Post-war boom

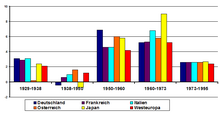

The post-war boom (also known as the Golden Age of Capitalism in English-language literature ) was a period of unusually strong economic growth and high income increases from the end of World War II to the first oil crisis in 1973. Income levels in Western European countries matched that of the USA . The post-war boom was seen in West Germany and Austria as an economic miracle , in France as Trente Glorieuses (“thirty glorious years”), in Spain as Milagro español (“Spanish miracle”), in Italy as Miracolo economico italiano (“Italian economic miracle”). Japan also experienced exceptionally strong economic growth and became the second strongest economy in the world. The causes of the Golden Age are the subject of an ongoing scientific debate.

Global post-war boom

Economists like Paul A. Samuelson had warned of a return of the depressive tendencies in the post-war period. The politicians, too, had fond memories of the time between the world wars and were determined to prevent history from repeating itself. In sharp contrast to the time after the First World War, the time after the Second World War was characterized by a long-lasting boom with rapid economic growth.

|

Aftermath of World War II

United States

Usually, the end of the war is accompanied by a severe economic crisis. This was not the case, at least in the USA. The end of the war in 1945 brought a drastic reduction in armaments spending, but this gap in demand was compensated for by the high demand for consumer goods. American (and European) industry had expanded and modernized during World War II. The highly efficient war industry was partially converted to the production of consumer goods, so that increasingly cheaper, yet high-quality consumer goods came onto the market.

Continental Europe

Some countries were badly damaged due to war damage and / or occupation. There was a particularly strong catch-up effect here in the early days of the post-war boom.

|

For the first phase of the upswing it was decisive that, despite the consequences of the war, there was still a sufficient supply of industrial assets and qualified workers. Immediately after the war, industrial production in France, Belgium and the Netherlands fell to 30–40% of pre-war levels, and in Germany and Italy to 20%. Only a small part of this low industrial production was due to the destruction of industrial plants during the war, and to a much larger extent to the lack of raw materials, the extensive destruction of the transport infrastructure and the destruction of means of transport. The industrial substance of Germany was not so badly damaged by the Second World War and the reparations. According to research by Werner Abelshauser , the gross fixed assets had fallen to the level of 1936 by 1948, although the majority of these were relatively new, less than 10 years old systems. In contrast, industrial production in 1948 was less than half of its 1936 level. In 1947, measures were taken in the American and British occupation zones to restore the transport infrastructure that had been destroyed by the war, and the dynamic economic upswing began. From January 1947 to July 1948 industrial production rose from 34% to 57%, measured against the level of 1936; from the currency reform to the establishment of the Federal Republic, industrial production rose to 86%.

Contributed to the European upturn also has Marshall Plan , the US President Harry S. Truman and Secretary of State George C. Marshall initiated. From 1948 to 1951 many Western European countries received a total of $ 13 billion in economic aid. This aid corresponded to only 2.5% of the national income of the recipient countries, so the capital injection itself could only have been the cause of a small fraction of the rapid economic growth in Western Europe. A much more important meaning of the Marshall Plan was psychological in nature. As a visible sign of American-Western European cooperation, it helped to overcome the fear of political and financial instability and thus created a positive investment climate.

Production modernization

During the Second World War, the German and Japanese war economies were unable to cope with standardized mass production in the American style (see also War Economics in World War II ). The attempt to achieve American production efficiency without completely giving up the flexibility of production traditionally regarded as important in Germany and Japan, but gradually led to the development of flexible mass production . This brought the German and Japanese economies a production-technological leadership in the post-war period, as it was possible to respond more flexibly to the wishes of consumers than with the more cumbersome, highly standardized mass production, to which the USA, Great Britain and the Soviet Union held on for a long time after the war. In a way, that was how the losers of the war had "won" the peace.

Global economic order

Free trade

During the global economic crisis from 1929 onwards, most states had adopted a pronounced protective tariff policy. An example of this is the American Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930. In the USA, the Reciprocal Trade Agreement Act was passed in 1934 , which laid the foundations for a customs policy based on the principle of most-favored-nation treatment . American foreign trade was gradually liberalized again through the conclusion of bilateral trade agreements. The other large industrialized nations also decided to return to free trade. In 1947 the international general agreement on tariffs and trade (GATT) was concluded, with which the participating nations agreed to gradually reduce tariffs and other trade barriers .

Bretton Woods system

With the Bretton Woods system , an international currency order was created in 1944, in which the exchange rates of the currencies were linked to the value of the US dollar. This freed world trade from exchange rate risks. The Bretton Woods system explicitly allowed the participating states to regulate capital imports and capital exports through capital controls.

The Bretton Woods system was abandoned in the early 1970s. It failed because of the Triffin dilemma and the increasing unwillingness of some participating states to adjust their national monetary policy to the fixed exchange rate. Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff come to the conclusion that it was primarily the capital controls that ensured that there were few banking crises in the 1950s and 1960s.

Relative low interest rate policy

A Golden Age Keynesianism was pursued in interest rate policy; H. attempts were made to stimulate economic growth through low interest rates, so that both wages and corporate profits rose.

The government debt had risen sharply as a result of the war spending in World War II. The financial repression observed between 1945 and 1980 , the high economic growth and the relatively low average budget deficits led to a rapid reduction in the debt ratio (national debt in relation to nominal gross domestic product).

General consensus on social and economic policy

In response to the global economic crisis from 1929 onwards, the following adjustments were observed worldwide:

- Unions became more influential. Union membership doubled in the United States.

- In the United States, the New Deal established a welfare state . A welfare state already existed in most European countries, and this was expanded in response to the crisis.

- In most states, regulation of the economy has been strengthened, in particular through the creation of a financial market regulator and banking regulation .

These developments also remained decisive in the post-war boom.

After the global economic crisis, strong trade unions and, at the latest since the Second World War, also high progressive taxes ensured a reduction in income inequality ( Great Compression ). This development also continued during the post-war boom.

Advances in technology and production

During the post-war boom, there was an explosion of theoretical and practical knowledge. For example, the first digital computer was installed in 1946, a technology that has continued to improve since then. With medical advances in the 1950s, surgeries became less risky than before and were more likely to bring about a cure. As a result, the demand for hospital services increased dramatically.

The labor productivity increased in industrial production mainly through automation sharply.

Individual countries

The following table shows the European countries that showed the highest economic growth from 1950 to 1973 ( gross domestic product per capita, adjusted for purchasing power in international dollars from 1990).

| country | Average annual economic growth 1950–1973 |

|---|---|

|

|

6.2% |

|

|

5.8% |

|

|

5.6% |

|

|

5.0% |

|

|

4.9% |

|

|

4.9% |

|

|

4.2% |

|

|

4.0% |

|

|

3.5% |

|

|

3.4% |

German economic miracle

In the Federal Republic of Germany, an economic system known as the social market economy was implemented primarily by Ludwig Erhard and Alfred Müller-Armack . The concept was based on ideas that were developed by ordoliberals in the 1930s and 1940s, with different emphasis . The conception of the social market economy was based on ordoliberal ideas, but is characterized by greater pragmatism, for example in economic and social policy .

According to the United States Strategic Bombing Survey , German economic production had hardly been affected by the air raids until the end of 1944. Somewhat stronger in 1945, but less because of critical damage to production facilities and more because of damage to the transport infrastructure and power lines. After the war-torn transport infrastructure began to be restored in the American and British occupation zones in 1947, production rose sharply from autumn 1947, but the supply situation for the population did not improve yet, as large quantities of stock were produced in anticipation of a currency reform. After the currency reform of 1948 , the shops were full. In the following period came the so-called breakthrough crisis, the cost of living rose faster than hourly wages and unemployment rose from 3.2% in early 1950 to 12.2%. The situation on the labor market relaxed quickly in the wake of the global economic boom as a result of the Korean War , and full employment was even achieved in 1962 . The 1950s and 1960s were characterized by high economic growth rates and high income increases. The export boom was also connected with the undervaluation of the DM within the framework of the Bretton Woods system. Due to the undervaluation, imports were relatively more expensive and exports relatively cheaper, which boosted the German export economy. Before the economic miracle, Germany was characterized by, compared to the USA, relatively low productivity, long working hours and incomes, which for the majority of people only had a simple life, e.g. Partly allowed in existential poverty. As a result of the economic miracle, Germany achieved high productivity by international standards, on average relatively high incomes and relatively short working hours.

In the 1970s, growth rates fell in Germany, as in other European countries. With the end of the Bretton Woods system in the early 1970s, the DM appreciated sharply, which led to imports becoming cheaper. Some industries lost their international competitiveness , which accelerated structural change .

Austrian economic miracle

In 1945 the Austrian Schilling was reintroduced. From 1947 Austria received Marshall Plan aid. Finance Minister Reinhard Kamitz and Federal Chancellor Julius Raab pursued a policy of social market economy (“Raab-Kamitz course”), similar to that in Germany.

Trente Glorieuses in France

Between 1945 and 1973, France experienced exceptionally strong economic growth. Going back to Jean Fourastié , this period is known as Trente Glorieuses (“thirty glorious years)”. In France, a controlled market economy was operated under the name dirigisme or planification . Charles de Gaulle created a planning commission in which business leaders and civil servants planned the rebuilding of key industries. De Gaulle also encouraged companies to merge into larger units so that companies were created that were large enough to gain market share in international competition. Politics had an impact, "National Champions" such as Renault and PSA Peugeot Citroën emerged . While none of the 100 most profitable companies worldwide were French in 1950, there were already 16 in 1973 (for comparison: Germany then had 5 of the 100 most profitable companies worldwide). The master plan for the reconstruction of France stipulated that six key sectors were given preferential treatment with loans, foreign exchange and raw materials. The economic coordination was similar to the administrative guidelines of Japanese economic policy. It was not until 1958, after a sharp devaluation of the franc and the introduction of wage controls, that France began to focus more strongly on free trade.

Milagro español

Spain had a policy of import-substituting industrialization in the 1940s and 1950s . By 1959, 90% of imports were subject to quantitative restrictions. After 1959, Spanish foreign trade was liberalized. By 1966, only 30% of imports were subject to quantitative restrictions. The index of industrial production rose from 100 in 1929 to 133 in 1949, 320 in 1959 and 988 in 1970.

Miracolo economico italiano

During the golden age between 1950 and 1973, the Italian gross national product grew almost as fast as that of West Germany. The Italian Constitution of 1947 provided for a free market economy, which provided for state interventionism, particularly for the welfare state and social justice. By participating in the Marshall Plan, Italy had committed to gradually liberalizing foreign trade. With the establishment of the European Economic Community , Italy committed itself to the complete liberalization of foreign trade, which was completed by 1968. The economic policy of Italy was influenced for almost the entire Golden Age by the director of the Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale Pasquale Saraceno , who planned and coordinated the economic recovery and the use of the Marshall Plan aid. In addition, an institute was founded to plan the industrialization of structurally weak southern Italy. Economic policy consisted primarily of promoting key industries, establishing state-owned companies and state banks, and subsidizing exports. The Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale alone and the then state-owned Eni SpA contributed 16% of all industrial investments in 1951, and by 1962 the share of industrial investments rose to 27%.

From 1963 economic growth began to slow down across Western Europe. The Italian government tried in vain to counteract this by intensifying economic planning. It should be noted critically that especially in the 1960s, in a number of cases, the rescue of the state of companies did not follow any economic-political logic, but a purely political logic and thus represented predictable bad investments.

Economic interpretations

In Germany, the post-war boom was for a long time viewed as a specifically German development and the reasons for the boom were therefore only sought in German economic policy. In the 1970s, a connection to the war damage was established (reconstruction thesis). In the late 1970s, economic historians discovered that an outstanding post-war boom had occurred across Western Europe and Japan. The thesis was put forward that the economies that had the relatively lowest productivity after 1945 produced the highest productivity gains and the highest economic growth until the 1970s (catch-up thesis). The interpretation of the post-war boom is still not entirely uniform among economic historians and economists. However, the view has largely gained acceptance that the reconstruction effect played a major role until the end of the 1950s and the catch-up effect until the beginning of the 1970s.

The end of the post-war boom is explained on the basis of the reconstruction thesis and the catch-up thesis that both the war-related reconstruction process and the catch-up process vis-à-vis the USA represented a special development that had to be exhausted once the goal was achieved. This view has largely prevailed today. Theses that go beyond this are usually presented as a supplement. From a supply theory perspective, reference is made to the deterioration in the return on investment since the late 1960s. A supply policy was recommended as a recipe against the slowdown in growth . From a Keynesian point of view, reference is primarily made to the consolidation of inflation expectations, which was caused by a restrictive monetary policy with a correspondingly dampening effect on the economy. The monetarist monetary policy practiced since the 1980s is seen as tending to be too restrictive in the sense of being detrimental to growth.

Keynesian explanation

According to Keynesian analysis, the problems of the interwar period hindered economic growth in Western Europe even more than did the US. In contrast to the USA, a restrictive monetary policy was predominantly pursued in Europe , which had very negative effects in the post-war recession 1920–1921, the stabilization crises after the war-related hyperinflation and the deflationary policy of Great Britain with a return to the gold standard and the German Reich in 1932. Together with the collapse of the international financial system, this is also blamed for the global economic crisis .

In contrast, the “Keynesian era” of the post-war boom was characterized by an expansive economic policy to control the business cycle, to avoid mass unemployment and to achieve maximum capacity utilization. The Bretton Woods system had contributed to the liberalization of foreign trade and the stabilization of the international financial system.

According to this view, the fact that Germany already experienced strong economic growth in the 1950s, although it only switched to a Keynesian economic policy in the 1960s, does not speak against the thesis that German growth in the 1950s was not solely determined by the supply side. On the one hand, the export-driven growth strategy of the 1950s was dependent on free trade policy and the general Western European post-war boom. On the other hand, the Deutsche Bundesbank was forced to adopt an expansive monetary policy because of the Bretton Woods system. According to Ludger Lindlar, the Keynesian explanation is coherent in the long run, but in its pure form, i.e. when the reconstruction and catch-up effect is denied, the quite different growth rates z. B. between the USA and Great Britain on the one hand and Germany or France on the other.

Offer theory approach

The supply theory perspective was developed as an alternative explanation to the Keynesian perspective. According to Charles P. Kindleberger and others, it was not decisive whether supply or demand forces had triggered growth, but only that the supply side did not limit growth. Above all, the "flexible labor supply" was decisive due to the shrinking number of jobs in the agricultural sector, high immigration rates and high population growth. This has kept wages low and thus enabled an investment boom driven by high profits. Barry Eichengreen focuses more on institutional wage restraint through social alliances of employers and trade unions or state wage and price controls.

According to Ludger Lindlar, the supply theory approach is coherent in itself, but cannot explain the extraordinarily strong productivity growth. Nevertheless, the supply theory approach is criticized by some economists. If wages that were too high were the reason for the end of the post-war boom, falling wages should have caused the boom to return. Indeed, since 1982 real wage increases in most Western European countries have lagged well behind productivity growth, so that in many countries the wage share has fallen back to or below the 1970 level. Some economists conclude from this that the existing mass unemployment can no longer be attributed to excessively high wages.

Demand-theoretical approach

In rejection of the supply theory approach, the demand theory approach arose. Following Say's theorem , supply theorists assume that the companies that are inferior to the competition look for and find other profitable investment opportunities. Demand theorists assume that this is not always the case. If the losing companies do not give up the market, they will also accept a falling profit rate in the price competition. This in turn leads to falling investment, falling demand and falling employment across the industry. Accordingly, the catching up economies, especially Germany and Japan, had realized larger export surpluses at the expense of the advanced economies of the USA and Great Britain in the 1950s and 60s. This was tolerated as long as the advantages of growing foreign trade outweighed the disadvantages in the USA and Great Britain as well. In the 1960s, world trade increased so rapidly that the foreign trade deficits or surpluses brought about the end of the Bretton Woods system. As a result, the dollar depreciated sharply against other currencies; this increased the international competitiveness of the USA to the detriment of other countries, especially Germany and Japan. In addition, the US economy took measures to reduce costs. For their part, the Japanese and German economies reacted with cost reductions and wage restraint. The situation was exacerbated by the rise of East Asian economies, which in turn expanded world market shares. According to this approach, there is an increasing overproduction crisis or secular stagnation , which led to a long downturn after the post-war boom.

Specifically German development

Herbert Giersch , Karl-Heinz Paqué and Holger Schmieding explain the German post-war boom with the ordoliberal regulatory policy. The upswing was initiated by a market economy shock therapy as part of the currency reform. A cautious monetary and fiscal policy led to persistent current account surpluses. The growth of the 1950s was driven by the spontaneous market forces of a deregulated economy and ample corporate profits. Increasing regulation, higher taxes and rising costs would then have slowed growth from the 1960s onwards.

Werner Abelshauser or Mark Spoerer , for example, object to this point of view, claiming that a West German special development is postulated, which does not, however, correspond to the facts. There was not only a German economic miracle, but also z. B. a French. French economic growth in the 1950s to 1970s was almost parallel to that in Germany, although the social market economy in Germany and the more interventionist planification in France represented the strongest economic and political contradictions in Western Europe. This suggests that the various economic policy concepts are of little practical importance as long as property rights and a minimum level of competition are guaranteed.

Reconstruction thesis

The reconstruction thesis was developed in rejection of a specifically German interpretation. According to the explanatory approach worked out in the 1970s by Franz Jánossy , Werner Abelshauser and Knut Borchardt in particular , productivity growth remained far below the potential of the German and European economies due to the effects of the First and Second World Wars and the intervening global economic crisis. Abelshauser was able to show, following contemporary work, that the extent to which German industry was destroyed in the war had been greatly overestimated in literature. While the Allies had succeeded in destroying entire cities, the targeted shutdown of industrial plants had hardly succeeded. In spite of all the destruction, therefore, there remained a significant amount of intact capital stock, highly qualified human capital, and tried and tested methods of corporate organization. Therefore, after the end of the war, there was particularly high potential for growth. Due to the falling marginal return on capital, the growth effect of investments was particularly high at the beginning of the reconstruction and then fell as the economy approached the long-term growth trend. The Marshall Plan is not considered to be of great importance for the West German reconstruction, since the aid started very late and had only a small volume compared to the total investment. A “mythical exaggeration” of the currency reform is also rejected. The reconstruction process started a year before the currency reform with a strong expansion of production; this was the decisive prerequisite for the success of the currency reform.

Abelshauser sees the reconstruction thesis confirmed by the economic failure of the monetary, economic and social union . On the basis of the specifically German interpretation of the post-war boom, Federal Chancellor Helmut Kohl, as well as most German politicians and most West German economists, believed that a second economic miracle in the five new federal states could be sparked by a regulatory-induced unleashing of market forces. The government essentially followed a bulletin by Ludwig Erhard in 1953, in which he had planned the economic completion of reunification. The introduction of the DM at an excessive exchange rate only led to the elimination of the international competitiveness of East Germany; With the expiry of the transfer ruble offsetting on December 31, 1990, East German exports collapsed suddenly. In the end, the economic miracle turned out to be unrepeatable.

A comparison of economic growth rates reveals that countries that had suffered considerable war damage and a tough occupation regime recorded particularly high growth rates after the Second World War. In addition to Germany, Austria, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands and France experienced rapid catch-up growth of (on average) 7–9% annually between 1945 and 1960. Countries less severely affected by the war or neutral countries experienced economic growth of “only” 3–4%. According to Ludger Lindlar, the reconstruction thesis therefore offers an explanation for the above-average growth rates of the 1950s. But only the catch-up thesis can explain the high growth in the 1960s.

Catch-up thesis

The catch- up thesis put forward in 1979 by economic historians Angus Maddison and Moses Abramovitz is now represented by numerous economists (including William J. Baumol , Alexander Gerschenkron , Robert J. Barro , Gottfried Bombach and Thomas Piketty ). The catch-up thesis indicates that by 1950 the USA had achieved a clear productivity lead over the European economies. After the war, the European economy started a catch- up process and benefited from the catch-up effect . European companies were able to follow the example of American companies. Figuratively speaking, the catching-up process took place in the slipstream of the leading USA and thus allowed a higher pace. After the productivity level of the American economy had been reached and the catching-up process had come to an end, the Western European economy stepped out of the slipstream at the beginning of the 1970s, so that the high growth rates as in the 1950s and 60s were no longer possible.

The catch-up thesis can be the different high growth rates z. B. between the USA and Great Britain on the one hand and Germany or France on the other. According to an analysis by Steven Broadberry , z. For example, Germany has a strong productivity growth potential by reducing low-productive sectors such as agriculture in favor of high-productivity sectors such as industrial production. There was no such potential for the more industrialized Great Britain. While only 5% of the working population in Great Britain worked in the agricultural sector in 1950, it was 24% in Germany. According to an econometric analysis by Ludger Lindlar, the catch-up thesis for the period from 1950 to 1973 offers a conclusive and empirically well-supported explanation for the rapid productivity growth in Western Europe and Japan.

Individual evidence

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society. Complete works: German history of society 1949–1990. Volume 5, CH Beck, ISBN 978-3-406-52171-3 , p. 48.

- ↑ Thomas Bittner, Western European economic growth after the Second World War , Lit-Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-8258-5272-5 , p. 7.

- ^ Peter Temin: The Golden Age of European growth reconsidered . In: European Review of Economic History . 6, No. 1, April 2002, pp. 3-22. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ^ Randall Bennett Woods : Quest for Identity: America since 1945. Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 1-139-44426-3 , p. 121.

- ^ Nicholas Crafts, Gianni Toniolo, Economic Growth in Europe Since 1945 , Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0-521-49964-4 , p. 4.

- ^ Barry Eichengreen: The Marshall Plan: Economic Effects and Implications for Eastern Europe and the Former USSR . In: Economic Policy . 7, No. 14, April 1992, pp. 13-75. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ↑ Werner Abelshauser, German Economic History. From 1945 to the present. Munich 2011, p. 70 f.

- ↑ Werner Abelshauser, German Economic History. From 1945 to the present. Munich 2011, p. 107.

- ↑ Werner Abelshauser, German Economic History. From 1945 to the present. Munich 2011, p. 115 ff.

- ↑ Werner Abelshauser, German Economic History. From 1945 to the present. Munich 2011, p. 126.

- ↑ Werner Abelshauser, German Economic History. From 1945 to the present. Munich 2011, p. 107.

- ^ Barry Eichengreen: The Marshall Plan: Economic Effects and Implications for Eastern Europe and the Former USSR . In: Economic Policy . 7, No. 14, April 1992, pp. 13-75. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ^ Mark Harrison, The Economics of World War II: Six Great Powers in International Comparison , Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0-521-78503-7 , p. 40

- ^ David M. Kennedy: Freedom From Fear, The American People in Depression and War 1929–1945. Oxford University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-19-503834-7 , p. 142.

- ^ Manfred B. Steger: Globalization. Sterling Publishing Company, 2010, ISBN 978-1-4027-6878-1 , p. 50.

- ^ Manfred B. Steger: Globalization. Sterling Publishing Company, 2010, ISBN 978-1-4027-6878-1 , p. 51.

- ^ Manfred B. Steger: Globalization. Sterling Publishing Company, 2010, ISBN 978-1-4027-6878-1 , pp. 51-52.

- ↑ Carmen Reinhart, Kenneth Rogoff: This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. Princeton University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-926584-8 , pp. 66, 92-94, 205, 403.

- ↑ John N. Smithin, Controversies in Monetary Economics , Edward Elgar Publishing, 2003, ISBN 978-1-78195-799-8 , S. 142nd

- ↑ Reinhart, Carmen M. & Sbrancia, M. Belen, The Liquidation of Government Debt , National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 16893

- ^ E. Saez, T. Piketty: Income inequality in the United States: 1913-1998. In: Quarterly Journal of Economics. 118 (1), 2003, pp. 1-39.

- ^ E. Saez: Table A1: Top fractiles income shares (excluding capital gains) in the US, 1913–2005. October 2007, accessed January 17, 2008 .

- ↑ Christina Romer : Great Depression . ( Memento of the original from December 14, 2011 on WebCite ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 164 kB) December 20, 2003.

- ^ Manfred B. Steger: Globalization. Sterling Publishing Company, 2010, ISBN 978-1-4027-6878-1 , p. 52.

- ^ Peter A. Hall, Michèle Lamont: Social Resilience in the Neoliberal Era. Cambridge University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-1-107-03497-6 , p. 50.

- ^ Randall Bennett Woods: Quest for Identity: America since 1945. Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 1-139-44426-3 , p. 124.

- ↑ David Dranove: The Economic Evolution of American Health Care. From Marcus Welby to Managed Care Princeton University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-691-10253-8 , p.48.

- ^ Randall Bennett Woods: Quest for Identity: America since 1945. Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 1-139-44426-3 , p. 124.

- ^ Nicholas Crafts, Gianni Toniolo, Economic Growth in Europe Since 1945 , Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0-521-49964-4 , p. 6.

- ↑ a b Uwe Andersen, Wichard Woyke (ed.): Concise dictionary of the political system of the Federal Republic of Germany - foundations, conception and implementation of the social market economy . 5th edition. Leske + Budrich, Opladen 2003 ( online licensed edition Bonn: Federal Agency for Civic Education 2003).

- ^ Otto Schlecht: Basics and perspectives of the social market economy. Mohr Siebeck, 1990, ISBN 3-16-145684-X , pp. 9, 12.

- ↑ It was never a "drawing board construction of resourceful economists", but was based on real economic conditions from the start. (Bernhard Löffler: Social market economy and administrative practice. Steiner, Wiesbaden 2002, p. 85).

- ^ Raymond G. Stokes: Technology and the West German Wirtschaftswunder . In: Technology and Culture . 32, No. 1, January 1991, pp. 1-22. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- ↑ Werner Abelshauser, German Economic History. From 1945 to the present. Munich 2011, p. 115 ff.

- ↑ Werner Abelshauser, German Economic History. From 1945 to the present. Munich 2011, p. 119.

- ↑ Werner Abelshauser, German Economic History. From 1945 to the present. Munich 2011, p. 153.

- ↑ Thomas Bittner, Western European economic growth after the Second World War , Lit-Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-8258-5272-5 , p. 7.

- ↑ Hans-Peter Schwarz, The Federal Republic of Germany: a balance sheet after 60 years , Böhlau Verlag Köln Weimar, 2008, ISBN 978-3-412-20237-8 , p. 384

- ↑ Hans-Peter Schwarz, The Federal Republic of Germany: a balance sheet after 60 years , Böhlau Verlag Köln Weimar, 2008, ISBN 978-3-412-20237-8 , pp. 388, 389

- ↑ Hans-Peter Schwarz, The Federal Republic of Germany: a balance sheet after 60 years , Böhlau Verlag Köln Weimar, 2008, ISBN 978-3-412-20237-8 , p. 384

- ↑ Charles Hauss, Comparative Politics: Domestic Responses to Global Challenges , Cengage Learning, 2014, ISBN 978-1-305-16175-7 , pp. 129-130

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition, Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , p. 35.

- ^ Nicholas Crafts, Gianni Toniolo, Economic Growth in Europe Since 1945 , Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0-521-49964-4 , p. 123

- ↑ Walther L. Bernecker, Geschichte Spaniens im 20. Jahrhundert , CH Beck, 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60159-0 , p. 237

- ↑ Christian Grabas, Alexander Nützenadel , Industrial Policy in Europe After 1945: Wealth, Power and Economic Development in the Cold War , Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, ISBN 978-1-137-32990-5 , pp. 139-149

- ↑ Christian Grabas, Alexander Nützenadel, Industrial Policy in Europe After 1945: Wealth, Power and Economic Development in the Cold War , Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, ISBN 978-1-137-32990-5 , pp. 149–156

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition. Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , p. 1

- ^ Peter Temin: The Golden Age of European growth: A review essay . In: European Review of Economic History . 1, No. 1, April 1997, pp. 127-149. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition. Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , p. 11

- ^ Philip Arestis , Malcolm C. Sawyer (eds.): Money, Finance and Capitalist Development. Elgar, Cheltenham 2001, ISBN 1-84064-598-9 , p. 42 ff.

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition, Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , pp. 70-77.

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition, Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , pp. 70-77.

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition, Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , pp. 70-77.

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition, Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , pp. 70-77.

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition, Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , p. 54.

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition, Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , p. 60.

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition, Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , pp. 22-23.

- ↑ Robert Paul Brenner , The Economics of Global Turbulence: The Advanced Capitalist Economies from Long Boom to Long Downturn, 1945-2005 , Verso, 2006, ISBN 978-1-85984-730-5 , pp. 27-40

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition, Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , p. 55.

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition. Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , p. 32

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition. Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , pp. 32-33

- ↑ Mark Spoerer: Prosperity for Everyone? Social market economy. In: Thomas Hertfelder, Andreas Rödder: Model Germany. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-36023-1 , p. 35.

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition, Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , p. 36.

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition. Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , p. 63

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler, German history of society. Complete works: German history of society 1949–1990 , Volume 5, CH Beck, ISBN 978-3-406-52171-3 , page 51

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition. Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , p. 62

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition. Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , p. 63

- ↑ Werner Abelshauser, German Economic History. From 1945 to the present , 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-51094-6 , pages 445-449

- ↑ Mark Spoerer: Prosperity for Everyone? Social market economy. In: Thomas Hertfelder, Andreas Rödder: Model Germany. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-36023-1 , pp. 34-35.

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition. Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , p. 69

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition. Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , p. 85.

- ^ Karl Gunnar Persson, An Economic History of Europe , Cambridge University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-521-54940-0 , pp. 110 ff.

- ↑ Thomas Piketty, Das Kapital im 21. Jahrhundert , Verlag CH Beck, 2015, ISBN 978-3-406-67131-9 , pp. 135-136

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Wagener : The 101 most important questions - business cycle and economic growth. CH Beck, 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-59987-3 , p. 33.

- ^ Peter Temin: The Golden Age of European growth reconsidered . In: European Review of Economic History . 6, No. 1, April 2002, pp. 3-22. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition. Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , p. 95