Trench warfare in World War I

Trench warfare (a predominantly trench warfare ) culminated in World War I. British historian Paul M. Kennedy writes:

“If there is a symbol of the First World War left behind for posterity, then it is trench warfare - there are millions of soldiers, entangled in the mud in a senseless battle for years, only to gain tiny land with enormous losses, a bloodletting for years the population and resources of the warring nations. "

In the fighting off Verdun alone , over 700,000 soldiers were killed or wounded from February to December 1916, but the course of the front was almost unchanged at the end of the battle. The trench warfare was and is still understood as the symbol of the First World War, with the complete war is often erroneously reduced to trench warfare.

execution

With the development of the Minié projectile , which allowed the mass use of rifles with a rifled barrel and a much higher effective range , frontal attacks by both cavalry and infantry units were extremely lossy. The American Civil War had already shown that cavalry attacks on a broad front could be repulsed without major problems. It was also here that the use of trenches was tried out for the first time and proved enormously successful in defense. With the widespread introduction of breech loaders , defenders had an even greater advantage, as they could now fire at the attacker without leaving cover. Machine guns increased the defenders' firepower many times over and were able to mow down the attackers as soon as they got up to advance.

Though thus the nature of warfare had changed dramatically way most armies and generals were not prepared for the impact of these changes. At the beginning of the First World War, all the armies involved prepared for a short war, the tactics of which was to resemble the previous wars. These tactics called for quick, aggressive advances to encircle and destroy enemy units and armies. The execution of these attacks was not fundamentally different from that in the Napoleonic wars: an onslaught of as many men as possible in a small space with bayonets attached, in order to then kill the enemy in close combat.

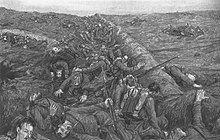

With the outbreak of war, the German and Allied troops realized that even the smallest cover made it possible to repel an attack without any problems. Frontal attacks resulted in unprecedented losses on both sides; therefore both sides dug themselves into increasingly complex trench systems and tried again to overrun the opponent's defense systems with ever larger amounts of artillery and soldiers.

Initially, flank attacks were seen as the only way to win. After the Battle of the Marne, this led to a series of encircling maneuvers that only ended when both armies reached the North Sea coast. The rift system of the western front extended from there to the Swiss border. The trench warfare on the western front continued until the German spring offensive in March 1918.

On the western front, the first temporary trenches were quickly replaced by a complex system of trenches. The area between the trenches was called no man's land . The distance between the trenches varied depending on the front section. In the west the distance was usually 100 to 250 meters. In some places, for example at Vimy , the trenches were only 25 meters apart. After the German withdrawal to the Siegfried Line in spring 1917 ( Alberich company ), the distance increased in some cases to more than one kilometer. At the Battle of Gallipoli , the trenches were only about 15 meters apart, so there were frequent hand grenade fights there.

construction

At the beginning of the war, British defense doctrine envisaged a trench system with three parallel trenches connected by communication trenches. The connection points between the main and communication trenches were usually heavily fortified due to their importance. The foremost trench was usually only heavily occupied in the morning and evening hours, but only slightly during the day. About 60 to 100 meters behind the first trench was the support or "movement" trench (English. Travel). In these the troops withdrew when the first trench was under artillery fire. Another 250 to 500 meters behind the support trench was the reserve trench, in which the reserve troops assembled for a counterattack should one of the front trenches have been taken. However, this division was quickly outdated as the firepower and mass of the artillery continued to increase; however, in some areas the support trench was retained as a diversion to attract enemy artillery fire. Campfires were lit in it to give the impression of an occupied trench, and damage was immediately repaired.

Temporary trenches were also built. When a major offensive was planned, collection trenches were built near the first trench. These trenches served as a protected rallying point for the troops that followed the first wave. The first wave of attack usually attacked from the first trench. Trenches were provisional trenches, often unmanned impasses that in the no man's land were dug. They were used to connect the upstream listening posts with the main trench system or as a preferred line of attack for a surprise attack.

Behind the front system there were usually some partially built trenches in case of retreat. The Germans often used several functionally identical trench systems one behind the other. On the Somme Front in 1916, they used two fully developed trench systems that were one kilometer apart. Another kilometer behind was a partially developed system. These dual systems made a major breakthrough virtually impossible. Should part of the first system be conquered, “alternating trenches” were built to connect the second system of trenches to the part of the first system that was still held.

The German army expanded its positions very massively; Both deep concrete bunkers and fixed positions were built in strategically important places. On the western front, the Germans tended to be more on the defensive and more often willing to withdraw into prepared positions than the Allied armies. They developed the elastic system of defense in depth, in which several entrenchments were built in the front area instead of relying on a single trench. The neighboring hills could be set under fire from every hill. The climax of this doctrine was the Siegfried Line , in which heavily fortified bunkers were connected by a network of trenches, which were only sparsely occupied near the front, in order to lure the enemy into prepared death zones. The British eventually adopted this tactic in part, but were unable to use it fully until the offensive in 1918.

construction

Trenches were never built straight, but always in a sawtooth-like pattern, which divided the trench into bays that were connected by cross trenches. A soldier could never see more than ten meters down the trench. As a result, if part of the trench was occupied by enemies, the entire trench could not be taken under fire. The fragmentation effect of an artillery shell that hit the trench was also limited in this way. The side of the trench, which was facing the enemy was called the parapet ( parapet ). There was also a step on this side that made it possible to look over the edge of the trench. The opposite side was called Parados and protected the soldiers from splinters in case a shell fell behind the trench. The sides were reinforced with sandbags, wooden boards, and wire mesh; the floor was covered with wooden planks under which there was a water drain.

Bunkers in various expansion variants were built behind the support ditch. British bunkers were between 2.5 and 5 meters deep, German bunkers were usually built deeper, at least four meters. Some German bunkers consisted of up to three floors, which were connected by concrete stairs.

In order to enable the soldiers to observe the enemy lines without lifting their heads out of the trench, nicks were built in the parapet. This could simply be a gap between the sandbags, which was sometimes protected with a steel plate ( moat shield). German and English snipers used hard core projectiles to penetrate these shields.

Another option was to use a periscope . The Allied soldiers at Gallipoli developed the periscope rifle, which enabled snipers to shoot at the enemy without exposing themselves to enemy fire.

There were three different methods of digging a trench, the first by digging a large width. This was the most efficient method as it allowed many people to work along the length of the trench. However, the soldiers were standing in the open and were unprotected, so this method could only be carried out in the rear areas of the front or at night. The second option was to widen an existing trench; 1-2 men dug at the head of the trench. The men were protected, but this type of expansion was very slow. The third method was similar to the second, only the roof of the trench was left intact, a tunnel was dug, so to speak, which was then later brought to collapse. British guidelines assumed that 450 men would have to dig six hours at night to dig a 250 meter front trench. Even after that, a trench required continuous maintenance to counteract deterioration from weather and shelling. The folding spades that every soldier carried with them were usually used as tools. On the French side, motorized crawler excavators were also used in the protected area.

The battlefields in Flanders , where some of the fiercest fighting took place, posed particular problems for the trench builders, especially the British, whose positions were mostly in the lowlands. In some areas the water table was only one meter below the surface, so the trenches filled up very quickly. For this reason, some trenches were made of massive sandbag breastworks. Initially, the Parapet and Parados were built in this way, later the back was left open so that the line, if captured, could be better under fire from the reserve line.

Life in the trenches

The time a soldier spent on the direct front line was usually short. It ranged from a day to two weeks before the unit was relieved. The Australian 31st Battalion spent 53 days in a row at the front near Villers-Bretonneux ( Somme department ) on one occasion . But such a duration was a rare exception. The typical year of a soldier could be divided roughly as follows:

- 15% front trench

- 10% support ditch

- 30% reserve trench

- 20% break

- 25% other (hospital, travel, training, etc.)

Even on the front line, there were only relatively few massive combat operations for the typical soldier, so that monotony and boredom were not infrequent on the soldiers' nerves. However, the frequency of fighting for elite units on the Allied side increased.

In some areas of the front there was less fighting, so life on these sections was comparatively easy. When the 1st ANZAC Corps was transferred to the Western Front after the evacuation of Gallipoli , it was transferred to the quiet section south of Armentières for "acclimatization" . Other sectors have been the scene of bloody fighting. So the section near Ypres became hell especially for the British in their protruding front bulge. However, there were numerous losses even on sections that were considered quiet. In the first six months of 1916, before the start of the Somme Offensive , the British did not take part in any major battle; Nevertheless, 107,776 soldiers died during this time.

A front sector was assigned to an army corps , which usually consisted of three divisions . Two of the divisions each occupied a section at the front, while the third division recovered behind the front. This division continued through the division structure. Each division usually consisted of three brigades , two of which were deployed at the front and the third was kept in reserve. This continued for battalions (or German regiments ) up to the companies and platoons . The lower the unit was in the hierarchy, the more frequently the units rotated.

During the day, snipers and artillery watchers made any movement very dangerous, so it was mostly quiet. Work in the trenches was usually carried out at night, when units and supplies could be moved under cover of darkness, the trenches built and maintained and the enemy scouted out. Guards in advanced positions in no man's land listened to every movement in enemy lines to detect an impending attack.

In order to take prisoners, to loot important documents and to make booty, attacks (English trench raids ) were carried out on the opposing trench. In the course of the war, these raids became a fundamental part of the tactics of the British in order to strengthen their own morale and to exercise control over no man's land. However, this was paid for with high losses. Post-war analysis suggested that the military advantages did not justify the cost of these actions.

At the beginning of the war, surprise raids were carried out, often by the Canadians . However, the increased vigilance of the defenders made this type of raid increasingly difficult. In 1916, the raids became very carefully prepared missions that consisted of a combination of artillery and infantry attacks. The raid was initiated by massive fire intended to clear the front trench and destroy the barbed wire obstacles. The fire was then changed to a barrage around the "cleared" section of the front in order to prevent a counterattack on the raid squad.

Daily ration for a German soldier

- 750 g bread or 500 g field rusks or 400 g egg biscuits ;

- 375 g fresh or frozen meat or 200 g canned meat ;

- 1,500 g potatoes or 125 to 250 g vegetables or 60 g dried vegetables or 600 g mixed potatoes and dried vegetables;

- 25 g coffee or 3 g tea ;

- 20 grams of sugar ; 25 grams of salt ;

- 65 g fat, 125 g jam , cheese or spreadable sausage

- spices, optionally 25 g onions , 0.4 g pepper , 0.1 g paprika , 2 g caraway seeds , 0.1 g clove blossom , 0.05 g bay leaves , 0.2 g marjoram or 3 g ground cinnamon ;

- 2 cigars and 2 cigarettes , 1 oz. Pipe tobacco , or 9/10 oz. Stuffing tobacco, or 1/5 oz. snuff

At the discretion of the commanding officer: a glass of brandy (0.08 l), wine (0.2 l) or beer (0.4 l).

From around the end of 1915, however, these quantities only existed in textbooks. The meat ration was gradually reduced during the war and a meat-free day was introduced from June 1916; at the end of this year it was 250 g fresh meat or 150 g canned meat or 200 g fresh meat for support staff. At the same time, the sugar ration was only 17 g. Meat became a scarce commodity towards the end of the war. Even the bread was made with wood shavings and the like. Ä. Offset to stretch it.

German iron ration

The iron ration consisted of:

- 250 g rusks;

- 200 g canned meat or 170 g bacon;

- 150 g canned vegetables;

- 25 g (9/10 oz.) Coffee;

- 25 g (9/10 oz.) Salt

The supply of the people as well as the horses they needed with drinking liquid was a major logistical problem. Smoke and dust also dried out the throats. Theoretically, a soldier was entitled to two liters of liquid a day, which could hardly be implemented in the front lines, since the capacity of the canteens was 0.8 l. It was strictly forbidden - although often not followed - to drink open water that was contaminated with mud, pathogens and corpse poison on the battlefield . In compensation, dew and rainwater were caught .

Die in the trenches

Due to the intensity of the fighting, around 10% of the fighting soldiers died during the war. For comparison: during the Boer War this figure was around 5%, in World War II it was 4.5%. For the British this rate was even higher at 12%. For soldiers in all armies involved, the probability of being wounded during the war was around 56%. However, it must be taken into account that for every soldier at the front, around three soldiers were employed behind the front (artillery, paramedics, supplies, etc.). Therefore, it was very unlikely for a front soldier to survive the war unharmed. Many soldiers were even wounded several times. In particular, the frequent use of fragmentation projectiles led to extremely disfiguring injuries. Serious facial injuries were particularly feared. Soldiers with such a wound were known in Germany as war crushed and faceless .

Medical care at the time of the First World War was comparatively primitive. Life-saving antibiotics did not yet exist, so even relatively minor injuries from infections and gangrene quickly turned out to be fatal. It is known from studies that injuries caused by copper-coated bullets caused fewer deaths from sepsis than injuries caused by bullets that were not covered with copper-containing metals. The German physicians found that 12% of all leg and 23% of all arm wounds were fatal for those affected. The US Army doctors statistically determined that 44% of all injured Americans who developed gangrene died. Half of all head injuries were fatal and only 1% of soldiers shot in the stomach survived.

Nevertheless, advances in prophylaxis , such as B. hand disinfection for medical staff, for a significantly reduced mortality compared to previous conflicts. Techniques such as sterilization of surgical instruments or bandages, vaccinations , local anesthesia or X-ray examinations to better localize bullets also improved the chance of surviving an injury.

Three quarters of all injuries were caused by the fragmentation effect of the artillery shells. The resulting injuries were often more dangerous and terrible than gunshot wounds. Due to the debris from the grenades entering the wound, infections were much more common. As a result, a soldier was three times more likely to die from a splinter wound in the chest than from a gunshot wound. Likewise, the shock wave from the exploding grenade could prove fatal. In addition to the physical injuries, there were also mental disorders. Soldiers who had to endure a long bombardment often suffered a shell shock (" war tremor "), a post-traumatic stress syndrome . Injuries to the eardrum were also common.

As in previous wars, many soldiers fell victim to infectious diseases. The sanitary conditions in the trenches were catastrophic, and the soldiers fell ill with dysentery , typhus and cholera . Many soldiers suffered from parasites and related infections. The damp and cold trenches also favored the so-called trench foot . This was counteracted by laying boardwalks in the trenches, by dividing soldiers into pairs and obliging them to inspect and care for one another, and by improving combat boots. The number of rats increased significantly as a result of not recovered corpses and poor hygiene, including field latrines .

The burial of the dead was often viewed as a luxury that neither side wanted to afford. The corpses remained in no man's land until the fronts shifted. Since identification was then usually no longer possible, metal identification tags were introduced in order to be able to reliably identify those who had fallen. On some battlefields, e.g. B. at Gallipoli, the dead could only be buried after the war. On the former course of the western front, z. B. found during construction work, bodies.

At various times during the war, but mainly at the beginning of the war, official truces were agreed upon to tend the wounded and bury the dead. As a rule, however, any relaxation of the offensive was refused by the respective army command for humanitarian reasons. The troops were therefore ordered to stop the work of the enemy medics. However, these orders were mostly ignored by the soldiers in the field. Therefore, as soon as the fighting subsided, the wounded were rescued by the paramedics and often the wounded were also exchanged.

Weapons in trench warfare

Infantry weapons

The typical infantryman had three weapons at his disposal: rifle , bayonet (knife) and hand grenades . There were also various improvised, misappropriated objects, such as the feldspade or sticks wrapped with barbed wire (trench clubs) and the like.

The British standard rifle Lee Enfield , equipped with a magazine with a capacity of ten rounds, was a robust, very precise and reliable rifle that was well suited for the conditions in the trench. Since it was not an interchangeable magazine (you can take it out, but the British soldiers had no other magazines, only loading frames on the man) and it had to be repeatedly refilled with two five-shot loading frames, it only provided one This was an insignificant advantage in fire fighting. It had a theoretical range of around 1280 m, but a normal soldier only achieved sufficient accuracy at around 180 m. The training of the British soldiers placed more emphasis on a rapid rate of fire than on accurate shooting. At the beginning of the war, the British were able to repel the German troops with massive rifle fire (e.g. at Mons and in the First Battle of Flanders ), but later it was no longer possible to set up the necessary rifle line .

The German standard rifle was the Gewehr 98 (G 98), which was on a par with the Lee Enfield in terms of reliability and ease of maintenance. The only five round magazine had the advantage of being better protected against external influences. The French Mod. 1886/93 was technically completely outdated because of its tubular magazine , which after it was empty, could only be reloaded with individual cartridges, just like the 1907 Lebel Bertier with three-shot magazine. The Russian Mod. 1891 was more precise than the German Gewehr 98, but more difficult to repeat. It had a five-round magazine that could be ammunitioned with loading strips.

Although the standard rifle of the US Army was the Springfield M1903 , the US soldiers in Europe mainly used the M1917 or P17. Both weapons are of excellent quality and precision. The US Army also successfully used the Winchester Model 1897 forearm repeater (better known as "trench gun"), which was particularly effective in trench warfare ( trench broom ). With Brenneke projectiles (slugs) these weapons were only sufficiently precise up to a distance of about 30 meters. The German army command protested against the use of this weapon and threatened the US military in a diplomatic note on September 14, 1918, that every captured soldier who was in possession of this weapon or its ammunition would be shot, as they believed they were against the Hague Land Warfare Act violates. However, there were no actual executions as a result.

The British soldiers were also equipped with a 43 cm long sword bayonet, which was too long and unwieldy to be used effectively in close hand-to-hand combat in the trench. The German S98 / 05 bayonet had the same shortcoming. However, the use of the bayonet in a scuffle was safer than a shot that might have hit a soldier of his own. According to British records, only 0.3% of all injuries were caused by bayonets. Especially at the beginning of the war, many older officers attempted bayonet attacks, in which the soldiers ran in close rifle lines with bayonets attached to the enemy positions. These attacks resulted in high casualties and were ineffective, but reflected the outdated level of training of the officers in the first months of the war.

Many soldiers preferred the short-handled feldspade or a trench dagger to the bayonet. One side of the spade was sharpened for this. The spade was shorter and more manageable and therefore better suited for close combat in the narrow trenches . If captured, soldiers who were picked up with a saw-back bayonet were threatened with immediate killing or severe mistreatment (described, among others, by Erich Maria Remarque and Ernst Jünger ).

The hand grenade became the primary infantry weapon in trench warfare. On both sides, men specialized in throwing hand grenades were first trained per unit. Later these weapons were used by every soldier at the front without further training, as it was impractical to rely on a few "grenade launchers" for larger units. The grenade allowed soldiers to fight the enemy without exposing themselves to fire, and it did not require the precision of a shot. The Germans and Turks were adequately equipped with hand grenades at the beginning of the war, but the British had not used grenades since around 1870 and had none available at the beginning of the war. However, the British soldiers managed to do so by using improvised grenades. At the end of 1915, the Mills grenade was introduced into the British Army , a fragmentation grenade , and 75 million hand grenades of this type were used during the war. The German armies, however, used the high-explosive stick hand grenade 15 , which was better suited for the attack due to its low fragmentation effect. The use of hand grenades was a lot safer than shooting with a rifle and was therefore preferred. In 1916, the German army command was forced to issue instructions to ensure that the soldiers used their rifles again.

Morgenstern , mace and similar cutting weapons were used again especially for night raids . These weapons were widespread in the Middle Ages, but with the advent of firearms they became practically meaningless. In the trench warfare they came into use again because they were effective and silent.

Machine guns

The machine gun is probably the weapon that shaped the image of the First World War the most. The Germans used the machine gun from the beginning. As early as 1904, every regiment was equipped with machine guns. The respective operators were well-trained specialists who also mastered indirect aiming with field mounts and were thus able to provide support fire at great distances. After 1915 the MG 08/15 became known. In Gallipoli and Palestine the Turks provided the infantry units, but the machine guns were manned by Germans. Since the repeating rifles because of their low rate of fire and the machine guns were not suitable for storming trenches because of their weight, the German company Bergmann developed the submachine gun MP 18 , which was used in large numbers towards the end of the war.

The British high command was not convinced by the machine gun at the beginning. Allegedly the British officers rejected it as "unsporting". From 1917, however, every British company was also equipped with four Lewis Guns , which significantly improved their firepower. At the end of 1915, the British set up the Machine Gun Corps and subsequently deployed machine gun companies equipped with the heavy Vickers machine gun at division and corps level .

Heavy (mounted) machine guns were positioned in such a way that they could fire the enemy trenches immediately with overlapping areas of fire or close off artificial gaps in their own obstacles. Infantry attacks then usually collapsed immediately. For this reason, developed both sides of the assault team tactics and developed artillery tactics to this machine-gun targeted off. The latter was one of the reasons for the initially resounding success of the Russian Brusilov offensive of 1916.

Infantry mortar

Infantry mortars (formerly known as mine throwers ) fire projectiles in steep fire over a relatively short distance. They were widespread in trench warfare and were used to shoot at the front enemy trenches or to destroy obstacles. In 1914 the British fired 545 mine projectiles, in 1916 as much as 6.5 million.

From 1915, the British primarily used the Stokes mortar , the predecessor of modern mortars. This lightweight mortar was easy to use and had a high rate of fire. This was achieved by the fact that the propellant charge was firmly attached to the grenade; the projectile was simply dropped into the barrel and ignited as soon as it reached the ignition pin located at the end of the barrel.

The Germans used a number of different mortars. The large charge launchers ( heavy 25 cm mine launchers ) fired a so-called air torpedo with a 90 kg explosive charge over a distance of 900 m. However, the flight of these projectiles was quite slow, so the soldiers were able to try to take cover in good time. Much more common, however, were the lightweight 7.58 cm and medium-sized mine throwers 17 cm .

artillery

Artillery dominated the trench warfare battlefield in much the same way that air support does today. An infantry attack that went beyond the range of its own artillery was rarely successful. In addition to attacking the enemy trenches, the artillery batteries fought with each other to eliminate the enemy artillery pieces or at least to make their work more difficult. Attacks and offensives were often prepared by a massive artillery attack . As a rule, however, this turned out to be less effective, as it warned the enemy of a possible attack and the trenches offered relatively good protection for the soldiers. The technology developed by the German shock troops tactics waived so a long artillery preparation, but led just a short barrage on the narrow space by attack.

On the western front, the German troops often had the advantage of high ground, which they used to remove their batteries from direct enemy observation by positioning their batteries on the far side. In the course of the war, this advantage was offset by new location methods such as sound and light measurement , which were perfected primarily on the British side. In addition, there was the fact that with the availability of reconnaissance planes and observation balloons , the latter of which were also equipped with telephone connections , camouflage usually only lasted for a short time. Therefore, frequent changes of position were carried out.

The artillery primarily fired shrapnel , high explosive or (later in the war) gas grenades . The British experimented with incendiary phosphorus and thermite grenades to set trees and ruins on fire. Furthermore, were light grenades used to illuminate to the battlefield or to give signals.

The German 42-cm mortar " Dicke Bertha " could fire a grenade weighing up to a ton over 10 km.

An important innovation in modern artillery was the hydraulic recoil damping, which meant that it was no longer necessary to realign the gun after each shot. At the beginning of the war, practically all armed forces involved were equipped with such rapid-fire guns.

In the First World War, the artillery of all warring parties together fired around 850 million shells.

gas

Tear gas was first used in August 1914. However, it was not particularly successful, as the enemy was only temporarily incapacitated. In addition, the ammunition was developed for use in closed rooms; in the open air the substance evaporated too quickly. Attempts with ethyl bromoacetate or dianisidine chlorosulfonate were also unsuccessful.

However, the attempts with tear gas paved the way for the use of deadly chemical warfare agents . On April 22, 1915, at the beginning of the Second Battle of Flanders , chlorine gas was used for the first time near Ypres , which was blown out of gas cylinders. A sufficiently large dose was fatal, but the gas was easily recognized by the smell and the sight of the dense, mostly yellowish-green colored gas cloud. The gas caused severe permanent lung damage. Phosgene , first used in December 1915, was much more lethal and not as easy to detect as chlorine gas. In 1916 it was further developed into diphosgene , which u. a. was less susceptible to water.

In order to bring these warfare agents to the enemy, the German gas pioneers first used the Haber's blowing process, with which the chlorine gas (heavier than air and therefore concentrated near the ground) was released from containers against the French trenches when the wind was blowing. However, this was very risky, as the gas was blown into your own ranks when the wind direction changed. The warfare agents were later fired using mortars or artillery shells.

The most effective chemical warfare agent, however, was mustard gas , which was first used by the German side in July 1917 in the course of the artillery duels before the Third Battle of Flanders near Ypres. It was therefore also referred to as "Yperite". The name "mustard gas" comes from the typical smell of the not highly purified substance of mustard or garlic . In its pure form it appears as a colorless and odorless liquid at room temperature; the designation as gas does not apply in the strict sense. Presumably, after chlorine gas was first used , “ poison gas ” was initially adopted indiscriminately for all other warfare agents. Mustard gas was not used in the blowing process, but only fired with a mine thrower or artillery shell during the First World War. It was not as deadly as phosgene, but it persisted on surfaces and had a long-lasting effect. The gas also had an effect on the skin, which made it difficult to protect against the gas.

The exact number of those who were poisoned or killed by chemical warfare agents during the First World War is difficult to determine, especially since the majority of soldiers only died of the long-term effects after the war: estimates assume around 1.2 million wounded and 100,000 dead. The advantage of war gases was seen less in the killing than in the wounding of the enemy. A wounded soldier ties up more forces (doctors, paramedics) than a killed soldier.

In the later course of the war, better training of the soldiers and better and better gas masks made it increasingly impossible to achieve a breakthrough with gas alone. In fact, it quickly became apparent that poison gas was quite "ineffective". Only the very first poison gas attacks were able to actually generate land gains, mainly due to the surprise effect.

On the German side, the different types of warfare agents were designated by names such as blue cross ( nose and throat warfare agents ), green cross (lung warfare agents ), white cross ( eye warfare agents ) and yellow cross ( skin warfare agents ), according to the color coding of the containers or grenades. Towards the end of the war, the so-called colored shooting was adopted . The effect should be maximized through the gradual use of different warfare agents. So-called mask breakers were first used to induce the soldiers on the opposite side to take off their gas masks, then lung warfare agents, which could now work unhindered, etc.

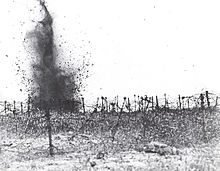

Mines (explosive charges)

Mines were detonated in specially dug tunnels under the enemy positions. The dry soil on the Somme was particularly suitable for this, but tunnels were also dug into the moist soil of Flanders with the help of pumps. Special tunnel units, often consisting of former miners, dug the tunnels under the opposing trenches and fortifications . These tunnels were then filled with large quantities of highly explosive explosives such as ammonal and detonated remotely at a set point in time, which often coincided with the start of an offensive. The resulting large craters served two purposes: on the one hand, they tore holes in the enemy defensive lines and buried numerous defenders under the earth; on the other hand, they served as the “basis” for new trenches. As soon as a mine was detonated, both sides tried to capture and fortify the crater.

If the digging pioneers noticed that the enemy was planning to do the same, attempts were made to enclose or kill him with underground explosions.

The British detonated a number of mines on July 1, 1916, the first day of the Summer Battle . The largest mines were blown up near La Boisselle . Both contained 24 tons of explosives and threw the earth 350 m high. The Lochnagar crater near La Boisselle is still preserved today.

At 3:10 a.m. on June 7, 1917, 19 British mines were detonated at the start of the Battle of Messines , one of the most successful uses of this type of combat. The mines contained an average of 21 t of explosives, the largest under St. Eloi , 42 t. The explosion was reportedly still felt in England. The Chief of Staff of the British 2nd Army, General Sir Charles Harington , wrote on the eve of the battle:

"I don't know if we will change history tomorrow, but in any case we will change the landscape."

The craters of this and many other explosions are still visible today. At least 24 mines were buried near Messines, but not all of them detonated. One was discovered and defused by the Germans, another exploded in a thunderstorm in 1955. At least three are suspected to be underground, one of them directly under a farm.

During the battles between Italy and Austria-Hungary from 1915 in the Alps, massive mines were also used because the positions in the mountains could not be conquered. Whole mountain peaks were blown away. Troops were deployed on both sides to listen in the positions to see whether the enemy was tunneling under the mountain. Blasts were also used to trigger avalanches. The most famous mine explosion in the Alps took place at Col di Lana .

Steel helmets

During the first year of the war, none of the troops involved were equipped with steel helmets. The soldiers mostly wore normal cloth or leather caps that had no protective effect against projectiles and shrapnel. On the German side, the leather pimple hood was used, which had been in use since 1842, served a representative purpose and provided maximum protection against saber blows (hence the “pimple”). As the war turned into trench warfare, the number of fatal head injuries from fragments of grenade and rock rose dramatically.

The French were the first to equip their soldiers with steel helmets in the summer of 1915. The "Adrian" (designed by General Louis-Auguste Adrian) replaced the traditional " Képi ". Before and during the introduction of the French steel helmets, a steel half-shell worn under the kepi was used as an interim solution in order to at least mitigate the effect of splinters. Later this model was adopted by the Belgians, Russians and Italians.

In the summer of 1915, the British engineer John Brodie developed the Mk-I helmet "Brodie" . The helmet had a wide brim to protect the wearer from falling debris, but offered little protection in the neck area. The Brodie helmet was also used by the US troops in a slightly modified form.

The German Pickelhaube was replaced in 1916 by the characteristic steel helmet model 1916 ( M1916 ), which was slightly modified in 1917 and 1918. For example, a bracket for attaching additional armor in the forehead area was added, which should better protect against headshots . Previously, in 1915, the Gaede Army Department in the Vosges had used a steel helmet with a leather hood it had procured itself.

Barbed Wire

Barbed wire and other barriers such as the Spanish Horseman or the "Flanders Fence" were used to slow the advance of enemy troops. So the attacker had to laboriously remove the wire barriers in front of the enemy trenches, during which time he could be well taken under fire. In some cases, gaps were left in that the defender opened or damaged the barbed wire at one point in order to provide an enemy patrol with an allegedly easy path into the obstacle system. In reality, however, the place was secured by one or more machine guns so that approaching enemy soldiers could easily be fired at. Barbed wire turned out to be the most effective "weapon" to stop enemy soldiers alongside the machine gun. Wire barriers were usually put in place at night in order to be safe from observation and to avoid enemy fire with artillery. The artillery bombardments of enemy positions before offensives, which often lasted days, were not least designed to render the barbed wire barn in front of the enemy trenches harmless. However, this goal could only be insufficiently achieved with artillery. It took days and thousands of tons of ammunition to clean a narrow area of barbed wire using grenades. This time, however, could be used by the enemy to prepare for other means and, not least, was economically very ineffective.

The wire was attached to simple wooden posts, metal rods (some of which were set in concrete, especially in the area of fortresses) and round metal rods with two to six eyelets (d = 50 mm) created by bending 360 ° to the longitudinal axis for pulling in the wire. These rods, also known as “pig tails” or “queue de cochon”, were approx. 1.5 to two meters long and provided with a thread at one end so that they could be screwed into the ground silently and suspicious knocking noises when hammering were avoided. The wire then only had to be inserted and not nailed down as with wooden posts or attached to "normal" metal rods. The creation or removal of wire obstacles in advance was one of the most dangerous tasks at the front, as you had to leave the protected trench. Due to a shortage of materials, the Germans developed a barbed wire that was punched from sheet metal and was a forerunner of today's NATO wire .

Step traps

In trench warfare as well as in fortress and house warfare, a large number of simple objects that were only moderately injurious to the attacker were used. These included step traps such as crow's feet , roughly the size of a fist made of two or four approx. 0.5 to 1 cm thick round metal rods, which were connected in a cross shape in the middle and angled. The four ends were ground to a point. In the further course of the war, these were also made from two flat bars approx. 30 cm long welded in the middle and bent at 90 °, which were also ground. Often these were dropped from airplanes.

A variant is a flat chain, the links of which were equipped with one or more thorns. Similar models are still used today by security forces for roadblocks. In the course of the war, a wide variety of similar objects were used, including thorn spikes made of steel, some of which were buried in pitfalls, or slender wooden stakes or spikes. Many of these step traps could be made makeshift in the field. Although the wounds were not directly fatal, they were very often infected under the circumstances. The person concerned was incapacitated, in the case of amputations as a result of infections, completely.

flamethrower

The German armed forces introduced the flamethrower to the troops in 1911 and a new special regiment with twelve companies was set up. The major of the Landwehr pioneers and fireman (fire director in Poznan and Leipzig) Bernhard Reddemann (1870–1938) played a key role in the development of World War I.

The Germans started using flamethrowers in 1915, but the technology was not very advanced and ineffective. The weapon primarily caused terror among the enemy. The tactic was developed by the Sturmabteilung Rohr under Willy Rohr . The flamethrower proved to be effective mainly against fortifications such as the forts around Verdun during the Battle of Verdun . Those attacked in this way had little chance of escaping to safety and, in addition, the combustion reaction deprived the air of oxygen.

The flamethrowers of that time were bulky and heavy devices that were much too cumbersome to use. This meant that a lot of staff was needed to operate a flamethrower. This made the flamethrower squads easy targets and the risk of tanks being hit and exploding made the situation even worse.

The Allies therefore stopped their attempts to develop a flamethrower. The Germans, on the other hand, used the flamethrower in over 300 missions.

Air support

The less robust aircraft at the beginning of the war were mainly used for long- range reconnaissance . But already during this period they fulfilled an important task that the generals underestimated.

When the British arrived in France, they brought just 48 reconnaissance planes with them. Every day they explored the area of the German advance and reported the enemy movements to the high command. It was thanks in particular to them that General Joffre initiated the offensive on the Marne .

Another important task was artillery coordination. Captive balloons were also used for this purpose. The task of the first fighter pilots was to protect their own scouts and shoot down the enemy planes and tethered balloons, or at least keep them from doing their job.

Aircraft were also used directly against enemy positions. Initially, aviator arrows were used to combat enemy troops. These were mostly dropped in large quantities over enemy lines and were quite capable of penetrating steel helmets and killing a person. Despite their clout arrows were not particularly effective because of their low accuracy, so that one later attack aircraft (including the first all-metal aircraft , the one Junkers J , with along flew at low altitude the enemy trench and this) developed machine-gun fire and bombs occupied. The other aircraft technology also made tremendous progress: The machines in the later course were faster, more robust and equipped with machine guns to fight enemy targets.

Single or multi-engine machines were used as bombers . Their main task was to defeat or destroy high-value targets in the hinterland, such as enemy artillery batteries, headquarters, storage facilities, etc. The bombers were usually equipped with defensive armament consisting of machine guns (against enemy fighter planes).

Propaganda, in particular, took advantage of the aerial warfare , as the pilots could be stylized as heroes and knights of the air and thus distracted from the merciless battles in the trenches. Thus, the term was the ace dominated for pilots with more than five confirmed kills.

With the advances in technology and tactics of the air war, the aviators laid the foundation for civil aviation as well as for the development of bombers and close air supporters.

Trench warfare

strategy

The basic strategy of trench warfare is attrition: the opponent's resources should be consumed continuously until he is no longer able to wage war.

In the First World War, however, this did not prevent the ambitious commanders from also following the strategy of annihilation and the ideal of a decisive battle. The British commander General Douglas Haig pursued the goal of a breakthrough which he could exploit with his cavalry divisions. His major offensives - Somme 1916 and Flanders 1917 - were planned as breakthroughs, but developed into battles of wear and tear. The Germans actively pursued the goal of attrition with the attack at Verdun , which aimed to "bleed" the French army. In the great material battles, qualitatively or quantitatively superior material should be used, while largely sparing one's own human resources, in order to inflict the greatest possible damage on the enemy. As a rule, the Allies were far superior in terms of the sheer quantity of artillery pieces and the production capacity for grenades. They were also the only ones who used the tank's new weapon (towards the end of the war) in large numbers. The German side tried primarily to perfect the quality (range, effectiveness) of the weapons.

These strategies required all parties to convert all resources to a state of war ( total war ), which in particular increased the suffering of the civilian population. A wear and tear strategy could easily fail because other states entered the war and the efficiency of a warring party increased, as did when the USA entered the war in 1917.

tactics

The usual image of an infantry attack during World War I consists of a crowd of soldiers charging in a line through the defensive fire towards the enemy trenches. Indeed, this was the standard practice usual at the beginning of the war; however , this tactic was extremely rarely successful . The usual method of attacking was to attack from prepared trenches at night, mostly removing the biggest obstacles in advance.

In 1917, the German general Oskar von Hutier developed an infiltration tactic in which smaller, well-trained and equipped raiding parties attacked weak points in the enemy lines and bypassed strong fortifications. In addition, the attacks should not be initiated, as usual, with extensive barrage , which could have warned the enemy. Stronger infantry units should follow and attack more strongly defended positions. This enabled them to penetrate deep into the enemy territory, but the advance was limited by the lack of communication and the limited supplies of the troops. The tactic was used during the counter-offensive at Cambrai in late 1917 and the German spring offensive of 1918 .

The role of the artillery in an attack was twofold: on the one hand, it was supposed to destroy the enemy defenses and push back the troops; on the other hand, it was supposed to protect the attack from a counterattack with a curtain of grenades ( barrage ). A so-called fire roller was often used - for the first time in the autumn battle in Champagne in 1915 - in which the gunfire was concentrated on a section of terrain that immediately preceded the attacking infantry. According to a previously established scheme, the artillery fired at a wide strip. Then the fire jumped a few meters in the enemy direction, while the infantry - following as closely as possible - advanced into the section previously fired at. The difficulty here, however, was the precise coordination between infantry and artillery. If the infantry fell behind schedule, the fire roller lost its effect - if it was too fast, it would get caught in its own artillery fire.

Capturing a target was only part of a successful battle; to win the battle the target had to be held. In addition to bringing weapons to take the trench, the attacker also had to bring the tools - sandbags, hoes, shovels, and barbed wire - to defend the trench from a counterattack. The Germans placed great emphasis on an immediate counterattack to recapture the lost trenches. This tactic cost many lives when the British decided from 1917 to better plan the attacks and so better able to intercept the expected counterattack.

communication

One of the attackers' greatest difficulties was reliable communication. Wireless communication was still in its infancy and was not yet ready for use. That is why a telephone , semaphore , signal lamp , signal pistol , carrier pigeon , signal dog and signal runner were used. However, none of these methods were reliable. The telephone was the most effective method, but the cables were very vulnerable to artillery fire and were usually cut early in the battle. To compensate for this, the cables were laid in a ladder-like pattern so that several redundant lines were available. Luminous projectiles were used to report success or to launch a previously agreed artillery attack. Being eavesdropped on by the enemy was also a big problem at first.

It was not uncommon for a commanding officer to wait two to three hours for reports on the progress of a battle. This made quick decisions impossible. The outcome of many battles was therefore in the hands of the company and platoon commanders on site.

It was not until 1916, on the battlefield of Verdun, that small portable radio stations were used that could transmit short Morse codes, although there was a risk of frequency overlap with the neighboring divisions, which is why precise regulation and radio discipline were required.

Overcoming the trench warfare and aftermath

The trench warfare arose as a result of the development of the new, infantry-compatible rapid-fire weapons and their mass production. It is therefore often assumed that new technologies put an end to trench warfare, as a rule the tank is mentioned here. Tanks were certainly an important factor, but they were not used in large numbers until late in the war. Because of the small numbers and the inexperience of the generals and soldiers in sensible tank tactics, the first missions were not very successful. The lack of mobility and fighting power of the early tanks also made the mission difficult. The tanks got stuck in the mud or bumps or could still be fought relatively well with flamethrowers , cannons or concentrated machine gun fire . The awkward caterpillar vehicles also quickly lost their horror, which had driven the German soldiers out of the trenches on the first missions.

A massive attack by tanks was carried out for the first time during the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917. However, the breakthrough was not used and the tanks withdrew too early. In this way it was possible to achieve larger gains in terrain, but they were lost again in a German counter-offensive.

After the war, both sides exaggerated the effect of the tank on trench warfare. The German military sought and found a reason for the defeat in them. For the aspiring Allied officers who would have liked to see a large, standalone tank corps (including JFC Fuller and George S. Patton ), highlighting the tank was a way of accomplishing political goals. For the analysts, the tank offered an explanation for developments that could not be adequately explained by other changes in the weapon systems. It was impossible to imagine that any of the other weapons (planes, artillery, gas) or improved communications could have brought about this change.

However, the tank was only a partial explanation for the fact that trench warfare had become obsolete. Many Allied victories of 1917 were achieved with little or no tanks. At the beginning of 1918 the Germans made land gains without having a significant armored force (most of the tanks used were captured vehicles ). The most important lesson, which the German tacticians had learned all too well and which clearly demonstrated this to their allied opponents with the Blitzkrieg in the West in 1940, was tactical rather than technological. Realizing that creating armored divisions would destroy the defensive advantage of infantry, militaries like JFC Fuller, Basil Liddell Hart , Heinz Guderian, and Charles de Gaulle became masterminds of modern warfare on the move . The decisive factor was the interaction of tank units, combat aircraft and infantry and the so-called focus formation on a limited section of the front. The key to breaking the static warfare in the trenches was to achieve the tactical surprise of attacking the enemy line's weak points, bypassing the fortifications, and breaking away from the notion of having a comprehensive plan for every situation to have. Instead, small, autonomous groups of highly trained soldiers were used (the so-called shock troops ), in which superiors, from company officers to troop leaders , could act independently. Often it was thanks to the initiative of simple soldiers that, for example, an enemy fortified position was eliminated and thus the advancement of the attacking troops was made much easier, which on a larger scale could prove to be decisive for the outcome of the battle. With this method, designed by Oskar von Hutier , preparatory area bombardments by the artillery were avoided, as these could not destroy the enemy positions anyway and instead warned the enemy who could prepare for the attack.

The uselessness of trench warfare, however, was not recognized by all armies; so the French built the Maginot Line in the 1930s, which accordingly also proved to be useless in World War II because the German Wehrmacht simply bypassed it.

Even if the Second World War was more mobile than the first, a legacy of trench warfare still remains in today's warfare. That legacy is the massive firepower that was available through a large, now mobile, front line. This development led to destruction that was terrifying compared to that of the wars of the 18th and 19th centuries. In addition, the tactical innovations that made trench warfare superfluous had an immense impact on warfare. Even today, the basis of modern land warfare is a small, quasi-autonomous unit, the so-called fire team , and smooth communication is the key to gaining and maintaining the initiative against the enemy.

Effects on art

The horrors of the trench war left a lasting impression on those directly involved, which they often tried to process through diaries and novels . Most of these novels contained a clear anti-war message , for example Erich Maria Remarque's Nothing New in the West (1928/29) or The Way Back . Other authors drew a rather glorifying picture of the war, for example Ernst Jünger in 1920 with In Stahlgewittern - From the diary of a shock troop leader . Even during the war, Stefan George had written his great poem The War , in which he also expressed his disgust at the war of the trenches:

He himself laughs grimly when false heroic speeches

Of former times who sounded like mush and lumps

saw the brother sink · who lived in the shamefully

troubled earth like bugs.

In his vowel-less poem schtzngrmm (1957), Ernst Jandl himself used the word trench onomatopoeic to depict the noisy events of the trench warfare. Mention may also be the main work of the American-British poet and critic TS Eliot from 1922 ( The Waste Land , Eng. The Waste Land ), which can be understood as a parable of the rated as the sinking of the previous civilization war.

The Dadaism movement that arose during the war can be traced back in part to both the confusing physiological sensory impressions of life at the front and the inability to gain a deeper meaning (in the sense of a meaning ) from what was experienced in this way . The feeling experienced at the front of ultimately being at the mercy of forces that cannot be influenced was for many artists, if they survived the war, a turning point in their work, partly in a productive sense, partly as an expression of deep disillusionment ( Lost Generation ). Styles that emerged later, such as surrealism, were also shaped by the psychological trauma of the World War and had a formative effect on the attitude towards life in the interwar period .

The German painter Otto Dix ( Triptychon The War , his painting Trench Warfare and the main work of the trenches ), the French Fernand Léger , the British Christopher RW Nevinson and John Nash ( Over the Top ) represent a generation of artists who tried to create destruction and horror of the trench warfare in painting.

Trench warfare was also taken up early on in films, for example in 1918 Charlie Chaplin tried to take the war in Gewehr über ( Shoulder Arms ) a little lightly, but without playing it down. The American Remarque film Nothing New in the West from 1930 was an international success and is still considered one of the most impressive anti-war films today .

Even today, the trench warfare is discussed again and again in film and television. The last six episodes of the British comedy television series Black Adder , which satirically depicts central epochs of English history, are set in the trenches of the First World War.

literature

- Tony Ashworth: Trench Warfare: The Live and Let Live System 1914-18 . MacMillan, 2000, ISBN 978-0-330-48068-0 .

- Stephen Bull: World War I Trench Warfare, 1914-16 (= ELITE 78). Osprey Publishing, 2002, ISBN 978-1-84176-197-8 .

- Stephen Bull: World War I Trench Warfare, 1916-18 (= ELITE 84). Osprey Publishing, 2002, ISBN 978-1-84176-198-5 .

- Stephen Bull: Trench: A History of Trench Warfare on the Western Front . Osprey Publishing, 2014, ISBN 978-1-4728-0132-6 .

- Stephen Bull: Trench Warfare . In: War on the Western Front: In the Trenches of World War I. ed. Gary Sheffield, Osprey Publishing, 2008, ISBN 978-1-84603-341-4 , pp. 170-263.

- John Ellis: Eye-Deep in Hell: Trench Warfare in World War I . Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989, ISBN 978-0-8018-3947-4 .

- Antonio Fernandez-Mayoralas: The Trench War on the Western Front, 1914-1918 . Andrea Press, 2010, ISBN 978-84-96658-15-8 .

- Dorothy Hoobler: The Trenches: Fighting on the Western Front in World War I . Putnam Pub Group, 1978, ISBN 978-0-399-20640-5 .

- Christoph Nübel : Perseverance and survival on the western front. Space and body in the First World War . Verlag Ferdinand Schöningh, 2014, ISBN 978-3-506-78083-6 .

- Andrew Robertshaw: Digging the Trenches: The Archeology of the Western Front . Pen & Sword Books, 2008, ISBN 1-84415-671-0 .

- Trevor Yorke: The Trench: Life and Death on the Western Front 1914-1918 . Countryside Books, 2014, ISBN 978-1-84674-317-7 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Paul M. Kennedy : The rise and fall of British naval power . Herford 1978. p. 263.

- ^ Bavarian Army Museum in Ingolstadt

- ↑ Spiez Laboratory : Mustard Gas Factsheet (PDF; 244 kB), accessed on February 4, 2017.

- ↑ Federal Agency for Civic Education , Information Portal War and Peace: Chemical Warfare Agents in Action ( online ), accessed on July 21, 2018.

- ↑ Stefan George : The War [1917]. In: Stefan George: The new realm . Edited by Ute Oelmann. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2001, pp. 21–26, here p. 24.

- ↑ Otto Dix : The War. (Ed. Dietrich Schubert). Marburg 2002. p. 21 ff.