Degenerate Art (exhibition)

The exhibition "Degenerate Art" was a propaganda exhibition organized by the National Socialists in Munich . It was opened on July 19, 1937 in the Hofgartenarkaden and ended in November of the same year. At the same time, the “ First Great German Art Exhibition ” , which had opened the day before, took place so that “ Degenerate Art ” and the art promoted by the regime , known as “German Art”, were juxtaposed. The Munich exhibition was followed by a touring exhibition under the same title until 1941, which stopped in twelve cities, but sometimes showed other exhibits.

The Munich exhibition was organized by Adolf Ziegler , who also directed the previous confiscations . For example, the Ziegler commission considered “degenerate” in collections and museums such as the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne , the Folkwang Museum in Essen , the Kunsthalle in Hamburg , the Landesmuseum in Hanover and the New Department of the National Gallery in Berlin Works of art selected for use in the show, 600 of which were actually shown. They represented the vilified artistic styles Expressionism , Dadaism , Surrealism and New Objectivity . In order to achieve a “chaotic” effect, the works were deliberately hung in the exhibition rooms in an unfavorable way and insulted on the walls. The entire exhibition was thus geared towards its propaganda effect. According to official information, the “Degenerate Art” exhibition had 2,009,899 visitors and, even if this number is embellished, was until then one of the most popular exhibitions of modern art .

Prehistory and background

The Munich exhibition “Degenerate Art” was preceded by a number of exhibitions since 1933 in which modern art was presented as “degenerate” and both artists and civil servants were attacked. In 1937 it was not a singular event in Munich, but coincided with the “First Great German Art Exhibition” as a counter-exhibition in the context of a large number of cultural events in the “Festival Summer Munich 1937”.

Previous exhibitions

The exhibition “Degenerate Art” has been preceded by several smaller exhibitions (so-called “shame exhibitions”) since the Nazis came to power, which aggressively opposed art that was defamed as “degenerate”. On April 8, 1933, Hans Adolf Bühler , the recently appointed director of the Kunsthalle Karlsruhe , who was also the deputy director of the German Art Society , opened the exhibition “Government Art from 1918 to 1933”. The works exhibited in it came from artists who had been described by the “ Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur ” as “degenerate”, “art Bolshevik” and “corrosive”. With its staging of this understanding of art, the Karlsruhe exhibition assumed a role model position for other exhibitions of this kind.

Exhibitions were held in various museums with the aim of publicly criticizing directors and museum officials who had campaigned for modern art and were therefore dismissed. The Nuremberg gallery at Königstor and the palace museum in Dessau set up so-called “chambers of horror”. The “Degenerate Art” exhibition was opened in Dresden in September 1933 and then shown in other locations, where works from the local collections were integrated. In 1935 it was shown at the Nazi Party Congress, then in Munich and Darmstadt , among other places .

The exhibitions differed in their structure and the individual propaganda measures, but were comparable in their focus on denigrating artists and museum officials. Above all, the waste of taxpayers' money for the acquisition of works of art as well as their content and intentions, which were branded as denigrating "popular morality" and glorifying "cretins and whores", was criticized.

The Munich exhibition environment in 1937

1937 was a particularly active year for the Munich cultural scene. In addition to the two major exhibitions, the “Degenerate Art” and the “First Great German Art Exhibition” in the newly opened House of German Art , there were a variety of other events. It becomes clear that from around June of this year only artists who had no problems with the National Socialist rule and conception of art could exhibit in Munich.

In the first half of the year there were still exhibitions of modern artists, for example in Günther Franke's gallery , which first exhibited watercolors and paintings by Emil Nolde , then watercolors, drawings , woodcuts and lithographs by Franz Marc and sketchbook sheets by August Macke . The rejection of Modern Art, however, became increasingly more radically on display and played a more prominent role in decisions concerning exhibitions. Gauleiter Adolf Wagner reported to Joseph Goebbels on June 2 that there had been problems selecting the works for the First Great German Art Exhibition because the jury, made up of artists, was more based on their own taste and opinion of the artists than would have followed the official conception of art. Goebbels described the works presented to him as "bleak examples of art Bolshevism" and flew with Hitler to Munich on June 5, where Hitler personally intervened in the selection. After this incident, the exhibition planned for New German and French Art in the Neue Pinakothek was canceled. In November, the exhibition " The Eternal Jew " was opened in the library of the Deutsches Museum , which was extended due to the visitor attraction. It was opened by Joseph Goebbels and Julius Streicher and showed photos, statistics and paintings. This exhibition was expressly announced as a “major political show” and was intended to make the audience aware that “a defensive battle against Judaism and the plague of Jews must be waged”.

In contrast, there were many exhibitions in which art valued by the National Socialists was presented. Most of them were related to the "Festival Summer Munich 1937". It included the celebrations for the Day of German Art as well as the reopening of the Residenz Museum , the exhibition “The German Chamois” and the exhibition “Old German Graphics” in the Neue Pinakothek . The climax of all these events was the opening of the House of German Art and the First Great German Art Exhibition by Adolf Hitler , who gave his most programmatic speech on art on the occasion. According to the State Statistical Office, a total of 1,165,000 people visited Munich in 1937, 162,731 of them from abroad. It was the best visitor result in the city to date.

preparation

First planning and preparations

The Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda began planning an exhibition in the spring of 1937 in which the achievements of the National Socialist movement since 1933 in the social and political field were to be presented. It took place in Berlin from May to August 1937 and showed 3000 photographs, statistics and graphics that represented economic success. In addition, it was considered to run a parallel campaign against modern art. In April the ministry therefore asked the “art writer” Wolfgang Willrich whether he could put together material for an exhibition with the planned title “Give me four years of time”. It was made clear to Willrich that it was the intention of the Propaganda Minister to create “a clear contrast (in a sense a black and white contrast) between - as he put it - 'the arts of yesteryear and the art of our day'”. Willrich doubted that a large number of works of art could be obtained, since apart from the works of the Dresden traveling exhibition, most modern works of art would still be protected by sympathetic museum directors. The Reich Ministry of Propaganda gave Willrich powers of attorney so that he would also have access to the museum holdings stored in stores.

In the same month, Willrich began, together with the Hamburg drawing teacher and prehistorian Walter Hansen , to sift through material for the planned exhibition in the New Department of the National Gallery and in the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin. Both were given access to holdings that had been removed and placed in the magazines "for their protection" in the years since 1933. They made notes, following the example of the Dresden exhibition and Willrich's book (“ Cleansing the Temple of Art ”). The planned exhibition was intended to confront allegedly “degenerate” works of art with photographs of art recognized by the National Socialists.

Orientation towards Munich and establishment of the exhibition

Since several departments in the Reich Ministry of Propaganda disputed over the competencies and this hindered the work, Goebbels had more influence on the planning. When looking for an exhibition location, he now looked to Munich, where the planned exhibition was to be compared to the “First Great German Art Exhibition”, and commissioned Adolf Ziegler to view works of art for the exhibition. This formed a commission that included the personnel officer of the Reich Ministry of Education Otto Kummer , the director of the Folkwang Museum Klaus Graf von Baudissin , Wolfgang Willrich, and the Reich Commissioner for Artistic Design Hans Schweitzer . After seeing works of art in Cologne, Hamburg, Essen and Hanover, the commission appeared in Berlin on July 7th. The director of the new department of the Nationalgalerie, Eberhard Hanfstaengl , did not want to receive the Ziegler commission and left this task to his curator Paul Ortwin Rave . The commission visited the third floor, to which the works of the most despised artists had been banished and from which the private loans had already been removed. The paintings, watercolors and drawings by Pechstein , Nolde, Kirchner, Schmidt-Rottluff, Marc, Macke and others were put on the list of works to be confiscated. In some cases there was a discussion about the assessment of individual pictures, for example the painting “Sylt” by Erich Heckel, which was criticized by Schweitzer, but Ziegler did not appear to be sufficiently “degenerate” for confiscation. The other searches in the run-up to the first wave of seizures in the museums were carried out in this way. The selected works should be listed with three pieces of information, the details of when it was purchased, under which director it was done and what the price was. The selected pictures were sent to Munich no later than the third day after the commission's visit.

Preparation (external web links)

|

The exhibition location in Munich was the Archaeological Institute in the Hofgartenarkaden . On the ground and first floors, the plaster collection rooms were cleared and partition walls were put in, which were supposed to half-close the windows and hide the actual wall decoration and painting of the exhibition rooms. The pictures were hung as close and high as possible on these walls, sometimes without a frame. A special feature of the Munich exhibition “Degenerate Art” was to write the name of the artist, the title of the work, the museum, the date of purchase and the purchase price directly on the wall in addition to the works of art. Defamatory sayings and caricatures were also painted on the walls. With the help of photos of the “ Dadaism Wall”, the dynamic development of the hanging can be understood as an example: On July 16, Hitler can be seen in front of paintings by Kurt Schwitters hanging crookedly , while they were hanging at the opening on July 19. Likewise, the sixth room was closed to the public once and the seventh room several times, as changes were still being made in both while the exhibition had already opened. From the second week of the exhibition, the seventh room was only accessible to journalists and visitors with special permission. In addition, the short period of time that was available to prepare the exhibition caused problems. The exhibition rooms on the ground floor could not be made accessible to the public until July 22nd, three days after the official opening, because the organizers had not finished setting up on time.

The exhibition

First floor

The exhibition (external web links)

|

The tour of the exhibition began on the upper floor. On the landing, before entering the first room, the visitor was the wooden crucifix by Ludwig Gies see that he had in 1921 produced a design for a memorial, which had caused a scandal, and since 1923 as the acquisition of the local museum association in the Municipal Museum Stettin had hung. It led to the works of art shown in the first exhibition room, all of which showed Christian motifs. Emil Nolde was represented with most of the works, including the nine-part altar The Life of Christ and the painting Christ and the Sinner . In addition, the pictures Descent from the Cross by Max Beckmann , Elias by Christian Rohlfs and Pharisees by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff could be seen.

In contrast, the works in the second room were not selected on the basis of a thematic context, but all came from Jewish artists. Among other things, there were pictures of the village scene and winter by Marc Chagall , a self-portrait by Ludwig Meidner , musicians, mandolin player by Jankel Adler , two floating figures by Hans Feibusch and the exotic landscape by Gert Wollheim . On the wall opposite the pictures were written, comments and photographs. There was a list of names that were supplemented with terms such as “Jew” or “Bauhaus teacher”. In addition, slogans such as “Plan of deployment of the cultural Bolsheviks ” or Kurt Eisner's quotation “The artist must be an anarchist as an artist” were written on the wall .

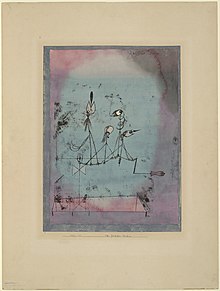

In the third room, thematically arranged groups of works were presented with wall slogans. Nude paintings by Max Ernst , Ernst Ludwig Kirchner , Otto Mueller , Paul Kleinschmidt and Karl Hofer were exhibited under the motto “Mockery of the German woman ideal: cretin and whore ” . The socially critical works, which were strongly hostile to the Nazis , were also shown in this room. The pictures of war cripples and trenches by Otto Dix , who had already traveled through Germany with the Dresden traveling exhibition , were commented on as “painted military sabotage”. In the third room there were pictures by Max Pechstein , Schmidt-Rottluff, Kirchner and Müller. In addition, the so-called Dadaism wall was installed in this room . Some details from Wassily Kandinsky’s works had been carefully enlarged on the wall, which should probably show that anyone could paint such works and thus denied the works their value. Two Merz pictures by Kurt Schwitters , swamp legend by Paul Klee and two issues of Dada magazine were hung over the wall painting . This disordered ensemble was commented on with the out of context quote “Take Dada seriously - it's worth it!” By George Grosz .

- Works in the third room (selection)

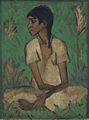

Three women by Otto Mueller , 1915

For the fourth room, pictures were chosen that had no thematic connection. The works of the Brücke artists Erich Heckel , Schmidt-Rottluff, Pechstein, Nolde and Kirchner as well as Oskar Kokoschka , Beckmann and Rohlfs were only provided with the artist name, title, museum and purchase price. Wall lettering and text panels were missing. This changed again in the following fifth room. Under the heading “Madness becomes method” there were five pictures by Johannes Molzahn , under “Crazy at any price” there were seven pictures by Kandinsky, which were hung in steps, for which no further information or details about the work were given. With these slogans the works should be denied any seriousness. In addition to Kandinsky's works, there were seven cityscapes painted by Lyonel Feininger . Furthermore, were expressionistic landscapes and still lifes by Schmidt-Rottluff and Kirchner and other works, among others, Oskar Moll , Ernst Wilhelm Nay and Hanna Nagel had been painted, exhibited.

In the sixth room, there was almost no labeling of the works of art on display. Information on the purchase and the museum to which the work belonged was only given in isolated cases. An entire wall was hung with works by Lovis Corinth , including Ecce Homo and the Trojan Horse . The artist's name was first written on the wall, but then painted over. Franz Marc's The Tower of the Blue Horses , the most famous picture of the exhibition, was shown in this room . However, it was removed from the exhibition after the German Officers' Association protested at the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts against the fact that pictures of a deserving soldier who died near Verdun in the First World War were shown in the exhibition.

- Works in the sixth room (selection)

Ecce Homo by Lovis Corinth , 1925

The Tower of the Blue Horses by Franz Marc , 1913

Above the door to the seventh room was the writing “They had four years time” , which followed the final sentence “Now German people, give us the time of four years, and then judge and judge us.” From Hitler's government statement of February 1st 1933 alluded to. Works by university professors who had been dismissed since 1933 were exhibited in this room. Except for the comment "Such masters have been teaching German youth to this day!", It was not provided with lettering or work information, since the originally attached lettering had been painted over, even if it was still showing through. The pictures shown in room seven were by Hans Purrmann , Karl Caspar , Fritz Burger-Mühlfeldt , Paul Bindel , Maria Caspar-Filser , Heinrich Nauen and Edwin Scharff .

ground floor

On the ground floor, the focus of the exhibited works shifted from oil paintings to watercolors , graphics and books . In contrast to the presentation on the upper floor, the content of the exhibited works was not structured at all. The artist of a group of works or the origin of a part of the collection were only given in isolated cases; the place of origin was noted in chalk on some of the frames. Probably because of the lack of information, the press barely reported on this part of the exhibition. There are also hardly any written records from visitors.

Two sculptures were exhibited in the anteroom on the first floor . One was the figure Schmied von Hagen , made of wood , by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, the other was the plaster head (large head) by Otto Freundlich , to which the exhibition organizers gave the defamatory title Der neue Mensch ; the head was depicted on the title page of the exhibition catalog. In the adjoining first room on the ground floor, pictures from the Dresden traveling exhibition , including works by Guido Hebert , Constantin von Mitschke-Collande , Pol Cassel , Friedrich Skade and Hans Grundig, were hung on a wall . The paintings Roman (Five Figures in Space) and Concentric Group and three more by Oskar Schlemmer also hung there . Volumes from the magazine Junge Kunst were displayed in the showcases in the first room . They also exhibited the book Art and Power by Gottfried Benn , the volume of poems Sounds with woodcuts by Kandinsky and other works.

In the second room there was the artist's quote out of context over an entire wall: “We prefer to exist unclean than to go under cleanly, incapable of being decent, we leave stubborn individualists and old maidens, no fear for the good reputation. Wieland Hertzfeld Malik Verlag. “ In the stitch caps above there were pictures like Sicilian woman and child with green necklace by Alexej von Jawlensky , worker in front of the factory by Dix and melancholy by Schmidt-Rottluff. Furthermore, paintings by Nolde, Heckel, Drexel and Kokoschka hung in this room. In the showcases in the second room, mainly graphics from Dresden museum collections and the Berlin Kupferstichkabinett as well as works from Essen and Düsseldorf museum collections were shown, including the etchings Descent from the Cross by Max Beckmann and In the Café by George Grosz and the woodcut Ziegelei b. Darel von Schmidt-Rottluff.

A list of the defamed artists can be found in the category: Artists in exhibitions “Degenerate Art” .

effect

propaganda

The “Degenerate Art” exhibition, with its counterpart, the “ First Great German Art Exhibition ”, was conceived as a double propaganda show in which works of art that were considered “degenerate” were systematically juxtaposed with “pure German art” promoted by the system . This comparison was indeed necessary because there were no clear definitions for “degenerate” and “pure German” art, but rather both were only given contours in direct confrontation. The exhibition was designed in such a way that the art rejected by the National Socialists was radically attacked. Jewish artists were attacked for their beliefs or their origins, Marxist or pacifist artists for their worldview . This was done by means of quotations on the walls: On the one hand, by quotations from members and sympathizers of the National Socialist movement, in which allegedly “degenerate” modern art was attacked; on the other hand, through statements taken out of context by representatives and supporters of this art, so that a false or deliberately falsified impression of the intentions of the artists was conveyed.

The wording of the tapes on the wall specifically suggests that they go back to Wolfgang Willrich , who also wrote the diatribe “Cleansing the Art Temple” published in early 1937 (some of the sayings are very similar to sentences from this work).

The press reported extensively and in sensationally designed articles about the exhibition, with particular emphasis on the high number of visitors and the number of foreign visitors. In most cases, the tone of the reports was polemical. They usually picked up on Nazi propaganda relating to art. Furthermore, the Reich Propaganda Ministry tried to get the highest possible number of visitors. With an entry ban for people under the age of 21, an aura of the forbidden was created around modern art and thus the “attractiveness” of the whole thing was increased. In addition, group trips were organized for NSDAP members.

A special element of the propaganda around the exhibition “Degenerate Art” is the exhibition guide “Degenerate Art” . It does not refer directly to the exhibition, but presents in the form of a brochure the position of the National Socialists in relation to “Degenerate Art”. as well as their idea of what “degenerate art” actually is. The guide to the exhibition was not planned from the beginning and only appeared towards the end of the exhibition, which is why the individual criticized groups of works were commented on with quotations from Adolf Hitler from the speech at the opening of the Haus der Deutschen Kunst.

Reactions

The reactions to the exhibition “Degenerate Art” were divided. The majority of visitors rejected the works of art shown and followed the exhibition organizers in their assessment. However, only a small number of them took up the ideology of the National Socialists fanatically, while the majority showed genuine indignation at the art on display. Some visitors wrote down information about the pictures, particularly the purchase amounts, and berated the directors and officials who made the purchases. Some also discussed the works cautiously, while others looked at the pictures with a laugh. In front of the works of some artists, astonishment about the exhibition of their works could also be perceived as "degenerate", for example in front of the wall with pictures of Lovis Corinth , whose name was not attached, but whose known works (see above) were immediately recognized by the visitors as were judged of particular quality .

Foreign guests also partly joined the National Socialist view of art.

In contrast, individual collectors, including the Hanoverian manufacturer Bernhard Sprengel and Josef Haubrich from Cologne, had the courage to complete their own collections of modern art by consciously buying works of art that the Nazis had sorted out as "degenerate". Some foreign art museums acted similarly. a. the art museum Basel .

In fact, some foreign newspapers have taken the view that the large number of visitors to the exhibition is a "pilgrimage to the praised modernity" . This interpretation was sharply attacked by National Socialist newspapers, and eyewitnesses such as Paul Ortwin Rave confirmed that only a small proportion of the visitors came to say goodbye to the works of art that were now explicitly branded by the National Socialists.

Significance for artists and art politics (the expressionism dispute )

The “Degenerate Art” exhibition came at the end of a discussion of art within the National Socialist movement, which was ultimately decided by Adolf Hitler himself: Until 1937, two opposing positions stood opposite each other in the expressionism dispute : One, prominently represented by Joseph Goebbels , sympathized with Expressionism as “German, Nordic art”, the other opinion, that of Alfred Rosenberg , was that of Adolf Hitler himself: it was decidedly against modern art and prevailed.

The exhibition was preceded by the first major confiscation campaign in German museums. Previously, many of them had only stored works that were considered "degenerate" in their magazines and thus withdrawn from the access of the National Socialists. However, the Ziegler Commission was now able to inspect these holdings with an official power of attorney. While the exhibition in Munich was still open, there was another wave of confiscations, so that the majority of the works of art in the museum's possession that were considered “degenerate” were removed from them. They were collected centrally in Berlin. Some of them were sold or auctioned abroad as part of the exploitation of Degenerate Art , some were burned. Emil Nolde , who was highly valued by the Goebbels faction, was, in the opinion of Adolf Hitler and his supporters, “particularly degenerate” and therefore most frequently represented in the exhibition - and in the first room.

aftermath

Traveling exhibition "Degenerate Art"

Following the Munich exhibition, a traveling exhibition was set up , which was also entitled "Degenerate Art", which stopped in various cities in the German Reich between 1938 and 1941 , including Berlin in the Haus der Kunst at Königsplatz 4, Leipzig , Düsseldorf , Salzburg , Hamburg and Vienna . The selection of the exhibited works differed in part from that in Munich, also because the exhibition organizers were now able to choose from a total of 17,000 confiscated works. This selection was changed and adapted from station to station, which in part had to do with the changing political situation up to 1941. In addition, the propaganda effect was intensified. An accompanying booklet was available, posters were distributed and the selection of works was carried out more closely from this point of view. The reconstruction of the traveling exhibition is more difficult than that of the Munich exhibition. Fewer photographic documents have been preserved and fewer publications have appeared. The first major investigation of the individual stations of the traveling exhibition did not appear until 1992 with the catalog “Degenerate Art. The fate of the avant-garde in Nazi Germany ”by Christoph Zusatz . His dissertation from 1995 represents the most detailed treatment of this topic to this day.

Exhibitions

The exhibition "Degenerate Art" was u. a. supplemented or received and processed by the aforementioned traveling exhibition. As early as 1938 there was a counter-exhibition in London . After the Second World War , the number of such exhibitions increased. One example is the “Degenerate Art” exhibition . Iconoclasm 25 years ago , which was held in 1962 in the Haus der Kunst in Munich . In mid-February 1991, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art opened the “Degenerate Art” exhibition, in which 170 of the 650 pictures and sculptures shown in Munich in 1937 were presented. This exhibition was supplemented with a wide-ranging accompanying program that included lectures, film screenings, conferences, concerts and symposia. The exhibition in Los Angeles coincided with a time when art and how far it was allowed to go was under discussion in the USA and thus became a political issue. In 2007, to mark the 70th anniversary of the “Degenerate Art” exhibition, several exhibitions were held that primarily dealt with the fate of the art works in museums. For example in the Sprengel Museum in Hanover and in the Kunsthalle Bielefeld .

research

For the reconstruction of the Munich exhibition “Degenerate Art”, the numerous photographs , the book “Art dictatorship in the Third Reich” by Paul Ortwin Rave, in the appendix of which artists, oil paintings and an estimated number of exhibited graphics are listed, were a factual article by the art critic Bruno E. Werner in the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung of July 20, 1937 and a list of works in the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung of July 24 are used. For the book “Die 'Kunststadt' Munich 1937. National Socialism and 'Degenerate Art'”, published in 1987 for the 50th anniversary of the Munich exhibition “Degenerate Art”, in which a complete reconstruction was attempted for the first time, notes by Carola Roth and Letters from the curator of the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen Ernst Buchner to Eberhard Hanfstaengl evaluated. The hanging of the exhibits was largely reproduced. Nevertheless, there is still no clarity in some individual cases. Werner's report stated that a self-portrait by Paula Modersohn-Becker was exhibited in the seventh room . This picture was not mentioned in the list of works published four days later, nor in the book Raves. This self-portrait cannot be proven on any photo.

When preparing an exhibition of Otto Freundlich's works in 2017, it was discovered when comparing historical photographs that the sculpture Großer Kopf , which was to be seen on the title of the exhibition guide to “Degenerate Art”, was lost during the exhibition hike and then by a Counterfeit had been replaced.

In March 2003 the research center “Degenerate Art” was founded, which was set up at the Art History Institute of the Free University of Berlin . Since April 2004 she has also been represented at the Art History Seminar of the University of Hamburg with her own focus.

Exhibition guide

-

Degenerate art". Exhibition guide. Munich / Berlin 1937.

- Reprinted in: Peter-Klaus Schuster (Ed.): National Socialism and “Degenerate Art”. Die Kunststadt München 1937. Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, pp. 183–216.

- Reprint: Berlinische Galerie (Ed.): Degenerate “Art”. Exhibition guide. Walther König, Cologne 1988.

literature

- Jutta Birmerle: Degenerate Art: Past and Present of an Exhibition . BIS-Verlag, Oldenburg 1992, ISBN 3-8142-1051-4 .

- Sabine Brantl: House of Art, Munich. A place and its history under National Socialism. Allitera Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-86520-242-0 .

- Uwe Fleckner (ed.): Attack on the avant-garde. Art and Art Politics in National Socialism . Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 3-05-004062-9 .

- Peter Sager, Gottfried Sello (text); Petra Kipphoff (editor): “Degenerate Art”. Documentation of an outrage. In: Zeit magazine , No. 26/1987

- Peter-Klaus Schuster (Ed.): National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The art city of Munich in 1937 . Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-7913-0843-2 .

- Robert S. Wistrich : A weekend in Munich. Art, Propaganda and Terror in the Third Reich . Insel Verlag, Leipzig 1996, ISBN 3-458-16769-2 .

- Uta Baier: The Nazis didn't have a clear concept . In: Die Welt , July 19, 2007.

Web links

- Research Center "Degenerate Art"

- The exhibition “Degenerate Art” on dhm.de.

- Series of images on n-tv media library

- Ursula A. Ginder: Munich 1937: The Development of Two Pivotal Art Exhibitions.

- Research center “Degenerate Art”. Art History Institute of the Free University of Berlin ; Database for the confiscation inventory of the “Action 'Degenerate Art”, search for artists and titles

- List of “Degenerate Art”: Complete directory as a PDF file through a digital reproduction of the directory of the Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda from around 1941/1942; kunstraub taz.de, project by taz and ODC

- Georg Kreis : When modernity was pilloried. In: Tages-Anzeiger / Der Bund , October 20, 2017.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 99.

- ^ A b Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 94.

- ↑ The widely used title "Mirror Images of Decay in Art" was first used in 1949 by Paul Ortwin Rave , based on the headline of an article by Richard Müller from the Dresdner Anzeiger of September 23, 1933. See Christoph surcharge: degenerate art. Exhibition strategies in Nazi Germany , Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft Worms 1995, page 123.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 95.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 37.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, pages 38 and 39.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 43.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 41.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 51.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, pages 41 and 46.

- ^ Robert S. Wistrich: A weekend in Munich. Art, propaganda and terror in the Third Reich , Insel Verlag, Leipzig 1996. Page 60.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 53.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 95.

- ^ A b Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 96.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The city of art Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, pages 96 and 97.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 103.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 105

- ↑ Entry in the database "Degenerate Art"

- ↑ Image: Christ and the Sinner by Emil Nolde ( Memento from October 5, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 106.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 108.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The City of Art Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 109.

- ↑ a b Mandy Wignanek: Fake Icon. The big head in the propaganda exhibition Degenerate Art. In: Julia Friedrich (Ed.): Otto Freundlich - Cosmic Communism . Prestel Verlag 2017, pp. 206–215. ISBN 978-3-7913-5639-6 .

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 99.

- ↑ Uwe Fleckner (ed.): Attack on the avant-garde. Art and Art Politics under National Socialism , Akademie-Verlag, page 92.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 101.

- ^ A b Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 98.

- ↑ a b Vanessa-Maria Voigt: Art dealers and collectors of the modern age under National Socialism. The Sprengel Collection 1934 to 1945 , Reimer, Berlin 2007, ISBN 3-496-01369-9 .

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The city of art Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, pages 98 and 99.

- ↑ The Twittering Machine , moma.org, accessed on February 23, 2013.

- ↑ Uwe Fleckner (ed.): Attack on the avant-garde. Art and Art Politics under National Socialism , Akademie-Verlag, page 90.

- ↑ Uwe Fleckner (ed.): Attack on the avant-garde. Art and Art Politics under National Socialism , Akademie-Verlag, pages 90 and 91.

- ↑ Uwe Fleckner (ed.): Attack on the avant-garde. Art and Art Politics under National Socialism , Akademie-Verlag, page 89.

- ↑ Uwe Fleckner (ed.): Attack on the avant-garde. Art and Art Politics under National Socialism , Akademie-Verlag, page 91.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 9.

- ↑ Jutta Birmerle: Degenerate Art: Past and Present an exhibition , BIS-Verlag, Oldenburg 1992. Page 7 and 8. FIG.

- ↑ 1937. In search of traces - In memory of the 'Degenerate Art' campaign . ( Memento from June 23, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Sprengel-Museum, Hanover

- ↑ 1937. Perfection and Destruction . Bielefeld art gallery

- ↑ Isabel Schulz, Isabelle Schwarz: 1937. In search of traces - In memory of the “Degenerate Art” campaign , Sprengel Museum and Authors, Hanover 2007.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The city of art Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 102.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster: National Socialism and "Degenerate Art". The Art City of Munich 1937 , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1987, page 118.

- ↑ Research Center “Degenerate Art”. Gerda Henkel Foundation, accessed on August 29, 2011.