Jakob Johann von Uexküll

Jakob Johann Baron von Uexküll (* August 27 jul. / 8. September 1864 greg. Gut Keblas ( Estonian : Keblaste ), Village Mihkli , today Lääneranna , Estonia ; † 25. July 1944 in Capri ) was a biologist and philosopher and one of the most important zoologists of the 20th century.

Uexküll developed the basic structure of biosemiotics , which understands life as biological sign and communication processes. He introduced the concept of the environment into biology and is therefore considered a pioneer in ecology . He was an important pioneer in theoretical biology , cybernetics , semiotics , physiology, and the epistemological line of radical constructivism .

Life

Jakob Johann von Uexküll was born into a Baltic German family in 1864 as the third of four siblings, two older brothers and a younger sister, in Keblas ( Estonia ) as a Russian citizen. His mother, Sophie von Hahn, came from Courland. His father Alexander had studied in Heidelberg and was mayor of Reval ( Tallinn ) on a voluntary basis for years . From 1874–77, Jakob attended grammar school in Coburg , then the Knight and Cathedral School in Reval until he graduated from high school . As a schoolboy he studied Kant's writings intensively .

After graduating from school in 1884, he began studying zoology at the University of Dorpat . During a study visit of several months on Lesina (Dalmatia) with his teacher Max Braun , he carried out anatomical and systematic studies on marine animals. During his four-year studies in Dorpat, his first examination of the then new doctrine of Darwin , which he was introduced to by Julius von Kennel (1854–1939), Braun's successor, took place. About this important phase in the development of his thinking he writes:

“If I had previously dealt with the thinning of established facts, then Kennel suggested the theory for the first time. Kennel was an outspoken Darwinist and descent theorist. At first I was impressed by the connection between the animal forms that Darwin had created. A plausible explanation for the origin of the species seemed to be given by the simple notion of variation and the survival of the appropriate. There were a lot of problems to solve here, which the zoologists were primarily concerned with. But Kennel himself completely spoiled that impression when he assured me that he would be able to prove that any animal species was related to one another. I was right to say to myself: this is a gimmick and not a science. - Then I decided to leave zoology and turn to physiology. Because knowing the organs of animals had long made me want to observe them in their activity. "

Since then he has remained suspicious of theories . “Theories are cheap as blackberries,” he used to say. His widow writes about him in her biography:

“It was completely indifferent to him whether materialism , idealism or any other doctrine would prevail. The only thing that mattered to him was whether the hypotheses and theories that the natural sciences developed could stand before nature . "

He left Dorpat as a candidate for zoology and moved to Heidelberg in 1888 to work at Wilhelm Kühne's institute in the field of physiology . This activity was interrupted during the winter months by work at the zoological station in Naples , where he used his newly acquired knowledge on sea animals. He writes about it:

“In the head of the physiological department, Professor Schönlein, I found all kinds of competent support. Nevertheless, the pure muscle and nerve physiology could not captivate me for long. Researching the planned cooperation of the organs in the animal body seemed to me to be the more rewarding task. "

In Paris he learned the methods for an accurate recording of animal movements from Étienne-Jules Marey , a pioneer of chronophotography .

- In 1899, together with Albrecht Bethe and Th. Beer, he turned against a terminology that interprets life processes according to anthropomorphic ideas.

- From 1899–1900 he examined tropical sea urchins during a study visit to Dar es Salaam (East Africa) and discovered their shadow reflexes.

- 1903 marriage and move to Heidelberg. Investigations into the movement phenomena in leeches and study trips to Normandy (Berck sur Mer). Continuation of work on sea urchins.

- 1907 Awarded an honorary doctorate from the Medical Faculty of Heidelberg for his “precise and astute experiments on nerve and muscle stimulation”.

In the same year he formulated the concept of a scheme as part of his investigations on dragonflies and took a position against a mechanical view of the individual and the assumption of an objective external world that is identical for all living beings.

- 1908–1909 Investigations into the movement of stocks in Monaco . First edition of the book Environment and Inner World of Animals .

During this time, his application for the position of head of a newly planned Institute for Biology of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society (the predecessor of the Max Planck Society ) was rejected. In response to the notification that it would not be possible within the framework of the present plan to take into account the branch of biological science he represented, he first thanked him for the approval of funds for research trips.

- In 1911 he carried out studies on pilgrim clams in Roscoff and on the muscles of leeches in Utrecht.

- In 1914 he studied movement processes in lobsters in Biarritz .

- In 1917 he lost all his fortune due to the Russian Revolution and the expropriation of Estonia's estates.

- 1918 acquisition of German citizenship

- 1920 first edition of Theoretical Biology

- 1921 second edition of Environment and Inner World of Animals

- 1925 stays with relatives and friends in London, Friedelhausen near Gießen, Liebenberg in Brandenburg, and Schwerinsburg in Western Pomerania.

In 1924, at the age of sixty, he received an offer from the Medical Faculty of the University of Hamburg to accept a position as a scientific assistant with the prospect of an honorary professorship, and he became head of the aquarium, which was converted into the Institute for Environmental Research in the following years . From 1925 to 1940 he headed the institute - Emanuel Georg Sarris was one of its staff - and retired at the age of 76. In 1933 he signed the German professors' confession of Adolf Hitler . In 1934 he was a founding member of the Legal Philosophy Committee of the Academy for German Law , both of which were headed by Hans Frank . In 1940 he moved to Capri in Italy, where he died on July 25, 1944.

family

In 1903 Uexküll married in Schwerinsburg (now part of Ducherow ) Gudrun Countess von Schwerin (1878–1969), who in 1930 translated Axel Munthes The Book of San Michele into German. The couple had a daughter and two sons: Thure von Uexküll (1908–2004), one of the most important psychosomatic physicians, and the later journalist Gösta von Uexküll . The founder of the Right Livelihood Award , Jakob von Uexküll (* 1944), is a grandson of Jakob Johann and Gudrun von Uexküll.

plant

Uexküll's book “Environment and Inner World of Animals” (1909) provides a philosophical justification for biology as the science of living things. The term “environment”, previously hardly used in everyday language, is introduced here terminologically. It is to be strictly distinguished from the environment of an organism. The environment takes in living beings as objects, but the environment is shaped by them. A living being is always its own special environment. Its limits are not given by its surface (skin), but by its perception and its activity, its movements in space and time. Uexküll says that every animal has its own "subjective" time and its "subjective" space.

- It is "nothing but a comfort of thought to assume ... a single objective world."

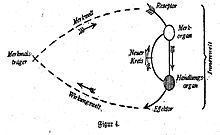

The animal's environment is reflected in its inner world; this in turn is divided into a memory world and a real world. The memory world means what an organism can perceive, the real world what it is able to do. There is an interaction between the two, which von Uexküll calls the “ functional circuit” . His famous example: the tick. Ticks can “notice” three aspects of the world: above - below, warm - cold, butyric acid: yes or no. This sensual faculty corresponds to organs that put something into action, that is, can bring about what ultimately serves the purpose of reproduction and species conservation, crawling, waiting, grabbing. The tick's environment is simple, composed of these three components. Their subjective time also: they can live for years without anything happening, suddenly a warm-blooded animal appears, the tick fulfills its mission and immediately dies. What is revolutionary about Uexküll's approach is that living beings are not viewed in isolation. A spider's web also belongs to it, the web in turn is an image of the coming prey.

Uexküll uses a vocabulary philosophically borrowed from Immanuel Kant when he assumes animals have a subjective sense of time and space. In terms of biology history, it ties in with the romantic naturalists Johannes Müller (1801–1858) and Karl Ernst von Baer (1792–1876) (according to his own admission) . For the first time, von Baer directed attention to the proper time of life and every living being. Viewing life as a subjective achievement is news. The opposite image of tracing life back to physical and chemical processes prevails paradigmatically in the sciences and in the everyday mind.

He described the following as subjective dependencies:

- Space and time are subjective phenomena.

- Every living being has its own subjective space and its own subjective time.

- All behavior can only be explained from processes in its subjective world (environment).

- These can only be processes that can be noticed due to the function of the sensory organs and thus receive a meaning for the living being.

Uexküll was in contact with the philosophers Ernst Cassirer , Edmund Husserl , Helmuth Plessner , Martin Heidegger as well as with the writers Rainer Maria Rilke , Gottfried Benn and others. He was also friends with the anti-Semitic ideologist Houston Stewart Chamberlain ; Uexküll wrote a foreword to his work The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century in 1928 . And Uexküll's monograph State Biology , a systematically important and semiotically fundamental and thoroughly original work, is certainly normatively characterized by radical opposition not only specifically to the Weimar Republic , but to democracy per se - for biotheoretical and semiotic considerations. However, this does not change the meaning of his life's work, in particular environmental theory. Without a formal doctorate and without a habilitation, he remained an academic outsider, albeit recognized.

The terminological version of the concept of the environment is of incalculable importance; it affects the sociology of the lifeworld as it does (biopolitically) on ecology. Also to be mentioned is the effect on radical constructivism (for example in Ernst von Glasersfeld ), physiology, cybernetics and semiotics, which Uexküll worked out together with his son.

Jakob von Uexküll's work is prominent among the philosophers Ernst Cassirer ( An Essay on Man , 1940), Helmuth Plessner (The question of the human condition , 1961) or Martin Heidegger ( The basic concepts of metaphysics. World, finitude, loneliness , Freiburg lectures 1929 / 1930, Frankfurt am Main 2004). The Danish author Peter Høeg gives an intensive literary treatment in his neo-romantic development novel The Plan of the Abolition of Darkness . The Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben recently got involved in Uexküll's environmental concept (2002 / German 2003). The German biologist and philosopher Andreas Weber refers to Uexküll, among others , for his theory of organic existence, which he wants to understand as autopoiesis of feeling, judgmental and meaningful subjects , to which not only humans but all living beings are to be counted.

Jakob von Uexküll's work is currently in the following aspects: ecology / environmental awareness ; Semiotics (theory of signs); the relationship between expression and lifeworld; the relationship between animals and humans. Von Uexküll did not acquire this meaning in biology itself.

criticism

One point of criticism concerns the tunnel vision that Uexküll assumes for life forms. Anthropologically, according to Hans Blumenberg , this does not do justice to man's open-mindedness. Uexküll conceives the environment as a bubble or tube, which Blumenberg (see below: literature) compared to a macaroni pack.

reception

Opinions of contemporaries:

- Adolf Portmann , biologist (1897–1982)

“... the work of Uexkülls has had a fruitful effect in contemporary biological thinking and working. ... If today we see the phenomena of life not only as the cause of consequences, but also as links in a prepared context, then his work is significantly involved. " (AP: Foreword to Uexküll, 1956: 7)

- Ludwig von Bertalanffy , philosopher, biologist, pioneer of systems theory (1901–1972)

“V. Uexküll's work largely consists of purely philosophical considerations - above all a new version of Kant's theory of space and time, and not of such theories as natural scientists are used to using to explain phenomena ... " (Bertalanffy: Theoretische Biologie, 1932 , Vol. 1: 3)

Reception on radical constructivism :

Uexküll's work was mentioned again and again in the context of radical constructivism, especially by Ernst von Glasersfeld and Paul Watzlawick as well as by Humberto Maturana , who had studied Uexküll's works at an early age:

“As a biologist, for example, I read about Uexküll very early on, before the new developments began, and I was impressed by his analysis of the relationship between the organism and the environment. Later I asked myself a question that is usually not thought through seriously and down to the last consequence - especially since scientists like to leave it to philosophers: What is cognition as a biological phenomenon? " (Maturana: What is recognizing ?, 1996: 221)

Various receptions in Uexküll:

- In ethology by Konrad Lorenz (1935), Adolf Portmann, Heini Hediger , Erich Klinghammer, Nikolaas Tinbergen (Schmidt 1980, Kull 1999b)

- In theoretical biology by Ludwig von Bertalanffy, Adolf Meyer-Abich (Meyer-Abich 1989), Richard Woltereck (Brauckmann 2001), René Thom (Kull 1999b)

- In ecology by Arne Næss (Nöth 1996, Heinz Brüll 1984), Klaus M. Meyer-Abich (1977) (Hauser 1996 a, b; Kull 1997; Uexküll 1993)

- In physiology by Wolfgang von Buddenbrock (1953) Mislin (1978)

- In medicine by Thure von Uexküll (Leithoff 1993, Otte 2001)

- In psychology by William Stern , Heinz Werner , Fritz Heider (Steckner 1986; Heider 1984), Viktor von Weizsäcker (Harrington 1996), Friedrich S. Rothschild (Bülow 1993)

- In cybernetics and computer science by Ludwig von Bertalanffy (Brier 2001, Ziemke 2001, Taux 1986, Flechtner 1972; Lagerspetz 2001)

- In linguistics by Heinz Werner (Heider 1984, Werner and Kaplan 1963, Steckner 1986), Helmut Gipper (2001). Heinrich Junker

- In philosophy by Max Scheler (1913), Ernst Cassirer (Cassirer 1972, van Heusden 2001, Moynahan 1999, Steckner 1986), Ortega y Gasset (Utekhin, 2001), Ernesto Grassi , Helmuth Plessner , Peter Wessel Zapffe (1941), Martin Heidegger (Vagt 2010), Gilles Deleuze (Bains 2001)

- In anthropology by Arnold Gehlen , Anthropologie: Ingold (1995) (Kokott 2001)

Honors

- 1907 honorary doctorate from Heidelberg University

- 1921 Corresponding member of the Society of Doctors in Vienna

- 1925 Honorary Member of the Estonian Literary Society in Reval (Tallinn)

- 1932 member of the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina

- 1934 honorary doctorate from the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Kiel

- 1936 Honorary Doctorate in Scientific Natural History from the University of Utrecht

He has been nominated for the Nobel Prize several times. The Goethe Medal of the Medical Faculty could no longer be awarded because of his death in July 1944.

Fonts

Publications in German:

- 1905. Guide to the Study of Experimental Biology of Aquatic Animals. Wiesbaden: JF Bergmann.

- 1909. Environment and inner world of animals . Berlin: J. Springer.

- 1913. Building blocks for a biological worldview. Collected essays, edited and introduced by Felix Groß. Munich: F.Bruckmann A.-G.

- 1920. Biological letters to a lady. Berlin: Verlag von Gebrüder Paetel.

- 1920. State biology (anatomy-physiology-pathology of the state). Berlin: Verlag von Gebrüder Paetel. (Special edition of the Deutsche Rundschau , edited by Rudolf Pechel).

- 1920. Theoretical Biology. Berlin: Verlag von Gebrüder Paetel.

- 1921. Environment and inner world of animals. 2. presumably u. verb. Berlin: J. Springer.

- 1928. Houston Stewart Chamberlain . Nature and life. Munich: F.Bruckmann A.-G (as publisher).

- 1928. Theoretical Biology. 2. completely edit again Berlin: J. Springer.

- 1930. The doctrine of life (= the world view, books of living knowledge, Ed. Hans Prinzhorn, vol. 13), Potsdam: Müller and Kiepenheuer Verlag, and Zurich: Orell Füssli Verlag.

- 1933. State Biology: Anatomy-Physiology-Pathology of the State. Hamburg: Hanseatic publishing house.

- 1934: Forays into the environment of animals and humans: A picture book of invisible worlds. (Collection: Understandable Science, Vol. 21.) Berlin: J. Springer (with Kriszat G.).

- 1936. Worlds never seen before. My friends' environments. A memory book. Berlin: S. Fischer.

- 1938. The immortal spirit in nature. Conversations. Christian Wegner Hamburg.

- 1939. Worlds never seen. My friends' environments. A memory book. 8th edition Berlin.

- 1940. Theory of meaning (= bios, treatises on theoretical biology and its history as well as on the philosophy of organic natural sciences. Vol. 10). Leipzig: Verlag von JA Barth.

- 1940. The stone from Werder. Hamburg: Christian Wegner Verlag.

- with Uexküll Th. from 1944. The eternal question: Biological variations on a Platonic dialogue. Hamburg: Marion von Schröder Verlag.

- 1946. The Immortal Spirit in Nature: Conversations.4. - 8th thousand Hamburg: Christian Wegner Verlag.

- 1947. The Immortal Spirit in Nature: Conversations. 9-18 Th. Hamburg: Christian Wegner Verlag.

- 1947. The meaning of life. Thoughts on the tasks of biology. Communicated in an interpretation of the lecture given by Johannes Müller in Bonn in 1824 On the need of physiology for a philosophical consideration of nature , with an outlook by Thure von Uexküll. Godesberg: Verlag Helmut Küpper.

- 1949. Worlds never seen. 9-13 Ed., Berlin, Frankfurt a. M.

- 1950. Almighty Life. Hamburg: Christian Wegner Verlag.

- with Kriszat G. 1956. Forays through the environment of animals and humans: A picture book of invisible worlds. Meaning theory. With a foreword by Adolf Portmann . Hamburg: Rowohlt.

- 1957. Worlds never seen. Munich.

- 1958. Forays into the environment of animals and humans. Meaning theory. Hamburg: Rowohlt (with Kriszat G.).

- 1962. Forays into the environment of animals and people. Meaning theory. Hamburg: Rowohlt (with Kriszat G.).

- 1963. Worlds never seen before. 13th thousand, Frankfurt a. M.

- 1970. Forays into the environment of animals and humans. Meaning theory. Frankfurt a. M .: S. Fischer (with Kriszat G.).

- 1973. Theoretical Biology. Frankfurt a. M .: Suhrkamp Taschenbuch Wissenschaft.

- 1977. The meaning of life. Thoughts on the tasks of biology, communicated in an interpretation of the lecture given by Johannes Müller in Bonn in 1824 On the need of physiology for a philosophical consideration of nature , with a view by Thure von Uexküll. Stuttgart: Ernst Klatt Verlag.

- 1980. Nature's composition theory. Biology as an undogmatic natural science. Selected Writings. Edited and introduced by Thure von Uexküll. Frankfurt am Main - Berlin - Vienna: Verlag Ullstein GmbH.

Quotes

- “All reality is a subjective appearance - this must also form the great basic knowledge of biology. Quite in vain one will search through the entire world for causes that are independent of the subject, one will always come across objects that owe their structure to the subject. ”- Theoretical biology. 2. completely edit again Berlin: J. Springer. P.9

- “The extended forms, as it were, the invisible canvas on which the world panorama that surrounds each of us is painted, giving the local signs bearing the colors posture and form. There is no other point of view towards the world panorama than that of our subject, because the subject as spectator is at the same time the builder of his world. An objective worldview that should do justice to all subjects must necessarily remain a phantom. ”- Theoretical Biology. 2. completely edit again Berlin: J. Springer. P.57

- “With the number of achievements of an animal, the number of objects that populate its environment also increases. It increases in the course of the individual life of every animal that is able to gain experience. Because every new experience requires a new attitude towards new impressions. New memorized images with new effects are created. ”- Forays into the environment of animals and people: A picture book of invisible worlds. (Collection: Understandable Science, Vol. 21.) Berlin: J. Springer (with Kriszat G.). P.69

- “The biologist, on the other hand, takes account of the fact that every living being is a subject that lives in its own world, the center of which is formed by it.” - Forays into the environment of animals and people: A picture book of invisible worlds. (Collection: Understandable Science, Vol. 21.) Berlin: J. Springer (with Kriszat G.), p.24

literature

- Brett Buchanan: Onto-Ethologies: The Animal Environments of Uexküll, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and Deleuze . In: SUNY series in environmental philosophy and ethics . State University of New York Press, New York 1975, ISBN 978-0-7914-7611-6 (English).

- Gilles Deleuze : Spinoza - Practical Philosophy. Berlin, Merve Verlag, 1981 (pages 162ff)

- Giorgio Agamben : The open : man and animal. Frankfurt a. M., Suhrkamp, 2003

- Carlo Brentari : Jakob von Uexküll . Brescia, Morcelliana, 2011 (pages 356; Italian)

- Hans Blumenberg : Lifetime and Universal Time . - Frankfurt a. M., Suhrkamp, 2001

- Alois Dempf : Die Weltidee , Einsiedeln, Johanes-Verl., 1955

- Carola L. Gottzmann , Petra Hörner: Lexicon of the German-language literature of the Baltic States and St. Petersburg . De Gruyter, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-11-019338-1 , p. 1333-1336 .

- Charlotte Helbach: Jakob von Uexküll's environmental theory : an example of the genesis of theories in biology at the beginning of the 20th century. - Aachen, Univ. Diss., 1989

- Peter Høeg : The Plan for the Abolition of Darkness , Roman, Reinbek, Rowohlt, 2001

- Anne Harrington: The Search for Wholeness. The history of biological-psychological holistic teaching: From the German Empire to the New Age movement, Reinbek near Hamburg, Rowohlt, 2002.

- Kalevi Kull : Jakob von Uexküll: An introduction. Semiotica Vol. 134: 1-59, 2001

- Florian Mildenberger: Environment as a vision. Life and work of Jakob von Uexküll (1864–1944). Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2007 (Sudhoffs archive. Journal for the history of science; issue 56).

- Jutta Schmidt: Jakob von Uexküll's environmental theory in its significance for the development of comparative behavioral research . Marburg, Univ. Diss., 1980

- Gudrun von Uexküll: Jakob von Uexküll, his world and his environment - e. Biography. Hamburg, Wegner, 1964

- Franz M. Wuketits: Jakob von Uexküll (1864–1944) and the discovery of the environment . In: Naturwissenschaftliche Rundschau, 67 (2014) pp. 397–404.

Web links

- Literature by and about Jakob Johann von Uexküll in the catalog of the German National Library

- Baltic Historical Commission (ed.): Entry on Jakob Johann von Uexküll. In: BBLD - Baltic Biographical Lexicon digital

- Newspaper article about Jakob Johann von Uexküll in the press kit of the 20th century of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Jakob von Uexküll (by Patrick Horvath) ( Memento from January 18, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- The Jakob von Uexküll archive for environmental research and biosemiotics at the University of Hamburg

- Biography in the culture portal West-Ost.

- Short biography Genealogical Handbook of the Baltic Knighthoods, Görlitz 1930

- Album academicum of the Imperial University of Dorpat , Dorpat 1889

Individual evidence

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento of the original from May 1, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Gudrun von Uexküll: Jakob von Uexküll, seine Welt und seine Umwelt, Hamburg 1964, pp. 35,66

- ↑ Ibid. P. 37

- ↑ Ibid. P. 39

- ↑ Katja Kynast: Cinematography as a medium for environmental research Jakob von Uexküll, in: kunsttexte.de, No. 4, 2010 (14 pages), http://edoc.hu-berlin.de/kunsttexte/2010-4/kynast-katja -6 / PDF / kynast.pdf

- ↑ Ibid. P. 90

- ↑ Jakob von Uexküll: Environment and inner world of animals . Ed .: Florian Mildenberger, Bernd Herrmann. Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg 2014, ISBN 978-3-642-41699-6 (with foreword, afterword and commentary on the position).

- ↑ Victor Farías: Heidegger and National Socialism, Frankfurt am Main: Fischer 1989, p. 277

- ^ Uexküll: Never Seen Worlds. Munich 1957, p. 11.

- ↑ Wolfgang U. Eckart : Jakob von Uexküll. Functional circle. In: History, Theory and Ethics of Medicine. 8th edition, Springer, Heidelberg / Berlin / New York 2017, p. 316 f. doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-662-54660-4

- ↑ Benjamin Bühler: Zecke . In: Benjamin Bühler, Stefan Rieger (eds.): Vom Überertier. A bestiary of knowledge . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-518-12459-5 , pp. 250-264 .

- ↑ Christina Vagt: »Umzu Wohnen«. Environment and machine at Heidegger and Uexküll . In: Thomas Brandstetter, Karin Harrasser, Günther Friesinger (eds.): Ambiente. Life and its spaces . Turia and Kant, Vienna 2010, ISBN 978-3-85132-568-3 , p. 91-106 .

- ↑ Harrington, Anne .: The search for wholeness: the history of biological-psychological holistic teachings: from the German Empire to the New Age movement . German First edition. Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verl, Reinbek near Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-499-55577-8 .

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento of the original from May 1, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Member entry of Jakob J. Baron von Uexküll at the German Academy of Natural Scientists Leopoldina , accessed on June 18, 2016.

- ↑ Nomination Database , nobelprize.org; accessed on Sep. 18 2016.

- ↑ List of publications ( memento of April 26, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) on zbi.ee

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Uexküll, Jakob Johann von |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Uexküll, Jakob Johann Baron von |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Biologist and philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 8, 1864 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Gut Keblas, Estonian Keblaste, village Mihkli , today to Lääneranna , Estonia |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 25, 1944 |

| Place of death | capri |