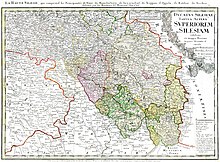

Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( German Silesian dialect : Aeberschläsing or Oberschläsing , Polish : Górny Śląsk , Polish Upper Silesian dialect : Gōrny Ślōnsk , Czech : Horní Slezsko ) is the southeastern part of the historical region of Silesia , which is now largely in Poland (in the Silesian Voivodeship and Voivodeship ) lies. The south and south-west of the Austrian Silesia , which remained with Austria until 1918 , is part of itCzech Republic (in the Moravian-Silesian Region ).

The city of Opole is considered the historical capital of Upper Silesia . In the eastern part of Upper Silesia there is the extensive Upper Silesian industrial area with the center of Katowice , which is also the most populous city in Upper Silesia.

Political historical overview

In the early Middle Ages, Upper Silesia, whose original population was of West Slavic descent, belonged to the area of influence of the Moravian Empire . After its fall in 907 AD, alternating Polish and Bohemian rulers claimed the region for themselves. With the demarcation along the Sudeten Mountains , Upper Silesia finally became part of the Kingdom of Poland in the course of the Treaty of Glatz in 1137 .

With the Treaty of Trenčín in 1335, the region was incorporated into the Kingdom of Bohemia when the Silesian Piasts left the Kingdom of Poland . With the Treaty of Namslau in 1348, Silesia became part of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation . After the death of the Bohemian King Ludwig II. In 1526, the Bohemian royal dignity came to the Habsburg Ferdinand I. As kings of Bohemia, the Habsburgs were sovereigns and dukes of Upper Silesia until 1742. After the First Silesian War in 1742, most of the region fell to the Kingdom of Prussia . In 1815 the Prussian Province of Silesia was established for the whole of Silesia . A smaller part remained under the rule of the Habsburgs as Austrian Silesia . From 1815 to 1866 Upper Silesia belonged to the German Confederation and from 1871 to the German Empire .

For centuries, Upper Silesia was a mixed language area. On the eve of the First World War , 45% of the German population and 43% of the Austrian population cited German as their mother tongue. After the First World War, mainly due to the regaining of Polish independence , there was a referendum in a part of Upper Silesia, in which 59.6% of the population in the voting area voted for membership of the German Reich. Despite the vote, the voting area was divided into three parts as a result of the uprisings in Upper Silesia . The Hultschiner Ländchen , located in the south of Upper Silesia, joined the newly founded Czechoslovakia without a referendum . The majority of the Upper Silesian industrial area came to the Second Polish Republic and was reorganized there from 1920 in the Autonomous Silesian Voivodeship , which also included Teschener Silesia .

The largest part of Upper Silesia in terms of area and population remained with the German Reich and was reorganized from 1919 in the Province of Upper Silesia, which belongs to the Free State of Prussia . Due to the shift to the west of Poland after the end of the Second World War , in 1945 the part that remained with the German Reich until 1939 became part of the People's Republic of Poland .

Today Upper Silesia is the most populous region within the Republic of Poland , which was established in 1989. In 1990, after reunification , the Federal Republic of Germany recognized the Oder-Neisse border in the two-plus-four treaty and thus the separation of Upper Silesia from Germany to Poland.

geography

Due to different geopolitical events and the division of inheritance among the Piasts , the former Polish ruling dynasty, Silesia, like many regions of Europe, was split up into different domains. Without an official dichotomy, the name Lower Silesia had become naturalized for the northwest with 16 duchies and principalities, and the name Upper Silesia for the southeast with eight duchies and principalities. Both also included a few smaller gentlemen.

Before the administrative structures have been streamlined in the 19th century, Upper Silesia had the duchies and principalities of Cieszyn (Księstwo cieszyńskie / Těšínské knížectví), Opava (Knížectví Opavské) Jägerndorf (Krnovské knížectví), Opole (Księstwo opolskie) Ratibor (Księstwo Raciborskie / Ratibořské knížectví) Bielitz (Księstwo Bielskie) Pless (Księstwo pszczyńskie) and Beuthen (Księstwo Bytomskie) comprises.

As a historical landscape , Upper Silesia borders the historical landscapes of Lower Silesia in the northwest, Greater Poland in the north, Lesser Poland in the east and Moravia in the south.

The Prussian Province of Upper Silesia and the Autonomous Voivodeship of Silesia , which was separated from it in 1922 , bordered the Prussian Province of Lower Silesia , the Poznan Voivodeship (previously the Prussian Province of Poznan ), the Lodsch Voivodeship , the Kielce Voivodeship and the Krakow Voivodeship , and the Czechoslovakian State of Silesia , which in 1928 was united with the country of Moravia to form the country of Moravia-Silesia.

The present-day Silesian and Opole voivodships , which include the former Prussian province, but extend beyond it to the west and east, border on the Voivodeships of Lower Silesia , Greater Poland , Lodsch , Heiligkreuz and Lesser Poland , as well as the Moravian-Silesian Land and the Olomouc Land .

Significant rivers in Upper Silesia include the Vistula , the Oder , the Olsa , the Malapane , the Glatzer Neisse , the Oppa , the Raude and the Klodnitz .

The highest point of the two Upper Silesian Voivodships in Poland is the 1220 m high Aries Mountain ( Barania Góra) in the Beskid Mountains (Beskidy). The highest mountain in the Czech part of Silesia is the 1491 m high Altvater (Praděd) in the Jeseníky Mountains (Hrubý Jeseník).

Administrative affiliation

Administratively belongs Upper Silesia, which does not form a political entity today, in the West to the province of Opole in the east to the province of Silesia , in the south to the Moravian-Silesian country and a small part in the southwest of Olomouc country .

Cities

The Upper Silesian towns with more than 100,000 inhabitants include Katowice ( Kattowitz ), Gliwice ( Gleiwitz ), Zabrze ( Hindenburg OS ), Bytom ( Beuthen ), Ruda Śląska ( Ruda ), Rybnik , Tychy ( Tichau ), Opole ( Oppeln ), Chorzów ( Königshütte ) in Poland and Ostrava (Ostrau) in the Czech Republic.

history

middle Ages

After the migration period , the Slavic Opolans (the capital Opole is named after them ) came to the country and possibly mixed with the Germans and Celts who had stayed behind . Mieszko I. incorporated Silesia into the Polish Piast Empire . When Poland split into partial duchies, the Silesian Piasts joined the Holy Roman Empire . Branches of the dynasty lasted longer here than in Poland. A little later, Silesia came under Bohemian sovereignty. It remained closely connected to Bohemia until the Silesian Wars of Frederick the Great .

After the Mongol storm ( Battle of Liegnitz (1241) ), especially from around 1260 under Duke Wladislaus I , German settlers also came to Upper Silesia, but in fewer numbers than to the western parts of the country because of the greater distance. On the other hand, local, Slavic-speaking free farmers were already involved in the colonization under German settlement law in large numbers. According to sources from the early 14th century, such as the Liber fundationis episcopatus Vratislaviensis , the largest accumulations of German medieval place names were in the Duchy of Teschen with the Auschwitz castellany (see Bielitz-Bialaer Sprachinsel ), while many areas do not have any German-language traces in the place names . When the Great Plague broke out in the empire in 1347/48 , the flow of immigrants from the empire decreased sharply and the eastern settlement practically came to a standstill. As a result, in contrast to Lower Silesia, the linguistic assimilation process stalled . Since Silesia was closely connected with Bohemia, Czech was at times the most important document language.

The name Upper Silesia (Latin Silesia Superior ) was first mentioned in a document in the late 15th century, at the time of the conquest of the area by the Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus and his efforts to consolidate.

Language development

While around 96 percent of the Lower Silesians spoke German, 53 percent of the Upper Silesians stated Polish as their first language. Among the Polish language, the Silesian dialect, which was also called Water Polish , can be seen here, which was mixed with numerous Germanisms and Czech influences. In addition to this dialect, most spoke German as a second language, in the dialect form Upper Silesian , which differed from High German through particularly hard throat sounds and systematic rounding of the front rounded vowels (for example, stage = bee, solve = read), which is also the case for German speakers with Slavic Mother tongue is characteristic.

The importance of the German language increased with urbanization and the industrialization of the Upper Silesian industrial area . In addition to the (water) Polish-speaking Upper Silesia, many Germans from Lower Silesia or the neighboring Sudeten German areas and also a large number of Poles from the province of Posen or the neighboring Russian " Congress Poland " came to Upper Silesia. Despite or precisely because of this difficult and complex linguistic situation - Lachish was also spoken in the southern part of the country , which is very close to Czech - the coexistence of the parts of the population was peaceful until the First World War; loyalty to the German Reich was expressed, among other things, in the great dominance of the Catholic Center Party. Before the First World War, the situation changed, and the question of nationality now emerged openly. By founding numerous Polish associations and newspapers, Polish nationalists (including those from the Polish subdivisions ) tried to awaken a national (Polish) awareness of the Slavophonic Upper Silesians. In the 1907 Reichstag elections, the Polish party achieved a majority of 39.5 percent of the votes in Upper Silesia and the Opole administrative region , but the majority of the seats retained the center (31.7 percent). In some constituencies, the Polish Party had achieved an absolute majority.

Outside of the industrial area, the areas around Opole , the later West Upper Silesia , the original situation could be preserved, but the Silesian dialect of Polish lost more and more speakers, especially in the interwar period , especially since not a few Polish-speaking residents migrated to the now Polish East Upper Silesia .

After the First World War, an attempt was made to establish the province of Upper Silesia in 1919 to take account of the linguistic / cultural differences between the region and the rest of Silesia.

Development of the ethno-linguistic structure

| Number of Polish-speaking and German-speaking population (Opole administrative district) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| year | 1819 | 1828 | 1831 | 1837 | 1840 | 1843 | 1846 | 1852 | 1858 | 1861 | 1867 | 1890 | 1900 | 1905 | 1910 | ||

| Polish | 377,100 (67.2%) | 418,437 | 456,348 | 495,362 | 525.395 | 540.402 | 568,582 | 584.293 | 612,849 | 665.865 | 742.153 | 918.728 (58.2%) | 1,048,230 (56.1%) | 1,158,805 (56.9%) | 1,169,340 (53.0%) | ||

| German | 162,600 (29.0%) | 255.383 | 257,852 | 290.168 | 330.099 | 348.094 | 364.175 | 363,990 | 406,950 | 409.218 | 457.545 | 566,523 (35.9%) | 684,397 (36.6%) | 757,200 (37.2%) | 884.045 (40.0%) | ||

Referendum and partition in 1922

After the First World War, according to the Versailles Treaty, parts of the border between Poland and Germany were to be regulated by referendums. The Inter-allied government and Plebiszitskommission for Upper Silesia , which was to manage the referendum had to inform the Allied Supreme Council according to the contract the task of community-point results and to submit a proposal on the line, "in Upper Silesia, taking into account both the express intention of inhabitants as also the geographical and economic position of the localities should be assumed as the border of Germany ” . The final decision on the border line to be determined should be left to the Board of Governors. Between the end of the war and the referendum, there were violent clashes between Polish residents, who demanded the annexation to Poland, and German police units and volunteer corps during the uprisings in Upper Silesia . On the day of the vote, March 20, 1921, with a turnout of 97.5 percent, which reflects the extent of the polarization in the population, 707,045 Upper Silesians (59.4 percent) voted for Germany and 479,232 (40.6 percent) for Poland . The importance of this unexpectedly positive vote for Germany despite adverse conditions and massive Polish propaganda was increased by the fact that the voting area only included that part of Upper Silesia in which a high proportion of Slavic-speaking population had been determined in censuses: while there was also a small one Part of the Lower Silesian district of Namslau , the districts of Falkenberg OS , Grottkau , Neisse and the western part of the district of Neustadt OS , which continued to belong to the German Empire, as well as the southern part of the Ratibor district ( Hultschiner Ländchen ) , which had already ceded to Czechoslovakia in 1920, remained from the vote locked out. The result therefore led to the conclusion that many who had given Polish as their mother tongue in censuses had also voted for Germany.

Due to the tense situation in Upper Silesia and between the German and Polish states, the result initially contributed more to the aggravation of the fronts than to clarifying the situation. On the German-speaking side it was mostly celebrated propagandistically as a German “victory” and “rescue of Upper Silesia”; only a few votes indicated in advance that even “if the […] vote were to result in a huge majority for Germany, part of Upper Silesia could still be awarded to the Poles” . On the Polish side, as a reaction to the result of the vote, which was considered to be unfavorable, and to the Anglo-Italian partition proposal, the third uprising in Upper Silesia took place in May and with it the military conquest of those parts of the area that had a high percentage of votes for Poland.

After the referendum, the Inter-Allied Commission had drawn up various partition plans. While those of the English and Italian representatives with the Percival de Marinis line only provided for relatively small assignments of territory outside the industrial area, French plans with the Korfanty line wanted to weaken the German economy by assigning the economically important areas to Poland. At the French initiative, the matter was finally transferred to a League of Nations commission . The ambassadors conference in Paris decided on October 20, 1921 with the Sforza Line, an inner-Upper Silesian border line that remained distant from the original ideas of Korfanty and France, but represented a success of the French partition policy.

With the Sforza Line , an attempt was made to take into account the majority of votes in the municipalities, which was almost impossible, especially in the industrial district, given the widely differing results in rural and urban areas - so individual districts, as well as several cities and municipalities, with partially clear voting results assigned to the respective non-elected state. With effect from July 20, 1922 came the smaller (29 percent), but more densely populated part of Upper Silesia, called " East Upper Silesia " and with it the majority of the Upper Silesian industrial area with half of all smelting works, a large part of the coal and iron ore deposits and the economically important ones Mining regions , to Poland. In this part there was an overall 60 percent majority for Poland. The cities and industrial towns Chorzow (Królewska Huta) , Katowice (Katowice) , Myslowitz (Mysłowice) , Schwientochlowitz (Świętochłowice) , Laurahütte (Huta Laura) , Siemianowitz (Siemianowice Śląskie) , Bismarckhütte (Hajduki Wielkie) , Lipine (Lipiny) , Peace Hut ( Nowy Bytom) and Ruda became Polish. Images of the demarcation of boundaries underground and through industrial complexes or settlements became a symbol of the division, which the German side mostly regarded as unjust and which was never recognized by the German government.

The German-Polish Agreement on Upper Silesia (Geneva Agreement) , signed in Geneva on May 15, 1922, regulated the administrative conditions of the cession and tried to establish minority protection .

Divided Upper Silesia

The larger western part of Upper Silesia remained with Germany ("West Upper Silesia"). On September 3, 1922, a referendum was held in this part of Upper Silesia. B. Prussia was to be decided. However, over 90 percent were in favor of the current status quo , i.e. the continued existence of Upper Silesia in the Free State of Prussia during the Weimar Republic .

On June 20, 1922, the Second Polish Republic took over the ceded " Eastern Upper Silesia " , which was granted extensive independence in the newly founded Autonomous Voivodeship of Silesia . The Autonomous Silesian Voivodeship consisted of Eastern Upper Silesia and the part of Cieszyn Silesia, which became Polish in 1920 .

After the handover of power to the National Socialists, the German-Polish Agreement on Upper Silesia (Geneva Agreement) was still a blessing for many Upper Silesia. In the agreement guaranteed by the League of Nations, each contracting party guaranteed equal rights for all residents of its part of Upper Silesia. After the anti-Semitic discrimination against Jewish Germans began, in May 1933 the Upper Silesian Franz Bernheim turned to the League of Nations with a petition ( Bernheim Petition ) asking that the agreement on Eastern Silesia be effectively enforced. The League of Nations complied with the request and asked Germany to keep the agreement. In September 1933, the Nazi government withdrew the anti-Semitic laws in Upper Silesia and exempted it from new forms of discrimination. Even after Germany left the League of Nations, she kept the agreement so as not to provide Poland with an excuse for her part to regard the agreement as invalid. As a result, in Upper Silesia - in contrast to the rest of Germany - the otherwise valid anti-Semitic discrimination, such as the Aryan Paragraph , the Nuremberg Laws, etc., did not come into effect for the remaining period up to May 1937 .

Second World War

During the attack on Poland in September 1939 , the Wehrmacht conquered Eastern Upper Silesia, which was united with the province of Silesia and thus joined the "Greater German Reich" in violation of international law . In 1941 Upper Silesia was formally re-established as a Prussian province . The capital was not the historical capital Opole, but the larger Katowice, which had already been expanded into the voivodeship capital in Polish times with monumental representative buildings. In addition to Eastern Upper Silesia and the rest of the (formerly Austrian-Silesian) area of the Autonomous Silesian Voivodeship and the Hultschiner Ländchen , which was reintegrated in 1939, the new province also included historically Lesser Poland areas with the cities of Sosnowitz and Jaworzno . However, only the area of the previous Autonomous Voivodeship of Silesia and the western part of the newly delimited district of Bielitz were treated as inland in terms of passport law and the law applicable to Poland, while the remaining annexed area (so-called eastern strip ) was separated by a police border . The Auschwitz concentration camp was established in this area . The considerable Jewish community of Upper Silesia - unless they had already fled or been deported to labor camps - was murdered there and in the extermination camps of Aktion Reinhardt . A policy of racial segregation was pursued in the areas annexed to the Reich after September 1, 1939. There were i.a. Restaurants, shops, parks and sports facilities that Poles were not allowed to enter. The food rations for Germans were 30 to 50 percent higher than for Poles.

Immediate post-war period

At the end of the Second World War , Upper Silesia was conquered by the Red Army in 1945 . The war damage was limited. With the exception of the Hultschiner Ländchen and the Zaolzie Strip , which was taken over by Poland in 1938 and the German Reich in 1939 , both of which came back to Czechoslovakia, Upper Silesia initially came under Polish administration and has also belonged to Poland under international law since 1990. In contrast to Lower Silesia, there was no widespread displacement in the Upper Silesian industrial area for ethnic and economic reasons , as many residents were bilingual. In addition, many Upper Silesians had professional qualifications that could not be replaced in the coal and steel industry at short notice. Anyone who passed a more or less strict Polish language test and was classified as “ autochthonous ” was granted the right to stay. Upper Silesians, who were classified as (only) German-speaking, were given a right of residence if they worked in important industries. After all, around 40 percent of the Upper Silesian population and not more than 90 percent, as in Lower Silesia, were displaced. In particular around Opole and Katowice there remained a German minority that was neither expelled nor resettled .

In 2015, the Documentation Center for the Deportation of Upper Silesians to the USSR in 1945 was opened.

Communist time

The remaining backward population of Upper Silesia, both German and Polish-speaking, had to endure discrimination from the Polish state from 1945 onwards. The Polish state made it its goal to “repolonize” the Upper Silesians whom it declared to be “Germanized Poles”. The use of the German language was forbidden in public life, in churches and schools, as well as in private life. In order to avoid contact with the German language, German was not taught as a foreign language in any of the Upper Silesian areas. The practice of the German language could only be practiced in secret, fearful of being caught. Due to the long period of time, one to three generations did not have the opportunity to learn the mother tongue of their ancestors. The use of the Polish-Silesian dialect, which contained many words of German origin, was also viewed reluctantly. It was not until 1988, after 43 years of prohibition, that a German fair was held again for the first time in Upper Silesia on Annaberg , but it was still illegal.

Tourist Attractions

Pilgrimage site St. Annaberg

The Catholic pilgrimage site of St. Annaberg is located approx. 40 kilometers southeast of Opole in the municipality of Leschnitz . Here you will find the pilgrimage church, a monastery and the 66 cm statue of Anna the third .

Opole

Opole is one of the medieval towns in Upper Silesia. The 13th century Cathedral of the Holy Cross is particularly worth seeing . Other main attractions in Opole are the town hall and the associated ring (market square), as well as the Franciscan church and the mountain church . Additional facilities in Opole, the Museum of Opole village , the Museum of Opole Silesia and the Opole Zoo .

Katowice

The city of Katowice in the Silesian Voivodeship is located in the east of Upper Silesia and, with around 295,000 inhabitants, is the largest city in the two Upper Silesian voivodships. Featured here are St. Mary's Church from 1870, the grist wooden church of Archangel Michael Church in the 16th century, as well as to the classicism held Christ the King Cathedral in the 1930s. Other sights of the city are the Silesian Parliament Building , the Silesian Museum and the Silesian Theater .

More Attractions

Another medieval town in Upper Silesia is Nysa (Eng. Neisse) . In Nysa there is the Jacob's Cathedral and several monuments.

Several cities in eastern Upper Silesia emerged from the age of industrialization, which today can boast a large number of interesting Wilhelminian-style houses and historic buildings and, at the same time, modern architecture.

Schrotholzkirchen

A regional peculiarity of Upper Silesia are the widespread scrap wood churches . These mostly very dark wooden churches, often made of pine wood, can be found, for example, in Powiat Oleski and Powiat Gliwicki . In some towns in the Upper Silesian industrial area you can also find scrap wood churches that were moved there in the 20th century.

Castles and Palaces

- Layout of the former Neudeck Castle

- Moschen Castle

- Pleß Castle (pl: Zamek Pszczyna)

- Castle in large stone

- Castle in Pławniowice (Plawniowitz)

- Toszek Castle (Tost)

- Castle in Koschentin

- Ruins of the Koppitz Castle

population

Most of the German minority in Poland lives in Upper Silesia, especially in the Opole region. Approximately 350,000 inhabitants of Upper Silesia possess not only the Polish , the German nationality .

With access to German and German-language media and German lessons in many schools since the 1990s and regular commuting to work in the Federal Republic of Germany , German (in the standard language ) has been developing into a second language for some time .

The only official language is the Polish standard language .

Although the majority of Poles, Germans and Czechs live in Upper Silesia, today there is a group of Upper Silesians who call themselves exclusively Silesians. At the last census in 2011 that was 376,000 people. There are many causes for this phenomenon, including: the historically strong own identity of the Upper Silesians, the autochthonous Silesians, who call Silesian (Polish dialect) their mother tongue, and also the sanctions by the Polish state from 1945 to 1989 against the population of Upper Silesia.

The denominational composition of the population has largely remained the same over the years. Traditionally, the overwhelming majority of Upper Silesians are of the Roman Catholic faith (around 95 percent), which was a special feature, as the majority in eastern Germany (including Lower Silesia) were Protestant . The evangelical church has lost even more importance as a result of the expulsion of many parishioners - in 1933 its share was still around ten percent.

Since the 1990s, Upper Silesia has been characterized by falling population figures, both in cities and in rural areas. The number of inhabitants fell particularly sharply in many places in the first half of the 2000s.

Autonomy movement

The autonomy movement is relatively young and was only launched in 1990 by chairman Rudolf Kolodziejczyk in Rybnik . It should tie in with the rich traditions of the German era, but also with Silesia under the Second Polish Republic . The current chairman is Jerzy Gorzelik . The main aim is better self-government in the Upper Silesian provinces of Opolskie and Slaskie .

In 2010, RAS (Ruch Autonomii Śląska) had 8.49 percent of the votes in the Silesian Voivodeship Council , i.e. 122,781 votes and three mandates. In 2014, the RAS even received four mandates, despite a decrease to 7.2% of the votes. By contrast, she lost all of her seats in 2018.

Culture

architecture

- Familok (family block)

public holidays

- December 4th: Barbaratag (miners' holiday)

- December 6: St. Nicholas Day

Traditions, customs, festivals

A rural Upper Silesian carnival custom is the winter expulsion or Bear Run . Winter is symbolized by a person disguised as a bear. He is arrested by a person disguised as a police officer. Followed by other people in disguise, the bear is expelled from the village, with a move from house to house beforehand. The bear is also said to represent the evil that is brought out of the place. In some places the bear costume is traditionally made of straw. In the carnival time and the "will Babski Comber " or "Comber" (from the German : Zampern ) celebrated. A carnival festival that is reserved for women, but men disguised as women are also allowed entry.

There are different customs at Easter . A custom on Easter Monday that was widespread throughout Silesia was the Schmackostern . While in Lower Silesia the girls were beaten with a rod decorated with ribbons, in Upper Silesia they were mostly doused with water, comparable to the Polish Śmigus-dyngus , which is also referred to as Easter pouring . In the past, watering was sometimes combined with rod striking or in some places only the variant with the rod was widespread. With the Polonization of Upper Silesia, the rods have become rather unusual. The boys (and men) then await a present. Mostly these are painted Easter eggs or nowadays also sweets, but in the past they were also cakes, coffee and yellow bread. Girls (and women) can taste Easter on Easter Tuesday. Another Easter custom is the Easter riding , which still takes place in some places today.

At the harvest festival , the so-called harvest festival in Upper Silesia , a procession takes place, the “ harvest crown ” or “harvest wreath” is carried ahead . For this occasion, several floats are decorated and mostly funny motifs are designed. The people who drive these cars are disguised. In addition, banners with slogans are attached. At the end there will be a party with food, music and dance.

Since the fall of the Wall, more and more places and communities have been celebrating October festivals based on the Bavarian model .

The symbol figure of the Christ child is very common among the Upper Silesians at Christmas . In other regions in Poland, such as B. the neighboring Lesser Poland, this custom is unknown.

The most important family celebrations of the Upper Silesians include the baptism , first communion and birthday , most notably the first birthday and the fiftieth anniversary ( Abrahamstag ), the important Polish name day , however, has no meaning and is not celebrated.

A Silesian wedding include in the wedding celebration of the eve and the day after the wedding the Nachfeiern.

kitchen

Costume

Traditional costumes were worn in Silesia until the middle of the 19th century. In some regions and places (e.g. in Schönwald ) the tradition partly survived into the 20th century, but since then traditional costumes have generally been considered old-fashioned.

A distinction was made between everyday, Sunday and holiday costumes.

Today traditional costumes are hardly widespread and are worn exclusively by traditional costume groups or are exhibited in museums or local parlors. Traditional costumes are worn at some folk festivals, but are no longer relevant in everyday life.

media

In the area of Upper Silesia are TVP Info regional window TVP Opole and TVP Katowice the Polish state television TVP received too. In addition, the private television broadcaster TVS is aimed at viewers in the Silesian Voivodeship. Another broadcaster is TVT .

Regional radio stations are the stations Polskie Radio Opole and Polskie Radio Katowice of the state radio station Polskie Radio . A private Upper Silesian broadcaster is Radio Piekary.

Radio Mittendrin is a German-Polish internet radio station belonging to the German minority .

Personalities

Five Nobel Prize winners come from Upper Silesia. Otto Stern from Sohrau was expelled from Germany as a Jew in 1933. He took US citizenship and was very successful as a scientist. He received the Nobel Prize in Physics as a professor in Pittsburgh in 1943 . In 1963, Maria Goeppert-Mayer, born in Katowice, received the same award. Kurt Alder, born in Königshütte, received the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1950 . In 1964 Konrad Bloch , a professor of biochemistry at Harvard University, who was born in Neisse and was expelled from Germany as a young scientist because of his Jewish descent, received the Nobel Prize for Medicine .

Ernst Friedrich Zwirner , born in Jakobswalde , district of Cosel , province of Silesia , was a German architect and master builder of Cologne's cathedral .

Oscar Troplowitz , a German pharmacist , entrepreneur and patron of the arts , who was born in Gleiwitz , Opole District , Province of Silesia and who took over the Beiersdorf company a few years after it was founded (1890). developed the world-famous branded product “Nivea Creme” (1911).

The most famous writers in Upper Silesia include Joseph von Eichendorff , Horst Bienek and Horst Eckert, known as Janosch . Joseph von Eichendorff created, among others. the novella " From the life of a good-for-nothing ". Janosch obtained, inter alia. Famous for his story " Oh, how beautiful is Panama ". Horst Bienek created several works about his homeland Gleiwitz and Upper Silesia. In the work of the writer Wolfgang Bittner there are also references to his hometown Gleiwitz and to Upper Silesia. The zoologist and publicist Bernhard Grzimek, born in 1909, comes from Neisse . From 1956 to 1980 he produced the TV series "Ein Platz für Tiere" (A Place for Animals) for ARD. Another famous Silesian personality who linked their fate with Africa was Eduard Schnitzer . The Upper Silesian (born in Opole in 1840) went down in history as Emin Pascha. The Africa explorer and governor of the Sudanese province of Equatoria served as a model for the characters of Karl May .

In the predominantly Roman Catholic region, a.o. the theologians and bishops Walter Mixa from Königshütte and Alfons Nossol from Broschütz were born near Walzen.

From Rybnik born in 1978, German pop / rock singer and songwriter comes Thomas Godoj (actually Tomasz Jacek Godoj), which by the TV station RTL broadcast talent show Germany Idol (DSDS) won of 2008.

Along with other football players, Miroslav Klose , born in Opole, and Lukas Podolski, born in Gliwice, come from Upper Silesia. Both played or play for the German national team and became world champions in 2014.

See also

- Landsmannschaft der Oberschlesier

- Upper Silesian State Museum

- Federation of Upper Silesians

- Upper Silesia (newspaper)

- Church tracing service

- Lower Silesia

literature

- Walter Geisler : Upper Silesia Atlas . With the collaboration of numerous experts, Volk und Reich Verlag, Berlin 1938.

- Felix Triest (Hrsg.): Topographisches Handbuch von Oberschlesien. Breslau 1865, 1292 pages

- Alder Bach: Upper Silesia. From the Sudetenland to the Upper Silesian Plate. Flechsig 1998, ISBN 3-88189-218-4 .

- Writings of the Haus Oberschlesien Foundation / Haus Oberschlesien Foundation <Ratingen>, Berlin 1990.

- Wolfgang Bittner : Gleiwitz is now called Gliwice / Gliwice zwano kiedys Gleiwitz. Oberhausen / Wrocław 2003, ISBN 3-89896-161-3 / 83-88726-11-0.

- Daniela Pelka: The German-Polish language contact in Upper Silesia using the example of the Oberglogau area. trafo, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-89626-524-5 .

- Gregor Ploch, Jerzy Myszor , Christine Kucinski (eds.): The ethnic-national identity of the inhabitants of Upper Silesia. Münster 2008.

- Bernhard Sauer: "Off to Upper Silesia" - The fighting of the German Freikorps in 1921 in Upper Silesia and the other former German eastern provinces. In: Journal of History. 58th year 2010, issue 4, pp. 297-320. ( PDF, 7.6 MB )

- Silke Findeisen (Ed.): Journey to the old homeland - Silesia in 1000 pictures. Königswinter 2010, ISBN 978-3-941557-20-8 .

- Herbert Gross: Important Upper Silesians. Short biographies. Laumann, Dülmen 1995, ISBN 3-87466-192-X .

- Joseph Partsch . 1896. Silesia: a regional study for the German people. T. 1., The whole country . Breslau: Verlag Ferdinand Hirt.

- Joseph Partsch . 1911. Silesia: a regional study for the German people. T. 2., Landscapes and Settlements . Breslau: Verlag Ferdinand Hirt.

- Lucyna Harc et al. 2013. Cuius Regio? Ideological and Territorial Cohesion of the Historical Region of Silesia (c. 1000-2000) vol. 1., The Long Formation of the Region Silesia (c. 1000-1526) . Wrocław: eBooki.com.pl ISBN 978-83-927132-1-0

- Lucyna Harc et al. 2014. Cuius regio? Ideological and Territorial Cohesion of the Historical Region of Silesia (c. 1000-2000) vol. 2., The Strengthening of Silesian Regionalism (1526-1740) . Wrocław: eBooki.com.pl ISBN 978-83-927132-6-5

- Lucyna Harc et al. 2014. Cuius regio? Ideological and Territorial Cohesion of the Historical Region of Silesia (c. 1000-2000) vol. 4. Divided Region: Times of Nation-States (1918-1945) . Wrocław: eBooki.com.pl ISBN 978-83-927132-8-9

- Paul Weber. 1913. The Poles in Upper Silesia: a statistical study . Julius Springer's publishing bookstore in Berlin

- Norbert Morciniec : On the vocabulary of German origin in the Polish dialects of Silesia. Zeitschrift für Ostforschung, Vol. 83, Issue 3, 1989.

- Robert Semple. London 1814. Observations made on a tour from Hamburg through Berlin, Gorlitz, and Breslau, to Silberberg; and thence to Gottenburg

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Grzegorz Chromik: Medieval German place names in Upper Silesia . In: Kwartalnik Neofilologiczny . LXVII (3/2020), Kraków, 2020, pp. 355–374.

- ^ Reinhold Vetter: Silesia - German and Polish cultural traditions in a European border region. DuMont Verlag, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-7701-4418-X , p. 34.

- ^ Reichstag election card of the German Reich: based on the results of the elections of January 25, 1907, taking into account the runoff and by-elections, Verlag G. Freytag & Berndt, Leipzig, Vienna, 1907

- ↑ See Wahlen-in-deutschland.de . Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ↑ Georg Hassel: Statistical outline of all European and the most distinguished non-European states, in terms of their development, size, population, financial and military constitution, presented in tabular form; First issue: Which represents the two great powers Austria and Prussia and the German Confederation. Verlag des Geographisches Institut Weimar (1823), p. 34; Total population 1819 - 561.203; National Diversity 1819: Poland - 377,100; Germans - 162,600; Moravians - 12,000; Jews - 8,000 and Czechs - 1,600 ( books.google.pl ).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Paul Weber , The Poles in Upper Silesia: a statistical study; Julius Springer's publishing bookstore in Berlin (1913), pp. 8–9

- ↑ a b c d Paul Weber: The Poles in Upper Silesia: a statistical study; Julius Springer's publishing bookstore in Berlin (1913), p. 27 ( archive.org ).

- ↑ Appendix VIII to the Versailles Treaty, concerning § 88

- ↑ See this website by Falter et al. 1986, p. 118.

- ^ The referendum in Upper Silesia in 1921 (home.arcor.de)

- ^ Neue Freie Presse, edition of March 20, 1921, p. 5.

- ↑ Andreas Kieswetter: Italy and Upper Silesia 1919-1922 , documents on Italian politics, publishing Königshausen and Neumann, Würzburg 2001, p 41-90.

- ↑ Dieter Lamping: About Limits , 2001, p. 58.

- ↑ Target in Palazzo Chigi . In: Der Spiegel . No. 13 , 1948 ( online ).

- ↑ a b “German-Polish Agreement on Upper Silesia” (Upper Silesia Agreement, OSA) of May 15, 1922, in: Reichsgesetzblatt , 1922, Part II, p. 238 ff.

- ↑ gonschior.de

- ^ Philipp Graf: The Bernheim Petition 1933: Jewish Politics in the Interwar Period. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2008, (Writings of the Simon Dubnow Institute; 10), 342 pages, ISBN 978-3-525-36988-3 .

- ↑ "Ordinance on the restriction of travel with parts of the territory of the Greater German Reich and with the Generalgouvernement" of July 20, 1940, Paragraph 1, Paragraph 1 Number b). , she mentions an inclusion only of the city of Biala, which is intertwined with Bielitz

- ↑ “First Ordinance for the Implementation of the Ordinance on the Collection of a Social Compensation Tax” of August 10, 1940, Paragraph 7 ; she names a border line along the Soła .

- ^ Franz-Josef Sehr : Professor from Poland in Beselich annually for decades . In: Yearbook for the Limburg-Weilburg district 2020 . The district committee of the district of Limburg-Weilburg, Limburg-Weilburg 2019, ISBN 3-927006-57-2 , p. 223-228 .

- ^ Tourism Poland: Poland - Kattowitz (Katowice) ( Memento from February 9, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ National and Ethnic Affiliation, Main Statistical Office, 2011 Census (Polish)

- ↑ See Michael Rademacher: German administrative history from the unification of the empire in 1871 to the reunification in 1990. p_schlesien.html # rboppeln. (Online material for the dissertation, Osnabrück 2006).

- ^ Franz Schroller: Silesia - A description of the Silesian country. Third volume, p. 249 .