The sleep of reason gives birth to monsters

|

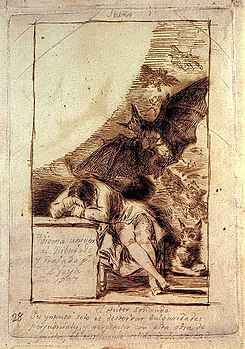

| El sueño de la razón produce monstruos |

|---|

| Francisco de Goya , around 1797–1799 |

| Aquatint etching |

| 21.6 x 15.2 cm |

| The plate is in the Museo de Calcografía Nacional , Madrid |

The sleep of reason gives birth to monsters (original title: El sueño de la razón produce monstruos ), more rarely The dream of reason gives birth to monsters , is a graphic work by the Spanish artist Francisco de Goya (1746–1828). It is the image of 43. 80 in the technique of aquatint executed etchings of Goya in 1799 published collection Los Caprichos ( whims, fancies ) and is among the most important and most interpreted graphic works of art history. It was originally planned as the title page of the collection and shows Goya sleeping at a kind of table, surrounded by eerie nocturnal creatures.

History, description and context

The sheet Capricho no. 43 shows the artist sunk in his sleep on a table-like, cubic body. Drawing implements and sheets of paper lie on the plate. Eerie, flying nocturnal animals and a cat-like creature, perhaps a lynx, appear behind him . A larger owls like creatures has his claws one of the pens grasped, it seems it rich to want and to speak to him. The lettering El sueño de la razón produce monstruos appears on the front of the table as the title element. Originally this work was also supposed to be the title of the Sueños collection of sheets , a forerunner of the Caprichos , an enlightening work directed against vice , prejudice and superstition. But Goya finally took the well-known, different, more realistic self-portrait as the final cover for the later series.

The Capricho 43 occupies a special position within the series. While the title is placed below on all other sheets, here it is part of the picture. It follows the last so-called donkey picture with the title Tu que no puedes ( You Who Ca n't, Cap. 42 ), the depiction of two peasants carrying arrogant donkeys on their backs, which are to be understood as a satire on the Spanish nobility and by is regarded by many interpreters as the most revolutionary sheet in the collection. Immediately after the cap. 43 follow some witch pictures , one of which, Holgan delgado ( They spin fine, Cap. 44 ) shows three witches with a bunch of dead children hanging over them. It is an allusion to midwives or angel makers who secretly abort and were therefore denounced as witches by the church.

interpretation

The title of the cap. 43 can be translated differently. The Spanish word sueño can be translated both as sleep and as dream . To this day, this provides an opportunity for an art-historical discussion about the interpretation and meaning of the image. The Enlightenment claim Goya of Tübingen art historian should accordingly believes Peter K. Klein , the word sueño with sleep to be translated. The view that the dream is meant, however, goes in an irrational, surrealistic and unconscious direction of Goya's intentions. This is common in the parlance of modernist research around the art historian Werner Hofmann , who sees Goya with his visions as a pioneer of modernity. According to this view, the eerie creatures depicted in the night are dream visions in an emblematic self-portrayal of the painter . The political scientist Wilhelm Hennis dealt with the historical and political context of the Caprichos, in which he considered Goya's complete works. For him, at the time of the conflict between Spain and revolutionary France, the question arises whether the absence of reason or the dream of perfect reason causes more harm , and he sees Cap. 43 as a dream of reason .

Contemporary commentary on Cap. 43 from Goya's intellectual environment speak of a fantasía abandonada de la razón , i.e. a fantasy about the absence of reason which these monsters produce (so-called Prado and Ayala commentary ). Another commentary appeared in 1811 ( Sánchez Gerona commentary ), which says something similar: En durmiéndose la razón, la todo es fantasía y visiones monstruosas ( when reason sleeps, everything turns into monstrous visions ). The Capricho 43 is therefore not a manifestation of the black arts, but, according to the art historian George Levitine, is to be understood as an enlightening warning of what threatens an artist if he is overwhelmed by his imagination . The specialist in Goya's graphics and curator Eleanor Axson Sayre sees it similarly: The viewer of the picture is asked not to sleep, but to be vigilant, because otherwise one can neither recognize nor fight the monsters of ignorance and vice .

Of those in the Cap. 43 next to the dark shadows depicted animals, the owl that hands the artist a pen has a special meaning. It is considered a symbol of wisdom. But owls, like bats, can also be understood as messengers of stupidity, ignorance and darkness in the so-called Spanish emblem literature of the 17th and 18th centuries . And when she hands the sleeping artist a quill, it is supposed to wake him up to artistic activity . A second owl, with its bright, spread wings, seems to protect the sleeping Goya from an approaching flock of bats, which in depictions since Albrecht Dürer's copperplate The Idler's Dream (around 1498) have been seen as messengers of the threatening.

Spanish art historian and Goya expert Manuela B. Mena Marquéz believes that the Cap. 43 to this day should be understood as a “Manifesto of European art and cultural history”, because it sums up what “defines the spirit of man and his abilities.” The paper has literary, philosophical and general cultural significance the ambiguous title (meaning the word sueño as sleep or dream ) "made the key to the consciousness of the rational-enlightened man of the modern age." The ambiguous title represents a linguistic ambivalence that Goya wanted, which intensifies in the picture, but does not is resolved. As a result, the image acquired a valid meaning that lasted through the 20th century with its dichotomy between feeling and reason. Mena Marquéz is making the cap. 43 on an equal footing with Michelangelo's Creation in the Sistine Chapel , Rembrandt's Night Watch , Las Meninas by Diego Velázquez and Albrecht Dürer's Melancholy .

Werner Hofmann recognizes in the Caprichos the expression of the dialectic of the Enlightenment . In it the artist exposes the conditions under which bondage occurs, whereby he has to conceal the multi-meaning of his pictures. For Goya and for Kant, the disease of reason, its hubris and delimitation lead to a world as a penitentiary, as a place of chastisement for fallen spirits, which is also reflected in other metaphors of the time such as B. in the work of William Blake expresses.

Preliminary studies

| Preparatory studies in the Museo del Prado , Madrid | |

| Bats, Human Faces, and Horses (1796–1797) | Inscription: Idioma universal. Dibujado y grabado por Francisco de Goya (1797) |

| 22.9 × 15.5 cm - Indian ink drawing | 24.8 × 17.2 cm - pen drawing |

In the Museo del Prado , Madrid, there are two designs for the cap. 43 , which are considered preliminary studies for the final etching. They are pen and ink drawings in sepia from 1797/98. In one of them is the writing: Idioma universal. Dibujado y grabado por Francisco de Goya. Año 1797 ( Universal Language. Drawn and engraved by Francisco de Goya. Year 1797 ) included, as well as outside below the words as a kind of explanation: El autor soñando. Su yntento solo es desterrar bulgaridades perjudiciales, y perpetuar con esta obra de caprichos, el testimonio solido de la verdad. ( The dreaming (sleeping) author. His only intention is to banish harmful platitudes and with this work of whims (caprichos) to give the lasting testimony of the truth. ). In the upper left corner of the drawing there is a white segment of a circle that can be understood as a light source and thus a symbol of the Enlightenment.

In the other earlier drawing there is no font, but a completely different background. In addition to bats, several human faces can be seen here, including two self-portraits of Goya, and a horse, possibly a Pegasus , jumping into the picture from behind with its head turned to the right. Another difference is the hand position of the sleeping artist, he folds his hands as if in prayer; in the other pictures the hands are just lying relaxed on top of each other. The center of this drawing is the head, from which the faces burst like rays.

Exhibitions (selection)

- 1976/77: The sleep of reason gives birth to monsters: Francisco de Goya (1746–1828). The “Caprichos”. Exhibition at the Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe (December 10, 1976 to February 20, 1977)

- 2000/01: The Sleep of Reason: Original etchings by Francisco de Goya University Museum of Fine Arts in Marburg (November 19, 2000 to February 18, 2001) and Instituto Cervantes in Munich (February 28 to April 6, 2001)

- 2005: Goya, prophet of modernity . Old National Gallery in Berlin (July 13th to October 3rd)

- 2006/07: The Sleep of Reason: Goyas Capricho 43 in visual art, literature and music in the University Library Duisburg-Essen (November 15, 2006 to January 12, 2007)

- 2012: At the edge of reason - picture cycles of the Enlightenment period in the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin (March 16 to July 29)

- 2012/13: Black Romanticism from Goya to Max Ernst in the Städel Museum in Frankfurt (September 26, 2012 to January 20, 2013)

- 2013: Reason gives birth to monsters . Kunstpavillon München , an exhibition in which the Goya etching served as a leitmotif for contemporary artists.

Individual evidence

- ↑ El sueño de la razon produce monstruos on museodelprado.es.

- ↑ Helmut C. Jacobs: The sleep of reason. Goyas Capricho 43 in visual arts, literature and music . Basel 2006, p. 106.

- ^ Peter K. Klein: Program and intention of the Caprichos. In: University Museum for Art and Cultural History, Marburg and Consorcio cultural Goya, Zaragoza (ed.): The sleep of reason. Original etchings by Francisco de Goya . Exhibition catalog Marburg and Munich 2001, ISBN 84-89721-77-7 , p. 15 ff.

- ↑ Werner Hofmann: Goya. From heaven through the world to hell . Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-54177-1 , p. 85 ff.

- ↑ Wilhelm Hennis: Goya's dream of reason gives birth to monsters. on humboldtgesellschaft.de (lecture from March 16, 1999 - Humboldt Society in Berlin).

- ^ Peter K. Klein: Program and intention of the Caprichos . In: The Sleep of Reason. Original etchings by Francisco de Goya , ed. from the University Museum for Art and Cultural History, Marburg and Consorcio cultural Goya, Zaragoza. Exhibition catalog Marburg and Munich 2001, ISBN 84-89721-77-7 , p. 19.

- ^ Jean-Baptiste Boudard: Iconology . Parma 1759.

- ^ Peter-Klaus Schuster: The Art of Enlightenment (text to the catalog of the exhibition). Berlin 2011, p. 12, ( online, PDF ).

- ↑ Manuela B. Mena Marquéz in: Goya-Prophet der Moderne . Catalog for the exhibition in the Alte Berliner Nationalgalerie and in the Vienna Art History Museum 2005/2006. Dumont, Cologne 2005, ISBN 978-38321-7561-0 , p. 14f.

- ↑ Werner Hofmann: Goya: From heaven through the world to hell. Munich 2003, pp. 135, 142f.

- ↑ El sueño de la razon produce monstruos on museodelprado.es

- ↑ Sueño first Ydioma universal. El author soñando on museodelprado.es

- ^ Peter-Klaus Schuster : Goya-Prophet der Moderne (text on the catalog of the exhibition). DuMont, Cologne 2005, ISBN 3-8321-7563-6 , p. 36 f.

- ↑ Exhibitions: The “Whims” of Goya. on uni-marburg.de

- ↑ Fear the cruellest of all creatures . In: » Die Tageszeitung « from July 23, 2005.

- ↑ On the Edge of Reason on smb.museum

- ↑ Black romance. From Goya to Max Ernst on portalkunstgeschichte.de

- ↑ VBK themed exhibition 2013: "Reason gives birth to monsters" on rosalux.de (PDF)

literature

- Helmut C. Jacobs : The sleep of reason. Goyas Capricho 43 in visual arts, literature and music . Schwabe, Basel 2006, ISBN 3-7965-2261-0 .

- Werner Hofmann: Goya. From heaven through the world to hell . C. H. Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-67065-7 .

Web links

- Sleep of Reason - Werner Hofmann explains Goya's attraction . In: » Die Welt « from May 8, 2004.

- Hartmut Kraft: Francisco Goya: Sleep or Dream? In: »Deutsches Ärzteblatt« from August 2005, p. 384.

- Maynor Antonio Mora: “El sueño de la razón…”: Apuntes sobre la idea de Razón en el grabado de Goya on pendientedemigracion.ucm.es (image interpretation, Spanish)

- Volker Bauermeister: Why a work by Goya is instructive in days of terror . In: badische-zeitung.de , December 30, 2016.