Great Depression

The Great Depression of the late 1920s and 1930s began with the New York stock market crash in October 1929. The main features of the crisis included a sharp decline in industrial production, world trade, international financial flows, a deflationary spiral , debt deflation , banking crises , the Insolvency of many companies and massive unemployment that caused social misery and political crises. The global economic crisis led to a sharp decline in total economic output worldwide, which began differently depending on the time and intensity, depending on the specific economic conditions of the individual states. The length of the global economic crisis varied in the individual countries and at the beginning of the Second World War it had not yet been overcome in all.

National Socialist Germany had overcome the world economic crisis in 1936 in important points and was one of the first countries to regain full employment . However, the development in Germany was also characterized by job creation measures with poor working conditions and generally low wages, which were frozen at the level of 1932, as well as the introduction of conscription in March 1935. In addition, full employment was accompanied by a massive misallocation of resources and ultimately the disaster of the Faced with World War II, which Germany triggered in 1939. In the United States, President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave the nation new hope with the economic and social reforms of the New Deal . Unlike in the German Reich and in many other countries, democracy in the United States was preserved even during the global economic crisis. The desperate state of the economy was overcome, but full employment was only achieved in 1941 with the arms boom after the USA entered the Second World War.

The analyzes of Keynesianism and monetarism belong to the modern scientific explanations of the causes and conditions of the world economic crisis . Newer expansions have developed to these explanatory approaches. There is a scientific consensus that the initial recession of 1929 would not have turned into a global economic crisis if the central banks had prevented the contraction of the money supply and alleviated the banking crises by making liquidity available. The international crisis export through the then existing currency regime of the gold standard and the protectionism that set in during the global economic crisis contributed to the global spread of the economic crisis.

Course of events

The problems that followed the First World War on the level of international financial relations, which remained unsolved until the 1930s, are part of the developmental context of the global economic crisis . In addition, in the run-up to the Great Depression, there was an economic boom in the United States - the new economic leadership - leading to a speculative bubble , which ended with a fall in the price of the New York Stock Exchange in 1929. The ensuing collapse of international credit and industrial production was accompanied by rampant trade protectionism to protect domestic markets. The individual economies were exposed to the sometimes drastic economic and social decline in their own way.

Postwar Problems of the International Financial System

The effects of the First World War not only posed problems for national budgets and financing systems in many countries, but also led to long-term changes in the constellations in international financial relations. With the exception of the United States, all the warring states had gone into enormous debt. So the victorious powers Great Britain and France sat on huge mountains of debt that had to be paid off against the United States, since they insisted on repayment.

This influenced and hardened the positions of these powers in the Treaty of Versailles that was imposed on Germany . For with the reparations imposed on the German Reich for war damage suffered, France in particular hoped to be able to settle its own war debts. Germany, which is heavily indebted for its part, would only have been able to make corresponding compensatory payments through stable export revenues. Since the victorious powers did not open their markets for this, the reparations question remained an unsolved problem. John Maynard Keynes saw in the Versailles Treaty “nothing to rebuild Europe economically, nothing to make the defeated Central Powers good neighbors, nothing to stabilize the newly formed European states […]. No agreement was reached in Paris to rebuild the public financial affairs of France and Italy, which had gotten out of hand, or to reconcile the economic systems of the Old and New World. ”The thesis that German reparations payments were also a cause of the global economic crisis because they when payments with no equivalent contributed to confusing interest rate differentials is controversial among economic historians . Keynes, on the other hand, warned of considerable negative consequences for the economy as a whole after the terms of the Versailles peace treaty became known .

Economic boom and speculative bubble in the USA

After the Weimar Republic, as the heir to the German Empire, was unable to solve either the national debt it had assumed or the reparations problem , had allowed the savings of the middle classes to be destroyed during the Great Inflation and was on the verge of collapse in 1923, it was the United States that did with the Dawes Plan and the Dawes Loan contributed to relative stabilization and thus ushered in the " Roaring Twenties ". The new global economic weight of the USA was also evident beyond Germany and Europe. The United States' foreign borrowings from 1924 to 1929 nearly doubled that of the pre-war world and pre-war economic power Great Britain. Markets in Asia and South America, which before 1914 had been dominated by European producers, were now largely under the influence of the United States.

The economic boom in the US of the 1920s, which remained in consciousness as the Roaring Twenties , was driven by automobile production and the electrification of households, which were equipped with refrigerators, vacuum cleaners and washing machines, among other things. The rapid growth of the consumer goods industry was due in part to the fact that many US citizens used credit to finance some of their purchases . While consumer credit had been $ 100 million in 1919, that figure rose to over $ 7 billion by 1929. So boosted wage increases, credit financing and installment contracts the consumer to; Tax cuts also stimulated willingness to invest and supported a climate of general economic optimism. The speculative fever also spread to classes of society that were not traditionally associated with the stock market ( maid house boom ). There was correspondingly lively stock trading in general and especially on the New York Stock Exchange, where transactions in 1928 were more than 50 percent higher than the previous year's record.

While there had been 1,928 short-term significant price falls given, but ultimately the price barometer rose but ever onwards. And the stock market was now expanding, driven by speculation, more and more on a credit basis. Even in the summer of 1929, unlike usual, there was no calming of stock market activities, but the prices of industrial stocks rose again within three months by a quarter. This is why US investors withdrew capital from Europe during the exorbitant boom phase in the stock market to invest even more profitably in domestic equity trading. From June 1928 onwards, the granting of loans by the USA to Germany and other countries in Europe, Asia and Oceania virtually collapsed.

Wall Street crash with global economic consequences

From June 1929 the real economic industrial development in the USA declined: Steel production fell; the freight rates of the railways fell; housing construction collapsed; and in the fall, with the repeated dramatic falls in prices on the New York Stock Exchange, the speculative bubble that had been growing unchecked up until then burst. On a “zigzag path into the abyss”, October 24, 1929, Black Thursday , only represented a particularly striking turning point in the price plunge. “On this day, 12,894,650 shares changed hands, most of them at a price that raised hopes and The previous owners' dreams were completely destroyed. ”Contrary to the existing expectations that things would pick up again after the course corrections in autumn 1929, the downward trend continued until July 1932, interrupted by phases of slight recovery and price stabilization. The real economy also suffered devastating slumps. On July 8, 1932 , Iron Age announced that the capacity of the steel companies was only being utilized to 12 percent.

The wave-like withdrawal of US foreign investments and loan funds - which were now needed to cover liabilities in the USA - as a result of the New York stock market crash, directly affected the German economic life in the Weimar Republic, which was based on these funds. Shortages of money and deflation resulted in falling production , layoffs and mass unemployment. The number of just under three million unemployed in 1929 more than doubled in 1932. Unemployment protests and a massive increase in votes for the KPD were the result. Not only in Germany, but in all of Central Europe, the unstable situation of many banks in particular threatened the functioning of the national economies. When the transatlantic inflows of credit collapsed, there was a decline in the value of the credit protection offered by companies B. had deposited with the banks in the form of securities and share certificates . The danger of a bank panic was in the air in the early 1930s, so to speak. It was fueled in May 1931 by a high loss report from Creditanstalt , the largest Austrian bank. This was followed in Germany by the collapse of the DANAT bank and an emergency ordinance regime that strictly limited the availability of bank balances and thus paralyzed economic activity.

Banking system crisis

United States

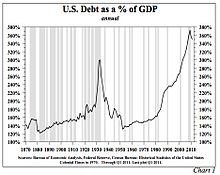

As a result of the depreciation of volatile investments as a result of the stock market crash, the insolvency of many borrowers and bank rushes , a series of bank failures occurred in the United States, which resulted in the liquidation of a third of all banks. This created a general credit crunch, which in many cases made it impossible to extend or extend credit. This in turn resulted in mass bankruptcies in the real economy . The banking crisis also severely disrupted the bank money creation function . In this situation the US Federal Reserve (FED) could have stabilized the banks, but did not do so. On the contrary, it pursued a contractionary monetary policy that reduced the money supply by around 30% ("great contraction"), forcing the deflationary spiral and thus the banking and economic crisis worsened.

Germany

The German banking crisis marked the beginning of the second part of the economic crisis, the beginning of "hyperdeflation". It had two causes: due to mutual competition, hostile takeovers of smaller banks and speculative securities and commodity transactions, the big banks had regained their 1914 business volume in 1925. They were geared towards expansion, but poorly equipped for this due to their low equity ratios and low liquid funds. If they had increased their equity (through lower dividend payments and / or issuing more shares), the difference between the two sizes and the sum of the loans granted would not have been so great.

Added to this was the instability of the international credit market. The most important characteristic of this was the one-sided flow of money and capital. From 1925 to 1929 foreign loans totaling 21 billion ( RM ) flowed into Germany, compared to only 7.7 billion RM for German investments abroad in the same period. A large part of the loans taken out were also of a short-term nature, meaning that they had to be repaid within three months. But they were regularly extended until 1929. The banks sometimes loaned out these short-term funds with long terms. Thus, the situation of the banks was critical even before the global economic crisis: Should the foreign creditors lose their confidence in the solvency of the banks and not extend the short-term loans, there was an immediate threat of a sensitive shortage of foreign currency and even illiquidity . The crisis also led to a shortage of liquidity in banks abroad. In November 1930 the banks in the USA and France , where the economic crisis had otherwise not yet made itself felt, got into a crisis and withdrew large sums of short-term funds from Germany. Here, the crisis primarily affected smaller banks, so the extent was initially not as transparent.

In the spring of 1931, the Austrian Creditanstalt ran into difficulties, which had "taken over" when it took over the Bodenkreditanstalt. Contemporaries suspected that the French government was behind this, trying to torpedo the plan for a German-Austrian customs union . Although such manipulations were actually discussed in the French government, it could not be proven that they were responsible for the collapse of Creditanstalt, which declared its insolvency on May 11, 1931. That meant the beginning of a financial crisis not only for Austria, but for all of Central Europe .

It was now feared that this development would spread to Germany. In this situation, Chancellor Brüning himself declared in June 1931 for domestic political reasons - namely, he was hoping for the support of the right and the National Socialists in the Reichstag for a new package of austerity measures - the reparations publicly as "unbearable". This seemed to point to an impending insolvency of the Reich and undermined the confidence of the foreign lenders lastingly. Foreign currency worth several billion RM was withdrawn, and after one of Berlin's big banks had become illiquid in July 1931, there was also a massive run of the population on the banks ( bank rush ). They had to stop their payments on July 13, 1931. Accounts payable amounts decreased 21.4% in June / July. To overcome the banking crisis, the banks were closed for several days and placed under government control. The Berlin stock exchange also remained closed until September 1931, and it was closed again shortly afterwards when the United Kingdom left the gold standard. Loans and new investments were impossible for a long time.

In addition, in June 1931, the Hoover moratorium , which had canceled all political debts for a year to restore confidence, had psychologically fizzled out because French reservations had required weeks of difficult negotiations. Since Reichsbank President Hans Luther wanted to reverse the outflow of foreign currency abroad by all means, he briefly increased the discount rate to 15% (in order to attract foreign currency again), which however did not succeed and which is why hardly any credit could be given to the private sector (the currency was already covered). The banknotes in circulation amounted to 5 billion RM in 1929 and decreased by 30% to 3.5 billion RM in 1932. At the secret conference of the Friedrich List Society in September 1931 , possibilities for credit expansion were discussed.

Problems and reactions in central areas of the world economy

Britain had already gone through a difficult decade economically when the shock waves of the US disaster hit the island kingdom. Even during the 1920s, there was always a relatively high number of unemployed of over a million. The peg of the British pound to the gold standard at the pre- war rate, which was abandoned in the course of the financing of the war, but was re-established in 1925 , may have been aimed at renewing London as a world financial center, but it did not stimulate the British economy, in which hardly any investments were made due to the high level of lending. In addition, the now high exchange rate of the pound weakened British trade: while British products were too expensive abroad, foreign products were now cheap in Great Britain.

The global economic crisis initially made itself felt in Great Britain as a collapse in world trade. From 1929 to 1931 the value of British exports fell by around 38 percent. At the turn of 1932/33, unemployment peaked at just under three million. A rigid austerity program led to hard clashes within the ruling Labor Party and to the formation of a "national government" including conservative and liberal ministers in August 1931. On the following September 21st, the pound for gold was abandoned after the Bank of England reduced its gold reserves Support of the Austrian Creditanstalt and in the German banking crisis had started to avert a pan-European banking crisis. When investors, commercial banks and several central banks from smaller European countries rushed to the Bank of England , it was no longer able to support the pound because the majority of its reserves were in Austria and Germany. Within a few days after the gold disbursements were stopped, the exchange rate of the pound against the US dollar fell by around 25 percent. With this, however, the British export economy regained its competitiveness, albeit under changed world market conditions. At the same time, the devaluation of the pound resulted in a clear revival of the British domestic economy, so that, despite continued high unemployment figures, after 1931, according to Florian Pressler, Great Britain developed “better than all other large industrial nations”.

France, which had also returned to the gold standard in 1926, was initially spared the turbulence of the global economic crisis. Industrial production was far less dependent on foreign markets than British production, the agricultural market was protected by high import duties and the franc was relatively undervalued. Hence, capital looking for safe investment opportunities poured into France in large quantities. The banknote cover rose to 80% by 1931, and the Banque de France held a quarter of the world's gold reserves. This comfortable situation changed drastically with the British departure from the gold standard and the devaluation of the pound in September 1931, as the franc and the other currencies of the "gold bloc" now appeared overvalued. Now the global economic crisis began in France as well: There was unemployment, foreign trade fell, production remained below the level of 1928 until the beginning of the Second World War. Unemployment in France remained comparatively moderate and never exceeded five during the crisis Percent; but by defending the gold standard of the franc at a costly price, the French national budget got into trouble from 1931 onwards.

The resulting policy of tight money and deflation destabilized the Third French Republic under pressure from extremists, while the middle class was hardest hit by economic decline and became radicalized. Demonstrations of the right-wing extremist Action française and the left- wing extremist Parti communiste français led to riots with fatalities in 1934. After changing center-right governments failed to cope with the crisis until 1935, the Popular Front under the leadership of Léon Blum prevailed as the base of government in the May 1936 elections . In the wake of strikes and economic paralysis, significant wage increases were granted, the operational position of the trade unions was strengthened and the weekly working time was reduced from 48 to 40 hours. In view of an increase in working hours to up to 54 hours per week introduced in Nazi Germany at the same time, the competitiveness of French industry was considerably weakened. This resulted in an extensive relocation of capital abroad and now also made the gold reserves of the Banque de France dwindle. Overall, in the decade from 1929 to 1939, France experienced a radical decline in terms of economic weakness and political disruption.

The individual states reacted differently to the challenge, depending on how they were affected and according to the political guidelines. Starting from the Scandinavian countries, functioning democracies began to control market events and develop approaches for a transition to the welfare state (see, for example, the subsequent Swedish model ). US President Hoover's hesitant reform approaches to overcome the Great Depression were reinforced by his successor Franklin D. Roosevelt from 1933 onwards ( New Deal ), including through growth-promoting public investments financed through increased borrowing ( deficit spending ).

The German Chancellor Heinrich Brüning, on the other hand, under the impression of the previous Great Inflation, tried to strengthen the currency through an austerity policy, which went hand in hand with serious social hardship and deep cuts in the social security system . This contributed to a political radicalization of broad sections of the population - including street fights between Nazis and Communists - which favored the rise of the NSDAP .

Effects on the global economic periphery

Not only the global economic centers of North America and Europe at the time were affected by the Great Depression in the 1930s, but also those states and regions around the world - in relation to the aforementioned centers they are technically referred to as the periphery - which until then had been either Objects served colonial exploitation or were only of secondary importance in the global economy. On the other hand, some parts of the world were almost completely on their own at that time - for example Nepal and regions in Central Africa - and were accordingly little affected. Incidentally, the consequences of the global economic crisis were again different in the periphery, but there were also specific similarities.

Most countries were mainly, if not solely, involved in the world economy through their agricultural exports and dependent on the related revenues for their ability to import industrial products. The fall in prices for agricultural products during the global economic crisis was much more drastic than that for industrial products. This deterioration in the terms of trade brought the countries of the so-called periphery additional disadvantages in world trade during the crisis.

For those people on the global economic periphery who lived in colonial dependency, the situation was made more difficult by the fact that the colonial ruling elite in this situation was primarily concerned with supporting the main sources of income of the colonial economy , i.e. plantations , mining companies and trading companies. An attempt was made to maintain their international competitiveness by reducing wages, so that the local workers had to take responsibility for the upheavals in foreign trade. Even when it came to funding the colonial administrative apparatus itself, when tax revenues fell, companies did not stick to the company, but tried to keep the colonial population harmless by increasing taxes.

For Pressler, the most significant effects of the global economic crisis, as far as the so-called periphery are concerned, can be found in people's thinking. Because in this crisis they began to understand the lack of their own industry as underdevelopment. The dramatic deterioration in the terms of trade experienced at the time had shaken belief in a mutually beneficial division of labor between industrial centers on the one hand and agricultural and raw material suppliers on the other. The decolonization of Africa and Asia began during the 1930s, even if the independence was only achieved after a long period in the wake of the Second World War.

Effects

production

| country | decline |

|---|---|

| United States | - 46.8% |

| Poland | - 46.6% |

| Canada | - 42.4% |

| German Empire | - 41.8% |

| Czechoslovakia | - 40.4% |

| Netherlands | - 37.4% |

| Italy | - 33.0% |

| France | - 31.3% |

| Belgium | - 30.6% |

| Argentina | - 17.0% |

| Denmark | - 16.5% |

| Great Britain | - 16.2% |

| Sweden | - 10.3% |

| Japan | - 8.5% |

| Brazil | - 7.0% |

Labor market situation

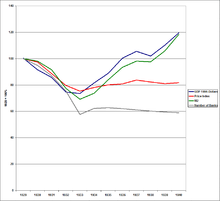

With industrial production, the standard of living also fell. In the early 1930s, the unemployment rate in industrialized countries rose to 25%. Unemployment slowly fell from the mid-1930s.

The economic development in Germany up to 1930 did not seem to differ from the years before. The number of unemployed in 1927 was about 1 million; At the end of September 1929 there were 1.4 million unemployed, in February 1930 there were 3.5 million, which was attributed to seasonal fluctuations. When, contrary to expectations, this number did not decline in the spring of 1930, the Reich government (until March 30, 1930 the Müller II cabinet , which was followed by the Brüning I cabinet ) and the Reichsbank hoped for a long time for the economy to heal itself, although the unemployment figure at the end of 1930 was 5 Million unemployed in a global comparison at the highest level. It was only when the slight decline did not continue in mid-1931 that one became fully aware of the extreme development of the crisis. At that time, Brüning's austerity program was already in full swing. Public salaries have been reduced by 25% and unemployment benefits and social assistance have been severely cut. In February 1932 the crisis on the labor market reached its climax: there were 6,120,000 unemployed, 16.3% of the total population, compared to only 12 million employees. The unemployed could also include the large number of poorly paid short-time workers and white-collar workers, but also the small business owners who are on the brink of ruin.

The effects in the USA were particularly disastrous for the farmers. The producer prices for agricultural products fell by 50% between 1929 and 1933, as a result of which tens of thousands of farmers could no longer service their mortgages and lost their land. During the same period, agricultural production increased by 6%. The increase is explained by the conversion of agriculture to lease contracts and mechanized processing of larger units by the new investors, later also by the artificial irrigation by the New Deal , whereby the Dust Bowl, the proverbial dust bowl of the Midwest, lost its name. The desperate farm workers fled to the West, where they sought a livelihood under inhumane conditions. An impressive document about the agricultural crisis in the USA is the novel The Fruits of Wrath by John Steinbeck , who himself accompanied such a refugee train.

In manufacturing and mining, the social impact in the United States was partially mitigated by the fact that the average number of hours per week, also under pressure from the government, fell by approximately 20% from 1929 to 1932.

The situation in Japan was completely different. The Japanese economy grew 6% from 1929 to 1933. Japan had a serious recession around 1930; but this was dealt with quickly. Unemployment and social upheaval as in the USA and Germany did not occur in Japan.

German foreign trade

Foreign trade declined considerably during the First World War and in the post-war years. The hyperinflation of 1923 had facilitated the recovery of German industry, but it also led to massive bad investments. German industrial production reached its pre-war level as early as 1926, but imports exceeded the export value of the pre-war year in 1925: Germany had a passive trade balance until 1930 . Imports fell during the Great Depression.

| year | Foreign trade total in million RM |

Export in million RM |

Imports in million RM |

Surplus = export - import in million RM |

Average gold and foreign exchange holdings in million RM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1928 | 26,277 | 12,276 | 14.001 | −1,725 | 2,405.4 |

| 1929 | 26,930 | 13,483 | 13,447 | +36 | 2,506.3 |

| 1930 | 22,429 | 12,036 | 10,393 | +1,643 | 2,806.0 |

| 1931 | 16,326 | 9,599 | 6,727 | +2,872 | 1,914.4 |

| 1932 | 10,406 | 5,739 | 4,667 | +1,072 | 974.6 |

| 1933 | 9,075 | 4,871 | 4,204 | +667 | 529.7 |

| 1934 | 8,618 | 4.167 | 4,451 | −284 | 164.7 |

| 1935 | 8,429 | 4,270 | 4.159 | +111 | 91.0 |

| 1936 | 8,986 | 4,768 | 4,218 | +550 | 75.0 |

| 1937 | 11,379 | 5,911 | 5,468 | +443 | approx. 70.0 |

| 1938 | 10,706 | 5,257 | 5,449 | −192 | |

| 1939 | 10,860 | 5,653 | 5,207 | +446 |

Political Consequences

Measures to overcome the crisis in Germany

The economic downturn in Germany (Weimar Republic) began in 1928. The massive foreign exchange deductions after the devaluation losses of the foreign banks from the stock market crash in 1929 intensified the downturn in Germany. After the Reichstag election in 1930 , foreign credits were withdrawn again. This was mainly due to two reasons, one external and one internal.

First, the NSDAP had become the second largest party, and this political development abroad worried and wanted to increase liquidity in the countries concerned. The Reich government, for its part, viewed the economic crisis as an imbalance in the state budget . The deficit at the end of 1929 was 1.5 billion RM. The Reichsbank stepped in when the coverage of the gold and foreign exchange reserves of the money in circulation fell below the statutory 40 percent limit through the transfer of canceled foreign loans (see gold currency standard ), and the increases in the key interest rate exacerbated the crisis.

The measures taken by Chancellor Heinrich Brüning also exacerbated the crisis . He started from the need to keep the imperial budget balanced, since the capital market was not available to finance a deficit. In several emergency ordinances , government spending was reduced by cutting wages and salaries in the public sector and by ending all public construction projects, while tax increases were intended to increase income. However, this austerity policy intensified deflation and had a dampening effect on the economy, so that the desired goal of sustainable budget consolidation was not achieved. In December 1931 the government adopted an active deflationary policy and lowered all prices, wages and rents by emergency decree. In doing so, she hoped to boost exports and accelerate the cleansing effects of the crisis, so that Germany would be the first country to overcome the depression. This policy was unsuccessful: the key interest rates remained high because of the desperate foreign exchange situation after the banking crisis, as did taxes: the government had once again increased sales tax at the same time as the deflationary measures, so that they had no stimulating effect on the economy. The hoped-for external economic effects did not materialize, since Great Britain had already separated the pound sterling from gold in September 1931 and, through the subsequent devaluation of its currency, achieved a clearer foreign trade advantage than Germany with its deflation.

Due to the fact that Brüning's deflationary policy was obviously wrong in retrospect, older researchers suspected that his primary aim was to deliberately intensify the crisis to convince the Allies that the reparation demands could simply not be met. In addition, the suspension of payments would weaken the radical political forces. However, because he expressed the connection between reparations and deflationary policy almost exclusively in public speeches and not in internal discussions, recent research believes that he was honestly convinced that he had no alternative to his policy.

Brüning was in a quandary: he had to prove to Germany's reparation creditors that he was honestly willing to fulfill the Young Plan , but this made himself vulnerable to the political right, whose domestic political support he nevertheless hoped for. He strove for a customs union with Austria, which, as already mentioned, initiated the collapse of the banking system because of France's resistance.

Whether there were viable alternatives to Brüning's deflationary policy and economical budget management, which only exacerbated the crisis, is very controversial in historical research. A) a decoupling of the Reichsmark from the gold currency standard would have been conceivable , b) an expansion of credit or c) an increase in the amount of money, e.g. B. through central bank loans. As the Munich economic historian Knut Borchardt tried to demonstrate, there were important arguments against all three options: Due to the crisis of confidence (which was partly made worse by its own fault), the Reich government had no credit options: the almost chronic crisis in public finances repeatedly threatened to turn into an acute one To deal with the insolvency of the public sector, which would have had unforeseeable social, political and external economic consequences; A departure from the gold currency standard was ruled out under international law by the Young Plan and would have awakened the traumatic memories of the inflation of 1923. The same arguments would have spoken against compensating the deficit budget with the help of the printing press.

The fact is that in the Reichstag elections in July 1932 only the NSDAP appeared with a program of massive, reflationary credit expansion and job creation and was thus able to more than double its share of the vote to 37.3%. The center, but also the moderate left - the latter under the influence of Rudolf Hilferding and Fritz Naphtali - remained stuck with the notions of financial and economic-political orthodoxy and thus had little to counter the economic-political propaganda of the extreme right. Even the expansive WTB plan drawn up around the turn of 1931/32 (named after Wladimir Woytinsky , Fritz Tarnow and Fritz Baade ) was unable to develop any propaganda effect in view of this internal resistance. While Franklin D. Roosevelt was able to stabilize democracy in the USA with his expansive New Deal program , in Germany the right-wing extremist NSDAP achieved its final breakthrough in these elections.

The credit expansion, which was initiated under Brüning's successors and which Hjalmar Schacht , Reichsbank President from 1933 to 1939, then carried out on a massive scale during the National Socialist era , was only possible thanks to the considerable disguising mechanisms of the Mefo bills . In the first few years it appeared extremely successful in terms of economic policy: in no other country did it succeed in moving from the depression into a new phase of prosperity and achieving full employment so quickly. Contemporaries therefore viewed the economic development in Germany as a National Socialist "economic miracle". This contrasts with the dire consequences of this upswing, which was essentially based on the arms boom , on the preparation of a great, ultimately self-destructive war of conquest . Historians and economists therefore warn against the misinterpretation that Nazi politics restored prosperity. Per capita consumption did not reach pre-crisis levels until the end of the 1930s. At no point was National Socialism able or willing to restore the prosperity level of the Weimar Republic. Mass unemployment has been substituted by jobs similar to forced labor. Knut Borchardt warns of a "fateful historical legend" that the National Socialist economic policy was not a monetary or economic policy in the modern sense that brought about a self-sustaining upswing, but merely a war economy in peacetime. The change to an economic upswing was initiated with the announcement of the Papen Plan in August 1932. The mood of the economic players improved. The previously increasing unemployment stopped. The Papen Plan was (at the request of Chancellor Franz von Papen ) a predominantly supply-oriented concept, ie companies were granted tax breaks (tax vouchers) and their current costs were reduced in order to encourage them to invest. Investment activity remained below expectations during the Papen's cabinet . It was only under the Schleicher cabinet (December 1932 / January 1933) that job creation programs to stimulate the economy at (limited) state costs became essential.

Actions to Overcome the Crisis in the United States

In the United States, the Great Depression caused a major upheaval in political, social, and economic history. President Franklin D. Roosevelt implemented extensive economic and social reforms known as the New Deal .

Worldwide response

The Great Depression caused some reactions that can be observed around the world:

- Due to the global economic crisis, the gold standard was abandoned worldwide .

- Unions became more influential. Union membership doubled in the United States.

- The welfare state expanded substantially in the 1930s.

- In most states, regulation of the economy has been strengthened, in particular through the creation of a financial market regulator and banking regulation .

Scientific explanations

There is a consensus among historians and economists that the initial recession of 1929 would not have turned into a global economic crisis if the US central bank had prevented the contraction of the money supply and alleviated the banking crisis by making liquidity available. This criticism, elaborated in detail by Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz in A Monetary History of the United States (1963), was essentially formulated by John Maynard Keynes . The contemporary attempts at explanations, which recommended the contrary, are consequently discredited.

The thesis by Milton Friedman / Anna J. Schwartz that the world economic crisis was primarily a monetary crisis triggered by a contraction of the money supply as a result of the banking crisis was supported by 48% of the participating economists in a 1995 survey and endorsed in principle by 34% of the participating historians. The opposite thesis by John Maynard Keynes, that a decline in demand, in particular a decline in investment, caused the Great Depression and the banking crisis was merely a consequence of it, was in principle supported by 61% of economists and 51% of historians in the same survey .

Peter Temin's thesis that a purely monetary explanation was contrived because the demand for money fell more sharply than the money supply in the early years of the crisis, was agreed by 60% of economists and 69% of historians. More recently, Friedman / Schwartz's monetarist declaration of crisis has been expanded to include non-monetary effects that aim to better match empirical evidence and have met with a great positive response in science.

Some countries did not have a major banking crisis, but were plagued by deflation, a sharp drop in industrial production and a sharp rise in unemployment. The monetarist declaration is not readily applicable to these countries. Historians and economists, however, almost agree that in these countries the gold standard acted as a transmission mechanism that carried the American (and German) deflation and economic crisis across the world by (also) the governments and central banks of other countries to a deflation policy force. There is also a consensus that the protectionist trade policy created by the crisis has made the global economic crisis worse.

Contemporary attempts at explanations

The contemporary crisis interpretations of the Austrian School, Joseph Schumpeters and the underconsumption theory have had no support in the mainstream of economists and historians since the mid-1930s. The theory that income inequality was a major cause of the crisis has had a major impact on some of the New Deal architects . It is more likely to be supported by historians, at least at the moment there is no consensus on this in the economic mainstream.

Joseph Schumpeter

Joseph Schumpeter saw the Great Depression as a historic accident in which three business cycles , the long-term Kondratiev cycle of technical innovation, the medium-term Juglar cycle and the short-term Kitchin cycle reached their lowest point in 1929. Schumpeter was a proponent of the liquidation thesis.

Austrian school

In contrast to the later Keynesian and monetarist explanations, economists of the Austrian School saw the expansion of the money supply in the 1920s as the cause, which resulted in a misallocation of capital. The recession must therefore be seen as an inevitable consequence of the negative effects of the false expansion in the 1920s. Government intervention of any kind was deemed wrong because it would only prolong and deepen the depression. The monetary overinvestment theory was the dominant notion around 1929. The American President Herbert Hoover , who largely followed this theory during the Great Depression, later complained bitterly about these recommendations in his memoirs.

Friedrich Hayek had criticized the FED and the Bank of England in the 1930s for not pursuing an even more contractionary monetary policy . While economists such as Milton Friedman and J. Bradford DeLong assign the representatives of the Austrian School to the most prominent advocates of the liquidation thesis and assume that they influenced or supported the policy of President Hoover and the Federal Reserve in terms of non-interventionism, the representative represents the Austrian school Lawrence H. White school believed that the passivity of the Federal Reserve could not be traced back to overinvestment theory. He objects that overinvestment theory has not called for a contractionary monetary policy. Hayek's call for an even more contractionary monetary policy was not specifically related to overinvestment theory, but to his hope at the time that deflation would break wage rigidity. Since the 1970s, Hayek also sharply criticized the contractionary monetary policy of the early 1930s and the mistake of not providing the banks with liquidity during the crisis.

Underconsumption Theory and Income Inequality

In the industrial sector, productivity increased very strongly through the transition to mass production ( Fordism ) and through new management methods (e.g. Taylorism ). In the golden 1920s (mainly US due to the balance of payments surplus as a creditor from World War I) there was a rapid expansion of the consumer goods and capital goods industries. Since corporate profits rose significantly faster than wages and salaries and, at the same time, credit terms were very favorable, there was an apparently favorable investment climate that led to overproduction . In 1929 there was a collapse in the (already too low) demand and an extreme deterioration in loan terms.

Just as in industry, productivity had increased dramatically in agriculture. The reasons for this were the increased use of machines (tractors etc.) and the increased use of modern fertilizers and insecticides . As a result, prices for agricultural products fell continuously as early as the 1920s. Due to the Great Depression, demand also fell, so that the market for agricultural products had almost collapsed by 1933. In the United States, for example, the wheat fields in Montana were rotting because the cost of harvesting was higher than the price of wheat. In Oregon, the sheep were slaughtered and left to eat for buzzards because the price of meat no longer covered transport costs.

Some economists like Rexford Tugwell , Adolf Augustus Berle , John Kenneth Galbraith and others. a. see a cause of the crisis primarily in the pronounced concentration of income . They justify this by saying that the highest-income 5% of the American population had nearly a third of all income in 1929. Because more and more income was concentrated in a few households, less was spent on consumption and more and more money flowed into “speculative” investments. This made the economy more vulnerable to crisis.

Modern explanations

John Maynard Keynes

theory

In his Tract on Monetary Reform (1923), John Maynard Keynes found that fluctuations in the money supply can have distributive effects, since some prices, such as wages and rents, are “stickier” (less flexible) than others. This can lead to an imbalance between supply and demand in the short term, which has a negative impact on economic growth and employment. During the Great Depression it was actually observed that wages fell less sharply than prices. Compensation through wage cuts was too risky a solution for Keynes, since companies would not invest the money saved in an economic crisis, but would rather keep it liquid. In this case, wage cuts would only reduce demand. To restore the equilibrium between supply and demand, he instead recommended a corresponding expansion of the money supply.

The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936) explained the length and severity of the Depression by stating that investment decisions depend not only on the cost of financing (interest rate), but also on positive business expectations. Accordingly, a situation can arise in which entrepreneurs are so pessimistic that they will not invest even with extremely low interest rates ( investment trap ). The companies would only employ as many people as are needed to produce the amount of goods that are likely to be sold. Contrary to neoclassical theories, a market equilibrium can thus also settle below the full employment level ( equilibrium in the case of underemployment ). This is the Keynesian explanation for the only slowly falling unemployment after the end of the recession phase (which lasted from 1929 to 1933) until the end of the 1930s. In this situation of extremely pessimistic business expectations, monetary policy alone cannot revive the economy; Keynes therefore considered a debt-financed government deficit spending program to be necessary to stimulate demand and investment.

According to Keynes, deflation is particularly harmful because consumers and companies assumed, based on the observation of falling wages and prices, that wages and prices would fall even further. This resulted in consumption and investment being postponed. Normally, low interest rates would have sent an investment signal. However, since people expected that the real debt burden would increase over time due to falling wages and profits, they renounced consumption or investment ( savings paradox ).

Concrete economic policy recommendations

Keynes, like Friedrich August von Hayek, had foreseen an economic crisis. However, based on the theory of the Austrian School, Hayek viewed the 1920s as a (credit) inflation period. The theoretically based expectation was that prices should have fallen due to the increased production efficiency. As a result, Hayek advocated a contractionary monetary policy by the US Federal Reserve to initiate mild deflation and recession that should restore equilibrium prices. His opponent Keynes contradicted this. In July 1928 he stated that although there were speculative bubbles on the stock exchange, the decisive indicator for inflation was the commodity index and it did not indicate any inflation. In October 1928, faced with several increases in the discount rate by the US Federal Reserve, Keynes warned that the risk of deflation was greater than that of inflation. He explained that a prolonged period of high interest rates could lead to depression. The speculative bubbles on Wall Street would only mask a general tendency for corporate underinvestment. According to Keynes' analysis, the longer period of high interest rates meant that more money was saved or invested in purely speculative investments and less money flowed into operational investments, because some prices such as wages, leases and rents are not very flexible downwards, so high interest rates are initially only reduce operational profits. In response to the deflation that actually set in a little later , Keynes advocated moving away from the gold standard in order to enable an expansionary monetary policy . Keynes' monetary policy analysis gradually gained acceptance, but his fiscal policy analysis remained unused during the global economic crisis.

Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz (Monetarism)

For a long time after 1945, Keynes' declaration determined the interpretation of the world economic crisis. In the 1970s, monetarism became the predominant explanatory model. Like John Maynard Keynes, monetarism attributes the global economic crisis to the restrictive policies of the central banks and thus to a wrong monetary policy. According to this view, it is not the overall economic demand but the regulation of the money supply that is the most important variable for controlling the economic process. Unlike Keynesians, they therefore consider monetary policy to be sufficient and reject deficit spending .

The most detailed monetarist analysis is A Monetary History of the United States (1963) by Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz , which blames the Federal Reserve for making the Depression so deep and long. One of the mistakes was that the Fed

- the V. a. the contraction of the money supply ( deflation ) caused by the banking crisis from 1929 to 1931 and did nothing

- in addition, the high interest rate policy of October 1931 as well

- the high interest rate policy from June 1936 to January 1937.

According to this, the numerous bank failures from 1930 to 1932 destabilized the economy, because on the one hand the customers lost a large part of the money invested and because the bank money creation function of the banks was significantly disrupted. In the US, this led to a 30% reduction in the money supply between 1930 and 1932 (“great contraction”), which triggered deflation . In this situation, the Federal Reserve should have stabilized the banks, but did not. The monetarist view of the Great Depression is largely believed to be correct, but some economists do not believe that it is sufficient on its own to explain the severity of the Depression.

Common position of Keynesianism and monetarism

From the point of view of the economics schools that dominate today, governments should strive to keep the related macroeconomic aggregates of money and / or aggregate demand on a stable growth path. During a depression, the central bank is supposed to provide liquidity to the banking system, and the government is supposed to cut taxes and increase spending to keep the nominal money supply and aggregate demand from collapsing.

In 1929–32, during the slide into the Great Depression, the US government under President Herbert Hoover and the US Federal Reserve (Fed) did not. It is widely believed that the impact of the liquidation thesis on some Fed decision-makers was catastrophic . President Hoover wrote in his memoir:

“The leave-it-alone liquidationists headed by Secretary of the Treasury Mellon… felt that government must keep its hands off and let the slump liquidate itself. Mr. Mellon had only one formula: 'Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate'… 'It will purge the rottenness out of the system. High costs of living and high living will come down. People will work harder, live a more moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up the wrecks from less competent people. '”

“The leave-the-economy-to-itself liquidators were led by Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon [... They] believed that the government should stay out of the way and that the economic downturn should unwind. Mr Mellon kept saying, 'Liquidate jobs, liquidate capital, liquidate farmers, dispose of real estate [...]. That will flush the rot out of the system. High cost of living and a high standard of living will adapt. People will work harder and lead more moral lives. Values will adjust and enterprising people will take over the ruins that less competent people have left behind. '"

Between 1929 and 1933, the liquidation thesis was the predominant economic policy concept worldwide. Many public decision-makers (e.g. Reich Chancellor Heinrich Brüning ) were essentially shaped by their belief in the liquidation thesis and decided not to actively fight the severe economic crisis.

Before the Keynesian Revolution in the 1930s, the liquidation thesis was widespread among contemporary economists and was particularly advocated by Friedrich August von Hayek , Lionel Robbins , Joseph Schumpeter, and Seymour Harris . According to this thesis, depression was good medicine. The function of a depression was therefore to liquidate bad investments and companies that operated with outdated technology in order to free the production factors capital and labor from this unproductive use, so that they would be available for more productive investments. They referred to the United States' brief 1920/1921 Depression and argued that the Depression laid the foundation for the strong economic growth of the later 1920s. As in the early 1920s, they also advocated a policy of deflation at the beginning of the Great Depression . They argued that even large numbers of corporate bankruptcies should be tolerated. Government intervention to alleviate the depression would only delay the necessary adjustment of the economy and increase social costs. Schumpeter wrote that

“… Leads us to believe that recovery is sound only if it does come of itself. For any revival which is merely due to artificial stimulus leaves part of the work of depressions undone and adds, to an undigested remnant of maladjustment, new maladjustment of its own which has to be liquidated in turn, thus threatening business with another [worse] crisis ahead. "

“We believe that economic recovery will only be solid if it comes by itself. Every revival of the economy, which is based solely on artificial stimulation, leaves part of the work of the Depression undone and leads to further undesirable developments, new undesirable developments of their own, which in turn have to be liquidated and this threatens the economy into another, [worse] crisis fall."

Contrary to the liquidation thesis, the economic capital was not only reallocated during the Great Depression, but a large part of the economic capital was lost in the first years of the Great Depression. According to a study by Olivier Blanchard and Lawrence Summers , the 1929-1933 recession caused accumulated capital to fall to pre-1924 levels.

Economists such as John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman believed that the policy recommendation of inaction resulting from the liquidation thesis exacerbated the Great Depression. Keynes attempted to discredit the liquidation thesis by describing Hayek, Robbins, and Schumpeter as "[...] strict and puritanical souls who see the [Great Depression ...] as an inevitable and desirable nemesis to economic 'over-expansion' - like them call - watch [...]. It would, in their view, be a victory for the mammon of injustice if so much prosperity were not offset by general bankruptcies that followed. They say that we - as they politely call it - need an 'extended liquidation phase' to get back on track. They tell us the liquidation is still ongoing. But in time it will be. And when enough time has passed to complete the liquidation, everything will be fine again [...] ”.

Milton Friedman recalled that the University of Chicago never taught such "dangerous nonsense" and that he could understand why at Harvard, where such nonsense was taught, smart young economists and Keynesians turned away from their teachers' macroeconomics were. He wrote:

“I think the Austrian business-cycle theory has done the world a great deal of harm. If you go back to the 1930s, which is a key point, here you had the Austrians sitting in London, Hayek and Lionel Robbins, and saying you just have to let the bottom drop out of the world. You've just got to let it cure itself. You can't do anything about it. You will only make it worse. ... I think by encouraging that kind of do-nothing policy both in Britain and in the United States, they did harm. "

“I think the Austrian School's overinvestment theory has done serious damage to the world. If you go back to the 1930s, which was a crucial point in time, you see the representatives of the Austrian School - Hayek and Lionel Robbins - sitting in London saying that things must be allowed to break down. You have to leave it to self-healing. You couldn't do anything about it. Anything you do would only make it worse. [...] I think that by encouraging inaction they have harmed both England and the United States. "

Newer developments

Debt deflation

Based on the purely monetary explanation by Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz and on The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions (1933) by Irving Fisher , Ben Bernanke developed the theory of the so-called credit crunch due to debt deflation as a non-monetary (real economic) extension of the monetarist one Explanation.

The starting point is Irving Fisher's observation that a fall in prices ( deflation ) leads to falling nominal incomes . Since the nominal amount of debt and the interest owed remain unchanged, this leads to an increase in the real debt burden. This can lead to a spiral of debt deflation: the increase in the real debt burden causes some debtors to go bankrupt. This leads to a decrease in aggregate demand and thus to a further decrease in prices (worsening deflation). This in turn leads to a further decline in nominal income and thus to an even greater increase in the real debt burden. This leads to further bankruptcies and so on.

Ben Bernanke expanded the theory to include the "credit view". If a borrower goes bankrupt, the bank will auction the collateral. Deflation also causes the prices of property, plant and equipment, real estate, etc. to fall. This leads to banks rethinking the risks of lending and consequently granting fewer loans. This leads to a credit crunch , which in turn leads to a decrease in aggregate demand and thus to a further decrease in prices (worsening deflation).

There is strong empirical validity that debt deflation was a major cause of the Great Depression. Almost every industrial nation experienced a phase of deflation between 1929 and 1933, during which wholesale prices fell by 30% or more.

Reflation policies are recommended as a solution to the debt deflation problem .

Importance of expectations

An impressive expansion of the monetarist perspective and the debt deflation effect is the additional modeling of expectations. The background to the expansion is that rational expectations have increasingly found their way into economic models since the 1980s and have been part of the economic mainstream since the widespread consensus for the new neoclassical synthesis . Thomas Sargent (1983), Peter Temin and Barry Wigmore (1990) and Gauti B. Eggertsson (2008) see the expectations of economic actors as an essential factor for the end of the global economic crisis. Franklin D. Roosevelt's assumption of office in March 1933 marked a clear turning point for American economic indicators. The consumer price index had been showing deflation since 1929 but turned into mild inflation in March 1933. Monthly industrial production, which had been falling steadily since 1929, showed a trend reversal in March 1933. A similar picture emerges on the stock exchange. There is no monetary reason for the turning point in March 1933. The money supply had fallen unabated up to and including March 1933. An interest rate cut had not occurred and was not to be expected, as short-term interest rates were close to zero anyway. What had changed were the expectations of entrepreneurs and consumers, because in February Roosevelt had announced the abandonment of several dogmas: the gold standard would in fact be abandoned, a balanced budget would no longer be sought in times of crisis and the restriction to minimal statehood would be abandoned. This caused a change in the expectations of the population: instead of deflation and a further economic contraction, people now expected moderate inflation, which would reduce the real burden of nominal interest rates, and economic expansion. The change in expectations resulted in entrepreneurs investing more and consumers consuming more.

A comparable change in political dogmas took place in many other countries. Peter Temin sees a similar, albeit weaker effect. For example, when the German government changed from Heinrich Brüning to Franz von Papen in May 1932. The end of Brüning's deflationary policy, the expectation of an economic policy, albeit a small one, and the successes at the Lausanne Conference (1932) caused a turning point in the economic data of the German Empire.

The hypothesis explicitly does not contradict Friedman / Schwartz's (or Keynes) analysis that a situation-appropriate monetary policy could have prevented the recession from sliding into a depression. In the global economic crisis, however, with nominal interest rates close to zero, the limit of a pure monetary policy was reached. Only a change in expectations was able to restore the effectiveness of monetary policy. In this respect, Peter Temin, Barry Wigmore and Gauti B. Eggertsson (contrary to Milton Friedman) see a positive effect of Roosevelt's (moderately) expansive fiscal policy, albeit mainly on a psychological level.

In 1937 there was a moderate tightening of monetary policy by the US central bank, motivated by the economic boom of 1933–1936, and a moderate tightening of fiscal policy by Roosevelt. This caused the recession of 1937/38, in which the gross domestic product fell more sharply than the money supply. According to a study by Eggertsson / Pugsley, this recession is mainly explained by an (erroneous) change in expectations that the political dogmas from before March 1933 would be restored.

International crisis export through the gold standard and protectionism

Gold standard

Some countries did not have a major banking crisis, but were plagued by deflation, a sharp drop in industrial production and a sharp rise in unemployment. It is almost unanimous that the gold standard acted as a transmission mechanism in these countries, which carried the US deflation and economic crisis across the world. Due to the gold standard that existed in the United States, many European countries and parts of South America at the time, the central banks had to hoard so much gold that every citizen could exchange their paper money for an equivalent amount of gold at any time.

- In the 1920s, many economies lost gold and foreign exchange due to large current account deficits in foreign trade with the United States. This was offset on the financial account side by an inflow of gold and foreign exchange due to extensive loans from the USA.

- At the turn of the year 1928/1929 the US Federal Reserve switched to a high interest rate policy in order to dampen the economy. The high interest rates in the USA meant that creditors preferred to invest their money in the USA and no longer lend money to other countries. In France, too, a restrictive monetary policy led to gold inflows. While a lot of gold flowed into the USA and France, the uncompensated outflow of gold and foreign exchange from some countries in Europe and South America threatened to make the gold standard there unreliable. These states were forced either to abandon the gold standard or to defend it through an even more drastic high interest rate policy and a drastic cut in public spending ( austerity policy ). This led to recession and deflation. The worldwide contraction of the money supply caused in this way was the impulse that triggered the world economic crisis beginning in 1929.

- The Great Depression was exacerbated by debt deflation and the severe banking crises in the early 1930s that led to the credit crunch and massive corporate bankruptcies. To combat the banking crisis, particularly the bank run-off , the central bank should have provided the banks with liquidity. For such a policy, however, the gold standard was an insurmountable obstacle. Unilateral economic policy measures to combat deflation and the economic crisis also proved impossible under the gold standard. The money supply expansion and / or countercyclical fiscal policy ( reflation ) initiatives in Great Britain (1930), the United States (1932), Belgium (1934) and France (1934-35) failed because the measures resulted in a deficit in the current account (and causing a gold outflow), which would have endangered the gold standard.

- Over time this was seen as a flaw in monetary policy. Little by little, all states suspended the gold standard and adopted a reflation policy . The almost unanimous view is that there is a clear temporal and substantive connection between the global move away from the gold standard and the beginning of the economic recovery.

protectionism

As a result of the global economic crisis, many countries switched to protectionist customs policies. Here the USA started with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of June 17, 1930, which resulted in a wave of similar tariff increases in the partner countries. Other states defended themselves against these protective tariffs by trying to improve their terms of trade in other ways : The German Reich, which was dependent on an active trade balance in order to be able to pay its reparations, pursued a deflationary policy that intensified the crisis from 1930 to 1932 , the United Kingdom started the currency war of the 1930s in September 1931 by decoupling the pound sterling from gold; the result was the end of the world monetary system that had been in effect until then. All these measures provoked new attempts by the partners to improve their trade balance. According to the economic historian Charles P. Kindleberger, all states acted according to the principle: Beggar thy neighbor - "ruin your neighbor as yourself". This protectionist vicious circle contributed to a considerable shrinkage of world trade and delayed the economic recovery (see also the competitive paradox ).

Comparison with the global economic crisis from 2007

The global economic crisis from 2007 was preceded by a long period in which no major economic fluctuations occurred (the period is called Great Moderation in English ). At this stage, economists and politicians overlooked the need to adapt the institutions created in the 1930s to avoid another crisis. In this way a shadow banking system emerged that evaded banking regulation. The deposit insurance was capped at $ 100,000 and that was nowhere near enough to cushion the 2007 financial crisis . In a short-sighted parallel to the banking crisis from 1929 onwards, the US government and the central bank believed that the Lehman Brothers investment bank could be allowed to go bankrupt because it was not a commercial bank and therefore there was no risk of insecure bank customers in a bank run of others Commercial banks could plunge into liquidity difficulties. A bank run by "ordinary bank customers" actually did not materialize. However, the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers triggered a bank run by institutional investors, whose deposits had exceeded the volume of the deposit insurance many times over. This bank run then quickly spread to the entire international financial system.

After the consequences of the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy shattered the international financial system, the governments and central banks reacted to the Great Depression from 2007 in a way that shows that they had learned from the mistakes made during the Great Depression from 1929. In an internationally coordinated action, the states increased government spending and lowered taxes. The central banks supplied the financial system with liquidity. The world economy experienced a severe recession and high unemployment, but the peak level of the world economic crisis from 1929 onwards was avoided.

In 2007 the USA and Europe also had a progressive tax system and a social security system, which, unlike in 1929, had a much larger volume and therefore acted as an automatic stabilizer to stabilize the economy.

literature

- Theo Balderston: The Origins and Course of the German Economic Crisis November 1923 to May 1932 . Haude and Spener, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-7759-0337-2 .

- Fritz Blaich: Black Friday. Inflation and economic crisis . dtv, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-423-04515-9 .

- Knut Borchardt : Growth, Crises, Scope of Action in Economic Policy. Studies on the economic history of the 19th and 20th centuries . Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 1982, ISBN 3-525-35708-7 .

- Karl Erich Born: The German banking crisis. Finance and politics . Piper, Munich 1967.

- Edward W. Bennett: Germany and the Diplomacy of the Financial Crisis, 1931. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (MA) 1962.

- Barry Eichengreen : Golden Fetters. The Gold Standard and the Great Depression, 1919-1939 . Oxford University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-19-510113-8 .

- John Kenneth Galbraith : The great crash of 1929. Causes, course, consequences. Munich 2005 (English original edition: Boston 1954), ISBN 3-89879-054-1 .

- Jan-Otmar Hesse , Roman Köster, Werner Plumpe : The Great Depression. The Great Depression 1929–1939 . Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2014, ISBN 978-3-593-50162-8 .

- Philipp Heyde: The end of the reparations. Germany, France and the Young Plan 1929–1932 . Schöningh, Paderborn [a. a.] 1998, ISBN 3-506-77507-3 .

- Carl-Ludwig Holtfrerich : Alternatives to Brüning's economic policy in the world economic crisis . In: Historical magazine . 235, 1982, pp. 605-631.

- Harold James : Germany in the Great Depression. 1924-1936 . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-421-06476-8 .

- ders .: The relapse. The new world economic crisis . Piper, Munich / Zurich 2003, ISBN 3-492-04488-3 .

- ders. (Ed.): The Interwar Depression in an International Context (= writings of the Historisches Kolleg . Colloquia 51). Munich 2002, XVII, 192 pp. ISBN 978-3-486-56610-9 ( digitized version ).

- Charles P. Kindleberger : The Great Depression . 1929-1939 . dtv, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-423-04124-2 .

- Rainer Meister: The great depression. Constraints and room for maneuver in economic and financial policy in Germany 1929–1932. Transfer-Verlag, Regensburg 1991, ISBN 3-924956-74-X .

- Florian Pressler: The first world economic crisis. A Little History of the Great Depression. Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-64535-8 .

- Philipp Reick: A Poor People's Movement ?, Unemployment protests in Berlin and New York in the early 1930s , in: Yearbook for Research on the History of the Labor Movement , Issue I / 2015.

- Albrecht Ritschl : Germany's crisis and economic situation 1924-1934. Domestic economy, foreign debt and reparation problem between Dawes plan and transfer lock . Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-05-003650-8 .

- Murray N. Rothbard : America's Great Depression . Princeton 1963, ISBN 0-945466-05-6 .

Web links

- Literature on the global economic crisis in the catalog of the German National Library

- The world economic crisis in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG ) with video; 1:29 min

- Michael Heim: Shares on waste paper . one day , March 18, 2008

- Reiner Zilkenat : “The enemy is on the left!” - The year 1929: Capital offensive against democracy and the labor movement

- Reiner Zilkenat : The year 1931 - The Weimar Republic at a crossroads

Remarks

- ↑ Kindleberger 1973, p. 39; Pressler 2013, p. 29.

- ↑ Quotation from Pressler 2013, p. 30.

- ^ Matthias Peter: John Maynard Keynes and the British policy on Germany. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 1997, ISBN 978-3-486-56164-7 , p. 61.

- ^ Kindleberger 1973, p. 56.

- ↑ Galbraith 2005, p. 56.

- ↑ Quotation from Pressler 2013, pp. 17-21.

- ↑ "The whole year round 920,550,032 shares were traded on the New York Stock Exchange - for comparison the sum of the previous record year 1927: 576,990,875 shares." (Galbraith 2005, p. 51.)

- ↑ Galbraith 2005, p. 103.

- ↑ Kindleberger 1973, p. 71 f.

- ↑ Galbraith 2005, pp. 125-127.

- ↑ Galbraith 2005, p. 136.

- ↑ Galbraith 2005, p. 180 f.

- ↑ Philipp Reick: A Poor People's Movement ?, unemployment protests in Berlin and New York in the early 1930s , in: Yearbook for Research on the History of the Labor Movement , Issue I / 2015.

- ↑ Pressler 2013, pp. 138–142.

- ↑ Randall E. Parker, Reflections on the Great Depression. Elgar publishing, 2003, ISBN 978-1-84376-335-2 , p. 11.

- ↑ Ben Bernanke : Non-monetary effects of the financial crisis in the propagation of the Great Depression . In: American Economic Review . Am 73 # 3, 1983, pp. 257-276.

- ↑ a b Randall E. Parker: Reflections on the Great Depression. Elgar publishing, 2003, ISBN 978-1-84376-335-2 , p. 11.

- ↑ Monika Rosengarten: The International Chamber of Commerce. Economic policy recommendations during the Great Depression, 1929–1939. Berlin 2001, ( online on Google Books ) p. 304.

- ^ Reiner Clement, Wiltrud Terlau, Manfred Kiy: Applied macroeconomics. Macroeconomics, economic policy and sustainable development with case studies. Munich 2013, ( online on Google Books ) p. 325.

- ↑ a b Randall E. Parker: Reflections on the Great Depression. Elgar publishing, 2003, ISBN 978-1-84376-335-2 , p. 13 f.

- ^ Gerhard Schulz : From Brüning to Hitler. The change in the political system in Germany 1930–1933 (= between democracy and dictatorship. Constitutional policy and imperial reform in the Weimar Republic. Vol. 3). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1992, ISBN 3-11-013525-6 , p. 402.

- ^ Arnold Suppan : Yugoslavia and Austria 1918–1938. Bilateral foreign policy in the European environment . Verlag für Geschichte u. Politics, Vienna 1996, ISBN 3-486-56166-9 , pp. 1047f.

- ^ Joachim Beer: The functional change of the German stock exchanges in the interwar period (1924-1939) . Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1999, p. 225.

- ^ Kindleberger 1973, p. 43.

- ↑ Pressler 2013, p. 44.

- ↑ Pressler 2013, p. 111.

- ↑ Pressler 2013, pp. 115–117. "As early as 1934, Great Britain's gross domestic product was back above the 1929 value."

- ↑ Jean-Jacques Becker and Serge Berstein: Victoire et frustrations 1914-1929 (= Nouvelle histoire de la France contemporaine, Vol. 12). Editions du Seuil, Paris 1990, pp. 279-283.

- ↑ Philipp Heyde: The end of the reparations. Germany, France and the Young Plan 1929–1932. Schöningh, Paderborn 1998, p. 59.

- ↑ Dominique Borne and Henri Dubief: La crise des années 30 1929-1938. (= Nouvelle histoire de la France contemporaine, vol. 13). Editions du Seuil, Paris 1989, pp. 21-26.

- ↑ Pressler 2013, pp. 118–120.

- ↑ Pressler 2013, pp. 121–125.

- ↑ Pressler 2013, pp. 160–165.

- ↑ Pressler 2013, pp. 166–169.

- ↑ a b c d e f Christina Romer : Great Depression . ( Memento from December 14, 2011 on WebCite ) (PDF; 164 kB) December 20, 2003.

- ^ Barry Eichengreen: US unemployment: some lessons in sharing from the Great Depression. The Guardian, June 12, 2012, accessed February 16, 2017 .

- ↑ Monthly report of the military economic staff on the “state of the economic situation. 1.2.1938 “BA-MA Wi IF 5/543. taken from: Friedrich Forstmeier, Hans-Erich Volkmann (Hrsg.): Economy and armaments on the eve of the Second World War . Düsseldorf 1981, p. 85.

- ↑ destatis.de ( Memento from November 14, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Karl Erich Born: The Black Friday : "The turning point from upswing to downswing occurred in Germany in 1928." In: Die Zeit (1967).

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : Deutsche Gesellschaftgeschichte, Vol. 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states 1914–1949 CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2003, p. 709; Werner Plumpe: Economic crises. Past and present, Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60681-6 , p. 86.

- ↑ Mark Spoerer, Dismantling a Myth? On the controversy about the National Socialist “economic miracle”, in: Geschichte und Gesellschaft, 31st year, no. 3, Südasien in der Welt (July – September, 2005), pp. 415–438, here pp. 433–435.

- ↑ According to Knut Borchardt a "nonsensical conception": The National Socialist Economic Policy 1933–1939 in the Light of Modern Theory by René Erbe Review by: Egon Tuchtfeldt , FinanzArchiv / Public Finance Analysis, New Series, Vol. 21, No. 1 (1961), Pp. 176-178.

- ↑ Ordinance to stimulate the economy of September 4, 1932 .

- ↑ The National Socialist Economic Policy 1933–1939 in the Light of Modern Theory by René Erbe, Review by: Knut Borchardt, Year Books for National Economy and Statistics, Vol. 171, No. 5/6 (1959), pp. 451-452.

- ↑ Robert Whaples: Where Is There Consensus Among American Economic Historians? The Results of a Survey on Forty Propositions. In: Journal of Economic History. Vol. 55, No. 1 (March 1995), pp. 139-154, here p. 151 in JSTOR.

- ↑ Robert Whaples: Where Is There Consensus Among American Economic Historians? The Results of a Survey on Forty Propositions. In: Journal of Economic History. Vol. 55, No. 1 (March 1995), pp. 139-154, here p. 151 in JSTOR.

- ↑ Robert Whaples: Where Is There Consensus Among American Economic Historians? The Results of a Survey on Forty Propositions. In: Journal of Economic History. Vol. 55, No. 1 (March 1995), pp. 139-154, here p. 151 in JSTOR.

- ↑ Robert Whaples: Where Is There Consensus Among American Economic Historians? The Results of a Survey on Forty Propositions. In: Journal of Economic History. Vol. 55, No. 1 (March 1995), pp. 139-154, here p. 151 in JSTOR.

- ↑ Gottfried Bombach, Hans-Jürgen Ramser, Manfred Timmermann, Walter Wittmann : The Keynesianism I: Theory and Practice of Keynesian Economic Policy. Springer-Verlag, 1976, ISBN 978-3-540-07910-1 , p. 15.

- ^ A b Lawrence H. White: Did Hayek and Robbins Deepen the Great Depression? In: Journal of Money, Credit and Banking . No. 40 , 2008, p. 751-768 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1538-4616.2008.00134.x .

- ^ Murray N. Rothbard : America's Great Depression . 1963.

- ↑ a b c Randall E. Parker: Reflections on the Great Depression. Elgar publishing, 2003, ISBN 978-1-84376-335-2 , p. 9.

- ↑ Hans-Helmut Kotz: The return of the cycle - and the new debate about stabilization policy . (PDF; 106 kB) In: Wirtschaftsdienst , Volume 82 (2002), Issue 11, pp. 653–660.

- ↑ John Cunningham Wood, Robert D. Wood: Friedrich A. Hayek. Taylor & Francis, 2004, ISBN 978-0-415-31057-4 , p. 115.

- ^ Lawrence White, The Clash of Economic Ideas: The Great Policy Debates and Experiments of the 20th Century . Cambridge University Press, p. 94; Lawrence White, Did Hayek and Robbins Deepen the Great Depression? In: Journal of Money. Credit and Banking, Edition 40, 2008, pp. 751–768, doi: 10.1111 / j.1538-4616.2008.00134.x

- ↑ Gottfried Bombach, Hans-Jürgen Ramser, Manfred Timmermann , Walter Wittmann: The Keynesianism I: Theory and Practice of Keynesian Economic Policy. Springer-Verlag, 1976, ISBN 978-3-540-07910-1 , p. 15 f.

- ↑ Paul S. Boyder: The Oxford Companion to United States History. Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-19-508209-5 , pp. 20 f.

- ^ Peter Clemens: Prosperity, Depression and the New Deal: The USA 1890-1954. Hodder Education, 2008, ISBN 978-0-340-96588-7 , p. 106.