Being And Time

Being and time is the main work of the early philosophy of Martin Heidegger (1889–1976). Published in 1927, it has been one of the 20th century's works of the century .

In it, Heidegger tries to put the philosophical doctrine of being , the ontology , on a new foundation. To this end, he first unites different methodological currents of his time, in order to then successively prove ("destroy") the traditional philosophical conceptions as wrong. According to Heidegger, philosophical prejudices not only shape the entire Western intellectual history, but also determine everyday self-understanding and understanding of the world.

The work, which is often abbreviated as SZ , more rarely SuZ , is considered the impetus for modern hermeneutics and existential philosophy and continues to shape the international philosophical discussion to this day. It is fundamental for an understanding of the main works of philosophers such as Jean-Paul Sartre , Hans-Georg Gadamer , Hans Jonas , Karl Löwith , Herbert Marcuse and Hannah Arendt . The philosophers Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Emmanuel Levinas and the Japanese Kyoto school also received influences and incentives . In psychology attacked Ludwig Binswanger and Medard Boss on ideas in psychoanalysis Jacques Lacan . French structuralism and post-structuralism, as well as deconstruction and postmodernism, owe decisive suggestions to Heidegger.

overview

theme

The theme of the treatise is the “question of the meaning of being in general”. On the one hand, Heidegger asks about “ being ”, i.e. what is . If he asks at the same time about its meaning, then this means that the world is not a formless mass, but that there are meaningful relationships between individual beings in it. Being has a certain unity in its diversity. Everything that is seems to be structured by such meaningful references and its being is determined. For example, there is a relationship between hammer and nail and the person who uses these things for his own purposes. With the “question of the meaning of being in general ”, Heidegger aims to uncover the relationships on which all individual meaningful references in daily life are based. The question is not simply synonymous with the question of "the meaning of life ." It also differs from the question of a (ultimate) reason for being ("Why is something at all and not rather nothing?")

According to Heidegger, occidental philosophy has given various answers in its tradition as to what it means by “being”, but it has never posed the question of being in such a way that it inquires about the meaning of being, that is, it examined the relationships inscribed in being . Heidegger criticizes the previous understanding that being has always been described as something that is individual, something that is present. The mere presence, however, does not make it possible to understand references: simply by establishing that something is, one cannot understand what something is. If you just take the hammer as an existing piece of wood and iron, its relation to the nail cannot be understood from here.

For Heidegger, this failure of the philosophical tradition is primarily due to the fact that the relation to time is completely disregarded in the conception of being as something present . When defining being as, for example, substance or matter , being is only presented in relation to the present : what is present is present, but without any reference to the past or future . In the course of the investigation, Heidegger would like to show that, on the other hand, time is an essential condition for an understanding of being, since it - to put it simply - represents a horizon of understanding on the basis of which things in the world can first develop meaningful relationships between one another. The hammer, for example, is used to drive nails into boards in order to build a house that will protect people from coming storms in the future . So it can only be in relation to the people and in the overall context of a time-structured world understand what the hammer out of an existing piece of wood and iron is . Heidegger would like to correct this disregard of time for the understanding of being in “Being and Time” , which explains the title of the work. Heidegger is not only concerned with correcting the history of philosophy: the mistakes in philosophy are rather characteristic of Western thinking in general, which is why Heidegger also wants to achieve a new self-understanding of man with his investigation.

For this, thinking must be placed on a new basis. If , for the reasons mentioned, matter can no longer be accepted as the foundation of all that is (as materialism does, for example ), then Heidegger has to find a new foundation for his theory of being ( ontology ). Because of this project, he also calls his approach presented in “Being and Time” fundamental ontology : In “Being and Time” , the ontology is to be placed on a new foundation. Even if Heidegger later deviates from his approach chosen here, the attempt to clarify an original meaning of His Heidegger's life's work determines far beyond “Being and Time” .

Emergence

“Being and time” was written under time pressure. Heidegger had been an associate professor in Marburg since 1923, but had not published anything for almost ten years. If he wanted to hope for a call to Freiburg, he had to submit something. To do this, he condensed the material created during his apprenticeship and organized it systematically. In the context of the Heidegger Complete Edition , which has been published since 1975, the path that led to “Being and Time” can be understood very well. This shows how years of preparatory work are included in “Being and Time” . The 1927 lecture “Basic Problems of Phenomenology” also anticipated many ideas in a different form. The first part of “Being and Time” appeared in 1927 under the title “Being and Time. (First half) " in the eighth volume of the " Yearbook for Philosophy and Phenomenological Research " published by Edmund Husserl . A second part did not appear, the work remained a fragment.

Influences

In its strictly conceived form, "Being and Time" shows strong references to Kant's " Critique of Pure Reason " , with whose work Heidegger variously before and after the writing of his main work , as with individual passages that explicitly comment on Immanuel Kant's statements has dealt with. Hardly conceptually, but also for "Being and Time" are influential " metaphysics " and " Nicomachean Ethics " of Aristotle , with whom Heidegger since his reading of Brentano's dissertation "From the manifold meaning of being Aristotle" busy. Heidegger's terms such as presence , handiness and existence indicate a reference to the Aristotelian terms of theoria , poiesis and praxis . The extent to which “Being and Time” is based on Heidegger's interpretations of Aristotle is made clear by an early sketch by Heidegger, the so-called “Natorp Report” .

The phenomenology of Husserl is the basic method of investigation for Heidegger, although he makes some changes to it. For Heidegger, Husserl gets into an aporia when he emphasizes, on the one hand, that the ego belongs to the world and, on the other hand, the simultaneous constitution of the world by the ego. Heidegger tries to radically overcome this subject-object split ( I as the subject of the world and I as the object in the world ): The world does not stand opposite Heidegger's “subject”, Dasein, but belongs to Dasein .

Heidegger himself saw his ontological approach in sharp contrast to philosophical anthropology , which appeared at about the same time in the works of Max Scheler and Helmuth Plessner . Also to Wilhelm Dilthey and Georg Simmel and their work on the historical side of the human condition to the transience and fragility, Heidegger borders in a special way from: He tried both unhistorical phenomenology and their alleged misconduct, the factuality to circumnavigate of life, as well historicism , which tends towards relativism . Various interpreters have pointed out that Heidegger is probably based on his analysis of early Christian life experience developed in previous works, as found in Paul , Augustine and the early Martin Luther . Despite everything, Heidegger's hermeneutic approach is indebted to Dilthey's formulation: "Thought cannot go back beyond life."

Furthermore, the existential philosophy of the Danish philosopher Sören Kierkegaard - especially the analysis of fear - influenced Heidegger's work. Heidegger also deals with Hegel's concept of time , which he uses to explain the failures of a philosophy in the Cartesian-Kantian tradition.

construction

The book that was finally published only includes an introduction and the first two parts of the first volume; Heidegger initially did not work out more. Heidegger gave up this work entirely in the 1930s. However, an indication that the unfinished work will remain a fragment is only found in the 7th edition from 1953, when the title addition "First half" has now been omitted.

According to the original plan, “Being and Time” should consist of two volumes, each of which was divided into three parts:

- The interpretation of Dasein in terms of temporality and the explication of time as the transcendental horizon of the question of the meaning of being

- The preparatory fundamental analysis of existence

- Existence and temporality

- Time and being

- Principles of a phenomenological destruction of the history of ontology

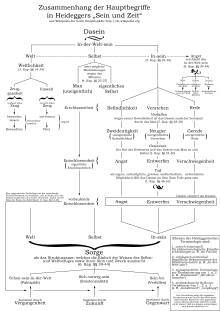

This structure shows how the investigation proceeds: Heidegger begins (Part 1.1.) With an analysis of the relationship between man (“Dasein”) and the world, the “fundamental analysis of Dasein” ( fundamental ontology ). Here the so-called existentials of existence are exposed. From this point of view, Heidegger works out a definition of existence as a structure, which he calls care . The interpretation of care (part 1.2.) Proves temporality as its "sense" .

The following part (1.3.) Should have built on this interim result and should have drawn the bow from temporality to time and from this to the meaning of being in general , in order to ultimately return to the initial question. With the knowledge gained in this way, other philosophies should be “destroyed” in a further step, which no longer occurs in the work that has remained fragmented. Heidegger later turned away from the fundamental ontological approach, which he called his turn , and looked for a different approach to the question of being . Nevertheless, many connections can be drawn between his later writings (such as the essay “Time and Being” from 1962) and Being and Time . How continuity and breaks in Heidegger's work are ultimately to be assessed is controversial in research. Equally controversial are the attempts to reconstruct the part of the work that has not been preserved through scattered utterances and texts (such as the “basic problems of phenomenology” ) and their possible interpretations.

Basic concepts of the work

Being and being

Fundamental to Heidegger's approach to the problem of being is the distinction between being and being, the emphasis on the ontological difference between the two. With “being” Heidegger describes - to put it simply - the “horizon of understanding”, on the basis of which only things in the world, the “being”, can encounter. If being, for example, is understood in the context of Christian theology, then against this background everything appears to be created by God. Heidegger takes the position that being (the 'horizon of understanding') has not been explicitly discussed up to its present. According to Heidegger, this has led to a confusion between being and being since the classical ontology of antiquity.

However, being is not only the 'horizon of understanding' that is not thematized, but also denotes that which is , thus has an ontological dimension. One could say that Heidegger equates understanding with being, which means: only what is understood is also and what is is always already understood, since beings only appear on the background of being. That something is and what is something always go hand in hand. This also makes the meaning of time for a determination of being understandable, insofar as time proves to be a condition for any understanding.

According to Heidegger, a central mistake of classical ontology is that it posed the ontological question of being by means of merely ontic beings. Disregarding the ontological difference, she reduced being to beings. With this return, however, it is precisely, according to Heidegger, that it obstructs the being of beings. The hammer may serve as an example for this: If one assumes that only beings are in the form of matter, then when asked what a hammer is , the answer is: wood and iron. However, one can never understand that the hammer is “the thing to hammer” after all. According to Heidegger, this does not spare people's self-conception either. The reason for this is that man always trains his understanding of the world and the things in it. If he now wants to understand himself, then he backprojects the understanding of being gained from the world (for example, “the world consists of things”) onto himself and sees himself as a thing. The set Heidegger's conception of man as an existence contrary that that man is emphasized not a thing but only in life volunteer there .

For Heidegger, the disregard of the ontological difference is the reason why being was often only addressed as the mere presence (of things or matter) in the tradition. To avoid this error, Heidegger is assumed instead of things that bring those into view of the question of Being, namely the human being as existence .

The sharp separation between ontic and ontological determinations on which “Being and Time” is based leads to a duplication of the terminology: numerous concepts of the work therefore appear with an ontic and an ontological meaning. The fact that everyday language and the philosophical terminology of tradition do not differentiate here is a fact that has often led to misunderstandings in the reception of “Being and Time” .

| Ontic term / determination | Ontological term / determination |

|---|---|

| Being | Be |

| human | To be there |

| existential | existential |

| Mood | State of mind |

| language | speech |

| "World" (with quotation marks: sum of beings) | World (in its worldliness) |

Insofar as the confusion of ontic determinations and ontology is also the basis of the previous metaphysics (see forgetting of being ), “Being and Time” stands in the beginning for a destruction of all previous ontology and metaphysics, a claim that is ultimately not fully met due to the incomplete nature of the work can be, but which the later Heidegger radicalized again in a different way after “Being and Time” .

To be there

Dasein as the starting concept instead of the already widely interpreted and categorized concept of human being.

Perhaps the most important concept of the work is Dasein ; This is what Heidegger calls beings that "ever am". Heavoidsthe obvious expression human because he wants to distance himself from traditional philosophy and its judgments. Under existence is not a general category "man" is understood, cherishes about everyone already theoretical prejudices, the new term is to open up the possibility that philosophy to the immediate life experience of individuals back to tie. At the same time, the term enables a demarcation from the Kant- based epistemology . In his investigation, Heidegger does not start from a knowing subject , but from an understanding existence . This shifts the question of how the subject recognizes the objects, to what meaningful relationships things have in the world and how one understands them: The being of things and of Dasein isquestioned aboutits meaning .

To answer the question about the meaning of being, Heidegger begins his investigation with Dasein , because it poses the question of being. In order to be able to ask this question at all, Dasein must have a certain prior understanding of being - otherwise it would not even know what to ask for (compare Plato's dialogue Menon ).

Uncovering the existentials as a phenomenological analysis of Dasein

Everyone believes they know roughly what “being” means and says “I am” and “that is”. Dasein (alone) can marvel at the fact that “there is something at all and not rather nothing.” Dasein is present - in Heidegger's words: it is thrown into “being-there” - and has to become its being and to Its behavior as a whole. It has to lead a life and for this it is necessarily always somehow related to itself and the world. It therefore seems to Heidegger to be advantageous to start his analysis with existence.

In order to track down the structure of Dasein and its behavior, Heidegger analyzes Dasein using phenomenological methods and thus exposes its existentials , that is, what Dasein disposes and determines in its life. The preliminary result of the analysis is: Dasein is both

- always "already in" a world (thrownness) , d. H. factually integrated into a cultural tradition, as well

- “In advance” (draft) , in that it understands this world and grasps or rejects possibilities in it and thirdly

- “With” everything that is within the world ( falling into the world), that is, with the things and people to which it is directly oriented.

Heidegger sees the “being of Dasein ” in the unity of these three points - in the typical Heideggerian terminology: “The being of Dasein means: already-being-in-(of-the-world) as being-at (something within the world) Beings) ".

Care as the being of Dasein

The being of Dasein - the total existential structure of Dasein - is what Heidegger calls "worry" for short. “Care” in the Heideggerian sense is a purely ontological-existential title for the structure of the being of Dasein. This concept of care has therefore only superficially something with everyday terms such concern ( concern ) or carelessness to do. Dasein is always worried in a comprehensive sense, in that it finds itself in the world, interprets it in an understanding from the outset and is referred to things and people from the beginning.

Heidegger is aware that identifying the structure of being of Dasein with worry is problematic. In § 42 he tries to “prove” this existential interpretation pre-ontologically. To this end, he draws on an ancient fable by Hyginus ( Fabulae 220 : "Cura cum fluvium transiret ..." ). From today's standpoint, one may find such a test at least surprising; Here, however, a procedure by Heidegger appears which will be characteristic of the later Heidegger. Heidegger also directed this pre-ontological proof against Husserl's theoretical concept of intentionality . The term care , on the other hand, is intended to describe a human way of being that is not limited to the cognitive gaze of the world, but is initially involved in the practical handling of the world, which can then also shape a theoretical understanding of the world.

temporality

If one takes a closer look at the determination of Dasein as being towards death, it becomes clear that only the temporality of Dasein enables it to orient itself towards death. Thus, according to the determination of existence as care, namely as -already-being-in-(the-world) as being-with (beings encountered within the world) , temporality proves to be fundamental for the entire care structure: temporality is that Sense of concern. It is made up of three ecstasies : past, future and present. Heidegger assigns this to the corresponding provision of care:

- Already-being-in-the-world: a past

- To be with (that currently to be worried): present

- To be ahead of oneself (in the draft): future.

At the point at which Heidegger tries to derive a general concept of time from them , the book breaks off.

Dilapidation and authenticity: the man

Heidegger uses the term man to describe the cultural, historical and social background of existence. As a cultural being, man is always dependent on and determined by a tradition. Heidegger calls the sum of the cultural and social norms and behaviors facticity . They can never be disregarded because they essentially belong to the human being as a cultural being. On the one hand, it is culture that enables people to do certain things and thus enables them to be free; on the other hand, it can also be that his own culture determines his thinking and acting in advance without him becoming aware of it. The existence is then at the mercy of the given behavior patterns and views. Heidegger describes this state of being at the mercy as improper existence .

For Heidegger, the state of inauthenticity is the average initial state of man. So existence is necessarily determined by the cultural and public behavioral offers. These take away from Dasein its real being ; Existence is in the dominion of others. The others are not special in this regard, and so the answer to the question of who the existence is in its everyday life is: the man .

“We enjoy and enjoy ourselves as we enjoy; we read, see and judge literature and art how to judge; but we also withdraw from the 'big bunch' as one withdraws. "

The man watches over every advance exception:

“Everything that was original is smoothed out overnight as it has long been known. Everything that has been fought for becomes handy. Every secret loses its strength. The concern of the average reveals again an essential tendency of existence which we want to call the leveling ”. (P. 127)

Heidegger calls this function of the man the public . The one also takes responsibility for existence, because Dasein can always refer to it: That's just how you do it. "Everyone is the other and nobody is himself."

Heidegger contrasts improper external determination with actual self-being as an existential (non-existential) modification of the man. In the juxtaposition of unity and one, Heidegger searches for the possibility of an authentic life, the actual being able to be oneself . For this purpose, Heidegger analyzes the possible actual or improper behavior of Dasein to its existentials. The possibility of actual existence turns out to be

- the temporal ecstasy of the future towards which Dasein resolutely projects , d. H. by aligning its conduct of life with interests that it has critically examined and considered worthwhile.

- the temporal ecstasy of the past - Here Heidegger is based on ideas from Dilthey . As Dasein chooses “its heroes” from the past and does not simply imitate their existing possibility of actually being able to be oneself, but rather answers them , the repetition of the possibility offers it the chance of actually being able to be oneself.

In order for such a turn to take place towards authentic life, the "call (it) of conscience" is required. In this context, Heidegger describes a structure in which the conscience “calls” one's own existence to be itself. This can be understood as a function of conscience because existence is required to no longer just refer to the man in its actions, but to take responsibility for its decisions from now on .

State of mind

In “Being and Time”, the state of mind plays an important role as a pre-reflective relation to the world of existence. Heidegger not only sees understanding (or even pure reason ) as access to the world, but emphasizes that things in the world concern us . The state of mind is therefore essential for the world to be accessible. Fear is of particular importance as a basic state of mind, because it opens existence to being-in-the-world and brings it before it. Fear lets the totality of the for-for-and-for-sake collapse: things become meaningless to us and we are thrown back on ourselves. Fear lets the world step back from what the world has to offer and puts us in a moment of reflexive self-reference. This can lead to the decision to consciously take your own existence into your own hands and lead an authentic life that does not lose itself in the contingent offers of the public. Such a way of being corresponds to actual existence. After Heidegger examined the temporality of existence in the second part of “Being and Time”, this phenomenon can also be understood with regard to the future. Here death turns out to be a moment that adds existence to authenticity, also with regard to its temporal extension: As an inevitable last possibility, it defines the scope for action that is given to one.

Being to death

The determination of existence as care, as well as being ahead of oneself and already being in shows that the human being is always "more" than his bare body: he is a person with a past and a future. These belong to existence, only with them is it a whole. It is limited by its end, death. However, this is not only a one-time event at the end of existence, but it also determines existence in his life, because it defines the decision-making space that lies ahead of existence. Dasein chooses possibilities within this decision-making space. At the same time, death opens up and makes existence aware of its scope for decision-making: Only in the face of death does existence grasp itself as a person with a past and a future of its own . Death reveals this to existence through its characteristics. No one can be represented before death, it is always someone's death who completely occupies one as an individual : in death it is all about me.

What the word death means cannot be learned through reflection, but only in the mood of fear . Through this essentially revealing function of fear, Heidegger also assigns a world-recognizing function to moods compared to reason. Fear as an ontological term does not designate the mere feeling of fear or the fear of some thing. Heidegger also does not mean death and fear as evaluative terms, but rather determined by their function: death and fear isolate existence and make it clear to him the irrevocable uniqueness of each of its moments.

Because of the effect that death has on the fulfillment of life, Heidegger defines Dasein as “being to death” - see also the influence of Kierkegaard's “funeral speech” and other Christian authors such as Paul, Augustine and Luther. In this way Heidegger distances himself even further from a conception of man as what is present, because in being to death time becomes of fundamental importance for the determination of the being of Dasein. The anticipation of death becomes the starting point for an independent, authentic and intense - - in Heidegger's words, real not from the life fallenness determine to the commonplace-social "Man" and life can be .

Heidegger's methodical approach

- Hermeneutic Phenomenology

Following the phenomenology developed by his teacher Husserl, Heidegger developed his own approach, which he called the phenomenological hermeneutics of facticity from 1922 onwards . Like phenomenology, Heidegger also wants to uncover the basic structures of being, phenomena. Within the framework of a philosophy of consciousness, Husserl classified all phenomena as phenomena of consciousness. Through eidetic reduction , entities of consciousness should be removed from the stream of consciousness through self- observation , from which a “philosophy as a strict science” should then have been gradually built up. Heidegger, however, does not share Husserl's restriction to consciousness; for him, human life with all its fullness cannot be traced back to conscious experiences alone. Heidegger too would like to use the phenomenological method to expose basic phenomena, but he does not see these in consciousness alone, but rather they should be taken from factual life in its full breadth and historical development.

Human life, however, is primarily oriented towards meaningful references to the world and Heidegger here follows Dilthey's saying: “You cannot go back beyond life.” This should mean that there is no process of “meaning formation”, no becoming Makes sense, but always precedes it. Sense cannot be constructed or increase from “a little sense” to “a little more”. Once there is meaning, one cannot go back to it. Sense accompanies all experience and precedes it. Once there are fundamental references in the world, it makes sense “as a whole”. If philosophy wants to extract basic phenomena from this meaningful world, then this can obviously only be done through understanding and interpretation . So phenomenology must be combined with Dilthey's method of hermeneutics . This phenomenological hermeneutics is then supposed to have factual life as its object , or, as it is then called in “Being and Time” , analyze Dasein . Heidegger assumes that the "vulgar" phenomena of human existence are based on those phenomena that can be viewed as a condition for the possibility of those vulgar ones.

- Ontological approach

The fact that the world “is” only as meaningful has an ontological meaning: Since meaning represents a new quality and thus cannot simply be constructed from matter in a step-by-step structure, meaning and being coincide for Heidegger. World and understanding are the same. The world consists of meaningful relationships between things and is only for the person who understands it. The structure of understanding is such that everything individual is always classified in a larger context: Just as the hammer as an individual tool can only be meaningfully understood in the overall context of other tools that are used for building a house. Since, however, only the individual things occur in the world, never the world as the underlying background of meaning, Heidegger calls the world transcendental , i.e. That is, it can never be experienced sensually and yet it is a condition of the possibility of all experience . The possibility of meaning is also tied to two temporal dimensions, namely the “from which” and the “whereupon” something is understood. This transcendental horizon of temporality thus proves to be a fundamental prerequisite for meaning: on the one hand, meaning must always be preceded by an understanding ; on the other hand, a future world is needed towards which understanding is oriented.

Effect and reception

The book was a sensation in philosophical circles and made Heidegger famous overnight because it seemed to open up a new perspective on people. Gadamer : "All of a sudden, world fame was there." The use of Heidegger's idiosyncratic language briefly became fashionable. Heidegger's pupils at the time, Hans Jonas , Karl Löwith , Herbert Marcuse and Hannah Arendt , were among the first generation to acquire and develop ideas from “Being and Time” , sometimes at a critical distance .

- Gadamer and Hermeneutics

Heidegger's attempt to re-establish the science of history and his hermeneutical approach were significant in terms of impact history : Dasein always has a certain prior understanding of itself, of being and beings, the world is given to him as a meaningful totality, behind the meaning of which one cannot go back. Heidegger's student, Hans-Georg Gadamer , based his hermeneutics on this. However, instead of an existential analysis that exposes supra-historical structures, Gadamer's thesis of the historicity of all understanding takes the place. Gadamer no longer sees the task of hermeneutics in examining existence in its everyday life, but rather directs it towards traditional events, with regard to which the question arises as to how we can understand documents at all that are in a completely different understanding horizon were drafted. These ideas come to a certain conclusion in Truth and Method (1960). This revival of hermeneutics as a method created a field of influence in which both Emil Staiger's immanent interpretative teaching in literary studies and Paul Ricœur's method of reception aesthetics and Gianni Vattimo's “weak thinking” can be found .

- Arendt

Hannah Arendt designed her political philosophy “ Vita activa or Vom aktivigen Leben ” (1958/60) against “Being and Time” . Arendt felt it was a deficiency that Heidegger's “decisionism” of determination remains peculiarly indeterminate when it comes to decision-making criteria for political engagement. Against Heidegger's strong emphasis on the death as a defining principle of the people, she designed a philosophy of Gebürtlichkeit ( birth rate ).

- Marcuse

Directly following “Being and Time” , Herbert Marcuse extended the existential analytical approach in his early works towards a Hegelian philosophy of history and a Marxian dialectic , which was reflected in 1931 in “Hegel's ontology and the theory of historicity” . His later work “The One-Dimensional Man” (1964) takes up the concept of inauthenticity and decay, which Marcuse now interprets with regard to the senseless world of consumption, goods and production of late capitalism. He opposes it with the actual existence of the “great refusal” that goes hand in hand with authentic engagement.

- Sartre

The existentialism , especially Jean-Paul Sartre , found himself in direct successor of "Being and Time" . In the title of his work “Das Sein und das Nothing” (1943), Sartre follows on from Heidegger, in which he emphasizes the absolute freedom of all action, but also of having to act. Heidegger has rejected this “existentialist interpretation”, but the fact that existentialism has adopted fundamental theses from this book can hardly be doubted.

- Further reception

Maurice Merleau-Ponty received essential incentives for his “Phenomenology of Perception” (1945), in which he incorporated the foundation of a body a priori. Even Emmanuel Levinas ethics "the other" is still of "Being and Time" marked, but so that it exerts strong criticism of Heidegger.

In psychology , Ludwig Binswanger and Medard Boss developed existential analytical psychologies with which they hoped to overcome some of Freud's mistakes. In psychoanalysis , Jacques Lacan is influenced by the idea of ontological difference .

In Protestant theology, Rudolf Bultmann followed up on Heidegger's existential analysis. Since this only reveals the general structure of the existing existence, but this "bare existence" is not yet filled with concrete content, Bultmann would like to merge it with the demythologized Christian message:

"By not answering the question of my own existence, existential philosophy makes my own existence my personal responsibility, and in doing so it makes me open to the word of the Bible."

“Being and Time” also had a great influence on modern Japanese philosophy in its internationally most important form of the Kyoto school . The book has been translated into Japanese six times to date, which does not even apply to Kant's Critique of Pure Reason .

Heidegger also worked on structuralism , post- structuralism , as well as on deconstruction and postmodernism . Michel Foucault's discourse analysis finds connection with Heidegger's later concept of the “history of being”; for Jacques Derrida , the concept of difference (in the form of différance ) is formative.

Analytically trained philosophers like Hubert Dreyfus in the USA take up Heidegger's pragmatic approaches in particular, but also his analysis of the world as a horizon of understanding (for example in connection with stuff, the “totality of stuff”), which they oppose purely intentionalist approaches. For example, it was only after Dreyfus referred to Heidegger that John Searle expanded his concept of intentionality to include a horizon of understanding.

criticism

General and methodological criticism

Language and intelligibility

Various critics accuse Heidegger of the work's poor intelligibility. Some critics - such as the philosopher and sociologist Hans Albert - are of the opinion that the work as a whole says very little, at least little new, and conceals this with many words. The first critic of Heidegger's language was Walter Benjamin , who had already rejected the use of neologisms in philosophy in 1914 . Adorno criticized much later, but afterwards, the " jargon of authenticity " , as he called Heidegger's style. Terms of the vernacular would suggestively reinterpreted here to a certain way of popularizing of thinking, such as the use of the term concerned .

Lack of explicit ethics and the use of implicitly evaluative terms The

subject of constant debate is the question of whether Heidegger's early philosophy, the main part of which is “Being and Time” , shows tendencies related to his later commitment to National Socialism . (See Heidegger and National Socialism .) What is noticeable here is the lack of any ethics in the book. At second glance, however, it is noticeable that a number of passages can also be read well within the framework of the circle of ideas that gained influence in the 1920s as the Conservative Revolution . Heidegger's conservatism is recognizable in his going back to the “original”, in which he often uses metaphors from rural life . Heidegger emphasizes again and again that his sentences and terms are not meant to be judgmental; But it is easy to change parts of the work - passages against the obsession with the man , against the talk of the everyday and the calls for authenticity in contrast to the "improper" everyday life - also politically and in the context of the criticism of modernity , of anonymity in the Mass society and read on liberal democracy .

The interpretation concept pursued by Johannes Fritsche, Emmanuel Faye , François Rastier and others, according to which Being and Time is a Nazi cashier or ontologize proto-Nazi and anti-Semitic terms, was sharply called "patently false claim" by Thomas Sheehan. and rejected as a “chaotic Mardi Gras parade” (“shambolic Mardi Gras parade”) and rejected by Kaveh Nassirin as “exegetical emotion ” and “retrospective dragging of epochs ”, because the work does not contain explicit Nazi terms or Nazi concepts.

Use of terms with traditional negative connotations

Further criticism was directed against Heidegger's preference for terms with negative connotations in the classical sense, such as death , worry and fear . In the whole book, areas like love , lust or joy hardly appear. Critics polemically called Heidegger's approach a “philosophy of death”, while Heidegger's pupil Hannah Arendt designed a philosophy of “nobility” as a counterpoint.

Husserl's criticism Husserl,

too, viewed the work with a certain skepticism from the start. He saw it as an "anthropological regional ontology" and missed the line loyalty to his method of "getting back to the things themselves". Later he also criticized the central role that death plays in Heidegger. Husserl considered Heidegger's approach to be incompatible with the phenomenological method ; In particular, his phenomenology of the lifeworld differs considerably from Heidegger's concept of being- in-the-world ; it is more concrete and physical, also, so to speak, sociological in the effort to circumnavigate the "cliff of solipsism " (Sartre) - while Heidegger focuses on the occasional spiritual, "Essential" stands out. Maurice Merleau-Ponty followed the Husserlian model in this regard. Sartre commutes between the two.

Heidegger's own turning away from being and time

- See turn

Heidegger himself turned away from his previous philosophy with the turn in the mid-1930s . The question of being was still his biggest and only interest, but he considered the approach via Dasein , which he had chosen in “Being and Time” , to be wrong. This turning away is relevant in the “ Letter on» Humanism ” , which Heidegger wrote to Jean Beaufret in 1946 , in which he reinterpreted the interpretation of care : Dasein is now characterized by a“ care for being ”. It can be said that Heidegger thought his own program was too anthropocentric , since he had tried to explain the entire understanding of existence through concern . Heidegger's “ Denk-Weg ” can therefore be seen as self-criticism . On the other hand, you could still find him in old age in front of his hut in Todtnauberg , reading "Sein und Zeit" - because it was something "reasonable".

Criticism of the concept of truth

Ernst Tugendhat has devoted himself in detail to the difference between Husserl's and Heidegger's concept of truth and criticizes Heidegger for the fact that he already starts the truth event at the level of disclosure instead of demanding a comparison of the matter with itself.

Criticism of the basic concept of being and time

Ernst Tugendhat also criticizes Heidegger's basic concept of being and time, namely to understand the meaning of being from time, as insufficiently founded. In this context he accuses Martin Heidegger, for example, that he “never clearly stated what the difference between being in the sense of being at hand and being in the sense of being there should be, and it also remains unclear why a person is because he this peculiarity of existence […] is not nevertheless something that is present. Heidegger did not specify any criteria for differentiating between different modes of being. And also the idea that one must derive the accessibility and thus also the being from one mode from another, that one is 'more original' than the other and the theoretical awareness of the existence must be derived from the practical relation of existence to itself , are simply preconceptions of Heidegger that he did not justify. "

In his study on “Being and Time”, Andreas Graeser criticizes their central theses. Like Tugendhat, he points out, among other things, that Heidegger uses “being” both to designate the linguistic expression “being” and to designate what is meant by it, so that it is unclear what Heidegger has with the “meaning” of the question of being means. Graeser finally comes to the following judgment: “Heidegger's theses are rarely well founded. This deficiency literally renders them worthless in many cases. This is all the more regrettable as some theses have inner persuasive power and could well be true. "

Criticism of individual aspects

Contradiction between unity and Man

Heidegger's attempt to work out the conditions and possibilities for an authentic, i.e. real life in “Being and Time” leads to a strong contrast between unity (individual) and man (community). The fact that these two cannot be bridged leads to the fact that existence as determined has to defend itself against falling into the one. Antisocial tendencies can definitely be made out here, as the sharp contrast means that existence is no longer possible in being with one's being. On the other hand, there are also readings that understand Heidegger's considerations in the sense of a suggestion to differentiate between the positive-relieving and the negative-alienating function of the man. Heidegger himself later opposed an interpretation of unity as the opposition of “I” and “we”. The unity is neither of the two.

Another criticism of the Heideggerian conception of the man was formulated by Murat Ates, according to which the anonymity of the man as nobody could not mean that the social differences, preferences and power relations could be leveled out. “Obviously one benefits from the man in different ways, there are further sub-modes within the rule of the man, which in turn are in a hierarchical order. There are simply those privileged by the man. ”The decisive factor here is the extent to which the individual is represented by the individual or, conversely, to what extent one is represented by the everyday average. The possibility of being immersed in a social average and thus being able to be anonymous appears to be a privilege that not everyone is entitled to within the rule of the man.

Leveling the present

The great importance that Heidegger ascribes to the timelines of the future and past for the actual being able to be oneself leads to a leveling of the present. The rich differentiations of the future through existence, design, leading to death, determination and that of the past through facticity, thrownness, guilt, repetition stand in opposition to the present, which remains empty in its determination. The present is thus, as it were, "swallowed up" by the "past future".

Missing theory about the social constitution of man

In the chapter devoted to the worldliness of the world, the world shows itself above all as a world of useful things for the individual existence. The other people encounter the individual existence only through these things (e.g. through the boat of the other on the bank). It is criticized that the world in “Being and Time” is not a public world of the common being of people and that there is no theory that plausibly explains access to the other. This is countered by the fact that Heidegger's definition of the who of Dasein as man does contain a cultural-sociological thesis that shows that man is essentially determined by a cultural tradition and socio-social specifications down to his most intimate emotions - his who .

Overestimation of the practical reference to the world

In his endeavor to emphasize the priority of the practical reference to the world over the theoretical, Heidegger even exaggerates his view in "Being and Time" to the effect that nature (forests, rivers, mountains) only appears under considerations of utility (forest, Hydropower, quarry). Heidegger himself will reject this view in his later criticism of technology.

Contradiction between the transcendental and the factual world

A contradiction can be made out between the totality of materiality, which is constituted by existence and flows into its for-sake, and the insignificance of the totality of materiality, discovered in the mood of eeriness. The uncanniness is based on the facticity of the world that is not available for Dasein , while Heidegger, on the other hand, claims that the worldliness of the world is based as transcendental in Dasein.

Death analysis and actual self-being

Heidegger's connection between death and authenticity can also be read the other way around. If Heidegger speaks of the fact that existence takes hold of itself only in the face of death, which leads to determination , on the other hand an experience of death would be conceivable that does not lead to increased self- reference but rather serenity . Günter Figal has put forward a reading according to which Heidegger basically does not need the phenomenon of death in order to come to a free and proper relationship to himself and the world. The His death is therefore unnecessary for Figal as we do not have to necessarily involve death in our discussions to assess our prospective opportunities.

Failure to observe the corporeality of Dasein

Heidegger completely excludes the corporeality of Dasein in his investigation. That this leads to one-sidedness is shown, for example, by his analysis of the mood, for which he defines the past as the reason: “It is important [...] to prove that the moods are existential in what they are and how they are 'Mean' are not possible, unless on the basis of temporality. ”One could hook this point critically and ask whether the bodily present constitution of existence and with it something non-temporal also has an influence on moods. A first critic in this regard was Helmuth Plessner . Heidegger's connection of space to temporality in § 70 - which he will later describe as untenable in “Time and Being” - is only possible because he ignores the corporeality of Dasein. Heidegger's space is a design and action space that needs temporality, but it is still overlooked that the physical-sensual orientation in the space precedes the acting. As early as 1929, during the Davos disputation with Ernst Cassirer , who had dealt with the “spatial problem, language problem and death problem” in his Davos lectures on Heidegger, Heidegger referred to the existence of human beings who are “bound in one body” and referred to them Relationship between the body and beings.

Criticism of the concept of fear

The philosopher Reinhardt Grossmann criticizes Heidegger's attempt, based on Søren Kierkegaard , to connect the concept of fear “both with nothing and with being in the world”. So "fear is not a mood , ... but an emotion ." Furthermore, the indefinability of the object of fear - in comparison to fear - a misunderstanding, since "fear has a very ordinary, albeit repressed, object."

Notes on reading

Heidegger's language takes getting used to. He uses ancient sentence constructions, many neologisms and hyphenated words (such as being- in-the-world , stuffing whole ). This stems from Heidegger's intention to break away from the previous philosophy and to use new words in order to leave well-trodden paths of thought. In addition, Heidegger uses many words that are known from everyday language, but mean something completely different by them (such as worry , fear ).

It should also be borne in mind that expressionism flourished in the 1920s and a rhetoric developed that can now often come across as comical to idiosyncratic and overly pathetic. This has also radiated on the philosophical prose. It is therefore usually necessary to read into Heidegger's philosophical language, which is a strain on ordinary language. Linguistic similarities exist, for example, to the poems of Stefan George , Rainer Maria Rilke and Georg Trakl .

However, Heidegger's language is not as incomprehensible as it may appear at first glance. There is no question that it has a strong suggestive effect. If you first try to understand Heidegger's language in the literal sense, it becomes clear that Heidegger proceeds very carefully and with very small steps. This procedure, owed to the high self-claims to the importance of his work, sometimes gives the impression of inflatedness .

The philosophy of phenomenology belongs to the inseparable context of being and time . Heidegger developed his approach by going through Husserl's phenomenology . However, as described above, the differences are serious. Heidegger himself saw Karl Jaspers as a kindred spirit and also refers to him in Being and Time .

As a supplement to the introduction, Heidegger's early work Advertisement of the Hermeneutic Situation from 1922, in which the direction of the investigation of being and time is anticipated and some later thoughts are presented, sometimes with different vocabulary.

expenditure

- Martin Heidegger: Being and time. 11th edition. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1967, ISBN 3-484-70109-9 (PDF 2.6MB)

- Martin Heidegger: Being and time. 12th edition. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1972, ISBN 3-484-70109-9

- Martin Heidegger: Being and time. 19th edition. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2006, ISBN 3-484-70153-6 (earlier edition also under ISBN 3-484-70122-6 ).

- Martin Heidegger: Being and time. Edited by Friedrich-Wilhelm von Herrmann . Vittorio Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 1977 ( Heidegger Complete Edition , Vol. 2, Dept. 1, Published Writings 1914–1970).

The edition by Niemeyer-Verlag is on the same page as Volume 2 of the Heidegger Complete Edition from Verlag Vittorio Klostermann. SZ is used as a sigle for being and time .

The first editions of Sein und Zeit contained a dedication from Heidegger to Edmund Husserl, who was of Jewish descent. This dedication was missing from the fifth edition from 1941. According to Heidegger, it was removed under pressure from publisher Max Niemeyer . The dedication is included in all editions after the Nazi era .

literature

Philosophy bibliography : Martin Heidegger - Additional references on the topic

Reading aids and comments

- Günter Figal : Martin Heidegger. Phenomenology of freedom. 3. Edition. Athenäum Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2000.

- Günter Figal: Martin Heidegger for an introduction. 6th expanded edition. Junius Verlag, Hamburg 2011.

- Andreas Luckner: Martin Heidegger: Being and time. An introductory comment. 2nd corrected edition. UTB, Stuttgart 2001.

- Thomas Rentsch (Ed.): Being and time. 2nd edited edition. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2007 (laying out classics).

- Thomas Rentsch: Being and Time: Fundamental ontology as hermeneutics of finitude. In: Dieter Thomä (Hrsg.): Heidegger manual: Life - work - effect . Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2003, pp. 51–80.

- Erasmus Schöfer : The language of Heidegger . Günther Neske publishing house, Pfullingen 1962.

- Michael Steinmann: Martin Heidegger's “Being and Time”. WBG, Darmstadt 2010.

- Ernst Tugendhat : The concept of truth in Husserl and Heidegger . De Gruyter, Berlin 1967.

Helpful for intensive text work

- Hildegard Feick, Susanne Ziegler: Index to Heidegger's “Being and Time”. 4th revised edition. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1991, ISBN 3-484-70014-9 .

- Rainer A. Bast , Heinrich P. Delfosse: Handbook for text study of Martin Heidegger's "Being and Time". frommann-holzboog, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1980, ISBN 3-7728-0741-0 .

Commentary and interpretation by Heidegger's student Friedrich-Wilhelm von Herrmann closely based on this

-

Friedrich-Wilhelm von Herrmann : Hermeneutical Phenomenology of Dasein.

- Volume I "Introduction: the exposition of the question of the meaning of being". Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 1987, ISBN 978-3-465-01739-4 .

- Volume II "First section: The preparatory fundamental analysis of existence" § 9 - § 27. Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 978-3-465-01740-0 .

- Volume III "First section: The preparatory fundamental analysis of existence" § 28 - § 44. Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-465-01742-4 .

- Friedrich-Wilhelm von Herrmann: Subject and Dasein: Basic Concepts of “Being and Time”. 3rd ext. Edition. Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2004.

- Friedrich-Wilhelm von Herrmann: The concept of phenomenology in Heidegger and Husserl. Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 1981.

In the context of phenomenology

- Andreas Becke: The path of phenomenology: Husserl, Heidegger, Rombach. Publishing house Dr. Kovac, Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-86064-900-0 .

- Bernhard Waldenfels : Introduction to Phenomenology . Fink, Munich 1992.

- Karl-Heinz Lembeck : Introduction to phenomenological philosophy . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1994.

- Tobias Keiling: History of Being and Phenomenological Realism. An interpretation of Heidegger's late philosophy. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2015, ISBN 3-16-153466-2 .

Contemporary history background

- Rüdiger Safranski : A master from Germany. Heidegger and his time . Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2001 (largely biographical, not systematic).

- Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht : 1926. A year at the edge of time . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2003 (on contextualization in the Conservative Revolution).

Critical discussion

- Hans Albert : Critique of Pure Hermeneutics . Mohr, Tübingen 1994.

- Theodor W. Adorno : Negative dialectic / jargon of authenticity . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-518-29306-0 (Collected Writings, Vol. 6).

- Martin Blumentritt: "No being without being" - Adorno's Heidegger criticism as the center of negative dialectics . Philosophical Conversations "Issue 48. Helle Panke - Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Berlin. Berlin, 2017, 48 pp.

Web links

- Lecture: Hubert Dreyfus on “Being and Time” .

- Rafael Capurro: Being and time and the twist into synthetic thinking .

- English translation glossary

Individual evidence

- ↑ Cf. Otto Pöggeler : Martin Heidegger's path of thought . Stuttgart 1994, p. 48.

- ↑ Martin Heidegger: Being and time. (First half.) In: Yearbook for Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. Volume 8, 1927, pp. 1-438 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ See explanatory Franco Volpi : The status of existential analytics. In: Thomas Rentsch (Ed.): Being and time. Berlin 2001, p. 37f.

- ↑ Critically edited and published by Günther Neumann at Reclam under the title Phenomenological Interpretation of Aristoteles , Stuttgart 2002.

- ↑ Cf. Franco Volpi: The status of existential analytics. In: Thomas Rentsch (Ed.): Being and time. Berlin 2001, p. 30f.

- ↑ Quoted from Christoph Demmerling: Hermeneutics of the everyday and being in the world. In: Thomas Rentsch (Ed.): Being and time . Berlin 2001, p. 90. (Wilhelm Dilthey: Ideas for a descriptive and dissecting psychology. Collected writings Volume 5, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2006, p. 173.)

- ↑ Cf. Thorsten Milchert : Christian roots of Heidegger's death philosophy . Marburg 2012.

- ↑ Hans-Georg Gadamer: Philosophical apprenticeship years. Frankfurt am Main 1977, p. 210.

- ↑ Quoted from Heinz Zahrnt: The matter with God. Munich 1988, p. 245.

- ^ Hans Albert : Treatise on Critical Reason , 5th Edition. Mohr, Tübingen 1991, p. 164 ff.

- ↑ See Luc Ferry, Alain Renaut: Heidegger et les Modernes. Paris, 1988

- ↑ Johannes Fritsche: Heidegger's Being and Time and National Socialism in: Philosophy Today 56 (3), Fall 2012, pp. 255–84; ders .: National Socialism, Anti-Semitism, and Philosophy in Heidegger and Scheler: On Trawny's Heidegger & the Myth of a Jewish World-Conspiracy in: Philosophy Today, 60 (2), Spring 2016, pp. 583–608; François Rastier, Naufrage d'un prophète: Heidegger aujourd'hui , Paris, 2015; Emmanuel Faye: Heidegger, l'introduction du nazisme dans la philosophie: autour des séminaires inédits de 1933–1935 , Paris: Albin Michel, 2005, p. 31 f.

- ↑ Thomas Sheehan: Emmanuel Faye: Introduction of Fraud into Philosophy? In: Philosophy Today , Vol. 59, Issue 3, Summer 2015, p. 382 .

- ↑ Thomas Sheehan: L'affaire Faye: Faut-il brûler Heidegger? A Reply to Fritsche, Pégny, and Rastier , In: Philosophy Today , Vol. 60, Issue 2, Spring 2016, p. 504 .

- ↑ Kaveh Nassirin: "Being and Time" and the exegetical emotion: Review of the anthology "Being and Time" renegotiated. Investigations into Heidegger's main work, FORVM a . PhilPapers pdf, p. 7 .

- ↑ See, for example, Otto Friedrich Bollnow: The essence of mood , 1941.

- ↑ Günther Anders - About Heidegger (2001) [1] at perlentaucher.de

- ^ Ernst Tugendhat: Essays 1992–2000 , 1st edition. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 2001, p. 189

- ↑ Andreas Graeser: Philosophy in 'Being and Time'. Critical considerations on Heidegger , Sankt Augustin: Academia, 1994, p. 109.

- ↑ See Hans Ebeling : Martin Heidegger. Philosophy and ideology. Rowohlt TB-V., Reinbek 1991, p. 42ff.

- ↑ See Hubert Dreyfus: Being-in-the-World. A commentary on Heidegger's Being and Time. Cambridge 1991, p. 154 ff.

- ↑ Cf. Otto Pöggeler: Martin Heidegger's path of thought. Stuttgart 1994, footnote 32.

- ↑ Murat Ates: Philosophy of the ruling class. An introductory final note . Vienna 2015, p. 91

- ↑ Cf. Otto Pöggeler: Martin Heidegger's path of thought. Stuttgart 1994, p. 210.

- ↑ Cf. “... and the trees are good for heating up” in Heinrich Heine : Travel Pictures I (Die Harzreise) , 1826.

- ↑ Cf. Romano Pocai: The worldliness of the world and its repressed facticity. In: Thomas Rentsch (Ed.): Being and time . Berlin 2001, p. 55f.

- ↑ Cf. Romano Pocai: The worldliness of the world and its repressed facticity. In: Thomas Rentsch (Ed.): Being and time . Berlin 2001, p. 64.

- ↑ See Byung-Chul Han: Types of Death. Philosophical Investigations into Death. Fink, Munich 1998, pp. 70-73.

- ↑ See Günter Figal: Martin Heidegger. Phenomenology of freedom. Athenäum Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1988, pp. 190-269.

- ↑ Martin Heidegger: Being and time. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2006, p. 341.

- ↑ See Thomas Rentsch: Temporality and Everydayness. In: Thomas Rentsch (Ed.): Being and time . Berlin 2001, p. 203.

- ↑ See Helmuth Plessner: Gesammelte Schriften. IV pp. 20, 22; VIII pp. 40, 232, 243f., 355f., 388, Frankfurt am Main 1980ff.

- ↑ Reinhardt Grossmann: The Existence of the World - An Introduction to Ontology , 2nd Edition. Ontos, Frankfurt 2004, p. 149 f.

- ↑ See Erasmus Schöfer : The language of Heidegger. Günther Neske publishing house, Pfullingen 1962.

- ↑ See Bernhard Waldenfels : Introduction to Phenomenology . Fink, Munich 1992.

- ↑ For example in: Phenomenological interpretations of Aristotle. Reclam 2002, ISBN 3-15-018250-6 .