Edvard Munch

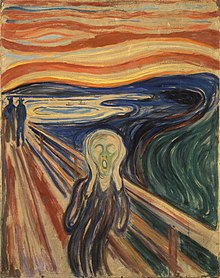

Edvard Munch [ ɛdvɒ: rt muŋk ] (born December 12, 1863 in Løten , Hedmark , Norway ; † January 23, 1944 at Ekely in Oslo ) was a Norwegian painter and graphic artist of symbolism . In addition to over 1700 paintings , he made numerous graphics and drawings . Munch is considered a pioneer for the expressionist direction in modern painting . His first exhibition in Germany caused a scandal (" Fall Munch "). As a result, he enjoyed the reputation of an epoch-making new creator early on in Germany and the rest of Central Europe. Today its character and status are recognized in the rest of Europe and the world. The best known are Munch's works from the 1890s, which he summarized in the so-called frieze of life , including The Scream , which, like many of Munch's motifs, exists in several versions.

Life

origin

Edvard Munch grew up in the Norwegian capital Oslo , which at that time was called Christiania (from 1877 Kristiania ). His father Christian Munch was a deeply religious military doctor with a modest income. The historian Peter Andreas Munch was Edvard Munch's uncle.

Munch's father Christian married Laura Catherine Bjølstad, a businessman's daughter who was 20 years his junior, when he was 44. The young wife gave birth to her son Edvard at the age of 27 and died of tuberculosis at 33 when Edvard was five years old. Edvard himself was in poor health, but it was not he, but his older sister Sophie who was the next victim of consumption . His younger sister Laura was under medical treatment for "melancholy" (today depression ). Posthumously, doctors also hypothesized a borderline personality disorder (emotionally unstable personality) with regard to Edvard Munch , partly in connection with a bipolar disorder (manic-depressive illness). Of the five siblings, only his brother Andreas married, but died a few months after the wedding.

The parental home was culturally stimulating - however, it is the impressions of illness, death and grief that Munch mainly returns to in his art.

realism

At his father's request, Munch went through a year of technical school and then, with the support of his aunt Karen, turned to art with great seriousness. He studied the old masters , followed life drawing lessons at the royal drawing school and for a time received corrections from Norway's leading naturalist , Christian Krohg . His early work was characterized by a French-inspired realism , and he was soon noticed as a great talent .

In 1885 Munch was in Paris during a short study visit . In the same year he began work on his crucial work The Sick Child . Here he breaks radically with realism, as we see it in Christian Krohg in a corresponding motif (in the National Gallery in Oslo ). Munch worked on the painting for a long time - searching for the first impression and a valid painterly expression for a painful personal experience. With this picture he tried to process Sophie's death. He renounced space and plastic form and advanced on an iconic composition formula. The coarse materiality of the surface showed all traces of a laborious creative process. The criticism was very negative. Nevertheless, Munch took up this motif again and again throughout his life.

The main works of the following years are less provocative in form . Inger am Strand from 1889 testifies to Munch's ability to depict lyrical moods in harmony with the neo-romantic tendencies of that time . He painted this picture in Åsgårdstrand , a small coastal town near Horten . We find the winding coastline , which is so characteristic of this area, as a meaningful leitmotif in many of Munch's compositions.

Kristiania-Bohème

In 1889 Munch also painted a portrait of the head of Kristiania's bohemians , Hans Jæger . Munch's dealings with Jæger and his circle of radical anarchists in the second half of the 1880s became a crucial turning point in his life and a source of internal ferment and conflict . At this time began his extensive biographical - literary production, which he took up again and again in different phases of his life. These early records acted as a " reference work " to several of the central motifs from the 1890s. In keeping with Jæger's ideas, he wanted to convey true “close-ups” of the longings and torments of modern life - he wanted to “paint his life”.

France

In the autumn of 1889 Munch had a large solo exhibition in Christiania, after which the State him for three consecutive years an artist fellowship grant. Paris was the natural destination, where he was for a short time - together with his friend Kalle Løchen - a student of Léon Bonnat . But he received the more important impulses by orienting himself towards the artistic life of the city. A post-impressionist breakthrough with various anti- naturalistic experiments took place here at that time . That had a liberating effect on Munch. "The camera can not compete with brush and palette ," he wrote, "as long as it cannot be used in heaven and hell".

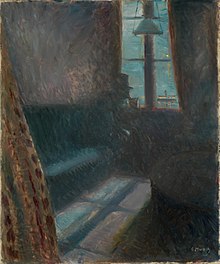

Shortly after Munch came to France that first autumn, he received news of his father's death. The loneliness and melancholy in his painting Night in Saint-Cloud (1890) are often seen against this background. The dark interior with the lonely figure at the window is completely dominated by shades of blue - a Valeurmalerei that of James McNeill Whistler's nocturnal color chords may remember. This modern and independent work is also an expression of the “ decadence ” in the last decade of the 19th century.

At the autumn exhibition in Christiania in 1891, Munch showed melancholy, among other things . Large, curved lines and more homogeneous areas of color dominate here - a simplification and stylization of the motif related to Paul Gauguin and French synthetists . " Symbolism - nature is shaped by a mood," writes Munch.

At this time he made the first sketches for his most famous work The Scream . He also painted a number of pictures in an impressionist and approximately pointillist style, with motifs of the Seine , Parisian streets and the parade street of Christianias Karl Johans Gate . However, Munch's main interest were the impressions of the soul and not those of the eye.

Spring on Karl Johans gate (1890)

Rue Lafayette (1891)

Melancholy (1892)

The Scream (1893)

Germany

In the fall of 1892, Munch presented the results of his stays in France in Christiania. The Norwegian landscape painter Adelsteen Normann saw this exhibition and helped the then unknown Munch to get an invitation from the Berlin Art Association . Munch's first exhibition in Berlin took place in the “Architektenhaus” at Wilhelmstrasse 92. It was opened with 55 pictures on November 5, 1892 and ended with a gruesome "succès de scandal". The public and the older painters took Munch's pictures as anarchist provocation, and the exhibition was closed in protest on November 12, 1892 at the instigation of Anton von Werner , director of the Royal University of Fine Arts .

As a result, Munch's name suddenly became known in Berlin and he decided to stay in the city. He came into a circle of writers , artists and intellectuals in which Scandinavians were strongly represented. The group included the Swedish playwright August Strindberg , the Polish poet Stanisław Przybyszewski , the Norwegian sculptor Gustav Vigeland , the Danish writer Holger Drachmann and the German art historian Julius Meier-Graefe . They met in the Gasthaus Zum schwarzen Ferkel Unter den Linden / corner of Neue Wilhelmstrasse. Here Friedrich Nietzsche's philosophy as well as occultism , psychology and the dark side of sexuality were discussed .

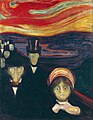

In December 1893, Munch exhibited on Unter den Linden. Here he showed, among other things, six paintings under the heading Study for a series: Love . That was the beginning of what later became a life frieze , "a poem about life, love, death". Here you can find motifs saturated with mood such as the storm , moonlight and starry night , where one can suspect an influence by the Swiss-German Arnold Böcklin . Other motifs such as rose and amalie or vampire illuminate the night side of love. Several of the paintings are about death, and most of the attention was drawn to Death in the Sick Room . In this composition, Munch's indebtedness to French synthetists and symbolists is particularly noticeable. In bright and at the same time pale colors, the picture shows a frozen scene, comparable to a tragic final tableau in an Ibsen play . Here, too, the motif is based on the memory of the death of Sister Sophie, and the whole family is represented. The dying woman sitting in the chair turns her back to the viewer, but is brought into view by the figure that Munch himself imagines. In the following year, the frieze is expanded to include motifs such as fear , ashes , Madonna and Sphinx (the woman in three stages) . The latter is a monumental motif entirely in the spirit of symbolism .

Together with Meier-Graefe, Przybyszewski and others published the first publication on Munch's art in 1894 . He characterizes it as "psychological realism".

Back in France in 1896

Munch left Berlin in 1896 and settled in Paris, where Strindberg and Meier-Graefe were among others. Here he paid more and more attention to graphic means at the expense of painting. He had already started with etching and lithography in Berlin , now in Paris he created exquisite color lithographs and his first woodcuts in collaboration with the famous printer Auguste Clot . Munch also planned to publish a portfolio with the title “Der Spiegel”, a graphic “frieze”. Thanks to his sovereign mastery of the means and his great artistic originality, Munch enjoys the reputation of a graphic classic in our time .

In Paris, he also made program posters for two Ibsen performances at the Théâtre de L'Œuvre , while the commission to illustrate Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du Mal remained in its infancy.

The turn of the century

Returning to Norway in 1898, Munch created the illustrations for a special edition of the German magazine Quickborn on texts by August Strindberg.

At the turn of the century , Munch tried to complete the frieze. He painted a number of new pictures, some in larger format and partly shaped by the Art Nouveau aesthetic . For the large picture Metabolism / Metabolism (1898) he made a wooden frame with carved reliefs . It was initially given the title Adam and Eve and reveals the central place that the myth of the Fall of Man occupies in Munch's pessimistic love philosophy. Motifs such as The Empty Cross and Golgotha (both around 1900) reflect a metaphysical orientation in Munch's own time and are also an echo of Munch's childhood and youth in a pietistic milieu.

A stressful love affair with Tulla Larssen at that time encouraged Munch to experience art as a vocation .

The time around the turn of the century was a phase of restless experimentation. A colorful and decorative style manifested itself, influenced by the art of the Nabis and especially a Maurice Denis . In 1899 Munch painted The Dance of Life , which can be seen as a bold and personal monumentalization of this decorative flat style.

A series of landscape images have the Christiania Fjord as their theme. These decorative and delicate studies of nature are considered to be the high points of Nordic symbolism. The classic atmospheric painting The Girls on the Bridge was created in the summer of 1901 in Åsgårdstrand.

The dance of life (1899/1900)

The Girls on the Bridge (1901)

Success and crisis

By the beginning of the new century, Munch was seriously about to build a career . In 1902 he showed the entire frieze for the first time at the exhibition of the Berlin Secession . A Munch exhibition in Prague became important for several Czech artists. Portraits , often full-length, gradually became an important part of his work. The group portrait The four sons of Dr. Max Linde (1903, Museum Behnhaus , Lübeck ) is classified as a major work of modern portrait painting . At that time he often sought relaxation in Travemünde and gave the Behnhaus the painting of the same name out of solidarity.

The Fauvists, led by Matisse , shared with Munch many of his artistic endeavors. The artist group Brücke in Dresden showed interest in Munch, but did not succeed in winning him over for their exhibitions.

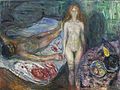

The artistic success was accompanied by conflicts on a personal level. The alcohol had become a problem, and Munch was mentally unbalanced. He tormented himself with memories of his tragic love story. The relationship with Tulla had ended in 1902 with a revolver scene in which Munch's left hand was shot. It is true that he should never get over the shame; but in those years it became an obsession. Tulla's features can be traced in, among other things, Marat's Death (two versions from 1907), a motif which, more generally, can be said to depict “the struggle between man and woman, which one can call love”.

Henrik Ibsen died in May 1906, and in autumn Munch made the stage designs for Max Reinhardt's performance of the ghosts in the small hall of the Deutsches Theater Berlin . A version of his frieze of life was installed here in the foyer, which Reinhardt later sold and can now be seen in the Berlin National Gallery. Since then Ibsen has occupied an ever larger space in Munch's consciousness: the self-portrait with a wine bottle from 1906 shows a limp, slumped figure, sitting alone at a table in a claustrophobic café; a tragic apparition, intellectually closely related to Oswald in Ibsen's drama.

Upon request, Munch made a monumental fantasy portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche , and during several visits to Weimar he portrayed the sister of the late philosopher, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche . The Nietzsche portrait was the only portrait that Munch created from a photograph and not from a living model . During this time Munch also portrayed Count Harry Kessler and Henry van de Velde .

Between 1902 and 1908 Munch stayed mainly in Germany. Painting commissions took him several times to Berlin, Lübeck (1903), Weimar (1904) and Chemnitz (1905). Thereafter, Thuringia with Elgersburg , Weimar, Ilmenau and Bad Kösen (1905/1906) and finally Warnemünde (1907/1908) became his more permanent domiciles . Warnemünde was supposed to be the last station of the self-chosen German exile and for a short time offered the desired physical and mental relaxation.

New motifs testify to a more extraverted orientation. Bathing Men (1907/1908) cheerfully pays homage to vital masculinity. Alcohol and nerve problems reached a critical point, however, and Munch decided to spend eight months in a Copenhagen mental hospital under the supervision of Daniel Jacobson . His artistic achievement was finally recognized in Norway, and while he was in the clinic, he was awarded the Norwegian Order of Saint Olav .

Marat's Death II (1907)

Friedrich Nietzsche (1906)

Back in Norway

Munch lived in Norway from 1909 until the end of his life. First he settled in Kragerø , a coastal town in the south of the country. Here he painted, among other things, several classic winter landscapes and eagerly rushed into the competition to decorate the new ballroom of Oslo University , the auditorium .

In 1912, Munch was given an important place among the pioneers of modern art at the great Sonderbund exhibition in Cologne .

He had spacious outdoor studios built in Kragerø , where he worked on the designs for the university auditorium for several years. After lengthy arguments, Munch was finally accepted and his work was assembled on site in 1916.

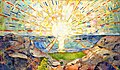

In Munch's own words, the motifs pay homage to “the eternal forces of life”. The background motif, called The Sun , is a sunrise over the fjord , inspired by the view Munch had from his rented property in Kragerø. At the same time he uses the symbolic potential of light here. The counterparts in the auditorium are the large screens Die Geschichte and Alma Mater . An old man sits under a mighty oak tree in a barren, rough landscape and tells a little boy the legend of the people. In a wild, lush landscape, a woman sits with an infant on the beach while older children scout out nature. Apart from the fact that the two “ archetypal ” motifs allude to humanities and natural science , they are expressions of the male and female principle, which is a central contrast in Munch's world of images.

Munch devoted himself to the emerging labor movement in several motifs from that time, some in monumental form. The painting Workers on the Way Home (1913–15) is also a dynamic study in perspective and movement. In 1916 Munch acquired the Ekely property from Christiania. Landscape, people in harmony with nature, plowing horses are motifs that are now depicted in clear, strong colors. Fresh, spontaneous brushwork gives the impression of a sensual homage to the sun, air and earth.

On Ekely , Munch lived in increasingly self-chosen isolation , spartan , surrounded only by his pictures. He was extremely productive. Although he was reluctant to part with "his children", the pictures were loaned to a number of exhibitions at home and abroad.

In later years Munch often painted studies and compositions from models. There are some among them that are more vivid and life-affirming than previous works. And yet he still devoted himself to researching the conflict-laden topics from the 1890s. His graphic production continued to be considerable, including a number of lithographic portraits. Edvard Munch died in January 1944.

The Sun (1911)

estate

In his will, Munch bequeathed his extensive collection of images and unsystematic biographical-literary records to the city of Oslo. The Munch Museum ( Munchmuseet ), which was officially opened in 1963 , therefore has a unique collection of Munch's art and other material that sheds light on all phases of the artistic creative process.

The National Gallery ( Nasjonalgalleriet ) in Oslo also has an exquisite Munch collection, particularly rich in key early paintings. Major works are also located in Bergen Billedgalleri in Bergen .

In 1964, his works were shown at the documenta III in Kassel in the famous hand drawings department . Munch had been a member of the German Association of Artists since 1906 .

In the summer of 2004 the paintings The Scream and Madonna were stolen from the Munch Museum in Oslo . At first, the police assumed that two to five people were probably involved in the theft. Police later charged several suspects, but the images continued to disappear. It was believed that they were hidden abroad. Since the works were stolen in broad daylight, a discussion about how to secure valuable art objects that should nevertheless remain accessible to a broad public developed after the robbery. On 31 August 2006, the two images were - taken out of the frame - by the Norwegian police ensured . The restored pictures were presented to the public again on May 23, 2008 as part of a special exhibition, with a completely new catalog raisonné presented by Munch and the time of origin of the scream being corrected to 1910.

In 2012, one of the four variations of The Scream was auctioned in New York for $ 119.9 million. It thus replaced the painting Nude with Green Leaves and Bust by the Spanish painter Pablo Picasso as the most expensive painting in the world at auction at the time .

Another theft of the painter's works took place on March 6, 2005 from a hotel in Moss , Norway . The perpetrators took two lithographs depicting Munch himself and the writer August Strindberg, as well as a watercolor with the title The Blue Dress . A day later, the police managed to arrest the perpetrators.

Works (selection)

- 1885/1886: The Sick Child (National Gallery, Oslo)

- 1889: Spring (National Gallery, Oslo)

- 1889: Inger on the beach (art museum, Bergen)

- 1890: Night in Saint-Cloud (National Gallery, Oslo)

- 1890: Spring on Karl Johans gate (art museum, Bergen)

- 1891: Rue Lafayette (National Gallery, Oslo)

- 1892: Despair ( Thielska galleriet , Stockholm)

- 1892: The Kiss (National Gallery, Oslo)

- 1892: Melancholy (National Gallery, Oslo)

- 1892: Evening on Karl Johans gate (art museum, Bergen)

- 1893: The Scream (National Gallery, Oslo)

- 1893: The Voice ( Museum of Fine Arts, Boston )

- 1893: Starry Night ( The J. Paul Getty Museum , Los Angeles)

- 1893: The Tempest ( Museum of Modern Art , New York)

- 1893: Death in the Sick Room (National Gallery, Oslo)

- 1894/95: puberty (National Gallery, Oslo)

- 1894: The woman in three stages (Kunstmuseum, Bergen)

- 1894: Fear (Munch Museum Oslo)

- 1894/95: Madonna (National Gallery, Oslo)

- 1895: jealousy (art museum, Bergen)

- 1895: On his deathbed (Kunstmuseum, Bergen)

- 1895: Ashes (National Gallery, Oslo)

- 1895: Self-portrait with a burning cigarette (National Gallery, Oslo)

- 1896: Detachment (Munch Museum Oslo)

- 1898/99: Girls and three men's heads (discovered in 2005 on a lower canvas under the picture The dead mother ) Kunsthalle Bremen

- 1898/99: Metabolism (Munch Museum, Oslo)

- 1899/1900: The Child and Death (Kunsthalle Bremen)

- 1899/1900: The Dance of Life (National Gallery, Oslo)

- 1901: Girls on the Bridge (National Gallery, Oslo)

- 1903: The four sons of Dr. Max Linde (Museum Behnhaus , Lübeck)

- 1904: Linde frieze (mainly Munch Museum, Oslo)

- 1905: Self-portrait with Tulla Larsen (2 parts, Munch Museum, Oslo)

- 1906: Self-portrait with a wine bottle (Munch Museum, Oslo)

- 1906: Portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche ( Thielska galleriet , Stockholm)

- 1906/07: Reinhardt-Fries (mainly Neue Nationalgalerie , Berlin)

- 1907: Marat's Death I and II (Munch Museum, Oslo)

- 1907: Amor and Psyche (Munch Museum, Oslo)

- 1911: The Sun (Aula, University of Oslo )

- 1922: Freia-Fries ( Freia chocolate factory , Oslo)

- 1942: Self-portrait between clock and bed (Munch Museum, Oslo)

Spring (1889)

Inger on the Beach (1889)

The Kiss (1892)

Evening on Karl Johans gate (1892)

The Voice (1893)

Jealousy (1895)

On the deathbed (1895)

The Child and Death (1899)

literature

in alphabetical order by authors / editors

- Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986, ISBN 3-499-50351-4 .

- Arne Eggum : Alpha & Omega . Translated by Signe Bøhn, catalog, Oslo 1981, ISBN 82-90128-11-8 .

- Arne Eggum: The linden frieze - Edvard Munch and his first German patron, Dr. Max Linde . Translated from the Norwegian by Alken Bruns. Publication XX of the Senate of the Hanseatic City of Lübeck - Office for Culture. Lübeck 1982, ISBN 978-3-92421417-3 , limited preview in the Google book search.

- Inger Alver Gløersen: Munch as I knew him. Bløndal, Hellerup 1994

- Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work. Prestel, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 .

- Bettina Kaufmann: Symbol and Reality: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's Pictures from Fantasy and Edvard Munch's Frieze of Life. Dissertation from the University of Friborg , 2005. Peter Lang, Frankfurt a. M. 2007, ISBN 978-3-03910-661-5 , limited preview in Google Book Search.

- Jan Kneher: Edvard Munch in his exhibitions between 1892 and 1912. A documentation of the exhibitions and study on the history of the reception of Munch's art. (= Manuscripts for art history in the Werner publishing company , 44). Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft, Worms 1994, ISBN 978-3-88462-943-7 .

- Ursula Marinelli: Edvard Munch and the idea of the good painting. In: textfeld , 2007, full text .

- Atle Næss: Edvard Munch. A biography. Berlin University Press, Wiesbaden 2015, ISBN 978-373-74131-0-7 .

- Gerd Presler : Edvard Munch - catalog raisonné of the sketchbooks. Engelhardt and Bauer, Karlsruhe 2004, ISBN 3-937295-09-7 .

- Berit Ruud Retzer: Edvard Munch. Gjennombruddet. [ The breakthrough. ] Koloritt, Oslo 2012, ISBN 978-82-92395-83-7 .

- Johann-Karl Schmidt : appearance and reflection. In: Edvard Munch and his models. Hatje, Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-7757-0413-2 .

- Uwe M. Schneede : Edvard Munch. The masterpieces. Schirmer / Mosel Verlag, Munich 1988/2000, ISBN 3-88814-992-4 .

- Ragna Stang: Edvard Munch. The man and the artist. Langewiesche, Königstein im Taunus 1979, ISBN 3-7845-9360-7 .

- Fiction

- Espen Haavardsholm: A love in the days of light - novel by Edvard Munch. (Original title: Besøk på Ekely ). Osburg Verlag, Hamburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-95510-020-9 .

- Tanja Langer : The painter Munch. Novel. Langen-Müller, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-7844-3335-6 .

Documentaries

- Munch's demons. Documentary with scenic documentation, Germany, 2013, 52 min., Script and director: Wilfried Hauke , production: dmfilm, Radio Bremen , arte , first broadcast: December 15, 2013 on arte, summary by ARD , review:.

- The mirrored look. Self-portraits by Edvard Munch. Documentary with scenic documentation, Germany, 2006, 29:22 min., Script and director: Marita Loosen, production: Bildersturm, WDR , arte , broadcast: February 18, 2007 on arte, synopsis by ARD, online video.

- Edvard Munch - love, death and life. Documentary, Germany, 2003, 43:30 min., Script and direction: Angelika Lizius, production: Bayerisches Fernsehen , series: Faszination Kunst , synopsis by ARD.

- Edvard Munch . Docu-drama , Norway, Sweden, 1974, 211 min., Written and directed by Peter Watkins , first broadcast: November 12, 1974 in Norway.

Web links

- Literature by and about Edvard Munch in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Edvard Munch in the German Digital Library

Museums

- Munch Museum Oslo

- Edvard Munch House Warnemünde

- Exhibitions on kunstaspekte.de

various

- ZeitZeichen : 01/23/1944 - anniversary of the painter Edvard Munch's death In: WDR5 , 2019, 14:42 min.

- Extensive collection of material on Edvard Munch in Schirn Mag , 2012

Individual evidence

- ↑ James F. Masterson: Search For The Real Self. Unmasking The Personality Disorders Of Our Age , Chapter 12: The Creative Solution: Sartre, Munch, and Wolfe , pp. 208-230, Simon and Schuster, New York 1988, ISBN 1451668910 , pp. 212-213, limited preview in Google - Book search.

- ↑ Tove Aarkrog: Edvard Munch: the life of a person with borderline personality as seen through his art , Lundbeck Pharma A / S, Denmark 1990, ISBN 87-983524-0-7 .

- ↑ Albert Rothenberg: Bipolar illness, creativity, and treatmernt. In: The Psychiatric quarterly , Volume 72, Number 2, 2001, pp. 131-147, ISSN 0033-2720 , PMID 11433879 , doi: 10.1023 / A: 1010367525951 .

- ↑ Ulrich Bischoff : Edvard Munch 1863-1944, Pictures of Life and Death , Taschen , Cologne 2006, ISBN 978-3-8228-6369-5 .

- ↑ Nikolaus Bernau : Where did Munch's “Life Frieze” hang? On the construction of the Kammerspiele and their most famous jewelry , in: Roland Koberg, Bernd Stegemann , Henrike Thomsen (eds.): Blätter des Deutschen Theater. Max Reinhardt and the Deutsche Theater , Henschel, Leipzig 2005, ISBN 3-89487-528-3 , pp. 65–78, table of contents.

- ↑ Henry van de Velde : Story of my life. In: Digitale Bibliotheek voor de Nederlandse Letteren ( DBNL ), 2008, Munch in Weimar: p. 229; 488, (PDF; 12.37 MB), accessed June 13, 2020.

- ↑ kai: The Painter's Testament - How Edvard Munch gave Oslo as gifts. In: Der Tagesspiegel , November 1, 2005.

- ↑ Munchmuseet. In: munchmuseet.no .

- ↑ Bettina Kaufmann: Symbol and Reality , 2007, ISBN 978-3-03910-661-5 , p. 57, limited preview in the Google book search.

- ↑ Members from 1903. In: Deutscher Künstlerbund , accessed June 13, 2020.

- ↑ Felix Steinbild (firm) / sda : Munch's “Scream” restored and exhibited. ( Memento of February 21, 2009 in the Internet Archive ). In: nachrichten.ch , May 21, 2008.

- ↑ AFP / sab / pku: Auction record: Munch's "The Scream" is the most expensive picture in the world. In: Die Welt , May 3, 2012.

- ↑ rtr: Stolen Munch works secured by the police. In: Die Welt , March 9, 2005.

- ^ Swantje Karich: Kunsthalle Bremen. I am the man, and so am the girl. In: FAZ , October 14, 2011, p. 33.

- ^ Michaela Kleinsorge: Warnemünde. "Munch's demons" are cheered. In: North German Latest News , December 16, 2013.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Munch, Edvard |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Norwegian painter and graphic artist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 12, 1863 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Oslo |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 23, 1944 |

| Place of death | Ekely |