Free State of Prussia

| coat of arms | flag |

|---|---|

|

|

| Situation in the German Reich | |

|

|

| Arose from | of the Prussian monarchy |

| Incorporated into | the states of North Rhine-Westphalia , Hanover (later Lower Saxony ), Brandenburg , Saxony-Anhalt , Schleswig-Holstein , Rhineland-Palatinate , Saarland , Hesse , Thuringia , Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania , Württemberg-Hohenzollern (later Baden-Württemberg ), Saxony and Berlin . In 1945 the Province of Upper Silesia , parts of the Province of Pomerania , the Province of Lower Silesia , the Province of Brandenburg and the southern part of the Province of East Prussia fell to Poland . Its northern part is now part of Russia as the Kaliningrad Oblast . The state of Prussia was dissolved in 1947 by the Control Council Act No. 46 . |

| Data from 1925 | |

| State capital | Berlin |

| Form of government | Parliamentary democracy |

| Constitution | Prussian Constitution of 1920 |

| Consist | 1918 - 1933 / 1947 |

| surface | 291,700 km² |

| Residents | 38.120.173 (1925) |

| Population density | 131 inhabitants / km² |

| Religions | 64.9% ev. 31.3% Roman Catholic 1.1% Jews 2.6% others |

| Reichsrat | 26 (1926-1929: 27) |

| License Plate |

IAState Police District Berlin IB Grenzmark Posen-West Prussia (until 1938) ICProvince East Prussia IEProvince Brandenburg IHProvince Pomerania IKProvinces Upper and Lower Silesia ILDistrict Sigmaringen IMProvince Saxony IPProvince Schleswig-Holstein ISProvince Hanover ITProvince Hesse-Nassau IXProvince Westphalia IYDistrict Düsseldorf IZOther Rhine Province

|

| administration | 13 provinces, 34 administrative districts, 116 city districts, 361 districts (as of 1933) |

| map | |

|

|

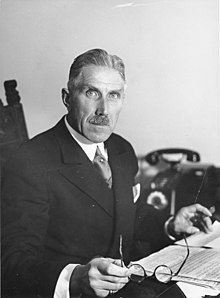

The Free State of Prussia , which emerged from the Prussian monarchy in the course of the November Revolution of 1918 , was the largest member state of the German Empire during the Weimar Republic . After its constitution in 1920, a parliamentary democracy , Prussia proved to be politically more stable than the Reich itself. The Free State was ruled almost entirely by the parties of the Weimar coalition : the SPD , DDP and Zentrum , at times expanded to include the DVP . With only brief interruptions, the Social Democrats, Paul Hirsch and Otto Braun, provided the Prime Minister . The interior ministers Carl Severing and Albert Grzesinski in particular pushed ahead with the reform of the administration and the police in the republican sense, so that Prussia was regarded as a bulwark of democracy during the Weimar period.

With the unconstitutional " Prussian Strike " of 1932, Reich Chancellor Franz von Papen placed the country under the control of the Reich and thus robbed it of its independence. With this, the Free State had de facto already ceased to exist during the National Socialist era , even if a Prussian government under Hermann Göring continued to function formally . After the end of the Second World War , the Control Council Act No. 46 of February 25, 1947 also determined de jure the dissolution of Prussia.

Revolution and constitution

November Revolution

Max von Baden , the last Chancellor of the German Empire , was like most of his predecessors at the same time Prime Minister of Prussia. On November 9, 1918, he announced the abdication of Wilhelm II as German Emperor and King of Prussia . The kingdom became the Free State of Prussia.

On the same day, Max von Baden transferred the office of Reich Chancellor to Friedrich Ebert . He was chairman of the MSPD , which was the largest parliamentary group in the Reichstag. Ebert, in turn, instructed Paul Hirsch, the leader of the MSPD parliamentary group in the Prussian House of Representatives , to maintain law and order in Prussia. The last Minister of the Interior of the Kingdom of Prussia, Bill Drews , legitimized the transfer of de facto government power to Hirsch. On November 10, Ebert was forced to form a joint government with representatives of the USPD , the Council of People's Deputies , and to enter into an alliance with the council movement .

On November 12, 1918, the representatives of the Executive Council of the Workers 'and Soldiers' Councils of Greater Berlin , among them Paul Hirsch, Otto Braun and Adolph Hoffmann , appeared at the previous Vice-President of the Prussian State Ministry Robert Friedberg . They declared the previous government to be deposed and claimed the management of state affairs for themselves. On the same day, the commissioners of the Executive Council issued the instruction that all organs of the state should continue their work as usual. In a manifesto to the population under the title “To the Prussian People!” It was said that the aim was to “transform the old, fundamentally reactionary Prussia [...] into a completely democratic component of the unified People's Republic ”.

Revolutionary Cabinet

As early as November 13th, the new government confiscated the Kron fideikommiss , the royal property, and placed it under the Ministry of Finance. The next day, majority and independent Social Democrats formed the Prussian Revolutionary Cabinet on the model of the coalition at the Reich level. It included Paul Hirsch, Eugen Ernst and Otto Braun from the MSPD, as well as Heinrich Ströbel , Adolph Hoffmann and Kurt Rosenfeld from the USPD. Almost all ministries were double-staffed by ministers from both parties. The Ministry of Culture, for example, was shared by the People's Commissioner Hoffmann (USPD) and Konrad Haenisch (MSPD). Hirsch and Ströbel became joint chairmen of the government. Other non-party ministers or those belonging to other political camps were added. This applies to the post of Minister of War - initially Heinrich Schëuch and from January 1919 Walther Reinhardt -, Minister of Commerce ( Otto Fischbeck , DDP) or Minister of Public Works ( Wilhelm Hoff ). However, only the politicians of the two workers' parties belonged to the narrow, decisive “political cabinet”. Since the leadership qualities of the two chairmen were comparatively low, Otto Braun and Adolph Hoffmann in particular set the tone in the provisional government.

Change and its limits

On November 14th, the mansion was abolished and the House of Representatives dissolved. However, the exchange of political elites remained limited in the first few years. The former royal district administrators often continued to hold office as if there had been no revolution. Interior Minister Wolfgang Heine either dismissed or ignored corresponding complaints from the workers' councils . When conservative district administrators themselves asked to be dismissed, they were asked to remain in order to maintain law and order.

On December 23, the government issued an ordinance on the election of a constituent assembly . The three-class suffrage was replaced by general, free and secret suffrage for men and women. However, it took eight months at the municipal level before the old bodies were replaced by democratically legitimized ones. Considerations for a fundamental reform of the property relations in the country, in particular the division of the large landed property, did not come to fruition, rather even the manor districts were initially retained as the political power base of the large landowners.

In the field of education policy, Minister of Culture Adolph Hoffmann began to promote the separation of church and state with the abolition of religious instruction. However, this step triggered considerable unrest and memories of the Kulturkampf in the Catholic areas . At the end of December 1919, the MSPD Minister Konrad Haenisch withdrew Hoffmann's decree. In a letter to the Archbishop of Cologne, Cardinal Felix von Hartmann , Prime Minister Hirsch assured that Hoffmann's provisions on the end of the spiritual school supervision were illegal because they had not been voted on in the cabinet. More than any other government measure, Hoffmann's socialist cultural policy turned large sections of the population against the revolution.

In the election campaign for the Prussian state assembly, advertising for female voters played an important role. In the Catholic regions of the country, the anti-clerical school program of the Minister of Education, Hoffmann, triggered the fear of a return to the Kulturkampf; this enabled the center to mobilize its electoral base.

The Christmas riots in Berlin between the People's Navy Division and the Guards Rifle Regiment sent under the Ebert-Groener Pact led, as in the Reich, to the withdrawal of the USPD from the government in Prussia. The dismissal of the USPD politician Emil Eichhorn as police president of Berlin triggered the Spartacus uprising from January 5 to 12, 1919.

Separatist tendencies and threatened breakup

The continued existence of Prussia was by no means assured after the revolution. For fear of a red dictatorship , the advisory board of the Rhenish Center called on December 4, 1918 for the formation of a Rhenish-Westphalian Republic independent of Prussia . In the province of Hanover , 100,000 people signed the call for territorial autonomy. In Silesia there were efforts to create an independent country. A revolt broke out in the eastern provinces at Christmas 1918 with the aim of restoring a Polish state. The movement soon spread across the entire province of Poznan and eventually took on the character of a guerrilla war .

But even for many proponents of the republic, Prussian dominance seemed a dangerous burden for the empire. Hugo Preuss therefore envisaged in his original ideas for the new imperial constitution the breaking up of Prussia into various smaller states. In view of the Prussian dominance in the empire , there was definitely sympathy for it. The People's Representative Otto Landsberg said: “Prussia has conquered its position with the sword and this sword is broken. If Germany is to live, Prussia must die in its present form. "

The new socialist government of Prussia was opposed to this. On January 23, the participants in a crisis meeting of the Central Council and the then provisional government spoke out against the dissolution of Prussia. If the center abstained, the regional assembly passed a resolution during its first sessions against a possible break-up of Prussia. Apart from a few exceptions, including Friedrich Ebert, the breaking up of Prussia found little support from the people 's representatives at the Reich level, because this was seen as the first step in the separation of the Rhineland from the Reich.

But the mood in Prussia was not that clear. In fact, in December 1919, the state assembly passed the resolution with 210 votes against 32: "As the largest of the German states, Prussia sees its duty in first trying to see whether the creation of a single German state can already be achieved."

State assembly and coalition government

On January 26, 1919, the elections for the constituent Prussian state assembly took place. The SPD became the strongest parliamentary group, followed by the center and the DDP. The assembly met for the first time on March 13, 1919. This was overshadowed by the March unrest in Berlin as well as general strikes in the Ruhr area and in central Germany.

On March 20, the state assembly passed a law on the provisional order of state authority. As a result, all previous rights of the Prussian king, including his role as the highest authority of the Evangelical Church, were transferred to the State Ministry. However, it did not have the right to adjourn or close the national assembly. The State Ministry remained collegial, was appointed by the President of the National Assembly and relied on the trust of a majority in Parliament.

All previous laws that did not contradict the provisions on the provisional order remained in force. This created legal certainty .

The main task of the assembly was to draw up a constitution . The constitutional committee included eleven MPs from the SPD, six from the Center, four each from the DDP and DNVP, one from the USPD and one representative from the DVP.

On March 25, 1919, the previous Provisional Hirsch government resigned. As in the Reich, a coalition of MSPD, Zentrum and DDP (“ Weimar Coalition ”) took its place. This came together to 298 out of 401 seats. Paul Hirsch became Prime Minister. Albert Südekum became Minister of Finance, Wolfgang Heine Minister of the Interior and Konrad Haenisch Minister of Education. All three had an intellectual background that was rather untypical for the SPD and belonged to the right wing of the party. The unionist Otto Braun, who became the new Minister of Agriculture, was more likely to belong to the left wing. Adam Stegerwald (Minister of Public Welfare) and Hugo am Zehnhoff (Minister of Justice) belonged to the center. Otto Fischbeck became Minister of Trade and Rudolf Oeser Minister for Public Works from the DDP .

Most of the ministries had also existed in the monarchy. The Ministry for People's Welfare was new . This summarized the responsibility for all areas of public welfare. In addition to the Ministry of the Interior, it developed into one of the largest sub-authorities due to the variety of tasks.

Riots and the Kapp Putsch

While the workers in the Ruhr area were not very radical in the First World War , this changed after the revolution. As early as the end of January 1919 there had been massive strikes in the Ruhr mining industry in connection with the socialization movement in the Ruhr area ; these worsened the energy supply in large parts of the empire and Prussia in addition to the transport problems. Starting on April 1, 1920, a strike in the Ruhr area began in Hamborn with the aim of significantly improving working and living conditions. Demands for the socialization of mining were also made. In addition to the USPD and the KPD, syndicalists played a considerable role. After the Reich government dispatched the Lichtschlag Freikorps to the Ruhr area, the strike leadership (“Neunerkommission”) called for a general strike. A total of 350,000 miners, and thus the majority of the employees, then went on strike. Carl Severing , as Reich and State Commissioner, was supposed to calm the situation. He succeeded in breaking the hardened fronts and ultimately bringing about an end to the strike.

In August 1919, parts of the Polish population broke out in Upper Silesia ( 1st Polish Uprising ). The movement was suppressed by military means.

In Pomerania there were clashes between farm workers and large landowners who received support from the regional army units and voluntary corps. In September, Otto Braun implemented an emergency ordinance to enforce collective bargaining regulations for agricultural workers' wages.

In March 1920, the republican order in the Reich and in Prussia was called into question from the right by the so-called Kapp Putsch . This was part of Prussian history insofar as the landowners of the country were the only relatively closed social group behind the putschists. In addition, there were some military and members of the civil servant educated middle class. Overall, the coup was a rebellion by the old, conservative East Elbe milieu, which feared it would be disempowered. While the Reich government evaded to Stuttgart , the Prussian one stayed in Berlin. The general strike, initiated in particular by the trade unions and civil servants, largely paralyzed public life in Prussia. Most of the upper presidents were behind the legal state government. Only those in the provinces of Schleswig-Holstein, Hanover and East Prussia supported the putschists. It is noteworthy that the Upper President in East Prussia was the Social Democrat August Winnig . It looked different with many district administrators. There was a clear east-west difference between them. In the western provinces, almost all district administrators supported the constitutional government, even if only partly under pressure from the workers. In East Prussia all district administrators supported the anti-republicans.

After the rapid collapse of the coup, the general strike continued in the Ruhr area. Against Severing's will, free corpse soldiers were deployed again, and violent fighting broke out with a newly formed Red Ruhr Army . The Bielefeld Agreement to prevent civil war, which Severing was instrumental in enforcing , only led to the cessation of fighting in parts of the Red Ruhr Army; elsewhere they continued. At the beginning of April, Reichswehr troops marched into the Ruhr area and bloodily suppressed the uprising.

Domestic consequences

In Prussia, the Kapp Putsch and the general strike that followed led to a profound turning point that almost made Prussia a model republican state. Otto Braun replaced Hirsch as Prime Minister. Carl Severing became the new interior minister. Both were significantly more assertive than their predecessors in office. Hirsch and the finance minister Südekum were also politically discredited because they had negotiated with the putschists. The “Braun-Severing system” became synonymous with democratic Prussia.

Overall, the coup led to the republican parties moving closer together. The bourgeois wing in the center gave up its reservations about working with the SPD. Unreliable officials were dismissed in the administration ( see also below: Democratization of the state administration ).

Structures

National territory

| area | to state | Area in km² |

Inhabitants in 1000 |

Mother tongue German in% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poses | Poland | 26,042 | 1946 | 34.4 |

| West Prussia | Poland | 15,865 | 965 | 42.7 |

| Southeast Prussia | Poland | 501 | 25th | 36 |

| Pomerania | Poland | 10 | 0.2 | 100 |

| Silesia | Poland | 512 | 26th | 34.6 |

| West Prussia (Danzig) |

Free City of Gdansk | 1914 | 331 | 95.2 |

| East Prussia (Memel area) |

Lithuania | 2657 | 141 | 51.1 |

| East Upper Silesia | Poland | 3213 | 893 | 29.6 |

| Silesia (Hultschin) |

Czechoslovakia | 316 | 48 | 14.6 |

| North Schleswig | Denmark | 3992 | 166 | 24.1 |

| Eupen-Malmedy | Belgium | 1036 | 60 | 81.7 |

Most of Germany's territory ceded by the Treaty of Versailles concerned Prussian territory: Eupen-Malmedy fell to Belgium, Danzig became a free city under the administration of the League of Nations , and the Memelland came under Allied administration. The Hultschiner Ländchen went to Czechoslovakia, large parts of the provinces of Posen and West Prussia became part of the new Polish state. As before the partition of Poland, East Prussia was separated from the rest of the Reich and could only be reached without border controls by ship ( Sea Service East Prussia ), by air or via certain rail routes through the Polish Corridor . Referendums decided on further changes. In North Schleswig on February 10, 1920, 74% of the electorate voted for annexation to Denmark. This part fell to Denmark. On March 14, 81% of the voters in the southern part voted to remain in the German Reich. The new German-Danish border was set on May 26th. Eastern Upper Silesia fell to Poland, although the majority of voters here had voted to remain in the German Reich. In the vote in southern East Prussia and parts of West Prussia, over 90% of the voters were in favor of remaining in the German Reich. The Saar area was subordinated to the League of Nations for fifteen years before a referendum there too should decide. The realm of Alsace-Lorraine , which was in fact subordinate to the Prussian administration, was ceded to France without a vote.

The loss of territories had considerable negative economic and financial consequences for the Prussian state. In addition, there was the repatriation and provision of government employees. In the area of responsibility of the Ministry of Justice alone, 3500 civil servants and employees were affected.

The annexation of the Free State of Waldeck represented an increase in Prussian territory during the Weimar Republic . It started with the Pyrmont district after a referendum in 1921 . In 1929 the rest of the country followed suit. The economic interests of the state were largely concentrated in the Ministry of Trade and Industry. After the Ministry of the Interior, it was the second strongest state ministry and was able to work well beyond the Prussian borders and state competencies, both domestically and externally.

population

| area | under 2000 | up to 5000 | until 20,000 | up to 100,000 | over 100,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East Prussia | 61.2 | 5.9 | 10.8 | 9.6 | 12.4 |

| Hanover | 52 | 9.7 | 8.7 | 16.3 | 13.2 |

| Saxony | 41.7 | 14th | 12.2 | 13 | 19th |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 35.9 | 12.7 | 15.7 | 9.4 | 26.3 |

| Westphalia | 16.5 | 13.8 | 21.0 | 31.1 | 17.2 |

| Rhine Province | 18th | 11 | 15th | 14.8 | 41.2 |

| Prussia | 33.8 | 9.6 | 12.9 | 14.5 | 29.2 |

| German Empire | 35.6 | 10.8 | 13.1 | 13.7 | 26.8 |

The pre-war population growth did not continue after 1918 as it did in the pre-war period. In addition to the continuation of the demographic transition to the modern way of population with the fall in the birth rate and the birth surplus, the losses of the First World War played a role. The great migratory movements within Prussia subsided. With regard to exchange with foreign countries, in contrast to the period before 1914, there was a surplus. Immigration from ceded areas, but increasingly also immigration, especially from Eastern Europe, played a role here.

There were also big differences in terms of population density. In East Prussia in 1925 there were only an average of 60.9 inhabitants per square kilometer, but 295.6 in the Rhine Province. Because of the low population density in the rural regions, Prussia only had a below-average population density of 130.7 inhabitants compared to the German states. This corresponded to the population density of the People's State of Württemberg . In contrast, the Free State of Saxony had 333 inhabitants.

Settlement style and urban growth

| city | 1910 | 1925 | 1939 | growth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berlin | 2071 | 4024 | 4339 | 110% |

| Cologne | 516 | 700 | 772 | 50% |

| Wroclaw | 512 | 557 | 629 | 23% |

| Duisburg | 229 | 272 | 434 | 90% |

| eat | 295 | 470 | 667 | 126% |

| Dusseldorf | 359 | 433 | 541 | 51% |

| Dortmund | 214 | 322 | 542 | 153% |

| Koenigsberg | 246 | 280 | 372 | 51% |

Urbanization and urban growth lost momentum compared to before 1914. Nevertheless, the importance of the big cities increased.

The growth of the big cities was based not so much on immigration, but on incorporation. This applies, for example, to the formation of Greater Berlin in 1920, when 7 cities, 56 rural communities and 29 manor districts were incorporated. The communal reforms in the Ruhr area at the end of the 1920s were even more extensive and had more consequences for urban development.

With regard to the size of the congregation, there were still major differences. While in East Prussia in 1925 more than 60% of the inhabitants lived in village communities, in the province of Westphalia it was only 16.5%. In large cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants, 12.4% lived in East Prussia, but over 41% in the Rhine Province.

Economic structure

| area | Farmer. | Industry craft |

Trade traffic |

|---|---|---|---|

| East Prussia | 45.4 | 19.6 | 12.9 |

| Brandenburg | 31.5 | 36.6 | 13.9 |

| Berlin | 0.8 | 46.2 | 28.1 |

| Pomerania | 41.2 | 23.5 | 14.8 |

| Poznan West Pr. | 47.5 | 19.4 | 12.8 |

| Lower Silesia | 27.4 | 37.1 | 15.7 |

| Upper Silesia | 30.7 | 36.5 | 13.8 |

| Saxony | 23.5 | 42.2 | 16.0 |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 23.0 | 33.3 | 20.4 |

| Hanover | 31.7 | 33.9 | 16.9 |

| Westphalia | 13.3 | 56.8 | 14.2 |

| Hessen-Nassau | 21.9 | 39.6 | 18.9 |

| Rhine Province | 13.3 | 50.9 | 18.6 |

| Hohenzollern | 53.7 | 26.0 | 7.1 |

| Prussia | 22.0 | 41.3 | 17.5 |

In 1925, Prussia was dominated by industry and craft with 41.3% of all employees. In contrast, agriculture only played a subordinate role with 22%. The trade and transport sector was only slightly weaker at 17.5%. The other economic sectors lagged significantly behind. In this area, too, there were still major development differences. In East Prussia, for example, 45.4% of the workforce was still employed in agriculture. In industry and craft, however, it was only 19.6%. The Hohenzollerschen Lands were most strongly influenced by agriculture, where 53.7% of the population lived from agriculture. In contrast, agriculture was of very little importance in Rhineland and Westphalia, each with around 13%. In contrast, the commercial sector was very pronounced in these areas. This was strongest in Westphalia with over 56%. The city of Berlin was a special case, where only 0.8% worked in agriculture. The commercial sector was high at 46%. But the metropolitan character was mainly reflected in the share of the trade and transport sector with over 28%.

All in all, even after 1918 there were considerable economic differences between the largely agrarian east and the industrial west of the Free State.

Social structure

In 1925, almost half of the population was employed. Of these, 16.2% were self-employed, 17.1% were employees and civil servants, 15.4% were family workers and 4.5% were domestic workers. By far the largest social group were blue-collar workers with 46.9%. In addition there were 6% unemployed. Depending on the prevailing economic sector, the shares could diverge in the individual provinces. In the more rural East Prussia, the number of helping family members was 22.3%, significantly higher than in industrial Westphalia with 12.8%. Conversely, the proportion of workers in East Prussia was 42.6%, while in Westphalia it was 54.1%. In metropolitan Berlin, the proportion of workers at 45.9% was also lower than in Westphalia, for example, despite the important industry. The reason was the strength of the tertiary sector already achieved there. Employees and civil servants made up 30.5% in Berlin. In Westphalia this group came to only 15.6%.

The special urban situation in Berlin was also reflected in the average income. In Berlin-Brandenburg it was 1566 RM (1928), more than 30% above the national average. In the agrarian East Prussia the earnings were only 814 RM. This area was more than 30% below the realm average. Industrial areas such as the provinces of Saxony, Westphalia or the Rhineland were roughly in line with the German average.

The effects of the economic crises were also heavily dependent on the social and economic structure. At the height of the global economic crisis in 1932, only 45 out of 1,000 inhabitants in the East Prussian state labor office were unemployed. In Rhineland and Westphalia, on the other hand, unemployment was around 100 people. There were also significant differences among the big cities. In Münster , which is relatively less industrialized , the number of unemployed was only 50 per 1000 inhabitants, in Berlin it was 141, in Wroclaw 146, in Mönchengladbach 164 and in Solingen even 168.

Despite all the efforts of the Prussian government, for example in the field of education, upward mobility remained limited. In 1927/28 only one percent of legal trainees came from working-class families. The opportunities for advancement in the elementary school sector were significantly better. The proportion of students from working-class families in pedagogical academies rose from 7% in 1928/29 to 10% in 1932/33.

State and administration

Administrative division

see main article: Administrative division of Prussia

| area | Administrative headquarters | Area in km² |

Inhabitants in 1000 |

Population density per km² |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| East Prussia Province | Koenigsberg | 36,991 | 2,256 | 61 |

| Brandenburg Province | Potsdam | 39,039 | 2,592 | 66 |

| Greater Berlin | Berlin | 884 | 4,024 | 4,554 |

| Pomeranian Province | Szczecin | 30,270 | 1,879 | 62 |

| Poznan-West Prussia | Schneidemühl | 7,715 | 332 | 43 |

| Province of Lower Silesia | Wroclaw | 26,600 | 3.132 | 118 |

| Upper Silesia Province | Opole | 9,714 | 1,379 | 142 |

| Province of Saxony | Magdeburg | 25,528 | 3,277 | 128 |

| Schleswig-Holstein Province | Kiel | 15,073 | 1,519 | 101 |

| Hanover Province | Hanover | 38,788 | 3.191 | 82 |

| Province of Westphalia | Muenster | 20,215 | 4,811 | 238 |

| Rhine Province | Koblenz | 23,974 | 7,257 | 303 |

| Hesse-Nassau Province | kassel | 15,790 | 2,397 | 152 |

| Hohenzollern country | Sigmaringen | 1,142 | 72 | 63 |

| Free State of Prussia | Berlin | 291,700 | 38.206 | 131 |

| Waldeck | Arolsen | 1,055 | 56 | 53 |

The free state consisted of twelve provinces. There was also Berlin, whose status corresponded to a province. The Hohenzollerschen Lande in southern Germany formed a municipal association and some had their own provincial administration. At the head of the provinces were the high presidents appointed by the State Ministry . In addition to these, a provincial council consisted of the chief president, a member appointed by the interior minister and five members elected by the provincial committee. Parliamentary committees of the Provincial Association designated self-governing bodies of the provinces were the county councils . In Berlin the body was called the City Council, in Posen-West Prussia and in the Hohenzollerschen Lands the communal parliament, in Hessen-Nassau there were local councils for the district associations in addition to the provincial parliament. The provincial parliaments elected a governor ; the mayor corresponded to this in Berlin. In addition, the state parliament elected a provincial committee from among its own ranks to manage day-to-day business. The governor, the provincial parliament and committee were organs of (local) self-government. The provincial parliaments sent representatives to the Reichsrat and the Prussian State Council.

Below the provincial level there were 34 administrative districts (as of 1933), some of which such as Berlin, Posen-West Prussia, Upper Silesia, Schleswig-Holstein and the Hohenzollerschen Land were also provinces. A total of 361 districts, also known as rural districts, formed the basis of state administration in rural and small-town areas. Larger cities in particular were urban districts. There were 116 of these in total. While there were only five of them in agrarian East Prussia, there were 21 urban districts in industrial Westphalia.

Constitution

Delayed by the Kapp Putsch, but also by waiting for the imperial constitution, Severing did not submit a draft constitution until April 26, 1920. On November 30, 1920, the state assembly passed the Constitution of the Free State of Prussia . 280 MPs voted in favor, 60 against and 7 abstained. The DNVP and independent MPs in particular voted against the constitution.

Parliament

The legislative period of the state parliament was four years. The parliament could be dissolved by majority vote or referendum . The state parliament formed the legislature and had the right to set up committees of inquiry. With a majority of two thirds of the MPs, he was able to change the constitution. The parliament elected the prime minister. It also had the right to suspect members of the government or the State Department as a whole. With a two-thirds majority, it could indict ministers before the State Court.

State Ministry

| Surname | Political party | Start of office | End of office |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Paul Hirsch Heinrich Stroebel |

SPD USPD |

November 12, 1918 | January 3, 1919 |

| Paul Hirsch | SPD | January 3, 1919 | March 25, 1920 |

| Otto Braun | SPD | March 27, 1920 | March 10, 1921 |

| Adam Stegerwald | center | April 21, 1921 | November 5, 1921 |

| Otto Braun | SPD | November 7, 1921 | January 23, 1925 |

| Wilhelm Marx | center | February 18, 1925 | February 20, 1925 |

| Otto Braun | SPD | April 6, 1925 | July 20, 1932, managing director until February 6, 1933 |

|

Franz von Papen (Reich Commissioner) |

formerly the center, since June 3, 1932 non-party |

July 20, 1932 January 30, 1933 |

December 3, 1932 April 7, 1933 |

|

Kurt von Schleicher (Reich Commissioner) |

independent | December 3, 1932 | January 30, 1933 |

| Hermann Goering | NSDAP | April 11, 1933 | April 23, 1945 |

The State Ministry was the highest and leading authority in the country; it consisted of the Prime Minister and the Ministers of State (Art. 7). It was organized in a collegial manner, but the Prime Minister had the authority to issue political guidelines (Art. 46). The prime minister was elected by the state parliament. After a change in the rules of procedure, an absolute majority was required from 1932. The Prime Minister appointed the remaining ministers (Art. 45).

The ministries were not laid down in the constitution; these resulted from the requirements of practice. After the transfer of responsibility to the Reich, there has been no Prussian war minister since 1919. The Minister of Public Works also lost his most important area of responsibility when the Reichsbahn was founded. The ministry was dissolved in 1921. The office of welfare minister was created in the provisional government. In addition to the Prime Minister's office, there were also the Ministries of the Interior, Finance, Justice, Agriculture and the Ministry of Commerce. The Ministry of Spiritual, Educational and Medical Affairs was renamed the Ministry of Science, Art and Education in 1918.

After the Prussian strike, the Ministry of Welfare was dissolved in its old form. Since then the Minister of Commerce has also been Minister of Economics and Labor. The Ministry of Justice was dissolved under the law on the transfer of the administration of justice to the Reich in 1935.

State Council

The constitution set up a council of state to represent the provinces. The members were elected by the provincial parliaments, and they were not allowed to be members of the state parliaments at the same time. The government had to keep the body informed of state affairs. The State Council was able to express its views on this. But he also had the right to initiate legislation. He was able to appeal against laws of the state parliament. With a few exceptions, the Landtag was able to reject this with a two-thirds majority or call a referendum. The mayor of Cologne, Konrad Adenauer, was the chairman of the Council of State until 1933 .

Overall character of the constitution

In the constitution, elements of plebiscitary democracy were provided for with the referendum and referendum .

In contrast to the Reich and other countries in the Weimar Republic, there was no state president. The lack of an institution above the government and the parliamentary majority clearly distinguished Prussia from the Reich. Overall, the state parliament's position in the constitution was strong. But a special feature was the prime position of the Prime Minister due to his authority to issue guidelines. In particular, Prime Minister Braun recognized this clearly and used the guideline competence in a targeted manner.

Relationship with the empire

The Weimar Constitution in the Reich, which was passed on August 11, 1919, and the new Prussian constitution changed the relationship between Reich and Prussia permanently. After the revolution, the executive at the imperial level was completely independent of that of Prussia. The personal union between Chancellor and Prime Minister was a thing of the past. The great importance of state taxes declined in favor of a central tax administration. The empire now had tax sovereignty and distributed the income to the states. Much of the social administration was also a matter for the Reich. The military was now a matter for the Reich alone, and Prussia consequently abolished the office of Minister of War. With the formation of the Reichsbahn, the Prussian railway also became the responsibility of the Reich. The same was true of the waterways.

In spite of its size, Prussia only had two fifths of the votes in the Imperial Council . In contrast to the former Bundesrat and in contrast to the other countries, only half of the members of the Bundesrat to which Prussia is entitled were determined by the Prussian government. The remaining members were elected by the provincial parliaments.

State company

Between 1921 and 1925, the administration of the state-owned enterprises was outsourced from the direct responsibility of the Ministry of Trade and Industry on the initiative of Wilhelm Siering . The Preussische Bergwerks- und Hütten AG ( Preussag ) was founded in 1923 to manage the state mines, salt works and smelters . The AG was equipped with a capital of 100 million Reichsmarks in 1928. The shares remained in the possession of the state and passed to the Federal Republic of Germany after 1948. In addition to mining ores and lignite, the company operated water supply systems and oil production in northern Germany.

In 1927 the state founded the “Preussische Elektrizitäts-Aktiengesellschaft” ( Preußenelektra ) with a capital of 80 million Reichsmarks to generate electricity .

Both state-owned companies were merged in 1929 in the holding company of "United Electricity and Mining AG" ( VEBA ). Common economic ideas , such as those represented by State Secretary Hans Staudinger , also played a role in the accelerated development of state-owned companies .

Sovereign symbols

The flag of Prussia showed a black eagle on a white background, which could also be seen on the Prussian coat of arms . These colors were one of the origins for the black-white-red flag of the German Empire .

Up to the present day, the Prussian colors black and white are often used as symbols for the whole of Germany. In many sports, German athletes and selections make their appearances in white jerseys and black pants.

Political system

Party system

| area | NSDAP | DNVP | center | SPD | KPD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East Prussia | 0.8 56.5 |

31.4 11.3 |

7.4 6.5 |

26.8 14.6 |

9.5 8.7 |

| Berlin | 1.4 31.3 |

15.7 9.1 |

3.3 4.7 |

34 22.5 |

29.6 30.1 |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 4 53.2 |

23 10.1 |

1.1 1 |

35.3 22.2 |

7.9 10.7 |

| Opole | 1 43.2 |

17.1 7.5 |

40 32.3 |

12.6 6.9 |

12.7 9.3 |

| Westphalia | 1.3 34.3 |

8.9 6.7 |

27.4 25.5 |

27 16.1 |

10.4 13.8 |

| Hessen-Nassau | 3.6 49.4 |

10 4.9 |

14.8 13.9 |

32.2 18.7 |

8 9 |

| Rhine Province | 1.6 34.1 |

9.5 6.5 |

35.1 29.8 |

17.3 9.8 |

14.3 15.3 |

The Prussian party system made up of conservatism ( DNVP ), political Catholicism ( center ), liberalism ( DVP / DDP ), social democracy ( MSPD / SPD ) and socialism / communism ( USPD / KPD ) corresponded to that at the Reich level. The DNVP had a special affinity for the Prussian monarchy. The German-Hanoverian Party played a certain role among the regional parties .

DNVP and DVP had their focus in some cities and in predominantly more rural Protestant areas, especially in East Elbe . In East Prussia, the DNVP achieved over 30% in the 1928 Reichstag election . The center was strong in the Catholic areas such as Silesia , Rhineland and Westphalia . In the Reichstag constituency of Opole, the party achieved over 40% in 1928. The left-wing parties were important in the big cities and heavily commercial non-Catholic areas. In Berlin, for example, the SPD came to 34% in 1928, the KPD to almost 30%. This pattern changed with the rise of the NSDAP , but it remained largely formative until 1932.

Within Prussia, there were considerable differences in support for the republic. Berlin, Rhineland and Westphalia were mostly in favor of democracy, while reservations remained in the eastern and agrarian provinces. In the Reichstag election of March 1933 , the NSDAP was above average in Reichstag constituencies such as East Prussia (56.5%), Frankfurt an der Oder (55.2%), Liegnitz (54%) and Schleswig-Holstein (53.2%) Berlin (31.3%), Westphalia (34.3%) or the Rhine Province (34.1%) but significantly weaker than the realm average (43.9%).

One factor for the political stability of Prussia was that the SPD, as the strongest party for a long time, was ready to take over government responsibility until 1932 and not to take refuge in the opposition role as at the Reich level in 1920, 1923 or 1930. Those responsible in the Prussian SPD quickly identified with their new role. The philosopher Eduard Spranger spoke of an “affinity between Social Democracy and Prussia”, and Otto Braun claimed: “Prussia has never been governed more Prussian than during my term in office.” In addition to the people involved, structural reasons also played a role. The political break from three-class voting rights to the democratic constitution was more pronounced in Prussia than in the Reich. Long-standing SPD parliamentarians, used to the role of the opposition, hardly existed in the Prussian state parliament, unlike in the Reichstag. The parliamentary group members were therefore not so much influenced by well-worn role models and were better able to adjust to the role of the government group. In addition, the left wing of the party, which was critical of cooperation with the bourgeois parties, was weak. Compromise solutions were therefore easier to implement in Prussia than in the Reich.

Despite their strength, especially in the big cities, only a few mayors were Social Democrats in the big cities. The party respected the expertise of bourgeois local politicians and often left this position to representatives of the DDP. Only Ernst Reuter in Magdeburg and Max Brauer in Altona were social democrats in early 1933.

Democratization of the state administration

| Office | Total number | SPD | center | DDP | DVP | DNVP | not clear |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chief President | 12 | 4th | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| District President | 32 | 6th | 7th | 8th | 11 (?) | 0 | 0 |

| Police chief | 30th | 15th | 5 | 4th | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| District administrators | 416 | 55 | 81 | 47 | 74 | 6th | 153 |

The Prussian officials had declared during the revolution that their loyalty was not to the monarchy but to the Prussian state. Initially, the government and, in particular, Interior Minister Heine largely refrained from restructuring the state administration in the interests of the republic. Incidentally, Heine made a crucial mistake when he appointed Magnus Freiherr von Braun - later one of the supporters of the Kapp Putsch - as a personnel officer. At the end of 1919 only 46 Social Democrats had been installed in higher administrative posts. Of around 480 district administrators, only 24 belonged to the SPD. The Kapp Putsch showed that the loyalty of some of the senior officials, who were often close to the anti-republican DNVP, was only weak.

The new Interior Minister Carl Severing carried out a fundamental reform after the coup. Higher officials hostile to the Republic were dismissed, and political reliability was checked in the event of new appointments. In total, about a hundred senior officials were retired. Among these were three senior presidents, three regional presidents and 88 district administrators. Almost all of them came from the eastern provinces. In addition to supporters of the conservatives, there were also the social democratic presidents August Winnig (East Prussia) and Felix Philipp (Lower Silesia) .

Severing and his successors specifically appointed supporters of the coalition parties as political officials. These measures resulted in a considerable elite change at the top of the authorities. In 1929, of 540 political officials, 291 were members of parties in the Weimar coalition. 9 of the 11 senior presidents and 21 of 32 regional presidents belonged to the governing parties. This also changed the social composition. In 1918 11 upper presidents were aristocratic; between 1920 and 1932 there were only two. However, there were still deficits. While 78% of the newly appointed district administrators in the western provinces consisted of supporters of the governing parties, the situation in the eastern provinces was still significantly different in 1926. There the supporters of the coalition made up only a third of the district administrators. Two thirds, on the other hand, were mostly conservative non-party members.

Another limit was that it was not possible to break the legal monopoly for higher civil servant positions. Outsiders were only appointed in exceptional cases, such as the case of the Berlin police chief Wilhelm Richter.

Republicanization of the Police

The Prussian police were not only the strongest in the whole empire, they were also the most important instrument of the executive branch of the Prussian government for the maintenance of the constitutional order. In the area of the police, too, massive restructuring began after the Kapp Putsch in order to ensure their loyalty to the republic. Under the responsibility of the interior minister, the republican-minded police chief Wilhelm Abegg was the key figure in implementing the reform. There was also an elite change at the top in this area. At the end of the 1920s, all senior police officers were Republicans. Of the thirty police presidents in 1928, fifteen were members of the SPD, five belonged to the center, four to the DDP, three to the DVP, and the rest were non-party.

Below the management level, however, things looked a little different. Most of the police officers were former professional soldiers; much of it was conservative and anti-communist, and some had links with right-wing organizations. For them the enemy was still left.

An important change in the organization was the creation of the protective police as an instrument to protect the constitution and the republic.

Judiciary

In the area of the judiciary, reforms remained limited. Many judges remained supporters of the monarchy. In political criminal trials, the judiciary has ruled harder against left-wing offenders than against right-wing extremists. One reason for the hesitant intervention by Democrats and representatives of the Center was, in particular, the respect for the independence of the judiciary. The autonomy of judges was expressly enshrined in the constitution. This made a fundamental republicanization of the judiciary impossible. Incidentally, the Minister of Justice at the Zehnhoff , who held the office from 1919 to 1927, had no real interest in judicial reform. The authorities paid attention to democracy when hiring new employees. But the Free State did not exist long enough for this to have a noticeable effect. An estimate in 1932 assumed that only about 5% of judges were Republican.

Political history after 1921

Big coalition

Long road to the grand coalition

After the constitution was passed, the elections for the first regular state parliament were set for February 20, 1921. The strongest political force was the SPD (114 seats), followed by the center (84). Even if the DDP lost seats to the DVP, the Weimar coalition, unlike in the Reichstag election of 1920 , still had a majority, albeit a small one, with a total of 224 out of 428 seats. The formation of a new government, however, was not easy. While the DDP and the center also wanted to bring the DVP into the coalition, the SPD refused because of the DVP's proximity to heavy industry (“Stinnespartei”) and because of its unclear attitude towards the republic.

Therefore, Braun did not run as a candidate for the office of Prime Minister. Instead, Adam Stegerwald was elected Prime Minister with the votes of the previous coalition and the DVP. Stegerwald's attempt to form a permanent grand coalition failed. The SPD then gave up its support and Stegerwald resigned.

In a second election on April 21st, Stegerwald was re-elected with the votes of the bourgeois parties including the DNVP. He formed a minority government from the center and the DDP as well as some non-party members. This had to recruit support from the SPD and DNVP on a case-by-case basis.

Mainly external factors exerted pressure on Prussian politics. After the London ultimatum of May 5, 1921, parts of the Ruhr area were occupied by Allied troops. The assassination of Matthias Erzberger (August 26, 1921) shocked the Republicans. In September 1921, the SPD paved the way for a coalition with the DVP at its Görlitz party congress . Braun stated programmatically:

“This is about the conversion of our party from an active to a ruling party. This is very difficult for many, because it moves you from a comfortable position to a sometimes very uncomfortable and responsible position. [...] The comrades who speak against the resolution do not have sufficient confidence in our party's advertising power. We must have the will to power. "

After the SPD withdrew its support from the government in October 1921 because it accused the State Ministry of leaning towards the DNVP, negotiations began to form a grand coalition. On November 5, 1921, the SPD and DVP entered the cabinet and Stegerwald resigned.

Resistance in the SPD parliamentary group was great. In it, 46 MPs voted for and 41 against the formation of a grand coalition. There were also considerable reservations in the DVP. Ultimately, 197 of the 339 MPs present voted for the candidate Braun. Severing was again Minister of the Interior, Wilhelm Siering Minister of Commerce, the center deputies Hugo am Zehnhoff and Heinrich Hirtsiefer became Minister of Justice and Minister of Welfare, respectively. Hugo Wendorff (DDP) became Minister of Agriculture. Ernst von Richter and Otto Boelitz (both DVP) became ministers of finance and culture, respectively.

Beginnings of the Grand Coalition

In the years that followed, the grand coalition in Prussia proved to be a factor of stability and, in particular, contributed to the fact that the Weimar Republic was able to survive the crisis year of 1923. The DVP also remained loyal to the coalition, although it was wooed by the DNVP for the formation of a "civic bloc". In the background, an effective coalition committee successfully balanced the various political interests. For the functioning of the cooperation between the SPD and the center, Ernst Heilmann , chairman of the parliamentary group since autumn 1921, was of great importance on the part of the social democrats , and the group manager and, since 1932, the parliamentary group chairman Joseph Hess . Despite their collegial cooperation, Braun and Severing dominated the government.

The coalition reached important decisions in various policy areas, such as education policy.

The coalition claimed nothing less than a “Prussian mission” for all of Germany and clearly positioned itself with the “democratic mission of Prussia”. This was especially true after the murder of Walther Rathenau . The Reich law “Law for the Protection of the Republic” was expressly supported by the Prussian government. On November 15, 1922, Interior Minister Severing banned the NSDAP in Prussia on the basis of the Republic Protection Act.

Crisis year 1923

Prussian territory was directly affected by the occupation of the Ruhr by Allied troops; however, the essential decisions about the reactions were made at the level of the empire. Nevertheless, immediately before the occupation, the Prussian state parliament - with the exception of the KPD - protested against the actions of the French and Belgians. At the same time, the population in the Rhineland and Westphalia were called upon to be prudent. Ultimately, the Prussian government supported the passive resistance proclaimed by the Reich. The Prussian officials were instructed not to obey the occupiers' orders. However, it quickly became apparent that the economic burden of the conflict was immense. The tendency towards inflation that had existed since the First World War became hyperinflation .

Domestically, this strengthened the radical forces. After acts of violence by right-wing extremists, the Prussian Minister of the Interior banned the German Volkische Freedom Party, despite reservations from the Reich government. In public and in the Prussian state parliament Severing was then sharply attacked by the nationalist side. The Landtag supported the Interior Minister with a large majority.

Although the Prussian government had supported the passive resistance, it was pragmatic enough to recognize the failure of this policy and, in August 1923, to press for an end.

The end of the Ruhr struggle was a prerequisite for carrying out a currency reform. The occupied Rhineland was excluded from this. This gave the separatists a boost. A Rhenish Republic was proclaimed in various cities, but it met with little response from the population. At the end of the year, the separation of the Rhineland and Westphalia had definitely failed. The actual political crises of 1923, such as the Hitler coup in Bavaria and the “ German October ” in central Germany, took place outside of Prussia. Gustav Stresemann described Prussia in this time of crisis as the “bulwark of the German republicans”.

Transitional cabinet Marx

At the beginning of 1924 there were increasing signs that the commonalities of the grand coalition had been used up. On January 5, the DVP called for the DNVP to participate in the government and for Braun to resign. This refused; then the DVP withdrew its ministers from the government. This meant the end of the coalition. After that, a similarly difficult government formation began as in 1920. On February 10, the former Chancellor Wilhelm Marx (Zentrum) was elected Prime Minister, supported by the Zentrum, DDP and SPD. He formed a cabinet from the center and the DDP, to which, however, Severing continued to belong as Minister of the Interior. After losing a vote of confidence, Marx resigned, but remained in office as managing director.

The climax of political stabilization

The formation of a government was delayed because the two possible candidates, Marx and Braun, also ran for the office of Reich President in the 1925 presidential election. After Marx had been nominated as a presidential candidate by the SPD, Zentrum and DDP in the second ballot, Braun remained in Prussia as a promising candidate for the office of Prime Minister.

This was elected on April 3, 1925 with 216 of 430 votes. Like Marx, he relied on the SPD, Zentrum and DDP. Braun largely took over the cabinet from Marx. In terms of content, too, he relied on continuity. He made what he called the “German National Communist Bloc” responsible for the months-long government crisis - by which he meant all opposition parties from the DVP and DNVP to the various small parties, including the NSDAP, to the communists. “No, as unanimous as they are in destroying, they are just as incapable of building.” The new cabinet was a minority government , but it turned out to be surprisingly stable.

Compensation with the Hohenzollern

The question of financial compensation with the former ruling houses was in principle a matter for the states. In Prussia, negotiations with the Hohenzollerns failed in 1920 because of the rejection of the SPD parliamentary group in the state parliament and in 1924 because of the objection of the former royal family. In 1925, the Ministry of Finance under Hermann Höpker-Aschoff submitted another draft. This was extremely cheap for the Hohenzollerns and sparked severe criticism from the SPD and DDP. The DDP then introduced a bill in the Reichstag that was supposed to empower the states to find a solution to the exclusion of legal recourse. This was the starting point for a political process that led to the successful referendum and the failed referendum on the expropriation of the princes at the Reich level in 1926.

After the failure of the regulation at the imperial level, the Braun government intensified negotiations with the Hohenzollerns about the assets of the former royal family. In the end there was a compromise that was viewed very critically in the SPD. The main Hohenzollern line received 250,000 acres of land and 15 million Reichsmarks. The Prussian state also got 250,000 acres, plus the royal palaces as well as the Bellevue and Babelsberg palaces , works of art, the coronation insignia, the former royal house library, the archive and the theater. In parliament, the KPD members reacted with indignation, tumult and even violence. The vote went in favor of the agreement. It is noteworthy that not only the communists rejected the bill, but that the MPs of the ruling party SPD either voted against it or did not take part in the vote. Braun had only been able to ensure that no more SPD MPs voted against the law by threatening to resign.

On October 6, 1926, Carl Severing resigned as Minister of the Interior, as had long been agreed with Braun. This made the prime minister the only political heavyweight in the cabinet. Severing's successor was Albert Grzesinski (SPD).

Tensions with the Reich government

There were always tensions between the bourgeois-Christian imperial governments and the center-left government in Prussia. This included factual issues such as the financial equalization between the Reich and the states. Compensation for the financial damage caused by the loss of the territories determined by the Versailles Treaty was still a central point of conflict between the Reich and Prussia. In the area of symbolic politics, which is important for the understanding of the state, the disputes over the flagging on the Constitutional Day in 1927 fell. Braun announced the boycott of those hotels in Berlin that did not use the black, red and gold imperial flags, but the old imperial colors of black and white - Red flags would. He called on the government to participate in the boycott call. The Reich Interior Minister Walter von Keudell (DNVP) protested against the "presumption" of Prussia. The conflict was exacerbated when the Prussian Minister of Education, Becker, restricted the rights of student self-government at Prussian universities. The reason was the ethnic forces that were becoming more and more influential there. When the national student bodies protested against it, Keudell demonstratively stood behind them. Not least because of these and other conflicts with the Reich Minister of the Interior, Braun became an important social democratic figure of integration.

Agricultural policy

The manor districts in Prussia were a relic from the feudal past. Its residents had no municipal housing rights and were still subject to the police force of the landlords. Prepared by Interior Minister Grzesinski, the Braun government abolished the districts in 1927. After all, 12,000 manor districts with a total of 1.5 million residents were affected. However, there were still relics of old conditions in East Elbe. There were still numerous agricultural workers who received part of their wages in kind such as free housing, food or land use. As recently as 1928, 83% of the average farm laborer's income in East Prussia consisted of such deputation wages. This number was somewhat lower in Silesia or Pomerania. Employers preferred this form of pay because it tied workers more closely to them and it was difficult to verify that the wages were correct.

The situation was different in the areas with a predominantly rural population. Nevertheless, reservations about politics in rural regions remained high. This is supported by the emergence of rural protest parties such as the Christian National Peasant and Rural People's Party . In Schleswig-Holstein, which was not dominated by large estates but by farmers, an agrarian protest movement developed with the rural people's movement towards the end of the 1920s.

Educational policy

During the time of the grand coalition, a reform of the school and education system began, initially promoted by the Minister of Education, Carl Heinrich Becker . This included the academization of primary school education. One of the goals was to reduce the educational gap between town and country.

According to the imperial constitution, the primary school teachers should be adapted to those of the higher schools. The design remained a matter for the federal states. Some countries such as Thuringia and Saxony introduced teaching courses at universities or technical universities. Others like Bavaria and Württemberg kept the old seminar solution. In Prussia, a medium solution with denominational educational academies with a shorter training period than in a regular university course was introduced in 1924 .

In Prussia there was an upswing in the promotion of the second education path, especially for talented workers and employees. In 1928 there were 102 secondary schools with 13,000 students. In 1928, a large majority decided to introduce educational grants of 20,000 Reichsmarks for the first time in order to support those with less means. Just one year later, this sum was 100,000 Reichsmarks. However, the further increase was slowed down by fiscal considerations on the part of the SPD.

In other areas it was possible to reduce old deficits. The student-teacher ratio was reduced from 55.22 in 1911 to 38 in 1928. However, demographic development played an important role in this. Fundamentally, the extremely burdensome personnel expenditure in the education sector, in particular, ensured that the politically leading SPD had to temporarily limit education expenditure against its actual goal.

State election 1928

In May 1928, elections were held in Prussia at both the Reich and state levels. The SPD was able to gain in the state elections, while the center and DDP lost votes. Nevertheless, the coalition now had a parliamentary majority with a total of 228 out of 450 seats.

The government stayed the same and Braun promised continuous work. A government project should be the municipal reorganization of the Ruhr area.

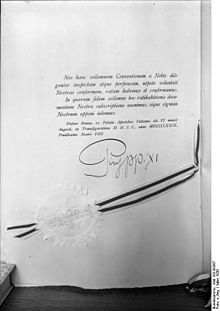

Denominational politics

The thought of the Kulturkampf in royal Prussia was still very much alive, as the election campaign of 1918/19 had shown. But not least because of the strong position of the center in parliament and government, a relatively strong identification of the Catholic population with the new Prussia was achieved. The highlight and a symbol of this was the Concordat between Prussia and the Vatican signed on June 14, 1929 . For this, the document was signed by Eugenio Pacelli (later Pope Pius XII ). The treaty replaced an agreement between the Kingdom of Prussia and the Vatican from 1821. In addition, the last remnants of church legislation from the Kulturkampf time were removed. Among other things, the layout of the dioceses was regulated. This included the reorganization of the dioceses of Aachen and Berlin . Government grants to the church were also regulated. School issues were excluded, but the academic training of the clergy was regulated. The form of the election of bishops and comparable questions were also clarified.

There was opposition to the Concordat from various quarters. The Protestant Church, supported by DNVP and DVP, saw this as a strengthening of the Catholic denomination. The free thinkers in the SPD also rejected the agreement.

While it was possible to win the Catholic population for the new Prussia, this was more difficult with regard to the staunch Protestants. With the revolution, the Protestants of the Prussian Union lost their top leadership with the king. He was officially the highest bishop (" summus episcopus ") of the Union and had far-reaching rights right into the design of the liturgy. Wilhelm II in particular took this task very seriously, and so many Protestants lacked an important guide. It was hardly possible to win Protestantism over to the republican state. A considerable number of staunch Protestants voted for the anti-democratic and nationalist DNVP. It is no coincidence that the motto of the Protestant Church Congress of 1927 was called “People and Fatherland”. Anti-Semitic influences, especially in the theological faculties, also gained in importance.

A church treaty with the Protestant regional churches in Prussia ( Old Prussian Union , Frankfurt / Main , Hanover (Lutheran) , Hanover (reformed) , Hessen-Kassel , Nassau , Schleswig-Holstein as well as Waldeck and Pyrmont ) was only concluded in 1931. On the state side, it was significantly promoted by Adolf Grimme (SPD), who had meanwhile become Minister of Education. Resistance in the church was met by a “political clause” which, similar to the Concordat with the Catholic Church, regulated the state's objection to filling high church positions.

Prussia and the crisis of the republic

Blood May 1929

The Prussian government tried, sometimes with drastic means, to oppose the increasing radicalization from the left and right. In December 1928, after political clashes between Communists , National Socialists and Social Democrats in Berlin , the Berlin Police President Karl Zörgiebel issued a ban on all demonstrations and gatherings in the open air. This ban also applied to May 1, 1929. The KPD did not obey and called for a mass demonstration. Civil war-like fighting broke out between police and communist supporters. Zörgiebel had ordered a tough crackdown and, with the consent of the SPD, was determined to set an example. In total, the fighting - which goes down in history as " Blutmai " - cost 30 lives and almost 200 people were injured. More than 1200 people were arrested. The presumption that the KPD planned the violent overthrow could not be proven. Telegrams from Moscow intercepted later seemed to indicate this. The Prussian government pushed for a ban on the KPD and all of its subsidiary organizations. Severing, who was meanwhile Minister of the Interior, rejected this as unwise and impracticable. Prussia then banned the Red Front Fighters League . With the exception of Braunschweig, the other countries also followed suit.

The events intensified the anti-social democratic stance in the KPD. Ernst Thälmann called the “social fascism” of the SPD a particularly dangerous form of fascism . The KPD's policy should be directed against the “main enemy” SPD.

Bulwark of Democracy

Even after the formation of Heinrich Brüning's presidential cabinet and the Reichstag election of 1930 , which marked the parliamentary breakthrough of the NSDAP, the Prussian government continued to work for democracy and a republic. The ban on uniforms for the NSDAP was not lifted, nor was the provision that civil servants were not allowed to belong to the anti-constitutional parties KPD and NSDAP. During the crisis, Severing returned to the office of Interior Minister in October 1930. He appointed his predecessor Grzesinski as Berlin police chief. Braun, Severing and Heilmann supported the SPD's course of tolerating Brüning due to the lack of political alternatives.

In contrast to the time of the Müller government in the Reich, Brüning temporarily blocked cooperation with Prussia against the NSDAP. In December 1931, the execution of an arrest warrant for Adolf Hitler issued by the Berlin Police President Grzesinski was prevented by the Reich Government. The Prussian government then submitted an extensive dossier to the Reich government, which proved the anti-constitutional activities of the NSDAP. The Braun government then announced a ban on the SA in Prussia. Only after this pressure did Brüning support the ban on all paramilitary units of the NSDAP at the Reich level.

Referendum to dissolve the state parliament

On the part of the National Socialists, Prussia was seen as an important strategic goal for the conquest of power. Joseph Goebbels wrote in 1930: “The key to power in Germany lies in Prussia. Whoever has Prussia also has the Reich. ”Other sections of the right saw it similarly. In 1929 the Braun government banned the steel helmet in Rhineland and Westphalia because of a violation of the demilitarization provisions of the Versailles Treaty. When the Rhineland , which had been occupied since 1918 , was to be evacuated in 1930 after the Young Plan came into force , Reich President Paul von Hindenburg , an honorary member of this anti-republic organization , forced the ban to be lifted with the threat that otherwise he would not take part in the upcoming celebrations in Koblenz. At the end of May 1931, Stahlhelm leader Franz Seldte sharply attacked the “Marxist” Prussian government on the Reichsfrontsoldatentag in Breslau. He announced a referendum for the premature dissolution of the Prussian state parliament . The steel helmet was supported by the DVP, the DNVP and the NSDAP, among others. 5.96 million voters spoke out in favor of the referendum. Even if this was only a little more than the necessary 20%, there was then a referendum on August 9, 1931. Under pressure from Stalin and the Comintern , who at this time considered the fight against the “ social-fascist ” SPD more important than the resistance against the extreme right, the referendum was also supported by the KPD. In particular, because numerous communist voters did not follow this course, the vote failed. Instead of the necessary more than 50%, only 37.1% of the voters came together.

State election 1932

After the Reich presidential election in 1932 , in which Hindenburg, supported by the German State Party, the Center and the SPD, was able to prevail against Hitler and Thälmann, regional elections were due in Prussia and other countries. Since the coalition parties had to assume that the democratic camp would perform poorly in view of the political radicalization, the rules of procedure were changed at the instigation of Ernst Heilmann, the chairman of the SPD parliamentary group. A preliminary form of a constructive vote of no confidence was introduced in order to prevent the prime minister from being voted out by a purely negative majority. From then on, an absolute majority was required for the election of the Prime Minister.

Indeed, the fears were justified. The SPD fell to 21.2%. The DDP (now called the German State Party) shrank to 1.5%, almost insignificant. In contrast, the NSDAP grew from 2.9% to 36.2% and became the strongest parliamentary group with 162 seats. The coalition had lost its majority and together only had 163 seats. The KPD and NSDAP alone now had a negative majority with 219 mandates.

The government then resigned, but remained in office until a new prime minister was elected. There were similar constructions in other countries.

The election of the National Socialist Hanns Kerrl as President of the State Parliament was symbolic of the political change .

The search for a new government capable of holding a majority proved unsuccessful. There were negotiations between the center and the NSDAP. But this solution, which Severing and Braun also considered probable, failed. However, it was also not possible to find a majority to revise the changed rules of procedure. The caretaker government seemed to be able to continue to govern for an indefinite period of time. Especially Ernst Heilmann tried to stabilize this government. He tried to convince the KPD to tolerate the executive government. Since this had in the meantime weakened the social fascism thesis in favor of a united front tactic, this attempt was at least not hopeless from the outset. In the end, it didn't come to that.

Otto Braun had already given up at this time. On June 4, 1932, he handed over his powers to his deputy Hirtsiefer and almost entirely withdrew.

"Prussian strike"

In the background, the Papen cabinet exerted pressure on the swift election of a new prime minister based on cooperation between the NSDAP and the center. There were coalition negotiations; however, the center was not ready to elect a National Socialist Prime Minister. On June 11, the Reich government threatened the appointment of Reich Commissioners for the first time. The occasion was the so-called Altona Blood Sunday of July 17, 1932. In Altona , which belongs to Prussia , violent clashes had broken out between supporters of the KPD, the NSDAP and members of the police. This was the opportunity to implement an emergency decree, which had already been drawn up but not yet dated, with the title “Restoration of public safety and order in the territory of the State of Prussia” on July 20, 1932. Thereafter, the members of the executive Prussian State Ministry were removed from their offices. Papen was appointed Reich Commissioner for Prussia. Franz Bracht became his deputy . When Papen asked Severing whether he would be willing to vacate his post voluntarily, the latter replied “that, given my view of the actions of the Reich Government, I cannot think of voluntarily leaving my office. I will therefore only give way to violence. "

A state of emergency was imposed on Berlin and the province of Brandenburg. The police were placed under the orders of General Gerd von Rundstedt . Senior police officers were arrested. There was no active resistance, such as a general strike by the SPD and the trade unions. The Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold was not mobilized either.

As a result, von Papen and Bracht began removing senior officials and other executives closely related to the parties in the Braun government from their posts. Mostly conservative officials took their place.

The executive government reacted on the day of the Prussian strike with a lawsuit at the State Court in Leipzig . The SPD faction was represented in the Prussian state parliament by Hermann Heller and the Reich government by Carl Schmitt . On October 25, 1932, the state government was right that its repeal was unlawful. The executive government was given the right to represent Prussia before the state parliament, the state council, the imperial council and the other countries. However, the judges ruled that a “temporary” appointment of Reich Commissioners was constitutional. As a result, Prussia actually had two governments: the Braun government without access to the administrative apparatus and the Reichskommissariat, which controlled the actual power resources.

After the de facto dismissal of the Braun government, Joseph Goebbels stated in his diary: “The reds have been eliminated. Your organizations do not resist. [...] The Reds have had their big hour. They'll never come back. "

Beginning of the Nazi era

After the establishment of the Hitler government, Hermann Göring became Reich Commissioner for the Interior for Prussia. In contrast to the previous regulation, the office of Reich Commissioner himself was not taken over by the Reich Chancellor (Hitler) but by the Vice Chancellor, again Franz von Papen. The replacement of politically unacceptable officials has been stepped up. The Prussian police, subordinate to Göring, were an important element in the enforcement of National Socialist rule. For example, the Gestapo emerged from the Prussian political police .

In order to clear the way for the dissolution of the state parliament, Prime Minister Braun was relieved of his office on February 6 by an emergency ordinance. According to the constitution, a committee of three from von Papen, the President of the State Parliament Kerrl and the Chairman of the State Council Adenauer could decide on the dissolution of the State Parliament. Adenauer opposed this and left the negotiations. The remaining members of the college then decided to dissolve it.

On February 17, 1933, Göring issued the “shooting decree”, which allowed ruthless violence to be used against political opponents. The SA , SS and Stahlhelm were appointed "auxiliary police officers". The fire in the Reichstag made it possible not only to suspend numerous basic rights and to intensify the persecution of political opponents with the ordinance for the protection of the people and the state , but also to largely abolish the powers of the state governments.

The new Reich government pushed for the final end of Braun's executive government. In the new election of the Prussian state parliament on March 5, the NSDAP came up with 44.3%. Even if it did not reach the majority, it gained significantly even in Catholic regions. Since the National Socialists did not have a majority in many cities, even in the local elections on March 12, 1933, despite the growth, they took power through political manipulation. With the Prussian Municipal Constitutional Law of December 15, 1933, the elected municipal parliaments were replaced by appointed municipal councils.

The new Prussian Landtag was constituted on March 22, 1933. As in the Reich, the mandates of the Communist MPs were revoked and many of them were arrested. This gave the NSDAP an absolute majority. The state parliament confirmed the removal of the Braun government, which then officially resigned. The state parliament decided not to elect a new prime minister. With the laws for the synchronization of the federal states of March 31 and April 7, 1933, Prussia was also subordinated to the Reich. On April 11th, Goering was appointed Prussian Prime Minister by Hitler. The state parliament met for the last time on May 18, 1933. He approved an enabling law that passed the legislative right to the State Ministry. Only the SPD refused. This meant the final end of the democratic system in Prussia.

Agony and end

The National Socialists immediately began to reinterpret Prussia in their own way. This enabled them to tie in with tendencies in the right-wing political spectrum of the 1920s, in which the Prussians of Frederick II and the Prussians of Otto von Bismarck and their “Prussian socialism” were used against liberalism and social democracy. The opening of the newly elected Reichstag was staged symbolically by Goebbels on March 21, 1933 as the Potsdam Day as the reconciliation of the National Socialist state with the old Prussia. Behind this was also the goal of pulling the old elites to the side of the new regime. The new rulers did not seriously consider restoring the monarchy, as had been hoped for by many.