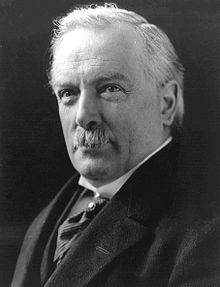

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor OM (born January 17, 1863 in Manchester as David George , † March 26, 1945 in Llanystumdwy , Caernarfonshire ) was a British politician . He was elected Prime Minister during World War I in December 1916 and was the last Liberal to hold that post. In October 1922 he was overthrown by the Conservatives. In 1919 he was one of the " Big Four " at the Paris Peace Conference .

Childhood and youth

After the early death of his father, an elementary school principal, David George grew up with his maternal uncle, Richard Lloyd. In admiration for his uncle, who later made it possible for him to study law, the young David George added the word Lloyd to his name. Whether this was a first or last name remained a matter of dispute throughout his life. Until 1917, Lloyd was listed as a first name in British encyclopedias, since then as a surname.

Political rise

In 1890 Lloyd George was elected to the British House of Commons for the Liberals in the Welsh constituency of Caernarfon , of which he was a member until 1945. He belonged to the left-wing liberal wing of his party and was a member of the renowned Reform Club . The young MP drew attention early on with fiery, sometimes aggressive speeches. First, he campaigned for more self-determination for Wales and - at that time, a pacifist - against the Boer War . In 1905, Lloyd George joined Henry Campbell-Bannerman's Liberal cabinet as Secretary of Commerce . When he died in 1908, Herbert Henry Asquith became the new Prime Minister, and Lloyd George took Asquith's previous position as Chancellor of the Exchequer , which he held until 1915. In his capacity as Chancellor of the Exchequer, he campaigned for fundamental social reforms , such as a general British pension scheme, as well as for the autonomy of Ireland . To finance his ambitious social program, he introduced the first progressive income taxation in Great Britain in 1909 and significantly increased inheritance tax. This led to fierce resistance in the House of Lords , which was broken in 1911 with the Parliament Act , which permanently restricted the power of the House of Lords.

During this time he was also involved in the Marconi scandal . On February 19, 1913, his country house under construction was blown up by the suffragette Emily Davison .

Lloyd George as premier

war and peace

Lloyd George's pacifist attitude changed in 1911 against the backdrop of the second Moroccan crisis . In his famous Mansion House speech he indicated for the first time his willingness to accept war as a means of politics in the sense of a last resort. Although in the July crisis of 1914 he was one of those members of the British government who tried to prevent Britain from becoming involved in the European war, after the British declaration of war on the German Reich on August 4, 1914 , he declared himself to be the only member of the "radical pacifist" designated wing of the cabinet ready to remain in government. On their behalf, he founded the War Propaganda Bureau . When the coalition government was formed with the Conservatives in May 1915, he became Minister of Munitions and Minister of War in the summer of 1916 .

At the beginning of December 1916 he forced Asquith to resign from his post as premier. Lloyd George himself headed the coalition government with the Conservatives, while Asquith's supporters went into opposition. The Liberal Party became so divided that it never fully recovered. In the following years he achieved an almost dictatorial position in the cabinet and pursued a war policy aimed at a complete defeat of the German Reich. Lloyd George became the driving force behind Britain's economic warfare. It was thanks to the economic system he developed and his concessions to the workers that Great Britain did not collapse economically.

Lloyd George had been a so-called Eastener within British politics from the beginning of the war , who did not seek the decision at the strongest point of the Central Powers - the Western Front - but wanted to eliminate the allies of the German Reich first. In the militarily critical situation for the Entente in 1917, instead of the method of bringing Germany down by the process of knocking the props under her (" bringing Germany down by progressively knocking away the props from under her "), he tried to do this To weaken the German Empire through a separate peace with Austria-Hungary .

On March 20, 1917, Lloyd George described the elimination of reactionary military governments and the establishment of popular governments as the basis of international peace as Britain's true war goals . On August 4th of the same year, the National War Aims Committee , with Lloyd George and Asquith as presidents, began a lively propaganda activity along these lines.

At the Peace Conference of Versailles , he represented a middle position between its ally, US President Woodrow Wilson and the French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau . He advocated a political punishment of the German Reich, which he blamed for the outbreak of war, but, unlike Clemenceau, did not want to fragment the Reich territorially and permanently damage it economically. The fact that there were referendums in the southern and eastern border areas of East Prussia and Upper Silesia on remaining in the German Reich was primarily due to Lloyd George's initiative.

Lloyd George ultimately failed with his demand: The new map of Europe must be so drawn as to leave no cause for disputation which would eventually drag Europe into a new war (“The new map of Europe must be drawn in such a way that it has no reason leaves more for disputes that would eventually drag Europe into a new war. ”). In relation to the former Ottoman Empire , which was allied with the German Empire in the war, Lloyd George took a much tougher position: The terms of the Treaty of Sèvres were extremely restrictive towards the Turks, which, according to some historians, had the following reasons: the genocide of the Armenians and the loss-making battle of the Dardanelles in 1915. In the Agreement on Constantinople and the Straits , it was decided to finally drive the Turks out of Europe. Lloyd George said the war and the defeat of the Turks provided an opportunity to "solve this problem once and for all". On December 18, 1916, the Allies had announced to US President Wilson that they would "liberate the peoples who were subject to the bloody tyranny of the Turks". Other quotes from Lloyd George on the subject were: “When the terms of peace are proclaimed, it will be seen what harsh punishments the Turks will be sentenced to for their madness, their blindness and their murders ... The punishments will be so terrible that even their worst enemies will be satisfied. ”“ What will happen to Mesopotamia must be decided in the sessions of the Peace Congress, but one thing will never happen. It will never be left to the damned tyranny of the Turk again. "

In 1919 and 1920, Lloyd George succeeded in negotiating impending workers' uprisings. In terms of foreign policy, he was largely unsuccessful after the war. His efforts to create a great Greek empire to the detriment of Turkey failed.

Decline of his government

The most pressing domestic problem of the time was the solution to the Irish question. As a Welshman - to this day he is the only Welshman to ever hold the post of British Prime Minister - he understood the desire of a majority of Irish people for more independence. With the creation of the Irish Free State in 1921, i.e. with the granting of full autonomy for the predominantly Catholic south of the island, he sought to establish a sustainable peace solution. Terrorist campaigns by the IRA in London and the Northern Irish province, however, caused resentment among his conservative coalition partner. The massive sale of nobility titles to build a personal campaign fund caused a widespread scandal in June 1922 when his practices were exposed in the House of Lords . This, together with differences over economic policy and the failure of his policies in the Middle East , where he supported the Arab nationalists against the French in Syria , led to the overthrow of Lloyd George in October 1922 in the wake of the Chanak crisis and the formation of a conservative government under Andrew Bonar Law .

Because of their split, the Liberals lost much of their weight in British politics and have never appointed a Prime Minister to this day.

Late years

Lloyd George remained a member of the House of Commons. In the following years he was repeatedly discussed as a candidate for ministerial offices, but never again held an official function in the executive branch . From 1926 to 1931 he was party leader of the Liberals.

In the British general election on May 30, 1929, the Liberals won 23.6 percent of the vote or (as a result of majority voting) 9.6% (59 of 615) seats in the lower house. You were thereby "tip the scales"; neither Labor (287) nor the Tories (260) had a lower house majority. Lloyd George and the Liberals backed Labor Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald . This crashed in autumn 1931 at the height of the global economic crisis .

In the 1930s, Lloyd George was one of the representatives of the appeasement policy and tried to mediate between England and Hitler's Germany on behalf of the British government . On September 4, 1936, Lloyd George met Adolf Hitler in the Berghof in Berchtesgaden to obtain information from him about the foreign policy plans of the German Reich. Hitler presented Lloyd George with a signed portrait and expressed his joy at "meeting the man who won the war". Lloyd George, who was already senile at the time (at the age of 73), was moved by this gesture and replied that he was very honored to receive such a gift from the hands of the “greatest living German”. After his return to England he wrote an article for the Daily Express on September 17 , in which he praised Hitler in the highest tones and noted: “The Germans have definitely made up their minds never to quarrel with us again” (“Die Deutschen have definitely decided never to argue with us again. "). The entire conversation was translated by the then "personal translator" Paul-Otto Schmidt .

In 1938 Lloyd George said he received an offer from the Republican-Spanish government, which had got into trouble during the Spanish Civil War with the military party around General Franco , to join it as Minister of Supply, which he finally turned down. In 1940 he stood out for the last time as a speaker in the House of Commons in the so-called " Norwegian debate ", which led to the overthrow of the government under Neville Chamberlain and the formation of the war government Churchill . At times he had been considered a possible successor to Chamberlain, alongside Churchill himself, Anthony Eden and Lord Halifax . Churchill also tried to integrate him into his new cabinet, but failed with this request.

In 1945 Lloyd George was raised to the hereditary nobility as Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor at the suggestion of Churchill, who wanted to spare his old friend the strains of a strenuous election campaign due to the end of the war which was becoming foreseeable at this time . Lloyd George received a seat in the House of Lords . He passed away a few months later.

In his former home, Llanystumdwy , a museum commemorates David Lloyd George.

Lloyd George in the judgment of posterity

Peter de Mendelssohn wrote of Winston Churchill and David Lloyd George: “British politics has never more clearly emphasized the two fundamental driving forces that inexorably push a man to the highest position in state and community, to power, authority and responsibility Men. Lloyd George saw a task and expected himself to be big enough to do it. Churchill saw himself and expected the task to be big enough for him. ”In a BBC poll of historians, politicians and political commentators, in which voters would choose the best prime minister of the 20th century, Lloyd George proved second place (behind Churchill).

Trivia

A raspberry variety was named after Lloyd George .

Fonts (selection)

- Lloyd George: Better times . Translation Helene Simon . Foreword by Eduard Bernstein . Jena: Eugen Diederichs, 1911

literature

- Lord Beaverbrook : The Decline and Fall of Lloyd George. Collins, London, 1963.

- John Campbell: Lloyd George: The Goat in the Wilderness 1922-1931. Jonathan Cape, London 1977, ISBN 0-224-01296-7 .

- Roy Hattersley : David Lloyd George: The Great Outsider. Little Brown, London, 2010, ISBN 978-0-349-12110-9 .

- Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, ISBN 1-349-00522-3 .

- Lloyd George, David . In: Encyclopædia Britannica . 11th edition. tape 16 : L - Lord Advocate . London 1911, p. 832 (English, full text [ Wikisource ]).

Web links

- Literature by and about David Lloyd George in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about David Lloyd George in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- The Lloyd George Society (English)

- Anja Kettern: David Lloyd George. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

Individual evidence

- ^ Chronicle February 19, 1913. German Historical Museum

- ↑ When Britain's feminists became rabid . Zeit Online , November 21, 2011

- ^ David French: Allies, Rivals and Enemies: British Strategy and War Aims during the First World War. In: John Turner (Ed.): Britain and the First World War . London 1988, ISBN 0-04-445108-3 , pp. 22-35, here: p. 33.

- ^ VH Rothwell: British War Aims and Peace Diplomacy 1914-1918 . Oxford 1971, pp. 71 and 145. Overall on this topic see: Hubert Gebele: Great Britain and the Great War. The dispute over war and peace goals from the outbreak of war in 1914 to the peace agreements of 1919/1920. Roderer, Regensburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-89783-671-6 .

- ↑ Harold I. Nelson: Land and Power. British and Allied Policy on Germany's Frontiers 1916-19 . London 1963, p. 303.

- ^ Statement by Lloyd George in Gotthard Jäschke : Mustafa Kemal and England in a new perspective. In: Die Welt des Islams , Volume XVI, Leiden 1975, p. 225

- ↑ Gotthard Jäschke: Kurtuluş Savaşı ile ilgili İngiliz Belgeleri ( English documents on the war of liberation ), Ankara 1971, p. 54

- ↑ Harold WV Temperley; History of the Peace Conference of Paris. Volume 6, London / New York / Toronto 1969, p. 23.

- ↑ TZ Tunaya: Türkiye'de Siyasi Partiler (Political parties in Turkey). Istanbul 1989, Volume 2, p. 27.

- ^ Richard G. Hovannisian: The Allies and Armenia, 1915-18. In: Journal of Contemporary History , Volume 3, 1968, p. 148.

- ↑ Thomas Jones: Lloyd George. Oxford University Press, London 1951, online edition , p. 247.

- ↑ Thomas Jones: Lloyd George. P. 248.

- ^ CP Snow : Lloyd George. In: Variety of Men. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth 1967, pp. 92-110.

- ^ The Lloyd George Museum on the Gwynned Council website, accessed August 21, 2016.

- ^ Peter de Mendelssohn: Churchill. His way and his world. Lemm, Freiburg 1957.

- ^ Churchill 'greatest PM of 20th Century'. BBC , January 4, 2000, accessed September 26, 2019 .

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener |

Secretary of State for War 1916 |

Edward Stanley, 17th Earl of Derby |

| Herbert Henry Asquith |

British Prime Minister 1916–1922 |

Andrew Bonar Law |

| New title created |

Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor 1945 |

Richard Lloyd George |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lloyd George, David |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British politician, member of the House of Commons |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 17, 1863 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Manchester |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 26, 1945 |

| Place of death | Llanystumdwy , Caernarfonshire |