Davos disputation

The Davos Disputation (also: controversy of Davos , official name: "Arbeitsgemeinschaft Cassirer - Heidegger") is a dialogue that is famous in the history of modern philosophy, which the cultural philosopher and semioticist Ernst Cassirer and the philosopher of being and hermeneutic Martin Heidegger on March 26, 1929 on the occasion of II. International Davos University Courses (from March 17th to April 6th) held in the Hotel Belvédère in the Swiss climatic health resort . At the symposium, the Kantian question “What is man?” Was formally on the topic, but it was already apparent in advance that not only the representatives of two generations, but also two philosophical worldviews would meet. In reception, the controversy is often seen as an echo of the tradition of public debates by philosophers during the scholastic period .

In addition to the philosophical contradictions of the dispute, the special contemporary historical and socio-political aspects also contributed to the enormous response, which continues to the present day in the specialist literature, such as, in retrospect, the fact that Cassirer and Heidegger published on the glamorous scene of the five years earlier Romans Der Zauberberg in the last phase before the Great Depression and the end of the Roaring Twenties faced a Jew who would soon flee from Nazi Germany and a future member of the NSDAP.

This article is based on the version of the dispute published in the Heidegger Complete Edition; that of the Cassirer estate edition is added as a supplement. In one case, reference is made to the version published by G. Schneeberger.

prehistory

International Davos university courses

After the German defeat in the First World War and the restrictions that had been imposed on German scientists on the international stage, the idea arose to bring German and French researchers together on the neutral soil of Switzerland “in the spirit of Locarno”: Jean Cavaillès therefore spoke of a “ Locarno of intelligence ”. Before that there had already been the idea of creating a university offer for the many student patients in the climatic health resort, to which Albert Einstein , the keynote speaker at the first university courses, pointed out in his 1928 lecture: “And yet moderate intellectual work is generally not detrimental to recovery, yes even indirectly useful (...). With this in mind, the university courses were launched, which not only provide vocational training but are also intended to stimulate intellectual activity. ”Health, education and international understanding were the combined concerns of the university days, and Einstein reaffirmed the early spirit of a European community:“ Let us Also do not forget that this company is excellently suited to establishing relationships between people of different nations, which are beneficial to the strengthening of a European community feeling. "

During these first university courses in 1928, there was a lively discussion between the theologians Erich Przywara and Paul Tillich on the “understanding of the concept of grace”, in which other researchers also took part. "The character and dynamics of this discussion were seen as the impetus for the idea of having Heidegger and Cassirer discuss with each other in the following year."

Davos 1929

The invited company of 1929

As was the case with the university days of 1928, the following year were also attended by top-class scientists and students, some of whom were to become luminaries in their field. Among the approximately one hundred invited participants were Germans, French, Italians and Swiss from various disciplines: the lecturers included, in addition to Heidegger and Cassirer, the philosophy professor at the Sorbonne Léon Brunschvicg , the Zurich philology professor Ernst Howald , the philosopher and rector of the University of Basel Karl Joël , the linguistic philosopher Armando Carlini from Pisa, who lectured on Benedetto Croce and Italian idealism, the Frankfurt professor of philology Karl Reinhardt and the Dutch philologist and linguist Hendrik Pos. Among the students were the sociologist Norbert Elias , the philosophers Herbert Marcuse , Rudolf Carnap , Maurice de Gandillac and Joachim Ritter , the latter photographed the encounter between Cassirer and Heidegger and was one of the recorders. Emmanuel Levinas and Otto Friedrich Bollnow caricatured the disputants in the final revue. In addition to Ritter and Bollnow, the Heidegger students Hermann Mörchen and Helene Weiss wrote transcripts of parts of the dispute. The philosopher Arthur Stein had come from Bern and asked Heidegger some introductory questions at the beginning of the debate.

The readings before the dispute

In the days from March 17th until the debate on the 26th, Cassirer and Heidegger held lectures in Davos, which formed the thematic background for the subsequent discussion between the two, to which reference was immediately made.

- Heidegger's Davos Kant lectures

Heidegger's three Davos lectures were intended to “prove the thesis: Kant's Critique of Pure Reason is one, or the first, explicit foundation of metaphysics.” With this provocative tenor, the young lecturer opposed “the traditional interpretation of Neo-Kantianism” KrV "is not a theory of scientific knowledge - no epistemology at all." The three lectures were based on the first three chapters of the book Kant, published in 1929, and the problem of metaphysics , which Heidegger added a fourth chapter after Davos. Together with the synopsis of the Davos lectures , Heidegger's lectures there can be largely reconstructed, at least in terms of content.

- Cassirer's Heidegger Lectures

One week before the disputation, on March 19, 1929, Cassirer gave the “Heidegger Lectures”, in which he dealt with Heidegger's “spatial problem, language problem and death problem”. Cassirer's Davos lectures, like the disputation, were recorded by the students Hermann Mörchen and Helene Weiss in the form of a synopsis and only published in the estate edition in 2014. Initially treated Cassirer space as Heidegger's "pragmatic space", but referred soon to the biologist Jakob von Uexküll - as Cassirer professor in Hamburg - and discussed the space as a "space consciousness", finally with his philosophy of symbolic forms taken Distinctions in "space of expression, space of representation, space of meaning", whereby Heidegger was no longer mentioned. In Cassirer's Heidegger lectures, the different uses of the terms that were supposed to determine the last quarter of the disputation in the following week became apparent.

In the case of the “language problem”, Cassirer first recognizes a central thought from being and time and quotes it - “In order for cognition to be possible as a contemplative determination of what is present, a deficiency in worrying dealing with the world is required beforehand” - yes Cassirer criticizes this “abstinence” from purposeful thinking, which, according to Heidegger, leads to the “just-still linger-with” mode, the mere “understanding of what is available”, which is to be recognized as “terminus a quo, as a starting point”, as incomplete : “Isn't there a lack of focus on the terminus ad quem?” More clearly: “Can we stop at this beginning? - or is not (...) the step from the 'ready-to-hand' to the 'available' the real problem. "The transition to the possibility of object constitution remains unclear with Heidegger, whereby Cassirer means the language:" So we ask: which is the medium that from the world of what is merely at hand to that of what is available, from mere “arsenal” to real “objectivity”? And here we refer to the world of symbolic forms as the general medium. But we cannot reflect on the totality of these forms here - we only pick out one essential and decisive one: we consider the world of language. "

Even after Cassirer's extensive discussion of the death problem in Heidegger, the conclusion is the same: “Heidegger has shown how this condition of fear becomes the central point of existence. But again this only describes the starting point, the terminus a quo, not the terminus ad quem. It is not the fear of death as such, but the overcoming of this fear (...) that is characteristic of human existence. ”In the disputation, Heidegger will take up the argument and present it the other way round, as Cassirer's weakness with regard to the terminus a quo (see below: “Heidegger: The untranslatable of thrownness”).

Disputants from two different worlds

In the still icy alpine heights of Davos, the city citizen Cassirer fell ill with flu-like infection after the first of his lectures and had to stay in bed for a few days with a high fever. Heidegger, on the other hand, who liked to act as a nature lover, went on extensive ski tours and was mostly seen in a ski suit. Shortly after their arrival, the disputants presented opposites.

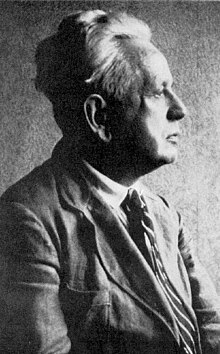

The contrast between the two, however, extended to a number of aspects and was emphasized many times: Cassirer and Heidegger were representatives of learned conformism and rebellious awakening, traditionalism and the demand for destruction, including those of two generations, which was visually reinforced by the fact that the 54-year-old Cassirer already had snow-white hair and the fifteen-year-old Heidegger was a bit skinny and looked awkward, as his student Hans-Georg Gadamer (who was not in Davos) reports: “This confrontation was of course grotesque in terms of the external spectacle. This man of the world and this peasant boy. Heidegger awkward, shy and then, like all shy people, a bit massive. If they then have to assert themselves, then overdo it. Cassirer certainly criticized very quietly. And I can imagine that Heidegger thundered like Jupiter himself. "

The contrasts on various levels continued: “Cassirer was a Jew, from a wealthy family, Heidegger Catholic, from humble backgrounds; Cassirer came from the north, Heidegger from the south of the country. Cassirer's name was associated with the big city through the many well-known Berlin Cassirers, while Heidegger not only came from the country, but rejected life in the big city ”( John Michael Krois ). “On the one hand a personality that one participant describes as 'Olympic', heir to a cosmopolitan education of urban and bourgeois origin, used to dealing with people and dialectically trained, on the other hand the provincial, still young and already famous, but fearful , stubborn and tense, whom Mrs. Cassirer compares to a farmer's son who was forcibly dragged into a castle ”( Pierre Aubenque ).

The profound lectures that Cassirer gave in Davos about Heidegger and also the first meeting of the two, which had taken place a good five years earlier in Hamburg and was mentioned by Heidegger in a detailed note of Being and Time , suggest that both that in the The history of the reception of the disputation occasionally mentioned the rumor that Cassirer underestimated Heidegger, and that a previous opposition to both of them is rather retrospective, not justified by sources. On the occasion of the “Interpretation of Primitive Dasein”, Heidegger mentioned the second volume of Cassirer's Philosophy of Symbolic Forms in Being and Time and asked whether a “more original approach” than Kant's transcendental thought was needed to fathom mythical thinking, and during a "discussion that the author was able to maintain occasionally with C. in a lecture in the Hamburg local group of the Kant Society in December 1923 on 'Tasks and paths of phenomenological research' 'already showed agreement in the demand for an existential analysis."

It should also be mentioned that Heidegger visited Cassirer in Davos at the bedside and "informed him of those of his lectures in which Cassirer could not attend, as it was appropriate for the upcoming discussion."

symposium

Discussors, recorders, documentation

The disputation between Cassirer and Heidegger took place between 10 a.m. and 12 p.m. and was moderated by the Dutch language philosopher Hendrik Pos, one of the lecturers. The students and later philosophy professors Joachim Ritter, as Cassirer's assistant in Davos, and Otto Bollnow made the minutes, which are not always literal transcripts. Regarding the debate led by Heideggerians and Cassirer supporters about the reliability of the protocols, the Cassirer biographer Thomas Meyer initially said: “However, a short version of the protocol was made on the spot from the shorthand notes. There are several copies of it, including with Heidegger's signature. ”These abstracts were initially only circulated privately, one was published in 1960 by Guido Schneeberger. The complete protocol only appeared in 1973 in volume 3 of the Heidegger Complete Edition.

In the extensively edited volume 17 of the Cassirer estate edition, on the other hand, “the more detailed version of the records of Mörchen and Weiss” that can be traced back to a revised postscript ”of the protocols by Bollnow and Ritter mentioned. In the versions of the Heidegger Complete Edition and the abridged protocol published by Guido Schneeberger in 1960, “Stein's questions and Heidegger's answers have not been passed down.” The identification of Stein (“not determined”) missing in the Cassirer edition was made up by Thomas Meyer: " Arthur Stein (1888–1978), who came from Bern, was, as the successor to his father Ludwig Stein, briefly editor of the 'Archive for the History of Philosophy'."

In the version by Bollnow and Ritter and the version printed by Schneeberger, “three questions to Cassirer” are addressed in the course of the discussion, which Schneeberger has added “(stud. Phil. S)” and cannot be identified by one Philosophy students had been put.

In addition to the two disputants, three other people are also documented who intervened in the discussion with speeches. The exchange of words handed down by Schneeberger between Heidegger and a war veteran (see below) is not included in the shorthand transcripts, minutes and postscripts.

theme

Already in the first speech, Cassirer's immediate reference to Heidegger's Kant lectures of the days before showed that the dialogue would stand out from the question “What is the human being?” And concentrate on the more specific topic caused by the Kant interpretation of his interlocutor was intended. The around 200 listeners in the fully occupied conversation room of the Grand Hotel Belvédère thus finally witnessed the debate about the finiteness of existence, which Heidegger had placed at the center, and the possibility of overcoming it.

opening

In the minutes of Bollnow / Ritter and Weiss / Mörchen the opening of the disputation is one of the clearly different versions. In the following, both versions are outlined, starting with that of Bollnow and Ritter. The versions are not necessarily mutually exclusive, but can complement each other.

- Version 1

Due to Heidegger's critical lectures against Neo-Kantianism, Cassirer opened the dispute with a question about the understanding of this term, doubted that there were any Neo-Kantians at all and added: "Who is the opponent to whom Heidegger turned?" Apparently emotional, Although he refused that there was any point in speaking of Neo-Kantianism - which was merely the “scapegoat” of modern philosophy, whereby the “existing Neo-Kantian” was missing - Heidegger then didn't quite logically call himself a Neo-Kantian.

- Version 2

Four points were up for debate: Heideggers-Kant interpretation and Cassirer's criticism of “the role” of spatiality, language and death in Heidegger. Following this, Cassirer asked Heidegger: "What is Neo-Kantianism?"

- Questions from Arthur Stein

While Arthur Stein's questions are missing from Bollnow / Ritter (in the Heidegger Complete Edition), Weiss and Mörchen (in the Cassirer estate edition) are largely identical in content. Accordingly, Stein asked some questions about Heidegger's interpretations of Kant, namely about the “imagination as the root of intuition and understanding” and the differences in this regard compared to the 2nd edition of the Critique of Pure Reason , in which “parallel with the receding of the imagination, an emergence of the more practical pathos ”.

Heidegger's first replica

The opening gave Heidegger the opportunity to fully define Neo-Kantianism in its own right and to criticize it as a mere epistemology of the natural sciences that is neither metaphysics nor ontology. To address Cassirer flat doubts about the justification of the concept of neo-Kantian and the rhetorical question of "enemies", Heidegger was one of first the name of the founder of the neo-Kantian schools, next to Hermann Cohen and Wilhelm Windelband and his former teacher Heinrich Rickert , then to set his view of Kantian philosophy against these doctrines, especially the Marburg School, from which Cassirer came: “I understand by neo-Kantianism the conception of the Critique of Pure Reason, which explains the part of pure reason that leads to the transcendental dialectic as Theory of knowledge with reference to natural science. ”On the other hand, he now objected:“ Kant did not want to give a theory of natural science, but wanted to show the problems of metaphysics, namely of ontology. ”

Possibility of transcendence: Cassirer on "Finiteness and Schematism"

In his reply, Cassirer first made a pledge of loyalty to Cohen, but then restricted the fact that although he had recognized the “position of mathematical natural science”, it could and “only stand as a paradigm”, not “as the whole of the problem” extended this statement to Paul Natorp , evidently with a view to the primacy of logic . At this point, however, he tries for the first time to make the dialogue less controversial and more constructive by referring, again and unspokenly, to Heidegger's lectures, to an agreement “between us”, namely, “that the productive imagination In fact, it seems to me to be of central importance for Kant ”, since the phenomenon of symbolic forms cannot be solved“ without tracing it back to the faculty of the productive imagination ”.

- Freedom and mundus intelligibilis

But how much Cassirer's admission of the “monism of imagination” of Heidegger's Kant interpretation and the inherent finitude of human beings was predetermined is revealed by his abruptly asked question about the “freedom problem” in Kant, which obviously could only be intended for this to be opposed to that postulate of finitude. The problem of freedom, according to Cassirer in Davos, “is the transition to the mundus intelligibilis. This applies to the ethical, and in the ethical a point is reached which is no longer relative to the finitude of the knowing being, but an absolute is now posited there. (...) And that ties in with Heidegger's remarks. One cannot overestimate the extraordinary importance of schematism. At this point the greatest misunderstandings in Kant's interpretation have occurred. But in the ethical he forbids schematism. Because he says: Our concepts of freedom etc. are insights (not knowledge) that can no longer be schematized. There is a schematic of theoretical knowledge, but not of practical reason. "

With this, Cassirer aimed at the core of Heidegger's Kant lectures. Even if in Davos the tendency towards “Mirandolian tolerance” may have prevailed, the objection coincides with what he put in sharper terms in a criticism of Heidegger's Kant book in 1931, concerning schematism as a temporal rule of the imagination. The undertaking of thinking of existence solely in terms of temporality required that only what can be schematized apply to Kant: “While Heidegger tries to relate all the 'faculties' of knowledge to the 'transcendental imagination', and even try to trace them back to it, he stays with him thus only a single reference level, the level of temporal existence. The difference between 'Phenomena' and 'Noumena' blurs and levels itself out: for all being now belongs to the dimension of time, and thus to finitude. But this removes one of the cornerstones on which Kant's entire conceptual structure rests and without which it must collapse. Kant nowhere advocates such a 'monism' of the imagination, but rather insists on a resolute and radical dualism, on the dualism of the sensible and the intelligible world. Because his problem is not the problem of 'being' and 'time', but the problem of 'being' and 'ought', of 'experience' and 'idea'. "

In this sense, Davos follows Cassirer's question as to how it is possible that the human being limited by the conditions a prori produces "eternal truths" in mathematics and in the field of ethics and whether this transcendence beyond the limits of Heidegger is denied that knowledge, reason and truth rather see “relative to existence”, so that a “finite being (...) cannot possess such truths at all”: “Heidegger wants this whole objectivity, this form of To renounce the absoluteness that Kant advocated in the ethical, theoretical and criticism of judgment? Does he want to withdraw entirely to the finite being, or, if not, where is the breakthrough to this sphere for him? I ask that because I really don't know. "

Heidegger on the unity of being and nothing

Heidegger's seven-page answer focused on this concept of transcendence as the possibility of crossing over into an intelligible world, which he did not even deny: "That something is present in the law that goes beyond sensuality cannot be denied." Ontological question about the finitude or infinity of existence, this possibility of transcendence is just another “index of finitude”, which Heidegger then discussed using the Kantian ethics, temporality and the existentiality of fear in the philosophy of being.

- Finiteness of ethics

Cassirer's objection that “finitude becomes transcendent in ethical writings” was initially accepted by Heidegger by confirming: “There is something in the categorical imperative that goes beyond finite essence”, but he immediately withdrew this admission: “But straight the concept of the imperative as such shows the reference to a finite being. This going out to something higher is always just going out to finite beings, to something created (angels). This transcendence also remains within creatureliness and finitude. ”In order to prove this and, at the same time, the“ finiteness of ethics ”, Heidegger referred to Kant's word“ the self-holder of reason ”, which“ is purely on itself and does not flee can escape into an eternal, absolute, but also cannot flee into the world of things. ”With this Kantian formulation it could then be concluded that the essence of the ought is such an“ in between ”.

- Transcendence of temporality

In the second of Cassirer's arguments for freedom and transcendence, the “eternal truths” of mathematics, his young challenger was able to celebrate the “piety of thought” held against “philosophy scholarship”, by asking questions to keep doubts about such certainties alive: “I ask the counter-question: What does eternal actually mean here? ”Heidegger immediately added epistemological and ontological questions to the initially seemingly all too common skepticism about the possibility of defining an endless time:“ How do we know about this eternity? Isn't this eternity just constancy in the sense of time? Isn't this eternity just what is possible on the basis of an inner transcendence of time itself? ”With this, the author of Being and Time was able to comfortably withdraw to the area of his main work at the time and the conception of the“ horizon of whole temporality ”to repeat. The titles of transcendental metaphysics, which refer to eternity, are "only possible because there is an inner transcendence in the essence of time (...) that time itself has a horizontal character". Accordingly, it is necessary to "emphasize the temporality of existence".

- Fear of nothing

For Heidegger, thinking about existence in terms of temporality initially coincides with the “analysis of death”, and this “has the function of highlighting the radical futility of existence in one direction, but not of overriding a final and metaphysical thesis as a whole the essence of death ”. Correspondingly, it is an “analysis of fear” with the aim of “preparing the question: On the basis of which metaphysical sense of existence itself is it possible that a person can be confronted with something like nothing at all?” The idea of nothing is based on fear, and only in the “unity of understanding of being and nothing” can it be made clear that people must also ask why. Nonetheless, Heidegger admits at this point that "if one takes this analytics of existence in 'Being and Time' (...), so to speak, and then asks the question of how (...) the understanding of the design of culture (...) should be possible ( …), It is an absolute impossibility (…) to say something ”. But since temporality and the finiteness it establishes only enable the analysis of existence, Cassirer's approach of a “cultural philosophy” - thereby also the possibility of the intelligible world through the mediation of symbolic forms - nevertheless only has a metaphysical function if it is “of becomes visible from the outset and not afterwards in the metaphysics of Dasein itself as a basic event. "

Caesura: three questions for Cassirer

Heidegger's reply with the open question of the possibility of the intelligible world, which would have to arise from a unity of understanding being and nothing, is abruptly interrupted in the protocol by three questions from a philosophy student who cannot be determined. As explicitly noted in the minutes, the three questions were only addressed to Cassirer and only answered by him.

"Question from the student in Davos] The questions of a stud. phil. S. (not determined) to Cassirer (...). The authorship of these questions is only available in the version of the discussion minutes distributed to the participants (...) (printed in Guido Schneeberger [...] p. 21) "

The unknown student asked about the access to infinity, the determination of infinity compared to finitude and the abandonment of philosophy in relation to fear.

- Cassirer's idealism

- Infinity through form

Until then, Cassirer had hardly had the opportunity to contribute his philosophical work - the “concept of symbol” had only been mentioned once in the context of the Kantian imagination. The question to Cassirer as to which “man has a path to infinity” could hardly be understood otherwise than as an invitation to reinforce the symbolic activity of man, i.e. “the function of form”, as a topic in the dispute, and the professor from Hamburg routinely reported that "man, by transforming his existence into form (...) grows out of finitude", because although he "does not make the leap (...) from his own finitude to a realistic infinity" because the metabase is possible, “which leads him from the immediacy of his existence into the region of pure form. And it only possesses its infinity in this form. "

- Cassirer

- Philosophy against "the fear of the earthly"

After a short, academic answer to the definition of infinity as an independent and not merely privative concept, the question of the task of philosophy seemed appropriate to address the interior of the Cassirer ideal of a humanism of freedom through pure form and almost “a kind of creed "To submit:" Philosophy has to let man become free as far as he can become free. (...) I want the meaning, the goal, to be in fact liberation in this sense: 'Throw away the fear of the earthly!' ”With this proclamation of the“ position of idealism ”, in which philosophy“ in a certain sense radically free from fear as a mere state of mind ”, Cassirer obviously positioned himself in an accurate contrast to the existential philosophy of worry and fear, which soon became explicit.

Limits of understanding

- Intermezzo by Hendrik Pos

As far as the minutes are correct, Hendrik Pos, as the moderator of the dialogue, only intervened once in the debate: as a linguist, he doubted that the use of the same terms "can be translated into the language of the other", but was convinced that that it was about “getting something in common out of these two languages”, which, as it later turned out, was not entirely shared by Heidegger. Pos now cited Heidegger's terms as examples: “Dasein, Das sein, the ontic”. Then “the expressions of Cassirer: the functional in the spirit and the transformation of the original space into another”, which obviously meant the metabase for the intelligible world through symbolic forms. Pos: "If it were found that there is no translation for this Terrmini from either side, then it would be the terms in which the spirit of Cassirer's and Heidegger's philosophy differ."

- Heidegger

- the untranslatable of thrownness

First, Heidegger went back to the previous topic, this time describing Cassirer's philosophical thoughts as afterwards compared to his own ontological approach: “Cassirer's terminus a quo is completely problematic. My position is reversed: The terminus a quo is my central problem, which I develop. ”The origins remained ambiguous with Cassirer, while Heidegger's philosophy is dedicated to precisely these, whereby the possibility of development down to the symbolic forms is difficult for him : “The question is: Is the terminus ad quem so clear for me?” Referring again to Kant, whose critical thought has urged Kant himself to “turn the real ground into an abyss”, Heidegger now explained his concept of Dasein as one without the sure ground of the logos, as one of the “thrownness”, which is why it is necessary to see the meaning in the “basic character of philosophizing” and to “become free for the finiteness of existence” in order to “get into the conflict, which lies in the essence of freedom. ”As a result, the concept of Dasein is incompatible with that of Cassirer, it cannot even be translated“ with a Cassirer concept ”. Dasein is not just consciousness, but relates to “the human being who is in a sense tied up in a body and, while being tied up in the body, stands in its own bond with beings (...), in the sense that existence, in the midst of beings thrown when free brings about an intrusion into being, which is always historical and in a final sense accidental. "

- Heidegger

- The nothingness of existence

Heidegger added to the definition of Dasein, described today as “existentialist pathos”, and the assertion that it was untranslatable for Cassirer's terms, that he had “deliberately emphasized” these differences, because: “It is not useful for objective work to when we come to a leveling. ”Accordingly, he refused that the Kantian question of what man was could be answered with an anthropology. Rather, it only makes sense that philosophy "has to lead man back beyond himself and into the whole of beings in order to make the nullity of his existence evident to him with all his freedom (...) and that philosophy has the task of from the lazy aspect of a person who only uses the works of the spirit, to a certain extent throwing the person back into the hardship of his fate. "

final

- Cassirer

- Bridge of Mediation

Despite Heidegger's repeated indications that understanding in the debate was neither possible nor desirable, Cassirer tried again in his last speech to highlight the possibility of joint thinking as the deeper meaning of the disputation. Although he agreed that he too was “against a leveling out”, the aim should be that “everyone, while remaining on his own point of view, sees not only himself but also the other”, for which Cassirer relies on the “ Idea of philosophical knowledge ”,“ which Heidegger will also recognize. ”But since in this position, in which“ it has already become clearer ”,“ what the contradiction consists ”,“ little can be done ”by“ mere logical arguments ”, both disputants should “Looking again for the common center in the contrast. Because we have this center because there is a common objective human world in which the difference between the individuals is by no means eliminated, but with the condition that the bridge from individual to individual has been built here. "

Finally, Cassirer dresses in metaphorical words the appeal to jointly see the “unity above the infinity of the different ways of speaking”, and consequently the “objective spirit” as the “common ground” that can be reached through communication: “From existence he spins Thread which, through the medium of such an objective spirit, connects us with another existence. (…) There is this fact. If that didn't exist, then I would not see how there could be such a thing as an understanding of oneself. "After a somewhat sudden excursus on the object-constituting character of the Critique of Pure Reason , Cassirer cites the question of" the possibility of this "as a résumé of his thought Fact of language ", where he again uses the term Dasein in its true sense, as a synonym for" Individual ":" How is it, how is it conceivable that we can communicate from Dasein to Dasein in this medium? " when this question is asked, Heidegger's question of being can be accessed.

- Heidegger

- Will to dissent

The rejection of the “bridge from individual to individual” became the key message of Heiddegger's final remark: “The mere mediation will never be productive.” Because since philosophy “focuses on the whole and highest of man, finitude must be found in philosophy show in a very radical way. ”After this rejection of the repeatedly uttered Cassirer offer, Heidegger addressed the audience in the conversation room of the Belvédère for the first time:“ And I would like to point out that what you see here to a small extent, the difference between philosophizing people in the unity of the problematic, that on a large scale it is expressed quite differently ", whereby it is essential" in dealing with the history of philosophy "to" free oneself from the difference of positions and viewpoints. "

epilogue

In Recollections of Ernst Cassirer from 1958, Hendrik Pos reports that Heidegger refused to shake hands with Cassirer after the disputation, which, however, was not confirmed by any of the numerous viewers and was never claimed by Cassirer. Since there was a third meeting of the two philosophers - after Hamburg and Davos - on the occasion of a visit by Cassirer to Freiburg in 1932, when Heidegger appeared to his counterpart "very open-minded and directly friendly", Pos's remark is very doubtful .

A second possible incident of the debate, the historical factuality of which is controversial, was reported by the Heidegger critic Guido Schneeberger: “In the course of the discussions, a man marked by severe nerve damage, which he suffered as a soldier in the World War, stood up and declared, In the 20th century, philosophy had only one task: to prevent war. To which Heidegger mockingly and contemptuously replied that this age could only be passed with severity. In any case, he himself returned from the war in good health. "

At the end of the minutes of Mörchen and Weiss, the heading "Evenings:" is included, but one of them is followed by a horizontal line across the entire page, the other breaks off. However, the Frankfurter Zeitung of April 22, 1929 speaks of the "dialogue" that "was brought to an end in the evening". However, there is no direct evidence of this continuation or even of its content.

About a month after Davos, Heidegger wrote to R. Bultmann that “nothing came of it” for him: “However, the experience is valuable to see how easy it is for people like Cassirer to have an argument.” But he did to the curator of the Frankfurt University "made some nice full blasts" and "life up there was only bearable in this form." Shortly after returning from Davos, he wrote to Elisabeth Blochman that the disputation there was "extremely elegant and almost too binding" "which prevented the problems from being given the necessary sharpness in the formulation."

Cassirer, on the other hand, thanked Heidegger at the end of all the lectures "for the enrichment that I have gained from the factual discussion (...)". The day after the dispute, he joined the students on a trip to Sils-Maria to visit the Nietzsche House , while Heidegger stayed to himself.

Satirical end to college courses

At the end of the university days, more than a week after the disputation, the professors were caricatured by the students in a final review, “following the example of satirical ideas at the Ecole Normale Supérieure”. The satire thus did not only refer to the two disputants: “It was everyone's turn. Nobody was spared. ”The imitator von Brunschvicg gave pacifist speeches, wore a blue-white-red ribbon around his head and assured him:“ My brain is not tricolor! ”Heidegger was portrayed by Bollnow, and Levinas“ had a lush black one at the time A head of hair and you dusted your head with powder ”, so that he could be recognized as a Cassirer, and the lime represented in this way trickled out of his hair and pockets. While Bollnow / Heidegger exclaimed: “Interpretari means to turn a thing on its head”, Levinas / Cassirer repeated: “Humboldt - culture. Humboldt - Culture ”and:“ I am in a conciliatory mood! ”Apparently the interpretation was bitterly angry - the“ innate gray-hairedness of all mere erudition, about which the youthful Friedrich Nietzsche complained, seemed to the younger generation embodied in the object of their satirical attack ” B. Recki, editor of Cassirer's works. For Emmanuel Levinas, who was also Jewish, the satire, which was presented unsuspectingly in retrospect, i.e. knowing the later events, was a “painful memory”, fueled by the fact that Toni Cassirer, the caricatured’s wife, resented it personally in her memories that “he in Davos had shown how much he preferred Heidegger Cassirer and that he had played that role in a carefree, carefree performance that ignored the looming dangers. "

Disputation to Davos

Immediately after completing the second Davos university course, Heidegger set to work to address his lectures on Kant as “an attempted introduction to the questionable nature of the question of being set out in 'Being and Time' in a dubious detour” formulate, with the result of the publication Kant, which appeared in the same year, and the problem of metaphysics , the so-called Kant book by Heidegger . This became the basis for continuing the disputation held in Davos in writing, whereby Cassirer's advice disappeared in the review of the book: “Kant is and remains - in the most sublime and beautiful sense of this word - a thinker of the Enlightenment: he strives for the light and brightness, even where he ponders the deepest and most hidden 'reasons' of being. (...) Heidegger's philosophy, on the other hand, has been based on a different stylistic principle from the start. "

Cassirer objects that Heidegger's interpretation of a “receptive spontaneity”, a “sensual reason”, is a “wooden iron”, since the receptive with Kant can only be the sensual, the spontaneous but the productivity of reason. Heidegger therefore speaks "no longer as a commentator but as a usurper who breaks into the Kantian system with armed force, so to speak, to subjugate it and to make it subservient to its problems." In Kant's teaching, Heidegger remains a "stranger and an intruder." Cassirer “demanded a restitutio in integram of the Kantian philosophy (...). The review speaks a language unusual for Cassirer, because Heidegger made things controversial in Cassirer's eyes by distorting them ”.

Heidegger did not respond, or at least not publicly, to this late attack by Cassirer. Only in his estate was an envelope with the handwritten inscription: “Odebrecht and Cassirer's Critique of the Kant Book.” As part of the “Inlays of the hand copy of the first edition of the Kant book (...)”. (...) Problem of finitude in general. “In the envelope there were Heidegger's reactions to the two reviews in the form of notes, which were only printed in 1990, long after his death, in the appendix to the Kantbuch (GA 3). There it says: “Cassirer hangs on the letter and just overlooks the problems of pure intellect and logic.” And: “Only philosophizing about finitude because for one or the other it might appear at the moment of a whimper, is it? no philosophical motivation. It looks like Cassirer has the central theme and yet completely missed it! "

In The Myth of the State , also published posthumously, Cassirer accused Heidegger of foregoing timeless truths: “He does not admit that there is anything like an 'eternal' truth, a platonic 'realm of ideas' or a strictly logical method of philosophical thinking. (...) A philosophy of history, which consists in gloomy prophecies about the decline and the inevitable destruction of our civilization, and a theory which sees man's thrownness as one of his main character traits, all have hopes of an active part in building and rebuilding cultural life abandoned by man. Such a philosophy renounces its own fundamental and ethical ideals. "(MS, 383 f.)

reception

First reactions

- Press reports

The Davos disputation was reflected in the press through the report by Kurt Riezler , who was among the audience , through Ernst Howald's reflections and Hermann Herrigel's quotations from the minutes that appeared in a supplement to the Frankfurter Zeitung , and Franz Rosenzweig, who lived in Frankfurt, gave rise to the essay There were reversed fronts (see below). A few days after the disputation, Riezler justified the obvious interpretation of the dialogue, still continued by Rüdiger Safranski , as the meeting of the philosophers on the “Magic Mountain” (see below). Herrigel, on the other hand, gave a description of the two disputants that is often quoted to this day: "Instead of seeing two worlds collide, at most one enjoyed the spectacle, like a very nice person and a very violent person who also tried terribly to be nice, Monologues spoke. Nevertheless, everyone in the audience was very moved and made each other happy to have been there. "

- Franz Rosenzweig's "Reversed Fronts"

In a reaction to the Davos disputation that is as famous as it is controversial in specialist circles - or only to its description by Hermann Herrigel in the supplement of the Frankfurter Zeitung - the terminally ill Franz Rosenzweig saw in Heidegger's position a parallel to the late work of Hermann Cohen, the founder of Neo-Kantianism . "Reversed fronts", so the title of Rosenzweig's posthumously published essay, were therefore expressed in Davos. Because, "if Heidegger against Cassirer gives philosophy the task of revealing to man (...) his own 'nothingness in spite of all freedom'", what else is it "than that passionate representation of the 'individual qua même'" against the learned idea of a cultural-philosophical primacy, which Rosenzweig regarded as the “source” of the knowledge of the “last Cohen”. The interpretation of Heidegger's argument based only on the newspaper report, as has been shown, as equivalent to that of the "late Cohen" of the religion of reason from the sources of Judaism , which Rosenzweig specifically discusses at the beginning of the essay, is usually viewed rather critically .

- Ask about victory and defeat

Although unusual for philosophical discussions, the question of the loser and the winner of the debate immediately became one of the subjects of reception. Like Rosenzweig in Vertexte Fronten and Levinas in the parody, most of the younger generation were touched by Heidegger's revolutionary pathos: “But you have to know that the students, enthusiastic about a gorgeous teacher, the one in asymmetrically cut jackets, occasionally even turned up in the ski dress at the university, were not interested in the historicist ideal of objectivity: Turning one thing on its head in all radicality was precisely the sensational thing that you can do with the thirst for adventure of the interwar generation and with the dismissive gesture of Spengler's downfall longed. "

Even with Heidegger's repeated express rejection of the possibility of an understanding, the dialogue appeared to be necessarily pointed towards the question of which side was to be agreed with. “In the minutes of the discussion it becomes clear that Cassirer was ready to accept the irreconcilable differences of opinion, whereas Heidegger was aiming for a final victory. Cassirer's assumption of a multiplicity of symbolic forms (...) probably made him more inclined to accept differing opinions. Heidegger, on the other hand, resolutely stepping back behind the manifold structures of being, could not afford to be so 'ecumenical'. (...) There was general agreement that Heidegger had gained the upper hand in Davos. "

Worrying silence

Between 1929 and 1973 there could hardly be any talk of a reception of the Davos Disputation , because first the Great Depression followed, and soon after his exile in the spring of 1933, Ernst Cassirer was practically forgotten by German philosophy. "It would not have occurred to anyone that the Davos files had a titanic battle waiting to be dealt with." The text of the debate was first published in 1960 by Guido Schneeberger in the additions to a Heidegger bibliography , in a shortened version and self-published, because he did not receive the rights: “The present booklet will not reach the book trade. Copies can be obtained from me ”, with a private address in Switzerland. The response remained correspondingly low. Only in the fourth edition of the so-called Kant book by Heidegger (GA 3), published in 1973, was the entire protocol of the Davos disputation printed in the appendix .

Two kinds of memories

Otto Friedrich Bollnow, the Heidegger of the parody, had the “uplifting feeling of having attended a historical hour, very much as Goethe had addressed in the 'Campaign in France': 'A new epoch in world history is starting here and today '- in this case the history of philosophy -' and you can say you were there! '”In contrast, one of the student participants in the French group, the later philosophy professor Maurice de Gandillac , remembered a far more relaxed experience:“ You have to know that we were by no means aware of a historical moment. We only had the feeling that we were on familiar territory with Cassirer, while Heidegger aroused considerable curiosity. "

Magic mountain motif

The comparison, justified by Kurt Riezler in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung , between the Davos disputation and the dialogues in the novel The Magic Mountain was often included in the most recent reception. So Peter E. Gordon saw in Cassirer the "embodiment of Settembrini", and Dominic Kaegi did not want to leave out the "obvious Davos association" of the dispute between Settembrini and Naphta in the magic mountain and noticed that Thomas Mann's "ironic reminiscence of one in their ideals irrevocably bygone epoch “ find a correspondence on the subject of the authenticity of existence in being and time . Finally, the literary scholar Rüdiger Safranski took the Thomas Mann Prize as an opportunity to deepen the comparison in his acceptance speech on December 7, 2014. In an obvious analogy, he introduced the two disputants from the Zauberberg : “Settembrini, this proud son of the Enlightenment, a free spirit, humanist of infinite eloquence, a person of intellectual progress; and Naphta, the astute Jesuit with the gloomy image of man, Grand Inquisitor of the Spirit, who understands the abysmal irrational and wants to bring people to self-reflection through horror. "

When Safranski “read the minutes of the spectacular debate between Cassirer and Heidegger” it seemed to him “as if Settembrini and Naphta had passed from the novel into reality.” The familiar pattern of interpretation was now repeated, with Cassirer taking on Settembrini's role as usual and Heidegger that of naphtha. The comparison, since the dialogues of the magic mountain were conducted at the time of the European empires before the First World War , has its limits, which are, however, leveled in Safranski's acceptance speech: “Both times, in the novel as in reality, this debate ends at the end the Weimar Republic on the fateful question of whether the conciliatory spirit of democracy can assert itself against an existentialist extremism that is looking forward to a fundamental revolution, whether from the left or the right. "

In the shadow of the future

In retrospect, the Davos disputation was interpreted in the light of the historical and biographical events that followed the meeting: after the National Socialists came to power, Cassirer and his wife Toni traveled from Hamburg's Dammtorbahnhof to Italy on March 12, 1933, and later to Vienna and in autumn from from there to Oxford, where he accepted a visiting professorship for two years. According to the Law for the Restoration of the Civil Service (BBG), Cassirer was retired on July 27, 1933 with effect from November 1, 1933 due to his Jewish origin. From 1935 to 1940 he taught in Gothenburg, then in New York, where he died in 1945. Heidegger, on the other hand, became the new rector of the University of Freiburg in April 1933, gave an inaugural speech based on the principle of the Führer principle the following month, and also joined the NSDAP in May 1933, which formally began Heidegger's path into National Socialism .

However, it is incorrect that at the time of the meeting in Davos Cassirer was "the first Jewish rector of a German university" - as R. Safranski says, similarly to Levinas biographer Salomon Malka - and Heidegger's alleged that M. de Gandillac also said it Commitment to the National Socialists as early as the spring of 1929 cannot be proven and is therefore questionable.

But the fact that "Cassirer's and Heidegger's paths also parted biographically, Cassirer became a refugee, while Heidegger's concern was with the self-assertion of the German university, does not leave 'a look back at the Davos events untouched." The quote that people have to be thrown back into the hardship of their fate, as it were, is rated as “fascist” in the “tone”, “whereby Heidegger is often portrayed as a dangerous provincial, who, with his ruthlessness and demonstrative radicalism, is already the future Nazi director of Freiburg University recommends. ”However, S. Malka's question - with a view to the final review - opposes retrospective evaluations with the view of a chronologically undistorted interpretation:“ Who could have foreseen at that time, with the harmless jokes on the slopes above Lake Davos, that Ernst Cassirer took over the rectorate just four years later resign in Hamburg and go into exile in Sweden, but his interlocutor would take over the Freiburg rectorate and give a submissive speech in favor of the power of the Nazis? "

expenditure

- Ernst Cassirer: Left Manuscripts and Texts (ECN), Volume 17. Davos Lectures. Lectures about Hermann Cohen. Edited by Jörn Bohr and Klaus-Christian Köhnke. Hamburg 2004, “Arbeitsgemeinschaft Cassirer - Heidegger”, pp. 108–119.

- Martin Heidegger Complete Edition (HGA) 3, Frankfurt / M., 1973, “Davos Disputation between Ernst Cassirer and Martin Heidegger”, pp. 274–296.

- Guido Schneeberger: Supplements to a Heidegger bibliography. Bern 1960, “Arbeitsgemeinschaft Cassirer - Heidegger”, pp. 17–27.

literature

- P. Gemeinhardt u. a. (Ed.): Culture and science during the transition into the "Third Reich". Marburg 2000, philosophers on the magic mountain. Reflections on the philosophical debate between Ernst Cassirer and Martin Heidegger in Davos 1929 , pp. 133–143.

- K. Founder: Cassirer and Heidegger in Davos 1929. in: H.-J. Braun, H. Holzhey, EW Orth (ed.): About Ernst Cassirer's philosophy of symbolic forms. Frankfurt am Main, 1989.

- Peter E. Gordon: Continental Divide: Heidegger, Cassirer, Davos. Cambridge, Mass. 2010.

- Dieter Thomä (ed.): Heidegger manual. Life - work - effect. Stuttgart 2003, pp. 110–115: The Davos disputation between Ernst Cassirer and Martin Heidegger. Controversial transcends.

- Pierre Aubenque , Luc Ferry , Enno Rudolph, Jean François Courtine e Fabien Cappeillières: Philosophy and Politics. The Davos disputation between Ernst Cassirer and Martin Heidegger in the retrospective. In: International Journal of Philosophy, 1, 2 (1992).

- P. Gemeinhardt (Ed.): Culture and science during the transition into the "Third Reich". Marburg, 2000, pp. 133-143: Philosophers on the Magic Mountain. Reflections on the philosophical debate between Ernst Cassirer and Martin Heidegger in Davos. 1929.

- Dominic Kaegi: The Legend of Davos. In: Hannah Arendt, Hidden Tradition - Untimely Actuality? Berlin 2007, pp. 75-86.

- Dominic Kaegi, Enno Rudolph (eds.): Cassirer - Heidegger: 70 years of the Davos disputation. Hamburg 2002.

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ Ernst Cassirer: Postponed manuscripts and texts. (ECN), Volume 17, Davos Lectures. Lectures on Hermann Cohen, ed. by Jörn Bohr and Klaus-Christian Köhnke. Hamburg 2014, “Arbeitsgemeinschaft Cassirer - Heidegger”, p. 108

- ^ Salomon Malka: Emmanuel Lévinas: a biography. 2004, p. 60

- ↑ The sociologist Gottfried Salomon-Delatour and the theologian Eberhard Grisebach announced the Cassirer / Heidegger meeting in letters to colleagues as an attraction, cf. Thomas Meyer: The Mythenberg of Davos. In: Journal for the History of Ideas, Volume VIII, Issue 2, 2014, pp. 109–112.

- ↑ Martin Heidegger Complete Edition (HGA) 3, Frankfurt am Main 1973, “Davos Disputation between Ernst Cassirer and Martin Heidegger”, pp. 274–296

- ↑ Ernst Cassirer: Postponed manuscripts and texts. (ECN), Volume 17, Davos Lectures. Lectures on Hermann Cohen, ed. by Jörn Bohr and Klaus-Christian Köhnke. Hamburg 2014, “Arbeitsgemeinschaft Cassirer - Heidegger”, pp. 108–119.

- ↑ Guido Schneeberger: Supplements to a Heidegger bibliography. Bern 1960, “Arbeitsgemeinschaft Cassirer - Heidegger”, pp. 17–27.

- ^ Salomon Malka: Emmanuel Lévinas: a biography. 2004, p. 58 f.

- ↑ cit. n. Katja Bruns: Anthropology between theology and natural science with Paul Tillich and Kurt Goldstein. Göttingen 2011, p. 9, note 8.

- ^ Peter E. Gordon: Continental Divide. 2010, p. 93.

- ↑ Katja Bruns: Anthropology between theology and natural science with Paul Tillich and Kurt Goldstein. Göttingen 2011, p. 100.

- ↑ The photograph by Cassirer and Heidegger in Davos, like the literary estate of Joachim Ritter, was acquired from the German Literature Archive in Marbach (file number: D20130228-004) and is printed on the cover of Peter E. Gordon's Continental Divide .

- ↑ The spelling differs from that of the Levinas biographer Salomon Malka, who is occasionally quoted here: Levinas writes his name in Hebrew without an accent. Ludwig Wenzler, among others, joins this in his edition of Humanism of the Other Man , cf. the justification p. XXIX; also Thomas Freyer, Richard Schenk (ed.): Emmanuel Levinas - Questions to the Modern Age. Vienna 1996; Ulrich Dickmann: Subjectivity as responsibility: the ambivalence of the human in Emmanuel Levinas and its significance for theological anthropology. Tübingen / Basel 1999; Adriaan Peperzak: Some remarks on the relationship between Levinas and Heidegger. In: Annemarie Gethmann-Siefert (ed.): Philosophy and poetry: Otto Pöggeler for his 60th birthday. “Although Levinas, who comes from Lithuania, has taken on French nationality, his name is spelled without an accent. In many German comments, however, he is wrongly French. "

- ↑ see the list of participants: Peter E. Gordon: Continental Divide. 2010, pp. 94-100; Dominic Kaegi: The Legend of Davos. In: Hannah Arendt, Hidden Tradition - Untimely Actuality? Pp. 75–86, here p. 75, note 4; Salomon Malka: Emmanuel Lévinas: a biography. 2004, p. 59.

- ^ "Davos lectures" (DV), HGA 3, p. 271.

- ↑ ECN 17, p. 3; In HGA 3, p. XV, Heidegger wrote in 1973: “Cassirer had spoken in three lectures about philosophical anthropology, specifically about the problem of space, language and death”, but withholds Cassirer's addition: “About the problem ... afterwards to Heidegger. "(ECN 17, p. 12)

- ↑ ECN 17, p. 13

- ↑ ECN 17, p. 17.

- ↑ ECN 17, p. 24 f.

- ↑ ECN 17, p. 27, note c; HGA 2, Being and Time , p. 61

- ↑ HGA 2, Being and Time , p. 61 f.

- ↑ ECN 17, p. 28.

- ↑ ECN 17, p. 33.

- ↑ ECN 17, p. 71.

- ^ K. Founder: Cassirer and Heidegger in Davos 1929. In: H.-J. Braun, H. Holzhey, EW Orth (ed.): About Ernst Cassirer's philosophy of symbolic forms. Frankfurt am Main 1989, p. 293.

- ↑ Max Müller: Martin Heidegger - A philosopher and politics. A conversation with Bernd Martin and Gottfried Schramm. In: Günther Neske, Emil Kettering (Ed.): Answer. Martin Heidegger in conversation. Pfüllingen 1988, pp. 90-220; P. 193 f., About the winter semester 1928/29: “Heidegger and his students had a completely different style than the other professors. They went on excursions, hikes on foot and on skis together. There, of course, the relationship to nationality, to nature, but also to the youth movement was expressed. "

- ^ Salomon Malka: Emmanuel Lévinas: a biography. 2004, p. 63.

- ↑ Hans-Georg Gadamer, interview with contemporary witnesses by Patrick Conley , broadcast manuscript, broadcast on April 30, 1996, SFB 3.

- ↑ John Michael Krois: On the life picture of Ernst Cassirer (1874-1945). P. 8.

- ↑ Pierre Aubenque: Introduction to the Davos Protocols. quoted, n. Salomon Malka: Emmanuel Lévinas: a biography. 2004, p. 60.

- ↑ Being and Time , HGA 2, § 11, p. 51.

- ↑ K. Founder: Cassirer and Heidegger in Davos 1929. in: H.-J. Braun, H. Holzhey, EW Orth (ed.): About Ernst Cassirer's philosophy of symbolic forms. Frankfurt am Main 1989, p. 293.

- ↑ Ernst W. Orth: Kant Studies , Volume 106, Issue 3, 2015, p. 542.

- ↑ Thomas Meyer: Der Mythenberg von Davos. Journal for the history of ideas, ed. by Sonja Asal, Helwig Schmidt-Glintzer, Issue VIII / 2 Summer 2014: 1914.

- ↑ ECN 17, p. 384, note 326.

- ↑ ECN 17, p. 384, note 327.

- ↑ Thomas Meyer: Der Mythenberg von Davos. Journal for the history of ideas, ed. by Sonja Asal, Helwig Schmidt-Glintzer, Issue VIII / 2 Summer 2014: 1914.

- ↑ HGA 3, 274.

- ↑ ECN, 17, 108.

- ↑ ECN 17, 108 f.

- ↑ HGA 3, 275.

- ↑ HGA 3, 275, in the ECN there is no declaration of loyalty to Cohen, Cassirer's answer begins there with the establishment of agreement with Heidegger, cf. ECN 17, 112.

- ↑ derived from the philosopher Giovanni Pico della Mirandola : Birgit Recki: Ernst Cassirer, Goethe, Hamburg and what we have in a 'Hamburg edition'. Ernst Cassirer Arbeitsstelle, Recki ( Memento of the original dated December 6, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Cassirer: Kant and the problem of metaphysics. Comments on Martin Heidegger's interpretation of Kant. in: Kant Studies , 1931, Volume 36, Issue 1–2, pp. 1–26, here p. 16.

- ↑ DD, HGA 3, 277.

- ↑ DD, HGA 3, 278.

- ↑ DD, HGA 3, 280.

- ↑ DD, HGA 3, 279.

- ↑ HGA 7, p. 36.

- ↑ DD, HGA 3, 282.

- ↑ HGA 2, Being and Time , p. 365.

- ↑ DD, HGA 3, 283.

- ↑ DD, HGA 3, 283 f.

- ↑ DD, HGA 3, 285.

- ↑ cf. ECN 17, p. 378, note 283.

- ↑ DD, HGA 3, 286.

- ↑ DD, HGA 3, 286 f.

- ↑ DD, HGA 3, 287.

- ↑ DD, HGA 3, 288.

- ↑ DD, HGA 3, 288.

- ↑ DD, HGA 3, 289

- ↑ DD, HGA 3, 290.

- ^ Kurt Zeidler: On the Davos disputation between Ernst Cassirer and Martin Heidegger.

- ↑ DD, HGA 3, 291.

- ↑ DD, HGA 3, 292.

- ↑ DD, HGA 3, 295

- ↑ DD, HGA 3, 295 f.

- ↑ Hendrik Pos: Recollections of Ernst Cassirer. In: Paul Arthur Schilpp (ed.): The Philosophy of Ernst Cassirer. New York 1958, pp. 63-79, 69, and references therein. n. Dominic Kaegi: The legend of Davos. In: Hannah Arendt, Hidden Tradition - Untimely Actuality? Pp. 75–86, 76, note 8.

- ↑ Thomas Meyer: Der Mythenberg von Davos. In: Journal for the history of ideas. Edited by Sonja Asal, Helwig Schmidt-Glintzer. Issue VIII / 2 Summer 2014: 1914

- ↑ Dominic Kaegi: The Legend of Davos. In: Hannah Arendt, Hidden Tradition - Untimely Actuality? Pp. 75–86, here p. 76, note 8, letter to Toni Cassirer in: T. Cassirer: My life with Ernst Cassirer. Hildesheim 1981, p. 167.

- ↑ Guido Schneeberger: Review of Heidegger , 4: Quoted from Dominic Kaegi: Die Legende von Davos. In. Hannah Arendt, Hidden Tradition - Untimely Topicality? Pp. 75–86, here 83, note 46.

- ↑ ECN 17, p. 119.

- ↑ cit. n ECN 17, note 338.

- ^ M. Heidegger, letter to Rudolf Bultmann dated May 9, 1929, quoted in n. Dominic Kaegi: The legend of Davos. In: Hannah Arendt, Hidden Tradition - Untimely Actuality? Pp. 75–86, 76, note 5.

- ^ Letter of April 12, 1929, in: Martin Heidegger / Elisabeth Blochmann, Briefwechsel, 1918–1969. Edited by Joachim W. Storck. Marbach 1989, 29 f.

- ^ Thomas Meyer: Ernst Cassirer. Hamburg 2006, p. 168 f.

- ^ Salomon Malka, Emmanuel Lévinas. A biography , 2004, p. 64

- ^ Salomon Malka: Emmanuel Lévinas. A biography. 2004, p. 64.

- ↑ Birgit Recki: Battle of the Giants, The Davos Disputation 1929 between Ernst Cassirer and Martin Heidegger. Ernst Cassirer Arbeitsstelle, Davos ( Memento of the original dated December 6, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Salomon Malka: Emmanuel Lévinas. A biography. 2004, p. 65.

- ↑ HGA 3, p. XIV f.

- ^ Cassirer: Kant and the problem of metaphysics. Comments on Martin Heidegger's interpretation of Kant. In: Kant Studies , 1931, Volume 36, Issue 1–2, pp. 1–26; ECW 17, p. 247, cit. after John Michael Krois: Ernst Cassirer 1874–1975. A short biography. S. XXXII

- ^ Cassirer: Kant and the problem of metaphysics. Comments on Martin Heidegger's interpretation of Kant. In: Kant studies , Volume 36, Issue 1–2, pp. 1–26, here p. 17.

- ↑ John Michael Krois: On the life picture of Ernst Cassirers (1874–1945) ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , P. 8.

- ↑ HGA 3, p. 300.

- ↑ in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung , No. 609, March 30, 1929.

- ↑ Ernst Howald: Considerations on the Davos university courses. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung , April 10, 1929.

- ↑ Hermann Herrigel, April 22, 1929, Frankfurter Zeitung , supplement for universities and youth , "Thoughts of this time, faculties and nations meet in Davos"

- ↑ Reversed fronts. In: Der Morgen 8, (1930), pp. 85-87.

- ↑ Hassan Givsan: On Heidegger: an addendum to 'Heidegger - the thinking of inhumanity'. 2011, pp. 43–47.

- ↑ cf. Hassan Givsan: On Heidegger: a supplement to 'Heidegger - the thinking of inhumanity'. 2011, pp. 43-47; Hans Liebeschütz: From Georg Simmel to Franz Rosenzweig: Studies on Jewish thinking in the German cultural sector. 1970, pp. 170-173.

- ↑ Birgit Recki: Battle of the Giants, The Davos Disputation 1929 between Ernst Cassirer and Martin Heidegger. Ernst Cassirer Arbeitsstelle, Davos ( Memento of the original dated December 6, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ David Adams: Metaphors for Man. In: The development of the anthropological metaphorology of Hans Blumenberg, Cassirer and Heidegger in Davos. Germanica, 8, 2004, pp. 1–3, here p. 2.

- ↑ cf. Dominic Kaegi: The Legend of Davos. In: Hannah Arendt, Hidden Tradition - Untimely Actuality? Pp. 75–86, here p. 77 ff .: "Davos waiting"

- ^ Conversations in Davos. In: Memory of Martin Heidegger. Edited by Günther Neske. Pfullingen 1977, pp. 25–28, here p. 27.

- ^ Salomon Malka: Emmanuel Lévinas. A biography. 2004, p. 65.

- ↑ Peter Eli Gordon: Rosenzweig and Heidegger. 2003, p. 278.

- ↑ Dominic Kaegi: The Legend of Davos. In: Hannah Arendt, Hidden Tradition - Untimely Actuality? Pp. 75–86, here 83.

- ^ Rüdiger Safranski: Acceptance speech for the Thomas Mann Prize 2014. p. 2.

- ^ Rüdiger Safranski: Speech of thanks for the Thomas Mann Prize 2014. pp. 2–3

- ↑ Birgit Recki: A Philosophy of Freedom - Ernst Cassirer in Hamburg. In: Rainer Nicolaysen (ed.): The main building of the University of Hamburg as a place of memory. With seven portraits of scientists displaced during the Nazi era. Hamburg, 2001, pp. 57–80, here p. 59.

- ↑ John Michael Krois: On the life picture of Ernst Cassirer (1874-1945). P. 10.

- ↑ cf. Victor Farías: Heidegger and National Socialism. Frankfurt am Main p. 137.

- ↑ Bernd Martin: Martin Heidegger and the "Third Reich". Darmstadt 1989, p. 24.

- ^ Rüdiger Safranski: Acceptance speech for the Thomas Mann Prize 2014. p. 2.

- ^ Salomon Malka: Emmanuel Levinas: a biography. 2004, p. 60.

- ↑ Cassirer was only elected rector on July 6, 1929, cf. Birgit Recki: A Philosophy of Freedom - Ernst Cassirer in Hamburg. P. 59.

- ↑ Maurice de Gandillac, cit. n. Salomon Malka: Emmanuel Lévinas: a biography. 2004, p. 63: “In 1929 Davos was still a long way from the atmosphere that prevailed later in '32, '33, '35, with Kristallnacht and the first attacks on the synagogues. (...) Heidegger was already involved, mainly through his wife's mediation, but we didn't know that. ”[The“ Kristallnacht ”, i.e. the November pogroms, and the destruction of the synagogues did not take place until 1938.]

- ↑ Dominic Kaegi: The Legend of Davos. In: Hannah Arendt, Hidden Tradition - Untimely Actuality? Pp. 75-86, here p. 77, m. Quote v. Dieter Sturma: The Davos disputation between Ernst Cassirer and Martin Heidegger. Controversial transcendence. In: Dieter Thomä (ed.): Heidegger manual. Life - work - effect. Stuttgart 2003, pp. 110–115, here 114.

- ↑ Thomas Rentsch, Martin Heidegger - Das Sein und der Tod , Munich, 1989, 115.

- ^ O. Müller: German is European. In: Die Zeit , January 4, 2007

- ^ Salomon Malka: Emmanuel Lévinas: a biography. 2004, p. 60.