Battle for Verdun

| date | February 21 to December 19, 1916 |

|---|---|

| place |

Fixed place Verdun , France |

| output | French tactical victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Erich von Falkenhayn , |

|

| Troop strength | |

| a total of 75 divisions 400 guns (at the beginning of the battle, later approx. 1300) |

a total of 50 divisions 1225 guns |

| losses | |

|

approx. 377,000 soldiers, of which 167,000 were killed |

approx. 337,000 soldiers, including approx. 150,000 dead |

The Battle of Verdun [ vɛrˈdɛ̃ ] was one of the longest and most costly battles of the First World War on the Western Front between Germany and France . It began on February 21, 1916 with an attack by German troops on the Feste Platz Verdun and ended on December 19, 1916 without success by the Germans.

After the Battle of the Marne and the protracted positional warfare , the German Supreme Army Command (OHL) recognized that, in view of the emerging quantitative superiority of the Entente, the opportunity for strategic initiative was gradually slipping away from it. The idea of an attack near Verdun originally came from Crown Prince Wilhelm , Commander-in-Chief of the 5th Army , with Konstantin Schmidt von Knobelsdorf , Chief of Staff of the 5th Army , de facto in charge . The German High Command decided to attack the originally strongest fortress of France (since 1915 partly disarmed) to turn the war on the Western Front again in motion to bring. Around Verdun there was also an indentation of the front between the front arch of St. Mihiel in the east and Varennes in the west, which threatened the German front on its flanks. In contrast to subsequent representations by the Chief of Staff of the German Army, Erich von Falkenhayns , the original intention of the attack was not to let the French army "bleed to death" without spatial targets. With this claim made in 1920, Falkenhayn tried to give the unsuccessful attack and the negative German myth of the "blood mill" an alleged meaning.

Among other things, the attack was intended to induce the British expeditionary force fighting on French soil to abandon its alliance obligations. The Verdun fortress was chosen as the target of the offensive. The city had a long history as a bulwark and was therefore of great symbolic importance, especially for the French population. The military strategic value was less important. In the first war period, Verdun was considered a subordinate French fortress .

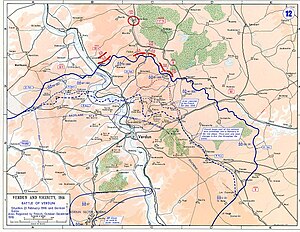

The OHL planned to attack the front arch that ran around the city of Verdun and the upstream fortress belt. Taking the city itself was not the primary goal of the operation, but the heights of the east bank of the Meuse , in order to bring the own artillery into a dominant situation, analogous to the siege of Port Arthur , and thus to make Verdun untenable. Falkenhayn thought that, for reasons of national prestige, France could be induced to accept unacceptable losses in defense of Verdun. In order to hold Verdun, if the plan had succeeded, it would have been necessary to recapture the heights, which were then occupied by German artillery, which, given the experience of the battles in 1915, was considered almost impossible. The action was nicknamed Operation Court . The High Command of the 5th Army was given the task of carrying it out.

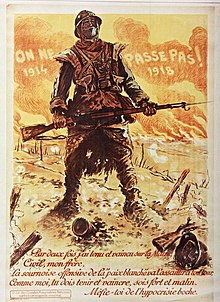

The battle marks a climax of the great material battles of the First World War - never before had the industrialization of the war become so clear. The French system of the Noria (also called "Paternoster") ensured a regular exchange of troops on a rotation principle. This contributed significantly to the defensive success and was an essential factor in establishing Verdun as a symbolic place of remembrance for all of France. The German leadership assumed, however, that the French side was forced to relieve the troops because of excessive losses. In the German culture of remembrance , Verdun became a term associated with a feeling of bitterness and the impression that it had been burned.

Although the Battle of the Somme, which began in July 1916, was associated with significantly higher losses, the months of fighting in front of Verdun became a Franco-German symbol of the tragic fruitlessness of the trench warfare. Verdun is now considered a memorial against acts of war and serves as a common memory and before the world as a symbol of Franco-German reconciliation .

The German attack began after the actual date of the attack on February 12th had been postponed several times due to the freezing and wet weather, on February 21st, 1916. This delay of the attack between February 12th and 21st, as well as reports of defectors, gave the French intelligence but the time and arguments to convince Commander-in-Chief Joseph Joffre that a large-scale attack was being prepared. Because of the irrefutable evidence of German concentrations at the front, Joffre hastily pulled together fresh troops in support of the defending French 2 e armée . For their part, the French concentrated around 200,000 defenders on the threatened eastern bank of the Meuse , facing a German superior force of around 500,000 soldiers from the 5th Army .

At first the attack made visible progress. As early as February 25th, German troops captured Fort Douaumont by hand. As expected from the German side, the commander-in-chief of the 2 e armée Philippe Pétain made every effort to defend Verdun. The village of Douaumont could only be captured on March 4th after a hard fight. In order to escape the flanking fire, the attack has now been extended to the left bank of the Meuse. The height "Toter Mann" changed hands several times with severe losses. Fort Vaux on the right bank was long fought over and defended to the last drop of water. The fort surrendered on June 7th.

As a result of the Brusilov offensive that began on the Eastern Front at the beginning of June , German troops had to be withdrawn from the combat area. Nevertheless, another major offensive started on June 22nd. The Ouvrage de Thiaumont and the village of Fleury could be captured. The Battle of the Somme , started by the British on July 1st, led, as planned, to further German troops having to be withdrawn from Verdun. In spite of this, the German troops began a last major offensive on July 11th, which they led to shortly before Fort Souville . The attack then collapsed due to the French counterattack. Subsequently, there were only smaller undertakings on the German side, such as the attack by Hessian troops on the Souville nose on August 1, 1916. After a period of relative calm, Fort Douaumont fell back to France on October 24, Fort Vaux had to be evacuated on November 2nd. The French offensive continued until December 20th, when it was also canceled.

prehistory

A few months after the outbreak of the First World War, the front froze in November 1914 in western Belgium and northern France . Both warring parties built a complex system of trenches that stretched from the North Sea coast to Switzerland . The massive use of machine guns , heavy artillery and extensive barbed wire obstacles favored defensive warfare, which led to the loss-making failure of all offensives without the attackers being able to achieve any notable gains in terrain. In February 1915 the Allied side tried for the first time to destroy the opposing positions with cannon fire for hours in order to be able to achieve a breakthrough afterwards. The German opponents were, however, by the barrage warned of an impending attack and stood ready reserves. In addition, the exploded projectiles created numerous shell holes, which made it difficult for the attacking soldiers to advance . The Allied offensives in Champagne and Artois therefore had to be canceled due to high losses.

The German strategy - "Operation Court"

In the winter of 1915, the Supreme Army Command (OHL) under Erich von Falkenhayn began planning an offensive for the coming year. All strategically possible and promising sections of the front were discussed. The OHL came to the conclusion that Great Britain had to be driven out of the war, since it was the engine of the Entente due to its exposed maritime location and its industrial efficiency . On the basis of these considerations, Italy was rejected as an unimportant target. Likewise Russia : Although German and Austro-Hungarian troops had gained larger territories in the fight against Russia from July to September 1915, Falkenhayn was convinced that the German forces were insufficient for a decisive advance due to the enormous size of the Russian Tsarist Empire. Even the capture of Saint Petersburg would only be of a symbolic nature and would not result in a decision if the Russian army withdrew into the area. The Ukraine would be because of their agriculture a welcome fruit of such a strategy, which should be picked but only with a clear understanding of Romania, because they wanted its entry into the war on the side of the Entente prevent. Other locations in the Middle East or Greece were described as meaningless. An attack on the Western Front was the only option. The positions of the British in Flanders were meanwhile so strong that Falkenhayn proposed the French front as the decisive theater of war.

He argued: “France [has] reached the limit of what is still bearable in its achievements - incidentally, with admirable sacrifice. If it succeeds in making it clear to his people that they have nothing more to hope for militarily, then the border will be crossed and England's best sword will be knocked out of her hand. ”Falkenhayn hoped that the collapse of the French resistance would lead to the withdrawal of the British forces would follow.

He considered the fixed place Belfort and Verdun as a target . Due to the strategically rather insignificant location of Belfort near the Franco-German border and the possible flanking of the fortress Metz , the Supreme Army Command decided in favor of the fortress Verdun.

The strategic location of Verdun in the front belt promised a worthwhile goal at first glance: After the border battles in September 1914, the German offensive had formed a wedge in the front at Saint-Mihiel , which hung as a constant threat to the French defenders. This enabled the German 5th Army under Crown Prince Wilhelm of Prussia to attack from three sides, while the French High Command (GQG - Grand Quartier Général ) was forced to withdraw troops from other important sections of the front and via the narrow corridor between Bar-le-Duc and Verdun to relocate to the attacked section. On the other hand, a look at the geography conveys a completely different picture: The French fortifications were dug into the slopes, forests and on the peaks of the Côtes Lorraines . The forts , fortified shelters, walkways, concrete block houses and infantry works were almost impossible obstacles for the attacking soldiers; Barbed wire, scrub, undergrowth and the height difference of up to 100 meters that had to be overcome also hindered the attackers. One had to reckon with great losses.

In order to meet these conditions, the attack of the German units was to be prepared with a gunfire of previously unknown proportions. The strategic plan was given the name "Chi 45" - the name for "court" from the then valid secret key. At Christmas 1915, Kaiser Wilhelm II gave permission to carry out the offensive. The actual attack was to be led by the German 5th Army under Crown Prince Wilhelm of Prussia on the east bank of the Meuse . A large-scale attack on both sides of the river was ruled out by Falkenhayn. This apparently absurd decision, which did not take into account the superior position of the Germans on both sides of the river, was sharply criticized by both Crown Prince Wilhelm and Konstantin Schmidt von Knobelsdorf , Chief of Staff of the 5th Army and the actual decision maker. Nevertheless, no modifications were made to "Chi 45".

Falkenhayn's goals

The capture of the city by German troops would have had negative effects on French war morale, but Verdun could not have been used as a starting point for a decisive attack on France. The distance to the French capital Paris is 262 kilometers, which would have been almost insurmountable in such a positional war .

In his post-war memoirs from the OHL (1920), Falkenhayn claims that as early as 1915 he had spoken of a strategy of attrition, a tactic of "tearing out and holding" . To confirm this statement, the fact is often mentioned that Falkenhayn did not launch a concentrated attack on both banks of the Meuse, which might have meant the rapid capture of Verdun. One interpretation of this decision was that the OHL wanted to avoid direct success in order to concentrate the French troops in front of Verdun for defense. In this respect, Falkenhayn actually did not intend to capture Verdun, but to involve the French army in a protracted attrition, which would ultimately lead to the complete material and personal exhaustion of France. This plan, however, cannot be proven by any records other than those written by Falkenhayn himself and much later, and is now considered skeptical, but not impossible. In fact, Falkenhayn believed in a counterattack in the flank area and wanted to hold back appropriate reserves so that he could not provide enough troops for a simultaneous attack on both banks of the Meuse. Falkenhayn by no means wanted to avoid direct success.

A more probable and therefore common reading is that Falkenhayn, as Chief of the Army, a rather hesitant strategist, did not pursue this strategy from the beginning, but only declared it in the course of the battle from the pure means to the goal; Above all, as a justification against the background of the unsuccessful attempts and the high own losses. The orders to the fighting troops, which are designed to gain ground, clearly support this interpretation: Falkenhayn ordered an offensive "in the Meuse area in the direction of Verdun" , the Crown Prince declared "to bring the Verdun fortress to fall quickly" , and von Knobelsdorf had given the two attack corps the task of "advancing as far as possible" . The attacking 5th Army implemented these orders without tactical waiting, following the strategy of bleeding, and without attacking exclusively aimed at high foreign losses. The primary aim of the attack was to conquer the mountain ranges on the east bank of the Meuse in order to bring your own artillery into a dominant position.

Verdun fortress

From the French point of view, the defense of Verdun was a patriotic duty, which, however, completely contradicts the modern military point of view: a strategic retreat to the wooded ridges west of Verdun would have created a much simpler defensive position, erased the bulge and released troops. The French military doctrine of 1910, vehemently advocated by Joffre, was the offensive à outrance (roughly: 'to the extreme'). A defensive tactic or strategy has never been seriously considered. When some officers, including General Pétain and Colonel Driant , expressed concerns about this doctrine, their stance was rejected as defeatist .

As commander of the important section in the forest of Caures and commander of the 56th and 59th battalions of the Chasseurs à pied, Driant had repeatedly tried in vain to persuade the GQG to significantly improve the French trench system. On their own, Driant had his fighters fortify their position against the expected attack; nevertheless, Driant fell in the first attack on February 22nd. Complementary to a meaningful defense, the GQG and Joffre relied on the system of French defense by attack, the backbone of which was the thrust of the poilu , the common soldier who, through his cran , his courage, was supposed to bring the decisive advantage.

After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71, France began to secure the border with the German Empire by building modern fortifications ( Barrière de fer ), despite the belief that victory could only be achieved by advancing infantry. For this purpose, several cities in eastern France were surrounded by a ring of forts , including Verdun, which is located on the Meuse. Verdun was primarily seen as a replacement for the lost Metz , whose old fortifications were greatly expanded by the empire. At the beginning of the war there were over 40 fortifications in and around Verdun , including 20 forts and intermediate works ( ouvrages ) that were equipped with machine guns, armored observation and gun turrets and casemates . Verdun was thus one of the best fortified locations. Another reason for the particularly strong expansion of the Verdun Fortress was the short distance of 250 km to Paris for the means of transport at the time, as well as its location on a main road.

As early as September 22-25, 1914, fighting broke out in front of Verdun and ended the German advance in the Maas area. Under the impression of the enormous destructive power of the German siege guns in front of Namur and in front of Liège , the importance of strong fortifications in an attack with heavy siege guns (for example 30.5 cm siege mortars ) was seen differently than before.

The siege of Maubeuge (it began on August 28, 1914 and officially ended on September 8, 1914 with the surrender of Maubeuge ) - had shown the Germans and French that fortresses were not impregnable, but could be 'shot down'.

This and the fact that the warring parties concentrated on other front sections in the aftermath of the border battles led to a reassessment of Verdun's military importance: The GQG under Joffre declared Verdun to be a quiet section. On August 5, 1915, the Verdun fortress was officially downgraded to the center of the Région fortifiée de Verdun - RFV ("Fortified Region of Verdun"). In the months that followed, 43 heavy and 11 light gun batteries were consequently withdrawn from the fortress ring and most of the forts machine guns were handed over to field units. There were now only three divisions of the XX. Corps stationed:

- the 72nd Reserve Division from the Verdun region,

- the 51st reserve division from Lille and

- the 14th regular division from Besançon.

The 37th Division from Algeria was in reserve .

Course of the battle

Late 1915 to February 1916: preparation of the German offensive

Preparations for the German attack began at the end of 1915. 1,220 artillery pieces were pulled together in a very small space, while 1,300 ammunition trains transported two and a half million artillery shells to the front. Twelve flying detachments and four combat squadrons of the Supreme Army Command , a total of 168 aircraft, were subordinated to the 5th Army. Each corps received an aviation and an artillery division, and each division an aviation division. The combat area was completely photographed from the air. On February 6, 1916, the staff of the 12th IB was brought together with the leadership of the 6th ID who were already there in Billy. In order not to make the French opponents aware of the plan, which had to zeroing of the guns gradually take place, resulting in a very long time to prepare. For nights on end, attack positions were excavated on the German side, which were camouflaged from the view of the aircraft. The fighter pilots flew in rolling lock missions to prevent enemy aerial reconnaissance. To combat the French infantry, the German army provided numerous guns with a caliber of 7.7 cm to 21 cm, while long-range cannons were to be used against the French supply lines. There were also 21 cm mortars , which were particularly powerful. In addition, the parked kuk artillery units offered 17 30.5 cm M.11 mortars . The heaviest German guns that were transported into the attack area were two (other sources speak of three) 38 cm ship guns (" Langer Max ") and 13 mortars with a caliber of 42 cm, also known as " Big Bertha ". The strength of the 5th Army was also increased by ten additional divisions, including six regular ones.

On the east bank of the Maas, only six divisions were to carry the first attack on the first day of the attack:

- the VII Reserve Corps (Westphalia and Rhineland) under Infantry General Hans von Zwehl with the 13th and 14th Reserve Divisions between Consenvoye and Flabas,

- the XVIII. Army Corps (Hessen and Nassau) under General der Infanterie Dedo von Schenck with the 21st and 25th Divisions in the middle

- and the III. Army Corps (Brandenburg) under General der Infanterie Ewald von Lochow with the 5th and 6th Divisions between Ville and Gremilly.

On the left wing on the Woevre Plain in the east should be

- the 5th Reserve Corps (Posen and West Prussia) under General of the Infantry Erich von Gündell with the 9th and 10th Reserve Divisions

- and the XV. Army Corps (Alsace-Lorraine) under General der Infanterie Berthold von Deimling with the 30th and 39th Divisions join the attack on the following days.

On the west bank of the Meuse should

- the VI. Reserve Corps (Silesia) under Infantry General Konrad Ernst von Goßler with the ( 11th and 12th Reserve Divisions ) initially only support the main attack with their artillery.

Despite repeated warnings from the secret service , the military leadership on the French side only became aware on February 10th that an attack on Verdun was imminent. This was planned for February 12th, but the Germans postponed it due to bad weather. Joffre ordered reinforcements to be sent to Verdun; the garrison of Verdun began on the orders of the governor of the city, General Herr , with the makeshift construction of field fortifications . Although there was a simple system of trenches in front of the Verdun forts, it was not designed to ward off a large-scale attack. When the weather cleared on February 20, the German General Staff set the attack on the following morning.

February 21-25, 1916: The first five days

On the morning of February 21, 1916 at 8:12 a.m. German time (7:12 a.m. French time), a fire was fired in the forest of Warphémont ( 49 ° 21 ′ 31.5 ″ N , 5 ° 36 ′ 17.9 ″ E ) Standing German 38 cm ship gun Langer Max fired a shell on Verdun, 27 kilometers away. The shell was intended to destroy a bridge over the Meuse , but missed its target and exploded either next to the city's cathedral or near the train station. Then the 1220 German guns of all calibers opened fire on the French positions and the hinterland at the same time. The severity of the bombardment, which was carried out non-stop for nine hours and with an intensity that was previously not thought possible, was unprecedented in military history. The attackers themselves and the men on the other side were amazed and shocked at the same time by the tremendous impact of this bombardment, which seemed to increase its violence even further: small and medium-caliber field guns fired the foremost French lines, the heavy guns aimed at them second and third defenses, and the heaviest calibers, the supply lines and the most important fortifications of the French under fire. With sufficient ammunition supplied by the nearby supply lines of the front line, a projectile quantity of around 100,000 impacts per hour was possible on the entire front section. At 1.30 p.m., the gunfire was intensified again by 150 mine throwers , which wreaked havoc in the trenches and saps on the French side. The peak of the bombardment was reached at 4:00 p.m.: the German artillery went over to barrage on the French lines. Now the German gun crews fired using all their physical capabilities and at the limits of their guns. A rain of bullets fell on the defenders, which the crews in the factories acknowledged with horror and shaking their heads in disbelief. On July 1, 1916, the beginning of the Battle of the Somme , the Germans, for their part, had such an experience, as the previously unknown extent of grenade fire was even exceeded. The artillery fire could be heard as far as Belfort.

Meanwhile, six German infantry divisions were ready to attack. First of all, small squads were sent to check the shot-up terrain for the best and no longer resistant gaps in attack for the attacking special forces. As a special unit, these " storm troops " were trained to run and fire at the same time, a technique that was developed by Captain Willy Rohr and his storm battalion in 1915 and ordered by Falkenhayn for general introduction. The stormtroopers had bayonets attached and were equipped with cartridge bandoliers (90 rounds), sacked sandbags with stick grenades and gas masks , some carried flamethrowers and, in some cases, large engineer shovels, in order to restore trenches and positions they had captured for their own defense as quickly as possible. In addition, most of them had training in enemy weapons, especially machine guns and hand grenades, so that they could use captured weapons immediately. The tips of the spiked bonnets had been removed so as not to get caught in the barbed wire; A few soldiers were already wearing the model 1916 steel helmet, the shape of which was to become the symbol of the German infantryman for three decades.

The first wave of attacks at 5:00 p.m. consisted of reconnaissance troops, storm troops, but also artillery observers and engineers . Behind them advanced the bulk of the rest of the infantry, which were also equipped with entrenchments and tools for the expansion of the conquered positions. The German troops had express orders to initially only explore the area, to occupy the foremost French trenches and to expand them against any counter-attacks. The German aviators dominated the airspace, cleared up French deployments, bombed battery stations, airfields and supply facilities.

The VII Reserve Corps under General Johann von Zwehl , disregarding these instructions, advanced to the Bois d'Haumont , which it was able to take after five hours of fighting. When General Schmidt von Knobelsdorf was informed about the German initial successes, he ordered: “Good, because you take everything today!” (In the sense of: Then conquer the rest of the area today as well). The XVIII. Army corps that was supposed to attack the forest of Caures and encountered the two reserve fighter battalions under Lieutenant Colonel Émile Driant , of which only a few had survived the barrage in their expanded positions, but which nevertheless defended their section to the last (of 600 men Target strengths were still operational between 110 and 160 in the evening). The III. Army corps was stuck in front of the French positions in Herbebois.

As a result of the first day it was found that, despite the massive artillery fire, the French resistance was much tougher than one had expected on the German side. About 600 German soldiers were killed or wounded on the first day of the battle. According to historians, if Crown Prince Wilhelm had ordered a direct, massive infantry attack in the early morning, the devastated positions of the French would have been taken and the Verdun fortress would have fallen. But as it was, the completely pointless struggle continued for months.

On February 22nd, the German army continued its attacks undeterred. The French soldiers defended themselves in scattered nests of resistance, but could not stop the German advance. Particularly fierce fighting occurred in the forest of Caures with the still living defenders of the chasseurs à pied ("hunters on foot") and Hessian troops, including infantry regiments 81 (Frankfurt am Main), 87 (Mainz) and 115 (Darmstadt). The 159 Infantry Regiment from Mülheim an der Ruhr succeeded in taking the village of Haumont . The Bois de Champneuville and the Bois de Brabant were also taken.

On February 23, fierce fighting ensued over the villages of Brabant and Wavrille and the Herbebois. A tragic event occurred particularly during the battle for Samogneux: German troops had captured Samogneux, but were repulsed shortly afterwards by a French counterattack. The French artillerymen from Fort de Vacherauville set fire to the village because they assumed it was still in German hands. In doing so, they caused heavy losses among their comrades (“ self-fire ”) and paved the way for the Germans for another attack that finally brought them control over Samogneux. No major successes were reported.

On February 24th, the XVIII. Army Corps Beaumont , with French machine-gun positions killing or wounding numerous attackers. Furthermore, the villages of Brabant, the Herbebois, the height 344, the Vaux cross and the forests of Caures, Chaume and Wavrille were taken. The two French divisions, which had to hold the front arc from the forest Herbebois to the Meuse (51st and 72nd), had a loss rate of around 60% on the evening of February 24th, which in connection with the lack of artillery support led to a dangerous weakening of the Morale contributed. The territorial gains the Germans had gained that day were the largest since the offensive began, so General Frédéric-Georges Herr considered evacuating the right bank of the Meuse, but ordered General Joffre to hold every position under threat of standing execution. The 37th Algerian Division and three regular infantry divisions were relocated to the front as reinforcements (16th, 39th and 153rd). Due to the clear air superiority of the Germans with 168 aircraft and a large number of tethered balloons , the French armed forces were forced to evacuate the apron in front of the fortified elevations (the plaine de la Woëvre ), since the well-guided guns of the Germans could shoot clear targets there.

On February 25, the Hessians reached the village of Louvemont and were stopped by several machine-gun nests. After a difficult two-hour struggle it was taken; the strength was no longer sufficient for a further advance. The great losses were not only due to direct machine gun fire, but also to the French artillery that was now on the other side of the Meuse in their rear. Now it became clear for the first time that the Crown Prince had been right in calling for an attack on both sides of the river. Furthermore, the German attacks were directed against the village of Bezonvaux , which was defended by the French 44 e régiment d'infanterie . The French put up bitter resistance, but the Germans were able to take control of the village by nightfall. At that time only ruins remained of Bezonvaux. On the same day German soldiers succeeded in a coup taking the Fort Douaumont .

February 25, 1916: capture of Fort Douaumont

The Fort Douaumont was built in 1885 as a modern French fortification in the defensive perimeter of Verdun. With the emergence and use of new types of hollow storeys , which were able to break through the stone and brick fortresses that had been customary up to that time, the renovation of the complex had to be initiated as early as 1888. The ceiling of the central barracks was reinforced with a concrete layer 2.50 m thick during the year, the eastern casemates received a layer of 1.50 m. It was hoped that these modifications would neutralize the destructive force of even the largest German bullets of 38 and 42 cm caliber, which was largely achieved. But now there was a change of ownership and it was not until late summer that the French hit the German hospital with a new 400 mm mortar . Even so, for a long time the fort was the safest place in the combat zone. Furthermore, in the course of the downgrading of Verdun to the Fortifiée de Verdun zone , most of the guns housed in Douaumont were relocated, so that only the Tourelle Galopin de 155 mm R modèle 1907 armored turret was available during the decisive German attack . This was manned by some Landwehr artillerymen who maintained fire on given grid squares.

The Brandenburg Infantry Regiment 24 from Neuruppin received the order on February 25 to entrench themselves about a kilometer from Fort Douaumont in order to support the action of Grenadier Regiment 12 against the village of Douaumont. The soldiers of the regiment worked their way up to the fort on their own, however, and threw back the French 37th Division defending outside. With the exception of the gunner's gunmen, the fort's garrison had withdrawn to the lowest casemates so that the Germans were not noticed. A non-commissioned officer (later vice sergeant) named Kunze discovered a shaft leading directly into the fort, which he could enter with the help of a human pyramid formed by his troops. When the gunners saw him, they immediately fled to the lower casemates to warn their comrades. While Kunze was exploring the top floor of the fort, Lieutenant Radtke , Captain Hans-Joachim Haupt and some of their soldiers also gained access. Lieutenant Cordt von Brandis joined them much later. The French garrison, consisting of 67 soldiers, was taken by surprise by about 20 German intruders - without firing a single shot - and forced to give up. The strongest fort in the defensive ring was in German hands, 32 attackers had been killed and 63 injured.

The news of the conquest of Douaumont was celebrated as a great victory in the German Empire. Numerous extra sheets appeared while the church bells were ringing in many places.

First Lieutenant von Brandis and Captain Haupt received the order Pour-le-Mérite , Lieutenant Radtke initially received nothing and after the war had to be content with a signed photograph of the Crown Prince. Shortly afterwards he was promoted to captain of the reserve. In France, after the Germans had taken Fort Douaumont, there was horror, as the fall of Verdun seemed imminent. The fact that the fort had fallen into German hands without significant resistance was perceived as a particular shame. Although Fort Douaumont had lost much of its importance before the German offensive began and was even intended to be blown up at times, it was decided on the French side that it should be retaken at any cost.

On February 26th the capture of some infantry works of the intermediate works Ouvrage de Hardaumont was announced, after which the attack had come to a standstill. From the sources of the OHL it can be deduced that this day was designated as the first on which one could no longer report any movement in the front.

General Pétain consolidates the French front

On February 26th at midnight, General Philippe Pétain , the Commander in Chief of the 2nd Army, who as Général de brigade had already stood before his retirement in the year of the outbreak of war, was appointed the new Commander in the front sector around Verdun. Since Pétain had faced the Germans as a front-line commander in the trench warfare, he realized that the Germans would never succeed in taking the "enemy positions one after the other in one attempt" . Accordingly, he recommended in a memorandum to his high command that very limited offensives be carried out, which should only go as far as their own artillery could offer protection. Similar to Falkenhayn, he argued for a war of attrition, in which victory is achieved after the opponent is exhausted.

With these considerations and the clear conviction that restricting the German attack to the right bank of the Meuse had been a serious tactical mistake, Pétain ordered that the inner defensive ring of Verdun should be expanded into a barrage position that he had designated , and that the guns were used for the attacks of Germans should bring them to a standstill at any time. He contracted ten batteries of 155 mm guns on the left bank, from where they inflicted heavy casualties on the VII Reserve Corps by shelling the flank. The French artillerymen had been given a free hand to operate according to their own needs and objectives, and also had a completely free view of the German positions, so that their gunfire was extremely accurate.

General Pétain's further measures included changes in French tactics to strengthen the artillery and the more effective organization of supplies. To supply Verdun he only had the road to Bar-le-Duc , which was the only supply line outside the range of most of the German artillery. It is unclear why a direct massive bombardment of this supply route by the German long-range guns was not ordered: The enormous concentration of vehicles and troops on this single street would have ensured panic and thus the direct interruption of supplies; only a few individual German guns fired at the street at irregular intervals, but this did not particularly hinder the supply of French supplies. This street was to be known in France as La Voie Sacrée ( named after the Via Sacra by Maurice Barrès ).

An endless stream of transport vehicles, requisitioned all over France, entered the city via the Voie Sacrée . If a car stopped with technical defects, it was simply pushed aside to prevent a traffic jam. A separate reserve division had the task of maintaining the road. The troops had to march in the fields next to the road so as not to interrupt the flow of transport vehicles. In the initial phase of the battle, 1200 tons of material and food had to be carried to the front on 3000 vehicles every day, but the vehicle fleet grew to over 12,000 vehicles during the battle due to confiscations throughout France. The safe supply via the “ Voie Sacrée ” ensured that the French army gradually became equal to the German attackers in terms of military equipment, troop strength and, above all, heavy artillery.

The Noria reserve system introduced by Pétain , in which the fighting divisions were relocated to reserve positions and other sections of the front after a brief front-line deployment, was still decisive for maintaining the French front : the short fighting times before Verdun noticeably reduced exhaustion and thus the failure rate of the troops and strengthened them thus morality and the spirit of resistance. By the end of the war, a total of 259 of the 330 infantry divisions fought more or less long before Verdun.

Pétain was ultimately also responsible for the new tactics of the air forces , which were deployed in squadrons against the German reconnaissance aircraft and were thus able to gain superiority . On March 6, Pétain turned to his soldiers and urged them to persevere against the Germans.

The commanding commander of the French 33 e régiment d'infanterie had noted by hand under this order that he could only add one addition, namely that the 33 e régiment of its former commander would prove worthy, that it would die if necessary but will never give way.

The fighting until early March 1916

A few days after taking Fort Douaumont, the German troops launched attacks on the village of Douaumont to the west. Supported by machine gunmen holed up in the fort's gun turrets, the Brandenburg 24th Infantry Regiment attacked the French positions in the village and were turned away with heavy losses. A Saxon regiment, the 105th Infantry Regiment , which also carried out an assault on Douaumont, got caught in its own gunfire and had to withdraw after heavy losses. An advance by the 1st Grenadier Regiment 12 under Captain Walter Bloem was just as unsuccessful . Particularly heavy fighting raged between February 27 and March 2. On February 27, the severely wounded French captain came Charles de Gaulle in German captivity . The French resistance was to be broken by the ever closer relocation of the German artillery to the front. By March 2, the Germans were able to completely occupy what was left of the village of Douaumont with the 52nd Infantry Regiment from Cottbus. The conquest of the village had turned out to be extremely costly for the German troops.

On February 27, the Silesian 5th Reserve Corps had received the order to take Fort Vaux , which was smaller and weaker than Fort Douaumont. In order to meet the expected attack, however, Pétain had given it a strong, defensive crew. The attack against Fort Vaux turned into a bloody slaughter, as the German troops from the higher Fort Vaux, from the village of Vaux, from the Caillette forest, but also from the other side of the Meuse were taken under fire. The attack was halted by French counter-attacks. On March 8th, the Germans took part of the village of Vaux and worked their way up to 250 meters from the fort. The French, however, held their position inside the fort, and from then on their artillery occupied the hilltop on the side of the attacking Germans with constant fire. On March 9, the hoax was spread that German troops had penetrated and the fort had fallen. When the German General Staff realized that the capture of Fort de Vaux had not happened, it ordered the actual capture of Fort Vaux. On March 10th, the German troops undertook several assault attacks, which failed with high losses of their own.

March 1916: German offensive against Höhe Toter Mann and Höhe 304

With the excellent tactical position of the French guns on the western bank of the Meuse and the resulting possibility of hitting the German attackers in the east in the rear, the OHL decided to extend the attacks on both sides of the river. The terrain on the west side of the Meuse had a completely different geography than on the east bank: no forest, no gorges, but open hilly terrain. Falkenhayn, Crown Prince Wilhelm and General Schmidt von Knobelsdorf gave in to the urging of General von Zwehl, whose troops had been permanently under fire from the left bank. In order to take account of the confusing fighting and to gain tactical advantages, the troops were combined to form new attack formations: on the east side of the Meuse on March 19, the Mudra attack group under General von Mudra , which comprised all corps in this combat area (April 19 renamed attack group east ).

On March 6, the planned major offensive of the attack group West by the VI. Reserve corps started. The 12th and 22nd Reserve Division went through after strong, preparatory artillery fire in two peaks to attack the French positions on the left bank of the Meuse. After fierce fighting, on March 7th they captured the villages of Regnéville and Forges and the strategically important heights of Côte de l'Oie (back of goose) and Côte de Poivre (back of pepper). The French 67th Infantry Division collapsed under the attack and over 3,300 uninjured prisoners were taken.

On the same day, the Germans advanced to the Bois des Corbeaux (raven forest) and the Bois de Cumières , which had a strategically important hill called Le Mort Homme ( “ Height of Dead Man ” ) in their northwestern foothills . This hill with two peaks (height 265 and height 295) got its name because of an unknown body found there in the 16th century. West of the Höhe Toter Mann is the Côte 304 ( "Höhe 304" ), named after its height above sea level , which was also the target of the German attacks. Behind these two hills stood the large gun batteries stationed by Pétain, which caused great losses to the German positions on the right bank of the Meuse. On the evening of March 7th, the German troops had occupied part of Höhe 304, but a determined French counterattack under Lieutenant Macker pushed them back on March 8th.

In another attack by the French on March 10, they suffered great losses, including Oberleutnant Macker, who fell through artillery fire. Robbed of their integration and leadership figure, his soldiers were in shock and withdrew. The Germans could finally take the Bois des Corbeaux and turn to the "dead man".

On March 14th, the Silesians finally managed to conquer the summit of Mort Homme . Small gains in terrain were presented by the propaganda of both sides as major milestones, for example the capture of the French positions northeast of Avocourt by Bavarian regiments and Württemberg Landwehr battalions on March 21, the storming of the ridge southwest of Haucourt two days later or the capture of the village Malancourt on March 30th by Silesians. Throughout March, the grueling and extremely brutal fighting dragged on with no clear outcome.

General der Artillerie Max von Gallwitz became commander of the attack group West on March 29 and prepared another attack there. As a reinforcement, the XXII. Reserve Corps under General Eugen von Falkenhayn arrived at the 5th Army and was also placed under the command of the 22nd Reserve Division on the west bank of the Meuse.

March 1916: French defense on the east side of the Meuse

On the right bank of the Meuse, the French could not be driven from their positions west of the village of Douaumont. They also held their strong positions on the Thiaumont Ridge with the Ouvrage de Thiaumont , the subsequent chain of infantry and ammunition tunnels, the Les Quatre Cheminées tunnels and the " Ouvrage D " further back, towards Verdun , the Ouvrage de Morpion for its shape (morpion = French for "felt louse"). The French also succeeded in holding Fort de Souville and the heights of Froideterre with the Ouvrage de Froideterre , from which they could seriously disrupt the strong growth in supply traffic of the Germans to Fort de Douaumont.

The Fort de Douaumont, however, had become a German depot for ammunition, medicine and food since its conquest and served the advancing troops as protection and to calm down from the storm; the combat value was rather low, because the existing Tourelle Galopin de 155 mm R modèle 1907 was defective; hence it was only used as a traffic light station from now on. The long and loss-making, but ultimately successful advance of Brandenburg and Hessian regiments against the Caillette Forest could no longer be protected and stabilized by the usual ditch systems. Because of the strong counterfire, the attacking German troops had to take up their positions in shell holes. In particular, the machine-gun positions on the opposite side of the Froideterre and Fort Souville dominated the area during the day, so that expansion, replenishment of fresh units and evacuation could only happen at night. A similar picture presented itself in front of Fort Vaux. The reserves of the Germans to maintain the stuck attack were led over an approach route over the dam of the Vauxteich, which the French artillerymen knew very well, could see and fire from the Souville nose (Nez de Souville). The daily fire claimed thousands of casualties until December 1916, and the route to the front was named the Path of Death .

April 1916: Nothing new in the West

Overall, the front line on the west bank of the Meuse got stuck along the ridges, and over the next 30 days the battle developed more and more into a pure artillery duel. The taking of the summit of the "Dead Man" by the Germans was answered not only militarily but also propagandistically by the French: They declared the second, southern summit, which they still held, to be the main summit, thus giving the Germans a symbolic triumph rob. On April 6, the OHL was able to report the capture of the village of Haucourt at the foot of the height 304 , at which about 540 prisoners were taken.

On April 9, the decision was made to start another offensive with a massive attack on the entire length of the now 30 km long front. On the first day, the German storm troops thought they had taken the summit of Height 304 , but the conquered ridge turned out to be just another fore ridge. Both the Höhe Toter Mann and Höhe 304 were now fired almost continuously by the guns on both sides in order to bring the attacks of the French and German infantry charging at the same time to a standstill with great losses and to eliminate the opposing gun emplacements. This goal has almost always been achieved.

Once positions were taken, they had to be expanded and protected against the inevitable counterattack. It was extremely difficult for the infantrymen to dig a trench because, in addition to the constant shell fire during the day, numerous enemy snipers were active while the earth froze at night in the cold April 1916. The struggle for the height of the dead man and the height of 304 had become a sign of a completely dehumanized war: the soldiers fell victim to the impacting grenades without even having seen an enemy. The French captain Augustin Cochin of the 146th Infantry Regiment, who was in position at the "Toten Mann" from April 9 to 14, saw not a single attacking German soldier in the first lines during the whole time. He described this hell like this:

“The last two days in icy mud, under terrible artillery fire, with no other cover than the narrowness of the trench… Of course the boche did not attack, that would have been too stupid… Result: I arrived here with 175 men and returned at 34 some of which have gone half insane…. They no longer answered when I spoke to them. "

After only four days, the latest German attack also stalled, this time also due to the pouring rain, which lasted almost continuously until the end of the month, forcing both sides to curtail their offensive efforts. Under the conditions of the Battle of Verdun, this meant that although an attack was still answered with a counterattack, it also meant continuous hand grenade combat, hand-to-hand combat with spades and bayonets, position expansion , but above all it was also called artillery fire, continuously, day and night . The large-scale offensives to take the mountain ranges were discontinued; the struggle west of the Meuse had already "bleeding out" both sides after 30 days. The successful resistance against the German attempts to conquer the Heights and Dead Man prompted General Pétain to write a message to the soldiers of the 2nd Army on April 10, in which he called on them to make even greater efforts. The confidence and unwavering steadfastness with which Pétain announced victory to his soldiers contributed much to his aura as the savior of France in the post-war period and made him a national hero. Throughout the month of April, Pétain ordered the violent defense against the German attempts at Fort Vaux and the mountain ranges 304 and "Toter Mann" and the simultaneous, relentless advance on his now central goal of retaking Fort Douaumont, a new flank open against the Germans. Throughout the month of April, French troops stormed in vain against the German positions in front of Fort Douaumont on the eastern bank of the Meuse and suffered horrific losses.

Pétain, the most popular general among his soldiers, who had largely avoided loss-making and hopeless assaults and always stood against the French military doctrine offensive à outrance , was praised from his post and promoted to commander of the French Groupe d'Armées du Center for his successful defensive battle . Officially, this performance was also given as the reason for his promotion after only two months in office before Verdun. Unofficially, one can see other reasons for the removal of Pétain: Joffre wanted to strengthen other sections of the front and, according to the agreements with the British, launch a joint attack on the Somme . If he did not want to jeopardize this great offensive, Joffre had to change the Noria system introduced by Pétain of the constant and rapid exchange of divisions before Verdun, as it tied more and more troops on the Verdun front. Contrary to the actual concept (attack by 39 divisions over 40 km wide), the French planned for this reason on April 26th with only 30 divisions over a length of 25 km for the attack on the Somme. When it came to the battle of the Somme , the GQG could only deploy twelve divisions 15 km wide. A change in the system, however, entailed a transfer of the system founder.

April to May 1916: Pétain's transfer - start of the French offensives

On April 28th, General Pétain was appointed leader of the Groupe d'Armées du Center , in addition to being in charge of Verdun's defense, he was also in command of the French 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th armies. The new commander of the French 2nd Army in the Verdun area was General Robert Nivelle , who sought to switch to more aggressive tactics and used his divisions on their front for much longer. To the liking of Joffre, he was a clear advocate of the pre-war system of offensive à l'outrance and made direct use of his authority. Over the next few months he repeatedly let his soldiers storm the German positions, hopelessly and brutally, without causing any major movement in the line. The French commanders obeyed the orders of the GQG and let their troops run against the positions of the Germans and defend their own trenches to the death, also to prevent the application of the instructions that every soldier, whether rifleman or general, from one Withdrawal would be demoted and court-martialed.

Meanwhile, displeasure made itself felt at the management level of the German 5th Army. Since the death toll had reached enormous proportions by May, Crown Prince Wilhelm asked the OHL to stop the offensive. Falkenhayn rejected this reluctantly, but strictly, as he still assumed higher losses on the French side and thus regarded the offensive as a success. It is doubtful, however, that he even considered an alternative strategy, because breaking off the battle would have been tantamount to admitting defeat. By the end of May more than 170,000 soldiers on both sides had either fallen or been wounded in Verdun, but as during the first two months of the battle, the small successes of both sides, even by the standards before Verdun, were turned into great victories. On May 8th, for example, the capture of a northern slope of the height 304 by the 56th Division was propagated as a great, strategic victory in which "of the unwounded prisoners only 40 officers, 1280 men fell into our hands" .

On May 13, 1916 the VI. Reserve Corps cleared by the General Command XXIV Reserve Corps under General Friedrich von Gerok with the 38th and 54th Divisions . The 4th Division remained in its old positions south of Bethincourt . On the right, the 2nd Landwehr Division supported with its attack in the forest of Malancourt, on the left of the Corps Gerok held the XXII. Reserve Corps with the 43rd and 44th Reserve Divisions on the western slope of the Höhe Toter Mann , the 22nd Reserve Division remained at the front in Cumières - and Rabenwald up to the Meuse.

The final capture of the Höhe Toter Mann and Höhe 304 was achieved by units of the German 4th Division and the 56th Division at the beginning and middle of May, respectively. Now their supply and reinforcement routes were in the middle of the enemy fire, which should prompt the Germans to build three access tunnels later in the battle. The French stepped up their attacks on the German heights, and close combat in heavy artillery fire continued.

May 8, 1916: Disaster at Fort Douaumont

Also on May 8, there was an explosion in the fiercely contested Fort Douaumont, nicknamed “coffin lid” by the Germans, and around 800 soldiers were lost. The incident is still partly unresolved and will remain unresolved, as all possible causes died in the explosion.

In addition, there are three not necessarily contradicting versions, which describe the catastrophe from different perspectives and at the same time reveal the extent of the uncertainty:

- First, it is established that parts of the 12th Grenadier Regiment and the 52nd Infantry Regiment from Brandenburg had withdrawn into the fort after another unsuccessful attack in the direction of Thiaumont on May 7, 1916, in order to rest for a further attack the next morning. When the 8th Grenadier Regiment, relocated to Douaumont to provide support, arrived in Douaumont on May 8th, shouts of “The blacks are coming!” Rang out as black faces had appeared in the stairs from the basement. The German soldiers were very afraid of the French colonial troops from Senegal and threw hand grenades down the stairs. This was the first explosion that was heard. The flying fragments caused a second explosion; a hand grenade depot ignited, the tremendous shock wave of which caused a ceiling to collapse that buried most of the soldiers under itself.

- Second, later investigations revealed that the flamethrowers stored in the basement must have lost oil that ignited in a jet flame. Why this oil had ignited could not be clarified. The soldiers who were engaged in extinguishing the fire got sooty faces from the smoldering fire and some tried to escape into the fresh air through the thick smoke. However, when the guards on the upper floor saw these blackened faces approaching, they threw hand grenades at them in a panic in the lower floor. These finally exploded a large ammunition depot, in which French grenades with a caliber of 155 mm, hand grenades, flame throwers, flares and artillery ammunition were stored. The resulting massive detonation blew up the ceiling of the basement. More than 800 people were killed as a result of the explosion, the pressure wave or the collapsing ceiling.

- Thirdly, it is stated that German soldiers wanted to warm their meager food by unscrewing stick grenades in order to ignite the explosives inside. Without the detonator, the charge burns slowly. The oil from the flamethrower ignited, which then triggered the well-known chain reaction.

The Germans began to collect the bodies in grenade hoppers outside the fort. However, as the number of deaths grew and the threat from the French artillery shooting increased, it was decided to place the dead in front wall casemates I and II and then wall them up. Where the large wooden cross now stands in Fort Douaumont, only an exit to the former courtyard is walled up - Casemates I and II, recognized as official German war graves, are 20 meters behind.

May 1916: Battle for Fort Douaumont

The French had always viewed the fall of Fort Douaumont as a great defeat and wanted to recapture the strongest and most strategically most important fortress in the defensive ring. After the disaster they observed, Nivelle decided to expand the attack on Douaumont that Pétain had started. Together with the commander of the 5th Infantry Division, General Charles Mangin , who also led the attack, he planned a major attack to take advantage of the weakened condition of the fort. From May 17, the French artillery began initial artillery fire and fired conventional and gas grenades at the German positions around the fort and the fort itself.

When the attack began on May 22, the commandant of the Douaumont could not react effectively because the connections between the first lines and the fort had broken off, the defenders had suffered heavy losses, the fort was partially destroyed and only poorly repaired by German engineers . Of course, the Germans were expecting the French stormtroopers, but their appearance just behind the last garnet curtain was surprising. The French had jumped the first trenches without significant resistance and occupied the southwest part of the fort. General Mangin informed Nivelle on the same day that the Douaumont was completely under French control, although the Germans now resisted resolutely after an initial panic. The fort was largely cordoned off by the French and German barrage against the enemy’s supply routes. After bitter and mutually unsuccessful hand-to-hand combat in the corridors of the Douaumont, the Germans and French mounted machine guns on different parts of the roof and fired at everything that moved. After two days of bloody combat, in which both sides had received reinforcements, the German commander of the fort decided to use heavy mortars. Among other things, these were used against the "Panzerturm Ost" held by the French. Then the Germans attacked the shocked French with hand grenades. Another unit had meanwhile bypassed the French corridors and appeared in their back. More than 500 French were taken prisoner.

Encouraged by this success, the Germans brought in further reinforcements, through the I. Bavarian Army Corps under Infantry General Oskar Ritter von Xylander , which was supposed to occupy the French trenches west of the Douaumont fort. Fresh soldiers arrived in the combat area after a long march from the rear and immediately had to experience the horror of the front. They had to tackle the positions on the Thiaumont ridge, which they finally reached with major failures. More and more there were now bloody losses on both sides due to worn artillery tubes, which shot their grenades into their own ranks due to excessive dispersion.

June 1916: Battle for Fort Vaux

After the region around Fort Vaux had been assaulted by the Germans for three months, the Cailletewald was finally captured on June 1st by the 7th Reserve Division from Saxony and Berlin. Furthermore, the 1st Infantry Division was able to advance against positions in the Bois de Fumin and on the Vauxgrund. Now that the flanking of the main attack on Fort Vaux was eliminated, the opportunity was taken to launch a new general attack on the fortress. This should start on June 2nd.

Fort Vaux is located on the Vauxberg between the forts Douaumont and Tavannes and was built between 1881 and 1884 using the stone structure customary at the time. As with Fort Douaumont, the arch of the barracks was reinforced in 1888 by a 2.50 meter thick layer of concrete, which was isolated by a one meter thick layer of sand. These reinforcements were intended to contain the terrible effect of the hollow floors. The fort of a Tourelle de 75 mm R modèle 1905 flanked by two steel observation domes ( Observatoire cuirassé ). It was surrounded by a ditch, which was secured by three trench swings; two simple ones from north to south and from west to east and one double in the northwest corner of the ditch. These positions were accessible through access tunnels and armed with machine guns. In addition to the upper cannon, two further 75-millimeter cannons were available in the casemates de Bourges , which allowed bombardment of the entire area: from the Douaumont, the ravins de la Fausse Côte , the Caillette and Bazil gorges in the north-west to the village and to the Damloup battery in the southeast. Communication tunnels were dug between 1910 and 1912, connecting the various defensive positions of the fort.

After the outbreak of war, the fort was reinforced by six further 75-millimeter cannons and four rapid-fire cannons ( canons revolver ), but in August 1915, in the course of the downgrading of the Verdun defense zone, the exploitation began: Except for the armored turret, its expansion was too complex all the guns were gradually removed. This was the state of the fort at the beginning of the German offensive off Verdun, during which it was hit several times by German shells. On February 24, it received a direct hit from a 42-centimeter shell that destroyed the mortar camp. On February 27, another 42-centimeter shell smashed the armored turret. The casemates de Bourges could no longer be armed with cannons because of the constant bombardment and destruction, so several machine guns were built in for defense. The greatest damage was makeshift repaired by engineers on the orders of the advanced commander Major Sylvain Eugène Raynal , ( 96 e régiment d'infanterie ).

Raynal did not become in command of Fort Vaux until the end of May; he was a professional soldier and was wounded several times in the war. His last wound was so severe that he could only walk with the help of a cane. He stubbornly insisted on a further assignment in the front line, which was finally granted to him: it was thought that the appointment to command a fort would be easy to accomplish even for a severely disabled officer. The fort had a crew of around 250 men in peacetime, but at the beginning of June 1916 over 300 soldiers were crammed together, as after the German successes in the flanks of the fort, many refugees, detectors and wounded had streamed into the supposed protection of the fortress. They consisted of 240 men, the 2nd battalion, the 3rd (machine gun) and the 6th company of the "142 e régiment d'infanterie", who were supposed to defend the facility together. There were also about 30 pioneers, about 30 colonial soldiers who carried out the repair work, and a handful of artillerymen, paramedics, ambulance workers and telephone operators.

On the evening of June 1st, the artillery preparation began; Raynal later estimated that around 1,500 to 2,000 shells per hour fell on his fortress. After the setbacks on the opposite slopes and the heavy rain of shells, only a few defenders of the 2nd Battalion of the "142 e régiment d'infanterie" lay in front of the fort, which had become a labyrinth of trenches, barbed wire, obstacles and machine gun emplacements. Only the Abri de combat R.1 and R.2 under Capitaine Delvert still covered the flanks of the fort. Around 4:00 in the morning, the assault troops of infantry regiments 39, 53 and 158 from Cologne and Paderborn began their attack. At dawn Delvert could watch the onrushing troops. "Like ants when you step into an anthill," they streamed from their ditches. Delvert could not interfere with this attack as his machine guns did not reach as far as the German lines. Within a few hours they had made great gains in terrain and appeared in the trenches adjacent to position R.1. Delvert immediately ordered violent counterfire, which initially stopped the German storm troops. At around 2:30 p.m., however, position R.2 was taken, position R.1 had received a direct hit. Delvert stood in the crossfire and commanded only 70 soldiers. The pre-defense of Fort Vaux was now largely off, the storm troops had gained about 1000 meters of terrain on June 2nd and were able to reach the blind corner of the fortress in the afternoon. They had simply bypassed the still defending Capitaine Delvert.

After a pause in gathering, the stormtroopers finally jumped into the completely destroyed trenches of the fort from which the machine guns were still firing. The casualties were high, but some soldiers crept up to the French positions and threw bundles of hand grenades into the loopholes; in another position they tried to turn off the machine gun with flamethrowers. Meanwhile the artillery fire on both sides had started again and drowned out the noise of the close combat in the trench. At around 4 p.m. the machine guns were switched off and the storm troops were able to take up positions on the roof of the fortress. Inside, Major Raynal pulled together his team of over 600 soldiers for defense and ordered the immediate expansion of the main corridors with sandbags that were equipped with machine guns. At the same time, some soldiers were supposed to attack the Germans lying on the roof, who, however, threw hand grenades into the exit shafts until the attack had to be stopped. The Germans discovered an entrance to the interior of the fort in the destroyed roof, lowered themselves on ropes and penetrated to a steel door, behind which they could hear the major's orders. When trying to blow this door with a hand grenade, some Germans were killed, others were injured because they could not find any protection in the corridors from the spreading pressure wave.

On the morning of June 3, the Germans had occupied two main corridors. The hand-to-hand fighting inside the fort was carried out with extreme brutality, with spades, bayonets and hand grenades. The power supply and thus the light had failed, but the fighting continued with incessant violence and in complete darkness, only occasionally lit by burning oil and the use of German flamethrowers. The tattered corpses were piled up in the 1.70 meter high and about 1.20 meter wide corridors, which were covered with chlorinated lime intended for latrine disinfection. The ground was slippery with blood from the wounded.

As soon as a defensive position was taken by the Germans, the French rallied shortly behind and started a counterattack with all available weapons. The summer heat was meanwhile on both sides, whereby the French could no longer count on water supplies, since the cistern had been destroyed by shell hits. An attempt was made to collect the water that ran out. In their sick quarters, a 10 square meter bunker room, the steadily growing number of wounded could no longer be treated because there was neither water nor light. This camp was normally intended for six beds; on the evening of June 2, more than 30 soldiers with very serious wounds were lying in the station waiting for the fighting to end.

The position R.1 in the apron still held out against the attacks by the Germans, but could not intervene in the fighting within the fort. At 10:00 p.m. Capitain Delvert, who had not slept for 72 hours, was informed of the arrival of a relief company, but instead of the announced 170 men, only 18 soldiers had escaped the German fire and all the others had died. Another company with 25 survivors reached position R.1 at 23:00.

On June 4, the Germans had captured another 25 meters of the main tunnel; However, Raynal was able to repel all further attacks by the flamethrowers with machine gun fire. The French had lost their observation posts and could only fall back on a small viewing slit that allowed them to see into the apron. They saw their comrades' desperate attempts to break out of the fort, but all six attempts of the day were repulsed by the Germans. A French company was completely lost in these battles: 22 men were taken prisoner, 150 died, none returned. At noon on June 4th, Raynal sent his last carrier pigeon behind his own lines with one last desperate message.

On Monday June 5, the Germans blasted another hole in the main corridor walls and attacked the French with flamethrowers, but the draft from the bunker sent the flames back and burned many of the German attackers. Major Raynal still held his position, there were now over 90 seriously wounded in the infirmary. He gave orders that the last of the water be distributed among the wounded. On the evening of June 5, Capitaine Delvert returned from his position R.1 to Verdun, he still commanded 37 men, with the exception of five all were wounded. On June 6, the French made a final attempt at reinforcement, which, like everyone else, was repulsed by the Germans.

Major Raynal's soldiers were utterly exhausted, some licking the slimy condensation off walls or drinking their own urine. Soon after, they writhed in stomach cramps , a desperate young lieutenant went insane and threatened to blow up a grenade dump. He had to be handcuffed. On the morning of June 7th, Major Raynal finally saw the desired optical signal from Fort Souville: " ... ne quittez pas ... ", but a few hours later at 7:30 am German time he gave up the fight and went into captivity with 250 men. everyone else was dead or wounded. The Germans lost around 2,700 soldiers in the attack.

After taking Fort Vaux, the French launched direct counter-attacks on June 8th and 9th and tried in vain to recapture the fort. The Germans expanded their position in Fort Vaux and continued to attack the French positions in front of Verdun over the next three weeks.

Brusilov offensive: weakening of the German troops off Verdun

Although the capture of Fort Vaux had knocked away another pillar of the eastern fortifications in front of Verdun and was viewed as a great strategic success, the pressure on the German army had increased enormously at the beginning of June. On May 15, the Austro-Hungarian Chief of Staff Conrad von Hötzendorf ordered a major attack, not agreed with the OHL, on the Italian positions north of Lake Garda, a "punitive action" in the flank of Cadorna's incessant attacks on the Isonzo. The fact that Italy increased its combat-ready divisions from 36 to 65 by 1916 and that 35 of the 65 Austrian divisions were tied to the Italian front was the basis for Hötzendorf's decision to view Italy as the most important enemy at the moment. He intended to defeat Italy quickly in order to be able to throw all the resources freed up against Russia afterwards. Although he had clearly stated his long-term goals with regard to Italy several times and also tried to persuade Falkenhayn to take joint action in the Alps, the order to attack came as a surprise and forced Germany to take unwanted stabilization measures in the east.

This had become necessary because the Russian high command seized the opportunity presented by the withdrawal of several Austro-Hungarian divisions in order to fulfill its contractually established alliance obligations in Chantilly with a large-scale offensive. From June 4th this offensive began, which was named after the commanding General Brusilov offensive . The onrushing Russian units made a number of breakthroughs in Galicia and the front of the Austro-Hungarian 4th Army collapsed completely over a width of 75 kilometers. The Russian troops penetrated 20 kilometers deep into enemy territory and took over 200,000 prisoners, mainly among the Austro-Hungarian troops. On June 15, Conrad von Hötzendorf declared the Russian attack to be the worst crisis of the war. And although Falkenhayn urged von Hötzendorf to meet the Russians by transferring troops from Italy and waiting for troops to be displaced from the north-eastern front of Hindenburg, he was forced to withdraw four divisions from Verdun in order to stop the Russians' further advance and, even more, the To prevent collapse of the ally.

June to October 1916: German offensive against Fleury , Thiaumont and Côte Froide Terre

Despite the smaller number of operational soldiers, Falkenhayn decided to continue the German offensive off Verdun, especially under the influence of the fall of Fort Vaux. General Schmidt von Knobelsdorf worked out with his staff the immediate continuation of the attack in the Fort Vaux area, which was to be directed against Fort de Souville , the Ouvrage de Thiaumont and the village of Fleury-devant-Douaumont.

The German army was able to muster 30,000 men for the attack, including the soldiers of the Alpine Corps , which had recently arrived on the western front and was considered an elite unit. Knobelsdorf hoped for a quick breakthrough through the first use of grenades with diphosgene as lung warfare agent , also known as the green cross due to the color and shape of their markings on the bullet and cartridge .

The large German attack was to begin on June 23 on a front width of three kilometers, which in turn had been prepared by heavy artillery support on the French positions at Fort Souville from June 21. A total of 100,000 shells were fired. Most recently, the German troops fired thousands of Grünkreuz grenades at the French gun batteries to deprive the French infantry of their most important support. The impacted projectiles did not explode directly and were initially mistaken for duds by some French. Within a short time, however, the diphosgene developed a devastating effect among the French troops: the French gas masks of 1916 only partially protected their wearers from this new weapon. Many French fled in panic, while others held their positions in agony. The gas attack was followed by another heavy bombardment that lasted into the early hours of June 23rd. When the gunfire ceased at 7:00 a.m., the German infantrymen left their trenches and started the assault. The soldiers of the Bavarian regiments reached the village of Fleury very quickly, because many French trenches were no longer occupied and could offer little resistance. Fleury was almost completely taken, with the exception of a part around the former station, but the German stormtroopers suffered high losses from the artillery fire on both sides. On the right slope, the regiments stormed against the ridge of the Côte de Froide Terre , on which the fortified facilities of the Ouvrage de Thiaumont, a large number of batteries and smaller bunkers were defended by units of the French "121 e régiment d'infanterie".

After a fierce battle that only 60 defenders survived, Thiaumont was captured. From there, four strongly weakened Bavarian companies advanced to the actual Côte de Froide Terre . Here the Germans found themselves for the first time on the side of the Côtes Lorraines sloping towards Verdun , but they never saw the city. Parts of the Bavarian infantry body regiment took the ammunition rooms ( poudrière ) below Fleury and sent a small group of three men to the felt exhibition ( Ouvrage de Morpion ), who returned with about 20 prisoners. After a bloody battle with the “114 e régiment d'infanterie”, however, they had to give up the ammunition rooms and retreat to Fleury. However, the attack against Fort Souville stalled.

In these unfavorable positions, the German soldiers had to endure the thirst of the summer heat, while beside and below them countless dead rotting and wounded crying for help. The very long approach to the Thiaumont intermediate plant was littered with fallen soldiers who sometimes served as signposts. Every groundbreaking to expand the position in the lunar landscape brought human parts to light. The stench over the battlefield was almost unbearable even for soldiers who were used to death and suffering. There are reports that food and water that were brought in tasted of decay even with great losses. The teams had to march at night, always in fear of being recognized in the glow of a French flare and shot by the French machine-gunmen. During the day, the positions were exposed to the low-flying attacks of the French air forces, now operating in absolute air superiority, which also directed the fire of their artillery very precisely at the respective target. Soldiers were often disoriented and wandered around the area for hours, and they were lucky to be captured by the French.

On June 24th, British and French troops launched the Battle of the Somme with huge gunfire . In order to counter this great danger to the German front, the OHL had to withdraw further units from the Maas area. In particular, heavy and heaviest artillery had to be brought back to the railroad through the impassable funnel field. In addition, the ammunition supply was diverted to the Somme, so that further offensives in the Verdun area had to be stopped. From June 25th to 30th, French counter-attacks lost the advanced positions. On July 3, a final attack on July 11 was approved, but with the stipulation that the ammunition reserves would be spared as much as possible, even if people would have to be killed for it.