Harry Graf Kessler

Harry Clemens Ulrich Kessler , from 1879 von Kessler , from 1881 Graf von Kessler , commonly known as Harry Graf Kessler (born May 23, 1868 in Paris , † November 30 or December 4, 1937 in Lyon ) was a grown up in France and England German art collector , patron , writer , publicist , pacifist and diplomat . His diaries (from 1880 to 1937), which stretched over 57 years from the German Empire to the time of National Socialism, are important contemporary testimonies.

In the era of Wilhelminism , Kessler emerged as a sponsor of the Berlin Secession and co-founder of the German Association of Artists . Apart from brief episodes during and after the First World War , his ambitions in the diplomatic service remained unfulfilled. In the November Revolution of 1918, Kessler sought the proximity of influential independent Social Democrats and earned the nickname “the red count”, but became a member of the German Democratic Party and in the course of the 1920s an avowed supporter of the Weimar Republic .

Kessler's alternative concept to the League of Nations received broad support, especially from peace movements, and made him one of the leading representatives of organized pacifism . The award-winning products of the Weimar Cranach press belong to the artistically significant part of his legacy. With the biography of Walther Rathenau , Kessler succeeded in providing a fundamental representation . This was one of the extremely diverse personal acquaintances of Harry Graf Kessler with prominent contemporaries recorded in the diaries.

Career

"Kessler was on the road all his life and changed stays without the pain of separation, it happened that different people wanted to see him in Paris and London at the same time ." In fact, Harry Kessler was already at home in three countries as a teenager, namely in France and Great Britain and Germany.

Family constellations

On her mother's side, Kessler had Irish-British roots, as Alice Harriet Countess Kessler was the daughter of Henry Blosse-Lynch, an officer in the Royal Navy who had risen to command the Anglo-Indian fleet in Bombay . The main identification figure among his ancestors was the young Harry but his great-grandfather of Scottish origin, Robert Taylor, who (according to family tradition) had made himself the "Viceroy of Babylonia " by military means , but also had literary talent and the archaeological excavations started under his predecessor Mesopotamia continued successfully. "Political power in connection with prehistoric excavations represented the noblest form of rule in the 19th century."

On the other hand, the son did not appreciate the profitable banking business of his father Adolf Wilhelm Kessler , a descendant of the theologian and reformer Johannes Kessler (around 1502–1574) from St. Gallen : “It is a dreadful idea to think you're just a money -making machine in life ”. The parents got to know each other in Paris, where Adolf Wilhelm ran the branch of a Hamburg bank. Mother Alice, who was born in Bombay, came to live with Pietist relatives in Boulogne-sur-Mer as a child and, after the wedding in 1867, ran a salon in Paris in which she occasionally presented herself as a mezzo-soprano . As a novelist, she had her own income under a pseudonym.

Multilingual training course

The home education began for ten-year-old Harry in a Parisian half boarding school, which he not only remembered as staring with dirt, but also caused two deaths. The family doctor urgently advised a change of milieu.

Harry began his diary entries in English at the age of twelve, just before switching to a boarding school in Ascot in the south of England , when he was on vacation with his parents in Bad Ems in the summer of 1880 . This was also where the boy met Kaiser Wilhelm I. He had met Harry's mother in 1870 and stayed in contact with her throughout his life. The rumors about a love affair went as far as the allegation that Harry himself was conceived by the emperor. Harry Graf Kessler rejected this allegation as “foolish chatter” all his life, pointing out that his mother and the emperor only met personally after his birth. When Harry's younger sister Wilma Kessler (1877–1963) (married: Wilma Marquise de Brion) was born in 1877, the Kaiser took over the sponsorship. The children were allowed to address the emperor as "uncle". Adolf Wilhelm Kessler was raised to hereditary nobility by Wilhelm I in 1879 and to hereditary count by Heinrich XIV., Prince Reuss junior line in 1881 .

After initial difficulties in the aristocratic environment of the boarding school in Ascot, which even resulted in a suicide attempt, Harry finally took a step in the new environment in view of the opportunities for sport and singing and in retrospect noted appreciatively that he could not remember "that anyone ever lied". It was all the harder for him in 1882 that after two years in Ascot his father suddenly ordered him to the Hamburg Johanneum - his own former school. Literature, theater and music from Johann Sebastian Bach to Richard Wagner became Harry's preferred areas of interest. He passed his Abitur in 1888 as the best in his class.

This was followed by a three-year law degree in Bonn and at the University of Leipzig , during which Kessler also attended extensive lectures in other subjects. He deepened classical philology with Hermann Usener , archeology with Reinhard Kekulé , art history with Anton Springer and psychology with Wilhelm Wundt . Afterwards he had the support of his father when he went on a one- year trip around the world as a one-year volunteer before his military service year .

World traveler

On December 26, 1891, Kessler embarked in Le Havre on Normandy for New York . Harry was met by his father on the New York quay and soon introduced to the local business community. The traineeship in a law firm arranged by the father did not induce the son to stay, nor did the visit to the father's paper mill in the Canadian forests on the Saint-Maurice River , which degrade "the gods of the past to servants and tools".

Kessler traveled through the south of the USA to San Francisco , from where it was to take a three-week boat trip to Yokohama . He experienced Japan less traditionally isolated than expected; the adaptation to European clothing, for example, appeared to him partly unworthy. In the Malaysian jungle he felt for the first time that he was in a place where he would like to live forever; but he notes the fear in his diary: “And how long will it take for this grandiose vegetation to give way to sugar fields and tea plantations, so that the old maids at home have enough sweet throats for gall-sweet gossip? It is a cruel fate that man has to enslave or destroy everything that does not serve him, everything independent, free. "

For his part, the young Kessler did not disdain the comforts of an upscale educational trip in the style of the cavalier tours of the 17th and 18th centuries. A servant accompanied him on the long stretch from Japan to India. The return journey from India to Europe only took sixteen days, interrupted by a four-day stay in Cairo and the surrounding area.

Diplomatic candidate waiting

Harry Graf Kessler was already open to political questions and tensions in and between the countries he dealt with as a teenager and had a lasting interest in them. Because of his origins and his parents' international connections, he felt called to serve German foreign policy with his own perspective. He was already looking for connections with leading personalities at the various places where he stayed during his world tour, says Rothe: “When conducting a conversation, he is concerned with background information that would have to be taken into account in diplomatic work. If the capacities, which often happens, cannot be spoken immediately, the otherwise restless patient patiently accepts waiting times. "

He did his one-year military service , which began in 1892 immediately after the world tour, with the 3rd Guards Uhlan Regiment in Potsdam and thereby gained access to the Prussian officer corps . Within a short time he was frequenting “first houses” and was valued as a “courteous table gentleman” and a good dancer. His relationship with the southern German Otto von Dungern-Oberau , which he began during his time in Potsdam, was determined by a violent infatuation , which ended after three and a half years with his marriage. Kessler and von Dungern remained friendly afterwards until von Dungern turned to National Socialism .

In the meantime, Kessler had completed his law studies including doctorate in 1894 and then began his legal clerkship. He took his time until October 1900 with the assessor exam, with which he had the chance of an administrative or diplomatic career. Two attempts in 1894 and 1897 to be recommended for a post in the Foreign Office by Chancellor Chlodwig zu Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst , who had previously been a frequent guest to the Kesslers as the German ambassador in Paris , failed. Mother Alice, widowed since 1895, did not think much of such a career for her son anyway and instead supported Kessler's commitment to art and culture.

Art lover

Bored of legal matters and not accepted into the diplomatic service, the young Kessler, who was not dependent on professional income, looked for suitable fields of activity. The art and cultural life of his epoch became an essential part of Harry Graf Kessler's life. He proved to be a generous sponsor of numerous artists, especially in the early stages of their careers, and in cooperation with them he pursued his own lofty plans.

Pioneering Pan

A fellow student of Kessler's student days, Eberhard von Bodenhausen , was one of the founders of the art magazine Pan , which stood out very clearly from other such products in terms of design and price level and in which, among others, publications by Richard Dehmel , Theodor Fontane , Friedrich Nietzsche , Detlev by Liliencron , Julius Hart , Novalis , Paul Verlaine and Alfred Lichtwark . Kessler got to know the style-defining Arts and Crafts movement with its combination of art and handicraft from William Morris , whose printed works combined the fields of paper production, typography and typesetting, illustration, bookbinding and literature. When - among other things, because of a revealing lithograph by Henri Toulouse-Lautrec - there was a falling out between the supervisory board of the cooperative Pan and the publishers, who were subsequently dismissed, Kessler moved up to the supervisory board as part of an overall review. In addition, a member of the editorial committee, he developed into the driving and decisive force in the structure of Pan .

In this way, Kessler came into contact with a large number of contemporary artists in Germany and beyond. Although his personal interests were initially directed towards the currents of decadence , symbolism and impressionism , on the other hand he was also open and curious about new aesthetic experiences, was increasingly interested in impressionism and neo-impressionism and also used himself for artists, whose works did not immediately inspire him, for example when he first met Edvard Munch . In Paris it came a. on encounters with Claude Monet , Vincent van Gogh and Paul Verlaine ; Kessler established lasting connections in connection with the Pan with Henry van de Velde and Hugo von Hofmannsthal and later with Aristide Maillol .

In the fifth year of publication, the costly production of the Pan turned out to be irreversible when the customer base was too small, after a merger with the similarly quality-oriented younger magazine “Insel” (which later became the Insel Verlag ) had failed. What remained, however, was the groundbreaking impact of the standards that the Pan had set for printing and publishing houses in Germany with regard to the quality of paper and typesetting.

Artist patrons

For several decades, Kessler supported and promoted aspiring artists from the inherited fortune not only by initiating and arranging orders, as in the case of Pan , but also with orders for personal use, for example Munch, by visiting him for portraits and by acting as his model. Unlike some of his early companions, he remained open to new styles, often stimulated by contacts with their protagonists.

The acquaintance with the Arts and Crafts- inspired van de Velde, who had existed since 1897, developed into a long-term, mutual give and take, with Kessler taking care of orders and financing, but also coming up with his own suggestions and plans. So he first had his Berlin apartment on Köthener Strasse furnished by van de Velde, and later the one on Cranachstrasse in Weimar. He took part in van de Velde's “Workshops for Applied Art” and won him over to move to Berlin by making him known to art-interested circles and having his program presented.

Kessler developed a "particularly creative, but not easy friendship" with Hugo von Hofmannsthal , whom he first met in May 1898 in Berlin, when Hofmannsthal attended the premiere of his verse drama Die Frau im Fenster . During another stay in Berlin the following year, Hofmannsthal stayed with Kessler and complained about a lack of topics for drama. He asked Kessler to send him suitable material. Kessler was in his element: he kept sending books and addresses, offering topics, introductions and reading lists, and also taking critical positions on drafts.

On Aristide Maillol Kessler was by Auguste Rodin alerted, who praised the sculptor colleagues as outstanding. On Maillol's first visit to Marly near Paris, Kessler immediately acquired the figure of a crouching woman and ordered another one based on a Maillol sketch. This was shown in 1905 under the title “La Méditerrannée” in an exhibition that Maillol first received broad public approval. After that, this crouching woman stood for years as a showpiece in Kessler's Berlin apartment.

After intensive letter preparation, Kessler won Maillol and Hofmannsthal for a trip to Greece in the spring of 1908. The Kessler biographer Laird M. Easton finds it difficult to understand what may have driven Kessler to this venture: “He believed that the rough sculptor and the extremely irritable poet, accompanied by him as Cicerone , together deeply from the well of the European Would drink civilization? Kessler was firmly convinced that every serious artist and writer could only benefit from a contact with Aristide Maillol, there was no one else whose way of life came closer to that of a classical Greek. ”It turned out that his image of Greece was verbose The vacillating poet Hofmannsthal and Maillol, who had come to the source of his art and completely in his element, but taciturn Maillol did not fit together, so that in the end Kessler was only able to bring the undertaking on the edge of his strength to a somewhat light end with alternating care.

Newer in Weimar

After the end of the Pan at the beginning of the new century, Kessler was temporarily caught in a depressive orientation crisis, especially since the possibility of a change to the diplomatic service was still not available. Like other of his fellow Pan activists, Kessler was also heavily influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche and had been in contact with his sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche since 1896 , who had moved from Naumburg to Weimar with her seriously ill brother that year in order to relocate the Nietzsche archive there . She had the idea of a new, “third” Weimar associated with Nietzsche's work - after the classic “golden” era and the “silver” era associated with Franz Liszt . Preparing the ground for this now became a welcome task for Kessler. It so happened that Ms. Förster-Nietzsche campaigned at the Weimar court to bring van de Velde to Weimar in order to revive and modernize the local arts and crafts.

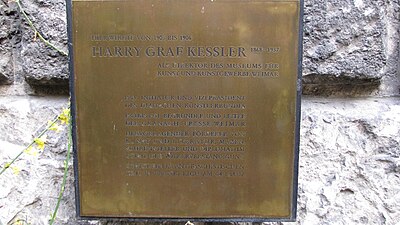

Van de Velde became head of the Weimar arts and crafts seminar in 1902 and director of the arts and crafts school he built in Weimar in 1908 , the nucleus of the Bauhaus founded in 1919 . Kessler, who combined his application for Weimar with the claim of overall responsibility for all that played a role in artistic culture in the Grand Duchy of Weimar, was established in October 1902 Chairman of the Board and in March 1903 a director of the Grand Ducal Museum of Arts and Crafts appointed . Above all, the exhibitions of modern artists he organized, where his connections to Paris and London were useful to him, met with a broad public response, such as the 1904 exhibition “Manet, Monet, Renoir, Cézanne”. With lectures on art topics at court, his own and those of good friends such as André Gide , Hofmannsthal, Gerhart Hauptmann and Rainer Maria Rilke , he specifically sought to train Grand Duke Wilhelm Ernst and court society in terms of art aesthetics and to win them over to his ideas and plans.

Kessler's ambitions for innovators in Weimar went far beyond his direct responsibility for redesigning the museum's furnishings and presentations. High-quality books, for example, should increasingly be designed as total works of art by artistically coordinating content, typography, illustration and materials. Kessler created samples of this kind with his exhibition catalogs. Since 1904, the “Grand Duke Wilhelm Ernst Edition” has been created in collaboration with Insel Verlag and the Goethe and Schiller Archive , starting with a Goethe edition, followed by other new editions of the classic. According to Easton, Kessler also became a driving force for the theater "in Germany's successful endeavors to overtake the English". His inspiration in this regard was the Englishman Gordon Craig , whose way of staging theater in a completely new way impressed him. It is true that the undertaking already initiated by Kessler to bring Craig and Hofmannsthal to the Weimar Theater failed; but he brought Craig together with Max Reinhardt , who then implemented some of his ideas in his productions. In addition, he made sure that Craig was able to make his performances known in Berlin theater circles on frequent visits to Germany. Kessler designed a "model theater" for future theater buildings; he wanted to entrust van de Velde with the design of the corresponding new building in Weimar.

Peter Grupp certifies the work of Kessler, who soon failed in his official position, to be of some sustainability: “Kessler gave important impulses during his time in Weimar. Van de Velde's work and the related Bauhaus would hardly have come about without his help. His exhibitions with the accompanying catalogs and articles contributed to the breakthrough of western modernism in Germany. [...] After all, in Weimar he acted as a mediator and stimulator, brought artists and writers from all over Europe together and brought about something like approaches to a European cultural community. "

Artist Association strategist

His Weimar duties did not prevent Kessler from other initiatives and missions to increase the radiance of his work on a national and international level. Above all , he distinguished himself as the guardian of artistic freedom against narrow-gauge art funding in the Wilhelmine era. The starting point were disputes between the Allgemeine Deutsche Kunstgenossenschaft , which is responsible for state funding of art , in which the director of the Prussian Academy of the Arts Anton von Werner set the direction, and the Berlin Secession , founded in 1898 , which Kessler supported as a sponsoring member. The latent rivalry came to a head during the planning of the German exhibition program for the 1904 World Exhibition in St. Louis . Kaiser Wilhelm II supported von Werner in marginalizing the Secessionists.

Then Max Liebermann, as President of the Berlin Secession, and Kessler in his Weimar position, set up a new collective representation of artists on a secessionist basis: the German Association of Artists . "When the founding congress of the Künstlerbund opened on December 15, 1903, almost every important artist and museum director who had anything to do with modern art was there." The place of foundation was Weimar, and the day-to-day business of the association was mainly done by Kessler. Grand Duke Wilhelm Ernst could be won as patron of the new establishment, to whom the anti-imperial component of the whole thing remained hidden.

It was then Kessler who led the push against von Werner's program for St. Louis. In the brochure “Der Deutsche Künstlerbund” he praised the new federation as a haven of artistic freedom, whose members were threatened existentially by a Berlin clique composed of moderate talents. With this, Kessler wanted to influence the members of the Reichstag who had to approve the funds for the German exhibition project in St. Louis. By persuading the oppositional ranks of the Social Democrats, the Center and the Progress Party , but also with individual representatives of National Liberals and Conservatives, Kessler was able to improve the mood of the house at the debate on 15/16. February 1904 for the cause of the artist association, so that the government finally gave in and promised to proceed differently in the future. With this, Kessler had disempowered the adversary Anton von Werner for the future and also indirectly exposed the emperor involved. But the latter turned out to be a Pyrrhic victory for Kessler : At the zenith of his influence, his Weimar base began to crumble, even if on November 15, 1905 he had a completely different view of his possibilities:

“I think about which agents I have in Germany: d. German Association of Artists, my position in Weimar including d. Prestige despite the grand ducal nonsense, the connection with the Reinhardtschen stage, my intimate relationships with the Nietzsche Archives, Hofmannsthal, Vandevelde, my close connections with Dehmel, Liliencron, Klinger, Liebermann, Ansorge, Gerhart Hauptmann, and also with the two most influential magazines Future and Neue Rundschau , and on the other hand to Berlin society, Harrachs, Richters, Sascha Schlippenbach, the regiment, and finally my personal prestige. The results are quite surprising and probably unique. No one else in Germany has such a strong position that extends in so many directions. To use this in the service of a renewal of German culture: mirage or opportunity. Surely one with such opportunities could be Princeps Juventutis . Is it worth the effort? "

Nietzsche monument planner

Kessler could only enjoy the favor of Grand Duke Wilhelm Ernst as long as the Weimar court in Berlin did not fall out of favor. This danger, however, was increasing due to Kessler's work. His Weimar partner van de Velde was also not well-liked as an artist by Wilhelm II. With Aimé von Palézieux, Kessler's predecessor as the Weimar museum manager, the relationship was so shattered by intrigue that Kessler finally challenged him to a duel ; However, Palézieux died suddenly in early 1907. In June 1906, however, Kessler had fallen out of favor with Wilhelm Ernst, who publicly snubbed him on the occasion of the third exhibition of the Künstlerbund. At the beginning of the following month, Kessler resigned from his Weimar office.

Without prejudice to this, Kessler's connection with Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche remained, who wanted to commemorate her brother on the occasion of Nietzsche's 70th birthday in 1914. She approached van de Velde for the design; She hoped that Kessler would provide organizational support and obtain the necessary financial resources. Van de Velde and with him Ms. Förster-Nietzsche originally favored a modestly dimensioned project that included the construction of a reception hall in addition to the renovation of the Nietzsche archive. When Kessler joined the preparatory committee, which he headed from March 1911, his much more far-reaching ideas came to fruition: a monumental memorial complex with a grove through which a festival road leads to a larger-than-life figure of young people - personifying Nietzsche's “ Übermenschen ” - and to one for music - and dance events should lead up certain Nietzsche temples, connected with a stadium. “All in all, the vision of a complex total work of art emerges that harmonizes architecture, landscape gardening, sculpture, dance, music and sport, elitist individuals in the performances in the temple and crowds in the stadium to praise Nietzsche and the glory of the whole person, sensuality and spirituality should unite. "

Kessler was not afraid of his own cost estimate for the monument complex of up to one million marks; because financially strong patrons like Walther Rathenau and Julius Stern gave the green light if it was possible to mobilize a broad group of supporters. 300 honorary members were to be won for the committee, including the most famous names in European cultural life, which was strongly influenced by Nietzsche at the time. Initially, Kessler faced difficulties with the initiator Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, who could not do anything with the stadium idea. According to Easton, stadium planning in the contemporary context was in the air: after the revival of the Olympic Games in Athens in 1896 , the follow-up events accompanying the World Exhibitions in Paris and St. Louis, and the latest stadium planning for the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm. “One could not have imagined a more powerful stage for the reawakening of 'Greek culture', as Kessler understood it. Here the German youth should regain the physical grace and verve that a hundred years of 'education' had driven them out. "

After Kessler had repeatedly managed to win back the initiator for his planning, the company finally failed because, on the one hand, van de Velde was unable to submit a satisfactory draft to Kessler in several attempts, and on the other hand, the costs for the last one were accepted at more than twice the original estimate and that conservative circles on the spot also raised the mood against a project in which many foreigners were involved. In 1912 the monument project began to silt up; with the outbreak of the First World War it was finally over.

Departure for your own work

With the loss of his official position in Weimar in 1905, Kessler found himself again in an orientation crisis. The promotion of artist friends remained important to him; but now he wanted to make “direct production” the main purpose of his own life: “For my mental health I need my own work under my feet.” Various book projects on painting, modern art and nationalism preoccupied him in an unsteady and sometimes escalating manner. In a letter to his sister Wilma on March 21, 1902, it was already stated: “I have the ideas; but my ideas are like poorly trained horses; they always carry me to unexpected things and places before I can give them shape; and then, then my article is quite dead and in the far distance, somewhere behind me and strewn the path with its unborn fragments. "

Even after the end of his appointment in Weimar, Kessler came to outstanding results primarily in cooperation with artist friends. In a three-day conversation with Hofmannsthal, the two men discussed and compiled the sequence of scenes for the Rosenkavalier , musically performed by Richard Strauss , from his preliminary draft . Kessler would have liked to have been listed as co-author of the libretto, but could not achieve anything more with Hofmannsthal than its distinctive attribution: "I dedicate this comedy to Count Harry Kessler, whose cooperation it owes so much."

The subject and the initiative for a new edition of this triple constellation of productive work with Hofmannsthal and Strauss came from Kessler, who proposed the adaptation of biblical material for the ballet and, with some commitment, ensured that the stage play, Joseph's legend , finally came about . At the turn of the 20th century, ballet appeared alongside opera as a modern art form. Since attending a ballet performance in 1891, Kessler has been extremely impressed: "There was no more enthusiastic fan of modern dance than Harry Graf Kessler in all of Germany." The specific reason for the joint venture with three came when the Ballets Russes came to Vienna in 1912 and choreographer Sergei Djagilews requested the material for further ballet scenarios from Hofmannsthal. Richard Strauss was little inspired by the biblical material of the failed seduction of Joseph by Potiphar's wife; he and Hofmannsthal ultimately rewarded Kessler's efforts to complete this ballet, so that Kessler experienced the premiere of his material on stage on May 14, 1914 in Paris, conducted by Strauss, and soon also had the London premiere.

After the impression of his diary entries, Kessler achieved peace and satisfaction with his own work, especially when he worked for the Cranach press (named after his home address in Weimar on Cranachstrasse). Here he built on the experiences made in the Pan and with the Herzog Ernst edition and worked with artist friends such as Maillol and Gordon Craig on books with a unique claim to perfection. The desired paper quality finally led Kessler and Maillol to produce their own paper in a specially built factory in Monval near Paris: "Kessler Maillol paper". All impurities were materially removed from it; in the most expensive variant, pure Chinese silk rag was used. The most important products of the Cranach press, however, were not to come to light until much later. The First World War also made a deep cut here.

Politicized cultural expert

Until the First World War, according to Peter Grupp, politics did not play a prominent role in Kessler's life. The ideas expressed in this regard, pronounced in Kessler manner, essentially reflected his socialization milieus and personal areas of experience: in the educated bourgeoisie, in the judicial service with the prospect of a respected position in the civil servants' class and in the officer caste determined by the code and habitus of the Prussian nobility. As a new nobleman against the background of his father's sources of money, he had to be on probation and remained vulnerable. He was “Conservative at Heart” with sympathy for the British aristocratic leadership circles since his time in Ascot. Kessler connected the advocacy of the toughest action against insurgents in the German colonies with the confession: "Civis germanus sum" .

For the time being, Kessler was unable to gain much from the democratic trends of the day. His social culture concept essentially said that the masses should be made receptive to the artistic production of the elite, because the lower classes could no longer do anything culturally positive on their own. It was only when the World War II defeated and the November Revolution broke out that Kessler changed his basic political orientation, sympathized with the USPD and became a member of the DDP . The nickname by which Kessler is known goes back to this sudden change of direction and the subsequent pacifist programmatic activities: "The Red Count".

World War Nationalist

From fin-de-siècle weariness to rousing collective war euphoria - this illusion of liberation, widespread among countless intellectuals, also gripped Kessler, who is rooted in three European cultures: “In general, these first weeks of war in our German people caused something to rise from unconscious depths that I only with a kind of solemn and serene holiness. The whole people are transformed and cast in a new form. That alone is an invaluable asset to this war; and to have witnessed it will probably be the greatest experience of our lives. ”After Kessler had brought his mother and sister to Le Havre for the crossing to safe England on July 28, 1914 because of the impending war , he volunteered for the military on July 31 Equipment in his regimental barracks. He was used as a cavalry officer of the Guard Reserve Corps and commander of an artillery ammunition column, initially in Belgium and then in Poland and later held posts as an orderly officer on the Carpathian Front and as a liaison officer to an Austrian division . In the spring of 1916 he was deployed at Verdun , noted the "madness of this mass murder" in his diary and was ordered back to Berlin soon after, possibly unnerved.

In the 1915 discussion of the objectives of the war , Kessler had spoken out about large-scale annexations in Poland, the Baltic States and on the Belgian coast and speculated on a German world empire in the English and Russian style. In September 1916 he was placed with a double assignment at the Bern embassy : on an official mission, he was supposed to organize German cultural propaganda in Switzerland , which he preferably implemented with a large number of widely spread and popular events. Unofficially, it should also be about exploring possibilities for a separate peace agreement with France. Kessler came to the conclusion that France would not allow Alsace-Lorraine to remain with Germany, and unsuccessfully advised the negotiation of a special status. Kessler had a certain amount of experience with unofficial diplomacy from pre-war times. It was mainly about the relaxation of the relationship with England , on the one hand concerning the Baghdad Railway , on the other hand an initiative in which British and German artists advocated a good relationship between the two nations in open letters, especially in view of the mutual armament of the navy . Kessler was again unofficially involved in the summer of 1918 in negotiations with a Soviet Russian delegation in Berlin about the specific implementation of the Brest-Litovsk peace .

The sudden admission of the defeat on the part of the OHL under Hindenburg and Ludendorff was a shock for Kessler, as for the German public in general, when the German ambassador to Switzerland Gisbert von Romberg informed him on October 4, 1918 about the acceptance of the 14 points Wilsons informed through Germany: “When I came from Romberg and crossed the bridge at one at night, I felt like falling into the Aare . Maybe I was just too dead inside to do it. "

Revolutionary

According to Grupp, it was a constant openness to everything new that enabled Kessler to undertake a fundamental political reorientation at the age of 50, in contrast to the majority of the imperial leadership. His turn to the left was favored by the fact that, as an international artist in circles, he had always not shied away from contacts with outsiders of the ruling system. His interest in George Grosz , Johannes R. Becher and the brothers Hellmuth and Wieland Herzfelde , for example, was much more significant than the rejection of their political views, even during wartime. The November Revolution with its accompanying phenomena and directions of development, which were confusing for contemporaries, met a curious and inspired Kessler.

During the war in Poland, he had got to know and appreciate Józef Piłsudski , who was fighting on the side of the Central Powers for the Polish cause against Russia . In 1917, Piłsudski had been taken into German custody because he had refused to take an oath of allegiance to the government installed on the German side in the Generalgouvernement of Warsaw . When the November Revolution broke out, Kessler was chosen to pick up Piłsudski from the Magdeburg prison and to arrange the fastest possible train connection to Warsaw. When the German ambassadorial post in Warsaw was soon to be filled, Kessler was also chosen and confirmed by the Executive Council of the Workers 'and Soldiers' Council in Greater Berlin on November 18, 1918. In fact, as the German envoy in Poland, Kessler only worked for a month, during which difficult negotiations had to be conducted, including the repatriation of German troops who were still in Ukraine. On December 15, pressure from Polish nationalists forced the temporary breakdown of diplomatic relations with Germany and the departure of the Kessler delegation, which had already spent very uneasy days in Warsaw.

Back in Berlin, Kessler caught the rest of the revolution as a bustling eyewitness at close range: “He kept moving towards the roar of the gunfire, only looking for protection now and then, drawing free corpse soldiers and Spartacus fighters into conversation, making use of his possibilities and good relationships to pass roadblocks and visit his extraordinarily wide range of acquaintances; he captured the chaos and confusion of the street fights in dozens of details, episodes and juxtapositions, small dramas without untying the knot. ”After the January uprising of the Spartakists and the opening of the Weimar National Assembly on February 6, 1919, Kessler explained to his visitor Wieland Herzfelde how the current political situation presented itself to him, and referred to three great ideas and power complexes in the struggle for the division of the world: “Clericalism, capitalism and Bolshevism; capitalism including its offspring militarism and imperialism. The three symbolic men of the time of the Pope, Wilson and Lenin, each with an immense, elementary-based violence and mass of people behind them. The size of the world-historical drama, the simplicity of its lines, the tragic that lies in the inescapability of the unfolding fate, is almost unparalleled. Standing outside and the whole cloud-like threatening Asia. Germany is now being caught secretly for clericalism, while Bolshevism is seizing it from within and without and capitalism is offering it a cinderella cookie at the table of capital through Wilson's mediation. "

When the revolutionary events in Berlin came to a head again at the beginning of March 1919 in the course of a general strike , Kessler attempted to persuade Foreign Minister Ulrich von Brockdorff-Rantzau , who was the only cabinet member in Berlin, to reshuffle the government on his own, in the manner of a coup d'état, from Scheidemann , Erzberger (and the Catholic center party any) should be removed with the aim of bringing leading Independent Social Democrats back into government functions; because these alone could still build on trust in the people. It is necessary to base Germany's reconstruction on the council system, i.e. to give the workers' councils the power they need to increase production, feed the unemployed and ensure peace and order. Brockdorff-Rantzau was very interested and impressed by Kessler's insistence, but hesitated whether he should rely on the Independent Social Democrats or the Spartacists in the given situation: “He said that if he did the thing with the Independents now and then after that Spartakists would come, then he would have played out. "

In fact, at this time there was again heavy fighting between government troops and Spartakists in the inner city of Berlin, using artillery and mortars, barricades and beating up wires. “The matter gives the impression of a much more serious war than the Spartacus uprising. Not a guerrilla, but a major operation; however, this will not decide because the latent dissatisfaction remains and grows. The explosion can only be postponed for a few weeks if the government troops win. ”When the general strike was suspended on March 8, 1919 and the newspapers reappeared, Kessler summed up:“ All the atrocities of the merciless civil war are underway on both sides. The hatred and bitterness that are now being sown will bear fruit. The innocent will atone for the horrors. It is the beginning of Bolshevism! "

Kessler's efforts to get Foreign Minister Brockdorff-Rantzau to join forces with the Independent Social Democrats by commuting and mediating between them and leading USPD representatives such as Hilferding , Breitscheid and Haase failed not only because of Rantzau's hesitation, but also because of the resistance of the majority Social Democrats and a lack of willingness to compromise on the part of the USPD. Kessler himself improvised and changed his political statements under the impression of the sometimes brutal and bloody confrontations and the related atrocity reports in the press. If he was accused of being a socialist, he always referred to membership in the bourgeois DDP, one of three pillars of the Weimar government coalition . For Easton, his work as the “gray eminence” behind the council movement was similar to his earlier efforts in favor of aesthetic modernism in the Wilhelmine era. "In both cases he was motivated by a strong belief in the effectiveness of informal networks of influential personalities." He looked for and used such small political circles and clubs - sometimes several in parallel - as his own base of influence.

League of Nations lateral thinker and pacifist

The sudden military collapse of Germany and the Central Powers in October 1918 subsequently determined the extremely limited scope for foreign policy of the Weimar Republic, which was being established. When it became known on February 16, 1919, Kessler harshly rejected the plan for a League of Nations developed by the victorious powers at the suggestion of US President Woodrow Wilson : “The first impression is that of a dry-legal bundle of old spirit, the poorly disguised imperialist servitude - and the robbery intentions of a number of victorious states poorly covered; a notarial contract of the kind imposed on poor relatives. ”Apparently, however, the model of the League of Nations supported by the victors of the World War inspired the diplomatically ambitious Kessler to an immediate alternative. He considered it to be an obvious mistake that rival to hostile states should form the basis of the League of Nations, while instead he had economic and humanitarian interest groups with their own striving for internationality as the main actors in mind: "These international associations (workers' international, international traffic - and raw material associations, large religious communities, Zionists, associations in the humanitarian or scientific fields, international banking consortia, etc.) one would have to lend power and means of coercion precisely against the states, legally separate them more and more from the individual states and make them independent and create frameworks and regulations for them; but not, conversely, give the ridiculous old committee of the great states even more power than before. A League of Nations, as I imagine it to be, would be the natural organ for the international repayment of the war debts and the reconstruction of the devastated; also for the international administration of the colonies (raw material areas). ”Just ten days later, Kessler published the counter-draft printed in his Cranach press under the title: Plan for a League of Nations based on an <Organization of Organizations> (World Organization) . The main body of this federation should have been a "World Council" to which an executive committee was assigned. In addition, a world court of justice, a world court of arbitration and administrative authorities should have been established. This paragraph-based plan took the form of a state constitution.

In that period and the following, Kessler was constantly busy using his diverse contacts to disseminate and discuss his approach to the League of Nations, for example in talks with Stresemann and the incumbent Foreign Minister Brockdorff-Rantzau. Since the German government was also looking for a counter-proposal to the League of Nations approach of the victorious powers, Kessler's draft was temporarily just right. The now questioned triumphed: “I am astonished myself at the force with which this idea has been breaking ground since I voiced it: the shackling of the state by the universal forces of humanity. Born out of desperation, it can perhaps shape the future of mankind and lead to a new bloom. Good Friday magic. ”From the cabinet deliberations, Kessler was told that his draft had met with great approval. In the end, however, the imperial government had its own counter-draft of the League of Nations, which was presented in Paris. Grupp explains Kessler's resignation by saying that in the dramatic situation after the defeat the German government might still have been prepared to put the economy, finance, nutrition and trade "partly in the hands of a 'world council'", but considers it completely out of the question. that the victorious states could have been ready to transfer their own arms industry, as proposed by Kessler, completely to the new world organization.

None of this came into play in any way when the Allies presented the Versailles Treaty to the German delegation on May 7, 1919, without any room for negotiation, simply on their terms. Kessler was so taken with the contents of the contract that he interrupted his diary for more than a month. As a result, however, Kessler took up the promotion of his League of Nations model again, went on lecture tours with it and found a lot of attention, especially in pacifist circles. Since January 1919 he was a member of the New Fatherland Federation ; the German section of the World Youth League made him honorary chairman, and the German Peace Society elected him to its board. The climax of Kessler's campaign was the IX. German pacifist congress in October 1920, which committed itself to its League of Nations plan in a resolution and set up a special committee for its dissemination. “As a result of these efforts, Kessler was able to get almost all organized pacifism behind him; outside of this narrowly limited circle, however, the response has remained low. "

Diplomat on his own mission

The defeat in the World War and the Treaty of Versailles brought about complete foreign policy isolation in the first half of the 1920s for Germany, which was not admitted to the League of Nations and was now republican, and, in connection with the necessary solution to reparation issues, a precarious rapprochement process, co-determined by mutual mistrust. Official government advances and initiatives on the part of Germany continued to face a sharp rebuff. In this situation, unofficial efforts to reach an understanding that were based on good political and social contacts seemed to promise more. It was precisely in this respect that Kessler had the best of conditions, as far as England and France were concerned.

At the Genoa Conference in 1922 he took on the role of intermediary for Foreign Minister Walther Rathenau , who assigned him to the French delegation with explorations. These efforts were, however, futile when Rathenau and Soviet Russia launched the Treaty of Rapallo at the same time , which fed the suspicions of the victorious powers. During the French occupation of the Ruhr area, Kessler worked in England on those responsible for the opposition liberals and the Labor Party to build pressure in the London House of Commons so that the British government, which was supporting the French approach, would at least be ready to examine German proposed solutions to the reparations question. In this case he was not denied success and recognition. The incumbent Foreign Minister Rosenberg , as Kessler noted in his diary, welcomed him in Berlin with open arms: "Well, there comes Kessler Triumphator, the English Prime Minister shakes, staged one Ruhr debate after another in the English Parliament, etc."

Even if Kessler thought in the meantime that he had long outstripped the rank of the German ambassador in London: He was still denied this position, which was now the only desirable position for him. Instead, with the express support of the Foreign Office (AA), he went on a political lecture tour to the USA in the summer of 1923 in order to promote German interests and approaches to the problem of reparations claims, occupation of the Ruhr and great inflation . Berlin was so impressed by his work, which also included a conversation with Secretary of State Hughes in the State Department , that in 1924 he was appointed a liaison officer for the League of Nations in Geneva . In this role, however, Kessler developed an urge for Germany to join quickly, which was clearly ahead of his instructions. The small successes in day-to-day diplomatic business were not his business; Kessler mostly aimed directly at the big hit: “He did not see himself as an ordinary diplomat and tool of the political leadership whose intentions he had to implement. He wanted to impose his own ideas and concepts on the Foreign Office, to push ministers and government in the direction he recognized as the right one. ”When he did not succeed in his League of Nations mission either - German accession did not come about until 1926 as a result of the Locarno Treaties - and his position as a "parallel diplomat" was increasingly controversial, Kessler largely stopped his diplomatic activities.

Dedicated Republican

In dispute especially with opponents of the Republic from the right-wing conservative fringes, Kessler developed a whole series of political activities. In the 1920s he tried to influence the political discussions of the Weimar Republic as a publicist and wrote articles on various social and foreign policy topics, including B. on guild socialism . Kessler was often a guest at the Berlin SeSiSo Club . After it was founded in 1924, he also joined the Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold organization for the protection of the republic .

To celebrate the 5th anniversary of the Weimar Constitution, on August 10, 1924, in front of several thousand listeners in Holzminden, he gave a haunting, militant speech in which he bluntly warned:

“I ask you: Do you want to become the subjects of any Wilhelm given to you by God's grace? (stormy shouts: no, no) Do you want to be cannon fodder for a new war again? (No, no) Do you want to stand in front of the "gentlemen in the house" in the factory yard as an employee without rights, hat in hand? (No, no) Then stand before the republic, protect it, defend it. Enter the organizations, join the <Reichsbanner Schwarz Rot Gold>. The best defense, however, is realization. See that what is promised in the Constitution will be realized. Above all, economic democracy, which Article 165 guarantees you, and the true international peace that your foreign policy must bring you. Force your leaders, your deputies, your ministers to ceaselessly strive to achieve these two goals. "

That same year, Kessler went to the DDP as the leading candidate in Northern Westphalia in the general election in December on at quite hopeless positions but because it was a stronghold of the Center Party . With only moderate support from his own party, Kessler accepted the challenge without sparing himself: he sometimes spoke up to four times a day. His campaign appearances in Minden, Bielefeld, Bückeburg and Münster, among others, fluctuated in the number of visitors between a few dozen and eight hundred people. The local press attacked the candidate and denounced his international connections among artists and in the peace movement. In the end, the DDP won four seats in the Reichstag. However, Kessler was not there. After this failure, he largely withdrew from politics and was now increasingly active as a writer.

Late work and legacy

It was not only the lack of success in his diplomatic and political engagements that caused Kessler to withdraw from these fields of activity from the mid-1920s, but also serious health problems. In the summer of 1925 his sister Wilma hurried to Berlin to look after his brother, who had been confined to bed for weeks; a year later, Kessler contracted pneumonia, was in acute danger of death and only gradually got back on his feet.

Kessler devoted himself more and more to writing and completing his own works and work plans. In his cultural-historical and aesthetic turn to ancient Roman times, there was a further expansion of his reception of antiquity. When he had the Augustus Forum in mind during a visit to Rome , all modern architectural products such as fairground stalls appeared to him "in comparison to these buildings that bear the stamp of eternity." What the Romans created convey the impression of a foundation for millennia and size in terms of strength and size “That similar qualities guarantee Roman law, the Roman concept of the state, and the Roman Church of their duration.” In addition to further trips to Italy, this intense interest was also reflected in the Cranach press .

About his party friend Walther Rathenau , who was murdered by right-wing extremists in 1922 , Kessler wrote a biography that was published in 1928 and received sustained attention. The magazine Das Freie Wort , which he co-edited, was published in 1932/33 .

Award-winning products from the Cranach press

The private printing company operated by Kessler from 1913 to 1931, the Cranach-Presse, became a permanent place of activity after many high-flying plans and unfulfilled expectations. In the course of his involvement as an innovator in Weimar, Kessler had already worked on an artistically demanding edition of Homer's Odyssey with great dedication and patience . He won over the poet Rudolf Alexander Schröder for a new translation, on which he meticulously scrutinizing and encouraging influence over the course of seven years, Aristide Maillol for the woodcuts for the titles of both volumes and Eric Gill for the design of the various capital letters in London . When it finally became clear that Kessler's book design of the Odyssey would succeed in cooperation with three artists and that it would be printed by Wagner Sohn, Kessler was determined to print further projects of this kind in his own private press in the future.

The first initiatives for an artistic redesign of the Eclogen Virgils were already underway while the Odyssey project was maturing. The illustration of the Greek shepherd idyll - "the paradise lost for the fragmented man of modernity, the spiritual and spiritual third home of Kessler, his beautiful dream of life" - should in turn create Maillol, whose attraction to the Eclogues Kessler since their first meeting 1904 was in mind. For the translation of Virgil's verses, Kessler won over Rudolf Alexander Schröder again in 1910 - and again brought his own ideas to the table in a critically stimulating way.

From 1914 to 1916, at the request of his friend, van de Velde managed the printing company when he was called up for military service in the First World War . Completion of the plant dragged on until 1927, after Kessler had not re-established contact with Maillol until 1922 due to the First World War and persistent delays had then occurred due to political engagement and serious illness. At the book art exhibition in Leipzig in 1927, however, the eclogues printed with the Cranach press were finally awarded the “Most Beautiful Book of the Year” in Kessler's presence.

Another work from the Cranach press was named “Most Beautiful Book of the Year” in 1930: a new edition of Shakespeare's Hamlet translated by Gerhart Hauptmann, a friend of Kessler's . Preparations for this printing unit also went back to 1910. Kessler had a new font specially designed by English type artists, the "Hamlet Fraktur". Edward Gordon Craig provided the figurines and woodcuts for the illustration. An extremely complex upheaval, in which three different fonts in black and red print had to be combined with Craig's woodcuts, required the highest level of craftsmanship. In this field, Kessler created something lasting with his ability to bring artists of different nationalities and disciplines together and to activate them in long-term projects for his own endeavors. Peter Grupp sums it up: “The Kessler of the Wilhelminian ancien régime once gave the impetus for the production of high-quality utility books with the Wilhelm Ernst edition, the democratic-republican Kessler now immersed himself in the extreme perfection of a unique luxury good. It was an evasion from the dynamic and hectic pace of contemporary Berlin into the calm and tranquility of a past that has never really been in its ideality. "

The Rathenau biography

During Walther Rathenau's lifetime, Kessler's relationship with him was ambivalent, sometimes distant, although he knew him well from long encounters and conversations. On the question of an alternative League of Nations concept, which is important for Kessler , Rathenau gave him a smooth rebuff early on, according to which Kessler judged in the diary: “Rathenau lectures everything in self-assured long speeches, which also often incorrectly illuminate the right thing. In general he is the man of the wrong notes and crooked situations: as a communist in a damask armchair, as a patriot out of condescension, as a new sounder on an old lyre. "

Under the impression of the politically motivated murder of Rathenau, which was understood as an attack on the Weimar Republic itself, Kessler's perspective changed. Rathenau's eminent political and moral importance among those loyal to the republic evidently made him worthy of exemplary appreciation.

In Kessler's portrayal, the different orientations of the parents appear to be fundamental for a double track and inner conflict of Walther Rathenau: Referring to the intellectual life of Goethe's time and Romanticism on his mother's side, he found in the life of his father Emil Rathenau only an incessant search for technical things connected with the pursuit of profit Innovation.

“It was the same conflict between the compulsion to restless technical progress, which demands all human strength, and the inevitable urge for the development of all soul forces, regardless of their usefulness, which maintains the hatred and contempt of millions of our civilization, and also she, like the similarly torn and hated Walther Rathenau, holds out the prospect of a violent end and an almost inevitable fate. Precisely because this conflict, which is the conflict of the epoch, shaped Rathenau's fate, his character does not appear as a tragic symbol of our time, even through his death as through his internally torn life, which in recent years has been constantly threatened. "

The funeral for Rathenau, laid out in the session hall of the Reichstag, which Kessler now saw removed as a symbol of understanding with the victorious powers of the First World War, stands at the end of this life consideration. "This is how the factory endeavored," says Laird M. Easton, "to establish Rathenau as the first great fallen hero of the German republic."

The memoir "Faces and Times"

The appreciation that Kessler gained for the products of his Cranach press did little to change his increasingly difficult financial situation after the legacy was almost exhausted and the journalistic success of the Rathenau biography, which was discussed in numerous newspaper reviews and in several languages had been translated, dwindled in terms of financial return. In 1931, under the pressure of accumulated debts, Kessler had to sell the Cranach press and from then on he only endeavored to open up new sources of income by writing and publishing his memoirs. The refutation of the rumors about his conception by Kaiser Wilhelm I was one of the main concerns in his diary. The first chapter should be called "My mother". "As a result, the memoirs have to a certain extent become a duty of piety."

In fact, in the first volume of the three-volume memoirs published under the title “Faces and Times”, Kessler gives his mother's notes ample space. It describes their first meeting with Wilhelm I in Bad Ems in 1870, as well as the scene between Wilhelm I and the French ambassador Benedetti , which the mother witnessed, leading to the Ems dispatch and the Franco-Prussian War . Four years later, during a summer stay in Kissingen , Reich Chancellor Otto von Bismarck and his family were interested in making contact with the Kesslers and often invited them to afternoon tea. After an assassination attempt on Bismarck during this stay, the six-year-old Harry, accompanied by a domestic worker, was sent with a bouquet of flowers to Bismarck, who accepted them while lying in bed. Kessler's judgment on Bismarck, as he portrayed it for his school and student days, was rather critical. In Hamburg classmates, they complained of increasing spinelessness even in opposition circles and attributed it to Bismarck's work. At a re-encounter accompanied by other students after Bismarck's dismissal as Chancellor, Bismarck had impressed as a brilliant narrator, but his fixation on the past offered the young people no future prospects.

At that time, according to Kessler, he and his peers were already under the influence of Friedrich Nietzsche : “At the beginning our feeling was a mixture of pleasant shuddering and amazed admiration in front of the monster fireworks of his mind, in which one piece after the other our moral armament went up in smoke. "To follow Nietzsche meant for them" to be something new, to mean something new, to represent new values. "With the response to Nietzsche's thinking, they would have connected the intrusion of a mysticism into the rationalized and mechanized time. "He stretched the veil of heroism between us and the abyss of reality."

Grupp is critical of some of the assessments that Kessler ascribes to his young years. It was only in retrospect that Kessler analyzed the progressive decay of the old, coupled with Bismarck, so clearly and contrasted it with the development of the new in Nietzsche's sense. He brought the first Nietzsche reading forward, overemphasized its spontaneous effect and portrayed the diplomatic career in a questionable way as a consistently pursued professional goal. “In the end, he described his life as he would have liked to have lived it. So his memories are at the same time an analysis of the lost Europe and the stylization and justification of his own life. ”But Kessler couldn't get beyond the first volume of memoirs, which covered his childhood, school and academic years. Otherwise, says Grupp, one would have been dealing with one of the great memoirs.

The diary entries from 1880 to 1937

Kessler kept a diary for 57 years, whereby he attached great importance to completeness. This diary can rightly be called Kessler's literary estate. Most recently it was published in nine volumes by the German Literature Archive in Marbach . They contain extensive registers of the places, works and people appearing in the text, some with detailed explanations. In total, the names of around 12,000 more or less important contemporaries from Sarah Bernhardt and Jean Cocteau to Otto von Bismarck and Albert Einstein to George Bernard Shaw , Elsa Brändström and Josephine Baker are listed, who justify Kessler's reputation as a "collector of people".

Laird M. Easton judges this part of Kessler's legacy: “It is precisely the intersection between a rich life and the extensive reporting on it, conveyed by an astute intelligence, that makes Kessler's diary one of the most important personal documents of the twentieth century, an inestimably valuable source for scholars who deal with art, literature and history, but also for a work that is read for its own sake - because of the vivid depiction of the political and intellectual upheavals of the last century from the perspective of a man who is uniquely predestined was to perceive all of this. "

Last years in exile

In the final phase of the Weimar Republic, Kessler noted in particular the transfer of the chancellorship from Heinrich Brüning to Franz von Papen as a fateful turning point: “This marked the worsening of the world crisis. Strangely enough, the Berlin stock exchange reacted to Demisson Briining's, probably in anticipation of the blessings of the Third Reich, with a sometimes sharp bull market: shares rose, fixed-income securities fell. Inflation perspective. Today marks the temporary end of the parliamentary republic. "

On January 28, 1933, Kessler noted: “Schleicher overthrown, Papen entrusted with negotiations to form a government. He is now unequivocally playing the role of a favorite of the President, since he has nothing else behind him and the whole people against him. I feel nauseous when I think that we are to be ruled again by this notorious wretch and gambler […] ”, and on January 30th it says:“ At two o'clock Max came to breakfast, who received the news of the Hitler's appointment as Reich Chancellor. The amazement was great; I did not expect this solution, and so quickly, too. Downstairs, at our Nazi porter, an exuberance of festive mood broke out immediately. "

For Kessler's personal situation, negotiations with S. Fischer Verlag about his memoirs were particularly urgent in February 1933 : From March 1, 1933, he was granted an advance payment totaling 12,000 marks in six monthly installments. From the trip to Paris, which he began two weeks after signing the contract, Kessler did not return to Germany because of serious warnings. In 1935, however, he was still hoping to return, also to save his property. In September 1935, however, his memoirs were banned in National Socialist Germany and the S. Fischer Verlag was also smashed.

From November 1933 to September 1936, Kessler lived mainly in Cala Rajada on Mallorca , busy working on his memoirs and cheaper in terms of living than before . He stayed away from the émigré circles active in the resistance against the Nazi regime, and the German consul in Barcelona reported to Berlin that Kessler was consciously avoiding commenting on the situation in Germany. When he left Mallorca in 1935 for health reasons for southern France and left his notes there with the intention of returning soon, he was permanently cut off because of the Spanish Civil War that broke out in 1936 , which also caused his secretary Albert Vigoleis Thelen to flee the island got no further with his memoirs. His financial situation was now desolate and his sister Wilma was less supportive; he could, however, live in her pension in Pontanevaux north of Lyon . On July 6, 1936, he sold his house in Weimar. After he had become increasingly heart disease, Harry Graf Kessler died on November 30, according to other sources on December 4, 1937 in a clinic in Lyon. He was buried in the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

Works

Fonts:

- Impressionists: the founders of modern painting in their main works: 60 matt-tone pictures with an introductory text and a catalog raisonné . Verlag F. Bruckmann, Munich 1908, digitized online .

-

The diary 1880–1937 . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2004–2018.

- Vol. 1: 1880-1891 . ISBN 978-3-7681-9811-0 .

- Vol. 2: 1892-1897 . ISBN 3-7681-9812-X .

- Vol. 3: 1897-1905 . ISBN 3-7681-9813-8 .

- Vol. 4: 1906-1914 . ISBN 3-7681-9814-6 .

- Vol. 5: 1914-1916 . ISBN 3-7681-9815-4 .

- Vol. 6: 1916-1918 . ISBN 3-7681-9816-2 .

- Vol. 7: 1919-1923 . ISBN 3-7681-9817-0 .

- Vol. 8: 1923-1926 . ISBN 3-7681-9818-9 .

- Vol. 9: 1926-1937 . ISBN 3-7681-9819-7 .

- Diaries 1918–1937 . 2nd edition Insel, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-458-33479-3 .

-

Collected writings in three volumes . Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-596-25678-X .

- Vol. 1: Faces and Times .

- Vol. 2: Notes on Mexico (digitized version of the 1898 edition (F. Fontane, Berlin) online ).

- Vol. 3: Memories .

- Souvenirs d'un Europeans . Volume I: De Bismarck à Nietzsche . Plon, Paris 1936.

Letters:

- Hilde Burger (ed.): Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Harry Graf Kessler: Correspondence 1898–1929. Frankfurt Main 1968 (contains 377 letters and 6 collective letters).

- Hans-Ulrich Simon (Ed.): Eberhard von Bodenhausen - Harry Graf Kessler. An exchange of letters from 1894–1918 . Marbach am Neckar 1978.

- Antje Neumann (ed.): Harry Graf Kessler - Henry van de Velde: The exchange of letters . Böhlau , Cologne / Vienna 2014, ISBN 978-3-412-22245-1 .

literature

- Briefs

- Birgit Jooss: With a walking stick through the modern age. Harry Graf Kessler. In: Weltkunst. The art magazine of the time. Special issue "Berlin". Edited by Christoph Amend and Gloria Ehret, April 2016, pp. 62–68.

- Gerhard Schuster, Margot Pehle (ed.): Harry Graf Kessler, diary of a man of the world. Exhibition catalog, Deutsche Schillergesellschaft, Marbach am Neckar 1988.

- Hans-Ulrich Simon: Kessler, Harry Graf von. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 11, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1977, ISBN 3-428-00192-3 , p. 545 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Brandenburger Tor Foundation: (Ed.): Harry Graf Kessler. Stroll through the modern age . Exhibition catalog, Nicolai, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-89479-940-3 .

- Biographies

- Julia Drost, Alexandre Kostka: Harry Graf Kessler: Portrait of a European cultural mediator. Deutscher Kunstverlag , Berlin / Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-422-07318-0 .

- Peter Grupp: Harry Graf Kessler - a biography. Insel, Frankfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 3-458-34233-8 .

- Laird McLeod Easton: The Red Count, Harry Count Kessler and His Time. From the American by Klaus Kochermann. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-608-93694-7 .

- Hans Dieter Mück : "Strolled, read, seen, lived a lot" - Harry Graf Kessler - The biography. Volume I: 1868-1898 . Weimar 2018, ISBN 978-3-7374-0268-2 .

- Gerhard Neumann (ed.): Harry Graf Kessler, a pioneer of modernity. Rombach, Freiburg im Breisgau 1997, ISBN 3-7930-9118-X .

- Friedrich Rothe : Harry Graf Kessler. Siedler, Berlin 2008, ISBN 3-88680-824-6 .

- Individual representations

- Sabine Walter: The Harry Graf Kessler Collection in Weimar and Berlin. In: Andrea Pophanken, Felix Billeter (ed.): Modernism and its collectors: French art in German private ownership. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2001, pp. 67–93 (Kessler as an art collector, limited preview in the Google book search).

Exhibitions

- Homage to Count Harry Kessler (1868–1937). Exhibition in the Bröhan Museum (State Museum for Art Nouveau, Art Deco and Functionalism 1889–1939), 2007 on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of his death on November 30, 2007 from December 1, 2007 to January 31, 2008. With accompanying publication, Ed. Ingeborg Becker et al., Berlin 2007, Bröhan Museum Berlin.

- Semper adscendens - exhibits of the Kessler family from the Finckenstein collection , exhibition in the Hohenlohe studio, feodora-hohenlohe.de/ , Berlin December 2014.

- Harry Graf Kessler - Flaneur through Modernism , exhibition in the Max-Liebermann-Haus , Berlin May 21 - August 21, 2016.

Web links

- Literature by and about Harry Graf Kessler in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Harry Graf Kessler in the German Digital Library

- Works by Harry Graf Kessler in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Short biography and reviews of works by Harry Graf Kessler at perlentaucher.de

- Harry Graf Kessler - The Man Who Knew Everyone , Documentary by Sabine Carbon on Youtube

- Harry Graf Kessler - Flaneur through Modernism , exhibition of the Brandenburg Gate Foundation in Berlin

- Christian Eger: Harry Graf Kessler - The Bauhaus Godfather , in: Mitteldeutsche Zeitung , August 3, 2016, p. 22 (including about the Kessler exhibition in Berlin).

Remarks

- ↑ Rothe 2008, p. 12.

- ↑ Rothe 2008, p. 17.

- ↑ Diary entry from May 23, 1888 ("a terrible idea to imagine your life as a money-making machine"); quoted n. Rothe 2008, p. 12.

- ↑ Rothe 2008, p. 24 f.

- ↑ Rothe 2008, pp. 26-30.

- ^ The diary. Vol. 9, p. 396; Date: December 5, 1931, Stuttgart 2010 / Faces and Times , introduction, Frankfurt am Main 1988.

- ^ Family correspondences with Jacques Marquis de Brion, Wilma Marquise de Brion and Alice Countess Kessler at: polunbi.de .

- ^ Brion, Wilhelma Karoline Louise Alice de Michel du Roc, Marquise de (1877–1963) kamzelak.de ( Memento from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Rothe 2008, p. 35.

- ↑ Rothe 2008, p. 50.

- ↑ Rothe 2008, p. 51.

- ↑ Soberly, he noted in his diary what the ship's commissioner had told him about the working conditions in the engine rooms of some of the new ocean liners: On the maiden voyage of the City of New York , six stokers who had been locked in the engine room during the shift died of heat stroke. “On the ships of the East Asian Line, they must be doused with cold water while they are pouring coals; in the Red Sea, the temperature in the engine room rises to 60 degrees. On some ships, namely cargo boats, the machinists are on duty 14 hours a day. ”(Diary January 3, 1892; quoted in Rothe 2008, p. 56).

- ↑ Diary February 17, 1892; quoted n. Rothe 2008, p. 60.

- ↑ Rothe 2008, p. 74.

- ↑ Diary June 1, 1892; quoted n. Rothe 2008, p. 59.

- ↑ Rothe 2008, pp. 57 and 88.

- ↑ Rothe 2008, p. 58.

- ↑ Rothe 2008, p. 102.

- ↑ Rothe 2008, pp. 109–114.

- ^ Tilman Krause : A brilliant dilettante. In: The world . April 24, 2004, accessed November 30, 2017 .

- ↑ Rothe 2008, p. 103 f.

- ↑ Rothe 2008, pp. 100 and 114.

- ↑ The price for the simple edition was six times the price for the luxury edition of Pan on handmade paper with stored original prints eight times the usual price (160 versus 20 marks), according to Easton 2005, p. 88 f.

- ^ Easton 2005, p. 87.

- ↑ Grupp 1999, p. 62.

- ↑ Grupp 1999, pp. 62-64; the first encounter with Maillol dates back to August 1904 (Easton 2005, p. 158).

- ↑ Easton 2005, p. 96 f .: "The founding of the magazine has been described as one of four decisive events that - in addition to the creation of the free stage, the beginning of the Berlin Secession and the founding of the S. Fischer Verlag - Berlin, Twenty years after the founding of the Second Empire, made it a world city of culture. "

- ↑ Grupp 1999, p. 87.

- ^ Easton 2005, p. 103.

- ^ Easton 2005, p. 104.

- ^ Easton 2005, p. 157 f.

- ^ Easton 2005, p. 158.

- ^ Easton 2005, p. 217.

- ^ Easton 2005, pp. 218-222.

- ↑ Grupp 1999, pp. 86-88; Easton 2005, pp. 131-133.

- ↑ Grupp 1999, p. 89 f.

- ↑ Grupp 1999, pp. 93-96.

- ^ Henry van de Velde, pp. 223–228 Harry Kessler and Weimarer Museum: PDF. Retrieved April 26, 2020 .

- ↑ Grupp 1999, p. 97 f.

- ↑ Grupp 1999, p. 100 f.

- ^ Easton 2005, p. 169.

- ^ Easton 2005, p. 177 f.

- ↑ Grupp 1999, p. 126.

- ↑ Kessler said derogatory about von Werner's own work: “You know Herr von Werner's pictures. Their subjects have ensured them a wide distribution, which corresponds roughly to that of the state manual for the Prussian monarchy. Ministries and sub-civil servants' apartments get their mood from them. There they apply to historical images. Twelve to sixty uniformed, strikingly expressionless men usually stand around, infinitely dry and stiff. One thinks a fashion picture for military tailors, an illustration of the dress code; but the signature states: a picture of history, a great moment from a great time; King Wilhelm's council of war, the capitulation of Sedan, the imperial proclamation in Versailles. Before you wanted to laugh; now one would prefer to cry if boredom does not exclude any affect. "( Herr von Werner . In: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume II, edited by Gerhard Schuster, Frankfurt a. M. 1986, p. 79; quoted from Easton 2005, P. 141).

- ^ Easton 2005, p. 145.

- ↑ Grupp 1999, p. 110 f.

- ↑ “And the echo of all this reached beyond Germany; Both the London Times and the New York Times saw it as a setback for the Kaiser. ”(Easton 2005, p. 149) The New York Times headlined:“ Kaiser, as Art Critik, Flouted in Reichstag. ”(Rothe 2008, p 171).

- ↑ Easton 2005, pp. 145-149; Grupp 1999, pp. 110-114.

- ↑ Quoted from Rothe 2008, p. 176 f.

- ↑ Grupp 1999, pp. 110-114. “Wilhelm II acknowledges the departure of what he calls' a crosshead! modern totally twisted ', with the margin note' very enjoyable! '”(ibid., p. 125).

- ↑ Rothe says: “Above all, one thing was certain: Henry van de Velde alone was capable of artistically mastering the project, which must by no means be trivial. She had now coped with the thorough renovation of the archive, which was inaugurated on October 15, 1903 with the unveiling of Max Klinger's two and a half meter high Nietzsche Herme. At social occasions she paid homage to van de Velde by preferring to appear in the secessionist fashion he designed, such as the dress with which she was portrayed by Edvard Munch in 1906. ”(Rothe 2008, p. 215).

- ^ Easton 2005, p. 233 f .; Grupp 1999, p. 149.

- ↑ Grupp 1999, p. 150. Easton reports Kessler's intentions as follows: “Maillol's sculpture of a naked young man in front of the temple is supposed to represent the Apollonian principle; only an artist who is deeply rooted in classical antiquity can create the clear contours necessary to express this principle. Inside the temple, the bas-reliefs, which illustrate key sentences from Nietzsche's work, would represent the formless, gloomy, musical Dionysian principle ”(Easton 2005, p. 234).

- ↑ Kessler advertised it with the words: "Your brother was the first to teach us the joy of [...] physical strength and beauty again, the first to bring physical culture, physical strength and skill back to the spirit and the highest things in Has brought relationship. I would like to see this relationship realized in this memorial. ”Regarding Ms. Förster-Nietzsche's initially negative reaction, Kessler noted:“ Basically, she is a small, narrow-minded pastor's daughter who swears by her brother's words, but is appalled and outraged as soon as you get there turn them into action. She justifies much of what her brother said about the woman; she was also the only woman he knew intimately ”(quoted from Easton 2005, pp. 236 and 238).

- ^ Easton 2005, p. 237.

- ↑ Easton 2005, p 241-244.

- ^ Letter to Hugo von Hofmannsthal from September 26, 1906, p. 126 f .; quoted in Easton 2005, p. 203.

- ↑ Quoted from Grupp 1999, p. 132.

- ↑ Quoted from Easton 2005, p. 230.

- ^ Easton 2005, p. 247; there also Easton's reference to the Nietzsche quote: "Only in dance do I know how to speak parables of the highest things."

- ^ Easton 2005, pp. 254-264.

- ↑ Grupp 1999, p. 231; Easton 2005, pp. 452 f.

- ↑ These include a. an edition of Virgil's Eclogues with illustrations by Aristide Maillol and Shakespeare's Hamlet in the new translation by Gerhart Hauptmann and with illustrations by Edward Gordon Craig. Trial prints were made for an edition of Petronius' Satyricons with woodcuts by Marcus Behmer .

- ↑ Grupp 1999, p. 155 f. "He had no contact whatsoever with the peace movement at the time," emphasizes Grupp, probably with a view to Kessler's role during the Weimar Republic, "but in 1909 he became a member of the German Colonial Society, one of the most important imperialist pressure groups." (Ibid., P. 159)

- ↑ Grupp 1999, p. 159.

- ↑ Quoted from Easton 2005, p. 275.

- ↑ Grupp 1999, p. 163

- ↑ Grupp 1999, pp. 162-167.

- ↑ Grupp 1999, p. 166.

- ↑ Grupp 1999, pp. 114–116 and pp. 174–177.

- ↑ Quoted from Easton 2005, p. 340.

- ↑ Diary November 18, 1918. As early as November 14, Kessler had put his own calling into perspective in the diary: "In reality, very few people will want this post."

- ^ Easton 2005, pp. 347-351.

- ^ Easton 2005, p. 354.

- ↑ Diary February 7, 1919.