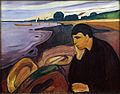

Portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche

|

| Friedrich Nietzsche |

|---|

| Edvard Munch , 1906 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 201 × 160 cm |

| Thielska galleriet , Stockholm |

|

| Friedrich Nietzsche |

|---|

| Edvard Munch , 1906 |

| Oil and tempera on canvas |

| 200 × 130 cm |

| Munch Museum Oslo |

The portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche or short Friedrich Nietzsche is a painting by Norwegian painter Edvard Munch from 1906. It is a portrait of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche , who six years earlier had died. Therefore, contrary to his usual way of working, Munch had to resort to photographs of the sitter. The picture goes back to a suggestion by Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche and is a commissioned work for the Swedish entrepreneur and art collector Ernest Thiel . It is now in the Thielska galleriet in Stockholm, which he donateddisplayed. In the same year Munch painted a second, narrower Nietzsche portrait, which remained in his possession and is shown in the Munch Museum in Oslo .

Image description

The portrait shows a larger than life Nietzsche figure as a hip image at a height of two meters. According to Reinhold Heller, the philosopher stands in a very upright, powerful pose. Hilde MJ Rognerud calls her “ mannered ”. He wears a waistcoat, tie, and long coat, all shades of dark blue. He leans against a parapet with his right arm. In three-quarter profile he looks down on the landscape. The shape of the hands shows a subsequent processing: Munch reduced the contours of the initially large hands with black and white paint. The diagonal of the railing leads upwards from the lower left corner and separates a brownish triangle from a steep perspective .

Like the steep diagonal, the yellow-red structures of the sky are reminiscent of Munch's well-known motif The Scream , but now yellow and white tones dominate, through which only a few red "stripes of fire" lick. According to Hans Dieter Huber, this leads to a much calmer, more moderate mood. The landscape below the parapet to the left is made up of strips of fields and rivers in different shades of green, yellow and blue. A white castle with three buildings can be seen in a bend in the river. Left and right behind Munch's shoulders rise blue ridges of hills that create the impression that the philosopher is growing wings.

The version from the Munch Museum is just as big as the one from Thielska galleriet, but narrower, making it appear more crowded and restless. The section of the landscape is smaller. In any case, according to Hans Dieter Huber, the landscape and the figure are only sketched “in a very lean painting style and very schematically”. The green fields are not differentiated in color, but hatched like the mountains, the indicated castle can only be guessed at. Except for the carefully designed head, Detlef Brennecke describes a hasty way of painting with partly uncleaned brushes, in which the green, blue, yellow and brown tones “shimmer through each other”, forming streaks, blobs and splashes. Nietzsche's coat and the wing-like mountain slopes have a purple tinge. In this version, the sky with its yellow and orange tones is even more reminiscent of the scream . According to Huber, it creates “a feverish and sick atmosphere [...]. Seldom has such a cold and poisonous yellow been brought to the canvas. "

interpretation

A winged Zarathustra

Munch wrote to explain his motive: “I portrayed him [Nietzsche] as Zarathustra's poet between the mountains of his cave. He stands on his porch and looks down into a deep valley. A bright sun rises over the mountains. One can imagine the place he is talking about as one where he stands in the light, but longs for the dark - but also for many other things. "Munch refers to the passage Das Nachtlied from So spoke Zarathustra :" Light am I: oh, that I would be night! But this is my loneliness, that I am girded with light. " According to Detlef Brennecke, this was one of Munch's favorite passages in Nietzsche's work, which he marked with a ribbon bookmark in his edition. It expresses an antagonism in the essence of Zoroaster and Nietzsche, who let works such as fear , the scream and despair resonate in the otherwise sublime mood of the picture .

Hilde MJ Rognerud refers to a passage from From the bestowing virtue : “And that is the great noon, since man stands in the middle of his path between animal and superman and celebrates his way to the evening as his highest hope: because it is the way to a new morning. Then the person who goes under will bless himself that he is a man who passes over; and the sun of his knowledge will stand him at noon. ”In this sense, she interprets the motif as a winged Zarathustra in a transcendent state between the animal - the originally paw-sized hands, the eagle's look with mountain wings, the serpentine river - and superman , between an existence in the “serpent valley” and an afterlife under the sun of Zarathustra.

Nietzsche's influence on Munch

With lectures by the cultural historian Georg Brandes at the University of Copenhagen in the spring of 1888, the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche became known and quickly popular in Scandinavia. The painter came into contact with Nietzsche admirers such as the Polish writer Stanisław Przybyszewski at the latest in the Berlin artist's pub Zum schwarzen Ferkel , where Munch frequented from 1892 . He wrote early writings on Munch's work and was instrumental in identifying an influence of the German philosopher in it, an interpretation that later interpreters such as Gösta Svenæus, Reinhold Heller or Jürgen Krause took over. Matthias Arnold also reports that Munch was "an enthusiastic fan and reader of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche".

Detlef Brennecke points out, however, that in Munch's notes and notes, right up to the work on the Nietzsche portrait, there is hardly any reference to the German philosopher and that in 1918 he denied any influence of “German contacts” on his life frieze. In Brennecke's assessment, Munch had no greater knowledge of Nietzsche's works, and although the portrait was composed of set pieces, he declared them to have been read only superficially. In the end the picture contradicts the dogmatics of the philosopher (e.g. his rejection of symbolism ) as well as the aesthetics of the painter (e.g. his motto “I don't paint what I see, but what I saw”), so that Brennecke both spoke of a "pseudo-munch" as well as an "anti-Nietzsche". After all, Hilde MJ Rognerud sees a “change in style” initiated by the “philosophical-religious, mysticistic Weimar milieu” in Munch's art, which can be traced in the final portrait.

Counter-image to the scream

Reinhold Heller brings into play the interpretation that Munch created an idealized self-portrait in the Nietzsche figure. The painter was always on the lookout for role models with friends, literary or historical figures, and Nietzsche's influence in his circle of acquaintances had predestined him as a figure of identification. In this respect, for him, the composition of the Nietzsche portrait not only relates formally to Munch's famous painting The Scream , as far as the design of the sky and the falling lines are concerned. Now, however, there are lines striving upwards from the bottom left to the top right, which, according to the interpretation of the 19th century, symbolize a constructive, affirmative mood.

The Scream (1893), oil, tempera and pastel on cardboard, 91 × 73.5 cm, Norwegian National Gallery, Oslo

The Scream (1910), oil and tempera on cardboard, 83 × 66 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

Instead of the fearfully crooked skull figure screaming , the Nietzsche figure in the portrait stands upright and calm, full of inner strength and self-assurance. She looks across the abyss at a landscape as if she were examining it and accepting it, without being bothered by negative thoughts and destructive premonitions. With its aura of calm and stability, according to Heller, the portrait is almost "the emotional antithesis" of the scream and reflects a dream of health that Munch, who was emotionally and health-challenged, may have cherished during these years. To a certain extent, the picture portrays the ideal self that Munch would have liked to be and with which he would have confronted life in the affirmative, compared to the true picture of his inner self in the scream .

Pictorial history

Between 1902 and 1908 Munch had two residences. He spent the summers in Norway, especially in Åsgårdstrand , and the winters in Berlin , Germany , where he was particularly successful with his art. During these years, Munch did not add any further motifs to his frieze of life, but developed into a sought-after portrait painter who resided with his clients while working on the pictures. In the spring of 1904 he traveled to Weimar for the first time for a portrait of Count Harry Kessler . Through the architect Henry van de Velde , he met Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche , the sister of the late philosopher. This in turn ensured contact with the Swedish banker Ernest Thiel , who was a great admirer of Nietzsche and had translated some of his works into Swedish. He also already owned a painting by Munch and was planning further acquisitions. The idea of a commissioned portrait financed by Thiel was born quickly, with a portrait of the sister as a by-product.

Edvard Munch: Harry Graf Kessler (1906), oil on canvas, 200 × 84 cm, Neue Nationalgalerie , Berlin

Edvard Munch: Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche (1906), oil on canvas, 115 × 80 cm, Thielska galleriet , Stockholm

Edvard Munch: Ernest Thiel (1907), oil on canvas, 191 × 101 cm, Thielska galleriet , Stockholm

In order to depict Nietzsche, Munch had to be content with photographs and artistic representations that his sister made available to him. These included, for example, the photo series of the ailing Nietzsche by Hans Olde and the resulting etching, as well as a photograph of Nietzsche with propped head by Gustav Adolf Schultze . The latter led in the first sketches to a huddled Nietzsche who, like the silhouette in Nacht in Saint-Cloud, sits at the window or a Jappe-Nilssen figure out of melancholy , which was moved into the interior of Munch's melancholy sister Laura, whose portrait is also melancholy is titled.

Hans Olde : Small Nietzsche Head (1900), etching, Thielska galleriet , Stockholm

Gustav Adolf Schultze : Friedrich Nietzsche (1882), photography

Edvard Munch: Night in Saint-Cloud (1890), oil on canvas, 64.5 × 54 cm, Norwegian National Gallery , Oslo

Edvard Munch: Melancholie (1894–96), oil on canvas, 81 × 100.5 cm, Kunstmuseum, Bergen

Edvard Munch: Melancholie (Laura) (1911), oil on canvas, 120 × 125 cm, Stenersen Museum , Oslo

The artistic breakthrough only meant the decision to no longer portray Nietzsche realistically, but abstractly as a figure of his own works, namely as Zarathustra. Munch described: “I […] decided to paint it monumentally and decoratively. I do not think that it would be right of me to depict him illusory [sic!] - since I have not seen him with my outer eyes. I have therefore emphasized my point of view by painting it a little larger than life. ”Which of the two painting versions was created first after various sketches has not yet been finally clarified. In Gerd Woll's catalog raisonné from 2008, for example, the version of the Munch Museum follows the commissioned work for Thiel, see the list of paintings by Edvard Munch . Proponents of this thesis argue that Munch often copied important motifs for his own use after a sale. However, Detlef Brennecke justifies with Munch's own notes and the sketchiness of the version of the Munch Museum that this was only a preliminary study and that Munch made conscious changes towards a calmer, more optimistic picture mood.

After receiving the painting, Ernest Thiel was “completely enchanted by this impressive portrait - how the prophet and man merge into one. That's exactly how I wished to have it one day! They couldn't have done it better. ”Munch thanked him with the conviction:“ I believe that the picture has helped me artistically. ”Above all, it brought him a new sponsor who acquired more of his pictures as well as his own portrait in So that Munch retrospectively stated: "Thiel's purchases gave me economic freedom for two years when I needed money most."

The artistic value of the commissioned work was already controversial in contemporary reviews. For example, in 1907 Tor Hedberg praised “a synthesis of personality or, better said, the idea of personality” in Svenska Dagbladet . This was followed by other critics who recognized the “prophetic, superhuman” (Peter Krieger), “the expression of infinite abandonment and lurking madness” ( Otto Benesch ) or “the hopeless loneliness and confusion of the failed Titan” ( Paul Ferdinand Schmidt ), “A modern demonic genius of melancholy” ( Josef Adolf Schmoll called Eisenwerth ). Emil Heilbut, on the other hand, criticized as early as 1906: “The picture has acquired something heraldic ”, and he missed “that which was created naturally everywhere.” Josef Paul Hodin found “a rigidity that was unusual in Munch”. For Hans Gerhard Evers , “Nietzsche had been made into a bourgeois popular preacher like an Ibsen drama ”. And Arne Eggum found: "Measured by Munch's other standards, this was an unusually conventional job".

While working on the painting, Munch also created a lithograph in red and gray-violet of Nietzsche's head in front of two ridges and a wavy patterned sky with a solar disk. The Nietzsche figure reappeared again in 1909 in a painting The Genies , where he was depicted together with Ibsen, Socrates and other thinkers who were neither named nor recognizable. According to Detlef Brennecke, however, the image motif did not go beyond a “rough version”.

literature

- Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , pp. 76-78.

- Detlef Brennecke: The Nietzsche portraits of Edvard Munch. Berlin Verlag Arno Spitz, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-8305-0073-4 .

- Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work. Prestel, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , p. 115.

- Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch: The Scream. Viking Press, New York 1973 ISBN 0-7139-0276-0 , pp. 96-99.

- Hans Dieter Huber : Edvard Munch. Dance of life. Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , pp. 123-127.

- Anneliese Plaga: Speech Images as Art Friedrich Nietzsche in the Imagery of Edvard Munch and Giorgio de Chirico , Riemer 2008, ISBN 978-3-496-01388-4

- Hilde MJ Rognerud: Nietzsche, Zoroastrian and winged. Edvard Munch's visions of a modern philosopher. In: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte , Vol. 77, No. 1/2014, pp. 101–116.

Individual evidence

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , p. 77.

- ↑ a b Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch: The Scream. Viking Press, New York 1973 ISBN 0-7139-0276-0 , p. 96.

- ↑ Hilde MJ Rognerud: Nietzsche, zarathustrisch and winged. Edvard Munch's visions of a modern philosopher. In: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte , Vol. 77, No. 1/2014, p. 105.

- ^ A b Hans Dieter Huber: Edvard Munch. Dance of life. Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , pp. 126-127.

- ^ A b Hans Dieter Huber: Edvard Munch. Dance of life. Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , p. 126.

- ↑ Detlef Brennecke: The Nietzsche portraits of Edvard Munch. Berlin Verlag Arno Spitz, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-8305-0073-4 , pp. 45-46.

- ↑ Hilde MJ Rognerud: Nietzsche, zarathustrisch and winged. Edvard Munch's visions of a modern philosopher. In: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte , Vol. 77, No. 1/2014, p. 107.

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche: The night song . In: Thus spoke Zarathustra . Project Gutenberg-DE .

- ↑ Detlef Brennecke: The Nietzsche portraits of Edvard Munch. Berlin Verlag Arno Spitz, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-8305-0073-4 , p. 65.

- ↑ Friedrich Nietzsche: Of the virtue giving . In: Thus spoke Zarathustra . Project Gutenberg-DE .

- ↑ Hilde MJ Rognerud: Nietzsche, zarathustrisch and winged. Edvard Munch's visions of a modern philosopher. In: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte , Vol. 77, No. 1/2014, pp. 106-107.

- ↑ Detlef Brennecke: The Nietzsche portraits of Edvard Munch. Berlin Verlag Arno Spitz, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-8305-0073-4 , pp. 9, 17-21.

- ^ A b Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , p. 78.

- ↑ Detlef Brennecke: The Nietzsche portraits of Edvard Munch. Berlin Verlag Arno Spitz, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-8305-0073-4 , pp. 21, 65-71.

- ↑ Hilde MJ Rognerud: Nietzsche, zarathustrisch and winged. Edvard Munch's visions of a modern philosopher. In: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte , Vol. 77, No. 1/2014, p. 116.

- ↑ a b c Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work. Prestel, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , p. 115.

- ↑ a b Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch: The Scream. Viking Press, New York 1973 ISBN 0-7139-0276-0 , pp. 96, 99.

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , pp. 75-76.

- ^ Hans Dieter Huber: Edvard Munch. Dance of life. Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , p. 124.

- ↑ Detlef Brennecke: The Nietzsche portraits of Edvard Munch. Berlin Verlag Arno Spitz, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-8305-0073-4 , pp. 23, 25.

- ↑ Nietzsche sittende ved vinduet (1905) at the Munch Museum .

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche (1905/06) at the Munch Museum Oslo .

- ↑ Detlef Brennecke: The Nietzsche portraits of Edvard Munch. Berlin Verlag Arno Spitz, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-8305-0073-4 , pp. 28-29.

- ↑ Detlef Brennecke: The Nietzsche portraits of Edvard Munch. Berlin Verlag Arno Spitz, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-8305-0073-4 , pp. 29, 39, 42.

- ^ Nietzsche (1906) at the Munch Museum Oslo .

- ↑ Nietzsche stående i landskap (1906) at the Munch Museum .

- ↑ Detlef Brennecke: The Nietzsche portraits of Edvard Munch. Berlin Verlag Arno Spitz, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-8305-0073-4 , pp. 45-49.

- ↑ Detlef Brennecke: The Nietzsche portraits of Edvard Munch. Berlin Verlag Arno Spitz, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-8305-0073-4 , p. 50.

- ↑ Detlef Brennecke: The Nietzsche portraits of Edvard Munch. Berlin Verlag Arno Spitz, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-8305-0073-4 , pp. 52-55.

- ^ Print one , two and three of the lithograph Friedrich Nietzsche (1906) at the Munch Museum Oslo .

- ↑ Detlef Brennecke: The Nietzsche portraits of Edvard Munch. Berlin Verlag Arno Spitz, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-8305-0073-4 , p. 52.

- ↑ Geniene: Ibsen, Nietzsche og Socrates (1909) at the Munch Museum .

- ↑ Detlef Brennecke: The Nietzsche portraits of Edvard Munch. Berlin Verlag Arno Spitz, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-8305-0073-4 , p. 68.