Death in the sickroom

|

| Death in the sickroom |

|---|

| Edvard Munch , 1893 |

| Tempera on canvas |

| 152.5 × 169.5 cm |

| Norwegian National Gallery , Oslo |

|

| Death in the sickroom |

|---|

| Edvard Munch , 1893 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 134 × 160 cm |

| Munch Museum , Oslo |

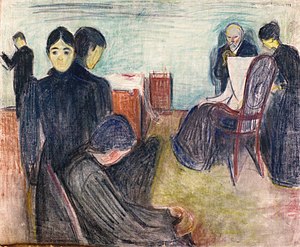

Death in the Sick Room , also Death in the Sick Room ( Norwegian Døden i sykeværelset ), Ein Tod or The Moment of Death , is a pictorial motif by the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch , which he executed in two paintings from 1893. In addition, various sketches , studies and a lithograph were created . In the pictures Munch processed the tuberculosis disease and the death of his older sister Sophie (1862–77). Various members of his family are shown, including, turned away in the foreground, the painter himself. The picture is one of the main works of his life frieze . It marks the transition from the representation of the external to the internal plot in Munch's work and his artistic position between synthetism and symbolism .

Image description

The picture shows a sick room with seven people in it in a long shot . The view of the dying woman is blocked by a wicker chair with a high backrest. Only the pillow and a light arm can be seen resting on a dark blanket. Instead, the gaze is drawn to the "accessories of death" in the background: a bed, a bedpan and medicine bottles on a dessert.

In particular, however, attention is directed to the individual family members of the dying: three figures, whose silhouettes merge, dominate the foreground: A young girl is sitting with folded hands and bowed head. A young woman looks directly at the viewer with an expressive face, dark eyes and pale, sunken cheeks. A young man stands averted and looks at another group of three. It is formed by the dying woman, a female figure facing her and an older man with a bald head and a beard, who is bent over his clasped hands in a frontal view. A second younger male figure on the left edge of the picture seems to want to leave the room at the moment of death.

The room is sparsely furnished. A lot of space surrounds the individual figures, which for Reinhold Heller appear to be “cut out”, isolated and frozen in hieratic poses. The high perspective of the action reminds Arne Eggum of playing on a stage, the empty floor and the mask-like faces create the impression of dead silence. A portrait of the Savior hangs over the bed as a symbol of consolation through religion.

In terms of composition, the motif is characterized by strong contours that delimit the various areas. Lines and curves of one figure are picked up and repeated by other figures. There is thus a formal and emotional continuity. Both painting versions use the same colors and color symbols . The dominant colors are maroon, dark green and a bluish black. The painting from the Nationalgalerie is made in a dry, transparent casein technique, which, with its absence of shadows, reinforces the symbolic expressiveness. The version from the Munch Museum with the saturated oil paint fixes the figures more firmly in space and expresses the power of death with dark shadows.

Autobiographical background

Edvard Munch had experiences with illness and death from an early age. At the age of 33, Munch's mother died of tuberculosis in 1868 when he was just five years old . In 1877, Munch's older sister Sophie died of the same disease at the age of 15. His father died twelve years later. As a child, Munch was weak and often ill; his childhood and youth were overshadowed by constant fear of death. He later said: “Illness and death lived in my parents' house. I probably never got over the misfortune from there. It was also decisive for my art. ”His earliest artistic processing of the death of his sister Sophie and his own fear of death was the motif The Sick Child , with which Munch struggled for about a year until its completion in 1885/86 and which he continued afterwards repainted at regular intervals.

The Sick Child (1885/86), Norwegian National Gallery

On his deathbed (1895), Bergen Art Museum

Corpse Smell (1895), Munch Museum Oslo

Metabolism (1898–99), Munch Museum Oslo

The Child and Death (1899), Kunsthalle Bremen

The death in the sick room shows a different perspective of the painter compared to the sick child who had emerged eight years earlier . The dead woman remains invisible, instead the relatives step into the center of the motif. The memory is no longer for death and dying, but for the feelings of those left behind. The picture thus marks a transition from external to internal experience, which will be characteristic of Munch's future work. The figures in the picture can easily be assigned to Munch's family. In the foreground are the siblings Laura, Inger and Edvard, in the background with the dying Sophie the father Christian Munch and the aunt Karen Bjølstad. Brother Andreas is standing at the exit. However, the painter is not interested in a realistic reconstruction, but in remembering the mood. Although details of the scenery, including the wicker chair, can be found in Munch's personal notes, the figures are not at the age at the time of Sophie's death, but at the age at which the picture was created. Munch's father, however, had died in 1893. Munch thus transfers people from different points in time to the sickroom of the past, possibly to make the presence of the dead and their deaths tangible up to the present.

Munch accompanied the subject of death through many other works. In addition to love , it is a central theme of his life frieze , the compilation of his central works from the 1890s. At the fifth exhibition of the Berlin Secession , the last major joint presentation of the frieze, Munch exhibited a total of 22 pictures and dedicated an entire wall of the room to the subject of death . In addition to Death in the Sick Room , he presented the pictures On the Death Bed , Smell of Corpses , Metabolism and The Child and Death .

Artistic influences

According to Arne Eggum 's Death in the sickroom characteristic of Munch's special position between the post-impressionist art movement of synthetism that approximately from the School of Pont-Aven to Paul Gauguin was represented, and the symbolism that since the World Exhibition in Paris in 1889 in Europe expanded. He traces the image back to forerunners such as the interiors of Edgar Degas and Vincent van Gogh or the mask representations by Gauguin and James Ensor . Reinhold Heller refers to the scenes from the Moulin Rouge by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec or the brittle woodcuts by Félix Vallotton .

Contemporary critics saw Munch's painting primarily influenced by the plays by Maurice Maeterlinck , for whom death manifested itself in the psyche of those who survived. In fact, around the time of the first drafts, Munch was illustrating one of Maeterlinck's plays. In his drama L'Intruse , the dying person is hidden in the adjoining room, in Munch's composition she is hidden by an armchair and yet present in the consciousness of all other people. Others like Matthias Arnold or Uwe M. Schneede , the tableau with the statuesque figures reminds of Munch's Norwegian compatriot Henrik Ibsen . With regard to the alternative title The Moment of Death, Arne Eggum refers in particular to Søren Kierkegaard's philosophy of the meeting of moment and eternity.

interpretation

Matthias Arnold describes the picture as an “ibsen-like” tableau in which the death of Munch's sister Sophie is transported “into the timeless”. The relatives stand around "like puppets, helpless, trusting, in pain". They seem frozen in grief, while the grave event, death, remains hidden. As a result, according to Uwe M. Schneede, the “inner movement of those left behind” becomes the subject of the picture, the inner drama precedes the outer drama. According to Arne Eggum, death is represented "as an absence, as a loss for the survivors." It leaves a gap that accompanies the bereaved through later phases in life, in which Munch presents himself and his family members as if they were forever in the sickroom of the dying Including Sophie.

The bereaved appear not only grieving and helpless in the face of the death of a loved one, but also lonely and isolated from one another. According to Reinhold Heller, it is an image of "existential isolation". According to Hermann Beenken , each person is confronted with the horror of death and dying on their own: “Here, death and dying are the nameless that can express themselves through their real presence. Everyone feels the silent presence of a being who is otherwise not among us and who now penetrates and changes the innermost being, including life itself. ”The death of the other is experienced as something foreign that was previously unknown. "Death no longer takes from man, but the other way round, man takes possession of death, makes it his death, this is the requirement."

Pictorial history

|

| Death in the sickroom |

|---|

| Edvard Munch , 1893 |

| Pastel on canvas |

| 91 × 109 cm |

| Munch Museum , Oslo |

Edvard Munch began work on the motif in Berlin in 1893. Arne Eggum, long-time conservator and director of the Munch Museum in Oslo, suspects that the painter had the explicit intention of painting formative memories. He made a total of two large versions of the picture, one of which hangs in the Norwegian National Gallery and one in the Munch Museum. In addition, various sketches and studies were made, including a pastel that is also kept in the Munch Museum.

Munch presented the painting, at that time still under the title Ein Tod , for the first time on December 5, 1893 in Berlin together with a cycle of pictures under the title Study for a Series: Die Liebe . This cycle was a preliminary stage of the later life frieze and contained the pictures The Voice , The Kiss , Vampire , Madonna , Melancholy and The Scream . The picture A Death was found directly at the entrance to the exhibition and, according to Reinhold Heller, depicted the death motif with a directness that was not previously present in Munch's work.

Contemporary critics highlighted Ein Tod as particularly positive among the exhibited pictures. Willy Pastor wrote in the Frankfurter Zeitung that in Munch's work there is “the beginning at the end [and] the end at the beginning”. The artist convince himself of the nature of things “in a fleeting sketch. As in a focal point, he lets the innumerable lines of the outside world converge and ignite; but with the flame that then strikes up, he shines into the interior of his soul, deeper and deeper he looks down into the abysses that gape there. ”Nic. However, Stang reports a basically hostile reception by the audience and critics, in which it was criticized that one could not recognize the dead person and did not even know whether it was a man or a woman.

In 1896 Munch made a lithograph based on the motif. There are prints of these in Berlin, Dresden, Frankfurt am Main, Hamburg, Leipzig, Saarbrücken, Salzburg, Wiesbaden and Zurich, among others. Thanks to the strong black and white contrasts in the lithography, Munch achieved, according to Arne Eggum, “an even more audible silence than in one of the painted versions”.

The manufacturer and art collector Olaf Schou donated the tempera painting to the Norwegian National Gallery in 1910.

literature

- Arne Eggum : Death in the sickroom. In: Edvard Munch. Love, fear, death . Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld 1980, without ISBN, pp. 225–235.

- Arne Eggum: Death in the sick room, 1893. In: Edvard Munch. Museum Folkwang, Essen 1988, without ISBN, cat. 31.

- Arne Eggum, Sissel Biørnstad: Death in the Sickroom . In: Mara-Helen Wood (ed.): Edvard Munch. The Frieze of Life . National Gallery London, London 1992, ISBN 1-85709-015-2 , pp. 113-115.

- Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , pp. 74-76.

Web links

- Death in the Sick-Room, prob. 1893 in the Norwegian National Gallery.

- Døden i sykeværelset in the Munch Museum Oslo

Individual evidence

- ^ Ulrich Bischoff : Edvard Munch . Taschen, Cologne 1988, ISBN 3-8228-0240-9 , p. 56.

- ↑ a b c d Arne Eggum, Sissel Biørnstad: Death in the Sickroom . In: Mara-Helen Wood (ed.): Edvard Munch. The Frieze of Life . National Gallery London, London 1992, ISBN 1-85709-015-2 , p. 113.

- ↑ a b c d Arne Eggum : The death in the sick room, 1893. In: Edvard Munch. Museum Folkwang, Essen 1988, without ISBN, cat. 31.

- ↑ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , pp. 75-76.

- ↑ Arne Eggum, Sissel Biørnstad: Death in the sickroom . In: Mara-Helen Wood (ed.): Edvard Munch. The Frieze of Life . National Gallery London, London 1992, ISBN 1-85709-015-2 , pp. 113-114.

- ^ A b c Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , p. 52.

- ↑ Arne Eggum, Sissel Biørnstad: Death in the sickroom . In: Mara-Helen Wood (ed.): Edvard Munch. The Frieze of Life . National Gallery London, London 1992, ISBN 1-85709-015-2 , pp. 114-115.

- ^ Uwe M. Schneede : Edvard Munch. The sick child. Work on memory. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-596-23915-X , pp. 30-32, 38, 60-62.

- ↑ a b c d Uwe M. Schneede: Edvard Munch. The early masterpieces. Schirmer / Mosel, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-88814-277-6 , comments on plate 12.

- ↑ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , p. 75.

- ↑ Nic. Stang: Edvard Munch . Ebeling, Wiesbaden 1981, ISBN 3-921452-14-7 , pp. 65-66.

- ↑ a b c d Arne Eggum, Sissel Biørnstad: Death in the Sickroom . In: Mara-Helen Wood (ed.): Edvard Munch. The Frieze of Life . National Gallery London, London 1992, ISBN 1-85709-015-2 , p. 114.

- ^ Hans Dieter Huber : Edvard Munch. Dance of life . Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , pp. 69-70.

- ↑ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , p. 76.

- ↑ Arne Eggum: Death in the sickroom. In: Edvard Munch. Love, fear, death . Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld 1980, without ISBN, p. 226.

- ↑ a b Quotations from: Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , p. 76.

- ↑ a b Arne Eggum : Death in the sickroom. In: Edvard Munch. Love, fear, death . Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld 1980, without ISBN, p. 225.

- ^ Edvard Munch: Døden i sykeværelset . In the Munch Museum Oslo .

- ↑ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , p. 74.

- ↑ Nic. Stang: Edvard Munch . Ebeling, Wiesbaden 1981, ISBN 3-921452-14-7 , pp. 65-66.

- ↑ Gerd Woll: Edvard Munch. The Complete Graphic Works . Orfeus, Oslo 2012, ISBN 978-82-93140-12-2 , pp. 63-64.

- ^ Death in the Sick-Room, prob. 1893 in the Norwegian National Gallery.