Enabling Act

With an Enabling Act which grants Parliament the government extraordinary powers. In the German history there have been a number of empowerment laws since 1914th They contradicted the Weimar Constitution , which did not provide for such a transfer of rights from one organ to another, but the constitutional doctrine of the time accepted these laws; they came about in times of crisis and with a two-thirds majority . The same majority would have been necessary for a constitutional amendment . There was talk of a permissible breach of the constitution .

By far the best-known enabling law is the law to remedy the misery of people and empire . On March 23, 1933, this was the subject of heated debates, until the Reichstag , elected on March 5, adopted the law introduced by the Hitler government in a roll-call vote with the votes of the government coalition of the NSDAP and DNVP as well as the Zentrum , Bayerischer Volkspartei (BVP) and German State Party . It came into force on the following day, March 24, 1933, when it was promulgated. The Enabling Act did not serve to make the republic capable of acting, but - on the contrary - to abolish it. Together with the Reichstag Fire Ordinance , it is considered the main legal basis of the National Socialist dictatorship because it broke the principle of separation of powers, which is the fundamental basis of the material constitutional state .

The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany of 1949 regulated more clearly than the Weimar Constitution which authorizations are allowed. The Basic Law enables a somewhat comparable transfer of rights of a constitutional body only in the event of a legislative emergency . In addition, the Basic Law expressly forbids deviating from the constitution, even if a majority would vote in favor of it. The constitution can only be changed by expressly changing the text of the constitution.

Special feature of the enabling laws

In principle, authorizations in law, including in public law , are a common phenomenon. The most important legal norms are laid down in laws. Laws can only be passed by the legislature, usually parliament. Likewise, only parliament can amend or repeal a law. The constitution sometimes stipulates that a legal matter can only be regulated by law. In the hierarchy of norms , the ordinances are below the constitution and the laws. Regulations are issued, amended or repealed by the government. A regulation must not contradict the law, otherwise it is ineffective.

The work on a law often takes a long time, maybe several years. A regulation, on the other hand, can be amended relatively quickly by the government. That is why many laws do not regulate matters down to the smallest detail, but instead give the government the task of issuing an ordinance on detailed questions. The government can then quickly adapt details to current developments in the future. The law remains the framework on which the ordinance is based. The parliament authorizes the government through the law to issue such an ordinance ( authority to issue ordinances ).

Whenever one speaks of enabling laws in German history, then special authorizations are meant, or more precisely: the authorizations for special ordinances. In the period from 1914 to 1933 and 1945, there were enabling laws that allowed the government to issue ordinances with the force of law. These statutory ordinances were just as high up in the hierarchy of norms as laws, so they could only be amended or repealed if there was a majority in parliament. In addition, some enabling laws allowed the ordinances to depart from the constitution.

Thanks to such an authorization, a government could regulate a legal matter anew, even if it was already dealt with by a law. The statutory ordinance replaced that law as a later law. The government did not have to endeavor to organize a majority in parliament for the new regulation. Likewise, the government could regulate any legal matter at all, even if the constitution required a law on the matter.

The Bismarck Reich constitution , the Weimar constitution and the Basic Law do not provide for any statutory ordinances or a deviation from the constitution. The Basic Law differs from its predecessors in that it expressly forbids the latter ( Article 79 paragraph 1 ). In addition (paragraph 3), the amending law may not divide the federal government into states, the fundamental participation of the states in federal legislation or the principles laid down in Articles 1 and 20 of the Basic Law such as rule of law , democracy , federal structure , respect for human dignity u. a. m. touch ( eternity clause ).

The Basic Law knows a legislative emergency . According to this regulation, a law can also come into force without the consent of the Bundestag if the Federal Government obtains the consent of the Federal President and the Bundesrat . Functionally, this regulation can be slightly compared with some enabling laws, since a government without a parliament can introduce a legal norm with legal force (e.g. a budget law). Such a regulation was introduced in 1949 in the event that parliament, as in the Weimar Republic, was temporarily unable to legislate or to cooperate with the government. However, it is not an authorization, since Parliament does not grant the government an authorization of its own accord in the event of a legislative emergency.

Enabling laws until 1933

War Authorization Act of 1914

On August 4, 1914, the German Reichstag , the parliament of the German Reich , approved the War Enabling Act ( law on the authorization of the Federal Council to take economic measures and on the extension of the time limits for the law of exchange and checks in the event of warlike events , RGBl. 1914 , P. 327). A total of 17 laws of war were passed on that day. This was intended to empower the Federal Council or the Reich leadership to take the economic measures necessary for the war, to “remedy economic damage”. Similar laws were also in the other warring states during the First World War .

The law was considered legal because it was to apply for a limited period and because the Reichstag had to be informed of the measures and could override the bills. In addition, general legislation by the Reichstag continued to exist. In the four years of the war there were 825 orders under the law, of which only five were objected to (they referred to legal proceedings). Normally they had a direct or indirect reference to the economy and not to press law, police law, etc. The Reichstag has only rarely called for a repeal, but because of this possibility the Bundesrat has only made moderate use of its powers.

However, the law meant the "breakthrough of a new constitutional principle of extraordinary importance", so Ernst Rudolf Huber , because of the example for the Weimar period from 1919. It was a constitutional breach that contradicted the constitution, but was accepted. because it came about under the circumstances that would have been necessary for a constitutional amendment. The constitutional text itself, however, has not been changed.

After the emperor's abdication on November 9, 1918, it was not until the law on provisional imperial power of February 10, 1919 that an unquestionably legitimate government took over. Thus went out of 1914. However, remained the War Powers Act, some old authorizations in force even after the entry into force of the new Constitution of 11 August 1919. This is, for example, the Federal Council ordinance on war measures to ensure the nation's food from the 22nd May 1916/18. August 1917, which was declared still valid in 1919 by the Reich Minister of Labor. That was constitutionally inadmissible, says Huber, but prevailed. In total, there were 215 such legislative acts based on the old authorizations.

Enabling Acts 1919–1927

The German National Assembly of 1919/20 and the Reichstag since June 1920 passed several enabling laws "to resolve state crises" (Sylvia Eilers). The laws found their limits in the fact that they were not allowed to curtail basic rights (unless the law specifically mentioned it) and that the Reichstag could repeal them. As a rule, they were limited in time, but the ordinances issued on the basis of them could remain in effect for a long time.

| Surname | RGBl. | decided | validity | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency law for Alsace-Lorraine affairs | 257 | March 1, 1919 | unlimited, the nature of the matter ended | State committee had to agree |

| Act implementing the Armistice Conditions | 286 | March 6, 1919 | until the end of the National Assembly | |

| (First) law on a simplified form of legislation for the purposes of the transition economy | 394 | April 17, 1919 | until the end of the National Assembly | State committee and a committee of the National Assembly had to approve; Basis for many significant, permanent power of attorney regulations |

| (Second) Law on the Simplified Form of Legislation for the Purposes of the Transitional Economy | 1493 | August 3, 1920 | until November 1, 1920 | Reichsrat and a Reichstag committee had to agree |

| (Third) Law on the Enactment of Regulations for the Purposes of the Transitional Economy | 139 | February 6, 1921 | until April 6, 1921 | Reichsrat and a Reichstag committee had to agree |

| Art. VI of the Reich Emergency Act | I 147 | February 24, 1923 | until June 1, 1923 | Reichsrat had to agree (in some of the cases) |

| (First) Reich Enabling Act | I 943 | October 13, 1923 | until the end of the government or its party-political composition, that is until November 2, 1923, when the SPD left the coalition; otherwise the validity of the law would have been limited to March 31, 1924 | "Stresemann's Enabling Act" |

| (Second) Reich Enabling Act | I 1179 | December 8, 1923 | until February 15, 1924 | “Marx's Enabling Law”; The Reichsrat and the Reichstag committee had to be heard “in confidential deliberation”; The Reichstag adjourned until February |

| (First) Reich Enabling Act on the Provisional Application of Economic Agreements | II 421 | July 10, 1926 | valid for six months, only outside the sessions of the Reichstag (i.e. until November 3, 1926) | |

| (Second) Reich Enabling Act on the Provisional Application of Economic Agreements | II 466 | July 14, 1927 | six months, only outside the session periods of the Reichstag (i.e. until October 18, 1927) |

The first two laws (of March 1 and 6, 1919) dealt with only a limited part of the legislation, namely the surrender of Alsace-Lorraine and the armistice. The others, on the other hand, were only vaguely limited; the enabling laws for the Stresemann and Marx governments (October and December 1923) were “clearly blank powers,” according to Huber. The enacted power of attorney ordinances had to adhere to the imperial constitution , even if that was not expressly mentioned . Only Stresemann's Enabling Act permitted a deviation from the basic rights. From 1919 to 1925 around 420 “statutory ordinances” were passed, based on the authorizations since 1914. They had the greatest influence on the "social, economic, financial and judicial constitution", from the establishment of the Deutsche Rentenbank and the closure of operations to the creation of the Reichsbahn and tax legislation.

The laws were "constitutional" although they did not change the text of the constitution. The Constitution itself did not provide for one body to delegate its rights to another body. Thus the enabling laws were not legal, judges Huber, a secret circumvention of the constitution. The fact that the laws were passed by a two-thirds majority in the Reichstag, the same majority that would have been necessary for a constitutional amendment, did nothing to change this. Sylvia Eilers commented:

"The specialty of an enabling law lay in the fact that the parliamentarians believed in a voluntary act of self-elimination that they had to free the executive from parliamentary 'obstacles' due to their greater expertise, their impartial party-political impartiality and their experience."

The respective opposition largely supported these laws, for example the German National People's Party in 1919 or the Social Democratic Party in 1920/21. This was done through approval or tolerance by not participating in the vote. One reason for this was, not least, the government's threat to implement regulations in another way if they were rejected. For example, on February 26, 1924, the Reichstag debated whether it wanted to suspend certain ordinances. Then Reich Chancellor Wilhelm Marx announced, with the consent of Reich President Friedrich Ebert , that in this case the Reichstag would be dissolved. The Reichstag then decided to postpone the treatment. After the government had launched a major legislative program for vital measures in the time of crisis, the opposition wanted to deal with the repeal requests. Ebert dissolved the Reichstag, thus preventing it from performing its constitutional task.

As an alternative to an enabling law, the Reich government could ask the Reich President to issue dictatorship ordinances (so-called emergency ordinances ) under Article 48 of the Constitution. Much use was made of these ordinances, only intended for real emergencies, especially in the years 1919–1923 and 1930–1933. For the Reichstag, an enabling law had the certain advantage that it could negotiate time limits and a say (for example via a separate committee). However, since the radicalization of the German Nationalists from 1928 and the growth of the NSDAP from 1930, the Reich governments no longer saw majorities for a corresponding two-thirds majority.

Enabling laws in the countries (before 1933)

There were also enabling laws and emergency ordinances in the countries of the German Reich . The Prussian Constitution of 1920 (Art. 55) provided that if the Landtag was not in session, the government could issue ordinances with the force of law. To do this, she needed the approval of a certain parliamentary committee. An ordinance was to be repealed if the state parliament requested this at its next session. Fourteen out of eighteen countries had such an emergency ordinance right. Prussia in particular made use of this (93 emergency ordinances), followed by Thuringia (89) and Saxony (61). In addition, there were ordinances based on state authorization laws, a Reich authorization law or emergency articles of a state or the Reich constitution. Both left and center-right governments made similar extensive use of such instruments as the national level.

One example is the law passed by the Thuringian state parliament , primarily on the initiative of the local interior and national education minister Wilhelm Frick and promulgated on March 29, 1930, which restructured the state administration and the structure of the authorities.

Enabling Act of March 24, 1933

The laws of the 1920s, especially the Stresemannian and Marxian enabling laws, created dangerous models for breaking the constitution. When Adolf Hitler tried to consolidate his dictatorship at the beginning of 1933 , he aimed purposefully towards an enabling law. His law to remedy the misery of the people and the Reich of March 24, 1933 differed in decisive points from Marx's Enabling Law of 1923:

- According to his Enabling Act, Hitler's government should be able to pass not only ordinances but also laws and contracts with foreign countries.

- The laws passed in this way could deviate from the constitution.

- The regulation was not restricted to subject matter and should last four years.

- Neither a Reichstag committee nor the Reichsrat could exercise control or at least subsequently demand that it be repealed.

There is another difference in the parliamentary situation: In contrast to the Marxian minority cabinet , the NSDAP had an absolute majority in the Reichstag since the elections on March 5, 1933, together with the black-white-red front formed (among other things ) by the DNVP . Hitler's intention was to switch off the Reichstag and de facto suspend the constitution in order to achieve the abolition of the separation of powers . For this purpose, the rules of procedure of the Reichstag were initially changed in order to be able to meet the formal requirements for attendance despite the imprisonment and absence of the communist deputies. Then - in the presence of armed and uniformed SA and SS members illegally present in the Reichstag - the Enabling Act was passed under the new rules of procedure.

All parties except the SPD approved both the change in the rules of procedure and the “Law to Eliminate the Needs of the People and the Reich”; because of the dissenting votes of the SPD, the votes of the Center Party were decisive for achieving a two-thirds majority and the final adoption of the law .

content

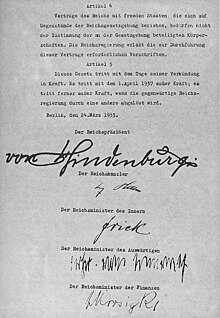

Original excerpt from the Enabling Act that came into force on March 24th:

The Reichstag has passed the following law, which is hereby promulgated with the consent of the Reichsrat after it has been established that the requirements of constitutional legislation have been met:

Art. 1. Reich laws can be passed by the Reich government in addition to the procedure provided for in the Reich constitution . This also applies to the laws referred to in Articles 85, Paragraphs 2 and 87 of the Imperial Constitution.

Art. 2. The imperial laws passed by the imperial government can deviate from the imperial constitution insofar as they do not deal with the establishment of the diet and the imperial council as such. The rights of the Reich President remain unaffected.

Art. 3. The Reich laws passed by the Reich Government are drawn up by the Reich Chancellor and announced in the Reich Law Gazette. Unless otherwise stipulated, they come into force on the day following the announcement. [...]

Art. 4. Contracts between the Reich and foreign states that relate to subjects of Reich legislation do not require the consent of the bodies involved in the legislation. The Reich Government issues the regulations necessary for the implementation of these contracts.

Art. 5. This law comes into force on the day of its promulgation. It expires on April 1, 1937; it also ceases to be in force if the present Reich government is replaced by another.

This meant that new laws no longer had to be constitutional, in particular that the observance of basic rights could no longer be ensured, and that laws could also be passed by the Reich government alone in addition to the constitutional procedure . Thus the executive also received legislative power. The constitutional articles 85, paragraphs 2 and 87 mentioned in the first article bound the budget and borrowing to the legal form. Through the Enabling Act, the budget and borrowing could now be decided without the Reichstag.

The validity of the Enabling Act was four years - thus Hitler's demand “Give me four years and you will not recognize Germany” was realized.

Debate in Parliament

Since the Reichstag building could not be used after the Reichstag fire , parliament met on March 23, 1933 in the Kroll Opera House . The building was cordoned off by the SS , which appeared on a larger scale for the first time that day. Long SA columns stood inside . Another innovation was a huge swastika flag hanging behind the podium. At the opening, the President of the Reichstag Hermann Göring gave a commemorative speech in honor of Dietrich Eckart .

- Then Hitler in a brown shirt stepped onto the podium. It was his first speech to the Reichstag , and many members of parliament saw him for the first time. As in many of his speeches, he began with the November Revolution and then outlined his goals and intentions. In order for the government to be able to carry out its tasks, it had introduced the enabling law.

"It would contradict the meaning of the national survey and would not be sufficient for the intended purpose if the government wanted to negotiate and request the approval of the Reichstag for its measures on a case-by-case basis."

- He then reassured them that this would not endanger the existence of the Reichstag or the Reichsrat, the existence of the states, or the position and rights of the Reich President. Only at the end of his speech did Hitler threaten that the government would also be ready to face rejection and resistance. He concluded with the words:

"May you, honorable Members, now make the decision yourself about peace or war."

- This was followed by ovations and the singing of the Deutschlandlied, which was intoned while standing .

- Prelate Ludwig Kaas , chairman of the Catholic Center , justified his party's yes to the Enabling Act before the German Reichstag :

“For us, the present hour cannot stand under the sign of words; its only, its ruling law is that of swift, edifying and saving action. And this act can only be born in the gathering.

The German Center Party, which for a long time and despite all temporary disappointment, has vigorously and decisively represented the great idea of collecting, deliberately disregards all party-political and other thoughts at this hour, when all small and narrow considerations must be silent, out of a sense of national responsibility . [...]

In the face of the burning need in which the people and the state are currently facing, in the face of the gigantic tasks that the German reconstruction is placing on us, in the face of the storm clouds that are beginning to rise in and around Germany, we reach out from the German Center Party At this hour, shake hands with all, including former opponents, in order to ensure the continuation of the national advancement work. "

- For the Social Democratic parliamentary group, the SPD chairman Otto Wels justified the strict rejection of the bill; he spoke the last free words in the German Reichstag:

“[...] Freedom and life can be taken from us, but not honor.

After the persecution which the Social Democratic Party has recently experienced, no one can reasonably demand or expect from it that it will vote for the enabling law introduced here. The elections on March 5 brought the ruling parties a majority and thus gave them the opportunity to govern strictly according to the wording and meaning of the constitution. Where this is possible, there is also an obligation. Criticism is wholesome and necessary. Never since there was a German Reichstag has the control of public affairs by the elected representatives of the people been eliminated to the extent that it is happening now, and as the new Enabling Act is supposed to do even more. Such omnipotence on the part of the government must be all the more difficult as the press, too, lacks any freedom of movement.

[...] At this historic hour, we German Social Democrats solemnly acknowledge the principles of humanity and justice, freedom and socialism. No enabling law gives you the power to destroy ideas that are eternal and indestructible. [...] German social democracy can also draw new strength from new persecutions.

We greet the persecuted and oppressed. We greet our friends in the kingdom. Your steadfastness and loyalty deserve admiration. Your courage to confess, your unbroken confidence guarantee a brighter future. "

(The verbatim transcript recorded several applause and approval from the Social Democrats and laughter from the National Socialists .)

- Then Hitler went back to the lectern. Hateful and repeatedly interrupted by stormy applause from his supporters, he denied the Social Democrats the right to national honor and rights and, alluding to his words, confronted Wels with the persecution that the National Socialists had suffered in the 14 years since 1919. The National Socialists are the real advocates of the German workers. He doesn't want the SPD to vote for the law: "Germany should become free, but not through you!"

The minutes of the meeting noted long-lasting calls for healing and applause from the National Socialists and in the stands, clapping hands with the German nationalists, as well as stormy applause and calls for healing. Joseph Goebbels noted in his diary (March 24, 1933):

“You never saw anyone being thrown to the ground and finished off like here. The guide speaks freely and is in great shape. The house rushes with applause, laughter, enthusiasm and applause. It will be an unparalleled success. "

Confrontation in the center

Due to the change in the rules of procedure for votes in the Reichstag on the Enabling Act, the necessary two-thirds majority depended only on the behavior of the center and the Bavarian People's Party (BVP).

The negotiations with the National Socialists in the run-up to the Reichstag session had exposed the center faction to an acid test. Many MPs had received personal threats against themselves or their families and were under the shock of the arrest of the Communist MPs and the threats of the SA and SS men who marched into the meeting room. The former SPD member of the Reichstag Fritz Baade wrote in 1948:

“If the whole center had not been forced through physical threats to vote for this enabling law, there would not have been a majority in this Reichstag either. I remember that MPs from the Center Group [...] came to me crying after the vote and said that they were convinced that they would have been murdered if they had not voted for the Enabling Act. "

Finally, the party chairman, Prelate Kaas, advocate of an authoritarian national collection policy, prevailed against the minority around Heinrich Brüning and Adam Stegerwald . Kaas was of the opinion that resistance by the center to Hitler's rule would change nothing as a political reality. One will only gamble away the chance of keeping the guarantees promised by Hitler. These included:

- Continuation of the highest constitutional organs and the states ,

- Securing Christian influence in schools and education,

- Respect for country concordats and the rights of Christian denominations,

- Irremovability of judges ,

- Retention of the Reichstag and the Reichsrat ,

- Preservation of the position and rights of the Reich President .

This attitude can also be seen in the context of the Kulturkampf against Otto von Bismarck , in which the Roman Catholic Church was unable to assert itself against the introduction of the sole validity of civil marriage and state school supervision . In addition, according to Kaas, large parts of the party would like a better relationship with the NSDAP and can hardly be prevented from moving to Hitler's camp.

Following his speech, the Bavarian People's Party was justified by MP Ritter von Lex .

Both the members of the Center and the members of the Bavarian People's Party voted for the Enabling Act without exception. The Center Party is said to have demanded group discipline from its members of the Reichstag ( see Eugen Bolz ). The Frankfurt MP Friedrich Dessauer spoke out against the Enabling Act in the preliminary discussion on the day of the vote, but gave in later.

The Center Party voted for the Enabling Act as part of a general rapprochement between the National Socialists and the Catholic Church in Germany ; In this context, the Reich Concordat was concluded a few weeks later , in which the center chairman Kaas, who had meanwhile permanently moved to Rome, now represented the Vatican side. However, a specific agreement between the National Socialists and the Vatican on a connection between the Enabling Act and the Reich Concordat ( Junktim thesis) does not seem to have existed.

Behavior of the Liberals

The five MPs ( Hermann Dietrich , Theodor Heuss , Heinrich Landahl , Ernst Lemmer , Reinhold Maier ) of the German State Party disagreed at first, but then all followed the majority of three MPs who wanted to agree despite concerns. The parliamentary group's justification was given by MEP Maier:

“In the major national goals, we feel bound by the view as presented today by the Chancellor of the Reich [...]. We understand that the current Reich government requires extensive powers to work undisturbed [...]. In the interest of the people and fatherland and in the expectation of a lawful development, we will put aside our serious concerns and agree to the Enabling Act. "

poll

| Political party | Seats | proportion of | approval | Rejection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSDAP | 288 | 45% | 288 | 0 |

| DNVP | 52 | 8th % | 52 | 0 |

| center | 73 | 11% | 72 * | 0 |

| BVP | 19th | 3% | 19th | 0 |

| DStP | 5 | 1 % | 5 | 0 |

| CSVd | 4th | 1 % | 4th | 0 |

| DVP | 2 | 0.3% | 1** | 0 |

| Peasant party | 2 | 0.3% | 2 | 0 |

| Landbund | 1 | 0.2% | 1 | 0 |

| SPD | 120 | 19% | 0 | 94 |

| KPD | 81 | 13% | 0 *** | 0 |

| total | 647 | 100% | 444 (69%) | 94 (15%) |

*) One MP was excused.

**) One MP was sick.

because they were already arrested or on the run.

Two thirds of the MPs present had to agree to the bill being passed ; it was also necessary that two thirds of the legal members of the Reichstag were present at the vote. Of the 647 MPs, 432 had to be present. The SPD and KPD had 201 members. In order to prevent the validity of the vote, in addition to these 201 MPs, only 15 other MPs would have had to stay away from the vote (647−216 = 431). In order to prevent this, the Reich government applied for a change in the rules of procedure. According to this, those MPs who did not attend a session of the Reichstag without an excuse should also be considered to be present. These “unexcused” missing also included MPs who were previously taken into “ protective custody ” or expelled. Although the SPD expressly pointed out the risk of abuse, all parties apart from it agreed to this change in the rules of procedure.

Göring and Hitler managed to get the bourgeois parties on their side - on the one hand through previous negotiations on March 20, and on the other hand through an effective threat that the SA built up through its presence. The forced absence of the KPD MPs due to arrest, murder and flight increased the pressure on the bourgeois parliamentarians.

After the killing of the KPD, "whose mandates have been withdrawn by ordinance", the SPD alone (94 votes) voted against the law in the Reichstag. 109 MPs from different political groups did not take part in the vote:

- 26 members of the SPD were imprisoned or fled

- 81 MPs of the KPD (the entire parliamentary group) were illegally arrested before the vote or had fled and went into hiding

- 2 other MPs were sick or excused

According to the official protocol, a total of 538 valid votes were cast, 94 members of parliament voted “No”. All other MPs (444 in total) voted for the law. This was done either out of conviction or out of concern for their personal safety and the safety of their families, but also because they bowed to their party's faction pressure. Prominent examples that despite reservations and u. a. The later Federal President Theodor Heuss, the later Federal Minister and CDU politician Ernst Lemmer and the first Prime Minister of Baden-Württemberg Reinhold Maier (DStP) agreed to personal abstentions from the Enabling Act . When Hermann Göring announced the result of the vote, the NSDAP MPs stormed forward and sang the Horst Wessel song .

Consequences and outlook

Now it wasn't just the press that was censored , but within a few weeks the first concentration camp (KZ) was set up in Dachau near Munich (March 22, 1933; from April 1, 1933, after Heinrich Himmler had been appointed political police commander, the SS provided the Guards). A large part of the civil service was dismissed (all civil servants with a Jewish grandparent, plus all - including non-Jewish - opponents of the regime). This government resolution was euphemistically called the “ Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service ” (April 8, 1933). Union property was confiscated immediately after Labor Day May 1, and union leaders were arrested that same day, May 2, 1933. Finally, between May and July, all political parties except the NSDAP were banned one after the other (apart from the SPD and KPD, all other parties disbanded voluntarily, including the DNVP, which was in coalition with the NSDAP). Previously, all municipalities and states in the country had already been "brought into line", i. H. the federal structure of the democratic state had been replaced by the centralistic dictatorship of the imperial government.

By law of December 1, the “ unity of state and party ” was finally proclaimed. The Reichstag, which was now completely ruled by the NSDAP, met only a few times in the years that followed until 1945; almost all new laws were passed by the Reich government or by Hitler himself. To the end, many of those affected had illusions about the suppression that would prevail from then on.

The Enabling Act became the key law for bringing Germany into line at all levels. Legislative procedures by the Reichstag soon became rare; Legislation by the Reich government also declined more and more (in the Reichsgesetzblatt , the laws passed on the basis of enabling laws can be recognized by the initial formula “The Reich government has passed the following law”). At the latest after the beginning of the war, the laws were replaced by ordinances and finally by Fuehrer's orders , which led to considerable legal uncertainty , as the numerous Fuehrer's orders were not always properly promulgated and often contradicted each other.

The law was extended by the National Socialist Reichstag , which was no longer a democratic institution, on January 30, 1937 for a further four years until April 1, 1941 and on January 30, 1939 until May 10, 1943. On the same day, Hitler determined by a decree the continued validity of the powers under the Enabling Act without time limit. In order to preserve a semblance of legitimacy , it says at the end: "I [ the Führer ] reserve the right to obtain confirmation [...] from the Greater German Reichstag." On September 20, 1945, the Enabling Act was passed through Control Council Act No. 1 regarding the repeal of Nazi law of the Allied Control Council formally repealed.

Because of its role in establishing the Nazi dictatorship, the Enabling Act of 1933 is far better known than any previous Enabling Act. In an overview work on historical controversies about the Weimar period, Dieter Gessner wrote : "Even 'enabling laws' passed with a 2/3 majority were possible under the constitution, even if no republican parliament made use of them until January 1933."

Enabling laws in the federal states (1933)

The issued under the terms of the Reich Enabling Act on March 31 Gleichschaltung law authorized the state governments, which now through the establishment of Reich Commissioners and the formation of coalition governments were controlled all by the Nazis to enact state laws without the consent of their state parliaments. Such laws were only allowed to violate the respective state constitutions if the state or local government was reorganized. The state parliaments could not be abolished either. The state governments now had almost the same powers in their sphere of influence as the Reich government at the Reich level. In most countries, the functionaries soon set about lifting the protection of the state constitutions. To this end, most of the state parliaments passed enabling laws from April to June, which entitle the state governments to also enact constitutional law. The NSDAP was able to acquire the majorities for these laws more easily than at the Reich level, since the state parliaments had been newly formed following the result of the Reichstag elections and the mandates of the KPD were no longer applicable. No state empowerment laws were passed in Anhalt , Braunschweig , Oldenburg , Bremen and Hamburg .

The individual state authorization laws:

- State of Thuringia : Enabling Act of May 3, 1933

- People's State of Hesse : Enabling Act of May 15, 1933

- Free State of Bavaria : Law to remedy the plight of the Bavarian people and state of May 21, 1933

- Free State of Saxony : Enabling Act of May 27, 1933

- Free State of Prussia : Law to Eliminate the Need of People and Land of June 1, 1933

- Republic of Baden : Enabling Act of June 9, 1933

- Free State of Mecklenburg-Schwerin : Law to remedy the distress of the state and the people of June 17, 1933

- People's State of Württemberg : Law to remedy the distress of the state (Enabling Act) of June 20, 1933

- Free State of Lippe : Enabling Act of June 21, 1933

- Free State of Mecklenburg-Strelitz : Law to remedy the needs of the people and the country of June 30, 1933

- Free State of Schaumburg-Lippe : Enabling Act of July 14, 1933

- Free and Hanseatic City of Lübeck : Law to remedy the needs of the people and the country of July 30, 1933

See also

- Roman dictator ( magistratus extraordinarius )

- Enabling Act (Iran)

- Seizure of power

- War Economic Enabling Act

literature

- Dieter Deiseroth : The Legality Legend. From the Reichstag fire to the Nazi regime . Sheets for German and International Politics 53, 2008, 2, ISSN 0006-4416 , pp. 91-102; also available on Eurozine (PDF; 54 kB).

- Sylvia Eilers: Enabling Act and Military Emergency at the Time of the First Cabinet of Reich Chancellor Wilhelm Marx 1923/1924. Cologne 1988 (also Diss. Cologne 1987).

-

Rudolf Morsey (ed.): The “Enabling Act” of March 24, 1933 . Series: Historical Texts: Modern Times. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1968. Several new editions, most recently Droste, Düsseldorf 2010, ISBN 978-3-7700-5302-5 . (Supplemented by comments from contemporary constitutional law teachers, by memories of 41 former members of the Reichstag (MdR), most extensively by Heinrich Brüning , as well as the later evaluation of the decision by historical scholars.) First edition online as:

- (Ed.): The “Enabling Act” of March 24, 1933 in the digitization project of the DFG Digi 20.

- Adolf Laufs: The Enabling Act ("Law to Eliminate the Need of the People and the Reich") of March 24, 1933. Reichstag debate, voting, legal texts. Contemporary legal history. Small series, vol. 9. Berliner Wissenschaftsverlag BWV, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-8305-0523-X .

- Roman Schnur : The enabling laws of Berlin 1933 and Vichy 1940 in comparison (Tübinger Universitätsreden, NF, Vol. 8), Eberhard-Karls-Universität, Tübingen 1993.

- Irene Strenge: The Enabling Act of March 24, 1933 . In: Journal der Juristische Zeitgeschichte 7 (1), 2013, ISSN 1863-9984 , pp. 1–14.

Web links

- Documents

- Original sound of the rejection of the Hitler Enabling Act by Otto Wels ( WAV ; 718 kB)

- Enabling Act, Text 1

- Enabling Act, Text 2

- Enabling Act, Text 3

- Enabling Act, Text 4

- Law to remedy the plight of the people and the Reich ["Enabling Act"], March 24, 1933 , in: 100 (0) key documents on German history in the 20th century , provided and introduced by Thomas Raithel (offer from the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek )

- Negotiations of the Reichstag, stenographic report, March 23, 1933, p. 25 C

- The session of the Reichstag in the Kroll Opera House on March 23, 1933, speeches by Wels and Hitler (easier to read source; PDF; 2.6 MB)

- Original sound of the Reichstag debate in the Kroll Opera House on March 23, 1933, speeches by Wels and Hitler (March 25, 2013)

- Memorial

- German Bundestag : 75 years ago: The Destruction of Democracy in 1933 - Memorial hour of the German Bundestag on April 10, 2008

- Historical context

- Historical debate

- Wolfgang Geiger: "Deceived", "seduced" or "taken by surprise" by Hitler? The Enabling Act in German historical consciousness - a balance sheet in the year 60 of freedom

- Enabling Act: "The SPD saved the honor of the Weimar Republic" (one day, Spiegel Online, April 12, 2008 - interview with the historian Heinrich August Winkler )

References and comments

- ↑ RGBl. 1933 I, p. 141.

- ↑ 1933–39: The “Enabling Act”. Deutsches Historisches Museum , Berlin, accessed on June 1, 2014 .

- ↑ "The abolition of democracy and the rule of law by a two-thirds majority in parliament and the Reichsrat was seen as constitutional." So Werner Heun , The Constitutional Order of the Federal Republic of Germany. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2012, ISBN 978-3-16-152038-9 , p. 23 with his presentation of the then prevailing view and the reference to the "universally accepted practice that laws, provided they were passed by the required two-thirds majority, too any of the Constitution differ or infringe as they could, without formally amending the Constitution. "

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber : German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume V: World War, Revolution and Reich renewal. Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1978, pp. 37, 62/63, 67.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume V: World War, Revolution and Reich renewal. Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1978, pp. 65-68.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume V: World War, Revolution and Reich renewal. Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1978, p. 63.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume VI: The Weimar Constitution . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1981, p. 437 f.

- ↑ Sylvia Eilers: Enabling Act and State of Emergency Military at the Time of the First Cabinet of Reich Chancellor Wilhelm Marx 1923/1924. Cologne 1988, p. 17.

- ↑ Reichsgesetzblatt 1919 p. 257 .

- ^ A b Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume VI: The Weimar Constitution . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1981, pp. 438-441.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume VI: The Weimar Constitution . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1981, p. 438.

- ^ A b c d Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume VI: The Weimar Constitution . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1981, pp. 439, 441.

- ^ A b Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume VII: Expansion, Protection and Fall of the Weimar Republic . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1984, p. 161.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume VI: The Weimar Constitution . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1981, pp. 439-441.

- ↑ Negotiations of the Reichstag, 1st electoral period 1920, p. 6281 Annex 5567 .

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume VII: Expansion, Protection and Fall of the Weimar Republic . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1984, pp. 363, 387.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume VII: Expansion, Protection and Fall of the Weimar Republic . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1984, p. 454.

- ^ A b Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume VI: The Weimar Constitution . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1981, p. 449.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume VI: The Weimar Constitution . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1981, pp. 441-443.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume VI: The Weimar Constitution . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1981, p. 439.

- ↑ Sylvia Eilers: Enabling Act and State of Emergency Military at the Time of the First Cabinet of Reich Chancellor Wilhelm Marx 1923/1924. Cologne 1988, p. 16.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume VI: The Weimar Constitution . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1981, pp. 440, 442.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume VI: The Weimar Constitution . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1981, p. 449 f.

- ↑ Jochen Grass: The grip on power - the Enabling Act of March 29, 1930 as a synonym for National Socialist will to experiment in Thuringia . In: VerwArch . Vol. 91, 2000, pp. 261-279.

- ↑ Sylvia Eilers: Enabling Act and State of Emergency Military at the Time of the First Cabinet of Reich Chancellor Wilhelm Marx 1923/1924. Cologne 1988, p. 163.

- ↑ Sylvia Eilers: Enabling Act and State of Emergency Military at the Time of the First Cabinet of Reich Chancellor Wilhelm Marx 1923/1924. Cologne 1988, p. 166.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Thamer : Beginning of the National Socialist Rule , Federal Agency for Civic Education , April 6, 2005.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz : The 101 most important questions. The Third Empire. CH Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 3-406-56849-1 , p. 12.

- ^ Hitler's speech on the grounds of the Enabling Act

- ↑ Opinion of Abg. Wels for the Social Democratic Party on the Enabling Act of March 23, 1933 .

- ↑ Otto Wels (SPD): Speech on the grounds for the rejection of the Enabling Act, Reichstag session of March 23, 1933 in the Berlin Kroll Opera ( Memento of July 12, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Hitler's reply to the Wels speech

- ↑ Fritz Baade (SPD) 1948 retrospectively in: Rudolf Morsey (Ed.): The “Enabling Act” of March 24, 1933. Sources for the history and interpretation of the “Law to remedy the needs of the people and the Reich”. Düsseldorf 1992, p. 163 f.

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Thamer: Beginning of the National Socialist Rule , in: National Socialism I. From the Beginnings to the Consolidation of Power (Information on Political Education, No. 251), new edition 2003, p. 43 (section “Authorization Act”; online ) .

- ↑ Negotiations of the Reichstag, stenographic report, March 23, 1933, p. 25 C , 37.

- ^ Prelate Kaas justifies the consent of the Center to the Enabling Act .

- ^ Negotiations of the Reichstag, shorthand report, March 23, 1933, p. 25 C , 37 f.

- ↑ Hubert Wolf : Historikerstreit: How the Pope stood when Hitler came to power , FAZ from March 28, 2008.

- ↑ Hubert Wolf, Pope and the Devil. Munich 2008, pp. 191, 194 f. (Paperback 2012 edition, ISBN 978-3-406-63090-3 ).

- ↑ a b Werner Fritsch, German Democratic Party , in: Dieter Fricke et al., Lexicon of Party History, Volume 1, Leipzig 1983, pp. 574–622, here p. 612.

- ^ Negotiations of the Reichstag, shorthand report, March 23, 1933, pp. 25 C - 45 , here p. 38.

- ^ Alfred Grosser, History of Germany since 1945. A balance sheet. Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag, 9th edition, Munich 1981, ISBN 3-423-01007-X , p. 35.

- ↑ Official protocol

- ↑ Hans-Peter Schneider , Wolfgang Zeh (Ed.): Parliamentary Law and Parliamentary Practice in the Federal Republic of Germany , de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1989, ISBN 3-11-011077-6 , pp. 677 ff. Rn 15, 16, 19 u. 20th

- ↑ Cf. for example the circular from the Reich Secretariat and the declaration by the members of the Reichstag dated March 24, 1933, in: Erich Matthias, Rudolf Morsey (ed.), The end of the parties 1933. Representations and documents. Unchanged reprint of the 1960 edition, Düsseldorf 1984, pp. 91–94.

- ↑ The law on the reconstruction of the Reich of January 30, 1934, brought the Länder into line.

- ^ Alfred Grosser, History of Germany since 1945. A balance sheet. Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag, 9th edition, Munich 1981, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ The Leader's decree on government legislation of May 10, 1943 (RGBl. 1943 I p. 295).

- ^ Dieter Gessner: The Weimar Republic . Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2002 (controversies over history), p. 98.

- ↑ Stefan Talmon : End of Federalism. In: Zeitschrift für Neuere Rechtsgeschichte , 24th year, 2002, Vienna, p. 128.

- ^ Collection of laws for Thuringia, No. 25, p. 253.

- ^ Enabling Act of May 15, 1933 . In: The Reichsstatthalter in Hessen (Hrsg.): Hessisches Regierungsblatt. 1933 No. 13 , p. 129 ( online at the information system of the Hessian state parliament [PDF; 17.1 MB ]).

- ↑ Law and Ordinance Gazette for the Free State of Bavaria 1933, No. 20, p. 149.

- ↑ Saxon Law Gazette 1933, No. 18, p. 73.

- ↑ Prussian Law Collection 1933, p. 186.

- ^ Badisches Gesetz- und Verordnungsblatt 1933, No. 39, p. 113.

- ^ Government Gazette for Mecklenburg-Schwerin 1933, No. 37, p. 201.

- ^ Government Gazette for Württemberg 1933, No. 32, p. 193 ( text of the law ).

- ↑ Lippische Gesetzsammlung 1933, No. 34, p. 105.

- ↑ Official Gazette for Mecklenburg-Strelitz 1933, No. 45, pp. 231–232.

- ↑ Schaumburg-Lippische Landesverordnung 1933, No. 27, p. 373.

- ↑ Law and Ordinance Gazette of the Free and Hanseatic City of Lübeck, No. 39, p. 136.