The benefits and disadvantages of history for life

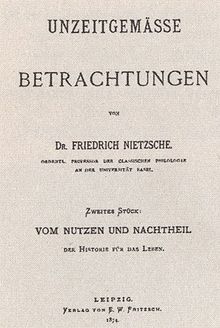

On the benefits and disadvantages of history for life (full original title: Untimely reflections. Second piece: On the benefits and disadvantages of history for life. ) Is a work by Friedrich Nietzsche published in 1874 and the second of his four Untimely reflections . The treatise is considered an important work from Nietzsche's early creative period (see overview of Nietzsche's work ). In it he criticizes his academic contemporaries who, in his opinion, either overestimate or underestimate the importance of historical science . The work also anticipates later topics of Nietzsche and has received comparatively great attention in the Nietzsche reception.

The usual codes of the book in Nietzsche research today are HL or UB II.

Overview

Nietzsche's untimely considerations are primarily culturally critical writings and are not as broad thematically as Nietzsche's later, consistently philosophical works. But he approaches the topic from different angles. So when he deals with the possibilities of the science of history, he touches the topics of philosophy of history and philosophy of science . On the other hand, by relating history to (human) life, he is also practicing a kind of anthropology . Scripture moves within these four areas.

Several interpreters have pointed out that Nietzsche's concept of “history” in particular is not clearly used in the scriptures, but rather between the meanings “history” (res gestae, what actually happened) and “historiography” (historia rerum gestarum, the narrative of what happened) and "historical science" fluctuates. This must be taken into account when using Nietzsche's terminology in the following.

After an introduction in which Nietzsche shares his personal motivation for writing the script, the first chapter examines the origin of the “history”. The animal lives only in the present - with modest luck - and thus unhistorical. In contrast, humans now have the ability to remember. This enables him to create culture. On the other hand, the individual memories and collective records always represent a burden. If these become too big, then the viability of a person or people is inhibited. In Nietzsche's eyes, history is therefore both a necessity and a danger.

The second and third chapters deal with three functions that history has. The monumental history drives people to great deeds, the antiquarian one preserves their collective identity, and the critical one removes harmful memories. However, all three functions could become pathological, which is why they would have to be in balance with one another. Nietzsche's categorization is probably the best-known content of the text, it has been taken up and interpreted in many ways.

In chapters 4–8, Nietzsche describes how an over-saturation with history can have an adverse effect on life and culture. Nietzsche's attacks are always aimed at his contemporaries, especially in Germany, but also claim a general philosophical background. He diagnoses five “diseases” of the present that are supposed to have been caused by the wrong use of history: firstly, a disturbed identity of the Germans, secondly, a lack of sense of justice, thirdly, a lack of maturity, fourthly, self-contemplation as epigones and fifthly, a pathological cynicism. The ninth chapter also belongs thematically to the criticism of Nietzsche's present. It contains an account of the then successful work Philosophy of the Unconscious by Eduard von Hartmann .

In the tenth chapter, Nietzsche finally presents the means to cure what he believes is a sick present: The powers of the unhistorical and “superhistorical” - he calls art and religion - must be promoted in order to ultimately lead to “true education” instead of one-sided, scientific “ Literacy ” .

Central themes

Life and history

Nietzsche contrasts life and history in his work and assumes that history or the pursuit of history can both benefit and harm life. Although he pays more attention to the dangers of history than to its benefits, he does not ask for a decision between life and history, but strives for a kind of synthesis or balance between conflicting forces.

"The fact that life needs the service of history must be understood as clearly as the sentence that will later have to be proven - that an excess of history harms the living."

Nietzsche characterizes life as initially "unhistorical". So the animal and also the human child live unhistorically. Brief moments of happiness that people can experience are also moments of unhistorical feeling. - On the other hand, Nietzsche approaches history through remembering which is peculiar to man. Through them the way to a simple happiness in the way of animals is blocked.

"[The animals are] closely tied to their lust and displeasure, namely to the peg of the moment and therefore neither melancholy nor weary. It is hard for man to see this, because he prides himself on his humanity before the animal and yet looks jealously after his happiness - for he wants that alone, like animals neither weary nor in pain, and yet wants it in vain because he it does not want like the animal. "

Nietzsche attributes a "plastic power" to individual people, but also to peoples and cultures , which among other things consists in "transforming and incorporating the past and the foreign" (Chapter 1, p. 251). Nietzsche sees health, strength and fertility of all living things as the basis of this power. It determines how much history a type of life can withstand: the moment when memory has become a burden for people, they also lose touch with life. This calls into question its vitality. Accordingly, people have to make use of history as much as their culture needs to live. However, history must never become an end in itself that hinders life.

In these fundamental considerations of Nietzsche, connections to Schopenhauer (see influence of Schopenhauer ) and other works of Nietzsche (see classification of the writing ) can be found.

The different types of history

Nietzsche recognizes memory - and thus history in the broadest sense - in all human individuals and collectives. However, he differentiates between different types of history and assigns them to certain character traits and / or types of people to whom they “belong”. He first differentiates between two central types of history: monumental and antiquarian history. These form a kind of antagonism , as they have an opposite effect on people, but both are required by them. Both functions are essential for a stable identity and viability of the individual as well as the collective. However, if one of the two predominates, it appears pathological. Then only a third type, the critical history, can provide a remedy.

According to Nietzsche, each of these three types is justified under certain conditions, but only if it actually serves life in its respective function (see below). "[T] he critic without need, the antiquarian without piety, the connoisseur of the great without the ability of the great" (Chapter 2, p. 264f.) Are people who do not pursue these types of history in their useful function and thus themselves harm yourself and others. Elsewhere (ibid., P. 262; Chapter 4, p. 271) Nietzsche mentions a tension between these three types of history, with one always prevailing at the expense of the other. But since an excess of each of the three types has a harmful effect, a balanced ratio is required.

Modern history, the attempt to practice history as a science, is separate from these three ways of looking at history . If Nietzsche regards the three types of history described above as useful in principle, as long as they are in a harmonious relationship to one another and serve life, he vigorously opposes the "requirement that history should be science" (Chapter 4, p . 271).

The "modern [...] literacy" with its historical knowledge has nothing to do with a "true education" (ibid., P. 275). But this is lacking. Nietzsche assumes his time - the Europe of the late 19th century - and the Germans in particular, that they have a disturbed relationship to the past. He tries to attach this to various “diseases” that he believes he discovered in modern culture (although this term was first coined after Nietzsche).

Monumental history

According to Nietzsche, monumental history belongs to man as “doing and striving” (Chapter 2, p. 258). It encourages the individual of the present to creative deeds: Individuals who want to create great things, but are not sure whether this is even feasible, can turn their gaze to the past. If you discover that great things have already been possible, this is an indication that it will be possible again in the future. This knowledge gives strength and takes away the self-doubt, which stands in the way of creative deeds. With regard to causality , the monumental history places the “effects” (ibid., P. 261) in the foreground and neglects the causes. In addition, this type of history renounces full truthfulness. By reducing the historical processes, it becomes possible to draw analogies between special - temporally spaced - events and processes. In this way the great individuals of humanity would be connected to one another.

One danger of monumental history is to get close to fiction and mythology . If the monumental type of history prevails, large parts of the past are misunderstood; and it stimulates “the courageous to boldness, the enthusiastic to fanaticism” (ibid., p. 262), only to increase the number of “effects” . In addition, the strong people then only identify with other individuals from the past, but they do not value their own culture and people. Nietzsche adds that weak people abuse monumental history: They would use it to prevent today's great people from creating by saying: “See, the great is already here” and thus “the dead bury the living” (ibid ., P. 264).

The dangers of believed epigony, irony and cynicism, which are dealt with in Chapters 8 and 9, are similar to those mentioned. According to Nietzsche, people are taught that they are just epigones of a larger past. With the doctrine of the compelling “world process” (Chapter 8, p. 308), Hegel and his successors gave rise to a fatalistic view: modern man believes that he is at the end of a development. This philosophy of history, promoted by mediocre people, is only directed towards the past, since the supposed conclusion of history has been reached with the present. This means that modern people have lost any will to shape the future.

"Truly, paralyzing and disgruntled is the belief to be a latecomer of the times: it must appear terrible and destructive, however, if such a belief one day with a cheeky inversion adores this latecomer as the true meaning and purpose of everything that happened earlier, if its knowing Misery is equated with the completion of world history. [...] so that for Hegel the climax and the end of the world process coincided in his own Berlin existence. "

According to Nietzsche, modern man unconsciously feels that he is on the wrong track and is no longer able to shape a future. Therefore, he now takes refuge in cynicism : The present is already perfect and a future is no longer needed. The weakness of the “later ones” is thus “turned inside out” into an apparent strength. Nietzsche alludes to Hartmann's philosophy of the unconscious . The central message of this work, which he claims to be a parody , seems to him to be the modern man's invitation to himself to continue living uncritically and thus to automatically participate in the unstoppable "world process" that is striving for salvation . According to Nietzsche, this reinforces the belief in being a late-born man who no longer has anything to accomplish because he has already finished learning and is overripe.

"[T] he historically educated [...] has nothing to do but continue to live as he has lived, to continue to love what he has loved, to hate what he has hated and to read the newspapers that he has read, for him it is only there A sin - to live differently than he lived. "

Antiquarian history

According to Nietzsche, antiquarian history belongs to the human being as “preserving and adoring” (Chapter 2, p. 258). It serves to set human collectives of the present - peoples, cities, genders - in a continuity with their past. It spreads a “simple, touching feeling of pleasure and satisfaction” (Chapter 3, p. 266) by “linking the less fortunate genders and populations to their homeland and homeland custom” (ibid., P. 266). So it gives a person or a people “the luck not to know that they are completely arbitrary and accidental and […] to be excused in their existence, even to be justified” (ibid., P. 266f.).

But antiquarian history also has a downside: since everything seems to be interwoven, if there is an excess of antiquarian considerations, the entire past is viewed as valuable. Everything that has passed is considered great just because it once existed. A leveling takes place, since everything that is truly special between the apparently important mass of history is no longer visible. The antiquarian history threatens on the one hand to degenerate into a "blind collecting mania" (ibid., P. 268), on the other hand to undermine everything new, only to "preserve" instead of "create" (ibid.). Great minds can therefore always be inhibited by pointing out that everything necessary can already be found in the past.

Nietzsche believes he can spot this phenomenon in his presence. He diagnosed modern people, and especially Germans, with a disrupted identity that was caused by a “contrast between form and content”. The equilibrium between the three types of history has been destroyed, since the science of the present incessantly absorbs vast amounts of superficial knowledge. However, this is not really processed, but quickly accepted and rejected again, since humans are only able to absorb a certain amount of foreign and incoherent things. This creates scientific specialists who, in Nietzsche's eyes, have become subject-blind. They are only "walking encyclopaedias" (ibid., P. 274), which are less and less able to grasp the outer world and therefore withdraw to the inner world. Since they no longer apply their knowledge to reality, this ultimately becomes pure content that no longer has any external form. Conversely, however, the scientists could no longer check its interior, so that it becomes chaotic over time and dissolves due to a lack of structure. Modern people are thus robbed of their vitality and culture.

“You probably say that you have the content and that the only thing missing is the form; but with all living things this is an entirely inappropriate contrast. Our modern education is therefore nothing living, because without this contrast it cannot be understood at all, which means: it is not a real education at all, but only a kind of knowledge about education, it remains in it with the educational thought the educational feeling, it will not turn into an educational decision. "

As a counterexample, Nietzsche cites the ancient Greeks , who would have kept the balance between history and life, between knowledge and encased art. He does not require that the culture of a people is aesthetic as long as it is original. For example, simply copying the Greek way of life would be useless and even harmful, since it would suppress its own cultural characteristics. In Nietzsche's eyes, the Germans now have no independent external form, but just randomly adopt foreign conventions. This, in turn, has led to its interior, its intellectual content, being insubstantial. Modern education and philosophy are now only an "internally withheld knowledge without action" (ibid., P. 282). Therefore, people of the present can only criticize, but not create anything of their own.

“In such a world of enforced external uniformity, [philosophy] remains the learned monologue of the lonely strollers, the accidental hunted prey of the individual, hidden room secrets or harmless chatter between academic seniors and children. [...] All modern philosophizing is political and police, limited by governments, churches, academies, customs and cowardice of the people to the learned appearance: it remains with sighing “if it does” or with the knowledge “once upon a time.” Philosophy is without right within historical education, if it wants to be more than an internally withheld knowledge without action […] Yes, one thinks, writes, prints, speaks, teaches philosophically - so far, about anything is allowed, only in action, in what is called Life is different: only one thing is allowed and everything else is simply impossible: that's how historical education wants it. Are they still people, you ask yourself, or maybe just thinking, typing and speaking machines? "

Critical history

Ultimately, critical history belongs to man as “those who suffer and are in need of liberation” (Chapter 2, p. 258). According to Nietzsche, it checks the memories of a people for content that is too stressful, which could hinder their development, and removes them if necessary. In a sense, it serves as a corrective to the other two historical functions. Its only criterion is whether or not a past serves a people's vitality. Nietzsche is thinking of the two pathologies of monumental and antiquarian history, i.e. on the one hand a blind desire for effects and on the other hand an excessive fixation with the past. The viability of human communities is to be preserved through critical history by forgetting harmful memories.

Again, however, critical history is not safe for humans. Ultimately, according to Nietzsche, there is nothing worthwhile to exist: and “ going to one's roots with the knife” (Chapter 3, p. 270) is always a dangerous process, because “we are now looking at the results of earlier genders” (ibid. ) and thus also “of their aberrations, passions and errors, even crimes” (ibid.). There must always be “a limit in denial” (ibid.) So that life is not endangered.

Nietzsche also sharply separates the healthy form of critical history from the scientific view of history, as is customary in his presence. He denies this any ability to pursue critical history in the service of life. The historian would have to rise to the judge of history. To do this, however, he lacks the “drive and the strength for justice” (chap. 6, p. 286). Modern people equate justice with objectivity and understand this in turn as "being detached from personal interest" (chap. 6, p. 290). Nietzsche, on the other hand, understands “objectivity” as the ability of an artist to create an artistically true painting that is therefore not yet historically true. The desire for neutrality is based on pure illusion. Already in the belief that history is a meaningful whole and follows laws that the historian has to recognize, Nietzsche recognizes a subjective and egocentric assumption. The people of the modern age are not made to judge: In Nietzsche's eyes they only measure the past against the “commonplace opinions of the moment” (chap. 6, p. 289).

“Who forces you to judge? And then - just test yourself to see if you could be just if you wanted to! As a judge you should be higher than the one to be judged; while you just came later. The guests who come to the table last should rightly get the last seats: and you want to have the first? Now then at least do the highest and greatest; maybe they'll really make room for you, even if you come last. "

He regards true justice as the main virtue of the historian . However, this can only be achieved by a person who seeks to understand the past in order to build their own future on it. It cannot be the task of history for Nietzsche to find general laws. He quotes one of these from Ranke , whom he only calls a “famous historical virtuoso” (ibid., P. 291) - incidentally, the only place where Nietzsche actually refers to a representative of historicism . Nietzsche considers such “laws” to be “ artificially suspended between tautology and absurdity” (ibid.). Rather, it must be the task of the historian to "describe a common theme, an everyday melody in a witty way, to elevate it to a comprehensive symbol and thus to suggest a whole world of profundity , power and beauty in the original theme " ( ibid., p. 292). This includes artistic ability.

“But so often objectivity is just a phrase. Instead of that internally flashing, externally unmoved and dark calmness of the artist's eye, there is the affectation of calm; how the lack of pathos and moral strength usually disguises itself as the cutting coldness of contemplation. "

Artistic redesign of the history

Nietzsche countered the diagnosed illness with two “remedies”. On the one hand, the correct relationship between the three types of history must be restored; on the other hand, the existing form of historiography is to be transformed: history is to be combined with art, as is the case, for example, in historical drama.

The Germans do not have their own culture because historical education prevents this. This “emergency truth” (Chapter 10, p. 328) must be recognized, and in this sense “our first generation” (ibid.) Should be educated so that it can be unleashed from the constraints of history. Nietzsche says against Hartmann:

“What the 'world' is there for, what 'humanity' is there for, shouldn't bother us at all for the time being, unless we want to make a joke: because the presumptuousness of the little human worms is the most joking and cheerful of all the earth stage; But why you are there individually, ask yourself, and if no one can tell you, just try once to justify the meaning of your existence a posteriori, as it were, by giving yourself a purpose, a goal, an 'addition' put in front, a high and noble 'additional'. Only perish on it - I know no better purpose in life than to perish on the great and impossible, animae magnae prodigus. "

He puts his hopes in the youth. History should not be an end in itself, but should be in the service of life. This requires a different kind of education than the previous one. The focus should not be on history, but rather young people should make their own experiences with life, learn from contemporary creators and be inspired by selected greats. Nietzsche's antidotes to "historical disease" are the "unhistorical" and the "superhistorical":

“With the word 'the unhistorical' I denote the art and power of being able to forget and to lock oneself into a limited horizon ; 'Superhistorical' is what I call the powers that divert the gaze from becoming, towards that which gives existence the character of the eternal and synonymous, to art and religion. "

However, Nietzsche assumes that the scientific present is by all means preventing human maturity. According to this, history destroys the “pious illusionary mood” (Chapter 7, p. 296) that underlies everything sublime (love, religion, art). As an example, he cites Christianity , which has been dissolved into an insubstantial “knowledge of Christianity” (ibid., P. 297) through excessive “historical […] securing exercises” . But the present demands the apparent total knowledge to which young people would be exposed before their time. This dulls them and can neither get excited about the old nor create new ones.

“Yes, one triumphs that now 'science begins to rule over life': it is possible that one can achieve that; But a life ruled in this way is certainly not worth much, because it is much less life and guarantees much less life for the future than the life formerly governed not by knowledge but by instincts and powerful delusions. […] The young person is whipped through the millennia: Young men who understand nothing about a war, a diplomatic action, a trade policy are found worthy of an introduction to political history. But just as young people walk through history, so do we moderns walk through the art chambers, so we listen to concerts. You feel good, that sounds different from that, that works differently from that: to lose this feeling of alienation more and more, to be overly astonished about nothing, finally to put up with everything - that is probably called the historical sense, the historical education . "

This development is due to the modern understanding of science and the associated scholarship, which does not want harmonious and mature personalities, but subjects of the academic job market. By dividing the work within the sciences, the perspectives of future scholars would be so limited that specialists would emerge who could only grasp a narrow part of reality. The "utilization" and finally the "popularization" of science only leads to "solid mediocrity" (ibid., P. 301), harms life and thus indirectly even science itself.

“The last and natural result is the generally popular 'popularization' […] of science, that is, the notorious tailoring of the skirt of science to the body of the 'mixed public': […] for good reasons [this] falls to the younger generation It is easy for scholars because they themselves, apart from a very small area of knowledge, are a very mixed public and carry its needs within them. You only need to sit down comfortably once, so you will be able to open up your small area of study to that mixed-popular curiosity of needs. For this act of comfort one pretends afterwards the name 'modest condescension of the scholar to his people': while basically the scholar only descends to himself, insofar as he is not a scholar but a mob. "

Only in large individuals - he cites Goethe and Raffael as examples from the past - does Nietzsche see the will to counteract this development and to create something new and great. They had not yet learned to arch their backs and bow their heads in front of the Hegelian "'power of history", but would shape their own future.

"Fortunately, [history] also preserves the memory of the great fighters against history, that is, against the blind power of the real, and thereby pillories itself by singling out those who stand out as the actual historical natures who are who cared little about the 'so it is', rather to follow a 'this is how it should be' with cheerful pride. Not to bury their sex, but to found a new sex - that drives them ceaselessly onwards: and if they are born late themselves - there is a way of life that makes this forget; - They will only know the coming generations as first fruits. "

The artistic transformation of history should ultimately serve to give the German people their own culture. Perhaps “it did not include more than a hundred productive people who were educated and active in a new spirit”, as “the culture of the Renaissance stood out on the shoulders of such a crowd of hundred men” (Chapter 2, pp. 260f.). The political unification of the empire of 1871 meant nothing to Nietzsche, as it was only superficial to him. Nietzsche sees the real characteristic of a culture in the “unity of the artistic style in all manifestations of life of a people” (Chapter 4, p. 274), and he hopes for a cultural unification of the Germans with the creation of an original art and education, which the historical Able to overcome illness.

“[T] he origin of historical education - and its inwardly completely radical contradiction to the spirit of a 'new time', of a 'modern consciousness' - this origin must itself be recognized historically, history must be the problem of history itself dissolve, knowledge has to turn its sting on itself - this threefold must is the imperative of the spirit of the 'new time' if there is really something new, powerful, promising and original in it. "

Origin and classification in Nietzsche's writings

Origin, publication and later revisions

After the first untimely appeared in the summer of 1873, Nietzsche was initially still employed at the university. In addition, his commitment to Wagner kept him in suspense. Nietzsche had planned a whole series of out of date considerations anyway , and the publisher EW Fritzsch was also interested in a sequel. Thoughts under the title Philosophy in Distress were actually planned as the topic of the next untimely ones . In autumn, however, after a few notes on scholarship, the science of history came to the fore as a new topic.

Preliminary work on the font can be found in the estate booklets U II 1, U II 2 and U II 3 as well as Mp XIII 2 (in the KGW and KSA ( lit .: Colli / Montinari) as records summer-autumn 1873 (29) and autumn 1873 respectively -Winter 1873/74 (30)). Nietzsche took some passages almost verbatim from the first of the Five Preface to five unwritten books written for Cosima Wagner (December 1872) and from his notes on philosophy in the tragic age of the Greeks (spring 1873). Nietzsche had already made critical remarks on modern education similar to those in Scripture in his lectures on the future of our educational establishments , given in Basel in early 1872 .

At the time of writing he read Goethe , who is also often quoted in the scriptures, next to Schiller (correspondence with Goethe and What is called and at what end do you study universal history? ), Franz Grillparzer and parts of Hegel's lectures on the philosophy of history. The beginning of the first chapter is inspired by Giacomo Leopardi . Eduard von Hartmann's philosophy of the unconscious, which Nietzsche sharply criticized here, he had already acquired in 1869 and read in part with approval. Thoughts from Jacob Burckhardt's lectures and from On the Christianity of Our Modern Theology of his friend and colleague Franz Overbeck also flowed into the Second Untimely . See in more detail: Influences .

It could be interesting for the understanding of the script that Nietzsche initially assumed two opposites: historical - non-historical and classical - antiquarian. It was only during the drafting he triggered the unhistorical the About Historic out. The contrast between classic and antiquarian became, with minor shifts in emphasis, the contrast between monumental and antiquarian. Not until shortly before going to press did Nietzsche add the critical history . In addition, if the “disease” was originally related primarily to an excess of “antiquarian history” , now the criticized historical science has been separated from the three types of history (monumental, antiquarian, critical). Remnants of the original approach are still present in the book.

From December 1873 onwards, Nietzsche, who was ill with the eyes, dictated most of the manuscript to his friend Carl von Gersdorff. Together with Erwin Rohde , Nietzsche read the proof sheets in January; the printed book appeared around February 20, 1874.

The typeface sold worse than the first out-of- date, which with its attack on David Friedrich Strauss on the one hand aroused some interest as a scandal book, on the other hand had isolated Nietzsche. The only significant contemporary review of the second Untimely comes from Karl Hillebrand . The Neue Freie Presse only printed this review with an editorial note, according to which it did so out of respect for Hillebrand: Nietzsche had made himself impossible with his book against Strauss.

By October 1874 about 220 copies were sold, by 1886 there were about 650 copies. As with the other untimely ones, there is only one version of the benefits and disadvantages of history for life , since Nietzsche did not want to reissue it in 1886/87. However, a personal copy with Nietzsche's reworkings has been preserved, which Montinari dated to the year 1886. The modifications are almost exclusively of a stylistic nature.

Position of writing in Nietzsche's work

Nietzsche's later statements on this work are sparse , even in comparison with the other untimely ones . A comment on this can be found in the preface to the second volume of Menschliches, Allzumenschliches , written in 1886 . It says here:

“[And] nd what I said about the 'historical illness', I said as someone who slowly and painstakingly learned to recover from it and was not at all willing to forego 'history' in the future because he once had she had suffered. "

In his stylized autobiography Ecce homo , too , Nietzsche treats the script only briefly, while he discusses the other three untimely ones in detail:

“The second untimely (1874) brings to light the dangerous, the life-gnawing and poisoning in our type of scientific business - life sick with this dehumanized wheelwork and mechanism, with the 'impersonality ' of the worker, with the false economy of 'division of labor'. The purpose is lost, the culture: - the means, the modern scientific enterprise, barbarized ... In this treatise the 'historical sense', of which this century is proud, was recognized for the first time as an illness, as a typical sign of decay. "

Jörg Salaquarda (see lit. ) saw Nietzsche's later disregard and shortening of the work on the points mentioned as being due to the fact that he was dissatisfied with the style and structure of the hastily drafted script. Nietzsche's memory of it was also very negatively colored, since at the time of writing the alienation from Wagner was stronger, Nietzsche's illnesses were worse and the dissatisfaction with the Basel professorship was greater. Finally, several examples can be found in Nietzsche of having "forgotten" parts of his writings. According to Salaquarda, research ultimately did more justice to this work than Nietzsche himself.

The author's disregard for the script is all the more astonishing as some central ideas from Nietzsche's oeuvre are at least considered in this early script:

- Art and science: He exercises a biting criticism of science, which considers itself to be “objective” and therefore “just” , which he accuses of ignorance and weakness, which is taken up again in the fifth book of the cheerful science and the late writings. At the same time he calls for an artistic transformation of the sciences, as he himself later wanted to practice literarily.

- Dionysian and Apollonian: When Nietzsche writes of life as an uninhibited, creative but blind force, this can be combined with his characterization of the “Dionysian” in the birth of tragedy . Analogously, history could be assigned to the “Apollonian”, also representative of all science. Corresponding pairs of opposites such as forgetting-remembering or dark-light can be found in scripture. Nietzsche himself suggested a connection to the birth of tragedy , albeit somewhat indistinctly (see below).

- Morality and strength: Nietzsche links the use of different types of history to the strength or weakness of the individual. Already here he relates strength and moral-aesthetic views. However, he did this fully only in On the Genealogy of Morals . In general, some interpreters consider the genealogy of morals, especially the second treatise it contains, to be important for understanding Nietzsche's philosophy of history and its development.

- Übermensch : Nietzsche calls for a new generation relatively vaguely, which should represent a synthesis of the unhistorical but vital animal or barbarian and the culturally active, historical but weak human being. This must develop a supra-historical awareness that can "organize the chaos in itself" . In this, as in the young Nietzsche's concept of genius in general, some saw the higher man, the superman or the “lords of the earth” from So Spoke Zarathustra prepared.

On the other hand, there are passages in later works in which Nietzsche seems to fundamentally contradict the theses presented here. The entire “genealogical” method that Nietzsche pursued since his free-spirited phase is entirely based on history. In the second aphorism of Menschliches, Allzumenschliches (1878) it says:

"Lack of historical meaning is the hereditary fault of all philosophers [...] Accordingly, historical philosophizing is necessary from now on, and with it the virtue of humility."

Finally, the view can be taken that Nietzsche's demand for an artistic transformation of history is a subsequent justification of the methodology of The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music (for content-related sewing see above). This had dispensed with philological evidence and sources and instead used Nietzsche's intuitively gained knowledge about the origin of the tragedy. Nietzsche himself indicates a connection in the preface to the second volume of Menschliches, Allzumenschliches :

"In this respect, all of my writings [...] have to be dated back [...]: some, like the first three Untimely Considerations, even go back behind the time of origin and experience of a previously published book (the 'birth of tragedy' in the given case: how it must not remain hidden from a finer observer and comparator). "

The question of how the benefits and disadvantages of history for life can be classified in Nietzsche's entire oeuvre has also preoccupied the reception of writing and found different answers there.

Influences and similarities to other philosophies

For the background, especially the emergence of modern history in Europe in the 19th century, see first the history of history .

Nietzsche based his consideration of history on the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer and the cultural history of Jacob Burckhardt, among other things . However, one cannot speak of a pure adaptation of these thinkers.

Schopenhauer

For the young Nietzsche, Schopenhauer was a guiding star of possible German culture. Schopenhauer had spoken out in detail “About history” in Chapter 38 of the second volume of Die Welt as will and idea . He had argued that history can be a knowledge, but never a science, because it is only "coordination" of what is known, but science is "subordination". History has a certain knowledge of the superficial, the general (such as "the time periods, the succession of kings, the revolutions, wars and times of peace"), but what is essential and interesting in it is the individual and the individuals, which cannot be grasped in general . History as the course of phenomena is determined by coincidences, there is no "system of history". In particular, Schopenhauer sharply rejected the teachings of Hegel and his successors. A real philosophy, however, recognizes that history always shows the same thing under changing veils, namely the unreasonable, blind “ will ”.

Nietzsche took the turn against a teleological view of history. At the same time this means denying a predetermined meaning of history. The passages on Nietzsche's “ aberrations, passions and errors, yes crimes ”, which determine history, correspond most closely to Schopenhauer's ideas.

But traces of Schopenhauer's teachings can also be seen in the foundations of the script, Nietzsche's conception of the eponymous “life” . With Nietzsche, too, life appears as a kind of blind will, in contrast to the Hegelian emphasis on " spirit ". The "plastic power" that Nietzsche attributes to all living things is similar to Schopenhauer's will, but "sometimes has a strange positive connotation" ( lit .: Sommer). Nietzsche did not follow Schopenhauer's pessimism without reservation : instead of hoping for a liberation from the “world will” , Nietzsche was possibly aiming for a synthesis of vital but blind will and cold knowledge. The means that Schopenhauer and Nietzsche see in achieving their respective goals are, however, identical: the escape into art and music.

Burckhardt

Jacob Burckhardt, his colleague at the University of Basel , also had an impact on Nietzsche's view of history. In the winter semester of 1870, Nietzsche heard his college "On the Study of History", which was later published as part of World History . Burckhardt's first lecture on “Greek Cultural History” in the summer semester of 1872 was also followed by Nietzsche. He also owned an edition of Renaissance Culture in Italy, from which the brief Burckhardt quote in The Benefits and Disadvantages of History for Life comes.

Nietzsche was inspired by Burckhardt in his negative interpretation of the political present: the Basel cultural historian believed that he foresaw an authoritarian state whose uneducated masses would stifle cultural life. But Nietzsche again went beyond the position of his "teacher". He did not leave it alone to the division into educated, academic elite and uneducated people, but divided the (apparent) elite again. Here the few actually educated, that is, the great geniuses (Goethe, Schopenhauer), and the “educated” masses of the academic apparatus faced each other. Nietzsche thus narrowed the concept of the elite once more.

Overbeck and Hartmann

In chapters 7 and 8 of Nietzsche's work there are passages about Christianity that are apparently influenced by On the Christianity of our today's theology or conversations with its author, Nietzsche's friend Franz Overbeck . Some of these passages already point to Nietzsche's later, radical criticism of Christianity, while others are rather indifferent or want to protect Christianity as an example of religion in general from excessive “historicizing” . On this subject see ( Lit .: Sommer).

Eduard von Hartmann influenced the writing insofar as Nietzsche made it the target of a violent attack in Chapter 9. Of course, Nietzsche only received a small excerpt from Hartmann's book Philosophy of the Unconscious, which, as already mentioned, he had read a few years before the Untimely was written. His rejection then was by no means as radical as it was here. It evidently served him more as an example of a mood of the times which he was fighting against. See ( Lit .: Salaquarda).

Parallels to Hinduism

Nietzsche's anti-teleological view shows certain parallels to the view of the ancient Indians, even if a direct influence is rather unlikely.

Nietzsche's three types of history correspond to a certain extent to the Hindu world of gods. At its head is a trinity made up of the creator Brahma , the keeper Vishnu and the destroyer Shiva . On the other hand, there is a monumental history that calls for and encourages the new, an antiquarian history that cherishes and maintains what has already been achieved, and a critical history that mercilessly rejects and destroys what is traditional. In the case of the ancient Indians, there is also an unusual view of history from a European perspective. Hegel said that "Indian culture has not developed a sense of history and no historiography that can be compared with European culture". In fact, the Hindu way of thinking is diametrically opposed to Hegel's: the unique and time-bound pales in comparison to the recurring and permanent, which finally found its way into Schopenhauer's philosophy. Nietzsche's later thoughts about the “eternal return” may also be put in this context.

Interpretations and reception

The benefits and disadvantages of history for life were already received in the first phase of Nietzsche's reception towards the end of the 19th century, but especially in the 20th century, much more and more intensively than the other untimely considerations. This is certainly also due to the fact that it is the only one to have a general philosophical topic without considering a specific person.

Recurring and controversial topics at the reception are:

- Interpretation and reinterpretation of the terms monumental - antiquarian - critical,

- Justification and permanent topicality of Nietzsche's contemporary criticism,

- Connection with earlier or later thoughts of Nietzsche.

Andreas-Salomé

Lou Andreas-Salomé already attached great importance to the second untimely one. According to Salomé, history in this work also stands for the life of thought in general, and according to Nietzsche this must serve the life of instinct. In this requirement and the explanations on “plastic power” (HL, Chapter 1) she recognizes an early form of what Nietzsche later called the “Dionysian”. When Nietzsche describes the opposite state of affairs, in which a multitude of foreign influences and thoughts turn people, who are unable to assimilate and organize them, into a “passive arena for mixed struggles” , he anticipates his later concept of decadence . Salomé also investigated Nietzsche's own psychological statement that he was aware of the danger of history because he had observed it in himself. According to her, Nietzsche often projected his self-observations onto his environment, and so history appeared to him to be the danger of the entire age. Therefore, the writing has a contradicting double character, because Nietzsche turns on the one hand against the paralyzing effect of intellectual activity, as he observed it in his contemporaries, but on the other hand against an excess of conflicting influences and sensations, as he found them in himself: “It is a difference like between dullness and insanity. "

In retrospect, the three types of history could, according to Salomé, be assigned to Nietzsche's creative periods: the antiquarian to the philologist, the monumental to the disciple of Schopenhauer and Wagner, and the critical to the positivistic, free-spirited period. In his last creative period Nietzsche then tried to unite and overcome these ways of looking at things. In doing so, he had resorted to the strong natures already demanded of him here, albeit modified, whose unhistorical strength is shown in how much history they can take. What in Nietzsche's early cult of genius the historical-unhistorical, “out of date” man is, who “through the past, superior to the present, builds the future” , later became the redeeming superman under different auspices . Salomé also notes that Nietzsche already introduced the idea of the " Eternal Second Coming " (as an idea of the Pythagoreans ), which later became so important to him. With a series of quotes from works between the Untimely and Also Spoke Zarathustra , she indicates that this thought is also related to Nietzsche's theses in The Use and Disadvantage of History for Life .

Heidegger

Martin Heidegger rated the second untimely one of Nietzsche's most important published works. It is the only work by Nietzsche that is explicitly mentioned and dealt with in Sein und Zeit . Heidegger wants to show here (§ 76) that "history" is existentially only possible because of the " historicity " of existence. A history that is rooted in an “actual” historicity has, according to Heidegger, the possible as its theme: it “reveals” the possibility of existence there. This opening up of possibilities is based neither on the past nor on the present, but on the future. But history also alienates existence from this actual historicity; Heidegger sees the emergence of the problem of historicism as only a symptom of this deeper fate. History can only have benefits and disadvantages for life because existence has already decided on actual or improper historicity. Nietzsche had "recognized the essentials [...] and clearly and emphatically said" about this benefit and disadvantage . Heidegger also agrees with Nietzsche's classification of the three types of history, but sees this trinity as being much more deeply rooted in the existential structure of existence. “Real history” must be the unity of these three types of history. Heidegger seems to assign the future, the possibility to the monumental history, to the antiquarian the past, and finally monumental-antiquarian history is always a critique of the present.

Even after the "Kehre" Heidegger paid attention to Nietzsche's writing: as part of his Nietzsche lectures, he held a seminar on the work in 1938/39 ( lit .: Heidegger). In it he particularly problematized Nietzsche's concept of “life” from the title of the book. He embedded Nietzsche's attacks on historical science in his own critical thoughts on science.

White

In his main work Metahistory, the historian and literary scholar Hayden White examines the connection between historical treatises and their inherent semantics. To this end, he took on Nietzsche's three historical functions (monumental, antiquarian, critical) on the one hand, and his skeptical attitude towards scientific objectivity on the other, and partly reinterpreted them. White assumes that the historian mainly uses one of the four basal tropes (metonymy, synecdoche, metaphor, irony) and has thus already undertaken an immanent evaluation of history. Each of these rhetorical figures would automatically result in a tendentious reading of the text. A truly neutral position can never be achieved.

According to White, the individual is represented as a subject in monumental history , since it was his deeds that seem to have special effects within history. On the linguistic level, this type of historiography makes use of metonymy , i.e. a semantic figure that tries to share and limit reality. It is only through this artificial splitting of history that it is possible to recognize the actual bearers of history in special individuals (e.g. genius, conqueror) or processes (e.g. class struggle). The monumental history thus appears reductionist. Their value lies in their endeavors to create prognoses for the future and thus instructions for action for the present by interpreting the past. Their danger, however, is their one-sided emphasis on individual historical elements.

In antiquarian history, the individual becomes an object in a well-ordered world, through which his identity can be preserved. This history is based on the synekdoche , which represents the elements of reality as parts of a larger whole. This leads to the fact that all historical memory is understood as belonging together. In this way, the individual can then recognize a connection in local and global events. Thus the antiquarian history has an integrative effect. In the best case, the individual would find his own history in that of his culture, since by describing events that are close to him (for example his city history) a relationship to the "great" history can be established more easily. Otherwise, however, there is a risk that a retreat to a pure repetition of the past would take place - regardless of whether this was significant or not.

Critical history makes use of another semantic figure, namely irony , which, through mockery, dissolves a people's sick past. In this way, on the one hand, the pathos of monumental and, on the other hand, the blasphemous nature of antiquarian history can be revealed. This “merciless” irony stripped reality of all myths , but it could leave behind an unbearable void. This leads to either sick nihilism or animal regression. As a fourth linguistic figure, the metaphor must therefore keep irony in balance: the cruel and cold reality is reinterpreted in a romanticizing way through metaphorical terms.

Vattimo

Gianni Vattimo considers the font to be "particularly fascinating, although it [...] raises and asks more problems and questions than it solves and answers". Vattimo thinks that the second untimely one can "only be understood with difficulty as the end point of a development or as a preparation for later theses - such as the doctrine of the Eternal Second Coming -" and holds the opposite thesis that Nietzsche had his position represented here in the further development of his philosophy cleared by and by, for at least as likely.

Vattimo considers the criticism of “historicism” as one of the predominant intellectual currents of the 19th century to be particularly important. This criticism is directed less against Hegelian metaphysics itself than against its social consequences, education and upbringing which is one-sidedly focused on historiography. Vattimo particularly emphasizes Nietzsche's criticism of the feeling of epigony . The people of the late 19th century actually felt themselves to be the end and climax of "world history" through the teachings of Hegel, Darwin and positivism - possibly in popularized form . With the description of the weakened personality, who has an excess of knowledge but no internal reference to it and always needs new stimulants, Nietzsche had foreseen "a characteristic sign of mass culture [...] in the 20th century" . Vattimo, however, criticizes Nietzsche's suggestion of falling back on “ supra-historical ” powers, which is not sufficiently well thought out: “In view of the clarity and unambiguity of the destructive provisions, the constructive aspects of Scripture [...] appear at best as a collection of demands that are largely indefinite stay."

Between the emergence of From the benefits and disadvantages of history for life and human, all-too-human (1878), Vattimo dated the beginning of philosophical postmodernism : Nietzsche clearly saw that “overcoming” - a term that Vattimo had widely discussed borrowed from Heidegger juxtaposes "twisting" - itself a typically "modern" act and therefore not applicable to modernity itself. In his early writing he tried the unconvincing recourse to superhistorical and etherizing powers, in his following period Nietzsche decided to dissolve modernity through the "radicalization of the very tendencies that constitute this modernity itself" .

Further

Several interpreters have criticized Nietzsche's concept of culture, which is also used here (“unity of the artistic style in all expressions of life of a people”, as already mentioned in the first untimely one ). The demand for such a unity misunderstood the valuable possibilities of pluralism in art and culture. It is also surprising that Nietzsche does not ask the question of the extent to which his criticism itself is historical. In general, he does not give any formal reasons for his theses, the whole text does not argue, but insists on its own, unconditional validity. (Erwin Rohde, incidentally, already expressed a similar criticism after being asked to do so by Nietzsche: “You deduce too little, but leave more to the reader than is cheap and good to find the bridges between your thoughts and sentences” ) Indeed it is but by no means take for granted, for example, that there is a contradiction between scientific activity and vitality . The contrast between history and life or, more generally, scientific knowledge and life is only asserted by Nietzsche, not proven.

The question of whether the text is still up-to-date or not - the latter because its audience and the object of criticism are no longer available - naturally becomes more important as the time lag between its publication increases. So far, there has not been a clear answer to this, rather it is being discussed controversially ( lit .: Borchmeyer).

Those who share Nietzsche's attacks against historicism also view his proposed solutions critically. The recourse to “supra- historical ” forces, namely art and religion, is not convincing. Accordingly, Nietzsche himself subjected precisely these two to sharp criticism in his next creative phase.

literature

expenditure

See Nietzsche edition for general information.

- In the by Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari justified Critical Edition (KGW) is the Use and Abuse of History for Life can be found in

- Section III, Volume 1 (together with The Birth of Tragedy, First and Third Out of Time Contemplations), ISBN 3-11-004227-4 . The follow-up report, ie the critical apparatus for this, can be found in Section III, Volume 5, ISBN 3-11-007774-4 . See web links.

- The same text is provided by the Critical Study Edition (KSA) in Volume 1 (together with The Birth of Tragedy, all other Untimely Considerations, posthumous Basel writings and an afterword by Giorgio Colli). The volume KSA 1 is also published as a single volume under ISBN 3-423-30151-1 . The associated apparatus can be found in the commentary volume (KSA 14), pp. 64–74.

- In 1995 the Ernst Klett Schulbuchverlag published an edition of the font with materials and interpretations, including texts by Wilhelm Weischedel , Hans-Georg Gadamer , Jacob Burckhardt and others, edited by Joachim Vahland, ISBN 3-12-692040-3 .

- In addition to individual editions of the font from Reclam ( ISBN 3-15-007134-8 ) and Diogenes ( ISBN 3-257-21196-1 ) there are editions of all outdated considerations (which are subject to KSA text-critical)

- published by Goldmann Verlag with comments by Peter Pütz , ISBN 3-442-07638-2 ,

- published by Insel Verlag with an afterword by Ralph-Rainer Wuthenow , ISBN 3-458-32209-4 .

Secondary literature

All major monographs on Nietzsche also deal with the second out-of- date consideration, so see the list of literature in the article "Friedrich Nietzsche" . Detailed bibliographies can be found in the works of Salaquarda and Sommers listed here as well as at links below . See also: Philosophy bibliography : Friedrich Nietzsche - Additional references on the topic

- Dieter Borchmeyer (Ed.): "On the benefits and disadvantages of history for life". Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-518-28861-X . (Collection of essays related to the work, among the authors: Hans-Georg Gadamer , Hermann Lübbe , Kurt Hübner , Klaus Berger , Harald Weinrich and others)

- Jacobus ALJJ Geijsen: History and Justice: Basic features of a philosophy of the middle in Nietzsche's early work. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1997, ISBN 3-11-015647-4 . (Monographs and texts on Nietzsche research, No. 39, plus dissertation at the University of Leiden)

- Gerhard Haeuptner: The view of history of the young Nietzsche: attempt of an immanent criticism of the second outdated view. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1936.

- Martin Heidegger : On the interpretation of Nietzsche II. Untimely consideration: "On the benefits and disadvantages of history for life". Heidegger Complete Edition, Vol. 46, Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-465-03286-1 .

- Jörg Salaquarda: Studies on the Second Untimely Consideration. In: Nietzsche Studies. International Yearbook for Nietzsche Research 13, 1984, pp. 1-45, ISSN 0342-1422 . (Salaquarda examines in three short studies: 1. why Nietzsche later disregarded writing, 2. the origin of writing, 3. function, justification and scope of the dispute with Hartmann.)

- Hartmut Schröter: Historical theory and historical action - on Nietzsche's criticism of science. Mäander, Mittenwald 1982, ISBN 3-88219-108-2 . (At the same time dissertation at the University of Tübingen)

- Andreas Urs Sommer : The Spirit of History and the End of Christianity. To the gun cooperative of Friedrich Nietzsche and Franz Overbeck. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-05-003112-3 . (Examines similarities and differences in the understanding of history Overbeck and Nietzsche and pays special attention to the benefits and disadvantages of history for life .)

- Hayden White : Metahistory: the historical imagination of 19th century Europe. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1994, ISBN 3-596-11701-1 . (Examines the language of historiography according to literary criteria and makes strong reference to Nietzsche's theory of history.)

Web links

The benefits and disadvantages of history for life at Zeno.org .

- Full text

- Literature on From the benefits and disadvantages of history for life , directory of the Weimar Nietzsche bibliography

Individual evidence

- ^ Lou Andreas-Salomé: Friedrich Nietzsche in his works. First edition 1894, here quoted from the paperback edition by Insel Verlag, Frankfurt 2000, ISBN 3-458-34292-3 . - "Of more permanent interest [than the first untimely one] is the second, most valuable work," p. 92.

- ^ Andreas-Salomé: Friedrich Nietzsche in his works. P. 93.

- ^ Andreas-Salomé: Friedrich Nietzsche in his works. P. 95.

- ^ Andreas-Salomé: Friedrich Nietzsche in his works p. 99.

- ^ Gianni Vattimo: Nietzsche: an introduction. Metzler, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-476-10268-8 , p. 22.

- ^ Vattimo: Nietzsche: an introduction. P. 22.

- ^ Vattimo: Nietzsche: an introduction. P. 25.

- ^ Vattimo: Nietzsche: an introduction. P. 26.

- ^ Gianni Vattimo: Nihilism and Postmodernism in Philosophy. In: the same: The end of modernity. Reclam, Stuttgart 1990, ISBN 3-15-008624-8 , p. 178f.

- ^ Vattimo: Nihilism and Postmodernism in Philosophy. P. 180.

- ↑ UB I, Chapter 1, KSA 1, p. 163; UB II, Chapter 4, KSA 1, p. 274.

- ^ Letter of March 24, 1874, KGB Section II Volume 4, p. 419ff.