Third Battle of Flanders

| date | July 31 to November 6, 1917 |

|---|---|

| place | Around Ypres , Belgium |

| output | Allied land gains, elimination of the German submarine bases in Belgium fails, however |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

|

|

|

| losses | |

|

310,000-325,000 soldiers |

217,000–260,000 soldiers |

The Third Battle of Flanders in World War I was an attempt by the Allies on the Western Front to achieve a breakthrough in the Ypres area , hence the name Third Ypres Battle . It began on July 31, 1917 and ended on November 6, 1917 with the conquest of the village of Passendale (Passchendaele) . The confrontation, one of the outstanding material battles of the First World War, is counted among the four battles of Flanders .

The aim of the Allies was to invade Belgium and to liberate the ports on the Belgian coast occupied by the Germans - from here they attacked British ships. They wanted to break through the German defensive belt on the West Flanders ridge; the first thing to do was to conquer the village of Passchendaele .

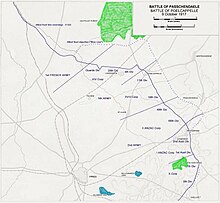

The Third Battle of Flanders was broken down into several battle names by the attacking English because of its length of months. The opening battle of June 7 was called the Battle of Messines and was intended to divert attention from the main offensive that began on July 31 with the Battle of Pil (c) kem . From August 16, the fighting was concentrated at Langemarck , from September 20 at Menen and from September 26 in the battle in the Polygon Forest . The later offensives are known as the Battle of Broodseinde (October 4th), the Battle of Poelcapelle (October 9th), the First Battle of Passchendaele (October 12th) and from October 26th until the Battle of Flanders subsided as the Second Battle of Passchendaele .

The British were unable to break through on the western front and neutralize the submarine bases on the Belgian coast. The gains in land were nominally quite significant (around 50 square miles or 130 km²), but were bought at the cost of enormous losses (soldiers and war material). That is why the Flanders Offensive now stands for the brutality and senselessness of this war.

initial situation

The war year 1917 was marked by the collapse of the Russian Empire . After Romania was largely occupied by the Central Powers at the end of 1916 / beginning of 1917 , the eastern front was essentially calm. The signs of disintegration in the Russian army were already evident in the spring of 1917. The German western front had been significantly shortened by a withdrawal movement ( company Alberich ) to the Siegfried position in March 1917 in order to save forces, whereby the western allies came under pressure.

The Allies launched several major offensives on the Western Front that did not bring about any significant changes. The reasons for this were poor planning, the underestimation of German combat strength, the poorly planned use of new weapons such as tanks and artillery, and ultimately the exhaustion of the material . In April the British attempted a breakthrough in the Artois ( Battle of Arras , April 9th to May 16th) and the French a week later on the Aisne and Champagne (April 16th to the end of May) a breakthrough. They used more troops and guns than in the Battle of Verdun . The result, however, were great losses, especially on the French side. There were mutinies , to which the French military command first with draconian punishments (hundreds of death sentences responded). The French commander-in-chief on the Western Front and namesake of the offensive, General Robert Nivelle , had to vacate the post he had taken over in December 1916 in May 1917. His successor, General Philippe Pétain , largely restricted himself to the defensive for the remainder of 1917 and brought the mutinies under control through better food and rest periods to protect the troops. There was a gradual improvement in morale.

On February 1, 1917, Germany declared unrestricted submarine warfare , putting the British navy and merchant fleet under pressure. But this also had the consequence that the USA entered the war against Germany (on April 6, 1917), which the German army command greatly underestimated. The greater effects of this entry into the war only became apparent in the war year 1918 , when they were ultimately decisive for Germany's defeat. In spite of its official neutrality, the USA was rather inclined to the positions of the Entente; At that time, many counted on entering the war (sooner or later) in their favor. US President from 1913 to 1921 was Democrat Woodrow Wilson . He had been re-elected in the presidential election of November 1916 and had led his country to war after the increased number of submarine incidents and the Zimmermann dispatch .

planning

The British Commander in Chief Sir Douglas Haig was planning an operation in the Flanders area as early as 1916 . These plans were postponed because of the Battle of the Somme (July 1 to November 18, 1916). The Battle of Fromelles in July 1916 was just a diversionary attack for the Somme Battle in Flanders. For the spring of 1917, a Franco-British double offensive was initially scheduled at Arras and on the Aisne , which did not lead to the desired success. As a result, Haig turned back to Flanders - also because the bulk of the French army was unable to carry out coordinated operations for months due to severe mutinies . His long-cherished intention was a breakthrough to the Belgian coast in order to conquer the German submarine bases at Ostend and Zeebrugge and thus eliminate the danger posed by the German submarines. It was also intended to shorten the front line and enable German troops to be encircled.

As with the Somme Offensive, Haig believed that the German army was on the verge of collapse. Prime Minister David Lloyd George was very critical of the offensive, but approved the plans.

In order to ensure a success of the main offensive, the German positions of the Wytschaete-Bogen on the ridge of the Wijtschate and Mesen ( Wytschaete and Messines ) had to be captured, otherwise no attack on the submarine bases was possible.

Introductory battle

On the morning of May 21, 1917, the British under General Herbert Plumer opened the attack against the Wytschaetebogen with 2,000 guns. The German positions were fired at continuously for 17 days.

The actual Battle of Messines began on June 7th at 3:10 am with the demolition of 19 mines . The explosions almost completely destroyed the positions of the 40th Division , which was being relieved, and the Bavarian 3rd Division . Other mines detonated in the section of the 2nd and 35th Divisions to the north . Around 9,000 soldiers fell or were captured, mostly buried or already cut off from the enemy. This led to the German preparations for a defense collapsing. Nine Allied divisions then went on the attack and were supported by the use of poison gas and 72 tanks . The entire German position was taken within three hours, the emergency divisions in reserve ( 7th Division and 1st Guard Reserve Division ) could not be brought forward quickly enough due to the rapidity of the action. The front line fell completely into British hands in heavy fighting until June 14th.

The Battle of Messines or Mesen is considered to be one of the few relatively successful offensives in World War I and strengthened the morale of the Allied troops. Plumer wanted to continue the attack, but was held back - as the troops were to be refreshed and defensive positions built.

Planning the main attack

In the British GHQ in the summer of 1917 violent disputes took place over the best way to achieve the goals set. While the corps commanders and many staff officers who were well acquainted with the conditions mostly preferred an approach in well-planned, rather short stages, Haig and Hubert Gough , the commander of the 5th Army planned for the main attack, tended towards an all-important, overwhelming one Breakthrough attack too. For the first phase of the attack, he defined three target lines (“blue”, “black” and “green” line), each of which required a gain in terrain of 1000 to 1500 meters. According to Gough's ideas, the green line should already be reached on July 31st, including Langemark and the Zonnebeke , which is already behind the “Wilhelm Line” at the foot of a dominant ridge , should have been taken. Gough also laid down a fourth, the “red” line, which Broodseinde , 1 km east of Zonnebeke, directly on the ridge, would have brought into the possession of the British and was planned for the following days.

First phase

Start of the offensive on July 31st

On July 31, 1917 at 3:50 a.m., after 15 days (since July 16), extremely violent artillery bombardment that ultimately increased to an unprecedented intensity, the actual major offensive in Flanders began. The Battle of Pilkem as the first offensive was led by the British 5th Army (initially 18 divisions in four corps ) and by the French 1st Army under General Anthoine through the attack of three divisions against the group Dixmuide ( XIV Army Corps under General Chales de Beaulieu ).

The German 4th Army under the Commander-in-Chief General Sixt von Armin , who had been supported by Fritz von Loßberg as Chief of Staff since the Battle of Messines , had used appropriate reserves for defense. As a defense, the Germans had been using mustard gas ( yellow cross ) since July 12th , which not only attacked the respiratory tract, but also the skin. It was one of the first uses of this then new warfare agent .

General Gough deployed nine divisions between Boezinge and Zillebeke for his first major attack against the German group Ypres ( III. Bavarian Army Corps under General Hermann von Stein ) . In the north attacked the XIV. (38th and Guard Division ) and XVIII. Corps (51st and 39th Divisions) of Generals Lord Cavan and Maxse against St. Julien, in the middle the XIX. (55th and 15th divisions) and II. Corps (8th, 18th and 24th divisions) under Generals Watts and Jacob against Frezenberg and the plateau west of Gheluvelt . During the advance they encountered the five-fold ring of the German defensive positions behind the front line: the Albrecht position , the Wilhelm position , the Flanders I position , the Flanders II position and the Flanders III position , which is still under construction ; in between were the Belgian villages of Pilckem, St Julien, Frezenberg, Gheluvelt, Zonnebeke and Passchendaele. The front German trenches were only very lightly occupied due to the incessant bombardment, only individual machine-gun nests obstructed the attacking troops. The British soldiers were mostly amazed at how few German dead were to be seen. The losses that occurred on the German side were mostly the result of counter-attacks by the intervention divisions deployed behind the front .

The subsequent British 2nd Army under General Plumer accompanied the attack with two divisions of their northern group (X and IX Corps under Generals Morland and Hamilton-Gordon ), which were heading towards Zandvoorde and Houthem against the German group Wytschaete ( IX. Reserve Corps under General Karl Dieffenbach ) attacked in the direction of Menin . The Allied soldiers were supported by around 220 tanks (136 of which were deployed on July 31st), but many of them got stuck in the deep craters created by the artillery fire or in the churned underground. As usual in previous large-scale attacks, the heavy bombardment with 3,000 guns had warned the German defenders in good time so that the British aim of conquering the Strait of Menin could be repulsed and only small gains in terrain could be recorded.

The front of Group Ypres was torn open, the affected 3rd Guard Division , the 38th and 235th Divisions were pushed back between Grafenstafel and Zonnebeke. But then the German intervention divisions ( 50th Reserve Division and 221st Division ) succeeded in stabilizing the front.

The German 40th and 111th Divisions , which formed the left wing of the Dixsmuide group, were temporarily pushed back between Bixschoote and Pilkem behind the Steenbeek.

31,000 Allied soldiers died on July 31, were wounded or went missing. That was significantly fewer than on the first day of the Battle of the Somme (July 1, 1916; 57,000 casualties, 19,000 of them dead), but here too the battle turned out to be extremely traumatic for the attackers due to the German bombardment, which was still strong despite everything.

A heavy rain that began in the afternoon of July 31 and continued for the next few weeks with only small interruptions turned the battlefield into a huge mud field, which only allowed progress in small stages. The situation was exacerbated by the fact that the British shelling had destroyed the drainage canals. To allow the troops to move around, wooden slats were laid as footpaths. The soldiers, who carried about 45 kg of material, ran the risk of drowning if they slipped off these paths. In addition, the German artillery was able to shoot its way into these narrow paths, which caused high losses. The trenches were flooded, which among other things led to sleep deprivation, and the use of tanks was now no longer promising.

The continuation of the offensive in August

On August 10, the British II Corps carried out an attack in its sector aimed at reaching the "black line", which met a well-prepared German defense and achieved little success, mainly taking the Westhoek Ridge at Potyze .

On the morning of August 16, 1917, the next British offensive began between the Yser and Lys , also known as the Battle of Langemarck . The British managed to break into Langemarck and fight their way to Poelcapelle. To the north of it Drie Grachten was taken, but the hoped-for breakthrough could not be achieved this time either. He failed again because of the dogged German defense. The front now curved back north of Bixschote towards the Houthulster Forest.

On August 17, the German 54th Division on the left wing of Group Ypres , reinforced by parts of the 3rd Reserve Division , was able to withstand all attacks. In the center of the group, however, the Bavarian 5th Division had to leave the remains of the destroyed village of St. Julien to the enemy.

On August 22nd, the right wing of the 5th Army attacked with the II Corps (Jacob) along the road to Menen, but bought small gains in land with heavy losses. The English major attack on that day at Group Ypres was directed against the 26th Division , 12th Reserve Division and 121st Division as well as against the right wing of Group Wytschaete with the 34th Division and the 9th Reserve Division .

On August 23, the general command of the XIV Army Corps was replaced on the German side , and the staff of the Guard Corps took over the leadership of the Dixmuide group for the next two weeks . In the Ypres group (General von Stein), a new section of the battle was formed when the 204th Division was brought up to the seam between the 26th Division and the 12th Reserve Division.

At the end of August, the attack by the British 5th Army had to be stopped for the time being due to the deterioration of the weather.

The French 2nd Army at Verdun led from 20.-26. August and from 7th to 8th September carried out strong diversionary attacks in which four corps were used. The Eleventh Battle of the Isonzo , which began on August 17 and represented Italy's most determined attempt to break the stalemate in the war of positions on the Austro-Italian front , also served in part to support the British offensive in Flanders.

Second phase

New commanders, new tactics

Haig changed the commander of the Gough offensive by moving his area of command further north, and at the end of August commissioned General Herbert Plumer to lead the main attack area. Thanks to his clever tactics, Plumer was able to conquer the front line at Messines without heavy losses in June. Plumer planned some smaller land gains based on the principle of “ bite and hold ” (German: to bite off and hold a piece of land ), and it was attacked several times in the course of September and October. The main task of Plumer's 2nd Army was to take possession of the Gheluvelt plateau, where the two southern corps of 5th Army had failed and suffered great losses. The 5th Army was now primarily assigned the task of protecting the left flank of Plumer's army in these attacks.

In mid-September, the Australian-New Zealand Corps replaced the exhausted II Corps. On September 17 and 18, Haig visited the individual general commands of each army in order to discuss how to proceed with the staff officers.

With the Germans on September 9th, General Command III. The Bavarian Corps was detached from the main attack area, the leadership of the Ypres group was now taken over by the Guard Corps under the newly appointed commander Alfred zu Dohna-Schlobitten . The released General von Quast took over the leadership of the German 6th Army . Shortly beforehand, the Dixmuide group had also been placed under the new leadership of the Guard Reserve Corps under General Marschall von Altengottern .

The increasing preponderance of British artillery prompted the German army commander, General of the Infantry Sixt von Armin, to reinforce the positions with additional bunker constructions since the German retreat on the Hindenburg Line . The high water level and the frequent rainfall showed the German army command the inadequacies in the Flemish trench warfare. Concreted shelters (see also “ Pillbox ”) now particularly crisscrossed the positions in the area east of Ypres, these offered the front troops at the front better defense opportunities in the event of bombing.

Plumers attacks in September and October

On September 20, General Plumer carried out a new major attack on the Strait of Menen (Menin) , including the I. ANZAC Corps under General Birdwood. 1295 guns were used, which corresponded to a gun on a front width of five meters. But also Plumer's attack achieved a gain in terrain of only 1.4 km, but the British casualties amounted to 21,000 soldiers. After several attacks on September 22, the Allies managed to gain another 800 meters deep terrain on the road to Menen.

On September 26th, Plumer undertook an attack on the Polygon Forest, deployed alongside the divisions of the British X and IX. Corps also includes the divisions of the two ANZAC corps. Terrain south of Zonnebeke to the polygon forest was stormed.

The Battle of Broodseinde began on October 4th , south of Zonnebeke , a dangerous front indentation was created in the section of the German 4th Guard Division . The 17th Division was deployed as an intervention division , this time in the section of the 19th Reserve Division . Here, in cooperation with the other units of the front section, it succeeded in pushing back the English units that had collapsed over 2 km. This also made it possible to bring the heights in the north-west of Gheluvelt, the western part of the Polderhoek Castle Park and the town of Reutel back under German control. During the attacks, the British had conquered a strip of land about 1.8 km deep, again with the loss of almost 30,000 soldiers. The front then ran from Broenbachgrund near Koekuit through the eastern part of Poelcapelle via Keerselarhoek and Nieuwmolen east past Broodseinde to the plateau to Beselare, from there to the western edge of Gheluvelt.

Battle of Poelcapelle on October 9th

Haig demanded greater land gains and felt strengthened in his belief that the German army was on the verge of collapse. Another attack by the British XVIII. Corps (11th (Northern) and 48th (South Midland) Divisions) started at Poelcapelle on October 9th . The XIV Corps (Guards, 4th and 29th Divisions ) took possession of the area south of the Houthulster forest to the north; further land was gained south of the Roeselare-Ypres railway. Before Passchendaele, the German 195th Division lost some ground, at noon the 240th Division , acting as the intervention division, was deployed behind the right wing of the Ypres group and deployed against the break-in point at Poelcapelle.

On the right wing of the battle front, Plumer had deployed the X. Corps (Morland) and the I. and II. ANZAC Corps under Generals Birdwood and Godley on a broad front between Merkem and south of Gheluvelt. The British 49th (West Riding) and 66th (2 East Lancashire) divisions were assigned to the II. ANZAC Corps in the Zonnebeke area until October 11th, after which they were replaced by the 3rd Australian and New Zealand divisions. In the German Wytschaete group , the 22nd Reserve Division , the Bavarian 10th Division and parts of the 15th Division were attacked. Between Broodseinde and Keiberg, the left wing of the 233rd Division had to retreat from the Australians. The new British attack had failed anyway, the Germans even managed to regain lost ground in a counterattack.

First Battle of Passchendaele on October 12th

Three days later, Haig made another attempt to break through the German front. In a narrower sense, only the following battle and a subsequent operation after the village of Passendale is referred to as the Battle of Passchendaele . Nevertheless, the term is also used in the English-speaking vernacular for the entire Third Battle of Flanders.

On October 12th around 6:30 am the barrage started between Draaibank and Zandvoorde against the German corps groups Dixsmuide, Ypres and Wytschate. An hour later, the infantry attack against the German group Ypres (General Command of the Guard Corps) followed, which was waiting for the attack and had already alerted its intervention divisions. In the area of the English XIV Corps (Lord Cavan) between Poelcappelle and the Houthoulster Forest, the 12th Brigade of the 4th Division, the 51st Brigade of the 17th Division and the 3rd Brigade of the Guard Division were destined to attack. The main attack led the II. ANZAC Corps under General Godley on a narrow front of 2,700 meters against Passchendaele. On the northern flank of the New Zealanders, the right wing of the British 5th Army supported. In the area of the XVIII. Corps (General Maxse), the 26th Brigade of the Scottish 9th Division (Major General Lukin ) was deployed to a width of 1,800 meters to advance to the hamlet of Goudberg. The English lay north-west of Paschendale in such boggy positions that they were happy with every opportunity to gain firmer ground and a better view of the ridge to Westroosebeke. The 55th Brigade of the English 18th Division was destined to attack Lekerboterbeek. For better coordination, the rifle bunkers in the area were given names such as Israel, Potsdam, Juda, Waterfields, Anzac, Helles, Kit, Kat, Hamburg and the like. a., the bunkers and the two hamlets of Wallemolen, Mollelmarkt and Goudberg north-west of Paschendale became the focus of the fighting that followed.

The attack still took place under poor weather conditions, so that the artillery could not be brought sufficiently close to the front line of the battle and the attacking soldiers without fire protection could only advance very slowly. The New Zealand Division (Major General Russell ) was deployed against the hamlet of Wallemolen, along the way via Bellevue on Laamkeek. The Australian 3rd Division (General Monash ) was assigned south of it, against the heights and on the village of Passchendaele, where the German 195th Division defended. The first operational objective was practically the same as the attack on October 9th, the attacking troops should fight their way forward about a kilometer, gather at the bunkers there and then fight the other 800 meters to the village of Passchendaele in a second attempt. It was the task of the I. ANZAC Corps (Birdwood) to the south to attack with the newly inserted Australian 4th and 5th Divisions at a front 1200 meters in the direction of the village of Keiberg and to attack the flank to the south against the German 220th and 233rd. Cover division . The X. Corps under General Morland (7th and 23rd Divisions) had to carry out attacks over the railway line Gheluvelt - Becelaere, while the IX Corps (19th and 37th Divisions) covered the southern flank to Zandvoorde.

From the train station northwest of Poelkapelle, the English 17th Division advanced on both sides of the road to Manneken-Ferme as far as the Schaap Balie area, so that they could advance immediately south of the Houthulster Forest. The village of Poelkapelle was lost to the German 240th Division , the English 18th Division, which had been assigned to Westroosebeke, stood close to the hamlet of Spriet that evening. The artillery fire of the ANZAC Corps had not completely destroyed the barbed wire blocking the front ledge at Wallemolen and on the slopes of Goudberg. The muddy ground did not provide a stable platform for the guns and howitzers that had been drawn. North of the Gravenstafel-Metheele road, the New Zealand division gained some ground, but was then stopped by barbed wire barriers and suffered heavy losses from machine gun fire.

The total number of casualties of the British 2nd and 5th Armies on that day was estimated at around 12,000 men, of which 2000 were missing since October 11th. The Australian 4th Division alone lost about 1,000 men, the Australian 3rd Division had lost 3,199 men and the New Zealand Division 2,735 men. On the German side alone, the 195th Division deployed in the focal point near Passchendaele had to complain about 3395 men since October 7th. Morale on the Allied side fell sharply as a result of these defeats.

Between the Dixsmuide and Ypres groups , the German Army Command had to pass the General Command of the Guard Reserve Corps (Freiherr von Marschall's group) as a newly formed Staden group (16th, 27th and 227th , from October 18th, through the 239th ) to reinforce the threatened section Division relieved). The General Command of the XVIII. Army Corps under Lieutenant General Viktor Albrecht took command of the Dixsmuide group .

After new British attacks, which were initiated on October 22nd against the southern edge of the Houthulster Forest, the German army command also expected new attacks against the front in front of Passchendaele. Almost all units of the Staden and Ypres groups were relieved as a precaution, the 187th, 195th, 220th and 233rd divisions were withdrawn from the front and their sections were newly manned for the next major battle.

Second Battle of Passchendaele from October 26th

The now exhausted II-ANZAC Corps was replaced by the Canadian Corps on October 15 . The Canadians had a special reputation on the Allied side because of their successful missions on the Western Front. In August, by storming Hill 70 near Lens, it had bound numerous German divisions for weeks that could not be used in the Battle of Flanders. The Australian 1st (General Walker ), 2nd and 5th Divisions (General Hobbs ) remained in their previous positions within the I. ANZAC Corps for the following battle on both sides of Broodseide. By October 18, 1917, the Canadian 1st (General Macdonell ) and 2nd Divisions (General Turner ) had taken their positions in front of Passchendaele, behind which the Canadian 3rd (General Lipsett ) and 4th Divisions (General David Watson ) were made available for follow-up . The leader of the Canadian Corps, General Arthur Currie , told Haig that the capture of Passchendaele would cost around 16,000 soldiers their lives, but Haig insisted on carrying out the attack.

The attack began on October 26th and at 7 a.m. the barrage started from the western edge of the Houthulster forest to Zandvoorde. On the north flank attacked the English XIX, which was again in the front. Corps together with the XVIII. Corps in the direction of Westroosebeke. The Canadians led the main thrust in the middle, the reinforced British X. Corps attacked with four divisions between Becelaere and Gheluvelt. The German defense of the "Gruppe Staden" (General von Marschall) was led by the 5th Bavarian Reserve and the 239th and 111th Divisions . In the "Gruppe Ypres" (now under General von Böckmann ), which held Passchendaele on both sides, the 11th Division on the right and the 238th Division on the left were deployed in the front, while the 11th Bavarian Division (General Kneussl ) acted as intervention reserve .

On October 30, the Canadians' new attack was directed against the entire section of the 238th Division (General von Below ) and against the northern part of the 3rd Guards Division (General von Lindequist ), which had moved to the left of it . On the right wing of the "Ypres Group", which stretched over Goudberg and Mollelmarkt, and in the area of the 11th Division on the left , British and Canadian troops penetrated the Paschendale area. After heavy fighting the village was taken. The 238th Division counterattacked, supported by artillery, to retake the partially evacuated and almost completely destroyed village and the already lost main battle line .

The defense of the "Gruppe Staden" north of Passchendaele against the English 58th and 63rd Divisions was strengthened by the arrival of the 4th Division , that of the southern "Gruppe Ypres" by the 44th Reserve Division . It was not until November 6 that the Canadians, with the help of two British divisions, were able to conquer the village of Paschendale and the surrounding hills and hold on to the gains until further reinforcements arrived. This week-long and successful attack, however, claimed the 16,000 casualties of men as predicted by General Currie.

After Haig sought the decision in the Battle of Cambrai , the British leadership stopped the offensive in the area east of Ypres on November 10th.

Result

The offensive near Ypres failed and the planned breakthrough was not achieved. There were heavy losses on both sides. There is still uncertainty about the number of victims, especially with regard to the number of wounded, as these were recorded differently. On the Allied side, one can assume up to 325,000 casualties, for the Germans up to 260,000 soldiers. Individual researchers come up with even higher numbers. The Allies celebrated the offensive because of the conquest of Passendale as a success.

The aim of destroying the German submarine bases from land was also not achieved by the fighting.

The tanks failed on the muddy battlefield in Flanders. Another major offensive was planned in front of Cambrai , in which the tanks should show their superiority. The British made good progress there, but were pushed back by German counter-attacks.

The 1917 British land gains in Flanders were recaptured during the German spring offensive in 1918 .

losses

The losses of the British Expeditionary Force during the period July 31 to November 19, 1917 are stated in the War Department's works as follows:

- Fallen: 3,118 officers, 47,217 men, total 50,335

- Wounded: 11,481 officers, 224,269 men, total 235,750

- Missing: 924 officers, 37,181 men, total 38,105

The British total losses for the period are thus 324,189.

The German casualties are stated in the medical report on the German army as follows: The German 4th Army was involved in the battle from August 1 to November 10, 1917. A total of 95 different divisions were deployed. The average actual strength of the 4th Army was 609,035 men (period May 20 - December 10, 1917).

- Liked: 32,878

- Missing: 38,083

- Wounded and Others: 165,280

- Total losses: 236,241

Reception and aftermath

July 31, 1917 is the subject of public commemoration and media reflection in Great Britain and other Commonwealth countries, especially on major anniversaries.

As early as 1917 Elsa Laura von Wolhaben published the song In Flandern rides der Tod , which was later appropriated by the National Socialists.

The author Ernst Jünger took part in the battle as a subaltern officer and described his experiences in the book In Stahlgewittern, based on diary entries, first published in 1920 .

Winston Churchill recalled the battle as a “disaster” in 1942 to demonstrate that Lloyd George's later victorious war cabinet had also made serious mistakes.

See also

literature

- Ernst Gruson (Lieutenant Colonel): The 4th Thuringian Infantry Regiment No. 72 in the Battle of Flanders, October 1917. Contributions to the history of the regiment, Association of Officers of the former Royal. 4. Thuringia. Infantry Regiment No. 72 (eV), Torgau 1922.

- Nigel Cave: Passchendaele. The fight for the village (in: Ypres. Battleground Europe ), Cooper, London 1997, ISBN 0-85052-558-6 .

- Martin Marix Evans: Passchendaele and the Battles of Ypres , Osprey Military, London 1997, ISBN 1-85532-734-1 .

- Peter H. Liddle: Passchendaele in Perspective. The Third Battle of Ypres , Cooper, London 1997, ISBN 0-85052-552-7 .

- Nick Lloyd: Passchendaele. A New History. Penguin, 2017, ISBN 978-0-241-97010-2 .

- Lyn Macdonald: They Called It Passchendaele. The story of the Battle of Ypres and of the men who fought in it , Penguin Books, London 1993, ISBN 0-14-016509-6 .

- Keith Perry: With a Poppy and a Prayer. Officers Died at Passchendaele 31st July-10th November 1917 , Naval and Military Press, Uckfield 2003, ISBN 1-84342-499-1 .

- Christopher Staerck: Battlefront. 6th November 1917. The Fall of Passchendaele , Public Record Office, Richmond 1997, ISBN 1-873162-42-1 .

- Hedley Paul Willmott : The First World War , Gerstenberg Verlag, Hildesheim 2004, ISBN 3-8067-2549-7 .

- Paul Wombell: Battle. Passchendaele, 1917. Evidence of war's reality , Traveling Light, London 1981, ISBN 0-906333-11-3 .

- Christian Zentner : Illustrated history of the First World War , Bechtermünz, Eltville am Rhein 1990, ISBN 3-927117-58-7 .

Movie

- Passchendaele - The Field of Honor , Canada 2008, Director: Paul Gross , DVD EAN: 7613059901193, Blu-ray EAN: 7613059401198

Web links

- factbites.com - link collection (English)

- bbc.co.uk - Passchendaele (English)

- firstworldwar.com - The Third Battle of Ypres (English)

- users.globalnet.co.uk (English)

- Historical footage of the battles of Flanders on the European Film Gateway

Individual evidence

- ^ A b John Horne: A Companion to World War I. Wiley, Malden 2010, ISBN 978-1-4051-2386-0 , p. 441; and John Hamilton: Battles of World War I. ABDO, Edina 2004, ISBN 1-57765-913-9 , p. 27; and Norman Leach: Passchendaele. Canada's triumph and tragedy on the fields of Flanders. An illustrated history. Coteau Books, 2008, ISBN 978-1-55050-399-9 , p. 36; and Nicholas Hobbes: Essential militaria. Facts, legends, and curiosities about warfare through the ages. Grove Press, 2004, ISBN 0-8021-1772-4 , p. 98.

- ↑ Lloyd, Passchendale , pp. 79–80, 108.

- ↑ Duff Cooper : Haig. The Second Volume , Faber & Faber, London 1936, p. 154 f.

- ^ Gerhard Donat: Lützow's wild daring crowd. The Mecklenburg Grenadier Regiment 89 in both world wars. Biblio Verlag, Osnabrück 1990, pp. 15-18.

- ^ The untouched German submarine base , In: Vossische Zeitung , January 2, 1918, morning edition, page 3.

- ^ The War Office: Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the Great War 1914-1920, London March, 1922, p. 326 f.

- ^ Medical report on the German army in the world wars 1914/1918, III. Volume, Berlin 1934, p. 53 ff.

- ↑ Numbers quoted from Nick Lloyd: Passchendaele. A New History. Penguin, 2017, p. 302.

- ↑ Hansard

- ↑ Günter Helmes : “The attack has to be continued, no matter what the cost.” A sample of the cinematic staging of the First World War . With references to literary themes. In: "... so the war looks through in all ends". The Hanseatic City of Lübeck in everyday war life 1914–1918, ed. by Nadine Garling and Diana Schweitzer. Lübeck 2016, pp. 219–263.