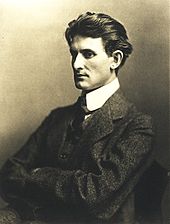

Stefan George

Stefan Anton George (born July 12, 1868 in Büdesheim , today a district of Bingen am Rhein , † December 4, 1933 in Locarno ) was a German poet . First, especially the symbolism committed, he turned after the turn of the century from a mere aestheticism of the above in the leaves for art advocated "art for art" and was the center of the eponymous, based on own aesthetic, philosophical and Lebensreform ideas George Circle .

Life

Childhood and youth

George was born the son of the innkeeper and wine merchant Stephan George and his wife Eva (née Schmitt) in Büdesheim (near Bingen). The family originally came from Roupeldange, which has belonged to France since 1766 . The brother of George's great-grandfather Jacob (1774–1833), Johann Baptist George (grave in Büdesheim), had moved from here to Büdesheim and had (since himself childless) as heir to George's grandfather Anton (1808–1888; soldier under Karl X. ) as well as his brother Etienne (the later politician) brought to him. Stefan George was seen as a closed, solitary child who tended to be high-handed from an early age. From 1882 he attended the Ludwig-Georgs-Gymnasium in Darmstadt . In addition, he learned Italian, Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Danish, Dutch, Polish, English, French and Norwegian on his own in order to be able to read foreign literatures in the original. His talent for languages also prompted him to develop several secret languages . He kept one of them for personal notes until the end of his life; However, since all relevant documents were destroyed after his death, it is lost except for two lines in a poem and these can no longer be deciphered.

During his school days, he wrote his first poems, which appeared from 1887 in the newspaper Rosen und Disteln , founded with friends , and were included in the volume Die Fibel published in 1901 . After graduating from high school in 1888, George traveled to the European cities of London , Paris and Vienna . In Vienna he met Hugo von Hofmannsthal in 1891 . In Paris he met the symbolist Stéphane Mallarmé and his circle of poets, who had a lasting influence on him and allowed him to develop his exclusive and elitist approach to art, l'art pour l'art . His seals should evade any purpose and profanation . One of Georges Paris contacts was Paul Verlaine . Under the influence of the Symbolists, George developed an aversion to realism and naturalism, which were very popular in Germany at the time . From 1889 he studied for three semesters at the Philosophical Faculty of the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Berlin , but soon broke off his studies. After that, he remained without a permanent address throughout his life, living with friends and publishers (such as Georg Bondi in Berlin), even if he initially withdrew relatively often to his parents' house in Bingen. Although he had received a considerable inheritance from his parents, he was always very frugal. As a poet, he identified himself early with Dante (when he also appeared at the Munich Carnival), whose Divina Comedia he translated in parts.

art for art

His early work in particular testifies to the attempt to achieve a lyrical renewal in Germany. In 1892, together with Carl August Klein, he founded the magazine Blätter für die Kunst , which, in the spirit of l'art pour l'art of Baudelaire , Verlaine and Mallarmé , served as an “art for art”. In the following time the poetry volumes Hymnen , Pilgerfahrten , Algabal , The books of the shepherds and prize poems , The Year of the Soul and The Carpet of Life were written , with which George gradually moved away from aestheticism. The “Blätter” appeared in private printing at irregular intervals until 1919 with a total of twelve sets of five booklets of 32 pages each, some of them as double editions. The initial edition was 100 copies, which later increased to 2000. The exclusivity was emphasized on the title page right up to the end: “This magazine published by the publisher has a closed readership, invited by the members.” The first editions were only available in three selected bookshops in Berlin, Vienna and Paris. The members were represented by name in the “Circle of Leaves for Art”.

During this time, George appeared in readings to a select audience. As he read his verses, dressed in a priestly robe, the audience listened, moved. He then received individual listeners for audiences in an adjoining room. His books were unusually designed and initially only existed in intellectual circles. The typeface was particularly noticeable : it was kept in moderate lower case, uppercase only for the beginning of the verse, some proper names and other accents. From 1904, Georges prints appeared in a separate type, the so-called St. G. Font , which was supposedly based on George's own “handwriting”. One feature is the partial use of a short vertical line in the middle called a high point (i.e. a variant of the center point ) instead of the comma .

George's remarks on art soon found growing acceptance in the humanities. This was mainly due to the fact that the staff of the Blätter für die Kunst had an influence on literary studies in the early 20th century. Friedrich Gundolf , who was close to George, held the chair for German studies at Heidelberg University and caused a sensation with monographs on Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and William Shakespeare . Karl Wolfskehl, on the other hand, did significant work in the field of the transmission of Old and Middle High German poetry.

In addition to his writing activity, George was active as a congenial translator who translated and rewrote the respective originals , trying to transfer their meaning and rhythm .

George Circle

From about 1892 like-minded poets gathered around George who felt spiritually connected to him. George's publications were authoritative for the views of the so-called George Circle . At first it was a league of equals that gathered around the papers for art ; among them were Paul Gerardy , Karl Wolfskehl and Ludwig Klages , Karl Gustav Vollmoeller and others. Back then, the union was aligned with George, but the structure remained loose. After 1900 the character of the district changed. With the accession of new and younger members, the relationship with the “master” also changed. George felt himself to be a sculptor and teacher of youth. Mainly Friedrich Gundolf , later also the three Stauffenberg brothers, followed him like disciples.

At first George's close confidante included the Viennese writer Hugo von Hofmannsthal . The relationship had started on the part of George, who was homoerotically drawn to men. His impetuous urge, however, turned the fascination of Hofmannsthal, who was six years older than George on Christmas Eve 1891, into fear. George's obsession went so far that he even asked the 17-year-old to a duel because Hofmannsthal had allegedly misinterpreted his advertising. It didn't come to that, but Hofmannsthal felt so persecuted by George that in his desperation he finally asked his father for help, who was able to stop George's pursuit with a clarifying conversation.

The intellectual relationship between the two lasted for almost 15 years, with George always taking on the role of the decisive older friend. At the same time, Hofmannsthal, despite the high esteem for George's poetic genius, resisted personal appropriation by him and his circle. An intensive correspondence dates from this time. In his conversation about poems (1903), Hofmannsthal presented the famous poem from the year of the soul , with which George introduces this cycle:

- Come to the park that has been declared dead and look:

- The glimmer of smiling shores.

- The pure clouds of unexpected blue

- Illuminates the ponds and the colorful paths.

- There take the deep yellow. The soft gray

- Of birch and beech. The wind is mild.

- The late roses weren't quite fading yet.

- Select kiss her and weave the wreath.

- Don't forget these last asters either.

- The purple around the tendrils of wild vines.

- And what was left of green life

- Twist slightly in the autumn face.

It became more and more clear that the mutual expectations were disappointed and their artistic ideas diverged more and more. So George concentrated on the poetry and demanded allegiance, which Hofmannsthal gradually withdrew, especially since he was also open to drama and other forms. When his tragedy “The Saved Venice” was dedicated to George in 1904, the latter reacted negatively. He certified Hofmannsthal that the attempt to "catch up with the great shape" had failed. In March 1906 they broke off contact completely. The Heidelberg professor Friedrich Gundolf fared even more dramatically, who found himself in such a bondage relationship with him that he did not use his exclusion from the George circle (the reason was his marriage to Elisabeth Salomon in 1926, which the jealous George did not tolerate). In 1927 he fell ill with cancer, from which he died in 1931. Even after his marriage, George punished the Germanist Max Kommerell , the mentor of the young Claus von Stauffenberg in George's “State”, with exclusion and contempt .

The three Stauffenberg brothers, including the later Hitler assassin Claus von Stauffenberg (see meaning below ), had belonged to the Georges district since 1923. Around 1930 he designated Berthold as his successor to Robert Boehringer (see also Stefan George Foundation ).

Become a prophet

From 1907 - George was almost 40 years old - a turning point can be seen in George's concept of art. His works no longer met the demands of so-called self-sufficient art, but increasingly acquired a prophetic and religious character. From then on, George increasingly acted as an aesthetic judge or prosecutor who tried to fight a period of flattening. The main reason for this was George's meeting with 14-year-old Maximilian Kronberger in Munich in 1902. After Kronberger's sudden death in 1904, George put together a memorial book that appeared in 1906 with a preface in which "Maximin" (as George calls him) was elevated to the status of god who "had come into our circles". To what extent this "Maximin cult" was actually a common circle or rather a private Georges, the fact that he had recognized the divinity Maximin, willing to justify its own central position is difficult to reconstruct.

In addition, George's thematic break was due to his private life. At that time he had turned away from the occult circle of Ludwig Klages and Alfred Schuler and broke off contact with Hugo von Hofmannsthal. The loss of some followers and the succession by younger poets caused a change in the sheets for art . The poems, some of which were published anonymously, moved into the metaphysical and increasingly dealt with apocalyptic , expressionistic and esoteric- cosmic topics. The George Circle had also changed as a result. If it was previously an association of like-minded people, it has now turned into a hierarchical league of disciples who rallied around their superior master George. It is believed that there was emotional or even sexual abuse in Stefan George's district.

Important works that emerged on this basis were the volume of poetry The Seventh Ring , published in 1907 , at the center of which is the Maximin cycle . The development reached its climax with the strictly formal volume of poems Der Stern des Bundes , published in 1913 , in which Maximin - "You always start us and end and middle" - was celebrated as the "star" of the "Bund", ie the George Circle .

War rejection and idol of youth

George ignored the general war euphoria. Instead, he predicted a bleak outcome for Germany. This is how he put it in his poem Der Krieg , composed between 1914 and 1916 :

It is not

appropriate to rejoice: there will be no triumph · Only many downfalls without dignity ..

The creator's hand escaped, races unauthorized

Unformed lead and sheet metal · Rod and pipe.

He himself laughs grimly when false heroic speeches That

sounded like pulp and lumps.

He saw the brother sink · who lived in the shamefully

troubled earth like bullies ..

The old god of slaughter is no longer.

Diseased worlds

feverishly come to an end In the frenzy. Only the juices are sacred.

Still poured flawlessly - a whole stream.

The end of the war in 1918 and the general destruction and chaos were confirmation of his visions for George. In the Weimar Republic he became the idol of an idealistic youth. George's admirers among the wide-ranging “Bundische” youth included both nationalist and republican-minded youngsters, youngsters with a Zionist background and anti-Semitic attitudes. One of the George disciples was the young historian Ernst Kantorowicz ("Emperor Friedrich the Second", 1927). Klaus Mann later recalled George's popularity as follows: "In the midst of a rotten and crude civilization proclaimed, he embodied a human-artistic dignity in which discipline and passion, grace and majesty are united." Provide a person with a support that contradicted the nihilism of the time. George himself was skeptical of the republic. In 1927 he was awarded the first Goethe Prize by the city of Frankfurt am Main . George refused, however. From 1921 George spent the summer at Limburgerstrasse 19 in Königstein im Taunus . He was cared for here by his sister Anna, who had previously settled in Königstein in 1918.

"The New Kingdom"

In his late work The New Reich (1928), George proclaimed a hierarchical reform of society based on a new spiritual and spiritual aristocracy. Referring to this volume of poetry, the National Socialists wanted to harness George for their purposes. However, George pursued the realization of an empire on a purely spiritual level and did not want a political realization of a hierarchical and totalitarian system. Because of this, he rejected the National Socialists' requests.

After taking power in 1933, Reich Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels offered him the presidency of a new German Academy for Poetry. George also refused this offer, and he stayed away from the party-side pompous celebration of his 65th birthday. Instead, already seriously ill, he went to Switzerland, where he died on December 4, 1933 in the hospital in Locarno. It is unclear whether he was looking for an exile with this last trip or just planning a temporary stay. George was buried in the Minusio cemetery near Locarno. The brothers Berthold and Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg also attended his funeral .

Importance and Influences

Georges poetry deliberately distinguishes itself from everyday language through its high level of stylistic and formal rigor. Many of his poems are exemplary self-reflective poetry. Drama and prose were considered less valuable literary genres, although drama was well cultivated in his circle (for example by Henry von Heiseler ). The themes of his early work were death, unfulfilled tragic love and attraction to nature. George's goal in his later work was to create a new, beautiful person. The basis should be masculinity, discipline, customs and poetry. Some texts were also used as the basis for musical works, for example by Richard Mondt (1873–1959), Arnold Schönberg (1874–1951), Anton von Webern (1883–1945), Gerhard Frommel (1906–1984), Theo Fischer (1926), Gerhard Fischer-Münster (1952) and Wolfgang Rihm (1952).

In addition to his own poetry and extensive travels across Europe, George was the translator of Dante , Shakespeare's sonnets , Charles Baudelaire The Flowers of Evil - Umschlagungen , Émile Verhaeren and many others.

Thanks to his numerous contacts with well-known German university professors (e.g. Friedrich Gundolf), Stefan George had a great influence on German universities, especially in the humanities.

Maximin myth and cosmician

In the Maximin myth, elements of the Greek and Christian motif of the divine child , which can already be found in the Egyptian Horus myth, are repeated . Before Nietzsche's historical horizon, George believed he would deliver for his circle what the Mallarmé circle had promised and Zarathustra had promised: to create a world before which one could kneel as "last hope and drunkenness."

In this transfigured sense of drunken adoration, George spoke of him in his preface to Maximin as the savior and “actor of an almighty youth” who closed himself off to the circle in difficult times when some ventured into “dark districts” or “full of sorrow or hatred” , returned the trust and fulfilled it with the "bright new promises." "This truly divine" has changed and relativized everything by "the servile present lost its sole right" and calm returned, which let everyone find his center. Outsiders would not understand that the circle had received such a revelation as through Maximin, whose tender and divine verses heralded beyond any valid measure, although he himself had attached “no special importance” to them. His lively voice taught those who were desperate about his death about the folly of their pain and the greater necessity of the "early ascent". Now one can only prostrate before him and pay homage to him, which has prevented human shyness during his lifetime.

In Schuler's anti-Semitic-esoteric world of ideas, “cosmic energies” of man streamed together in the blood , a precious possession that was the “source of all creative powers”. This treasure is permeated by a special luminescent substance that tells of the cosmic power of the wearer, but can only be found in the blood of selected people. General rebirth in the Sun Children or Sun Boys was expected from them in times of decline . Now, according to Klages, there was a mighty enemy of blood, the spirit, and the cosmic efforts should boil down to freeing the soul from the "bondage" of this spirit, that force which with progress and reason, capitalism, civilization and the Judaism was to be equated and would mean the victory of Yahweh over life. Schuler's tirades against “Molochism”, as he called his allusion to the child- devouring Moloch , hardly differed from the anti-Semitic phrases that were being used in Vienna around this time . Klages went beyond this by speaking of the pseudo-life of a larva that Yahweh used "to destroy humanity by means of deception."

Although George rejected many of Schuler's ideas as nonsensical, he was fascinated by him and recalled his conjured visions in several verses. Now Klages, who had grown ever closer to Schuler, wanted to drive a wedge between George and the Jewish member of the Karl Wolfskehl district . In 1904 he embraced the zeitgeist and indirectly confirmed George's rejection of anti-Semitism: Klages claimed that in 1904 he saw through at the last moment that the George Circle was "controlled by a Jewish center". He had given George the choice by asking him what "binds" him to "Judah". George avoided this conversation. Wolfskehl, who characterized himself as "Roman, Jewish, German at the same time" and can be seen as an important representative of the Jewish reception of George, initially believed in a symbiosis of Germanness and Judaism and was guided by the works of the poet, who was written in the star of the Bund in the sense of an elective affinity called Jews as the "misunderstood brothers", "from glowing desert ... home of the ghost of God ... immediately removed."

However, the poet was less concerned with his relationship with Judaism than with art. Ultimately, Maximin can be seen as George's answer to the savior expected by Schuler, the sun boy , but in a sense that contradicts the cosmists' obscure worldview: if Maximin was the unity of “cosmic shiver” and Hellenic amazement, this worked for Klages and Schuler is aiming at the feared victory of the spirit, of light over pleasant darkness.

For George, Maximin was supposed to reconcile the Apollonian and Dionysian principles that Nietzsche had already distinguished in his early work . So he was "one at the same time and different, intoxication and brightness."

Nietzsche's influence

In this context Nietzsche's influence on George is also important, which has been emphasized many times.

George's view of history was based on Nietzsche's monumental history , which Nietzsche had placed alongside the antiquarian and critical ones in the second part of his Untimely Considerations On the Benefits and Disadvantages of History for Life , and whose standard was Plutarch's descriptions of the lives of great people from Greek and Roman antiquity. The past can be interpreted from the highest power of the present: “Satisfy your souls in Plutarch and dare to believe in yourself by believing in his heroes”. So man as “active and striving” hopes for an eternal, over The connection that existed in the times, because what was once able to “expand the concept of human beings further and fulfill them more beautifully”, must “exist forever.” In the sense of this ghostly conversation, the great moments of the individual connect and form a chain like a “bridge over the desert Stream of becoming ”, which connects the mountain range of humanity through millennia. This insight spurred him on to great achievements, because the outstanding things of the past were possible and thus also achievable later.

George's prophetic role in the follow-up to Nietzsche is made clear in the poem of the first part of "The Seventh Ring", which is characterized by the pathos of high responsibility and to which the poet's distance from the "stupid (en)" "trots (end) crowd" in Opposite the lowlands is to be noted as well as its great overview. In visionary perspectives he compares Nietzsche with Christ , "shining before the times / like other leaders with the bloody crown", as "the redeemer who cries out in the 'pain of loneliness.'"

At the latest with the seventh ring , George presented himself in the role of the strict legislator in his own artificial realm. Herbert Cysarz , for example , who met George through Gundolf, reported that the poet had declared himself "the willful founder of an artistic state."

George tried to explain the shameful end of Nietzsche also with his isolation, with the flight into the spiritual heights of “icy rocks” and “horste horrible birds.” So he believes he has to posthumously call out to the great dead man that loneliness is “pleading” offers no solution and it is “necessary” to “ban oneself into the circle that love closes ...”. For the poet himself, this was his own circle of disciples, whom he gathered around himself and in which he set the tone. This went so far that the circle created the myth that George himself was the only legitimate Nietzsche descendant, redeeming the visions of the Praeceptor Germaniae.

Imitatio and homosexuality

George distinguished artists, whom he called primordial or primordial spirits , from derived beings . While the primal spirits were able to complete their systems without guidance, the work of the others was not self-sufficient, so that they were dependent on contact with the primal spirits and could only receive the divine in a derived form. The opposing pair of primordial spirits - derived beings shaped the thinking and work of the George Circle.

For Gundolf , Rudolf Borchardt was regarded as derived, while George himself was "nothing but being". Max Kommerell made a distinction between the original poet, who created new language signs directly from the material of life (mimesis), and the derived poet, who “continued to shape what is formed” (imitatio). Most of George's followers saw themselves as derived beings.

As George explained to Hofmannsthal's critical objections, these derived beings should take part and participate in the creative achievements of the primordial spirits through an ethically and aesthetically specific way of imitation. For George, Karl Wolfskehl and Ludwig Klages were among the few original spirits. The actual creation, the Creatio, does not refer to a new creation of the world, as in French symbolism , but to the language with which the world is described. The poet finds new signs for what is perceived, performing mimesis with which the archetypal being is recognized and represented. The derived beings, on the other hand, can write poetry in the gesture of the primal spirits, but cannot themselves accomplish any creation. Conflicts arise when followers mix up the levels or misperceive works.

Hofmannsthal, whom Gundolf later counted among the derived beings , criticized this imitation model. It seems mendacious, it pretends to be “penetrated, to win over the whole” by using the “new tone”. The mediocre poets George messed with would only want to hide their own mediocrity by imitating the Master. George, for his part, reproached Hofmannsthal for conforming to the crowd, getting involved with many and always avoiding working with him. George's poem The Rejected was related to Hofmannsthal in the circle, while George himself did not allow himself to be committed to this interpretation.

A specific aesthetic experience constituted the George Circle and stood at the beginning of every contact between the later member and George himself. It thus preformed a quasi-religious relationship between master and disciple, a relationship that was to be continued through various imitation techniques of the circle. The impulse for this succession was triggered by an aesthetic first experience with George's poetry, which led to the unconditional recognition of his person and his work, as can be seen in the district's memory books. This is particularly evident in Gundolf, the first from George's circle to take on a younger role.

To understand the meaning of imitation and epigonality , it is important to look at the processing of homoerotic moments. While epigonality was rejected within the circle, a specific imitation was among its basic elements. According to Gunilla Eschenbach, an unsatisfied (heterosexual) love relationship played a role in the Sad Dances of the Year of the Soul , which in the prelude to the carpet is replaced by the homoerotic eros of the angel. At the same time George replaced the negative epigonality with a positive imitation: the angel is the leader of the poet, who in turn gathers disciples around him, a paradigm shift that characterizes the beginning of the work and, in retrospect, refers critically to the epigonal female paradigm in the year of the soul . The non-domesticated female sexuality poses a threat to George: He combines the fulfilled (heterosexual) sexual act with decomposition and decadence, in the figurative sense with epigonality or aestheticism. In Die Fremde, for example, a poem from the carpet of life , the woman sinks into the peat as a demonic witch singing in the moonlight with her “open hair”, leaving a “boy”, “black as night and pale as linen” as a pledge while In the thunderstorms classified as linguistically unsuccessful, the “wrong wife” who “romps in the weather” and “unrestrained rescuers” is finally arrested.

In the seventh ring , George reversed a topos of stereotypical criticism of homosexuality of “feminine behavior” and turned it against the group of aestheticists by reproaching them with “arcadian whispering” and “slight pomp”, an effeminate attitude towards the “male” ethos indeed could not exist. He associated “the feminine” with epigonality and aestheticism that had to be fought.

Resistance and Secret Germany

George's late work Das neue Reich intended to be realized on a purely spiritual level. The poet was critical of the approaching Third Reich . "[He] condemned the riots, was repulsed by the plebeian mass character of the movement, but welcomed the change as such". Kurt Hildebrandt classified the alleged confession that George had described himself as the "ancestor of the new National Socialist movement" as a falsification of the Nazi Ministry of Culture. In fact, George wrote when he turned down the honorary post he had been offered as president of the poetry academy newly founded by the National Socialists: "Although I am the ancestor of every national movement - but how the spirit should get into politics - I cannot tell you."

Many intellectual and cultural-historical effects emanated from George and his circle, not least on protagonists of the German resistance . For Claus von Stauffenberg , the encounter with George was of vital importance.

In 1923 the twin brothers Alexander and Berthold , shortly afterwards Claus, were introduced to the poet and introduced to the circle. In 1924 he wrote to the poet how much his work had shaken and roused him. The letter shows the intellectual development of the young Stauffenberg as well as his willingness to act for secret Germany . He read a lot in the year of the soul , and passages that initially seemed distant and intangible to him "first sounded like that and then with your whole soul" nestled in his senses. “The clearer the living” stands in front of him “and the more vividly the act shows itself, the more distant the sound of one's own words and the rarer the meaning of one's own life”.

Stauffenberg, who belonged to the third generation of the circle, in his early poetry mainly imitated poems from the Seventh Ring , as well as the Shepherd and Prize poems and the year of the soul . So he admonished his brother Alexander with a saying whose style and apodictic instructive tone is based on the four-line tables that form the end of the ring and in which there are different lengths of verse in the iambic meter.

Stauffenberg was later reinforced in his resistance to Adolf Hitler , especially by the poem Der Widerchrist with his warning against the “Prince of the bugger” and recited it several times in the days before the assassination attempt of July 20, 1944 . On the eve of July 20, the conspirators gathered again in Berthold's house in Berlin-Wannsee to take a joint oath, written by Rudolf Fahrner and Berthold Stauffenberg. It says in Georgian tone and style: “We believe in the future of the Germans. In German we know the forces that call him to lead the community of occidental peoples to a more beautiful life. "

Immediately before his nightly shooting in the Bendlerblock, Claus von Stauffenberg is said to have shouted: "Long live the secret Germany ", which can be understood as a reminiscence of George's late poem of the same name "Secret Germany". As Gerhard Schulz notes, the verses about the false prophet can be read like no other poem known to him as a prophecy of the "self-destruction" chosen by the Germans during the time of National Socialism . However, most of the historical research assumes, with the majority of eyewitnesses, that Stauffenberg said "Long live holy Germany".

The Secret Germany , title of a complex poem of the last geschichtsprophetischen cycle and first as a term of Karl Wolfskehl in the Yearbook of the spiritual movement used is a secret and visionary construct. It lies hidden beneath the surface of real Germany and represents a force that, as its undercurrent, remains secret and can only be grasped pictorially. Only the capable can recognize it and make it visible. It is a mystical transfiguration of Germany and the German spirit, which is based on a sentence from Schiller's fragment German Greatness : "Every people has its day in history, but the day of the German is the harvest of all time." Secret Germany can also be understood as a mythical politeia of German intellectual greats of all times, as the idea of a German cultural nation and bearer of the German spirit, and in this way forms the opposite pole to the current state. The New Reich already resides in him, a platonic idea, the content of which is based on the respective interpreters, who usually come from George's environment. Against this background, according to Bernd Johannsen, George cannot be regarded as the ancestor of National Socialism.

reception

The poetry of George and his circle has been criticized many times, even panned out, while the circle for its part did not spare itself with defenses, art-theoretical explanations and polemics and was based on the specific imitation model explained above , which differentiated the original creation of the artist from the processing of derived beings .

Rudolf Borchardt was known for his sometimes polemical pamphlets and had previously been close to the circle himself, but then distanced himself. With its program a creative restoration of German culture from the traditional inventory of western worlds of form he was among the opponents of change, of language decay and anarchy of modes and joined the calls for a conservative revolution of the revered Hofmannsthal, which this in his famous writings speech prepared would have. In 1909 he published the essay Stefan George's Seventh Ring in the yearbook Hesperus , with which he subjected the work to sharp criticism.

After a negative overall assessment at the beginning, he goes on to mostly reject, but also praise individual poems. He vehemently criticizes the gap between poetic ability and fame and asks provocatively whether there is a stronger affirmation of the divine in the world than the fact that the works are nothing compared to faith, reminiscent of a doctrine of salvation. In no literature in the world has it been possible so far that someone with demonic means, albeit “without skills and art”, forced the immoderate soul of a generation into the shape of his inner being, a state in which he himself existed. Not a second time has there been a “classic of a nation” who does not master the laws of language and is not sure of grammar or taste, but which “has imposed this language ... gigantically on a new epoch” and can boast of it. The strange number mysticism also dominates the order in a more naive, artificial-external than artistic-composing way and does not obey any internal plan. Only the fourteen opening poems of time would constitute an adequate unit. Some of the (earlier composed) songs that George lets follow the dream darkness are beautiful, of poignant simplicity, classic outline and an unearthly magic of the guided chant, evidence of a great mastery, a great soul, like the poet has never seen in any other Found beech. This includes the song Im windes-weben , which was also highlighted by Adorno.

George's homosexuality and its significance within the circle also played a role in a number of discussions. In a letter to Hofmiller, Rudolf Alexander Schröder initially called the productions of the George Circle the “poor caricature” of “sterile pre-Affaeliteism”. Against the background of the polemical Borchardt review of the seventh ring , he settled with George's complete works and mixed homophobic and nationalistic ones Sounds. The national shrine of Goethe is polluted: "We would have remained silent if George's latest publication did not touch a shrine whose cleanliness was a matter of the German nation with hands we can no longer call pure." This sanctuary would be tainted by homoeroticism, hinted at in the male pair of friends in Goethe's poem Last Night in Italy , with which George would later open his last cycle, The New Kingdom . Schröder emphasizes this “not very clean object” by referring to Maximin and the Seventh Ring.

Friedrich Gundolf , apologetic admirer and student of George, saw his historical task as the “rebirth of the German language and poetry.” He wrote of the “only two people beyond this entire age ... who discharge themselves in words about their historical occupation to fulfill the renewal: Nietzsche and George. "

The appearance of the angel in the carpet of life is proclamation and not epiphany . Gundolf tried to explain his program of the deification of the body with reference to Plato's Symposium and Phaedrus in his own interpretation, which combines the “German heroic cult” with elements of Platonic love . The “heroic cult of antiquity from Heracles to Caesar” is only a “duller form” of the Platonic doctrine. So far, if every genuine belief is “the deification of man as a matter of course” and only “the physical appearance of a mediator is absurd for a bloodless and soulless sex”, “the real secret of George's belief lies in the deification of a young German man of that time.” That is Maximin "No more and no less than the divinely beautiful human being, perfect to the point of miracle, born in this particular hour ... no superman and no child prodigy, that means breaking through human ranks, but just a god , appearance of human rank." a man falls in love with boys instead of girls ”. belongs “in the realm of natural blood stimuli, not of the spiritual life forces.” However one evaluates it - apologetically as a detour of nature or approvingly as its refinement - this infatuation has as little to do with love as the sexual act.

In his much-quoted introduction to the repositioning of Shakespeare's sonnets, George had not only written about the “adoration of beauty and the glowing urge to perpetuate”, but also explained “the poet's passionate devotion to his friend” with the “world-creating power of cross-sex love”. You have to accept this. It is foolish "to stain with blame as with salvation what one of the greatest earthly people found good."

In his review of Stefan George in 1933 , Walter Benjamin went into a study by Willi August Koch and emphasized the poet's prophetic voice right from the start . Similar to Adorno later, he attested that he had prior knowledge of future catastrophes, which, however, referred less to historical than to moral contexts, the criminal courts that George had predicted for the “sex of the hurryers and gawkers”. As the finisher of decadence poetry, he was at the end of a spiritual movement that began with Baudelaire . With his innate instinct for the night, however, he was only able to prescribe rules remote from life. For him, art is the seventh ring with which the order that yields in the joints should be forged together.

For Benjamin, George's art turned out to be strict and cogent, the "ring" as narrow and precious. However, he had the same order in mind that the "old forces" had striven for with less noble means. Responding to Rudolf Borchardt's criticism of misguided stanzas, Benjamin dealt with specific problems of the style that displace the content or eclipse it. Works in which George's strength has failed are mostly those in which style triumphs, Art Nouveau , in which the bourgeoisie camouflages their own weakness by cosmically rising up, raving in spheres and abusing youth as a word. The mythical figure of the perfecter Maximin is a regressive, idealizing defensive figure. With its “tormented ornament (s)”, Art Nouveau wanted to lead the objective development of forms in technology back into the arts and crafts. As an antagonism , it is an “unconscious attempt at regression” to avoid the upcoming changes.

A look at George's experience of nature is enlightening to recognize the historical workshop in which the poetry was created. For the “farmer's son” nature remained a superior and present power after he had long lived as an urban writer in big cities: “The hand that no longer clenches around the plow clenched in anger against it.” The forces of George's origins and later life seem to be in a constant conflict. For George, nature was "degenerated" to the point of complete divestment. A source of George's poetic power is therefore to be sought in the verses about the angry "great nurse" nature ( Templar ) from the Seventh Ring .

Thomas Mann had dealt with the George School and the Dante cult of the poet in an ironic and critical way, for example in Gladius Dei and Death in Venice .

In his short story, The Prophet , he processed impressions of a reading by the George student Ludwig Derleth , who is portrayed as the character Daniel zur Höhe , whose "visions, prophecies and words of daily orders ... in a style mixture of psaltery and revelation tones" by a disciple be presented. “A feverish and terribly irritated self rose up in lonely megalomania and threatened the world with a torrent of violent words.” Daniel zur Höhe also plays a supporting role in the great contemporary novel Doctor Faustus as a participant in the discussion groups and discursive men's evenings in the apartment of Sixtus Kridwiss . He was often mistaken for Stefan George himself or Karl Wolfskehl.

Thomas Mann praised the Nietzsche poem as “wonderful”, but stated that it was more characteristic of George than Nietzsche himself. One would misunderstand and diminish the cultural significance of Nietzsche if one wished that he was himself a master of German prose "Only" as a poet should have fulfilled. The influence on the intellectual development of Germany is not characterized by works such as the Dionysus dithyrambs or the songs of Prince Vogelfrei , but by the outstanding prose of the master stylist.

For Gottfried Benn , George was “the greatest thwarting and emanating phenomenon that German intellectual history has ever seen.” The opening work Come to the park said to be dead and look from the year of the soul , he praised as “the most beautiful autumn and garden poem of our age.” In In his speech on Stefan George , he describes it as an infinitely delicate landscape poem that has something Japanese, far removed from “decay and evil”, towards “quiet concentration and inner satisfaction”. The magical, idyllic and pure image, which is "tender in the inner attitude as in falling," can also be found in other park poems. While Nietzsche and Holderlin see a lot of destruction, everything is clear and delicate with George. For Benn it is astonishing enough to find the Apollonian clarity in a country from whose poets the inexpressible has easily rushed out, "naked substance, foaming feeling."

George's hometown of Bingen honored the poet from 2014 to 2017 with regular publications of his poems on their homepage. A poem with commentary appeared on the 15th of each month. George should be brought closer to the citizens of Bingen. There is also a Stefan George Museum in Bingen in the historic oat box , which is open three times a week in the afternoons.

Awards

1927: Goethe Prize of the City of Frankfurt am Main

Works

Work editions

- Complete edition of the works. Final version . Georg Bondi, Berlin 1927–1934 (last edition).

- All works in 18 volumes . Published by the Stefan George Foundation . Edited by Georg Peter Landmann and Ute Oelmann. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1981ff. (academic study edition).

- Complete edition of the works [electronic resource], facsimile and full text , Directmedia Publishing , Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-89853-499-5

Volumes of poetry

- The fibula (early poems, published only in 1901)

- Hymns (1890)

- Pilgrimages (1891)

- Algabal (1892) (the name refers to the Roman emperor Elagabal ) ( digitized version and full text in the German text archive )

- The books of shepherds and praises poems of sagas and chants and the hanging gardens (1895)

- The year of the soul (1897) ( digitized and full text in the German text archive ; text of the second edition in the Gutenberg project )

- The carpet of life and the songs of dream and death. With a prelude (1900; text from the Gutenberg project)

- Days and Deeds (1903)

- The Seventh Ring (1907; full-text digitized version )

- Der Stern des Bundes (1914; text from the Gutenberg project)

- Three songs (1921)

- The new empire (1928)

- Poems , Eds. Günter Baumann, Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-15-050044-3

Transfers

- Baudelaire. Flowers of evil. Re-sealing (1901)

- Contemporary poet. Re-seals. 2 volumes (1905)

- Dante. Passages from the Divine Comedy (1909, public edition 1912)

- Shakespeare sonnets. Re-sealing (1909)

Correspondence

- Correspondence between George and Hofmannsthal . Edited by Robert Boehringer, 1938.

- Stefan George / Friedrich Gundolf: Correspondence . Edited by Robert Boehringer with Georg Peter Landmann. Helmut Küpper formerly Georg Bondi, Munich and Düsseldorf 1962.

- Stefan George / Friedrich Wolters: Correspondence 1904–1930 . Edited by Michael Philipp. Castrum Peregrini Presse, Amsterdam 1998 (= Castrum Peregrini 233–235)

- Letters. Melchior Lechter and Stefan George. Edited by Günter Heintz. Hauswedell, Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-7762-0318-8 .

- Correspondence. Stefan George and Ida Coblenz. Edited by Georg Peter Landmann and Elisabeth Höpker-Herberg. Klett-Cotta Stuttgart, 1983, ISBN 3-608-95174-1 .

- Of people and powers. Stefan George - Karl and Hanna Wolfskehl. The correspondence 1892–1933 . Edited by Birgit Wägenbaur and Ute Oelmann on behalf of the Stefan George Foundation. C. H. Beck, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-406-68231-5

literature

A well-stocked, complete bibliography of all literature on George can be found here .

George Circle

- Friedrich Gundolf : George. Berlin 1920, extended edition Berlin 1930.

- Ernst Morwitz : Commentary on the work Stefan Georges . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart, ISBN 978-3-608-98284-8 .

- Friedrich Wolters : Stefan George. German intellectual history since 1890 . Berlin 1930.

Memory literature

- Robert Boehringer : My picture of Stefan George . 2 volumes (picture and text volume), Helmut Küpper formerly Georg Bondi, Düsseldorf / Munich 1951, (2nd edition 1968).

- Edith Landmann : Conversations with Stefan George. Düsseldorf and Munich 1963.

- Sabine Lepsius : Stefan George. Story of a friendship . Stuttgart 1935.

- Ludwig Thormaehlen : Memories of Stefan George . Dr. Ernst Hauswedell & Co Verlag, Hamburg 1962.

Secondary literature

- Heinz Ludwig Arnold (Ed.): Stefan George. text + criticism. Volume 168. Munich 2005, ISBN 3-88377-815-X .

- Achim Aurnhammer et al. (Ed.): Stefan George and his circle. A manual . 3 volumes. De Gruyter, Berlin a. a. 2015, ISBN 978-3-11-044101-7 .

- Bernhard Böschenstein et al. (Ed.): Scientists in the George circle. The world of the poet and the profession of the scientist. De Gruyter, Berlin a. a. 2005, ISBN 978-3-11-018304-7

- Maik Bozza: Genealogy of the beginning. Stefan Georges poetological self-design around 1890. Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2016, ISBN 978-3-8353-1933-2 .

- Wolfgang Braungart : Aesthetic Catholicism. Stefan George's Rituals of Literature. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1997, ISBN 3-484-63015-9 , (Communicatio, Volume 15).

- Stefan Breuer : Aesthetic Fundamentalism. Stefan George and German anti-modernism. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1995, ISBN 3-534-12676-9 .

- Wolfgang Braungart, Ute Oelmann, Bernhard Böschenstein (eds.): Stefan George: Work and effect since the 'Seventh Ring' . Niemeyer, Tübingen 2001, ISBN 3-484-10834-7 .

- Jürgen Egyptien: Stefan George: Poet and Prophet , Darmstadt: Theiss, [2018], ISBN 978-3-8062-3653-8 .

- Gunilla Eschenbach: Imitatio in the George circle. De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-11-025446-4 .

- Ulrich K. Goldsmith : Stefan George: A study of his early work. University of Colorado Press (University of Colorado Studies Series in Language and Literature 7), Boulder 1959.

- Ulrich K. Goldsmith: Stefan George. Columbia University Press (Essays on Modern Writers), New York 1970.

- Stefan George Bibliography 1976–1997. With addenda up to 1976. Based on the holdings of the Stefan George Archive in the Württemberg State Library, edited. by Lore Frank and Sabine Ribbeck. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2000, ISBN 3-484-10823-1 .

- Günter Heintz: Stefan George. Studies on its artistic impact. Writings on literary and intellectual history. Vol. 2. Hauswedell, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-7762-0249-1 .

- Corrado Hoorweg : "Stefan George and Maximin" - Translated from the Dutch by Jattie Enklaar Verlag Königshausen & Neumann GmbH, Würzburg 2018 ISBN 978-3-8260-6556-9

- Thomas Karlauf : Stefan George. The discovery of the charism. Blessing, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-89667-151-6 ( FAZ.net review , review Tagesspiegel , spiegel.de )

- Kai Kauffmann: Stefan George. A biography . Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2014, ISBN 978-3-8353-1389-7 .

- Marita Keilson-Lauritz : From love, friendship means ...? Relevance and expressive strategies of homoeroticism in the work of Stefan Georges. Doctoral script Duitse Letterkunde. Amsterdam 1986 [Dissertation in German. Manuscript print 138 pages]

- Karlhans Kluncker: "The secret Germany". About Stefan George and his circle. Treatises on art, music and literature. Vol. 355. Bouvier, Bonn 1985, ISBN 3-416-01858-3 .

- Rainer Kolk: literary group formation. Using the example of the George Circle 1890–1945. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1998, ISBN 3-484-63017-5 .

- Werner Kraft : Stefan George . Ed .: Jörg Drews. Munich: edition text + kritik 1980. ISBN 3-88377-065-5 .

- Robert E. Norton: Secret Germany. Stefan George and his Circle. Cornell University Press, Ithaca / London 2002, ISBN 0-8014-3354-1 .

- Maximilian Nutz: Values and valuations in the George circle. On the sociology of literary criticism (= treatises on art, music and literary studies. Vol. 199). Bouvier, Bonn 1976, ISBN 3-416-01217-8 (also: Munich, dissertation, 1974).

- Ernst Osterkamp : Poetry of the Empty Center. Stefan Georges New Reich (= Edition Akzente ). Carl Hanser, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-446-23500-7 . ( Table of contents , table of contents ).

- Wolfgang Osthoff : Stefan George and “Les deux musiques” Sounding poetry set to music in harmony and conflict. Steiner, Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 3-515-05238-0 .

- Michael Petrow: The poet as a leader? About Stefan George's effect in the “Third Reich”. Tectum-Verlag, Marburg 1995, ISBN 3-929019-69-8 .

- Bruno Pieger, Bertram Schefold (eds.): Stefan George. Poetry - leadership - state. Thoughts for a secret European Germany. Verlag für Berlin-Brandenburg, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-86650-634-3 .

- Ulrich Raulff : Circle without a master. Stefan George's afterlife. CH Beck, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-59225-6 .

- Manfred Riedel: Secret Germany. Stefan George and the Stauffenberg brothers. Böhlau, Cologne a. a. 2006, ISBN 3-412-07706-2

- Martin Roos: Stefan George's rhetoric of self-staging. Grupello, Düsseldorf 2000, ISBN 3-933749-39-5 .

- Armin Schäfer: The intensity of the form. Stefan Georges poetry. Böhlau, Cologne a. a. 2005, ISBN 3-412-19005-5 .

- Franz Schonauer: Stefan George. With testimonials and photo documents. Rowohlt's monographs. Vol. 44. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2000, (10th edition), ISBN 3-499-50044-2 .

- Werner Strodthoff: Stefan George. Criticism of civilization and escapism. Studies on Modern Literature. (= Studies on Modern Literature. Vol. 1). Bouvier, Bonn 1976, ISBN 3-416-01281-X (At the same time: Bonn, Universität, Dissertation, 1975).

- Bodo Würffel: Willingness to work and prophecy. Studies on the work and impact of Stefan Georges. (= Treatises on art, music and literary studies. Vol. 249). Bouvier, Bonn 1978, ISBN 3-416-01384-0 (partly also: Göttingen, dissertation, 1975/76).

- Mario Zanucchi: Transfer and Modification - The French Symbolists in German-Language Poetry of the Modern Age (1890–1923) . De Gruyter, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-11-042012-8 .

Movies

- Stefan George. Secret Germany . Documentary, Germany, 2018, 48:44 min., Script and direction: Ralf Rättig, production: 3sat , ZDF , first broadcast: July 7, 2018 on 3sat, summary by 3sat, ( memento from July 11, 2018 in the Internet Archive ). by 3sat. Stefan George on his 150th birthday.

- The strange case of stefan george. [ sic! ] Documentary, Germany, 2018, 29:44 min., Script and director: Alexander Wasner, production: SWR , series: Known in the country , first broadcast: July 7, 2018 on SWR TV , summary by SWR, ( Memento from September 27 2007 in the web archive archive.today ). from SWR.

Web links

Databases

- Literature by and about Stefan George in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Stefan George in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Stefan George in the press kit of the 20th century of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Works by Stefan George at Zeno.org .

- Works by Stefan George in the Gutenberg-DE project

- George Archive in the Württemberg State Library in Stuttgart

- Stefan George bibliography online

- Annotated link collection of the university library of the FU Berlin ( Memento from October 11, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (Ulrich Goerdten)

various

- Stefan-George-Society Bingen

- Castrvm Peregrini - Where friendship has culture. With access to the Stefan George Research Library, the latest press review, discussion list, etc.

- On the typography of the »George font (s)«

- Poems on zgedichte.de

Biographies

- Stefan George in the literature portal Bavaria

- Lutz Walther, Manfred Wichmann: Stefan George. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Paul Gerhard Klussmann: Stefan Anton George. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 6, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1964, ISBN 3-428-00187-7 , pp. 236-241 ( digitized version ).

- Biography and works of Stefan George. In: sternenfall.de , April 23, 2005.

- Short bio and list of works. In: Bibliotheca Augustana

- Entry about Stefan George ( memento from June 19, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ) on Literature in Context , a multilingual project of the University of Vienna (in German , archived from the original ).

- Entry on Stefan George in the Rhineland-Palatinate personal database

- George, Stefan. Hessian biography. (As of December 29, 2019). In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

Essays and Articles

- A literary sensation - The Secret of Stefan George. In: FAZ , August 3, 2007, by Frank Schirrmacher

- An enigmatic violence. Then as now, the poet Stefan George fascinates George in a mysterious way. In: 3sat , Kulturzeit , with 3 videos, October 5, 2007

- Pederasty from the mind of Stefan George? In: FAZ , April 5, 2010, Thomas Karlauf in an interview with Julia Encke .

Remarks

- ↑ The spelling "St.-G-Schrift" - there is also the spelling "St G Schrift" - is not an abbreviation, but in this form the proper name of the script.

Individual evidence

- ^ Ernst Robert Curtius: Critical essays on European literature . FISCHER Digital, 2016, ISBN 978-3-10-561104-3 ( google.de [accessed on July 14, 2020]).

- ↑ Hessian biography: Advanced search: LAGIS Hessen. Retrieved July 14, 2020 .

- ↑ Stefan George (1868-1933). Retrieved July 14, 2020 .

- ↑ Roland Borgards, Almuth Hammer, Christiane Holm: Calendar of small innovations: 50 beginnings of a modern age between 1755 and 1856: for Günter Oesterle . Königshausen & Neumann, 2006, ISBN 978-3-8260-3364-3 ( google.de [accessed on July 14, 2020]).

- ^ "July Revolution in Paris against the insurgents" - Google search. Retrieved July 14, 2020 .

- ^ Ernst Robert Curtius: Critical essays on European literature . FISCHER Digital, 2016, ISBN 978-3-10-561104-3 ( google.de [accessed on July 14, 2020]).

- ↑ Hessian biography: Advanced search: LAGIS Hessen. Retrieved July 14, 2020 .

- ^ Thomas Karlauf: Stefan George. Munich 2007, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Stephan Kurz: "George Writings". In: Institute for Textual Criticism . January 18, 2007, accessed August 3, 2007 .

- ↑ Quoted from: Stefan George: The year of the soul. Leaves for Art, Berlin 1897, p. [1]. In: German Text Archive , accessed on June 13, 2013

- ↑ Stefan George: Preface to Maximin. In: Ders .: Complete edition of works , digital library, p. 1917.

- ↑ Julia Encke : The end of the secret Germany. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , May 14, 2018, only the beginning of the article free.

- ↑ Stefan George: The War [1917]. In: Stefan George: The new realm. Edited by Ute Oelmann. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2001 (= Complete Works in 18 Volumes, Volume IX), pp. 21–26, here p. 24.

- ↑ Johann Thun: The Bund and the Bunds. Stefan George and the German youth movement . In: Thorsten Carstensen, Marcel Schmidt (ed.): The literature of life reform . Transcript, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-8376-3334-4 , pp. 87-105 .

- ↑ George's biography in: androphile.org

- ^ Manfred Riedel, Secret Germany, Stefan George and the Stauffenberg Brothers , Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2006, p. 150.

- ^ Stefan George, preface to Maximin. In: Stefan George: Works, edition in two volumes, Volume I, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1984, p. 522.

- ^ Stefan George, preface to Maximin. In: Stefan George: Works, edition in two volumes, Volume I, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1984, p. 525.

- ^ Stefan George, preface to Maximin. In: Stefan George: Works, edition in two volumes. Volume I, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1984, p. 528.

- ↑ Thomas Karlauf, blood light. In: Stefan George, The Discovery of Charisma. Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 327.

- ↑ Quoted from Thomas Karlauf: Blood light. In: Stefan George, The Discovery of Charisma. Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 328.

- ↑ Thomas Karlauf: blood light. In: Stefan George, The Discovery of Charisma. Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 332.

- ↑ Thomas Karlauf: Notes, Stefan George, The discovery of charisma. Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 699.

- ↑ Thomas Karlauf: Blood light, Stefan George, The discovery of charisma. Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 331.

- ↑ Thomas Sparr, Karl Wolfskehl: Lexicon of German-Jewish Literature. Metzler, Stuttgart 2000, p. 629.

- ↑ Stefan George: The Star of the Bund. Edition in two volumes, Klett-Cotta, Volume I, Stuttgart 1984, p. 365.

- ↑ Quoted from Thomas Karlauf: Blood light. In: Stefan George, The Discovery of Charisma. Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 333.

- ↑ For example Bruno Hillebrand: Nietzsche. How the poets saw him. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2000, p. 51.

- ↑ Thomas Karlauf, The beautiful life , in: Stefan George: The discovery of the charisma. Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 275.

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche: On the benefits and disadvantages of history for life, untimely considerations. Works in three volumes, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1997, p. 251.

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche: From the benefits and disadvantages of history for life. Outdated considerations, works in three volumes, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1997, p. 220.

- ↑ Stefan George: The seventh ring, Nietzsche. In: Werke, edition in two volumes, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1984, p. 231.

- ^ Bruno Hillebrand: Nietzsche Handbook, Life - Work - Effect. Literature and Poetry, Stefan George. Metzler, Stuttgart, Weimar 2000, ed. Henning Ottmann , p. 452.

- ^ Bruno Hillebrand: Nietzsche manual, life - work - effect, literature and poetry, Stefan George. Metzler, Stuttgart, Weimar 2000, ed. Henning Ottmann, p. 453.

- ↑ Quoted from: Gunilla Eschenbach, Imitatio outside the circle, De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, p. 195.

- ↑ Gunilla Eschenbach: Imitatio in the George circle. De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, p. 3.

- ↑ Quoted from: Gunilla Eschenbach: Imitatio im George-Kreis. De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, p. 5.

- ↑ Gunilla Eschenbach: Imitatio in the George circle. Part 4, Critique of Poetry and Poetics, De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, p. 244.

- ↑ Gunilla Eschenbach: Imitatio in the George circle. De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, p. 12.

- ↑ Gunilla Eschenbach: Imitatio in the George circle. Part 3, Imitatio outside the circle, De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, p. 194.

- ↑ Gunilla Eschenbach: Imitatio in the George circle. Part 3, Imitatio outside the circle, De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, p. 195.

- ↑ Michael Landmann, quoted in Robert E. Norton: Why George today? Frankfurter Rundschau , July 5, 2010.

- ↑ Cf. the text of the condolence telegram sent by the Nazi government to George's sister on December 4, 1933, printed in: Margarete Klein: Stefan George as heroic poet of our time. Heidelberg 1938, p. 100.

- ^ Martin A. Siemoneit: Political interpretations of Stefan George's poetry. 1978, p. 61.

- ↑ Manfred Riedel: Secret Germany, Stefan George and the Stauffenberg brothers. Böhlau, Cologne 2006, p. 174.

- ↑ Quoted from: Manfred Riedel: Secret Germany, Stefan George and the Stauffenberg brothers. Böhlau, Cologne 2006, p. 176.

- ↑ Gunilla Eschenbach : Imitatio in the George circle. De Gruyter, Berlin 2011; Part 2: Imitatio in a circle: Vallentin, Gundolf, Stauffenberg, Morwitz, Kommerell , p. 103.

- ↑ Gerhard Schulz : The antichrist. In: From Arno Holz to Rainer Maria Rilke, 1000 German poems and their interpretations , edited by Marcel Reich-Ranicki . Insel, Frankfurt 1994, p. 83.

- ↑ Joachim Fest : Coup. The long way to July 20th. Siedler, Berlin 1994, Chapter 8: “Vorabend”, p. 144.

- ↑ Quotation in: Herbert Ammon : From George's spirit to Stauffenberg's act. In: Iablis , 2007 (online).

- ^ Peter Hoffmann : Resistance - Coup - Assassination. The fight of the opposition against Hitler. 2nd, expanded and revised edition, Munich 1970, p. 603 and p. 861 f. (In the endnotes a page of justification that according to the testimony of the witnesses to the shooting, this version is correct).

- ↑ Bernd Johannsen: Reich of the Spirit, Stefan George and the Secret Germany. Stefan George as the fulfillment of the imperial myth. Dr. Hut, Munich 2008, p. 201.

- ↑ Bernd Johannsen, Reich of the Spirit, Stefan George and the Secret Germany , Dr. Hut, Munich 2008, p. 1.

- ↑ To this: Gunilla Eschenbach: Imitatio in the George circle. De Gruyter, Berlin 2011.

- ^ Rudolf Borchardt: Stefan Georges Seventh Ring. In: Rudolf Borchardt: Collected works in individual volumes, prose I. Ed .: Marie Luise Borchardt. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1992, p. 259.

- ^ Rudolf Borchardt: Stefan Georges Seventh Ring. In Rudolf Borchardt, Collected Works in Individual Volumes, Prose I, Ed. Marie Luise Borchardt, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1992, p. 263.

- ↑ Gunilla Eschenbach: Imitatio in the George circle. Critique of poetry and poetry, De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, p. 260.

- ↑ Gunilla Eschenbach: Imitatio in the George circle. Critique of lyric and poetics, De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, p. 261.

- ^ Friedrich Gundolf, George, Age and Task , Second Edition, Georg Bondi Verlag , Berlin 1921, p. 1.

- ^ Friedrich Gundolf: George, Age and Task. Second edition, Georg Bondi Verlag, Berlin 1921, p. 2.

- ^ Friedrich Gundolf: George, The Seventh Ring, Second Edition, Georg Bondi Verlag, Berlin 1921, p. 204.

- ^ Friedrich Gundolf: George, The seventh ring. Second edition, Georg Bondi Verlag, Berlin 1921, p. 205.

- ^ Friedrich Gundolf, George, The Seventh Ring , Second Edition, Georg Bondi Verlag, Berlin 1921, p. 212.

- ^ Friedrich Gundolf: George, The seventh ring. Second edition, Georg Bondi Verlag , Berlin 1921, p. 202.

- ^ Stefan George: Shakespeare Sonnette, Umdichtung, Introduction. In: Werke, edition in two volumes, Volume II, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1984, p. 149.

- ↑ Walter Benjamin, looking back at Stefan George , on a new study of the poet, in: Deutsche Literaturkritik, Vom Third Reich bis zur Gegenwart (1933–1968 ), Ed. Hans Mayer , Fischer, Frankfurt 1983, p. 62.

- ^ Walter Benjamin, retrospect on Stefan George , on a new study of the poet, in: Deutsche Literaturkritik, Vom Third Reich bis zur Gegenwart (1933–1968) , Ed. Hans Mayer, Fischer, Frankfurt 1983, p. 63.

- ↑ Walter Benjamin, retrospect on Stefan George , on a new study of the poet, in: Deutsche Literaturkritik, Vom Third Reich bis zur Gegenwart (1933–1968) , Ed. Hans Mayer, Fischer, Frankfurt 1983, p. 666.

- ↑ cf. for example Hans Rudolf Vaget , in: The death in Venice , short stories, Thomas-Mann-Handbuch, Fischer, Frankfurt a. M. 2005, p. 589.

- ↑ Thomas Mann, With the Prophet. In: Collected Works in Thirteen Volumes, Volume VIII, Stories. Fischer, Frankfurt 1974, p. 368.

- ↑ Klaus Harpprecht , Thomas Mann, Eine Biographie , Chapter 97, In the Shadow of Disease , Rowohlt, Reinbek 1995, p. 1550.

- ↑ Thomas Mann, Einkehr , in: Collected works in thirteen volumes, Volume XII, speeches and essays. Fischer, Frankfurt 1974, p. 86.

- ↑ Gottfried Benn, Speech to Stefan George (1934), in: Gottfried Benn, Gesammelte Werke , Vol. 1, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1997 (9th edition), p. 466.

- ↑ Gottfried Benn, Problems of Poetry , in: Essays and Essays, Collected Works , Ed. Dieter Wellershoff , Zweiausendeins, Frankfurt, 2003, p. 1072.

- ↑ a b Gottfried Benn, Speech to Stefan George , in: Essays and Aufzüge, Gesammelte Werke , Ed. Dieter Wellershoff, Zweiausendeins, Frankfurt, 2003, p. 1035.

- ↑ Press release: With Georges “Juli-Schwermut” into late summer. ( Memento from August 19, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) In: Stadt Bingen , August 15, 2014.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | George, Stefan |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | George, Stefan Anton (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German poet and writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 12, 1868 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Büdesheim , today a district of Bingen am Rhein |

| DATE OF DEATH | 4th December 1933 |

| Place of death | Minusio at Locarno |