Spanish flu

|

|

| The three waves in Great Britain | |

| Data | |

|---|---|

| illness | Influenza |

| Pathogens | Influenza virus A / H1N1 |

| Beginning | 1918 |

| The End | 1920 |

| Confirmed Infected | 500 million (estimate) |

| Deaths | 20 million - 50 million |

The Spanish flu was an influenza - pandemic caused by an unusually virulent descendant of the influenza virus ( subtype A / H1N1 has been caused) and between 1918 - the end of the First World War - and 1920 spread in three waves and a world population of about 1 According to the WHO, 8 billion claimed between 20 million and 50 million human lives, estimates range up to 100 million. This means that more people died from the Spanish flu than in the First World War (17 million). A total of around 500 million people are said to have been infected, which results in a mortality of 5 to 10 percent, which is significantly higher than for diseases caused by other influenza pathogens.

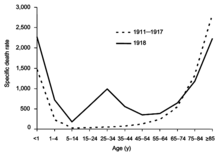

A peculiarity of the Spanish flu was that 20 to 40 year olds in particular succumbed to it, while influenza viruses otherwise particularly endanger small children and old people. Variants of the subtype A / H1N1 caused the outbreak of the Russian flu in 1977/1978 and the “swine flu” pandemic in 2009 . The Asian flu (1957) and the Hong Kong flu (1968) were based on other subtypes, but the majority of the internal genes come from the Spanish flu virus, which is why it was referred to as the “mother of all pandemics” in 2006.

The term "Spanish flu"

The name Spanish flu came after the first news of the disease came from Spain ; As a neutral country, Spain had relatively liberal censorship during the First World War , so that, unlike other affected countries, reports about the extent of the epidemic were not suppressed. The Reuters news agency reported on May 27, 1918 that the Spanish King Alfonso XIII. is sick. The Agencia Fabra cabled Reuters in London :

“A Strange Form Of Disease Of Epidemic Character Has Appeared In Madrid. The Epidemic Is Of A Mild Nature, No Deaths Having Been Reported ”

“A strange epidemic disease has occurred in Madrid. This epidemic is harmless, no deaths reported so far. "

Influenza became completely “ Spanish ” when the Spanish health director Martín Salazar announced on June 29, 1918 that he had no reports of a comparable disease in the rest of Europe. From the end of June 1918, the international press increasingly used the term “Spanish flu”, which was also promoted by some warring governments in order to cover up the actual spread.

Spain

In Spain, the disease was initially called Soldado de Nápoles (Soldier of Naples) because it spread as quickly as a song of this name that was very popular at the time and was sung for the first time in an operetta (composer: Francisco Alonso ) shortly before the outbreak of the pandemic was. In contemporary Spanish sources, the term Spanish flu only appeared when the authors complained about the term. Contemporary Spanish observers probably rightly assumed that the pathogen had been introduced from France, since around 24,000 Spaniards were working in France in the winter of 1917/18, 9,000 of whom had returned by the time the epidemic broke out. Today the pandemic in Spain is mostly referred to as "Pandemia de gripe de 1918" and rarely as "Gripe española".

USA and UK

Despite the misleading name, most scientists today assume that the pandemic originated in the United States . The war-related increased mobility , which was still untypical for that time, favored global expansion. American soldiers called it three-day fever or purple death (because of the discoloration of the skin), British soldiers called it flu or "Flemish flu" because of the infection in the trenches of Flanders.

Germany

In the German press it was not allowed to report diseases on the fronts ( Eastern Front and Western Front ), but from the beginning of June 1918 - also on the first pages of the newspapers - it was allowed to report about civilian victims. In Germany it was occasionally called "lightning catarrh" or "Flanders fever". Other names were Spanish disease, flu, pneumonia, pneumonia.

Austria

The Spanish flu hit Austria-Hungary as the monarchy was about to collapse. Towards the end of the First World War , many people were malnourished, malnourished , exhausted, depressed, demoralized or traumatized and thus susceptible to infectious diseases. There was a lack of medicines, doctors and nursing staff. Public institutions were not fully capable of acting.

In Austria around 21,000 people died of the pandemic in 1918/19. Most of the fatalities from the Spanish flu were in the 15 to 40 age group. The second wave was most violent in October / November 1918.

In Austria, the only and first country in Europe, Emperor Karl ordered the creation of its own ministry for public health in autumn 1917 . But it was not until July 30, 1918, that the Ruthenian professor of medicinal chemistry at the Bohemian University in Prague, Johann Horbaczewski, was appointed Minister of Public Health. Horbaczewski tried to appease and claimed that this epidemic was not pulmonary plague and that it was generally benign. His few activities showed all the impotence and helplessness during this time.

France

French military doctors initially veiledly spoke of maladie onze (disease eleven). Today the terms flu espagnole or Pandémie grippale de 1918 are usually used.

Hypotheses on geographical origin

Where the Spanish flu first manifested is not entirely certain. This can largely be seen against the background of the First World War. During the fighting in Europe, especially on the Western Front , thousands of soldiers died every week at this time. Both the press and local health authorities therefore focused little on the first flu cases in the spring of 1918, especially since few people succumbed to the disease during the first wave. There are currently three theories under discussion, with the most likely pointing to the US as a starting point.

Possible starting point China

Apart from various propaganda theses, the place of origin was initially suspected in China. An epidemic broke out in Harbin in October 1910, the symptoms of which were similar to those of the Spanish flu, as was already apparent in 1918. In December 1917, another respiratory disease broke out in northern China, again with similar symptoms, which lasted until April 1918 and killed around 16,000 people. Since the end of 1916, China, with the Chinese Labor Corps (CLC), has sent workers to Europe for the Allies, a total of around 185,000 men. The CLC was mainly recruited in the provinces of Shantung , Hopei and Shanxi affected by the second outbreak , concentrated in barracks in the British-east Chinese lease area Weihaiwei and mostly across the Pacific to Canada, by rail to the Canadian east coast to Halifax or later to New York and from spent there in France. Symptoms of a flu-like infection were frequently observed both among the soldiers guarding the Chinese on Vancouver Island and at the CLC itself, and fatal pneumonia occurred. In 1918 there were 17 camps in the Nord-Pas de Calais region, each containing up to 96,000 men. The headquarters of the CLC were in Noyelles-sur-Mer , the main camps in Boulogne-sur-Mer , Wimereux and Etaples , where the Chinese unloaded the British ships. However, this theory cannot provide more than indications, especially since it was not possible to clarify what kind of disease broke out in Shanxi at the end of 1917. Apart from that, the initially relatively low number of victims in the CLC speaks against this original hypothesis, which only increased after that of the nearby Allied soldiers.

Possible starting point in northern France

Another theory is that the epidemic originally broke out in a very large military camp near the French city of Étaples , which was home to around 100,000 people a day, including Chinese from the CLC. In December 1916, influenza was rampant in this camp, which was similarly observed in the military bases of Rouen and Aldershot . At the time, doctors spoke of “purulent bronchitis”, and autopsies found similar findings to those later on with the Spanish flu. The delay until the actual pandemic broke out could be explained by the fact that the virus of that time survived in the context of small, limited epidemics and developed its high virulence during this period due to molecular changes.

Probable starting point in the United States

The third, currently most probable thesis is that the first virulent flu outbreaks occurred in the USA in January 1918 and that it was spread worldwide from there through troop movements - the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe were massively strengthened at this time. It was set up in the 1940s by the Australian Nobel Prize in Medicine, Frank Macfarlane Burnet , and was later extensively documented by the American historian Alfred W. Crosby . The studies by evolutionary biologist Michael Worobey now support this thesis: seven out of eight genes in the virus are very similar to influenza genes found in birds in North America. In addition, a genetic connection to u. a. Equine influenza , which was rampant in the USA in 1872, was identified, to which reports of equine flu spreading simultaneously with Spanish flu in the cavalry stables of the warring armies.

Course of the disease / symptoms

The main specific symptoms were similar to those of other influenza diseases:

- sudden onset of illness,

- pronounced feeling of illness throughout the body: headache and body aches , back and lower back pain, tiredness and fatigue, lack of drive, inability to concentrate, listlessness,

- sometimes chills or chills ,

- dry cough , agonizing irritable or convulsive cough, sometimes severe irritation in the throat and pharynx .

- This was followed by a fever , temperature rising to over 40 ° C over a day or two .

- Reduced heart rate to 60 a minute or less.

- Duration of illness on average three, less often five or more days.

- In severe cases, pneumonia occurred in the form of primary pneumonia due to the flu virus or secondary pneumonia due to bacterial superinfections , sometimes accompanied by rapidly developing hemorrhagic fever and bluish-black discoloration ( cyanosis ) of the skin caused by the lack of oxygen.

- Death usually occurred on the eighth or ninth day of the illness, mostly caused by the secondary bacterial infection.

Autopsies showed that the respiratory tract was often affected in those who had died from the flu, and occasionally the mediastinum as well . Foci of inflammation were mostly found in the lower lobes of the lungs, and in many the pleural cavity was ulcerated. The spleen was often enlarged, more rarely the liver , it and the kidneys sometimes showed damage, the meninges often irritation.

Diagnosis was not always easy as the symptoms observed differed, with some patients mainly suffering from pain in their limbs. Due to the severe chills of many patients, Spanish doctors initially guessed it to be malaria or typhus abdominalis .

Survivors were often marked by severe tiredness and chronic exhaustion for weeks, and depression was not uncommon as a consequence. Those who survived pneumonia were often faced with a long and arduous convalescence .

As a result of the influenza infection, many people suffered from neurological dysfunction for the rest of their lives , as pathologists have repeatedly described acuta haemorrhagica encephalitis , at the time known as flea bite encephalitis, and its consequences. Furthermore, a notable increase in cases of lethargic encephalitis was observed. It is a form of encephalitis that causes lethargy , uncontrolled sleep attacks, and a temporary Parkinson's disease- like disorder, and in some cases, permanent post-encephalitic Parkinsonism. However, a direct connection between lethargic encephalitis and the Spanish flu has not been proven; in by McCall et al. in 2001 and Lo et al. Tissue samples examined in 2003 found no evidence of the influenza virus.

Spread and course of the pandemic

The Spanish flu occurred in three waves: in the spring of 1918, in the autumn of 1918 and again in many parts of the world in 1919. The first wave that spread in the spring of 1918 did not show a noticeably increased death rate. It was not until the autumn wave of 1918 and the later, third wave in spring 1919, that the mortality rate was exceptionally high . At the height of the “autumn wave”, the Prussian and Swiss health authorities estimated that two out of three citizens were sick.

From autumn / winter 1918 between 20 million and 50 million people died worldwide, assumptions range up to 100 million. This means that more people died from the Spanish flu than in the First World War (17 million).

The world population at that time was around 1.8 billion, so it lost around one and a half to 2.8 percent. Generally speaking, the flu mortality rate was lowest in highly industrialized countries, at around 0.5 percent, and more than 0.6 percent in the US as a starting point. In the economically less developed countries in Europe or outside of it, the mortality rate was mostly over one percent, for example in Mexico over three percent. In Italy there were regions with extremely high mortality rates, especially the regions of Latium , Calabria and Emilia . Nations with a high proportion of indigenous people were most affected. On some small islands in the Pacific, more than 20 percent of the population died. Only very small, isolated islands like St. Helena completely escaped the pandemic.

The exact number of those who died of the flu can no longer be determined, as remote regions were also affected and the number was not reliably recorded in countries such as Russia due to the turmoil after the war and civil war . The US Army lost about as many infantry -Soldaten by the flu as by the fighting during the First World War . About 675,000 people died in the USA and about 300,000 in the German Reich. In India alone , 17 to 20 million people are said to have died of the Spanish flu, which appears to be well documented by the subsequent census of 1921.

The time span of just one year for three pandemic waves to occur is a peculiarity of the Spanish flu. In other influenza pandemics, such as 1889/90, intervals of eight to nine months were observed between the individual waves. The cause of these “compressed” waves is unclear. Numerous anecdotal reports as well as statistical data from Spain indicate that people who were ill during the first wave enjoyed relative protection against recurrence in the second wave.

The lethality of this form of the influenza virus remains unclear, as there are no exact data on the number of sick people; it is suspected to be higher than 2.5 percent. Other influenza pandemics have a mortality rate of less than 0.1 percent.

The base reproduction number of the epidemic was 2 to 3.

The three waves

The first wave (spring and summer 1918)

outbreak

The flu epidemic likely started in Haskell County , Kansas, USA . At the beginning of 1918, the country doctor Loring Miner treated numerous patients there whose flu symptoms were considerably more severe than those previously known. Miner described the course of the disease as extremely fast and occasionally fatal. In the local newspaper Santa Fe Monitor there was talk of widespread pneumonia as early as mid-February and a few days later that "almost everyone in the country has flu or pneumonia". Miner was so concerned about this outbreak that he turned to the United States Public Health Service (PHS), but they did not respond to his request for assistance. The report of a form of flu with an unusually severe course, however, was reflected in the Public Health Reports of the PHS on April 5, 1918 : “On March 30, 18 cases of influenza were reported from Haskell, Kansas, of which 3 were dead were". Thanks to this report, medical history was able to reconstruct a possible course of infection. There is evidence that at least three people from Haskell County were drafted into the US Army training camp at Camp Funston in late February . On March 4, the kitchen sergeant ( mess sergeant ) Albert Gitchell fell ill with the flu. He suffered from a sore throat, fever and headache, typical signs of the flu. Hundreds of other soldiers showed the same symptoms and filled the emergency hospital within a few hours. Gitchell wasn't the first patient to be infected by the Spanish flu, but he was the first to be recorded. He is therefore considered patient zero , even if the disease had already reached New York by this time and significantly increased death rates from respiratory diseases had been reported in the US Army since December 1917.

Three weeks later there were 1,100 seriously ill people and 38 deaths in the training camp, which had an average of 56,000 recruits. The soldiers called the disease a three-day fever or knock-me-down fever. The disease spread very quickly from the Fort Riley military base training camp.

distribution

In mid-March, there were outbreaks in other military camps, such as Camp Forrest in Tullahoma, Tennessee and Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia . The disease spread to the civilian population from the camps. Of the 1,900 inmates in California's San Quentin Prison , around 500 fell ill. The flu outbreaks associated with life-threatening pneumonia quickly spread across the country. In the large cities of the Atlantic coast, the mortality rate rose noticeably, sometimes even before the striking outbreaks in the military camps. The well-known silent film actor Joseph Kaufmann died on February 1, 1918 in New York, and his parents in April.

From the time the flu broke out in Kansas until August 1918, more than a million American soldiers arrived in Europe . There had never been such brisk traffic between the New and Old World , but also troop contingents from the British Empire . The First World War thus accelerated global expansion. On the other hand, the British naval blockade of Germany and the locking bolt on the western front could have slowed down the spread to Germany. In addition, mobility within Europe was severely restricted by the war, especially between Germany and France, but this did not slow down the spread of the epidemic from west to east. Possible explanations include the spread via neutral states such as Switzerland, which was badly affected at the time, through prisoners of war and looting of Allied fallen soldiers or through air currents to the front lines, which were often only a few dozen meters apart.

The disease apparently reached France on US troopships . Flu cases from the French port city of Brest are documented for the beginning of April 1918 , from where they spread both to the civilian population and among soldiers. The first soldiers suffering from the flu were brought to the French hospitals on April 10th. The flu epidemic reached Paris at the end of April . In the first two weeks of May 1918, the British Navy reported over 10,000 cases of sickness and was unable to sail.

In German-speaking countries, the new disease was reported in May 1918 at the latest.

“The secret of the new disease, which is said to have gripped such a considerable percentage of the Spanish population, is, as the doctors explain to us, far too vaguely described in the present communication to allow a conclusion from a medical point of view. Only the epidemic character seems to be certain, as indicated by the large number of diseases as well as the rapid spread. The symptoms of the disease are not even hinted at. Perhaps it's an influenza epidemic, a well-known spring disease in our area too. This disease, also known as "flu", can occur more or less violently epidemically or endemically, as was the case more than a decade ago in Vienna and individual areas of Austria. "

“The Wolff Bureau reports: It is striking how high the number of deaths due to illness in the American army is. It is said to exceed the number of those who fell in the field by more than three times. Pneumonia is cited as the cause of death in around three quarters of cases. According to " New York World " of April 25, deaths from influenza and pneumonia are extremely common among the troops in America . In the second week of April 285 and in the third week of the same month 278 deaths from illness were reported. "

Numerous cases were reported in June from India , China , New Zealand and the Philippines . In the German Empire , too , the peak of the first wave was in June. In the port of Manila, over two thirds of the dock workers fell ill so that ships could no longer be unloaded. Global expansion has been accelerated by migration, troop movements, trade and colonialism.

Denmark and Norway were mainly affected in July; in the Netherlands and Sweden , the first flu epidemic peaked in August. In Australia, 30 percent of Sydney's population contracted the flu in September.

On July 13, 1918, an article appeared in the edition of the British medical journal The Lancet in which three doctors speculated that the current epidemic may not have been flu because the course was so brief and, very often, without complications. At the time, they were apparently still unaware that there were already noticeable exceptions to the largely harmless course. At the end of May 1918, almost five percent of the soldiers stationed there died of the flu or its consequences in a small French military camp. In Louisville , Kentucky , the pattern emerged that, from today's perspective, is one of the characteristic features of the Spanish flu: a good 40 percent of the deaths belonged to the age group of 20 to 35 year olds.

Although the flu wave was not decisive for the war, it weakened the German troops, which were in many ways badly hit, and can be seen as an accelerator of the defeat. The German spring offensive in 1918 got stuck and the last German offensive , after a counterattack on July 18, 1918, brought about the definitive turnaround in the war in favor of the Allies. In the steel thunderstorms Ernst Jünger wrote about the situation on the German front in July 1918: "Young people in particular died overnight."

The German General Erich Ludendorff , de facto Chief of the Supreme Army Command , stated in his war memoirs for June 13, 1918 that - in addition to the poor supply situation - the flu outbreaks in the troops had been a serious problem, and postponed on October 3, 1918 compared to Chancellor Max von Baden, who soon became ill with Spanish flu , the looming defeat, among other things, on the supply situation, the overwhelming superiority of the Allies as well as the low morale and the poor condition of his troops. He named the raging flu epidemic as one of several causes for the last two points. Although Ludendorff's statements primarily wanted to divert attention from his wrong strategic decisions with the formation of legends , other reports also show that the flu epidemic hit the German army less than, for example, the American armed forces, but because of the desperate situation of the German army, it had more impact . Between 500,000 and 708,000 German soldiers fell ill with the flu.

The Allied press occasionally speculated that the infection came from German submarines and German prisoners of war or that it was even triggered by Germany as planned. This was underpinned, for example, with illnesses on submarines interned in Spain, including the infamous SM U 39 located in Cartagena . The New York Times called for the pandemic to be renamed "German flu". Since Germany had started waging war with poison gas in 1915 , the suspicion was raised that it had now also initiated biological warfare and was systematically releasing the "microbes".

The second wave ("autumn wave" 1918)

outbreak

The beginning of the autumn wave can be scheduled roughly in the second half of August 1918. The virus had undergone a small but momentous change between spring and autumn: it was no longer as well adapted to birds, but much better adapted to humans. It may have broken out for the first time on the Norwegian freighter Bergensfjord , which docked on August 12, 1918 with 200 sick crew members in Brooklyn ; four people who had died on board had already been handed over to the sea. Four port cities followed more or less simultaneously: Boston in the USA, Brest (August 22nd) on the French Atlantic coast, Dakar in Senegal and Freetown , the capital of the then British colony of Sierra Leone in West Africa . The eruption in Freetown coincides with the arrival of the British passenger ship HMS Mantua, which had been converted into an auxiliary cruiser, on August 15, and that in Dakar with the arrival of the HMS Ebro on August 19. The flu had previously broken out on both ships. By the end of September, two-thirds of Freetown's residents had contracted the flu. For every hundred sick people there were three fatalities. Since the disease broke out every time a ship arrived around the Atlantic, according to consistent reports, one got the impression that the new wave of flu was brewing at sea.

In Boston , the Spanish flu, with the more aggressive course of the disease, first appeared among marines on August 27th . The first civilian patient was admitted to Boston City Hospital on September 3rd. The course of the disease is well documented in the Camp Devens military base , which was only thirty kilometers west of Boston. At the time, 45,000 soldiers were on the base, which was actually designed for 35,000 soldiers, and 5,000 soldiers were housed in a tent camp on the grounds of the base. On September 8, the first soldier fell so severely ill that he was initially suspected of having meningitis . The next day, another dozen men in his unit fell ill. On September 23, the number of sick people was 12,604 soldiers. 63 soldiers died that day. The conditions in which the sick were cared for may be typical of countless other military hospitals and hospitals around the world where the Spanish flu raged. Although the USA suffered less from the consequences of the First World War than the European countries, there was a lack of nursing staff . Every available space was used to set up hospital beds. Fresh bedding was in short supply, so that the sick lay on dirty and blood-stained sheets. The dead piled up in the corridors of the morgue and their funeral could hardly be kept up.

In an attempt to contain the disease, senior military doctors attempted to ensure that only the most necessary ship movements were permitted. Before leaving port, the ships should go through a quarantine to prevent sick people on board. However, the military doctors did not succeed in enforcing this measure. They did not receive any form of support from the Surgeon General of the United States Rupert Blue , who headed the US Public Health Service , nor did they find any support within their own organization. The US military successfully resisted this measure, as the troops fighting in Europe urgently needed reinforcements. This decision brought with it a high risk for the soldiers to be shipped. Of 100 soldiers who fell ill on board a troop transport on the way to Europe, six died. The mortality was more than twice as high as that of the sick on land.

Despite the quarantine measures initiated, the disease spread very quickly. The number of deaths in the United States as a result of the flu wave rose from 2,800 in August to at least 12,000 deaths in September. Doctors from the cities in eastern North America that were already affected sent their colleagues in the west dire warnings:

“Find every available carpenter and joiner and have them make coffins. Then take road workers and have them dig graves. Only then do you have a chance that the number of corpses will not rise faster than you can bury them. "

In less than four weeks, the disease had spread to New Orleans , Seattle, and San Francisco . The outbreak of the flu could happen very quickly. At a military base in Georgia , only two illnesses were reported on one day in September 1918, and 716 the next day. One of the hardest hit cities in the United States was Philadelphia , where 711 people were killed in a single day in October 1918. Since the city morgue was designed for a maximum of 36 dead, the dead had to be stored in four rows in corridors and rooms. In the early autumn of 1918, a large military parade took place in Philadelphia , which attracted numerous citizens to the streets and squares. Within a week after that, almost 5,000 people died in Philadelphia, after six weeks it was more than 12,000, which is more than eight times as many as in restrictive St. Louis. In St. Louis, on the other hand, the authorities put on restrictions on public life and quarantine . Schools, cinemas, libraries and churches were closed. This St. Louis strategy is copied as a successful method to this day. According to a 2007 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association of measures in 43 US cities during the second wave in the fall of 1918 / spring 1919, combinations of public measures ( nonpharmaceutical interventions , NPI), in particular school closings and bans on public gatherings (church, Theater et al), which were in effect for an average of four weeks, were particularly effective in lowering the peak death rates and the total number of deaths (excess mortality). Another 2007 study also showed that US cities that took a combination of several public policies early in the epidemic cut peak mortality rates in half compared to other cities that did not. However, this applied to a consistent combination of measures; no such reduction could be proven for any individual measure. In many cases, the wearing of face masks was also required. Failure to comply has resulted in fines, for example, and there have also been cases where someone in San Francisco who refused to wear a mask was shot dead by an officer. These experiences also played a role in the drastic measures taken in Germany against the Covid 19 pandemic in March 2020 .

In Montreal , Canada , where 201 people succumbed to the flu on October 21, priests gave the sacraments of death on the street. The week of October 17-23, 1918, saw the highest mortality ever recorded in the United States, with 21,000 people dying from the Spanish flu during this period.

In Germany there were considerable restrictions in autumn 1918, which affected the postal system, telecommunications offices and local public transport. "Flu holidays" were also widespread in German schools. Mines, factories and agriculture were shut down, but responsibility for action was left to local administrations as the regions were affected very differently. Meetings, restaurants and services were not prevented in the entire German Empire.

distribution

As in North America , the disease spread around the world. The effects in Europe were followed less closely. The First World War was still more in the focus of the press and public attention.

That was all the more true in Germany. Since 1914 the German armies had fought unsuccessfully against the Allies and the arrival of American soldiers on the continent changed the balance of power on the Western Front massively. In Germany, the flu was only seen as a minor issue, because the poor supply situation with the starvation winters and political uncertainty were added to this. German doctors quickly found that a noticeable number of 20 to 40 year olds died without symptoms of deficiency. This gave rise to the theory of an overreaction of the immune system , this resilient group of people today known as the “ cytokine storm ”. This overreaction often triggers rapid death from suffocation .

According to official statistics, 24,449 people died of Spanish flu in Switzerland between July 1918 and the end of June 1919. This corresponds to 0.62 percent of the entire population in 1918. In the absence of a medical reporting requirement, it is assumed that the number of unreported cases is large.

South America , Asia , Africa and the Pacific islands were also badly affected .

The pandemic in Asia claimed more than half of the victims. In India, the mortality rate was particularly high, with an estimated five deaths per hundred sick people. The number of deaths in India has been estimated at up to 20 million people. This was reinforced by the fact that India was ravaged by famine at that time . Many from the rural regions moved to the larger cities because they hoped for better care there. The risk of infection was particularly high in the cramped conditions. For China, the number of deaths was estimated at over nine million.

The epidemic also raged heavily in the areas of present-day Tanzania , Zambia and Mozambique , which were damaged by the colonial wars and the World War .

New Zealand was hit by the flu especially in Black November 1918 when the first troops returned. 8,600 people died of the disease in New Zealand, more than twice the number of New Zealand soldiers killed in World War I. At the height of the crisis, all public life came to a standstill. The Māori were particularly hard hit by the flu epidemic . In the remote Māori communities, the outbreak usually came without warning. Often so many were affected that there was no one left to care for the sick or to bury the dead. The situation was similarly dramatic in Samoa , where a fifth of the population or 7,500 people died. The Samoa islands aroused the interest of science insofar as the population in Western Samoa fell by 22 percent within a few weeks, while in American Samoa, about 70 kilometers away, the flu probably did not occur because of the rigid quarantine measures there.

The Spanish flu branded itself as a collective memory of the Americans: a total of around 675,000 civilians died in the USA and thus more citizens than US soldiers on the battlefields of both world wars.

In America, too, it was mainly indigenous peoples who were affected; the virus obviously hit people who were even less immunologically immune than those who had immigrated from Europe. In Mexico there are said to have been almost 440,000 deaths, in British Guyana primarily Indians and thus 75 percent of the population fell ill. In North America, Inuit in Alaska and northern Canada, as well as Indians, were particularly badly affected, a quarter of them fell ill and 25 percent of them died. Some Inuit villages no longer had an adult population, and children were found in the arms of their dead mothers. A single person brought the virus to the village of Wales, and a week later 178 of the 396 residents were dead. In some villages, 85 percent of the residents had died, and most of the survivors were children. In the Inuit settlement of Cartwright in Labrador , Canada , 96 of the 100 people living there suffered from the flu at the end of October 1918, of whom 26 died. In many families, all members were so ill that they were unable to take care of food or the fire. Only 59 of the former 266 inhabitants had survived in the Okak settlement. Missionaries found an eight-year-old girl who allegedly survived five weeks at −30 degrees Celsius next to four corpses by melting snow with Christmas candles to obtain drinking water.

The third wave (local herd 1919-1920)

In February 1919, there was another flu epidemic, first in Great Britain and from May 1919 in other countries as well, which hit the USA especially in the spring of 1920, but which in its course was no longer as fatal as the second. Since mainly younger people died, it is attributed to the Spanish flu.

The following flu waves - as in Germany in the winter of 1932/33 - were of a lesser extent and a different age distribution, so that they are no longer associated with the Spanish flu.

Reactions and countermeasures

Because of the fulminant course of the disease, some researchers initially doubted that the Spanish flu was even a form of influenza. Among other things, a form of lung plague was suspected to be the cause of the pandemic . Even at that time, medical literature was already talking about “viruses”, but at that time in the sense of “pathogens” or “poison”. That it was a virus in today's sense only became clear after the isolation of influenza viruses in 1933.

A number of different rumors about the origin of the disease were circulating in public. A widespread hypothesis was that the flu was imported from Spain in tins, which were poisoned by the Germans who had brought the Spanish canning plants under their control. According to another theory, the disease broke out in Sing Sing Prison and was brought to Europe by American soldiers. Even climatic factors are said to have played a role; Soldiers often sleep in the open air and they came into contact with the flu virus through the dew.

Americans suspected that the influenza outbreak was due to the consumption of fish that had been poisoned by the German enemy, saw dust as a cause of illness as well as unclean pajamas or too light clothing, considered closed windows as well as open or careless handling of old books and did not rule out cosmic influence either. The rumor that Germans contributed to spreading the disease in the United States was even officially supported. In September 1918, the head of the U.S. Health and Sanitation Section of the Emergency Fleet Corporation Lt. Col. Philip Doane officially states that, in his view, Germans caused the disease:

“It would be very easy for German agents to release the pathogen in a theater or any other place where a lot of people are gathered. The Germans started epidemics in Europe. There is no reason why they should be more careful with America. "

Quarantine measures were initiated by the health authorities in some countries very early on. As early as the second half of August 1918, the Surgeon General of the United States had ordered that the health authorities in the USA should quarantine ships with sick people on board in all ports. However, due to the war effort, this turned out to be hardly feasible. In Toronto , Dr. Hastings, a health department employee, gave advice on how to avoid contagion. This included the recommendation to avoid crowds, to keep your mouth, skin and clothes clean and to keep the windows open as much as possible. Keep cool when walking and warm when driving or sleeping. Hands should be washed before eating and the food should be chewed well. The accumulation of digestive products in the body should be avoided and one or two glasses of water should be drunk immediately after getting up. Towels, napkins and cutlery that has been used by others should be avoided. You should also avoid tight clothing, shoes or gloves.

In New York, spitting in the street was a criminal offense. About 500 people were arrested for violating the law. Other cities ordered mouthguards to be worn and fined those who violated them. The New York Health Board underlined the requirement with the slogan "Better be ridiculous than dead." Later studies showed that banning mass gatherings and the requirement to wear mouth and nose protection reduced the death rate in major American cities by up to 50 percent.

Spanish flu therapy

The non-drug treatments, dietary, physical and naturopathic measures included, to hot air and electric light baths, sweating and Prießnitz cures , baths, wraps and envelopes, were mostly ineffective. The same applied to the multitude of questionable drugs recommended to the medical profession in numerous articles: Malafebrin, Vioform, Sublimate , Creosote . With the health disaster culminating, there was no time for critical drug proving.

Since effective specific remedies were not available, the doctors concentrated on alleviating the symptoms: antipyretic therapy was already in the foreground with the influenza of 1889/90, and many febrile drugs experienced an astonishing renaissance in 1918/19, not just the familiar ones Quinine , but also the pharmaceutical specialties antipyrine , salipyrine , antifebrine and phenacetin . The triumphant advance of the pyramidon and acetylsalicylic acid took place since the 1890s . The latter has now become the central drug in the fight against Spanish flu. If a strong sedative and anti-neuralgic effect was desired in severe cases, the doctors in 1918 resorted to substances such as opium , morphine , heroin or cocaine .

Narcotic and anesthetic cough suppressants such as codeine , the subcutaneously injectable opium extract Pantopon or glycerine preparations for inhalation were available to combat the annoying, often agonizing dry cough. Camphor benzoin, eucalyptus oil or ipecacuanha powder were prescribed as expectorants . A leitmotif of symptomatic flu treatment was maintaining cardiovascular function, especially in life-threatening pneumonia, for which digitalis , strophantine , caffeine , strychnine and camphor were used, and in special cases adrenaline . Oxygen inhalation was an option to alleviate shortness of breath, but the associated side effects limited its value. Advertisements in the newspapers advertised fig syrup or eucalyptus ointments as medicinal products. Antiseptic sprays should keep your mouth and nose clean.

Great but ultimately futile hopes were placed in specifically effective chemotherapeutic agents such as the syphilis drug Salvarsan and its successor Neosalvarsan, furthermore in colloidal silver preparations such as collargol, septargol, electrargol and fulmargin and finally the diuretic urotropin , which has proven itself in urology , its germicidal and staphyloid effects Strep infection was out of the question. The use of the quinine derivatives Eukupin, Optochin and Vuzin was widespread, albeit without resounding success.

Statistical anomalies

If one considers the lethality of influenza diseases as a frequency distribution over the age of those affected, one normally obtains a "U-shaped" distribution, the maximums of which are in the very young and very old population groups. The lethality of the Spanish flu, however, follows a "W-shaped" distribution; a peculiarity, as it was already observed in the pandemic of 1889/90 ( Russian flu , possibly through A / H3N8 ). The additional, atypical maximum is in the range of 20 to 40 year olds. Overall, the deaths of 20 to 40 year olds are estimated at almost half of the total pandemic deaths. As a uniqueness of the Spanish flu, the mortality rate for people under 65 years of age was significantly higher than for those over 65; about 99% of the deaths were in the first group, compared with 36% and 48% in the 1957 ( Asian flu from H2N2 ) and 1968 ( Hong Kong flu from A / H3N2 ) pandemics .

Answers to these questions are sought, among other things, in the previous influenza exposure of the various age groups. One possible explanation for the anomalies is a virus that was circulating before 1889, which caused a partial immunization and thus led to infection-intensifying antibodies . One problem with this assumption, however, is that this predecessor virus disappeared around 1889, but must have reappeared almost 30 years later. Another attempt to explain it is based on the doctrine that the immune system responds particularly effectively to the first variant of a virus it is confronted with, and is therefore less well tailored to other types of pathogen strains. If the influenza pandemic from 1889 to 1895 is actually based on the virus subtype H3N8 (see above) and people who belonged to the age group between 20 and 40 came into contact with influenza for the first time in 1918, then they would have had the Spanish flu did not have adequate immune defenses. Elderly people, on the other hand, may have had relative protection because they had previously been exposed to influenza more similar to the Spanish flu. However, there is no clear evidence of this.

According to Gibbs et al. in Spektrum der Wissenschaft from January 2006, a factor in the unusual distribution was also the atypically strong cytokine activity induced by the virus . The overreaction of the immune system in the form of a cytokine storm causes defense cells to attack the lung tissue. Since the group of 20 to 40 year olds has a particularly active immune system, the development of the cytokine storm is particularly strong here. The cytokine storm would be a parallel to the Covid-19 disease, which was just as easily transmissible, but in February 2020 was rated a level lower in clinical severity than the Spanish flu. In the meantime, a possible equivalence is also assumed in terms of clinical severity. With Covid-19, however, in contrast to the Spanish flu, there has been no decrease in mortality in older age groups, but a significant increase.

Reconstruction and analysis of the virus's RNA sequence

In 1951 , Johan Hultin , who was then a doctoral student and who later worked as a pathologist , exhumed tissue samples from a mass grave of flu victims in the permafrost of Alaska , but was unable to detect any influenza viruses. In 1997, he obtained permission from the community on the Seward Peninsula to exhumate again. Lung tissue samples were taken from four of the dead, and fragments of the influenza virus genes were isolated from one of them . Finally, the entire genome of the Spanish flu pathogen was sequenced . In 1996 and 1997, the same research group at the Institute for Pathology of the US Armed Forces in Rockville , under the direction of Jeffery Taubenberger, isolated parts of the influenza virus from various tissue samples that were stored by the US Army from the First World War.

In 2003, Reid et al. confirmed that the virus belonged to the influenza A viruses . In 2004, Gamblin et al. demonstrated how the Spanish flu virus binds to human cells by structural analysis of hemagglutinin H1 .

In October 2005, American scientists working with Jeffery Taubenberger reported that they had reconstructed the virus from 1918 in a high-security CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) laboratory in Atlanta. Taubenberger and his team have been publishing their research, which they began in 1995, in a series of articles since 1997, which were summarized in 2005 with the publication of the complete gene sequence in the journals Science and Nature .

Based on their analyzes, the researchers concluded that the RNA polymerase of the human influenza virus was derived directly from an avian influenza virus and that the transition to humans probably took place just before the pandemic began. Due to the great similarity with known variants of avian influenza , they are also of the opinion that the virus has achieved its dangerousness as a result of fewer mutations and not through an exchange of genetic makeup with previously existing variants of human influenza, i.e. H. not by reassorting (see also antigen shift in influenza viruses ).

In animal experiments , the reconstructed virus (as was to be expected due to the high death rate from the 1918 epidemic) proved to be extremely aggressive: It killed mice faster than any other known human influenza virus and - in contrast to most human influenza viruses - was Viruses - also deadly for chicken embryos. In contrast to other experiments with mice, the reconstructed virus did not first have to be adapted to mice. This shows that the proteins contain hemagglutinin, as well as possibly the neuraminidase of the virus, contain virulence factors for mice. Its polymerase genes were similar to those of A / H5N1 and other avian influenza viruses. It also proved to be extremely prone to multiplying in epithelial cells from human bronchi , which would lead to pneumonia in the functioning organ. In addition, unlike the influenza viruses circulating today, it is able to multiply without trypsin , which requires a previously unknown mechanism of neuraminidase that simplifies the cleavage of hemagglutinin.

So far, the active virus had only been made available to one scientist at the CDC. Since the end of October 2005, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been sending the Spanish flu virus to all interested biological protection level 3 laboratories .

In 2007, researchers at St. Jude Children's Hospital, Memphis (Tennessee) , discovered that a viral protein only 90 amino acids in size called PB1- F2 appears to be responsible for the unusually high mortality rate .

Since the publication of the results of the research by Taubenberger and his colleagues in 2005, virologists have been warning of a new pandemic which, due to the much higher spatial mobility compared to 1918/20 , could exceed the Spanish flu many times over.

Prominent victims

Among the victims of the Spanish flu were Egon Schiele and his wife Edith, Max Weber and Frederick Trump , the grandfather of Donald Trump , and Mehmed V , Sultan and thus head of state of the Ottoman Empire . The 1918 largely dormant tuberculosis of Franz Kafka may have been given by the Spanish flu, the deadly turn.

The illnesses of President Woodrow Wilson and his advisor Edward Mandell House during the deliberations on the Peace Treaty of Versailles , as Wilson, unlike representatives of other victorious powers, was concerned with a compromise, as well as that of Max von Baden, had effects on the political and historical events , the last Chancellor of the German Empire , which led to a delay in important political decisions in a particularly critical phase.

monument

In October 2019, the first monument erected in Germany to commemorate the Spanish flu was unveiled in Wiesloch ( Baden-Württemberg ). The focus is on the old tombstone of the victim Anna Katharina Ritzhaupt, who died in 1918 at the age of 24.

Trivia

The speed at which the Spanish flu spread was reflected in the nursery rhyme "A bird named Enza":

- English original:

- I had a little bird

- Its name was Enza.

- I opened the window,

- And in-flu-enza.

- Translation:

- I had a little bird

- his name was Enza.

- I opened a window

- and Enza flew in.

See also

Movies

- In 1990, in the film Zeit des Erwachens (Original: Awakenings ) with Robert De Niro and Robin Williams , the suspected connection between Spanish flu and encephalitis lethargica was thematized on the basis of the book of the same name by Oliver Sacks . The background to the film was the short-term therapeutic success in the early 1970s against the suspected neurological late effects of the pandemic in some patients after the use of levodopa .

- Hidden world catastrophe - The Spanish flu 100 years ago. Report, 8:45 min., BR television, 2018 ( online ).

- Spanish Flu - The Secret of the Killer Virus. Documentary, 45 min., Production: BBC Studios, ZDFinfo, 2019 ( online ).

literature

- Monographs

- John M. Barry: The Great Influenza. The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History. Penguin Books, New York 2004, ISBN 0-670-89473-7 (English).

- Alfred W. Crosby: America's Forgotten Pandemic. The Influenza of 1918. 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, ISBN 978-0-521-54175-6 (English).

- Pete Davies: Catching Cold - The Hunt for a Killer Virus. Penguin Books, London 1999, ISBN 0-14-027627-0 (English).

- Marc Hieronimus: Illness and Death 1918. To deal with the Spanish flu in France, England and in the German Empire. Lit, Münster 2006, ISBN 978-3-8258-9988-2 .

- Niall Johnson: Britain and the 1918-19 Influenza Pandemic, A Dark Epilogue. Routledge, London / New York 2006, ISBN 0-415-36560-0 (English).

- Gina Bari Kolata: Influenza. The hunt for the virus (= Fischer. 15385). Fischer Taschenbuchverlag, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-596-15385-9 .

- David Rengeling: From patient perseverance to comprehensive prevention. Flu pandemics as reflected in science, politics and the public . Nomos, Baden-Baden 2017, ISBN 978-3-8487-4341-4 . ( doi : 10.5771 / 9783845285658 ).

- Harald Salfellner: The Spanish flu. A history of the 1918 pandemic. Vitalis, Prague 2018, ISBN 978-3-89919-510-1 . - New edition supplemented with regard to Covid-19: Vitalis, Prague 2020, ISBN 978-3-89919-794-5 .

- Franz Schausberger : Similar and yet completely different. Spanish flu 100 years ago and Corona today . Short historical-political studies. Volume 2. pm publisher. Salzburg 2020, ISBN 978-3-902557-21-6 .

- Laura Spinney: 1918 - The world in fever. How the Spanish flu changed society. Hanser, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-446-25848-8 .

- Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War. Primus, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 .

- Stefan Winkle: Cultural history of epidemics. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf 1997, ISBN 3-933366-54-2 , p. 1045 ff.

- Wilfried Witte: Need to explain. The flu epidemic 1918–1920 in Germany with special attention to Baden. Centaurus, Herbolzheim 2006, ISBN 3-8255-0641-X .

- Wilfried Witte: Belladonna and quarantine. The history of the Spanish flu. Wagenbach, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-8031-2633-7 .

- items

- Matthias Kordes: The Spanish flu of 1918 and the end of the First World War in Recklinghausen. In: Vestische Zeitschrift. Volume 101, No. 07, 2006, ISSN 0344-1482 , pp. 119-126.

- Eckard Michels : The "Spanish Flu" 1918/19. Course, consequences and interpretations in Germany in the context of the First World War. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , Volume 58, No. 1, 2010, pp. 1–33 ( PDF ).

- Howard Phillips, David Killingray (Eds.): The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918-19. New Perspectives. In: Routledge Studies in the Social History of Medicine. Volume 12. London / New York 2003, ISBN 0-415-23445-X (English).

- Ann H. Reid, Thomas A. Janczewski, Raina M. Lourens et al .: 1918 Influenza Pandemic Caused by Highly Conserved Viruses with Two Receptor-Binding Variants. In: Emerging Infectious Diseases. Volume 9, No. 10, 2003, ISSN 1080-6040 , doi: 10.3201 / eid0910.020789 (English).

- Dieter Simon: The "Spanish flu" pandemic of 1918/19 in the northern Emsland and some surrounding regions. In: Emsland history. No. 13. Study Society for Emsland Regional History , Haselünne 2006, ISSN 0947-8582 , pp. 106–145.

- Guido Steinberg: The Commemoration of the "Spanish Flu" of 1918-1919 in the Arab East. In: Olaf Farschid, Manfred Kropp, Stephan Dähne (eds.): The First World War as Remembered in the Countries of the Eastern Mediterranean (= Beirut texts and studies. Volume 99). Beirut 2006, ISBN 3-89913-514-8 , pp. 151-162 (English).

- Jeffery K. Taubenberger et al .: Initial Genetic Characterization of the 1918 “Spanish” Influenza Virus. In: Science . Volume 275, No. 5307, 1997, ISSN 0036-8075 , pp. 1793-1796, doi: 10.1126 / science.275.5307.1793 (English).

- Jefferey K. Taubenberger et al .: Characterization of the 1918 influenza virus polymerase genes. In: Nature . Volume 437, 2005, ISSN 0028-0836 , pp. 889-893, doi: 10.1038 / nature04230 (English).

- Jeffery Taubenberger , Ann H. Reid, Thomas G. Fanning: The Spanish Flu Killer Virus. In: Spektrum der Wissenschaft , No. 4, 2005, ISSN 0170-2971 , pp. 52-60.

- Jefferey K. Taubenberger, David M. Morens: 1918 Influenza, the Mother of All Pandemics. In: Emerging Infectious Diseases . Volume 12, No. 1, 2006, pp. 15-22, ISSN 1080-6040 ( PDF , English).

- Terrence M. Tumpey et al .: Characterization of the Reconstructed 1918 Spanish Influenza Pandemic Virus. In: Science. Volume 310, No. 5745, 2005, ISSN 0036-8075 , pp. 77-80, doi: 10.1126 / science.1119392 (English).

- Wilfried Witte: The flu pandemic 1918–1920 in the medical debate. In: Reports on the history of science . Volume 29, No. 1, 2006, ISSN 0170-6233 , pp. 5-20. ( doi : 10.1002 / bewi.200501184 ).

- Wilfried Witte: The virus and the dead - access routes to the history of the Spanish flu , in: Swiss Medical Journal / Bulletin des médecins suisses / Bolletino dei medici svizzeri . No. 91 (21), 2010, pp. 827-829. ( PDF ).

- Michael Worobey, Jim Cox, Douglas Gill: The origins of the great pandemic . In: Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health , Vol. 2019, Issue 1, pp. 18-25.

- Deaths in Switzerland at record levels. The Spanish flu of 1918. Federal Statistical Office , November 22, 2018 ( PDF ).

Web links

- Deutschlandfunk : Worse than Corona - The Spanish flu (audio). Broadcast on April 9, 2020.

- 1918 Pandemic (H1N1 virus) , Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . (Accessed: March 29, 2020).

- Worst pandemic influenza in history . In: BR.de , March 5, 2018.

- Michael Lange : The mysterious Spanish flu . In: Deutschlandfunk.de , March 4, 2018.

- Sven Felix Kellerhoff : "The worst epidemic that has ever swept the earth" . In: Welt.de , February 1, 2020.

- Franz Metzger: Attack of the killer viruses - The Spanish flu . In: G-Geschichte.de ( G / Geschichte 11/2018).

- Ulrike Abel-Wanek: The almost forgotten pandemic . Pharmaceutical newspaper of September 27, 2018 (accessed: March 23, 2020).

Individual evidence

-

↑ WHO (Ed.): Pandemic Influenza Risk Management. World Health Organization, Geneva 2017, p. 26, full text .

Niall PAS Johnson, Jürgen Müller: Updating the Accounts: Global Mortality of the 1918-1920 "Spanish" Influenza Pandemic . In: Bulletin of the History of Medicine 76, 2002, pp. 105-115. -

^ Jefferey K. Taubenberger, David M. Morens: 1918 Influenza, the Mother of All Pandemics. In: Emerging Infectious Diseases . Volume 12, No. 1, 2006, pp. 15-22, ISSN 1080-6040 ( PDF , English). (Accessed: March 29, 2020).

Niall PAS Johnson, Jürgen Müller: Updating the Accounts: Global Mortality of the 1918-1920 "Spanish" Influenza Pandemic . In: Bulletin of the History of Medicine 76, 2002, p. 114 f. (Accessed: June 9, 2020) - ↑ 1918 Pandemic (H1N1 virus) , Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), March 20, 2019.

- ^ Niall PAS Johnson, Juergen D. Mueller: Updating the Accounts: Global Mortality of the 1918-1920 "Spanish" Influenza Pandemic . In: Bulletin of the History of Medicine. Volume 76, No. 1, 2002, pp. 105-115.

-

↑ Laura Spinney: 1918 - The world in fever. How the Spanish flu changed society. Hanser, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-446-25848-8 , p. 236.

Jefferey K. Taubenberger, David M. Morens: 1918 Influenza, the Mother of All Pandemics. In: Emerging Infectious Diseases . Volume 12, No. 1, 2006, pp. 15-22, ISSN 1080-6040 ( PDF , English). (Accessed: April 16, 2020) -

↑ Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , p. 31.

Wilfried Witte: Belladonna and Quarantine. The history of the Spanish flu . Klaus Wagenbach Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8031-3628-2 , p. 8.

Beatriz Echeverri: Spanish influenza seen from Spain . In: Howard Phillips, David Killingray (Eds.): The Spanish Influenza Pandemic 1918-19. New Perspectives, London / New York 2003. pp. 173-190. -

↑ Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , p. 31.

Wilfried Witte: Belladonna and Quarantine. The history of the Spanish flu . Klaus Wagenbach Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8031-3628-2 , p. 8.

Laura Spinney: 1918 - The world in fever. How the Spanish flu changed society. Hanser, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-446-25848-8 , p. 77 f. -

↑ Laura Spinney: 1918 - The world in fever. How the Spanish flu changed society. Hanser, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-446-25848-8 , p. 77 f.

Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , p. 31. - ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Daniel Bax: Pandemic - World in Fever. Friday, March 26th, 2020, accessed on April 7th, 2020 .

- ↑ Nils Köhler: When epidemic death came to Baden. In: " Südkurier ", March 7, 2020, p. 15.

- ^ Franz Schausberger : Similar and yet completely different. Spanish flu 100 years ago and Corona today . Short historical-political studies. Volume 2. pm publisher. Salzburg 2020, ISBN 978-3-902557-21-6 , p. 18 ff.

- ↑ Laura Spinney: 1918 - The world in fever. How the Spanish flu changed society. Hanser, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-446-25848-8 , p. 77.

-

↑ Laura Spinney: 1918 - The world in fever. How the Spanish flu changed society. Hanser, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-446-25848-8 , p. 181 ff.

M. Humphries: Paths of infection: the First World War and the origins of the 1918 influenza pandemic . In: War in History , 2013, 21 (I), pp. 55–81.

Gerhard Hirschfeld , Gerd Krumeich, Irina Renz in connection with Markus Pöhlmann (Ed.): Encyclopedia First World War. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2014, ISBN 978-3-8252-8551-7 , p. 414.

Nord-Pas de Calais region: The Chinese workers in Nord-Pas de Calais during the First World War . (Accessed: July 14, 2020). -

↑ Laura Spinney: 1918 - The world in fever. How the Spanish flu changed society. Hanser, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-446-25848-8 , p. 189 ff.

John S. Oxford et al .: World War I may have allowed the emergnence of "Spanish" influenza . In: Lancet Infectious Diseases , February 2002, No. 2, pp. 111-114.

AB Hammond, W. Rolland, THG Shore: Purulent bronchitis: a study of cases occur among the British troops at a base in France . In: Lancet , 1917, No. 193, pp. 377-380. -

↑ John M. Barry: The site of origin of the 1918 influenza pandemic and its public health implications . In: Journal of Translational Medicine , Vol. 2, Issue 1, January 2004.

FM Burnet and Ellen Clark: Influenza; a survey of the last 50 years in the light of modern work on the virus of epidemic influenza. Macmillan, Melbourne 1942. - ^ Alfred W. Crosby: America's Forgotten Pandemic. The Influenza of 1918. 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, ISBN 978-0-521-54175-6 .

-

↑ Laura Spinney: 1918 - The world in fever. How the Spanish flu changed society. Hanser, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-446-25848-8 , p. 234 f.

Harald Salfellner: The Spanish flu. A history of the 1918 pandemic . Vitalis, Prague 2020, ISBN 978-3-89919-794-5 , p. 41 ff.

Michael Worobey, Jim Cox, Douglas Gill: The origins of the great pandemic . In: Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health . Vol. 2019, issue 1, pp. 18-25.

Michael Worobey et al .: Genesis and pathogenesis of the 1918 pandemic H1N1. In: PNAS . Volume 111, No. 22, 2014, pp. 8107–8112, doi: 10.1073 / pnas.1324197111

F. Haalboom: "Spanish" flu and army horses: what historians and biologists can learn from a historiy of animals with flu during the 1918 -1919 influenza pandemic . In: Studium , 2014, 7 (3), pp. 124–139. -

↑ Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , pp. 31 f., 39 f.

Wilfried Witte: Belladonna and quarantine. The history of the Spanish flu . Klaus Wagenbach Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8031-3628-2 , p. 36 ff. - ↑ Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , p. 39 f.

- ↑ Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , p. 36.

- ↑ Harald Salfellner: The Spanish flu. A history of the 1918 pandemic . Vitalis, Prague 2020, ISBN 978-3-89919-794-5 , p. 175.

- ↑ Wilfried Witte: Belladonna and Quarantine. The history of the Spanish flu . Klaus Wagenbach Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8031-3628-2 , pp. 54 ff., 68 f.

-

↑ Sherman McCall, James M. Henry, Ann H. Reid, Jeffery K. Taubenberger: Influenza RNA not Detected in Archival Brain Tissues from Acute Encephalitis Lethargica Cases or in postencephalitic parkinson Cases . In: Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology . tape 60 , no. 7 , July 1, 2001, ISSN 0022-3069 , p. 696–704 , doi : 10.1093 / jnen / 60.7.696 ( oup.com [accessed March 12, 2020]). KC Lo, JF Geddes, RS Daniels, JS Oxford: Lack of detection of influenza genes in archived formalin-fixed, paraffin wax-embedded brain samples of encephalitis lethargica patients from 1916 to 1920. In: Virchows Archiv . tape

442 , no. 6 , June 1, 2003, ISSN 1432-2307 , p. 591–596 , doi : 10.1007 / s00428-003-0795-1 ( springer.com [accessed March 12, 2020]). -

↑ WHO (Ed.): Pandemic Influenza Risk Management. World Health Organization, Geneva 2017, p. 26, full text

Niall PAS Johnson, Jürgen Müller: Updating the Accounts: Global Mortality of the 1918-1920 "Spanish" Influenza Pandemic . In: Bulletin of the History of Medicine 76, 2002, pp. 105-115. (Accessed: June 9, 2020) -

^ Jefferey K. Taubenberger, David M. Morens: 1918 Influenza, the Mother of All Pandemics. In: Emerging Infectious Diseases . Volume 12, No. 1, 2006, pp. 15-22, ISSN 1080-6040 ( PDF , English). (Accessed: March 29, 2020).

Niall PAS Johnson, Jürgen Müller: Updating the Accounts: Global Mortality of the 1918-1920 "Spanish" Influenza Pandemic . In: Bulletin of the History of Medicine 76, 2002, p. 114 f. (Accessed: June 9, 2020). -

↑ Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , S, 30, 130 ff.

Jörn Leonhard: The Pandora's box. History of the First World War. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66191-4 , p. 921. -

↑ Wilfried Witte: Belladonna and Quarantine. The history of the Spanish flu . Klaus Wagenbach Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8031-3628-2 , p. 22.

Alfred W. Crosby: America's Forgotten Pandemic. The Influenza of 1918 . Cambridge, New York, Cambridge University Press 2003, p. 206.

Wilfried Witte: Explanatory note. The flu epidemic 1918–1920 in Germany with special emphasis on Baden. Herbolzheim, Centaurus 2006, p. 292. - ^ Jefferey K. Taubenberger, David M. Morens: 1918 Influenza, the Mother of All Pandemics. In: Emerging Infectious Diseases . Volume 12, No. 1, 2006, pp. 15-22, ISSN 1080-6040 ( PDF , English).

- ^ Jefferey K. Taubenberger, David M. Morens: 1918 Influenza, the Mother of All Pandemics. In: Emerging Infectious Diseases . Volume 12, No. 1, 2006, pp. 15-22, ISSN 1080-6040 ( PDF , English).

- ↑ Christina Mills, James Robins, Marc Lipsitch, Transmissibility of 1918 pandemic influenza, Nature, Volume 432, 2004, pp. 904-906, here p. 905. PMID 15602562

-

↑ Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , p. 25 ff.

Wilfried Witte: Belladonna and Quarantine. The history of the Spanish flu . Klaus Wagenbach Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8031-3628-2 , p. 7. - ^ Influenza: Haskell, Kansas . In: Public Health Reports , Edition 33, No. 14, April 5, 1918, p. 502, cited in the translation by Harald Salfellner: Die Spanische Flu. A history of the 1918 pandemic . Vitalis, Prague 2020, ISBN 978-3-89919-794-5 , p. 47.

- ^ Paul McCusker, Walt Larimore: The Influenza Bomb. ISBN 1-4165-6975-8 p. 1 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Marc Tribelhorn: The Spanish flu raged 100 years ago. To this day it remains a mystery In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung from March 16, 2018.

- ↑ Martin Winkelheide: 100 years ago - First cases of the Spanish flu reported. In: deutschlandfunk.de. March 11, 2018, accessed March 29, 2020 .

- ^ Sascha Karberg: Influenza Pandemic 1918: The Virus That Changed the World. In: tagesspiegel.de . March 1, 2018, accessed March 29, 2020 .

- ↑ Spanish flu: disease wiped out 100 million - and still nobody knows the cause. Focus Online , May 4, 2018, accessed March 24, 2020 .

- ↑ Laura Spinney: 1918 - The world in fever. How the Spanish flu changed society. Hanser, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-446-25848-8 , p. 194.

- ↑ Harald Salfellner: The Spanish flu. A history of the 1918 pandemic . Vitalis, Prague 2020, ISBN 978-3-89919-794-5 , p. 50.

- ↑ Hans Michael Kloth: Influenza catastrophe of 1918/19: "Take all carpenters and have coffins made". In: Spiegel.de . April 27, 2009, accessed February 4, 2020 .

-

↑ Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , p. 28 ff.

Harald Salfellner: The Spanish flu. A history of the 1918 pandemic . Vitalis, Prague 2020, ISBN 978-3-89919-794-5 , p. 47 ff. - ↑ Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , pp. 30, 48, 130 ff.

-

↑ Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , p. 30.

Wilfried Witte: Belladonna and Quarantine. The history of the Spanish flu . Klaus Wagenbach Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8031-3628-2 , p. 7. - ^ Notes from a doctor . In: Neues Wiener Tagblatt . May 29, 1918, p. 9 ( ANNO - AustriaN Newspapers Online [accessed April 20, 2020]).

- ↑ Deaths in the American Army . In: Neues Wiener Tagblatt . June 4, 1918, p. 5 ( ANNO - AustriaN Newspapers Online [accessed April 20, 2020]).

- ↑ Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , p. 59 ff.

- ↑ Wilfried Witte: Belladonna and Quarantine. The history of the Spanish flu . Klaus Wagenbach Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8031-3628-2 , p. 10.

-

↑ John Keegan: The First World War. A European tragedy. Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek 2001, ISBN 3-499-61194-5 , p. 566.

David Stevenson: 1914-1918. The First World War. Translated from the English by Harald Ehrhardt and Ursula Vones-Leibenstein. Patmos Verlag, Düsseldorf 2010, ISBN 978-3-491-96274-3 , p. 588.

Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , pp. 46, 58 f., 98.

Alfred Stenger: turning point. From Marne to Vesle 1918. (Battles of the World War. Edited and edited in individual representations on behalf of the Reichsarchiv. Volume 35), Gerhard Stalling Verlag, Oldenburg iO / Berlin 1930, p. 223.

Gerhard Hirschfeld , Gerd Krumeich, Irina Renz in connection with Markus Pöhlmann (Ed.): Encyclopedia First World War. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2014, ISBN 978-3-8252-8551-7 , p. 460.

Jörn Leonhard : The Pandora's box. History of the First World War. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66191-4 , p. 845. - ↑ Harald Salfellner: The Spanish flu. A history of the 1918 pandemic . Vitalis, Prague 2020, ISBN 978-3-89919-794-5 , p. 55.

- ↑ Blame U-Boats for Epidemic . In: Evening Public Ledger , May 30, 1918.

-

↑ Monica Schoch-Spana: Implications of Pandemic Influenza for Bioterrorism Response. In: Clinical Infectious Diseases . Volume 31, No. 6, 2000, pp. 1409-1413, doi: 10.1086 / 317493 , full text .

James F. Armstrong: Philadelphia, Nurses, and the Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918. In: Navy Medicine. Volume 92, No. 2, 2001, pp. 16-20, full text - ↑ Laura Spinney: 1918 - The world in fever. How the Spanish flu changed society. Hanser, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-446-25848-8 , p. 228 f.

- ↑ Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , p. 62.

-

↑ Wilfried Witte: Belladonna and Quarantine. The history of the Spanish flu . Klaus Wagenbach Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8031-3628-2 , p. 11.

Howard Phillips, David Killingray: Introduction . In: Howard Phillips, David Killingray (Eds.): The Spanish Influenza Pandemic 1918-19. New Perspectives, London / New York 2003. P. 6 f.

Louis Martin: L'épidémie de grippe de Brest . In: La Presse Médicale of October 24, 1918, p. 698. Summary in: Bulletin Mensuel / Office International d´Hygiène Publique 11, 1919, p. 77. - ↑ Laura Spinney: 1918 - The world in fever. How the Spanish flu changed society. Hanser, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-446-25848-8 , p. 52.

- Jump up ↑ Howard Markel, Harvey Lipman, J. Alexander Navarro, Alexandra Sloan, Joseph Michalsen, Alexandra Stern, Martin Cetron: Nonpharmaceutical Interventions Implemented by US Cities During the 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic , Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), Volume 298 , 2007, pp. 644-654

- ↑ a b [ https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/2020/03/how-cities-flattened-curve-1918-spanish-flu-pandemic-coronavirus/ Nina Strochlic, Riley Champine: How some cities' flattened the curve 'during the 1918 flu pandemic , National Geographic, March 27, 2020

- ↑ Richard J. Hatchett, Carter E. Mecher, Marc Lipsitch: Public health interventions and epidemic intensity during the 1918 influenza pandemic , Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA, Vol. 104, 2007, pp. 7582-7587

- ↑ Annette Großbongardt, Julia Amalia Heyer, Lydia Rosenfelder: Vergehnisvolle Dynamics, Spiegel No. 25, June 20, 2020, pp. 17–19, with regard to the recommendations of the virologist Christian Drosten to the political leadership based on the study in JAMA from 2007 based.

- ↑ Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , p. 62 ff.

- ^ Christian Sonderegger: Influenza. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . December 21, 2017 , accessed March 29, 2020 .

- ↑ Patrick Imhasly: The Spanish flu - a forgotten catastrophe In: NZZ on Sunday 6 January 2018.

-

↑ Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , pp. 84, 108 ff.

Wilfried Witte: Belladonna and Quarantine. The history of the Spanish flu . Klaus Wagenbach Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8031-3628-2 , p. 18 ff. - ^ Geoffrey Rice: Black November. The 1918 Influenza Epidemic in New Zealand. Allen & Unwin, Wellington 1988.

-

↑ Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , p. 104 ff.

Wilfried Witte: Belladonna and Quarantine. The history of the Spanish flu . Klaus Wagenbach Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8031-3628-2 , p. 19 f. -

↑ Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , pp. 114 f., 117 ff.

Wilfried Witte: Belladonna and Quarantine. The history of the Spanish flu . Klaus Wagenbach Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8031-3628-2 , p. 16 f. - ↑ Pete Davies: Catching Cold - The Hunt for a Killer Virus. Penguin Books, London 1999, ISBN 0-14-027627-0 .

-

↑ Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , p. 136.

Wilfried Witte: Belladonna and Quarantine. The history of the Spanish flu . Klaus Wagenbach Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8031-3628-2 , p. 22. - ↑ a b c Secrets of Science. Part 2: The Great Epidemic. Documentary series, France 2005, ARTE F, directed by Stéphane Bégoin

- ↑ quoted from Influenza 1918 in the United States at pbs.org. ( Memento of February 4, 2005 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Pete Davies: Catching Cold - The Hunt for a Killer Virus. Penguin Books, London 1999, ISBN 0-14-027627-0 , p. 115.

-

↑ Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , p. 65.

Wilfried Witte: Belladonna and Quarantine. The history of the Spanish flu . Klaus Wagenbach Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8031-3628-2 , p. 17 f. -

↑ Laura Spinney: 1918 - The world in fever. How the Spanish flu changed society. Hanser, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-446-25848-8 , p. 242 f.

MCJ Bootsma, NM Ferguson: The effect of public health measures on the 1918 influenza pandemic in US cities. In: Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, May 1, 2007, 104 (18), pp. 7588-7593. -

↑ Harald Salfellner: The Spanish flu. A history of the 1918 pandemic . Vitalis, Prague 2018, ISBN 978-3-89919-510-1 , p. 78 ff . Manfred Vasold: The Spanish flu. The plague and the First World War . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-394-3 , p. 41 ff.

- ^ Jefferey K. Taubenberger, David M. Morens: 1918 Influenza, the Mother of All Pandemics. In: Emerging Infectious Diseases . Volume 12, No. 1, 2006, pp. 15-22, ISSN 1080-6040 ( PDF , English).

- ^ Jefferey K. Taubenberger, David M. Morens: 1918 Influenza, the Mother of All Pandemics. In: Emerging Infectious Diseases . Volume 12, No. 1, 2006, pp. 15-22, ISSN 1080-6040 ( PDF , English).

- ↑ Laura Spinney: 1918 - The world in fever. How the Spanish flu changed society. Hanser, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-446-25848-8 , p. 231.

- ↑ Influenza: Are We Prepared for a Pandemic? In: Spectrum of Science , January 2006, p. 72 ff.

- ↑ P. Mehta, DF McAuley et al. a .: COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. (PDF). In: The Lancet , issue 395, March 28, 2020.

- ↑ Mike Famulare: 2019-nCoV: preliminary estimates of the confirmed-case-fatality-ratio and infection-fatality-ratio, and initial pandemic risk assessment . Institute for Disease Modeling.

- ↑ On further parallels and differences between Covid-19 and Spanish flu: Harald Salfellner: The Spanish flu. A history of the 1918 pandemic . Vitalis, Prague 2020, ISBN 978-3-89919-794-5 , pp. 170 ff.

- ↑ See e.g. B. Fei Zhou et al. : Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. In: The Lancet , March 11, 2020, doi: 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (20) 30566-3

- ↑ Wilfried Witte: Belladonna and Quarantine. The history of the Spanish flu . Klaus Wagenbach Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8031-3628-2 , p. 87.

- ↑ Ann H. Reid et al .: 1918 Influenza Pandemic and Highly Conserved Viruses with Two Receptor-Binding Variants. In: Emerging Infectious Diseases. [serial online]. October 2003, doi: 10.3201 / eid0910.020789 , full text .

- ↑ SJ Gamblin et al .: The structure and receptor binding properties of the 1918 influenza hemagglutinin. In: Science . Volume 303, No. 5665, 2004, pp. 1838–1842, doi: 10.1126 / science.1093155 .

-

↑ Jeffery K. Taubenberger, Ann H. Reid, Amy E. Krafft, Karen E. Bijwaard, Thomas G. Fanning: Initial Genetic Characterization of the 1918 'Spanish' Influenza Virus. In: Science , Volume 275, 1997, pp. 1793-1796

Ann H. Reid et al .: Origin and evolution of the 1918 “Spanish” influenza virus hemagglutinin gene. In: PNAS . Volume 96, No. 4, 1999, pp. 1651-1656, doi: 10.1073 / pnas.96.4.1651

Ann H. Reid et al .: Characterization of the 1918 “Spanish” influenza virus neuraminidase gene. In: PNAS. Volume 97, No. 12, 2000, pp. 6785-6790, doi: 10.1073 / pnas.100140097

Christopher F. Basler et al .: Sequence of the 1918 pandemic influenza virus nonstructural gene (NS) segment and characterization of recombinant viruses bearing the 1918 NS recover. In: PNAS. Volume 98, No. 5, 2001, pp. 2746-2751, doi: 10.1073 / pnas.031575198