East Prussia

| flag | coat of arms |

|---|---|

|

|

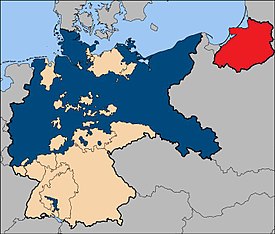

| Situation in Prussia | |

1871–1918 *: *) East Prussia red, rest of the Prussian state blue 1922–1939 *: *) East Prussia red, rest of the Free State of Prussia blue  |

|

| Consist | 1773-1829 1878-1945 |

| Provincial capital | Koenigsberg (Pr) |

| surface | 37,002 km² (1910) 36,992 km² (1938) |

| Residents | 2,488,122 (1939) |

| Population density | 67 inhabitants / km² (1939) |

| License Plate | IC |

| Arose from | Duchy of Prussia |

| Today part of |

Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship Kaliningrad Oblast Klaipėda District Tauragė District |

| map | |

|

|

East Prussia has been a name for the easternmost part of Prussia since the 18th century . From 1815 to 1829 and from 1878 to 1945 East Prussia was the name of the easternmost Prussian province . It covered a large part of the historical Prussian landscape . The geographical name "Eastern Prussia" is much older.

The original landscape of Prussia was the home of the Baltic Prussians . By orders of the Emperor and the Pope to Christianity and thus commissioned conquest of the country by the Teutonic Order in the 13th century was the German Teutonic Knights , whose territory was known as the "Prussia".

Due to the Second Peace of Toruń , only the eastern part of Prussia remained in 1466 under the Order (Prussia orientalis) , while the Bishopric of Warmia (Warmia) and the renegade western part ( Prussia occidentalis ) were autonomous and under the authority of the Polish king ( personal union ). In the course of the Reformation , the eastern part became the first Protestant state in Europe under the suzerainty of the Polish king under the last Grand Master of the Teutonic Order in Prussia, Albrecht von Prussia , in 1525 as the Duchy of Prussia .

Due to the dynastic union with the Electorate of Brandenburg in 1618, it was also called Brandenburg Prussia . In the Treaty of Wehlau in 1657, the King of Poland gave his suzerainty rights over the Duchy of Prussia to the Elector of Brandenburg and his descendants, who thereby became sovereign dukes in Prussia . In 1701, Elector Friedrich III crowned himself in the capital Königsberg . as Frederick I as king in Prussia . In the course of the 18th century, the name “Prussia” was transferred to the entire state of the Hohenzollerns in their capacity as kings of Prussia and electors of Brandenburg within and outside the Holy Roman Empire .

After the first partition of Poland , King Frederick II of Prussia decreed in 1772 that the previous province of Prussia, expanded to include the Warmia, should receive the previous Latin name Prussia Orientalis , in German translation East Prussia , after the unification of all lands of Prussia , and that the annexed Polish- Prussia the name West Prussia . Both provinces and the Netzedistrikt formed the Kingdom of Prussia between 1772 and 1793 in the Prussian monarchy .

From 1829 to 1878 East and West Prussia were united to form the Province of Prussia , which after the founding of the North German Confederation in 1867 and the founding of the Empire in 1871 formed its northernmost and easternmost territory. After the Peace Treaty of Versailles in 1919, which ended the First World War , East Prussia was territorially separated from the rest of Germany between 1920 and 1939 by the “ Polish Corridor ”.

The Potsdam Agreement brought northern East Prussia, including the provincial capital Königsberg, under provisional administration by the Soviet Union after the end of World War II, and southern East Prussia under Polish administration. A final settlement was reserved for an all-German peace treaty. De facto , East Prussia was administratively incorporated into the People's Republic of Poland or the USSR, contrary to international law , with Poles and Soviet citizens taking the place of the almost completely displaced population .

The GDR recognized the border with Poland as early as 1950, the Federal Republic of Germany initially indirectly in 1972. In the two-plus-four treaty and the German-Polish border treaty of 1990, the contracting parties declared the external borders of the German Democratic Republic and the Federal Republic of Germany to be final for unified Germany. This means that the southern part of the former easternmost part of Germany also belongs to Poland under international law and the northern part as an exclave to today's Russia (then still the USSR).

geography

The historic East Prussia stretches along the Baltic coast from the Vistula River Delta to the north of the Memel mouth at Memel / Klaipeda , where at Hungry "the kingdom has its end". The Memelland , north of the lower Memel on the Curonian Lagoon , was separated from East Prussia by the League of Nations in 1920 , was annexed by Lithuania from 1923 to the beginning of 1939 and has been part of Lithuania again since the end of the war. The northern part (about 35%) of the rest of East Prussia is today the Russian Kaliningrad Oblast , the southern part (about 65%) the Polish Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship . In May 1939, East Prussia, including the Memelland, comprised 39,840 km² with 2,649,017 inhabitants. It was relatively sparsely populated with 66.5 inhabitants per km². At that time 372,000 inhabitants lived in the capital Königsberg.

The landscape of northern East Prussia is of slightly wavy plains with glacial hills , mostly quilted meadows and fields as well as much forest determines that of wide river plains is interrupted and marshes. The largest rivers are the Pregel and Memel , other rivers are the Łyna and Lawa (Alle) , the Angrapa (Angerapp) , the Krasnaja (Rominte) and the Dejma (Deime) . In the north of the oblast - bordering the Curonian Lagoon - there is the elk lowland (Losinaja Dolina) and the Great Moosbruch , a moorland that has been partially drained.

In the southeast lies the Rominter Heide with the Wystiter See and the Wystiter Hügelland . Large parts of the sparsely populated landscape in southern East Prussia are shaped by the Masurian Lake District . In the west, the Samland juts out into the Baltic Sea as a peninsula . In the southwest lies the Fresh Lagoon . East Prussia had a share in the Curonian and the Fresh Spit .

Large parts of the soil belong to soil classes 4 and 5. As raw materials, sand and gravel are interesting for the building industry and loam, peat and clay for the ceramic industry. About 30 percent of the area is covered by forests.

Due to the low population density (66.5 inhabitants per km²), many animals that were already extinct in the rest of what was then Germany were able to survive in East Prussia. In 1945 there was a population of elks and wolves in East Prussia . The many storks in East Prussia are still noticeable today (2012) , which already says important things about the landforms and their management there.

history

Early history

Archaeological finds testify to human settlement on the south coast of the Baltic Sea after the end of the Ice Age (in Lithuania, for example, the glaciation ended around 16,000 BC), for example in the Allerød Interstadial (11th millennium BC). In the end Mesolithic both Neman- and are Narva culture represented. In the Neolithic, the Haffküsten culture , a group of corded ceramics , is proven. In the early Iron Age (6th - 1st century BC) lived in the area between Warmia and Memel, the bearers of the West Baltic barrow culture .

Between Braunswalde and Willenberg near Marienburg an Iron Age burial ground with around 3000 graves was found in 1873 . The Braunswalde-Willenberg finds named after this site, today also known as the Wielbark culture , are characterized by a mixture of Scandinavian and continental elements and are generally regarded as a sign of the immigration of the Goths . Only the extreme west of East Prussia belonged to their area of distribution. The Goths came to the area around the lower Vistula in the last century before the turn of the Christian era , but migrated to the southeast from around 200 AD.

In the rest of East Prussia, the archaeological West Baltic culture had been widespread since the 1st century AD , with the Olsztyn Group , the Sudauer Group , the Dollkeim Group and the Memelland Group . At the latest, the bearers of this culture must be viewed as Baltic groups.

98 AD Tacitus reported in his Germania about the people of the Aesti gentes . In all likelihood, these were the predecessors of the West Baltic tribes known as Prussians from the 9th century onwards .

In the 2nd century, Claudius Ptolemy mentioned the Galindoi and Sudinoi tribes , who probably inhabited the western (Olsztyn group) and the eastern part (Sudauer group) of the later East Prussian area.

In his Getica , written around 550, the Gothic historian Jordanes counts the Aesti to the Gothic Empire, which until about 375 had been north of the Black Sea .

A people named Pruzzi was first mentioned in the 9th century by a chronicler known as a Bavarian geographer .

The Anglo-Saxon Wulfstan traveled to the Baltic countries in the 10th century. In his report he distinguished the "Witland" east of the Vistula from the land of the Winoten west of the river and called its inhabitants, like the ancient authors, "“stas".

The East Baltic Lithuanians were first described in the 11th century. But only with the time of Christianization and the associated written culture did one begin to keep written documents containing detailed information.

The Prussia Collection was the most important collection of archaeological finds.

- Prussian tribal areas

- Beards

- Warmia

- Needy

- Natangen

- Pogesania

- Pomesania

- Samland

- Galinden

- Schalauen

- Sudauen

- Löbauer Land (Lubawa)

- Sassen

- Baltic-Slavic border areas

State formation

The tribal land of the Prussians (Pruzzen) lay on the Baltic Sea coast, northeast of what would later become Poland and southwest of Lithuania . To the north it stretched to the Lower Memel , and to the west to the Lower Vistula, both rivers probably not forming a sharp settlement boundary. There are also reports of Baltic settlements in the Kulmerland and linguists refer to river and place names west of the Vistula as far as the Persante as well as to words of Baltic origin in the Kashubian language .

The area on the Baltic coast, populated by Baltic tribes, has been a sphere of interest for the Christian states emerging in the region since the 10th century. All efforts to conquer the area were also under the pretext of proselytizing . The emperors of the Holy Roman Empire , the most powerful secular rulers of the West in the High Middle Ages , laid claim to non-Christianized areas. For example, Emperor Friedrich II in the gold bull of Rimini in 1226 to the Teutonic Order .

The attempts of the Polish rulers to extend their power to the Baltic coast, which is still inhabited by pagans , were only successful in Pomerania . His autobiography Vita Sancti Adalberti reports on one of these advances, in which the mission bishop Adalbert of Prague advanced to the area east of Gdansk on behalf of Bolesław I in 997 .

Konrad , the Duke of Mazovia , suffered severe setbacks against the Prussians. According to the Older Olivachronik, the Kulmerland, which was largely inhabited by Poland, was devastated by Prussia , according to the chronicle of Peter von Dusburg . The Prussian advances even threatened his power base Mazovia. The first Bishop of Prussia was appointed in 1209: The Cistercian Christian von Oliva , previously abbot of Łękno , took his seat in 1215 in the Oliva Monastery , which had been founded 30 years earlier , outside Prussia in the Duchy of Pomerania of the Samborids . His Christianization efforts were initially not of lasting success. The order of knights called Milites Christi Prussiae , usually called the Order of Dobrin , established by Konrad I and Bishop Christian , was able to secure Mazovia, but not establish rule over Prussia.

Teutonic Order State

Duke Konrad von Mazowien asked the Teutonic Knights Order for military support in the fight against the Prussians and offered him land rights in return. In 1224 Wilhelm von Modena was named legate for Prussia and Samland by the Pope. The order had the land rights for the area to be conquered guaranteed in 1226 by the Roman-German Emperor Friedrich II and in 1230 by Konrad von Masowien in the Treaty of Kruschwitz . This is now seen as a dictation of the order, if not a forgery. In 1231 the order founded the later city of Thorn . Pope Gregory IX 1234 certified the order in the Bull of Rieti that its conquests should only be subject to the church, but not to any secular fiefdom.

The order conquered the country with troops composed of European nobles in crusades. He secured his conquests by building castles and, with the help of locators , brought German settlers into the country, part of the German colonization in the east . Numerous cities and villages were founded. The disagreements about the land distribution between the order and Bishop Christian were brought up to the Pope. In 1245 the papal legate Wilhelm von Modena divided the Prussia into four dioceses . The four dioceses were subordinate to the Archbishop of Riga . However, it was not until 1283 that the pagan Prussians were finally conquered.

In 1309, the Teutonic Order also conquered the Christian Pomerania with Danzig, which the last Duke, Mestwin II , had promised to return to Poland after a temporary apostasy, beyond the contractually agreed area . This conquest was recognized by Poland in the Treaty of Kalisch (1343) . The border with Lithuania, which was consolidated as a state in the resistance against the order, was not permanently established until the Peace of Lake Melno in 1422 . The seat of the order was initially Venice , then since 1309 the Marienburg in Prussia, which was named after the Mother of God, the patron saint of the Teutonic Order.

In addition to the conflicts between the Order and Poland over the expansion of territorial rule, there were conflicts with the cities in its area in the 15th century because of its attempts to attract lucrative trade. This led to armed conflicts in which the Teutonic Order was on one side, the Prussian cities and the Kingdom of Poland on the other.

After his defeat in the Battle of Tannenberg in 1410, the religious state was weakened. In the First Peace of Thorner in 1411 and in the Peace of Lake Melno in 1422 he had to give up rule and claims to Samaites . The Peace of Brest in 1435 precluded any claims by third parties (especially the Holy Roman Empire) on the land of the Order. After the West Prussian estates had organized themselves in the Prussian Confederation and submitted to the King of Poland in 1454, the Thirteen Years War broke out , which ended in 1466 with the Second Peace of Thorne . The Teutonic Order had to cede the Kulmerland, Warmia, Pogesanien and Pomerellen to the Polish crown. These areas were henceforth referred to as Royal Prussia or Prussia Royal Share . Since the Marienburg order castle, which had been conquered in 1457, had to be ceded, the seat of the order was moved to Königsberg . The order was also obliged to take oath of allegiance and military service to the Polish king.

In 1511 Albrecht of Prussia became Grand Master of the Teutonic Order. At first he refused the oath of allegiance to the Polish king. In 1515, Emperor Maximilian I concluded defense and marriage alliances with the Jagiellonians at the Princely Congress of Vienna and finally recognized the resolutions of the Peace of Thorne, after they had been rejected by the Emperor and Pope.

Duchy of Prussia

After he was denied support in the four-year equestrian war , Grand Master Albrecht distanced himself from the emperor. He made peace with Poland, introduced the Reformation in 1525 and made the religious state the secular Duchy of Prussia . He had the hereditary ducal dignity confirmed by the Polish King Sigismund I , recognizing the Polish feudal sovereignty .

The secularization of the Prussian monastic state was not recognized by the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation . The representatives of the Teutonic Order in the Reich elected a new Grand Master, Walther von Cronberg , who did not take his seat in Koenigsberg as before, but in Mergentheim . In 1527 Cronberg received the authorization from the emperor to call himself "Administrator of the High Mastery". At the Reichstag in Augsburg in 1530 , this was enfeoffed with the rights of the Teutonic Order and the state of Prussia. This decision was of no consequence in practice. The secular influence of Cronberg effectively ended at the borders of the Balleien within the empire. Maximilian III , the son of Emperor Maximilian II , held the title of administrator of Prussia until 1618 . After that, the office was called Hoch- und Deutschmeister . The high and German masters of the Teutonic Order, who had no sovereignty in Prussia, had the same status in the Holy Roman Empire as a prince-bishop through the Kaiser since 1526 . In 1531/34 Duke Albrecht was put under a ban, which however remained ineffective.

In 1525 Albrecht created a territorial division that lasted until 1722. The duchy was now divided into three districts of the size of later administrative districts: Samland, Natangen and Oberland. The previous order commanderies became the main offices in the shape of later districts. In each main office there were several offices, some of which were chamber offices, some of which were again called Kreis (Creyß), which was misunderstood. These offices were responsible for the economy and legal affairs of the unfree peasants. The lowest administrative division were the districts, which were sometimes also called villages, although they usually comprised several settlements.

In 1544, Duke Albrecht founded the University of Albertus in Königsberg. The cultural achievements during his tenure were the Prutenic Tables , the creation of Prussian maps and a coin reform that brought about a harmonization of the coins (practically a monetary union) of the duchy with the coins of Prussian royal share and Poland-Lithuania . During this time, Protestant refugees were accepted and, in particular, the first translations of religious scriptures into different languages by the new Prussian citizens from neighboring countries.

After Duke Albrecht's death in 1568, his fifteen-year-old son Albrecht Friedrich came to power. Because of his mental illness, the Polish King Stephan Báthory appointed the Ansbach Hohenzollern Georg Friedrich as administrator of Prussia in 1577 ; he was followed in 1605 by Joachim Friedrich, the first elector of Brandenburg , then in 1608 by Johann Sigismund , Albrecht's son-in-law.

Personal union with Brandenburg

When Albrecht Friedrich died childless in 1618, the Duchy of Prussia fell to the Brandenburg line of the Hohenzollern in 1618, at that time under Johann Sigismund. This united the Electorate of Brandenburg and the Duchy of Prussia in a personal union . Now the Duchy of Prussia was also called Brandenburg Prussia and was often referred to as a principality until 1701 (as in church registers before 1700). In the Treaty of Wehlau in 1657, Poland renounced feudal sovereignty over the Duchy of Prussia. In contrast to their Brandenburg territories in the Holy Roman Empire, the Electors of Brandenburg had full sovereignty here .

In the Prussian state

The Brandenburg Elector Friedrich III used the sovereignty . in order to crown himself in Königsberg in 1701 as Friedrich I "King in Prussia". In a status survey , he raised his Duchy of Prussia to the Kingdom of Prussia .

During the plague epidemic of 1709/10 , around 240,000 inhabitants of East Prussia died, 150,000 of which were in the eastern offices of Insterburg , Ragnit , Tilsit and Memel . 10,834 farms were no longer cultivated, around 60,000 kulmische hooves lay fallow. In the following years, this region was resettled by settlers from Switzerland , the Palatinate , Nassau , Hesse and the Magdeburg region , and in particular from 1732 onwards, around 12,000 Salzburg exiles were settled.

In 1722 a new territorial division was created, which lasted until 1808: Two chamber departments were created that were directly subordinate to the General Directorate in Berlin, the East Prussian or German Domain Chamber in Königsberg and the Littauian Domain Chamber in Gumbinnen . In both districts there were immediate cities, media cities, domain offices and noble estates. For more effective management of income and the march and were Einquartierungsaufgaben for Immediatstädte that namely own Justice and Kameral departments had steuerrätliche circles and for the other cities and the "open country" landrätliche circles decorated.

During the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), Russian troops conquered the Kingdom of Prussia (East Prussia) in 1757. Prussia's representatives paid homage to the Russian Empress Elisabeth . Elisabeth's successor Peter III. gave it back to the King of Prussia in the Peace of St. Petersburg in 1762.

In 1772, the Warmia, which had previously been under Polish sovereignty, was divided into several districts and these were subordinated to the Königsberg chamber department, while the westernmost Old Prussian districts were subordinated to the newly created Marienwerder chamber department .

From 1422 to 1945 Schirwindt was the easternmost outpost of Prussia and Germany.

- German Chamber of Commerce (1722–1808)

- Brandenburg district

- Neidenburg circle

- Rastenburg Circle

- Samland County

- Tapiau circle

- German Chamber of Commerce (1722–1772)

- Eylauer Kreis or inheritance

- Marienwerderscher Kreis

- Riesenburg Circle

- Inheritance Schönberg

- German Chamber of Commerce (1772–1808)

- Braunsberg Circle

- Heilsberg Circle

- Mohrungen Circle

- Lithuanian Chamber of Commerce (1722–1808)

- Gumbinn's circle

- Insterburg District

- Memel district

- Olezkoe Circle

- Ragnit's circle

- Sehestenscher Kreis (forerunner of the later district of Sensburg and today's Powiat Mrągowski )

- Tilsitsch circle

During the first partition of Poland in 1772, Prussia acquired Polish Prussia under Frederick II , which became West Prussia . The territory of the Duchy of Warmia merged with the previous "Kingdom", which was given the name East Prussia on January 31, 1773 in an administrative act . Between 1773 and 1792 the “Kingdom of Prussia” consisted of the provinces of West and East Prussia and the Netzedistrikt . The capital of East Prussia was Königsberg until the end of World War II . From 1824 to 1829 East and West Prussia were united in terms of personnel and administratively from 1829 to 1878 in one province . In 1878 this was divided again.

During the Prussian administrative reform from 1815 to 1818, an administrative division was created that essentially lasted until 1905. Now Memel (today Klaipėda) belonged to the Königsberg administrative district.

Agriculture, especially arable farming , remained the main livelihood of the East Prussian population in the 19th century. In the second half of the 19th century, a growing number of later-born East Prussian peasant sons and farm workers began to migrate to the industrial areas in Silesia and Saxony (so-called "Sachsengangserei"), as well as to the Ruhr area. In some places this led to a lack of workers during the harvest season and seasonal workers to be recruited from Congress Poland . The only industrial cities in East Prussia were Königsberg, Elbing (provided that the city of East Prussia is included, which was controversial until 1918) and Insterburg .

First World War

Due to its common border with the Russian Empire and its advanced geographical position in East Prussia was the First World War at a crucial scene of the eastern front ; here were the only areas of the German Empire that were occupied by foreign troops during the World War. Fighting also took place in small areas in the realm of Alsace-Lorraine . The costly battles on the Western Front took place on French and Belgian territory.

The Russian advance was halted in the second battle of Tannenberg . The responsible generals Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff laid the basis for their great popularity, which they used in different ways during the Weimar Republic : Hindenburg as the conservative Reich President , Ludendorff as a putschist and ally of Adolf Hitler .

At the beginning of the war, Ludwig von Windheim was senior president in East Prussia. Ailing and unable to cope with the war, he was replaced at the urging of the military. He was succeeded by Adolf von Batocki , who was described as the "father of the country" because of his services to the reconstruction. Only Konigsberg and five districts were spared from the brief Russian occupation of East Prussia. The damage was enormous: 39 cities and around 1900 villages were devastated. 1,491 civilians were killed during the Russian occupation, for example 65 civilians were shot by Russian troops in the Abschwangen massacre . 2,713 civilians were deported from the Masurian districts of East Prussia alone. The German War Damage Commission put the property damage at 1.5 billion gold marks. In the middle of the war, a large-scale private aid campaign began alongside state aid for reconstruction. The “East Prussian Aid ” - not to be confused with Eastern Aid (German Reich) - was the umbrella organization of the last 61 sponsorship associations throughout the Reich. By October 1914, the state had already paid 400 million marks in advance, and by October 1916 a total of 625 million marks. War Aid Associations helped rebuild East Prussia until the mid-1920s.

the Versailles Treaty

The Peace Treaty of Versailles , which came into force on January 10, 1920, caused indignation and national excitement among the residents of East Prussia . The treaty placed the East Prussian area east of the Memel (" Memelland ") under Allied administration and most of the former province of West Prussia was ceded to the newly founded Polish state without a referendum . With the Polish Corridor thus created , East Prussia was separated from the rest of the empire and became an exclave . The Vistula Delta was assigned to the Free City of Gdansk , created under the League of Nations mandate , which had independent state institutions but was economically and militarily linked to Poland. The new border in the area of the Vistula was perceived as particularly absurd, where the border did not run in the middle of the river, as is usually the case internationally, but on the right bank of the river, so that the residents of the neighboring districts were unable to use the river. The sometimes harassing behavior of Polish border officials on the Vistula and crossing the corridor caused outrage on the German side. The southwestern part of the East Prussian district of Neidenburg had to be ceded to Poland without a referendum , mainly because the main town of Soldau ( Działdowo ) as a railway junction with connections enabled direct traffic between Warsaw and Gdansk (→ Marienburg-Mlawka Railway ). From this the new powiat Działdowo (Soldau district) was formed, which was attached to the Polish Pomeranian Voivodeship .

The Inter-Allied Military Control Commission carried out the disarmament and disarmament, so that the residents of East Prussia felt defenseless against a hostile Poland.

Referendums on July 11, 1920

The newly formed Second Polish Republic laid claim to southern East Prussia and the West Prussian areas east of the Vistula, because a significant part of the population spoke Polish or Masurian , a Polish dialect, as their mother tongue .

At the urging of the Ebert government and with the intercession of British Prime Minister David Lloyd George , the victorious powers agreed to a referendum in the disputed areas in the Versailles Treaty . In the vote carried out under the supervision of the League of Nations on July 11, 1920 in the Allenstein voting area, 97.90% voted to remain with East Prussia and thus to belong to Germany. Only 2.10% voted for annexation to Poland. In the vote held at the same time in the West Prussian voting area of Marienwerder, 92.36% voted for annexation to East Prussia and thus to remain with the German Reich . 7.64% voted for annexation to Poland. The area in the province of East Prussia became the administrative district of West Prussia with the administrative seat Marienwerder .

Interwar period

In Article 89 of the Versailles Treaty, the German Empire guaranteed unhindered passage to East Prussia. The right of passage for the railroad was first specified in a provisional agreement at the end of 1920, which was replaced by a final agreement on April 21, 1921. However, land traffic between the German heartland and the province of East Prussia was problematic. Rail traffic was carried out with sealed trains, on which the windows were hung up in the first few years and were not allowed to be opened. From the end of the 1920s, the restrictive provisions were gradually relaxed. In 1939 nine daily and two seasonal pairs of express trains and around 20 pairs of freight trains served traffic to and from East Prussia. Road traffic, for which fixed transit roads were designated and visa and road usage fees were levied by Poland, was repeatedly impaired. In 1922, the Reich Ministry of Transport set up the East Prussian Sea Service , which established a connection between East Prussia and the heart of the German Reich by bypassing Polish controls. The East Prussian sea service existed until 1939.

The relationship between the Weimar Republic and Poland was generally tense in the interwar period . In the first few years in particular, there were disputes along the common border, including the use of weapons. In the Weimar Republic, the separation of East Prussia was viewed by all parties as unjust and a violation of the right to self-determination. Reich Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann therefore never responded to the various Polish proposals to conclude an "East Locarno" analogous to the Locarno Treaties and to declare the border with Poland inviolable.

In the last Reichstag election in March 1933, before the general ban on political parties , the NSDAP in East Prussia achieved the largest share of the vote in a constituency of the German Reich with 56.5%. Together with the votes of the DNVP , the East Prussians who were eligible to vote voted 67.8% for right-wing extremist parties. The second highest value, which was only exceeded by the constituency Pomerania (with 73.3%). For comparison: In the constituency of Cologne-Aachen, all right-wing extremist parties achieved 35.7%. As in the other Prussian eastern provinces, many voters were strongly impressed by the day in Potsdam , when the National Socialists had given many the impression that they wanted to revive old Prussia.

Erich Koch , who came from the Rhineland , became the Gauleiter and thus the actual local ruler in East Prussia . In 1939 , the Western powers, who had previously shown compliance with Hitler's revision drive as part of the appeasement policy, signaled intransigence and threatened war with the German demands for the reconnection of Danzig and the return of the corridor .

Second World War

conquest

Barely six months later began the invasion of Poland of the Second World War . After the rapid occupation of the country, other parts of Poland were annexed in addition to the Prussian provinces of West Prussia and Posen , which had been ceded 20 years earlier . In 1939 a new administrative district Zichenau was formed there, which was assigned to the province of East Prussia. Furthermore, the new district of Sudauen became a province, while the former West Prussian areas around Elbing and Marienwerder fell to the new Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia . The areas newly annexed to East Prussia, however, were ethnically practically purely Polish areas, which historically had never been in closer contact with East Prussia (apart from a short episode after the Polish partitions). Immediately after the occupation, the considerable Jewish population was hit by the National Socialist repression and later by the mass extermination measures ( resettlement in ghettos , " extermination through work " and deportation to extermination camps ).

Towards the end of the Second World War East Prussia was conquered by the Red Army after heavy fighting in the Battle of East Prussia . The National Socialist Gauleitung led by Gauleiter Erich Koch failed to evacuate the population in good time and placed independent escape movements under severe punishment. Similar soldiers in senseless "to the last man" of positioning and battles of encirclement were burned rather than allowed to withdraw ordered the rulers thus made directly complicit in the deaths of countless German civilians who could have been saved.

Escape and evacuation

When the front of the Second World War reached East Prussia, the evacuation was initially hindered or prevented by the military and the state apparatus (among other things by ordinances ), then at the last minute (January 1945) under the worst possible conditions (deepest winter, constriction of the land route) disordered began. As a result, a large part of the civilian population was directly exposed to fighting.

Part of the population was able to escape to the west by land with horse-drawn carts (which pulled in refugee routes). But after the Red Army had reached the Fresh Lagoon near Elbing in the course of the Battle of East Prussia , the overland route was cut off. Thousands drowned while fleeing over the ice to the supposedly saving Fresh Spit , on which the way to the coast led in the direction of Gdansk, or fell victim to fighter planes without any cover and aimed at the treks. Another part was evacuated via the Baltic Sea (especially via the port of Pillau ). The evacuation was initiated on January 21, 1945 by Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz ; the measure was later named company Hannibal .

Overall, the escape under war conditions resulted in many deaths, mostly in winter. It is estimated that of the 2.4 million residents of East Prussia at the end of the war, around 300,000 perished in miserable conditions while fleeing. Among the people who died in the sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff , the General von Steuben and the Goya in the spring of 1945, there were also many refugees from East Prussia, several thousand per ship.

War crimes against the German civilian population

Residents still present, refugees caught up by the advance of the Red Army, or residents returning after the (sometimes temporary) end of the fighting were often mistreated, raped and killed by Soviet soldiers or taken for forced labor in the Soviet Union . The Nemmersdorf massacre in October 1944, when Russian troops advanced into East Prussia for the first time since August 1914, should be mentioned in this context . As members of the Red Army, Alexander Solzhenitsyn ( East Prussian Nights ) and Lev Kopelew were eyewitnesses and later referred to these and other Soviet war crimes as dissidents (e.g. the mass shootings of Polish officers in the Katyn massacre ). With regard to the global political situation, those responsible were not called to account, either internationally or in the Soviet Union.

expulsion

The residents of East Prussia are from 1945 to 1947 more than 90% from their home in occupied Germany west of the Oder-Neisse line marketed Service. In the southern part, Polish authorities subjected the remaining residents to a “national verification” based on ethnic criteria. People classified as "Germans" were expelled, while " autochthons " - that is, members of what the Polish authorities believed was an ancestral Slavic population - were allowed to stay. A Polish-sounding surname or Masurian or Polish language skills within the family were sufficient for classification as “autochthonous” . Skilled workers were also given the right to stay in order to be able to put factories back into operation.

By October 1946, 70,798 people had been "verified" in this form, i. H. became Polish citizens, 34,353 remained “unverified”. In the area of Mrągowo (Sensburg) in particular , many residents refused this verification process; in the spring of 1946, 20,580 out of 28,280 people were not “verified” here, and in October 16,385 people remained without Polish citizenship. The naturalized "autochthons" were still regarded as Germans and subjected to discrimination because of their predominantly Protestant faith and their often rudimentary language skills . In February 1949, the former head of the Stalinist secret police Urząd Bezpieczeństwa (UB) of Lodz , Mieczysław Moczar , became voivode of Olsztyn. A final “verification action”, characterized by brutal torture and violence, began, after which only 166 Masurians were not “verified”.

A total of around 160,000 pre-war residents remained in southern East Prussia, the vast majority of whom left the country as late repatriates in the following decades . Northern East Prussia fell to the Russian Soviet Republic and, as the Kaliningrad Oblast, became a restricted military area into which even Soviet citizens could only enter with a special permit.

Potsdam Agreement

Reorganization

After the Potsdam Agreement , East Prussia was divided between the People's Republic of Poland and the Soviet Union, subject to a final peace settlement (→ Two-Plus-Four Treaty ) . The northern area around Königsberg was then annexed by the Russian Soviet Republic . It was predominantly settled with Russians from Central Russia and the area of today's Volga Federal District, as well as with Belarusians and Ukrainians . The Polish portion was divided between the newly established Gdańsk , Olsztyn and Suwałki voivodeships . Mainly Poles from central Poland and Ukrainians expelled from south-east Poland as part of the Vistula campaign were settled here. The capital of Königsberg in 1946 in honor of Soviet politician Mikhail Kalinin in Kaliningrad renamed; Likewise, all places in the Soviet part were renamed, unless they were dissolved or combined into larger units.

Recognition of the demarcation

In 1950, the German Democratic Republic (GDR) recognized the Oder-Neisse Line in the Görlitz Treaty with the People's Republic of Poland as the “state border between Germany and Poland”. This recognition was often denied that it was legally binding under international law . The Federal Republic of Germany , which raised the claim to sole representation for Germany as a whole and all Germans, i.e. until the beginning of the 1970s also for the territory of the GDR, under Federal Chancellor Willy Brandt pursued the recognition of the demarcation of the border subject to a final peace treaty as part of the " New Ostpolitik " ( → Eastern Treaties ). At the time of the "two-plus-four" talks in Moscow, Joachim von Arnim, head of the political department of the German embassy, is supposed to respond in a conversation to the Soviet Major General Geli Batenin , who had signaled the Soviet Union's interest in negotiations on East Prussia have that the negotiations were only about "the Federal Republic of Germany, the GDR and all of Berlin". Following the accession of the GDR to the Federal Republic and the formation of the new states , the now sovereign Germany gave up all territorial claims outside the Federal Republic on November 14, 1990 with the German-Polish border treaty . When it came into force in 1992 at the latest, German territorial claims to the former German eastern territories , and thus also to East Prussia, were completely extinguished and the borders were finally recognized.

Todays situation

After the administrative reform in 1975, Polish East Prussia was divided into new voivodships : Elbląg and Olsztyn and parts of Ciechanów and Suwałki . After another administrative reform on January 1, 1999 in the southern part of Poland, this area has since formed almost in its entirety the Warmia-Masurian Voivodeship with the capital Olsztyn ; the former Northeast Prussia today forms the Russian Oblast Kaliningrad with the capital Kaliningrad . After the dissolution of the Soviet Union , this region is now an exclave of the Russian Federation. Some Russian residents call the city today "Kjonigsberg", "Kenig" or "Kenigsberg". A renaming (as with Saint Petersburg , Nizhny Novgorod and Tver ) was rejected in a referendum in 1993.

Population development

| year | Residents |

|---|---|

| 1875 | 1,856,421 |

| 1880 | 1,933,936 |

| 1890 | 1,958,663 |

| 1900 | 1,996,626 |

| 1910 | 2,064,175 |

| 1925 | 2,256,349 |

| 1933 | 2,333,301 |

| 1939 | 2,488,122 |

Administrative division of the province of East Prussia

In the period from 1878 to 1945, the territorial administrative structure within the predominantly agriculturally structured province of East Prussia changed only gradually. However, in 1920 and 1939 the external borders were changed considerably.

Administrative districts

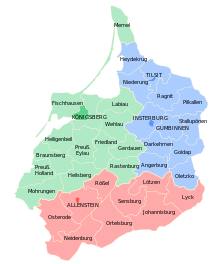

The two administrative districts of Gumbinnen and Königsberg existed from 1808 to 1945 . On November 1, 1905, the new district of Allenstein emerged from the southern districts of these districts . 1723-1808 these districts were called War and Domain Chamber -Department of Lithuania and East Prussia.

After the establishment of the Polish corridor , the former West Prussian administrative district of Marienwerder was partially annexed to the province of East Prussia on July 1, 1922 , together with some districts from the former administrative district of Danzig ( Elbing and Marienburg ) as the administrative district of West Prussia with its seat in Marienwerder. In October 1939 annexed Polish territories were added and again assigned to the new Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia as the Marienwerder administrative district .

On October 26, 1939, the new administrative district of Zichenau (Ciechanów) was incorporated into the East Prussia province from other Polish areas . The district of Bialystok , which was not formally incorporated into East Prussia and formed on August 1, 1941 from the areas of the Belarusian Soviet Republic , which had belonged to Poland until 1939, was administered by the East Prussian Upper President and Gauleiter Erich Koch, as head of civil administration, in fact like an area of the Reich .

City districts

In addition to the Königsberg i. In the course of time, the following further urban districts emerged: The towns of Tilsit (1896), Insterburg (1901), Allenstein (1910) and Memel (1918) were separated from their districts and formed their own urban districts. The West Prussian Elbing had been a district since 1874 and belonged to East Prussia from 1922 to 1939.

Counties

- 1819-1918

- 1819 Kreuzburg district renamed to Preußisch Eylau district

- In 1819 the Zinten district was renamed the Heiligenbeil district

- 1919-1933

- 1922 Ragnit and Tilsit districts merged to form Tilsit-Ragnit district

- 1927 Friedland district renamed Bartenstein district (Ostpr.)

- 1933-1938

- 1933 Oletzko district renamed Treuburg district

- 1938 Darkehmen district renamed to Angerapp district

- 1938 Niederung district renamed Elchniederung district

- 1938 Pillkallen district renamed to Schloßberg district (Ostpr.)

- 1938 Stallupönen district renamed to Ebenrode district

- 1939-1945

- 1939 Fischhausen district and Königsberg district merged to form Samland district

- 1939 District of Pogegen (Memel area) distributed to the districts of Tilsit-Ragnit and Heydekrug and a municipality to the urban district of Tilsit

- Establishment of new rural districts in areas that never belonged to the German Empire before

- 1939 Praschnitz district (from Polish Przasnysz )

- 1939 Zichenau district (from Polish Ciechanów )

- 1941 Mackeim district (initially Makow, from Maków in Poland )

- 1941 Mielau district (initially Mlawa, from Polish Mława )

- 1941 District Scharfenwiese (initially Ostrolenka, from Polish Ostrołęka )

- 1941 County Plock (Plock, first, from Polish. Płock )

- 1941 District of Plönen (initially Plonsk, from Polish Płońsk )

- 1941 Ostburg district (initially Pultusk, from Polish Pułtusk )

- 1941 District of Sichelberg (initially Schirps, from Polish Sierpc )

- 1941 Sudauen district (initially Suwalken, from Polish Suwałki )

Administrative division in 1937 and 1945

| Administrative division of East Prussia | |

|---|---|

| As of December 31, 1937 | Status January 1, 1945 |

| Olsztyn administrative district | |

| Urban district | |

| Counties | |

| Gumbinnen district | |

| City districts | |

| Counties | |

|

|

| Koenigsberg administrative district | |

| Urban district | |

| Counties | |

| West Prussia administrative district (seat: Marienwerder) | |

| Urban district | |

| Counties | |

| Zichenau district | |

| Counties | |

politics

Chief President

In 1765 Johann Friedrich von Domhardt became president of the Gumbinner and Königsberg war and domain chambers and thus the first high president in East Prussia. He was followed in 1791 by Friedrich Leopold von Schrötter , who in 1795 became Minister for East and New East Prussia. 1814–1824 Hans Jakob von Auerswald was Upper President of East Prussia. Under his successor Theodor von Schön (1824–1842) West and East Prussia were united to form the Province of Prussia . Followed him

- 1842–1848: Carl Wilhelm von Bötticher

- 1848–1849: Rudolf von Auerswald

- 1849–1850: Eduard von Flottwell

- 1850–1868: Franz August Eichmann

- 1869–1882: Karl von Horn (1872–1880 construction of the government building)

- 1882–1891: Albrecht von Schlieckmann

- 1891–1895: Udo zu Stolberg-Wernigerode

- 1895–1901: Wilhelm von Bismarck

- 1901–1903: Hugo Samuel von Richthofen

- 1903–1907: Friedrich von Moltke

- 1907–1914: Ludwig von Windheim

- 1914–1916: Adolf Tortilowicz von Batocki-Friebe

- 1916–1918: Friedrich von Berg

- 1918–1919: Adolf Tortilowicz von Batocki-Friebe

- 1919–1920: August Winnig , SPD

- 1920–1932: Ernst Siehr , DDP

- 1932–1933: Wilhelm Kutscher , DNVP

- 1933–1945: Erich Koch , NSDAP

Elections to the provincial assembly

- 1925: DNVP / DVP 45.6% - 40 seats | SPD 24.8% - 22 seats | Center 6.9% - 6 seats | KPD 6.9% - 6 seats | WP 4.2% - 4 seats | DVFP 4.2% - 4 seats | DDP 3.6% - 3 seats | VRP 2.4% - 2 seats

- 1929: DNVP 31.2% - 27 seats | SPD 26.0% - 23 seats | DVP 8.7% - 8 seats | KPD 8.6% - 8 seats | Center 8.1% - 7 seats | NSDAP 4.3% - 4 seats | WP 4.0% - 4 seats | CSVD 3.0% - 3 seats | DDP 2.8% - 3 seats

- 1933: NSDAP 58.2% - 51 seats | SPD 13.6% - 12 seats | DNVP 12.7% - 11 seats | Center 7.0% - 7 seats | KPD 6.0% - 6 seats

100% missing votes = nominations not represented in the provincial assembly.

Governors of the Provincial Parliament

- 1876–1878: Heinrich Rickert

- 1878–1884: Kurt von Saucken-Tarputschen

- 1884–1888: Alfred von Gramatzki

- 1888–1895: Klemens von Stockhausen

- 1896–1909: Rudolf von Brandt

- 1909–1916: Friedrich von Berg

- 1916–1928: Manfred Graf von Brünneck-Bellschwitz

- 1928-1936: Paul Blunk

- 1936–1939 (?): Helmuth von Wedelstädt

Elections to the Reichstag

The province formed constituency 1 for the elections to the Reichstag of the Weimar Republic .

economy

Agriculture

Until 1945 the economy of East Prussia was predominantly agricultural. Natural resources were almost missing. Due to the low population density of only 50 people per km² in some areas (as of 1938), the agricultural and forestry sector was dependent on the export of its surpluses.

The lowlands between the Nogat and Memel rivers and part of the Baltic ridge, often with good clay soils, were considered fertile. Other areas sometimes had poor sandy soil. The irrigation via lakes and rivers mostly made up for the lack of precipitation.

The disadvantage was the relatively cool climate that z. B. the mean January temperature in the southeast was 5 ° below zero. The fruit bloom did not usually begin until the end of May, and the grain was also late to harvest. It was therefore not worthwhile to plant a catch crop between harvesting the summer grain and sowing the winter grain. The main products were rye and potatoes. The cultivation of flax (Königsberg, Insterburg, Allenstein) and tobacco (Elbing) were poorly developed.

The livestock industry was profitable, for example extensive cattle breeding and the associated production of dairy products in the region around Tilsit. In the south of East Prussia, however, the focus was on pure meat production, with the rearing of “skinny cattle ” ( beef cattle ), sheep and geese. There was also horse breeding, with the Trakehnen stud farm gaining an international reputation.

Forestry benefited from the lush hardwood stocks in the lake district; The pine forests in the Rominten-Johannisburg area were also of importance.

Industry

Amber was one of the few natural resources in East Prussia, but only gave work to a few thousand people. It was extracted in the open pit near Palmnicken and processed in the manufactory in Königsberg. The lack of hard coal as an energy source has been an obstacle to building a significant industry. The low gradient of the lowland rivers also made the use of hydropower almost impossible.

That is why the trade was almost exclusively limited to the processing of agricultural and forestry raw materials in mills, distilleries, starch factories and sawmills. Two exceptions were railway construction in Elbing and shipbuilding in Königsberg.

The inadequate traffic route network was a hindrance. The rivers were frozen for up to four months and could only be used by vehicles up to 400 tons, the Oberland Canal could only withstand barges up to a maximum of 100 tons. The relatively strong dune formation on the coast also hindered access to the sea.

Well-known East Prussia

- Hannah Arendt (1906–1975), political theorist

- Rainer Barzel (1924-2006), politician (CDU)

- Otto Braun (1872–1955), Prussian Prime Minister (SPD)

- Lovis Corinth (1858–1925), painter

- Otto von Corvin (1812–1886), writer

- Marion Countess Dönhoff (1909–2002), publicist

- Herbert Ehrenberg (1926–2018), politician (SPD)

- Hugo Haase (1863-1919), politician (SPD)

- Johann Georg Hamann (1730–1788), Christian philosopher and writer

- Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803), poet, theologian, philosopher

- David Hilbert (1862–1943), mathematician

- ETA Hoffmann (1776–1822), writer, composer and musician

- Ingo Insterburg (1934–2018), comedian and musician

- Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), philosopher

- Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945), artist

- Eberhard von Kuenheim (* 1928), manager and former CEO of BMW AG

- Udo Lattek (1935–2015), football coach and journalist

- Veruschka Countess von Lehndorff (* 1939), artist

- Siegfried Lenz (1926–2014), writer

- Albert Lieven (1906–1971), actor

- Wolf von Lojewski (* 1937), television journalist

- Siegfried Maruhn (1923–2011), journalist and author

- Erich Mendelsohn (1887–1953), architect

- Agnes Miegel (1879–1964), writer

- Armin Mueller-Stahl (* 1930), actor

- Hagen Mueller-Stahl (1926–2019), theater director, film director and actor

- Oskar Negt (* 1934), sociologist

- Leah Rabin (1928–2000), Israeli politician

- Manfred Scheffner (1939–2019), jazz discographer

- Heinz Sielmann (1917–2006), animal filmmaker

- Arnold Sommerfeld (1868–1951), mathematician and physicist

- Georg Sterzinsky (1936–2011), Roman Catholic Archbishop of Berlin

- George Turner (* 1935), science politician, Berlin Senator

- Heinrich August Winkler (* 1938), historian

- Hans-Jürgen Wischnewski (1922–2005), politician

Nobel Prize Winner

- Otto Wallach (1910)

- Wilhelm Vienna (1911)

- Fritz Albert Lipmann (1953)

language

The East Low German and East Central German dialects spoken in East Prussia are recorded and described in the Prussian dictionary .

The Baltic Old Prussian spoken by the natives was extinct in the 17th century .

In 1925, 97.2% of the population stated German, 1.8% Masurian , 0.9% Polish and 0.1% Lithuanian as their mother tongue. Nehrung curian was spoken among fishermen on the spits .

Quirk

“The East Prussians lack grace. They do not win when they appear; but you can certainly build on its solid nature. East Prussia is the purest and best prose nature in Germany. "

"The almost divine serenity could well be described as East Prussian national peculiarity."

See also

- Great plague (Prussia)

- List of high schools in East Prussia

- List of counties in East Prussia

- List of cities in East Prussia

- Prussian Lithuania

Museums and Archives

- Image archive East Prussia

- Secret State Archive of Prussian Cultural Heritage

- Herder Institute (Marburg)

- Historical Commission for East and West Prussian State Research

- East Prussia cultural center

- Landsmannschaft East Prussia

- East Prussian State Museum

literature

- Complete and newest description of the earth of the Prussian monarchy and the Free State of Krakow , edited by G. Hussel. Weimar 1819, pp. 531-568 .

- Wilhelm Sahm : History of the plague in East Prussia. 1905.

- Hartmut Boockmann : East Prussia and West Prussia. In: German history in Eastern Europe. Siedler, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-88680-212-4 .

- Richard Jepsen Dethlefsen : The beautiful East Prussia. R. Piper, Munich 1916. ( online on a private website ( Memento from February 19, 2014 in the Internet Archive ))

- Wilhelm Gaerte : Prehistory of East Prussia. Koenigsberg 1929

- Yorck Deutschler: The Aestii - name for today's Estonians in Estonia or the submerged Pruzzen of East Prussia. In: The Singing Revolution - Chronicle of the Estonian Freedom Movement (1987-1991). Ingelheim, March 1998 / June 2000, ISBN 3-88758-077-X , pp. 196-198.

- Rüdiger Döhler : East Prussia after the First World War. Einst und Jetzt , Vol. 54 (2009), pp. 219-235.

- Rüdiger Döhler: Corps students in the administration of East Prussia. Einst und Jetzt, Vol. 54 (2009), pp. 240–246.

- Andreas Ehrhard (photos), Bernhard Pollmann (text): East Prussia. Bruckmann, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-7654-3877-4 . (Country portrait, current pictures from the former East Prussia)

- Walter Frevert : Rominten. BLV, Bonn [u. a.] 1957. (first part of the so-called "East Prussia Trilogy")

- Klaus von der Groeben : The country of East Prussia. Self-preservation, self-development, self-administration 1750 to 1945. Lorenz-von-Stein-Institute for Administrative Sciences at the Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel 1993. (Sources for administrative history no. 7)

- Klaus von der Groeben: Administration and Politics 1918–1933 using the example of East Prussia. Kiel 1998.

- Emil Johannes Guttzeit : East Prussia in 1440 pictures. Historical representations. Leer 1972–1984, Rheda-Wiedenbrück / Gütersloh 2001, Würzburg 2001, Augsburg 2006.

- Emil Johannes Guttzeit: East Prussian city arms. Ed .: Landsmannschaft Ostpreußen, Department of Culture, Waiblingen 1981.

- August Karl von Holsche : Geography and statistics of West, South and New East Prussia. In addition to a short history of the Kingdom of Poland up to its division. 2 volumes. Berlin 1800 and 1804. ( online in the Kujawsko-Pomorska Digital Library )

- Andreas Kossert : East Prussia. History and myth. Siedler, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-88680-808-4 or 1st edition, Pantheon, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-570-55020-5 .

- Andreas Kossert, Jörn Barfod, Arnold Bartetzky, Hans J. Bömelburg, Józef Borzyszkowski, Bertram Faensen, Jörg Hackmann, Christoph Hinkelmann, Malgorzata Jackiewicz-Garniec, Gennadij Kretinin, Heinrich Lange, Ruth Leiserowitz, Peter Letkemann, Marc Löwener, Angelika. Janusz Maek Marsch, Martynas Purvinas, Milo ezník, Rainer Slotta , Heiko Stern: Cultural landscape of East and West Prussia. German Cultural Forum for Eastern Europe V., 1st edition, 2005, ISBN 3-936168-19-9 .

- Adam Kraft, Rudolf Naujok: East Prussia - With West Prussia / Danzig and Memel. A picture of the unforgettable home with 220 photos. 5th edition, Adam Kraft Verlag, Mannheim 1978, ISBN 3-8083-1022-7 .

- Hans Kramer : Elk forest. The elk forest as a source and refuge for East Prussian hunting. 2nd Edition. Jagd- und Kulturverlag, Sulzberg im Allgäu 1985, ISBN 3-925456-00-7 (third part of the so-called "East Prussia Trilogy").

- Dietrich Lange: East Prussia geographical register of places. Including the Memel area, the Soldau area and the administrative district of West Prussia (1919–1939). Slices Of Life-Verlag, Königslutter 2005, ISBN 3-934652-49-2 .

- Ruth Leiserowitz : Sabbath candlesticks and warriors' association: Jews in the East Prussian-Lithuanian border region 1812–1942. Fiber Verlag, Osnabrück 2010, ISBN 978-3-938400-59-3 .

- Klaus-Jürgen Liedtke : The sunken world. An East Prussian village in people's stories. Eichborn, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-8218-6215-6 .

- Freya Klier : We Last Children of East Prussia: Witnesses to a Forgotten Generation , Herder Verlag, Freiburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-451-30704-1 .

- Herbert Ludwig: Study trips and experiences in East Prussia. Deutsche Corpszeitung, Volume 46 (1930), pp. 353-361; Volume 47 (1930), pp. 6-8.

- Fritz Mielert : East Prussia. In addition to the Memel region and the Free City of Danzig. In: Geography Monographs , Vol. 35. Velhagen & Klasing, Bielefeld 1926 (reprint: Bechtermünz, Augsburg 1999, ISBN 3-8289-0272-3 ).

- Christian Papendick : The north of East Prussia. Land between failure and hope. A picture documentation 1992-2008. Husum Verlag, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-89876-232-8 .

- Walter Pauly : As district administrator in East Prussia. Ragnit – Allenstein (= East German contributions from the Göttingen working group; Vol. VIII). Holzner-Verlag, Würzburg 1957.

- Jan Przypkowski (Ed.): East Prussia - Documentation of a historical province. The photographic collection of the Provincial Monuments Office in Königsberg. Warsaw 2006, ISBN 83-89101-44-0 .

- Manfred Raether: Poland's German Past. Schöneck 2004 and 2012, ISBN 3-00-012451-9 . - New edition as an e-book; Kindle version.

- Christian Saehrendt : The horror vacui of demography: 100 years of emigration from the German east. In: Tel Aviver Yearbook for German History , 35, 2007, pp. 237–250.

- Klaus Schwabe (Ed.): The Prussian Oberpräsident 1815–1945 (= German ruling classes in modern times. Vol. 15 = Büdinger research on social history. 1981). Boldt, Boppard am Rhein 1985, ISBN 3-7646-1857-4 .

- Robert Traba : East Prussia - the construction of a German province. A study of regional and national identity 1914–1933 , translated from Polish by Peter Oliver Loew. Fiber Verlag, Osnabrück 2010, ISBN 978-3-938400-52-4 .

- George Turner : We'll take home with us. A contribution to the emigration of Salzburg Protestants in 1732, their settlement in East Prussia and their expulsion in 1944/45 using the example of the Hofer family. 3rd, revised and expanded edition. Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-8305-1900-3 .

- Hermann Pölking: East Prussia - Biography of a Province. Be.bra-Verlag, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-89809-094-0 .

- Johann Friedrich Goldbeck : Complete topography of the Kingdom of Prussia. Part I: Topography of East Prussia. Königsberg / Leipzig 1785, reprint Hamburg 1990 ( Google Books ).

- Otto Wiechert: Homeland Atlas for East Prussia. Publishers List and von Bressensdorf, Leipzig 1926. New edition Weltbild 2011, ISBN 978-3-8289-0908-3 .

- Old Prussian biography. Ed. on behalf of the Historical Commission for East and West Prussian State Research by Klaus Bürger. Finished in collaboration with Joachim Artz von Bernhart Jähnig. Elwert, Marburg 1936 ff. 2 volumes (1936–1967), 3 supplementary volumes published (as of 2015).

- Richard Lakowski: East Prussia 1944/45. War in the northeast of the German Empire . Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2016, ISBN 978-3-506-78574-9 .

Web links

- The expulsion of the Germans from the East in the culture of remembrance. (PDF; 522 kB), Konrad Adenauer Foundation

- ostpreussen.net

- Landsmannschaft Ostpreußen e. V.

- Photos from East Prussia at the East Prussia Image Archive

- East Prussia - a photographic journey with current images

- Prussia Chronicle rbb

- City coat of arms of East Prussia

- East Prussia Province (with old postcards)

- Governors of East Prussia

Individual evidence

- ↑ Prussian Provinces 1910

- ↑ Statistical Yearbook for the German Reich 1938/39 (digitized version)

- ^ A b Michael Rademacher: German administrative history. Archived from the original on July 31, 2015 ; Retrieved June 2, 2015 .

- ↑ See e.g. B. Jochen Abr. Frowein (ed.): Germany's current constitution: reports and discussions at the special meeting of the Association of German Constitutional Law Teachers in Berlin on April 27, 1990. VVDStRL 49 (1990). de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1990, pp. 132 ff. (134) .

- ↑ January Baldowski: Warmia and Mazury. ISBN 3-87466-173-3 , pp. 16-17.

- ^ Charles Colbeck: The Public Schools Historical Atlas. Longmans / Green, New York / London / Bombay 1905.

- ↑ Braunswalde Willenberg near Marienburg Gräberfeld

- ↑ “[…] Further now on the right coast of the Sueven Sea the Aesti peoples are washed, whose customs and entire appearance are like the Sueven, the language closer to the British. They worship the mother of gods. As a badge of this belief they wear boar images; this, instead of arms and protection for everyone, ensures the worshiper of the goddess carefree even in the midst of enemies. Iron is seldom used, and the club is often used. They grow grain and other crops with great patience for the usual indolence of the Teutons. Meanwhile they also search the sea and collect amber, among them the only ones, between the shallows and on the beach itself, which they call glass. [...] "( Anton Baumstark (transl., 1876): The Germania of Tacitus on Wikisource )

- ↑ De origine actibusque Getarum (On the origin and deeds of the Goths), 23, 120: "Aestorum quoque similiter nationem, qui longissimam ripam Oceani Germanici insident, idem ipse prudentia et virtute subegit omnibusque Scythiae et Germaniae nationibus ac si propriis lavoribus imperavit." ( digital-sammlungen.de )

- ↑ Martin Armgart: Konrad I, Duke of Mazovia. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 4, Bautz, Herzberg 1992, ISBN 3-88309-038-7 , Col. 419-423.

- ↑ Katrin Möller-Funck: The crisis in the crisis. Existential threat and social recession in the Kingdom of Prussia at the beginning of the 18th century . Dissertation (University of Rostock). 2015, p. 241 ( uni-rostock.de [PDF]).

- ^ Mack Walker: The Salzburg exiles as social history . A Berlin research report. In: Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin (Ed.): Yearbook 1982/83 . 1983, p. 391 ( wiko-berlin.de [PDF]).

- ^ X. von Hasenkamp: East Prussia under the double pair. Historical sketch of the Russian invasion in the days of the Seven Years' War. Königsberg 1866 ( full view ).

- ^ Teltower Kreisblatt dated June 14, 1892, p. 1 on the Sachsengangerei from the Gumbinnen and Marienwerder administrative districts .

- ^ A b Andreas Kossert: Prussia, Germans or Poles? The Masurians in the field of tension of ethnic nationalism 1870–1956 . Ed .: German Historical Institute Warsaw . Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2001, ISBN 3-447-04415-2 , p. 130 .

- ^ A b Fried von Batocki, Klaus von der Groeben : Adolf von Batocki. In action for East Prussia and the Reich. A picture of life. Raisdorf 1998, ISBN 3-9802210-9-1 .

- ^ Report of the Reichszentrale für Heimatdienst on the situation in East Prussia from March 3, 1920 (Federal Archives, files of the Reich Chancellery 1919-1933)

- ^ Andreas Kossert : East Prussia. History and myth. Siedler, 2005, p. 222.

- ^ Andreas Geißler, Konrad Koschinski: 130 years of the East Railway Berlin - Königsberg - Baltic States. Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-89218-048-2 , p. 87.

- ^ Andreas Geißler, Konrad Koschinski: 130 years of the East Railway Berlin - Königsberg - Baltic States. Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-89218-048-2 , p. 91 ff.

- ^ Reichstag elections, constituency of East Prussia . www.wahlen-in-deutschland.de Retrieved on January 11, 2017

- ^ Richard Blanke: Polish-speaking Germans? Language and national identity among the Masurians since 1871. 2001, ISBN 3-412-12000-6 , p. 285 .

- ^ Andreas Kossert: East Prussia. History and myth. P. 354.

- ^ Andreas Kossert: East Prussia. History and myth. P. 353.

- ^ Andreas Kossert: Masuria. P. 366.

- ↑ See Adolf Laufs : Rechtsentwicklungen in Deutschland. 5th, revised. and one chapter (GDR) additional edition, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1996, ISBN 3-11-014620-7 , p. 399 .

- ↑ Moscow offered negotiations on East Prussia. Mirror online

- ^ Walter Golze: Germany's economy and the world , 4th edition, Teubner, Leipzig and Berlin 1938.

- ↑ On the census of 1925 see Der Große Brockhaus , 15th edition, 13th volume, p. 838

Remarks

- ↑ Between 1793 and 1795, in the course of the 2nd and 3rd partition of Poland, the Kingdom of Prussia was joined by South Prussia, New East Prussia and New Silesia. Later the "Kingdom" and thus East Prussia lay outside the German Confederation .

- ^ Andreas Kossert: Masuria, East Prussia's forgotten south. S. 363, 364: “Similar to how the NS- Volkslisten (National Socialist People's Lists) in Reichsgau Wartheland and Danzig-West Prussia had determined the Germanisability of the Germans and small Polish groups living there since 1939 by dividing them into four categories based on biological racism, the Polish provincial administration proposed a classification of the residents of Masuria according to ethnic racism after 1945. "

- ↑ Explained in more detail by Georg Ress , in: Ulrich Beyerlin (Ed.): Law between upheaval and preservation. Festschrift for Rudolf Bernhardt (= contributions to foreign public law and international law; vol. 120). Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg / New York 1995, p. 833 ff. (835) with further references

- ↑ The collection is published by the German Historical Institute in Warsaw , the Institute for Art Research of the Polish Academy of Sciences , the Olsztyn State Archives and the Museum of Warmia and Mazury . The CD with 7,900 pictures is at the German Cultural Forum Eastern Europe e. V. available in Potsdam.