National-socialist German Workers' Party

| National-socialist German Workers' Party | |

|---|---|

The party eagle ("national emblem", new version) stands over a swastika in an oak leaf wreath; not identical to the imperial eagle at the time of National Socialism due to the direction of view .

Party flag of the NSDAP (from 1933 to 1945 - from 1935 with the swastika shifted to the left - also the national flag of the German Reich ).

|

|

| Party leader |

Karl Harrer (1919–1920 / DAP ) Anton Drexler (1920–1921) Adolf Hitler (1921–1945) Martin Bormann (1945) |

| founding | February 20, 1920 in Munich |

| Ban | October 10, 1945 |

| head office |

Munich (1930: Brown House ) office Berlin |

| Youth organization | Hitler Youth (HJ) |

| newspaper | National observer |

| Alignment | National Socialism |

| Number of members | 7.5 million (1945) |

The National Socialist German Workers' Party ( NSDAP ) was a political party founded in the Weimar Republic , whose program and ideology ( National Socialism ) was determined by radical anti-Semitism and nationalism as well as the rejection of democracy and Marxism . It was organized as a tight leader party . Its party chairman was from 1921 the future Chancellor Adolf Hitler , under whom it ruled Germany in the dictatorship of National Socialism from 1933 to 1945 as the only approved party .

After the end of the Second World War in 1945, it was classified as a criminal organization by the Allied Control Council Act No. 2 with all its subdivisions and was thus banned and dissolved. As in 1925, their property was confiscated and confiscated. In the Soviet occupation zone - the later GDR - this meant the ban on owning or showing your symbols, for whatever reason, in force until German reunification .

Since the founding of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1949, any advertising for them in the form of writings, words or signs was forbidden, and their private ownership was not restricted.

A regulation similar to that of the Federal Republic had been made in Austria four years earlier, in 1945, with the Prohibition Act .

The NSDAP in the Weimar Republic

Beginnings and prohibition in 1923

On the evening of February 24, 1920, the new party was publicly announced in Munich's Hofbräuhaus by renaming the German Workers 'Party (DAP) to the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), with the official change from DAP to NSDAP already being completed on February 20, 1920 . The abbreviation "NS" was intended to emphasize the peculiarity of the party and was introduced past the party leadership by Adolf Hitler, Dietrich Eckart , Hermann Esser , Rudolf Hess , Ernst Röhm and Gottfried Feder . On that evening, the NSDAP published its party program ( 25-point program ) with the main points "Repeal of the Versailles Peace Treaty ", "Withdrawal of German citizenship from Jews " and "Strengthening the national community ".

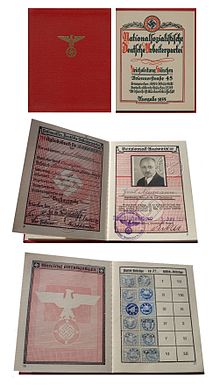

Shortly afterwards, the NSDAP began to issue the first membership cards. Since it did not want to appear as an “insignificant micro-party”, the official party directory began with the number 501. Hitler was listed with the number 555 in this directory.

As early as 1920, the NSDAP cooperated with the German National Socialist Workers' Party (DNSAP) in Austria and Czechoslovakia . In August 1920 they held an “intergovernmental meeting” in Salzburg, after which there was an “intergovernmental secretariat” based in Vienna. In August 1923, a joint, transnational party congress was even held in Salzburg, at which, however, disputes over the political strategy and methods to be pursued escalated.

In 1922 a number of NSDAP bans were issued in several German states: in Baden on July 4th and in Thuringia on July 15th. On the basis of the Republic Protection Act of July 21, 1922, bans followed in Braunschweig (September 13), Hamburg (October 18), Prussia (November 11) and Mecklenburg-Schwerin (November 30). The enforcement of the prohibitions was of varying severity. In Prussia, the NSDAP ban also led to the ban on the local NSDAP front organization Großdeutsche Arbeiterpartei , which was originally supposed to be founded as the first North German NSDAP local group .

By 1923 the NSDAP was able to gain a larger following , especially in Bavaria , and took the desolate situation in the German Reich caused by the war in the Ruhr and inflation as an opportunity for the Hitler putsch , which failed miserably on November 9, 1923.

On the same day, on the basis of Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution , President Friedrich Ebert transferred executive power to the head of the Army Command, Hans von Seeckt . On November 23, 1923, the latter issued a nationwide ban against the NSDAP, which was to apply until February 1925. The entire party assets were confiscated, the office in Munich was closed, and the party newspaper Völkischer Beobachter was banned. The German Volkische Freiheitspartei (DVFP), whose chairman Erich Ludendorff played a central role in the putsch, and the Communist Party of Germany , whose Hamburg uprising had failed a few weeks earlier , were also banned .

Hitler was in custody from November 11, 1923. In a process before the Munich People's Court he was on 1 April 1924 for high treason to five years imprisonment convicted, but of which he had to serve only a few months. Previously, he had commissioned the editor-in-chief of the Völkischer Beobachter, Alfred Rosenberg , to ensure the cohesion of the National Socialists. Under the pseudonym Rolf Eidhalt (an anagram from Adolf Hitler) he founded the Großdeutsche Volksgemeinschaft . But he lacked the necessary authority to prevent the movement from fragmenting. He was soon ousted from the party leadership by Hermann Esser and Julius Streicher . In addition, a "Völkischer Block in Bayern" formed under Alexander Glaser , who also campaigned for National Socialist votes. Other National Socialists such as Gottfried Feder , Gregor Strasser and Wilhelm Frick formed an electoral alliance with Ludendorff and his rather bourgeois-nationalist DVFP, which was quickly re-admitted after the acquittal of its chairman in the Hitler trial. Under the name of the National Socialist Freedom Party , they ran in the Reichstag elections on May 4, 1924 and achieved 6.6 percent of the vote. Hitler feared that this would result in his "movement [...] becoming a purely bourgeois rival party" and decidedly rejected this cooperation. However, while in custody he was unable to influence developments. In August 1924, the German Volkish and National Socialists joined forces to form the “National Socialist Freedom Movement Greater Germany”, which was led by Ludendorff, Gregor Strasser and Albrecht von Graefe . The organizational unit only superficially covered the violent internal factual and personal contradictions that shaped the new party. In the Reichstag elections of December 7, 1924 , in which the anti-republican forces generally lost a lot, they only gained 3 percent of the votes cast. Another splinter group formed in northern Germany. The “National Socialist Working Group” of the Lüneburg lawyer Adalbert Volck saw itself as a “pure Hitler movement” and appeared strictly anti-parliamentary.

Reorganization and splinter party 1924–1930

After his release from imprisonment in a fortress in December 1924, Hitler was not deported, although he was still an Austrian citizen at the time , but was allowed to stay in the German Reich. In February 1925 the party was re-established. On May 26, 1930, the NSDAP bought the "Brown House" for 805,864 Reichsmarks after the rooms at Schellingstrasse 50, where the party headquarters had been located since 1925, had become too small.

In July 1925 the first volume of Hitler's book Mein Kampf was published ; in December 1926 the second. Contrary to what the title suggests, the book is not just an autobiography , rather the programmatic statements predominate . For the NSDAP, the ideologemes that Hitler unfolded here, especially those relating to “ living space in the east ” and “removing the Jews”, became binding. There are also furious attacks on Marxism and democracy .

Hitler dissolved the NSDAP from its alliance with the Völkische and began to reorganize it into a leader party with the aim of a legal takeover of power. Decisive steps in this direction were taken at the Bamberg Führer Conference on February 14, 1926, in which Hitler was able to prevail against a group around Gregor Strasser with his ideas. This was completed with the resolution on the party statutes of May 22, 1926, which corresponded entirely to Hitler's ideas.

After the Austrian "sister party" DNSAP had split several times over the question of whether to subordinate themselves to Hitler and the German NSDAP or to remain organizationally independent, the Viennese high school professor Richard Suchewirth founded the National Socialist German Workers' Association in May 1926 . Soon afterwards it renamed itself the NSDAP - Hitler Movement and functioned more or less like a regional association of the German NSDAP. There was also an Austrian branch of the SA, the Vaterländischer Schutzbund , which was led by Hermann Reschny . Hitler's plenipotentiary at the head of the Austrian NSDAP became the retired Colonel Friedrich Jankovic . In Austria's elections, the NSDAP remained insignificant: in the 1927 National Council election it received 0.76%, in 1930 it was 3%.

In the German Reich, the NSDAP was only one of several anti-Semitic and ethnic parties until the Reichstag elections in 1928 , but showed its prominent position in this spectrum by the Reichstag elections at the latest. In 1929, through joint agitation with the DNVP and the Stahlhelm, as part of the campaign against the Young Plan , the party gained wide-ranging attention.

The widely read newspapers of the major German publisher Alfred Hugenberg made the NSDAP and especially Adolf Hitler known throughout the Reich , although the campaign itself failed in December 1929 with only 15 percent approval. This and the following agitations and election campaigns were less financed by donations from big industry , which was deterred by “socialism” in the party name and preferred to support the DVP and DNVP (individual Nazi heavy industrialists such as Fritz Thyssen and Emil Kirdorf were exceptions). More important were donations from medium-sized industry, but above all the comparatively high membership fees (a financial instrument that the National Socialists had taken over from the SPD ) and the entrance fees to events with Hitler or Goebbels, for which between 50 pfennigs and two marks were required - the average The monthly wage of a worker was 180 marks, a student or an unemployed person with a family had to get by on around 80 marks.

Between 1925 and 1930, the party's membership rose from 27,000 to 130,000. The NSDAP took advantage of the global economic crisis and the resulting mass impoverishment, which supported its anti-capitalist , anti- liberal and above all anti-Semitic program against “international financial Jewry ” in the population. The Nazi salute was introduced within the party as early as 1926 and Hitler was designated as the Führer. After Horst Wessel's death in 1930, the Horst Wessel song also became the official party anthem of the NSDAP.

After the devastatingly poor result in the Reichstag elections in 1928, when the NSDAP had to be content with 2.6 percent of the vote, all party branches were instructed to reduce anti-Semitism in their propaganda , which was a deterrent to bourgeois circles in particular. From now on, the NSDAP focused on the street terror of the SA and other topics such as foreign policy , whereupon its share of the vote in the state elections in 1929 and 1930 rose to over 10 percent (for example in Saxony with 14.4 percent). This was also due to the presidential cabinets, which were not legitimized by elections . Young people and young men in particular joined the Hitler Youth and the SA. The National Socialist politicians gave up trying to win over the working class in particular, which led to the separation of a “left” wing, including Otto Strasser . However, the NSDAP received more and more support from farmers (the agricultural prices had fallen noticeably from 1928), craftsmen and retailers (fear of competition from “Jewish-run” department store groups) as well as from the ranks of students and civil servants (fear of the threat of “proletarianization “Of the academic bourgeoisie).

In this way, the NSDAP was able to use the global economic crisis , the effects of which were particularly noticeable in the German Reich, to gain a mass base in those voters who had previously voted for the DNVP or one of the other small national parties or who had been disappointed by the bourgeois parties ( DVP and DDP ) since Years ago had switched to the non-voter camp.

Election successes from 1930

The dissolution of the Reichstag by President Paul von Hindenburg in accordance with Article 25 of the constitution was therefore very convenient for the National Socialists. In the Reichstag elections on September 14, 1930, the NSDAP was the second largest party behind the SPD, with 18.3 percent of the votes cast. As early as January 1930, the NSDAP entered coalition governments in Thuringia (" Baum-Frick government ") and later that year in Braunschweig ( Küchenthal cabinet ). Despite the government participation, it was still perceived as an opposition to the "system". The propaganda of the NSDAP primarily focused on foreign policy and social issues. In her polemic against the Versailles Treaty , and especially against the Young Plan , as the cause of the misery in the world economic crisis were held up, she took both subjects. According to an instruction from Goebbels in 1928, party propaganda clearly held back with anti-Semitic polemics. Nevertheless, there were repeated pogrom-like incidents during the years of the rise of the NSDAP , such as the attacks on the Wertheim department store on the day the Reichstag opened in 1930 or the Kurfürstendamm riot on September 12, 1931 offer each social group specially tailored organizations and propaganda. In “naked populism ” ( Hans-Ulrich Wehler ), she promised every social group that it would exactly fulfill its wishes: for industrial workers, for example, there was the National Socialist company cell organization and the Hib campaign (“Inward into the factories”), for which there was a vogue the party considered socialist and also organized strikes. For smaller shopkeepers there was the National Socialist Fighting League for small and medium-sized businesses , which fought against the department stores and uniform price stores that were economically superior to the small specialty shops . In the country, the NSDAP took over the themes of the rural people's movement and concentrated on its blood-and-soil ideology and its goal of decoupling the German economy from the world market. The fact that the National Socialists were planning autarky was denied by Hitler to the big industrialists, for example in his speech to the Düsseldorf Industry Club . In relation to this clientele, for whom the Dr. Schacht and the Keppler circle gave several competing organizations within the NSDAP party apparatus, the propaganda emphasized the rejection of class struggles and democracy.

Integrating elements of these contradicting demands were the radical nationalism of the party and its Volksgemeinschaft ideology , which could be interpreted differently depending on the audience. It is true that both within the party and from outside, for example on the part of industry, which wanted to know how things were now with the “socialism” of the party program, repeated attempts by the NSDAP towards a concrete program of action for the time to be determined after a seizure of power. This was always flatly rejected by Hitler, who remained programmatically always cloudy and below the level of vague major demands such as the one for a “regeneration of our national body” avoided any political concretization: “As immutable [...] the laws of life itself are and thus those of our movement underlying idea, the struggle for fulfillment is so eternally fluid ”.

Thanks to its broadly differentiated propaganda, the NSDAP succeeded in winning over voters from all social groups and classes. The traditional Catholic milieu and that of the organized industrial workers proved to be less susceptible than the other milieus, but they did not remain immune to the Nazi temptation either. It was able to gain a disproportionately large number of followers among the old medium- sized businesses, among small tradespeople, shopkeepers and owners of craft businesses. From this finding, party researcher Jürgen W. Falter draws the conclusion that the NSDAP was a “people 's party with a middle class belly” that was able to integrate the sometimes diametrically divergent values and interests of all sections of the electorate.

In October 1931, at the insistence of Hitler and Alfred Hugenberg, the NSDAP and DNVP joined forces with other nationalist associations on the Harzburg Front as opponents of the Weimar Republic , but the alliance did not last long: just a few months later, they were fighting each other in the election campaign for the 1932 presidential election . Nevertheless, Hindenburg only succeeded in being re-elected as Reich President in the second ballot - Hitler came in second; The party achieved significant success in the state elections in Prussia , Bavaria , Wuerttemberg and other states and also became the strongest party in the Reichstag in the Reichstag elections on July 31, 1932. The party went through a serious crisis in 1932, which resulted in a significant decline in the votes in the Reichstag election on November 6, 1932 : The NSDAP remained the strongest party, but lost over four percentage points and two million voters. In addition, she got into serious financial problems as a result of the elaborate election campaigns of 1932. Reich Treasurer Franz Xaver Schwarz had to take desperate measures in January 1933: Party employees were dismissed or their salaries were cut, Gaue who were in arrears with the membership fees to be paid were threatened with forced administration . In an official party circular, Schwarz announced that “the existence of the headquarters” was in danger. The trend reversal succeeded in the state elections in Lippe on January 15, 1933 : The membership of the NSDAP increased to around 850,000. The electoral successes can also be traced back to the successful mobilization of non-voters, who no longer trusted the parties in power to overcome the global economic crisis.

Reich President Hindenburg harbored a deep personal aversion to the “ Bohemian Corporal ” Hitler, who, moreover, was not prepared to be satisfied with anything less than the Reich Chancellorship. Nonetheless, both Chancellor Heinrich Brüning and his successors von Papen and von Schleicher thought at least for a time of a right-wing coalition of the center, DNVP and NSDAP in order to bring about a reform of the Reich without the participation of the SPD. But this failed because of Hitler's insistence on the chancellorship; In addition, it was not possible to move at least parts of the National Socialists (and the German Nationalists) to this coalition or to a " cross front " of trade unions and left-wing National Socialists. The downside of the attempts to involve Hitler was that Brüning did not denounce the NSDAP as a subversive and anti-constitutional party and fight it accordingly.

At the beginning of 1933, Chancellor von Schleicher's “Querfront” idea had failed. This advocated continued government with the elimination of the Reichstag, which would meet again at the end of January and would certainly overthrow the government. In this situation Franz von Papen succeeded in persuading the Reich President to form an NSDAP-DNVP coalition under a Chancellor Hitler. Von Papen believed he could “tame” Hitler. On January 30, 1933, this led to the formally legal “transfer of power” (later referred to as the “ seizure of power ” by the National Socialists).

The election results of the NSDAP in the Reichstag elections from 1930 to 1933

| Constituency | March 5, 1933 | November 6, 1932 | July 31, 1932 | September 14, 1930 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| East Hanover | 54.3% | 42.9% | 49.5% | 20.6% |

| South Hanover-Braunschweig | 48.7% | 40.6% | 46.1% | 24.3% |

| Hamburg | 38.9% | 27.2% | 33.7% | 19.2% |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 53.2% | 45.7% | 51.0% | 27.0% |

| Weser-Ems | 41.4% | 31.9% | 38.4% | 20.5% |

| Westphalia North | 34.9% | 22.3% | 25.7% | 12.2% |

| Westphalia-South | 33.8% | 24.8% | 27.2% | 13.9% |

| Düsseldorf-East | 37.4% | 27.0% | 31.6% | 17.0% |

| Düsseldorf-West | 35.2% | 24.2% | 27.0% | 16.8% |

| Cologne-Aachen | 30.1% | 17.4% | 20.2% | 14.5% |

| Koblenz-Trier | 38.4% | 26.1% | 28.8% | 14.9% |

| Palatinate | 46.5% | 42.6% | 43.7% | 22.8% |

| Hessen-Darmstadt | 47.4% | 40.2% | 43.1% | 18.5% |

| Hessen-Nassau | 49.4% | 41.2% | 43.6% | 20.8% |

| Thuringia | 47.2% | 37.1% | 43.4% | 19.3% |

| Francs | 45.7% | 36.4% | 39.9% | 20.5% |

| Lower Bavaria | 39.2% | 18.5% | 20.4% | 12.0% |

| Upper Bavaria-Swabia | 40.9% | 24.6% | 27.1% | 16.3% |

| Württemberg | 42.0% | 26.2% | 30.3% | 9.4% |

| to bathe | 45.4% | 34.1% | 36.9% | 19.2% |

| East Prussia | 56.5% | 39.7% | 47.1% | 22.5% |

| Pomerania | 56.3% | 43.1% | 48.0% | 24.3% |

| Mecklenburg | 48.0% | 37.0% | 44.8% | 20.1% |

| Opole | 43.2% | 26.8% | 29.2% | 9.5% |

| Wroclaw | 50.2% | 40.4% | 43.5% | 24.2% |

| Liegnitz | 54.0% | 42.1% | 48.0% | 20.9% |

| Frankfurt Oder | 55.2% | 42.6% | 48.1% | 22.7% |

| Berlin | 31.3% | 22.5% | 24.6% | 12.8% |

| Potsdam I. | 44.4% | 34.1% | 38.2% | 18.8% |

| Potsdam II | 38.2% | 29.1% | 33.0% | 16.7% |

| Leipzig | 40.0% | 31.0% | 36.1% | 14.0% |

| Dresden-Bautzen | 43.6% | 34.0% | 39.3% | 16.1% |

| Chemnitz-Zwickau | 50.0% | 43.4% | 47.0% | 23.8% |

| Merseburg | 46.6% | 34.5% | 42.6% | 20.5% |

| Magdeburg | 47.3% | 39.0% | 43.8% | 19.5% |

| Deutsches Reich | 43.9% | 33.1% | 37.4% | 18.3% |

After the seizure of power in 1933

Support from business and industry

In the final phase of the Weimar Republic, the major entrepreneurs only sporadically contributed to the financing of the NSDAP. Exceptions were Fritz Thyssen , Albert Vögler , who in November 1932 had participated in a list of signatures of important entrepreneurs against Hitler, and Emil Kirdorf , who turned back to the DNVP in 1928 . In 1933 , Hermann Röchling supported the NSDAP in the Saar region . Since February 1933, industrial donations have flowed in abundantly. They were institutionalized as an Adolf Hitler donation to the German economy and soon took on the character of a compulsory levy. In fact, as they hoped, the industrialists received various benefits from their financial support. In order to make the economy fit for war and the armed forces ready for action , not only the armaments industry was strongly promoted. In corporations like IG Farben , Buna and gasoline were produced synthetically. The clothing industry profited from the mass uniformity of society. However, other industries soon suffered from the deprivation of raw materials important for armament.

Party congresses

Until 1938 the NSDAP celebrated its annual party congresses in Nuremberg. These Nazi party rallies were memorably staged in huge procession by party functionaries with subsequent oaths of loyalty as well as evening torchlight procession and light domes as a symbolic fusion of man and the force of nature. Albert Speer's light dome was considered a sublime visual staging of the collective and was the projection of 150 flak spotlights in the sky. The media reported in detail on the meticulously planned party congresses. In addition, Leni Riefenstahl's Nazi party rally films, The Victory of Faith and Triumph of Will, exaggerated the events cinematically. They conveyed the impression of the national community proclaimed by the National Socialists and the associated conformity. After the death of Paul von Hindenburg, the Wehrmacht first took part in a party congress in 1934 and was sworn to Hitler, not the people.

Role in the Nazi state

Hitler took part in the first months of 1933 on the basis of his government, a coalition of NSDAP and DNVP, by the Reich President Paul von Hindenburg handed over power . In the last election held under the law of the Weimar Republic on March 5, 1933, whose election campaign was already marked by bans on other parties and reprisals by political opponents through terror and propaganda, the NSDAP did not receive an absolute majority of around 44 percent . However, with the votes of all other parties except the SPD and KPD (see Day of Potsdam ), the National Socialists managed to obtain the necessary two-thirds majority in the Reichstag for the passage of the Enabling Act on March 24th, which transferred power to Hitler by eliminating parliament and Finally it was used to ban all parties except the NSDAP.

In Austria, where the Christian Social Federal Government used a so-called “ parliamentary self- elimination” to seize power as the Fatherland Front and establish authoritarian rule, the strengthened NSDAP was banned in June 1933 after two National Socialists had attacked with a hand grenade. Subsequently, NSDAP supporters infiltrated legal, actually apolitical organizations, while others went to Germany, where Austrian SA members set up the Austrian Legion . Until the “Anschluss” in 1938, Austria had naturalized 11,000 so-called “illegals”. During the same period, 169 people died in waves of terror by the illegal NSDAP against representatives of the state and other political opponents, especially in the failed July coup in 1934, in which the National Socialists also murdered Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss .

In National Socialist Germany, a one-party state was formed, which was also legally anchored on December 1, 1933 by the “ Law to Safeguard the Unity of Party and State ”. The NSDAP was thus a corporation under public law with its own jurisdiction over its members. By April the party had 2.5 million members, most of whom were civil servants and employees, after the NSDAP occupied key positions in the state, organizations, factories and authorities. From 1933, the swastika, introduced as a party symbol in 1920, became ubiquitous in everyday life. In the course of the Nuremberg Laws passed at the Nazi Party Congress in 1935 , the symbol became the emblem of the German Reich.

During the time of National Socialism , the NSDAP hardly emerged through its own activities. Research has given various causes for this. The journalist Heinz Höhne assumes that it was paralyzed by the division of power: Although Rudolf Hess received formally unrestricted power over the party on April 21, 1933 when he was appointed Deputy Leader, Hitler "forgot" subordinate to him also their Reich Organization Leader Robert Ley , who had the powerful corps of political leaders of the NSDAP under himself. This had resulted in numerous quarrels and rivalries over competencies, which were typical of the National Socialist polycracy , and thus paralyzed the actual power of the party. According to the historian Wolfgang Benz , the position of the NSDAP was only "apparently institutionalized" after the seizure of power. In fact, she performed "subsidiary functions in the enforcement of the leadership state and in maintaining power". The fact that the party leadership remained in Munich and thus clearly separated from the actual centers of power in the Reich capital Berlin is symptomatic of this. The Berlin historian Henning Köhler believes that the NSDAP was exclusively an "agitation and voting machine" and only one of its sub-organizations actually reached the base effectively: the Reich Propaganda Leadership under Goebbels. From the moment there were no more election campaigns, the party leadership limited itself to collecting membership fees and settling disputes between its officials. She did not play an active role, for example, in the distribution of the numerous career positions that had to be filled in the course of the synchronization . Rather, there was a Social Darwinist struggle of party functionaries against one another.

After 1933 there was an enormous fluctuation in the functionary post. Between 1933 and 1935, 40,153 party functionaries left who had joined the NSDAP before January 30, 1933. This corresponds to a fluctuation of almost 20 percent. During this time, 53.1 percent of the Kreisleiter and 43.8 percent of the Ortsgruppenleiter positions were filled.

From June 30 to July 2, 1934, in the course of the alleged suppression of the so-called Röhm Putsch, the SA leadership, including its chief of staff, Ernst Röhm, was murdered on Hitler's orders. In fact, there had been no coup preparations whatsoever on the part of the SA. Rather, it cemented Hitler's absolute power over the party, which since then has been merely an instrument of his personal rule.

After the SA was violently disempowered, Hitler no longer had any serious opponents within the party. The power he now possessed in the party, which was structured according to the leader principle , was to be maintained until the end of the Second World War.

The party "inextricably linked to the state" became the "bearer of the German state idea" and was responsible for the "Führerauslese", ie the filling of key state positions. During the Second World War it was up to the NSDAP to decide who was now indispensable and thus freed from active military service at the front. As a rule, only party officials received this status. The material preference given to the full-time “ party bosses ” as well as their frequent incompetence and corruption contributed to the fact that the reputation of the NSDAP in society quickly waned at the beginning of the war. The NSDAP was mainly occupied with organizational and administrative tasks in air raid protection and evacuation from cities, with camps for forced labor , with collecting campaigns or harvesting aids by the Hitler Youth. Towards the end of the war she was also supposed to set up the Volkssturm .

Ban on party

With the collapse of the Nazi state , the party organization ceased its activities. On October 10, 1945, the NSDAP with all its branches and affiliated associations was banned by the Control Council Act No. 2 of the Allied Control Council . The party was declared a "criminal organization" in the Nuremberg trials in 1946. The NSDAP or a start-up is also prohibited in Austria (prohibition of re-employment ).

In 1949 the Socialist Reich Party (SRP) was founded, often referred to as the successor to the NSDAP, and banned by the Federal Constitutional Court in 1952 .

Structure of the NSDAP

The National Socialist German Workers' Party was structured like a pyramid. At the head was the chairman, initially Karl Harrer and then Anton Drexler (February 24, 1920 to July 29, 1921), who then became honorary chairman, and then Adolf Hitler (July 29, 1921 to April 30, 1945). He was endowed with absolute power and had full authority. All other party offices were subordinate to his position and had to follow his instructions. Under the chairman Hitler, the Reichsleiter were in the “ Chancellery of the Führer ” established in 1934 , the number of which was gradually increased to 18. In the Third Reich they had similarly great power as Reich Ministers , which in the polycraticism of the Nazi state led to competitive struggles that Hitler wanted.

The staff of the deputy leader , a central leadership body of the NSDAP, was involved in all major decisions in the party and state apparatus. The office, based in Munich, was subordinate to Rudolf Hess until it was personally subordinate to Hitler on May 12, 1941 and was continued under the new name "Party Chancellery" by long-time chief of staff, Martin Bormann .

The party had the following sub-organizations, some of which had a considerable life of their own with their own political ideas:

- Association of German Girls (BDM)

- Hitler Youth (HJ)

- National Socialist German Lecturer Association (NSDDB) - (only from July 1944)

- NS-German Student Union (NSDStB)

- National Socialist Women's Association (NSF)

- National Socialist Motor Corps (NSKK)

- NSDAP / AO - foreign organization

- Schutzstaffel ( General SS and Waffen SS )

- Sturmabteilung (SA)

Some affiliated organizations had their own legal personality and assets. They were looked after by the party, such as:

- Reich Federation of German Officials

- German Labor Front (DAF)

- National Socialist German Medical Association (NSDÄB)

- National Socialist Air Corps (NSFK)

- National Socialist Legal Guardian Association (NSRB)

- Nazi war victims' pension (NSKOV)

- National Socialist Teachers Association (NSLB)

- National Socialist People's Welfare (NSV)

- Reich Labor Service (RAD)

With the organizations and affiliated associations, the NSDAP was able to organizationally penetrate society to a large extent and control and indoctrinate the population both at work and in their leisure time. The denazification questionnaire of the military government , edition 1946, asked about the membership in 95 organizations from the circle of the NSDAP. The social control was carried out in particular by block and cell guards and by local NSDAP groups , as they had a veto right in the promotion of civil servants, for candidates for the public service or for applicants with regard to social support and training assistance. The latter was decisive because the NSDAP did not establish a statutory health insurance provider until 1941 . Before that, the workers had to turn to charities because otherwise the masses could not afford a doctor's visit.

The Political Organization (PO) of the NSDAP was divided into districts , districts, local groups, cells and blocks . As the smallest organizational unit, a block consisted of between 40 and 60 households.

Members

Membership numbers and card index

Information on the development of the number of members from 1919:

| date | Members |

|---|---|

| Late 1919 | 64 |

| Late 1920 | 3000 |

| Late 1921 | 6000 |

| November 23, 1923 | 55,787 |

| Late 1925 | 27,117 |

| Late 1926 | 49,523 |

| Late 1927 | 72,590 |

| Late 1928 | 108,717 |

| Late 1929 | 176.426 |

| Late 1930 | 389,000 |

| Late 1931 | 806.294 |

| April 1932 | 1,000,000 |

| Late 1932 | 1,200,000 |

| Late 1933 | 3,900,000 |

| 1939 | 5,300,000 |

| May 1943 | 7,700,000 |

At the time of the “seizure of power”, the NSDAP had 849,009 members (party statistics). In 1943, 11% of the population were party members. At first (and again and again) an attempt was made to keep the “ March fallen ” (opportunists who confessed to the NSDAP after the seizure of power, especially after the election victory in March 1933) from the party. To this end, a comprehensive ban on membership was imposed in 1933 (see main article ban on membership of the NSDAP ). However, the need for new members was always so great that such measures could not be sustained for long, especially since they were also used to build a “transmission belt” into society.

There was a central NSDAP file ("Reichskartei", 50 tons of cards) and a "Gaukartei". Parts of the files were destroyed in 1945; ninety percent of the party members remained known. A few months after the beginning of the occupation, the potential use of the files in denazification was recognized; they were brought to the Berlin Document Center . In 1994 the index cards were transferred to the holdings of the Federal Archives .

NSDAP membership even without consent?

The prerequisite for membership in the NSDAP was a hand-signed application for membership. For those born in 1926 and 1927, the responsible Reich Treasurer decided on January 7, 1944, that the admission age should be reduced from 18 to 17 years. A condition for joining the party was a multi-year membership in the Hitler Youth. Internal correspondence received from the NSDAP proves that unsigned applications for membership were also returned unprocessed in August 1944. Up to two years could elapse between the application for admission and the handing over of the membership card or the membership book; Only then did the membership become legally binding.

NSDAP membership cards are available in the Federal Archives for a number of members of the “ Flakhelfergeneration ” such as the composer Hans Werner Henze , the cabaret artist Dieter Hildebrandt , the politicians Hans-Dietrich Genscher , Erhard Eppler and Horst Ehmke as well as the authors Martin Walser and Siegfried Lenz . With the exception of Eppler, however, all those affected deny having knowingly been a member of the NSDAP.

In addition, the historian Norbert Frei remarked that he considered “unwitting memberships to be possible in principle”. The Freiburg historian Ulrich Herbert explained about the party entries towards the end of the war: "The intention to persuade as many - or all - members of a Hitler Youth unit to join the NSDAP as possible is clearly recognizable." It is quite possible that individual Nazi leaders wanted to report high admission numbers to prove their efficiency even without the corresponding signatures; for example on “Führer’s birthday”. However, there is no evidence for party admission without the knowledge of those concerned, while strict compliance with the admission guidelines is well documented in 1944 by lists of admission slips. As a result, even in the case of collective admissions, for example by Hitler Youth, admission forms that were not personally signed were sent back to the respective Gauleitung by the Nazi Reich Treasurer; the party did not take place. The names of Ehmke and Henze appear on collection lists with several hundred applications for membership, of which the unsigned applications were returned unprocessed (Ehmke and Henze's applications were not objected to).

The historian Michael Buddrus from the Institute for Contemporary History therefore comes to the conclusion in an expert report for Das Internationale Germanistenlexikon 1800–1950 that acceptance into the NSDAP without a signature is unlikely. According to a preliminary assessment by the Federal Archives, the relevant party regulations were strictly adhered to during the war. Buddrus sees in the claims of automatic admission into the NSDAP "legends which had their starting point in relief efforts in the immediate post-war period and which, through frequent colportage , advanced to a popular" common property "which, however, has nothing to do with historical reality."

Designations

A member of this party, often also supporters appearing for them, were and are called “National Socialist” or “ Nazi ” for short or “Party member” or “Pg” for short. The party itself was usually referred to in everyday language by the letters NSDAP. Higher party functionaries in public offices were called “batches” based on terms from the military . Due to the light brown uniforms Party nationalized in the vernacular , the term " golden pheasant " one.

Awards

See also

- Austrian Legion

- Sudeten German Home Front (SHF; Konrad Henlein ; October 1, 1933–1945)

- NS hierarchy

- List of important politicians and officials of the NSDAP

- List of former NSDAP members who were politically active after May 1945

- List of NSDAP party member numbers

literature

- Christine Arbogast: ruling bodies of the Württemberg NSDAP. Function, social profile and life paths of a regional Nazi elite 1920–1960 (= National Socialism and the post-war period in southwest Germany. Volume 7). Oldenbourg, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-486-56316-5 (Diss. Univ. Tübingen 1996/1997, DNB 951148168 , 295 pages; 23 cm).

- Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): How did you become a party member? The NSDAP and its members (= The time of National Socialism. Volume 18068). Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-596-18068-4 .

- Wilfried Böhnke: The NSDAP in the Ruhr area. 1920–1933 (= publication series of the research institute of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Volume 106). Verlag Neue Gesellschaft, Bonn-Bad Godesberg 1974, ISBN 3-87831-166-4 (Diss. Univ. Marburg, Philosophical Faculty, 1970, 239 pages; 24 cm).

- Thomas Childers: The Nazi Voter. The Social Foundations of Fascism in Germany, 1919–1933. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill NC 1983, ISBN 0-8078-4147-1 .

- Peter Diehl-Thiele: Party and State in the Third Reich. Investigation of the relationship between the NSDAP and general internal state administration 1933–1945 (= Munich Studies on Politics. Volume 9). Beck, Munich 1969, DNB 456453326 (Diss. Univ. Munich 1969, XIV, 269 pages, 8).

- Jürgen W. Falter : Hitler's voters. Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-35232-4 .

- Jürgen W. Falter (Ed.): Young fighters, old opportunists. The members of the NSDAP 1919–1945 . Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2016, ISBN 978-3-593-50614-2 .

- Jürgen W. Falter: Hitler's party comrades. The members of the NSDAP 1919–1945. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2020, ISBN 978-3-593-51180-1 .

- Johnpeter Horst Grill: The Nazi Movement in Baden, 1920-1945. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill NC 1983, ISBN 0-8078-1472-5 .

- Wolfgang Horn: The march for the seizure of power. The NSDAP until 1933 (= Athenaeum Droste pocket books 7234 history ). Unchanged reprint of the work first published in 1972. Athenaeum publishing house, among others, Königstein / Ts. [u. a.] 1980, ISBN 3-7610-7234-1 .

- Peter Hüttenberger : The Gauleiter. Study on the change in the power structure in the NSDAP (= series of the quarterly books for contemporary history. No. 19, ISSN 0506-9408 ). DVA, Stuttgart 1969 (Diss. Univ. Bonn, 1966).

- Michael H. Kater : The Nazi Party. A Social Profile of Members and Leaders, 1919-1945. Blackwell, Oxford 1983, ISBN 0-631-13313-5 .

- Sven Felix Kellerhoff : The NSDAP. A party and its members. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2017, ISBN 978-3-608-98103-2 .

- Udo Kissenkoetter : Gregor Straßer and the NSDAP (= series of the quarterly books for contemporary history. Vol. 37). Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1978, ISBN 3-421-01881-2 (also: Düsseldorf, Univ., Diss., 1975).

- Joachim Lilla : The deputy Gauleiter and the representation of the Gauleiter of the NSDAP in the “Third Reich” (= materials from the Federal Archives. H. 13). Wirtschaftsverlag NW, Bremerhaven 2003, ISBN 3-86509-020-6 .

- Peter Longerich : Hitler's deputy. Leadership of the party and control of the state apparatus by the Hess staff and the party chancellery Bormann. Saur, Munich [u. a.] 1992, ISBN 3-598-11081-2 .

- Werner Maser : The storm on the republic. Early history of the NSDAP (= Ullstein-Buch. No. 34041 Ullstein-Sachbuch ). Unabridged edition. Ullstein, Frankfurt am Main [a. a.] 1981, ISBN 3-548-34041-5 .

- Horst Matzerath , Henry A. Turner : The self-financing of the NSDAP 1930-1932. In: History and Society . Vol. 3, 1977, pp. 59-92, ( digitized version against costly membership at jstor.org ).

- Donald M. McKale: The Nazi Party Courts. Hitler's Management of Conflict in his Movement, 1921–1945. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence [et. a.] 1974, ISBN 0-7006-0122-8 .

- Jeremy Noakes: The Nazi Party in Lower Saxony. 1921-1933. Oxford University Press, London [u. a.] 1971.

- Armin Nolzen : The NSDAP, the war and German society. In: Military History Research Office (ed.): The German Reich and the Second World War . Volume 9: Jörg Echternkamp (Ed.): The German War Society. 1939 to 1945. Half Volume 1: Politicization, Destruction, Survival. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart [u. a.] 2004, ISBN 3-421-06236-6 , pp. 99-193.

- Armin Nolzen: Functionaries in a fascist party. The district leaders of the NSDAP, 1932/33 to 1944/45. In: Till Kössler, Helke Stadtland (ed.): From the functioning of the functionaries. Political representation of interests and social integration in Germany after 1933 (= publications of the Institute for Social Movements. Series A: Representations. Vol. 30). Klartext-Verlag, Essen 2004, ISBN 3-89861-266-X , pp. 37-75.

- Armin Nolzen: Charismatic Legitimation and Bureaucratic Rule: The NSDAP in the Third Reich, 1933-1945. In: German History. Vol. 23, No. 4, 2005, pp. 494-518, doi : 10.1093 / 0266355405gh355oa (currently unavailable) .

- Dietrich Orlow: The History of the Nazi Party. 2 volumes (Vol. 1: 1919-1933. Vol. 2: 1933-1945. ). University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh PA 1969-1973, ISBN 0-8229-3183-4 (Vol. 1), ISBN 0-8229-3253-9 (Vol. 2).

- Kurt Pätzold , Manfred Weißbecker : History of the NSDAP. 1920-1945. Special edition. PapyRossa-Verlag, Cologne 2002, ISBN 3-89438-260-0 .

- Michael Rademacher: Handbook of the NSDAP Gaue, 1928–1945. The officials of the NSDAP and their organizations at Gau and district level in Germany and Austria as well as in the Reichsgau Gdansk-West Prussia, Sudetenland and Wartheland. M. Rademacher et al., Vechta [et al. a.] 2000, ISBN 3-8311-0216-3 .

- Carl-Wilhelm Reibel: The foundation of the dictatorship. The NSDAP local groups 1932–1945. Schöningh, Paderborn [a. a.] 2002, ISBN 3-506-77528-6 (Diss. Univ. Frankfurt am Main 2000).

- Mathias Rösch : The Munich NSDAP 1925–1933. An investigation into the internal structure of the NSDAP in the Weimar Republic (= studies on contemporary history. Vol. 63). Oldenbourg, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-56670-9 (also: Munich, Univ., Diss., 1998) ( full text available digitally ).

- Detlef Schmiechen-Ackermann : The "block warden". The lower party functionaries in the National Socialist terror and surveillance apparatus. In: Quarterly Books for Contemporary History . Vol. 48, H. 4, 2000, pp. 575-602, digital version (PDF; 8 MB) .

- Albrecht Tyrell (ed.): Führer befiehl ... personal testimonies from the "fighting time" of the NSDAP. Documentation and analysis. Droste, Düsseldorf 1969 (licensed edition. Gondrom, Bindlach 1991, ISBN 3-8112-0694-X ).

- Albrecht Tyrell: From Drummer to Leader. The change in Hitler's self-image between 1919 and 1924 and the development of the NSDAP. Fink, Munich 1975, DNB 750241225 (Diss. Univ. Bonn, Philosophical Faculty, 1975, 296 pages; 23 cm digitized from the University of Michigan on November 15, 2006 ).

Web links

- LeMO: The NSDAP from 1920 to 1933

- LeMO: The NSDAP from 1933 to 1945

- The future needs memories: Article about the NSDAP

- Document archive: the 25-point program of the NSDAP

- Overview maps of the NSDAP's share of votes in the Reichstag elections in the individual constituencies during the Weimar Republic

- Michael Mayer, University of Munich: "NSDAP and anti-Semitism 1919–1933"

- Federal Archives: PG - On the membership system of the NSDAP

- digitalcollections.hoover.org: Theodore Fred Abel papers (over 600 texts from the 1930s by NSDAP members about their life stories, collected by the American sociologist Theodore Abel )

Individual evidence

- ↑ John Toland: Adolf Hitler , Volume 1. Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1977, ISBN 3-404-61063-6 , p. 139.

- ↑ Uta Jungcurt: Pan-German extremism in the Weimar Republic. Thinking and acting of an influential minority. De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2016, p. 150.

- ^ Gerhard Jagschitz : The National Socialist Party. In Emmerich Tálos, Herbert Dachs and others. (Ed.): Handbook of the Austrian political system. First Republic 1918–1933. Manz, Vienna 1995, pp. 231–244.

- ↑ Bernd Beutl: Caesuras and structures of National Socialism in the First Republic. In: Wolfgang Duchkowitsch (Ed.): The Austrian Nazi Press 1918–1933. Literas, Vienna 2001, pp. 20–47, here p. 27.

- ↑ Christian Hartmann (Ed.): Adolf Hitler: Reden, Schriften, Anordnung. Vol. 5., From the election of the Reich President to the seizure of power April 1932 – January 1993. Part 2., October 1932 – January 1933 . Saur, Munich 1998, p. 285, fn. 6.

- ^ Wolfgang Benz : National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) . In: the same, Hermann Weiss and Hermann Graml (eds.): Encyclopedia of National Socialism . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1997, p. 602.

- ↑ Also on the following: Albrecht Tyrell (ed.): Führer befiehl ... self-testimonies from the "fighting time" of the NSDAP . Gondrom Verlag, Bindlach 1991, pp. 68-72.

- ^ Letter from Hitler to Albert Stier dated June 23, 1924. In: Albrecht Tyrell (Ed.): Führer befiehl ... Self-testimonies from the "fighting time" of the NSDAP . Gondrom Verlag, Bindlach 1991, p. 78.

- ↑ Jakob Wetzel: Brown occupation of the garden city , Süddeutsche Zeitung , April 29, 2015, accessed on September 30, 2020.

- ↑ See title page of the first edition in the Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

- ↑ Wolfgang Wippermann : Mein Kampf. In: Wolfgang Benz, Hermann Weiß and Hermann Graml (eds.): Encyclopedia of National Socialism. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1997, p. 580 f .; Barbara Zehnpfennig : Adolf Hitler: "Mein Kampf". Weltanschauung and program - study commentary. Wilhelm Fink Verlag, Munich 2011, pp. 45–56 u.ö.

- ^ Gerhard Jagschitz: On the structure of the NSDAP in Austria before the July coup 1934. In: Ludwig Jedlicka, Rudolf Neck: The year 1934: July 25th. Minutes of the symposium in Vienna on October 8, 1974. Vienna 1975, pp. 9–20, here p. 9.

- ^ John T. Lauridsen: Nazism and the Radical Right in Austria, 1918-1934. The Royal Library / Tuscalunum Press, Copenhagen 2007, p. 313.

- ↑ Bernd Beutl: Caesuras and structures of National Socialism in the First Republic. In: Wolfgang Duchkowitsch: The Austrian Nazi Press 1918-1933. Literas, Vienna 2001, pp. 20–47, here p. 34.

- ↑ Götz Aly : Why the Germans? Why the Jews? Equality, envy and racial hatred , S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2011, p. 252.

- ↑ Philipp Heyde, The End of Reparations. Germany, France and the Youngplan 1929-1932 , Schöningh, Paderborn 1998, p. 91, 109 fu ö.

- ↑ Gerhard Paul , Uprising of Pictures. The Nazi propaganda before 1933 , JHW Dietz Nachf., Bonn 1990, pp. 90–94.

- ↑ Oded Heilbronner, Where Did Nazi Anti-Semitism Disappear to? Anti-Semitic Propaganda and Ideology of the Nazi Party, 1929–1933. A Historiographic Study , Yad Vashem Studies, 21 (1991), pp. 263-286.

- ↑ Andreas Wirsching , From World War I to Civil War? Political extremism in Germany and France 1918–1933 / 39. Berlin and Paris in comparison , Oldenbourg, Munich 1999, p. 463.

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler, German history of society . Vol. 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states 1914–1949 . 2., through Ed., CH Beck, Munich 2003, p. 568 f.

- ^ Daniela Münkel , National Socialist Agricultural Policy and Farmer's Day , Campus Verlag, Munich 1996, pp. 86–84.

- ↑ Albrecht Tyrell, Führer befiehl… testimonials from the 'fighting time' of the NSDAP , Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1969, p. 271 ff .; the quotations from Hitler's preface to the PO regulations. of the NSDAP of July 15, 1932, ibid., p. 304.

- ↑ Jürgen W. Falter, Hitler's voters , CH Beck, Munich 1991, pp. 365–374, quotation p. 372.

- ↑ Jürgen W. Falter: Hitler's voters. CH Beck, Munich 1991, p. 37.

- ↑ Wolfram Pyta and Rainer Orth : There is no alternative. How a Reich Chancellor Hitler could have been prevented . In: Historische Zeitschrift 312, Issue 2 (2021), pp. 400–444, here p. 431.

- ↑ 1918–33: The National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) , LeMO , accessed on July 8, 2012.

- ^ Peter Longerich: Keyword January 30, 1933, Heyne Verlag, Munich. 1992. pp. 64-65.

- ↑ Wolfgang Meixner : 11,000 expatriated illegal Nazis from Austria between 1933 and 1938. In: Report on the 24th Austrian Historians' Day in Innsbruck. Association of Austrian History Societies, Innsbruck 2006, pp. 601–607.

- ↑ Wolfgang Neugebauer, Helmut Wohnout et al .: Victims of the terror of the Nazi movement in Austria 1933 - 1938. Documentation archive of the Austrian resistance, 2002.

- ↑ Heinz Höhne: "Give me four years". Hitler and the beginnings of the Third Reich . Ullstein, Berlin 1996, p. 131 f.

- ^ Wolfgang Benz: National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP). In: the same, Hermann Graml and Hermann Weiß (eds.): Encyclopedia of National Socialism . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1997, p. 603.

- ↑ Henning Köhler: Germany on the way to itself. A history of the century . Hohenheim-Verlag, Stuttgart 2002, p. 290 f.

- ^ Party statistics of the NSDAP. Status: January 1, 1935 (excluding Saarland), ed. from the head of the Reich organization of the NSDAP. 4 volumes, Munich 1935–1939, here: Vol. II, pp. 290 and 295.

- ↑ BVerfGE 2, 1 : “On November 19, 1951, the Federal Government submitted the application announced in the decision of May 4, 1951 to the Federal Constitutional Court. She claims that the internal order of the SRP does not correspond to democratic principles, but is based on the leader principle. The SRP is a successor organization to the NSDAP; they pursue the same or at least similar goals and go out to do away with the free democratic basic order. "

- ↑ BVerfGE 2, 1

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz: National Socialism. In: the same (ed.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus . Volume 3: Terms, ideologies, theories. De Gruyter Saur, Berlin / Munich / Boston 2008, ISBN 978-3-598-24074-4 , p. 229 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Bibliographisches Institut Leipzig: Look it up! Facts worth knowing from all areas. 1st edition, Leipzig 1938.

- ↑ Michael Grüttner: The Third Reich. 1933–1939 (= Gebhardt. Handbook of German History , Volume 19), Stuttgart 2014, p. 101.

- ↑ Ulrich Raulff , in: Süddeutsche Zeitung of September 25, 2004.

- ↑ Matthias Gafke: Goebbels' nausea FAZ.net, December 8, 2016th

- ↑ Uniforms of the Greater German Reich , Moritz Ruhl Verlag, 1943, p. 72.

- ↑ Federal Archives: On the NSDAP admission procedure ( Memento from May 18, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Order 1/44 of the Reich Treasury Master in the facsimile at the Federal Archives under: On the NSDAP admission procedure ( Memento from May 18, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Letter from the admission office dated August 18, 1944 to the Gau treasurer in Düsseldorf in a facsimile at the Federal Archives under: On the NSDAP admission procedure ( Memento from May 18, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Interview with Norbert Frei in the weekly newspaper “ Die Zeit ” at Presseportal .

- ↑ Südkurier No. 150 of July 3, 2007, p. 11.

- ↑ Malte Herwig: Hopelessly in between . In: Der Spiegel . No. 29 , 2007 ( online - July 16, 2007 ).

- ↑ The stupid major of the adapted , in: Die Weltwoche , February 11, 2009.

- ↑ Michael Buddrus: Was it possible to become a member of the NSDAP without doing anything yourself ? Expert opinion of the Institute for Contemporary History Munich-Berlin for the International Lexicon of Germanists 1800-1950 . Also reprinted in Geschichte der Germanistik 23/24, 2003, pp. 21–26 ( online ).

- ↑ Walser, Lenz and Hildebrandt. Unknowingly in the NSDAP. Süddeutsche Zeitung of June 30, 2007.

- ↑ Malte Herwig: betrayed and given away? Dealing with the Nazi past of artists in Germany , in: Weltwoche , 25 February 2009.

-

↑ Frank Staudenmayer: Nazi Documentation Center - About Nuremberg's Nazi Past ( Memento from September 16, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

Cf. also contemporary: Edelweißpiraten about Nazi leaders and others. ( Memento of October 23, 2007 in the Internet Archive ); Bernhard Gotto: National Socialist Communal Policy , p. 120 ff.

Federal Archives: PG - On the membership system of the NSDAP ( Memento from January 8, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) - ↑ Beate Meyer: "Goldfasane" and "Nazissen". The NSDAP in the formerly "red" district of Hamburg-Eimsbüttel. Edited by the Morgenland Gallery, Hamburg 2002.