New Deal

The New Deal was a series of economic and social reforms that were implemented from 1933 to 1938 under US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in response to the Great Depression. It represents a major upheaval in the economic, social and political history of the United States . The numerous measures have been divided by historians into those that should alleviate the need in the short term ( English relief , relief), into measures that stimulate the economy should ( recovery 'recovery'), and in long-term measures ( reform 'reform'). Aid for the numerous unemployed and poor fell under relief , under recovery among other things the change in monetary policy and under reform, for example, the regulation of the financial markets and the introduction of social security .

The question of how successful the New Deal was is still controversial today. The desperate state of the American economy could be overcome; on the other hand, full employment was not achieved until 1941. The Social Security Act of 1935 laid the cornerstone of the American welfare state, but social security for all and a “fair” distribution of income and wealth were not achieved. It is undisputed that the state with its massive intervention policy gave new hope to a discouraged and disoriented nation. Unlike in the German Reich and in many other countries, democracy in the United States was preserved during the global economic crisis. The market economy was saved by creating a more stable economic order , primarily through regulation of the banking system and securities trading .

Since the New Deal, liberalism in the United States has been associated with pro-worker policies rather than the defense of entrepreneurial freedom. Since the 1960s, “liberals” have been those citizens and politicians who refer to the tradition of the New Deal, pursue employee-friendly policies and advocate the extension of civil rights.

New Deal is an English expression and means something like "redistribution of cards ". Roosevelt initially used the phrase in the presidential election campaign of 1932 only as a suggestive slogan. New Deal then prevailed as a term to denote economic and social reforms.

Prehistory (1929–1933)

Financial and economic crisis

Beginning with the stock market crash of 1929 ( Black Thursday ) the world economic crisis developed , which reached its climax in 1932/33. Alongside the German Reich, the United States was one of the worst hit countries. Between 1929 and 1933, the gross domestic product almost halved. As a result of the financial crisis, 40% of the banks (9,490 of the original 23,697 banks) had to be wound up due to insolvency. The agricultural sector was also in crisis, with a large number of farmers unable to pay the interest on loans. In addition, the Great Plains were ravaged by the Dust Bowl period from 1930 to 1938 , in which many villages and farms were buried in dust. As a result of the Dust Bowl, 2.5 million people had to give up their farms.

The unemployment rate rose from 3% in 1929 to 24.9% in 1933. Many companies tried to avoid layoffs by reducing working hours. In 1931, every third employee had to make do with part-time work, with significant wage cuts. At that time there was no social safety net in the United States, especially no public unemployment insurance or public pension insurance. Some employers and unions had private unemployment insurance for their workers, but this insurance covered less than 1% of workers and employees. There was also no deposit insurance fund. When thousands of banks went bankrupt, many citizens lost all their savings.

Since the states and the cities were legally obliged to ensure a balanced budget every year, they mostly responded to the sharply increased need for social assistance during the crisis by lowering the level of social assistance so that social assistance was only granted to the poorest of the poor. In 1932, only a quarter of the unemployed and their families received government support. In most cities, social assistance was based on the physical subsistence level; in Philadelphia, for example, support had to be reduced to a level at which only two thirds of the food needed to maintain health could be bought. Despite a significant overproduction of food, many parts of the country were suffering from famine and there were isolated deaths. Slums sprang up in many cities, known as Hooverville after the incumbent president .

Hoover Government Response

As a libertarian, President Herbert Hoover advocated the greatest possible state reluctance to regulate the economy and relied on the principle of citizens to help themselves . At first he hoped that the crisis would end by itself. From October 1930 he tried to alleviate the situation of the unemployed and their families by founding private aid organizations. The President's Emergency Committee for Employment and its successor organization, the President's Organization on Unemployment Relief, collected private donations that were distributed to those in need. The organizations succeeded in increasing the amount of private donations, but these sums were by no means sufficient to alleviate the hardship.

After the crisis worsened considerably in its third year (1931), Hoover switched strategies and opened a period of experimentation to look for possible solutions. In the 1932 presidential election campaign, he declared restoring confidence in the country's economic strength to be the greatest problem. This will most certainly happen again when the state can show a balanced budget again. The Revenue Act of 1932 brought about a significant tax increase. With this, Hoover wanted to ensure that the state no longer had to take out loans and thus no longer competed with private individuals who were desperate for loans. While maintaining the doctrine of state non-interference in the economy, he tried to get companies to take private initiatives against the recession ( voluntarism ). Initiatives such as the National Credit Association , with which strong banks were supposed to prop up weak ones, failed, however. Based on this experience, Hoover realized in his last year in office that voluntary solutions were not enough. With the founding of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation , he finally made bank bailouts a state task. He prevented Robert F. Wagner's legislative initiative to introduce public unemployment insurance, which was successful in Congress , by vetoing it as President . Reluctantly, he signed a compromise bill created by Congress that created $ 1.5 billion in job creation programs. The money was used, among other things, for the construction of the Hoover Dam .

Roosevelt's election campaign (1932)

Franklin D. Roosevelt's political program remained fuzzy and unclear during the election campaign, but his general stance was well known. Like his cousin Theodore Roosevelt , who had been President of the United States from 1901 to 1909, he was also a progressive . In his opinion, the state should intervene wherever it was necessary in the public interest. His endeavor was to guarantee the middle and lower classes of society a minimum of economic security, a security that was a matter of course for the upper class, to which Roosevelt as a "patrician" belonged from birth. As governor of New York, he was one of the first to react to the depression with a courageous emergency program and to set up public work programs. This enabled him to present himself as a clear alternative to Hoover in the election campaign.

In his nomination speech in 1932 he spoke for the first time of a "New Deal":

“Throughout the nation men and women, forgotten in the political philosophy of the Government, look to us here for guidance and for more equitable opportunity to share in the distribution of national wealth ... I pledge myself to a new deal for the American people . This is more than a political campaign. It is a call to arms. "

“All over the nation, men and women who have been forgotten by the political philosophy of government look to us for leadership and a fairer chance to share in the national prosperity. I pledge to redistribute the cards for the American people. This is more than a political campaign. It's a call to arms. "

Like Hoover, he did not want to give up the goal of a balanced budget. He spoke out in favor of significantly increasing taxes so that the subsistence level of every citizen could be secured. He was of the opinion that the deeper problem lay in an overly unequal distribution of purchasing power, coupled with an excess of speculative investment.

“Do what we may to inject life into our ailing economic order, we cannot make it endure for long unless we bring about a wiser, more equitable distribution of national income ... the reward for a day's work will have to be greater, on average, than it has been, and the reward for capital, especially capital that is speculative, will have to be less. "

“Whatever we do to breathe life into our ailing economic order, we cannot achieve this in the long term unless we achieve a more meaningful, less unequal distribution of national income ... the wages for work one day must - on average - be higher than now , and the profit from assets, particularly speculatively invested assets, must be lower. "

On July 2, 1932, the day he was nominated as a Democratic presidential candidate, Roosevelt promised a "new deal for the American people," a term that later became popular to denote the reforms he carried out.

The Brain Trust

In the 1932 election campaign, Roosevelt presented his Brain Trust for the first time . It was an open group of economists and legal experts to advise Roosevelt. Founding members were the professor of law Raymond Moley , the economist Rexford Tugwell , the professor of law Adolf Augustus Berle , the judge Samuel Rosenman , the lawyer Basil O'Connor and the general Hugh S. Johnson . These advisors did not agree on all issues, but there was consensus on the general direction of the policy recommendations. First, they assumed that both the causes and the remedies for the depression were to be found in the United States itself. This differentiated them from the Hoover government, which saw the causes in Europe and part of the solution in protectionism. Tugwell explained the cause of the Great Depression in terms of underconsumption theory with the fact that wage increases in the 1920s remained below the productivity increase, so that the goods produced were no longer in sufficient demand. This analysis also influenced some of Roosevelt's speeches. Second, they were all progressives; they assumed that the concentration of economic power in large corporations made it necessary to strengthen state regulation. Berle and Tugwell in particular had dealt intensively with competition law and, in particular, antitrust law. For the later phase, the Second New Deal, Felix Frankfurter and Louis Brandeis , who are more in the tradition of anti-trust legislation for the unbundling of trusts , also became influential.

On February 22, 1933, Roosevelt asked the committed social politician Frances Perkins to take over the Ministry of Labor. She agreed on the condition that she could campaign for a ban on child labor , the creation of a pension scheme and the introduction of minimum wages . Roosevelt agreed, but insisted that she couldn't expect much help from him. She became the United States' first female minister and was one of the few ministers to hold office for three terms. With the support of Robert F. Wagner in particular , she succeeded in laying the foundation stone of the American welfare state against considerable resistance.

Development of the New Deal

Historians distinguish between a first phase (“First New Deal” - 1933 to 1934) and a second phase (“Second New Deal” - 1935 to 1938). The "First New Deal" addressed the most pressing economic and social problems facing the troubled economy. The “Second New Deal” mainly comprised longer-term measures.

Another common division is the division into measures that should make the social situation of people a bit more bearable in the short term (relief), into those that should bring about an economic recovery (recovery) and into measures that should bring about an improvement in the longer term through structural changes (reform ).

First New Deal (1933-1934)

100-day program

After winning the 1932 presidential election , Roosevelt took office on March 4, 1933. At that time, the citizens feared that all attempts to overcome the crisis could fail because of the political system of the United States, in which every initiative is very dependent on cooperation due to the American style of checks and balances . The influential journalist Walter Lippmann saw the greatest danger at the time not so much in the fact that Congress might give Roosevelt too much power, but more in that it would be denied the necessary support. But these fears were unfounded. In a first special session of the 73rd Congress from March 9 to June 15, the so-called "100-day program", Roosevelt managed to pass a number of fundamental laws. Due to the general longing for an end to the crisis, Roosevelt was able to work through the 100-day program in an unprecedented climate of bipartisan approval. This gave US citizens new confidence and the United States recovered from the near collapse.

“At the end of February we were a congeries of disorderly panic-stricken mobs and factions. In the hundred days from March to June we became again an organized nation confident of our power to provide for our own security and to control our own destiny. "

“At the end of February we were a mix of disordered, panic-stricken rabble and splinter groups. In the 100 days from March to June, we became an organized nation again with the confidence that we could look after our own security and control our own fate. "

Banking system reform

From 1929 on, the US financial system was destabilized by bank runs . These came about because it became known that many banks had accumulated bad loans or made heavy losses in investment banking. Fearing for their assets, many bank customers then tried to withdraw their bank deposits, which led to bank insolvency and bankruptcy because they could not make long-term money immediately available. Bank runs were often based on rumors, so that even relatively healthy banks could fall victim to such a development. Because more and more citizens were hoarding their money at home as a precaution, the banks had less and less money at their disposal. A credit shortage developed from this , which made the granting or extension of private and corporate loans often impossible. As a result, many private individuals and companies went bankrupt, which in turn exacerbated the banking crisis and caused great damage to the real economy. The economic damage caused by the collapse of the banking system was a major factor in the extraordinary length and severity of the Great Depression. As a measure against the bank runs, Hoover had already considered the bank holiday , but then rejected it because he feared it would cause a panic. Roosevelt, on the other hand, gave a speech over the radio that was held in the atmosphere of a fireplace chat and explained to the population in simple terms the causes of the banking crisis, what the government would do about it and how the population could help. Just two days after Roosevelt took office, on March 6, 1933, all banks were ordered to close for four days (bank holiday) . During this time it was examined which banks could be rescued by state lending and which had to close forever. During this time, the Emergency Banking Bill was passed, with which the banks were placed under the supervision of the United States Department of the Treasury . With these measures it was possible to restore the confidence of the citizens in the banking system in the short term: Immediately after the banks reopened, the deposit level increased by a billion dollars.

In addition to the bank runs, the legislature saw the high level of involvement of many banks in volatile securities transactions as further reasons for the banking crisis, which had caused losses that threatened their existence with the sudden fall in value in the wake of the stock market crash of 1929. Furthermore, in the 1920s the banks had made an unusually large number of risky loans. It has been suggested that the high risk appetite of many banks was also due to the fact that they were able to sell low-quality securities, in particular loans with a high risk of default, to less well-informed bank customers. The legislature wanted to put a stop to the presumed internal bank conflict of interest, on the one hand to advise customers well and on the other hand to achieve the highest possible profits with their own securities transactions. After the banks reopened, the Glass-Steagall Act was passed. With this law the separate banking system was introduced. Commercial banks were banned from risky securities transactions. The commercial banks' lending and deposit business, which is important for the real economy, should thus be separated from risky securities transactions that will in future be reserved for specialized investment banks . The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation was also established. This deposit protection fund guaranteed the bank customers a payment of the bank deposits in the event of a possible bankruptcy of a commercial bank. (Investment banks, however, were excluded from this state guarantee). These measures further increased confidence in the financial system. In the period that followed, there were no more bank runs. The regulations also brought unprecedented stability to the American banking system: while even in the period before the Great Depression more than five hundred banks collapsed each year, after 1933 it was less than ten per year. The Glass-Steagall Act was repealed in 1999, but experienced a renaissance in the 2007 financial crisis .

Financial market regulation

Before 1933, Wall Street traded stocks for which no reliable information was available. Many companies refrained from regularly publishing annual reports or only published selected data, which tended to mislead investors. To stop the kind of wild speculation that led to the stock market crash of 1929, the Securities Act of 1933 was passed. With this law, securities issuers were obliged to provide realistic information about their securities. In 1934 the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) was created, which has since supervised US securities transactions. These measures increased Wall Street's credibility .

Monetary policy

Due to the gold standard that existed at the time, i.e. the link between the dollar and the gold price, the US Federal Reserve ( FED) had to hold so much gold that every citizen could exchange their dollars for an equivalent amount of gold at any time. During the years of the recession (1929–1933), the FED should have pursued an expansive monetary policy in order to combat deflation and stabilize the banking system. However, due to the automatic gold mechanism , a countercyclical monetary policy was not possible, because a reduction in the key interest rate would have led to a relative decline in gold reserves. The FED only had the choice of either giving free rein to deflation and the banking crisis, or abandoning the gold standard in favor of an expansive monetary policy, and opted for the former. After monetarist analysis of the 1960s, the contraction of the in-depth money supply , the recession , the response of the Fed is now considered serious mistake. In the 1930s, however, this connection was still insufficiently known; the first criticism of the effects of the gold standard came from economists such as John Maynard Keynes . To end deflation and expand the money supply, the Roosevelt administration took measures that had already been successfully applied in Europe. The export and private ownership of gold and silver were banned, larger gold holdings had to be sold to the FED for $ 20.67 an ounce ( Executive Order 6102 ). The Gold Reserve Act of 1934 set the price of gold (well above the market price) at $ 35 an ounce. With the ounce of gold now costing more dollars, the increase in the price of gold caused the dollar to depreciate to 59% of its last official value. The devaluation of the dollar meant that foreigners could buy 15% more American goods, thus promoting exports ( Beggar thy neighbor ). These measures resulted in a de facto departure from the gold standard.

Measures against deflation

The idea of obliging entrepreneurs to refrain from unfair price undercutting and lay off workers on a voluntary basis originally came from President Hoover. This wanted to fight deflation in this way . This idea was picked up by Roosevelt, but should be implemented much more consistently. For this purpose, the National Recovery Administration (NRA) was founded in June 1933 . It was led by Hugh S. Johnson . In cooperation with business representatives, the NRA developed a catalog of behavior that entrepreneurs could voluntarily commit to. This included the renunciation of unfair (price) competition, minimum prices, minimum wages, the recognition of trade unions, the introduction of the 40-hour week, etc. This catalog of behavior was intended to strengthen the bargaining power of trade unions and control market competition. The idea behind was that this would stabilize prices and wages and consequently curb deflation. This should enable companies to recruit workers. However, the self-commitment was in fact not entirely voluntary. The participants in the program were allowed to wear the Blue Eagle in their shop windows and on their goods . the symbol of the NRA, advertise. Companies that could not advertise with this symbol ran the risk of being boycotted by customers. Many smaller firms also complained that it was much easier for larger firms to pay the minimum wage. Shortly before the end of the two-year program, the NRA was declared unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court in 1935 and had to cease operations.

Farmers' incomes had fallen steadily since the mid-1920s, by 60% between 1929 and 1933 alone. A number of aid measures had been designed in Congress for a long time, e. B. Subsidizing exports. Herbert Hoover had suggested the formation of co-operatives to reduce investment costs and running costs, while still others had suggested state purchases and destruction of food. As in industry, Roosevelt wanted to stop the fall in prices in agriculture. Aid was decided for farmers who reduced their production. This should stabilize the prices for agricultural products. The US government granted the farmers funds for this under the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) of May 12, 1933. The originator of this idea was Rexford Tugwell , who argued that preventing overproduction was cheaper for the state than buying it later the destruction of excess food. The prices soon stabilized. However, an undesirable side effect of the measure was that large landowners increased the productivity of their farms by firing tenants. The AAA was also declared unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court in 1936. Also because the law was very popular with the rural population, the AAA was reformed and re-enacted with regard to the objections of the Supreme Court . It essentially still exists today.

Other aids to farmers

The farmers' debt crisis should be alleviated with the Emergency Farm Mortgage Act . The Farm Credit Administration , founded in 1933, organized the debt restructuring into longer-term low-interest loans. The Resettlement Administration , founded in 1935, organized the resettlement of farmers, especially those from the regions particularly affected by the Dust Bowl. It was replaced in 1937 by the Farm Security Administration , which provided assistance to farmers in need.

Social policy

In line with the attitude of most US citizens, the Roosevelt administration believed that it was better for work ethic to provide unemployment benefits through paid work. Due to the very high unemployment, job creation programs were set up to ease the situation in the short term (relief). The creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) created jobs for unemployed young men between the ages of 18 and 25 whose families received welfare benefits. The CCC was used for afforestation, fighting forest fires, building roads and fighting soil erosion. By 1942 the CCC employed a total of 2.9 million young men. For those US citizens who could not be offered work through the CCC, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration was established, which increased the state welfare payments by a third.

With regard to the public works demanded by the progressive wing of the Democrats, Roosevelt was reserved because unsuitable projects could quickly turn them into a relatively expensive form of poor relief. He demanded that only those projects should be tackled that were reasonably self-financed. The Minister of Labor, Frances Perkins , only managed to negotiate the budget up to $ 3.3 billion after several attempts. With this budget, the Public Works Administration led by Interior Minister Harold L. Ickes was founded, which was supposed to expand the infrastructure (roads, bridges, dams, school buildings, sewer systems), especially in underdeveloped regions. It was easier in energy policy, where Roosevelt saw longer-term economic benefits. With the Wilson Dam, completed in 1927, there was an early public construction project initiated by progressives, the use of which for power generation had previously been successfully sabotaged for ideological reasons with the help of Presidents Calvin Coolidge and Hoover. The dam has been a symbol of both hope and frustration among progressives. However, the Wilson Dam inspired Roosevelt and George W. Norris to found the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) in 1933 . The Tennessee Valley Authority acquired the Wilson Dam and had 20 more dams built in the Tennessee Valley by the Public Works Administration. These dams were supposed to prevent future floods, eradicate malaria and supply the hitherto underdeveloped region with electricity.

Housing policy

In terms of housing policy, there was basically a choice between public housing and the promotion of home construction. Unlike in most European countries, Roosevelt put the emphasis on home ownership. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), founded in 1934, insured bank home equity loans under certain circumstances. Before 1934, the situation was that banks only granted home equity loans for a short period of 5–10 years. In cases in which a guarantee from the FHA could be successfully applied for, banks granted lower-interest loans with terms of up to 30 years. In the period that followed, the number of homeowners increased from 4% to 66% of the population, which also boosted the construction industry. Due to the originally strict award criteria, it was primarily white middle-class families who benefited from home ownership. This policy has been criticized in part for the fact that the lower third of the population could not benefit from home ownership. In the 1990s, presidents George HW Bush , Bill Clinton and George W. Bush initiated a more generous allocation practice so that poorer families were also supported in buying a house. However, it turned out that a large part of these riskier loans went bad.

As part of the Second New Deal, the United States Housing Authority was founded in 1937 to eliminate slums through a public housing policy. But politics remained limited to helping the poorest of the poor.

Foreign trade policy

With the Fordney – McCumber Tariff of 1922, the United States had given up the principle of free trade in response to the recession of 1920/21. With the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, passed under the presidency of Hoover, a pronounced protective tariff policy was finally adopted. There is now a large consensus among historians and economists that the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act exacerbated the Great Depression. It was politically controversial from the start; in addition to many prominent scientists, Roosevelt had also spoken out against the law. At the instigation of Cordell Hull , the Reciprocal Trade Agreement Act was passed in 1934 . With this law, the Roosevelt government laid the first foundations for a tariff policy based on the principle of most-favored-nation treatment . American foreign trade was gradually liberalized again through the conclusion of bilateral trade agreements.

Second New Deal (1935-1938)

The period from 1935 to 1938 is often referred to as the Second New Deal. This phase was mostly about long-term solutions.

Political pressure on Roosevelt

After the 1934 congressional election , a so-called midterm election , which was very successful for the Democratic Party , Roosevelt was able to rely on an even larger democratic majority. At the same time, however, the political climate changed. Due to the severe economic crisis, the First New Deal had found widespread non-partisan support in public and in Congress. This unity, however, only hid the deep political differences that existed between Democrats and Republicans and within the Democratic Party. These broke out again when the economic situation brightened again. After the economy began to recover, wealthy business people in particular began to criticize the New Deal. They turned against state regulation of the economy, against the level of taxes, against the extent of social assistance and public employment programs. Conservative ("conservative") Democrats led by Al Smith , who was defeated in the Democratic Party's primary election to Roosevelt in 1932, founded the American Liberty League in 1934 , which had up to 36,000 members. With the financial support of numerous business people, the American Liberty League led a public campaign against the alleged radicalism of the New Deal. The society also supported a racist group that circulated images in the southern United States of the First Lady , known as a civil rights activist , with African Americans . A major financier of the American Liberty League was DuPont heir Irénée du Pont , who considered Roosevelt to be a "Jewish-controlled" communist. At the beginning of 1934, Du Pont and his brothers planned a coup against the president. When the designated general and New Deal opponent Smedley D. Butler informed Roosevelt, du Pont denied having anything to do with it. Criticism of the New Deal also came from the far left and right. The Communist Party USA , strengthened during the crisis, criticized the New Deal as an attempt to preserve capitalism. Charles Coughlin , classified by historians as a demagogue , who as a radio presenter had up to 30 million listeners, tried to found his own political career with anti-Semitic and anti-New Deal slogans.

Politically influential at this time were in particular some personalities who were sometimes referred to as populists. Francis Everett Townsend suffered the fate typical of older workers at the time of losing his job and financial reserves in the Great Depression and being unable to find new work. He promoted his Townsend Plan , which provided a state pension for all citizens over the age of 60. The plan was considered unfundable as it promised a retirement pension of $ 200 a month; this was therefore higher than the average wage. In addition, the pensions should be financed by a new sales tax, this type of financing would have burdened people with low incomes above average. Nevertheless, he was able to show 20 million supporters for his petition. Democratic Senator Huey Long initially supported the New Deal, but then turned away from Roosevelt in 1934, whose policies he considered inadequate. He founded the Share Our Wealth Society , which promised every American family an annual basic income of $ 2,000, which was to be financed by a radical taxation of high incomes and wealth. While the plan was not fiscally feasible, the society had 7 million members and there was no doubt that Long was up for a presidential run.

The successes of the populists showed Roosevelt on the one hand that there would be great support among the population for the more far-reaching measures against the depression and for social security advocated by parts of his think tank. On the other hand, they showed that political competition was not only to be feared from the conservatives. Many reform-minded MPs had been elected to Congress, and Roosevelt was determined to keep the initiative. He wanted to have the measures prepared and supported by his think tank become law before Congress passed laws on its own initiative that he might not be able to support. Some historians argue that Part Two of the New Deal came about only in response to pressure from the populists. According to David M. Kennedy, however, what speaks against this is that most projects were planned and prepared long before the populists' successes. Given the time perspective, only the Wealth Tax Act can be seen as the answer to the populist challenge.

Introduction of the welfare state

The Great Depression had hit older people particularly hard, who had above-average difficulties in finding work and who fell 50% below the poverty line. Until 1935 there were many individual social assistance programs of the federal states to alleviate poverty, which were topped up with federal subsidies. Until then, there was only unemployment insurance in the state of Wisconsin (introduced in 1932, effective from 1934). Public annuities were formally available in some states, but all of them were severely underfunded and practically meaningless. The lack of social security made the United States an exception among modern industrialized nations. Citizens suffered from this fact during the Depression. The introduction of a welfare state based on the European model was developed under the chairmanship of Frances Perkins . With its help, the social problems should be overcome. With the passage of the Social Security Act of 1935, the United States introduced the first social security schemes , such as Social Security , a widow's pension for dependents of industrial accidents and assistance for the disabled and single mothers. Federal subsidies were also introduced for the unemployment insurance schemes operated by the individual states. To finance this, a new tax (the payroll tax) was introduced, with which an employer's share and an employee's share are paid to the state treasury. Roosevelt had insisted on a separate tax so that the tax revenue could not be used for other purposes. The original Social Security Act fell short of many European models, among other things because Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau successfully intervened to ensure that farmers, domestic workers and the self-employed were not included in pension and unemployment insurance. Morgenthau argued that social security would become unaffordable if these sections of the population, as typical low-wage earners, also received insurance benefits. On the other hand, 65% of all blacks in the USA and between 70% and 80% in the southern states were in fact not covered by social security. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People called social security a safety net that "was like a sieve, with holes just big enough for the majority of blacks to fall through."

The introduction of a public health insurance was initially not a majority. Roosevelt hoped, however, that the Social Security Act could be expanded at a later date. With this law, fiercely opposed by opponents, a state responsibility for social security was established for the first time in the United States. The payroll tax was levied from 1937, and due to the pay-as-you-go system , the first pension payments (after a 3-year minimum contribution period) were made from 1940.

Employment Law

Unions existed long before 1935. Since most employers did not recognize unions, strikes were often violent, with strikers forcibly preventing scabs from entering the factory and employers hiring thugs to protect the factory and scatter strikers. Occasionally the police were used against strikers, or the state of emergency was declared by governors and the army was even used. There were more and more serious confrontations with many injured and sometimes even dead. In 1934, two union members were killed in one such confrontation in San Francisco. The local unions then called a general strike in which 130,000 workers took part. The president was concerned not only with the increasing radicalization of the labor disputes, but also with the influence of the Communist Party USA within the growing labor movements. An attempt to get trade unions recognized by employers on a voluntary basis through the National Recovery Administration (NRA) had become obsolete after the NRA was banned. Above all, Robert F. Wagner therefore pushed for legal recognition of the trade unions. The Wagner Act , passed in 1935 , gave workers the right to form trade unions and to bargain collectively for wages and conditions. Workers have not since been allowed to be fired for union membership. A formal right to strike was also introduced. Even after the passing of the Wagner Act, there were violent clashes. A final major highlight was the Memorial Day Massacre of 1937, when the Chicago police forcefully broke up a demonstration by working-class families. The National Labor Relations Board introduced with the Wagner Act succeeded in mediating more and more often in labor disputes. The number of unionized workers doubled to 7 million between 1929 and 1938. Much of the increase was due to the expansion of unionization to include the mass manufacturing industries with large corporations such as B. Ford or General Motors , who had previously successfully fought against unions. Strikes increased over a period of several years. The influence of employees on the level of wages and the structuring of working conditions increased.

In 1938 the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed, which set a minimum wage of 25 cents an hour and a working time limit of 44 hours a week. Furthermore, child labor was banned by children under the age of 16. In order to get the bill through Congress, in which Southern MPs formed a key faction, domestic workers and farm workers had to be exempted. The Roosevelt administration hoped to be able to extend the scope of the law to these professional groups at a more convenient time. After the law was passed, the wages of 300,000 people immediately increased and 1.3 million people worked less.

Labor market and economic policy

The economic recovery had started with the start of the New Deal and was also quite high, with economic growth averaging 7.7% per year, but the unemployment rate fell only slowly. The economist John Maynard Keynes also placed this development at the center of his considerations. He described the situation as equilibrium with underemployment . Keynes had tried several times to convince Roosevelt of an economic stimulus through deficit spending . From the outset, however, Roosevelt's Brain Trust was split between proponents of the strategy of combating the Depression through higher government spending and proponents of the strategy of achieving a balanced budget through budget cuts. The latter included, in particular, Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau. As a result, the United States failed to follow Keynes' recommended countercyclical fiscal policy between 1933 and 1941 . The measures against the depression, in particular the job creation programs, increased government spending. However, this was largely offset by other measures. A significant increase in income tax had already been passed under Hoover, which increased state revenue. In addition, when Roosevelt took office, he had implemented significant spending cuts, for example in pensions (Economy Act) . As a result, the budget deficit of the federal budget from 1933 to 1941 was around 3% per year. Arthur M. Schlesinger thinks that the Brain Trust was more open to the idea of a Keynesian economic policy during the Second New Deal than it was during the First New Deal. David M. Kennedy doubts that, such a development can hardly be attached to concrete politics.

| Unemployment rate in the year | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | 1936 | 1937 | 1938 | 1939 | 1940 | 1941 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Including people in job creation schemes | 24.9% | 21.7% | 20.1% | 16.9% | 14.3% | 19.0% | 17.2% | 14.6% | 9.9% |

| Workers in job creation programs were not counted as unemployed | 20.6% | 16.0% | 14.2% | 9.9% | 9.1% | 12.5% | 11.3% | 9.5% | 8.0% |

Roosevelt and his Brain Trust decided that unemployment would not go away as quickly as it erupted in 1929. They saw a need to extend the unemployment reduction measures. The 1935 Emergency Relief Appropriation Bill increased the budget for job creation by $ 4 billion. This offered paid work to 3.5 million able-bodied unemployed. The job creation measures had to be designed on instructions from Roosevelt so that the realized projects were labor-intensive and at the same time meaningful in the long term, and the workers had to be paid less than in the private sector. There were u. a. 125,000 public buildings, more than a million kilometers of highways and roads, 77,000 bridges, irrigation systems, city parks, swimming pools, etc. built. These included prominent projects such as the Lincoln Tunnel , the Triborough Bridge , New York-LaGuardia Airport , the Overseas Highway and the Oakland Bay Bridge . In addition to the Public Works Administration founded in 1933, the Works Progress Administration under the direction of Harry Hopkins was primarily responsible for this . The Rural Electrification Administration , founded in 1935 to supply rural regions with cheap electricity , also used these funds . In 1935 only 20% of American farms had access to electricity, ten years later the rate was already 90%.

Competition law

Large holding companies created some problems. For example, a few holding companies dominated the entire energy market. Many were also large enough to have a significant impact on legislation. At that time, the United States had many pyramidal, multi-tiered holdings. Here the operative part of the company had to generate excessively high profits in order to finance the various superordinate companies. The Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 required all holding companies to be registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). All holding companies of more than two levels that could not give any valid reasons for this structure were broken up .

Tax law

In 1935 the Wealth Tax Act was also passed, which raised the top income tax rate to 79%. The bill, however, was primarily intended to facilitate the election campaign for Roosevelt, as it was a response to the threat to the Democratic Party posed by the radical Huey Long and Charles Coughlin. Finance Minister Morgenthau described the Wealth Tax Act to tax officials as an election document, a law that was supposed to increase government revenues only marginally. The top tax rate of 79% was very high, but it should only be applied from a very high income. In fact, there was only one taxpayer who had to pay the top tax rate of 79% after the law was passed: John D. Rockefeller .

In 1936 a corporation tax was introduced with tax rates between 7% and 27%. In Congress , the law was weakened - smaller corporations were largely exempt from the regulations. Unlike the Wealth Tax Act, this bill focused on increasing tax revenue, as Congress had recently passed a bill on its own initiative that would allow the payment of outstanding WWI veterans bonuses - a total of $ 2 billion - from 1945 moved forward to 1936.

Constitutional change of 1937

When Roosevelt took office, the majority of the Supreme Court was made up of judges (for life) nominated by Republican presidents. In the 1920s and 1930s, four of the Supreme Court justices became known as the Four Horsemen of Reaction , who repeatedly managed to organize a majority (at least 5 of the 9 judges) that declared a number of progressive laws unconstitutional . On May 27, 1935 (Black Monday) , the first New Deal laws, including the work of the National Recovery Administration, were declared unconstitutional. At that point, Roosevelt was still hoping that one of the judges would retire and that the majority structure could be changed by a new judge nomination. After other laws, most notably the Agricultural Adjustment Act and the New York State Minimum Wage Act, were ruled unconstitutional in 1936, Roosevelt came to believe that the Supreme Court would cash out all essential parts of the New Deal and the principle of the separation of powers between the judiciary and Legislative in favor of the judiciary de facto undermined. Former President Hoover also criticized the decisions as too far-reaching interference with legislative powers. There was widespread public criticism (for example in the bestseller by Drew Pearson and Robert Allen with the title Nine Old Men ) that the judges, mostly over 70 years old, no longer recognized the problems of the present. Confirmed by the massive victory in the 1936 presidential election and angered by Judge McReynolds ' comment, "I will never retire while the crippled son of a bitch is in the White House," Roosevelt decided to make his judicial reform plans public in January 1937 . The Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937 was intended to give the US President the power to appoint additional judges for any judge over 70 who refused to retire. A sufficient majority of the Democratic MPs in the House of Representatives and Senate was behind the legislative initiative. But it was sharply criticized by the Republicans and some Democratic MPs as an interference in the separation of powers. In addition, Southern Democratic Party MPs feared progressive judges might critically review the separate-but-equal case law on segregation. At this point, beginning March 29, 1937 (White Monday), there was a change in the case law of the Supreme Court. Judge Owen Roberts , who had previously voted frequently with the Four Horsemen, now voted with the progressive wing of the court. The change was most evident in the judicial decision declaring the minimum wage law in Washington state constitutional - just a year earlier, the New York minimum wage law had been declared unconstitutional. The Wagner Act and the Social Security Act have also been declared constitutional. The historian David M. Kennedy assumes that the increasing public criticism of the jurisprudence practice of the Four Horsemen of Reaction and the landslide election victory of Roosevelt in November 1936 played a role in the change in jurisdiction. Despite this turnaround, Roosevelt tried to get the judicial reform bill through Congress, but failed. Due to the voluntary resignation of the Four Horsemen ( Van Devanter 1937, Sutherland 1938, Butler 1939 and McReynolds 1941) and three other judges, the Supreme Court could largely be re-appointed. After the phase of conservative jurisprudence, a longer phase of liberal constitutional jurisprudence began in 1937.

William Rehnquist summarized the constitutional change as follows:

"President Roosevelt lost the Court-packing battle, but he won the war for control of the Supreme Court ... not by any novel legislation, but by serving in office for more than twelve years, and appointing eight of the nine justices of the Court. ”

“President Roosevelt lost the battle for the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937, but he won the war for control of the Supreme Court ... not by new legislation, but by being in office for more than twelve years and so on after) was able to appoint eight of the nine judges of the Supreme Court. "

Aftermath of the New Deal

There have been no reform announcements since 1939. Since then, Roosevelt's endeavors have been to perpetuate the New Deal. From then on he referred to it as an "Economic Bill of Rights", which was to determine the political agenda even after the Second World War. The idea of stabilizing the incomes of workers, employees and farmers, regulating financial institutions and large corporations, setting up spending programs to expand infrastructure and creating jobs, and to bring about a certain redistribution of income through significantly higher taxation of the rich was another 30 For years a guideline for the Democratic Party, which was dominant at this time .

Change of the terms "liberal" and "conservative"

In 1941, Roosevelt defined liberal governments as those that advocate state intervention in times of need, while conservative governments generally oppose state intervention. With the redefinition of the term liberal, he referred to the philosopher John Dewey , who had pleaded for a new understanding of liberalism as early as 1935. This redefinition was taken over in the political discussions. Since then, liberalism in the United States has been associated less with the defense of entrepreneurial freedom than with worker-friendly policies. In the 1960s, Democratic Presidents Kennedy and Johnson added civil rights and minority policy to the New Deal program. Since then, citizens and politicians who refer to the tradition of the New Deal, pursue employee-friendly policies and advocate the expansion of civil rights have been considered “liberals”.

Allegations of radicalism and red scare tactics

In the early days of the New Deal, it was not clear to people whether there could be a clear democratic path beyond communism and fascism. They observed with concern that totalitarian regimes were spreading in Europe. This led some critics to assign the New Deal to this tendency. Some critics accused the New Deal of being "communist infiltrated" by some people or of being a fascist idea. The main point of reference cited was the National Recovery Administration's “war” against deflation . However, contrary to some speculation, this measure, limited to three years, was not based on Soviet or Italian ideas. Rather, it was loosely based on the War Industries Board, which was temporarily set up under Woodrow Wilson for the purpose of coordinating war industry ( war economy ) , to which Hugh S. Johnson also had personal continuity. Roosevelt had already countered the argument that the economic policy measures of the New Deal against deflation (and thus against the severe economic crisis) must lead straight to fascism, that the opposite was the case: the continuation of an economic policy that refrains from intervention would Finally deliver the USA to a dictatorship.

"Democracy has disappeared among various great peoples, not because these peoples reject democracy, but because they have grown tired of unemployment and insecurity, because they no longer wanted to watch their children starve while they sat helplessly and watched had to, how their governments were confused and weak ... We in America know that our democratic institutions are preserved ... But in order to preserve them we have to show that the practical work of democratic governance is to keep the people safe protect, has grown. "

Historians do not share charges of extremism. The fascism researcher Stanley Payne comes to the conclusion in A History of Fascism, 1914–1945 (1995) that the idea of fascism did not reach the United States and that pre-fascist aspects such as racism existed in the United States during the 1930s rather decrease instead of increase.

Historians have identified two main reasons for the attacks by a section of the Conservatives against liberals that resulted in the second wave of the Red Scare . For one, there was the overwhelming popularity of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the sudden enthusiasm for state interventionism in the population , which resulted in a continued democratic majority in Congress . On the other hand, conservatives had to watch helplessly as the social and economic conditions in the country changed dramatically within a few years, which they found deeply shocking. Many conservatives advocated a free (unregulated) market economy and saw state intervention in the economy as a fall from man.

New Deal consensus

Between 1940 and 1980 there was a New Deal consensus (or liberal consensus ) in the United States . The Fair Deal of the Democratic President Harry S. Truman brought above all an expansion of the social security systems introduced with the New Deal to 10.5 million previously uninsured citizens and an increase in insurance benefits by an average of 80%. Since 1940 the Republican Party has nominated Wendell Willkie and Thomas E. Dewey for those presidential candidates who are not hostile to the New Deal. Dwight D. Eisenhower was successful , who also supported the general New Deal consensus as president-elect. In a private letter, he explained his position as follows:

“Should any party attempt to abolish social security and eliminate labor laws and farm programs, you would not hear of that party again in our political history. There is a tiny splinter group of course, that believes you can do these things ... Their number is negligible and they are stupid. "

“Should a party try to abolish the Social Security Act, labor law and the farm programs, then this party would no longer be noticed in political history. There is, of course, a small splinter group that thinks they can do this ... However, their number is negligible and they are stupid. "

Also under the Republican President Eisenhower there was an expansion of social security and an increase in the minimum wage. Under the Democratic Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson a social policy followed in the tradition of the New Deal, with Johnson's Great Society program filling a major gap in the Social Security Act of 1935 with the introduction of public health insurance.

A first attempt by the Republican Party to break out of the New Deal consensus was the nomination of welfare opponent Barry Goldwater as a presidential candidate in the 1964 election . The presidential election ended in a clear defeat, which fueled speculation about the decline of the Republican Party. From the supporters of Goldwater, however, the New Right was formed , which sixteen years later contributed significantly to the election victory of Ronald Reagan . Since the 1980s, political disputes in the USA have always been shaped by the contrast between regulation and deregulation of the economy. It has also been demand policy officially rejected and pure supply-side policy touted as an alternative. The deregulation measures of President Reagan (see Reaganomics ) became particularly well known . At the same time, the Reagan administration increased armaments spending significantly, which, with its typical effects (economic recovery, increase in national debt), was a form of state demand policy.

Political metaphor

More recently, with reference to the New Deal, proposals have been made to overcome the economic difficulties created by the 2007 financial crisis . In the “World Economic and Social Survey 2008: Overcoming Economic Insecurity” of the United Nations , a global New Deal was proposed to overcome global economic difficulties. Within the United States, the left wing of the Democratic Party and the non-party former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg are calling for a New New Deal as a solution to the troubled American economy.

The concept of the Green New Deal also refers to the New Deal , with which various approaches to a more ecological design of the market economy are formulated.

Effects of the New Deal

The questions of what the New Deal actually was and how successful it was are still controversial today. Answering the question about its success also depends on perspective. It has to be clarified whether one measures the success or failure of the New Deal in terms of overcoming the desolate state of the American economy when Roosevelt took office, or in terms of the desire for full employment, full production utilization and high mass purchasing power. The evaluation of social policy under the sign of the New Deal also depends on such considerations. On the one hand, milestones in American social policy can be seen in the laying of the foundation stone of a welfare state and in the fact that the right of every American to a decent livelihood became part of everyday life. On the other hand, it can also be emphasized that social security for all and a “fair” distribution of income and wealth could not be achieved during Roosevelt's tenure.

Beyond the controversies, there are a number of statements on which all interpreters can agree: With the massive intervention policy of the state in almost all areas of society, the New Deal gave new hope to a discouraged, insecure and directionless nation. Unlike in the German Reich and in many other countries, democracy in the United States was preserved through the phase of uncertainty in the wake of the global economic crisis. It is clear that the New Deal alleviated high unemployment and social hardship, but that full employment was only achieved when the USA entered the war.

Result of social policy

With the New Deal, the state took responsibility for securing the subsistence level for the first time. In 1930, the states only spent $ 9 million on welfare, and there was no unemployment benefit. By 1940, welfare payments increased to $ 479 million and unemployment benefits increased to $ 480 million. In view of the population emaciated by the Great Depression, these sums were still very low. The USA entered the 20th century in terms of social policy, but the social policy laws were only modest beginnings.

With the New Deal, the relationship between the federal government and the states also changed. For the first time in the history of the United States, the federal government assumed competences in social policy. This expansion went hand in hand with a reduction in the political importance of the states which, prior to the New Deal, had sole competence in social policy. Citizens began to turn to the federal government with their problems. In addition, joint tasks were created, which expanded the range of tasks of both the federal government and the states, such as B. Public unemployment insurance. At the same time, the joint tasks increased the states' dependence on financial aid from the federal government.

Result of economic policy

Recovery measures

The economic recovery began in 1933 and, with the exception of a sharp slump in 1937, economic growth remained high. The average economic growth between 1933 and 1941 was 7.7% per year. In 1933 deflation also ended . Unemployment fell by 25% by 1940, but was still well above pre-crisis levels. There is agreement that it was only the high government deficits associated with the Second World War that led to full employment. However, since the causes of the Great Depression are controversial among historians and economists, there are also different views on the evaluation of the recovery measures in the course of the New Deal.

Already at the beginning of the Great Depression, Keynesians turned against the "Treasury View" , according to which state deficit spending would have to crowd out private investments ( crowding out ). Rather, state deficit spending would provide a self-reinforcing growth impulse via the multiplier effect. Keynes analyzed the macroeconomic situation as an equilibrium with underemployment , which is why, despite the strong economic recovery, high economic unemployment remained. Roosevelt pursued the goal of low borrowing between 1933 and 1941. The government's fiscal policy therefore spared the national budget, but on the other hand did not contribute much to the recovery. According to Keynesian view, the measures of the New Deal supported the economic recovery, but it was not until the end of 1941, caused by the Second World War, that the expansionary fiscal policy brought about the end of the depression and full employment. In terms of economic policy, Paul Krugman sees the short-term effect of the New Deal as less successful than the long-term effect. An international comparison also shows that countries that had used massive deficit spending, such as Sweden or the German Reich, overcame the depression more quickly.

According to monetarist analysis, a contraction in the money supply was the main cause of the Great Depression. There is broad consensus in the literature today that the change in monetary policy was a factor that contributed significantly to the recovery. The almost unanimous view is that there is a clear temporal and substantive relationship between the move away from the gold standard and the start of the recovery. From 1933 to 1941 the nominal money supply increased by 140%, the real money supply by 100%. Christina Romer comes in her work What ended the Great Depression? (1992) concluded that US production would have been 25% lower in 1937 and 50% lower in 1942 had it not been for the turnaround in monetary policy. There is consensus that the US Federal Reserve contributed nothing to the economic recovery. The stabilization of the banking system and the expansion of the money supply declined solely on the initiative of President Roosevelt's government. According to J. Bradford DeLong , Lawrence Summers and Christina Romer, the economic recovery from the economic crisis was essentially complete before 1942 (that is, before the sharp rise in war spending in the United States). They assume that the New Deal's monetary policy in particular contributed to this. Such historians and economists, who reject the Keynesian declaration, see predominantly cyclical unemployment only for the phase from 1929 to 1935. After that, the problem is more of a structural unemployment. been. In particular, the successes of the unions in implementing high wage increases have led companies to introduce efficiency-oriented recruitment procedures. This ended inefficient employment relationships such as child labor , odd jobs for unskilled workers at starvation wages and sweatshop jobs. In the longer term, this led to high productivity, high wages and a generally high standard of living. But that required well-trained and hard-working workers. It was not until the massive government spending in the wake of the United States' entry into the war brought full employment that the high number of unskilled workers declined; this has eliminated structural unemployment.

Historians and economists who believe that the New Deal successfully fought the Great Depression include: B. Peter Temin , Barry Wigmore, Gauti B. Eggertsson and Christina Romer . They also see a psychological effect of the New Deal as an essential requirement. The policy change away from the dogmas of the gold standard, a balanced budget even in times of crisis and minimal statehood had a positive impact on people's expectations that they would no longer result in a further economic contraction (recession, deflation), but with economic recovery (economic growth, inflation, higher wages) calculated what stimulated investment and demand. According to this analysis, 70 to 80% of the economic recovery can be attributed to the policies of the New Deal. In the event of a (hypothetical) continuation of the inactive economic policy of former President Hoover, according to this view, the American economy would have been in recession beyond 1933, so that gross domestic product would have fallen by a further 30% by 1937.

In contrast, some historians and economists take the view that the New Deal, taken as a whole, tended to prolong the Great Depression. Recognition of the unions has resulted in higher wages and lower company profits, which has led to persistent unemployment. High taxes would have hampered growth, public investments would have crowded out private ones and government intervention would have unsettled entrepreneurs and business people. A prominent proponent of this view is Amity Shlaes. She analyzes and evaluates the New Deal in her book The Forgotten Man: A New History of the Great Depression (2007) from the perspective of an advocate of free (unregulated) markets . The book was enthusiastically received by Conservatives, and Shlaes was named one of the Republican Party's biggest pounds. The book was criticized by liberals, among other things, for the fact that Shlaes presented the subdued development of the Dow Jones index as an indicator of economic development instead of the dynamic development of gross domestic product . Eric Rauchway described this as an attempt to downplay the economic recovery by referring to a less representative indicator. Keynesian JR Vernon also believes that the economic recovery from the economic crisis was less than halfway through by 1941 (measured by the continued trend of pre-crisis growth). He sees expansionary fiscal policy from 1942 onwards as a decisive factor and monetary policy only as a supporting factor in ending the Great Depression. In a 1995 survey, 6% of historians and 27% of economists unreservedly agreed that the New Deal tended to prolong the Great Depression. On the other hand, it was unreservedly rejected by 74% of historians and 51% of economists.

Reform measures

The purpose of economic reforms was to save the market economy by stopping the worst excesses and creating a more stable economic order . Regulation of the banking system and securities trading made the financial markets less crisis-prone. The labor relations between employers and employees and the state as a mediating instance developed with union recognition to a more cooperative relationship.

The new economic order created by the New Deal survived the Second World War and the electoral successes of the Republican Party unscathed, especially because the Republican Party made no more serious attempts to change or reverse essential parts of the New Deal. It can be assumed that the new economic order was a determining factor in the length and extent of the extraordinary post-war boom .

The New Deal banking reform has been eased since the 1980s. The 1999 repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act allowed shadow banking to grow rapidly . Since these were neither regulated by the state nor secured by a financial safety net, the shadow banks were a central reason for the financial crisis from 2007 and the global economic crisis from 2007 .

Impact on minorities

The Indian Reorganization Act brought a modest improvement in the situation of the Indians. However, even through the New Deal, blacks and other minorities did not achieve equality. From Roosevelt's Brain Trust, Eleanor Roosevelt , Harry Hopkins, and Harold Ickes, in particular, campaigned for black rights. Roosevelt was aware, however, that he was politically dependent on the votes of the Democratic MPs from the southern states, who wanted nothing to do with equality for blacks. He therefore made no attempt to enforce equality by law. However, blacks who were affected by unemployment and poverty above average benefited particularly from the non-discriminatory work and social programs of the New Deal. This also had an impact on the elections. Until 1932, blacks had traditionally voted for the party that had forced the abolition of slavery in the American Civil War, that is, the Republicans. Like many whites living in poverty, many blacks began to see Roosevelt as a savior in need. In a poll before the 1936 presidential election, 76% of blacks said they were ready to vote for Roosevelt. The voter migration gradually resulted in an increasing influence of the civil rights movement on the Democratic Party. However, it was not until the 1960s, under Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson, that there was great success on the issue of black equality.

Key debates

Arthur M. Schlesinger and William E. Leuchtenburg see the New Deal as a reaction to the economic crisis, which was mainly characterized by sympathy for the suffering of the population. In his trilogy The Age of Roosevelt (1957, 1958, 1960), the contemporary witness and New Deal supporter, Schlesinger, reminds us that the welfare state reforms that primarily benefited the middle class had to be implemented against the resistance of the upper class . Leuchtenburg's Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal 1932–1940 (1963) is also written out of a fundamental sympathy, but illuminates the New Deal with a somewhat more critical distance. He argues that the New Deal created a fairer society by gaining some recognition from previously excluded groups. B. the unions. On the other hand, he complains that these problems have only been partially resolved; the situation improved little for slum dwellers , tenant farmers and blacks. Increased state intervention was necessary because the previously much-vaunted invisible hand of the unregulated market had failed.

In the 1960s, the New Left generation of historians criticized the New Deal as a wasted opportunity for radical change. Barton J. Bernstein complains that the New Deal did little to help the impoverished and did not bring about any redistribution of income. Paul Conkin complains quite similarly that the goals of social justice and a happier and more fulfilling society have been missed.

In contrast, historians and economists who advocated a free (unregulated) market economy criticized the New Deal in the 1970s for the opposite reasons. The measures went far too far and government spending fueled inflation. The assumption of state responsibility for the subsistence level of the citizens made them dependent on social assistance and stifled entrepreneurial creativity. A prominent representative of this direction is Milton Friedman . Friedman was employed in the Works Progress Administration under the Roosevelt administration , for which he analyzed the incomes of American families to assess the extent of the hardship. Looking back in 1999, he declared that he rejected the reform measures of the New Deal, in particular the work of the National Recovery Administration , the Agricultural Adjustment Act and the introduction of a rudimentary welfare state. In contrast, he considered the relief and recovery measures to be useful. He considered the recovery of the economy and in particular the expansionary monetary policy to be necessary. He also saw the job creation programs and social assistance measures as appropriate to the situation. In his book The Road to Serfdom (1944), which was only widely received in the 1970s , Friedrich August von Hayek wrote that he feared that the expansion of state responsibility through the New Deal could lead to an economy of central administration and political slavery. These authors saw the election of Ronald Reagan as US president as a turning point, they expected that Reagan would reverse the expansion of state responsibility.

Underlying the works of the 1980s was a tendency not to measure the New Deal by what was not achieved, but by what was achieved against the inertia of the United States' political system. The book The Rise and fall of the New Deal order, 1930–1980 (1989) by Steve Fraser and Gary Gerstle deals primarily with the continuity and consequences of the New Deal against the background of the beginning Reagan era. More recent 1980s literature by Robert Eden, The New Deal and its legacy: critique and reappraisal (1989) and Harvard Sitkoff Fifty years later: the New Deal evaluated (1985) confirmed that the New Deal was a major change in politics, Social and economic history was. Anthony Badger's The New Deal (1989) rated the successes in social reforms as modest, but emphasized the tenacity of the resistance to be overcome among conservative Democrats, Republicans and voters. Alan Brinkley came to the conclusion in his book The New Deal and the Idea of the State (1989) that the New Deal was not based on a consistent concept, but on the demand for the most active government possible. A high demand for responsibility and effectiveness of the government is a distinguishing feature between liberal democrats and conservative republicans.

Historian David M. Kennedy sees in his Pulitzer Prize- winning work Freedom From Fear, The American People in Depression and War 1929–1945 (1999), a leitmotif of the New Deal is to take away the citizens' uncertainty. This motive runs through the entire legislation: from the reform of the banking and stock exchange system, which gave investors more security, to the work of the National Recovery Administration, which should give companies more planning security, to the establishment of the welfare state and support farmers in distress. There are some things that the New Deal did not achieve or, in some cases, did not aim at, such as B. the redistribution of income or the abolition of the market economy. Nevertheless, much had been achieved, in particular the economic reforms had ensured that the profits achieved in the market economy system could be distributed more evenly ( Great Compression ). He cites the recognition of the trade unions, the regulation of banks and stock exchanges, with which further market failure has been prevented, and the introduction of social insurance, which has given citizens greater financial security, as essential for this.

From a system-theoretical point of view, the decision in favor of the “New Deal” is a decision against totalitarianism of socialist and fascist stamps. “Constitutionalizations” had made the economy subject to national limitations without sacrificing its basic autonomy.

Overview of New Deal measures

Open-ended measures

- Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC): Established by the Hoover Administration in 1932 and expanded under the Roosevelt Administration under the leadership of Jesse Holman Jones , providing credit to banks and businesses. It was dissolved in 1954.

- Abolition of the gold standard in 1933. (until today).

- Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA): a company founded in 1933 that supplied the underdeveloped Tennessee Valley with electricity. (Still exists today).

- Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA): a law passed in 1933 and amended in 1935 that provided financial aid to stabilize the prices of agricultural products. (Still exists today).

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC): insures private bank deposits and financial supervision of banks. (Still exists today).

- Glass-Steagall Act : passed 1933. Regulated the financial system, in particular through the introduction of the separate banking system. Abolished in 1999, reintroduction has been discussed since the financial crisis in 2007 .

- Securities Act of 1933 : Act of 1933 that created the United States Securities and Exchange Commission to oversee securities transactions. (Still exists today).

- Indian Reorganization Act : Act passed in 1934, which should allow the Indians more independence. (Still exists today).

- Social Security Act : Act passed in 1935 that established a welfare state in the United States. (Still exists today).

- Wagner Act : Law passed in 1935 recognizing unions as a bargaining party and establishing the National Labor Relations Board , which is still in existence today . The law was slightly modified in 1947 by the Taft-Hartley Act . (Still exists today.)

- Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC): A program for unlimited support especially for single parents with children. (Was replaced under protests in 1996 by the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families , which is limited in time)

- Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937 : a 1937 judicial reform initiative that failed but contributed to the 1937 constitutional change.

- Federal Crop Insurance Corporation (FCIC): Established in 1938 to insure farmers against crop failure, it was reorganized in 1996. (Still exists today).

- Surplus Commodities Program : program introduced in 1936 to distribute food to the poor. (Still exists today as a Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program ).

- Fair Labor Standards Act : Act passed in 1938 that limited the working week to a maximum of 44 hours. In addition, a minimum wage was introduced and child labor was banned. The weekly working time was later reduced to 40 hours and the minimum wage increased on various occasions. (Still exists today).

- Rural Electrification Administration , (REA): an authority that organizes power supply in remote areas. (Still exists today as a Rural Utilities Service ).

- Resettlement Administration (RA): an agency that organized the resettlement of impoverished farmers (especially from dust bowl regions). Was replaced by the Farm Security Administration in 1935.

- Farm Security Administration (FSA): an agency that organized aid for very impoverished farmers. (Exists today as Farmers Home Administration ).

Temporary measures

- United States bank holiday : in 1933 all banks were closed for a few days. During this time it was evaluated which banks could be rescued with state aid and which had to remain closed forever.

- Homeowners Loan Corporation (HOLC): Helped over-indebted homeowners avoid foreclosure and banks avoid loan defaults. The measure expired in 1951.

- National Recovery Administration (NRA): Established in 1933 to fight deflation . She tried to persuade as many companies as possible to voluntarily renounce unfair (price) competition, minimum prices, minimum wages, recognition of trade unions, etc. It was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1935.

- Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA): Successor to the Emergency Relief Administration founded in 1932 under the Hoover Administration. She initiated minor job creation measures and was replaced in 1935 by the Works Progress Administration .

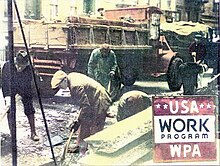

- Works Progress Administration (WPA): An agency founded in 1935 that created job creation schemes for more than 2 million unemployed people. The program expired in 1942.

- Public Works Administration (PWA): was founded in 1933 for the planning and implementation of large projects as job creation measures. The program ended in 1938.

- Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC): existed from 1933 to 1942 as a job creation program for young men. The CCC was used for afforestation, fighting forest fires, building roads and fighting soil erosion.

- Civil Works Administration (CWA): initiated some job creation efforts between 1933 and 1934.

literature

- English

- John Braeman, Robert H. Bremner, David Brody (Eds.): The New Deal . 2 volumes. Ohio State University Press, Columbus OH 1975. (Full access to the pages of the publisher: Volume 1 , Volume 2 )

- Robert Eden: The New Deal and its legacy: critique and reappraisal. Greenwood Press, 1989, ISBN 0-313-26181-4 .

- Ronald Edsforth: The New Deal: America's Response to the Great Depression (Problems in American History) . Blackwell, Malden 2000, ISBN 1-57718-143-3 .

- Fiona Venn: The New Deal. Routledge, 2013, ISBN 978-1-135-94290-8 .