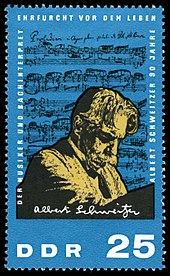

Albert Schweitzer

Ludwig Philipp Albert Schweitzer (born January 14, 1875 in Kaysersberg in Upper Alsace near Colmar , (then) German Empire ; † September 4, 1965 in Lambaréné , Gabon ) was a Franco-German doctor , philosopher , Protestant theologian , organist , musicologist and pacifist . He is considered one of the most important thinkers of the 20th century.

Schweitzer, the "jungle doctor", founded a hospital in Lambaréné in Gabon, Central Africa. He published theological and philosophical writings, works on music, especially on Johann Sebastian Bach , as well as autobiographical writings in numerous and highly regarded works. In 1953 he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for 1952, which he accepted in 1954.

biography

Early years and education

Schweitzer came from an Alemannic - Alsatian family. He was born the son of the parish administrator Ludwig (Louis) Schweitzer, who looked after a small Protestant community, and his wife Adele, née. Schillinger, the daughter of a pastor from Mühlbach. At that time his homeland belonged to Germany as the realm of Alsace-Lorraine . In the year of his birth, the family moved from Kaysersberg to Günsbach . His mother tongue was the Alsatian local dialect of Upper German . French was also spoken in his family. The high German learned Schweitzer only at school. He spoke German and French almost equally well.

After graduating from high school in Mulhouse in 1893 , he studied theology and philosophy at the University of Strasbourg (first theological exam in 1898) and was a member of the Wilhelmitana Strasbourg student union founded in 1855 . He also studied the organ in Paris with Charles-Marie Widor , with whom he had taken occasional lessons since 1893, and the piano with Marie Jaëll .

In 1899, after a short study visit to the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Berlin , he was awarded a doctorate in Strasbourg with a dissertation on The Philosophy of Religion of Kant from the Critique of Pure Reason to Religion within the Limits of Reason. phil. PhD. In 1901 the theological dissertation for Lic. Theol. Critical presentation of different more recent historical conceptions of the Lord's Supper (first edition 1906), the second version of which bears the title History of the Life of Jesus Research (Tübingen 1913).

In 1902 he completed his habilitation in Protestant theology at the University of Strasbourg with the text The Secret of Messiahship and Suffering . With his habilitation he became a lecturer in theology at the University of Strasbourg. Since 1898 he was teaching vicar and from November and second theological examination ordained vicar at the Church of St. Nikolai . Some of his sermons and sermon drafts there have been preserved by the hand of his friends Annie Fischer, widow of the Strasbourg professor of surgery, Fritz Fischer , and sister of Hugo Stinnes . His theology resonated with Fritz Buri , among others . In 1905 Schweitzer wrote his book on Johann Sébastien Bach in French , which was followed by a newly written German Bach monograph in 1908.

In 1905 Schweitzer was rejected as a missionary at the Paris Mission Society because of his liberal theological views. From 1905 to 1913 Albert Schweitzer studied medicine in Strasbourg with the aim of working as a missionary doctor in French Equatorial Africa . The enrollment for the study of medicine was very complicated. Schweitzer was already a lecturer at the University of Strasbourg. Only a special permit from the government made studying possible. In 1912 he was licensed as a doctor, in the same year he was awarded the title of professor of theology on the basis of his "commendable scientific achievements". In 1913 his medical doctoral thesis followed : The psychiatric assessment of Jesus: Presentation and criticism . In this work, analogous to his theological dissertation, he refutes contemporary attempts to illuminate the life of Jesus from a psychiatric point of view. Thus, at the age of 38 and before he went to Africa, he had received his doctorate in three different subjects, had completed his habilitation and was a professor.

Albert Schweitzer married Helene Bresslau (1879–1957) in 1912 , the daughter of the Jewish historian Harry Bresslau and his wife Caroline, née Isay. In 1919 the daughter Rhena Schweitzer-Miller († 2009) was born, who continued her father's foundation until 1970.

Life as a medic in Africa and Europe

In 1913 Schweitzer put his plan into practice and founded the Lambaréné jungle hospital on the Ogooué , a 1200 km long river in Gabon . The area was then part of French Equatorial Africa . As early as 1914, when the First World War broke out, he and his wife Helene, a teacher, were placed under house arrest by the French army because of their German citizenship.

In 1917, exhausted from more than four years of work and a kind of tropical anemia, the Schweitzer couple were arrested, transferred from Africa to France and interned in Bordeaux , Garaison and then St. Rémy de Provence until July 1918. Albert used this time to develop and expand his ethics of respect for life . Central to this ethic is the sentence: "I am life that wants to live, in the midst of life that wants to live."

Towards the end of the war, they returned to Alsace in 1918 , which was reconnected to France on December 6th. There Schweitzer took French citizenship , but he liked to describe himself as an Alsatian and a "citizen of the world". He again took up the position of vicar in St. Nikolai in Strasbourg and entered a Strasbourg hospital as an assistant doctor.

Thanks to the Swedish bishop Nathan Söderblom , Albert Schweitzer was able to give lectures in Sweden from 1920 on his ethics of reverence for life, pay off his debts through organ concerts and earn money for his return to Africa in 1924 to expand the jungle hospital there.

Albert Schweitzer was best known for his autobiography "Between Water and Primeval Forest", which he had written in a short time in 1920. In his speech on the 100th anniversary of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's death in 1932 in Frankfurt am Main , Schweitzer warned of the dangers of the emerging National Socialism. Attempts by Joseph Goebbels to invite Schweitzer, who was staying in Lambaréné, and to win them over to the Nazi ideology, he politely rejected the request, which was closed with German greetings , with Central African greetings .

He received much public honor after World War II. In his acceptance speech for the 1952 Nobel Peace Prize awarded in 1954, Schweitzer clearly spoke out in favor of a general rejection of war: “War makes us guilty of inhumanity”, Albert Schweitzer “quotes” Erasmus from Rotterdam . As a result of the Geneva Convention of 1864 and the founding of the Red Cross, there was a "humanization of war" which would have led to the fact that in 1914 people did not take the beginning World War I seriously in the way they should have done .

In part, Schweitzer were accused of racist, paternalistic and pro-colonialist attitudes. He criticized Gabon's independence because the country was not yet ready for it. Chinua Achebe reported that Schweitzer had said that Africans were his brothers, but his "younger brothers". The American journalist John Gunther visited Lambaréné in the 1950s and criticized Schweitzer's paternalistic attitude towards Africans. They would also not be used there as specialists. After decades that Schweitzer had already worked in Africa, the nurses still came from Europe.

In 1961 he became an honorary member of the Church of the Larger Fellowship, affiliated with the Unitarian Church of North America .

The teaching of reverence for life

The problem of ethics in the higher development of human thought

In 1962, Schweitzer assumes, in the quintessence of his philosophical thinking, that when people think about themselves and their limits, they recognize each other as brothers who think about themselves and their limits. In the course of the civilization process, the solidarity , which was originally only related to one's own tribe, is gradually transferred to everyone, including unknown people. These stages of cultural development are preserved in world religions and philosophies.

Analogously, in the world-negating religions of the Indian cultural area, according to the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer, there is an expansion of compassion, which in Brahmanism is based beyond (true) metaphysics in the suffering of the (false) material world and is therefore rejected, in Buddhism with reference to an expanded one Metaphysics is required and integrated into everyday life in Hinduism , which is understood as a game of the gods with people ( Bhagavad Gita ). The demanded indifference to suffering obliges to pacifism . Schweitzer also referred to Mahatma Gandhi .

The spread of the world-affirming Zoroastrianism of Persian settlers, united in solidarity against pagan nomads, also influenced Greek philosophy, in which the Stoic Panätios justified world affirmation with an all-embracing reason, in which Seneca , Epictetus and Marc Aurel developed humanism as a virtue of all virtues .

In the melting pot of Persian and Greek cultures, Judaism and Christianity had emerged, which see the world as true but imperfect. Christianity calls for the renunciation of the world to expand the good in man and, in search of the commandment of all commandments, also finds the ideal of humanism.

Since the Renaissance, the virtue of all virtues directed outside and the commandment of all commandments directed inside have grown together into a secular right (Erasmus of Rotterdam), the basis for the utilitarianism of Jeremy Bentham , while David Hume assumes a natural empathy as the cause. Immanuel Kant connects this with dualism and relocates morality in the form of the categorical imperative into the nature of man who lives in the spiritual world as a subject and in the objective world is only an object .

The frequent failure of the moral claim makes the good conscience of a myth , while the civilization , the confidence and the sense of the sequence of resignation and reactive sentimentality undermines. In order for this pressure to lead to the subject understanding his being as the “will to live in the midst of the will to live” of others and to underpin this experience with Jesus' commandment to love , guidance is required. Then it combines the commandments of conscience in the form of the categorical imperative in the spiritual world with the virtues in the objective world and recognizes the difference between bad and good as an expression of life-damaging and life-promoting effects and finds in this the highest moral value .

This moral value enables a view of life in which the affirmation of life is not a category of knowledge, but a category of will, denial of life lies in the consideration of the will of others and denial of life consists in the internalizing, self-collecting ( music ) and perfecting commandment, including one's own life from a calling to raise the moral value of ethics, the folk wisdom of "what you do not want to be done to you, do not do it to anyone else" to "love your neighbor as yourself" and apply it to all living things.

"Ethical Culture". Man and creature

Decisions between morality and practical necessity lead to preoccupation with the ideal of ethics into which the human being grows. Responsibility needs an individual, social and political will, which gives one's own existence a spiritual value and creates a relationship to the objective world in which the person moves from a naive to a deepened world affirmation. Elementary thinking is the prerequisite for an understandable and convincing ethic that, when dealing with reality, acts like leaven in bread.

The interpersonal relationship is characterized by strangeness and coldness, because nobody dares to be as warm as they are. The overcoming roots the warmth in the reverence for life and helps to a kindness in modesty, because with every decision one is thrown back on oneself again and again and threatens to resign. But young people in particular have the energy to question the resigned reasonableness of the mature personality and have the courage to adjust a moral compass for a life-enhancing handling of practical constraints.

Since the creature is defenselessly exposed to human arbitrariness , ethical decisions include arbitrariness and do not damage life out of thoughtlessness or indifference. Compassion for animals, despite their alleged soullessness, is not sentimentality, because all necessary killing is a reason for grief and guilt, which one cannot escape, which one can only reduce.

Albert Schweitzer has switched to a vegetarian diet to protect the animals. “My view is that we, who advocated the protection of animals, completely renounce the consumption of meat and also speak against it. So I'll do it myself. "

Nuclear war or peace

In pacifism , often ridiculed as utopia , Schweitzer sees a vital counterweight to the stalemate of deterrence . The attitude of inhumanity wants to maintain the freedom of choice over war or peace as a prerequisite for guaranteeing peace with a position of strength. It overlooks the threat to strength from the expansion of practical constraints on armament, with the consequence of an increase in the risk of war as a self-fulfilling prophecy ( armament spiral ). She does not notice that the winner does not benefit from victory either.

Despite all doubts, Schweitzer advises unilateral disarmament for fear of the attitude of inhumanity. Since resigned reason does not recognize that wars of annihilation create more problems than they solve, the reverence for life can only with courage develop the hope with which the public develops the idea of a world-affirming culture and takes responsibility for war and peace.

Connections to other philosophical currents

Individuals face an absolute reality which, because of its transcendence, is so incomprehensible that they can only set up their individual worlds of imagination in which, separated into object and subject, the will of absolute reality is reflected. The will in itself is on the one hand free, but blind, on the other hand seeing, since it is determined by one's own imagination ( determinism ), but unfree. Therefore the subject can no longer use the will to differentiate between creation and destruction and develop meaning. Schweitzer sees the essence of overcoming this paradox a priori in the human being, the inner being is correspondingly externalized . The critical examination of the existential philosophy that had become popular in France occupied Schweitzer in the last years of his life; Jean-Paul Sartre was the son of Schweitzer's cousin Anne-Marie. Sartre's existentialism is based on the same ideas: The senselessness is offset by the free responsibility of the individual conscience, which, however, in its self-centeredness creates its essence in intersubjectivity through the advocacy of certain values: external influences are internalized accordingly.

Theological work

Albert Schweitzer saw himself primarily as a philosopher. As a student of the Strasbourg New Testament scholar Heinrich Julius Holtzmann , a leading exponent of historical-critical research of his time, Albert Schweitzer also dealt with theological topics throughout his life, in particular questions of biblical interpretation and theology of the New Testament as well as the topic of religious mysticism .

History of the life of Jesus research

In all historicist drafts of the life of Jesus, Schweitzer only recognizes the projections of the researchers concerned, who read their own assumptions and ideas about Jesus into their representation. Schweitzer considers none of the attempts of the liberal theology of his time to approach the authentic figure and message of Jesus Christ by means of historical reconstruction to be successful. He only takes Johannes Weiß's work seriously. While, according to Johannes Weiß, only Jesus 'sermon was determined by the idea of the imminent end of the world and the dawn of the kingdom of God, Schweitzer claims that Jesus' actions are also determined by this near expectation . This position is called consequent eschatology in theology. Schweitzer emphasizes the great gap between the Jesuan worldview and the worldview of his own modern times. Due to this distance, the Galileans encounter us again like an unknown who has to be rediscovered from the ground up. Although many later theologians refer to Schweitzer regarding the impossibility of an authentic reconstruction of the life of Jesus, he himself was less pessimistic in this regard than e.g. B. Rudolf Bultmann .

In the final considerations he shows that the research into the life of Jesus wanted to bring Jesus into our time. He emphasizes that a lot has been achieved and describes the life of Jesus research as a “uniquely great act of truthfulness”. Nevertheless, he has points of criticism. The attempts to modernize the image of Jesus failed because Jesus cannot be held fast in our time. He remains in his own time and has his own ideas: he works with Jewish eschatology and lives with Jewish metaphysics. However, “to weaken and reinterpret what is temporally conditioned in his preaching” does not mean that “he would thereby become more to us”. In general, no person can be brought back to life through historical observation. Therefore, our relationship with Jesus is a mystical one. We enter into a relationship with him by recognizing a common want and concern and finding ourselves in him. We let his will clarify, enrich and enliven our will. The Christian religion is therefore not a cult of Jesus, but a mysticism of Jesus. Similar to the disciples at Lake Tiberias (Jn 21), Jesus comes to us as “an unknown and nameless person”. And he calls us to "You follow me!"

"And to those who obey him, wise and unwise, he will reveal himself in what they are allowed to experience in his community in terms of peace, work, struggle and suffering, and they will find out who he is as an inexpressible secret."

The mysticism of the apostle Paul

In his investigation of Paul Schweitzer emphasizes his mystical dimension, from which Paul only considers the ethics of Jesus and the mythological dimension of his crucifixion and resurrection as Christ and the parousia delay as a call for the worldwide spread of Christ's teaching as a prerequisite for the beginning of the kingdom God interprets, especially since Christians have already become part of the kingdom in this world (e.g. Romans 6, 1–14, Ephesians 2.5 ff). The conversion of Gentiles to Christ promoted by Paul makes the Christian community (and later the Church) the real legacy of Jesus beyond the limited circle of disciples; His crucifixion is not the end, but the beginning of the eschatology that is to be completed by the second return of the “Son of God”. Both Schweitzer's interpretation of the figure of Jesus and his view of Paul were rejected by the overwhelming majority of contemporary theologians.

music

Albert Schweitzer was a well-known organist, musicologist, theoretician of organ building and one of the style-defining interpreters of Johann Sebastian Bach's music for the 20th century.

The organ reform

Schweitzer's views on organ playing are inseparable from his religious ideas. So he means z. B. with regard to the reproduction of organ works in the concert hall:

“Through the choice of pieces and the way they are played, I try to turn the concert hall into a church. [...] Due to its even and permanently sustainable tone, the organ has something of the eternal quality about it. Even in profane space it cannot become a profane instrument. "

As one of the main exponents of the so-called Alsatian-New-German organ reform, Schweitzer had been promoting a new type of organ since the beginning of the 20th century against the instruments customarily built in Germany at the time: This organ should have the balanced plenum sound of the French late-romantic organ Cavaillé-Colls , the fusible reed voices of the German and English romanticism and the richness of overtones of the old classical organs of Alsace (" Silbermann organs ") combine. A new console design should combine the logic and clarity of the French play system and the playing aids commonly used in Germany ( German and French organ building and organ art. Leipzig 1906).

In Alsace in particular, several organs were built according to Schweitzer's ideas. Reformer organs with a large number of registers were created in St. Reinoldi , Dortmund (1909, V / P 105, extended by a Rückpositiv with six registers in 1939, destroyed in 1943/44), and Sankt Michaelis, Hamburg (1912, V / P 163, after war damage in 1943 by the New building from 1962 replaced). After the end of the Second World War, with the increasing importance of the organ movement , Schweitzer's ideas about the organ were initially largely out of date. With the renewed appreciation of the organ of the 19th century, with the enthusiasm for organ building and organ music of the French late Romanticism since the 1970s, many new organs, especially in German-speaking countries, which strive for a synthesis of various historical stylistic elements, show a proximity to Schweitzer's ideas. Schweitzer worked to raise awareness of the growing appreciation of old organs in the early 20th century. During his time in Africa, too, he repeatedly advocated the preservation of historical instruments and accompanied new buildings with his advice.

The stream arch

In addition to the organ, Schweitzer was also involved in violin making, more precisely with the violin bow . The starting point was his criticism of the playing of the polyphonic passages in Bach's solo violin sonatas and suites for solo cello . With the modern, stiff, slightly concave bow, only two strings can be made to sound at the same time. As a stopgap, arpeggiate or work with interval decomposition, i. H. first the lower two notes are played, then the upper two notes. Schweitzer was disturbed by the breaking of the chords, the associated scratching noises, the pauses between the chords, the constant forte and the nonsensical voice guidance. On the other hand, he assumed that four-part violin playing was actually possible and common in Bach's time and was confirmed in reports, for example, about the North German musician and Bach's older contemporary, Nicolaus Bruhns . The key was to use a convex bow, the hair of which can be relaxed while playing so that all strings can be painted at the same time. Schweitzer saw the only way to solve the problem in a new design; Together with the violinist Rolph Schröder , he developed a convex bow with a lever device at the lower end, with which it was possible to relax the hair while playing. He called this bow "Bachbogen", knowing full well that it was not a historical instrument from Bach's time, but a new construction. Today this arch is called a round arch . Some violinists practice this game today, including Rudolf Gähler , who has recorded a recording of all of Bach's sonatas and partitas for solo violin and has also published a book on this subject. The violinist Philippe Borer particularly pointed out the four-part works for violin solo by Niccolò Paganini , which can be realized with a round arch. In the 1990s, the cellist Michael Bach designed his own round arch, initially for contemporary music and later also a flatter round arch for Bach's suites for solo cello. Mstislav Rostropovich took part in this development work .

Bach interpreter

As a Bach interpreter, Schweitzer turned against the, in his opinion, exaggerated dynamic and color differentiation of the late romantic organ playing, as it had been established in Germany and Central Europe since the mid-19th century under the influence of the Liszt School. He was strengthened in this by his knowledge of the French tradition of playing Bach and his studies with Charles-Marie Widor , composer and organist at Saint-Sulpice in Paris.

“Because Bach's music is architecture, crescendi and decrescendi, which correspond to emotional experiences in Beethoven's and Post-Beethoven's music, are not appropriate. An alternation between strong and weak makes sense in it insofar as it serves to emphasize main clauses and subordinate clauses to recede. Only within these forti and piani are declamatory crescendi and descrescendi appropriate. If you blur the difference between forte and piano, you destroy the architecture of the piece. "

Schweitzer advocated a uniform, cautiously terraced dynamic registration for Bach's independent organ works. The louvre rocker should only be used for large-scale increases and to trace melodic arcs. The use of the Crescendo pedal (roll) the solo presentation of old organ music was Schweitzer as inartistic. As an interpreter, he avoided extremes. He preferred slow tempos, which, in his opinion, guarantee the comprehension of the polyphonic structures, corresponded to the performance practice in Bach's time, and saw in playing too fast the unsuccessful attempt to compensate for the lack of plasticity in the performance. He also practiced a reserved agogic . According to Schweitzer, the phrasing should always be subordinate to the respective form context. He rejects both staccato and legato throughout.

“While in the middle of the 19th century, strangely enough, people played Bach staccato throughout, afterwards they went to the other extreme, playing him in monotonous legato. So I learned it from Widor in 1913. Over time, however, it occurred to me that Bach demands lively phrasing. He thinks as a violinist. The notes are to be connected to each other and separated from each other in the way that is natural for the violin bow. [...] It is completely wrong to think that the monotonous bond best meets the requirements of the master. "

In Lambaréné, after his work in the hospital, Schweitzer played on a tropical piano with organ pedal that was specially built for him. He also practiced for his recordings and the organ concerts, the proceeds of which went to his charitable work. His recordings of Bach's works in Allhallows Barking-by-the-Tower, London (December 1935), and Sainte-Aurélie, Strasbourg (October 1936), as well as on the small organ of the parish church in Günsbach, built according to his ideas in 1931 (early 1950s - Years) with works by Bach, Franck and Mendelssohn are available in various re-releases.

Monograph JS Bach

Schweitzer's organ teacher Charles-Marie Widor also suggested a book on Johann Sebastian Bach, through which the French organ world should become more familiar with the Protestant church music that is fundamental to Bach and its verbal references ( Jean-Sébastien Bach, le musicien-poète. Paris a. Leipzig 1905). Widor himself, a friend of Schweitzer, wrote the foreword. He also advised a German version, which resulted from a complete revision of Schweitzer's great Bach monograph ( Johann Sebastian Bach. Leipzig 1908), also provided with a foreword by Widor. While the biographical details and the dating, especially of the cantatas, have been largely overtaken or expanded by Bach research, the Bach monograph is still a standard work of great importance in the history of humanities and science in terms of music aesthetics. Schweitzer particularly emphasizes the conventionalized use of themes and motifs, keys and instruments in J. S. Bach's work. In doing so, he made the rhetorical quality (“sound speech”) of early music and the importance of the doctrine of affect a subject relatively early on, without using the terms . He saw the key in the cantatas. He found recurring, very figurative motifs, most noticeable in the description of movements such as walking, running, falling, falling down or movement-intensive things such as snakes, waves, ships, wings, as well as abstract, certain affects such as joy, sadness, pain or laughter , Sigh, groan, cry descriptive motifs. Schweitzer presents this musical language systematically and gives the Bach interpreter hints on how to articulate and design individual motifs in order to work out the underlying images. It also shows that, for example, the organ chorale arrangements contain this language and that understanding and performing this music requires knowledge of the chorale text.

Schweitzer probably got an important food for thought from Richard Wagner's completely different leitmotif , whose music he valued very much. However, in the chapter "Poetic and picturesque music" of his Bach monograph he works out the fundamentally different approaches of the two composers when dealing with themes and motifs. With Wagner and other “poetic” musicians, the attempt is made to transfer a dramatic event to the audience as “aesthetic associations of ideas” with the music; together with their (guiding) motifs, they were directed towards feeling. Bach and other “painting” musicians depicted the events in pictures or successive pictures. Their motifs and themes addressed the imagination of the audience.

Editor of Bach's organ works

Schweitzer was also co-editor of an edition of Bach's organ works. The first five volumes of Bach's organ works were published in 1912/13 in German, English and French by the American music publisher Schirmer, New York. The editors were Charles-Marie Widor and Albert Schweitzer. They contain the preludes, toccatas, fantasies, fugues, the canzona and passacaglia, as well as the concerts and trio sonatas. Volume VI was published in 1954, volumes VII and VIII did not follow until 1967 after Schweitzer's death. The edition presents the pure musical text without any additions by the editor, such as fingerings, information on dynamics, tempo, articulation and phrasing. Instructions for understanding and interpreting the works are given in the respective prefaces. With the renunciation of any intervention in the musical text, in order to come close to the composer's intention, this edition is a pioneering achievement at a time when the so-called instructive editions with their subjective changes and additions by the editors were very common.

Political impact

Commitment to nuclear armament and war

Albert Schweitzer tried to avoid being drawn into political disputes as much as possible. However, this changed with his engagement against nuclear armament . As early as April 14, 1954, he wrote a letter to the editor in the Daily Herald , London, “The consequences of the hydrogen bomb explosion are a most frightening problem. ... It would be necessary for the world to listen to the warning calls of individual scientists who understand this terrible problem. In this way mankind could be impressed, gain understanding and understand the dangers in which they find themselves. ”During the speech on the occasion of the presentation of the Nobel Peace Prize on November 4, 1954 in Oslo, entitled The Problem of Peace in Today's World , he spoke again on the danger of nuclear armament.

Albert Schweitzer was urged by several friends, including Albert Einstein and Otto Hahn , to use his authority against nuclear armament. He hesitated, however, because at first he did not feel competent enough. However, the publicist Norman Cousins finally convinced him . After he had dealt intensively with the scientific foundations of atomic physics and the consequences of nuclear weapon tests and had written and personally interviewed experts such as Werner Heisenberg , Frédéric Joliot-Curie and Albert Einstein, he broadcast on April 23, 1957 on Radio Oslo an "appeal to humanity". This appeal received worldwide attention and was broadcast on 140 channels. On April 28, 29 and 30, 1958, three further appeals followed, "Refraining from experimental explosions", "The danger of a nuclear war", "Negotiations at the highest level", which were read out by the President of the Norwegian Nobel Prize Committee, Gunnar Jahn . They were printed under the title "Peace or Nuclear War". In 1958, along with Otto Hahn, Schweitzer was one of the most prominent signatories of a signature collection initiated by Linus Pauling among well-known scientists against nuclear tests . Schweitzer also joined the American peace group National Committee for a sane nuclear policy (SANE) founded in 1957 .

Schweitzer was violently attacked for his commitment and his statements in addition to multiple approval. The Neue Zürcher Zeitung wrote on September 10, 1958 under the title “Strange Albert Schweitzer”: “The venerated name of Albert Schweitzer must not prevent you from establishing that this document is politically, philosophically, militarily and theologically worthless. The risk he takes on the West is monstrous in and of itself. The judgment on America and the Soviet Union on the other hand makes it completely impossible to seriously consider Albert Schweitzer's advice. "

After the trial ban agreement was concluded in 1963, Schweitzer wrote to congratulate John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev on their "courage and vision to initiate a policy of peace". However, in the same year he again protested publicly against the underground nuclear weapons tests that were still permitted under the treaty .

Criticism of his charitable work

At the end of the 1950s - based on the journalist John Gunther ( Der Spiegel of July 3, 1957) - Schweitzer's admiration gave way to a critical inventory of his hospital. At the time, this criticism was rejected by Edmund Duboze, who was then General Inspector of the Military Medical Service in Gabon. Siegwart-Horst Günther , Schweitzer's employee, describes the criticism as superficial, subjective and hateful.

Many critical statements were ostensibly directed against Schweitzer's activities in Lambaréné, but were obviously aimed at discrediting his public reputation as a Nobel Peace Prize laureate in connection with his engagement against nuclear armament ( appeal to humanity of April 23, 1957) and for the peace movement from the mid-1950s Years. Theodor Heuss , whom he knew from his youth and whom he married when he married , objected to Schweitzer's correspondence with Walter Ulbricht and the contacts with the DFU .

André Audoynaud, medical director of the Hôpital Administratif in Lambaréné from 1963 to 1966, criticized Schweitzer for exaggerating his development work because Lambaréné was already integrated into the colonial system and civilization. Despite large donations, he had not modernized his hospital and left it unelectrified, tolerated unsanitary and disease-promoting conditions on the grounds of love for animals, operated symptom courier and blindly transferred the European model of patient care. In addition, he cultivated a colonial style of leadership, forced black relatives of sick people to labor and beat them. He was - arrested in the 19th century - remained a stranger in Africa, had achieved little despite great support, but adorned himself with foreign feathers in a media-effective manner.

This review was only published in 2005; there are virtually no eyewitnesses left to investigate the allegations. Individual allegations can also be refuted: In the documentary film " Albert Schweitzer ", a black doctor prepares for an operation. At least in 1964 the operating room was provided with a generator and equipped with electric operating lights.

In his biography of Albert Schweitzer, published in 2009, the theologian Nils Ole Oermann described him as a “master of self-staging”, without denying Schweitzer's great achievements. Oermann's catchphrase was picked up a few years later by the theologian Sebastian Moll and made a book of its own. Moll contrasts the historical Albert Schweitzer with his autobiographical alter ego and comes to the conclusion that Schweitzer's autobiographical information often serves to positively present one's own personality.

Afterlife

Albert Schweitzer Hospital in Lambaréné

In 1964, a year before his death, Schweitzer transferred the medical management of the hospital to the Swiss doctor Walter Munz (* 1933), who worked in Lambaréné from 1961 to 1971 and later served on the Board of Trustees for many years.

Since it was founded in 1913, the hospital has been rebuilt four times (1913 and 1924 in Andende , 1927 and 1981 in Lambaréné) in order to adapt it to patient needs and medical advances.

In 1961 the medical team consisted of a Japanese, a Hungarian, an American and two Swiss. The twelve qualified nurses came from the Netherlands, Alsace, Germany, Great Britain, Sweden and Switzerland. Forty healing assistants, laboratory assistants, nurses and auxiliary midwives came from Africa and had been trained in Lambaréné. The hospital was economically, administratively and technically independent. In addition to a large vegetable garden and fruit plantations, there were 250 sheep and goats, a joinery, mechanic and electrician workshop, laundry, kitchen and bakery. The main hospital, located on the river, consisted of a village with 70 simple wooden houses with corrugated iron roofs and could accommodate 470 inpatients. In the nearby Village de Lumière (Lambaréné's first hospital), 70 leprosy patients were cared for. 100 to 200 patients were treated on an outpatient basis every day. The patients came from villages within a radius of 600 kilometers. In keeping with Schweitzer's ethics of reverence for life, sick animals - dogs, sheep, goats, pelicans, antelopes and monkeys - were treated in twenty enclosures.

In 1991 the entire hospital complex accommodated well over a thousand people, the main hospital had 226 beds. The main medical areas of curative and preventive medicine as well as training and medical research were carried out by an international workforce, the majority of whom came from Gabon. The hospital has been run by an international foundation since 1974, in which the Gabonese have a majority and in which the most important supporting countries are represented.

In 2015 the new maternity ward (Maternité) financed by the Swiss Aid Association was opened.

Association Internationale de l'œuvre du Dr. Albert Schweitzer de Lambaréné

After Albert Schweitzer's death, the Association Internationale de l'œuvre du Dr. Albert Schweitzer de Lambaréné (AISL) heiress of the hospital and managed it from Europe. In 1974 the hospital was transferred to its own foundation, and the AISL set itself the task of preserving and spreading the intellectual work and philosophy of reverence for life.

In 1967, Alida Silver set up the archive and museum in Albert Schweitzer's house in Günsbach . Today there are 10,000 letters from Schweitzer and over 70,000 letters written to him. This includes many manuscripts of his published and unpublished books and sermons. All important documents are recorded on microfilm. Newspaper clippings, slides, films, tapes and video cassettes, audio tapes and records are also collected, which record speeches and organ concerts by Schweitzer or reports about the hospital in Lambaréné and thus provide an insight into his life, work and thinking.

All important Albert Schweitzer associations around the world are members of the AISL.

Name sponsorships

The number of facilities and events associated with the name Albert Schweitzer is unmanageable. The Albert Schweitzer tournament , an important basketball tournament for youth teams from Europe and overseas , should be mentioned as an example for the sporting sector . In memory of Albert Schweitzer, the German Basketball Federation (DBB) plays the Dr. Albert Schweitzer Cup for youth national teams in Mannheim every second year in spring . The Albert Schweitzer Foundation for Our World (ASSfuM) also ties in with Schweitzer . It is a Germany-wide, non-profit animal welfare organization founded in 1999, whose patron was the philosopher Peter Sloterdijk until 2013. This organization is driven by the belief that the way we treat animals, especially when it comes to food production, is one of the greatest injustices in the world. The foundation advocates better keeping conditions for animals and counteracts overbreeding (so-called torture breeding).

The Protestant Youth took Albert Schweitzer as a model in many ways. The VCP tribes in Breitenbach , Lambsheim , Mosbach - Neckarelz and Remagen are named after him.

The Albert Schweitzer facility in Darmstadt is dedicated to him.

Churches and schools

In Tübingen there is an Albert Schweitzer Church , which also contains an Albert Schweitzer wall with pictures and texts.

The name Albert Schweitzer is also used to name numerous schools. The first German school with his name was the Albert-Schweitzer-Schule Nienburg grammar school in Nienburg / Weser , which was given the name in 1949 with the consent of Albert Schweitzer. In 2007, a list of schools that bear Albert Schweitzer's name lists a total of 118 German schools.

Albert Schweitzer Children's Villages

At the end of the Second World War, villages emerged in Switzerland, Austria and Germany to take in orphaned, abandoned children and young people. In 1957 in Waldenburg ( Baden-Wuerttemberg ), the establishment of the first Albert Schweitzer Children's Village by Margarete Gutöhrlein . Parents took over the care; Albert Schweitzer personally took over the sponsorship. Many Albert Schweitzer Children's Villages developed from the first children's village in Germany.

Film adaptations

Albert Schweitzer was also the subject of several feature films:

- In 1952 it is midnight, Dr. Schweitzer with Pierre Fresnay in the lead role.

- Albert Schweitzer , a film named after him about the life of Albert Schweitzer (with his original voice as the narrator) by Erica Anderson and Jerôme Hill receivedthe first Oscar for Best Documentary in 1958 . This film was released in 2013, restored and digitized on DVD, supplemented by the earliest film document from Lambaréné, the 1935 film from the Urwaldhospital by Dr. Albert Schweitzer in Lambarene .

- In 1965, the 44-minute documentary The Living Work of Albert Schweitzer was made again in collaboration between Schweitzer's daughter and Erica Anderson .

- In 1995 the critical feature film “Le Grand Blanc de Lambaréné” by director Emile Bassek Bah Kobbhio was made as a French-Cameroonian co-production.

- In 2009 Schweitzer was portrayed by Jeroen Krabbé in " Albert Schweitzer - A Life for Africa ".

Austrian Albert Schweitzer Society

The ÖASG was founded in 1984 and operates worldwide as a development aid organization and as a charitable organization in Austria. It only has volunteer workers and is recognized by the UN and UNESCO as an NGO.

International Albert Schweitzer Prize

Awarded for the first time on May 29, 2011 to Eugen Drewermann and the doctor couple Rolf and Raphaela Maibach in Königsfeld in the Black Forest , the location of the former home of Schweitzer, in which the Albert Schweitzer Museum can now be found.

Remembrance day

Albert Schweitzer's day of remembrance on September 4th is not included in the official Evangelical name calendar .

Awards

- Bernhard Nocht Medal

- 1928: Goethe Prize of the City of Frankfurt

- 1949: Honorary citizen of the city of Königsfeld in the Black Forest

- 1951: Peace Prize of the German Book Trade

- 1951: Johann Peter Hebel Prize

- 1952: Paracelsus Medal

- 1952: Nobel Peace Prize (awarded in October 1953 retrospectively for 1952; received on November 4, 1954 in Oslo)

- 1952: The Swedish Prince Carl Medal , awarded for meritorious humanitarian work

- 1952: Elected to the Académie des sciences morales et politiques to succeed Philippe Pétain

- 1954: Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- 1954: Pour le Mérite for Sciences and Arts

- 1955: Order of Merit

- 1955: Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- 1956: Knight , Military and Hospitaller Order of St. Lazarus of Jerusalem

- 1956: Corresponding member of the British Academy

- 1958: Honorary doctorate from the Westphalian Wilhelms University in Münster

- 1959: Honorary citizen of the city of Frankfurt am Main

- 1959: Sonning Prize from the University of Copenhagen

- 1964: Honorary doctorate from the Technical University of Braunschweig

Works

Collected Works

-

Collected works in five volumes . Edited by Rudolf Grabs. Beck, Munich 1974.

- Volume 1: From my life and thinking; From my childhood and youth; Between water and jungle; Letters from Lambarene 1924–1927.

- Volume 2: Decay and Reconstruction of Culture; Culture and ethics; The worldview of the Indian poets; Christianity and the world religions.

- Volume 3: History of the life of Jesus research.

- Volume 4: The Mysticism of the Apostle Paul; Kingdom of God and Christianity.

- Volume 5: From Africa; Cultural philosophy and ethics; Religion and theology; German and French organ building and organ art; Goethe. Four speeches; Ethics and Peace of Nations.

- The Albert Schweitzer Reader . Beck, Munich 1995.

Writings on theology

- History of Pauline Research from the Reformation to the Present . Olms, Hildesheim 2004. (Reprint of the edition by Mohr, Tübingen 1911)

- The mysticism of the apostle Paul . Mohr, Tübingen 1981. (Reprint of the 1st edition 1930)

-

History of the life of Jesus research . 6th photomechanically printed edition, Mohr, Tübingen 1951.

- History of the life of Jesus research. 9th edition. Mohr, Tübingen 1984.

- The Lord's Supper in the context of the history of Jesus and the history of early Christianity . Olms, Hildesheim 1983. (Reprint of the Tübingen 1901 edition)

- The Messiahship and Suffering: a sketch of the life of Jesus . 1983.

- Strasbourg sermons . Beck, Munich 1986.

- Christianity and the world religions . Beck, Munich 1923.

Writings on philosophy

- Reverence for life - basic texts from five decades . Beck, Munich 1991. (6th edition)

- Reverence for Animals - A Reader . Beck, Munich 2006 (1st edition)

- The worldview of the Indian thinkers: mysticism and ethics . Beck, Munich 1987.

- Kant's philosophy of religion . Olms, Hildesheim 1990 (first JCBMohr, Freiburg i. B., Leipzig, Tübingen 1899)

- Culture philosophy. Volume 1: Decay and Reconstruction of Culture; Volume 2. Culture and Ethics . Beck, Munich 1923.

- The problem of peace in today's world . Beck, Munich 1955.

Musicological writings

- German and French organ building and organ art . Facsimile reprint of the Leipzig 1906 edition and the afterword of the 2nd edition 1927, Breitkopf & Härtel, Wiesbaden, ISBN 978-3-7651-0230-1 .

- Johann Sebastian Bach. Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig 1908; Reprint Breitkopf and Härtel, Wiesbaden 1979, ISBN 3-7651-0034-X .

- For discussion about organ building . 1914; Edited by Erwin R. Jacobi. Merseburger Publishing House, Berlin 1977.

- The violin bow required for Bach's works for violin solo. In: Bach memorial, Zurich 1950.

Autobiographical writings

- From my childhood and youth . Beck, Munich 1991.

- Between water and jungle. Experiences and observations of a doctor in the primeval forest of Equatorial Africa. Paul Haupt, Bern 1921; from 1925 also C. H. Beck'sche Verlagbuchhandlung, Munich. The excerpt from the edition of 1926 Von Straßburg nach Lambarene has been published with a short biography in: Von Grönland bis Lambarene. Travel descriptions by Christian missionaries from three centuries. Edited by John Paul . Evangelische Verlagsanstalt Berlin 1952 (pages 182-192) = Kreuz-Verlag Stuttgart 1958 (pages 180-191).

- Messages from Lambarene. Munich 1928.

- From my life and thinking . Meiner Verlag, Leipzig 1931.

Correspondence

- Samuel Geiser (Ed.): Letters to Anna Joss. In: Albert Schweitzer in the Emmental. Four decades of collaboration between the jungle doctor von Lambarene and the teacher Anna Joss in Kröschenbrunnen. Zurich and Stuttgart 1974.

- Hans-Joachim Mähl (ed.): Renewal of religion under the sign of humanity. Unpublished letters from Albert Schweitzer to Kurt Leese. In: Journal for Modern History of Theology. Volume 4, 1997, pp. 82-113.

- Albert Schweitzer / Fritz Buri : Existential Philosophy and Christianity. Letters 1935–1964. Introduced, commented and ed. by Andreas Urs Sommer. Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46730-X .

- Herbert Spiegelberg (Ed.): The Correspondence between Bertrand Russell and Albert Schweitzer. In: International Studies in Philosophy. Volume 12, 1980.

estate

Most of Albert Schweitzer's estate is in the Zurich Central Library , initially as a deposit since the 1960s . With financial support from the Lottery Fund of the Canton of Zurich, the Central Library was able to definitely acquire the estate for one million francs in 2009. It comprises about twelve linear meters with materials, notes, speeches, manuscripts and other documents that are indexed and made available to the interested public. Only the correspondence is mostly in the Albert-Schweitzer-Zentrum Foundation in Günsbach, but the central library has numerous copies of it. It is a rare stroke of luck that almost all of the written legacy of a 20th century personality is kept in one place.

literature

Biographical

- Matthieu Arnold : Albert Schweitzer. His years in Alsace (1875-1913). Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, 2019, ISBN 978-3-374-06103-7 .

- James Bentley: Albert Schweitzer. A biography. Patmos, Düsseldorf 1993, ISBN 3-491-69031-5 .

- Tomaso Carnetto: Albert Schweitzer: Facts. An introduction to life and work. CD-ROM for Windows and Mac with text tape. Edition P12c, Leun / Lahn 2002, ISBN 3-933176-03-4 .

- Reinhard Griebner : The laughing lion. An Albert Schweitzer biography. Morio Verlag, Heidelberg 2014, ISBN 978-3-945424-02-5 .

- Sabine Hock : Schweitzer, Albert. In: Wolfgang Klötzer (Ed.): Frankfurter Biographie . Personal history lexicon . Second volume. M – Z (= publications of the Frankfurt Historical Commission . Volume XIX , no. 2 ). Waldemar Kramer, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-7829-0459-1 . P. 363 ff.

- Klaus Kienzler : Schweitzer, Albert. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 9, Bautz, Herzberg 1995, ISBN 3-88309-058-1 , Sp. 1195-1200.

- Peter Münster: Albert Schweitzer. Man - his life - his work. Neue Stadt Verlag, Munich / Vienna / Zurich 2010, ISBN 978-3-87996-878-7 .

- Nils Ole Oermann : Albert Schweitzer 1875-1965: A biography. CH Beck, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-59127-3 .

- Lothar Simmank: The doctor. How Albert Schweitzer alleviated hardship. Wichern, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-88981-238-4 .

- Harald Steffahn: Albert Schweitzer. With testimonials and photo documents. 14th edition. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2004, ISBN 3-499-50263-1 .

- Marie Woytt-Secretan (text): Albert Schweitzer builds Lambarene. (= The Blue Books ). Langewiesche publishing house, Königstein / Ts. 1957. (b / w photo documentation)

- Werner Zager: Schweitzer, Albert. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 24, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-428-11205-0 , pp. 55-57 ( digitized version ).

- Johann Zürcher: Schweitzer, Albert. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

Encounters with Schweitzer

- Hans Walther Bähr, Robert Minder (ed.): Meeting with Albert Schweitzer - reports and notes. CH Beck, Munich 1965.

- Siegwart-Horst Günther , Gerald Götting : What does reverence for life mean? Encounters with Albert Schweitzer. Verlag Neues Leben, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-355-01709-4 .

- Walter Munz: Albert Schweitzer in the memory of Africans and in my memory. Verlag Paul Haupt, Bern / Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-258-04529-1 .

- Jo and Walter Munz: Albert Schweitzers Lambarene 1913–2013. Contemporary witnesses report. For the 100th anniversary of the Urwald Hospital 1913–2013. Verlag Elfundzehn, Eglisau 2013, ISBN 978-3-905769-29-6 .

Thinking, religion, ethics, morality, responsibility

- Günter Altner u. a. (Ed.): Life in the midst of life. The topicality of the ethics of Albert Schweitzer. S. Hirzel, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-7776-1376-2 .

- Clemens Frey: Christian world responsibility in Albert Schweitzer with comparisons to Dietrich Bonhoeffer. (= Albert Schweitzer Studies. Volume 4). Bern 1993.

- Erich Gräßer : Albert Schweitzer as a theologian. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1979, ISBN 3-16-142351-8 .

- Stephan Graetzel , Joachim Heil (ed.): Albert Schweitzer's workshop in Lambarene. Texts on practical philosophy. Turnshare, London 2010.

- Claus Günzler : Albert Schweitzer. Introduction to his thinking. Beck, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-406-39249-0 .

- Claus Günzler, Erich Gräßer, Bodo Christ, Hans Heinrich Eggebrecht (eds.): Albert Schweitzer today. Focal points of his thinking . (= Contributions to Albert Schweitzer research. Volume 1). Tubingen 1990.

- Jackson Lee Ice: Schweitzer: Prophet of Radical Theology. Philadelphia 1971.

- Andreas Lienkamp : Respect and awe for life. From Albert Schweitzer on the Earth Charter. . In: Nature and Culture. Transdisciplinary journal for ecological sustainability. Volume 4, No. 1, 2003, pp. 55-72.

- Friedrich Schorlemmer : Albert Schweitzer. Genius of humanity. Construction Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-351-02712-4 .

- Hans Jürgen Schultz : I tried to love. Portraits. From people who thought peace and made peace: Martin Luther King , Dietrich Bonhoeffer , Reinhold Schneider , Albert Schweitzer. Quell, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-7918-2020-6 . (First edition: Partisans of Humanity. )

- George Seaver: Albert Schweitzer as a person and as a thinker. Deuerlichsche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Göttingen 1950. (From the English: A. S. - The man and his mind. A. & C. Black, London 1947)

- Andreas Urs Sommer : Schweitzer, Albert. In: Religion Past and Present . Fourth edition, Volume 7, Tübingen 2004, Sp. 1063-1064.

criticism

- André Audoynaud: Le docteur Schweitzer et son hôpital à Lambaréné. L'envers d'un mythe. L'Harmattan, Paris 2005, ISBN 2-7475-9499-8 .

- John Gunther : Africa from the inside. Humanitas Verlag, Konstanz / Stuttgart 1957.

- John Gunther: The old man and his weaknesses. In: Der Spiegel. No. 27, July 3, 1957, p. 42.

Others

- Werner Raupp , in: Sources encyclopedia on German literary history. Volume 29, 2001, pp. 44-105.

- Harald Schützeichel: The organ in the life and thought of Albert Schweitzer. Kleinblittersdorf 1991, ISBN 3-920670-27-2 .

- Heinz Vonhoff : Albert Schweitzer and his hospital in Lambarene. Young Community Publishing House, Stuttgart 1973.

Web links

- Works by and about Albert Schweitzer in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Albert Schweitzer in the German Digital Library

- Werner Zager: Schweitzer, Albert. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the 1952 award ceremony for Albert Schweitzer (English)

- German Albert Schweitzer Center

- Rainer Noll: Albert Schweitzer and the music (and other texts on Schweitzer)

- Albert Schweitzer's estate in the Zurich Central Library

- In the Albert Schweitzer Hospital in Lambarene August 2005 (PDF; 2.6 MB)

- Official website of the International Albert Schweitzer Association (AISL)

- La Fondation Internationale de l'Hôpital du Docteur Albert Schweitzer à Lambaréné

- Newspaper article about Albert Schweitzer in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Radio report by Corinna Mühlstedt: In the shadow of the jungle doctor: Helene Schweitzer. ( Memento from February 22, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Interview with Schweitzer's granddaughters Monique Egli and Christiane Engel , Deutschlandfunk, February 4, 2014

- Cover story about Schweitzer im Spiegel from December 21, 1960 (accessed September 2015)

Individual evidence

- ^ Fritz Eißfeldt: From the supporting reason. Albert Schweitzer as a theologian and philosopher. In: Paths to People. (Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht). 7th vol., No. 1, 1955, pp. 9-14.

- ^ The Nobel Peace Prize 1952: Albert Schweitzer.- Award Ceremony Speech, Gunnar Jahn, Chairman of the Nobel Committee

- ^ Acta Studentica. 60/1985, p. 9. (wilhelmitana.com)

- ^ Strasbourg sermons with excerpts and information on how they were created on Google books

- ↑ Helmut Siefert : Albert Schweitzer. In: Wolfgang U. Eckart , Christoph Gradmann (Hrsg.): Ärztelexikon. From antiquity to the 20th century. 1st edition. CH Beck, Munich 1995, p. 325; Medical glossary. From antiquity to the present. 2nd Edition. 2001, p. 284; 3rd edition. Springer Verlag, Heidelberg / Berlin / New York 2006, pp. 295–296. doi: 10.1007 / 978-3-540-29585-3 .

- ↑ Original title: Critique of the pathographies about Jesus published by the medical side. after Harald Steffahn: Albert Schweitzer. (= Rowohlt Biographies. 50263). Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1979. (16th edition, 2004, p. 145).

- ↑ Photo: Schweitzer and his employees in front of the Urwaldspital In: Süddeutsche Zeitung. January 16, 2008.

- ↑ Here is an excerpt from the book "Between Water and Primeval Forest" by Albert Schweitzer from the book: Johannes Paul : Von Grönland bis Lambarene. Travel descriptions by Christian missionaries from three centuries. (pdf). Evangelische Verlags-Anstalt, Berlin 1951.

- ↑ Albert Schweitzer: Myth of the 20th Century. Cover story. In: Der Spiegel. No. 52, December 21, 1960. (Accessed Sept. 2015, Goebbels search function)

- ↑ Chinua Achebe: An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's Heart of Darkness. In: The Massachusetts Review. 1977.

- ^ John Gunther: Inside Africa. Harper, New York 1955.

- ^ Mark W. Harris: The A to Z of Unitarian Universalism . Scarecrow Press, Lanham, MD, United States 2009, ISBN 978-0-8108-6817-5 , pp. 114 .

- ^ Website of the Albert Schweitzer Foundation for Our Environment , accessed on March 2, 2014.

- ↑ General on Albert Schweitzer as theologian: Wolfgang Müller (Ed.): Between thinking and mysticism - Albert Schweitzer and theology today. Syndicate Book Society for Science and Literature, Meisenheim 1997; Ulrich Luz : Albert Schweitzer as a theologian. Lecture at the Seniors Academy Berlingen , Switzerland, 2013; Werner Zager: Schweitzer, Albert . In: German Bible Society (Hrsg.): The scientific Bible lexicon on the Internet . (WiBiLex), Stuttgart. (Entry created in February 2009).

- ↑ Johannes Weiß: The preaching of Jesus about the kingdom of God. Goettingen 1892.

- ↑ Consistent eschatology. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ↑ Albert Schweitzer: The history of the life of Jesus research (1913) . In: Wilfried Härle (Hrsg.): Basic texts of the newer Protestant theology . 2nd Edition. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2012, p. 97-100 .

- ↑ On Paul cf. the foreword by Werner Kümmel to Schweitzer's “The Mysticism of the Apostle Paul”, Mohr Verlag, Tübingen.

- ↑ Erwin R. Jacobi : Albert Schweitzer and the music. (= Annual edition of the International Bach Society ). Breitkopf & Härtel, Wiesbaden 1975, ISBN 3-7651121-4 .

- ↑ Albert Schweitzer: From my life and thinking. Stuttgart library, undated (approx. 1960), p. 80.

- ↑ an indication such as "V / P 105" means: V = the organ has 5 manuals, P = it has an (independent) pedal, 105 = it has 105 stops.

- ^ Arte Nova classics

- ↑ Rudolf Gähler: The round arch for the violin - a phantom? ConBrio, Regensburg, 1997, ISBN 3-930079-58-5 .

- ^ Philippe Borer: The Twenty-Four Caprices of Niccolò Paganini. Their significance for the history of violin playing and the music of the Romantic era. Foundation Central Office of the Student Union of the University of Zurich, Zurich 1997.

- ↑ bach-bogen.de ( Memento from August 8, 2018 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ http://www.cello.org/Newsletter/Articles/bachbogen/bachbogen.htm Presentation of the BACH.Bogen in Paris (2001)

- ↑ Albert Schweitzer: From my life and thinking. Stuttgart library, undated (approx. 1960), p. 66.

- ↑ Schweitzer in From my life and thinking , Stuttgarter Hausbücherei, undated (approx. 1960), p. 67: “Bach is always played too fast. Music that presupposes a visual perception of accompanying tone lines becomes chaos for the listener, for whom a too fast tempo makes this impossible. "

- ↑ Albert Schweitzer in Chapter XIV - The rendering of the organ works of his book Johann Sebastian Bach , Breitkopf & Härtel , Leipzig 1952, p. 271: “You take the tempos, the longer and the more you play Bach's organ works, the slower. [...] The lines must be in calm plastic in front of the listener. He must also have time to imagine them in one another and one after the other. "

- ↑ Albert Schweitzer: From my life and thinking. Stuttgarter Hausbücherei, no date (approx. 1960), p. 131: As the reason for slower tempos, Schweitzer refers to the construction-related limits of the maximum possible playing speed of the organs in Bach's time and to Adolf Friedrich Hesse , who, according to Bach tradition, used Bach's organ works at a "very calm pace".

- ↑ Albert Schweitzer in Chapter XIV - The rendering of the organ works of his book Johann Sebastian Bach , Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig 1952, p. 271: “If so many organists think they are playing Bach 'interestingly' by rushing, this is because that they do not have the right plastic of the game that allows them to bring their presentation to life for the teacher by clearly working out the details. "

- ↑ Albert Schweitzer: From my life and thinking. Stuttgart library, undated (approx. 1960), p. 67.

- ↑ Albert Schweitzer in Chapter XIV - The rendering of the organ works of his book Johann Sebastian Bach , Breitkopf & Härtel , Leipzig 1952, p. 271.

- ↑ Ilse Kleberger: Albert Schweitzer - The symbol and man. Erika Klopp Verlag, Berlin / Munich 1989, p. 18.

- ↑ Benedictus Winnubst: Albert Schweitzer's peace thinking - his answer to the threat to life, especially human life, from the core armor. Editions Rodopi, 1974, p. 73.

- ^ German Albert Schweitzer Center ( Memento from April 11, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Siegwart-Horst Günther, Gerald Götting: What does reverence for life mean? 2005, p. 25.

- ↑ Almut Hoffmann: Albert Schweitzer's Thoughts on Peace in the Period from 1945 to 1978 . Hall 1988.

- ↑ Gerald Götting: Visiting Lambarene. Encounters with Albert Schweitzer . Berlin 1964.

- ↑ Heuss' letters to Schweitzer of August 24 and August 28, Albert Schweitzer Archive Gunsbach (ASAG), and October 12, 1961, Theodor Heuss: Privatier und Elder Statesman. Letters 1959–1963 . Berlin / Boston 2014, p. 341f.

- ^ Siegwart Horst Günther, Gerald Götting: What does reverence for life mean? 2005, p. 44.

- ^ Nils Ole Oermann: Albert Schweitzer 1875-1965: A biography. CH Beck, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-59127-3 , p. 307.

- ^ Sebastian Moll: Albert Schweitzer. Master of self-presentation. Berlin University Press, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-86280-072-8 .

- ^ Information on Walter Munz in the German Digital Library , accessed on December 25, 2015.

- ↑ Walter Munz: Albert Schweitzer in the memory of Africans and in my memory . Verlag Paul Haupt, Bern / Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-258-04529-1 .

- ^ La Fondation Internationale de l'Hôpital du Docteur Albert Schweitzer à Lambaréné

- ↑ Daniel Neuhoff: Lambarene: Commemoration for the 50th anniversary of Albert Schweitzer's death on September 4, 2015, followed by a meeting of the Board of Trustees. ( Memento from December 25, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) In: German Aid Association for the Albert Schweitzer Hospital in Lambarene, December 2015 edition (PDF file, p. 2).

- ↑ Website Albert Schweitzer Foundation for Our Environment , accessed on June 5, 2011.

- ^ VCP, Albert Schweitzer tribe, Remagen

- ↑ List of schools that bear the name of Albert Schweitzer ( memento of October 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) see also: Albert Schweitzer School

- ↑ absolutmedien.de. Retrieved August 28, 2017 .

- ↑ Information at the IMDb, accessed on June 23, 2011

- ↑ Königsfeld celebrates “Schweitzer heirs” Südkurier, May 30, 2011.

- ↑ Albert Schweitzer in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints

- ↑ Peace Prize of the German Book Trade 1951 for Albert Schweitzer laudation and acceptance speech (PDF)

- ^ Honorary Members: Albert Schweitzer. American Academy of Arts and Letters, accessed March 22, 2019 .

- ^ Website of the Order of Lazarus - Obedience Orleans

- ^ Fellows: Albert Schweitzer. British Academy, accessed July 29, 2020 .

- ↑ Zurich buys Albert Schweitzer's estate swissinfo.ch, February 12, 2009.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Schweitzer, Albert |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Alsatian doctor, theologian, musician and philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 14, 1875 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Kaysersberg in Upper Rhine (German Empire) |

| DATE OF DEATH | 4th September 1965 |

| Place of death | Lambaréné , Gabon |