Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus of Nazareth ( Aramaic ישוע Yeschua or Yeshu , Greek Ἰησοῦς ; * between 7 and 4 BC BC , probably in Nazareth ; † 30 or 31 in Jerusalem ) was a Jewish traveling preacher. From around the year 28 he appeared publicly in Galilee and Judea . Two to three years later he was crucified by Roman soldierson the orders of the Roman prefect Pontius Pilate .

The New Testament (NT), as a document of faith of the early Christians, is also the most important source of historical research into Jesus . Afterwards Jesus called followers , announced the near kingdom of God to the Jews of his time and therefore called his people to repent . His followers proclaimed him after his death as Jesus Christ , the Messiah and Son of God . The result was a new world religion , the Christianity . Outside of Christianity , too , Jesus became significant.

The sources and their evaluation

Jesus left no scriptures. Almost all historical knowledge about him comes from his followers, who told, collected and wrote down their memories of him after his death.

Non-Christian sources

Few ancient Jewish, Greek and Roman authors mention Jesus, but almost only his title of Christ and his execution . Where their knowledge came from is uncertain.

The Jewish historian Flavius Josephus mentions Jesus twice in his Antiquitates Judaicae (around 93/94). The first passage, the Testimonium Flavianum (18.63 f.), Used to be considered completely inserted, today it is only considered to be revised by Christians. His presumably authentic core describes Jesus as a wisdom teacher for Jews and non-Jews, accused by noble Jews, condemned to death on the cross by Pilate , whose followers remained loyal to him. The second passage (20, 200) reports on the execution of James and describes him as the brother of Jesus, "who is called Christ". Some historians doubt that a Jew would have called Jesus that, others see a reference back to the first place here.

The Roman historian Tacitus reports in his Annales around 117 of "Chrestians", to whom Emperor Nero blamed the fire of Rome in 64, and notes:

"The man from whom this name is derived, Christ, was executed under the rule of Tiberius at the instigation of the procurator Pontius Pilate."

It is unclear whether this news is based on Roman or Christian sources. Possibly Tacitus found out about it during his governorship in the east of the empire.

Further notes by Suetonius , Mara Bar Serapion and the Babylonian Talmud ( Tractate Sanhedrin 43a ) refer only in passing or polemically to Christian tradition that has become known to them.

Christian sources

Information about Jesus is largely taken from the four canonical Gospels , some also from Paul's letters , some Apocrypha and individual words ( Agrapha ) that have been handed down outside of them . These texts come from early Christians of Jewish origin who believed in the resurrection of Jesus Christ (Mk 16.6; Acts 2.32) and combined authentic memories of Jesus with biblical, legendary and symbolic elements. With this they wanted to proclaim Jesus as the promised Messiah for their presence, not to record and convey biographical knowledge about him. Nevertheless, these religious documents also contain historical information.

The Pauline letters, written between 48 and 61, hardly mention any biographical data on Jesus, but do quote some of his words and statements about him from the early Jerusalem community , which confirm the corresponding Gospel statements . The letter of James also alludes to Jesus 'own statements and is considered a possible source for some New Testament scholars if it comes from Jesus' brother.

Because of allusions to the destruction of the Jerusalem temple (Mk 13.2; Mt 22.7; Lk 19.43 f.) The three synoptic gospels are usually dated later than the year 70. Probably none of the authors knew Jesus personally. However, they took over parts of the older Jesus tradition that go back to the first followers from Galilee. According to the widely accepted two-source theory, the authors of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke had before them the Gospel of Mark or a preliminary form of it. They adopted most of its texts and composition and changed them according to their own theological intentions. Their other common materials are assigned to a hypothetical source of logic Q with collected speeches and sayings of Jesus, the writing of which is dated from 40 to 70. Similar collections of proverbs were also presumably incurred in Syria Gospel of Thomas fixed. Its earliest components (Lk 1,2), which had been handed down orally for years, come from Jesus' first followers and may have preserved original words of Jesus. Their respective special property and the Gospel of John from around 100 can also contain independent historical information about Jesus.

Since the evangelists revised their sources each in their own way for their missionary and teaching purposes, their similarities all the more suggest a historical core. They tell the events from the entry of Jesus into Jerusalem to his entombment in almost the same order. These texts are traced back to a passion report from the early community, which narrative unfolded early creed formulas . The author of the Gospel of Mark linked this template with Jesus tradition from Galilee and expanded it; the other evangelists adopted it. In doing so, they changed some of the information on place, time, person and situation that are particularly common here, so that their historicity is highly controversial. Whereas previously only the crucifixion of Jesus by Romans, confirmed by non-Christian notes, his arrest and an execution warrant from the governor were undisputedly historical, today many researchers assume that the early Christians in Jerusalem accurately passed on some of the events leading to Jesus' death: especially in text passages, theirs The Gospel of John also contains details which, according to Jewish and Roman sources, appear plausible from a legal and socio-historical perspective.

research

The early Christian writings have been scientifically examined since around 1750. Research differentiates historical information from legendary, mythical and theological motifs. Many New Testament scholars used to believe that they could infer a biographical development of Jesus from the Gospels; often they speculatively added missing data. Some denied Jesus' existence because of the mythical elements of the sources (see Jesus myth ). The methodology and many individual theses of the life-Jesus literature of the time have been considered obsolete since Albert Schweitzer's history of life-Jesus research (1906/1913).

Since then, the historical-critical text analyzes have been refined . From 1950, extra-biblical sources were increasingly used to check the historical credibility of the NT tradition. From around 1970 onwards, increased knowledge of archeology , social history , oriental studies and Jewish studies at the time of Jesus was included. Evangelical, Catholic, Jewish and non-religious historians are now doing some research together, so that their results are less determined by ideological interests.

The vast majority of NT historians deduce from the sources that Jesus actually lived. They classify him completely in the Judaism of that time and assume that his circumstances of life and death, his proclamation, his relationship to other Jewish groups and his self-image can be determined. However, the extent and reliability of historical information in the NT are still highly controversial today. Which Jesus words and deeds are considered historical depends on preliminary decisions about the so-called authenticity criteria. The criteria of context and effect plausibility are widely recognized: "Historical in the sources is that which can be understood as the effect of Jesus and at the same time can only have arisen in a Jewish context."

origin

Surname

Jesus is the Latinized form of the ancient Greek inflected Ἰησοῦς with the genitive Ἰησοῦ ("Jesus"). It translates the Aramaic short form Jeschua or Jeschu of the Hebrew male given name Yehoshua . This is made up of the short form Jeho- the name of God JHWH and a form of the Hebrew verb jascha (“help, save”). Accordingly, Mt 1:21 and Acts 4:12 interpret the name as a statement: "God is salvation" or "the Lord helps". The Graecized form also remained common in Judaism at the time and was not supplemented with a Greek or Latin double name, as was usual, or replaced by similar-sounding new names.

Some places put the first name " Joseph son" (Lk 3:23; 4:22; John 1:45) or "son of Mary " (Mk 6.3; Mt 13:55), but usually Nazarenos or Nazoraios added to indicate his place of origin (Mk 1,9). Mt 2,23 EU explains this as follows: “(Joseph) settled in a city called Nazareth. This was to fulfill what had been spoken through the prophets: He is a Nazarene are called "This prophecy comes in. Tanach not before, but can the expression Neser (נֵצֶר," sprout ") in Isa 11.1 for the Messiah allude as a descendant of David . Possibly the evangelists reinterpreted a disparaging foreign designation of Jesus (Joh 1,46; Mt 26,71; Joh 19,19), which was also common for Christians in Syria (nasraja) and entered the Talmud as noṣri .

Year of birth and death

The NT does not give any date of birth of Jesus; The year and the day were unknown to the early Christians. The Christian year counting wrongly calculated Jesus' presumed year of birth.

The biblical statements are contradictory. According to Mt 2,1 ff. And Lk 1,5 he was born during the lifetime of Herod , who according to Josephus 4 v. Chr. BC died. Accordingly, Jesus was probably born between 7 and 4 BC. Born in BC. Luke 2.1f. dates the year of Jesus' birth to a "first" Roman census ordered by Emperor Augustus by entering property in tax lists under Publius Sulpicius Quirinius . However, he did not become governor of Rome for Syria and Judea until 6/7 AD . An earlier such tax collection is unproven there and is unlikely because of Herod's tax sovereignty. Lk 2.2 is therefore mostly interpreted as a chronological error and an attempt to make a trip by Jesus' parents to Bethlehem credible. Attempts to determine Jesus' birthday by astronomical calculations of a celestial phenomenon identified with the star of Bethlehem (Mt 2,1.9) are considered unscientific.

The Gospels report coherently only from one to three of the last years of Jesus' life. According to Lk 3.1, John the Baptist appeared "in the 15th year of the reign of the Emperor Tiberius ": According to this single exact year in the NT, Jesus appeared at the earliest from 28, probably since the Baptist was imprisoned (Mk 1:14). At that time he is said to have been around 30 years old (Lk 3:23).

According to all the Gospels, Jesus was executed on the orders of the Roman prefect Pontius Pilate. His year of death fell during his term of office in Judea from 26 to 36. The day before a Sabbath (Friday) during a Passover they pass as the day of death . The Synoptics name the main festival day after the Seder evening , i.e. the 15th Nisan in the Jewish calendar , whereas the Gospel of John names the day of preparation for the festival, i.e. the 14th Nisan. According to calendar-astronomical calculations, the 15th Nisan fell in the years 31 and 34, while the 14th Nisan fell on a Friday between 30 and 33. Many researchers consider Johannine dating to be "historically more credible" today. Some suspect an additional Passover Sabbath the day before the weekly Sabbath so that Jesus could have been crucified on a Thursday.

Most researchers consider 30 to be the likely year Jesus died because Paul of Tarsus became a Christian between 32 and 35 after persecuting the early Christians for a while. Accordingly, Jesus was between 30 and 40 years old.

place of birth

The NT birth stories (Mt 1–2 / Lk 1–2) are largely considered legends, as they are absent from Mk and Joh, are very different and contain many mythical and legendary features. These include the lists of the ancestors of Jesus (Mt 1; Lk 3), the announcement of the birth by an angel (Lk 1.26 f.), The generation of the spirit and virgin birth of Jesus (Mt 1.18; Lk 1.35), the visit of Oriental astrologers (Mt 2.1), the star that is said to have led them to Jesus 'place of birth (Mt 2.9), the child murder in Bethlehem (Mt 2.13; cf. Ex 1.22) and the parents' flight with them Jesus into Egypt (Mt 2.16 ff.).

According to Mt 2,5f and Lk 2,4, Jesus was born in Bethlehem in Judea, the place of origin of David, from which the future Messiah was to descend in the Tanakh. With this they emphasize that Jesus was David's descendant and that his birth in Bethlehem fulfilled the messianic promise Mi 5.1. In Mk and Joh there are no birth stories and Bethlehem as the place of birth.

All the Gospels name Nazareth in Galilee as Jesus' “home” or “father city”, residence of his parents and siblings (Mk 1,9; 6,1–4; Mt 13,54; 21,11; Lk 1,26; 2,39 ; 4,23; Joh 1,45 and more often) and therefore call him a “Nazarener” (Mk 1,24; 10,47) or a “Nazorean” (Mt 2,23; Joh 19,19). At that time, Nazareth was an insignificant village with a maximum of 400 inhabitants, as archaeological finds of buildings and dishes prove. It does not appear in the Tanakh. This insignificance is reflected in traditional objections to Jesus' messianship (Jn 1.45; Jn 7.41).

Matthew and Luke have differently balanced the traditional place of residence of Jesus 'family with the birth histories: Jesus' parents lived in a house in Bethlehem and only moved to Nazareth later (Matt. 2.22 f.); shortly before the birth of Jesus they moved from Nazareth to Bethlehem and, due to lack of accommodation, found shelter there in a stable (Lk 2,4 ff.). This is why historians today mostly assume that Jesus was born in Nazareth, but that his place of birth was later moved to Bethlehem in order to proclaim him as Messiah to Jews.

family

According to Mk 6.3, Jesus was the firstborn “son of Mary”. Joseph does not appear in the Gospel of Mark. The lists of ancestors (Mt 1.16; Lk 3.23), however, emphasize Jesus' paternal lineage as "the son of Joseph". This is also what Mary calls him in Lk 2.48 and the Galileans in John 6.42. According to Lk 2.21, Jesus was circumcised on the eighth day of his life in accordance with the Torah and, according to Jewish custom, was named after his father, that is, “Yeschua ben Josef”, as Lk 4.22 confirms. But after Jesus' baptism, the synoptics no longer mention Joseph.

This finding is explained in various ways. With reference to Mt 1.18, Bruce Chilton advocated the thesis that Jesus was conceived before Joseph's valid marriage to Mary and that Joseph died early. That is why Jesus was rejected in his homeland as an illegitimate child not entitled to inheritance (Hebrew mamzer ) (John 8:41). Because of Joseph's untimely death, no one could validly testify to his paternity. This corresponded to a Jewish polemic against the doctrine of the virgin birth of Jesus: According to Origen ( Contra Celsum ) , the philosopher Kelsos portrayed Jesus in the 2nd and the Talmud in the 4th century as the illegitimate child of a lover of Mary named " Panthera ". With reference to these sources Gerd Lüdemann explained Jesus' name after his mother in Mk 6.3 and his role as an outsider in Nazareth. Many New Testament scholars, on the other hand, assume that Joseph was actually fathered and that he came from a branch of the David dynasty that was suppressed at the time.

According to Mk 6.3, Jesus had four brothers named James, Joses (Greek version of Joseph, Mt 13.55), Judas and Simon as well as some unnamed sisters. The brothers named after some of the twelve sons of Jacob and the triggering of Jesus as the firstborn in the Temple (Lk 2:23) suggest a toratreue Jewish family. "Brothers" and "sisters" in the biblical usage can also include cousins (see brothers and sisters of Jesus ).

According to all the Gospels, Jesus' public appearance created conflict with his family. The fourth of the Biblical Ten Commandments - Honor your father and mother! (Ex 20.12; Dtn 5.16) - demanded, according to the interpretation of the time, that the first sons care for their parents and clan. But according to Mt 10:37, following Jesus was one of them; Lk 14.26 the leaving of the relatives, which is also known from the presumed Qumran community. Like them, Jesus evidently represented an “afamily ethos of discipleship”, since his first disciples, according to Mk 1:20, left their father behind at work, albeit with day laborers.

According to Mk 3:21, Jesus' relatives tried to hold him back and declared him insane. Thereupon he is said to have declared to his followers ( Mk 3,35 EU ): “Whoever fulfills the will of God is brother and sister and mother for me.” Rabbinical teachers also ordered obedience to the Torah to that of parents, but demanded it no complete separation from the family. According to Mk 7.10 f. Jesus did not cancel the fourth commandment either: There should be no form of pledge to evade the obligation to maintain one's parents.

According to Mk 6: 1-6, Jesus' teaching in Nazareth was rejected, so that he never returned there. But according to Mk 1:31, women from Jesus' homeland looked after him and his disciples. According to Mk 15.41 they stayed with him until death, so according to Jn 19.26 f. his mother too. He is said to have taken care of their welfare on the cross by entrusting them to another disciple. Although his brothers "did not believe in him" according to John 7.5, his mother and some brothers belonged to the early church after his death (Acts 1:14; 1 Cor 9: 5; Gal 1:19). James later became their leader because of his resurrection vision (1 Cor 15: 7) (Gal 2: 9).

According to a quote from Hegesippus handed down by Eusebius of Caesarea , Emperor Domitian had Jesus' grandnephews arrested and interrogated during his persecution of Christians (around 90). They answered yes to the question of their Davidic descent, but denied the emperor's suspected political ambitions and emphasized their rural poverty. They were released and then rose to become church leaders. It is therefore likely that the relatives of Jesus saw themselves as descendants of King David.

Language, education, profession

As a Galilean Jew, Jesus spoke Western Aramaic on a daily basis . This is confirmed by some Aramaic quotes from Jesus in the NT. Whether one can translate Greek expressions and idioms back into Aramaic has been an important criterion since Joachim Jeremias to distinguish possible authentic words from Jesus from the early Christian interpretation.

Biblical Hebrew was hardly spoken in Palestine at the time of Jesus. Nevertheless, he may have mastered it because, according to the NT, he knew the Tanach well and read it aloud and interpreted it in the synagogues of Galilee. He may also have got to know Bible texts from Aramaic translations ( Targumim ). Whether he could speak the Greek Koine , which was the lingua franca in the east of the Roman Empire at the time, is uncertain due to the lack of direct NT evidence.

From Jesus' youth, the New Testament only records one stay of the 12-year-old in the temple, during which he is said to have impressed the Jerusalem Torah teachers with his interpretation of the Bible (Lk 2.46 f.). This is considered a legendary motif to explain Jesus' knowledge of the Bible. Children of poorer Jewish families who had no scrolls could learn to read and write at best in Torah schools and synagogues. According to Luke 4:16, Jesus read from the Torah in the synagogue of Nazareth before he interpreted it. According to Mk 6.2 f. Jesus' listeners did not trust him to preach and noticed that it differed from the traditional interpretation of Scripture; According to Jn 7:15 they asked themselves: How can this one understand the scriptures, although he has not learned it? But Jesus' frequent question to his listeners "Have you not read ...?" (Mk 2.25; 12.10.26; Mt 12.5; 19.4, etc.) assumes that he is able to read. It is uncertain whether he could also write. Only Jn 8: 6,8 mentions a gesture of writing or drawing on the ground.

Jesus' style of preaching and argumentation is rabbinic ( Halacha and Midrashim ). His first disciples called him “ Rabbi ” (Mk 9.5; 11.21; 14.45; Joh 1.38.49; Joh 3.2; 4.31 etc.) or “Rabbuni” (“my master”: Mk 10, 51; Jn 20:16). This Aramaic address corresponded to the Greek διδάσκαλος for "teacher". It expressed reverence and gave Jesus the same rank as the Pharisees , who also described themselves as interpreters of the Mosaic commandments (Mt 13.52; 23.2.7 f.). Pinchas Lapide deduces from the strong similarities between Jesus' interpretation of the Torah and the rabbis of the time that he must have attended a Torah school.

According to Mk 6.3, Jesus, according to Mt 13.55, his father was a builder (Greek τέκτων , often misleadingly translated as “ carpenter ”). Presumably, like many Jewish sons, Jesus learned the father's profession. Although a craft as a livelihood was common for a rabbi at the time, the NT does not provide any information on this. Jesus' knowledge of the building trade is shown, for example, in the parables Lk 6.47-49 and Mk 12.10. According to many metaphors of his statements (e.g. Luke 5: 1-7; Jn 21: 4-6) he could also have been a shepherd, farmer or fisherman.

Nazareth was seven kilometers from the city of Sepphoris , which Herod Antipas had converted into a residence and where the large landowners lived. It may have served as a workplace for some villagers. The NT does not mention the city and emphasizes that Jesus did not visit other Hellenistic cities.

Act

Relationship to John the Baptist

The baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist is considered a historical event with which his public ministry began. According to Mt 3: 7–12, John was; Lk 3.7 ff. A prophet of the near final judgment , who came from a priestly family (Lk 1.5) and lived as an ascetic , possibly as a Nazarite , in the uninhabited desert (Lk 1.80). According to Mk 1,4 f. Forgiveness and required a confession of sin . Josephus understood it as a common Jewish cleansing ritual .

Mk 1,11 EU presents Jesus' baptism as God's unique election (“you are my beloved Son ”; cf. Ps 2,7; Hos 11,1 and more) and all his subsequent work as a mission through God (cf. Rom 1, 3 f. EU ). How Jesus understood himself is questionable, since he never calls himself directly "Son of God" in the NT. The Johannine I-am-words are traced back to the evangelist, not the historical Jesus. According to Jn 3:22; 4: 1 he baptized parallel to John the Baptist for a while. According to Jn 1,35-42 the brothers Simon Peter and Andrew came to Jesus from the Johannes circle. Accordingly, there was exchange and possibly competition between the two groups. It is also plausible that Jesus became a disciple of John when he was baptized.

Presumably, Mark reduced Jesus' contact with John to the isolated baptism event and only allowed him to appear in public since John's imprisonment. Mk 1:15 is taken as evidence of the similarities between the two messages. Jesus took over the final call to repent of the Baptist and probably also the apocalyptic motif of the fire of judgment on earth (Lk 12.49, Mt 3.10). However, according to Mk 2,16-19, he rejected fasting and asceticism for his disciples and cultivated table fellowship with those Jews who were excluded from salvation as "unclean" according to the current interpretation of the Torah. He did not retreat into the desert, but turned to Jews and strangers who had just been cast out and promised them the unconditional salvation of God. The imprisoned Baptist is said to have asked Jesus through messengers: Are you the one to come? (the Messiah ; Mt 11.2 ff.).

Accordingly, the early Christians emphasized the forerunner and witness role of John towards Jesus (Mk 1,7; Lk 3,16; Mt 3,11; Joh 1,7 f .; 3,28 ff., Among others). According to Mk 9:13, Jesus identified John with the prophet Elijah , in whose second coming before the final judgment Jews believed at that time, and according to Luke 7: 24-28 with the prophet of the end times announced in Mal 3.1. Therefore he advocated the baptism of St. John even after he began to appear as a rescue from the final judgment.

Jesus probably knew that Herod Antipas had the Baptist executed (Mk 6:17 ff.). In biblical tradition, a murdered prophet was considered legitimized by God. Accordingly, Jesus announced his own suffering with his baptismal testimony, expected according to Lk 13: 32-35; Lk 20: 9-19 was an analogous violent end for itself and placed in the ranks of the persecuted prophets of Israel. According to Mk 11: 27-33, Jesus later legitimized his entitlement to the forgiveness of sins and to cleansing the temple against opponents of Jerusalem with his baptism by John.

Area of occurrence

Jesus saw himself sent only to the “lost sheep of the house of Israel” (Mt 10: 5; 15:24); his few traditional encounters with non-Jews appear as exceptions. His travel routes cannot be exactly reconstructed, since many of the places and their sequence in the Gospels come from the evangelists and can reflect the spread of Christianity when they were written. Neighbors of Nazareth such as Kana and Naïn, as well as places such as Bethsaida , Chorazin and Magdala that can be reached by day marches and boat trips across the Sea of Galilee are plausible . Further away were Gerasa in the southeast (Mk 5.1), Tire and Sidon in the northwest (Mk 7.24). It is uncertain whether he also roamed Samaria (Jn 4,5 versus Mt 10,5). Cities built by Romans and Herodians, such as Tiberias and Sepphoris , are not mentioned in the NT. According to Mk 8.27, he only entered the surrounding villages of Caesarea Philippi . From this it is concluded that Jesus worked more in the country and avoided Hellenized cities.

In Capernaum Jesus is said to have appeared first (Mk 1.21 ff .; Lk 4.23), moved into Peter's house there (Mt 4.12 f.) And returned there from his travels more often (Mk 1.29; 2 , 1; 9.33; Lk 7.1). Mt 9: 1 therefore calls the place “his city”. This fishing village was then on the border of the area ruled by Herod Antipas. Perhaps Jesus chose his quarters here in order to be able to flee from his persecution to the neighboring area of Herod Philip if necessary (Lk 13:31 ff.).

Proclamation of the kingdom of God

The near "kingdom of God" was Jesus' central message according to the Synoptic Gospels (Mk 1:14 f.): NT research almost always assumes this to be historical. The Gospels illustrate the term through concrete acts, parables, and doctrinal discussions of Jesus. They assume that he is known among Jews. In contrast, NT texts addressed to non-Jews rarely use the term. With this, Jesus was referring to the tradition of prophecy in the Tanakh and apocalyptic, as some possibly real quotes from Deutero-Isaiah and Daniel show.

Some of Jesus' statements announce God's rule as imminent, others say they have already begun or assume their presence. It used to be controversial whether the futuristic (e.g. Albert Schweitzer ) or the presentical (e.g. Charles Harold Dodd ) eschatology goes back to Jesus. Since around 1945 most exegetes have judged both aspects to be authentic according to their paradoxical coexistence in the Our Father (Mt 6: 9-13). They emphasize that Jesus understood this rulership as a dynamic happening and currently ongoing process, not just as a world beyond. Following the Jewish apocalyptic, he did not expect the destruction of the earth, but its comprehensive renewal, including nature, and through his actions drawn it into his time.

This is followed by words about the fall of Satan (Lk 10.18 ff.) Or the argument about whether Jesus received his healing power from Beelzebub or God (Mt 12.22 ff. Par.). The “stormy saying” (Mt 11:12) suggests that the coming of God's rulership will be preceded by violent conflicts that have continued from the appearance of John the Baptist until Jesus' presence. Like John, Jesus preached an unexpected judgment that would offer one last chance to repent (Lk 12: 39-48). Unlike the latter, he presented the invitation to the kingdom of God as a feast open to all. Possibly he linked the salvation from the final judgment with the current decision of his listeners about his message (Mk 8:38; Lk 12,8).

The “ Beatitudes ” assigned to the source of the Logia (Lk 6: 20-23; Mt 5: 3–10) promise God's rulership to the currently poor, mourning, powerless and persecuted as a righteous turnaround to alleviate their need. These people were Jesus' first and most important addressees. His answer to the Anabaptist question (Mt 11: 4 ff.), Which is often considered to be authentic, indicates that the kingdom of God already encounters them in Jesus' healings. His inaugural sermon (Lk 4,18-21) updates the biblical promise of a year of relief for debt relief and land redistribution (Lev 25) for the present poor.

Social historical studies explain such NT texts from the living conditions of the time: Jews suffered from exploitation , tax levies for Rome and the temple, daily Roman military violence, debt enslavement, hunger , epidemics and social uprooting. Sometimes the theology of the poor is explained in the oldest Jesus tradition from the influence of Cynical wandering philosophers, but mostly from biblical, especially prophetic traditions.

According to Wolfgang Stegemann , Jesus and his followers did not seek “negotiation processes about a specific model of society” with their Kingdom of God sermon, but rather expected the implementation of a different order from God alone. Their message could only be accepted or rejected (Lk 10.1-12). They have placed the rule of God based on the model of a benevolent patronage, usually expected in vain by the rich, against currently experienced forms of rule. According to John Dominic Crossan , the Jesus movement spread radical egalitarianism through "free healing and shared meals" without settling down . So she let the rule of God be directly experienced and attacked the hierarchical standards of values and social structures in order to invalidate them. Similarly, Martin Karrer thinks that Jesus caused a "subversive" movement of those who deviate from religious and social norms.

Activity as a healer

Ancient sources often tell of wonderful healings, but nowhere so often about an individual as in the NT. The Gospels tell of Jesus healing miracles as exorcisms or therapies as well as miracles of gifts, salvation, norms and raising of the dead. The exorcisms refer to then incurable diseases or defects such as "leprosy" (all types of skin diseases), various types of blindness and what is now known as epilepsy and schizophrenia . Those affected were considered " possessed by unclean spirits ( demons )" (Mk 1:23). They avoided contact and contact with them, drove them out of inhabited areas and so often delivered them to death.

Exorcism and therapy texts emphasize Jesus' devotion to such marginalized people, including non-Jews, who removed the cause of their exclusion and thus ended their isolation. Their frame verses often invite faith and repentance. His healing successes brought him distrust, envy and resistance, triggered the killing plans of his opponents (Mk 3,6; Joh 11,53) and caused demands for demonstrative “signs and wonders”. Jesus rejected this (Mk 8.11 ff .; 9.19 ff.). Special features of the NT miracle texts are that the miracle worker attributes the healing to the faith of the healed (“Your faith has saved you”: Mk 5.34; 10.52; Lk 17.19 and others) and they are used as a sign for the beginning of the kingdom of God and the end of the reign of evil (Mk 3:22 ff., a word of Jesus that is mostly believed to be genuine). New Testament scholars therefore assume that Jesus suggested the oldest exorcism and therapy texts: Because eyewitnesses experienced his actions as miracles, they would have passed it on and then ascribed further miracles to him.

Torah interpretation

The Sermon on the Mount (Mt 5–7) is introduced as the “teaching” of Jesus (Mt 5: 2). It was compiled by early Christians from individual sermons of Jesus and edited or composed by the evangelist. Its beginning (Mt 5:14 ff.) Reminds Jesus' followers of Israel's commission to be God's people "light of the peoples" (Isa 42,6) by fulfilling the Torah in an exemplary manner. Mt 5: 17-20 accordingly emphasizes that Jesus fulfilled all traditional commandments, not abolished them.

Whether Jesus himself saw it that way is disputed. Unlike Paul, he only took a position on individual commandments, not on the Torah as a whole, since, like all Jews of that time, he assumed it to be the valid will of God. He tightened some commandments, defused others, and relativized others so that they were abolished in early Christianity. Today this is seen as an internal Jewish interpretation of the Torah, not as a break with Judaism. Like Rabbi Hillel (approx. 30 BC to 9 AD), Jesus gave charity the same rank as fear of God and thus placed it above the other Torah commandments (Mk 12: 28-34). He saw himself sent to those who were despised because of transgressions ( Mk 2.17 EU ): “It is not the strong who need a doctor, but the sick. I came to call sinners and not the righteous. ”Among other things, this meant Jewish“ tax collectors ”who collected taxes for the Romans, often taking advantage of their compatriots and therefore being hated and shunned. According to Lk 19.8, Jesus invited them to share with the poor, according to Mt 6: 19-24 he interpreted the accumulation of property as a breach of the first commandment. Only with the giving up of possession for the poor does the law-abiding kingdom fulfill all of the Ten Commandments in such a way that he becomes free to follow (Mk 10.17-27).

The “antitheses” interpret important Torah commandments. Afterwards, Jesus emphasized the inner attitude as the cause of the offense beyond its wording: The prohibition of killing (Ex 20:13) is broken by those who are only angry with their neighbor, who abuse or curse them. With that he draws God's judgment of wrath upon himself. That is why he should first be reconciled with his opponent before making sacrifices in the temple (Mt 5: 21-26). Adultery (Ex 20:14) already committed internally who, as a married man, desires another woman (Mt 5: 27-30). Abuse of the name of God (Ex 20,7) and lies (Ex 20,16) are every oath , not first a perjury (Mt 5,33 ff.). Because God has promised the preservation of his creation (Gen 8:22), Jews and followers of Jesus should forego retribution (Gen 9,6) through counter-violence (Mt 5:39) and instead respond with creative love of enemies , especially blessing their persecutors as neighbors, surprise them with care and voluntary accommodation and thus “disarm” them (Mt 5: 40–48). With this, Jesus reminded of Israel's task to bless all peoples in order to free them from tyranny (Gen 12: 3), to end the rule of the “evil one” and to call up God's kingdom. Contempt and condemnation of others would have the same consequences as their use of violence ( Mt 7.1–3 EU ):

“Do not judge so that you will not be judged! For as you judge, you will be judged, and according to the measure with which you measure and assign, you will be assigned. Why do you see the splinter in your brother's eye, but you don't notice the bar in your eye? "

According to Jn 8,7 EU , Jesus saved an adulteress from stoning by making the accusers aware of their own guilt: “Whoever is without sin, be the first to throw a stone at her.” This is used as a debilitation of what is prescribed in the Torah The death penalty for adultery (Lev 20,10) interpreted. The sentence is often taken to be real or at least in accordance with Jesus, although the narrative is missing in older manuscripts of John's Gospel.

According to Mk 7.15, Jesus only declared to be unclean that which came from within a person, not that which entered into him from without. In the past, this was often understood as the repeal of the important food and purity laws and thus as a break with all other cult laws of the Torah. Today it is more of an interpretation that places moral above external purity. In competition with the Sadducees and parts of the Pharisees, Jesus did not want to distinguish the clean from the unclean, but instead wanted to aggressively expand purity to groups considered unclean. For this reason he integrated leprosy sufferers (Mk 1.40–45), sinners (Mk 2.15) and tax collectors (Lk 19.6) who were excluded in Israel and refused to accept non-Jewish non-Jews (Mk 7.24–30).

pendant

From the beginning of his appearance, Jesus called male and female disciples (Mk 1:14 ff.) To leave his job, family and property (Mk 10: 28-31) and wander around without arms and arms to God's kingdom proclaim. Like him, they belonged to the common people who were impoverished and often threatened by hunger. They were sent out to heal the sick, cast out demons, and impart God's blessings. When entering a house they should put the whole clan under God's protection with the peace greeting " Shalom ". If they were not welcome, then they should leave the place without returning and leave it to God's judgment (Mt 10: 5-15).

This broadcast speech and comparable follow-up texts are assigned to the source of the logia and interpreted in social-historical research as an expression of the living conditions and values of the early Jesus movement . Gerd Theißen based his influential sociological thesis on wandering radicalism on such texts in 1977: In the midst of an economic crisis and crumbling social ties, the Jesus movement represented an attractive, charismatic follow-up ethos for the renewal of Judaism. The close followers of Jesus were aware of an eschatological rescue task wandering around as hikers without possessions and weapons and received material support from local sympathizers.

According to Geza Vermes, Jesus and his followers were “wandering charismatics” influenced by a “charismatic milieu” in the Galilee of that time. Because even from Chanina ben Dosa (around 40-75), a representative of Galilean Hasidism , caring for the poor, lack of property, miraculous healing through prayer and Torah interpretations were handed down.

According to James H. Charlesworth, should Jesus have chosen a closer, leading circle of twelve ( apostles ), this underlines his nonviolent political claim, which at the time of the Jewish Second Temple was inseparable from religious goals. Because the wills of the twelve patriarchs and other documents indicate the importance of the twelve tribes of Israel in the time of Jesus. These should rule on earth if God were to restore Israel's political autonomy.

Women, marriage, adultery

Jesus' behavior towards women was new and unusual in patriarchal Judaism at the time. Many of the reported healings were for socially excluded women such as prostitutes , widows or foreigners. Healed women followed him from the beginning (Mk 1.31), some took care of him and the disciples (Lk 8.2 f.). According to the NT, they also played an important role for Jesus in other ways: A woman is said to have anointed him before his death (Mk 14.3–9), Pilate's wife is said to have protested against his execution (Mt 27:19). Followers of Jesus are not said to have fled, but to have accompanied his death, observed his burial (Mk 15,40 f.), Discovered his empty tomb (Mk 16,1-8) and were the first to witness his resurrection (Lk 24,10; Joh 20.18).

According to Mt 19:12, Jesus did not command his disciples to get married, but instead allowed celibacy for the sake of their task, the proclamation of the kingdom of God. Paul later met some disciples with their wives in Jerusalem (1 Cor 9: 5), so that they may have already wandered around with Jesus and their husbands. The NT Gospels show no trace of a partnership with Jesus; he may have been unmarried. Only the late apocryphal Gospel of Philip mentions in an incomplete verse (6:33) added in the translation: Jesus kissed Mary Magdalene [often on the mouth]. In the context this does not indicate a partnership, but rather the transmission of a divine soul power. NT research rejects popular theories that Mary Magdalene was Jesus' wife as unrestricted fiction.

While the Torah, according to Deut. 24: 1-4, allowed men to divorce with a letter of divorce for the divorced woman, Jesus emphasized to Pharisees according to Mark 10: 2–12 the indissolubility of marriage according to Gen. 1.27 and forbade both spouses to his disciples Divorce and remarriage. According to Mt 5:32 and 19: 9, he justified this as the protection of women who would otherwise be forced to commit adultery. The inset "apart from (the case of) adultery (s)" (porneia) is considered an editorial addition. According to Lk 16:18, Jesus addressed the Jewish man who would break the first marriage if he remarried.

Since some of the Dead Sea Scrolls (CD 4, 12–5, 14) and the Shammai Rabbinical School took a similar position, it is assumed that this severity reacted to the social dissolution tendencies of that time in Judaism and both criticized the behavior of the upper class as well as impoverished it Should protect families at risk from breakdown. That Jesus directed his prohibition against Jewish men and women accused of adultery according to Lk 7.36 ff .; John 8: 2 ff., Is interpreted as the intention to protect women in a patriarchal society.

Pharisee

Pharisees and Torah scholars mostly appear in the Gospels as critics of the behavior of Jesus and his followers. They indignant his forgiveness of sins as presumption worthy of death (Mk 2,7), they disapprove of his table fellowship with “tax collectors and sinners” (2.16) who are excluded as “unclean” and the celebrations of his disciples (2.18), so that they stereotype him despise as “eaters and wine drinkers” (Lk 7: 31-35). Especially Jesus' demonstrative Sabbath healings and permission to break the Sabbath (Mk 2-3) provoke their hostility. According to Mk 3,6 they plan his death together with followers of Herod. Deliberate breaking of the Sabbath was punishable by stoning according to Ex 31.14 f., Num 15.32–35. Jn 8:59 and 10:31, 39 mention attempts by Jewish opponents of Jesus to stoning because he had placed himself above Abraham and Moses .

These verses are considered ahistorical because the Pharisees were neither closed nor identical with the Torah teachers, nor associated with Herodians. They hardly mention the Passion texts and not at all Jesus' Sabbath conflicts. The verses were apparently intended to brace the events in Galilee editorially with plans to kill Jesus' opponents in Jerusalem (Mk 11:18; 12:13; cf. Jn 11:47; 18: 3).

Other NT texts come closer to the historical situation: According to Mk 2.23 ff., Jesus justified the gathering of ears of his disciples on the Sabbath as a biblically permissible violation of the law in the event of acute famine. He thus supplemented the exceptions to the Sabbath law for saving lives discussed at the time. According to Lk 7.36; 11:37 Pharisees invited Jesus into their houses to eat and were interested in his teaching. According to Mk 12.32 ff., A Jerusalem Pharisee agreed with Jesus to summarize the Torah in the double commandment of love of God and neighbor. Such summaries corresponded to Jewish tradition. The Pharisees also agreed with Jesus in anticipation of the kingdom of God and the resurrection of all the dead. According to Lk 13:31, they warned and saved him from pursuing Herod. A Pharisee arranged for Jesus to be buried.

Many scholars today assume that Jesus was the closest to the Pharisees among the Jews of that time. That they were nevertheless stylized as his opponents is explained by the situation after the destruction of the temple in 70: After that, Pharisees took over the leading role in Judaism. Jews and Christians separated themselves more and more and legitimized this mutually in their writings that were created at the time.

Herodians

The vassal king Herod the Great, appointed by Rome, was hated by many Jews as a "half-Jew" from Idumea . There were riots against the high tax requirements for his palace and temple buildings. That is why Rome divided its territory after his death in 4 BC. BC under his four sons, who were no longer allowed to call themselves "King of the Jews" and were subordinate to the Roman prefect . Herod Antipas , who ruled Galilee and Perea at the time of Jesus, had the Galilean places Sepphoris and Tiberias expanded into Hellenized metropolises. These cities and the Jews who settled there were considered unclean by the Galilean rural population and anti-Roman Jerusalemites. The second marriage of Antipas with his niece Herodias , who was already married, was considered a blatant Torah break. According to Mk 6,17-29, he had John the Baptist arrested and beheaded because of his criticism and is said to have known Jesus by name and persecuted according to Mk 3,6 and Lk 13,31. With this, Mt 14:13 explains that Jesus did not visit any of the cities built by Antipas. According to Luke 23: 6-12.15, Antipas is said to have interrogated the imprisoned Jesus and then handed him over to Pilate as a harmless madman. This is considered an editorial attempt to make the clearance attempts of Pilatus reported below plausible.

Sadducees

Jesus' main opponents in Jerusalem were the Hellenistic educated and wealthy Sadducees , who, as the priestly heirs of the Levites, directed the Jerusalem temple . The central sacrificial cult there, to be obeyed by all Jews, was their livelihood and an important economic factor for all of Palestine. They appointed the high priest , who reduced his hereditary office as the highest judge for cult questions to Deut 17: 8-13.

The officials were appointed and deposed by Roman prefects from 6 AD and had to support them in the regulatory control of Judea-Syria. For this they were allowed to collect the temple tax, which is obligatory for Jews, to administer the temple cult, to maintain an armed temple guard and also to judge cult offenses, but not to execute the death penalty; this was the responsibility of the Roman prefects only. In the hinterland their influence was less, but they also enforced the temple tax and observance of the cult laws there.

Apparently Jesus did not reject the temple priests in principle: According to Mk 1,44, he sent people who had been healed to them in Galilee, so that they could determine their recovery and accept them back into society. According to Mk 12.41 ff. He praised temple donations from a poor widow as a devotion to God, which he missed in the rich. His interpretation of the Torah made sacrifices subject to reconciliation with opponents of the conflict (Mt 5:23 f.).

Zealots

Jesus appeared in a country marked by strong religious and political tensions. For generations, Jewish liberation fighters against foreign powers have come from Galilee, the former northern Reich of Israel . Since the tax boycott of Judas Galilaeus , which was suppressed in 6 AD , resistance groups emerged which fought against Roman rule by various means, tried to prepare revolts and attacked hated imperial standards, standard symbols and other symbols of occupation. Some committed knife attacks on Roman official ( " Sicarii " dagger carrier). These groups, known today as zealots (“zealots”), were generally devalued and stigmatized by the Romans and the Roman-friendly historian Josephus as “robbers” or “murderers”.

Jesus addressed his apocalyptic message of the near kingdom of God to all Jews. He publicly announced the imminent end of all violent empires. His work should actively bring about this kingdom and gain space in his healing deeds (Mt 11: 5) and his non-violent succession in contrast to the rulers of tyranny (Mk 10.42 ff.). Like the Zealots, he called the vassal king Herod Antipas a "fox" (Lk 13:32). During the healing of a possessed person from the garrison town of Gerasa (Mk 5: 1–20), the demon introduced by the Latin loan word for “legion” attacks a herd of pigs, which then drowns itself. In doing so, Jesus may have exposed the Roman military rule in order to symbolically disempower it: For the Jews, considered unclean pigs, were known at that time as a Roman sacrificial animal and legion mark. The purchase of arms according to Luke 22:36 is interpreted as Jesus' permission to offer limited resistance to persecution on the way to Jerusalem.

Because of NT texts such as the Magnificat (Lk 1.46 ff.) Or the jubilation of the pilgrims on Jesus' arrival in Jerusalem (Mk 11.9 f.), Many researchers emphasize an indirect or symbolic political dimension of his work. That is probably why some of his disciples were earlier Zealots, such as Simon Zelotes (Lk 6:15), possibly also Simon Peter and Judas Iscariot .

Unlike the Zealots, Jesus called tax collectors hated as “unclean” for the Romans (“tax collectors”) to follow him and was their guest (Mk 2,14 ff.), Of course in order to fundamentally change their behavior towards the poor (Lk 19 , 1-10). Unlike those who wanted to anticipate God's judgment with violence against those of different faiths, he called on his listeners to love their enemies (Mt 5: 38-48). As a criticism of the Zealots, the word Mt 11:12 is interpreted as referring to the "violent people who force God's kingdom to come and take it over by force".

For Zealots, Roman coins with imperial heads violated the biblical ban on images (Ex 20.4 f.), So that they refused to donate to Rome. The tax question of his Jerusalem opponents was supposed to convict Jesus as a zealot. His traditional answer escaped the trap set ( Mk 12.17 EU ): “Give the emperor what belongs to the emperor, and to God what belongs to God!” Since according to Mt 6:24 for Jesus the whole person belonged to God, this could as a rejection of the imperial tax, but left this decision to the addressed. Only the evangelists rejected this interpretation (Lk 23.2 ff.).

That Jesus' work elicited political reactions is shown by his crucifixion on the highest Jewish festival. It is questionable, however, whether he made a political messiah claim. German New Testament scholars used to emphasize the apolitical character of his appearance. His execution as King of the Jews (candidate for the Messiah) was considered a miscarriage of justice and a “misunderstanding of his work as a political one”. In contrast, recent studies have shown that Jesus partially agrees with the Jewish resistance movement and declared his violent end to be an expected consequence of his own actions.

Events at the end of life

Entry into Jerusalem

According to Mk 11: 1-11 EU , Jesus rode a young donkey into Jerusalem in the wake of his disciples, while a crowd of pilgrims cheered him:

“Hosanna! Blessed be he who comes in the name of the Lord! Blessed be the kingdom of our father David that is now to come. Hosanna on high! "

The call "Hosanna" ("God, save!": Ps 118.25) was common at high Jewish festivals and the enthronement of a king (2 Sam 14.4; 2 Kings 6:26). “He comes in the name of God” meant the expected Messiah on the throne of King David (2 Sam 7.14 ff.), As whom the Gospels preach Jesus (Mt 11.3; 23.39; Lk 7.19; 13.35 ). With palm branches spread out (v. 8), an ancient symbol of triumph, Jews celebrated their victories over non-Jews (Jdt 15.12; 1 Makk 13.51; 2 Makk 10.7).

Jesus' donkey ride recalls Zech 9: 9 ff .: There a powerless Messiah is announced who will abolish the weapons of war in Israel and command peace to all peoples. This post-exilic promise kept the earlier promise of universal disarmament, which was to begin in Israel (Isa. 2.2–4 / Mi 4.1–5; swords to plowshares ). So it contradicted the population's expectation of a successor to David, to drive out the foreign rulers and to renew the great empire of Israel.

In Judaism at that time, the Messiah's hope was connected with the gathering of all exiled Jews, just internal justice and pacification of the international community. However, the entry of Jewish aspirants to the throne was often a signal for uprisings. Thus, according to Josephus , the Zealot Shimon bar Giora strove for Jewish kingship around 69: He and his followers triumphantly entered Jerusalem as a charismatic “savior and protector” of the Jews, but captured by the Romans in a purple cloak, transferred to Rome and there been executed.

Jesus also awakened messianic hopes in the rural population, for example by promising the poor to own the land (Mt 5: 3), declaring his healing deeds as the initial realization of these promises (Lk 11:20) and on his way to the temple city of the poor as the son of David addressed (Mk 10.46.49). Therefore, Jesus' visit to Jerusalem on Passover meant a confrontation with the local power elites of the Sadducees and Romans, in which he must have been aware of the risk of death. The non-violent image of the Messiah corresponds to statements of Jesus that are held to be genuine, such as Mk 10.42 ff. EU : He came to serve everyone like a slave as the Son of Man in order to oppose the oppression of the rulers with his non-ruling community of trust.

The Romans interrogated and crucified Jesus a few days later as the alleged "King of the Jews". His arrival, hailed as the arrival of the Messiah, may have been the reason for this. Romans feared a crowd (Mk 5:21) as a “dangerous and unpredictable social group”, as a “mob”. However, original Christians may have exaggerated the scene as "a counter-image to the entry of the prefect into the city for the three great festivals". Maybe they added the donkey ride, as such a clear Messiah demonstration would have prompted the Romans to arrest Jesus.

Criticism of the temple cult

According to Mk 11.15 ff., Jesus drove some traders and money changers from the temple forecourt for Israelites, proselytes and non-Jews on the day after his entry . The traders working in the pillared hall on the south side of the temple sold ritually permitted sacrificial material (pigeons, oil and flour) to pilgrims and collected the temple tax paid annually by all Jews for collective animal sacrifices. Jesus knocked over their stands and prevented objects from being carried through this area. Accordingly, he disrupted the proper offering of purchased sacrifices and the delivery of funds that had been received, thereby demonstratively attacking the temple cult.

Whether the action is historical and, if so, whether it should attack the Jewish temple cult as an institution or only certain grievances is discussed. Usually a scene that is only observed by a few is assumed, not a dramatic scene as in Jn 2: 13-22, as otherwise the Jewish temple guard or even Roman soldiers from the adjacent Antonia Castle would have intervened. Since Jesus continued to discuss with Jerusalem Torah teachers in the temple district (Mk 11:27; 12:35), his action was apparently intended to initiate such debates. The influx of people makes it plausible that the temple priests are now supposed to have secretly planned Jesus' private arrest a few days before Passover (v. 18).

Jesus justified the expulsion of the victim traffickers according to Mk 11.17 EU with a reference to the promise Isa 56.7: “Doesn't the scripture say: My house should be a house of prayer for all peoples?” Accordingly, he did not want the temple service but also to give non-Jews free access to it, which all peoples should have in future. This eschatological “ temple cleansing ” took up the prophetic motif of the future “pilgrimage to Zion ”, which other words of Jesus (Mt 8.11 f .; Lk 13.28 f.) Also recall, and can be interpreted as a call for a corresponding cultic reform .

The following verse stands in tension: But you have made a den of robbers out of it. The expression alludes to Jer 7: 1–15, where the prophet Jeremiah was written around 590 BC. BC announced the destruction of the first temple and justified it with continued violations of law by the Jerusalem priests. They would have used the temple as a hiding place like robbers, invoking God's supposedly safe presence, but denying the poor righteous behavior. The authenticity of this Jesus word is disputed. "Robbers" was the name of the Romans back then, when Zealot rebels liked to hide in caves; the Sadducees, on the other hand, were loyal to them. In the course of the Jewish uprising (66-70), zealots temporarily holed up in the temple; the expression can therefore reflect the retrospective of the early Christians.

It is often assumed that Jesus called for the demolition of the temple (Jn 2.13) and announced its destruction (Mk 13.2) and a new building (Mk 14.58). According to Jens Schröter , Jesus did not intend to build a real temple, but rather, as with his “criticism of the Purity Laws, questioned the constitution of Israel, which was oriented towards the existing institutions” in order to prepare Jews like John the Baptist for a direct encounter with God. According to Peter Stuhlmacher , he made an implicit messiah claim. Stuhlmacher justifies this with apocryphal Jewish texts from the Dead Sea (PsSal 17.30; 4Q flor 1.1–11), which refer to the prophecy of Nathan 2 Sam 7.1–16, which included the construction of the temple with the David dynasty and above all the sons of God connected, expected a future purification and rebuilding of the temple from the Messiah.

For Jostein Ådna, Jesus also provoked the rejection of his call to return, which was linked to the temple action and the temple word, and thus delivered himself up for his execution. For he believed that if his addressees failed to repent, God's saving act could only be enforced through “his atoning death as an end-time substitute for the temple's atonement cult”.

arrest

The temple action is followed by various discourses and disputes between Jesus and Jerusalem priests and Torah teachers who deny the authority of his actions (Mk 11:28) and in doing so follow their plan of killing (Mk 11:18; 12:12). In view of the sympathy of many festival visitors for Jesus, they would have arranged his secret arrest "with cunning" (14.1). Judas Iscariot had unexpectedly offered them help (14:11). The arrest took place the night after the last supper of Jesus with his first called disciples (14.17-26) in the garden of Gethsemane , a place where Passover pilgrims lay at the foot of the Mount of Olives . Judas had led a “great crowd” armed with “swords and poles”, including a servant of the high priest. At a prearranged sign, the Judas kiss , they arrested Jesus. Some disciples tried to violently defend him. He rejected this by accepting his arrest as the predetermined will of God. Thereupon all the disciples fled (14.32.43–51).

This account suggests that the high priest had Jesus arrested by the Jewish temple guard, who was authorized to carry arms, because the previous public conflict in the temple could endanger the power of the Sanhedrin as the central institution of Judaism. The high priest was installed and deposed by the Romans and could only act within the framework of Roman occupation law. The Sanhedrin led by him was obliged to arrest and extradite potential troublemakers. Otherwise the Romans could have robbed him of the rest of his independence, as happened later when the temple was destroyed. Therefore, Jesus' arrest is interpreted as a preventive measure to protect the Jewish people from the consequences of a riot and to preserve the temple cult according to valid Torah commandments. This corresponds to the realpolitical calculation with which the high priest is supposed to have convinced the Sanhedrin according to Jn 11.50 EU and 18.14 EU to arrest Jesus and have him executed: "It is better that one person dies for the people." The Sanhedrin is said to have planned to hand him over to Pilate for execution even before Jesus was arrested, but is considered tendentious editorial staff. Because the temple action did not affect the Romans and did not attack their occupation statutes as long as they did not cause unrest, but endangered the authority and relative autonomy of the high priests in matters of cult.

According to John 18.3.12, a troop of soldiers (Greek speira ) under an officer (Greek chiliarchos ) together with servants of the Sanhedrin arrested Jesus by force of arms. The term speira refers to a Roman cohort . According to contemporary sources, it comprised between 600 and 1000 soldiers. A cohort was permanently stationed in Antonia Castle above the temple precinct to prevent uprisings on high feast days . For the Passover festival it was reinforced by additional troops from Caesarea.

The Jewish historian Paul Winter therefore assumed that Jesus had been arrested on the orders of Pilate, not the high priest, by Roman soldiers, not Jewish temple guards. The occupiers wanted to suppress possible political-revolutionary tendencies which they suspected among Jesus' followers and feared as the effect of his appearance. Wolfgang Stegemann also thinks a Roman participation in Jesus 'arrest is conceivable, since the Romans often nipped rebellious tendencies in Judea in the bud and Jesus' entry and temple action suggested such tendencies for them. Klaus Wengst , on the other hand, considers the Johannine arrest scene to be altogether ahistorical, as an entire cohort would hardly have marched to arrest an individual, would not have handed him over to a Jewish authority and would not have let anyone who resisted escape. The scene is supposed to express the sovereignty of the Son of God over the overwhelming tyranny of the powers hostile to God.

The fact that Mark's report should be drafted promptly is indicated by the fact that he does not mention the names of the opposed disciples differently than usual. These people might have been known to the early Christians in Jerusalem anyway, so they remained anonymous here in order to protect them from Roman or Jewish persecutors. The presumed Roman initiative fits in with Jesus' statement that he was treated like a “robber” (zealot), although he was within reach during the day. But the armed band only arrested him and did not pursue his escaping companions; According to the NT, Pilate did not take action against the Original Christians later either. This suggests a religious rather than a political reason for arrest.

Before the high council

According to Mk 14: 53.55-65, Jesus was then brought to the house of the unnamed high priest, where priests, elders, Torah scholars - all factions of the Sanhedrin - gathered. Jesus was charged with the aim of a death sentence. The witnesses summoned had quoted a word from Jesus: He had prophesied that the temple would be demolished and rebuilt within three days. But their statements would not have agreed and were therefore not legally usable. Then the high priest asked Jesus to comment on the charge. After his silence he asked him directly: Are you the Messiah, the son of the Blessed One? Jesus answered ( Mk 14.62 EU ):

"It's me; and you will see the Son of Man sitting on the right hand of Power and coming with the clouds of heaven. "

The high priest interpreted this as blasphemy and tore his official dress as a sign of it. Thereupon the council unanimously condemned Jesus to death. Some would have beaten and mocked him.

Whether there was such a process and, if so, whether it was legal is highly controversial. It is questionable where the escaped Jesus followers found out details about the course of the process: possibly from the “respected councilor” Joseph of Arimathäa , who buried Jesus. But while Matthew and Mark describe a nocturnal trial with a death sentence, according to Luke 22: 63-71, Jesus is not asked about his messianship by the whole of the Sanhedrin until the following day and is accused against Pilate without a death sentence. According to John 18.19 ff. It is only by Annas interrogated and then without a Council process and death sentence at the then reigning successor Caiaphas , handed over by him to Pilate.

The Markus version describes an illegal process with intent to kill, secret meeting, false witnesses, unanimous death sentence and mistreatment of the convicted person. Later regulations of the Mishnah banned capital processes at night and in private homes, on festive days and associated set-up days. The trial had to begin with exonerating witnesses; Death sentences could not be passed until one day later at the earliest; the youngest councilors should speak their judgment first and freely. In Jesus' time, these rules are unfounded. Josephus contrasted a mild Pharisee enforced after 70 with an earlier harsh Sadducee criminal law practice. However, there is no direct evidence for the latter and for such an urgent procedure that favored killing intentions.

It is also questionable whether the Sanhedrin was allowed to pass death sentences at that time. Inscribed plaques in the inner temple area threatened intruders with death; Whether a formal death penalty or a divine judgment was meant is unclear. Josephus only reported a death sentence from the Sanhedrin for Jesus' eldest brother James, who was stoned around 62 while the governor was vacant. Large council meetings only met on special occasions and had to be approved by the governor of Rome. This kept the official vestments of the high priest, without which he could not make any official judgments.

Because of these sources, some historians consider a regular trial, at least a death sentence by the Sanhedrin, to be an early Christian invention to relieve the Romans after the temple was destroyed and to incriminate Jews. A possible motive for this is the threat to the Christians, who worshiped a person crucified by the Romans, as a criminal organization in the Roman Empire after 70, which increased their demarcation from Judaism.

Others accept exceptional proceedings against Jesus. The fact that he was condemned as a blasphemer of the name of God or seducer of the people to apostasy from YHWH (Deut 13.6; Lk 23.2; Talmud tract Sanhedrin 43a) is usually considered unlikely: because his radically theocentric message of the kingdom of God fulfilled this first of the Ten Commandments , and he paraphrased the name of God just like the high priest. The word of Jesus quoted by the witnesses suggests an accusation of false prophecy (Deut. 18.20 ff.). They are called false witnesses because they testified against the Son of God, not because they misquoted Jesus. You may have accused Jesus of prophesying the impossible and declaring demolishing the Toravid as God's will. One could, however, wait to see whether his announcement would come true before condemning him for it (Deut 18:22). According to the Torah, false prophets should be stoned; only blasphemers and idolaters should be hanged according to the Mishnah (treatise Sanhedrin VI, 4).

The temple priests also persecuted temple and cult critics in other ways, such as Jeremiah (Jer 26: 1–19; around 590 BC) and the " teacher of righteousness " (around 250 BC). Jesus ben Ananias , who in Jerusalem announced by 62 the destruction of the temple and the city, took the Sanhedrin so firm and transferred him to the governor of Rome, of him after a flogging but released her. Council members stoned the original Christian Stephen , who was critical of the temple , after he had accused the Sanhedrin of judiciary murder of Jesus and proclaimed him as the enthroned Son of Man (Acts 7.55 f .; around 36).

The high priest's messiah question after the interrogation of the witnesses seems plausible, since according to the Nathan promise in 2Sam 7: 12-16 only the future successor of David, addressed as God's “son”, was allowed to rebuild the temple. This claim was not necessarily blasphemous for Jews, since other candidates for the Messiah were respected, for example Bar Kochba (around 132) , who was probably called the “son of the star” according to Num. 24.17 .

If there was a capital trial, a self-testimony from Jesus may have triggered the death sentence that was not initially sought. His answer is reminiscent of the vision of the Son of Man in Dan 7:13 f .: He does not appear as a successor to David, but as an authorized representative of God's rule after the final judgment over all world powers. Jesus would have expanded the nationally limited Messiah hope to abolish all tyranny (cf. Mk 8.38 and Mk 13.24 ff.). This would have confirmed the charge of false prophecy for the Sadducees, since they rejected Daniel's apocalyptic as heresy . Here some refer to the exact wording of Jesus' answer: “Sitting at the right hand of God” quoting Ps 110: 1, so that the Son of Man appears as the final judge already enthroned. This was blasphemy for the high priest because Jesus disregarded his judicial office and elevated himself to God's side. Others consider the participle "sitting ...", which divides the sentence structure, to be editorial, since it presupposes belief in Jesus' resurrection and the expected second coming .

Before Pilate

According to Mk 15: 1–15, the “whole council” delivered Jesus tied up to Pilate the following day after a decision had been made to do so. He asked him Are you the King of the Jews? and faced related charges by the Sanhedrin. But Jesus was silent. Then Pilate offered the crowd that had gathered together for the usual Passover amnesty of Jesus' release. But the temple priests had incited the crowd to instead demand the release of Barabbas , a recently imprisoned Zealot. After several unsuccessful inquiries about what Jesus had done, Pilate gave in to the crowd, released Barabbas and had Jesus crucified.

Lk 23: 6-12 supplements an interrogation of Jesus by Herod, who mocks him for his silence, returns him to Pilate and thus becomes his friend. The scene is considered an editorial anticipation of Acts 4, 25-28, according to which a biblically foretold covenant of pagans and kings (Ps 2: 1 f.) Brought Jesus to death. Lk 23.17 ff. Extends the indictment to include allegations that were missing in the Sanhedrin trial: seduction of the people and tax boycott against the emperor of Rome. The Gospels also vary the course of the Passover amnesty (Mt 27:17; Lk 23:16; Jn 18:38 f.). In all versions, the temple priests and their followers carry out Jesus' execution, while Pilate assumes his innocence, but does not release him, but asks for their judgment and finally gives in to their pressure.

A Passover amnesty of that time is nowhere else recorded. According to extra-biblical sources, the Romans took massive action against any prophetically inspired popular gathering in the Judean area. Jewish historians portray Pilate as ruthless, unyielding, corrupt and cruel: he provoked the Jews with emperor symbols in the temple district, ordered massacres (cf. Lk 13: 1) and had Jews constantly executed without trial. According to Roman procedures in subjugated provinces, Pilate could have Jesus executed after a brief interrogation without a formal judgment (coercitio) : the suspicion of seditious behavior was sufficient.

According to Mk 11.9.18, Jesus had; 12.12; 14.2 the sympathy of the pilgrims, who rejected the Roman occupation law, and the narrow inner courtyard of the Pilate's palace offered little room for a crowd. Therefore, public interrogation, referendum, amnesty and declarations of innocence by Pilate are mostly considered ahistorical today and are assigned to an anti-Jewish editorial team of the Passion Report.

The Tacitus note mentions an execution order for Pilate, without which no one was crucified under him. The Gospels presuppose the command by quoting a Roman judgment display, here as a cross : Pilate condemned Jesus as “King of the Jews” (Mk 15.26 par). This reason for the judgment is usually considered historical because the title refers to a politically interpreted claim to the Messiah, agrees with the reason for extradition (Mk 15.2 par) and is plausible against the background of Roman law: The Romans had Jewish vassal rulers wearing the royal title since 4 BC . Forbidden. Jewish leaders of the zealots had also called themselves the “king” (basileus). According to Roman law, this was considered an insult to majesty ( crimen laesae maiestatis (populi Romani) ), incitement to rebellion (seditio) and subversive uprising ( perduellio ) , since only the Roman emperor was allowed to appoint or depose kings. If Jesus 'interrogation went as shown, Pilate had to take Jesus' answer to the question about a presumed royal dignity (“You say it”) and his subsequent silence as a confession that forced his death sentence.

With Jesus' execution between Zealots, Pilate probably wanted to set an example against all rebellious Jews and mock their hope for the Messiah. Accordingly, the editorial verse John 19:21 interprets the protest of the Sadducees: Jesus only claimed to be the Messiah. For the early Christians, the title of the cross confirmed their unjust judgment, since Jesus had not planned an armed uprising (Lk 22:38), and Jesus' hidden true identity as Kyrios Christ , the ruler of all lords (Rev 19:16).

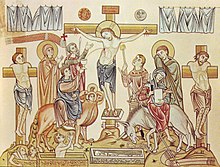

crucifixion

The crucifixion was the cruelest method of execution in the Roman Empire , which was mostly used against insurgents, runaway slaves and residents without Roman citizenship . It should humiliate eyewitnesses and deter them from participating in rioting. Jews saw it as being cursed by God (Deut 21:23; Gal 3:13). Depending on how it was carried out, the agony could last for days until the crucified died of thirst, suffocated from his own body weight or died of circulatory failure. The Markinian Passion Report does not give any details about the physical process, but only about the behavior of perpetrators and witnesses, about the last words of Jesus and the duration of his death.

According to Mk 15: 15-20, the Roman soldiers stripped Jesus, put a purple robe on him, put a crown of thorns on him and, according to Pilate's judgment, mocked him as “King of the Jews” in order to mock the messianic hope of the Jews. Then they would have hit him and spat on him. A scourging was an integral part of the Roman crucifixion and was often done so brutal that the convict already died from it.

According to verse 21, Jesus himself had to carry his cross to the place of execution in front of the city wall. When he, weakened by the blows, collapsed, the soldiers forced Simon of Cyrene , a Jew who happened to be working in the fields, to carry his cross. The fact that the original Christians handed down his name and that of his sons decades later is interpreted as solidarity between the original Christians and Diaspora Jews.

According to verse 23, the soldiers offered Jesus myrrh in wine before crucifying him; he refused this potion. The crucifixion began at the third hour (around 9 a.m.) (v. 25). Then they would have drawn for his robe. According to verse 27, Jesus was crucified together with two “robbers” (zealots or “social bandits”) on the hill of Golgotha (“place of the skull”) in front of the then Jerusalem city wall, accompanied by scorn and mockery from those present. Around the sixth hour a three-hour darkness set in (v. 33). Towards the end of this, Jesus called out the Psalm quotation Ps 22.2 EU in Aramaic : “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (V. 34) Then he accepted a sponge soaked in wine vinegar ( Posca ) from a Jewish hand (V. 36) and died immediately afterwards with a loud cry (v. 37). The death occurred at the "ninth hour" (around 3 p.m.).

The lesson schedule, the darkness, allusions to psalms and psalm quotations are considered theological interpretation, not historical details. They place Jesus among the unjustly persecuted Jews who are surrounded by the violence of all enemies and who appeal to God's justice.

Entombment

According to Mk 15: 42–47, Jesus died before nightfall. Therefore, Joseph of Arimathea asked Pilate to be allowed to remove him from the cross and bury him. Pilate, astonished at Jesus' rapid death, had his death confirmed by the Roman overseer of the execution and then released his body for burial. According to Jewish custom, Josef wrapped him in a cloth that evening, placed him in a new rock grave and closed it with a heavy rock. Mary Magdalene and another Mary, who accompanied Jesus' death with other women from Galilee, observed the process.

Romans often left those killed on the cross for days and weeks to deter and humiliate their relatives until they decay, disintegrate or were eaten by birds. For Jews, this violated the provision of Deut. 21: 22-23, according to which the executed person who was "hung on a wood" should be buried on the same day. According to Josephus ( Bellum Judaicum 4,317) Jews crucified by Romans were allowed to be buried according to Jewish custom. This is interpreted as consideration of the Romans for the feelings and religion of the Jews; in the case of Jesus, so as not to cause unrest at the Passover festival.

The legal burial of a convicted person may have been part of the Sanhedrin's mission. Then Joseph of Arimathea would have acted on his behalf. This calls into question the unanimous death sentence for blasphemy. The fact that the Markus report mentions the official examination of the death of Jesus should probably confirm this against early false death theses. The names of the witnesses to Jesus' death and burial were apparently known in the early Jerusalem community. They were probably remembered because only they knew Jesus' tomb after the escape of the disciples. They are said to have found them empty the morning after next (Mk 16: 1-8).

The location of the tomb of Jesus is unknown. The NT contains no references to its veneration. Some historians suspect it to be under today's Church of the Holy Sepulcher , because there is archaeological evidence of grave worship from the 1st century.

Historical research examines NT texts on events after Jesus' burial only in the context of the history of the early Christian belief in the resurrection.

literature

swell

- Eberhard Nestle , Barbara Aland : Novum Testamentum Graece. 28th edition. German Bible Society, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 3-438-05159-1 ( bibelwissenschaft.de ).

- Wilhelm Schneemelcher : New Testament Apocrypha in German translation . Two volumes. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1999, ISBN 3-16-147252-7 .

Historical environment

- Werner Dahlheim : The world at the time of Jesus. Beck, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-65176-2 .

- Amy-Jill Levine, Dale C. Allison Jr., John Dominic Crossan: The Historical Jesus in Context. Princeton University Press, Princeton 2006, ISBN 0-691-00991-0 .

- Craig A. Evans: Jesus and His Contemporaries: Comparative Studies . Brill Academic Publications, Leiden 2001, ISBN 0-391-04118-5 .

- Gerhard Friedrich , Jürgen Roloff, John E. Stambaugh, David L. Balch: Outlines of the New Testament . In: The Social Environment of the New Testament . tape 9 . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1992, ISBN 3-525-51376-3 .

- Johann Maier : Between the wills. History and Religion in the Second Temple Period . In: The New Real Bible . Supplementary volume 3. Echter, Würzburg 1990, ISBN 3-429-01292-9 .