The Scream

|

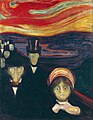

| The Scream |

|---|

| Edvard Munch , 1893 |

| Oil, tempera and pastel on cardboard |

| 91 × 73.5 cm |

| Norwegian National Gallery, Oslo |

|

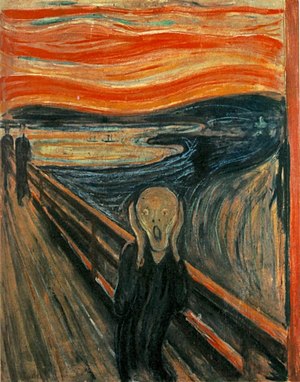

| The Scream |

|---|

| Edvard Munch , 1910 |

| Oil and tempera on cardboard |

| 83 × 66 cm |

| Munch Museum Oslo |

The Scream ( Norwegian Skrik , German originally cries ) is the title of four paintings and a lithograph of the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch with largely identical motif that, between 1893 and 1910th They show a human figure under a red sky, who presses her hands against her head while her mouth and eyes open in fear. In the motif, Munch processed his own anxiety attack during an evening walk, during which he thought he heard a scream that went through nature.

The scream is the best-known motif of the Norwegian painter and part of his so-called frieze of life . It exemplifies how Munch made external nature a mirror of his internal experience in his works, and is seen by some as the beginning of the Expressionist style .

Versions

Four variations of the scream in painting form are known today, see also the list of paintings by Edvard Munch . The main version of the picture was created in 1893 and donated to the Norwegian National Gallery in 1910 by the art collector Olaf Schou . On the back there is an incomplete first version of the motif. The tempera version from 1910 and the pastel version from 1893 are exhibited in the Munch Museum in Oslo . Another pastel version, probably commissioned by Arthur von Franquet in 1895, is in private American ownership.

From the lithography from 1895, there are three different versions that are in the text below the pressure difference (in German: cry and I felt the cry Grosze by nature ). The Staatsgalerie Stuttgart and the Hamburger Kunsthalle own prints of the lithography. An undated pen drawing with a section of the motif is in the Rasmus Meyer collection in the Bergen Art Museum .

Edvard Munch: The Scream . Pastel on cardboard, 1893, 74 × 56 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

Edvard Munch: The Scream . Pen drawing, undated, Bergen Art Museum

Although Munch referred to the motif several times in German as Geschrei or Das Geschrei (on the lithograph, on the back of the pastel from 1895 and in various letters), Der Schrei has prevailed as the picture title. This results in about sigbjørn obstfelder back to being the German translation of the monosyllabic shortness of Norwegian title Skrik imitated. In addition, the designation of the picture as a scream allows for the interpretation not intended by Edvard Munch, in which the foreground figure screams out her existential fears, which corresponded to the zeitgeist of the 20th century.

Image description

In the foreground of the pictures a single person is facing the viewer frontally. She pressed her hands to her head, her eyes and her mouth were wide open, which, according to Reinhold Heller, expressed "an extreme state of shock". For Atle Næss , the elongated oval of the mouth is a “formulaic symbol” for the “deforming power of fear”. Matthias Arnold describes a “sexless, ghostly, fetus-like human being” with a “skull face”. The calm posture of two other figures on the left edge of the picture contrasts with the excitement of the figure in the foreground. All three are on a bridge, the railing of which cuts the picture diagonally and creates a strong perspective slant. The rhythmic, undulating lines of the landscape form a contrast to this, which, according to Arne Eggum and Guido Magnaguagno, “open up an unpredictable abyss”. The blood-red sky, which is also interspersed with yellow and pale blue lines, completes the picture at the top. According to Hans Dieter Huber, a red stripe on the right-hand side of the version from 1893 has the effect of a “spatial repoussoir ” that intensifies the effect of depth .

The curved lines of the sky can be found in the contour of the figure in the foreground. Their brownish-blue-green tint takes up the colors of the landscape. For Reinhold Heller, there is “no distinction between landscape, sky and figure” in terms of the basic formal and color character. Everything seems to merge into one unit if the diagonal of the bridge did not split the picture and create a “schizophrenic, insurmountable break between the forced deep suction and the whole of figure, landscape and sky, which is attached to the surface”. This tension between depth and surface is intensified by the "crude" application of paint with quick brushstrokes without the delicate color transitions from Munch's earlier works.

In the pastel from 1893 (like all versions of the motif on gray cardboard) the fjord stands out for Hans Dieter Huber "like a whale" in the landscape. Around the head of the " homunculus " in the foreground there is a greenish color "like a snake". The sky consists of "female-oval, opening and closing" shapes. Violet and dark blue are the colors with which Munch characterizes a passive-melancholy man, while yellow, orange and red are those of the active and threatening woman. The colors of the sky in the early pastel version do not yet have the luminosity of the later versions. For Huber, they seem like they are “flooded” or submerged in water.

Munch painted the landscape of the subsequent version of oil paint , tempera and pastel from 1893 without preliminary drawing with heavily diluted paint, which produced washed-out, dirty, transparent surfaces. Then he created individual lines and waves with a thick layer of paint. In contrast to the earlier pastel version, he applied the sky in opaque yellow-orange tones, which form a much stronger contrast to the blue-violet and blue-green tones. With light blue-purple pastel chalk he set outlines and highlights and framed the figure's head with a tangle of lines. The sky was brightened a little by an orange-red chalk. In the upper left corner of the sky, Munch wrote in pencil the words: “kan kun være malet af en gal mand” (“can only have been painted by a mad man”).

The pastel from 1895 is even more intense in color than the tempera versions. Reinhold Heller described: "[It] ... explodes and pulsates with intense color, with sharp reds, poisonous yellows, crashing orangs, scorching blues and gloomy green." As a result, it screams "louder, more persistent, more intense, brighter".

In the black-and-white lithograph from 1895, lines take the place of color effects. The curvature of the swaying figure in the foreground is even more pronounced here. For Anni Carlsson, the vertical lines in the background and the wavy lines in the sky “look like sound waves in which the scream is propagated”. With this, the message of the picture is reversed for her and the person no longer becomes the mood bearer of nature, but nature the mood bearer of man.

The last version of the motif from 1910 is painted with very thin oil paint mixed with turpentine oil . Reinhold Heller sees it less controlled and more intense in the interaction between figure and landscape than the painting from 1893. Poul Erik Tøjner and Bjarne Riiser Gundersen describe: “Munch is disciplined about his means [...] and the management of the motif is characterized by a sleepwalking security. "For Gerd Presler the screams" winds in wide waves through landscape and figure [...] Everything is vibrating sound. "

History of origin

As with many of his central works, the scream began with a literary draft by Munch. In his violet diary under the date “Nice, January 22nd, 1892” there is the entry: “I was walking along the path with two friends - the sun was setting - the sky suddenly turned bloody red - I felt a touch of sadness - I was standing , leaned against the fence, dead tired - I looked over [...] the flaming clouds like blood and sword - the blue-black fjord and the city - My friends went on - I stood there trembling with fear - and I felt something like a big, infinite one Scream through nature ”. Numerous deletions and corrections show that Munch struggled with the formulation of the text. More than ten other copies of the prose poem in different versions were found in his estate. Elsewhere he continued: “I felt a loud scream - and I really heard a loud scream ... The vibrations of the air made not only my eye vibrate, but also my ear - because I really heard a scream. Then I painted the picture The Scream . "

Munch's diary entry refers to an experience the painter had during his summer stay in Norway. Munch was walking on the Ljabroveien road , which led from Oslo to Nordstrand on the east coast of the Oslofjord , when, according to Hans Dieter Huber, he "apparently suffered a moment of personal despair". In the text, he made nature a kind of resonance space for his personal feelings: the blue-black fjord stands for his secrets, the blood-red sky for the pain felt. A first sketch of the motif can already be found in the sketchbook 1889/90. The first completed implementation is the oil painting Despair , which was created in Nice in the spring of 1892 . The transformation to a scream can be traced through sketches in which the foreground figure was repeatedly changed until she finally looked out of the painting. The first pastel lacked the luminosity of the colors. Presumably because of compositional problems, Munch discarded a first draft with oil paint, turned the cardboard over and painted the picture on the reverse with oil, tempera and pastel that is now considered the main version of the motif. Munch finished the painting at the end of 1893. He had not worked on any other picture for so long before, except The Sick Child .

Edvard Munch: Despair , 1892, 92 × 67 cm, Thielska galleriet , Stockholm

Edvard Munch: Fear , 1894, 94 × 74 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

Edvard Munch: Despair , 1894, 92 × 72.5 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

Edvard Munch: Friedrich Nietzsche , 1906, 201 × 160 cm, Thielska galleriet , Stockholm

The importance that The Scream had for the Norwegian painter can be seen in the fact that in 1894 he combined two of his earlier paintings, Melancholy and Evening on Karl Johans gate , with the surroundings and the red sky of the scream . In fear , an anonymous mass of people, dressed in black as at a funeral, faces the viewer with wide eyes. Heller sees city dwellers alienated from nature in them and considers the composition, which Munch later also processed in a lithograph and a woodcut , to be much more successful than the transfer of the Jappe Nilssen figure from the beach out of melancholy to the bridge of the scream , which the intensity both predecessors are missing. The scream was also one of the first works in 1895 that Munch, who discovered printmaking for himself late , implemented as lithography. Then the painter finished with the motif, apart from individual coloring of the prints. Only in 1910 (the dating of the picture was long disputed) did he return to the picture in connection with the sale of the first tempera version to the National Gallery and paint a copy for his own use, as he did with many of his major works did. The portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche from 1906 can be seen as a kind of antithesis to the scream , in which the philosopher, as a figure of identification for the painter, looks upright and calmly at the landscape - a self-portrait of Munch as he wished to be, in contrast to the true portrait of his Soul life in scream .

interpretation

Landscape as a mirror of the soul

Reinhold Heller is not surprised that Munch did not have the vision that led to the picture The Scream in the south of France or Berlin, where he stayed for a long time at the beginning of the 1890s, but in the landscape of his youth, the fjords around Kristiania, today Oslo. For Munch, this landscape was so charged with spirituality and his emotional experience that Munch could only feel the scream of nature here. Munch's artistic training was shaped by the naturalism prevalent in Scandinavia , which required a faithful representation of reality. In the visual implementation of his vision, he was now faced with the decision to reproduce the general visual impression of the sunset on that day or his very personal vision of it. He chose to stay true to his vision. The sky and the landscape of his painting have their origin in real meteorological and topographical conditions, but they are transformed into the mirror of his personal emotional life. For Munch, objective reality lies in his feelings, and the outside world becomes the expression of his emotional state. Matthias Arnold puts it: "Here the environment is a mirror of the psychic, the outer landscape expresses the inner landscape."

To find this expression of his inner experience, what a tedious process for the painter. The forerunner of the scream , the painting Despair from 1892, which was originally exhibited as a mood at sunset , is still made with a light, impressionistic brushstroke and shows a neo- romantic scene with a melancholy brooder. It was only when this figure was changed, its human anatomy dissolved and its focus turned from nature to the viewer, that Munch changed the mood of his picture, took away the aura of sadness and Weltschmerz and transformed it into the incarnation of scream. August Strindberg described this cry as a "cry of horror before nature, which blushes with anger and is preparing to speak through storm and thunder to the foolish little beings who imagine they are gods without being like them."

Stanisław Przybyszewski wrote about Munch's work: “His landscape is the absolute correlate to the naked feeling; every vibration of the nerves exposed in the highest ecstasy of pain is converted into a corresponding color sensation. Every pain a blood-red stain; every long howl of pain a belt of blue, green, yellow spots; unbalanced, brutal side by side, such as the boiling elements of nascent worlds in wild creative fervor. […] All previous painters were painters of the external world, they clad every feeling they wanted to portray in some external process, they only let every mood arise indirectly from the external environment. The effect was always indirect through the means of the external world of appearances. […] Munch has completely broken with this tradition. He tries to represent mental phenomena directly with color. He paints as only a naked individuality can see, whose eyes have turned away from the world of appearances and turned inward. His landscapes are seen in the soul, perhaps as images of a Platonic anamnesis ”. Munch himself summed this up as follows: "I don't paint what I see - I paint what I saw."

Love, loss of self and psychosis

From the beginning, The Scream was an important part of Munch's life frieze , the compilation of his central works on the themes of life, love and death. In its first presentation in December 1893, Munch called the frieze a study for a series “Love” , and The Scream formed the end of a narrative arc that spanned from the first attraction of the sexes to the fear of life. In the Schrei , it is the landscape that for Munch is charged with the erotic power of femininity. The lines of the landscape, especially in the lithography, remind Reinhold Heller of female hair, which Munch often used as a symbol for the overwhelming, absorbing power of femininity, for example in the vampire motif . In the scream , too, the sexless, emasculated figure in the foreground is lost in the landscape and with its crooked skull and torso absorbs the curves of the landscape. Not only does it lose its human form, but also its identity. It is approaching death, for which Munch had chosen the symbol of the road into nowhere early on in his work.

The inscription "can only have been painted by a mad man" in the red sky of the picture refers to Munch's own struggles against self-dissolution. He suffered from agoraphobia and recurrent schizoid psychoses caused by excessive alcohol consumption. His high sensitivity to sensual stimuli up to the synaesthetic sensation of the “scream in nature”, which became the starting point for the painting, reinforced his fear of losing his identity. For Munch, painting became a kind of therapy with which he could bring his fears under control and shield himself from the stimuli of the outside world. For Reinhold Heller, more than any other of his works, Der Schrei is a symbol of Munch's struggle for the integrity of his ego. Curt Glaser judged: "Munch's composition always has something of the urgency of an obsession that impresses itself on the viewer's possession of forms, as it haunted the artist himself for years and decades."

Beginning of Expressionism

Oskar Kokoschka verdict: "With the picture The Scream was Expressionism born." Hilde Zaloscer sees the concept of 'Scream' as a keyword in art direction and Munch's painting as "Signum an era" by a new function of art and a completely new Artificial language signaled and the basic topos of the following century, which laid down fear of the world. In the style of an “open work of art”, the figure in the scream is aimed directly at the viewer, the subject merges with the object of the scream and thus eliminates the classic function of a representation in the sense of a narrative in a fixed space-time structure: “Here does not a certain person scream, here one-for-all screams his existential fear, his fear of life and takes us into the great fear. ”At the same time, Munch's image remains caught in the aura of the inexplicable and uncanny, the image becomes a metaphor that no longer rationally explainable world of modernity. For Zaloscer, the creative implementation contains a basic element of the 20th century, the "sudden" that triggers a shock in the viewer, as well as an "aesthetics of the ugly" with which Munch broke with classic laws such as that of Lessing , which in Laocoon rejected the scream as a motif in the fine arts.

For Matthias Arnold, Der Schrei is “the ultimate expressionist image”. Hardly any later picture of this art movement has ever again achieved its mixture of tension, dynamism and depth of feeling, hardly have form and content matched so closely again later. The picture is thus "the prelude to Expressionism and at the same time already the exhaustive anticipation of its main intentions and possibilities." In its restless flow of lines, influenced by Vincent van Gogh's Starry Night four years earlier, Munch went beyond Expressionism to work like The Screaming Pope Francis Bacons and Existentialism . The scream is not only Munch's most famous, but also his most expressive work, the expressiveness of which he no longer surpassed in his later works.

Theories and studies

The exact position of the painting was located on Ekeberg Hill in Oslo by the astronomer Donald W. Olson . It is located approximately 2000 feet west of the official marker on the Vallhalveien road , which was only built in 1937. The change of a background color from light-orange to dark-red-orange leads Olson's investigation back to the eruption of Krakatau in 1883 and the worldwide change in the color of the sky. In contrast, a group of researchers from the University of Oslo hypothesized in April 2017 that the unusual sky design could have been the representation of so-called mother -of- pearl clouds .

In 1978 the art historian Robert Rosenblum first made a connection between the central figure of the picture and a pre-Inca mummy exhibited today in the Musée de l'Homme . The same is said to have inspired Paul Gauguin to create various figures in over twenty works of art. The corpses, crouching in the fetal position, appear to be "screaming" because of the slack muscles in their jaws.

The Norwegian psychiatrist and author Finn Skårderud sees a connection between the suicide of the Norwegian painter Kalle Løchen on November 20, 1893, who was for a time one of Munch's best friends, and the screaming works.

The tempera version of the National Museum in Oslo was examined by Norwegian and British scientists in 2010. The analysis of the painting materials showed that Munch used the usual pigments of his time. The pigments cadmium yellow , chrome oxide green , cinnabar and synthetic ultramarine were detected in this picture . White spots on this version have long been mistaken for bird droppings or splashes of paint. Investigations by the University of Oslo in 2016 showed that it was candle wax, which probably accidentally dripped onto the picture in the studio.

Younger story

Theft 1994

On February 12, 1994, thieves stole the 1893 tempera version from the Norwegian National Gallery. The police were able to secure the picture three months later; the perpetrators were later sentenced to several years in prison.

Theft 2004

On August 22, 2004, masked perpetrators stole the Tempera version from 1910 and a version of Madonna during an armed robbery on the Munch Museum . In 2006, six of the presumably seven perpetrators were caught in the investigation because of the simultaneous and probably connected with the Munch robbery on a money depot in Stavanger . On February 14, 2006, the trial began in Oslo . All seven suspects come from the Tveita milieu, named after a district in Oslo, which is home to Norwegian organized crime groups . The defendants were sentenced to long prison terms for the attack on the money transport and a police murder. According to the Dagbladet on August 22, 2006, criminal David Toska, who was sentenced to 19 years in prison, offered the pictures to the police in exchange for pardon as part of an appeal process.

On August 31, 2006, the Norwegian police were able to secure the two Munch pictures during a raid. According to the first reports, the condition of the pictures was better than expected. The Munch Museum showed both pictures to the public between September 27th and October 1st, 2006, in a damaged, unrestored condition "because of the great interest". This exhibition attracted over 5500 visitors.

In December 2006 the Munch Museum announced that the scream had been so destroyed by the consequences of the robbery that a complete restoration was not possible. Above all, moisture damage on the lower left edge is difficult to repair. In order to prepare for the best possible recovery, samples were sent to external laboratories for analysis. The analysis did not give a clear result. It is very likely that the damage was caused by water and not by exposure to chemicals. In addition, there was color chipping around the entire edge of the picture and partly in the picture itself. The color chipping has not yet been closed and can still be seen in the picture.

The restored picture has been presented to the public again since May 23, 2008 as part of a special exhibition, with a completely new catalog raisonné presented by Munch and the date of creation of the picture corrected to 1910. In 2018 the Munch Museum had a new frame made for the painting.

Auction 2012

The pastel version from 1895 was sold at Sotheby’s auction in New York on May 2, 2012 for US $ 119,922,500. That was the highest price for a work of art ever achieved at an auction . The buyer of the picture was New York businessman Leon Black , who sits on the board of directors of the Museum of Modern Art . The painting was shown there from October 24, 2012 to April 29, 2013.

reception

The Norwegian art historian Frank Høifødt described the scream as "a modern icon" that is reprinted thousands of times every day. Andy Warhol made a number of screen prints after lithographs by Munch in 1984 , including The Scream . He converted the well-known template into a commercial object that can be reproduced in mass production. The Icelander Erró alluded to the occupation of Norway during the Second World War with The Second Cry . Munch's scream adorns countless everyday objects and was picked up, depicted or parodied in many media of popular culture. Among others, the mask of the killer in the are Scream - Horror film series or the appearance of fictitious confessor of silence in the television series Doctor Who the person's face modeled on the image. The motif has even found its way into the digital zeitgeist: The emoji ? (U + 1F631, “face screaming in fear”) is based on Munch's scream .

Graffiti in Gdansk , 2007

Picture by Rob Scholte on the Bertramstrasse picture wall in Hanover , 2011

literature

- Gerd Woll: Edvard Munch - complete paintings. Catalog raisonné. 1. 1880-1897 . Thames & Hudson, London 2009

- The Scream 1893, no.332

- The Scream 1893, no.333

- The Scream 1895, no.372

- The Scream 1910 ?, No. 896

- Stanisław Przybyszewski (ed.): The work of Edvard Munch . S. Fischer, Berlin 1894

- Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch: "The Scream" . Viking Press, New York 1973 ISBN 0-7139-0276-0

- Hilde Zaloscer : "The Scream". Sign of an era. The expressionist century. Fine arts, poetry and prose, theater . Brandtstätter, Vienna 1985 ISBN 3-85447-104-1

- Walter Olma: Stanisław Przybyszewski's later novel “The Scream” , in: Stanisław Przybyszewski: Works, Notes and Selected Letters. Vol. 9: Commentary Volume. Edited by Hartmut Vollmer. Igel, Paderborn 2003 ISBN 3-89621-173-0 pp. 111-156

- Antonia Hoerschelmann: The scream , in: Klaus Albrecht Schröder (Hrsg.): Edvard Munch - theme and variation . Hatje Cantz , Ostfildern 2003 ISBN 3-7757-1250-X p. 245 (description of images)

- Poul Erik Töjner / Bjarne Riiser Gundersen: Skrik. Histories om et bilde , Oslo 2013

- Hans Dieter Huber : Edvard Munch. Dance of life . Reclam, Stuttgart 2013 ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 pp. 72-81

- Gerd Presler : "The Scream". End of a mistake. eBook. XinXii-GD Publishing, Karlsruhe 2015

- Gerd Presler: Der Urschrei , in: Weltkunst , June 2019, pp. 34–37

Web links

- Video guide about the painting at the artinspector

- BBC report on Munch / The Scream (with pictures, English)

- Brief introduction to Munch's work

- Comparison of the four versions (Norwegian)

- The Scream (1895) at Sotheby's 2012

- Edvard Munch, 'The Scream' , ColourLex

Individual evidence

- ^ The Scream, 1893 in the National Museum Oslo .

- ↑ Gerd Presler even sees a fifth version of the picture that has been ignored for a long time, see: Gerd Presler: Der Schrei, Ende einer Errtums , Selbstverlag, Karlsruhe 2015, Chapter 9.

- ↑ Edvard Munch: The Scream at Sotheby’s .

- ^ Gerd Woll: The Complete Graphic Works . Orfeus, Oslo 2012, ISBN 978-82-93140-12-2 , no.38 .

- ↑ Edvard Munch at KODE Art Museums of Bergen.

- ↑ Gerd Presler: Der Schrei, Ende einer Errtums , self-published, Karlsruhe 2015, Chapter 16, 20.

- ↑ a b c Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , p. 68.

- ^ Atle Naess: Edvard Munch A biography. Gyldendal Norsk Forlag, 2004, p. 153

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , p. 45.

- ↑ Arne Eggum , Guido Magnaguagno: The Scream, 1893 . In: Edvard Munch . Museum Folkwang, Essen 1988, without ISBN, cat. 30.

- ^ Hans Dieter Huber: Edvard Munch. Dance of life . Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , p. 80.

- ^ Hans Dieter Huber: Edvard Munch. Dance of life . Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , pp. 76, 78.

- ^ Hans Dieter Huber: Edvard Munch. Dance of life . Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , pp. 80-81.

- ↑ Reinhold Heller: Making a Picture Scream . In: Sotheby's catalog devoted to the Scream, 2012. Quoted from: Gerd Presler: Der Schrei, Ende einer Errtums , self-published, Karlsruhe 2015, chapter 12.

- ^ Anni Carlsson: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Belser, Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 3-7630-1936-7 , pp. 42-44.

- ^ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch: The Scream . Viking Press, New York 1973, ISBN 0-7139-0276-0 , pp. 117-119.

- ↑ Gerd Presler: The Scream, End of an Error , self-published, Karlsruhe 2015, Chapter 15.

- ^ Hans Dieter Huber: Edvard Munch. Dance of life . Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , pp. 72, 74.

- ^ Uwe M. Schneede : Edvard Munch. The early masterpieces . Schirmer / Mosel, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-88814-277-6 , p. 50.

- ^ Hans Dieter Huber: Edvard Munch. Dance of life . Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , p. 72.

- ^ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch: The Scream . Viking Press, New York 1973, ISBN 0-7139-0276-0 , p. 72.

- ^ Hans Dieter Huber: Edvard Munch. Dance of life . Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , pp. 72-74.

- ↑ Gerd Presler: Der Schrei, Ende einer Errtums , self-published, Karlsruhe 2015, chapter 4.

- ^ Hans Dieter Huber: Edvard Munch. Dance of life . Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , pp. 75-80.

- ^ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch: The Scream . Viking Press, New York 1973, ISBN 0-7139-0276-0 , p. 85.

- ↑ Gerd Presler: The Scream, End of an Error , self-published, Karlsruhe 2015, Chapter 15.

- ^ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch: The Scream . Viking Press, New York 1973, ISBN 0-7139-0276-0 , pp. 95-99.

- ^ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch: The Scream . Viking Press, New York 1973, ISBN 0-7139-0276-0 , pp. 73-75.

- ^ A b Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , p. 46.

- ^ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch: The Scream . Viking Press, New York 1973, ISBN 0-7139-0276-0 , pp. 71, 78-80.

- ^ Stanislaw Przybyszewski: The work of Edvard Munch . In: Critical and essayistic writings . Igel Verlag, Paderborn 1992, ISBN 3-927104-26-4 , pp. 156-157.

- ↑ Quoted from: Uwe M. Schneede: Edvard Munch. The early masterpieces . Schirmer / Mosel, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-88814-277-6 , p. 13.

- ^ Hans Dieter Huber: Edvard Munch. Dance of life . Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , p. 66.

- ^ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch: The Scream . Viking Press, New York 1973, ISBN 0-7139-0276-0 , pp. 66, 90.

- ^ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch: The Scream . Viking Press, New York 1973, ISBN 0-7139-0276-0 , pp. 87-90.

- ↑ Curt Glaser : The graphic of the modern times (1922). Quoted at night: Anni Carlsson: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Belser, Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 3-7630-1936-7 , p. 44.

- ^ Hilde Zaloscer: The repressed expressionism . In: Mitteilungen des Institut für Wissenschaft und Kunst 4/1986, pp. 144–156 ( pdf ).

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , pp. 45-47.

- ↑ Donald W. Olson: Celestial Sleuth. Using Astronomy to Solve Mysteries in Art, History and Literature . Springer, New York 2014, ISBN 978-1-4614-8403-5 , pp. 78-82.

- ↑ See also Bob Egan: The Scream by Edvard Munch . On: www.popspotsnyc.com.

- ↑ Donald W. Olson, Russell L. Doescher, and Marilynn S. Olson: The Blood-Red Sky of the Scream . In: APS News ( American Physical Society ) 13 (5). dated December 22, 2007.

- ↑ Axel Bojanowski : Weather researchers provide a new explanation for Munch's "The Scream". Spiegel Online, April 24, 2017, accessed on the same day.

- ↑ Ziemendorff, Stefan (2015). "Edvard Munch y la momia de un sarcófago de la cultura Chachapoya". Cátedra Villarreal, No. 2, Vol. 3

- ↑ Ziemendorff, Stefan (2014). "La momia de un sarcófago de la cultura Chachapoya en la obra de Paul Gauguin". Cátedra Villarreal, No. 2, Vol. 2

- ↑ Finn Skårderud: Munchs selvmord ( Memento from January 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) blaafarveverket.no, 2013 (accessed March 12, 2019)

- ↑ Brian Singer, Trond Aslaksby, Biljana Topalova-Casadiego and Eva Storevik Tveit, Investigation of Materials Used by Edvard Munch, Studies in Conservation 55, 2010, pp 1-19

- ^ Edvard Munch, 'The Scream', ColourLex

- ↑ But no bird droppings - spectrum of science

- ^ Basler Zeitung : "Stolen Munch paintings found after two years" (August 31, 2006) ( Memento from September 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Munch Museum : "Besøkstall for utstilling av Skrik og Madonna" (October 2, 2006)

- ↑ Munch Museum : "Om konserveringen av Skrik og Madonna"

- ↑ nachrichten.ch May 21, 2008: "Munch's 'Scream' restored and exhibited"

- ↑ Henriette von Hellborn: A frame for the scream. In: SWR2 of May 9, 2018.

- ↑ Sales description at Sotheby's on May 2, 2012

- ↑ New York billionaire is said to have bought Munch's "Scream". In: spiegel.de. July 12, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012 .

- ↑ Munch's “Scream” went to finance manager Leon Black ( memento of the original from October 14, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Monopoly magazine for art and life July 12, 2012

- ^ Edvard Munch: The Scream at the Museum of Modern Art (English, accessed April 23, 2013).

- ↑ Gerd Presler: The Scream, End of an Error , self-published, Karlsruhe 2015, chapter 2.

- ↑ Claudia Weingartner: Warhol's surprising role models . In: Focus from June 3, 2010.

- ↑ Andy Warhol: The Scream (After Munch) at Sotheby’s .

- ^ Neven-ending Scream . In: The National of February 27, 2012.

- ↑ Munch's "Schrei" goes under the hammer. Wallstreetjournal.de, accessed on May 3, 2012 .

- ↑ Tom Oglethorpe: He's a real scream! Get ready to dive behind the sofa as Doctor Who's new enemy makes the Daleks look like Dusty Bin . In: Mail Online from April 15, 2011.

- ↑ Emoji U + 1F631 at the Unicode Consortium .

- ^ Mario Naves: Exhibition note . In: The New Criterion Vol. 35, No. June 10, 2016.