Pilate before the silent Christ . Director: Max Peter Ammann . Television DRS, 1974.

- The miraculous experiences of Pontius Pilatus (Secondo Ponzio Pilato) - Italy 1987, directed by Luigi Magni.

literature

- Werner Eck : The Roman representatives in Judaea: provocateurs or representatives of Roman power? In: Mladen Popović (Ed.): The Jewish Revolt against Rome. Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Brill, Leiden 2011, ISBN 978-90-04-21668-6 , pp. 45-68.

- Dick Harrison : Traitor, Whore, Guardian of the Grail: Judas Iscariot, Mary Magdalene, Pontius Pilate, Joseph of Arimathea - stories and legends. Patmos-Verlag, 2007, ISBN 978-3-491-72515-7 .

- Alexander Demandt : Hands in Innocence: Pontius Pilate in History. Böhlau, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-412-01799-X .

- Alexander Demandt: Pontius Pilate. Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-63362-1 .

- Karl Jaroš : In the matter of Pontius Pilatus. von Zabern, Mainz 2002, ISBN 3-8053-2876-1 .

- Ralf-Peter Märtin : Pontius Pilatus. Romans, knights, judges. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2012, ISBN 978-3-596-19265-6 .

- Bettina Mattig-Krampe: The picture of Pilate in the German Bible and legend epics of the Middle Ages. Winter, Heidelberg 2001, ISBN 3-8253-1214-3 .

- Raul Niemann (Ed.): From Pontius to Pilatus. Pilate being cross-examined. Kreuz, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-7831-1300-8 .

- Andreas Scheidgen: The figure of Pontius Pilate in legend, conception of the Bible and historical poetry from the Middle Ages to the early modern period: literary history of a controversial figure. European Science Publishing House, Frankfurt 2002, ISBN 3-631-39003-3 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Pontius Pilatus in the catalog of the German National Library

- Pilate in the Lexicon of Saints

- Sebastian Hollstein: The most ungrateful job in Judaea , Spektrum.de, March 25, 2016

Individual evidence

- ↑ Alexander Demandt : Pontius Pilatus. Beck, Munich 2012, pp. 46–48.

- ↑ Werner Eck : The naming of Roman officials and political-military-administrative functions with Flavius Iosephus - problems of correct identification. In: Journal of Papyrology and Epigraphy . Volume 166, 2008, pp. 218-226; Walter Ameling, Hannah M. Cotton, Werner Eck et al. (Eds.): Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae / Palaestinae . A Multi-lingual Corpus of the Inscriptions from Alexander to Muhammad. Volume 2: Caesarea and the Middle Coast. 1121-2160. De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, p. 229.

- ↑ Philo of Alexandria. On the Embassy to Gaius. XXXVIII, 301-303. In: The Works of Philo, translated by CD Yonge, On the Embassy to Gaius.

- ↑ Eusebius of Caesarea, Church History 2, 7 and Chronicle , p. 178 ed. Helmet.

- ↑ Orosius, Historiae adversus paganos 7, 5.

- ↑ Origen, Contra Celsum 2, 34; on this Alexander Demandt: Pontius Pilatus . Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-63362-1 , pp. 92f.

- ↑ AE 1963, 00104 (= AE 1964, 39; AE 1964, 187; AE 1971, 477; AE 1981, 850; AE 1991, 1578; AE 1997, 166; AE 1999, 1681; AE 2002, 1556; AE 2005, 1583; AE 2008, 1542); the inscription is in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem (inv. no. 61-529).

- ↑ Géza Alföldy: Pontius Pilatus and the Tiberieum of Caesarea Maritima. In: Scripta Classica Israelica. Volume 18, 1999, pp. 85-108; Alexander Demandt: Pontius Pilate. Beck, Munich 2012, p. 41 f.

- ↑ Monika Bernett: The imperial cult in Judea under the Herodians and Romans. Studies on the political and religious history of Judea from 30 BC Chr. – 66 AD Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2007, pp. 208–214, especially pp. 213 f. with further literature.

- ^ Nir Hasson: Ring of Roman Governor Pontius Pilate Who Crucified Jesus Found in Herodion Site in West Bank. In: Haaretz , November 29, 2018 (accessed: December 1, 2018)

- ↑ Shua Amorai-Stark, Malka Hershkovitz et at .: An Inscribed Copper-Alloy Finger Ring from Herodium Depicting a Krater. In: Israel Exploration Journal. Vol. 68, Nov. 2018, pp. 208-220. Abstract in: Word document , provided by the IEJ (see overview of all issues ).

- ↑ Gerhard Winkler : Pontius II. 1. In: Der Kleine Pauly , dtv, Munich 1979, vol. 4, col. 1049; Matthias Blum: God's murder. In: Handbook of Anti-Semitism , Volume 3: Terms, Theories, Ideologies . De Gruyter Saur, Berlin 2010, ISBN 3-11-023379-7 , p. 113 (accessed via De Gruyter Online); Mark H. Gelber : Literary Anti-Semitism . In: Hans Otto Horch (Ed.): Handbook of German-Jewish Literature . de Gruyter, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-11-028256-6 , p. 38 f.

- ↑ Carl Schmitt : Der Leviathan in der Staatslehre des Thomas Hobbes , Cologne 1982, p. 67.

- ↑ Casa natale di Ponzio Pilato .

- ^ English translation of the Legenda Aurea with two versions of Pilate's death ( Memento from April 19, 2012 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ This Meinolf Schumacher : "sink in innocentia manus meas ...". Between acknowledgment of guilt and defense against guilt: hand washing in the Christian cult. In: Robert Jütte, Romedio Schmitz-Esser (ed.): Hand use. Stories by hand from the Middle Ages and early modern times. Wilhelm Fink, Paderborn 2019, ISBN 978-3-7705-6362-3 , pp. 59-77.

- ↑ Diliana Atanasova, Tinatin Chronz: ΣΓΝΑΞΙ ΚΑΘΟΛΙΚΗ: Reviews of worship and history of the early church five patriarchates for Heinz Gerd Brakmann 70th birthday . LIT Verlag Münster, 2014, ISBN 978-3-643-50552-1 , p. 420 ff . ( google.com [accessed July 3, 2020]).

- ^ Nestle / Aland 1928

- ↑ See also the compilation at hist-rom.de .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Pilate, Pontius |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Roman prefect of Judea at the time of Jesus of Nazareth |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1st century BC BC or 1st century |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1st century |