Madonna (Munch)

|

| Madonna |

|---|

| Edvard Munch , 1894 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 90 × 68 cm |

| Munch Museum Oslo |

|

| Madonna |

|---|

| Edvard Munch , 1894/95 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 90.5 × 70.5 cm |

| Norwegian National Gallery , Oslo |

|

| Madonna |

|---|

| Edvard Munch , 1895 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 90 × 71 cm |

| Hamburger Kunsthalle |

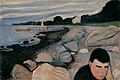

Madonna (also The Madonna Face or Loving Woman ) is a pictorial motif by the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch , which he executed in five paintings between 1894 and 1897 and in a lithograph in 1895 . It shows the half-length of a woman with a naked torso and half-closed eyes. The title suggests the tradition of portraits of the Madonna , the pictorial representations of Mary , the mother of Jesus . The real model for the picture is the Norwegian Dagny Juel . It is part of Munch's life frieze , the compilation of his central works on the themes of life, love and death.

Versions

The catalog raisonné by Gerd Woll total of five lists painting entitled Madonna on the 1894, 1894-95, 1895 and 1895-97 have emerged twice, see also the list of paintings by Edvard Munch . In the order in which they were created, they are now owned by the Munch Museum Oslo , in which Munch's estate is kept, the Norwegian National Gallery , which received the picture in 1909 as a gift from the art collector Olaf Schou, the Hamburg Art Collections Foundation, which acquired it in 1957 and as Exhibits on permanent loan at the Hamburger Kunsthalle , as well as two private collections ( Steven A. Cohen as well as Catherine Woodard and Nelson Blitz Jr.).

Edvard Munch: Madonna . Lithograph, 1895, 59.8 × 44 cm, The Clark , Williamstown

Edvard Munch: Madonna . Lithograph, 1895/1902, 60.5 × 44.4 cm, Ōhara Art Museum , Kurashiki

In 1895 Munch made a lithograph of the motif. There is a lithograph of Vampire on the back of the printing block . The early prints are hand-colored. In 1902 Munch added two color plates to lithography. Prints from different stages of lithography can be found in German-speaking countries in Basel, Berlin, Bern, Dresden, Hamburg, Cologne, Lübeck, Munich and Vienna.

Image description

The naked body of a woman, shown to the point of shame, is monumentally moved into the center of the portrait-format picture. Through the position of the arms, which are placed behind the head and waist and seem to disappear in the streams of color, the chest and stomach are bent forward, literally stretched out towards the viewer. The woman's black hair flows over her shoulders, her head, which is tilted back, is framed by a bright red halo that is not much larger than a headdress. The woman's eyes are almost closed in a state, as Ulrich Bischoff puts it, “between sleep and wakefulness, between lying and standing, between emerging and sinking, between showing and hiding”. The eyes are geometrically simplified as well as other parts of the body.

The body of the Madonna stands out with its three-dimensional, naturalistically rounded shape against the flat, abstract background. that traces the silhouette, but also reminds Reinhold Heller of the shape of a uterus. Bischoff sees the body in a “peculiar floating state”. This is also due to the broad brushstrokes of paint that flow around the body. They draw their tension from the contrast of brown-red and blue-black. For Bischoff, however, the defining contrast is that between the pitch-black hair and the signal red of the halo, the color of which can also be found in the nipples and navel. The colors are generally applied very thinly, so that the white primer and the canvas shimmer through. There are drops on parts of the painting, which Munch intended and therefore not overpainted, reinforcing the impression of a quick, passionate work.

When it was first exhibited, the picture is said to have been surrounded by a frame with carved or painted sperm and embryos . However, it was later lost. Its design can still be found in the lithography.

model

Many authors believe that they recognize Dagny Juel in the facial features of the Madonna . Arne Eggum restricts that the final proof of this is missing. However, her father requested that the picture be removed from an exhibition. Dagny Juel was a Norwegian writer who frequented Berlin artistic circles in the early 1890s, which included August Strindberg , Stanisław Przybyszewski and Edvard Munch. According to Matthias Arnold, all three are said to have courted the young Norwegian. In the end, she decided on the Polish writer.

Photograph by Dagny Juel , 1894

Edvard Munch: Dagny Juel Przybyszewska , 1893, 158 × 112 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

Julius Meier-Graefe wrote: “Strindberg saw in her a purposeful Messalina of the last devilish, from whom one could not escape far enough and who even kept one on the tape in the distance. Munch thought similarly and when we talked about her among ourselves, Munch called her the lady, which should mean nothing more than necessary foreignness [...] Perhaps Munch had her, I don't know, called her anyway, and especially the lady. Maybe Strindberg, easily possible. She probably had many. Nobody has owned it. ”The nature of the relationship between Munch and Juel is not known. However, the painter is said to have had a portrait of her hanging over his bed in his later years, and Munch's painting Jealousy is generally viewed as a pictorial representation of the triangular relationship between Juel, Przybyszewski and Munch.

interpretation

According to Arne Eggum, Munch's Madonna has been interpreted in different directions: from the representation of an orgasm to the emergence of life and finally - not least by Munch himself - the closeness to death.

Eros

The art historian Werner Hofmann spoke of the Madonna as a " devotional image of the Eros of the Decadence". Arne Eggum and Guido Magnaguagno refer to the nimbus , the halo that is reminiscent of religious images of the Madonna , while the lascivious nudity borders on blasphemy . The contemporary critic Franz Servaes stated : “It is the moment shortly before the highest rush of love and the most blissful devotion. The woman, close to her most sacred fulfillment, receives a moment of unearthly beauty. [...] The man who participates in this sight can probably receive the vision of a Madonna. ”Reinhold Heller sees a woman“ depicted in a moment of sexual ecstasy ”in a similar way, whereby the viewer assumes the partner's view during sexual intercourse. The embryo in the picture is the fruit of this union.

Life

For Munch, according to Heller, the “terrifying cosmic power” of sexuality was “the essence of life”, which also led to the emergence of new life. In this sense, he sees the Madonna as “symbolizing the moment of conception, in which past and future meet”. The color scheme of the picture and the flowing aura that surrounds the female figure arouse associations with the womb. He speculates that the model for the Madonna could also have been Dagny Juel's sister, who was pregnant when the picture was taken. Tone Skedsmo, too, sees the picture, above which she sees a peaceful, harmonious mood, under the theme of conception: that moment in which new life is created. In his life frieze , Munch tried to capture people who breathe, live, suffer and love, but few pictures are so charged with love and feeling as Madonna , in which femininity becomes the starting point of the mystery of life.

death

As is often the case with Munch, the origin of life also refers to death. In the album The Tree of Knowledge, for better or for worse , he added the text to the lithograph: “The pause in which the world continues its course / Your face contains all the beauty of the earth / Your lips crimson like the coming fruit / slide from each other as in pain / The smile of a corpse / Now life is reaching out to death / The chain is being tied, connecting the thousand generations / the dead with the thousand generations that are coming. ”Already the pose of the Madonna with her behind the body hidden arms is on the one hand a beauty pose of the 19th century, but also reminds Reinhold Heller of a classic pose of Greek sculptures of dying niobes . Arne Eggum draws a connection to the goddess Astarte , at the same time goddess of fertility and death, whose symbol the crescent moon he associates with the red halo of the Madonna . He sees Munch's picture as a “pseudo-sacred cult image” that expresses the connection between love and death that was common in 19th century thought. The formulation of such a private theology was one of the essential contemporary demands on the artists of Symbolism .

Work context

Munch carried out his first studies on the Madonna motif between 1892 and 1894. Munch also used the special features of the Madonna's face in later works , for example in Lovers and On the Waves of Love . Arne Eggum also interprets the motif of this lithograph from 1896 as a “cult image of a primitive quasi-religion, which in self-abandonment the bliss sees ”,“ consciousness to pass into all-consciousness, the consciousness of death and love ”. The lithograph Kiss of Death , to which Munch once again gave the features of the Madonna in 1899, shows an even more direct turn to death .

On the waves of love . Lithograph, 1896, 31 × 42 cm, Detroit Institute of Arts

Kiss of death . Lithograph, 1899, 29.5 × 46.0 cm, Thielska galleriet , Stockholm

The day after , 1894, 115 × 152 cm, Norwegian National Gallery , Oslo

The painting The Day After , into which Munch transferred the Madonna face in 1894, is also directly related to the work . Stanisław Przybyszewski mixed the two motifs when he described: “It is a woman in a shirt with the characteristic movement of absolute devotion in which all organ sensations become erethisms of intense lust; a Madonna in a shirt on crumpled sheets with the halo of the coming martyrdom, a Madonna grasped at the moment when the secret mysticism of the eternal intoxication lets a sea of beauty shine on the woman's face, in which the whole depth of feeling occurs, because the cultural man with his metaphysical urge for eternity and the animal with his lustful destructiveness meet. ”The first version of The day after is lost and is said to be very different from the 1894 version.

The Voice , 1893, 88 × 108 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Kiss , 1892, 73 × 92 cm, Norwegian National Gallery , Oslo

Vampire , 1893, 80.5 × 100.5 cm, Art Museum, Gothenburg

Melancholy , 1892, 64 × 96 cm, Norwegian National Gallery , Oslo

The Scream , 1893, 91 × 73.5 cm, Norwegian National Gallery , Oslo

A first exhibition of the Madonna motif in the context of other works took place in December 1893 in Berlin in a rented exhibition space on Unter den Linden . Munch presented the pictures The Voice , The Kiss , Vampire , Madonna , Melancholie and The Scream under the title Study for a series “Love” . According to Hans Dieter Huber, the sequence of images tells the linear course of love, from the attraction of the sexes on a summer night, a kiss and the robbery of the man’s strength, through the shining of the woman in full bloom and the man’s sinking into melancholy to the final Fear of life is enough. From this series arose later, enriched by the themes of life and death, the frieze of life , the compilation of the central works of the painter under the motto “a poem about life, love and death”.

Reception and public perception

According to Nina Denney Ness, an employee of the National Museum Oslo , Madonna is one of Edvard Munch's most important and well-known pictures. The Hamburger Kunsthalle ranks it among the “key works” of the Norwegian painter. Ulrich Bischoff speaks of " Munch's most famous pictorial invention besides the scream ".

Madonna also came into the public eye through two thefts. In March 1990, a painting valued at 1.6 million Norwegian kroner was stolen from the Kunsthuset gallery in Oslo. It was found three months later, in June 1990. Internationally, a robbery from the Munch Museum Oslo made headlines, in which the Munch Museum versions of Madonna and The Scream were stolen on August 22, 2004 in the middle of opening hours. Only two years later, on August 31, 2006, could the paintings be seized after clues from the Oslo underworld.

In July 2010, a hand-colored print of the lithograph from 1895 was auctioned at Bonhams Action House in London for £ 1.2 million. It was the most expensive art print ever auctioned in Great Britain at the time.

Munch's Madonna is considered a possible model for the all too revealing Madonna image in Thomas Mann's novella Gladius Dei . There is talk of a "holy woman who gave birth, of enchanting femininity, bare and beautiful, her big, sultry eyes darkly rimmed, her delicate and strangely smiling lips half open".

literature

- Ulrich Bischoff : Edvard Munch . Taschen, Cologne 1988, ISBN 3-8228-0240-9 , pp. 40-43.

- Arne Eggum : Madonna . In: Edvard Munch. Love, fear, death . Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld 1980, without ISBN, pp. 29–45.

- Arne Eggum, Guido Magnaguagno: Madonna, around 1894 . In: Edvard Munch . Museum Folkwang, Essen 1988, without ISBN, cat. 41.

- Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , pp. 80-81.

- Tone Skedsmo among others: Madonna . In: Mara-Helen Wood (ed.): Edvard Munch. The Frieze of Life . National Gallery London, London 1992, ISBN 1-85709-015-2 , pp. 72-75.

Web links

- Edvard Munch: Madonna in the National Museum Oslo .

- Edvard Munch: Madonna, 1893–1895 in the Hamburger Kunsthalle .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Melancholy, 1892 in the National Museum Oslo .

- ^ Edvard Munch: Madonna, 1893–1895 in the Hamburger Kunsthalle .

- ↑ Madonna 1895–1897 in the Metropolitan Museum of Art .

- ↑ Madonna 1895–1897 in the Metropolitan Museum of Art .

- ^ Gerd Woll: The Complete Graphic Works . Orfeus, Oslo 2012, ISBN 978-82-93140-12-2 , no.39 .

- ↑ a b c d Ulrich Bischoff: Edvard Munch . Taschen, Cologne 1988, ISBN 3-8228-0240-9 , p. 42.

- ↑ a b Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch: The Scream . Viking Press, New York 1973 ISBN 0-7139-0276-0 , p. 52.

- ↑ Carmen Sylvia Weber (ed.): Edvard Munch. Vampire. Readings on Edvard Munch's Vampire, a key image of the early modern age . Catalog for the Edvard Munch exhibition . Vampire , January 25, 2003 - January 6, 2004, Kunsthalle Würth, Schwäbisch Hall. Swiridoff, Künzelsau 2003, ISBN 3-934350-99-2 , pp. 29, 51.

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , p. 56.

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , pp. 56-58, 80, 88.

- ^ Arne Eggum, Guido Magnaguagno: Jealousy, 1895 . In: Edvard Munch . Museum Folkwang, Essen 1988, without ISBN, cat. 42.

- ↑ Arne Eggum: Madonna . In: Edvard Munch. Love, fear, death . Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld 1980, without ISBN, p. 29.

- ^ Werner Hofmann : Das earthische Paradies , Prestel, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-7913-0084-9 , p. 224.

- ↑ Arne Eggum, Guido Magnaguagno: Madonna, around 1894 . In: Edvard Munch . Museum Folkwang, Essen 1988, without ISBN, cat. 41.

- ↑ a b c Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , p. 80.

- ^ Tone Skedsmo among others: Madonna . In: Mara-Helen Wood (ed.): Edvard Munch. The Frieze of Life . National Gallery London, London 1992, ISBN 1-85709-015-2 , p. 72.

- ↑ Arne Eggum: Madonna . In: Edvard Munch. Love, fear, death . Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld 1980, without ISBN, p. 31.

- ^ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch: The Scream . Viking Press, New York 1973 ISBN 0-7139-0276-0 , p. 53.

- ↑ Arne Eggum: Madonna . In: Edvard Munch. Love, fear, death . Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld 1980, without ISBN, p. 32.

- ^ Study til "Madonna" 1892-1893 in the Munch Museum Oslo .

- ^ Study til "Madonna" 1893–1894 in the Munch Museum Oslo .

- ^ Madonnas ansikt in the Munch Museum Oslo .

- ↑ Madonna 1894 in the Munch Museum Oslo .

- ↑ På kjærlighetens bølger in the Munch Museum Oslo .

- ↑ Dødskyss the Munch Museum .

- ↑ Arne Eggum: Madonna . In: Edvard Munch. Love, fear, death . Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld 1980, without ISBN, pp. 32–34.

- ↑ Arne Eggum: Madonna . In: Edvard Munch. Love, fear, death . Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld 1980, without ISBN, p. 33.

- ^ Sue Prideaux : Edvard Munch: Behind the Scream . Yale University Press, New Haven 2005, ISBN 0-300-11024-3 , pp. 91-92.

- ^ Hans Dieter Huber: Edvard Munch. Dance of life . Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , pp. 65-66.

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , p. 42.

- ^ Edvard Munch "... from the modern soul" in the Hamburger Kunsthalle .

- ↑ De fleste kommer til save . In: Verdens Gang of 23 August 2004.

- ↑ Gangster boss provides crucial clues about stolen paintings . In: Frankfurter Zeitung from September 1, 2006.

- ↑ Edvard Munch Madonna print sells for record £ 1.25m . In: The Guardian, July 13, 2010.

- ↑ Andreas Blödorn, Friedhelm Marx (Ed.): Thomas Mann manual. Life - work - effect . Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2015, ISBN 978-3-476-02456-5 , p. 107.

- ↑ Quoted from: Reiner Luyken : Meine Seelenverwandten . In: Die Zeit from April 25, 2013.