Cesky Silesia

The Teschener Silesia (also Teschener Raum , Teschener Land , Teschenergebiet ; Polish Śląsk Cieszyński , Czech Těšínsko or Těšínské Slezsko ) is a historical landscape on the Olsa River , which was the eastern part of the Crown Land of Austro-Silesia in the last decades of the Habsburg Monarchy and before that the Duchy of Teschen had once formed. The area formed a historical-cultural unit until the end of the First World War , but was then divided between Czechoslovakia , now the Czech Republic , and Poland . Historically, the area also belongs to Upper Silesia , but a Silesian, but separate regional identity has developed among the local population and they do not identify as Upper Silesia.

The area has an area of 2283 km² (comparable to Luxembourg ), of which 1274 km² (55.8%) in the Czech Republic and 1009 km² (44.2%) in Poland, over 800,000 inhabitants, of which around 463,000 in the Czech and around 350,000 in the Polish part.

Surname

In the older spelling, the adjective Teschener was also written as Teschner , e.g. B. in the name of the Teschner Kreis . After the abolition of patrimonial rule in the middle of the 19th century, the use of the names of the duchies, barons etc. largely lost their meaning. In Austria the area was called Eastern Silesia from 1870 to 1921, as well as in Polish Śląsk Wschodni . The name Śląsk Cieszyński spread in Poland in the interwar period and was also used on February 9, 1919 in a memorial of the Silesian People's Party. The name Zaolzie and Śląsk Zaolziański for the traditionally Polish- speaking part of the region in Czechoslovakia also seeped into the official Polish documents.

In 1938/39, an area of 869 square kilometers in the Czechoslovakian part was annexed by Poland in violation of international law as a result of the Munich Agreement . In German it was mostly called the Olsa region in the interwar period , but it was also called the Olsa country . The Polish name Zaolzie , more rarely Śląsk Zaolziański , Czech Záolží or Záolší denotes [an area] behind the Olsa . Sometimes the term Olsa only refers to this area, but during the Second World War the name was used for the entire district of Teschen . In Polish, too, names like Nadolzie ([the area] on the Olsa ), Kraj Nadolziański , etc. were used as synonyms for Śląsk Cieszyński , referring to the central river.

In the People's Republic of Poland , new regional names were often used in slang, which were adapted to the new administrative units, such as B. Cieszyńskie or ziemia cieszyńska for Powiat Cieszyński and Podbeskidzie for the Bielsko-Biała Voivodeship . Similarly, in Czechoslovakia Karvinsko and Jablunkovsko designated parts of the area, but z. B. Ostravsko could encompass the whole of Českotěšínsko .

After 1989, regional identities flourished again, as did memories of the older names of the historical landscapes. The name Teschener Silesia prevailed for the Euroregion founded in 1998 .

geography

The borders of Cieszyn Silesia were initially outlined as a Polish castellany , but in their final form (with Bohumín / Bogumin / Oderberg) only crystallized after the First Silesian War (1742), when it was crossed by the state border from Prussian Silesia, as well was clearly separated from the western part of Austrian Silesia by the Moravian wedge around Mährisch Ostrau .

The area is located on the Olsa River, a right tributary of the Oder , in the West Beskids , West Beskid foothills and in the Ostrava Basin and Auschwitz Basin , northeast of the Moravian Gate , a valley at an altitude of 310 m between the Sudetes and the Carpathians. Historically, the area was a crossroads from Prague and Vienna through the Moravian Gate to Krakow, and from Wroclaw through the Jablunka Pass to Hungary .

The western border runs along the whole of Ostravice (Polish Ostrawica) - from the source of the Black Ostrawitza in the south to the confluence with the Oder in the north. Then the border goes like the border between Poland and the Czech Republic - downstream of the Oder to the mouth of the Olsa. The northern border, with the exception of the stretch between Petrovice / Piotrowice in the west and Strumień (a marshland in the early Middle Ages), runs along the Olsa and Vistula, the largest river in Poland, which begins in the town of the same name . The Biała constitutes the eastern border, together with the Barania ridge in the Silesian Beskids . In the south lies the main European watershed of the Western Carpathians , with the exception of the Czadeczka with its tributary Krężelka, which belong to the tributary area of the Danube . The highest mountain is Lysá hora / Łysa Góra (1325 m) in the Moravian-Silesian Beskids in the Czech Republic, while for the Polish part it is Barania Góra (1220 m).

Administratively, the region comprises the entire powiat Cieszyński and the western parts of the powiat Bielski and the independent city of Bielsko-Biała in the Silesian Voivodeship in Poland, as well as in the Czech Republic the entire district of Okres Karviná , and the eastern parts of Okres Frýdek-Místek and Okres Ostrava -město in the Moravian-Silesian region .

history

prehistory

In 2004 and 2005 traces of Homo erectus were found in Kończyce Wielkie , 800,000 years old, the oldest in Poland.

The intensification of the colonization by Homo sapiens came with the Gravettian culture. The first farmers from the later Lengyel culture did not settle until the fourth millennium BC. Chr. During the Bronze Age , the region became a fairly sparsely populated communication route. Only in the late Bronze Age and in the early Iron Age did a civilization boom with the Lausitz culture begin . The numerous Lusatian settlements were probably founded by Scythians at the turn of the 5th century BC. Attacked. The castle wall in Chotěbuz / Kocobędz was then further settled in the Latène period, when southern Poland came under the influence of the Celts . There was a settlement on the castle hill in Teschen , but without fortifications. A larger and well-researched settlement chamber of the Puchau culture and a Celtic oppidum on Mount Kotouč in Štramberk was located in the west, behind the Ostrawitza. From the time of the Roman influence before the Great Migration , mainly only Roman coins were found for a long time , but ultimately traces of larger, presumably Germanic settlements in Łazy and Kowale also appeared. However, they are poorly researched and not classified more precisely.

Early history

Archaeologists found two ramparts from the 7th century during the Slavic tribal era in the area, in Chotěbuz / Kocobędz and Międzyświeć . The German researcher Gottlieb Biermann they initially classified as a castle ramparts of Vistulans in 1867, but modern research connects most with the Bavarian geographer mentioned tribe of golensizi (with five civitates within the meaning of Slavic castle ramparts , with accompanying vicinia s, compare County ) - what was rejected or questioned by the minority of researchers. Because of the location of the two ramparts, they had to play a political role in the relations between the Wislanes and the Moravians. Both castle walls were most likely burned down by Svatopluk I in the late 9th century . The supposed subsequent connection to the Moravian Empire has often been doubted by various historians, but not the increase in Moravian influence. If Kraków belonged to the Bohemian Přemyslids in the second half of the 10th century , so did the Golensizen area. The area was probably taken over by the Piasts around 990 . Many historians connect the likely time-built castle wall in Kylešovice , a district of Opava with the Piast dynasty, the castle wall in Chotěbuz / Kocobędz politically shelters. At that time, Boleslaw I. Chrobry (= "the brave") of Poland occupied the whole of Moravia until 1019, but in the late 1030s the Piasts fell in power, which was exploited by Bohemia. After the assembly in Quedlinburg in 1054, the Golensizen area could have become part of Bohemia, but it is not entirely certain whether the Olsa area was still a unit with the area around Hradec nad Moravicí . The Polish-Bohemian War in the area in the 1130s was passed down much better in the documents, and the Pentecostal Peace of Glatz from 1137 is a turning point that leaves less ambiguity. The chapel of St. Nicholas and St. Wenceslas , the oldest brick building in Cieszyn Silesia, and a well-known symbol of the landscape, was built at the earliest under Boleslaw Chrobry from this period.

The first written mention of Tescin (but the identification with Teschen is sometimes controversial) comes from a document of Pope Hadrian IV. In 1155, namely among the most important places, later the seats of the castellanias in the diocese of Wroclaw or Duchy of Silesia , as it was ruled by Bolesław IV of Poland . From 1172 the area belonged to the Duchy of Ratibor , while the rest of the tribal area of the Golensizen belonged to the Margraviate of Moravia , in 1201 it was mentioned as a province of the Golensizen, from which the Duchy of Opava later emerged.

Political and ecclesiastical affiliation influenced separate developments in local dialects. The first traces of the language of the local population come from documented mentions of place names in Latin-language documents. At that time, the old forms of the Polish and Czech languages were much closer to each other than they are today, but the nasal vowels present in these names help categorize this form of language as the Lechic languages , not the Czech-Slovak dialects. The second linguistic characteristic, best recognizable in ancient sources, which distinguishes the old Teschen dialects from the Moravian Lachish languages , is the lack of spirantization g ≥ h (in Teschen dialects, as in Polish, g retained, Lachish and Czech-Slovak dialects replaced it for h).

Kastellanei Teschen

In the 13th century in Poland, the term castellany was a district administered by a castellan. The castellany comprised the castle district, the land in the vicinity of a permanent castle (fort) that was owned by the sovereign. The castellan exercised rule and jurisdiction there in the name of the sovereign, he was responsible for the army administration of the district.

On May 23, 1223, the first fourteen villages in the castellatura de Ticino were mentioned in a document from the Breslau bishop Lorenz , which was also the first explicit name of the castellany and of Teschen as a city. A few years later, ten other villages in the possession of the Tyniec Abbey appeared, including today's Slezská Ostrava on the Ostrawitz River. On the other side of this river - in Moravia - a settlement campaign was introduced by Arnold von Hückeswagen , which was intensified after his death (1260) by Olomouc Bishop Bruno von Schauenburg . Around the year 1260 (in literature the incompletely preserved document was dated from 1256 to 1261), Duke Wladislaus I decided to regulate the border of the Duchy of Opole-Ratibor with Ottokar II along the Ostrawitza (at that time Oderberg / Bogumin / Bohumín and Hruschau / Hruszów / Hrušov mentioned for the first time), and to settle Tyniecer Benedikter in Orlau in order to strengthen the border area near Moravia. Apart from that, no major settlement campaigns were carried out in the castellany of the Opole dukes and until the creation of the Duchy of Teschen there were around 40 villages in this underdeveloped area, largely a mountainous area on the periphery of the Duchy of Opole-Ratibor.

Duchy of Teschen under the Piasts

In 1280 the Duchy of Opole-Ratibor began to collapse and only at the end of 1289 or in 1290 Teschen became the residence of Mesko I from the Silesian Piast . The first Piast Duke of Teschen, Mesko I , initiated extensive colonization under German law by locators , in which around 70 new places, mostly Waldhufendörfer , were founded, but also the cities of Freistadt and Bielitz. The descendants of the German settlers around Bielitz formed the German Bielitz-Biala language island until the end of the Second World War in May 1945 , which was wiped out by flight and expulsion . In addition to the area between Ostrawitza and Bialka, the Teschen branch of the Silesian Piasts also ruled various other parts of the country in the neighborhood (e.g. Auschwitz , Pless , Siewierz ), but the landscape of Teschen Silesia is only with the core of the duchy or the former Castellany connected.

In 1297 the area of the duchy was called Polonia (Poland), but together with the other Silesian duchies, the duchy also came under the sovereignty of the crown of Bohemia in 1327 . In 1315 the Duchy of Auschwitz was separated. After 1430, especially 1450, the Czech official language almost completely replaced the previous official languages Latin and German (except in Bielitz ) in the duchy. Around 1494 an immigration of Wallachians from the eastern Carpathians began, most of whom settled in the mountains. Under Duke Wenceslaus III. Adam was introduced in the Duchy of Teschen at the earliest from 1545 (indisputably in the 1560s) the Reformation for the residents in inheritance as a change of faith to the Evangelical-Lutheran creed. Both events introduced folk peculiarities in the landscape, which partly distinguish it from the rest of Upper Silesia to this day.

In the late 15th century, the name Silesia Superiori or Upper Silesia appeared for the first time , at the same time as the establishment of several supraregional institutions by the Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus , who conquered the eastern part of Silesia and strove for its consolidation. The Duchy of Teschen was then regarded as an essential part of Upper Silesia, but remained outside of the Duchy of Opole under John II , who then reunited the majority of Upper Silesia after the 13th century. At that time, however, the village of Strumień (Schwarzwasser) was raised from the rule of Pless under Casimir II of Teschen to the status of a city and incorporated into the Duchy of Teschen.

The history of the part of Silesia and the Duchy of Teschen between the Ostrawitza and Bialka drifted apart due to the territorial disintegration in the 16th century. In 1560 the area around Bielitz was together with Fryštát (German: Freistadt) and Frýdek (German: Friedek) by Duke Wenzel III. Adam was transferred to his son Friedrich Kasimir during his lifetime . After his death in 1571, the indebted manor of Bielitz was sold to Karl von Promnitz on Pless in 1572 with the consent of Emperor Maximilian II and placed under the royal office in Wroclaw . In a similar way, the manors around Fryštát and Frýdek were permanently separated from the duchy. The minority rule Skoczów - Strumień (German Skotschau – Schwarzwasser) was incorporated into the Duchy of Teschen after a few decades. The Duchy of Teschen, however, was often combined with the neighboring class lords (and with the Duchy of Bielitz ), e.g. B. on the maps. The common social consciousness survived to a certain extent in the separated class lords, among other things through the resistance against the Habsburg counter-reformation (among the Lutherans) or the membership of the Roman Catholic deanery of Teschen, later of the Austrian vicariate general of the diocese of Breslau (under the Roman -Catholics).

Under the Habsburgs

After the death of Duchess Elisabeth Lukretias in 1653, the Teschen branch of the Silesian Piast family died out . The duchy fell as a settled fiefdom to the Crown of Bohemia , which had owned the House of Habsburg since 1526 . The Habsburgs initiated the re-Catholicization of the subjects in the Duchy of Teschen , especially in the Teschen Chamber ; otherwise they showed little interest and neglected the administration in the duchy. In the year 1707 in Silesia with the Altranstädter Convention , which the Swedish King Charles XII. had enforced, allowed the Evangelical Lutheran believers to build the " Silesian grace churches ". The largest of them, the Jesus Church in the city of Teschen, is still a Protestant church today after 300 years. For several decades it was the only Protestant church in Upper Silesia, then after the First Silesian War in Austrian Silesia until 1781 .

In 1722, Emperor Charles VI separated. the hereditary duchy of Teschen from Bohemia and handed it over to Leopold Joseph Karl von Lothringen , the father of the later Emperor Franz I Stephan . After the preliminary peace of Breslau , which ended the First Silesian War in 1742, the Duchy of Teschen remained with Austria and the eastern part of Austrian Lower and Upper Silesia , from the 1870s onwards, was also called East Silesia for short .

The tolerance patent of Emperor Joseph II in 1781 made it possible to revive church-Protestant life in Cieszyn Silesia. At that time, the following municipalities were established until 1848: Old Bielitz , Bielitz, Ernsdorf , Bludowitz , Kameral Ellgoth , Weichsel , Bistrzitz , Ustron , Golleschau , Nawsi , Drahomischl . Altogether with Teschen 13, the largest accumulation in Cisleithanien .

Growing importance

A fundamental change under the Habsburg administration came in 1766, when the son-in-law of Empress Maria Theresa , Prince Albert Casimir von Sachsen-Teschen , son of the Saxon Elector August III. , ruled under the title Duke of Saxony-Teschen until 1822. The Duke enlarged the Teschen Chamber ; Due to its skillful economic policy and, after 1772, its favorable location on the way from Vienna to Galicia , the area became one of the most economically successful in the Habsburg monarchy as industrialization began. In 1797 the minority Friedek was bought by him and administered together with the Teschen Chamber, in some way reunited with the Duchy of Teschen. In the years 1783–1850, the entire landscape belonged to the Teschner Kreis in the Moravian-Silesian state gubernium. In 1849 Teschen again became part of the Crown Land of Austrian Silesia ; after Hungary left the empire in Austria-Hungary , it was part of Cisleithania .

Since the middle of the 19th century, with the strongly accelerated industrialization, the area around Teschen, between Freistadt and Ostrau , developed into one of the most important Austrian centers of hard coal mining and iron smelting . It was connected to the central area around Vienna by the Kaiser Ferdinands-Nordbahn , the first main line of the monarchy .

National conflicts

The numerous Czech-language documents from the area led some Czechoslovak linguists around the middle of the 20th century to the conclusion that the area was originally Czech and was only Polonized later, at the earliest in the 17th century. The Polish researchers, on the other hand, ensure that z. B. the nasal vowels remained uninterrupted in the place names in the simultaneous German-language and ecclesiastical Latin documents.

Although the ducal chancellery remained Czech-speaking even after 1620 , longer than in Bohemia itself, the documents increasingly written by the local population from the 16th century onwards were often only apparently written in the official language. An invoice from a locksmith from Freistadt in 1589 contained so many “errors” that it was referred to in Polish literature as the first Polish document from Cieszyn Silesia. Shortly afterwards, Johann Tilgner, a self-proclaimed German from Breslau, settled in the Duchy of Teschen. Having learned the Moravian language, he came to be the overseer of the Skotschau-Schwarzwasser estate under Duke Adam Wenzel . In his diary under the title Skotschau Memories , however, he described how he learned the Polish language from the local population. In the second half of the 17th century, this language was named in the reports of the episcopal visitations from Wroclaw concio Polonica (conc + cieō - “summoned”, or the language of the sermon). The linguistic boundary to the concio Moravica did not coincide with the boundary of the deaneries and was similar to the boundary in the middle of the 19th century. The Reformation divided the Polish-speaking population in particular, and for a long time religious identity was more important than ethnic identity, and mutual relations between the two societies were limited. In 1790 there were 86,108 (70.72%) Roman Catholics and 35,334 (29.02%) Protestants in the region. In 1800 the Austrian administration categorized 73% of the residents as a Polish nation (however, according to the modern understanding of the concept, they were nationally indifferent). The spoken Polish-Silesian language seeped through especially in the diaries or quasi-official chronicles of the village scribes. One of the most famous examples was written by Jura (Jerzy, Georg) Gajdzica (1777–1840) from Cisownica . Depending on the training of the scribe, different levels of code switching between Czech, Moravian, Silesian and Polish were observed, which obviously did not hinder communication between Slavs, in contrast to the language barrier that often existed in reality between Slavs and Germans, which later enabled the quick Czechization.

After the First Silesian War, the area was separated from the rest of Silesia by the Austro-Prussian border. The Upper Silesian dialect, so far under comparable influence of the Czech official language, increasingly came under the influence of the German language, especially after 1749, and was called somewhat pejoratively in German Water Polish . This phenomenon was noticeably delayed on the Austrian side of the border. In 1783, the Teschner district was attached to the Moravian-Silesian Provincial Government with its seat in Brno and the Moravian-language textbooks were used in the elementary schools , despite z. B. the protests of Leopold Szersznik , the overseer of the Roman Catholic schools in the district. Reginald Kneifl , the author of the topography of the kk share in Silesia from the early 19th century, on the other hand, used the term Polish-Silesian (more rarely Polish and water Polish) for the majority of the localities in the region. However, the term water Polish was also used later by Austrians in the 19th century, e.g. B. by Karl von Czoernig-Czernhausen .

In 1848 Austrian Silesia regained administrative independence. Paweł Stalmach initiated the Polish national movement by the issue of Polish-language weekly paper Tygodnik Cieszyński (1851 Gwiazdka Cieszyńska ), the first newspaper in Cieszyn Silesia, although the majority of Wasserpolaken remained nationally indifferent for several decades. It was not until 1869 that Stalmach organized the first massive Polish rally in Sibica (Schibitz) near Teschen. In 1860, at the suggestion of Johann Demels , the long-time mayor of Teschen, the Polish and Czech languages became the auxiliary languages of the Crown Land. This led to the unhindered development of the Polish language in authorities and elementary schools for the first time in the history of the area. The middle schools remained exclusively German-speaking. In 1873 Stalmach's Gwiazka Cieszyńska successfully applied for the candidacy of Andrzej Cinciała , who won the Reichsrat election in the Bielsko district , with over 50% of the Protestant voters. In 1874 he proposed the opening of a Polish teacher training college in Teschen and a Czech one in Opava in the Reichsrat . This was strongly contradicted by Eduard Suess because, according to him, the local language was not used in books but Polish, a mixture of Polish and Czech . During this time, the level of prestige of the German language in Cieszyn Silesia was at its height. The percentage of German-speaking residents in small towns such as Skotschau and Schwarzwasser rose to over 50% by the early 20th century. At the end of the 19th century, Archduke Friedrich (Marquis Gero) undertook, with little success, a Germanization of the rural water-Polish area. The counterweight to the Polish national movement has always been the so-called Schlonsak movement, especially widespread among the Lutherans around Skotschau. The departure from Teschen in 1875 by Leopold Otto , who despite his German origins was described as an enthusiastic “Polish patriot”, was symbolic . In his place came Theodor Karl Haase from Lemberg , who gradually rose to become superintendent. He became the most influential German liberal in the area and reversed the progress of the Polish movement under the Lutherans. a. In 1877 he founded the newspaper "Nowy Czas" for this purpose. After Haase's death, Józef Kożdoń gave the movement a new quality and in 1909 founded the Silesian People's Party. He never denied that the Teschen dialects were a dialect of the Polish language, but compared the situation in the region with Switzerland , where the German dialects did not make Germans out of Swiss and, analogously, the Silesians were not Poles. He was very benevolent towards the parallel meaning of the German language and viewed the protests against the dominant role of German culture and politics as a disruption of the old Silesian peace. Under the slogan “Silesia the Silesians!” (Śląsk dla Ślązaków), the movement also turned against the cheap workers who immigrated from Galicia from the 1870s and 1880s (1910 54,200 of 434 thousand, or 12.7%, mostly in one of the largest mining areas Austria-Hungary between Ostrau and Karwin), among which Polish socialists were particularly active. German, Jewish and Czech bourgeoisie and intelligentsia also came to the area . The latter also revived the Czech national movement in individual traditionally water-Polish communities. As early as the 1880s, some Polish national activists and the largest German-language newspaper Silesia complained about the rise in the importance of the Czech national movement around Karwin, and in the 1890s the radical Polish faction with the newspaper Głos Ludu Śląskiego (Call of the Silesian People ), who saw the Czechs and not Germans as the greatest opponent and considered a coalition with Germans against Czechs. In all seriousness, a national conflict flared up between Poles and Czechs in the early 20th century, culminating in the Polish-Czechoslovak border war in 1919. Gwiazdka Cieszyńska declared the end of Polish-Czech solidarity in 1902. At that time, Petr Bezruč popularized the theory of the Polonized Moravians in the Silesian Songs (also a basis for arguments in Beneš Memorandum No. 4: The Problem of Cieszyn Silesia ) and the Czech activists at that time claimed that the Moravian language was actually more understandable than the Polish literary language for the local Silesians. There were disputes about the language in churches, e.g. B. in the parish established in 1899 in Dombrau , as well as the schools: Polish in Polish-Ostrava and Czech in Reichwaldau. The Young Czechs prevented the project of opening the Polish technical school in Orlau for a long time. Ferdinand Pelc, the chairman of the Czech School Association later wrote about it:

“It was clear to us that if we lose Orlau, the fate of the whole area and thus the area of Teschen would be decided. Therefore, the Polish step must be paralyzed, even with the largest possible donations. "

The Shlonsak movement in the Moravian-Lachian district of Friedek was pushed back by the young Czechs in the late 19th century, but Erwin Goj (born in 1905 in Friedek) animated a similar Lachian movement, sometimes described as Józef Kożdoń the Lachei, in the 1930s . However, he called his nation the Lachen , which after him comprised 2 million people, not only in the Silesian and north Moravian Lachei, but also in all of Cieszyn Silesia and southern Prussian Upper Silesia, as well as around Čadca in Slovakia. On the basis of the Lachish dialect ( Oberostrauer dialect ) he created his first literary works in a regional Lachish literary language in the 1930s.

At that time, the area was divided into political districts: Bielitz-Land , Freistadt , Friedeck-Land , Teschen district and Bielitz and Friedeck as cities with their own status. The election results of the Reichsrat elections in 1907 and 1911 provide additional insight into the national political attitudes in individual municipalities, especially in the constituencies of Silesia 13 , Silesia 14 and Silesia 15 , where Polish politicians such as Jan Michejda and Józef Londzin , or the socialists Ryszard Kunicki and Tadeusz Reger with Shlonsak activists, primarily against Józef Kożdoń.

The Austrian censuses from 1880, 1890, 1900 and 1910:

| year | Check- residents |

Polish- speaking |

Czech- speaking |

German speakers |

Roman Catholic | Evangelical | Jews |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 262,412 | 153,724 (58.8%) | 71,788 (27.3%) | 36,865 (14%) | |||

| 1890 | 293.075 | 177,418 (60.6%) | 73,897 (25.2%) | 41,714 (14.2%) | |||

| 1900 | 361.015 | 218,869 (60.7%) | 85,553 (23.7%) | 56,240 (15.5%) | |||

| 1910 | 426,667 | 233,850 (54.8%) | 115,604 (27.1%) | 76,916 (18.1%) | 328,933 (75.7%) | 93,566 (21.5%) | 10,965 (2.5%) |

division

In late May 1918, the German People's Council for Eastern Silesia was founded in Teschen , a union of German parties in the area. The politicians from Bielitz were most active in this, but the council was also supported by other city administrations. He strove to remain with Austria, and if that were not possible, to join Germany.

After the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy at the end of the First World War in 1918, the establishment of the successor state Czechoslovakia and the re-establishment of a state in Poland , a race broke out in October 1918 between Czechoslovakia and Poland for the occupation of this industrially profitable area. On October 26, 1918, at a demonstration by tens of thousands of members of the Polish population in Teschen, a banner was carried with the slogan “Wag, Ostrawica - Polska granica” ( Waag , Ostrawitz - Polish border). This became a sentimental revisionist slogan, but never became an official Polish claim to territory. The Polish National Council of the Duchy of Teschen renounced the Friedek district, the government of Czechoslovakia claimed all of Austrian Silesia as far as Bialka, while the city administrations of Bielitz and Teschen wanted to join German Austria .

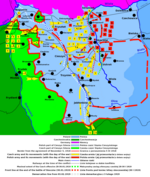

On November 5, 1918, the Polish National Council for the Duchy of Teschen (Rada Narodowa Kięstwa Cieszyńskiego, RNKC) and the Czech Territorial Committee (Zemský národní výbor, ZNV) agreed on a border drawing more or less along the ethnic border (the districts of Bielitz., Teschen Freistadt without Orlová to Poland, and Friedek with Orlová from the district of Freistadt to Czechoslovakia), regardless of the Germans and the Silesian regionalist Schlonsaken who were opposed to the Polish national movement , and took over the administration on behalf of their states. The Polish government was satisfied with the division and sought to recognize and consolidate the status quo (with fewer border changes), but the Czechoslovak government did not recognize this. On January 23, 1919, the Polish-Czechoslovak border war followed after the invasion of Czechoslovak troops. The military conflicts, which lasted until January 30, 1919, did not bring any decisive advantage to either state. During the Paris Peace Conference , both parties agreed on a diplomatic solution to the border conflict. However, the negotiations held between July 23 and July 30, 1919 in Krakow, Poland, remained unsuccessful, as the Czechoslovak side strictly rejected the referendum demanded by Poland only in the districts of Freistadt and Teschen, as the Czech population represented a minority and that for Poland problematic numerous Schlonsak and German society in the Bielitz district left out. The peace conference followed the proposal to hold the plebiscite in the entire area (see also referendums as a result of the Versailles Treaty ). At the same time, Poland was waging war with Soviet Russia in the east and was therefore more willing to compromise in the dispute with Czechoslovakia. In this situation, the Czechoslovak Foreign Minister Edvard Beneš achieved the partition along the Olsa River against the surrender of the disputed regions around Spiš and Arwa .

In July 1920, the former Duchy of Teschen was divided along the Olsa River by an arbitration decision by the victorious powers of the First World War. This gave Czechoslovakia the previously profitable industrial areas in the west, Poland received the old town of Cieszyn (German: Teschen) and Bielsko (German: Bielitz), which were incorporated into the Autonomous Voivodeship of Silesia . Through this demarcation, the former residence city of Teschen was divided, the suburb to the west of the Olsa came to Czechoslovakia and thus to today's Czech Republic . The Polish part after the division had an area of 1012 km 2 and 139,000 inhabitants, of which 61% were Poles [including Schlonsaken ], 31.1% German and 1.4% Czech. The Czechoslovak part comprised 295200 inhabitants in the area of 1270 km 2 , of which 48.6% [ethnic] Poles, 39.9% Czechs and 11.3 Germans. According to the last Austrian census, there were 123,000 Polish speakers, 32,000 Czech speakers and 22,000 German speakers in the area that was administered by the RNKC according to the treaty of November 5, 1918 and which was located in Czechoslovakia after the partition. In the first Czechoslovak population census in 1921, 67 thousand declared themselves Poles, only 1000 of them west of the historical linguistic border or the Galicians who immigrated to the places dominated by Czech municipal administrations. The conflict was officially resolved, but neither side was satisfied with the result. For Poland, because over 100,000 ethnic Poles remained on the Czechoslovak side, they were largely influenced by the Polish national movement, including the “Michejdaland” between Teschen and Jablunkau, the center of the Polish Lutherans. Poland had by no means given up its territorial claims for Polish- speaking strips near the border, called Zaolzie (without the Friedek district, which was not considered part of Zaolzie or the Olsa area). Czechoslovakia received the share of enormous economic and strategic importance, as it received the Bohumín – Košice railway line and thus one of the few efficient transport links (with the greatest capacity) that ran between the Czech and Slovak parts of the country at the time. But many Schlonsaks remained on the Polish side, who would have voted for Czechoslovakia in the plebiscite - at the Paris Peace Conference, the Czechoslovak diplomats stubbornly opted for the border on the Vistula, reached during the war, which would be a strategic depth to defend the railway line. For the Schlonsaken , the greatest disappointment was the partition itself. On February 9, 1919, the Silesian People's Party published an open letter , in which the indivisibility of Cieszyn Silesia as an independent republic under the protection of the League of Nations was the first and most important demand. From the beginning, their demands, partly with the support of the Germans, for the autonomy of the Teschener Land, best in Austria, Germany or in western European Czechoslovakia, least of all in underdeveloped Poland or the affiliation to a proposed Free State of Upper Silesia, were not taken into account. The developments in Upper Silesia canceled the chance of connection to Germany, which was particularly advocated in the Bielitzer Sprachinsel.

After the Munich Agreement of 1938, the beginning of the break-up of Czechoslovakia and the creation of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia , Polish troops occupied the Olsa area. At the beginning of the Second World War (1939-1945) and the occupation of Poland by the German Wehrmacht , in September 1939 this and the, since 1920, Polish area of Cieszyn Silesia as the district of Teschen and the district of Bielitz (Bielitz was expanded east to the Skawa ) in Greater Germany , while the Friedek district remained in the protectorate. In the policy of Germanization, the occupiers took advantage of the old Schlonsak movement, including in the German People's List , where the Silesian information in the third category (DVL III) was de facto included as a German nationality. After the end of the Second World War in May 1945, the former border conditions were restored and have not changed to this day.

Regional identity and culture

Before the First World War, four Slavic ethnic groups developed in the area: the Teschen Wallachians (around Teschen and Skotschau), the (Silesian) Gorals in the mountains, the Lachen (in the west and northwest) and the Jackets (in the town of Jablunkov ). The Austrian period is fondly remembered, the association with poverty, as in Galicia, is not widespread here. The division had a huge impact on the ramifications of identity and culture, and although many common traditions remained, today both parts have to be analyzed separately. To a certain extent, the Polish part came culturally closer to Upper Silesia, while the Olsa region on the Czech side formed its own demarcated country.

In the 1990s the debate about the independence of the proposed Silesian language began. In Upper Silesia there were many efforts to standardize the language, which also included the Teschen dialects. This movement is much weaker in Cieszyn Silesia, both on the Polish and the Czech side. Political views on Silesian affairs differ similarly; E.g. with the significantly lower share of votes for the Movement for the Autonomy of Silesia in regional elections in Poland (e.g. in 2014 ). The Silesian identity is often completely rejected by the Silesian Gorals in Poland, which is probably associated with the name Gorol , which is popular in Upper Silesia but often very pejorative for non-Silesians - in the Silesian Beskids , a popular destination for weekend trips from Upper Silesia on the other hand, in a neutral tone, the Gorals , who are very proud of their own culture that is widespread in the wider Beskids. On the Czech side, the Gorals often live without awareness of the relations in Polish Silesia and the Gorals awareness is not seen as conflicting with the Silesian identity, on the contrary - both reinforce each other.

The number of declarations of the Silesian and German nationality on both banks of the Olsa is low compared to Upper Silesia, but in no case does this mean that the locals do not call themselves Silesians, however, it is mostly not associated with a separate Silesian national identity. The enlightened Poles tend to follow the example of Paweł Stalmach (who himself said: Among Europeans I am a Pole, among Poles I am a Silesian, among Silesians I am a Czech ), or of Gustaw Morcinek ( I am a Silesian write about this country to bring Silesia Poland and Poland closer to Silesia ), while the political Shlonsak movement has almost died down today. For the modern Upper Silesian regional movements, on the other hand, the Silesian People's Party, founded in the Teschen region, and its leader Józef Kożdoń are iconic. In contrast to Upper Silesia, the local population is not divided into Silesians and non-Silesians ( Gorole around Katowice, Chadziaje around Opole), but a local would rather say I am from here (tu-stela) and the immigrants are not from here . This distinction increased during the period of social secularization and exceeded the religious boundary between Catholics and Lutherans. At the same time, the distinction between Pnioki (tree trunks - old residents ), Krzoki (shrubs, inhabited in the area for a long time) and Ptoki (wings, briefly or temporarily inhabited in the area) developed. The latter were given limited trust and even discriminated against. The Upper Silesians near the former Austrian-Prussian border call the Teschen Silesians Cesaroki (after Cesarz - Kaiser), the Teschen mock the Upper Silesians as Prusoki (Prussia) or like the rest of Poland as Hanysy (after the German personal name Hans , in Teschener Silesians historically in German the form Johann was used, Jano or Jónek in Teschener dialects). The Upper Silesians who settled in the Beskids (Ustroń, Brenna) were also named Lufciorze (after air , the quality of which is better than in the Upper Silesian industrial area ).

On the Czech side, the regional and national-Polish identity must also compete with the Czech and Moravian identity. The Czech state respects the Polish minority, although the bilingual place-name signs have often been vandalized. In recent decades, Czech linguists abandoned the classification of dialects in the Olsa area as Eastern Lachish , but more often they emphasize their mixed Polish-Czech character , suggesting that they belong to both languages at the same time, and unite all nationalities in the Olsa area.

The Polish-language song Płyniesz Olzo po dolinie (Olsa, you flow in the valley) by the poet Jan Kubisz from the late 19th century is considered the informal hymn of Cieszyn Silesia, especially of the Polish minority in the Olsa region.

Web links

- Cieszyn Silesia in the online lexicon on the culture and history of Germans in Eastern Europe, University of Oldenburg

- polen-pl.eu, Anna Flack: Teschener Schlesien - Where Polish, German, Czech and Jewish history is , 23 September 2013

- Beskydy and Cieszyn Silesia on the tourist website of the Silesian Voivodeship

- Cieszyn Silesia on the Moravian-Silesian region tourist website

- Association of the Germans of Teschner Silesia

- Michael Morys-Twarowski: The Relationship Between Religion Language and Nationality Using the Example of Village Mayors in Cieszyn Silesia in 1864–1918 , 2018 (English)

literature

- Grzegorz Wnętrzak: Stosunki polityczne i narodowościowe na pograniczu Śląska Cieszyńskiego i Galicji zachodniej w latach 1897–1920 [Political and national relations in the border area of Teschner Silesia and Western Galicia in the years 1897–1920] . Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek, Toruń 2014, ISBN 978-83-7780-882-5 (Polish).

- Grzegorz Chromik: History of the German-Slavic language contact in Teschener Silesia . Regensburg University Library , Regensburg 2018, ISBN 978-3-88246-398-9 ( online ).

- Idzi Panic: Śląsk Cieszyński w średniowieczu (do 1528) . Starostwo Powiatowe w Cieszynie, Cieszyn 2010, ISBN 978-83-926929-3-5 (Polish).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Teschener Schlesien in the online encyclopedia on the culture and history of Germans in Eastern Europe, University of Oldenburg

- ↑ a b c d Zbigniew Greń: Zależności między typami poczucia regionalnego i etnicznego , In: Śląsk Cieszyński. Dziedzictwo językowe . Warszawa: Towarzystwo Naukowe Warszawskie. Instytut Slawistyki Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 2000. ISBN 83-86619-09-0 .

- ^ Idzi Panic (editor): Śląsk Cieszyński w czasach prehistorycznych [Cieszyn Silesia in the prehistoric era] . Starostwo Powiatowe w Cieszynie, Cieszyn 2012, ISBN 978-83-926929-6-6 , p. 21 (Polish).

- ↑ G. Wnętrzak, 2014, p. 402

- ↑ Uniwersytet Śląski w Katowicach : Odkrycie najstarszych śladów obecności człowieka na terenie Polski ( pl ) October 21, 2010. Accessed October 26, 2010.

- ^ Idzi Panic (editor): Śląsk Cieszyński w czasach prehistorycznych [Cieszyn Silesia in the prehistoric era] . Starostwo Powiatowe w Cieszynie, Cieszyn 2012, ISBN 978-83-926929-6-6 , p. 171-198 (Polish).

- ↑ a b Jerzy Rajman: Pogranicze śląsko-małopolskie w średniowieczu [Silesian-Lesser Poland border region in the Middle Ages] . Wydawnictwo Naukowe Wyższej Szkoły Pedagogicznej, 1998, ISBN 83-8751333-4 , ISSN 0239-6025 , p. 37–38 (Polish, online [PDF]).

- ↑ Piotr Bogoń: Na przedpolu Bramy Morawskiej - obecność wpływów południowych na Górnym Śląsku i zachodnich krańcach Małopolski we wczesnym średniowieczu , Katowice, 2012, p. 41

- ^ Idzi Panic (editor): Śląsk Cieszyński w czasach prehistorycznych [Cieszyn Silesia in the prehistoric era] . Starostwo Powiatowe w Cieszynie, Cieszyn 2012, ISBN 978-83-926929-6-6 , p. 219-230 (Polish).

- ↑ P. Bogoń, 2012, p. 53.

- ↑ P. Bogoń, 2012, p. 54.

- ^ Idzi Panic: Jak my ongiś godali. Język mieszkańców Górnego Śląska od średniowiecze do połowy XIX wieku [The language of the inhabitants of Upper Silesia in the Middle Ages and in modern times] . Avalon, Cieszyn-Kraków 2015, ISBN 978-83-7730-168-5 , p. 45 (Polish).

- ^ Idzi Panic: Śląsk Cieszyński w średniowieczu (do 1528) . Starostwo Powiatowe w Cieszynie, Cieszyn 2010, ISBN 978-83-926929-3-5 , p. 75 (Polish).

- ↑ R. Fukala, Slezsko. Neznáma země Koruny česke. Knížecí a stavovské Slezsko do roku 1740 , České Budějovice 2007, pp. 24-25.

- ↑ Początki i rozwój miast Górnego Śląska. Studia interdyscyplinarne . Muzeum w Gliwicach, Gliwice 2004, ISBN 83-8985601-8 , Kształtowanie się pojęcia i terytorium Górnego Śląska w średniowieczu, p. 21 (Polish).

- Jump up ↑ Idzi Panic: Ziemia Cieszyńska w czasach piastowskich (X-XVII wiek), In: Śląsk Cieszyński: środowisko naturalne ... , 2001, p. 121.

- ↑ J. Spyra, 2012, p. 18

- ↑ Jaromír Bělič: Východolašská nářečí , 1949 (Czech)

- ↑ R. Mrózek, 1984, p. 306.

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, p. 51

- ↑ Idzi Panic: Śląsk Cieszyński w początkach czasów nowożytnych (1528-1653) [History of the Duchy of Teschen at the beginning of modern times (1528-1653)] . Starostwo Powiatowe w Cieszynie, Cieszyn 2011, ISBN 978-83-926929-1-1 , p. 181-196 (Polish).

- ^ E. Pałka: Śląski Kościół Ewangelicki Augsburskiego Wyznania na Zaolziu. Od polskiej organizacji religijnej do Kościoła czeskiego . Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego , 2007, ISSN 0239-6661 , p. 125-126 (Polish).

- ^ Michael Morys-Twarowski: Z dziejów kontrreformacji na Śląsku Cieszyńskim albo jak Suchankowie z Brzezówki w XVII i XVIII wieku wiarę zmieniali . In: Časopis Historica. Revue pro historii a příbuzné vědy . 2018, 2018, ISSN 1803-7550 , p. 84.

- ↑ Michael Morys-Twarowski: Śląsk Cieszyński - fałszywe pogranicze? [Cieszyn Silesia - wrong border area?] P. 78 (Polish, ceon.pl [PDF]).

- ↑ Słownik gwarowy, 2010, pp. 14–15

- ↑ J. Wantuła, Najstarszy chłopski bookplate polski , Kraków, 1956

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, p. 39.

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, p. 33

- ↑ Janusz Spyra: Śląsk Cieszyński w okresie 1653–1848 . Starostwo Powiatowe w Cieszynie, Cieszyn 2012, p. 361, ISBN 978-83-935147-1-7 (Polish).

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, p. 34

- ↑ Janusz Gruchała, Krzysztof Nowak: Śląsk Cieszyński od Wiosny Ludów do I wojny światowej (1848–1918) . Starostwo Powiatowe w Cieszynie, Cieszyn 2013, ISBN 978-83-935147-3-1 , p. 76 (Polish).

- ↑ Śląsk Cieszyński od Wiosny Ludów ..., 2013, p 53rd

- ↑ K. Nowak, Śląsk Cieszyński od Wiosny Ludów ..., 2013, p. 123

- ↑ Ludwig Patryn: The results of the census of December 31, 1910 in Silesia. Troppau 1912, p. 80 f.

- ↑ Kazimierz Piątkowski: Stosunki narodowościowe w Księstwie Cieszyńskiem ( Polish ). Macierz Szkolna Księstwa Cieszyńskiego, Cieszyn 1918, pp. 275, 292 [PDF: 143, 153].

- ↑ K. Nowak, Śląsk Cieszyński w latach 1918–1945, 2015, p. 19

- ↑ Janusz Józef Węc (ed.): Wpływ integracji europejskiej na przemiany kulturowe i rozwój społeczno-gospodarczy Euroregionu "Śląsk Cieszyński" . Księgarnia Akademicka, Kraków – Bielsko-Biała 2012, ISBN 978-83-7638-293-7 , p. 86 (Polish, Czech).

- ↑ G. Wnętrzak, 2014, p. 402.

- Jump up ↑ Marian Dembiniok: O Góralach, Wałachach, Lachach i Jackach na Śląsku Cieszyńskim / O goralech, Valaších, Laších a Jaccích na Těšínském Slezsku . Ed .: REGIO. 2010, ISBN 978-80-904230-4-6 , Górale śląscy / Slezští Goralé (Polish, Czech).

- ↑ Piotr Rybka: Gwarowa wymowa mieszkańców Górnego Śląska w ujęciu akustycznym . Uniwersytet Śląski w Katowicach . Wydział Filologiczny. Instytut Języka Polskiego, 2017, Śląszczyzna w badaniach lingwistycznych (Polish, online [PDF]).

- ↑ Zbigniew Greń: Identity at the Borders of Closely-Related Ethnic Groups in the Silesia Region , 2017, p. 102.

- ↑ Jadwiga Wronicz (u a..): Słownik gwarowy Śląska Cieszyńskiego. Wydanie drugie, poprawione i rozszerzone . Galeria "Na Gojach", Ustroń 2010, ISBN 978-83-60551-28-8 , p. 121 .

- ↑ Zbigniew Greń, 200. p. 121

- ↑ In 2002 only 1045 data in the Polish part of the region, less than 0.3%, see: Percentage of data on Silesian nationality in the census in 2002 ; In 2001 there were 9,753 entries in the Czech Moravian-Silesian region, but mostly in the former Prussian Hultschiner Ländchen , see Proportion of Silesian nationality in municipalities in 2001 , in the Olsa region the number is ten times lower than the Polish declarations

- ↑ a b Zdzisław Mach: Świadomość i tożsamość mieszkańców [Awareness and Identity of Inhabitants] (pp. 61–72) In: Janusz Józef Węc (Ed.): Wpływ integracji europejskiej na przemiany "kulturowe i rozwój społegionzno" . Księgarnia Akademicka, Kraków – Bielsko-Biała 2012, ISBN 978-83-7638-293-7 (Polish, Czech).

- ↑ Stela czy tu stela? Jak mówić?

- ↑ Hannan, 1996, pp. 85-86.

- ↑ A Czech site about the dialect

- ↑ January Kajfosz: Magic in the Social Construction of the Past: the Case of Cieszyn Silesia , p 357, 2013;

- ↑ Jiří Nekvapil, Marián Sloboda, Petr Wagner: Multilingualism in the Czech Republic (PDF), Nakladatelství Lidové Noviny, pp. 94–95.