Polish-Soviet War

| date | 1919 to 1921 |

|---|---|

| place | Central and Eastern Europe |

| output | Victory of Poland |

| Peace treaty | Treaty of Riga |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

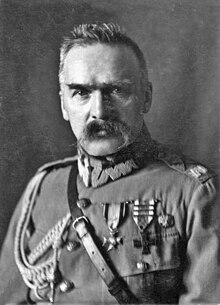

| Commander | |

|

|

|

In the Polish-Soviet War 1919-1921 ( Russian Советско-польская война / Transcription: Sowetsko-polskaja Voina , Polish Wojna polsko-bolszewicka , Ukrainian Польсько-радянська війна Polsko-radjanska wijna ) tried the one hand, the reconstructed Poland , in the east of the historic Restore the border line from 1772 and create an Eastern European confederation (→ Międzymorze ) under Polish leadership. On the other hand, Soviet Russia , which was still in the middle of a civil war , endeavored to expand its sphere of influence to the West. In Ukraine , Poland was supported by nationalist forces previously driven from power by the Bolsheviks .

The initial successes of the Polish troops under Marshal Piłsudski and the foreign military units supporting them, which were able to occupy large stretches of Ukraine, including Kiev , were destroyed after some time by the Soviet Red Army : It threw the Polish army so far back into the interior of Poland that an occupation of Poland threatened. At the Battle of Warsaw , the Polish army turned the tide again. In the subsequent campaigns, the Soviet army was thrown back as far as Ukraine. In addition, in the Polish-Lithuanian War in October 1920, the area around the Lithuanian capital Vilnius (Polish Wilno) was conquered.

In the Treaty of Riga , which was signed on March 18, 1921, Soviet Russia, Soviet Ukraine and the Republic of Poland agreed to accept the armistice of the previous year and the border between the Soviet Union and the re-established Polish state as well as a. the performance of compensation payments. The Polish-Soviet border now ran up to 250 km east of the line that a commission had proposed in 1919 as the eastern border of the re-established Poland (" Curzon Line "). The agreement was the second contractual "territorial amputation" of ethnically non-Russian territory, which the Russian Empire had previously regarded as an integral part of its own territory after the October Revolution .

causes

Russia, which left the First World War as a result of the October Revolution , did not take part in the Paris negotiations on the post-war order, which is why a border settlement between the newly founded Republic of Poland and the Soviet Russia, which was now led by the communist Bolsheviks , was not made.

The Bolshevik Russia, which was in civil war , endeavored to shift its sphere of influence to the West and trigger a proletarian revolution in Germany.

Poland, in turn, tried to maintain its regained independence and to strengthen its own position of power on its eastern flank. There was no consensus in Polish politics about the desired border with Soviet Russia. Marshal Piłsudski , who commanded the Polish armed forces, strove for a sphere of influence extending as far east as possible in the form of an Eastern European confederation under Polish leadership. The course of the eastern border between Poland and Lithuania on the eve of the partitions of Poland (1772) served as a reference .

A complete independence of Ukraine and Belarus , which was partly sought by them, was excluded according to both Polish and Russian war aims. In Ukraine, however, Poland was supported by national forces that had previously been ousted by the Bolsheviks.

The exact time of the beginning and the trigger of the war is unclear and controversial. Some authors describe the Polish attack on Kiev (April 1920) as the beginning of the war. Others settle the start of the war in 1919. As the war was preceded by a simmering border conflict, both views are justified. It is also controversial whether the end of the war should be dated to the armistice on October 18, 1920 or to the Treaty of Riga on March 18, 1921.

The Polish-Ukrainian alliance of April 1920 after the Polish-Ukrainian War shifted the weight of those involved during the course of the war.

Terms and definitions

The war itself has several names, of which "Polish-Soviet War" is the most common. The attribute "Soviet" does not refer to the Soviet Union , which was founded in December 1922 , but to the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic, which has existed since 1917 . There is also talk of the “Polish-Russian” or “Russian-Polish war”. However, this is not clear, as there have been numerous wars and minor armed conflicts between Poland and Russia. Polish sources usually speak of the “Polish-Bolshevik War” (wojna polsko-bolszewicka) or the “Bolshevik War” (wojna bolszewicka) . There is also the term "War of 1920" (Polish Wojna 1920 roku ).

The official history of the Soviet Union saw the war as part of the foreign interventions during the Russian Civil War between the bourgeois "whites" and the Bolshevik "reds" that had been going on since the revolution. The attempt by non-communist Poland to achieve or maintain independence from (Soviet) Russia was seen as partisanship for the “white” side and as an attempt to block the spread of the proletarian revolution to the west. It came to the fore that the Polish minority in the border areas mostly belonged to the wealthy landed nobility or the bourgeoisie. This is why the war is also referred to in Soviet sources as the "War against White Poland". In the People's Republic of Poland , official historiography also followed this line. The war was largely excluded from the official historical picture and, if at all, presented as armed action by bourgeois circles that did not act in the interest and with the support of the Polish people.

Starting position

The First World War fundamentally changed the political map of Eastern Central Europe and Eastern Europe. The collapse of the Russian Empire in the course of the defeat in the October Revolution and the fall of Austria-Hungary left room for new nation states . In addition to Finland , Estonia , Latvia , Lithuania and Czechoslovakia , Poland also successfully took the step towards statehood. After the partitions of Poland in 1772, 1793 and 1795, a Polish state initially ceased to exist. However, a number of other ethnic groups (Belarusians, Ukrainians, Kashubians, Germans etc.) lived in the areas that had belonged to Poland until 1772 . The Poles had always retained their cultural independence, but the problem of Poland's borders came to the fore with the new or resurgent nation-states. This had already manifested itself during the world war. The German Reich tried to take advantage of these tendencies by establishing a pro forma independent Kingdom of Poland . After the armistice on the Western Front, Poland declared itself independent on November 11, 1918. Under pressure from the Entente powers , among other things, Poland's status as an independent nation-state from Austria in 1918 and by the Weimar Republic in 1919 was recognized in the Paris suburb treaties . With the Curzon Line , the western allies established a provisional borderline, which avoided placing a number of non-Polish ethnic groups under Polish rule, but in turn excluded many Poles from their nation-state. Poland itself found itself in an economic crisis due to the effects of the First World War. It received help from an American relief mission under Herbert Hoover . The re-establishment of the Polish state was not completed by the end of the war. Although there was z. B. already a new stable currency, but the new administration had not yet prevailed everywhere. The military would prove to be the most powerful political instrument of the Polish state in the years to come.

The Bolsheviks viewed Poland as a state controlled by the Entente and saw in it the bridge to Europe on which the revolution should be carried to the west. Overall, the prevailing opinion in Russia was that the newly independent states of East Central and Eastern Europe were rebellious Russian provinces, so that the opponents of the Bolsheviks in the civil war, the White Guards , Poland and the other states in this region, denied sovereignty and after a restoration of Russia aspired within the borders of the tsarist empire . Russia was in civil war at the time. The White Armies tried to oust the Bolsheviks from their position of power and to restore the multi-ethnic Russian dominated state. The country itself was plagued by economic decline and supply problems. The losses among the population through fighting and disease are estimated at up to eight million.

War aims

The main motive of the Polish leadership, above all the head of state Józef Piłsudski , was to achieve the strongest possible position vis-à-vis those states that were involved in the Polish partitions more than a hundred years earlier - i.e. Russia, Prussia and Austria. This not only led to clashes with Russia, but also, for example, in the voting areas of Silesia, where German Freikorps and Polish nationalists faced each other at times (until 1921). The Polish leadership saw the greatest leeway in the east. A possible resurgence in Russia, this time under communist leadership, was countered by Piłsudski with the idea of a confederation dominated by Poland in Central and Eastern Europe. The Polish-Lithuanian Real Union , which existed until 1791, served as a historical model for the Polish-run “inter- sea country ” (Polish: Międzymorze ) . The confederation should include Poland, Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania. The Polish military historian Edmund Charaszkiewicz called this policy Prometheism in 1940, referring to a movement from nineteenth-century Russia . Influential Polish politicians like Roman Dmowski opposed this policy because they wanted an enlarged Polish nation-state, but Piłsudski was able to prevail.

Political thoughts on the Soviet side were largely shaped by Marxism . According to this theory, the revolution would break out first in the industrialized countries of Europe. However, it was the first to appear in Russia . Lenin concluded from this that the world revolution would spill over from Russia to Europe, and he believed that Russia, as the only socialist state, could not exist. Thus he saw the export of the revolution not only as an option, but also as a necessity of his policy. The existing instability in Germany encouraged this view. Up until 1920, the young German republic had seen three attempted coups from the right, four general strikes and five heads of government. Furthermore, the empire was put under further pressure by separatist efforts, encouraged by the harsh conditions of the Versailles Treaty . Civil war-like conflicts in 1919, which were put down by the deployment of voluntary corps, strengthened the Bolsheviks in their belief in an impending revolutionary upheaval in other parts of Europe as well. Attempts to send aid to the German communists in 1918 had failed, but some communists hoped that an advance of the Red Army would strengthen their position within Germany. Through the experience of the civil war, the communist party learned to implement its political goals through military methods. This should become a leitmotif of Russian action in escalating the war with Poland.

In general, the Soviet leadership saw itself isolated and surrounded by enemies in the civil war, first through intervention by the Central Powers, then through the intervention of the Entente. Her military action against the struggle for independence in the Baltic states and the Ukraine had also brought her into violent border conflicts with all neighboring western states. When the war between Russia and Poland finally broke out, the Russian leadership presented it as an ideological dispute: “In the West, the fate of the world revolution will be decided. The road to the world fire runs over the corpse of White Poland. On bayonets we will bring peace and happiness to working mankind. ”This is the slogan that the Revolutionary Military Council of Soviet Russia issued in a proclamation to soldiers of the Red Army in July 1920 .

Course 1918

After the conflict began in 1918, the Poles achieved great success and occupied large areas of Ukraine, including Kiev .

When the German soldiers under the leadership of Max Hoffmann began to retreat westward from Central and Eastern Europe in 1918, Lenin ordered the Western Red Army to advance west. The main aim of this operation was to move through Central and Eastern Europe, to install Soviet governments in the independent states and to support the communist revolutions in Germany and Austria-Hungary .

Poland fought against Czechoslovakia for Teschen , against Germany for Posen (→ Wielkopolska Uprising ) and against Ukraine for Galicia (→ Polish-Ukrainian War ).

Since the end of the occupation at the end of the war in 1918, border conflicts developed between many independent states in Central and Eastern Europe: Romania fought against Hungary for Transylvania , Yugoslavia against Italy for Rijeka ; Ukrainians , Belarusians , Lithuanians , Estonians and Latvians fought each other and / or the Russians. Winston Churchill snapped: "The war of the giants is over, the quarrel of the pygmies has begun."

Course 1919

From March 1919 onwards, Polish intelligence sources reported Soviet plans for an offensive. The Polish High Command therefore considered a preventive offensive. The plan for Operation Kiev was to destroy the Red Army on Poland's right flank. The political goal of the offensive was the establishment of a pro-Polish government under Symon Petljura in Kiev.

In February 1919 there was the first meeting of Polish troops and advance units of the Red Army . In Bjarosa , Belarus, a gun battle developed between the two parties. However, the clash represented an unplanned company- strength action on both sides. Both sides had previously taken action against the Ukrainian nationalists under Petlyura.

In March the Red Army began a successful offensive on Vilnius and Grodno , formally part of Lithuania, but ethnically mostly Polish at the time. At the same time, the Poles attacked along the Memel and took the small towns of Pinsk and Lida in Belarus. Soldiers of Polish origin fought both on the side of the German emperor and on the side of the Russian tsar during the last World War. They were also supported by a mission from French officers in the training of their troops. While the Soviet propaganda made fun of the "bourgeois" character of the Polish armed forces , the top of the military expressed themselves very differently in a small circle. "For the first time a regular army, led by good technicians, is operating against us," Trotsky warned the party's Central Committee. This superiority enabled the Polish army to compensate for the disparity in numbers. In 1919 it had 230,000 soldiers on its eastern border, while the Red Army comprised a total of 2,300,000 soldiers, many of whom, however, were tied up in the civil war in their own country. The situation of the young Soviet power, which was tied up in a multi-front war and also suffered from famine and revolts, was difficult.

A Polish advance drove the Bolsheviks out of Vilnius on April 19. Politically, this meant enormous gain for the Poles, as it meant that the capital of the Belarusian-Lithuanian republic installed by Soviet Russia fell into Polish hands. The advance to the east continued. On August 28, the Poles put the first tank in order Babrujsk to conquer. With that they had already penetrated deep into Belarus . In October Polish troops held a front from Daugavpils in southern Latvia to Desna in northern Ukraine .

The Soviet leadership found itself in a difficult situation during 1919 and was unable to respond appropriately to the advance of the Poles. The communist state was threatened by the offensives of three White armies under Denikin in southern Russia, Kolchak in Siberia and Yudenich in the Baltic States. Lenin succeeded in appeasing the Polish government by promising great territorial concessions that would have brought almost all of Belarus into Polish hands. Piłsudski himself had other reasons for not continuing his offensive: The White Movement advocated the goal of a united, undivided Russia, which also included the new nation states of Central and Eastern Europe. The Polish head of state therefore waited with the intention that both parties to the civil war would weaken each other further.

Course of 1920

By the beginning of 1920, the Soviet troops had destroyed the bulk of the White Armies in the civil war .

Only a force of around 20,000 men under Wrangel had withdrawn to the Crimean peninsula , far from the Russian heartland. The leadership in Moscow also succeeded in relieving itself militarily through peace treaties with Estonia and Lithuania. In January 1920, the Red Army was regrouped. It was planned to assemble an army of 700,000 men along the Berezina to launch an offensive against the Polish troops at the end of April. At that time the Red Army already had a nominal strength of five million men. But this superiority was deceptive. The troops were poorly trained and in some cases insufficiently armed. The civil war had already shown that Red Army units often had no chance against outnumbered white troops. Although the Red Army had captured some of the German army's arsenal and some French tanks from the whites, this had little effect on the overall armament of the armed forces. In one point, however, the Russians had an advantage due to the civil war: They had already recognized in the fight against the Cossacks in 1919 that the cavalry was a decisive factor in the fight between low-tech armies in the vastness of Russia .

Preparation in Poland

The Polish army took a different route in terms of military technology. Most officers had drawn the conclusion from the experience of the First World War that the cavalry did not justify the material expenditure required to maintain it. Nevertheless, the build-up of the army proceeded quickly. At the beginning of 1920 it already numbered around 500,000 soldiers. Most had served in the World War. But there were also inexperienced volunteers, including 20,000 Poles from the United States , who had joined the force. One problem was that the troops were armed from different countries. Thus the logistics of the troops had to take into account different types of ammunition and spare parts standards for the supply. Overall, the Polish troops were better equipped materially than the Red Army because they were armed with numerous Entente weapons, including modern artillery and machine guns. On July 20, 1920, the German government imposed an embargo on arms deliveries and declared Germany neutral in the armed conflict.

Polish offensive

The first notable offensive operation of the year was the conquest of Daugavpils on January 21, 1920. The 1st and 3rd Divisions of the Polish Division under Edward Rydz-Śmigły conquered the city in fierce two-week battles against the Red Army. The city itself was of minor strategic importance. However, the Latvian government had requested the help of the Polish armed forces to incorporate the majority Latvian city into its new nation-state. After the conquest by Polish troops, the city was also handed over to the allied state. Thus the operation represented a gain in political prestige for Poland. In March 1920, the Polish armies made two simultaneous, successful advances in Belarus and Ukraine. This considerably reduced the Red Army's ability to carry out its planned offensive.

On April 24, the Polish armed forces finally began their main offensive with the aim of Kiev . They were supported in this by the troops of the Ukrainian nationalists under Petlyura, with whom a secret agreement and a military convention had previously been concluded. The Polish 3rd Army under Rydz-Śmigły led the main thrust on the Ukrainian capital from the west. On its southern flank, the 6th Army under Wacław Iwaszkiewicz-Rudoszański advanced into the Ukraine. To the north of the main thrust, the 2nd Army under Antoni Listowski carried out another offensive.

Kiev was captured on May 7th, but the company's real military objectives were missed. The Red 12th and Red 14th Armies quickly withdrew after a few skirmishes on the border. The Polish armed forces had not succeeded in locking in and seriously decimating their opponent's troops. This would have been irrelevant if the political aim of the offensive had been achieved. Piłsudski hoped for strong support from the Ukrainian nationalists, because he knew that the Polish army alone could neither occupy the large country nor effectively defend it against the Red Army. A political campaign in Ukraine was designed to appeal to Ukrainian patriotism for support for Petlyura's armed forces. Ukraine had been a theater of war since 1917, the population was tired of the fighting, and Petlyura had already failed in the fight against the Red Army. As a result, the response to recruiting efforts has remained poor. The Ukrainian nationalists could only field two divisions and were therefore of little help.

Piłsudski's advance on Kiev was a Pyrrhic victory in every respect . From a military point of view, the Polish troops were in a very exposed position, far from their supply bases in central Poland. The red troops had remained intact due to their early withdrawal and were able to regroup for a counter-offensive. Politically, the operation was a complete failure. Not only was there a lack of support from the Ukrainians, but on the international stage Soviet Russia was able to portray Poland as an aggressor. As a result, the Entente , especially France , showed less willingness to support Poland materially.

On May 30, 1920, the former general Alexei Brusilov , a well-known veteran of the First World War, published in Pravda the call “To all former officers, wherever they are”, in which he encouraged them to forget old insults and to face the Join Red Army. Brusilov saw it as the patriotic duty of a Russian officer to assist the Bolshevik government, which he believed was defending Russia. Lenin also discovered the utility of Russian patriotism. A call by the Central Committee was directed at the “honored citizens of Russia” to defend the Soviet republic against Polish arrogance.

Soviet counter-offensive

The Red Army had already grouped its troops for an offensive in the Ukrainian border areas at the beginning of the year. Around Kiev, the Southwest Army Group was under Egorov . Its front included the 12th and 14th Red Armies. In addition, the 1st Cavalry Corps of the 1st Red Cavalry Army under Budjonny was assigned as an offensive capacity. In Belarus the Bolsheviks had set up the Western Army Group. It was under the orders of Tukhachevsky . It comprised the 3rd, 4th, 15th and 16th Armies. They also had a mounted offensive formation with the 3rd Cavalry Corps.

The counteroffensive showed that Jegorov's decision to withdraw and let the Polish armies run into the void, so to speak, was the right one. On May 15, he launched his counter-offensive. He had his 12th Army advance north and his 15th Army south of Kiev. His attack was supported by the 1st Cavalry Corps south of Kiev. The Poles did not have the strength to adequately defend both sides at the same time. They also lacked the cavalry, which they had not taken into account when building their army. On June 12th, Kiev changed hands again. The Polish troops, however, managed to withdraw despite the Soviet pincer movement and in turn escaped annihilation.

The Red Army's Western Army Group did not remain idle. It began its advance on May 14th. However, this attack failed. A resumption of the attacks after reinforcements on July 4th brought the desired success. On July 11, Tukhachevsky's soldiers captured Minsk. The Polish forces withdrew before the advancing Red Army forces, but their defensive strategy proved to be a disadvantage. Analogous to the western front in World War I, the Poles tried to create a continuous line of defense using buried infantry. The front against Tukhachevsky, however, was 300 km wide. The Poles had 120,000 soldiers and 460 guns at their disposal. A coordinated position system would have required more soldiers, more artillery and, above all, strategic reserves that could be deployed at critical points. Thus, the Reds could use the strength of their cavalry, which proved to be a successful offensive weapon against an overstretched enemy front. Due to the lack of mounted units in the Polish army, any counter-attacks were doomed to failure, as they could not be carried out at the necessary speed.

Tukhachevski's front moved an average of 30 kilometers a day towards the Polish heartland in July. Vilnius fell on July 14, and Grodno a few days later. Finally, on August 1, the Red Army captured Brest-Litovsk . This left the red troops only 100 kilometers east of the Polish capital Warsaw .

Meanwhile, in the south, Yegorov's western army group had been no less successful. His troops had pushed the Poles out of Ukraine and were advancing towards southern Poland. In June they began the siege of the industrial center of Lviv in eastern Galicia. The rest of his front turned northwest to assist Tukhachevsky in attacking Warsaw.

Battle of the Vistula

Soon the Red Army threw the Polish troops back into the Polish heartland, so a defeat and occupation of Poland was expected. On August 10th, the Soviet III. Cavalry corps under Gaik Bschischkjan the Vistula north of Warsaw . According to the offensive plan , this movement was supposed to cut off Warsaw from Gdansk , the only open port for the shipment of arms and supplies. Meanwhile, the Soviet commander let his 16th and 3rd Army infantry in the center exert pressure on the capital. Tukhachevsky firmly believed that his offensive plan would have sealed the fate of the capital with the cavalry breaking into the left flank of the Poles.

However, the Soviet offensive plan turned out to be flawed. The reasons for this can be found, among other things, in the experience of the civil war. In the internal Russian fighting, the Red Army faced rebels, whose strength decreased as they withdrew. The further the enemy White Armies were pushed away from their destination, the capital Moscow, the more the internal cohesion of their troops crumbled. The Polish army, on the other hand, grew stronger as it withdrew. This shortened their supply routes and communication lines. Furthermore, the defense of the own capital ensured a strengthening of the morale of the troops. Tukhachevsky expected to take action against a demoralized opponent. However, he encountered a well-organized and highly motivated army. According to the Italian military attaché in Warsaw, Curzio Malaparte , the Soviet leadership also assumed wrong political and organizational assumptions because they had hoped that an uprising by the proletariat and the Jewish minority would help them in besieged Warsaw .

An even more serious mistake is to be found in the highest command of the Soviet army. While Tukhachevsky was advancing on Warsaw with his northwestern front, the southwestern front under Jegorow was ordered to attack Lwów. If both fronts had been concentrated on the Polish capital, the Russians would have had twice the strength, including an additional cavalry corps. Tukhachevsky's southern flank was completely exposed because he had to cover it under his own steam and had no contact with the south-western front. Some historians hold Joseph Stalin responsible for these decisions , who as Political Commissar of the Southwest Front had great influence on their goals.

The Polish counterattack began just four days after the Soviet cavalry passed. Piłsudski had planned a pincer movement. On August 14th, the Polish 5th Army under Władysław Sikorski attacked north of Warsaw. Opposite her were Gais III. Cavalry Corps and the 3rd and 15th Armies of the Red Army. Despite this numerical inferiority, the Poles managed to repel the Russian advance, and after a few days they themselves took the offensive. On August 16, the Polish 4th Army under Piłsudski itself launched an attack south of Warsaw. The troops had been hastily reinforced with volunteers during the Soviet advance. The pincer movement proved successful when Piłsudski's forces rolled into the rear of the Russians two days later. Tukhachevsky ordered his soldiers to withdraw on the same day, but it was too late for the key units. With the III. Cavalry Corps, the Northwest Front lost its greatest offensive force and numerous infantry divisions remained in the pocket.

This battle went down in Polish history as a miracle on the Vistula . This term was, however, coined by the political opponents of Piłsudski, who wanted to deny him the merit in defending the capital. Piłsudski described the battle as a kind of " brawl " ( Polish: bijatyka ). His strategy , according to him, was entirely dictated by circumstances. He suspected the main forces of the Bolsheviks to be at his sector of the front. However, these faced Sikorski's 5th Army in the north. However, Sikorski was able to prevail against them without major difficulties. When Piłsudski let his 4th Army advance, they encountered much weaker resistance than expected and Piłsudski personally visited the front line, since he could not believe it was only against weak forces. This strategic miscalculation brought him a decisive advantage, as he could now advance with his strongest army to the lines of retreat of the Red Army with practically no resistance.

Second Polish offensive

The battle for Warsaw was a turning point in the war, but it did not make the final decision. In the West it was believed that the communist state could mobilize its reserves in order to formally overrun the Poles even after the defeat of Warsaw. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George said: "If Russia wants to crush Poland, it can do so whenever it pleases." The Soviet Southwest Army Group had withdrawn from Lwów / Lemberg . But it was still on Polish territory and, thanks to the cavalry army under Budjonny, was still a serious offensive force. On August 25, 1920, she began to march westward again in two columns from the upper reaches of the Bug . The Polish armed forces were prepared for this maneuver. General Sikorski divided his 3rd Army into two groups, advancing north and south of the Red Army's advancing cavalry army. It is noteworthy that both Polish wedges were equipped with a cavalry brigade and a cavalry division, respectively. So the Poles had quickly learned of the Soviet tactics of mounted advances. On August 30, 1920, they succeeded in enclosing the Soviet cavalry army. The Bolshevik troops were trapped in a hose just 20 km. Although they managed to break out three days later, the army, robbed of its initiative by the narrow siege ring, suffered great losses. This included Budjonny's command staff, which was destroyed by Polish artillery when the Soviet commander was not present. After its outbreak, the cavalry army could no longer consolidate and withdrew to Zhytomyr in what is now Ukraine.

Furthermore, this conflict resulted in one of the last pure cavalry battles in Europe. After this battle, in which Polish horsemen prevented their Soviet opponents from breaking out, this operation went down in Polish military history as the Battle of Komarów. Furthermore, there is talk of the Battle of Zamość , which better reflects the overall scope of the fighting.

In addition to the cavalry army, the Western Army Group also remained on Polish soil. They had been defeated near Warsaw, but Tukhachevsky was able to build a line of defense on the Memel . Here, in the hope of a new offensive against Warsaw, his troops were refreshed. At the beginning of September he had 113,000 combat-ready soldiers under his command; this number was only slightly below his troop strength on the Vistula.

Piłsudski assembled the 4th and 2nd Polish Armies to defeat his opponent again. The Polish plan for the Battle of the Memel on September 20, 1920 was simple but successful. Piłsudski deployed his troops while the Red Army was still in the process of restoring its strength. While attacking the enemy center with his infantry, his cavalry succeeded in outflanking the Russians on their flanks. Tukhachevsky had to withdraw a week after the start of the battle to avoid being encircled by the Polish troops.

The success of the two battles did not destroy the Soviet armies, but they were disorganized and severely decimated. The Polish army now advanced east at the same speed as the Russians had advanced towards Warsaw that summer. On October 18, Polish troops advanced into the Belarusian capital Minsk .

Before that, the Polish leadership had brought the area around Vilnius (Polish: Wilno) under their control in a brief Polish-Lithuanian war . The Lithuanian capital was returned to Lithuania by Soviet Russia as a result of the Lithuanian-Soviet War with a peace treaty of July 12, 1920 and was internationally recognized as Lithuanian, in particular by the Treaty of Suwałki of October 7. Piłsudski nevertheless brought his hometown under his control with a trick: The commander of the 1st Lithuanian-Belarusian Division of the Polish Army, Lucjan Żeligowski , allegedly mutinied spontaneously on October 12th along with his entire unit. Then, after a brief border battle, he marched into the city. He proclaimed a republic of Central Lithuania . This rather fictional structure was then attached to Poland after a plebiscite in 1922.

Politics and diplomacy

Poland had few allies among European states that were not directly involved.

Hungary offered a corps of 30,000 cavalrymen, but the Czechoslovak government did not allow the transit, so only a few trains with arms deliveries arrived in Poland.

Relations between Poland and Lithuania deteriorated during the war. The Baltic state insisted on its political independence within the framework of the peoples' right to self-determination, which contradicted the plans of a Polish-dominated federation. Furthermore, Poland pushed for the incorporation of the predominantly Polish-settled south-east Lithuania, including the historic Lithuanian capital Vilnius . Polish efforts to integrate with Latvia were more successful. The provisional government there united with Poland against Russia and carried out joint military operations in early 1920.

France, which pursued a policy of pushing back communism, sent a group of 400 men to Poland in 1919. It consisted mainly of French officers, but there were also some British officers led by Lieutenant General Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart . The French efforts were aimed at improving the organization and logistics of the Polish army. Among the French officers was the future French President Charles de Gaulle , who was awarded the highest Polish military order, the Virtuti Militari , during the war .

In addition, France sent the so-called Blue Army to Poland: a force that consisted mainly of Polish-born volunteers and a few international volunteers and that had fought under French command during the First World War. It was led by the Polish general Józef Haller .

- Soviet anti-Polish propaganda posters

Diplomatic efforts 1919

In 1919 several attempts at peace negotiations were made between Poland and Soviet Russia. But they failed because both sides still promised military gains and were therefore not prepared to make any real concessions.

Diplomatic efforts 1920

The Polish government made intensive use of the relative calm that ensued after the first fighting to gain a foothold in Ukraine through diplomacy. A major success was the agreement with the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petljura, whom the Poles had fought shortly before. Petlyura had fled Ukraine to Poland with his remaining troops before the pressure of the Bolsheviks . Petlyura accepted Poland's territorial gains at the expense of Ukraine and agreed to a generous border settlement. In return, the Polish side promised military aid and the re-establishment of Petlyura's regime in the event of success against Soviet Russia. This was a big step in the direction of the Polish confederation plans; in the event of a military victory, Ukraine would serve as a buffer state against Russia, allied with Poland. Petlyura seized the last chance to restore the statehood of Ukraine. Both politicians received severe criticism in their own camps. Piłsudski was attacked by Dmowski's National Democrats, who completely opposed Ukraine's independence. The rapprochement with Poland was largely unpopular among the Ukrainian population. The Polish army was still at war with the Ukrainian nationalists in 1919. The Ukrainians in Galicia , whose state was incorporated into Poland after the military occupation, saw the agreement as a downright betrayal of their interests. In mid-1920 there was even a split in the Ukrainian national movement. Petlyura's soldiers remained loyal to Poland, while the Galician Ukrainians switched to the side of the Red Army.

When the tide turned against Poland, Piłsudski's political influence began to wane, while his opponents, including Roman Dmowski, grew in influence. However, Piłsudski managed to regain his influence, especially through the military, at the last moment - when the Soviet troops were already outside Warsaw, the political leadership panicked and the government under Leopold Skulski resigned at the beginning of July.

Meanwhile, the self-confidence of the Soviet leadership grew. The beginning of the Soviet advance and the expansion of the Bolshevik Revolution to all of Europe became apparent. On the orders of the Communist Party of Russia (KPR (B)), a Polish puppet government was installed in Białystok on July 28 , the " Provisional Polish Revolutionary Committee " ( Polish: Tymczasowy Komitet Rewolucyjny Polski (TKRP) ). It was supposed to take over the administration of the Polish territories conquered by the Red Army. This communist group had almost no support from the Polish population.

In July 1920, Britain announced that it would send large quantities of surplus military material from World War I to Poland for support. But an impending general strike by the Trades Union Congress , which objected to the support of the Poles by Great Britain, meant that this project was never realized. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George had never been convinced of the support of the Poles themselves, but was urged to do so by the right wing of his cabinet, especially Lord Curzon and Winston Churchill . On July 11, 1920, Great Britain presented Soviet Russia with an ultimatum calling for an end to hostilities against Poland and the Russian Army (the White Army in Southern Russia with Pyotr Wrangel as Commander-in-Chief) and the recognition of the Curzon Line as a temporary border to Poland as long as a permanent demarcation cannot be negotiated. In the event of the Soviet refusal, Great Britain threatened to support Poland by all possible means (in fact these means were rather limited due to the political situation in Great Britain). On July 17th, Soviet Russia rejected the British demands and in turn made a counter offer to negotiate a peace treaty directly with Poland. The British responded by threatening to end ongoing talks on a trade deal if Soviet Russia continued the offensive against Poland. This threat was ignored. The looming general strike came in handy as an excuse for Lloyd George to withdraw from his promises. On August 6, 1920, the Labor Party announced that British workers would never participate in the war as Poland's allies and urged Poland to accept a peace based on Soviet terms.

Poland suffered further setbacks due to sabotage of arms shipments as workers in Austria, Czechoslovakia and Germany prevented transports from passing through.

Also, Lithuania was set predominantly anti-Polish and overturned in July 1919 the Soviet side. The Lithuanian decision was supported on the one hand by the desire to incorporate the city of Vilnius and the neighboring areas into the Lithuanian state, and on the other hand by the pressure that the Soviet side exerted on Lithuania, not least through the stationing of large units of the Red Army near the Lithuanian border.

Treaty of Riga

After the victories of the Polish army in the campaigns after the Battle of Warsaw, negotiations began to end the state of war. They were concluded on March 18, 1921 with the Riga Peace Treaty .

consequences of war

The young Polish republic was able to expand its national territory considerably. With the increase in Lithuanian territory (Vilnius area, 1921), the goal of restoring the borders of 1772 came closer. Relations with Lithuania, on the other hand, sank to a low point, and Lithuanian historiography and collective consciousness have not got over this trauma to this day. Internally, the war strengthened Marshal Piłsudski's popular position as the “father of independence”. However, he was unable to solve the economic problems of his country in the following years and turned away from politics in 1922. Likewise, the dominant position of the military in the young nation-state was established by the war. Piłsudski used this to bring himself back to power during the May coup in 1926. In doing so, he excluded many of his former comrades in the military who did not want to support his coup. Until 1935, the marshal was the most influential figure in politics, usually without a political office, in the state's regiment. Since Poland was territorially saturated with the enormous profits from the war against Russia, he based his regime on the Sanacja ideology (German: "recovery"). Its aim was the moral and economic recovery of the state under authoritarian leadership. This led to the rigid suppression of political opponents and national minorities, such as the Ukrainians and Belarusians , who had just been incorporated into the Polish state through the annexations of the war. Their national identity was poorly developed at the time of the war, because the majority of the population defined themselves more through religious or regional identities . The polonization efforts of the later Polish government nevertheless met with strong resistance.

In terms of foreign policy, the war also had far-reaching consequences for Poland. Relations with the British government under David Lloyd George were disturbed, with the British side itself split. A group under Winston Churchill wanted to support Poland, while the head of government himself opposed it, as Piłsudski had given him too little attention to the interests of the Entente. Even during the war, Polish complaints about the lack of support from their allies grew. The Polish Prime Minister Ignacy Jan Paderewski wrote accusingly to the British government in October 1919: “The promises made by Mr. Lloyd George to support our army on June 27th did not materialize.” The Poles were also disappointed in France because they were more concerned had promised material help. As a result, the head of the French military mission, Maxime Weygand , was excluded from the decisions and literally brought before him because he did not speak the Polish language. This did not stop the French government from celebrating him as a hero on his return, which allowed them to gain domestic prestige under Alexandre Millerand . As a result, Polish-French relations were normalized a year later with a state visit by Piłsudski. The war cemented an insurmountable opposition to the Soviet Union. This promoted an idea of revenge within the political leadership. In the secret additional protocol of the German-Soviet non-aggression pact of August 23, 1939 , Stalin, who was also involved in the Polish-Soviet war, secured the territories that had been handed over to the Poles in 1920. To justify the Curzon Line as the Soviet western border, Stalin wrote to US President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1944 that the Riga peace treaty had been forced upon Soviet Russia “in a difficult hour”.

In Soviet Russia, the war against Poland, along with the Russian Civil War, exacerbated the economic crisis. This could not be eliminated by the establishment of the planned and command economy under Lenin, but was only made worse. Thus, both wars were a factor in the briefly more pragmatic New Economic Policy of the Soviet Union between 1921 and 1928. Lenin branded his own policy as war communism .

But the outcome of the war was not only important for Poland, but also for the political climate throughout Europe. The defeat of the Red Army near Warsaw could stop the advance of communism to the west, so that Soviet Russia had to give up its hopes of being able to export the world revolution to Western Europe via the “corpse of Poland”. The British Ambassador to Berlin and Head of the Entente Mission in Poland, Lord D'Abernon, summed up his perception of the conflict in the following words:

“If Charles Martell had not stopped the Saracen invasion with his victory in the Battle of Tours , the Koran would be taught in the schools of Oxford today, and the students would proclaim the holiness and truth of the teachings of Muhammad to a circumcised people . If Piłsudski and Weygand had not succeeded in stopping the triumphant advance of the Red Army at the Battle of Warsaw , it would not only result in a dangerous turning point in the history of Christianity, but a fundamental threat to all of Western civilization. The Battle of Tours saved our ancestors from the yoke of the Koran; it is likely that the Battle of Warsaw saved Central Europe, and also part of Western Europe, from a much greater danger; the fanatical Soviet tyranny. "

To what extent the expansion plans of the Soviet Union extended to all of Europe is controversial among contemporary historians. By contrast, there were right-wing extremist, völkisch circles in Germany who interpreted the war very differently in order to spread their anti-Semitic propaganda. In doing so, they used the racist cliché of equating Judaism and the Soviet system. The war also affected the left parties in Europe. Moderate socialist parties turned away from the revolutionary experiment in the Soviet Union as soon as public opinion saw them as the aggressor in the battle for Warsaw. Revolutionary groups were dampened by the apparent failure of exporting the revolution. This is how the KPD politician Clara Zetkin wrote to Lenin on the occasion of the Peace of Riga:

“The early frost of the withdrawal of the Red Army from Poland destroyed the revolutionary flower […]. I described to Lenin how it befell the vanguard of the German working class […] when the comrades with the Soviet star on their hats in impossibly old rags of uniform and civilian clothes, with bast shoes and torn-off boots, set their little, lively horses straight on the German border . "

The Ukrainian territories were divided into several states by the Peace of Riga, while Galicia was united under the Polish flag. Belarus gave up territories. After Poland had to cede the larger eastern part of Ukraine to the Bolsheviks, they were able to consolidate their rule there. The Ukrainian national movement was ended by the course of the war. Several peasant uprisings were put down by the Red Army with superior military force, especially peasants from western Ukraine, who often still had ties to Poland or the now Polish part, were subjected to severe reprisals. Many of the first inmates of the gulags were, besides Balts, Ukrainians. Only the famine of 1933 triggered by collectivization was able to break the last resistance to Sovietization.

Victims of war

There was no open discussion about the fate of the prisoners of war until the collapse of the Eastern bloc in 1990. Both states went through an economic crisis during the war and were often unable to adequately support their own people. For this reason, the prisoners of war were often inadequate. Thousands of prisoners on both sides died of the Spanish flu , which raged across the world after the world war. A Polish internment camp in Tuchola achieved terrible fame because of the high number of deaths (2561 between February and May 1921). According to joint Polish-Russian scientific studies, a total of 16,000–17,000 (Polish estimate) to 18,000–20,000 (Russian estimate) of the estimated 110,000–157,000 Soviet prisoners of war died in Polish internment camps as a result of epidemics, malnutrition and hypothermia. The number of Polish soldiers in Soviet captivity between 1919 and 1922 is estimated at around 60,000.

The military units also acted extremely brutally. Both sides tried to exploit actual or fabricated crimes of the other side for propaganda purposes, so that it is difficult to differentiate between myth and crime. However, some facts have been proven beyond doubt today. The Polish army received an order from the government to stop all sympathetic activities towards the communists. This represented a license to use force, which hit the Ukrainian and Belarusian populations particularly hard. In an exemplary case near Vilnius in April 1919, a young, allegedly communist sympathizer was killed by Polish troops, her body mutilated and put on public display. But also on the Soviet side there were attacks against the population and the war opponents. Here, too, the Red Army practiced the method used during the civil war of taking civilians hostage, either to get the local population to cooperate or to scare off potential rioters. In one case, these hostages were even murdered with sabers for military training purposes. Furthermore, the Bolsheviks did not take prisoners if they saw no possibility of keeping them “safe” after the battle. Shortly before retreating from Lida , Red Army soldiers murdered all Polish prisoners in the city. This incident also resulted in desecration of corpses. Wilna is noted as an exemplary case. During the Soviet occupation from July to October 1920, 2,000 citizens were killed, mostly by the Cheka . As a result of the Polish occupation forces in April 1920, 65 residents of the city were killed. The population of the city was around 123,000 in 1919. But there were also places like Węgrów where the occupation by the red troops was peaceful.

The Jewish community, which was viewed as an enemy by both sides, was hit particularly hard. The Poles were suspicious of the urban intelligentsia , to which many Jews belonged. This was why the state-sanctioned violence felt more strongly. The communists suspected wealthy Jewish citizens as well as Jewish small traders and craftsmen of sympathy for their opponents. In addition there were pogroms by the local population, which were often promoted by the warring parties. There is evidence of a case in Łuków in which Polish troops were actively involved in a pogrom. The population ransacked Jewish shops and the local rabbi was injured in an argument with a Polish officer. As a humiliating measure, the Polish soldiers forced the Jewish population to clean the public latrines. The Ukrainian allies of the Poles under Petlyura are also held responsible for a large number of pogroms and mass murders against the Jewish population. In conclusion, it can be said that the extent of state repression, mass executions, looting and pogroms has not yet been sufficiently quantified. The historian Reinhard Krumm writes of 60,000 Jews killed in over 1,200 pogroms.

Military casualties are estimated at 431,000 soldiers for the Red Army in both years of the war. The Polish troops lost 202,000 soldiers in 1920, this number being based on wounded, dead and prisoners.

See also

Movie and TV

- 1920. Wojna i miłość ( 1920. War and Love , Polish TV series 2010/11, 13 episodes, with Mirosław Baka as Józef Piłsudski)

- 1920 - The Last Battle ( 1920 Bitwa Warszawska , POL 2011, directed by Jerzy Hoffman )

literature

-

Norman Davies :

- White Eagle, Red Star, the Polish-Soviet War, 1919-20 . Pimlico, London 2003, ISBN 0-7126-0694-7 .

- God's Playground. A History of Poland. Vol. 1. The Origins to 1795; Vol. 2. 1795 to the Present. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005, ISBN 0-19-925339-0 , ISBN 0-19-925340-4 .

- Stephan Lehnstaedt: The forgotten victory. The Polish-Soviet War 1919-1921 and the emergence of modern Eastern Europe. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-406-74022-0 .

- Evan Mawdsley : The Russian Civil War. Birlinn Limited, Edinburgh 2005, ISBN 1-84341-024-9 .

- Richard Pipes : Russia under the Bolshevik Regime. Random House, New York 1994, ISBN 0-394-50242-6 .

- Lev Davidovič Trotsky : My life. Attempt an autobiography. From the Russ. transfer v. Alexandra Ramm. S. Fischer, Berlin 1929, Fischer paperback, Frankfurt a. M. 1974, ISBN 3-436-01965-8 .

- S. Kamenev: "Our War with White Poland", Russian Correspondence, Volume 3, Vol. 2, Nos. 7-10, July-Oct., 1922, 578-596.

reception

- Isaak Babel : The cavalry army (Budjonny's cavalry army). Malik, Berlin 1926; from d. Soot. new translation, ed. u. come over. v. Peter Urban. Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 1994 (Orig. I. Babel: Konarmija. Moskva / Leningrad 1926), ISBN 3-921592-84-4 .

- Isaak Babel, diary 1920 . Translated from Russian, edited and commented by Peter Urban. Berlin 1990 ISBN 3-921592-59-3 .

Web links

References and comments

- ^ Norman Davies: Heart of Europe. A Short History of Poland . Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York, ISBN 0-19-285152-7 , pp. 75 .

- ↑ Stephen J. Lee: Aspects of European History 1789–1980 . Routledge, London, 1982. p. 155. ISBN 0-415-03468-X .

- ^ Marek Kornat: The rebirth of Poland as a multinational state in the conceptions of Józef Piłsudski. Forum for Eastern European History of Ideas and Contemporary History, 1/2011.

- ↑ Edmund Charaszkiewicz: Przebudowa wschodu Europy (The reconstruction of Eastern Europe), Niepodległość (independence). London 1955, pp. 125-167.

- ^ Translation of a quote from a proclamation of the Revolutionary Military Council of the RSFSR, from: Evan Mawdsley, Edinburgh 2005, p. 250. Original text: “In the West the fate of the world revolution is decided. Over the corpse of White Poland lies the road to world conflagration. On bayonets we will bring happiness and peace to laboring humanity. "

- ^ Translation of a quote from Norman Davies: White Eagle Red Star. Pimlico, London 2003, p. 21. Original text: “The war of the giants has ended; the quarrels of the pygmies have begun. ”Davies is very popular as a British historian in Poland and is primarily devoted to Polish history. Various other authors have accused him of being pro-Polish.

- ^ Trotsky's quote from Evan Mawdsley, Edinburgh 2005, p. 257. Original quote in English: "We have operating against us for the first time a regular army, led by good technicians."

- ↑ Augsburger Allgemeine from July 20, 2010, column: The date .

- ↑ Вольдемар Николаевич Балязин: Неофициальная история России . ОЛМА Медиа Групп (OLMA Media Grupp), 2007, ISBN 978-5-373-01229-4 , p. 595 (Russian, limited preview in Google Book Search - translation of the title: “Unofficial history of Russia” ).

- ↑ Norman Davies: White Eagle - Red Star. The Polish Soviet War 1919-1920 . Pimlico, London 1972, 2004, ISBN 0-356-04013-5 .

- ↑ Norman Davies: White Eagle - Red Star. Pimlico, London 2003, p. 226. Original text: "if Russia wants to crush Poland, she can do so whenever she likes."

- ↑ Norman Davies: White Eagle - Red Star. Pimlico, London 2003, p. 84. Original text: “The promises of Mr. Lloyd George made on 27th June have not materialized.”

- ↑ Stalin's correspondence with Churchill, Attlee, Roosevelt and Truman 1941–1945. Berlin (East) 1961, p. 601.

- ^ Translation of a quote from Norman Davies: White Eagle - Red Star. Pimlico, London 2003, p. 265. Original text: “If Charles Martell had not checked the Saracen conquest at the battle of Tours the interpretation of the Koran would be taught at the schools of Oxford, and her pupils might demonstrate to a circumised people the sanctity and truth of the revelation of Mahomet. Had Pilsudski and Weygand failed to arrest the triumphant advance of the Soviet Army, not only would Christianity have experienced a dangerous reverse, but the very existence of the Western civilization would have been imperilled. The battle of Tours saved our ancestors from the Yoke of the Koran; it is probable that the Battle of Warsaw saved Central and parts of Western Europe from a more subversive danger - the fanatical tyranny of the Soviet. ” D'Abernon shows the typical view of the battle against the Arabs at the time. The meaning of the same is meanwhile strongly relativized on the basis of the sources at the time. See the article Battle of Tours and Poitiers .

- ↑ Orlando Figes: The Tragedy of a People. The epoch of the Russian Revolution from 1891 to 1924. Goldmann, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-442-15075-2 , p. 741; Figes denies Soviet Russia's urge to expand into Europe, while his colleagues Davies and Mawdsley take this view.

- ↑ Doctoral thesis by Walter Jung at the University of Göttingen (PDF; 5.4 MB)

- ↑ Norman Davies: White Eagle - Red Star. Pimlico, London 2003, p. 265. Original text of the quotation in English: The early frost of the Red Army's retreat from Poland blighted the growth of the revolutionary flower… I had described to Lenin how it had affected the revolutionary vanguard of the German working class ... when the comrades with the Soviet star on the caps, in impossibly old scraps of uniform and civilian clothes, with bast shoes or torn boots, spured their small, brisk horses right up the German frontier.

- ↑ Zbigniew carpus : Jency i internowani rosyjscy i ukraińscy na terenie Polski w latach 1918-1924. (Russian and Ukrainian prisoners of war and internees in Poland, 1918–1924). Toruń 1997, ISBN 83-7174-020-4 ( Polish table of contents ). English translation: Russian and Ukrainian Prisoners of War and Internees in Poland, 1918–1924. Adam Marszałek, Wydawn 2001, ISBN 83-7174-956-2 ; Zbigniew Karpus, Alexandrowicz Stanisław , Waldemar Rezmer : Zwycięzcy za drutami. Jeńcy polscy w niewoli (1919–1922). Documentation i materiały. (Winner behind barbed wire: Polish prisoners of war, 1919–1922. Documents and materials).

- ↑ a b Алексей Памятных: ПЛЕННЫЕ КРАСНОАРМЕЙЦЫ В ПОЛЬСКИХ ЛАГЕРЯХ . Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ^ Polish-Russian Findings on the Situation of Red Army Soldiers . Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ↑ Polsko-Rosyjskie ustalenia dotyczące losów czerwonoarmistów w niewoli polskiej (1919-1922) . Naczelna Dyrekcja Archiwów Państwowych. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- ↑ Jency wojny 1920 - Spor o History o z Myšľa przyszłości . Polski Instytut Spraw Międzynarodowych. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ↑ Głuszek: Anty- Katyn, głos w sprawie . Polityka Wschodnia. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- ^ Polscy jeńcy wojenni w niewoli as well asckiej . Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ↑ Vo imya Demokratij. in: Pravda . Moscow, May 7, 1920. Quoted from Norman Davies: Red Eagle - White Star , p. 238.

- ↑ Stéphane Courtois , Nicolas Werth , Andrzej Paczkowski and others give an overview of hostage-taking as an instrument of repression in the civil war, but also as a means of economic policy . a .: The black book of communism . Piper Verlag, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-492-04552-9 , p. 107 ff.

- ↑ Norman Davies describes the incident on p. 239 of White Eagle - Red Star , referring to the photographic documentation 1917–1921 of the Sikorski Institute in London, Photo No. 10116.

- ↑ ibid. P. 240. He refers here to the Public Records Office, London WO 417/9/60.

- ↑ Ibid. P. 240. He refers here to the Public Records Office, London WO 106/973, FO 371 5398/572.

- ^ Joachim Tauber and Ralph Tuchtenhagen: Vilnius. Little history of the city. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne-Weimar-Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-412-20204-0 , p. 180.

- ↑ ibid. P. 240. Davies here refers to the Warsaw archive Archiwum Akt Nowych .

- ↑ Orlando Figes: The Tragedy of a People. The epoch of the Russian Revolution 1891 to 1924. Complete paperback edition. Goldmann, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-442-15075-2 , p. 718. The author refers to a study of Jewish organizations in the Soviet Union, in which the total number of Jewish victims was estimated at 150,000 to 300,000. However, this information applies to the entire former tsarist empire and for the entire duration of the Russian civil war .

- ↑ Line up under cruel murder. Deutschlandfunk from March 18, 2006.

- ^ Evan Mawdsley: The Russian Civil War. Birlin Ltd., Edinburgh 2002, ISBN 1-84158-064-3 , p. 257.