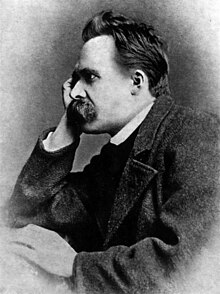

Nietzsche versus Wagner

Nietzsche contra Wagner is Friedrich Nietzsche's last work, which he put on paper at the end of 1888 before collapsing on January 3, 1889 in Turin .

Months earlier he had already written several writings there, which, among other things, dealt with his relationship with Richard Wagner : The Wagner case , Götzen-Dämmerung and Ecce homo . With this selection of more or less revised texts, Nietzsche, author of The Birth of Tragedy , wanted to rebut the accusation that he only went from ardent admirer to bitter opponent of the composer with the Wagner case .

For example, he put together “files” from earlier writings - for example from Human, All Too Human - which were intended to prove that he had already said goodbye to Wagner in 1876, during the first festival . The doubts of the young author Nietzsche about the Wagner case have been clearly confirmed by research on the basis of early writings and drafts.

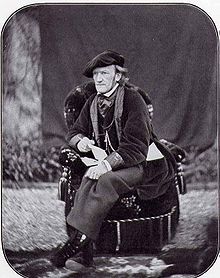

Richard Wagner and Friedrich Nietzsche

The Wagner-Nietzsche relationship was ambivalent. As a young professor in Basel, Nietzsche was enthusiastic about Wagner, who was 31 years his senior, and visited him regularly in Tribschen from May 1869 . He admired and adored Wagner, as did his young wife Cosima. In return, Nietzsche was accepted like a son by the Wagners. Many letters from this time testify to the more than friendly relationship. This is how the 24-year-old Nietzsche wrote to his friend Erwin Rohde after he first met Wagner in Leipzig:

- Before and after the table, Wagner played all the important parts of the “Meistersinger”, in which he imitated all the voices and was very exuberant. Because he is a marvelous and ardent man who speaks very quickly, is very funny and makes a society of this most private kind very cheerful. In the meantime I had a long talk with him about Schopenhauer . It was a pleasure for me to hear him talk about him with indescribable warmth, what he owed him, how he was the only philosopher who had recognized the essence of music. Afterwards he read out a piece from his biography which he is now writing, an extremely delightful scene from his student life in Leipzig that I cannot think of now without laughter; Incidentally, he writes extremely skillfully and wittily.

Wagner intended to involve Nietzsche in the organization of the first Bayreuth Festival . Nietzsche was not averse and wrote several positive articles and essays, including a. Wagner in Bayreuth . On Wagner's 60th birthday, Nietzsche wrote:

- Beloved Master, now it is really two generations that the Germans have you - and there are certainly many who, like me and my friends, celebrate the next Ascension Day as the day of your journey on earth, at the same time telling themselves what the lot of each one is for Earth-wandering genius will be, a lot that is truly reminiscent of a journey into hell (...) What would we be if we weren't allowed to have you, and what would I be, for example (as I feel every moment) other than a dead-born being ! I always shudder at the thought that perhaps I might have stayed apart from you: and then it was really not worth living, and I don't even know what to do with the next lesson. Now I have learned one thing: that at some point the Germans will have to start forming an “audience” for you: and I wish, along with my friends, to be included in this audience.

For personal or idealistic reasons that have not yet been clearly clarified (Wagner's distance from earlier ideals, return to Christian symbolism with Parsifal or Bayreuth's decadence), the relationship cooled off and broke up with the last meeting in September 1876 in Sorrento. Since then there has been no correspondence, but one wrote on top of one another. Only after Wagner's death in 1883 - Nietzsche is said to have suffered greatly as a result - Nietzsche was able (apparently) to free himself from Wagner and now criticized him increasingly violently.

Cosima Wagner and Nietzsche

A lot has been speculated about the relationship to this day. Nietzsche met the slightly older Cosima Wagner in Tribschen when she was already heavily pregnant with her son Siegfried, and also stayed in Tribschen when the child was born in June. It was primarily Cosima who corresponded with Nietzsche and was obviously just as competent a discussion partner for him as her husband. Nietzsche wrote her several poems and composed for her. He later called her his "Ariadne", as in his poem "Lamentation of Ariadne". On the other hand, he later accused her of having negatively influenced his idol Richard Wagner, because the cultural revolutionary he admired had, in his view, "crept to the cross". Cosima, his Catholic "fetter", could only be guilty of having "corrupted" him and "held idolatry" with him. His profound comment, often misinterpreted as an alleged Parsifal criticism:

- Who are sick of every fetter,

- Peaceless, unencumbered spirit,

- Always more victorious and yet bound,

- More and more fouled, more torn,

- Until you drank poison from every balm -

- Sore! That you too sank on the cross,

- You too! You too - one conquered!

- I stand long before this spectacle

- Breathing prison, grief and resentment and tomb,

- In between incense clouds, church fragrance,

- Strange to me, horrible and afraid to me.

- I throw my fool's cap in the air while dancing,

- Because I sprang from!

Nietzsche is even clearer in his work The Wagner Case :

- Wagner redeemed woman; the woman built Bayreuth for him for it. Total sacrifice, total devotion: you have nothing that you wouldn't give him. The woman becomes impoverished in favor of the master, she becomes touching, she stands naked in front of him. - The Wagnerian woman - the most graceful ambiguity there is today: she embodies Wagner's cause, in her symbol his cause wins. Ah, that old robber! He robs us of our young men, he robs us of our women and drags them into his cave ... Ah, that Minotaur!

When Nietzsche was admitted to the Jena sanatorium after his collapse, his saying was noted there: “My wife Cosima Wagner brought me here.” Later, several draft letters to Cosima Wagner were found in his estate.

Dated January 3, 1889 (the day of its collapse):

- To Princess Ariadne, my beloved.

- It is a prejudice that I am human. But I have often lived among people and know everything that people can experience, from the lowest to the highest. I was Buddha among the Indians, Dionysus in Greece - Alexander and Caesar are my incarnations, likewise the poet of Shakespeare Lord Bakon. In the end I was Voltaire and Napoleon, maybe Richard Wagner too ... But this time I come as the victorious Dionysus who will make the earth a festival ... Not that I have much time ... The heavens are happy that I am here ... Me also hung on the cross ...

Dated approximately December 25, 1889:

- Dear Madam,… basically the only woman I have adored… please accept the first copy of this Ecce homo. It basically treats the whole world badly, with the exception of Richard Wagner - and Turin as well. Malvida also appears as Kundry ... The Antichrist.

Nietzsche versus Wagner

In his very last work, which again dealt with Wagner and bears the subtitle “ Files of a Psychologist ”, Nietzsche deals with similarities and contradictions.

The Wagner case

Nietzsche wrote this "relief" with the subtitle: "A musicians problem" in September 1888 and already made it clear in his foreword that he was a child of a decadent time, but, unlike Wagner and Schopenhauer, that he was "his." Disease ”, defends against it and now through“ self-conquest ”the whole“ fact of being overlooked from an immense distance ”. He begins his critical remarks with a comparison between the “lovable” music of Georges Bizet's Carmen , which embodies the bright and this world, and Wagner's heavy, sultry atmosphere (“water vapor”).

Nietzsche's criticism of Wagner is multi-layered, and although it was sparked primarily by his late work ( Parsifal ), he now also applied it to earlier works and the Ring of the Nibelung , which he had celebrated in the Untimely Reflections . As a former “student” of Schopenhauer (Schopenhauer as educator), who later opposed his teacher's pessimism, Nietzsche analyzed his influence on Wagner. While Wagner, as a revolutionary thinker, first saw the evil of the world in contracts, laws, institutions - the contract motif in the ring - his view of the world later changed and the Christian motive of redemption took center stage. Many of Wagner's characters were to be "redeemed" from now on. After the “Götterdämmerung of old morality”, Wagner's “ship” ran “happily on this path” (of optimism) for a long time until it hit the “reef” of Schopenhauer's philosophy. He then translated the ring into Schopenhauer's: Everything in the world is going wrong and everything is perishing. So only the nothingness, the extinction, the “Götterdämmerung” the redemption - and this nothingness is now celebrated by Wagner incessantly. Nietzsche repeats several times that Wagner is the artist of " decadence ":

- I am far from harmlessly watching when this decadent spoils our health - and the music too! Is Wagner human at all? Isn't it more of a disease?

In his art is mixed in the most seductive way what the world needs most: the brutal, the artificial and the innocent (idiotic). His music is a ruin and aims "on the nerves". Nietzsche increases himself in the course of his remarks on the one hand in "ranting tirades" and describes Wagner as the greatest actor, on the other hand as a genius who has "increased the ability of music to speak immeasurably". He doesn't want anything other than "effect". With sarcasm he states:

- Everything that Wagner can do, no one will imitate him, no one has imitated him, no one should imitate him ... Wagner is divine!

Ecce homo

In his autobiographical balance sheet, which was written almost at the same time and acts like a magnifying glass of Nietzsche's thought, he often takes a stand on Wagner. In Ecce homo alone, he deals with Wagner more than 70 times, although depending on the intention it is easy to quote Nietzsche against himself.

literature

- Giorgio Colli, Mazzino Montinari: Friedrich Nietzsche, Critical Study Edition . Munich 1999. ISBN 3-110-16598-8

- Ivo Frenzel: Friedrich Nietzsche . Hamburg 1966. ISBN 3-499-50634-3

- Kerstin Decker: Nietzsche and Wagner, Story of a love-hate relationship (2012)

- Joachim Köhler: Friedrich Nietzsche, Cosima Wagner . Hamburg 1998. ISBN 3-499-22614-6

- Nicholas Martin: Nietzsche contra Wagner: “How I got rid of Wagner” , in: Nietzscheforschung 2 (1995), pp. 267–273.

- Andreas Scheib: Nietzsche's Carmen. Notes on an aberration , in: Nietzsche Studies 37 (2008), 249–254.

- Karl Schlechta: Friedrich Nietzsche, works . Digital library Berlin. ISBN 3-89853-431-6

- Andreas Urs Sommer : Commentary on Nietzsche's Der Antichrist. Ecce homo. Dionysus dithyrambs. Nietzsche contra Wagner (= Heidelberg Academy of Sciences (ed.): Historical and critical commentary on Friedrich Nietzsche's works, Vol. 6/2), Berlin / Boston: Walter de Gruyter 2013. ( ISBN 978-3-11-029277-0 ) (new standard commentary, comments on each individual passage in detail and compares it with the earlier texts used by Nietzsche).

- Andreas Urs Sommer: Nietzsche contra Wagner , in: Stefan Lorenz Sorgner, H. James Birx, Nikolaus Knoepffler (eds.): Wagner and Nietzsche. Culture - work - effect. Ein Handbuch , Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, pp. 441–445.

- Elliott Zuckerman: Nietzsche and Music. "The Birth of Tragedy" and "Nietzsche contra Wagner" , in: Symposium 28/1 (1974), pp. 17-30.

Web links

- Foreword to Richard Wagner (1871), in: The Birth of Tragedy , Critical Complete Edition, edited by Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, Berlin / New York, Walter de Gruyter, 1967 E-Text nietzschesource.org

- Richard Wagner in Bayreuth (1876) = Untimely considerations, Fourth piece E-Text nietzschesource.org

- The Wagner case (1888) e-text nietzschesource.org

- Nietzsche contra Wagner (1888) e-text nietzschesource.org

- Text in German on zeno.org

Individual evidence

- ^ Nietzsche contra Wagner , in: Nietzsche manual, Life - Work - Effect, Metzler, Stuttgart, Weimar 2000, Ed. Henning Ottmann, p. 129