Ludwig Erhard

Ludwig Wilhelm Erhard ( February 4, 1897 in Fürth – May 5, 1977 in Bonn ) was a German politician ( CDU ) and economist . He was Minister of Economics in Bavaria from 1945 to 1946, Director for Economics of the United Economic Area from 1948 to 1949 and Federal Minister of Economics from 1949 to 1963 . He is often regarded as the father of the "German economic miracle "; its actual share in the economic upswing is disputed, however. He is also often referred to as the father of asreferred to as the social market economy of the Federal Republic of Germany, which he introduced as Economics Minister. However, his part in the development of this concept is also disputed. He was Vice Chancellor from 1957 to 1963 and Second Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany from 1963 to 1966 . From 1966 to 1967 he was Adenauer 's successor as CDU federal chairman.

Life and career until 1945

youth, education and military service

Ludwig Erhard was born on February 4, 1897 in his parents' residential and commercial building at Sternstraße 5 in Fürth. His father was Wilhelm Philipp Erhard, a Catholic textiles merchant and white goods store owner from Rannungen , and his mother Augusta (nee Hassold) was a Protestant. Ludwig was the second of four children, all of whom were baptized as Protestants. At the age of two he contracted spinal polio ; from this time he retained a deformed foot. Erhard attended primary and secondary school in Fürth; after that he began an apprenticeship as a linen merchant . In the spring of 1916 he graduated as a retail salesman.

Erhard then took part in World War I as a soldier in the Bavarian Army . In 1916/17 he was deployed with the 22nd Field Artillery Regiment in Romania and in 1918 on the western front , where he was badly wounded by a hand grenade near Ypres at the end of September 1918 and was only able to recover after seven operations. He dealt with it physically, but not mentally. Standing behind the counter in his father's shop for long periods of time was no longer possible, so Erhard went into science.

In 1919 he retired from the army as a non- commissioned officer (sergeant) and officer aspirant.

scientific career

From 1919 to 1922, Erhard studied at the Nuremberg Commercial College , which was then newly founded, and earned a degree in business administration . He then completed a degree in business administration and sociology at the University of Frankfurt . In December 1925, he received his Dr. re. pole. under Franz Oppenheimer , whom he particularly valued as an academic teacher alongside Wilhelm Rieger . The dissertation was a critical reflection on the work value theory of the supervisor, the grade was "good".

From 1925 to 1928 Erhard worked as managing director in his parents' business, which, however, went bankrupt. Erhard then became an assistant at the Institute for Economic Monitoring of German Finished Goods at the Commercial College in Nuremberg, which had been founded three years earlier by the economist Wilhelm Vershofen . The model was the American National Bureau of Economic Research , but the Berlin Institute for Economic Research soon developed into its German counterpart .

Erhard worked before 1933 as an economic and political publicist. He occasionally wrote in the left-liberal weekly Das Tage-Buch against the economic policy ideas of Hjalmar Schacht , who was sympathetic to the Nazis, and took a stance against National Socialism and the radical right. In an essay, Erhard opposed the economic policy of the right-wing conservative forces and called on the government to stop abuse by cartels and monopolies , especially in the capital goods industry . He called for the production of consumer goods to be promoted and, in contrast to the protectionism that prevailed at the time, advocated a competitive economy and free market pricing.

In the Nazi era

From 1933, however, Erhard made statements in which he spoke positively about the National Socialist compulsory cartelization , since it prevented the damage of the "unrelated price war", which Erhard's biographer Hentschel sees as a not unusual adaptation to the spirit and language of the time. Vershofen also saw cartels and price agreements as a positive measure that was advantageous for both suppliers and buyers.

In 1933 Erhard joined the management of the institute headed by Vershofen , became a co-founder and editor of the institute's own magazine Der Markt der Ready -Made Goods and editor-in-chief of the economic-political leaves of the German finished goods industry , the second organ of the institute. Erhard is one of the reasons why the Nuremberg Institute has been focusing on market research for industrial customers since 1934.

In 1935, Erhard organized the first marketing seminar in Germany, known at the time as a " marketing course", at the Institute for Economic Observation (IfW) at the Nuremberg School of Management, which later became the Nuremberg Academy for Marketing (NAA) and the Society for Consumer Research (GfK e. V.) emerged.

From 1933 Erhard worked as a lecturer at the Nuremberg Commercial College. In 1939 the attempt to make Erhard an honorary professor at the commercial college failed. The Bavarian Ministry of Culture rejected this after a report by Karl Rößle , since he had submitted too few specialist publications, and recommended that Erhard habilitation . His attempt to habilitate at the university, which had had the right to habilitation since 1931, was unsuccessful with the topic "Overcoming the economic crisis through economic policy influence". Erhard later said that the National Socialists had prevented him from completing his habilitation.

During the war years, Erhard worked as an economic policy advisor for the integration of the annexed areas of Austria , Poland and Lorraine , on which he advised Gauleiter Josef Bürckel . When Vershofen wanted to withdraw from the institute's management in 1942, he favored Erich Schäfer as his successor, against whom Erhard, who had seen himself as a potential successor but, unlike Schäfer, was not a member of the NSDAP , vigorously opposed. As a result, he was urged to leave the business school by means of a dismissal lawsuit.

Thereafter, in the fall of 1942, Erhard founded the Institute for Industrial Research , then a one-man institute, with financial support from the Reichsgruppe Industrie . There, Erhard dealt with economic post-war planning and wrote an expertise on aspects to be considered when "exploiting anti-popular assets". In the memorandum "War Financing and Debt Consolidation" commissioned by the Reichsgruppe Industrie , he considered the reconstruction of the economy after the war and recommended, among other things, a currency cut . For this memorandum, Erhard proceeded from the premise that Germany would lose the war, which at the time could be considered high treason . He handed over the final version to SS-Gruppenfuhrer Otto Ohlendorf , who had been in charge of planning for the economy after the war in the Reich Ministry of Economics since the end of 1943 . It is disputed whether a copy of the document that he had sent to Carl Friedrich Goerdeler in July 1944 ended up in his hands. In 1944, for security reasons, Erhard relocated the Institute for Industrial Research to the site of the New Cotton Spinning Mill in Bayreuth , where he lived to see the end of the war.

According to historian Werner Abelshauser , Erhard prepared expert opinions for government agencies of the Nazi state , including on the question of how best to exploit occupied Poland. Erhard opposed discriminating against Polish workers so as not to weaken their willingness to perform. In doing so, Erhard opposed strong forces in the Nazi system that wanted to reduce Poland's population to a kind of slave status.

The journalist Ulrike Herrmann was critical of Erhard's work during this time: He was by no means just setting himself up as an "apolitical professor", but was committed and willingly served the Nazi regime. The economists Thomas Mayer , Otmar Issing and the historian Daniel Koerfer disagreed with this assessment . According to Koerfer, Erhard was "not a resistance fighter", rather "blue-eyed" and "politically naive".

Political activity from 1945

First economic policy offices (1945–1949)

After the war, the non-party economist quickly rose to high political office. Ludwig Erhard was an economics officer in his hometown of Fürth for a few months before he was appointed Minister of State for Trade and Industry by the American military government in the Bavarian state government led by Prime Minister Wilhelm Hoegner (SPD) in October 1945. After the elections in December 1946, he was replaced by Rudolf Zorn (SPD) in the new government of Prime Minister Hans Ehard (CSU) .

In 1947, Erhard headed the expert commission for money and credit in the management of the finances of the British-American bizone and was entrusted with the preparation of the currency reform . In 1947 he became honorary professor at the University of Munich and in 1950 also at the University of Bonn .

On March 2, 1948, at the suggestion of the Liberals, Erhard was elected Director of the Economic Administration of the United Economic Area and was thus responsible for economic policy in the western zones of occupation. Erhard was only informed by the Western Allies five days before the planned date of the forthcoming currency reform on June 20, 1948. A day before the reform, he announced on the radio that forced management and fixed prices had been lifted for a first area of industrial finished products. The gradual abolition of price controls by Erhard was conceived by his colleague Leonhard Miksch.

After parts of the CDU had committed themselves to an economic and socio-political direction in the Ahlen program at the beginning of 1947 , which was described as " Christian socialism ", Adenauer invited Erhard to the party conference of the CDU in the British zone on August 28, 1948 in Recklinghausen to make his party known there for the first time with its positions on the social market economy . The Düsseldorf guidelines as a program for the 1949 federal election contained elements from both concepts. Two decades later, Ludwig Erhard summed it up: "In that first election campaign, the social market economy and the CDU became one identity."

Erhard's economic policy was initially highly controversial, since the cost of living rose by 14 percent in the first four months after price liberalization, but wages that had been frozen since 1939 were not released. The price increases reached up to 200%, for individual foods such as eggs up to 2000%. According to calculations by the Economic Research Institute of the Trade Unions in Cologne, Erhard's economic policy reduced the wage share from 83 percent in June 1948 to 45 percent in December of the same year. In the case of low earnings, the money was usually only enough to buy the staple foods that were still farmed to date. In the late summer of 1948, this situation led to growing social tensions with class-struggle accents. For November 12, 1948, the German trade union federation called for a general strike , the participation of which reached around 79%. On the other hand, the price liberalization ensured that many goods that had previously been hoarded or only sold on the black market were again sold regularly via retailers, which increased the range of goods.

Shortly after the strike, Konrad Adenauer called on Ludwig Erhard to use all “available means to counteract unjustified price increases” and to “accelerate the adjustment of wages and benefits that have not been paid to the price level”. It was not until 1949 that the excessive prices slowly went down again. The unemployment rate rose from 3 percent at the time of currency reform to over 12 percent in March 1950.

In 1949, as Director of the Economic Administration, Erhard tried to intervene with the US military authorities to prevent the return of the Rosenthal Porzellan AG porcelain company , which had been “ Aryanized ” by the Nazis , to the family of company founder Philipp Rosenthal . In addition to his public office, Erhard had had a consulting contract with Rosenthal AG for an annual sum of 12,000 DM since 1947. From this point on, the US secret service classified him as corruptible. The Ludwig Erhard Foundation confirms Erhard's consulting activities for Rosenthal as early as 1940/41.

Erhard was a member of the neoliberal Mont Pèlerin Society . After the war, he merged the Institute for Industrial Research into the Ifo Institute for Economic Research , which was founded in 1949 .

MP

From 1949 until his death in 1977, Erhard was a member of the German Bundestag . From 1949 to 1969 he was a directly elected member of parliament for the Ulm constituency for the CDU, and in 1972 and 1976 via the CDU state list for Baden-Württemberg . In both 1972 and 1976, he was responsible for opening the German Bundestag as senior president .

Economy Minister

After the federal elections in 1949 , Erhard was appointed Minister of Economics in the Federal Government led by Chancellor Adenauer on September 20, 1949 .

Ludwig Erhard is regarded as a representative of ordoliberalism , which was essentially shaped by Walter Eucken in his 1939 work Fundamentals of National Economics. In ordoliberalism, the state has the task of creating a regulatory framework for free competition in which the freedom of all economic subjects (also from each other) is protected. From this school, Wilhelm Röpke and Leonhard Miksch in particular had a direct influence on economic policy in the first decade of the Federal Republic, but the influence of Eucken and Miksch on Erhard is considered by some to be rather small. As a second economic policy concept, the social market economy designed by Alfred Müller-Armack had a fundamental influence on the politics of the young federal government, although Erhard's view of this concept differed significantly from that of Müller-Armack.

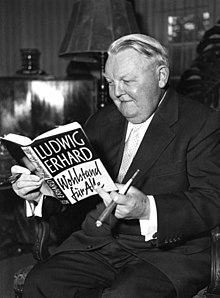

The great election victories of the CDU in the federal elections of 1953 and 1957 were largely due to the successful strategy of linking the (actually international) economic upswing in the consciousness of the citizens with the Union's model of the social market economy. In his popular book Prosperity for All (1957), Erhard presented his ideas in a way that was easy to understand. He advocated the liberalization of foreign trade and the convertibility of international currencies, which earned him the reputation of a dogmatist within his own ranks.

Far-reaching decisions from his time as Economics Minister were, for example, the reorganization of antitrust law with the law against restraints of competition from 1957 or the Bundesbank law from the same year, with which a German central bank independent of political directives was established. Furthermore, Erhard began privatizing companies that were previously state-owned ( Preussag AG 1959, Volkswagen AG 1960, VEBA 1965), whereby the shares could each time be acquired as people's shares . These actions were intended to advance the wealth accumulation of private individuals.

From the beginning of his work as a minister, Erhard was exposed to harsh criticism from the chancellor. Adenauer's main allegations were frequent absenteeism, lack of control by the ministry, and thoughtless speeches. His supporters were jokingly called “ Brigade Erhard ” – after a naval unit from the Kapp Putsch of 1920. One of the highlights of the differences was the pension reform of 1957 , which Adenauer pushed through with his policy competence as chancellor. Erhard rejected the apportionment procedure that has existed since then ( so-called generation contract) as not sustainable. However, Adenauer ignored these concerns with the well-known saying “People will have children anyway”. Erhard was also skeptical about the German co-founding of the European Economic Community by Adenauer in the same year. He saw the economic integration of Europe mainly in a free trade area .

After the 1957 federal election , Adenauer appointed Ludwig Erhard as vice chancellor in his third cabinet . On February 24, 1959, Adenauer proposed Erhard's candidacy for the office of Federal President , which he finally rejected on March 3. After the federal elections in 1961 , Erhard again became vice chancellor and economics minister. When he could have won the chancellorship during the Spiegel affair in 1962, he disappointed his supporters with his hesitation.

Chancellor

Adenauer resigned on October 15, 1963, fulfilling an agreement with the coalition partner FDP . Although he is said to have rejected Erhard as his successor, he was elected Chancellor a day later. Erhard's chancellorship was often seen as an interim solution to ensure a Union victory in the next federal election.

With his Foreign Minister Gerhard Schröder , Erhard was one of the Atlanticists who prioritized relations with the United States over those with France. From the ranks of the CDU, he was therefore accused, among other things, of being responsible for a cooling off in Franco-German relations .

Erhard initiated - without a formal cabinet decision - the opening of negotiations to establish diplomatic relations between the Federal Republic of Germany and Israel , which were concluded in May 1965; it was the only policy decision of his tenure. After the exchange of ambassadors, numerous Middle East countries broke off relations with the Federal Republic.

In the Bundestag elections on September 19, 1965, Erhard achieved what was then the second-biggest election victory in the history of the Union, but even when the government was being formed he was no longer able to assert his views in the CDU/CSU. In order to assert himself and to slow down his competitor, the CDU/CSU parliamentary group leader Rainer Barzel , Erhard had himself elected on March 23, 1966 as the successor to Adenauer as the leader of the CDU.

Erhard's standing as an economist was shattered when the second economic recession hit in 1966 (after a first that followed immediately after the currency reform of 1948), accompanied by rising unemployment figures. The description of the crisis as a "deliberate recession" by the then Federal Minister of Economics Kurt Schmücker , Erhard's successor in this office, subsequently developed into a combat term that was used against the Union.

In July 1966, Erhard had to pass his first state election as party chairman in North Rhine-Westphalia . In the most populous federal state, the coal industry had been struggling with the coal crisis for years, which was accompanied by a crisis in the steel industry . During the election campaign, Erhard's public appearances in the Ruhr area were sometimes accompanied by unusual, strong protests to which he reacted with little sovereignty. In the election on July 10, 1966 , the CDU received 42.8 percent of the votes, 3.6 percentage points less than in the 1962 election, but was able to re-form the state government together with the FDP with a very narrow majority ( Cabinet Meyers III ). Shortly after Erhard's resignation as chancellor, there was a change of government in North Rhine-Westphalia : the SPD and FDP formed the Kühn I cabinet . In the state elections in Hesse on November 6, 1966 , the opposition CDU there lost 2.4 percentage points.

The negotiations on the foreign exchange equalization agreement (offset agreement), which was intended to compensate for the costs of stationing US troops on German soil, were a serious test for German-American relations. While in the first two agreements concluded by the Adenauer government the fulfillment of the demands were subject to the German budgetary reservation, in May 1964 Erhard undertook to make unconditional payment in the follow -up agreement, which Uwe Wesel saw as a “frivolous promise”. When Germany was unable to complete the commitments it had made in 1966, Erhard tried in vain to obtain concessions from US President Lyndon B. Johnson in Washington in September 1966; the trip became a "complete failure". This financial strain, along with others, jeopardized the preparation of the 1967 budget and contributed significantly to the rupture of the governing coalition. The grand coalition that followed was finally able to solve the offset problem in April 1967 with an “astonishingly smooth regulation”.

In the course of the second half of 1966, a dramatic loss of authority on the part of the chancellor became clear, which was also noticed by the allies, and leading Union politicians withdrew their support. After the ministers of the FDP resigned from the Federal Cabinet because they refused to compensate for the existing budget deficit through tax increases, as Erhard intended, Erhard formed a minority government of CDU and CSU on October 27, 1966, but declared his willingness just six days later to resign. The CDU/CSU parliamentary group then elected Kurt Georg Kiesinger , Prime Minister of Baden-Württemberg, as their candidate for chancellor, who brought about a grand coalition with the SPD. Erhard resigned on November 30, 1966 and Kiesinger was elected his successor the following day. On December 13, 1966, Kiesinger said in his government statement that the formation of this federal government was preceded by "a long, smoldering crisis, the causes of which can be traced back years."

In 1964, Ludwig Erhard had the Chancellor's Bungalow built in the park of Palais Schaumburg as the Chancellor 's residential and reception building.

party membership

At the beginning of his political career, Erhard leaned towards the FDP, but its chairman Theodor Heuss advised him to join a larger party. In an interview, the journalist Günter Gaus Erhard asked why he decided to join the CDU:

"Gaus: 'You only declared your support for the CDU in mid-1949, before the elections to the first Bundestag. That was your first party entry ever. Why did you choose the CDU?'

Erhard: 'Because it was necessary to put into practice a liberal, liberal policy as I had in mind. That didn't mean that I should strengthen a liberal party again, but that I won the big people's party, the CDU, for me, for my ideas and then committed myself to it.'"

From March 1966 to May 1967 he was federal chairman and from 1967 honorary chairman of the CDU. The fact that no other party offices can be proven in his political career is unusual for a long-standing top politician.

Despite the fact that he was politically active exclusively for the CDU from 1949, the question of Erhard's formal party membership has not been finally clarified.

In 2002, the deputy head of the Konrad-Adenauer-Foundation's archive for Christian-Democratic Politics , Hans-Otto Kleinmann , explained that the question of party membership for Erhard actually only arose when he was elected CDU chairman, since this post was only can be exercised by a party member. Erhard therefore joined the CDU in 1966, but the date of accession was three years earlier in the CDU books and was thus formally set at 1963. In fact, Erhard would have been non-partisan when he took office as Federal Chancellor in 1963. In contrast, in 2007 Horst Friedrich Wunsch, managing director of Bonn's Ludwig Erhard Foundation, stated that Erhard had never been a party member of the CDU, which Kleinmann's colleague Günther Buchstab confirmed. Although a membership card from 1968 backdated to 1949 can be found at the CDU district association in Ulm, Erhard did not sign it; a declaration of membership was not available and paid membership fees could not be proven. The archives of the Ludwig Erhard Foundation contain two inquiries from November 27, 1956 and February 14, 1966 from the incumbent CDU chairman Adenauer to Erhard regarding party membership. In response to the second request, Erhard, referring to his great achievements for the CDU, conceded a "supposed blemish" that he "didn't pay any attention to having the party book..."

On February 13, 1966, according to the diary of his son Paul, Konrad Adenauer told the family that Fritz Burgbacher had told him how difficult it had been to accommodate Erhard as a member of the CDU about one or two years ago in a small town near Heidelberg, which made him "cost a lot of money".

reception

Initially, Erhard's economic policy was met with skepticism and sometimes severe criticism. Marion Countess Dönhoff commented in the summer of 1948: "If Germany wasn't already ruined, this man with his completely absurd plan to abolish all farm management in Germany would definitely manage it. God protect us from the fact that he will one day become Minister for Economic Affairs. That would be the third catastrophe after Hitler and the dismemberment of Germany.”

Erhard later became one of the most popular politicians and was considered by many to be the creator of the "German economic miracle". On the other hand, the historian Werner Abelshauser believes that the so-called economic miracle “didn't fall out of the blue”, and that Germany was already on the way to a post-industrial society in the first half of the 20th century . It was Erhard's merit that he used Germany's highly developed economy in the 1950s and made it successful worldwide. According to Albrecht Ritschl , Erhard's great achievement "is less about having designed reforms - but about having prevented wrong decisions."

However, his time as Federal Chancellor is often seen as "unlucky". The model of a “formed society” that he presented to the party in March 1965 at the 13th party conference of the CDU met with little approval. His political failure as Chancellor was attributed not least to the fact that he lacked assertiveness as a "lateral entrant" into politics and that his collegial style was interpreted as a weakness in leadership. The discomfort with his administration is expressed in a report from his first year in office in the news magazine Der Spiegel :

“The Federal Chancellor is one of those only apparently thick-skinned and thick-skinned pyknic types who need recognition […] Even the cool breeze that has been blowing in Erhard’s face from time to time since he entered the command bridge in the Palais Schaumburg is enough to be to disturb mental balance.”

Erhard's adviser Johannes Gross also pointed out his shyness and hesitancy in small circles; it contrasted with the public display of optimism in his rousing speeches.

Erhard evidently found intellectuals to engage in oppositional political activities to be an impertinence, which he rejected in a problematic manner: by dismissing the literary work of the SPD election campaigner Günter Grass as "unappetizing signs of degeneration", in a similar way Rolf Hochhuth , who described the "economic miracle" had critically examined, as "Pinscher".

Like Adenauer, many others believed he was unfit to be chancellor. In recent historical research, it is particularly noted that Adenauer humanely rejected his Minister of Economics:

“Adenauer's aversion to Erhard was abysmal and absolute. The aged chancellor was not above attacking Erhard publicly or behind his back in party circles. [...] He hated Erhard's long monologues on economic issues. He disliked Erhard's casual attire and disapproved of the cigar smoke that Erhard liked to douse himself with, as well as the cigar ash that accumulated on his lapel. He regarded Erhard's alcohol consumption as a moral affront. And finally, he found Erhard's penchant for self-pity unbearable."

People from other political camps also occasionally refer to Erhard. such as B. Sahra Wagenknecht of the left , who recalled his vision of "prosperity for all" and his fight against cartels; he just didn't finish it consistently.

Late Years and Personal Life

After his time as Chancellor, Ludwig Erhard remained a member of the Bundestag for eleven years. In 1967 he founded the Ludwig-Erhard-Foundation , which was to continue to cultivate his ideas about economics and economic order in a scientific and journalistic manner. Erhard, who was a member of the Evangelical Church, was the first chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Hermann Kunst Foundation for the Promotion of New Testament Textual Research (1964-1977), which promotes the work of the Institute for New Testament Textual Research in Münster.

In retrospect, shortly before his death, he commented on his economic policy work, in particular on preventing the inflation of the public sector and the rapidly increasing national debt: "As a federal minister, I had to use 80 percent of my strength to fight against economic nonsense, unfortunately not without success ."

Ludwig Erhard had been married to the economist Luise Schuster (1893–1975), nee Lotter, from Langenzenn from December 1923. She was widowed and had a daughter from her first marriage. From her marriage to Ludwig Erhard, the daughter Elisabeth Friederike Marie (1925-1996) emerged, who married the sports official Hans-Jörg Klotz in 1952 . Erhard lived with his family in Gmund am Tegernsee (Bavaria) from 1953 until his death . Cigar smoking was Erhard 's trademark from 1930 onwards.

Erhard died of heart failure on May 5, 1977 in Bonn. On May 11, 1977, on the occasion of his death, a state ceremony took place in the plenary hall of the German Bundestag. He was buried in the mountain cemetery in Gmund am Tegernsee. There, in the town center, a bust by the sculptor Otto Wesendonck commemorates the famous citizen.

awards

- 1943: War Merit Cross 2nd Class

- 1953: Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- 1955: Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic

- 1959: Bavarian Order of Merit

- 1960: Grand Cross of the Order of El Sol del Perú (Peru)

- 1961: Grand Cross of the Order of Saint James of the Sword (Portugal)

- 1961: Grand Cross of the Order of Isabel la Católica (Spain)

- 1967: Alexander Rüstow Plaque

- 1977: Honorary citizenship of the city of Ulm

culture of remembrance

The Ludwig Erhard Prize is awarded annually on the basis of the EFQM model to companies that demonstrate special achievements in quality management .

With the Fürth Ludwig-Erhard Prize , the Ludwig-Erhard-Initiativkreis Fürth honors economics dissertations "in which the factors of innovation, practical relevance, feasibility, economic benefit and the effects on the people in our society are increasingly taken into account".

The Ludwig Erhard Foundation awards the Ludwig Erhard Medal for services to the social market economy and the Ludwig Erhard Prize for business journalism .

Erhard's birthplace in Fürth is part of the Ludwig Erhard Center commemorating his life and work.

On the occasion of his 110th birthday in 2007, a bust made by the Aachen sculptor Wolf Ritz was placed in the entrance area of the Federal Ministry of Economics in Berlin.

In many German cities, streets, paths, squares, bridges or schools are named after Ludwig Erhard.

factories

- Nature and content of the unit of value. Dissertation. 1925

- War financing and debt consolidation. memorandum. 1944. Propylaea, 1977, ISBN 3-550-07356-9 .

- Germany's return to the world market. 1953

- Prosperity for All 1957. 8th edition: 1964.

- German economic policy. 1962

- Published by the Press and Information Office of the Federal Government: The concept of the “ formed society ” according to Ludwig Erhard . Bonn (1966) digitized

- limits of democracy? Dusseldorf 1973.

literature

- Erwin von Beckerath , Fritz W. Meyer , Alfred Müller-Armack (eds.): Economic issues in the free world. [On the occasion of the 60th birthday of Federal Minister of Economics Ludwig Erhard]. Knapp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1957.

- Jan Berwid-Buquoy: The father of the German economic miracle - Ludwig Erhard. Quotations, analyses, comments. From the Czech, BI-HI-Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-924933-06-5 .

- Christian Gerlach : Ludwig Erhard and the "economy of the new German East region". A report from 1941 and Erhard's advisory work on the German annexation policy 1938-43. In: Matthias Hamann, Hans Asbeck (eds.): Contributions to the history of National Socialism . Issue 13: Reason halved and total medicine. Black cracks publishing house, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-924737-30-4 , pp. 241-276.

- Manfred Hahn: References to literature about the "Formed Society" . In: The argument , Berlin booklets for problems of society. 10 October 1968. Issue 4/5, pp. 300-308.

- Volker Hentschel : Ludwig Erhard. A politician's life. Olzog Verlag, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-7892-9337-7 . Review by Fritz Ullrich Fack , review by Frank Decker , review by Yorck Dietrich

- Volker Hentschel: Ludwig Erhard, the "social market economy" and the economic miracle. Historical lesson or myth? Bouvier Verlag, Bonn 1998, ISBN 3-416-02761-2 .

-

Ulrike Herrmann : Germany, an economic fairy tale. Why it's no wonder we've gotten rich. Westend Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2019, ISBN 978-3-86489-263-9 , pp. 53–80. ( Review by Christian Rickens in the Handelsblatt of December 5, 2019.)

- abridged excerpt from it: A profiteer of the Nazis. In: taz September 19, 2019.

- Peter Hoeres : Foreign policy and the public sphere. Mass Media, Public Opinion Research, and Arcane Politics in German-American Relations from Erhard to Brandt . (= Studies in International History. Volume 32). de Gruyter Oldenbourg, Munich 2013.

- Karl Hohmann: Ludwig Erhard (1897-1977). A biography. Ed. Ludwig Erhard Foundation, ST Verlag, Düsseldorf 1997 ( PDF file, approx. 3 MB ). (28-page brochure by a former ministerial director and head of the chancellor's office under the chancellor, Erhard)

- Daniel Koerfer : Battle for the chancellorship - Erhard and Adenauer. DVA, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-421-06372-9 .

- Volkhard Laitenberger: Ludwig Erhard - The national economist as a politician. Muster-Schmidt Verlag Goettingen, Zurich 1986 ISBN 3-7881-0126-1 .

- Bernhard Löffler : Ludwig Erhard. In: Katharina Weigand (ed.): Great figures of Bavarian history. Herbert Utz Verlag, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-8316-0949-9 .

- Andreas Metz: The unequal founding fathers: Adenauer and Erhard's long way to the top of the Federal Republic. UVK, Constance 1998, ISBN 3-87940-617-0 .

- Alfred C. Mierzejewski: Ludwig Erhard - the pioneer of the social market economy. From English. Settlers, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-88680-823-8 . (English edition Chapel Hill, the University of North-Carolina Press, 2004.) Review excerpts at PERLENTUBE.DE, review by Gabriele Metzler , review by Philip Plickert , review by Werner Bührer , review by Hubert Leber

- Reinhard Neebe: Setting the course for globalization: German world market policy, Europe and America in the Ludwig Erhard era. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne/Weimar/Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-412-10403-5 (Habilitation University of Bielefeld 2003).

- Karl Heinz Roth : The end of a myth. Ludwig Erhard and the transition of the German economy from annexation to post-war planning (1939 to 1945). Volume I. 1939 to 1943. In: 1999. Journal for social history of the 20th and 21st centuries. 10, 1995, No. 4, ISSN 0930-9977 , pp. 53-93.

- Karl Heinz Roth: The end of a myth. Ludwig Erhard and the transition of the German economy from annexation to post-war planning (1939 to 1945). Volume II. 1943 to 1945. In: 1999. Journal for social history of the 20th and 21st centuries. 13, 1998, No. 1, ISSN 0930-9977 , pp. 92-124.

web links

- Ludwig Erhard at the Internet Movie Database

- Literature by and about Ludwig Erhard in the German National Library catalogue

- Works by and about Ludwig Erhard in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Ludwig Erhard in the 20th Century Press Kit of the ZBW – Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Dorlis Blume, Irmgard Zündorf: Ludwig Erhard. Tabular curriculum vitae in LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Ludwig Erhard in the Find a Grave database

- Entry Munzig archive

- Ludwig Erhard Foundation : About the person

- Daniel Koerfer: Learning from Erhard . The Time , May 21, 2005.

- The flight forward Der Spiegel 37/1953

- Alexander Mayer : Ludwig Erhard and Fürth's fathers of the economic miracle in the Nazi era . Online platform Fürther Freiheit from March 8, 2016.

- Interview with former German chancellor Erhard on aspects of European integration from November 27, 1968 in the online archive of the Austrian media library

itemizations

- ↑ Werner Abelshauser : There are always miracles. The myth of the economic miracle , Federal Agency for Civic Education , June 29, 2018; Accessed February 4, 2022

- ^ a b c Hentschel: Ludwig Erhard. p. 12.

- ↑ Dorlis Blume, Irmgard Zündorf: Ludwig Erhard. Tabular curriculum vitae in LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- ↑ a b c d e f g Meinhard Knoche: Ludwig Erhard, Adolf Weber and the Difficult Birth of the Ifo Institute . In: Ifo express service . Vol. 71, No. 13, 12 July 2018, pp. 14-60. ( ifo.de ).

- ↑ "Economic recovery from the consumer side". In: The German Economist , October 7, 1932, pp. 1232–1325.

- ↑ Alfred C. Mierzejewski: Ludwig Erhard , p. 33.

- ↑ Hentschel: Ludwig Erhard. p. 24.

- ↑ Thies Clausen: Ludwig Erhard - Pioneers of our prosperity yesterday and today , p. 31 f.

- ↑ Alfred C. Mierzejewski: Ludwig Erhard. p. 34; Metz: Founding Fathers, p. 33.

- ↑ Hentschel: Ludwig Erhard. pp. 17-18.

- ↑ The manuscript has been preserved by his estate.

- ↑ Günter Gaus in conversation with Ludwig Erhard (1963). Retrieved December 18, 2019 .

- ↑ Biographer Hentschel, himself an economic historian, says that according to the attempted habilitation, Erhard was not suitable as a scientific national economist, since he lacked the formal rigor and the ability to formulate clear and conclusive thoughts and to combine them argumentatively with reference to the sources used. Erhard had interpreted the causes of the global economic crisis in a logically inconclusive manner, the solution to the acute problems had been missed. He demanded that the state should intervene in production and steer the economy better, since individual interests could not be trusted to do this. However, Erhard does not explain how the state should do this. "The whole thing could have been dealt with in five pages with a tight line of thought in concise diction." But that was not Erhard's thing, who wrote 141 pages and let his thoughts run free. (Hentschel: Ludwig Erhard. p. 22).

- ↑ a b Maja Brankovic: "Erhard and the Nazi era" in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Sunday newspaper, November 15, 2020, p. 20.

- ↑ Yorck Dietrich: The Erhard biography by Volker Hentschel. p. 285.

- ↑ Michael Brackmann: Erhard's dubious legacy . Handelsblatt, November 20, 2020, p. 55.

- ↑ Cf. Michael Brackmann in Handelsblatt : The day X. June 25, 2006.

- ↑ Michael Brackmann: Erhard's double coup. General-Anzeiger Bonn, June 18, 2018, p. 10 f.

- ↑ Ralf Ptak : From ordoliberalism to the social market economy. VS-Verlag 2003, ISBN 3-8100-4111-4 , pp. 145–149.

- ↑ The Flight Forward. In: Der Spiegel 37/1953.

- ↑ Bernd Mayer : Twelve people - twelve fates in April 1945 in: Heimatkurier 2/2005 (supplement to the North Bavarian Kurier ), p. 4.

- ↑ a b c There was no economic miracle. In: The Mirror. September 23, 2020, retrieved November 2, 2020 .

- ↑ Overdue monument fall: A profiteer of the Nazis. In: taz , September 23, 2019.

-

↑ Thomas Mayer: Attack on liberalism - Ludwig Erhard was not a Nazi . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , October 6, 2019.

Otmar Issing, Daniel Koerfer: Target Ludwig Erhard , November 1, 2019.

In the taz, Ulrike Herrmann responded: Controversy about Ludwig Erhard: begging letters to an SS authority . In: taz, November 4, 2019. - ↑ House of History: Ludwig Erhard.

- ↑ Hans Tietmeyer: Social market economy in Germany - developments and experiences -. (PDF; 322 kB) (No longer available online.) Freiburg Discussion Papers on Ordinance Economics 10/4. Walter Eucken Institute / Institute for General Economic Research, Department for Economic Policy at the Albert-Ludwigs University in Freiburg i. Br. , September 13, 2010, archived from the original on March 9, 2012 ; retrieved December 1, 2016 .

- ↑ Volkhard Laitenberger: Ludwig Erhard. 1986, p. 77.

- ↑ Karl Hohmann: Ludwig Erhard (1896-1977) - A biography. p. 11.

- ↑ Markus Lingen: History of the CDU: The Düsseldorf guidelines , Konrad Adenauer Foundation.

- ↑ Völker Hentschel: Ludwig Erhard. A politician's life. Ullstein, Berlin 1998, p. 87.

- ↑ a b Rosa-Luxemburg-Foundation : Jörg Roesler: The reconstruction lie of the Federal Republic - Or: How the neoliberals produce their arguments (PDF; 971 kB) ISBN 978-3-320-02137-5 .

- ↑ Deutschlandfunk Kultur: Potato battles and a general strike - how the social market economy came about. Retrieved November 25, 2020 .

- ↑ a b c Daniel Koerfer: Learning from Erhard. In: Die Zeit , May 21, 2005.

- ↑ The Flight Forward. In: Der Spiegel 37/1953.

- ↑ a b Jürgen Lillteicher : The restitution of Jewish property in West Germany after the Second World War. A study on the experience of persecution, the rule of law and politics of the past 1945-1971. Dissertation University of Freiburg 2002, pp. 114 ff., especially pp. 125, 130; Text online (PDF; 3.3 MB)

- ↑ Constantin Goschler , Jürgen Lillteicher (eds.) (2002): "Aryanization" and restitution. The Restitution of Jewish Property in Germany and Austria after 1945 and 1989. pp. 141–142.

- ↑ History in the first: Our economic miracle. The true story. Documentary film by Christoph Weber, broadcast on ARD on July 15, 2013.

- ↑ Andreas Schirmer: The true story of the economic miracle? Ludwig Erhard Foundation, April 24, 2015, retrieved August 24, 2016 .

- ↑ Horst Friedrich wishes: The intellectual foundations of Ludwig Erhard's social market economy: claims and findings. Ludwig Erhard Foundation 2015.

- ↑ Andreas Schirmer: The invention of the social market economy. Ludwig Erhard Foundation 2017.

- ↑ Daniel Koerfer: A forgotten founding father of the fundamental optimist Ludwig Erhard and his social market economy. Friedrich-Meinecke-Institut, January 15, 2010, accessed April 12, 2021 .

- ↑ Bundesarchiv: Zeittafel 1963

- ↑ Karl Hohmann: Ludwig Erhard (1897–1977). A biography. Düsseldorf 1997, p. 24.

- ↑ Volkhard Laitenberger: Ludwig Erhard. 1986, p. 204.

- ↑ Gisela Stelly: A little consumption, not a little possession. In: The time. September 12, 1969.

- ↑ Time Mirror. In: The time. October 8, 1971.

- ↑ Ludwig Erhard's defeat on the Ruhr. In: Die Zeit 29/1966, July 15, 1966.

- ↑ Graf Bismarck colliery in Gelsenkirchen-Erle.

- ↑ Uwe Wesel : Legal history of the Federal Republic of Germany. From the occupation to the present. Munich 2019, p. 43.

- ↑ Harald Rosenbach: The price of freedom - The German-American negotiations on the foreign exchange adjustment (1961-1967). Quarterly magazines for contemporary history 46 (1998) pp. 709–746, here p. 738 ( PDF ).

- ↑ Harald Rosenbach: The price of freedom - The German-American negotiations on the foreign exchange adjustment (1961-1967). Quarterly magazines for contemporary history 46 (1998) pp. 709–746, here p. 710 ( PDF ).

- ↑ Prospects for change in West German foreign policy. (PDF; 481 kB) Central Intelligence Agency , 6 September 1966, retrieved 5 January 2020 .

- ↑ a b Sacrifice for the people. In: Der Spiegel 43/1966, October 17, 1966, retrieved on January 4, 2020.

- ↑ Volkhard Laitenberger: Ludwig Erhard. 1986, pp. 215-216.

- ↑ Bundesarchiv: Zeittafel 1966

- ↑ Kurt Georg Kiesinger, Government Statement of the Grand Coalition, December 13, 1966

- ↑ About the person: Günter Gaus in conversation . rbb-online, retrieved on April 19, 2017.

- ↑ Löffler, Bernhard (2002): Social market economy and administrative practice: the Federal Ministry of Economics under Ludwig Erhard, p. 457ff.

- ↑ Gerhard Haase: Ludwig Erhard apparently became Chancellor without a party. (No longer available online.) In: Welt Online. May 4, 2002, archived from the original on October 30, 2013 ; retrieved October 9, 2013 .

- ↑ Hans Ulrich Jörges, Walter Wüllenweber: Former CDU Chancellor: Ludwig Erhard was never a CDU member. (No longer available online.) In: Stern. April 25, 2007, archived from the original on October 26, 2013 ; retrieved 7 October 2013 .

- ↑ Andreas Schirmer: Ludwig Erhard and the CDU Ludwig Erhard Foundation, July 27, 2016.

- ↑ Günter letter : "Should I fill out registration forms?" In: The political opinion No. 462, May 2008, pp. 71-75 (with other versions on this matter).

- ↑ Konrad Adenauer - the father, the power and the legacy. The Diary of Monsignor Paul Adenauer 1961–1966 , edited and edited by Hanns Jürgen Küsters . Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2017, p. 450 f.

- ↑ Bert Losse: More interventionist than many think. In: Wirtschaftswoche , July 24, 2017.

- ↑ Volkhard Laitenberger: Ludwig Erhard. 1986, pp. 193-195.

- ↑ The touch of ice is gone. In: The Mirror. 18/1964

- ↑ Ludwig Erhard - The optimist. TV documentary

- ↑ The words of the Chancellor - A current collection of quotations on the subject: The state and the intellectuals. The Time , July 30, 1965.

- ↑ Erhard - In the style of the time. Der Spiegel , July 21, 1965.

- ↑ Alfred C. Mierzejewski: Ludwig Erhard. The pioneer of the social market economy. Biography. Pantheon Verlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-570-55007-9 , p. 268f.

- ↑ Sahra Wagenknecht: Anyone who takes Erhard's claim seriously should vote for the left. (Interview with Christian Schlesiger) In: Wirtschaftswoche , June 22, 2017.

- ↑ Elisabeth Klotz - FürthWiki. Retrieved December 9, 2019 .

- ↑ Interview: Ludwig Erhard's housekeeper about his life in Gmund. Merkur.de, May 2, 2017.

- ↑ The Fürth Ludwig-Erhard Prize retrieved from ludwig-erhard-initiative.de on June 6, 2014.

- ↑ Inauguration of the Ludwig Erhard bust, p. 82 ( memento of March 4, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ "Ludwig-Erhard-Straßen" in Germany

- ^ "Ludwig-Erhard-Wege" in Germany

- ↑ "Ludwig-Erhard-Platze" in Germany

- ↑ The touch of the ice is gone . In: The Mirror . No. 18 , 1964 ( online – April 29, 1964 ).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Erhard, Ludwig |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Erhard, Ludwig Wilhelm (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German politician (CDU), Federal Chancellor |

| BIRTH DATE | February 4, 1897 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Fuerth |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 5, 1977 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Bonn |