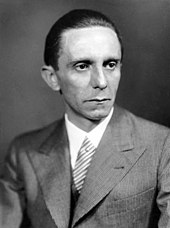

Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (born October 29, 1897 in Rheydt ; died May 1, 1945 in Berlin ) was one of the most influential politicians during the time of National Socialism and one of Adolf Hitler's closest confidants . As Gauleiter of Berlin from 1926 and as Reich Propaganda Leader from 1930, he played a major role in the rise of the NSDAP in the final phase of the Weimar Republic . As Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda and President of the Reich Chamber of Culture , Goebbels held two key positions in Germany from 1933 to 1945 for the management of the press, radio and film as well as other cultural activities.

By combining demagogic rhetoric , systematically choreographed mass events and the effective use of modern technology for propaganda purposes , in particular the use of film and radio , Joseph Goebbels succeeded in indoctrinating large parts of the German people for National Socialism and defaming Jews and communists . During the Second World War , Goebbels himself was responsible for the newsreel , which was a central medium of domestic propaganda . He also published numerous leading articles in leading newspapers, which were also read on the radio. His notorious Sports Palace speech of February 1943, in which he called on the population to " total war ", is an example of the manipulation of the population. Through anti-Semitic propaganda and actions such as the November pogroms of 1938 , he ideologically prepared the deportation and subsequent extermination of Jews and other minorities, making him one of the decisive pioneers of the Holocaust .

The extensive diaries that Goebbels kept from 1924 until his suicide are considered an important source for the history of the NSDAP and the time of National Socialism .

Early years

Origin and childhood

Goebbels came as the third son of Friedrich (Fritz) Goebbels (1867–1929) and his wife Maria Katharina geb. Odenhausen (1869–1953) in the Rhine Province to the world. He grew up with his siblings Konrad (1893–1949), Hans (1895–1947), Elisabeth (1901–1915) and Maria Katharina (1910–1949, married to the screenwriter and film director Max W. Kimmich and later heiress of Goebbels) a Catholic home. His father began as an errand boy and rose to the position of authorized signatory of the Vereinigte wickfabriken GmbH , which employed around 50 people. His mother, a half-orphan with five siblings, was born in Waubach in the Netherlands . Before she got married, she worked as a maid on a farm. She died on August 8, 1953 in Rheydt. Goebbels' childhood was marked by the financially strained situation of his family. In order to increase their income, the family did various homework.

At the age of four, Joseph Goebbels fell ill with inflammation of the bone marrow , which atrophied his right lower leg and developed a clubfoot . At about 165 centimeters he reached a relatively small height, which is why he was later openly caricatured in popular parlance and abroad and mocked as Schrumpfgermane and "Humpelstiltskin". In retrospect, Goebbels interpreted the illness as a "drawing" by force majeure and tried to compensate for it throughout his life. The handicap and his background, which he found unsuitable in the school environment, spurred his ambition. He attended the municipal high school with reform high school (today Hugo-Junkers-Gymnasium ) and was a student of the Augustinerseminar in Kerkrade . He was best in Latin, geography, German and mathematics. He was proud of the old piano his father had given him. He developed a special talent for acting. When he graduated from high school in March 1917, his performance in almost all subjects was graded “very good”. For the best German essay, he was allowed to give the farewell and acceptance speech at the dismissal ceremony; the speech was marked by his enthusiasm for war ( First World War ).

Studying and looking for a job

Goebbels wanted to take part in the war as a soldier after graduating from high school, but was classified as permanently unsuitable for military service due to his disability. To the disappointment of his parents, Goebbels did not want to study Catholic theology despite his earlier intentions . He chose German studies and history. From 1917 to 1921 he studied at the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn , the Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg , the Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg (1918/19), the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich and the Ruprecht-Karls- Heidelberg University .

Goebbels received a student loan from the Albertus Magnus Association, which promoted Catholic students. The repayment could only be enforced by a court in 1930. On the recommendation of his former religion teacher Kaplan Mollen, Goebbels became a member of the Unitas Sigfridia in Bonn on May 22, 1917, in the Union of Scientific Catholic Student Associations . His petty-bourgeois origins played no role there. In June 1917 Goebbels was drafted into the military auxiliary service. In 1918 he followed his friend and roommate Karl-Heinz Kölsch to Freiburg.

In Freiburg he met the law student Anka Stalherm from a wealthy family. Goebbels fell out of jealousy with Kölsch and his sister, with whom he had entered into a relationship before moving from Bonn. A passionate love affair developed between Goebbels and Stalherm, but repeatedly shaken by serious crises. Her parents rejected the destitute Goebbels. In September 1918 Goebbels moved to Würzburg with Stalherm .

With the end of the First World War, he experienced a crisis that led to an increasing ideological disorientation. Goebbels began to break away from Catholicism and resigned from the Unitas Association, in whose clubs he had been active in Bonn, Freiburg and Würzburg. He turned to Fyodor Dostoyevsky's ideas of God and, under the influence of Oswald Spengler, came to atheism. He was faced with a bewildering array of ideas, none of which seemed to offer a way out of the "chaos of time." He lacked a clear, uniform worldview in which he could have found "peace and fulfillment". Nor did he see the “strong genius” who would have pointed to “new goals”. However, during the Kapp Putsch , he was able to get excited about a “red revolution in the Ruhr area” .

Goebbels and Stalherm spent the summer semester of 1919 in Freiburg, and in the winter semester they moved to Munich. Goebbels' attempt to publish a drama failed because of the costs involved. In 1920 the connection to Stalherm was broken, which filled Goebbels with thoughts of death. Shortly after his doctorate , the teacher Else Janke, the daughter of a Jewish mother and a Christian father, became his new girlfriend. Goebbels would have married her if she hadn't been “half-blood” in his anti-Semitic view. At the end of 1926 he ended the connection when he became Gauleiter of Berlin.

Goebbels originally wanted to write a dissertation with the Jewish literary scholar Friedrich Gundolf , whom he admired ; however, he referred him to the also Jewish Max Freiherr von Waldberg . On April 21, 1922, he was awarded a doctorate in Heidelberg with the overall grade rite superato (about a good sufficient). phil. PhD. The topic of his dissertation was: “ Wilhelm von Schütz as a dramatist. A Contribution to the History of the Drama of the Romantic School ”. All his life he used the doctoral degree for signatures (Dr. Goebbels or as a paraphe : Dr. G.) and was addressed with the academic degree.

Despite his newly acquired doctorate, Goebbels saw himself in an outsider position.

His literary attempts were ignored by publishers and newspapers. Even as a journalist, he was unable to gain a foothold despite successful first steps. At the beginning of 1923, Goebbels, against his convictions, accepted a position at the Dresdner Bank in Cologne, which Else Janke had made . For him this was a “temple of materialism”, which is why he stopped this hated activity after a few months and was unemployed again.

Ascent

Turning to National Socialism

Goebbels found his first political home when he traveled to Weimar in August 1924 to attend the founding congress of the National Socialist Freedom Movement in Greater Germany , in which the various successor organizations of the banned NSDAP came together. The party chairman Erich Ludendorff gave him "the last firm belief". Here he met his future mentor Gregor Strasser . Immediately afterwards Goebbels became one of the founders of a local Gladbach group of this party and began his career as a speaker and journalist. In October 1924 he became editor of her Elberfeld Gaukampfblatt Völkische Freiheit .

When Hitler re-founded the NSDAP in the spring of 1925, Goebbels immediately joined it. Gregor Strasser reorganized the party in northwest Germany. In March 1925 Goebbels was managing director of the Gau Rhineland-North. He moved to Elberfeld (now part of Wuppertal ) and developed into the party's leading agitator , not only in the Rhineland and Westphalia: in one year he appeared 189 times as a speaker. He participated in an intrigue that forced his superior, Gauleiter Axel Ripke , to resign in August 1925. In the same month he became editor of the National Socialist letters published by Gregor Strasser . Now he also received a monthly salary of 150 marks.

Encounter with Hitler

At that time, Goebbels' attitude to Hitler was ambivalent. Although he celebrated it in articles and was enthusiastic about Mein Kampf , he nevertheless noticed some ideological differences, especially with regard to socialism . When they met in Braunschweig on November 6, 1925, he was fascinated by Hitler. “This man has everything to be king. The born tribune of the people. The coming dictator. ”Shortly afterwards, on November 22nd, 1925, Gregor Strasser founded a“ Northwest Working Group ”- with Hitler's approval. Goebbels was in charge of developing a program. It differed significantly from Hitler's ideas.

In order to bring Strasser and Goebbels to his line, Hitler called a "Führer Conference" in Bamberg on February 14, 1926. Hitler's speech was a great disappointment for Goebbels: He was shocked that Hitler wanted to set up a huge German settlement area in "Holy Russia", which he revered . The fact that the German princes should not be expropriated without compensation ran counter to his socialist convictions. Without having expressed any objection, he retreated dejectedly: “Probably one of the greatest disappointments of my life. I no longer completely believe in Hitler. That's the terrible thing: I've lost my inner support. I'm only halfway. "

Hitler carefully planned how he could get Goebbels to his side. In April 1926 he invited him as well as Karl Kaufmann and Franz Pfeffer von Salomon , the other two directors of the "Gaus Ruhr", to Munich . Hitler was "shamefully good" and was able to disarm Goebbels. The following day, a discussion about the program was no longer necessary, Goebbels was convinced from the start: “He answers brilliantly. I love him. Social question. Completely new insights. He thought everything through. [...] I bow to the greater, the political genius . ”Despite his“ conversion ”, Goebbels reluctantly and imperfectly gave up his earlier convictions - the ideological adjustment became a changeful process.

Ideological development

Sacrifice and redemption

Thoughts of sacrifice and death were not alien to the young Goebbels. They were reflected in his novel Michael Voormann: A Human Fate in Diary Pages . The hero Michael Voormann is a synopsis of an injured friend with an ideal image of the author. Voormann goes from soldier to student to miner. The other miners initially reject him until there is a fraternization in which Voormann finds his "redemption". But then he becomes a “victim” in a mine accident, and with this he also redeems the others. So this is about the motive of the redeeming self-sacrifice. The echoes of Goebbels' Catholic past are obvious.

In his writings of 1925, these ideas were expanded in various and contradicting ways. Goebbels demanded a profound change and a willingness to sacrifice from his followers. This sacrifice should then break the power of capitalism and thus also of Judaism. This would end the class struggle and open the way to a future ideal Germany for which he adopted the term “ Third Reich ”, rich in references .

"Holy Russia"

Goebbels was filled with an enthusiastic love for Russia. He considered the Bolshevik system to be only temporary. But then Russia would lead the way on the way to ideal socialism. This would also create a new, “coming” human being. This event should take place in close interaction with Germany, possibly also in a military conflict. But the fight should not be for land or power, but “for the ultimate form of existence”.

After the confrontation with Hitler, this hitherto frequent topic disappeared from his articles and from his diary. As Gauleiter, Goebbels took over Hitler's line temporarily. But as early as 1929 he wanted to see Germany's expansion in overseas colonies , not in Russia. As Propaganda Minister he succeeded Hitler again, but before the start of the German-Soviet War in 1941 he again expected “real socialism” there, and in the last years of the war he constantly pushed for a more humane occupation policy.

socialism

The young Goebbels saw himself as a socialist . He glorified the worker and wanted to feel inwardly connected to him. His disgust was with the “ bourgeois ”: this was not only the capitalist, but also the petty bourgeois . On Communists he liked her revolutionary fervor and hatred of the bourgeoisie . Social democracy and liberalism were their mutual opponents. The international orientation of communism was dividing for him, while he himself intended to establish a " national socialism ". When he became Gauleiter in Berlin in 1926, however, he saw bitter opponents in the Communists.

As recently as 1925, Goebbels wanted to distribute property widely, to give it into the hands of those "who create it with brain and hand". What convinced Hitler in April 1926 was something else:

“Mixed collectivism and individualism . Soil, what on top and under the people. Production, there creating, individualistic. Corporations, trusts, finished production, transport etc. socialized. One can talk about it. He thought it all through. "

But this did not remain his position, in 1929 he wanted to see private property preserved, at best make an exception for land speculation and department stores . And when, as Minister of Propaganda, he dominated radio, press and film, he saw in it “true socialism” - he no longer thought of a diversification of property.

anti-Semitism

Goebbels' relationship with Jews was contradictory in his early years. He was impressed by Jewish people, according to the Heidelberg German studies specialist Friedrich Gundolf . For several years he held on to his “ half-Jewish ” girlfriend Else Janke. Unlike Hitler's, his anti-Semitism was not predominantly racially determined. He saw a “good mix of races” as one of the advantages of the busy Rhinelander. On a trip to Sweden he found the local "blonde breed" to be contemptible; "Germans on the outside, half-Jews on the inside". Rather, the sources of his anti-Semitism were nationalist and anti-capitalist . The Jews, as “foreign elements”, are not of a nationalistic disposition and will hand Germany over to hostile, supranational powers. But above all, they are connected with money. “Money is the power of evil and the Jew is its satellite.” But he also hated the non-Jewish representatives of the national right.

Socialism and anti-Semitism were closely related in Goebbels' ideas. So he wrote in October 1925:

“It's not really about two special classes . In reality, a hundred slaveholders are tyrannizing a population of 60 million [...] The hundred are looking for their allies in the bourgeois camp, above and below, because for the time being they feel too weak to fight the fight alone. "

By the slave owners, Goebbels meant the Jews, who, however, found their non-Jewish allies in the bourgeois camp. The class struggle would not be won with the elimination of the Jews alone.

Which fate Goebbels intended for the Jews during his time in Elberfeld remains unclear. His threats ranged from toleration in a guest role that could be canceled at any time, to exclusion from public life, to “root out, cut out, ruthless fight”. But there are also other words:

“Oh God, a communist, a rascal, a patrioteless journeyman , a traitor, a deceiver - a Jew! Beat him to death! Point! Is that really enough? [...] The crux of the matter is the social question of how we, workers and citizens, can live side by side in the future. "

Gauleiter in Berlin

Organization of the Gaus

On November 9, 1926, Hitler appointed Goebbels Gauleiter of Berlin-Brandenburg . The Berlin NSDAP was disorganized, its supporters quarreled and the influence in the city was low. Goebbels was able to prevail quickly. He used his special powers, let adversaries and the undecided or excluded them from the party. With 200 convinced and docile supporters, he founded a “National Socialist Freedom League” within the party, the members of which were willing to undertake “special tasks” and make financial sacrifices. In Berlin, Goebbels created a tight district organization: the city was divided into sections, the leaders of which he appointed himself. As of July 1, 1928, these were further subdivided into “street cells”; a “cell chairman” was supposed to look after a maximum of 50 party members. In 1930 he set up " Gau operating cells " to penetrate the factories - it was taken over by the communists. In 1931 this became the model for the other districts. The number of members of the Berlin NSDAP grew rapidly. In 1927 the modest party headquarters at Potsdamer Strasse 100 was given up. First four rooms in Lützowstrasse 44 took their place, then in 1928 a generously furnished floor at Hedemannstrasse 10 with 25 rooms.

He was able to get the head of the Berlin SA, Kurt Daluege , behind him and make him his deputy. He encouraged him to rapidly expand the SA, which at the time was disguised as a "sports department" because of a ban. With this he created a willing instrument for hall and street battles, which was mostly used against the initially far superior communist " Red Front Fighter League ".

However, he did not succeed in asserting himself outside the city limits in the same way, especially since the SA in Brandenburg refused to submit to him. Therefore, a separate Gau “Brandenburg” was formed in 1929, while Goebbels remained the Gau “Greater Berlin”.

In 1930 and 1931 the East German SA rebelled against the NSDAP under Walther Stennes . Both times Goebbels had to call Hitler for help to bring the SA back to subordination.

Fight against democracy

At first, Goebbels wanted to bring the little-noticed NSDAP into the headlines. Every legal and illegal means was right for him to do this: marches, widely placarded meetings, hall and street battles and riots against Jews. He also used the trials he repeatedly provoked for propaganda.

Street and hall battles

Goebbels had already written in June 1926: “The power state begins on the street. If you can conquer the street, you can also conquer the state. ”Here he wanted to use“ terror and brutality ”and thus“ overthrow the state [...]. ”This program became a bloody reality in Berlin. The communists, previously viewed with sympathy, now became his bitterly opposed opponents.

For February 11, 1927, Goebbels scheduled an event in the “red” working-class district of Wedding - a deliberate provocation. The announcements, huge, bright red posters, imitated those of the communists. The expected battle in the hall began even before Goebbels' speech; the police had to protect the communists. Goebbels celebrated the injured SA men who were lined up on the stage as “victims of communist terror”. When he spoke of the "unknown SA man", he became a victim for a higher cause, such as the soldier in war. The bourgeois press brought up the incident in a big way - the Nazi movement was now noticed. The party gained 400 new members in March; now there are 3,000. Goebbels had presented himself as a brilliant propagandist, as courageous and fearless. With this he had consolidated his position as Gauleiter.

At an event on May 4, 1927, a pastor who Goebbels opposed was beaten to hospital by SA men. The police president of Berlin then banned the NSDAP in Berlin with all its sub-organizations. That was undermined with front organizations. However, income was lost and there were signs of disintegration. The ban on speaking, which was also pronounced, was also unpleasant for Goebbels. In a "school for politics" he founded, he was at least able to avoid it in front of his followers. However, outside of Berlin he was able to perform unchanged. The ban on speaking fell in October 1927, the party ban in March 1928 because of the upcoming Reichstag elections.

Since the Bloody May 1929, clashes between communists and the SA, fueled by propaganda on both sides, became more frequent. Goebbels called his opponents “roaring, raging subhumans”, “poison-spitting animals” that had to be “eradicated” and “destroyed”. He was shot at in a street fight in September 1929, but the bullet hit his driver.

In December 1930, the American film Nothing New in the West, based on the novel Erich Maria Remarques, was released in cinemas. He was fiercely attacked by the right for showing the futility and horror of war. Goebbels had 150 followers blow up the demonstration. These rioted, slapped actual or supposed Jews, threw stink bombs and released white mice. The police cleared the hall. On the following days, he organized protest demonstrations that turned into street battles with the police. The film was finally banned because of "endangering the German reputation". Goebbels saw this as his great success.

Hostility towards Jews

Shortly before Goebbels went to Berlin in October 1926, he did not want to be a "Radau Anti-Semite". As a Gauleiter, however, he was exactly that. For him, the Jews were enemies of the people and bacilli, because they abused their “right of hospitality”, exploited the German people with fraud and corruption, but above all they embodied capitalism and the hated Weimar Republic for him. The only thing left for the German people is self-defense against the madness of gold. He also saw the destructive influence of the Jews in culture, but was still enthusiastic about individual Jewish personalities such as the actress Elisabeth Bergner . A rabid and popular anti-Semitism became an effective propaganda weapon for him. So he used open or latent anti-Semitic currents in the population. Above all, he offered simple explanations for complex issues.

The constant target of Goebbels' accusations was the Jewish Vice President of the Berlin Police, Bernhard Weiss . Since the party ban initiated by the political police headed by Weiss, Goebbels nicknamed him "Isidor" and mocked him in speeches and articles. The cartoons in his weekly newspaper The Attack were particularly effective . In Goebbels' propaganda, Weiß became a representative of the Weimar Republic, which he was able to portray as oppressive and ruled by Jews.

As early as March 20, 1927, Goebbels had his SA men beat up Jews. There were far more serious riots on the evening of the Jewish New Year celebrations , on September 12, 1931, when groups of uniformed youths beat passers-by on the Kurfürstendamm with Jewish appearance. The Kurfürstendamm riot of 1931 was conducted by the leader of the Berlin SA, Wolf-Heinrich Graf von Helldorff . 27 rioters were sentenced to prison terms, Helldorff got away with a fine, Goebbels could not prove incitement.

Processes

His actions and insults earned Goebbels numerous lawsuits. In February 1928 he had to answer for the pastor who had been beaten up in May of the previous year. He was initially sentenced to six weeks in prison. In the second instance this was reduced to a fine of RM 600, but he refused to pay. In April 1928 he was sentenced to three weeks in prison for insulting Weiss. He was able to evade the punishment because he had been a member of the Reichstag since the Reichstag election in 1928 and thus enjoyed political immunity .

In December 1929, he accused Reich President Paul von Hindenburg of treason against the German people. For this he had to answer in court in May 1930. He kept up his allegations to an ovation from the audience. He was only sentenced to a fine of RM 800. Before the appeal proceedings on August 14, 1930, Hindenburg stated that Goebbels did not want to insult him personally and that he was no longer interested in punishment. Two days earlier Goebbels had stood before the court in Hanover for alleging that the Prussian Prime Minister Otto Braun had been bribed by a " Galician Jew". Goebbels staged his appearance: with a parade of National Socialists he was accompanied to the court. He declared that he did not mean Braun but the former Chancellor Gustav Bauer and was acquitted.

On September 29, 1930, Goebbels was to be tried on six charges of libel. He applied for postponements several times, for various reasons. Finally, the court ordered the foreclosure. Goebbels went into hiding. On the day the Reichstag opened, he had himself taken to the Reichstag building and narrowly escaped arrest. With that he was again under the protection of immunity.

Since the waiver of immunity was facilitated in February 1931, the number of trials has increased. On April 14, he was fined RM 1,500 for insulting white. He was arrested in Munich and forcibly brought before Goebbels on April 29, because he had not appeared in the proceedings that the criminal investigator Otto Busdorf, known from the Magdeburg judicial scandal, had brought against Goebbels for defamation. He was fined a total of RM 1,500 in eight different cases; on May 1 another RM 1,000, in mid-May another RM 500 and two months in prison were added. Goebbels took refuge in installment payments, eventually he was waived large amounts due to an amnesty. He also did not have to serve the prison sentence. He slaughtered the trials for propaganda purposes: he portrayed the justice system of the Weimar Republic as impotent, ridiculous or oppressive, and he stylized himself as a martyr .

Member of the Reichstag

In the Reichstag elections on May 20, 1928, Goebbels entered the Reichstag as one of 12 members of the NSDAP. In the attack he mocked this institution, which he found "long ripe for doom":

“We have nothing to do with Parliament. We reject it internally and do not stand in line to give it vigorous expression on the outside. [...] I am not a member of the Reichstag. I am an idi. An IdF. One holder of immunity, one holder of the free ticket. (An IdI) insults the 'system' and receives thanks from the republic in the form of seven hundred and fifty marks a month's salary. "

Goebbels introduced himself on July 10th with a diatribe. He received a reprimand from the Reichstag vice-president and the desired press coverage. Otherwise he paid little attention to Parliament, and only after almost nine months did he speak again.

The attack

Since July 1927, Goebbels published the weekly newspaper The Attack , which served him as a mouthpiece and an illegal district headquarters during the party ban. In addition, this "Kampfblatt" offered a welcome forum for himself: Every week he wrote an editorial and a "Political Diary" in which he commented on the events of the past week. The style of the paper was simple, folk and stirring. Caricatures by the draftsman Hans Herbert Schweitzer with the pseudonym Mjölnir served as eye-catchers. They glorified the fighters of the SA and ridiculed their political opponents.

At first the new paper had a difficult time. There was already the party's daily newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter , which appeared in Munich , as well as the official Gaublatt, the National Socialist weekly Berliner Arbeiterzeitung published by the brothers Otto and Gregor Strasser . Goebbels took offensive action against them, no longer providing them with Gaus communications and did not shy away from assaulting the distributors. However, the financial situation remained tense. In October 1927 only 4,500 copies were sold.

He was worried about the plans of the Strasser brothers to publish a daily newspaper in Berlin - he had exactly the same intention with the attack . But for this he needed Hitler's financial support, whose leadership qualities he began to doubt. In January 1930 he noted: “As usual, Hitler will not make a decision. It sucks with him. [...] Hitler himself does not work enough. This can not go on like this. And does not have the courage to make decisions. He no longer leads. ”When Goebbels was with Hitler in Munich at the end of January 1930, Hitler tried very hard for him and even promised him the Nazi propaganda leadership . Goebbels drove back comforted. When the Strasser brothers' newspaper actually came out in March 1930, Goebbels was full of resentment: “Hitler broke his word four times in this matter alone. I don't believe him anymore. [...] How will that be when he has to play the dictator in Germany? "

Goebbels remained active as a district leader and as a speaker at mass events. On April 27, 1930, Hitler appointed Goebbels as Reich Propaganda Leader. Now Goebbels' displeasure was gone. Again he was under Hitler's spell. This crisis was only reflected in the diary. Goebbels carefully hid them from the outside: With unchanged energy he acted as Gauleiter, wrote leading articles and appeared as a speaker. This was not the last time that Goebbels perceived his relationship with Hitler as crisis-ridden.

From October 1929 onwards, The Attack could appear twice a week, and finally it appeared as a daily evening paper from November 1, 1930. In March 1930 the circulation reached 80,000, the high point was reached in July 1932 with 110,000 copies. That was the second place among the Nazi papers after the Völkischer Beobachter . Nevertheless, there were always money problems. The newspaper's frequent bans also contributed to this - 13 times between November 1930 and August 1932 alone; the sheet failed for a total of 19 weeks.

In 1932 Goebbels was chairman of the Reich Association of German Radio Participants. V. (R. D. R.) and published in its magazine Der Deutsche Sender . On November 2, 1932, in the newspaper, he called the radio a “revolutionary weapon of the new time”, which “accompanies and guides our national comrades from morning to night [...]”.

Horst Wessel

Goebbels turned the National Socialists killed by political opponents into martyrs. SA leader Horst Wessel, who was fatally injured by a member of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) in an attack on his apartment on January 14, 1930 and died on February 23, 1930, was particularly suitable for this . Goebbels was able to find his novel hero Michael Voormann in him: What both of them had in common was the path from soldier to student to worker and early death. Goebbels designed his public speeches in this way. In his obituary he declared Wessel to be immortal: “[...] his spirit rose in us to continue to live with us all. He believed it himself and knew it; he gave it sufficient expression: he 'marches in our ranks!' "A week later Goebbels stylized him as a figure of Christ and the embodiment of Germany:" He drank the cup of pain to the point. [...] Germany fought and suffered, tolerated and died and then, reviled and spat on, died a grave death. Another Germany stands up. A young one, a new one! […] Forward over the graves! In the end lies Germany! ”- This combination of sacrifice and resurrection became the model for National Socialist funeral ceremonies, for example when on November 8th and 9th, 1935 the coffins of the dead of the Hitler coup were transferred to a“ temple of honor ”in Munich.

Propaganda leaders and election campaigns

As the Reich Propaganda Leader , Goebbels was responsible for the party's propaganda, election campaigns and major events from April 27, 1930, but not for its press. The radio was added in August 1932, the film temporarily from July 1931. - Gau propaganda lines were set up in the Gau. Numerous writings of the Reich Propaganda Leadership were supposed to standardize the party propaganda.

The most important task in the new office was the election campaigns. The 1930 Reichstag election was scheduled for September 14th . Goebbels' slogan was “work and bread” - due to the economic crisis, there was mass unemployment. The topic of the election campaign should be the Young Plan , i.e. the settlement of reparations . Carrying out this was described as a policy of compliance , denigrating the Republican parties as assistants of the former opponents of the war. The campaign should run "at a breathtaking pace". He did not spare himself. The highlight was Hitler's speech on September 14th at the Berlin Sports Palace . The election success was overwhelming: with 107 members, the NSDAP became the second largest parliamentary group after the SPD. The communists had also won, the center and the Bavarian party held their own, the other bourgeois parties lost heavily.

After much pressure from Goebbels, Hitler decided in February 1932 to run as a candidate for the office of Reich President against Hindenburg. Goebbels began the election campaign by insulting Hindenburg in the Reichstag and then being expelled. He quickly turned around: his election campaign was less about the candidate Hindenburg than about the "system", that is, the Weimar Republic. Hitler was built up as a counter-image, exaggerated in the sense of a Hitler myth . Goebbels relied on the media: half a million posters were pasted. Also new were a small record with a print run of 50,000, as well as a ten-minute sound film. Goebbels found the election result on March 13th disappointing: Hitler finished second with 30% of the vote. Hindenburg narrowly missed the absolute majority. A runoff election on April 10th became necessary. Goebbels increased the funds again: 800,000 copies of the Völkischer Beobachter were distributed. He rented a plane the week before the election so that Hitler could perform in three to four cities every day. This triumphal procession was called ambiguously “Hitler over Germany”. Hitler won another two million votes, but remained second.

The election campaign continued: on April 24th, the state parliaments were elected in Prussia and other countries. Goebbels challenged Chancellor Heinrich Brüning to a speech duel in the Berlin Sports Palace, which he refused. In the event he then played a speech by Brüning and was then able to refute it with relish to the cheers of his supporters. In the election in Prussia, he was elected to the state parliament via constituency 2 (Berlin). After he was re-elected to the Reichstag in July 1932, he resigned his state parliament mandate on August 24, 1932. Hermann Voss replaced him as a successor .

The Reichstag had to be re-elected on July 31, 1932, after Brüning had resigned and Franz von Papen was now in office. At the center of the polemics were the almost civil war-like conditions, especially the Altona Blood Sunday with 18 dead. Only Hitler would lead to the “National Socialist awakening”. Goebbels was able to give his first radio speech. The NSDAP was able to more than double its share of the vote and, with 37.3%, achieved the best result of a party in a Reichstag election before 1933. With 230 members, it was by far the strongest parliamentary group for the first time. Goebbels thought he had already reached our goal: "We will never give up power again, we have to be carried out as corpses." But Hindenburg did not want to hand over power to a Hitler at the time. The party fell into a deep crisis.

The Reichstag was dissolved again on September 12, 1932. New elections were scheduled for November 6, 1932 . Papen became the main opponent of the National Socialist election propaganda, alongside the SPD. These elections brought the National Socialists a setback with a loss of a good four percentage points. Now they had 196 MPs, which is still by far the largest group. Goebbels saw the cause that the workforce had not been addressed enough.

On January 15, 1933, the state parliament was elected in Lippe, a small country with only 100,000 eligible voters. The NSDAP now wanted to show that the setback from last November could be erased. Therefore, with a huge effort and commitment of the best speakers, the country was covered with an "election drum fire". The NSDAP was able to surpass the November result, but not match the July 1932 result. Nevertheless, this was portrayed as a victory in the party press.

As Reich propaganda leader Goebbels showed his inventiveness and his ability to organize. He consistently used all the technical possibilities available to him. He not only committed himself to the very last, but was also able to get the party apparatus to perform at its best. His program statements were not very specific, more important was the devaluation of political opponents. The person of Hitler was consistently brought into focus. Goebbels was not the creator of the "Hitler myth", but he succeeded in helping it to have far-reaching effects.

Magda Goebbels

After his separation from Else Janke, Goebbels had numerous fleeting love affairs. In November 1930 he met Magda Quandt , who had recently been working in the Gauge office. Magda was the divorced wife of the industrialist Günther Quandt and was enthusiastic about National Socialism. Goebbels and Magda married on December 19, 1931, Hitler was best man . Magda knew how to represent, her spacious apartment on Reichskanzlerplatz in Berlin-Westend became a popular meeting place. Hitler, who held Magda in high esteem, was also seen frequently. Goebbels' lifestyle was now far from socialist simplicity. Helga was born in September 1932, the first of a total of six children together.

In power

Foundation of the Propaganda Ministry

After the Reichstag election in July 1932 , in which the NSDAP was able to double its share of the vote, Hitler promised Goebbels a ministry for the entire field of education and culture. When Hitler was appointed Reich Chancellor on January 30, 1933, Goebbels expected to become Minister of Education. Out of consideration for the conservative cabinet partners and the Reich President, however, Hitler put him off until further notice. While Bernhard Rust was becoming the Prussian minister of culture, Walther Funk took over the press office of the Reich government as ministerial director and planned with Hitler to set up a central office for communication control and media policy. Goebbels, who was excluded from the closer circle of power and charged with preparing the Reichstag election campaign, felt offended and pushed into a corner. Only after Hitler had informed him on February 16 how far the plans had progressed, that Goebbels was supposed to be minister, and when the funding of the election campaign was secured shortly thereafter, did Goebbels' mood brighten.

In the Reichstag elections of March 1933 , the NSDAP did not achieve the hoped-for absolute majority with 44% of the votes, but it felt that it was the winner of the election compared to the German Nationals. With a slim majority of 52% in the governing coalition, Hitler was able to argue in the cabinet meeting on March 7th that “no political lethargy should arise”. One must set up a central office for public education. On March 13th, the Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda was established and Goebbels was appointed Minister.

Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda

Within six months, Goebbels created the organization with which he could monitor the entire cultural sector. In the Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda there was a separate department for each of the media: press , radio , film , theater , literature, i.e. literature of all kinds, visual arts , music . Here the content was monitored: what the newspapers were supposed to write, which films were made, how they were rated and promoted, which plays were put on the program, etc. The Reich Chamber of Culture was organized in the same way, with a sub-chamber for each of the categories mentioned. The Propaganda Ministry and the Chamber of Culture worked closely together. The chambers monitored and controlled the people: All newspaper people were in the Reich Press Chamber ; anyone who was excluded was therefore banned from working . The Reichsschrifttumskammer, for example, recorded not only authors, but also publishers and booksellers, while the Reichsrundfunkkammer not only recorded broadcasters, but also manufacturers and dealers of radio equipment.

The press was controlled in an indirect but very effective way. At first, the entire non-National Socialist party press disappeared. Bourgeois and confessional newspapers either ceased to appear or became increasingly party-owned over the years. With the editors' law of October 18, 1933, the editor was solely responsible for the content and thus independent of his publisher. However, he had to be entered in the "list of editors" of the Reich Press Chamber, which ensured loyalty to the line. The focus and content of the reporting were controlled centrally: for this purpose, there were daily press conferences in the Propaganda Ministry as well as a flood of press instructions. These were very precise. E.g. about the return of the half-Jewish Helene Mayer , who started for Germany at the 1936 Summer Olympics under pressure from abroad , only in the newspapers of Hamburg (where she arrived from the USA) and Offenbach (for whose club she started) in a short article to be reported. The state German News Office (DNB) was created in 1933 to provide news . A Nachzensur was no longer necessary. As the only exception, the Frankfurter Zeitung enjoyed a relative, if dwindling, independence until it too was discontinued in 1943.

Radio had already been nationalized in the Weimar Republic. Goebbels was able to take it over suddenly. He drove it straight from the Propaganda Ministry. A first propagandistic masterpiece was the transmission of the torchlight procession when Hitler was appointed Reich Chancellor on January 30, 1933. This suggested a revolutionary spirit of optimism. The aim of broadcasting should be to reach the “people in their entirety” in order to “soak” them “inwardly” with National Socialist propaganda. Two things were required for this: The program had to appeal to the broad masses, and they should also be able to receive it. For this reason, a Volksempfänger for 76 RM was already launched on the market in August 1933 , which was followed shortly before the start of the war by the “Deutsche Kleinempfänger” for only 35 RM, popularly known as “Goebbels-Schnauze”. The number of radio participants rose from 4.3 million in early 1933 to 11.5 million six years later. In addition, there was the community reception in companies and in public places. In this way, Hitler speeches, major events such as party conferences, but also the 1936 Olympic Games could be followed by a mass audience.

Goebbels was particularly interested in the film, especially the content and the propaganda direction. He was also said to have a very personal influence on the casting of the female roles: This earned him the nickname “Bock von Babelsberg”, as the UFA's huge studios were located in Potsdam-Babelsberg . Since the scripts had to be approved, very few finished films were banned. For the most part, apparently apolitical entertainment films were produced, which attracted the audience with popular stars. But there were also outspoken propaganda films, for example Triumph des Willens , Leni Riefenstahl's multi-award-winning film about the Nazi party rally in 1934, or Veit Harlan's anti-Semitic film Jud Suess . Goebbels pursued extensive concentration and nationalization in production, distribution and movie theaters. He got intoxicated by his power over the media: In March 1937 he noted:

“If we buy UFA today, we will be the largest film, press, theater and radio company in the world. With this I will work for the good of the German people. What a job! "

So Goebbels was a “media tsar” who - at least in theory - dominated the entire German media production. In any case, the control of everything that the German people could read, hear and look at was almost total. Goebbels saw himself as a general who led the people to conform to National Socialism:

“That is the secret of propaganda: to soak those whom the propaganda tries to capture with the ideas of the propaganda without even realizing that they are being saturated. [...] If the other armies organize and raise armies, then we want to mobilize the army of public opinion, the army of intellectual unification, then we really are the pointers of the time. "

With this in mind, he designed large-scale rallies such as May celebrations and party conferences. Evidence of his success were the results of the “elections” and referendums , which of course only asked for approval.

Goebbels' pride was to make Hitler happy with as high a percentage as possible. He declared this to be the "voice of the people", even if he embellished the undoubtedly high results a little, until he was finally able to show 99%. And it was not only on these occasions that Hitler's exuberant praise was bestowed upon him, always carefully noted in the diary.

"Degenerate art"

The term “ degenerate art ” initially referred to the fine arts, but then also to literature, theater and music. That the cultural policy of the “Third Reich” intended to cut off the diversity and liveliness of the Weimar Republic became evident with the public book burnings of May 10, 1933. Unwanted works disappeared from libraries and museums. Numerous journalists, authors, artists, musicians, film and theater people emigrated , others adapted or withdrew into an “ inner emigration ”.

Goebbels was reluctant to see that German Expressionism should also be suppressed, as it had inspired him in his youth. In 1933 he had his new official apartment furnished with pictures of Emil Nolde and wanted to keep it undisturbed. However, he bowed to Hitler's art dictation: In the exhibition “ Degenerate Art ” in Munich in 1937, Nolde was also among the ostracized. Over 16,000 works of art were confiscated, many sold abroad, and thousands were publicly burned in 1939. Finally, in November 1936, following a tip from Hitler, Goebbels also banned art criticism and any evaluation was forbidden.

The persecution of the Jews

After Hitler came to power on January 30, 1933, anti-Jewish actions took place in many places. Against this, the American Jewish Congress called for a boycott of German goods, which, however, was not supported by the governments. However, the consequences for Germany's reputation were devastating. In order to counteract the "foreign agitation", all Jewish shops and practices were to be boycotted by Jewish doctors and lawyers on April 1, 1933. Goebbels was responsible for preparing the propaganda for this boycott of Jews at home and abroad. The action did not bring the hoped-for response from the population and was not continued.

The Reich Chamber of Culture was also intended to serve Goebbels to force the Jews out of the cultural sphere. This turned out to be much more difficult than Goebbels had initially imagined. However, his criteria were stricter than those of the 1935 race laws : Here Jews and " half-Jews " were discriminated against, Goebbels also wanted to exclude " quarter Jews " as well as those married to "half" or "quarter Jews" as " Jewish relatives ". The Jews were often difficult to do without, so there were a large number of exceptions, also with regard to Jewish or "half-Jewish" spouses. On June 16, 1936 he complained to Fritz Sauckel :

“What should you do in art? Those who can do what are mostly still in the old waters. And our youth is still too immature. You can't make artists. But this eternal waiting in the drought is also terrible. But I will now start again to weed out the bad. "

Again and again he thought he had reached his goal, but in June 1939 he was still busy with this topic.

Goebbels increasingly sought to isolate the Jews in Germany and especially in Berlin in all areas of life. He had the police chief of Berlin, Wolf-Heinrich Graf von Helldorf , deliver a memorandum to this effect in May 1938. But the SD prevented a single Gaus from going it alone. Nevertheless, Goebbels had over 800 Jews arrested here in the " June Action " in 1938. The Jewish shops were marked, damaged or even looted, and nameplates of Jewish freelancers smeared. However, because of criticism in the party, possibly also on the part of Hitler, the action had to be broken off. Goebbels' declared goal, however, remained to make Berlin “ Jew-free ”. He agreed with Hitler that the Jews must have left Germany within ten years. The so-called Madagascar Plan was also discussed until 1940 .

Goebbels played a major role in the pogroms in the so-called “Reichskristallnacht” . On November 9, the anniversary of Hitler's attempted coup in 1923 , the traditional meeting of the party leadership took place in Munich. On this day the news came of the death of Ernst Eduard vom Rath , on which Herschel Grynszpan had carried out an attack two days earlier . Goebbels took up this opportunity. In a sharp speech to the party leaders present, he referred to pogroms that had already taken place in individual places and indicated that the party would not hinder anti-Jewish actions:

“I bring the matter to the Führer. He determined: let the demonstrations continue. Police withdraw. The Jews are supposed to feel the anger of the people one day. That's right. I am going to give the police and the party the appropriate instructions. Then I will speak briefly to the party leadership accordingly. Stormy applause. Everything rushes to the telephone. Now the people will act. "

So Goebbels ensured that local campaigns spread across the empire. Throughout Germany and Austria, thousands of synagogues and houses of prayer were set on fire, Jewish shops were demolished, around 100 Jews were killed and 30,000 were arrested. The police received precise orders on how to arrest Jews, but not abuse them, prevent looting, protect “German”, i.e. non-Jewish property and, for the rest, let the actions continue. There was a storm of indignation abroad. In addition, Goebbels had to recognize that large parts of the German population also rejected the pogroms.

On November 12, 1938, Goebbels took part in Goering's “Conference on the Anti-Jewish Measures after the Pogroms”. In addition to a lump sum " Jewish property tax " of one billion Reichsmarks, insurance payments due fell to the state. The " Ordinance on the Elimination of Jews from German Economic Life " and the " Ordinance on the Use of Jewish Assets " that followed soon afterwards served to finally remove Jews from the German economy. The " Law against the Overcrowding of German Schools and Universities " was passed in April 1933. Now Jews were also banned from cinemas and theaters, they were no longer allowed to own cars and motorcycles, and tenant protection was restricted. Goebbels ordered even stricter measures for Berlin: Here Jews were also banned from swimming pools, circuses and the zoo. Now an action began here in which Jewish tenants were evicted from “large apartments”.

Hitler's war policy

In the Sudeten Hitler demanded in 1938 the inclusion of predominantly by Germans occupied Sudetenland into the German Reich. His actual goal, however, was the annexation of the Czech part of Czechoslovakia . Goebbels apparently unreservedly supported this policy. His own opinion, on the other hand, was vacillating and contradictory: Far from Hitler, he was filled with fear that if the Sudetenland were to be annexed by force, France would fulfill its alliance obligations towards Czechoslovakia and England would also enter a war. However, he only confided in his diary that he considered Hitler's policy to be risky and dangerous; those around him could hardly notice it. In Hitler's presence, however, fear and worries fell away and gave way to unconditional trust in his Führer .

At the height of the crisis, on September 27th, Hitler paraded a motorized division through Berlin. The expected cheers from the population did not materialize, however. Goebbels registered this very precisely: Now he even dared to speak frankly to Hitler: “Then at the crucial hour I explained things to the Fuehrer as they actually behaved. The parade of the motorized division on Tuesday evening did the rest to create clarity about the mood among the people. And it wasn't for war. "

In the presence of Hitler, Goebbels' justified fear of war vanished and gave way to blind trust. For example, on September 26, after a walk in the garden of the Reich Chancellery, he wrote: “The Führer is a divinatory genius.” On October 1, after the end of the crisis, he had by no means put his contradicting feelings into order. In retrospect, the danger he had overcome was clear to him: “We all walked a thin tightrope over a dizzying abyss.” But he still wanted to prepare for a war: “Now we are really a world power again. Now it's time to equip, equip, equip! "

Despite all doubts, he zealously pursued the propaganda support of the crisis: he imposed press censorship on the Foreign Office so that it would not be “soft in the knees”. He had border incidents staged: “The press is picking them up.” Nothing was allowed to be reported about the passage of the motorized division. And he gave speeches that should raise the insecure: in front of employees of his ministry, in front of editors-in-chief, in front of 500 heads of the Berlin district and in front of a large audience in the Sportpalast in Berlin.

This dichotomy was also evident in the following year, 1939, when Hitler increased the pressure on Poland: Again he saw the situation as dangerous and was filled with fear of war. In his propaganda, however, he tried to get the German people in the right mood for this. He celebrated the Wehrmacht as the "strongest in the world". He presented Great Britain as a future attacker who was threatening Germany with a policy of "encircling". However, when Hitler secured the neutrality of the Soviet Union at least for the moment with the German-Soviet non-aggression pact of August 24th, Goebbels saw this as a “brilliant move”. When the English declaration of war came in after the German invasion of Poland on September 2nd, Goebbels looked like “a poodle that was doused”.

Private life

As a minister, Goebbels allowed himself a lush lifestyle. In June 1933 he secured an official apartment and had it converted by Albert Speer . In 1936 he bought a lake plot on the exclusive island of Schwanenwerder in the Wannsee and built a villa here. This was made possible by the party-owned Eher-Verlag , which acquired the rights to a later publication of the diaries for an advance of 250,000 RM and an additional 100,000 RM annually (today's purchasing power: 1,088,000 euros or 435,000 euros). In 1938 Goebbels forced his neighbor, a Jewish banker, to sell him his property well below its value. In 1936 the city of Berlin built a log house for him on a spacious lake plot in Lanke, northwest of Berlin, and a country house was added later. He often withdrew there. In the summer of 1939 he approved a new splendid service villa, which cost more than 3.2 million RM.

Goebbels' marriage to Magda was changeable: there were times of harmonious coexistence, but also numerous crises in which Hitler also intervened. There was a deep rift when Goebbels entered into a relationship with the Czech UFA film actress Lída Baarová in autumn 1936 . He appeared with her in public and intended to enter into a new marriage with her. Magda, meanwhile, sought consolation from Goebbels' State Secretary Karl Hanke . In October 1938, Hitler ordered the marriage to be maintained because Goebbels' family was presented in the media as a National Socialist model family. In addition, Magda always had Hitler's ear. Goebbels surrendered parted ways with his lover. The Goebbels did not find each other again until August 1939, at least in October 1940 their sixth child, Heide, the "child of reconciliation", was born.

Second World War

War propaganda

organization

Even before the war began, an organization for effective war propaganda was created. In order to receive timely and lively reports from the front, including films and photos, there were propaganda companies with a total of 15,000 men. They were subordinate to the High Command of the Wehrmacht (OKW), but worked closely with the Propaganda Ministry. - The official source of information about the war was the daily Wehrmacht report, which was released by Hitler. Here, too, the Ministry of Propaganda was able to participate in the formulation. - There were three successive conferences in the Ministry of Propaganda for the daily management of the media:

- The “Ministerial Conference”, chaired by Goebbels himself, from June 1940 at 11 o'clock. Initially only the heads of the political departments of the Propaganda Ministry took part, later representatives from other agencies and the Wehrmacht joined them. In the end there were 50 participants. Goebbels, already well informed by the domestic and foreign press and a preliminary Wehrmacht report, announced which priorities the daily propaganda should set, what should be treated casually or even withheld, and finally how to react to the opposing press.

- From November 1940, at 11:30 a.m., the “daily slogan conference” followed, at which a “daily slogan” was read out under the direction of the press chief of the Reich Government Otto Dietrich or his representative. This had previously been formulated by Dietrich according to Hitler's instructions and determined the presentation of the German press. Those attending the ministerial conference who were responsible for the domestic press appeared here.

- Finally there was the Reich Press Conference at 12:00 or 12:30 p.m., at which the Berlin representatives of the domestic press were familiarized with the slogan of the day. The provincial press received its instructions via “press circulars” or “confidential information”.

Since Dietrich was constantly around Hitler, he was occasionally able to cover up Goebbels with the slogan of the day, at least until the end of 1942. Both Goebbels and Reich Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop claimed responsibility for foreign propaganda . After Hitler had asked both of them to come to an agreement on September 7, 1939, “the next day he wrote down a Führer order in which it said that in the field of foreign policy propaganda […] issued the general guidelines of the Reich Foreign Ministers '". On this basis, the press officer of the Foreign Office, Paul Karl Schmidt, gave daily press conferences for the representatives of the foreign press. But Goebbels organized an "evening conference" for the same people.

International broadcasting was greatly expanded: after all, there were news broadcasts in 53 languages. The warfare in the west was supported by secret broadcasters, which were supposed to cause confusion among the population, for example during the French campaign in the early summer of 1940. The newsreel - a compulsory part of every cinema program - was a particular focus of Goebbels' attention, not only because of its intense impact, but also because Hitler examined it personally, at least during the first years of the war.

From May 1940 Goebbels published the weekly newspaper Das Reich . She should achieve intelligence at home and abroad and was very successful in this; the circulation rose to 1.4 million by 1944. This paper did not have to follow the slogan of the day. Plate propaganda was avoided. Every week Goebbels wrote the leading article and thus had his personal forum.

With these means the propaganda could be controlled in a comprehensive way. Nevertheless, there were independent sources of information that thwarted an information monopoly: The war situation was also made known through letters and reports from the soldiers at the front. The city dwellers experienced the bombing war with their own eyes. After all, eavesdropping on " enemy broadcasters " was prohibited under the penalty of death, but could not be prevented. The British BBC in particular enjoyed trust.

According to recent research, Goebbels' self-portrayal as the ruler of an almost all-powerful propaganda apparatus should not be confused with reality. This was characterized by a strong polycracy and the resulting disputes over competencies: Contrary to Goebbels' wishes, the press structure was largely determined by the Reichsleiter for the press, Max Amann , while the Wehrmacht had its own complex propaganda apparatus and Goebbels had competencies in foreign propaganda with the Foreign Ministry Ribbentrops and the East Ministry under Alfred Rosenberg had to share.

Especially since the turn of the war in 1942/1943, through which increasingly negative developments could be conveyed, there were massive conflicts between Goebbels' and Ribbentrops and Rosenberg's ministries regarding foreign propaganda, whose competencies he always wanted to cut in his favor in his discussions with Hitler. The disputes lasted until the final defeat in 1945. Personal vanity and sensitivities, but also differences in propaganda work, could be read from the conflicts. Goebbels, who studied and assessed the effects of German war propaganda abroad every day and in detail, urged to be extremely cautious about proclaiming military successes in order not to be exposed when the fortunes of war were turning. Several times, however, such as the landings of the Allies in southern Italy and Normandy, news of success was prematurely issued, which angered Goebbels as well as the too frequent commitment to alleged battles of fate, especially since it would soon become a habit to lose them. Again and again, Goebbels criticized the lack of flexibility of the propaganda, especially in his diaries with regard to these aspects. Goebbels noted in his diary on August 22, 1944, that one had to say goodbye to the “fantasies of 1940 and 1941” and “in view of the constantly growing crisis in the general war situation, one had to adapt to reduced war goals”.

Content

Initially, it was a question of blaming the outbreak of war not on Hitler's expansionist policy, but on the western “ plutocracies ”, which hindered Germany in its legitimate interests. With the invasion of the Soviet Union, anti-Soviet propaganda, which had been suspended for 18 months, revived. The eastern opponent was depicted as a barbaric horde, brutal and perpetrating atrocities. According to official information, the exhibition “ The Soviet Paradise ” from May 1942 attracted more than a million visitors. Increasingly, Judaism appeared as the real enemy, giving anti-Western and anti-Soviet propaganda an overarching enemy image.

Incidentally, the propaganda reacted to the course of the war. Goebbels was horrified when Dietrich declared the Soviet Union to be defeated in front of the press in October 1941 - but that was what Hitler had said shortly before; At any rate, Goebbels did not want any euphoria for victory at this point. When the advance in the east stalled in late autumn 1941, there was no longer any talk of a rapid collapse of the Soviet Union. However, when Goebbels was again filled with certainty of victory in May 1942, he painted a German settlement in the east in tempting colors. However , he did not let the German people know until January 1943 that the 6th Army was surrounded in Stalingrad in November 1942.

From then on, the propaganda became defensive. The struggle in the east was portrayed as a defense of Europe. Perseverance, increased war effort and extreme renunciation were required. The consequences of a defeat were painted in gloomy colors: the dismemberment of Germany, the being forced into a slave existence, the deportation of millions to Siberia. The staged or real massacre of Nemmersdorf , a village in East Prussia, in October 1944, which has not yet been clarified, gave the propaganda a rousing topic again.

The submarine war was supposed to bring temporary hope, but it had to be stopped in 1943. In the same year new miracle weapons were announced. Many expected these weapons to turn the war around. When they were finally used from June 1944, however, they did little. Ultimately, Hitler was also portrayed as the guarantor of victory, which, however, became implausible in view of the continuing defeats.

The unsuccessful assassination attempt on Hitler on July 20, 1944 once again provided the propaganda with welcome material - again they could portray the “Führer” of the Germans as benefiting from Providence .

Goebbels' role in suppressing the coup is often overestimated. Goebbels caused the guard battalion under Major Otto Ernst Remer to lift the cordon off the government district on July 20 by arranging a telephone call between Hitler and Remer. However, this was not the reason for the failure of the coup. Its prospects were slim from the start, since Hitler had survived. In addition, the conspirators did not succeed in getting radio and telecommunications completely into their own hands. The OKW under General Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel was able to initiate countermeasures as early as 4:00 p.m. From 5:42 p.m., news of Hitler's survival was repeatedly broadcast on the radio. Remer's phone call with Hitler did not take place until 6:35 p.m. and 7:00 p.m. Six days after the failed assassination attempt, Goebbels explained the circumstances of the assassination from his point of view in a radio speech to the people.

At the beginning of the war Goebbels had resolved to use his propaganda to ensure that "the people would hold". The November Revolution of 1918 could not be repeated. He achieved this: the war only ended with the total collapse of Germany.

Extermination of the European Jews

Goebbels' goal was to remove the Jews from Germany, primarily from Berlin. He had the first plans for this drawn up in mid-1940. However, these should only be realized after the war. In August 1941, Goebbels succeeded in getting Hitler to ensure that Jews had to wear the Star of David and were thus always recognizable as excluded. In addition, their food rations were reduced, and Goebbels also had the apartments marked.

The first deportations to the east began in October 1941. The extermination camps were also set up at this point . However, the transports from Berlin stalled. The February 8, 1942 Reich Minister for Armaments and Munitions appointed Albert Speer did not want to release the workers employed in armaments factories Jews and their families. Hitler did not make a decision on this question - despite Goebbels' repeated insistence. It was only under the impression of the defeat at Stalingrad that Goebbels managed to change Hitler's mind in January 1943. In March 1943 almost all Jews were deported from Berlin.

Goebbels was not involved in the decision-making process for the murder of European Jews . On March 27, he wrote about the extermination camps in his diary:

“Starting at Lublin, the Jews are now being deported to the East from the General Government. A rather barbaric and unspecified procedure is employed here, and not much remains of the Jews themselves. [...] A criminal judgment is carried out on the Jews, which is barbaric, but which they fully deserve. The prophecy that the Führer gave them for bringing about a new world war is beginning to be realized in the most terrible way. "

He looked back with pride at the extermination of the Jews in April 1943:

"I am convinced that with the liberation of Berlin from the Jews, I accomplished one of my greatest political achievements."

The Israeli historian Saul Friedländer also points to the great role that Goebbels' propaganda played in motivating the hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of helpers in the Holocaust.

Total war

As early as autumn 1942 Goebbels saw the war effort as inadequate. He called for a " total war ", that is, a war effort by the population that was increased to the limit. He envisioned that this could increase military performance by 10 to 15%. However, this would not have been remotely sufficient to compensate for the Allied superiority - but he did not want to see that. When the German defeat in the Battle of Stalingrad became apparent in December 1942 , the head of the party chancellery , Martin Bormann , was given the task of discussing the "question of total warfare" with Goebbels. In order to achieve this, Hitler set up a "committee of three", consisting of Bormann, the head of the Reich Chancellery , Hans Heinrich Lammers , and the head of the Wehrmacht High Command , Wilhelm Keitel . Goebbels was not a member of this committee, but close agreement with him should be maintained.

The problems then turned out to be much bigger than expected. Not half a million soldiers were missing from the front, but two. Goebbels succeeded in closing some luxury restaurants, but apart from that, really incisive measures did not come about, neither a consistent work obligation for women nor a tangible simplification of the administration. The other Gauleiter were not willing to adapt their lifestyle to the circumstances either. In order to achieve a general mobilization, especially the Gauleiter, Goebbels organized a large rally in the Berlin Sports Palace on February 18, 1943 . In a masterful production in front of a select audience, he received a stormy approval for the radical measures demanded during his Sportpalast speech . But Goebbels could not get the skills he wanted to implement, even if Hitler was enthusiastic about the speech. A familiar pattern emerged here. Goebbels had often claimed in his diaries that he had convinced Hitler of his ideas in discussions and had received assurances that they would now be implemented. In most cases, however, this only happened to a limited extent or not at all.

In May 1943 Goebbels was resigned. He saw Hitler completely occupied with his military duties. Domestic politics, by which he meant total war, is being neglected. He was also dissatisfied with foreign policy - he would have liked to persuade Hitler to sign a separate peace. After all, he saw the oppressive occupation policy in the east as unproductive and dangerous. Even his own propaganda no longer “sparked”. Instead, Hitler should speak to the people, but he refused to do so in a time of failure. Goebbels' criticism thus hit three central areas of political action. To terminate Hitler's allegiance because of this, however, never occurred to him. Again and again he made his confidence with regard to the military development his own, although he repeatedly indicated that he was clearly more pessimistic about the situation. In the summer of 1943, for example, he had already expressed the fear in his diaries that an impending two-front war could not be won militarily.

In the summer of 1944 the military situation was desperate. The landing of the Western Allies in France, begun on June 6, 1944, was a success. In addition, in July and August, Army Group Center was overrun by a huge offensive by the Red Army , a defeat far greater and more momentous than that of Stalingrad. In this situation, Goebbels renewed his push towards total war, supported by Albert Speer. On July 25th he was appointed “ General Plenipotentiary for Total War Deployment ” with the right to speak to Hitler and extensive powers of attorney.

Goebbels wanted to rebuild the state apparatus and deliver a million soldiers. It soon became clear, however, that the latter would be at the expense of the arms industry. This led to protracted and bitter arguments with Speer. Goebbels agreed with Hitler that it was about “soldiers and weapons”, Speer, on the other hand, insisted that only “soldiers or weapons” could be reached. Hitler agreed with Goebbels, but did not decide against Speer. Both sides found allies: Goebbels with Bormann and most of the Gauleiters, Speer with generals, but also with some Gauleiters - to Goebbels' annoyance. Finally, on December 1, 1944, both of them decided not to allow Hitler to push them into these positions any more. Hitler should now decide for himself how many soldiers and how many weapons he wanted. In the meantime, both had achieved achievements in this opposition that would otherwise hardly have been possible: Between July and October 1944, Goebbels was able to have almost 700,000 conscripts drafted. At the same time, the employment level in the defense industry peaked at over 6.2 million in October, before falling again.

Goebbels and the "final victory"

In 1939 Goebbels was concerned about war against Great Britain and France.

"If a world war really comes, which we all don't hope, then the situation will be serious, but not hopeless."

First there were four quick German victories in a row: in Poland , in Norway , in France , in 1941 in the Balkans , and initially in the Soviet Union and in the Africa campaign . Goebbels triumphed. However, when the German advance broke off in the winter of 1941 and a catastrophe could only just be avoided, he was skeptical about the war prospects. When the Wehrmacht advanced to the Caucasus and Stalingrad in the summer of 1942, he was euphoric again. After the defeat of Stalingrad in the winter of 1942/43, however, he could hardly imagine a German victory. This can only be read from his diaries, not from his propaganda.

Time and again he drew new courage from conversations with Hitler. He went to his headquarters about monthly. After the day-to-day business had been dealt with, a confidential one-to-one conversation followed after midnight, which often lasted until early morning. Now Hitler's ever-shown belief in the " final victory " was also able to capture Goebbels. Without criticism, he temporarily took over Hitler's illusions. In December 1944, for example, he believed that the Battle of the Bulge would lead to a tremendous German victory, a “ Cannae of unimaginable proportions”. Meanwhile, fuel and ammunition were scarce, and inferiority in the air was hopeless. At that moment he dismissed it as unimportant. After the talks with Hitler, he often dictated for his diary: “All batteries are now recharged.” But reality soon revived the previous skepticism. This acting and thinking on irreconcilable, contradicting levels is characteristic of Goebbels. In his diaries, however, there is no indication that this inner role conflict ever became a problem for him.

At the end of the penultimate German newsreel (No. 754), a speech by Reich Propaganda Minister Goebbels (delivered on March 11, 1945 in Görlitz ) was shown, in which he asserted that he believed in the final victory.

Murder of children and suicide

Goebbels' suicide was announced, for the first time in June 1943. In an editorial from October 1944 he wrote: “Nothing would be easier than to say goodbye to such a world in person.” On February 28, 1945, he said in a radio address at one Wanting to die defeat with his children. Logically, he had Hitler approve in March 1945 to be able to stay with his family in Berlin during a siege. When Hitler nevertheless ordered him to leave Berlin on April 28, 1945, he refused: he could not leave "the Führer in his hardest hour" alone. His death should also be a sacrifice for the future of Germany, as he wrote to Harald Quandt , the son of his wife's first marriage:

“Germany will survive this terrible war, but only if our people have examples in front of their eyes by which they can stand up again. We want to give such an example. [...] In the future you can only have one task, to prove yourself worthy of the worst sacrifice that we are ready and determined to make. I know you will. Don't be confused by the noise of the world that is about to set in. The lies [sic] will one day collapse and the truth will triumph over them again. It will be the hour when we will be above all, pure and flawless, as our faith and striving has always been. "

In doing so, he tied in with the thoughts of sacrifice from his youth.

But he didn't want to go down alone. On February 1, 1945, he declared Berlin a fortress and had the city brought into a state of defense. He wanted to stage his suicide in a bloody way: he was "determined to deliver a battle to the enemy as it should only be seen in the history of this war." This final battle for Berlin lasted from April 16 to May 1 was extremely lossy for both sides. The attackers lost over 350,000 men, the German losses can only be estimated, the number of dead alone was around 100,000.

On April 22nd, he and his family moved into Hitler's bunker at the Reich Chancellery (" Führerbunker "). At 1am on April 29, he was the best man when Hitler married Eva Braun. Hitler then appointed him Chancellor of the Reich . A day later, the newlyweds committed suicide . The following day, May 1st, Goebbels asked the Soviet Union for an armistice . Joseph Stalin , however, insisted on unconditional surrender . Goebbels gave up. His wife Magda had the children murdered with cyanide , perhaps she herself gave them the poison. The dentist , NSDAP member and member of the Waffen SS, Helmut Kunz , who initially administered morphine to the children , and Hitler's attending physician Ludwig Stumpfegger were involved in the murder of the Goebbels children . Then the two of them took potassium cyanide themselves. It is unclear whether Goebbels also shot himself. Their bodies, half charred, were found by soldiers of the Red Army in front of the bunker exit and later burned in 1970 and their ashes scattered in the Ehle near Biederitz .

Diaries